Jason Micheli's Blog, page 6

July 20, 2025

He is Contained in Multitudes

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Apologies for the technology issues in the recording, and apologies for the livestream not working today too. Nothing is confirmation of the online attendance quite like tech gremlins getting the way!

Luke 5.17-26

My friend Rolf Jacobson is an Old Testament scholar, serving now as the Dead of the Faculty at Luther Seminary in Minnesota. I befriended Rolf almost ten years ago when we both preached at the Festival of Homiletics. Prior to our introduction, I had read Rolf’s work but I had never met him.

I had never before seen Rolf.

Therefore I was surprised to discover he preached from a moveable chair.

“My favorite hymn is “Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus,” Rolf joked to me and then smiled a broad, shit-eating grin as he watched the discomfort spread across my crimson face.

After he stopped laughing at me, he held his arm out from his wheelchair and offered me his hand.

Later I learned his story.

As Rolf puts it, “The worst part of my life was the six months between October 1981 and March 1982— my junior year in high school.”

When Rolf was sixteen years old, he developed bone cancer. Soon after doctors amputated his right leg, the cancer spread to his lungs. Four painful lung surgeries followed. The operations were accompanied by months of chemotherapy. He was bed-ridden for six months.

“Then came the truly devastating news,” Rolf says.

The cancer that had spread from the bone in his right leg to his lungs had spread from his lungs to the bone in his left leg. After a long course of daily radiation and months spent in a Ronald McDonald House, Rolf says, “All the king’s horses and all the king’s couldn’t put me back together again.” During Lent in 1982, they amputated his second leg. The worst part of his ordeal was that none of his friends visited him. They could not bear to be near his need.

“All in all, I had over twenty surgeries in high school,” Rolf says.

Twenty surgeries and exponentially more medical claims filed.

A preacher’s kid, Rolf Jacobson’s health insurance was provided by the American Lutheran Church and administered by the denomination’s Pension and Benefits Office at which his wife Amy now works as an employee. When Amy started her job, she introduced herself to the matriarch of the staff. Sharing a bit about herself to her new boss, she mentioned that she was married to a pastor-professor named Rolf.

“Rolf Jacobson? Your husband is Rolf Jacobson? He’s alive?!”

Startled, Amy nodded, “Yes.”

Immediately the old woman began to cry.

Finally she explained to Rolf’s wife, “I remember when his first medical claims came across my desk. I paid for his surgeries and his amputations. But then the bills stopped coming. I didn't know if he lived or if he died. I was too afraid to find out. But I always wondered what happened.”

And then, wiping the tears from her eyes and the snot from her nose, she looked up at Amy like she could set down a burden, “Starting with the first claim that came into the office, I prayed for that boy every day of my life for three years without ceasing. The LORD probably thinks of me as that annoying widow at the door in his parable.”

Amy thanked her.

And the woman replied, “There was one other child, a boy like Rolf. I prayed for him every day too.”

Every day.

For three years.

Every day.

For over a thousand days.

Every day a middle-aged Claims Specialist in the Twin Cities strapped a boy named Rolf Jacobson— she didn’t even know him— down onto a mat and she carried him to Jesus.

And the boy lived!

Here is my question.

It is one of the most important questions.Did her prayers work?Or rather, did her faith work?That is, did the LORD work a miracle for Rolf because that woman carried him to Jesus in prayer and Jesus saw her faith? Is Rolf in a chair instead of a coffin because of an anonymous Claims Specialist? Would Christ not have saved him apart from her intercessions?

Before you venture an answer to the question, consider an ostensibly different question.

In his final parable before his Passion, Jesus compares the incursion of the Kingdom of God to a shepherd separating his sheep from the goats. The shepherd will place the sheep at his right hand and the goats opposite.

The distinction that divides them?

“I was in prison and you visited me.”

“I was in prison and you did not visit me.”

Our stale familiarity with the parable blunts our capacity to comprehend its mystery. After all, eleven chapters prior to this final parable of judgment, the Gospel of Matthew reports that Herod has arrested and jailed John the Prophet for accusing the king of stealing his brother’s wife.

While John the Baptist languishes in prison, John’s disciples come to Jesus, saying “The prophet wants us to ask you, are you the one or should we look for another?”

And Jesus replies with his highlight reel of miracles worked. But when John’s disciples return to John, Jesus does not go with them. John the Baptist was in prison and Jesus did not visit him.

Does Jesus not practice what he preaches? Does Jesus judge according to a command he himself does not keep? Is the Good Shepherd really a goat?

John was in prison and Jesus did not visit him.Why?

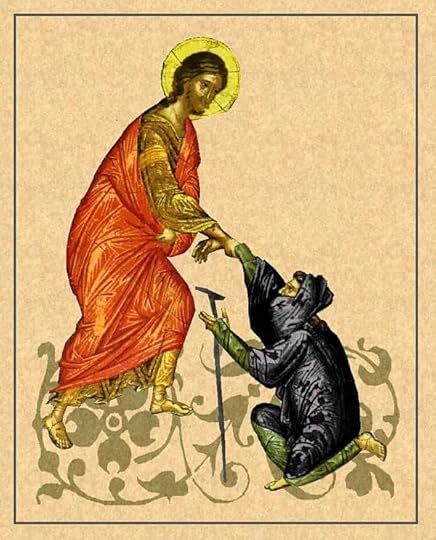

In the Gospel of Mark, the miracle for the man on the mat is the first mention of faith; meanwhile, in Luke, Jesus has just escaped the lynch mob his maiden sermon provoked in Nazareth. The angry crowd had attempted to hurl the LORD off a cliff. Now a crowd of spectacle-seekers from all over Judea has converged upon the house of Peter’s mother-in-law.

Like Lazarus whom Jesus summons from the tomb, we know nothing about the man on the mat other than his malady. Matthew, Mark, and Luke do not explain his predicament. They report only that while he does not have the use of his legs, he does have four friends.

From somewhere in Judea, they have carried him.

Somehow they have faith.

Somehow they have faith that Christ can cure the friend they carry to him.

When they arrive at the house in Capernaum, “their shoulders numb, the ache and stoop deeplocked in their backs, the stretcher handles slippery with sweat,” the crowd refuses to yield to their need. So the four of them strap their friend tight to the stretcher. They make him tiltable. And having carried him all the way to Capernaum— Judea is over two million acres big, they lift him first over the crowd and then up to the rooftop of the house.

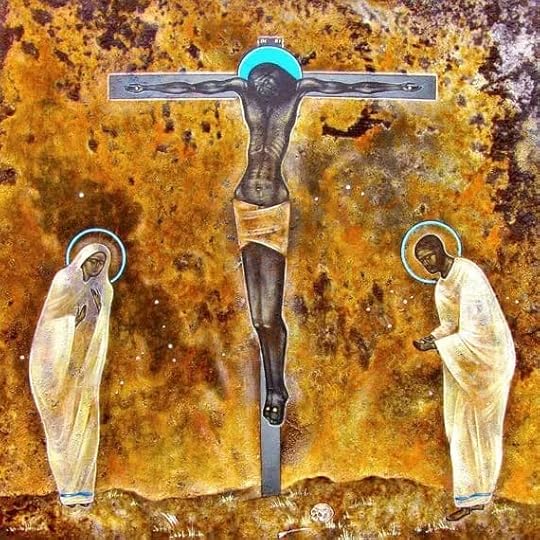

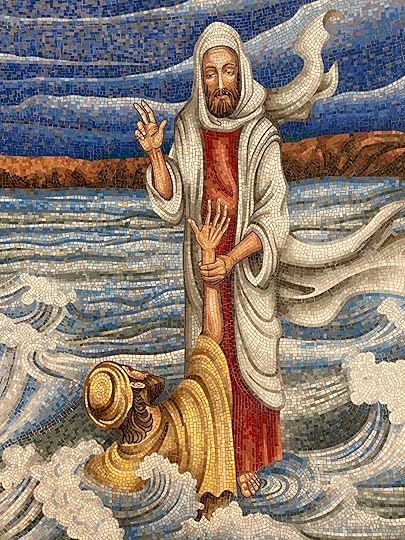

Just as at his baptism in the Jordan when the Father tore open the sky and the Holy Spirit descended upon the Son, the four stretcher bearers tear open the roof of the house and lower their friend, like a dove, down to Jesus. In Mark’s account of the miracle, the friends dig up the thatched roof; they literally “unroofed the roof.” Luke reports instead that they did not dig up the roof but removed the tiles from its crossbeams. In either case— whichever way— they determine to crash into Christ’s presence with their friend who needs Jesus.

