Jason Micheli's Blog, page 3

September 1, 2025

“There is more to the Holy Spirit’s work than pointing toward the memory of Christ’s once for all work.”

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

“Western teaching that the Spirit proceeds “and from the Son” is the failure to acknowledge the saving work of the Spirit as the Spirit’s own new and particular initiative.”

The Nicene Creed celebrates its 1700th anniversary this year. However, for more than half that timespan the church in the West has not professed the creed in identical fashion with her ancient brothers and sisters. The four little words which the West added to the Nicene Creed approximately a millennia ago matter for all things that matter.

In his book on the basic flaw in ecumenical theology, Unbaptized God, Jenson argues that the conception of God in the Western imagination remains essentially unconverted by the gospel. Once again, the title distills his thesis. The God in whom most Christians believe is neither the Nazarene who submits to John’s baptism of repentance nor the one he called Father who entered into time to affirm his relation by the Spirit.

Speaking of the sense of futility that besets ecumenical discussions, Jenson writes:

“The repeated achievement of convergences never adds up to convergence, something deep in the conceptual-spiritual structure of the church’s life seems endlessly to pose and enforce choice between polar positions.”

The reason conversation between Christians from East and West, and, within the latter, Catholics and Protestants, feels pitted according to polarities is that we share “an incompletely christianized interpretation of God.”

Since the ninth century, the church in the Eastern church has diagnosed a failure of the church in the West to apply the gospel fully to its doctrine of God. The tiny clause which the West inserted into the Nicene Creed (“…who proceeds from the Father and the Son…”) is the root of deep distortion. The so-called Filioque Clause, Robert Jenson concedes, is not an embellishment— a bit of interior design— added to the creed so much as an un-permitted addition to the foundation of the faith. The result, Jenson argues, is a church that can’t find its center.

Forget God the Holy Spirit and you end up seesawing between two bad poles.

“Either the church as institution is detached from the genuine event of salvation,” Jenson suggests— ie, the church is not the miraculous creation ex nihilo of the Spirit at Pentecost— or the institution itself is regarded as sacral, as a direct result of Christ’s commission.” The church as the human voluntary association of believers (much of the Protestant Church) lies at the end of the first pole while the church as divinely-sanctioned authority (the Roman Catholic Church) lies at the other pole.

The latter pole begets rigid institutionalism.

The former produces hyper-individualized spiritualism, where every believer is their own pope, and every new idea comes stamped with the Spirit’s supposed approval.

Jenson cites the Orthodox theologian to diagnose the deficiency in both:

“The institution of the church is not seen as a charismatic work of the Spirit.”

In other words, we’ve turned the Spirit into a kind of divine assistant, tethered to the Son, instead of recognizing the Spirit’s free, personal agency in the Triune life and, by extension, the life of the church.

Jenson asserts that the Orthodox Church in the East is correct in their critique of the Western body of believers. Pentecost is not simply an event that happens after the conclusion of the story of redemption at Ascension (which is exactly how the church often proclaims God’s salvific work). Pentecost is the Holy Spirit’s “new and particular initiative” in the life of God and in the life of the world. Pentecost is not a memory; it is a miracle, according to which alone can the church account for her existence.

When the church earlier professed that the Spirit proceeds “from the Father,” she safeguarded the Spirit’s personal freedom. The alternative, the Filioque Clause now confessed in the West’s redaction of the Nicene Creed, collapses the Spirit’s work into Christ’s work, as if the Spirit is only there to remind us of something Jesus already did, long ago, in a Galilee far, far away.

There is more to the Holy Spirit’s work than pointing toward the memory of Christ’s once for all work.

And when that happens, when the Spirit’s work collapses into the work of the Son, Jenson suggests, the church can no longer identify miracles, she loses her prophetic voice, and she reduces the gospel either to authoritarian nostalgia or to an anxious scramble to reinvent the church to every perceived need for relevance. By contrast, when the church understands herself to be the creation of the Holy Spirit, tradition is no longer the static archive of the past but the dynamic, living ways in which the Spirit has made history with her.

As Jenson writes:

“Tradition is a living actualization of the past, a true anamnesis, a synthesis between what is transmitted and present experience, brought about by the Invocation of the Spirit.”

And because the Holy Spirit is “the power of the Risen Jesus,” every eucharist and baptism, every proclamation of the Word, every communal prayer just is the Spirit knitting the church’s “then” to the church’s “now” and pulling the church toward her “not yet.”

Tradition, in this sense, is the Spirit’s choreography, the continuity of God’s people across time because “the Spirit continuously creates it.”If this is true, then the church is never just a human project. Nor is the church ever merely a historical society founded by something Jesus did once upon a time.The church is, in Jenson’s words, “the continuing creation of the Spirit.” Again, Pentecost is not a memory. Pentecost is the first labor pang of new creation, making Jesus’ Risen Body— the church— a community animated moment by moment by the Spirit’s presence.

This means the things we often pit against each other—the institutional versus the charismatic, the hierarchical and the spontaneous— are not opposites at all.As Jenson explains:

“The office is charism, since the Spirit, the living Giver of life, is the source of the church’s office. Office and gift, structure and freedom, belong together because the Spirit is free to breathe both into Jesus’ body.”

With this, Jenson makes his boldest but most characteristic claim, connecting the Holy Spirit to the Last Future where Jesus now lives as its first resident. Jenson insists that the Spirit does not merely make the church continuous with its past (eg, an episcopacy established by apostolic succession), the Holy Spirit also makes the body of believers continuous with its End.

The Holy Spirit makes the body of believers continuous with its End.

Jens says:

“It is an implication of a “pneumatological” Christology, that the historical present of Christ is eschatological. Where the Spirit acts, he makes history enter into the last times, bringing to the world the foretaste of its final destiny.”

Just so, once again— every eucharist and baptism, every uttered prayer, every act of witness…it is not just about maintaining continuity with the past; it is about anticipating the Future. Quite literally, in all these acts the Holy Spirit pulls the community forward into God’s promised Future. This is why Jenson says the church’s continuity through time is eschatological. The church is eschatologically self-identical through time, identical with itself in each present in that in each present it anticipates the one end.

