Jason Micheli's Blog, page 9

June 2, 2025

The Breath of the Risen Christ

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

This Sunday is Pentecost.

Pentecost marks neither the birthday of the church nor the arrival of a heretofore absent person of the Trinity. As Robert Jenson argues, the whole doctrine of the Holy Spirit is problematic for the notion of the “spirit” is very often a way for Christians to revert back to religion unreformed by the gospel. The spirit celebrated at Pentecost is seldom the triune identity but rather an “indistinct and undemanding God.” Ubiquitous appeals to the Spirit as the breath or wind of the LORD are just such an example of drift away from the God of the gospel and back to barren deities we can fashion in our own image.

Published over forty years ago, Robert Jenson’s edited two volume survey Christian Dogmatics is a neglected gem of a resource for preachers. Jens’ second offering in the collection on the Holy Spirit is itself worth the price of both books. He begins his essay by noting the importance of the genitive case in speaking of the Holy Spirit. In other words, there is no kind of being called spirit: “There is no spirit-reality as a kind of thing; spirit is always of some individual or individual group.”

In the case of the Spirit called holy there is only the particular Spirit of Jesus and the one he addresses as Father. Because the Holy Spirit is spirit of the Son and his Father, the Spirit is not third in the order of importance, but third in the order of “God’s dramatic self-givenness.” The Holy Spirit is the one through whom the triune God communicates and completes his life in and with the world. “The Spirit,” Jenson writes, “is the enabling freedom of the triune life, God’s own future as opened for others.”

The Holy Spirit has the power of God’s own future bears decisive implications. Very often preachers proclaim the third person of the Trinity as the presence of the absent second person of the Trinity. Nothing could be further from the biblical truth. The Spirit is how God comes to us and stays with us—not from a distance— from within the risen Jesus.

Pentecost is not the arrival of an alternative to the vanished Jesus.

Pentecost is the revelation of the person who makes God’s identity communicable— who words the colloquy that is Father and Son to us.

As Jens writes:

“The Spirit is God as he opens himself; the Spirit is God’s own life as it goes beyond itself to include others.”

Just so, the Spirit that spoke by the prophets is not especially identifiable with mystical intuition or religious experience but with the speech and presence of Christ—God’s Word carried forward in time. This is why, for example, in Romans 8 Paul pairs “flesh” and the law of sin and death” as antonyms of Spirit such that everything Paul says of the Holy Spirit can likewise be said of the gospel.

As God’s Word carried forward in time, the identity of the Holy Spirit is the Spirit of the resurrected, reigning Jesus.

The identity of the Holy Spirit is the Spirit of the resurrected, reigning Jesus.

May 30, 2025

Jesus Saves (Present Tense)

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Eastertide closes this week with Luke’s account of Jesus ascending bodily into heaven.

To do what?

The church father Gregory of Nazianzus preached, “Even at this moment, as a human being, Jesus is making intercession for my salvation, for he continues to wear the body that he assumed.”

Despite what Christ declares from his cross, it is not finished.

His work is not done.

His work is perpetual.

May 28, 2025

The Ascension is Not about a Where; It’s about a When

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Eastertide closes this week with the Risen Lord’s ascension. The lectionary includes Luke’s account in Acts 1 for the feast day:

In the first book, Theophilus, I wrote about all that Jesus did and taught from the beginning until the day when he was taken up to heaven, after giving instructions through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen. After his suffering he presented himself alive to them by many convincing proofs, appearing to them during forty days and speaking about the kingdom of God. While staying with them, he ordered them not to leave Jerusalem, but to wait there for the promise of the Father. "This," he said, "is what you have heard from me; for John baptized with water, but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit not many days from now." So when they had come together, they asked him, "Lord, is this the time when you will restore the kingdom to Israel?" He replied, "It is not for you to know the times or periods that the Father has set by his own authority. But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth."

When he had said this, as they were watching, he was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight. While he was going and they were gazing up toward heaven, suddenly two men in white robes stood by them. They said, "Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven? This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven."

Perhaps no other event on the liturgical calendar challenges what we know of the world more so than Ascension.

How are we to speak intelligibly of such an event, knowing, as we do, that heaven is not “up there?”I know not how Jesus departed, but I do know that he did not go up, up, up, and away.In some ways, Christ’s ascension is an item of dogma on the slimmest of basis. Only Luke mentions it and he does so twice. Read in isolation, Luke’s account of the ascension could create the impression that Jesus has spent the last forty days since his resurrection on terra firma but this is straightforwardly not the case. Luke tells us that on the third day after his crucifixion, the Risen Jesus encountered two disciples who were on their way home in Emmaus. Strangely, Cleopas and the other unnamed disciple do not recognize their traveling companion until “he took bread, blessed and broke it, and gave it to them. Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him…” Coincident with the instant of their recognition, Luke reports, the Risen Christ “vanished from their sight.”

Luke does not say, “Jesus walked off into the distance.”No, it’s, “He vanished from their sight.”Later that night, the disciples are hiding behind locked doors when at once the risen Jesus is standing among them. Jesus does not knock on the door. Jesus does not step through the door. Jesus is simply and suddenly standing amongst them.

Whence did he come?If the risen Jesus ascends forty days after Easter, then where was he in between his appearances and how does that influence our understanding of the ascension?

The Gospels make it clear. Between his Easter appearances, the Risen body of Jesus had no location in this world. The Risen Jesus did not rent a room at the Super 8 in Jerusalem. He was not glamping in Galilee. He did not couch-surf in Samaria.

He appeared. And then he vanished from their sight.

Whatever else the ascension means, therefore, it does not signal a change in Jesus’s spatial location.The risen Jesus was not exclusively located on earth during the forty days after his resurrection just as the ascended Jesus is assuredly not now located “up there.” Where was the risen Jesus in between his Easter appearances? Where is he now if the ascension does not narrate his journey from one place in the cosmos to another place in the cosmos?

May 27, 2025

“Preaching ought to give you the Word in such a way that God comes to you with something bigger than mere information.”

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Here is a sermon on Sunday’s texts by my friend Ken Sundet Jones. Don’t forget to apply for the next cohort of the Iowa Preachers Project with us.

Sixth Sunday of Easter — Luther Memorial Church

Grace to you and peace, my friends, from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. Amen

In our first reading today, the apostle Paul and his companion Silas leave what’s now southern Turkey and sail north to the top of the Aegean Sea to the city of Philippi. These two missionaries to the Gentiles are carrying letters from the leaders of the church in Jerusalem who had met to decide if Paul was allowed to go out and preach to people who weren’t Jewish and didn’t follow Jewish religious laws and traditions. The letters granted permission and said pagan converts weren’t required to submit to circumcision.

But they also asked them to not engage in pagan practices or live immorally.

Most important, though, is that the letters allowed Paul to follow his nose, or in this case follow a dream he’d had of someone beseeching him to come up to Macedonia. The permission in those letters winds up being a reason we have all those NewTestament letters to believers in Thessalonians, Ephesus, Corinth, and Philippi. And that permission is also behind a Gentile baby named Sonya on the other side of the planet two thousand years later being baptized.

Later in Paul’s life, after he’d been arrested and jailed in Caesarea, Paul would write to the Philippians from prison to strengthen the new believers’ faith. Today’s reading shows him meeting Lydia, his first Philippian, who was really an immigrant from Thyatira. Acts tells us a few other interesting details about Lydia. The first is that she’s a “worshiper of God.“

When Paul came to a new location to bring the good news of our crucified and risen Lord, he’d encounter three groups of people. First there were people who worshiped pagan gods who had little interest in what he had to say. At the other end of the spectrum were those who were strict adherents to Jewish religious practices and laws who rejected Paul’s assertions about Jesus (and sometimes reported him to authorities as a disturber of the peace).