Notice, Luke introduces their act home invasion with a little word that is auspicious in the scriptures, “Idou!”“Behold!”As in…

“Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world!” John the Baptist announces, pointing to Jesus.

“If any one is in Christ,” Paul writes to the Corinthians, "new creation! The old has passed away, behold, the new has come.”

“And Abraham lifted up his downcast eyes,” the Book of Genesis narrates, “Abraham looked, and behold! Behind him was a ram, caught in a thicket by his horns.”

As Fleming Rutledge writes:

“And behold,” Luke writes, “some men were bringing on a bed a man who was paralyzed.”Behold.Something besides the roof is being opened up before you and me.“When the word translated “behold” appears in the Old and New Testaments, it does not simply mean “see!” or “look!,” contra recent translations. It denotes a powerful revelation— an unveiling— of the LORD Jesus Christ.”

In his book God Meets Us in Our Suffering, Rolf Jacobson recalls long regimen of radiation in the interim before he lost his last leg.

He writes:

“During radiation treatments, I stayed at the Ronald McDonald House. My dad or mom was always with me. One day, my dad said, “Jerry Larson is coming down today and taking us to dinner.” I didn’t feel up to it and told him to go without me. But Jerry was a force of nature.

He was a traveling paper salesman with a radiant, oversized personality—bald on top, always flushed red, and constantly grinning. He bargained with his barber for half-price haircuts and radiated joy wherever he went. When Jerry insisted on something, resistance was futile.

So I found myself in the back seat of Jerry’s sedan, carried sideways in the car because the tumor in my leg prevented me from bending my knee. My leg ached dully. My mood ached worse. I silently vowed to endure dinner and complain later. Jerry drove us north to the Fisherman’s Inn, a Minnesota supper club. I don’t remember the menu, but I’ll never forget the scene. Our waitress brought drinks and asked if we had any questions.

Jerry pounced.

“How are your ribs?” he asked. “No, really—how are your ribs? If your favorite uncle came to town, the one who did everything for you when you were little, would you serve him these ribs?”

The waitress, caught in Jerry’s infectious spirit, replied, “I would insist he have our ribs!”

“We’re all having ribs!” Jerry proclaimed.

And we did. They were just what an emaciated cancer-stricken teenager needed. The laughter, the food, the joy—it all turned something over inside me. I’d been stewing in pain and bitterness. That night, I tasted grace.

Before dinner, I was trapped in the grind of cancer and isolation. But Jerry’s faithfulness made it the best moment in the worst part of my life. I’m nearly eternally grateful to Jerry—which is to say, I’m grateful to God—for it. Jerry was Christ to me.”

Jerry was Jesus to Rolf.

He did not mean that as a metaphor.

And since he did not mean that as a metaphor, the claim is put better— we hear it more clearly— the other way around, “Jesus was Jerry to Rolf.”

Jesus was Jerry to Rolf.“Behold,” God says to the prophet Jeremiah, “I am the LORD of all flesh: is there any thing too hard for me?"

If Jesus summons us to visit the prisoners, then why do the Gospels not report Jesus visiting John the Baptist in jail?

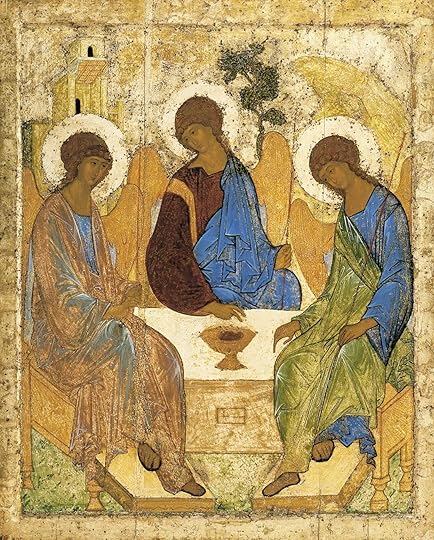

Jesus does not go visit John in prison because Jesus is already with John in prison. It’s right there in the parable, “What you do to the least of these, you do it to me.”Unlike John in jail, Jesus is not confined to the location he occupies.We hear his final parable as a sobering summons to action when really— read it again— Jesus uses the parable to reveal to us the mystery that he can be in many places at once: with the hungry and at the same time with the thirsty, with the stranger yet simultaneously with the naked, with the sick but also in prison.

He is not trapped in the room where he is present. He is not bound by space. He is contained in multitudes.

He is with John in jail even as John’s disciples alert him to the Baptizer’s arrest. He is on the heavenly throne even as he is in Mary’s womb.

While he is teaching in a crowded house in Capernaum, he is simultaneously wherever two or three or four are gathered to bear their friend on a mat to a miracle.There is not anything that is too hard for him!

The scribes and the Pharisees rage in their hearts at Jesus for doing what only God can do, pardoning the man of all his sins. In Matthew’s account, the crowd walks away from this miracle in awe, astounded that God had given such authority and power to a human being. The scribes and the Pharisees make the same mistake as the crowd. But we commit the very same error when we suppose that Jesus is confined to a single space he occupies.

He’s not.

As Robert Jenson writes:

“The Christian God is not so transparent to knowledge as to harbor no surprises.”Jesus is not trapped in the room where he resides.

Multitudes contain him.

That this is a deep mystery does not negate the fact that it is the straightforward teaching of the scriptures.

The author of the Book of Hebrews proclaims that “Faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” But the word translated into English as assurance is the word hypostasis, the Greek word for person— the same word the creed uses to describe the Son’s relation to the Father and their relation to the Spirit.

Faith is now the presence of the person for whom we hope.Two chapters later, the Book of Hebrews says that “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever.” But that affirmation about Christ comes in the context of an exhortation about faith. Thus Jesus Christ is constant across time because at all times he is present as faith; he is present in faith.

Jesus Christ the same yesterday, today, and forever means that wherever you see faith happening, that is Jesus’ life taking shape in the world.Whether he’s ascended on the throne or wrapped in swaddling clothes in the manger, Jesus is not limited to his location.

Again, this just is the teaching of the scriptures.

In the Epistle to the Romans, the apostle Paul declares, “For I am not ashamed of the gospel…For in it the righteousness of God is revealed from faith to faith.” The Book of Hebrews echoes this thesis when it refers to Jesus as “the Pioneer and Perfector of our faith.”

From faithfulness to faithfulness.

Pioneer to Perfection.

In other words:

From the Beginning to the End.

From First to Last.

Alpha and Omega.

These are three of Christ’s names.

And Faith is another one!

Faith is a name for Jesus.When Paul speaks of faith, he’s talking about Jesus. He’s pointing to Christ happening in him.

This is why Paul appeals to the Corinthians by writing:

The claim is right there in the logic chain. Faith depends upon Jesus not being dead because if Jesus is not living then he is not available to be alive in your faith. And if he is not living in your faith, then…why bother?"If the dead are not raised, not even Christ has been raised. And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is useless.”

Faith is neither an innate attribute nor an acquired skill. Faith is a synonym. Faith is a synonym for the energy and the activity of Jesus happening in and at work through you.

Paul says this explicitly in the Letter to the Galatians:

“It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. The life I now live in the body I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me.”

And then in the very next chapter Paul makes faith the subject of verbs.

Notice how Paul uses faith and Christ as interchangeable terms:“Now before faith came, we were held captive under the law, imprisoned until…faith would be revealed. So then, the law was our guardian until Christ came…But now that faith has come, we are no longer under a guardian.

Faith is just another name for Jesus.

If you don’t turn your head from it and shrink from the mystery, the claim is clear. According to Paul, faith is Jesus (who is not dead) dwelling in you.

You do not “have” faith, as though it were your possession.

Faith is at work in you, as Jesus; faith is Jesus possessing you.

Faith is Christ’s compassion— his desire and love, his mercy and gentleness, both his grace and his righteous unrest— alive in you. “If Christ is in you,” Paul proclaims, “the Spirit will be your life because of Jesus.”

Jesus did not go to visit John because Jesus was already present with John.

As faith.

The same faith that moved a Claims Specialist to pray for an anonymous boy.

Thus far, Rolf has not once picked up his wheelchair and walked home. But he did survive to become a take-no-prisoners player of Settlers of Catan. And he plays guitar in a bluegrass band called the Fleshpots of Egypt.