Why do four little words added to the church’s dogma matter?

According to Jenson, the difference— the takeaway— is as unsettling as it is exhilarating.

God has not stopped speaking.

The Spirit has not stopped acting.

The church is not the kingdom movement begun by the dead Jesus.

That she is his risen body, animated by his Spirit, is no mere metaphor.

The same Spirit who hovered over the waters in Genesis, who overshadowed Mary, who fell like fire in Jerusalem, is the Spirit delivering the church even now into the promised Last Future. Forget this item of dogma, and you’re left with the insufficient polarities which beset the church in the West.

On the one hand, a sterile bureaucracy incompatible with a message that just is a promise about the Future.

On the other hand, a free-floating individualism that is anathema to the gospel of Mary’s boy and Moses’ LORD.

But remember this dogmatic claim—recover the Spirit as the Spirit—and suddenly the church stops being a relic of the past and becomes what it was always meant to be: a people animated by God’s future, living signs of the kingdom breaking in.

This is why Jenson keeps pressing on his title phrase. Our problem is not just a matter of language; it’s a matter of imagination. As it turns out, the Holy Spirit is our unbaptized God. We left our pneumatology on the shore of the Jordan River, unconverted to the gospel. And until we let the Spirit be the Spirit—personal, free, and eschatological—the church will keep spinning its wheels, caught between nostalgia for what was and anxiety about what might be.

According to Jenson, here is the good news. Like the Dude, the Holy Spirit abides.

He writes:

The ordinary life of the church is charismatic. To be a charismatic Christian, a believer need do nothing more than listen patiently when a lector invites him or hear, “Listen for the Word of the LORD.”“By the term Holy Tradition, we understand the entire life of the church in the Holy Spirit… dogmatic teaching, liturgical worship, canonical discipline, and spiritual life… together they manifest the single and indivisible life of the church.”

Put differently, forget the Holy Spirit and you no longer can see her at work in the ordinary life of Jesus’ body. In this, we are of all people the most to be pitied, for we have blinded ourselves to our reasons for hope.

The offices are gift.

This is good news of great joy.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 30, 2025

“The common Christology of the Western Church will not support the Christian religion.”

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In light of our study of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s “Lectures on Christology” (HERE is the link to join us live on Monday at 7:00) I have been rereading Robert Jenson’s analysis of the basic flaw in ecumenical theology, Unbaptized God.

The title tells it all.

Jenson asserts that the millennia-old divide between East and West as well as, within the West, the Catholic and Protestant disputes over justification, real presence, and the office of episcopacy all come down to the church’s failure of nerve at and after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD. Having settled the threatened schism by defining the nature of Christ as being “fully divine and fully human in one person without confusion or separation,” the council nevertheless failed to make the claim demanded by a straightforward reading of the scriptures; that is, the second person of the Trinity is God.

Various differences and divisions beset the church still, Jenson argues, insofar as Christians continue to attempt to conceive of God without fully paying attention to Jesus. We try to interpret the Father through the Son, yes, but somewhere along the way, Jenson suggests, we keep flinching.

We refuse to be converted completely from the prejudices of the religion of Plato; consequently, Jesus— as deity— embarrasses us for the same reasons much of the church flinched from professing that Mary is the Mother of God. Apart from resurrection, Jesus is bound by time and he suffers all of time’s vulnerabilities. He is incarnate deity.

Quite simply, the flinch fractures everything, Jenson says, because the God unveiled in Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim is irreconcilable with “what the world already knows about God and the world.” The antique Mediterranean world into which the apostolic mission ventured with the gospel held that God is eternal and untouchable, unmoved by and immune to the tragedies of time.

From Chalcedon forward, the church in the West, in both its Catholic and Protestant forms, continued to try to splice Jesus into that antique template. It does not work.Jenson writes that religion—any religion—has one fundamental purpose: to contend with the jagged edges of our lives, to reckon with eternity’s threat to time. Specifically, the clock ticks, loved ones die, democracies wither, and we try to find a thread that makes it all hold together.

Religion posits “eternity.”

In other words, religion offers a sense of coherence in the face of finitude’s threat of meaninglessness. Different religions pick different shapes for eternity. Some make eternity impersonal, like an eternal principle or the Force from Star Wars. Others, sensing that eternity has to have a face, turn it into a god—or lots of gods—who are personal and responsive.

Christianity, Jenson argues, says to religion: You’re all wrong and you’re all right at the same time.

Christianity says to religion: You’re all wrong and you’re all right at the same time.

Eternity, it turns out, isn’t just a timeless principle or an abstract infinity; eternity has a name. Eternity is Jesus, the man from Nazareth. And Jesus doesn’t just reveal eternity—he redefines it.

Unlike their descendants, the ancient church fathers did not shirk from scandalizing the intellectual world of their time. Contrary to popular assumptions, the doctrine of the Trinity is not a clever capitulation to Greek thought; it is an explosion of it.

On the one hand, the Greeks held that “God is perfect, and perfection means no change in deity, no suffering by deity, no messy entanglement of deity with time.”

On the other hand, the gospel announced a counterfactual, “Actually, that God—Jesus, the one born from Mary, the one sweating in Gethsemane and bleeding on Golgotha—is fully God.”

By discovering the personal name of God— Father, Son, and Holy Spirit— the church borrowed the best Greek words and philosophical frameworks and then happily detonated them.

To an extant not appreciated by believers today, the creeds produced by Nicaea and Constantinople upended an entire worldview.

Jesus is not God because he somehow escaped time. Jesus is God because his infinite liveliness fills every moment of time.God is not an impassible statue. God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—eternally alive, eternally moving, eternally for us.According to Jenson, the rub is that even inside the church believers responded to counterintuitive news of the gospel by gripping tightly to their old religious assumptions. So when Cyril of Alexander, for example, followed the logic of the scriptures by saying “God suffers,” much of the church balked.

The Greeks had drilled it into religious heads: If God is really God, then— by definition— he cannot really suffer.

Eternity means impassibility.

In a move that still discomfits the pious, the church fathers proclaimed the paradoxes demanded by the gospel:

“The Impassible suffers.”

“The Deathless dies.”