The third group were the proselytes, the worshipers of God — as Acts calls Lydia — who were divine-curious. Someone like Lydia, a foreign woman from Thyatira, would come to the Jewish synagogue to hear the reading of scriptures translated fromHebrew to Greek, to sing the psalms, to listen to preaching, and to pray. So we know that Lydia and the other women at the very least were open to matters of faith. Paul’s words to them would have had a familiar ring to them, and they would have been more open to what he told the, about Jesus.

Acts also tells us two other little details: one, that the women were at the river and, two, that Lydia was a purpler. The second detail was the reason for the first. The women were likely Lydia’s workers in the process of dying cloth purple, and the river was their water source.

Way back when we took our first group of confirmation students to the Luther sites in Germany, we visited the workshop of the woman who was Germany’s last master indigo dyer. She used urine to extract indigo dye from a native plant called woad, and we got to help her dye some cloth, but thankfully we weren’t asked to contribute urine. While indigo is a dark navy blue and comes from a plant, Lydia’s dye was purple and came from a rare sea snail called the spiny murex. It involved cutting out the little dye sacs from 100 pounds of snails to make about a half teaspoon of purple dye. That dye was so expensive that the law of the Roman Empire only allowed the nobility and the wealthy to wear purple.So far all this makes good material for a Bible study downstairs in the education rooms before worship, but it doesn’t make for much of a sermon.

The relationship between scripture and preaching needs to be more than just imparting historical facts or theological ideas. Preaching ought to give you the Word in such a way that God comes to you with something bigger than mere information.And the way to do that with Paul and Lydia and the river and purpling is to keep in mind who doesn’t have access to what God seeks to give. The vast majority of people in Philippi probably wouldn’t see purple cloth. They certainly wouldn’t be able to afford it. So going to the river for fabric for your clothes was so beyond the reach of any of us that was illegal. And even Lydia, in spite of being incredibly wealthy because of her business, had no access to the benefits of faith granted to the Jews in the synagogue. She could be uber-interested in God and sing the psalms and pray the prayers. But she wouldn’t be allowed to be a full part of that life.

Her money was no good in the God store. The contrast between what her wealth availed her in the world and the limits she encountered up the hill from the riverbed at the synagogue was an eternal chasm. And it makes Lydia and her household ripe for the Holy Spirit’s picking.It’s not too big a leap to that exclusion along the river and in the synagogue in Philippi from a pool of water at Bethesda outside Jerusalem a thousand miles away and decades earlier where a man had been ill for thirty years and had been excluded from every aspect of life. The pool was said to roil on occasion on account of angels stirring the waters, and whoever got to the waters first would be healed. But our guy faced the impediment of not being able to move himself. If Lydia, with all her advantages couldn’t make herself what was right and salutary for God, this man was in worse shape. Forget about religious issues. He couldn’t even move off his mat to get a few feet to the pool. The barriers were too great.

Acts also tells us the story of Philip’s encounter with the Ethiopian eunuch who, like Lydia, was a pagan God-worshiper. He’d been barred from worshiping in the temple in Jerusalem because he’d been castrated as a boy to make him safe to serve in his queen’s treasury. When Philip told him about Jesus and his benefits, the eunuch pointed to some water and asked he was also banned from baptism.

“What is to prevent me from being baptized?” he asks. The answer: not a single thing.Jesus at Bethesda never asks about the man’s qualifications or his worthiness. The guy at the pool tries to explain, but it’s like Jesus rolls his eyes and thinks “Here we go again with the folderol about meriting what I have to give. I’m not interested in anything but two requirements: your need and my mercy.” And with that divine intent, the man is healed. Jesus just hits ‘er done, and the fella doesn’t even realize it yet, because Jesus has to tell him to stand up and collect his kit and head home.

Up in Philippi, the letters Paul has in his apostolic messenger bag do the same thing for Lydia that Jesus did at Bethesda. They create a situation where the excluding boundaries are treated as irrelevant. Lydia and her whole household are baptized, which presumably means spouse and children, and both free and enslaved servants. Her supper invitation to Paul and Silas is how a wealthy purpler picks up the mat of her life and starts walking.

Both stories are perfect for this day when Emily and Zach bring Sonya to the font to be baptized. Not only is she the fifth generation, like her sister, to be baptized in that baptismal gown, Sonya also is carried here as the latest in 2000 years and countless generations of undeserving, unremarkable, and unrighteous sinners to encounter our Lord in the waters ofbaptism. And today he will give her what he gave Lydia and her household and what he gave the man in Bethesda: access not exclusion, mercy rather than judgment, and life over against death.

Paul met Lydia with letters in hand, but today Jesus gives Sonya traveling papers for her journey, just like the name of our ship, “Hjemad” — homeward. For as good and faithful the well-intentioned promises from Zach and Emily and from Sonya’s sponsors are, there’s only one promise that counts, one declaration, one Word. It comes in these words that God only uses a pastor as a mouthpiece for: “I baptize you.”

This eternal promise is made to a baby who’s as unaware as she is undeserving. All the better to contrast with Jesus’ utter graciousness.

There’s no purple robe here made from outrageously expensive fabric that none of us could afford. Instead there’s a different robe that Sonya’s baptismal gown represents. It’s the same thing as a pastor’s alb and the funeral pall that will one day drape her coffin.

In John’s vision in the book of Revelation, he sees the heavenly host arrayed in white. I suspect some of them had worn purple in life and others had been clothed in rough spun sackcloth. But nowJohn is told their old robes had been washed in the blood of the Lamb and come out looking like Jesus at the Transfiguration. And that’s the most expensive fabric of all, because it cost Jesus his life. [change from purple stole to white]

Today the letters written in God’s Book of Life record Sonya as part of that host in white not purple. And the promise of our second reading is that she — and you, my friends and fellow sinners — when all things are brought to completion will be found at the river of life flowing through the City of God. Already today, you’re included. The robe is yours. The place is reserved. For when God chooses, when God says “You!” it happens right then and there. And we’ll all be reminded again that we shall gather at the great river that the little bowl of water in this font flows from.

Amen.

And now may the piece, which far surpasses a baby’s understanding and ours, keep our hearts and minds in Christ Jesus from whom flows Living Water. Amen.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 25, 2025

To Live by Faith is to Live by Sight

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Ruth 4.13-22

Just after Jesus issues the promise that his yoke is easy and his burden is light, he journeys through the grainfields outside Capernaum. And his disciples are hungry. So as they follow Jesus, they pluck the heads of the wheat and roll the grain in their hands, freeing the kernel inside. Thus did the disciples of Jesus eat on the Sabbath. Ever since the scandal he caused by eating and drinking with sinners, a paparazzi of Pharisees have hounded after Jesus, hoping to catch him in the latest outrage. When they witness his disciples eating from the fields on the Sabbath, they pounce, “Look, your disciples are doing what is not lawful to do on the Sabbath.”

Jesus responds by chastising the Pharisees for condemning the guiltless before he finally declares himself to be the LORD of the Sabbath. In other words, “You want to quote the commandments at me? This is the finger that etched them in stone for Moses.”

“Is it lawful to do this on the Sabbath?!”

Of course— they should know it— the answer to their question is, “Yes!” It is lawful to do such things on the Sabbath. It does not violate the commandments for his disciples to pluck the heads of wheat in the fields, roll them in their hands, and eat the released kernel. The Sabbath commandment forbids the use of tools to harvest grain not their hands. As the LORD Jesus commanded Moses in the Book of Deuteronomy, “When you enter your neighbor's standing grain, you may pluck the ears with your hand, but you shall not put a sickle to your neighbor's standing grain.”

“Is it lawful to do this on the Sabbath?!”

Yes!

Yes it is.

Yes it is in keeping with the commandments.

They are wrong. And obviously it is not that they do not know their scriptures, it’s that they have read them badly. And because they have read their Bible badly, they are blind to what God is doing in Jesus Christ in their very midst.