Recollecting his final amputation, Rolf writes:

“Despite months of effort, the Mayo team couldn’t save the leg…On March 13, 1982, they amputated it…The last thing I remember of that day was lying on a gurney, waiting to be wheeled into surgery, visiting with a fellow who was also awaiting surgery. When they came to get me, he said, “May God bless you.”

The man walking beside the bed just was the blessing of God.

No.

The man walking beside the bed with a blessing in his mouth was God.

That was Jesus.

Behold!

When the friends of the man on the mat tear open the roof of the crowded house and crash into Christ’s presence— when Jesus sees their faith, according to the scriptures Jesus is doing nothing short of looking at himself.

He is in the room.

And he is on the roof.

Jesus is not just where you can see him.He is in the faith of the friends of the man on the mat.

They have broken into the house like the Wet Bandits and crashed through the roof into Christ’s presence not simply because they wanted their friend there but because Jesus wanted him there.

Just so—

That Claims Specialist in St. Paul was not simply praying for Rolf.

She was the Providence of God for Rolf.

Faith is not how we persuade God to act.Faith is how Christ acts in and through us to be the providence of God.Notice:Before the man on the mat is forgiven, Jesus calls this sinner “Friend.”God calls him “friend” before God forgives him! And God heals this friend without a single mention of him having any faith. Matthew, Mark, and Luke say nothing about the man on the mat having faith. The ones who bear him to Jesus have faith.

Hear the good news:

Faith has nothing to do with God befriending you.

Faith has nothing to do with God forgiving you.

Faith has nothing to do with God working a miracle for you.

Your faith has nothing to do with you!

Faith is not what you offer so that God will do good for you. Faith is the LORD Jesus in you— Jesus at work in you— wanting to do God's will for the people around you who are suffering, for the people around you who are forsaken, for the people around you who are grieving, for the people around you who need Jesus.

Faith is Jesus at work on you so that you will bear another’s burden. Faith is Jesus alive upon you so that you will speak with a blessing on your mouth to a boy in need. Faith is Jesus in you so that you will carry someone to God.

The fact is:

You don’t need faith to be a friend of Jesus.

You don’t need faith to be forgiven all your sins.

You don’t need faith to be healed.

And you certainly don’t need faith to receive a miracle.

It’s sin that makes us think that God is so transactional.It’s sin that makes us think our compassion is not first God’s compassion.It’s sin that makes us think we must persuade God to act according to love.And it’s the devil who speaks in if/then conditions.On the one hand, it’s a terrible business model for the church.Yet it’s the gospel truth.You don’t need faith for God to call you friend.You don’t need faith for pardon.And you don’t need it for him to grant you a miracle.But!But you do need faith to cooperate with Jesus.You do need faith to participate in what he is up to in the world. You do need faith to cooperate with the healing God in bringing the sick to him.

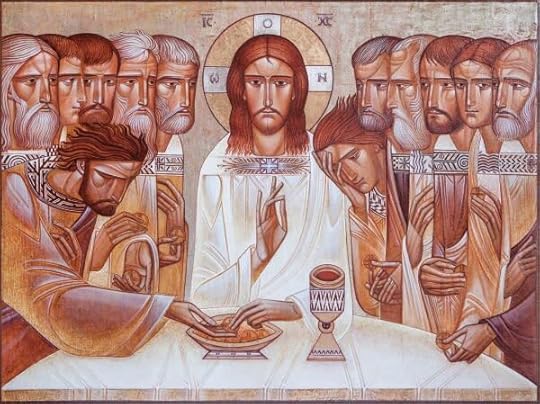

Therefore, come to the table.

For that reason, come to the table.

Come to the table— take and eat; become the providence of God.

Taste and see that he will never leave you once he indwells you.

It’s only a sip and a swallow but it’s enough.

It’s enough for you to be Jesus for someone.

Come to the table.

Jesus is not just where you can see him.

Come to the table, where like recognizes like.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 17, 2025

"The last thing you want to do is keep your head above water.”

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The lectionary epistle reading for this Sunday is Colossians 1:15-28.

Below is an old sermon on the passage. Here is audio of it.

Immediately upon opening the Bible, a question confronts the reader.

Should the first verse of the first book of the Bible read, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth,” with “God created…” as a main clause? Or should the verse instead read, “In the beginning when God created the heaven and the earth,” with “God created…” in a temporal clause. The former posits God as the sheer beginning of everything and makes time itself one of the creatures of God’s making. The latter, looking to the second verse of Genesis, suggests that the chaos over which the Lord’s Spirt broods, bringing forth light and life, was somehow antecedent to God’s creative act.

The King James and the Revised Standard Versions both render the verse in the former translation, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.”

Modern translations like the New Revised Standard Version elect the latter, “In the beginning when God created the heaven and the earth.” The Hebrew does not settle the disagreement since the Hebrew word order can make either translation intelligible. Consultation of the original language cannot answer the question: Is God the sole and sheer beginning of everything, or is there something prior, alongside God, when God creates?

The imponderables do not end with the Bible’s first verse.

According to scripture's first creation story, God creates by speech-act. Specifically, God creates by commanding, "And God said, “Let there be light;” and there was light.” Hence, the existence of all reality is the result of obedience to a command. The simplicity of the sentence structure masks the underlying mystery. Prior to the creation of any other verbal creatures, to whom does God speak when God speaks his first command? Who does God command to make light and land? Who listens and obeys him?

The questions do not stop there in the creation story.

July 16, 2025

No Formula, Only Faithfulness

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Luke 5.17-26

This Sunday I am preaching on Luke’s account of the four friends who lower their paralyzed friend down to Jesus. As with the story of the Centurion’s child, this is an instance of a third party miracle. Jesus sees not the paralytic’s faith but his friends’ faith and heals him only after first forgiving him of his sins.

A sloppy reading of scripture might suggest that Jesus pardons and heals the paralyzed sinner on account of his friends’ faith— that faith is the requisite precondition for the miracle. Such an interpretative move, however, ignores other episodes where Jesus heals not because he finds faith in a person but because he sees him or her (for example, the widow at Nain) and is moved to compassion. In fact, if you read the Gospel’s account of Christ’s miracles, then you notice how the common feature they all share is the lack of a standard pattern.

Jesus does not heal the same way twice. Miracles are not the performance of a fixed technique.In the case of the Centurion, Jesus need not even be present. Rather than a healing touch, he but needs to say a healing word. Meanwhile, he does not touch the woman with the issue of blood; she touches him. And she touches not him but the hem of his garment. Sometimes Jesus speaks a word, and the healing occurs immediately, “Be clean,” he says to the leper. Other times he engages in what appears to be either street theater or an impromptu effort—spitting on the ground, making mud, smearing it on a blind man's eyes, and instructing him to go wash in a pool. Occasionally, Jesus asks probing, almost offensive questions first, “Do you want to be made well?”

In the church, we lay hands and anoint heads with oil.

But with Jesus, there is no one-size-fits-all approach.

There is a strange simplicity to Jesus; namely, he is not predictable. But he is good.That Jesus does not heal the same way twice is not just an exegetical curiosity. These differences are not incidental. They reveal something essential about Jesus. He is not a magician. He is not a technician. He is not a shaman. He is not a doctor operating by prescribed procedures or time-tested traditions.

Sometimes Jesus just is making it up as he goes along. Because he can!He is the LORD.When Jesus heals the man on the mat, he first calls him “Friend” and declares the forgiveness of his sins, a promise only God can promise— a trespass the scribes are right to resist unless Jesus is as he does. He is LORD. This means his actions are governed not by method but by mercy. He is free to heal whomever he heals; he is free to heal however he wills. And because the LORD is Jesus, he is free to heal in a manner that neither meets our expectations nor rewards our religiosity.

The lack of a fixed technique or standard pattern is both liberating and unsettling.

We want formulas.

Which is to say, we want the law: steps to take, commands to keep, procedures to follow. We want to know what it takes to be healed, to be delivered, to have our prayers answered. We want to know how much faith is enough and how little faith is too meager. But the Gospels resist these kinds of calculations.

We want the law because we want to be in charge. But Jesus is God’s one-way love made flesh.The Gospels are not like the directions on my bottle of chemotherapy.

They are the same each month.

Again and again, Jesus heals in ways that defy our expectations. Perhaps even more provocatively, Jesus often heals apart from any apparent act of faith.

Take the man at the pool of Bethsaida—

When Jesus asks him if he wants to be made well, the man doesn’t respond with faith but with a gripe, “I have no one to help me into the pool.” Jesus heals him anyway. The man doesn't even know who Jesus is until later. If healing always required faith, what then are we to make of such stories? If faith were a precondition, these moments would seem to break the rules.