“The paradoxes,” Jenson writes, “must be swallowed.”The church’s failure to see these specific paradoxes as the beating heart of the gospel is the basic flaw in all the problems that divide Jesus’ body, Jenson believes.

If God doesn’t suffer in Jesus Christ, then Good Friday is just a morality play. And Easter is nothing more than a metaphor. Of course, Friday’s cross and Easter’s tomb are these very reductions in much of the church.

As Jenson puts it:

“The common Christology of the Western Church will not support the Christian religion.”

Jenson sees our abiding dilemma in the ancient dispute between the Christologies proffered by the church at Antioch and the church at Alexandria, the forming becoming the Christianity of the West and the latter the East.

Antioch did not swallow the paradoxes, taking care to affirm Jesus’ divinity but stipulating that his suffering and death happen only to Jesus in his human nature and not to the divine Logos.

Alexandria— represented best by the father Cyril of Alexandria— saw what was at stake. If Jesus isn’t fully God and fully human in one inseparable person, then the cross is no more than theater and the Son’s salvific work collapses.

Alexandria thus added more paradoxes to the church’s mouthful, “One of the Trinity suffered.”

The Council of Chalcedon, in Jenson’s analysis, was an awkward truce that was perhaps necessary for the short-term stability of the church but has proved insufficient for the church’s unified witness to the gospel. Jenson says the Chalcedonian formula—“one person in two natures, without confusion, without division— was less a solution and more of a ceasefire. The Antiochenes could keep their neat separation between divinity and humanity, and the Alexandrians could cling to their radical unity.

The core question (How can the eternal God truly suffer in time? How can Mary give birth to her Maker?) never got resolved. The church has still not resolved it. All our other differences and divisions trace back to this unanswered question.The consensus position in the West following Chalcedon came from Pope Leo, “Each nature does its own thing, in cooperation with the other.” It begets all manner of unhelpful questions; such as, when Jesus turned water into wine, did he do that in his divine nature, flicking off the switch that read “Truly Man?” This makes it sound like Jesus is a two-person partnership, the human side doing the suffering, the divine side staying above the fray. Augustine doubled down on this problem by returning to the pagan prejudice that God as impassible. And so, in practice, Western theology started treating the union of the divine and human natures of Christ as a logical assertion instead of a lived, salvific reality.

By the time Anselm arrived in church history with his theory of atonement, Jenson notes, the split between Christ’s natures was already deeply ingrained in the church’s Christology.

Thus in many presentations of Cross and Resurrection:

Jesus’ humanity paid the debt of sin.

His divinity stamped the payment “infinite value.”

It is often observed that Anselm’s theory of the atonement presents the work of the Trinity as transactional. It is less well noticed that its deficiencies stem from the Western Church’s antecedent division of Christ in his human nature and Jesus in his divine nature.I think Jenson is right to character this rupture in Christ’s person as leaving us a faith that feels frankly hollow. If the events disclosed by the gospel never truly touch the Godhead, then the LORD is not triune, the Father remains “up there” and Jesus’ suffering merely happens “down here” and happens— importantly— only to him. We are not, as Paul proclaims, crucified with him. And therefore, his resurrection is not the new reality into which the church has baptized us.

Just so, Jenson argues, the church splinters.

Catholicism starts finding salvation in other foundations: sacraments, saints, systems.

Protestantism, meanwhile, throws up its hands and starts jettisoning core affirmations it no longer knows how to conceive.

Liberalism then makes wisdom or experience the foundation of its “Christianity.”

Again:“The common Christology of the Western Church will not support the Christian religion.”The divisions of the church, Jenson says, are due to the fact that we’ve inherited the tension between Antioch and Alexandria without really interrogating the assumptions underneath it; namely, our assumptions about what “eternity” and “God” means.

Jenson offers a way forward.

What if the problem is not Jesus? What if the problem is the God to whom we keep trying to accommodate Jesus?Jenson’s point— indeed the gospel’s claim— is that the triune God doesn’t need our categories of “impassibility” and “immutability.”

God is not threatened by time.

God is the LORD of time.

And Jesus is not the exception to the rule of eternity. He is the rule.If eternity is what we see in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, then eternity is not static perfection. Eternity is movement, communion, and love that refuses to stay distant from suffering. In other words, the cross is not an exception to how God is God. The cross is who God is.

Following the religion of Plato, the church keeps asking, “How can God, who is eternal, suffer the effects of time?” But maybe the better question is, “How could eternity ever be anything other than the God revealed in Jesus—the one who enters our time, suffers our death, and raises us into his endless life?”

Swallow the paradox for it just is the scandalous, saving good news.

The eternal God has scars.

The true God is baptized.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 26, 2025

Humility is Not Ambition in Disguise

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

The lectionary Gospel passage for this coming Sunday is Luke 14:1, 7-14; it is yet another example of editors attaching spectacularly terrible headings to pericopes of scripture— in this case: Invite the Poor to Your Banquet. No matter what the publishers would have you believe, this passage is gospel, not law— a word of sheer gift, not another demand added to your ledger.

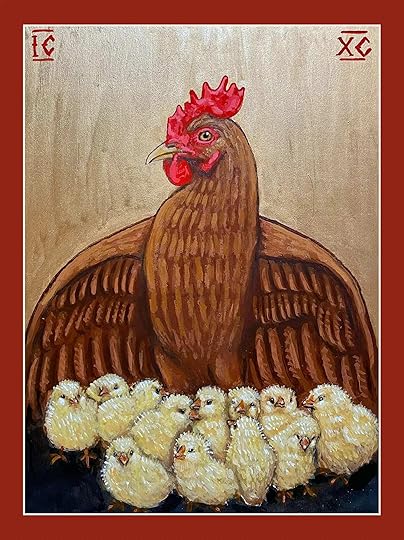

At this juncture in Luke, Jesus has just named Herod — and the forces of death with him — a fox. And he has named himself our Mother Hen, making us — pay attention — the brood sheltered beneath her wings. That image is not incidental; it’s a preview of what Jesus is about to do to death.

It is a prediction of what Jesus is going to do to death.