We are no less guilty of being bad readers.

In the Gospel of Luke:

Just after he spins his parable about the marriage supper of the lamb, Jesus announces to the great crowds that have gathered around him, “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his own father and mother, his own wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple.” I don’t know how many literal, uncompromising, un-Christlike sermons preached by aspiring radicals I have heard on this passage. Even the editors of my Bible give it the header, “The Cost of Discipleship.” In interpreting this passage, seldom do we stop to take note of the fact that the disciple standing next to Jesus when he issues this bewildering announcement, the disciple upon whom Jesus intends to build his church, is Peter. And only a few chapters before this passage, Jesus healed the mother of Peter’s wife.

Peter appealed to Jesus to heal his wife’s mother.

If Jesus was truly saying that we must choose him over our loved ones, then Jesus would not have chosen Peter to found his church, for Peter did not leave his family in order to follow Jesus.

Again and again, we misread the scriptures.

When my cancer came back this winter, a clergy colleague, whom I only know online, sent me a Get Well card. In it, in large cursive loops, he had scrawled a verse from the Book of Jeremiah. You probably know it; it may be the only verse you know from the prophet: “For I know the plans I have for you, declares the LORD, plans for welfare and not for travail, to give you a future and a hope.”

It sounds comforting if you do not know the Book of Jeremiah.

The happy plans God promises to Jeremiah do not apply to Jeremiah. In fact, they exclude Jeremiah. Accordingly, the other happy-sounding verse you may know from Jeremiah is likewise unsettling. God singles Jeremiah out for from before his birth (“Before I formed you in the womb I knew you.”); in order, to announce good news to people that he himself will not receive.

Jeremiah is not a beneficiary of the LORD’s plans for prosperity and hope.

Jeremiah dies— doomed— in Egypt.

“Thanks so much for your thoughtful card,” I emailed the preacher back.

Over and again, we rush over the scriptures or we cherry pick them for our own predetermined purposes; so that, we end up knowing them no better than those who hounded after Jesus.

We read the parable of prodigal son, for instance, as a happy story of amazing grace rather than a haunting tale of a son who is content to celebrate without his older brother.

———————

No less than the Pharisees in the fields, we badly misread the scriptures.

Just so, we do not see what God is doing in our midst.

———————

Take another example.

We think Ruth is a story about the woman whose name the book bears.

But if so—

If Ruth is the main character of the Book of Ruth, then why does she vanish from its ending?

The story has perfect narrative symmetry. It moves seamlessly from famine to fullness. It began with empty bellies and barren wombs; it concludes with feasting and nativity. The story started with three deaths: the husbands of Orpah, Ruth, and Naomi. The story concludes with three births: Obed, Jesse, and David. The book begins with Elimelech dying in a foreign land. The book ends with the redemption of his name and the resurrection of his inheritance.

The story has perfect symmetry.

Except for one flaw.

The “main character” disappears fully from the finale.

Right at the moment she gives birth to her baby, Ruth vanishes. Not another word is uttered about her. No sooner has her baby crowned than the women of Bethlehem proclaim, “Blessed be the LORD.” They proclaim the blessing not to Ruth but to Naomi.” Then immediately the women place the newborn not in Ruth’s arms but in Naomi’s lap. And finally those same women of Bethlehem give the baby a name, Obed. His name means, “worshipper.” They name him Obed because— pay attention— “a son has been born to Naomi.”

A son has been born to Naomi.

Ruth’s disappearance from the Book of Ruth has been interpreted as a flaw in the story’s harmony and proportion. Feminist critics view Ruth’s vanishing from the story as worse than a narrative defect. Feminist critics interpret it as a sign of sin, evidence of an ancient patriarchal society that silences women, eliminates their agency, and sees them as nothing more than “cogs in the baby-making machine.” And to be sure, the Book of Ruth does end with a genealogy of male names.

But again, we are such bad readers of the scriptures!

A son has been born to Naomi.

This is not a blemish in the story. This is the story! Ruth does not disappear from the Book of Ruth. Ruth recedes from Naomi’s story.

A son has been born to Naomi.

Not—

A son has been born to Mara, the name she gives to herself after her husband and sons have died because— she says— “The LORD has dealt bitterly with me.”

“A son,” the women exclaim, “has been born to Naomi.”

This is part of the story’s perfect symmetry not an exception to it.

After all, two questions drive the plot of Ruth, two questions posited at the very beginning of the book, one question posed by Naomi and another question asked of Naomi.

The Book of Ruth is but the answer to those two questions.

Remember.

At the start of the story, when the widows of Naomi’s sons attempt to accompany their mother-in-law back to Bethlehem, Naomi— who’s convinced the judgment of the LORD is against her— says to Ruth and Orpah, “Turn back, my daughters; why will you go with me? Have I yet sons in my womb?”

That’s a pregnant question to ask.

Even a bad reader of the Bible knows that the Living God— the God who rescued Israel from slavery and raised Jesus from the dead— specializes in occupied tombs and barren wombs.

“Go back,” Naomi implores them, “Will I have yet more sons?”

Later, when they first arrive in Bethlehem, the women of Bethlehem (the same women who will lay Ruth’s baby in Naomi’s lap) look at Naomi— famished and bitter, grieving and barren of all hope— and they ask, “Is this Naomi?” That is, “Naomi, you are no longer who we knew you to be.” Which is to say, “Can the woman who now calls herself Mara (Bitterness) be made Naomi again?”

Ruth is a stranger to Israel and a mother to Israel, yes, but Naomi is Israel. She struggles with God and she prevails, “A son has been born to Naomi.”

The question asked by Naomi and posed to Naomi at the beginning of the story are the questions at the heart of biblical faith:

“Is anything too wonderful for the LORD?”

“Is anything impossible for God?"

“Is love stronger than death?”

“Can these bones live?”

“Have I yet sons in my womb?”

“Can Mara be made Naomi again?”

“Can Bitterness be turned back to Sweetness?”

Ruth is not the main character of the Book of Ruth. Naomi is. Ruth is but one of the means by which the LORD answers those two questions— which are really one question— posed at the beginning of the book. In other words, (despite what you may have heard from bad readers of the Bible) the Book of Ruth is about God.

———————

One morning, years ago, I sat in the surgical waiting room in Charlottesville at the University of Virginia hospital, waiting with David’s wife. Ashley was blond and pretty and sweet. She was the kind of person to whom it had never occurred to tell even a white lie. Ashely’s face was tanned from all the camping they had tried to squeeze into their schedule while there was still time. A silver cross hung around Ashley’s neck; it was a bigger version of the ones she’d given to their son and daughter when they’d started to serve as acolytes.

Ashley’s husband, David, was only a few years older than me. He’d lived every day of his life in the same small town and wouldn’t have had it any other way. He had been baptized and raised and was now raising his own two kids in the church I pastored. Ever since graduating from high school, David had worked in the local carpet factory and had served as the captain of the volunteer fire department. When I first met him, he hadn’t worked in a year, not since ALS had begun its monotonous mutiny against his body. Shortly after I had arrived as the new preacher, David had driven me in his battered, red F150 all over the hills he had hunted and hiked. He wanted to get to know me better, he said, because he thought I’d likely be doing his funeral.

Too soon after David had driven me through the Blue Ridge, I drove them over those same mountains to the hospital; so that, David could have a feeding tube installed into his body. I sat next to Ashley in the waiting room. I listened as she mulled over how she had explained this latest step to their kids and anguished over whether she had done it wrong. I watched as she leafed again through the folder filled with instructions and warnings a nurse had handed her. I handed her a tissue when I saw that she was about to cry.

Again.

Through sniffles and with tears, she confessed to me her worries and fears and exhaustion. She told me she was terrified what David’s long, slow death would do to their children.

“It’s like they’re watching him be tortured to death,” she whispered.

And then she hung her head.

And she started to cry.

Again.