With Jesus there are no rules.

With Jesus there is only compassion.

But perhaps the better conclusion is that there are no rules. There is only the rule of mercy. Jesus heals not because the suffering have earned it with enough faith, not because they’ve performed the right religious gesture, but because he is merciful and moved by compassion. Faith may indeed open us to recognize what God is doing, but God does not wait on us to act before he acts. The mercy of God in Jesus Christ precedes us, carries us, and surrounds us.

Every pastor understands what is at stake in reading these stories well. “If I just had more faith,” hearts always reason, “then maybe God would’ve healed…” The lack of a pattern almost suggests Jesus’ attempt to keep us from weaponizing faith, turning it into a measuring stick or a mechanism of blame. Every pastor has sat in hospital rooms and at gravesides hearing not only grief but guilt— survivors wondering what they did wrong to prevent God from showing up.

But just as God creates from no need in God, the LORD does not first need something from us (faith, obedience, contrition, fervency, desire) in order to have compassion on us. Jesus just is Compassion.He is not waiting for us to believe before he acts. He is awed by the friends who tear the roof off the place— sure, but they do not need to tear the roof off of the place in order for Christ to incline his heart to their poor friend. Jesus is not standing back, hands in his pockets, until we pass some spiritual test. Rather, he is already and always on the move, always turning toward the broken, always drawing near in compassion.

Even when we don't know it.

Even when we cannot see it.

Even when we cannot muster the faith to ask for it.

Jesus is the Compassion of God made flesh.

Of course— yes— there are also times in the Gospels when Jesus does respond to expressed faith. The bleeding woman who grabs the seam of his jeans, Jesus praises for her courage and belief. Bartimaeus cries out as stubbornly as the persistent widow, and Jesus rewards him sight.

Faith is not irrelevant. But it is not a hall pass into Jesus’ good graces.Belief is not currency that purchases healing. It is more like a window opened to the light already shining. Jesus does not say, “Because you believed hard enough, I will now do this.” Jesus says, “Your faith has made you well”—as if to say, “You saw what I was already doing, and you stepped into it.”

Healing is not predictable. But it is promised.Every miracle is a down payment on the Future promised by the gospel.

Therefore, healing is not a guarantee but, when it comes, it is always a sign of who Jesus is and the Last Future where he yet lives. The promise is not that all will be healed in the way or time we desire. The promise is that in Jesus all of creation will be healed in the fullness of time.

The apostle Paul understood that the Risen Jesus is not predictable but he is good.

When Paul asked for healing, he received instead a perplexing promise, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” That work is the most honest, hopeful gospel promise we can offer a world that prefers a clear prescription.

Grace is enough.

Healing may come in this life.

It may come only in the next.

Either way, it likely will come in a way we do not expect.

But it will come.

Because, though he’s not predictable, he is good. Whether he speaks a faraway word or smears mud like a toddler into your eyes, whether he heals with a touch or from a distance or only after a lifetime, his mercy does not fail.

This just is the gospel: not that we always get what we want, but that God is always who he says he is in Jesus Christ. This is the fixed point in his ministry. Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 14, 2025

Salvation has Come to this House

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

The lectionary Gospel passage for Sunday is Luke 10:38-42.

It’s odd that so many should turn the Parable of the Good Samaritan into a call to duty when Luke immediately follows it with praise of the sister of Martha. Or at least we think this is that story— the tale of two sisters: one bustling and one still, one doing and one being, one missing the point and the other, we suppose, getting it.

Ironically, very often we fail to mimic Mary. We do not sit with the scripture. We do not attend to the passage as a word through which the Word may pass. Instead we rush to do our work with it and, bustling ahead to our predetermined moral, we miss the mystery happening here.

As with the parable which precedes it, the temptation is to moralize.

Martha is owed an apology from nearly every preacher who has attempted to proclaim this scripture. You’ve heard the sermons, “Don’t be like Martha, be like Mary.” Not only is such moralism the opposite of gospel, it’s far too easy an interpretation— and, in fact, it’s not true to the story as Luke gives it to the church.

Martha, after all, is the one who invites Jesus into their home.“Don’t be like Martha, be like Mary,” is not even faithful to the manner in which Jesus deals with people; the moralistic interpretation turns the Lord of Hosts into a terrible house guest.

July 13, 2025

"The Place to Begin is with Astonishment"

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Matthew 14.22-33

One Sunday after Casey returned from his second tour in Iraq he shook my hand in the narthex and introduced himself as the husband of the young woman I’d seen often in worship and as the father of the baby girl who was always in her arms.

“I guess I didn’t realize you were married,” I said to her and shook Casey’s hand.

“Almost two years,” she replied, smiling nervously, “but— the war and all— this is the first time we’ve gotten to live together.”

Even with a baby tow, checkout clerks surely still carded Jennifer, and Casey’s cheeks were so smooth there wasn’t a chance a razor had ever needed to touch them. Neither one of them looked old enough to be married much less parents.

“She really loves this church,” he said, shaking my hand, “It’s a pleasure to meet you, sir.”

“Sir?” I waved him off.

Casey’s grip was as steady, his countenance as calm as his face was smooth, the look in his blue eyes seemed tranquil. I couldn’t have guessed then that there was already a storm gathering inside him. One Sunday Casey started to wear his dress uniform to worship. “That’s odd,” I thought, “but then again, in every church, especially in the DC area, there’s always a handful of folks who take the whole God and Country line a little too far.”

Another Sunday further down the calendar Casey, unsolicited on his way out of worship after the service, insisted to me that serving as a sniper had in no way effected him.

The Sundays following his insistence turned to swagger, bragging to me of the ISIS soldiers he had killed and how his conscience was not at all a casualty of his deeds. The next Sunday he appeared to take pleasure in turning my stomach describing what he called collateral damage.

A few weeks later, in the middle of the week, he came by the church office to let us know that during the worship services the coming Sunday he’d be armed and patrolling the perimeter of the church parking lot to protect the congregation from a terrorist attack.

That’s when I called Jennifer.

Maybe I waited too long to reach out. Hindsight’s always clearer. We always see the present only as though through a glass dimly. After I relayed my recent encounter with her husband, a wave of grief crashed over her and, like a sudden clap of thunder, she broke down weeping.

A moment later, catching her breath and gathering herself, she softly in to the phone, “It’s like he’s been sucked out to sea.”

At the very back of the Bible, the scriptures conclude with a brief but all-encompassing promise, “…and the sea was no more.”

Water moving at nine feet per second can move an eighth grade wrestler. Just two feet of water is powerful enough to lift a Dodge Ram. In Comfort, Texas the Guadelupe River rose from hip height to over three stories tall in only two hours. Along the river in Hunt, Texas the flow of water increased from eight cubic feet per second to one hundred and twenty thousand cubic feet per second in a little over three hours. Which is why, in the symbolic world of the scriptures, the sea is not a place of tranquility or rest.

The faster the water moves, the greater the force it exerts on a car or a structure or a child at summer camp—that pressure increases proportionally to the square of the water’s velocity.

Again, the physics is theological.

In the Bible, the sea is the opposite of Mary’s womb.The sea is not a space for God.In the scriptures, the sea signifies the world gone wrong, a creation out of control. And yet Jesus can stroll upon the sea in the midst of a squall as easily as if the sea is hard, Hill Country land. He can walk on water. He can even summon Peter to stride upon the sea. Nevertheless! Ambulating upon H2O is not the miracle.

In the miracle of Jesus Walking on Water, Jesus walking on water is not the miracle.In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus has just fed far more than five thousand. After the twelve disciples gather up a dozen baskets overflowing with leftovers, Christ makes them to get into a boat and go before him to the other side of the Sea of Galilee.

The word Matthew uses is ēnankasen.

The verb means to insist, to compel, to constrain.

Thus the American Standard Version translates the opening verse, “And straightaway Jesus constrained the disciples to enter into the boat and go before him to the other side.”

He constrains them to get into the boat and he commands them to journey to the other side.

Jesus wants them in the ship.

Jesus wants them in the ship on the sea.

Jesus wants them in the ship on the sea amidst the storm.

Jesus dismisses the thousands of full bellies, and he retreats up into the mountain to pray. And while the Son prays to the Father, the disciples row towards the far side of the sea. While Jesus is alone in prayer, Matthew reports, the twelve are alone on the water.

Jesus left them at the first watch— dusk. In the middle of the night, when they were twenty five to thirty stadia from shore, three and a half miles from safety, the waves begin to batter the boat. And the verb Matthew employs means to torment or to torture. The boat is being tortured by the waves because the wind— a mighty rushing wind— “was against them.”