In the very next scene, Jesus, as he’s wont to do, offends his dinner companions by healing a man with dropsy on the sabbath. “Which of you,” Jesus asks the Pharisees and lawyers, “having a son or an ox that has fallen into a well on a Sabbath day, will not immediately pull him out?” When they stare at the floor, bested, Jesus presses the matter by spinning a parable about a wedding banquet. At the story’s end, with a quiet voice that carries its own authority, he says:

“When you are invited to a wedding feast, don’t take the best seat. Someone more important than you might come, and the host will tap you on the shoulder and say, ‘Move down,’ and you’ll shuffle off in shame to the lowest place. Instead, go sit in the lowest seat, so when the host sees you there, he’ll say, ‘Friend, come up higher,’ and you’ll have glory in the sight of everyone. For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

And we hear it wrong every time.

Invite the Poor to Your Banquet

We hear “humble yourself,” and we think Jesus is handing us a strategy — that the way to climb the ladder is to start on the bottom rung, as if humility were just another form of ambition in disguise. In other words, we mistakenly believe Jesus is exhorting us to manufacture humility; such that, the gospel is ultimately ordered to merit and demerit after all.

But Jesus isn’t handing out homework.

The key to the parable is the image which preceded it: Christ sheltering her brood beneath her wings agains the onslaught of Death.The point is death.

August 25, 2025

Jesus Does Not Live By Faith

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Hi Friends,

We will not meet tonight to discuss Bonhoeffer’s “Lectures on Christology.” One of my dogs, Vaughn, is in the hospital, and I’m feeling blue. We will gather again next Monday to work our way through these pages:

Bonhoeffer Reading 42.46MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadJesus Does Not Live By FaithRemember how Bonhoeffer began these lectures by emphasizing the who question, “Who is Christ?” Dismissing both speculative abstraction and reductive historicism, Bonhoeffer insists that Christology is reflection upon the living, risen person present now in the church. He cautions against turning Christ into an idea or merely a moral force and insists that Christ must be experienced as the Risen One present in word and sacrament. Jenson, likewise, takes a complementary path, arguing that theology must begin with God’s self‑identification in the gospel narrative—most decisively, the raising of Jesus from the dead. Thus Jenson believes the answer to Bonhoeffer’s question, “Who is Christ?” is necessarily triune; that is, the who of Christ and the who of God converge in the gospel— in the history the LORD makes with us.

It is important to see that for both Bonhoeffer and Jenson— following Karl Barth— theology cannot start with an a priori concept of God. As Jens jokes, “what everyone knows about God” is antithetical to the gospel. Rather than beginning with our assumptions about deity, we must commence with the God revealed in the scriptures.

Our starting point for thinking about God is his narrative identity.

Not metaphysical attributes.

The church makes this very claim every time it utters God’s personal name: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The plain reading of the scriptures, Bonhoeffer and Jenson both insist, reveals nothing short of the claim that the second identity of that personal name, the second person of the Trinity, is Jesus of Nazareth. It’s the Bible not metaphysics that yields the Chalcedonian Formula:

“For us and for our salvation, of Mary the Virgin, the Godbearer;

one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten,

recognized in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation;

the distinction of natures being in no way annulled by the union,

but rather the characteristics of each nature being preserved and coming together to form one person and subsistence,

not as parted or separated into two persons,

but one and the same Son and Only-begotten God the Word, Lord Jesus Christ.”

Yet Bonhoeffer deepens the Chalcedonian Formula by emphasizing the concrete, paradoxical unity: the eternal enters into time, the divine enters humanity— human history— humiliated and vulnerable, and yet remains the exalted and holy LORD. Christ genuinely suffers and lives under human limits simultaneously without ever ceasing to be God!

Christ does not live by faith. Christ is the humanity of God.

For example:

This is why the Gospels do not report a single instance of Jesus’ prayers to the Father going unanswered (as our prayers often seem to go unanswered). Jesus does not say before Lazarus’ tomb, “I wonder if the Father will do what I’m about to ask?” Christ does not live by faith as we do because Jesus does not ever cease to be God.

Christ does not live by faith as we do because Jesus does not ever cease to be God.

Jenson affirms Bonhoeffer’s emphasis by pointing to the crucifixion. The cross is not the suspension of God’s being, but its fullest revelation. For Jenson, God’s identity as the crucified and risen One integrates the divine life with human history. As God does in the Gospels, so God is.

The Chalcedonian Formula distills a mystery that Bonhoeffer believes we must enter with humility. Acknowledging how of the incarnation is not fully knowable by us, Bonhoeffer stresses that obedience to Jesus means remaining obedient to the mystery.

The Who in “Who is Jesus?” must be confessed.

The How in “How is God Jesus?” can never be demystified.

Faith embraces mystery.

Theology narrates mystery.

It does not solve it.

A good example of the mystery Bonhoeffer theology narrates but does not solve is the genus majestaticum, which he discusses in the attached lecture notes. Simply, the genus majestaticum is the doctrine emphasized by Luther but present in church fathers like Cyril of Alexandria. It stresses the union of Christ's divine and human natures. Thus, Christ's human nature is suffused with divine attributes, meaning that his humanity receives and shares in the qualities of his divinity, such as omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence.

As Bonhoeffer says of Martin Luther:

“Luther spoke of the divinity and humanity of Jesus as though they were one nature.”

The humanity of Jesus is fully suffused with the life of God.

Jesus never ceases to be God, even as Jesus ceases to be.Only this unity of humanity and divinity in Jesus, Bonhoeffer argues, makes redemption possible — for if Christ were not truly God, his suffering and death would be meaningless for salvation. At the same time, Bonhoeffer engages the “two states” of humiliation and exaltation, teaching that in his earthly life Christ voluntarily refrains from the full exercise of his divine attributes. This is not a denial of divinity but a self-emptying (kenosis) that allows the eternal Word to live authentically as a human being in time and space, sharing fully in our creaturely condition while remaining the eternal Son.

Bonhoeffer notes that the humiliation of Christ— his living incognito among sinners, even to the point of taking on the likeness of sinful flesh— is not a diminution of his divinity but its truest revelation.