When she stopped, she looked up at me with fierce curiosity in her eyes.

“Will I ever be happy again?”

———————

In his book Four Hundred Texts on Love, the church father Maximus the Confessor writes:

“God ordained that nothing be more conducive for our becoming God—if I may speak thus—than mercy given from the heart with pleasure and joy to those in need. For the Word has shown that the one who is in need of having good done to him is God; but also, the one who can do good and who does it is truly God by grace. And if the poor man is God, it is because of God’s condescension in becoming poor for us. All the more reason, then, will that one be God who by loving human beings in imitation of God heals by himself in a God-fitting way the sufferings of those who suffer and who shows that he has in his disposition, in due proportion, the same power of sustaining providence that God has.”

To put it plain:

We are the providence of God.

You are how God does God to others.

The LORD answers your prayers, he addresses your empty places, he responds to your barren hopes, in no other way but the people around you.

You are how God does God to your neighbor.

Your neighbor is how God does God to you.

We are the providence of God.

———————

When we read the Book of Ruth like the Pharisees in the fields read the Torah, that is, when we read it lazily or hastily; or, when we treat the Book of Ruth merely as an account about Christ’s genealogy rather than Jesus’s Word to us, then it becomes easy to think that God is not an actor within the story. If we take Ruth to be the main character of Ruth, then the LORD appears to have no role or voice in the narrative. After all, nowhere in the Book of Ruth do we read the words, “And God said to Ruth.” God appears on the lips of Naomi and Boaz, but he does not appear to them. There is no heavenly host in this Bethlehem. God is not listed in the story’s dramatis personnae.

But when you notice that the Book of Ruth is actually about Naomi— or, better yet, the book is the answer to those two questions asked at its beginning— then you can see that over and over again in the book, the characters in the story ask God to do something that they themselves end up doing.

Ruth prays that Naomi’s people would become her people and Naomi’s God her God. But then it is Ruth, in what St. Ephrem the Syrian calls “erotic audacity,” who takes matters into her own hands and makes Naomi’s people her people and, thus, their God her God. Again and again, the characters ask God to do something they end up doing. Naomi prays that God would be to Ruth as Ruth as been to Naomi, but as soon as they arrive in Bethlehem, Naomi plays that role to Ruth, plotting for her to find a redeemer. Boaz prays that Ruth would find shelter in the shadow of God’s wing, but by the end of the story Ruth has found protection under the shadow of Boaz’s wing.

Boaz turns out to be how God answers Boaz’s prayer.

He is the providence of God.

———————

“Have I yet sons in my womb?”

Yes!

This is the God who specializes in tombs and wombs.

“A son has been born to Naomi.”

It is not that God is absent in the story. It is that God fills the entire story with his own life. God is fully embodied in the characters of this story. Their movements are God’s movements. Ruth and Boaz, the women of Bethlehem and the reapers in the fields— for Naomi’s sake, they are the providence of God.

God’s providence is not something behind the story. It is the story. It is not invisible. It is incarnated in the lives of the people of Bethlehem. God doesn’t fix Naomi’s loss by snapping his fingers from his seat in heaven. God doesn’t answer her bitter question by declaring, “Thus says the LORD.” No, God does it by Ruth walking the gleaning fields. God does it by the men and women of Bethlehem choosing grace over the commandments. God does it by Boaz obeying an obscure law in order to redeem Ruth; so that, through Ruth, Naomi is be made Naomi again, with a son on her lap.

It is not that God is not in the story. It is that God’s providence wears sandals. It gathers barley. It walks into town and bargains at the city gate. It carries sheaves back home. It welcomes a stranger. It even risks shame and seduces a rich man.

As Chris Green writes, “God is happy for his providence always to remain unsearchable.” Or as Simone Weill says, “The devil dazzles; God does not.” That is, God is so humble— because Jesus is God— that he joyfully hides in the ordinary lives entwined with yours. God’s work is deeper than your perception but it is as near to you as your neighbor.

———————

“Will I ever be happy again?” Ashley asked me, “Right now, it feels impossible.”

And then she covered her mouth, “Is that a horrible thing to wonder?”

I shook my head.

“There couldn’t be a more biblical question to ask.”

“Well, I just wish God would show up and tell me so already.”

“The faith isn’t magic,” I replied, “It’s mystery.”

She nodded but I could tell she didn’t follow.

“For God to allay all your fears and worries by appearing to you in all his Almightiness— to give you a sign— is to want him to be someone other than who he is. Like it or not, he prefers to show up as someone like me, assuring you that everything is going to be okay.”

She nodded.

And then she smiled, “You’d think God would show up as someone who’s a better driver than you.”

I looked at her, wanting to see the seriousness in my eyes.

“You can be happy again,” I said, “The Bible tells me so. I don’t know how God will do it. But I do have an idea through whom he will do it.”

———————

This is the word of the LORD to you.

You can be Naomi again.

If you think God has dealt bitterly with you, if you grieve the loss of more love than you dare count, if life has left you famished and exhausted, if your future feels as empty as your hopes are barren, if your present seems defined by what is absent, this is the word of the LORD to you.

You can be Naomi again.

Pat Sherfey— you can be Naomi again.

Pam Jones— you can be Naomi again.

Bob Kallal— you can be Naomi again.

Shirley Hanson, Mary Chambers, Jane Underhill, Kelly Watts…I could run through the church directory, A-Z, the promise stands because the Book of Ruth is not a story about the genealogy of Jesus.

It is a word from Jesus.

Let the bitter and broken-hearted believe!

You can be Naomi again.

Listen.

This is the word of the LORD to you.

God does not abandon the bitter.

He will make your life sweet again.

God does not forget the empty.

He will fill you— if not with what you want, then with himself.

God does not despise the grieving.

There is yet a future for you.

You will be happy again.

God gives sons again.

God gives names again.

God gives bodies back.

He gives hope.

Again.

But look around you.

It’s not magic. It's mystery. God does it in no other way but through the people around you. Right this very moment, you’re sitting next to and in front of and behind the providence of God— he is so humble, he’s hiding behind all of it.

To live by faith is to live by sight.

———————

But such vision does not come easy.

Again— the devil dazzles; God does not.

Fortunately, Jesus promises there is something even more blessed than to so see him. That is, to taste him. When Christ says to Thomas, “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe,” he’s pointing you to loaf and cup. So all of you who wonder if you can become Naomi again, come to the table.

Taste-and-see that the LORD is good.

He specializes in barren wombs and sealed tombs.

Come.

Be filled.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 23, 2025

Jesus Changes Everything

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Here is our most recent Monday Night Live discussion of the new collection of Stanley Hauerwas’ work, Jesus Changes Everything.

Seeing as how we discussed Stanley’s work on the Sermon on the Mount, here is a sermon delivered by him on Matthew 5 from 2017:

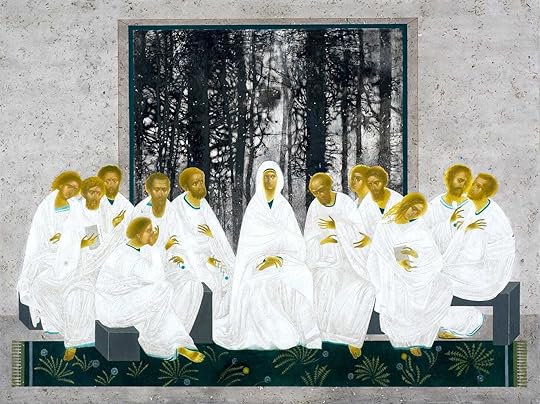

The image of the saints robed in white, surrounding the throne of the Lamb in the book of Revelation, is a powerful depiction of the significant place of the martyred saints in the Christian faith. Put as simply as I can, I think it true that if there were no martyrs there would be no Christianity. That the doors of many churches are painted red is to remind us that we are only able to be Christians by the sacrifice of the martyrs. That the martyrs play such an important role in our faith is a reminder that to be a Christian is to enter a way of life that trains us in how to die. It is not an empty gesture that in the baptismal liturgy we say “We thank you, Father, for the water of Baptism. In it we are buried with Christ in his death.”296 For the Christian, death is always a possibility given the presumption that as Christians we would die before we betrayed the one who has given us life. Thus Herbert McCabe’s observation that for Christians, “there is no casual death, there is only a choice between martyrdom and betrayal.” Martyrdom, so understood, is a reminder that the willingness of Christians through the centuries to be killed because of who they worshiped represents an intense form of the politics of Jesus. That politics—the politics of Jesus—means we never as Christians live in a time or place where martyrdom is not a continuing possibility. Training in how we should die is the heart of every politics, just to the extent politics is always about that for which it is worth dying. That for which it is worth dying means some draw the conclusion that you must also be willing to kill to sustain that which is so valuable. We, that is we Americans, are quite good at hiding the significance of death for our politics. We tell ourselves that politics is fundamentally about the satisfaction of interests, but it nonetheless remains the case that politics even in liberal societies is but another name for the distribution of risks that are intrinsic to an economy of death. The political character of martyrdom was strikingly evident in the struggle between Christians and Rome. It took some time for the Romans to even notice that a small band of people called Christians existed. From a Roman perspective the Christians did not seem to be a threat so there was little reason to kill them. Pliny thought they were but another burial society. He was not wrong about that, but he did not have a clue about the significance of how the way Christians died raised questions about the pride that was at the heart of the project called Rome. The Romans were not completely without insight about these matters. It did not take them long to understand that the Christians were anything but just another religious association. The Christians worshiped Jesus. They thought it was only in that name that you could live a life that you might lose early. Accordingly, Christians called into question the Roman worship of the gods that legitimated the decisions Rome made about who should be killed and who should be tolerated. The Christians, therefore, had a story about the way things are that was fundamentally at odds with the stories on which Rome depended. As a result, Christians refused to be tolerant because they were anything but ambivalent about who had made their lives free. Confronted by such a people there is only one thing you can do if you are Rome. You must kill them and in the process show that their willingness to die makes clear that the narrative that shapes their deaths cannot be true. Yet there was an unpleasant discovery that awaited Rome. Rome discovered that they could kill the Christians, but they could not determine the meaning of their death. Rome would even put those who were to die through degrading forms of torture in the hope of making their deaths meaningless. But the Christian refusal to let Rome determine the meaning of the death of martyrs made clear that the church was an alternative politics to the violent politics of glory that made Rome Rome. The citizens of Rome desperately fought to insure Rome was eternal, so no memory would be lost. If Rome fell, who would remember them? Christians had a quite different polity because they knew God would remember. The white-robed army that surrounds the throne makes the church here and now actual. They have been identified as those who have been made who they are by the blood of the Lamb. They have been told by God who they are. They are not “heroes” or “heroines.” They are martyrs. They are witnesses to the inauguration of a new time by a man named Jesus. He has defeated the violence of a politics that tries to sustain itself by killing those who threaten the presumption that it is eternal. These reflections on martyrdom as a politics may seem quite foreign for American Christians. We do not think of ourselves as living in a country in which our lives as Christians are threatened because we are Christians. So we do not think of ourselves as a church of the martyrs. Yet we do have this prayer in The Book of Common Prayer: “Almighty God, who gave to your servant N. a boldness to confess the Name of our Savior Jesus Christ before the rulers of this world, and courage to die for the faith: Grant that we may always be ready to give a reason for the hope that is in us, and to suffer gladly for the sake of our Lord Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.” We are a people who celebrate and thus remember the martyrs. Let us not forget that this is dangerous business, but let us not fail to remember that those who have triumphed—that is, those called martyrs—have made us members in a fellowship inaugurated by Jesus, so that the world may know a people exist who are willing to die, yet who refuse to kill. To be part of such a people is what it means to be saved.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 22, 2025

The Logos Does Not Wait for Permission

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

John 5.1-9

For the Sixth Sunday of Easter the lectionary provides an additional, optional passage from the Gospel of John. You would think that if the lectionary had room for one more reading then the powers-that-be could supply a text from the Old Testament but that’s a rant for another day.

In John 5, Jesus and the disciples have returned to Jerusalem for a festival. Near one of the city’s many ancient gates, the Sheep Gate, Jesus approaches a pool at Bethsaida. I’ve been there. The place would’ve been congested, chaotic, and confused with that ill summoned there. John reports the healing waters of the pool have attracted “many ill, blind, lame, and paralyzed people,” including “one man was there who had been ill for thirty-eight years.” Note: John does not specify what ails this ill man.

Jesus— God and Man— intuits this suffering fellow has been there for a long time.

So knowing, Jesus proceeds to practice an odd medicine on the man. Mary’s boy does not reach down and touch him as he does the man with the withered hand in the Gospel of Mark. He does not, like the Samaritan for the man in the ditch, stoop down, pick him up, and carry him to his salvation. Jesus simply asks him a question— a rude question we might think unbecoming for Jesus to pose.

“Do you want to be made well?”

The question sounds like a provocation. Jesus queries not after his ailment but his desire.“Do you desire to be made well?”

Maximus the Confessor interprets this passage not as a question of the ill man’s willpower or his psychological readiness— Jesus is neither a physical therapist nor a social worker. The question Jesus proffers, Maximus insists, is a metaphysical invitation. For Maximus (and, for that matter, for John Wesley) Jesus does not merely heal the body. He reorders the cosmos. He “innovates” creation by joining it irrevocably to himself.

In the Ambigua to John, Maximus writes:

“The Word of God (that is, Jesus) willed to effect the mystery of his Incarnation not only once, but always and in all things.”

For the church fathers, the passage provides a clear illustration of the human situation apart from the Word’s work. The man at the pool is not simply sick. That John tells us he has laid there for nearly four decades is a clue. He is dis-integrated; that is, he is alienated from the End— the telos— of his existence.

May 21, 2025

Christ Calls Proclaimers Not Explainers

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Next month, I am offering a talk on preaching for an event celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Fleming Rutledge’s ordination. HERE are the details if you’d like to join us. To prepare, I have revisited some of the talks I delivered for the priests of the Anglican Church of Canada three years ago.

Below is the transcript of my first talk on the given topic, Grace and Healing.

You can listen to the audio delivery here.

Tamed Cynic Hitmen and Midwives Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work… Listen now3 years ago · 8 likes · 2 comments · Jason Micheli

Tamed Cynic Hitmen and Midwives Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work… Listen now3 years ago · 8 likes · 2 comments · Jason MicheliGracious and merciful Father, we pray for the one who speaks and for all of us here who speak. Sunday to Sunday for you know that we are imperfect and that our sins are many. In your Son's name we pray…

It was homecoming morning in Charlottesville, Virginia in 1999. A month into the fall semester of my fourth year at the University of Virginia, I had planned to skip the football game and I was holed up at an empty carol back in the stacks of old Alderman Library. I had a Bible on my desk for a class I was taking on the Gospel of John. had a couple of LSAT prep books I'd already started to dig dog ear and underline. At the library carrel on the other side of the bookcase was a tall, skinny African American man wearing large headphones and an orange Navy tracksuit. He was busy highlighting a biochemistry textbook and taking notes on colored index cards. I started working on some sample problems from the prep book when suddenly there was a guy leaning against the end of the bookcase with his feet crossed nonchalantly and a crinkly plastic-covered book in his hands.

“What are you working on?”

“Me? I'm studying for the LSAT,” I said.

He had a beard, a tan face, and dark hair that stuck out of a black knit hat on his head. He was wearing jeans that were ripped at the knees and a brown Henley shirt.

“You've got a lot of lawyers in your family already, don't you?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Wait, how did you…”

“Don't freak out, Jason," he said.

And he pulled out a different book, Anthropology, from the top shelf when he flipped through it.

“You like that other class a lot, though, don't you?” He said, pointing at the HarperCollins Study Bible.

“Yeah, yeah, I really do,” I said. “But I like the other classes, too. It's hard, you know? Knowing what God wants you to do with your life.”

“I just want you to enjoy your life,” he said.

I looked around for my roommates who surely must be punking me, I thought.

“Don't do anything just to satisfy someone else's expectations and don't go down any path just to measure up to what the world defines as success. That's what I freed you from,” he said.

Then he pointed at the Bible and he said, “if you'll have the most fun doing that, then that's what you should do.”

And he slid the book back in the empty space on the bookshelf. He held out his arm to fist bump me and he said, “relax, man. You're going to have a grand time. Preach it.”

“Hold up, I said. Trying to find my voice. I didn't catch your name.”

He'd already disappeared behind the old heavy fire door at the end of the long row of stacks. Now after a few moments, I turned to the pre-med student on the other end of the bookcase, speaking up so as to be heard over his headphones.

I said, “did you catch that guy's name?”

“Nobody been here boss but you and me.”

Not long after I started the ordination process in the United Methodist Church, I learned not to tell that story.

Church bureaucrats, ironically enough, were the quickest to think I was crazy. And then asked if I saw counseling.

I begin with that story for two reasons. the first place, what good am I as a Wesleyan if I'm not going to show a room full of Anglicans how to give their testimony?

But most importantly, I wanted to illustrate why I have no doubts whatsoever that Jesus Christ is not dead. And indeed our living Lord has a word for you.

Contrary to the false notions both in and out of the church, Jesus did not die in order for God to forgive you. Anyone who works with the texts for a living like you all, anyone who does that knows that Jesus Christ arrives on the scene announcing the pardon of God.

We killed him for it.

It may have taken God a couple of days, nevertheless the word went to work, working what it said, like Christ commanding the corpse of Lazarus. On the third day, the Lord declared, Jesus, come out!

See, the empty tomb is God's stamp of approval on Jesus' preaching the forgiveness of sins. Easter asserts that the absolution is absolute. This word is what God wants done. This word is what God wants said. Not that God is forgiving in general, but that God forgives you.

You are just for Jesus' sake.

As a pastor, I know how easy it can be to proclaim this word to others, but to forget to remember that it also redounds to you too.

As Luther insisted, no one can self apply the promise of grace. Even preachers need what Luther called a local forgiveness person. Therefore, before I speak any more about the gospel, allow me to do it to you.

In the name of Jesus Christ, I declare unto you, all of you, every last one of you, the entire forgiveness of your sins. You are forgiven for failing to like, much less love your parishioner. You are forgiven for foolishly believing the efficacy of God's word or the coming of the kingdom hinges on you. And maybe that's an American problem. You are forgiven for all the ways you failed at leading through the pandemic, the grievances you harbor towards the stingy givers and the resentments you nurse over lifelong churchgoers who appear to care more about the carpet color than Jesus Christ. For the time and attention you've allowed ministry to steal away your spouses and your children. For the average Sunday attendance and online worship numbers you've fudged.

All of it.

All of it on account of Jesus Christ you are forgiven, for the pardon of God is for you.

If you've not had the right hot takes in the pulpit, if you've had no idea how to make the church relevant to the contemporary world, if you've spent far too long majoring in the minors, if you're going through the motions of ministry but your faith feels like a short bed or a narrow blanket, too little to give you rest, take it from me. I am speaking for God.

You are forgiven.

Now that I've given you the goods, I can turn to the theme suggested to me by your bishop, grace and healing. And by the way, can I just confess, it is wonderful to be around a bishop at whose jokes I don't have to laugh at.

John Wesley hated bishops.

As a preacher, I don't know how to approach a subject apart from a particular scriptural text. Fortunately, we are here because we know that that is a strength and not a weakness. Mark begins his gospel not with Jesus, the party panic savior, or Jesus, the temple tantrum thrower. Mark bolts out of the gate, neither with a cute baby Jesus in his golden fleece diapers or a lawgiver greater than Moses.

There is no pregnant. ontological line in Mark like, “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” In the beginning of Mark, Jesus is primarily a healer. Only because this is Jesus, and Jesus insists on being Jesus, the theme in Mark is not so much grace and healing, so much as it is grace versus healing.

Healing is what first distinguishes Jesus in the gospel.

Healing is what draws the multitudes to Jesus. Healing is what sets Jesus apart from other sages and spiritual teachers. Across the various healing encounters in Mark and the other gospels, there is no particular pattern for how Jesus heals. Jesus does not appear to follow a consistent formula or method. Sometimes he spits in the dirt. Other times he long distance calls.

Mark presents Jesus simply as the healer and great physician. Jesus doesn't practice a rite of healing as though he were a shaman, but rather, Mark depicts Jesus himself as medicine. Healing simply happens to those who come close to Jesus. Healing is no more exceptional for Jesus than his ability to kneel at his disciples' feet or to laugh at their folly.

There's a single pattern across the gospel's healing narratives.

It's not how Jesus heals the sick, but how we respond to Jesus healing the sick.

You know the story.

Jesus is preaching in the home of Peter's mother-in-law, presumably to prevent her from preaching at Peter. The living room is so packed they've brought up folding chairs from the basement. The crowd is blocking the television screens. Even the entrance is obstructed. It is such a fire marshal's nightmare that four men who have come bearing their paralyzed friend on a stretcher find no other choice but to tear the shingles off the roof, up the sheathing, and pound a hole through the insulation and drywall in order to lower their friend down to the heel.

And Jesus may be the great physician, but he's clearly not covered by insurance. This doctor dispenses odd medicine. Mark reports that Jesus looks at the faith of the four stretcher bears, and he does not do what they have gone to all this trouble for him to do. He does not heal their friend. Like the sisters of Lazarus, the friends don’t get the result they sought.

The friends of the man on the mat believe it is a matter of life and death. But Jesus knows that it's a matter of death and life. Jesus looks at the man on the mat and declares, “Son, your sins are forgiven.”

And because the word works what it says, the man died there on the mat.

Died in his sins.

Still, I imagine that the patient of the great physician received this as an unsettling non sequitur. Perhaps it's because I worry more often than I would like to admit that those upon whom I call at the hospital would prefer a doctor instead of a preacher but whenever I read Mark's account of the man on the mat, I am first struck with the thought that forgiveness is not the medicine this man needs.

He needs medicine!

Healing.

Quite understandably, the four friends simply want their friend to get up and walk. Instead, Jesus cast this poor guy's sins into what Thomas Cramner called God's satchel of oblivion— I get a point for the Cramner quote. Evidently, what afflicts the friend of the four is not paralysis, but what the homily of salvation calls the great infirmity of ourselves. That's another point. Of course, how interesting is a prescription or even a cure really when you have the creator of heaven and earth standing before you and addressing you as son and surprising you with your sins.

That is blasphemy. Absolutely.

The Begrudgers respond to this odd remedy with what Mark euphemistically characterizes as questioning in their hearts. I mean, if they were a fraction as faithful as they pretended, they should have shouted. Only God has jurisdiction over the forgiveness of sins because every sin is fundamentally a rejection of our finitude. But like fireworks on the 4th of July or what comes after foreplay, the miracle is not really the main event in Mark. The miracle is more like the declaration. By doing what only God can do, forgiving sins, sins against God, Jesus claims he is more than a carpenter from Nazareth.

In a poem written shortly before his death, Seamus Heaney answers the great physician's question by fixing upon neither absolution nor ambulation, but upon the gift of the four friends themselves.

Heaney writes:

“Not the one who takes up his bed and walks, but the ones who have known him all along and carry him in. Their shoulders numb, the ache and stoop deep locked in their backs. The stretcher handles slippery with sweat and no let up until he's strapped on tight, made tiltable and raised to the tiled roof, then lowered for healing. Be mindful of them as they stand and wait for the burn of the paid out ropes to cool, their slight lightheadedness and incredulity to pass those who had known him all along.”

And the title of Haney's poem is “Miracle.”

And speaking as someone afflicted with incurable cancer, I'm not about to contradict the assertion that a community of friends is a gift the living God gives to those who suffer. Nevertheless, I suffer more than terminal cancer just as you suffer more than you think besets you. More to the point, suffering brought me to the realization that when the prayer book confesses that there is no health in us, it laments an ailment which stretches far beyond the medical.

There is a mighty act of God more miraculous than friends. As accessories to the act, surely you all know it is no easy thing at all to say in the name of Jesus Christ, your sins are forgiven.

It is no easy promise to proffer, especially for priests and pastors.

For you all come to learn the particular ways that people do not deserve this promise.

Not long before the bishop sent me to my present appointment, I went to the hospital to visit a parishioner (My bishop sends me places).

I went to visit this parishioner. He had had a massive stroke and his prospects appeared grim. Only months before his stroke, he had been found out by his wife and daughters. They had discovered a statement for a credit card they didn't know he carried. For years, it turned out, he'd been keeping and hiding a whole other family. Both women were with him when I arrived at the hospital room.

His wife and his other whatever.

“Princeton Theological Seminary didn't prepare me for this,” I thought as I stepped up to his bedside, at least we can dispense with the chit chat, I thought. He had tears falling from the corners of his eyes and onto the salty patches where earlier tears had dried. He struggled for what felt like a lifetime to get the word out through the wreckage between his brain and his mouth.

“Forgiveness,” he mumbled.

The word was almost unrecognizable. He was asking for forgiveness. For the forgiveness. Check this out. This guy had been a leader in the church, chair of the worship committee. He sang in the men's choir, and he dressed up as St. Nicholas for the children's sermon every Christmas Eve. And here it turned out he was near the top of the naughty list. Lying, cheating, making a mockery of the Lord. He had broken by my count a good third of the Ten Commandments.

The second time he asked for it, all he could get out was the “FFF….”

But I nodded and I told them that yes. I would give them the ab-solution.

Before I did so, I looked over at his wife, half expecting her to say to me, “Like hell you will.”

As if reading my mind, she said to me, “Well, go on. Get on with it. His girls love him too much to end up anywhere he won't be. If all that business you preach about the gospel is not true here, it's not true anywhere.”

I nodded and I stepped closer to his bedside. It felt like walking miles.

Nevertheless, I gave him an assurance he longed to hear far more than the doctors all clear.

“In the name of Christ, I declare unto you the entire forgiveness of all your sins,” I said, “You are just for Jesus' sake.”

“Thank you,” both women said to me when I finished and turned to leave.

“Which is easier to say, your sins are forgiven or stand up and take your mat and walk?”

I wonder.

Is it a rhetorical question?

After all, it is not easy at all to say when you know the specific ways the flock err and stray and follow too much the devices and desires of their own hearts. That's in your prayer book too. Credit number three.

In a former congregation, I knew a church member named Roger, a sharp, successful small town lawyer whose alcoholism and philandering had destroyed his first two marriages. And by the time I became his pastor, it was destroying him. I went to visit him in the hospital as he died slowly of liver failure. With each visit, his skin and his eyes assumed a more yellowed hue. After my final visit,

When his breathing had gotten shallow and his words confused, I knew I should stop by his best friend's house on the way back to the parsonage. I knocked on the screen door on Billy's back porch. I could hear a baseball game playing on the TV in the family room. Baseball's a game they play in America.

Billy and his girlfriend had had me over for dinner many times. So I wasn't surprised when he answered the door wearing a polo shirt that probably fit him sometime in the Carter administration. And below the waist, even tighter bikini briefs.

“Billy, I've just come from seeing Roger,” I said, “It's time.”

“You sure?”

He squeezed his eyes to fight back the tears, and he laid a bare paw grip on my shoulder to steady himself.

“You never know for sure,” I said, “but I prayed and offered him absolution. He yeah, it's time. He's definitely dying.”

And suddenly he gathered himself and he ran to get pants that were draped over the kitchen island stool.

“If he's going to be dead soon, then we've got to go to his office quick,” he said.

“His office,” I asked, “Why in the world do we need to get to his office?”

“You'll see,” he said.

“We'll be back in a jiffy, honey,” he hollered at his girlfriend, Mary.

Once we got to Roger's law office, Billy produced a key from the pocket of his pants, which also appeared designed for a fraction of the man's size. Inside, Billy dragged a heavy leather chair across the office floor. He stood up on the chair, reaching towards the ceiling, and he removed a water-stained tile. He felt around the insides of the space until he found it and then he pulled down a cardboard banker's box and he handed it to me.

“Look, Billy, I don't know that we should be doing this.”

“Shut up and take the damn box,” he said, “before I drop it.”

I looked inside the box, and suddenly I both understood and yet still didn't understand what we were doing there.

Inside the box, along with half a dozen liquor bottles, were photographs of Roger with women. The kinds of Polaroids I can't describe in a monastery. None of the women in them, I noticed, were his present wife.

“Prostitutes mostly,” Billy said, “His wife thought him different, but Roger, God bless him, he never could stop being a rascal.”

And Billy started to squeeze his eyes again against the tears and then he grabbed hold of me and cried into my hair. I was still holding the box of dirty pictures and bottles of booze.

And after an uncomfortable amount of time, I said, “Billy, what's the plan here? What are we going to do with this?”

“We're going to get it out of here so his wife never discovers it. That's what we're going to do," he said, “She thinks he put all of this behind him. We should remember, he should be remembered as the man who was forgiven, not the man who kept carrying.”

I looked down at the box and its sordid contents.

“I don't know,” I said, with not a little sanctimony in my voice. “I'm not sure that's the right thing to do. I mean, look at these. This is wrong.”

And just like that, Billy wasn't crying anymore. He narrowed his eyes and he raised his head back, angry or disappointed, and he said to me, “Do you just talk about sin and grace, preacher, or do you actually believe it?”

“I… no of course, I believe it.”

“Well good,” he said, “Because it seems to me we've got ourselves a sinner we can show some grace to before he dies. I'm gonna take this and put it away once for all.

That wasn't the only evidence we removed from his office that night, like custodians in the far country cleaning up after the prodigal who's gone home.

I didn't have time to debate the nuances of what the right thing to do was here, but clearing away the evidence of the dying Rogers sins, I felt like I was learning grace in practice.

“That's a lot of stuff,” I said, looking inside Billy's trunk.

“We've all got a lot of stuff,” he replied.

“Which is easier to say, your sins are forgiven or stand up and take your mat?”

Is Jesus joking?

We killed him for the former, not the latter. Even now, safely ensconced outside the old age of sin and death, the world is so determined to clutch on to the comfort of merit and demerit that Jesus has no other choice but to conscript preachers to proclaim it.

Doctors performed their first heart transplant the same year the Beatles recorded Sgt. Pepper's album. Every day modern medicine finds it easier to say, “Get up, take your mat, and walk.”

But “Your sins are forgiven?!”

“Who the hell do you think you are?”

She yelled at me in the narthex just before I learned that her soon-to-be ex-husband had been sitting on the other side of the sanctuary.

That was five Sundays ago.

To be nurse practitioners for the Great Physician is a hard labor, exactly because in a meritocracy such as ours, the gospel often functions as law.

Such a culture as ours hears the announcement of unconditional unmerited grace as threat, an accusation, an unjust judgment.

“For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command, yet you have never given me even a young goat so I might celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours comes, who has devoured the property with prostitutes, you killed a fatted calf!?”

What else can account for what frequently feels like a conspiracy of silence in the church where the gospel of grace is concerned? It is as though we are so afraid of making grace cheap that we have forgotten the crazy good news that it is free.

You are just, for Jesus' sake, gratis.

There's nothing more you need to do or undo, and anything you add to it invalidates it.

To muddle the gospel with the law, mixing it into a kind of gloss bowl, which is the most popular message in the United Methodist Church in America— to muddle the two is to turn the medicine, the free medicine, into an expensive, slow-acting poison.

The apostle Paul— point blank— calls it a ministry of death.

And yet we find it so tempting.

As Gerhard Forde writes:

“We need to take stock of the fact that while radical Paulinism is in itself open to both the church and the world because it announces a Christ who is the end of the law, the end of all particularities and hegemonies, it is no doubt for this very reason always homeless in this age, always suspect, always under attack, always pressured to compromise and sell its birthright for a mess of worldly pottage.”

Karl Barth notes that sola fide is really just another way of saying solus Christus, which leaves nothing else of you. In a culture of elder brothers and early risers and on time clock punchers at the vineyard, it is hard work to do this hard healing work.

To bear witness to this hard word is not easy nor without risk, for it goes against everything the Old Adam considers best and good.

We are justified in Christ alone, through faith alone, by grace alone, apart from the works of the law.

But sinners can only know this life-altering news by virtue of your work.

It's odd.

The only labor necessary to the gospel of grace is yours; you are an essential worker.

Justification is grasped through faith and faith, scripture insists, comes by hearing. Which is to say, faith comes by means of a preacher.

Put another way, the Father's heart wants the Son and all who belong to Him. And we become Christ's own through faith, and faith comes by hearing the promise. God chooses God's own through proclamation.

You are the only ones who can lead people to freedom through the proclamation of the healing promise. The only solution for God's absolute judgment is absolution.

Proclamation is the prescription that gives medicine because the gospel is a word in which Christ gives himself.

Preaching is how God elects the ungodly.

Preaching is how God applies predestination to a sinner.

Election names neither a past decision by God nor an act of God outside of time.

It is present tense. It is event. It is apocalyptic. It happens now, in and through people like you.

“This is my body broken for you.”

“This is my blood shed for you.”

“In the name of Jesus Christ, your sins are forgiven.”

Election happens in history. Otherwise, word and table are superfluous. See, the pulpit and altar are not places. They are doings. Gospel is a word that gives Christ. Therefore, preaching is not simply any word about God. It is a particular word from God.

Christ calls proclaimers, not explainers.

Explanations do not cure what ails us. The idea that God is loving or forgiving in general, that's no medicine at all. It does no one any good to hear that God so loved the world he gave his only begotten son. Rather, the sin-sick patient needs to hear it first person in the present tense, God so loves you.

Todd, he gave his only son for you.

In the name of Jesus Christ, I declare to you, Todd, you are forgiven. Get up, walk, unbound and free.

See, the gospel is not a word about salvation.

The gospel is a word that does salvation.

It is a word in which God does God to the patient.

The only remedy for our sickness unto death is to forgive it. To actually absolve it. To take the risk of doing it. Without this doing, preaching has failed.

“Give them Christ,” John Wesley told the preachers he peeled off of your church.

Give them Christ.

God did not send a book.

God sent preachers.

I've only met a few of you, but this is not how I would arrange matters. Nonetheless, it is the way God has chosen to choose.

And we live in a time when it seems that Pelagius is all but canonized. We all want to change the world and flatter ourselves that we are up for the challenge. Yet it is the hard work of faith to believe that in proclamation, word and table, God is changing things in the most radical way imaginable, by killing and making alive.

“Behold, if anyone is in Christ, a new creation.”

See, ours is more than a helping profession.

You are the Lord's hit men and midwives. Yours is the only effort necessary for sinners to be healed by grace. You are the Lord's essential workers.

Given the importance of your task, perhaps you need to rest in the same promise with which you toil.

So here are the good news:

You have died and your life is hid now with Christ and God. Everything about your labor begins after that life altering fact. The life altering fact that you have already died the only death that matters. And no matter how bleak the future appears, the odds are ever in your favor. Ministry is a posthumous vocation. And the one who called you, and the one who killed you, and the one who made you Easter new, he's in jar.

You, preachers, are not called to carry the burden of the world on your back.

You don't even have to carry your congregation on a stretcher to Jesus. You only have to bring Christ to those who are sick and paralyzed in ways they do not even perceive. You only have to bring Christ to his patients. And though Christ was once fat and heavy, laid down with all of our sins, he is not a burden to bear at all. He is, in fact, light as a feather. He weighs no more than a word. Son, your sins are forgiven.

After Roger died. I stopped by later in the week to check on Billy in search of a free meal.

The baseball game was turned on when I arrived, but the house was quiet and devoid of any dinner smells wafting from the kitchen. He answered the screen door in a different polo shirt, but the same black bikini briefs.

“Where's Mary,” I asked. And he shook his head and he looked ready to cry again.

“She left me,” he said.

“She left you. Why in the world would she leave you?”

“She saw one of the pictures of some woman, you know. It must have fallen out of the box in my car. She thought the pictures were mine.”

“But didn't you tell her it wasn't yours? Didn't you explain to her that the photo was Roger's?”

“She didn't give me the chance,” he said, “She was gone before I got home, left a long note and won't answer my calls. I guess grace comes at a cost.”

Here's my point.

God is like Billy.

Minus the bikini briefs.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 19, 2025

“Whether You Serve Like Judas or John”

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Ruth 3

I did not preach this Sunday. My oldest son, Alexander, graduated from the College of William and Mary (he won an award for public history!). Here is a recent homily on Sunday’s text by my friend Ken Jones. It was preached at the chapel at Grand View University in Des Moines, Iowa.

As we go further into the story of Ruth today, we’re at a point where something’s gotta give in order for our heroine to find some security and for God’s good providence to come to fruition, so that an heir will appear and one of Ruth’s descendants will become the king of the Israelites and a still later one will become the messiah himself. But that outcome isn’t going to happen unless someone jumpstarts things.

We know that all things work together for good, for those who love the Lord, who are called according to his purpose. Yet it seems that in this story God is willing to sit back and let Ruth and Naomi work their romantic wiles, while in his divine way God takes even unseemly scheming and makes things come round right.

At this point Ruth has been working with Boaz’s female servants collecting unharvested grain from his fields. In chaptertwo we saw that Boaz has noticed this young widow. A coy little game of wink-wink nudge-nudge has been going on. But neither part is ready to declare any interest in the other person. No invitations for a cup of coffee and certainly no explicit “I love you.”

There’s not even a heart emoji. All we have are Ruth and Boaz and a few gazes that linger a little longer than normal. Naomi isn’t willing to let things take their uncertain course, even if God does.

She’s got a plan.

Boaz is the kind of farmer who doesn’t just let his hired hands do all the work. He’ll be in the barns where the harvesters have deposited the sheaves of wheat. He’ll be there to help with the threshing. The bundles of wheat will be opened and spread across the floor, and the stalks and heads of wheat will be beaten to break open the heads, so the actual edible wheat berries will fall out. Then then it’ll all be tossed in the air, preferably with a good stiff wind, so the chaff gets blown away and the wheat falls to the ground. Little does Boaz know, but Naomi’s plan is for him to bump up against her daughter-in-law and have his heart broken open.

That’s exactly what happens when Ruth executes the plan.

There’s a lot of innuendo going on in the story that apparently makes it too dangerous to be read in Sunday worship. We don’t know exactly what happened between Ruth and Boaz beyond the fact that his antennae were finally turned to pick up Ruth’s signals. A lot of guys would have taken the situation as permission to make a move on a vulnerable woman and attempt to “Netflix and chill.” But Boaz wants to do this right. He tells Ruth she’s safe with him for the night, but in the morning she needs to do things properly rather than just sneaking and playing around with the boss.