This is not simply a storm. This is a deadly storm. This is a squall.

At least a third of them in the boat are fishermen. So they know the danger. And they know now Jesus is worse than asleep in their boat; he is nowhere to be found— all night long. Matthew writes that Jesus does not come to them until “the fourth watch of the night.” In other words, they are alone in the boat, battered by the wind and the waves from dusk until dawn.

Again, Jesus wanted them here; Jesus wanted them in the ship on the sea amidst the squall. In fact, the scripture suggests Jesus ascended the mountain to pray in order to produce this very storm. Just as he used the loaves the fish to test Phillip and Andrew, he uses this storm to teach them about each storm on every sea.

When Christ comes to them at the last watch, their dire straits at first grow still darker. They see him walking on the sea towards them and he terrifies them. They thought they knew him. Now they fear what they suddenly realize they do not recognize in him. They are unsettled that this both is and is not the Jesus they have known. And failing to recognize him, they project onto him what they believe is all there is to be found in a storm at sea, “It is a ghost!”

Notice:

Jesus comes to their battered boat, striding upon the sea, but the storm still rages.Jesus neither rescues them nor rebukes the wind. He instead reveals his true, triune identity. He unveils to them in the boat what he previously announced to Moses from the Burning Bush. Jesus is the Great “I AM.”

“Courage! I AM. Be not afraid.”

As the church father Cyril of Alexandria notes, Matthew fixes Christ’s imperial “I AM” at the very center of this miracle story. He who fed the five thousand is the LORD who rescued Israel from slavery.

The same accompanying, delivering God of whom the psalmist sings:

“Your way was through the sea, O God, your path through the great waters; yet your footprints were unseen.”

“Courage! I AM. Be not afraid.”

Of course he can stride upon the sea.

He can even part the sea two.

In 1933, before his involvement with the Confessing Church led to his exclusion from the University of Berlin, Dietrich Bonhoeffer taught a series of Lectures on Christology. The Confessing Church was a movement of the few Christians who opposed the Nazification of the German Protestant Church. The winds and the waves of that particular storm battered the church nearly into oblivion.

Nonetheless!

On Wednesdays and Saturdays of that summer, from eight until nine in the morning, Bonhoeffer taught students at the University of Berlin about him who is the Great I AM.

In one of the final lectures before his expulsion, his students transcribed him as having said:

“Jesus is not separate from Christ…Christ’s humanity is his divinity…This is one of the first axioms of theology— that wherever God is, God is wholly there.”

Wherever God is, God is wholly there.

If God is in the water of Mary’s womb, God is wholly there. If God is in Jesus, God is wholly there. If Christ is on the sea, God is wholly there.

Of course he can walk on water!God is not subject to creation as we are subject to creation.But again—That God can walk on water is neither a miracle nor a marvel.More than a year after my phone call with Casey’s wife, he asked me to meet him for coffee. He’d been getting help in a support group and meeting with a therapist. The storm hadn’t passed, but it had calmed.

“I don’t need to advice from you,” he told me, holding his cup but not drinking.

“Good,” I said, “despite what church people think, they don’t offer any advice-giving classes in seminary.”

He didn’t laugh. I’d interrupted.

“I don’t need advice,” he said, “and I don’t need a prayer to make it all go away. I don’t even need you to tell me everything’s going to be okay.”

“What do you need?”

“I need you to promise me I’m not alone.”

“That happens to be a promise I can make,” I told him.

One of Christianity’s first and most vigorous intellectual opponents was a second century Roman philosopher named Celsus.

He wrote a critique of the faith entitled The True Word, a work now known only from the response it provoked from the church father Origen.

Like other sophisticated citizens of the empire, Celsus mocked Christianity as irrational, subversive, and offensive to classical reason and established order.

According to Origen, Celsus especially recoiled at the recipients of Christ’s supposed miraculous works.Embracing lepers.

Feeding a horde of hungry poor.

Walking on water to boat of frightened fishermen.

Such acts, Celsus insisted, contradicted every agreed upon conviction about deity. A true god is eternal, no more involving himself in time than he privileges those unworthy of his favor. Celsus especially rejected the claim that Divine Transcendence would stoop to human frailty.

In other words, Celsus found it appalling not simply that Jesus walked on water but that God would come on the water to twelve nobodies.

For Celsus, the absurdity of the gospel was not merely Jesus’ alleged miracle but the company God supposedly keeps.A true God would never be wholly there.

Just so—

Celsus grasped the true miracle better than many believers do.

At the fourth watch, when Jesus comes to them, the storm does not cease. He is present to them in the storm, but his presence with them does not preserve them from the presence of storms. The storm keeps storming. And standing atop the sea— right at the center of the story— Jesus issues his imperial “I AM” statement.

Perhaps sensing the fear of his friends, Peter replies to the figure on the water, “LORD, if it is you bid me to come to you upon the waters.”

Jesus replies, “Come.”

And Peter— his name means “Rock,” remember— sets forth from the ship.

Matthew does not report how far away Jesus is from their boat when he says, “Come.” Matthew does not say how many steps Peter manages to walk on the water. Does Peter plunge immediately under the water? Or does he manage to make it some ways away from the boat? Had he not glanced in fear at the wind, could Peter have walked the whole way on the water? Matthew gives no clue. For that matter, Matthew does not even describe how Jesus saves him.

Panicked and sinking, Peter cries out, “LORD, save me!”

“Jesus,” Matthew writes, “stretched forth his hand and took hold of him.”

Which is to say—

Not only can Jesus stride upon the sea, the weight of the Rock cannot pull Jesus under the water. Peter’s fear and panic is no anchor to Jesus. Peter cannot drag Jesus down into the deep. He is unsinkable.If God is there, God is wholly there.

The next thing Matthew tells us that they are all in the boat together. Does Jesus carry Peter to the boat? Does Jesus simply appear in the boat with Peter as he does behind locked doors on Easter evening? Do Peter and Jesus walk to the boat, side by side, holding hands, on the water? Once again, Matthew does not dwell on any such details.

BECAUSE THIS IS NOT A MIRCLE ABOUT WALKING ON WATER!

“I need you to promise me I’m not alone,” Casey told me.

“That happens to be a promise I can make,” I told him.

And he leaned over the table towards me, like I was about to place the promise in his mouth, “Not only are you not alone. He’s in the boat with you.”

In the Gospel of John, after Jesus issues his imperial “I AM” from atop the water, the evangelist observes, “Then they were glad to take him into their boat.”

And he was glad to come aboard their boat.

He can walk on water.But he wants to be in their boat.He can stride atop the crest of a wave. He does not need to scull against a stirred up sea. He has no reason to sweat the swells and the surf. He can tow them all the way to shore. He can amble along on every froth and ripple and wait for them on the other side. It is not so miraculous. Wherever God is, God is one hundred percent there— of course he can walk on water.

Yes, he can walk on water!

But God wants to be in the boat with them!

He can walk on water. He can summon Lazarus from the tomb. He can make the sick whole as easily as he divided the Red Sea. But he wants to be in the boat.

He stretched out the heavens like a curtain. He poured the oceans from the cup of his palm. He told the mountains where to rise. He calls into existence the things which do not exist. He is Alpha and Omega, the End with a capital E and the Beginning of all things, but he is glad to be in the boat.

With them.

And don’t forget who is in the boat he’s glad to board.

On Easter, Thomas will trust neither the gospel nor the word of his friends. Simon is a Jewish nationalist. Judas is a member of the “Sicarii,” extremist nationalists who pursued political assassinations of Roman officials and Jewish collaborators. What is the Prince of Peace doing including him? Meanwhile, Matthew is a tax collector, colluding with the evil empire that sought to kill Christ in his crib. James and John worried only about their status in Jesus’ administration. And Peter will deny Jesus faster than the Sea of Galilee can swallow him.

But God is glad to get into the boat with the likes of them.

And Jesus is glad to be aboard with you.

This is the miracle. This is the marvel.Not that Jesus can walk on water. Not even that Jesus loves you. Or that he died for your sins.The miracle— the marvel— is that Jesus likes you.You.Not as he can make you.

Not as you hope you will be.

Not as you wish you were not.

You!

Jesus likes you.

He can walk on water.

But he wants to be in the boat with you.

As Robert Jenson says of the gospel:

“The place to begin is with astonishment.”

Astonishment.

He can walk on water, but he wants to be in the boat.

With you.