Or, as Jenson puts the same point:

Good Friday forever settles God’s identity. Just as Jesus’s death settles Jesus’s identity once and for all, the resurrection now determines who God is— the Father is now forever the Father of this crucified Son.

For Bonhoeffer, Christ’s majesty is hidden under the form of a servant, revealed not in omnipotence or omniscience but in his gentleness and humility, in his suffering and death for others. In this sense, Bonhoeffer’s “Lectures on Christology” advance what Bonhoeffer calls a “positive Christology” in that it is one which first begins with the concrete reality that Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim is God and only then contemplates what that means.

The paradox of the humiliated and exalted Christ resists speculative resolution and calls instead for faith: to recognize, by the Spirit, that the true and living God has a mother and an executioner.

What else can you do with such a mystery but handle it with care?

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 24, 2025

Merciful Surprise

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Mark 5.21-43

The key to this passage is the verse immediately before it.

Having loosed a legion of demons from a Gerasene, Jesus commands the otherwise unnamed man, “Go home and to your friends, and tell them how much the LORD has done for you, and how he has had mercy on you.” The former demoniac in fact sets forth for the Decapolis where he proclaims— note his redaction, “how much Jesus had done for him.” It is the only instance in the Gospel of Mark where the Evangelist applies to Jesus the term reserved exclusively for Almighty God.

Thus, the passage across the Sea of Galilee is the fulcrum of Mark’s Gospel. In Christ's encounter with the Gerasene demoniac, the Evangelist unveils surpassingly more than the authority of Jesus over Satan and his minions.

When Jesus and the twelve return from the far side of the sea, a throng surrounds them on the shore. As the crowd presses into him, a nameless woman creeps close, bearing a sickness no could see. While Jesus follows the fearful father to his dying girl, the woman approaches him from behind, covertly squeezing herself through a blockade of shoulders and sandaled feet. Anonymous amidst the thrum of desperate need and idle curiosity, she stretches out her hand, as if to pick his pocket. Her fingertips cross an invisible threshold, as though she has passed through the Temple Veil. Instantly a discharge of power leaks from him. His body— contaminates seems the wrong word— her body. And she is healed.

See:

The nameless woman’s touch confirms the former demoniac’s speech.This Jesus is God “deep in the flesh.”This is the key to this story — indeed it is the key to all our stories.Jesus is God deep in flesh.

Joseph Awuah-Darko is a twenty-eight year old artist from Ghana. From one of his nation’s wealthiest families, Joseph grew up in a mansion in Accra where his father kept a stable of horses imported from Argentina. Joseph was educated at elite schools, pampered by private maids, and fed by professional chefs. As a young adult, the self Joseph projected out into the world through his social media channels reflected this charmed life of privilege. His Instagram featured perfectly framed and meticulously filtered photographs of himself enjoying life.

But then eight months ago, just days before believers would sing “Joy to the World,” Joseph announced on Instagram that his public-facing self was false. For over a decade, he had been hiding a sickness no one could see— keeping it concealed because of its stigma. Joseph Darko does not have a unremitting bleed. He has an unrelenting chemical imbalance in his brain. In December on Instagram, he announced, “The weight of my invisible affliction has become unbearable.”

To the camera, his face wrenched in pain and his eyes soggy with tears, he said, “I’m just so tired. The chemical imbalance in my brain and living with bipolar disorder…I’m just tired. Yes, I’ve thought about this for a long time. Yes, I’ve talked it over with my friends and fiancé. I wake up every day in severe pain. And even when there are highs, the lows are unbearably bad.”

And then the apparently happy artist announced his desire to die, detailing his plans to relocate to the Netherlands and pursue medically-assisted suicide.

In the body of his social media post, Joseph cited the journalist Joan Didion in his farewell message:

“In her 1967 essay “Goodbye to All That,” Joan Didion writes, “I hurt people I cared about and insulted those I did not. I cried until I was not even aware that I was crying.” Words have never resonated with me more deeply. Unlike Didion who was a staunch atheist, I am someone who grew up Christian. So taking this step to share my decision to pursue euthanasia as a personal choice was tough, even taboo. I am not saying that life isn’t worth living. I am saying mine has become impossible. Bipolar exacerbates all this.

My decision may cross a taboo. But I am willing to touch what is forbidden. I’m ready to go home to God— I can’t think of a greater adventure.”

Joseph Darko streamed his suicide note on a Friday in Advent.

Instantly, a former model from Cameroon, a woman named Candace, reached out through the thicket of comments and replies. “Dear Joseph,” she wrote, "I want to honor the deep pain, courage, and vulnerability you have shared.”

But then Candace quickly pivoted away from Joseph and towards this audience. Bracketed by square purple icons of the cross, she attempted to grasp ahold of Joseph by issuing an exhortation:

“To my fellow Christians reading this: I humbly and urgently invite you to lift Joseph in prayer. Let us intercede for him, asking for the miraculous healing of his heart and mind. Joseph, as someone who has overcome years of mental health struggles and the weariness you describe, I want to remind you of the God who sees, loves, and restores—even in the darkest valleys. You have incredible worth, and there is a purpose for your life that extends far beyond the pain you have endured. I have unshakeable faith that God can work a miracle even in your troubled life. Fellow Christians, pray for a miracle.”

With Love and Faith,

Candace”

It did not happen instantly.

But quickly, something happened— power went forth.

As though Jesus is God deep in flesh in ways we cannot begin to fathom.

I wonder if she planned her anguished espionage? Did she choreograph her pick-pocket approach? How long did she conduct her stake-out on the shore, waiting for his boat to return from the far side of the sea? I wonder because this nameless woman is the only person in the Gospels who tries to secret a miracle from Jesus.

The ancient church father Cyril of Alexandria interrogates her actions by asking:

“Why does she draw near and touch the hem of his garment surreptitiously and not openly, hoping, as it were, to steal salvation from one who knew not of it? Why, tell me, was the woman careful to escape notice? What then was it that made this sick woman wish to remain hid?”

Why is she so clandestine about approaching Jesus?

She is so surreptitious because her touch is transgressive.A touch from her is a trespass by her.