The apostle Paul writes to the Corinthians that “anyone joined to the LORD becomes one Spirit with him.” In other words, Jesus is not himself apart from you anymore than the Son is himself apart from the Father.

Jesus is not Jesus without you!

And how is that even possible?

Because he asked for it!

And his intercessions never fail.

In the Upper Room, on the night before he dies, Jesus prays to the Father, “As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may my disciples also be in us.”

That is:

On the night he was handed over— the last thought on Christ’s mind— Jesus prays, “Father, I want to be in the boat with_______.”

Father, I want to be in the boat with Kelly.

Father, I want to be in the boat with Konnor.

Father, I want to be in the boat with Marilynn Oliver and John Clarke.

In Kerrville, Texas, the water rose thirty five feet in only five minutes.

Until the sea is no more, storms will keep storming.The disciples were in the boat because Jesus compelled them. Though the waves and the wind tortured them all night long, they rowed towards the other side of the sea in accordance with Christ’s command. In all of the Gospels, this could be the instance of their greatest faithfulness to Jesus’ word and their most steadfast obedience to his will. Yet their faithfulness and their obedience does not protect them from the storm.

Faith is not magic.

Discipleship is not a means to an end.

And Jesus is not a genie in a lamp called prayer; he is your fellow passenger.

Protection from the storms of life is not the promise of the gospel.Quite simply, there is no other way to live the Christian life but in the shadow of the cross. There is no other way to live the Christian life but in suffering because the life your baptism gifts just is Jesus’ own cruciform life.

Yes, Jesus works miracles— yes, of course; wherever God is, God is wholly in Jesus.

Absolutely Jesus works miracles.But the miracle Jesus will not work is undoing what he did at your baptism.He will not take his life away from yours. And his life is cruciform. Therefore, protection from the storms of life is not the promise of the gospel.

The promise is that whatever wind is against you, whichever wave rocks you, whenever the undertow threatens to pull you down, you are not alone.

Not only does God love you— to the cross and back, Jesus likes you. Whether he sits stern or bow, he is glad to be in the boat with you.

Hear me.

This is not a mere metaphor.

You probably assume that you are sitting in the sanctuary of Annandale United Methodist Church.

You are actually sitting in the nave of the church.

The nave is the central part of the church starting at the narthex, where you entered the church, and extending to the altar rail.

Inside the altar rail are the chancel and the sanctuary.

You are sitting in the nave of the church, whence derives the word navy.

That you are sitting in the nave explains why the vaulted roof of almost every church is designed to look like an inverted keel.

Not only is physics theological, architecture is as well— the architecture traces back to this text.

From the very beginning, the Body of Christ identified itself as a boat.

A boat tossed on a sea of disbelief and ridicule. A boat tortured by waves of oppression by evil and by collaboration with evil. A boat with a wind of apathy against it, with a wind of worldliness against it, with a gale of overwhelm against it.

And also, don’t forget, the mast of a ship is a cross.

This is the boat.

You thought you were sitting in the sanctuary. You actually came aboard. And all of you— I’ve been here long enough to know— have known the sea. Some of you have had more than one wind against you. Many of you have been tortured by waves far longer than the fourth watch. I’m looking at a few of you (both here and online) who I know have been rowing and rowing and rowing, thinking you’re the only one in the boat. A few of you, I know, have lost loved ones to the undertow.

I cannot promise you, “No storms!” But I can promise you, “He is glad to be in the boat with you!”This boat. This creaky ship. This ordinary vessel.

He can walk on water.

Of course he can approach us as word and water, wine and bread.

Some come, not aft but fore.

The gospel promise is not protection from the storm.It is provision in the midst of them.You’re already on board— come. Jesus said it is so— the loaf and cup are him. Jesus is God. And wherever God is, God is wholly there.

So come.

Take and eat.

And no matter tosses you to and fro, God will be wholly with you. For no other reason than that he likes not only Casey but you.

Some come.

You’re already on board, stern and aft.

So come.

Not because the seas are calm, but because he is present. Come, because the gospel promise is not that he’ll still every storm, but that he will never, ever leave the boat.

This boat—he’s right here!

Wherever God is, God is wholly here.

And he is glad to be here.

With you.

For you.

Because he likes you.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 10, 2025

God Is as God Does

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

“God,” writes Robert Jenson, “is what happens between Jesus and the one he called Father, as they are freed for each other by their Spirit.”

God is as God does.

Therefore:

Miracles are not discrete intrusions of the divine into the world.

Miracles are how God determines his very own triune identity.

I’m preaching on Matthew 14 this Sunday, in which Jesus walks on water as the disciples are battered all night long by a storm (of Christ’s own making). Such stories are not anomalies interrupting the natural order nor are they proof texts for Jesus’ identity— the “ghost” walking on the water terrifies the twelve all the more. In the scriptures, miracle stories are narrative enactments of God's self-identity. For Jens, miracles are not intrusions from “outside” history, they are constitutive of the story in which God reveals who God is. That is to say, miracles are narrative determinations of the triune God’s identity.

July 9, 2025

"We should not let Jonathan Edwards be buried under the grotesqueries of his popular image."

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

The Old Testament lectionary passage this Sunday is from Amos, a prophet through whom the LORD denounces the wealthy housewives, expresses disgust at his people’s hypocritical worship, and promises a Day of judgment upon unfaithful Israel.

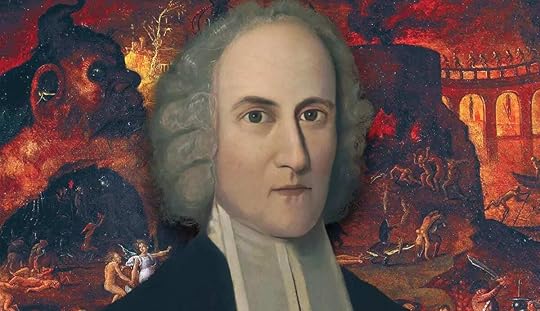

Taking Amos as the scripture passage, two hundred and eighty four years ago yesterday the Holy Spirit catalyzed the Great Awakening through Jonathan Edwards’ sermon in Connecticut, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Thanks to public schooling, Jonathan Edwards has a PR problem. The redacted title of my friend Brian Zahnd’s book betrays the critique, Sinners in the Hands of a Loving God. Somewhere in the ghost of your high school brain is the haunting echo of this sermon— the one in which God’s dangling you over hell like a bored kid with a bug on a string. In many ways (again, see Brian’s book) Edwards is our national mascot for religious trauma. He supposedly epitomizes the toxic Christianity so many young people now wish to deconstruct.

This is unfortunate.

No one should be remembered through the lens of the worst story you recall.“Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” is the only work most Americans know of Edwards, whom Robert Jenson judged to be “America’s greatest theologian.”

Which is exactly why we need Robert Jenson.

In 1992, Blanche Jenson chided her husband for writing so much about dead German theologians but nothing at all about America’s most significant theologian. Just so, Jenson set out to reread and reappraise Edwards’ work, the fruit of which is his wonderful little book, America’s Theologian.

According to Jenson, the Jonathan Edwards we learn in history is a fiction. The “spider-holding, flame-throwing, Puritan terror preacher” is a version we’ve inherited from anthology editors and secular literature professors, not the man his parishioners would’ve recognized. Critically, “Sinners” was a sermon Edwards preached to his own congregation. They knew him and trusted him to deliver a word from the LORD, and he knew them as a pastor knows their congregation and the word they need to hear.

As Jenson points out:

Here is the irony. The preacher we most associate with fire and brimstone was actually a prolific proclaimer of beauty.“The sermon is almost entirely atypical of Edwards’ sermons generally”

Seriously, the real Jonathan Edwards was not like Karl Malden’s preacher in Pollyanna; he was a mystic disguised as a Puritan— a mystic in a wig. Edwards was a philosopher as much as he was a theologian or preacher and for him, above all, Christianity was an aesthetic.

Indeed, I think one of the reasons we have received such a grossly inaccurate portrait of Edwards is that his theological and philosophical writing is too dense and daunting for many preachers to decipher.

Edwards not only saw the world shimmering with God’s glory but he believed beauty is the most determinative shape of the triune God’s being.

As both Lover, Loved, and Witness to their Love— a community of difference and peace— the God who is Trinity is beautiful.The God who creates from nothing makes nothing but beauty. The world, for Edwards, is not a machine built by a distant God; it is Beauty’s love letter, written in the stars and the sacraments.

According to Jenson, beauty is the governing concept in Edwards’ theology:

“Beauty is for Edwards the most basic category of reality.”