Biblical scholars refer to this passage as an intercalation; that is, Matthew, Mark, and Luke alike all sandwich this story of the nameless woman in the middle of the story about Jairus’ dying girl. Thus Mark intends for us to interpret each of these stories by means of the other. For instance, the daughter of the ruler of the synagogue is twelve years old; meanwhile, the nameless woman has suffered an unremitting hemorrhage for twelve years. The intercalation leads us to surmise that this woman’s unseen affliction is the chronic wound left by a miscarriage.

The scriptures do not name this woman with the hidden affliction, but they do supply a title. According to the commandments, she is a zavah, literally a female discharger who endures a long-term, indefinite genital flow. In fact, the opening words of Mark’s passage describe her using the exact legal terminology of the Septuagint’s translation of the Book of Leviticus. Consequently, the synagogue as well as the Temple itself is off limits to her. Jairus does not know her name because she is not allowed in his synagogue. To enter either the synagogue or the Temple would be to cross a taboo, to break a stigma. “Better is one day in your courts,” the Psalmist sings of the Temple in Jerusalem, “than a thousand elsewhere.” But for four thousand three hundred and eighty days, this nameless woman’s hidden affliction has prohibited her from approaching the LORD in his dwelling place for even a moment’s respite.

Indeed, according to the commandments she is forbidden far more than entrance onto holy ground. As the Book of Leviticus stipulates, “Whoever she touches shall be unclean.” In other words, she has mourned the loss of a child without the benefit of another’s embrace. She has wept without a friend’s shoulder on which to cry. She has grieved without a steady hand to hold beside her baby’s grave.

She is more than invisibly sick.She is socially isolated.And it has become unbearable.

She sneaks up like a purse-snatcher in the subway because, while she still bleeds, she is not supposed to touch anyone. She is not supposed to touch anything anyone might touch. The crowd itself should be as off limits to her as the Temple Veil. She should avoid bumping into Simon Peter just as she would be loathe to enter the Holy of Holies. If she accidentally runs into Jairus and then the worried father subsequently touches his little girl whose life hangs in the balance…

If they knew her affliction and if they knew her plan, then they would know she has potentially placed upon them all a terrific burden.

Typhoid Mary did not know she was a carrier of contagion.

But this nameless woman, it is as dangerous as it is desperate.

Back in December, many mental health experts responded to Joseph Awuah-Darko’s social media farewell with alarm and disgust, particularly given his large audience. They accused him of being selfishly reckless for suggesting, as he did, that suicide is a legitimate answer for people with a treatable disorder. Still others worried of the danger he posed to other people, romanticizing suicide to those vulnerable to such desperate gestures. The stigma exists for the sake of safety. “My daughter is in a fragile, emotional and impressionable state,” the mother of a suicidal young woman wrote to Joseph, adding: “You are not helping anyone with this content. I’m begging you to shut it down. Please. Before you take my daughter with you.”

Such dismay and consternation is entirely legitimate— righteous, in fact.

Nevertheless!

Despite the response Joseph Darko’s heedless gesture may have deserved, a merciful surprise happened. Three days after Candace Nkoth posted a plea for her brothers and sisters in Jesus to pray for Joseph— hear it: on the third day— thousands of people from around the world responded by reaching out, getting in touch with Joseph, and inviting him to supper.

Since he announced his desire to die in December, Joseph has received over a hundred and fifty dinner invitations from strangers heeding Candace’s prayer request. He has boarded trains to visit homes in Berlin, Paris, Antwerp and Milan. He has traveled to cities all over the Netherlands and to dozens of Amsterdam neighborhoods. Those who don’t cook have joined him at bistros and even a Burger King.

As of the end of July, Joseph confessed that he had acquired something else unexpected in addition to hundreds of dinners invitations: a reason to live.

After he defeats the Philistines, King David reclaims the ark of the covenant upon which the LORD invisibly dwelt. David transports the ark to Jerusalem with the fanfare of a military parade. At a certain point in the procession, however, the oxen pulling the cart on which the ark rested “stumble.”

The oxen stumble. The oxcart rocks. The ark tips over. And the attendant marching beside the oxcart, a man named Uzzah, reaches out his hand to steady the ark of God to keep it from falling. Uzzah but touches the hem of the ark of the LORD and instantly power goes forth from the ark and the glory of the LORD strikes Uzzah dead.

Jesus is that God deep in the flesh.

Just so—

In touching Jesus, this nameless not only risks public shame and righteous anger, she also risks her life. Like most taboos, the stigma is in place for her safety. She may as well be committing suicide.

What happens instead however is merciful surprise.

In spite of her transgressive touch, despite her trespass, regardless of her reckless desperation, power proceeds from Jesus and instantly she is healed.

In §64 of his Church Dogmatics, entitled “The Royal Man,” the theologian Karl Barth criticizes the Protestant Reformers for not turning to the miracles of Jesus as evidence for their emphasis on grace alone.

Observing that the nameless woman who trespasses by touching the LORD is cured rather than killed, Barth comments:

“We may well ask with amazement how it was that Luther and Calvin could overlook this dimension of the Gospel, which is so clearly attested in the New Testament— its power as a message of mercifully omnipotent and unconditionally complete liberation from suffering. How could Protestantism as a whole possibly overlook the fact that it was depriving even its specific doctrines of justification and sanctification of so radiant a basis by not looking very differently at the miracles of Jesus, by not considering the free grace which appears in them.”

After two sisters served him a Persian diner, a recipe of their mother’s, Joseph admitted that he had been in the midst a depressive episode. “I cried heavily during the latter two hours of the dinner,” he posted, “before they sent me home in a cab with a bouquet of flowers. All I did was show up and they held so much space for me. Maybe there’s hope for all of us.” Meanwhile, the hosts who have received Joseph as their guest frequently express feeling buoyed by “his readiness to speak with candor about his innermost turmoil.” One woman in Rotterdam served Joseph Indonesian fare prepared by her mother, and served in Tupperware. As she described her table fellowship with Joseph, “I’ve also struggled with this in my own life a little bit. That’s why I love to listen. It’s a kind of talk therapy in reverse.”

That is, Joseph is not the only one who has discovered a needful community.

As soon as she touches the hem of his garment she is healed. “Straightway the fountain of her blood was dried up;” Mark reports, “and she felt in her body that she was healed of her plague.”