Jonathan Edwards was not trying to scare the hell out of us.

He was attempting to wake us up to beauty all around us.

Or as Jenson puts it elsewhere:

“The place for all theology to begin is with astonishment.”

This, at least, is where Edwards also begins.

Edwards’ God is the triune God—eternally joyous, eternally giving. God is not an angry monarch at the top of the universe. God is, as Edwards proclaims him, the one who eternally speaks himself in the Son and eternally loves the Son through the Spirit.

God is music before the notes.

And we are creatures caught up into that melody.

Jenson says it this way:

“Edwards’ God is the triune God of scripture and the creeds, dynamically conceived.”

He means that the fire of God’s life isn’t wrath—it’s love. It is love so intense it burns away everything false. Even God’s judgment is about beauty. Even hell, in Edwards’ vision, is not a sort of divine temper tantrum. It’s the tragic, unnecessary refusal to be drawn into the beauty of God’s joy.

Wrath is no more the main note in Edwards’ theology than it is the main note in the gospel. Rather, wrath is the dissonance that makes the harmony sing.Speaking only for myself, I would not want to remembered for a single sermon I’ve preached. Or, at least let me choose the sermon. Edwards was a revival preacher, yes. But not in the sweaty, manipulative sense. In fact, Edwards was suspicious of what Martin Luther called “enthusiasts.” Edwards’ book Religious Affections is essentially a theological manual for discerning the difference between the Holy Spirit and indigestion.

The real sign of the Spirit’s work, Edwards says, isn’t fear. It’s love. Specifically, it’s a disinterested love for God’s beauty, God’s being, God’s being as such.Again, here is the irony.

Edwards wasn’t trying to save people from wrath so much as awaken them to glory. The aim of the Great Awakening was not to demote Jesus to Secretary of Afterlife Affairs. It was to woo Christians to fall in love with the beautiful triune God.

Though all we know of him today is that image of a wrathful God holding you like a spider over the fire, Edwards would be the first theologian to insist that God is not at all interested in dropping you. In fact, that you exist at all is proof he wants to share his beauty with you.

Edwards’ God burns with anger at sin, yes, because he burns with love for the world.What Jenson helps us to see is that Edwards was never really America’s preacher of fear. He was our first great theologian of beauty. Of joy. Of the triune God whose being is love, not as footprints in the sand sentiment, but as metaphysical fire.

Jens writes:

“If we ask who in our past may provide a theological vision for our future, we should not let Edwards be buried under the grotesqueries of his popular image.”

The hands Edwards said were holding us over hell—those are the same hands that were stretched out on a cross. The hands that gave us bread and wine. The hands that still reach out, not to drop us but to draw us home.

Because in the end, the deepest truth of Edwards’ theology isn’t about spiders or flames, it’s the conviction that the Triune God is so beautiful, so radiant, so all-consuming in love, that even sinners are caught in his glow.

Robert Jenson is famous for ending his two volume Systematic Theology with the promise, “The End is music.”He got the line from Jonathan Edwards. Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 8, 2025

Remember, We Killed Jesus Because of Stories Like This

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

The lectionary Gospel passage for this Sunday is Luke 10.25-37.

A deep cut, here is a sermon from the vault on the scripture.

In front of a crowd of 70 or 140, who's to say how big the crowd really was?

In front of a crowd, this lawyer tries to trap Jesus by turning the scriptures against him. “Who is my neighbor?” The lawyer presses.

It's the kind of Bible question they could have debated for weeks. Read one part of Leviticus and God's policy is Israel first. Your neighbor is just your fellow Jew. Read another part of Leviticus. And your neighbor includes the illegal immigrants and refugees in your land. Turn to another Bible text and the illegal aliens who count as your neighbor might really only include those who've converted to your faith. Your neighbors might really only be the people who believe like you believe. Read the right Psalms and neighbor definitely does not include your enemies.

It's naive, sing those Psalms, to suppose your enemies are anything other than dangerous. So they could have sat around and debated on Facebook all week, which is probably why Jesus resorts to a story instead, about a man who gets mule-jacked, making the 17-mile trek from Jerusalem down to Jericho, and who's left for dead, naked in a ditch on the side of the road.

A priest and a Levite respond to the man in need with only two verbs to their credit.

See.

Pass by.

But, like State Farm, it's a Samaritan who's there for the man in the ditch. Jesus credits him with a whopping 14 verbs to the priest's puny two verbs. The Samaritan comes near the man, sees him, is moved by him, goes to him, bandages him, pours oil and wine on him, puts the man on his animal, brings him to an inn, takes care of him, takes out his money, gives it, asks the innkeeper to take care of him, says he'll return and repay anything else. 14 verbs.

14 verbs is the sum that equals the solution to Jesus' table-turning question, “Which man became a neighbor?”

Not only do you know this parable by heart, you know what to expect when you hear a sermon on the Good Samaritan, don't you? You expect me to wind my way to the point that correct answers are not as important as compassionate actions. That Bible study is not the way to heaven, but Bible— doing. I mean, show of hands, how many of you would expect a sermon on this parable to segue into some real-life example of me or someone I know taking a risk sacrificing time, giving away money to help someone in need? How many of you would expect that? I how many of you all would expect me to try to connect the world of the Bible with the real world by telling you an anecdote?

Exactly.

An anecdote like…

On Friday morning, I drove to Starbucks to work on a sermon. As I got out of my car standing in front of Starbucks, I saw this guy standing in the cold. I could tell from the embarrassed look on his face and the hurried, nervous pace of those who skirted past him that he was begging. And seeing him standing there, pathetic, in the cold, I thought to myself, “Crap. How am I going to get into the coffee shop without him shaking me down for money?”

I admit it's not impressive, but it's true. I didn't want to be bothered with him. I didn't want to give him any of my money. Who's to say that what he'd spend it on or if giving him a handout was really helping him out? I know Jesus said to give to people whatever they asked from you, but Jesus also said to be as wise as snakes. And I'm no fool. You can't give money to every single person who begs for it. It's not realistic. “Jesus never would have made it to the cross if he stopped to help every single person in need, “ I thought to myself.

Mostly I was irritated. Irritated because on Friday morning I was wearing my clergy collar. And if Jesus, in his infinite sense of humor, was going to thrust me into a real life version of this parable, then I was darned if I was going to get cast as the priest. I sat in my car with these thoughts running through my head, and for a few minutes I just watched. I watched as a Starbucks manager saw him begging on the sidewalk and passed by. Then a PetSmart employee saw him begging and passed by. Then some moms in workout clothes pretended not to see him and passed by.

When I walked up to him he smiled and asked if I could spare any cash.

“I don't have any cash on me,” I lied.

I asked him what he needed and he said food. Motioning to the Starbucks behind us I offered to buy him breakfast but he shook his head and explained, no I need food like groceries for my family.

And then we stood in the cold and Jameson, his name was Jameson, told me about his wife and three kids and the motel room on Route 1 where they'd been living for three weeks since their eviction, which came two weeks after he lost hours at his job. After he told me his story, I gave him my card and then I walked across the parking lot to shoppers and I bought him a couple of sacks of groceries, things you can keep in a motel room, and then I carried them back to him. It wasn't 14 verbs worth of compassion, but it wasn't shabby.

And James smiled and said, “Thank you.” And then I took his picture. Tacky, I know. But I figured you'd never believe this sermon illustration just fell into my lap like manna from heaven without a picture. So I took his picture on my iPhone. And then having gone and done likewise, I said goodbye. And I held out my hand to shake his.

See?

Isn't that exactly the sort of story you'd expect me to share?

A predictable slice of life story for this worn out parable right before I end the sermon by saying go and do likewise. And I expect you would go feeling not inspired but guilty. Guilty knowing that none of us has the time or the energy or the money to spend 14 verbs on every Jameson we meet.

I mean, if 14 verbs times every needy person we encounter is how much we must do, then eternal life isn't a gift we inherit at all. It's instead a more expensive transaction than even the best of us can afford.

The good news— The good news and the bad: there's more of the story.

I shook Jameson's hand while in my head I was cursing at Jesus for sticking me in the middle of such a predictable sermon illustration. And then I turned to go into Starbucks when Jameson said, “You know, when I saw you as a priest, I expected you'd help me.”

And then it hit me.

“Say that again?”

“When I saw who you were,” he said, “The collar. I figured you'd help me.”

And suddenly it was as if he'd smacked me across the face.

We've all heard about the Good Samaritan so many times, the offense of the parable is hidden right there in plain sight. It's so obvious we never notice it.Jesus told this story to Jews.The lawyer who tries to trap Jesus, the 72 disciples who've just returned from the mission field, the crowd that's gathered around to hear about their kingdom work— no matter how big that crowd was— every last listener in Luke chapter 10 is a Jew.

And so when Jesus tells a story about a priest who comes across a man lying naked and maybe dead in a ditch, when Jesus says that the priest passed him on by, none of Jesus' listeners would have batted an eye. When Jesus says, so there's this priest who came across a naked, maybe dead, maybe not even Jewish body on the roadside, and he passed on by the other side, no one in Jesus' audience would have reacted with anything like, “That's outrageous!”

When Jesus says, there's this priest, and he came across what looked like a naked dead body in the ditch, and he crossed by on the other side, everyone in Jesus' audience would have been thinking, “What's your point? Of course he passed on by the other side. That's what a priest must do.”

Ditto the Levi.

No one hearing Jesus tell this story would have been offended by their passing on by. Not a one would have been outraged. As soon as they saw the priest enter the story, they would have expected him to keep on walking. The priest had no choice for the greater good. Now, according to the law, to touch the man in the ditch would ritually defile the priest. And under the law, such defilement would require at least a week of purification rituals, during which time the priest would be forbidden from collecting ties, which means that for a week or more, distribution of alms to the poor would stop. And if the priest richly defiled himself and did not perform the purification obligation, if he ignored the law and tried to get away with it and got caught, then according to the law, he could be taken out to the temple court and beaten.

Now, of course, that strikes us as contrary to everything we know of God.

But the point of Jesus's parable passes us by if we forget that none of Jesus' listeners would have felt that way. As soon as they see a priest and a Levite step onto the stage, they would not have expected either to do anything other than what Jesus says they did.

So if Jesus' listeners wouldn't have expected the priest or the Levite to do anything, then what the Samaritan does isn't the point of the parable.If there's no shock or outrage at what appears to us a lack of compassion, then no matter how many hospitals we name after the story, the act of compassion isn't the lesson of the story. If no one would have taken offense that the priest did not help someone in need, then helping someone in need is not this teaching's takeaway. Helping someone in need is not the takeaway.

A little context.

In Jesus' own day, a group of Samaritans had traveled to Jerusalem, which they did not recognize as the holy city of David, and at night they broke into the temple, which they didn't believe held the presence of Yahweh, and they ransacked it, looted it, and then they littered it with the remains of human corpses, bodies they'd dug up. So in Jesus' day, Samaritans weren't just strangers, they weren't just opponents on the other side of the Jewish isle, they were other. They were despised. They were considered deplorable. mean, just a chapter before this, an entire village of Samaritans had refused to offer any hospitality to Jesus and the disciples. And the disciples' hostility towards them is such that they begged Jesus to call down an all-consuming holocaust upon the village.

In Jesus's day, there was no such thing as a good Samaritan.That's why when the parable's finished and Jesus asks his final question, the lawyer can't even stomach to say the word Samaritan. “The one who showed mercy” is all the lawyer can spit out through clenched teeth. You see, the shock of Jesus' story isn't that the priest and the Levite fail to do anything positive for the man in the ditch. The shock is that Jesus does anything positive with the Samaritan in the story.

The offense of the story is that Jesus has anything positive to say about someone like a Samaritan.

We've gotten it all backwards.

It's not that Jesus uses the Samaritan to teach us how to be neighbors to the man in need.

It's that Jesus uses the man in need to teach us that the Samaritan is our neighbor.

The good news is that this parable, it isn't the stale object lesson about serving the needy that we've made it out to

The bad news is that this parable is much worse than most of us ever realized. Jesus isn't saying that loving our neighbor means caring for someone in need— you don't need Jesus for a lesson so inoffensively vanilla. Jesus is saying that even the most deplorable people, they care for those in need. Therefore, they are your neighbors, upon whom your salvation depends.I spent last week in California promoting my book, which, if you'd like to pull out your smartphones now and order it on Amazon, I won't stop you. On inauguration day, was being interviewed about my book. Or at least, I was supposed to be interviewed about my book. But once the interviewers found out I was a pastor outside DC, they just wanted to ask me about people like you all. They wanted to know what you thought, how you felt, here in DC, about Donald Trump. And because this was California, it's not an exaggeration to say that everyone seated there in the audience was somewhere to the left of Noam Chomsky. Seriously, you know you're in LA when I'm the most conservative person in the room.

So I wasn't really sure how I should respond when, after climbing on top of their progressive soapbox, the interviewers asked me, “What do you think, Jason? What do you think we should be most afraid of about Donald Trump and his supporters?”

I thought about how to answer. I wasn't trying to be profound or offensive. Turns out I managed to be both.

I said:

“I think with Donald Trump and his supporters, I think, Christians at least, I think we should be afraid of the temptation to self-righteousness. I think we should fear the temptation to see those who have politics other than ours as other.”

Let's just say they didn't exactly line up to buy my book after that answer. Neither was Jesus' audience very enthused about his answer to the lawyer's question.

You know, as bored as we've become with this story, the irony is we haven't even cast ourselves correctly in it. Jesus isn't inviting us to see ourselves as the bringer of aid to the person in need. I wish! How flattering is that? Jesus is inviting us to see ourselves as the man in the ditch and to see a deplorable Samaritan as the potential bearer of our salvation. Jesus isn't saying that we're saved by loving our neighbors and that loving our neighbors means helping those in need. No, Jesus is saying with this story what Paul says with his letter, that to be justified before God is to know that the line between good and evil runs not between us and them, but through every human heart, that our propensity to see others as other isn't ideological purity, it's our bondage to sin.

All people, both the religious and the secular, Paul says, all people, both the right and the left, Paul could have said, both Republicans and Democrats, both progressives and conservatives, both black and white and blue, gay or straight, all people, Paul says, are under the power of sin.

There is no distinction among people.

Paul says, “Because all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. No one is righteous, not one. Therefore, you have no excuse. In judging others, you condemn yourself, Paul says. You're storing up wrath for yourself.”

So if you want to be justified instead of judged, if you want to inherit eternal life instead of its eternal opposite, then you better imagine yourself as the desperate one in the ditch and imagine your salvation coming from the most deplorable person your prejudice and your politics can conjure up.

Don't forget, we killed Jesus for telling stories like this one.And maybe now you can feel why. Especially now. Into our partisan tribalism and our talking past points, into our red and blue hues, our social media shaming, into our presumption and our pretense at being prophetic into all of our self-righteousness and defensiveness, Jesus tells a story where a feminist or an immigrant or a Muslim is forced to imagine their salvation coming to them in someone wearing a cap that reads, Make America Great Again. Jesus tells a story where a tea party person is near dead in the ditch and his rescue comes from a Black Lives Matter lesbian. Where the Confederate-clad redneck comes to the rescue of the waxed-mustached hipster. Where the believer is rescued by the unrepentant atheist. A story where we're the helpless, desperate one in the ditch, and our salvation comes to us from the very last type of person we would ever choose. And when Jesus says, go and do likewise, he's not telling us we have to spend 14 verbs on every needy person we encounter. I wish. He's telling us to go and do something much costlier. And countercultural.

He's telling us that even the deplorables in our worldview, even those whose hashtags are the opposite of ours, even they help people in need.

Therefore, they are our neighbors.

Not only our neighbors, they are our threshold to heaven.

It's no wonder why we're still so polarized.

After all, we only ever responded to Jesus' parables in one of two ways, wanting nothing to do with him or wanting to do away with him.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

July 6, 2025

5 + 2 + X = 5000+

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

John 6.1-15

Just a day after Passover—

On Easter Sunday 1964, Martin Luther King Jr. languished in a Birmingham jail cell under the charge of parading without a permit, a crime deemed serious enough for solitary confinement. With their leader imprisoned, the movement refused to relent. Civil rights activists planned a march from New Pilgrim Baptist Church to the Birmingham city jail on Easter afternoon. Over five thousand followed the LORD from New Pilgrim to the city jail on that Easter Sunday.

As Andrew Young recalls in his book An Easy Burden: “By the time church ended some five thousand people had gathered dressed in their best Sunday clothes.” The marchers set out in a festive mood, confident they were not marching but following. Suddenly they saw police, fire engines, and firemen with hoses in front of them, blocking their path. The Commissioner of Public Safety, Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor bellowed through a loudspeaker, “Turn this group around!”

Theophilus, the addressee of Luke’s Gospel, means “Friend of God.”