Yet her story does not stop where her affliction ends.There is more to the miracle.Sensing that power had gone forth from him, Jesus turns to the crowd, “Who touched me?” Again, this is God deep in the flesh. It is not the case he has no idea who touched him. He is testing her. He is seeing if she will trust him enough to come forward. Remember. She does not have friends to dig a hole in the roof for her. She does not have anyone who can throw themselves down at Jesus’s feet and plead, “My friend is at the point of death: I pray thee, that thou come and lay thy hands on her, that she may be made whole.” She sneaks up and touches Jesus because she does not have anyone who will take Jesus to her.

She is not just chronically sick. She is sorely alone. And God did not make her to be either! If Jesus merely staunched her wound, she still would not be whole.

“Who touched me,” Jesus asks.

And note how Mark reports that Jesus turns around and looks right at her, “And he looked round about to see her that had done this thing.” He knows who touched him. But he wants to see if she will reveal herself to them.

Why?

Because if this woman is going be healed of what truly ails her, then Jesus must undo her habit of hiding.“Who touched me?”

Knowing her trespass, she falls down with fear and trembling. She tells the truth, Mark writes. She says in front of everyone, “Jesus healed me. I touched him. I trespassed against him because I had this sickness no one could see— this stigma— and I could bear no longer.”

She unveils the truth. And that act of trust and revelation— that is the faith which Jesus says saves her.

Notice: Jesus does not say “Your faith has healed you.” She has already been healed. Jesus says, “Your faith has made you whole.” And praising her faith, Jesus remedies her final lack. He gives her a name. He calls her “Daughter.”

And by giving her a name, Jesus in fact gives all of them a person for whom they can care in his name; so that, what is grace for her can be joyful obedience for them.In his essay “On Becoming Man: Some Aspects,” the theologian Robert Jenson argues that if the LORD Jesus had stopped short with the woman he calls “Daughter,” healing only her hemorrhage and not her wound of loneliness, then Jesus would have left her less than human.

Jenson writes:

“The mutuality of human existence means that each of us is himself only as part of a larger whole he makes with others— only as an organ of a body. That I am an organ of a community is not a limitation of my humanity; it is its possibility.”

Consider:

Jesus is the first person who has touched her in twelve years.

Mark does not name the woman at the beginning of this story because no one in the little town of Capernaum— the city is smaller than the footprint of the church— knows her name. Do they even recall her lost child? She has gotten into the habit of hiding because no one in the community has gone looking for her. She is able to sneak up on Jesus because they no longer even see her. They have abandoned her to shame and isolation. They may not know her unseen affliction but they certainly know she is alone.

They have left her to be less than human; in turn, they have become a corpse of the body they are meant to be. Her desperate gesture is an indictment of their failure of faithfulness. Therefore, there is more to the miracle.

Jesus does not simply staunch her bleed. Jesus does not merely restore her to the body of believers. Precisely by restoring to her to them, Jesus resurrects this dead community.

They don’t even know her name anymore.

But Jesus gives her to their care.

They do not deserve her!

Just so, he gives them new life.

Like Barth says, if you want proof that God is gracious, look no further than Jesus’ merciful surprises.

Musing on the long string of last suppers that have kept Joseph Darko alive, a journalist for the NY Times writes, “If this is a grift, it might be the world’s lamest. Hosts typically cover Mr. Awuah-Darko’s travel expenses, but he doesn’t receive any money from the meals. So what exactly is Mr. Awuah-Darko up to? What do we call it? Is this a piece of performance art? Unconventional psychiatric treatment? A long goodbye, with catering?”

What is this?

What do we call it?

We know.

It is Jesus.

It is God deep in the flesh.

A few Advents ago, after the Christmas Pageant, one of the children in the cast came up to me in the fellowship hall. “I have a question,” she said.

“What’s your question?”

“So, Jesus is alive?”

I nodded.

She thought about it for a moment.

Clearly this hadn’t been her question.

“Well,” she said, “if Jesus is alive, then how come we can’t see him?”

I knelt over and I leaned in towards her and I whispered, like this was a miracle too delicate to say loudly.

“Actually,” I said, “you can see him; in fact, you did see him just last Sunday.”

“I did?” I nodded.

“Yes, of course,” I said.

“He was that bread on the table and the cup next to it. Jesus is alive and that’s the form his body takes now.”

She nodded.

“Oh, cool,” she said.

And then she ran off as quickly as a magi from the manger.

But of course, I was only half right.

I had not dared her to reach all the way out and touch the mystery.“Now you are the body of Christ,” the scriptures proclaim, “and individually members of it.” As much as loaf and cup, Jesus is present to me— incarnate for me— in the body called you. This is exactly why the apostle Paul commands us that before we come to the altar table we “discern the body.” Before you eat and drink the body and blood of Christ, Paul instructs, apprehend that the LORD Jesus is already here for you, with you, alongside you as the body of believers.

Jesus is God deep in our flesh.Jesus is God deep in our flesh; we are the body of the Risen Jesus.

Not only is this good news, it is a life-saving reminder.

Because notice how this nameless woman’s story ends. While she is being healed, while she is being made whole, and while the community that has neglected her is being raised up— while they’re all receiving a gratuitous miracle, a merciful surprise— Jairus’s daughter has died.

Remember, it is an intercalation. The sandwiched stories are supposed to teach us. In this case, this is life on this side of Resurrection. A woman will be healed while a father will grieve. This is why when the apostle Paul writes about how Christians are to live with one another he counsels, “Rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep.” Which is to say, in the community of faith there will be a simultaneity of people who have cause to praise God and people who have reason for lamentation.

Just the other Sunday—

As the body of Christ came forward to receive the body of Christ, I noticed:

Little Konnor Eddinger, who has been in occupational therapy, walked to the loaf and cup all by himself for the first time.

Behind Konnor, with her hands held out like a beggar and her bald head wrapped right in a scarf, was Patricia, who is still waiting for a miracle that will arrest her breast cancer.

Behind Patricia was Brad, dressed in the brown suit he wears on the days he guests on CNN; Brad has been cancer-free for three years.

Behind Brad was Mary, whose daughter— despite Mary’s entreaties— will not speak to her.

For every lonely woman Jesus names “Daughter,” there will be a Jairus and his lost child. There is always going to be a mix and a muddle of rejoicing and weeping. The scriptures say joy and lamentation just are the soundtrack of the church's life together. The Triune God raises us from the dead; he does not keep us from dying. In Christ, God becomes human not so we don’t have to be human. The promise of the gospel is not that Jesus excludes us from suffering. The promise of the gospel is that Jesus includes himself in our suffering. He places himself deep in the flesh. So deep in fact, your neighbor is now no less Mary’s boy than the bread on the table.

The truth is, we are all just barely living from one supper to the next.

So come to the table.

But before you do, discern the body of Jesus and know.

Whatever you’re going through, you’re not alone.

This is the key to our Story.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 23, 2025

The Church We Carry

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here’s a conversation with my friend Will Willimon about his brand new book.

About The Church We Carry:

Breaking faith, finding grace: wisdom for leading divided churches in divisive times.

Trusted and respected leader Will Willimon explores how failures in leadership and theological vision contributed to our current denominational crisis. Through the lens of a South Carolina historic congregation, this book offers a critical analysis that will enlighten today’s congregational leaders on navigating the complexities of ministry in our uncertain future.

As a retired Methodist bishop and expert in ordained leadership, Willimon reflects on a simple-to-ask-but-complicated-to-answer question: What has become of the church that shaped his faith? Focusing on Buncombe Street United Methodist Church, he examines their journey through disaffiliation to shed light on leadership challenges within our denomination, including his own role.

This insightful resource provides a candid exploration of the realities of ministry today, inviting us to confront our grief and shortcomings while embracing our duty to serve Christ’s church in the present moment. Gain valuable insights from real-life experiences, learn from those labeled as “schismatic,” and discover practical strategies for effective leadership in today’s evolving church landscape.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 22, 2025

"Now to him who is thrown out of the Temple comes the Lord of the Temple."

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

My friend and mentor Fleming Rutledge is a subscriber to this modest endeavor. As I preach through the miracles of Jesus, I would be remiss if I did not bring to your attention a wonderful sermon she preached at Asbury Seminary on Christ healing the man born blind in the Gospel of John. So far as I know, this sermon is not included in any of her collections. It is too strong a word to remain hidden in the deep recesses of the internet.

I love that she dared to preach on the entire chapter of John 9.

Speaking of Fleming, be on the lookout here for more information about the effort our little band of friends of Fleming are making to fund a chair in biblical theology in her name at Wycliffe College in Toronto.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 21, 2025

God Deep in the Flesh

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

This Sunday I will continue a long lectio continua series through the miracles of Jesus by preaching on the Gospel of Mark’s account of the unnamed woman with the twelve year old hemorrhage.

She is healed simply by touching the hem of Christ’s clothes.

As Matthew Thiessen puts it bluntly, the woman is healed by “Jesus’ uncontrollable discharge of power.”

The New Testament scholar Frederick Dale Bruner characterizes her faith as “naive” and her reach as “superstitious.” I think he fails to take seriously the divine humanity of Jesus.

As the church father Cyril of Alexandria writes:

“So Christ gave his own body for the life of all, and makes it the channel through which life flows once more into us. “

Mark tells us that in the press of the crowd, a woman slipped through, reached out her hand, and covertly touched the hem of Jesus’ cloak. She had been bleeding for twelve years. Twelve years of pain. Twelve years of isolation. Twelve years of being ritually unclean.

Twelve years without anyone touching her.

She had tried every physician, such as they were in the ancient world. Having been taken for all her money, she had find no relief. Until she touched the fabric of the clothes of the God made flesh. Mark says, “Immediately the bleeding stopped.”

Immediately.

Power went out from him.

And her body was made whole.

Simply by brushing up against the one who is God deep in the flesh.

The theologian Robert Jenson writes that the church’s Christology is an “assault” on the pagan ways of imagining God. What he meant is that if we want to know God, we don’t look first to philosophy or to abstractions about divinity. We look at Jesus. At his story, his body, his flesh.

This is precisely what the Gospel of Mark shows us. God is not a distant Being immune to time. God is in Jesus. God is in the crowd, sweating in the sun, pressed in by hands, tugged at by the desperate.

God is at the edge these garments. God is vulnerable to a crowd’s press and a woman’s touch. This is the church’s Christology.August 20, 2025

Christ’s Humanity is Divinity

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Here is the recording from Monday’s discussion of Bonhoeffer’s “Lectures on Christology,” particularly his look at the ancient heresies.

We will resume this coming Monday, starting with page 346 of the reading:

Bonhoeffer Reading 31.33MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 18, 2025

A Preacher's Words Propel God's History Forward

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

We will continue our Monday Night Live discussion of Bonhoeffer’s “Lectures on Christology” at 7:00 EST.

Here is the link.

Here is the reading:

Bonhoeffer Reading 31.33MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadThe Old Testament lectionary passage for this coming Sunday is the prophet’s call story in Jeremiah 1.4-10:

Now the word of the LORD came to me saying, "Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, and before you were born I consecrated you; I appointed you a prophet to the nations." Then I said, "Ah, Lord GOD! Truly I do not know how to speak, for I am only a boy." But the LORD said to me, "Do not say, 'I am only a boy,' for you shall go to all to whom I send you, and you shall speak whatever I command you. Do not be afraid of them, for I am with you to deliver you, says the LORD." Then the LORD put out his hand and touched my mouth, and the LORD said to me, "Now I have put my words in your mouth. See, today I appoint you over nations and over kingdoms, to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant."

Notice the careful, causal sequence in the final verses. The words which the LORD lays upon the prophet’s lips are themselves the active agents of the string of verbs at the end of the passage.

As Robert Jenson writes:

“The Word of prophecy does not so much predict events as create them.”The proclaimed word of the LORD, uttered in modes of prophecy or promise, is nothing less than the very enactment of God’s will in history. It is little wonder then that Jeremiah becomes known as the Weeping Prophet. The world resists the will of the LORD. Not for nothing does the church describe such speech in the language of labor pains— delivery.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers