Jason Micheli's Blog, page 4

August 17, 2025

Binding the Strong Man

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Mark 5.1-20

In an essay from 1995 entitled “Hermeneutics and the Life of the Church,” the theologian Robert Jenson recalls his PhD work in Germany during the 1950’s.

He writes:

“When I was a student at Heidelberg, the great scholars of the theological faculty there took turns preaching in the university church. It was in its fashion splendid. But every sermon began more or less the same way. After rereading the text, the eminent scholar would say, sometimes using the very same words as his predecessor, “Now—whatever are we to make of this uncanny ancient story, from a world so different from ours?”

It was presumed, you see, that we do not live in the biblical world, that its features and habits are strange to us. On that presumption, the Bible first had to be explained as an alien artifact from another world—which was always brilliantly done —and then enormous ingenuity expended to bridge the gap between the text so explained and our contemporary apprehensions—which did not always succeed so well.”

According to Jenson, there can be no such distinction between the strange world of of the Bible and the so-called real world exactly because, unlike in the religion of Plato, the God of the Bible— the God of Israel and Mary’s boy— is a God who enters into time and acts within the history he creates with us. As we profess at the font, baptism incorporates us into the mighty acts of God, present-tense.

Water, word, wine and bread make us no different than the apostles.

There is no distinction between the world of the Bible and the real world. Our world is the same world as the world of the Bible. This assertion imposes two correlative affirmations. One, Jesus works miracles today no less than he did on the far side of the Sea of Galilee. Two, we may still know the Devil and his demons by their detriments.

We can still identify the suffering ones in need of Christ’s exorcizing power.

Derek Huffman is a forty-six year old husband and father of three elementary-aged daughters. A construction worker, Huffman was also an extremely online, anti-woke, culture warrior. Both he and his wife DeAnna aspired to become social media influencers. Rapidly far right ideology and fame envy sunk their claws into Derek Huffman and his wife. In 2022, the Huffmans moved their family from Arizona to Texas. All he wanted, he declared on YouTube, was to be left alone by the LGBTQs. But Woke apparently possessed the Lone Star State too. As Derek Huffman recalled in an interview with Russia Today news, ““The pivotal moment for us was when we learned that my daughter Sophia had heard about lesbians from a classmate on the school playground. That was the last straw. Even though she didn’t fully grasp the concept, it was enough for us to realize that we needed a change.”

Derek and DeAnna Huffman responded to their daughter hearing an adult word on the playground by relocating their family to the former Soviet Union.

They did not transfer their children to a Catholic school.

They did not enroll their daughters in a Home Schooling program.

They moved to an authoritarian regime that runs rape, torture, and murder rooms in the civilian areas it captures, has kidnapped twenty thousand Ukrainian children, and routinely has political opponents fall to their deaths from open windows.

Derek Huffman scouted the possibilities ahead of his family, documenting it all on his YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. “The city was cleaner, safer, and more organized than we had anticipated,” he testified, “Most importantly, we found a place where our values were honored, and we felt at home.”

Did the Huffmans have any personal relationships in Russia?

No.

Did Derek or DeAnna have any job prospects in Russia?

No.

Does anyone in their family speak Russian?

Again no.

Such common sense considerations were overpowered by their anti-woke dogma and their desire to become social media superstars. The family emigrated to Russia last year with their husky through Russia’s “shared values” visa scheme, aimed at attracting foreigners who reject what Vladimir Putin calls “destructive neoliberal ideology.”

In order to prove himself to his new nation of choice, Derek Huffman— who, again, is forty-six years old with no prior military experience— volunteered for the Russian Army’s invasion of Ukraine.

On his YouTube channel, he said:

“The point of this act for me is to earn a place here in Russia. If I risk myself for our new country, no one will say that I am not a part of it. Unlike migrants in America who come there just like that, do not assimilate, and at the same time want free handouts.”

And to his wife via video message, Derek Huffman explained his decision thus:

“I believe in the Russian cause. . . . I won’t sit here and act like I’m the know-it-all on the whole situation, but I know enough to know that Russia is just in their cause and they’re doing the right thing.”

After matriculating through a brief basic training conducted in a language he could not understand, Derek Huffman was made a happy participant in Russia’s war crimes. Initially promised by Russian officials that his duty would be limited to welding or perhaps journalism, the army immediately sent Derek Huffman to the front lines in Ukraine.

His wife DeAnna streamed her worries to her YouTube channel:

“Unfortunately, when you’re taught in a different language, and you don’t understand the language, how are you really getting taught? You’re not. So, unfortunately, he feels like he’s being thrown to the wolves right now, and he’s kind of having to lean on faith, and that’s what we’re all doing.”

“I want to be hero,” Derek Huffman volunteered in one of his final live streams to social media, “To prove I belong to my new country, I want to be a hero.”

Make no mistake.

This just is what the scriptures name as demonic possession.

The real world and the world of the Bible are the same world.

Ideology and antagonism, greed and envy, twisted Derek Huffman into a wolf on the front lines of a war crime. Though he donned camouflage rather than chains, he is no less bound than the Gerasene who lives among the tombs beside the Sea of Galilee. The One whose names are many bound both of them.

In Matthew, Mark, and Luke alike, Christ’s encounter with the Gerasene Demoniac contains more lavish detail and rhetorical flair than any other single episode in the Gospels. This does not mean, however, that the exorcism is an aberration in his ministry. As Peter preaches in the Book of Acts, exorcism is a summating term for his entire work: “God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power; he went about doing good and healing all that were oppressed by the devil, for God was with him.” The novelist Flannery O’Connor famously characterized the subject of her fiction as “the action of grace in territory largely held by the devil.” The New Testament understands the incarnation of the Son of God likewise. As much as he is a Teacher, Prophet, or Redeemer, Jesus is an Exorcist; or rather, exorcism is a critical and necessary component to his work of redemption.

In the Gospel of Mark, immediately before this passage, Jesus has just rebuked the wind and calmed the storm at sea, saying, “Peace, be still!” Astounded more so than relieved, the disciples ask themselves, "Who then is this, that even wind and sea obey him?” When they arrive on the other side of the Sea of Galilee they at once encounter One— or Many— who knows the answer to their question. Gentile territory, Gerasa lay on the edge of the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire.

Gerasa is forbidden territory; for a Jew like Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim everything here is taboo. The presence of a herd of pigs, the litter of tombs where they land their boat, the possessed man in chains: all of it is unclean and therefore out of bounds. Two chapters earlier Jesus had taught a parable in order to explain his contending against the Devil’s work. “No one can enter a strong man’s house and plunder his goods,” Jesus said, "unless he first binds the strong man; then indeed he may plunder his house.” Now on the shore in Gerasa, Jesus encounters such a strong man.

Mark reports that the Gerasene man:

“…lived among the tombs; and no one could bind him any more, even with a chain; for he had often been bound with fetters and chains, but the chains he wrenched apart, and the fetters he broke in pieces; and no one had the strength to subdue him. Night and day among the tombs and on the mountains he was always crying out, and bruising himself with stones.

As soon as Jesus sets foot on shore, the man rushes to meet him and makes himself prostrate before Christ. This is only one of two occasions when Jesus converses with a demon. The parasitic power oppressing this Gerasene man knows the identity of Jesus and thus fears him for it knows Jesus possesses the power to drive it out. Just as they are in Gentile territory, the demon greets Jesus not with a Hebrew or Greek salutation but with a Latin one— a Roman one, “What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I adjure you by God, do not torment me.” Similarly, when Christ compels the demon to give his name, he proffers a Latin word with only a single association for Jews, “My name is Legion; for we are many.”

Comprising approximately five thousand infantrymen, a legion was the largest permanent organization in the armies of Rome. Their standards bore the image of wild boar— swine. Just as a legion occupied and oppressed this Gerasene man, Israel itself was possessed by legions sent by Caesar. This is not a clever narrative detail on the part of Mark the Evangelist. This is Satan revealing what Christ’s Passion soon will confirm, that the alliance between Religion and Politics is not simply sinister but demonic.

The man living among the tombs is the world in nuce.

Note the language of invasion.

The demon begs Jesus not to expel him out of the country, not from the man’s body but out of the country. Knowing resistance to the Word of God is futile, Legion pleads with Jesus to send them into the swine who root among the tombs— about two thousand pigs, Mark reports. Jesus submits to their plea. Straightaway, the herd of occupied swine “rushed down the steep bank and were drowned in the sea.”

As my teacher Donald Juel wryly comments on this passage, while our sentimental, Gentile minds may ponder the enormous cost of lost livestock, for the restoration of one suffering man’s humanity Jesus considers the price “worth it.”

In recent social media missives, DeAnna Huffman has lamented that her husband had been misled in the military recruiting process.

She said, “When he signed up and had all of that done, he was told he would not be training for two weeks and going straight to the front lines,” she said. “But it seems as though he is getting one more week of training, closer to the front lines, and then they are going to put him on the front lines.” She added that the deployment has also created financial strain for her family. Derek and his unit members were reportedly required to “donate” ten thousand rubles for their own supplies, eating up a large chunk of his paycheck. DeAnna reported receiving no pay or bonus after one month of Derek’s service.

She concluded her live stream on social media with a plea for prayers.

For deliverance.

Here is my question.

If the LORD Jesus delivers Derek from the dangers of the front lines, if Christ does indeed free him and his family from the oppressor who occupies them and redeems them back to a life in America, how do you think Derek and DeAnna would respond?

The Gerasene man was so grateful he wanted to get in the boat and go away with Jesus, hoping to become a disciple; so, no doubt Derek— now in his right mind— likewise would be overwhelmed with indebtedness. But what about the thousands upon thousands of social media followers who lauded and shared the aspiring influencers’ foolish attempts at fame and “owning the libs?” Would the hundreds of thousands who liked and followed and retweeted their misadventures express gratitude and joy over their deliverance?

The Bible tells me no.

When the citizens of Gerasa— those in the city and the country— learn what Jesus has done for this man living among the tombs, they do not want anything to do with Jesus. In fact— pay attention— they use the same language Legion had used when the man ran to the beach to meet Jesus. They beg Jesus to leave.

Why?

Again, this is the most detailed episode in the Gospels; thus, the details are all here for a purpose. When the former demoniac begs Jesus to take him with the twelve into the boat, Jesus refuses and commands the man, "Go home.”

He has a home!

“Go home and to your friends.”

He has a home and friends!

And yet, whoever is at home, whoever are his friends, have let this man live among the tombs. They abandoned him. What could lead them to view their family member and their friend as disposable? Or rather, who could so lead them?

Legion’s possessive power extends beyond those who are obviously afflicted. Don’t you see what the details want us to see: the man among the tombs who could not be chained or fettered is not the only person bound by the Enemy in Gerasa.

“Go home and to your friends, and tell them how much the Lord has done for you, and how he has had mercy on you.”

How excited do you think the other demons would be to hear that their Adversary has just freed a man from their ally’s grip?

They begged Jesus to leave their country.

What’s more—

Do not miss what Mark discloses in the initial details of this story. The possessed man apparently poses no danger to anyone else. He is a strong man but he is safe. His constant wailing is a nuisance not a threat, yet they have treated him like a prisoner, fettering him (unnecessarily) again and again. And they have exiled him to live in a place unclean even for a Gentile— out of sight, out of mind.

They begged Jesus to leave them. The possession is more pervasive than a one man on the beach. The real world and the world of the Bible are one and the same world; that which is truly demonic does not look like a scene from The Exorcist.

In his forthcoming book God’s Adversary and Ours, the theologian Phillip Ziegler draws attention to the nature of Christ’s exorcisms as social reintegrations.

He writes:

“Divine rescue and liberation from diabolical oppression: this is the exclusive focus of evangelical interest in exorcisms….The possessed are regularly socially excluded, hidden away, lurking in cemeteries, or in the wilderness, or outside the gates, their suffering thus amplified by social exclusion. Jesus’ exorcisms— like his healings more generally— also repeatedly make for social reintegration. The casting out of demons brings with it the casting out of the victim’s casting out from the community, as it were.”

In other words, Jesus’ work of exorcism will not be complete until this Gerasene man is returned to his home. This man returning home, answering to his name again and not to Legion, is the only way his family and friends will be set free from the demons that so possessed them that they chained him and cast him out from them. That is, Jesus refuses this man’s request to get into the boat because Jesus needs this man to be his emissary in Gerasa. Jesus needs this man to finish his work. Now that this freed man knows who is stronger than the Strong Man, he can set loose his friends and family with the mighty name of Jesus.

DeAnna Huffman and her three daughters have not heard from Derek since Father’s Day though DeAnna recently posted on social media a denial of reports that her husband had been killed in action.

I have repeatedly doom-scrolled stories about the Huffman family since I first learned about them earlier this summer. When I think of that mother and father, I am filled with rage and contempt and scorn, haughtiness and schadenfreude and malicious glee.

I do not know how to interpret emigration to Russia as anything other than endorsement of lies and evil. I cannot understand how volunteering for Putin’s army could be anything other than support for the rape and torture of civilians and the kidnapping of children. And I cannot stop thinking about what their dreadful— abusive— decisions mean for their three daughters. It is terribly easy to imagine what the future holds for three young girls trapped in a despotic foreign country with no education, support network, financial resources, or even the ability to speak the language. They will be vulnerable to the worst sorts of predation.

Whenever I think of Derek and DeAnna Huffman, I am filled with rage and contempt and scorn, haughtiness and malicious glee.

But seldom do I express pity.

I’ve got chains on me I cannot see.

Not only is pity what my baptism demands of me.

My righteous anger, if directed at Derek and DeAnna, is misplaced.

Because our world and the world of the Bible are the same world.

And in the Bible, the possessed themselves are never construed as enemies of the LORD.

As Phillip Ziegler writes:

“Crucially, we note that across gospel testimonies to Jesus’ exorcisms those possessed are themselves never construed as the enemies of the Lord; they are rather the children of God, sons and daughters of Israel. The enemy of the exorcist is someone, something, other; namely, that uncanny power that has usurped their lives. Jesus and the possessed have a common adversary: the diabolical purveyor of misery…these episodes of exorcism forcefully remind us that not only human malfeasance but also human misery are the object of Christ’s saving work…Jesus’ practice of exorcism is the merciful movement of God against that afflicting power which dissolves creaturely life and estranges us from our neighbors…victims of which we ought to pity and not cast away.”

According to DeAnna Huffman’s social media appeals, she has been petitioning Vladimir Putin’s administration to get Derek reassigned to a non-combat role.

When I read that news, I was finally free to pity her.

The effects of the Devil’s possessing power are everywhere.

There is as much misery as there is malfeasance in the world.

Like the Gerasene man, we can go home armed with the name of Jesus but how much can we truly do? The headlines are overwhelming. The scale and scope of the misery is crushing. I am not an effective exorcist. Are you? Let’s be honest—to speak life in such a world can feel as hopeless and futile as DeAnna Huffman attempting to navigate unnamed, uncaring bureaucrats in the Russian regime.

If the message of the gospel is that it is up to us to continue the movement begun by the dead Jesus, then we are the ones to be pitied.

But thank God the world of the Bible is our world.

Because notice in our passage.

As he rushes to the beach, the demoniac cries out to Jesus, “What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I adjure you by God, do not torment me.” And see how Mark puts the next verse, “For Jesus had said to him, “Come out of the man, you unclean spirit!”

But Jesus has not yet spoken!

According to the narrative, the first time Jesus speaks audibly is verse nine, “And Jesus[ asked him, “What is your name?”

Jesus can speak without speaking.

Jesus can speak without opening his mouth.

Luke recounts the encounter in this same odd way.

“When the man saw Jesus, he cried out and fell down before him, and said with a loud voice, “What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I beseech you, do not torment me.”

Next verse, “For Jesus had been commanding the unclean spirit to come out of the man.”

Once again, as in Mark’s Gospel, Jesus does not audibly speak until the following verse. Jesus has been speaking to this man long before Jesus opened his mouth on the beach. And the man has heard the Word’s words.

Hear the good news:

In this world of misery and malfeasance, there is (nevertheless!) more being spoken and heard than you can see. And he who speaks just is the Word whose words give life to the dead and call into existence the things that do not exist.

There is nowhere the Adversary is not.

But there is nowhere— no time— Jesus is not speaking.

And one little word from him can fell the devil himself.

Hear the good news:

The strange world of the Bible is our world.

Just so, he is speaking life into it.

Before the Gerasene’s ears even heard a sound—Jesus was already speaking.

While Derek and DeAnna were still bound by the allure and antagonism that had ensnared them, the Word had already taken pity on them and was at work to loose them.

Jesus means freedom.

Not just from sin but from suffering.

And I suspect you have more familiarity with the former than the latter.

One of you is miserable, overwhelmed by the heartache of an estranged son and his family. Another of you could not bury a loved one this summer without the undertaking devolving into the addiction-fueled acrimonies of old. Someone here is bound in bitterness for the wife who left him while still another bears the misery of a wife he loved who was lost.

Jesus means freedom.

From misery as much as from malfeasance.

And whether your ears have heard a word from the Lord, it does not matter. Because the world of the Bible is this world and, therefore, Jesus has already been speaking his exorcizing word against the powers that bind you.

Before you even feel the weight of your misery, before you know to name your demons, before you can even string together words to beg for help—Jesus is always already speaking.

In this world, in your world, in the mess of your life and in the mess that is mine, the Word is speaking. He is speaking into every hospital room and rehab facility, into every war zone and into marriage that is like a war zone, into every lonely bedroom and into every doomscrolling night. Whether you hear him audibly or not, he is speaking into your shame. He is speaking into your fear. He is speaking into your sin.

And when Jesus speaks, demons tremble.

When Jesus speaks, chains shatter.

When Jesus speaks, tombs turn into turning points.

And the promise of the gospel is that he will speak his freeing word until every misery that binds you has to pack its bags and rush headlong into the sea.

So be not discouraged!

You are not left to fight on your own.

You are not abandoned to your misery.

The Lord Jesus Christ is already speaking, already commanding, already making the unclean clean, already calling you by your name and not by your chains. And take this passage as proof— there is no taboo he won’t cross, no place he won’t venture to find you and free you.

And if you doubt that Jesus can speak without speaking, hear the good news.

It is odd of God, but he can also speak through a sinner like me.

And here and now, he says to you, “This is my body, broken for you. This is my blood, poured out for you.”

Some come to the table.

The fetters that bind you are easily broken.

Come, taste and see that loaf and cup are tokens of his promise.

His promise that when he speaks, even the most absurd captors must surrender. When he speaks, even misery must listen. When Jesus speaks, even your demons must go for a final swim.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 15, 2025

The Devil is an Essential Character in the Gospel’s Dramatis Personnae

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

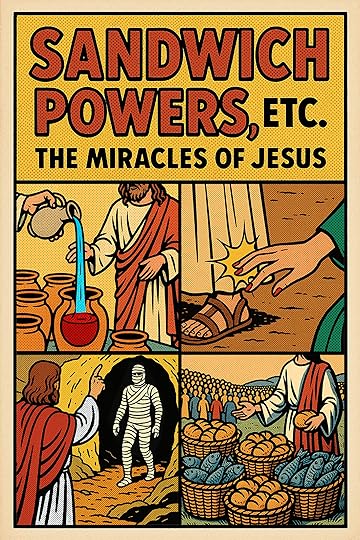

This Sunday I will continue a long sermon series through the Miracles of Jesus by preaching on the story of the Gerasene Demoniac in the Gospel of Mark. In all three synoptics, it is the most lavishly detailed story outside the Passion narrative. The passage draws attention to the fact that many of Christ’s miracles are exorcisms. As much as he is a Teacher, Prophet, or Redeemer, Jesus is an Exorcist; or rather, exorcism is a critical and necessary component to his work of redemption.

As Peter proclaims to Gentile hearers in the Book of Acts:

“God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power; he went about doing good and healing all that were oppressed by the devil, for God was with him.”

The story of the Gerasene Demoniac is a reminder that the Devil is an essential character in the Gospel’s dramatis personnae; therefore, our understanding of Christ’s salvific work is unintelligible if it shirks from accounting for the Enemy. Though we allegedly live in a secular age, the scriptures demand we deal with the One whose names are Legion.

In a 1989 essay entitled “Evil as Person,” Robert Jenson repents of having avoided the subject of Satan in his theological writing. Jens admits that while he knew there was evil in the world and though he knew the scriptures speak of demons and their Devil, as a good modern scholar he simply treated this as background noise to the project of Christian proclamation.

This was a mistake, he confesses.

That it was a clear error is obvious from two central Christian claims:

There is God.

There is evil.

The goodness of the former rules out a causal relationship with the latter, thereby requiring a third claim:

There is Evil as Person.

Not just as a principle, a system, or a force, but a someone.

From this straightforward if perplexing assertion, Jenson proceeds to the doctrine of creation. To confess the biblical God is first to say that reality itself—especially as history—has a moral intention. The world is not indifferent. It is valued and loved before we value or love anything. But this is not yet the full confession of God. God is not only moral will but personal reality. The difference is this: you can speak to a person, and a person can respond. Prayer is possible. God listens and engages, not because He lacks knowledge or power, but because His very being includes relationship. He is willing to be addressed and to respond.

If the ground of reality is personal love, then the world’s moral disorder is not merely chaos, Jenson argues. Somewhere in reality there is a will that hates. Not an abstraction, but a subjectivity that comprehensively despises creation—just as antecedent to our own hatreds as God’s love is to our loves.

The world’s moral disorder is not chaos; somewhere in reality there is a will that hates.

August 13, 2025

"The Preaching of the Church would be an illusion if the distinction between the Jesus of History and the Christ of Faith were possible."

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Here is Monday’s discussion of Bonhoeffer’s “Lectures on Christology.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 11, 2025

Faith is the Threshold to All Knowledge

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

Our Monday Night Live group will meet again tonight at 7:00 EST to discuss Bonhoeffer’s “Lectures on Christology.” Subscribers will get an email and link shortly before we go live.

Here is the reading for tonight:

Bonhoeffer Reading 21.21MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadAnd here is my summary of its themes:

When it comes to proclamation, one of the dangers of glawspel— muddling the gospel with the law— is that it inevitably treats Jesus like a helpful add-on to the Christian life. Like the optional extras at a car dealership (heated seats, leather trim, a moonroof) Jesus is nice to have, but you can still drive off the lot without him.

Jesus is not your co-pilot.

“Jesus is my savior” does not even cut it.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer saw the whole of existence—your life, my life, the mess and beauty of history, the groaning of creation itself—as orbiting one singular, non-negotiable center: Jesus Christ. And for Bonhoeffer “Christ” denotes neither the projection of our best selves nor a religious concept but Christ in the flesh, crucified and risen.

The Jesus with calluses on his heels and holes in his hands is the center of all reality.

In his “Lectures on Christology,” Bonhoeffer says that Christ stands where you stand and— thank God— Christ stands where I cannot stand. Jesus is the hinge point between your old self (the one so good at self-justification and self-destruction, the one glawspel flatters so) and the new self you can’t make for yourself. Christ stands in our place, Bonhoeffer teachers, representing the boundary between our old and new self. That is, the law—God’s good and holy will—stands between the old and new Adam as fixed as a brick wall. On our own, depending only upon our own righteousness, it smashes us to pieces every time.

Christ does more than stand with us as we crash against the boundary that is the law. Christ takes the hit for us. He both becomes the law’s condemnation and its fulfillment, thereby opening a path through the boundary into newness of life.

Thus—

“Christ the Center” is neither sentimentality nor spirituality.

Bonhoeffer’s point is not psychological but ontological.

This is not about how you perceive the world around you. This is who you are before God. Christ is not one of the ways you find balance in life. Christ is the ground on which you stand— even if you don’t know it.

He is the one without whom there is no such thing as “you” at all.

In his lectures, Bonhoeffer then pans out, widening the horizon.

Christ is not just the center of my existence; he’s the hidden center of history. Bonhoeffer insists that history is messianic. History is not simply one damn thing after another, from elections to wars to American Eagle commercials to oncology appointments. Despite appearances, history is moving from promise to fulfillment.

It’s his story.

According to Bonhoeffer, at the heart of reality is the promise of God becoming God’s people, fulfilled in Christ. This means the cross is the judgment and the justification of the world’s powers, which, correlatively, makes the church as Christ’s Body the center of history.

The church is the center of this movement from promise to fulfillment, for it is the church where the state learns it is not God and the poor learn God is for them.

That we use the term nature rather than creation makes it difficult for us to speak Christian in Bonhoeffer’s terms. In nature, everything is already as it is ordered according to physical laws. But in creation, nothing is presently as God originally desired. Creation, Bonhoeffer says, reading St. Paul, is groaning under the curse of the fall.

Creation needs liberation.

Salvation includes all of creation just as much as it includes the creature you call you.

Much like Maximus the Confessor, Bonhoeffer sees Christ as the new creation in person. In Christ, nature’s servitude ends. Its future isn’t extinction but resurrection. Christ is the mediator not just between you and God, but between the world itself and God. And in the sacraments creation’s future breaks into the present. Ordinary creatures of water, wine, and bread become participants in the eschatological feast.

Christology is cosmic.

Christ will not remain merely the center.

Christ is becoming all things.

One of the invigorating aspects of Bonhoeffer’s Christology as it appears in these lectures is his refusal to distinguish the so-called Jesus of history from the Christ of faith. Such a distinction, he argues, is impossible. You can neither prove nor disprove the resurrection by historical research. Rather, faith in the risen Christ is what opens the door to the historical Jesus. It does not matter what original document you posit behind the Gospel of Mark, without Easter faith, you will never find Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim.

This is a bold move.

Bonhoeffer inverts our logical expectations. He says our access to the historical Christ is through the resurrection not the other way around. It is not the case that first you prove historically that Jesus existed and then you add faith to this knowledge.

Faith is threshold to all knowledge.

In his lectures, Bonhoeffer addresses an ancient heresy that is never far from the church: docetism— the notion that Jesus merely appeared to be human. Bonhoeffer understands the temptation, for a God who only looks human is so much easier to handle much less comprehend. A God who has a mother and an executioner is an impossible paradox; nevertheless, docetism guts the gospel.

If Christ is not fully human, he cannot redeem humanity.

The early Church smelled the danger and condemned it. Bonhoeffer agrees. Only as one of us can Christ be completely for us.

Back to the starting point—

With his emphasis on Christ as the Center, Bonhoeffer is eschewing any reductions of the gospel that render Jesus into a mere accessory to our lives. If Christ is the Center of your existence, then you do not have a life apart from him. Thus, any understanding of your life without him is an aberration.

If Christ is the Center of your life, then he’s already got you before you knew to look for him.

If Christ is the Center of history, then every headline is provisional, relative to cross and empty tomb.

If Christ is the Center of nature, then the redemption story includes more than you and me, every eucharistic loaf is a preview of wheat and soil and sun brought to their fulfillment.

Admittedly, these lectures are denser than I recalled, but Bonhoeffer’s point is nonetheless uncomfortably clear.

Christ doesn’t fit into your life.

Your life is hidden with Christ in God.

All things are hidden with Christ in God.

And if that’s true, then everything—everything—is re-centered.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 10, 2025

The Prohibition of Faith

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

John 9.1-12

Jesus has just escaped an attempted stoning in the temple.

This where the miracle story begins.

At the temple, engaged in a fierce dispute with the religious leaders, Jesus implies that his antagonistic interlocutors are slaves to sin. He does so by declaring himself to be the truth with a capital T. “If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples,” Jesus announces, “and the Truth will set you free.” “So they picked up stones to throw at him,” John understatedly reports— before adding, cryptically— “but Jesus hid himself and went out of the temple.” As Jesus and the disciples exit the temple, they encounter a man blind from birth.

The conflict in the temple is the context of the ensuing sign.

Whether Jesus and the blind man cross paths providentially or coincidentally we cannot know; however, in the Gospel of John the Evangelist makes it clear that their convergence serves to corroborate the preceding claim made by Christ. That is, we can see Jesus is the Way and the Life and the Truth by the salvific work he performs upon the man born blind. The blind man serves to verify the truth claim made by Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim; likewise, faithful interpretation of this passage demands that we test the claims believers make about Jesus Christ.

Faithful interpretation of this passage demands that we test the claims believers make about Jesus Christ.

In his inaugural lecture at Gettysburg Seminary in 1968, the theologian Robert Jenson made this assertion about the necessity of testing our beliefs:

“Christian faith is in many ways a prohibition. I am prohibited from holding my beliefs to be true simply because they are my beliefs. I am prohibited from holding my beliefs to be true simply because I have always entertained them or even because my whole culture has entertained them. To be Christian, to be faithful, is to break from mythic existence and to be ready to submit all my beliefs to whatever is in each case the appropriate test…in such a way that you can judge the reasons for my beliefs.

The believer in the promise of the gospel is called to live life as a wager and to submit our beliefs to public tests. I obey the prohibition of the faith when I refrain from claims backed up only my private experience.”

In other words—

If Jesus is the Truth, if it is true Jesus lives with death behind him, if Christ is risen indeed, then he is not merely an item of the past but an actor in the present. Just so, we may expect him to do among us the same works which he wrought in the Galilee and at Jerusalem’s temple. Thus, the gospel’s credibility depends upon our ability to point to others upon whom the living Christ has worked just as he did the man born blind.

For exhibit A, I offer you the following from my inbox.

I have over thirteen hundred emails in my inbox from Shirley. Whenever doubt seeps into my faith— and that happens to pastors more than you might guess— I reread Shirley’s emails to me.

Here's the first from Shirley.

July 5th, 2005

Subject: Communion, et cetera.

Dear Jason,

Welcome to our wonderful church family. We met on Sunday morning. I was the good looking lady with the Arkansas accent who leaving church asked you, “You're not a Republican, are you?” I whispered it pretty quietly, I don't know why you didn't answer me. You probably noticed I didn't take communion Sunday. The reason I didn't was because I nearly choked on the piece of bread you gave me. It was large and had a lot of crust on it. I should have gone ahead and dipped it in the wine and just kept it in my hand until I got to the pew, but then my hand would have been all sticky, and who wants sticky hands? I might have had to shake a visitor's hand after worship, and then they would have thought I'm one of those terrible, disgusting people who have sweaty hands all the time. Gross. I can't help but wondering, do they teach you in seminary how to break off smaller pieces of communion? Probably not, I guess. They obviously don't teach you how to slow down and not talk so fast either. You'll learn.

On another subject, I heard a minister yesterday on TV who I think is just great. The reason I was so impressed with him was because his message was about religiosity versus spirituality. He quoted Joel 2.28 and emphasized the noun everyone and how God wants everyone to have an alive spirit. His name was Joel Ostein, I think. You should look him up. I haven't heard you preach yet, but I bet you preach just like him.

Your new friend, Shirley Pitts.

PS: Did your last church not have a problem with your earring?

October 13th, 2005

Subject: Coffee with the Pastor.

Jason,

To follow up from last night's Meet the Pastor's Coffee, I most certainly did not purposely spill coffee on your crotch just because you told everyone how John Wesley supposedly was a terrible husband. I told you, it was an accident. But I will say, if I had done it on purpose, you would have deserved it.

Why did you spend all your time last night talking about Martin Luther. And I’ve never even heard of Karl Barf. You're supposed to be a proud United Methodist, and there you were last night bad-mouthing the founder of United Methodism. I couldn't believe it. I got so angry, I could have, well, never mind. And another thing, I did not roll my eyes at that new member when he said he worked for the House Republicans. Maybe I was a little rude to him, but not rude enough that anyone would notice. You've got a loud nerve accusing me of such things. Keep it up and I'll bet you don't last at this church more than a couple of years.

Shirley Pitts, longtime member.

May 22nd, 2006

Subject; Fall Commitment Campaign.

Jason,

I have decided to withdraw from the Commitment Campaign Committee. I was so disappointed that the last meeting wasn't more civil. It's a shame that even in a church setting among Christians, the people can't value another's opinions. I just hate how some Christians gripe and gossip about other Christians. I could tell you a thing or two about some of those complainers at the meeting.

They're the reason we're in the mess we're in with our debt and I heard one of them hardly even speaks to his wife. Maybe it's because he knows she's got someone else on the side, but you didn't hear that from me.

Don't worry, I'll still be in charge of the Meet the Past for coffee. Lord knows, if I'm not, you'll never tell our new members about John Wesley or what it means to be a Methodist. And where would we be then?

Shirley.

September 6, 2007

Subject: Communion Bread.

Dear Jason.

Like I told you Sunday, I heard a lot of comments about the bread we had on Sunday for communion. It was sourdough and it just didn't taste well with the wine. Think about it for gosh sakes. It's called sour dough. Who wants to eat that? I bet Jesus refuses to even make himself present in bread so disgusting. I hope you were joking when you said we could switch to wafers. This church will never go for wafers. We are not Catholics. Next, you'll be telling us to worship Mary and not read our Bibles like Catholics.

Blessings,

Shirley

September 9th, 2008

Subject: Babies.

Jason,

When I was a social worker for child welfare in Little Rock, one day I came into the office to bring a baby for adoption. My boss looked at the way I was holding the baby and got all over me because she said that I should cradle a newborn baby in my arms. She said a young baby cannot hold up their head when they are so young and they could hurt their hearing if it tumbles over.

I thought of what my boss said yesterday watching you juggle that poor baby all over the place during the baptism. Maybe you should practice a little using a doll baby. Maybe I could find one at the Goodwill for you to use for practice. Not that I shop at the Goodwill myself. I imagine it smells like people who hassle you for handouts on the street. But I'd go to the Goodwill for you if you'd like me to look.

Hope this is helpful.

In his service,

Shirley

April 3rd, 2009

Subject: I forgive you.

Pastor Jason,

Of course, I know that ministers are people just like the rest of us, but in all my years in the church, I have never heard one lose their temper and say the sorts of things you said to me on Tuesday. I'm not sure what you meant by calling me a church lady, but I understood busybody all right. I should have known I was getting on a nerve when I saw your ears turn red like they do when you get excited in the pulpit. But when our unmarried church secretary is pregnant, again, I don't think it's out of bounds to wonder if she's going to remedy this situation and make herself a godly woman. I expect you regret slamming your office door so hard that ridiculous picture of Karl Barth fell off your wall. Well, even if you don't regret it, I forgive you. I don't understand why I upset you so, but I hope you can forgive me too.

Shirley

November 11th, 2009

Subject: Paul

Jason,

I wish you had known my husband, Paul. I still have people coming up to me and saying how they miss him.

He held about every position you could have in the church. He was fun and caring and a wonderful husband and father. He was a commander in the Navy and was on three submarines. Mostly though, I wish you'd known him because he was such a good Christian man. He was a better man than I deserved. Maybe you would think better of me if you could see how he thought I was better than I am. Actually, I suppose he knew exactly who I am and loved me anyways.

I guess that's why you're always going on about grace. Lord, sometimes I think you've only got one sermon in you, but you've learned to preach it a hundred different ways. But when I think about Paul, I understand why maybe you do.

Shirley

December 14th, 2011

Subject: Jews

Jason,

Where is it in Romans that Paul tells about how the Gentiles were let in to be loved by God even though they didn't deserve it?

I have down here that you told me Romans 9 through 11, but that doesn't jive. My daughter-in-law doesn't think the Jews will be saved, and I told her you said they were saved. Of course, the bigger point seems to be that God responds to us killing Jesus by giving Jesus right back to us, so I don't know why anyone would think God's stingy with His grace. I don't know why, but lately more and more, I think about how I don't deserve God's grace. I've not always been a good or kind person. I've often been mean. I guess that's why they call it amazing grace, huh?

By the way, I hate it when you make us sing all the verses of hymns like “Amazing Grace.” Good Lord, who can stand up for that long and huff and puff through seven verses?

Love,

Shirley

January 14th, 2012

From shirleympitts@cox.net f

Subject: Christmas

Jason,

I teared up when I read your Christmas sermon thinking about how unconditional God's love is for us. My love for my boys has always been unconditional for sure, but for other people? For people, I think my love has always come with strings attached. I know my love for you certainly wasn't unconditional.

Remember that time years ago when I got furious with you because you wouldn't teach the Meet the Pastor folks about John Wesley and I stormed out of your office and slammed the door so hard that picture of Karl Barth fell off your wall again? Of course you have a picture of Karl Barth on your wall and not John Wesley, but never mind that now.

See you Sunday,

Shirley

January 23, 2012

Subject: _____________

Jason,

After church, I went out to eat at Ruby Tuesdays with a bunch of women that usually go there after church. They started talking about the election. After a while, I told them that I was a Democrat. Marguerite said, are you a liberal? I said I wasn't, but I think I am. Then someone, I won't say who, but she used to work at the church. I think you know who I mean. She said, “All Democrats are liberals.” I forgave her. I really did forgive her, too. It used to be that I wouldn't have. You know what I thought about it afterwards? That life is too short to waste it on petty grudges. I don't know if I thought that because I'm getting older or because I'm getting more Christian. What do you think, I wonder? Maybe we confuse holiness with getting older and no longer having the energy for some of our usual ways of sinning.

I just wish we had more Democrats in our church!

If you ask me, the Republicans need to be in the Baptist church.

Shirley

February 6, 2012

Subject: New Members

Jason,

A couple named Kelly and Joe put down that they would like to join the church. I called her and come to find out she went to middle school, high school, and college with you. I asked her if you're the same now as you were back then, and she said no. She said you were nice back then, but that you're different now, too.

It got me thinking about what people who knew me way back when would say about me today. Would they say I'm no different than I was? It makes me really sad to think that maybe they would. I can't think of anything worse than to have gone to church your whole life and not end up a different person, can you? But if Jesus is not dead, as you're constantly saying, you really should come up with some different turns of phrase.

If Jesus is not dead, then it seems to me stupid. It seems stupid to me to think that people can't change. I hope he's changed me. I suppose I'm about the last person who could judge such a thing.

Shirley

April 6, 2012

Subject: Jesus.

Jason,

I know you're busy with Easter things, but this has been on my mind. When I've prayed before, I've always prayed to God, not Jesus.

I love Jesus, and I know He did so much for so many, but I've always thought I needed to pray to God. I've started to pray to Jesus lately, like you do in church sometimes. And you know what? Praying to Jesus, like I'm talking directly to Him, makes me a lot more conscious of being more like Him, which makes me more conscious of how much I am not like Him, which makes me more conscious of how gracious He must be to love someone like me. It's surprising how coming back to that again and again, like a circle, has made such a difference to me and I hope in me.

Shirley

August 13th, 2012

Subject: Naked

Jason,

About an hour ago I was driving down Fort Hunt Road and I saw a man I thought was naked like that man in Mark's gospel when Jesus is arrested. What an odd detail. Anyways, I thought this man was naked, but when I got closer, I saw he just had a shirt off and some terrifically short shorts. When I saw that it was you I whistled out my window.

Did you know it was me?

You should be careful going around like that, half naked. There's a lot of older women in our congregation who've been missing their men for a long time.

Ha!

Lord, I hope you never mention that in a sermon.

My real point was to say that years ago, seeing you like that, running around like a Chippendale, would have irritated me something awful. But instead, I just laugh because I've grown to appreciate you.

I guess that's God's grace.

Lovingly,

Shirley

May 22, 2013

Subject: Les’s Funeral

Jason,

You did a wonderful job with the funeral yesterday. In fact, I left praying that you'll be the one to do my service one day. Funerals should be honest about how every Christian is a mixture of sinner and saint. You know better than most my ratio of those two qualities. I think funerals can afford to be honest too because of how you put the gospel one time in your sermon on the prodigal son. You said God says to us, nothing you can do can make me love you more, nothing you do can make me love you less. I've done plenty, I confess.

Your precious boys who are Hispanic, your precious boys make me regret every ignorant thing I have ever said about Hispanics. I've never been racist, I don't think. But ignorant? Probably. Probably in ways you can't even notice when you've grown up in a place like I did in Arkansas. I wonder if that's what's meant by original sin. You're just born into sins like racism and you need God's help to exercise it from you.

Shirley

February 10th, 2015

Subject: I love you

Jason,

I don't know if you're checking your email or not. I heard about your surgery and how it's likely cancer and how it's likely bad. I just left a message on your voicemail. I called the nurses station at the hospital too, but they said they couldn't connect me since I'm not family.

I thought about telling them a thing or two about church family, but I worried that if I was pushy, they'd take it out on you, and I'm sure you're hard enough to handle as a patient as it is.

Anyways, I wanted you to know that I love you. I prayed for you tonight and for your wife and your beautiful boys.

Love,

Shirley.

February 5th, 2016

Subject: Cancer Buddies

Jason,

Who would have guessed that we'd end up getting cancer together at the same time? I'm down in Richmond now in a facility. It's nice and it's near Allen and Steve, but I miss my church. I hope that before I die, and I know I'm dying, you can come visit me. In the past, I would have been too vain to have anyone see me like this, but I don't care now. I guess that sounds like bragging, doesn't it? And that's a sort of vanity, too. Being Christian never really gets easier, does it? Have you seen those bumper stickers that say, “God's not a Republican?” Lord, I hope they're not wrong.

In Christ,

Shirley

In his inaugural lecture at Gettysburg Seminary, Robert Jenson began by asserting an axiom.

He writes:

“Humanity comes to exist in and out of the world of animals and plants and galaxies precisely when we realize that we do not yet exist. My humanity is not a set of characteristics which I may be counted on to exemplify: like being vertebrate or brown-haired or sapient. My humanity is rather something that happens. Our humanity happens as we become something that we were not before.”

We become human; we’re not born human.

At this juncture in the Gospel of John, Jesus has already multiplied loaves and fish. From the get-go of the Gospel, Jesus turned over two thousand glasses of water into top shelf wine for drunk people to drink.

Restoring sight to a man born blind?

No big deal. Not much of a feat.

What is a miracle— what is proof of everything the gospel promises— is that, simply as a product of his interactions with Jesus, the blind man’s neighbors, who have known him his whole life long, no longer see him.Jesus has made the man born blind unrecognizable!“Is this not the man who used to sit and beg?”

“No, but he is like him.”

December 11th, 2014

Subject: Church Directory

Jason,

You probably know I'm volunteering to help with the pictorial directory for the church. How are you doing? Are you okay? The reason I ask is because I was looking at your picture in the old directory and your picture in the new directory and you look like you've gained a lot of weight. Especially in your face. Like a little baby angel.

Ha!

There was a time when I probably would have said that to you differently without even thinking about how mean it would sound.

I like to think I'm different than I was. I wonder if my husband Paul would even recognize me now. Does it sound strange if I say, I hope not?

I love you,

Shirley

Christ is risen indeed.

So come to the table.

Because someone might need to be able to point to you as evidence that Jesus is the Way and the Life and Truth.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 7, 2025

My Son's Labor as Christian Vocation

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Today my youngest son Gabriel graduates from Army Basic Training at Ft. Jackson, South Carolina. He surprised us with the decision this winter. Tomorrow he heads to Fort Sam Houston in Texas for eighteen weeks of training to be a combat medic.

Earlier this summer, when Fleming Rutledge inquired about my boys and I shared how they both planned to serve in the Army, she immediately responded:

“You must be so proud of them!”I am.

Thoroughly.

Fleming’s response, however, made me realize just how few other clergy colleagues responded with a similar affirmation. Todd Littleton is another such friend. In fact, most reacted in ways that implied I was a poor parent— as though Gabriel is not an adult capable of making his own decisions. Maybe folks are surprised at my sons’ paths because I have such a large online footprint associating me with the theologian Stanely Hauerwas, perhaps the most notable advocate of Christian nonviolence.

On the one hand, I think such a response depends upon a selective reading of Stanley.

On the other hand, I believe Stanley’s espousal of nonviolence to be insufficient to the demands of the gospel and its implications for Christian vocation.

To read Stanley is to be reminded—rightly—of the scandal of the gospel. The kingdom of God is not commensurate with the kingdoms of this world. The church is neither a nation among nations nor identifiable with any of them. The crucified Christ is not Caesar. These are essential reminders in a world that regularly confuses faith with flag and martyrdom with militarism.

(That we live in a time when the once and again president and his enablers eschew honor and virtue, patriotism and international allies, leads me to think many of Hauerwas’ critiques of America no longer hold water. There is a place for Christian patriotism and a Christian defense of political liberalism. Indeed he has confessed his failure to appreciate liberalism as a means to secure relative peace. What presents itself as “Christian Nationalism” is idolatry. It’s antidote is not what Mainline Christianity so often serves up— a haughty, too cool cynicism— but Christian care of the public square.)

For all their prophetic clarity, proponents of Christian pacifism, like Stanley Hauerwas and Brian Zahnd, too often flatten the Christian moral imagination into a single ethical posture: refusal. Nonviolence, for them, is not merely a witness to the coming kingdom but the only permissible Christian response to evil in the here and now. Anything else, they suggest, is idolatry.

The problem with this position is not that it takes the cross too seriously, but that it fails to take creation seriously enough.

It assumes a world already redeemed, rather than one still groaning in Easter’s labor pains. It confuses the eschatological sign with the eschatological reality. It forgets, as my teachers Robert Jenson and David Bentley Hart both insist, that God’s love is not merely passive or poetic, but active, providential, and at times—yes—militant.

Military service, then, need not represent the uncritical acceptance of violence or a sanctification of nationalism, but a tragically necessary vocation within God’s ongoing war against chaos and injustice. There is, Jenson and Hart both argue, a choice other than the compromised realism of Reinhold Niebuhr and the disengaged pacifism of Hauerwas, one that instead recovers a more ancient claim: just war, rightly understood, is a work of charity.

Modern Christian ethics tends to reduce its options to two familiar poles: pacifism and realism. American Christian ethics treat the Christian pacifism of the sort one associates with, say, John Howard Yoder, and the so-called Christian realism of Reinhold Niebuhr and his disciples as the only available options for Christian moralists. Both claim to speak from a posture of humility before the gospel. Both, however, proceed from the same premise: that war is by its very nature evil.

Whether the response is to withdraw in nonviolence or to engage while confessing tragic compromise, the result is the same. The Christian never has any choice in times of war but to collaborate with evil; he must either allow the violence of an aggressor to prevail or employ inherently wicked methods to assure that it does not. What neither approach considers is that war may sometimes be waged virtuously, not because it is good in itself, but because the good—justice, order, peace—sometimes demands the sword.

The Christian tradition has long held this to be true.

For both Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, the use of force is not categorically sinful; it is morally intelligible when exercised in love.

Charity is not always gentle.

As Augustine taught, love of neighbor may require the suppression of injustice; to refuse to protect the weak from the violent is not sanctity but a failure of love. For Aquinas, because all human loves must be ordered within the love of God, “an unjust peace is not pleasing to God,” and thus, the love of political community must always be subordinated to the love of divine justice.

It follows, then, that war is not always the tragic choice of the lesser of two evils—for Christians are forbidden to choose evil at all. Rather, when it is waged on behalf of justice and by just means, it is a positive good, a work of virtue, and an act of charity.”

My friendship with Rabbi Joseph Edelheit, made in these days after and months after the 10/7 atrocity, has helped me to see how much of Hauerwas’ arguments for Christian nonviolence rely upon an almost Marcionite refusal of Jesus’ own scriptures. After all, the Decalogue’s command is not a prohibition against killing but a disavowal of murder. “The Lord is a man of war,” declares Exodus 15:3. In Canon and Creed, Robert Jenson insists that this confession “is not an archaism to be apologized for,” but a fundamental witness to God’s relation to the world. The simple fact is that the present groaning creation is one of violence and injustice. If the LORD is to be both the author of our history and an actor within it, there is no way for him to be so involved with us but as the God who takes sides.

For Jenson, this is not metaphorical.

It plays out in the lives of nations, in the contest between justice and injustice, in the struggle to protect the vulnerable. It is carried out, not only by angels and apostles, but also by those whom the scriptures call “the servants of God”—magistrates, judges, even soldiers.

Jenson is quick to distinguish between the church and the state:

“Entire renunciation of violence is the calling of the church herself and doubtless also of certain individual believers. But it can never be the calling of all historical agents, nor can God’s actual creation occur without those ‘who bear the sword.’” The church is a foretaste of the peace to come; it cannot abolish the world’s need for order in the meantime.”

— Commentary on Ezekiel

The insufficiency of pacifism comes into sharpest focus in the face of real historical evil. In The Beauty of the Infinite, David Bentley Hart turns to the Holocaust as a searing case in point.

He writes:

“The Holocaust was not merely the collapse of moral reasoning but the eruption of an abyss whose horror can never be circumscribed by any conceivable economy of meaning. In such a world, any theology that shrinks from confronting atrocity fails both morally and metaphysically.”

Hart does not celebrate violence; in fact, he is one of its most eloquent critics. But he refuses the idealist fantasy that sees martyrdom or withdrawal as a sufficient response to evil.

As he puts it:

“The refusal to oppose evil with force may itself become a complicity with evil. The notion that a peaceable withdrawal into martyrdom is always a sufficient response to atrocity founders at the gates of Auschwitz. The world is not yet reconciled. The resurrection has revealed the final Word, but it has not silenced every scream. Until then, the labor of restraining evil, even by force, may be itself a work of charity.”

The refusal to oppose evil with force may itself become a complicity with evil.

None of this romanticizes soldiering. The vocation of arms is neither salvific nor simple. It is, at best, a vocation of tragic faithfulness—an act of stewardship within a disordered world.

Jenson captures the tension:

The soldier’s labor is not eschatological, but neither is it godless.“The resurrection does not abolish the world’s tragedy; it renders it penultimate.”

It belongs to the old aeon still groaning for redemption, and yet, like every penultimate thing preserved in God’s providence, it can be taken up in love. If we go forth to fight for God’s justice, we do so as citizens of a Kingdom not of this world, one that can make use of the post-Christian state, but that cannot share its purposes. This is not merely nationalism in ecclesial dress. It is a call to a kind of chivalry—an obedience not to Caesar but to the One who will, in the end, judge the nations with justice.

The Christian calling is peace. But the Christian calling is also justice. These are not opposites.In a fallen world, peace that ignores injustice is not peace at all. In this world between the times, we may yet need those who wield the sword—not out of hatred, but out of love.

Yes, Christ tells us to turn the other cheek. And indeed, it is one thing to turn the other cheek against insult and casual abuse, or even to accept martyrdom, but another thing altogether to permit oneself simply to be murdered to no good end. Charity demands that love of self be ordered toward the love of God—and that the defense of one’s neighbor, and sometimes even of oneself, may be among the highest forms of that love.

The tragic is the faithful.

There will come a day when the swords are beaten into plowshares. But that day has not yet come. Until then, “between the times,” as Jenson puts it, “the tragic is the faithful.” And faithfulness, in such times, may sometimes wear a uniform.

To return to my original point, it is why I am very proud of my son.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 6, 2025

More Anon...

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here is a recent article in the Living Church, the magazine of the Episcopal Church, by Porter Taylor about the recent event honoring Fleming Rutledge at which I had the honor to be one of the speakers.

Here, Porter details the forthcoming festschrift volume for Fleming to which I am a contributor, More Anon….

Stories matter. But they matter not so much because they happened exactly in the way they are told—or at all—but rather because we believe the stories and they in turn shape our sense of the characters.

In 2008, at the age of 71, Fleming Rutledge went to Wycliffe College as a scholar in residence while (now) Bishop George Sumner was still the principal. One of her early appearances was in a homiletics class. After a student preached, Fleming was invited to offer feedback. She paused, considered, and then delivered her verdict:

“Honey, I’m not sure what that was, but it wasn’t a Christian sermon.”

By then, of course, Rutledge had already written multiple books, been ordained for over three decades, and preached around the world. But this story became part of her mythos.

On June 12, I had the pleasure of co-organizing a conference in Fleming’s honor. It wasn’t a farewell. It was a festival.

The purpose of the occasion was threefold: to celebrate the 50th anniversary of her ordination, to announce a fundraising campaign toward a new Fleming Rutledge Chair in Biblical Theology, and to unveil a writing project in her honor. By the end of our first day—well past 9 p.m.—Fleming was just getting warmed up.

During one of the Q&A sessions, someone asked about that “honey” story. Was it true? Did it happen? Fleming retold the tale with her signature Tidewater drawl, crafting each phrase with care. Then, after the punch line, she added with a perfectly timed deadpan:

“I never called her honey.”

The room erupted. The story was true—even if it had been sweetened for effect.

That moment crystallized what so many of us have long felt. Whether among bishops or seminarians, laity or theologians, she draws us in with wit, precision, and a hard-earned authority born of deep conviction.

It began for me the day Fleming slid into my DMs.

Like many others, I had known her through her books—especially The Crucifixion. At the suggestion of my brilliant and wise wife, I had written a liturgy for anyone to use during the pandemic. Months after the liturgy was released into the wild, I was on the platform formerly known as Twitter one day when I saw the notification: Message from Fleming Rutledge.

Thus began a correspondence that shaped my ministry—pastoral, practical, and preaching—in ways I’m still discovering. Over time, the DMs became emails, then phone calls. Eventually, I summoned the nerve and asked her to be my preaching mentor. She said yes.

And in true Fleming fashion, she connected me not only to herself but to others: Jason Byassee, Andrew Kryzak, Kristen Deede Johnson, Justin Crisp. Together we dreamed up a conference. We all had our individual reasons for celebrating her, but we wanted to put something together that demonstrated her vast and varied reach. Justin Crisp, our gracious conference host, dubbed it FlemFest.

Fleming also led me to Amy Peeler. I had long felt that Fleming’s ministry needed to be celebrated in writing. I knew that her influence was more popular outside of her Episcopal tribe. I was aware that she continued to shape the hearts and minds of preachers and pastors across the land.

Dr. Peeler and I began collaborating, envisioning what would become the volume we are co-editing to be published by Eerdmans in 2027: More Anon: Essays in Honor of Fleming Rutledge.

This volume will mark the 50th anniversary of her priestly ordination. It will include 22 essays from voices across the Christian landscape: Anglican, Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic. The contributors come from pulpits and seminaries, from classrooms and pressrooms. Stanley Hauerwas, Will Willimon, Kate Sonderegger, Russell Moore, Joy J. Moore, and others are sharing their work in this volume.

The title takes its cue from Fleming. The first time she signed an email to me “More anon,” I knew it was a phrase to which I would return. It speaks not only of continuation, but of confidence—there’s more to say, and I’ll be saying it. That’s exactly what this book embodies: a chorus of voices echoing hers.

At the conference, she sat front and center—surrounded by friends, her beloved husband, Dick, and multiple generations of Christian leaders who owe her a great debt.

Through her books, sermons, and lectures, Fleming Rutledge has shaped a generation of preachers, theologians, and laypeople. She writes with theological depth and prophetic clarity, bridging the pulpit and the page with unmatched conviction. Her sermons are thunderclaps of grace—fierce, faithful, and always grounded in the cross of Christ.

She has given the church a language for hope in the face of despair and a grammar for grace in a world of judgment. Her influence echoes from Episcopal pulpits to evangelical classrooms, from mainline pews to Reformed seminaries. In a time of shallow spirituality, she has insisted on the God who acts, judges, delivers, and saves.

And perhaps most of all: she has never stopped taking the gospel seriously.

And neither did we, not for a single moment of FlemFest.

My wife, Rebecca, and I were there, along with our 13-year-old son, Jet. Fleming, naturally, was smitten with him. She took him under her wing, signing a book at his request, conversing with him like the two were old friends. I pray it is a memory he will cherish forever. As proud parents, I know we will. After one of the presentations—by a highly regarded theologian—Jet turned to us and said, “That was pretty elementary.” You could almost hear “honey” at the end of his sentence.

That’s the kind of conference it was: theologically thick but unpretentious, sharp but never stuffy, reverent and deeply fun.

We were blessed by the presenters. Andrew McGowan brought his characteristic blend of historical depth and liturgical insight. Kate Sonderegger wrapped us in doctrinal richness that demanded silence. Jason Byassee wove wit and wisdom together with pastoral ease. And Jason Micheli preached the cross with all the defiant joy of someone who has staked his life on it. Each of these four presentations will be included in the volume.

Through the panels and the fortifying coffee breaks, we explored Fleming’s Christology, her apocalyptic imagination, her insistence on the priority of preaching, her focus on the subject of the verbs, and her refusal to tame the gospel.

There was also Evensong—a liturgy shot through with the glory of the cross. I had the humbling joy of preaching, looking out across a room filled with family, friends, and mentors—not least of all, Fleming herself with Dick by her side. The liturgy wrapped words in beauty, the music lifted our theology into doxology.

It was, in the end, not just a conference. It was a gathering of witnesses—people who had been changed by Fleming’s words, who had found courage through her conviction in the gospel of Christ.

And while she was honored she always redirected the admiration. Before the end of the evening, Fleming told us the rest of the story. You see, I was wrong. The legend did not begin with “honey” in 2008. It started one evening after she and Dick put the girls to bed. As they settled down for the evening, Fleming said, “Dick, I want to go to seminary.” This was not part of their plan; they had young children; none of this made logical sense to her. But without hesitation, Dick said yes. Through all the years of ministry, writing, and teaching, it is Dick who constantly supported her, who saw a way when there was no way.

Fleming Rutledge has taught us to preach as if lives depend on it. Because they do.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 5, 2025

"Christ is the Word and Not a Stone"

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here’s the reading for next week:

Bonhoeffer Reading 21.21MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

August 4, 2025

God is Not an Accessory to Our Lives

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Our Monday Night Live sessions will continue this evening with our second study of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s “Lectures on Christology.”

We’re covering pages 315-325 if you would like to join us. If you’re a subscriber here, then you’ll get an email notification just before we go live tonight. Here is a PDF of the reading:

202507230900045552.75MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadAs I mentioned last week, the lectures are a bit more dense than I recalled from my last reading of them. So here is a brief attempt at a summary to help those tackling the texts with us.

The key point to glean from the initial lecture is Bonhoeffer’s insistence that Christian faith centers on a person.

This is not as obvious as it sounds.

For many, Christianity easily devolves into a set of beliefs to which we assent or a list of moral commands which we obey. Still others view Jesus as in some way a mediator between God and humanity. But for Bonhoeffer, Christian faith is not first about doctrines or ethics; it is about a person. At the center of everything— literally, all reality— stands Jesus Christ. He is neither a distant historical figure nor a lofty ideal; he is the living, present God-man who encounters us here and now and demands a response from us.

The person is the Word.

Like Barth before him, Bonhoeffer emphasizes that Jesus is the reality that God addresses us— Barth calls this revelation. In other words, Christ is not merely an idea to be discussed or a doctrine to be believed. He is not an item of the past the events around which bear import for us in the present. Jesus is a spoken Word that happens between persons, a Word that calls each of us into relationship and responsibility.

Thus, when one person gospels another person or when the church proclaims the gospel, it is not simply telling stories about Jesus—it is Christ himself who speaks. Bonhoeffer calls this the poverty and richness of the church: it is poverty because Christ entrusts his Word to human voices, and it is richness because through such meager vessels, the living Christ is truly present.

This is why Bonhoeffer’s lectures begin with an unsubtle dig at generic spirituality. The true God— the God who is God, as Barth says— cannot be found through humanly derived practices.

The true God can only be discovered by him finding us.Just so, Bonhoeffer calls us to an encounter called the Word. Christ’s Word confronts us, claims us, and calls for a response. In the Word, we encounter not an idea but a person.

Importantly, encounter with the Word is not limited to words alone.

In good Protestant fashion, Bonhoeffer emphasizes the gospel promise that Christ comes to us in bodily form through the sacraments, particularly the Eucharist.

The sacrament is not a mere symbol!Just as Christ gives himself to us in the gospel, he clothes himself in bread and wine. The gospel word attaches itself to the tangible means. Therefore, it is the real presence of the God-man, given for us in humiliated form—in ordinary bread and wine.

Robert Jenson extends this point in On Thinking the Human, arguing that what prevents our relationship with God from being like that of a slave under a master is that God is not just a subject over us.

In bread and wine, God makes himself an object in our hands.

For Bonhoeffer, the refusal to hold a high view of the sacraments is a failure to affirm the incarnation in all its radically. God does not meet us in glorious abstractions but in the physical, the touchable, the edible.

And when it comes to the sacraments, Bonhoeffer maintains his initial point from the start of the lecture. The proper question to ask is not how (How are bread and wine God?) but who.

Who is here in loaf and cup for you?That Christ is here for you makes all the difference.An abstract God being here in bread and wine would not be reliably good news.

And the Christ who is present in the sacrament is risen.

Hence the Eucharist is not a reminder of Jesus’ death, it is an encounter with the living Christ himself. As I say at the table every Sunday, “Christ is the host…” He comes to us in humility, feeding us with his very life.

The theme of poverty extends even further.

Christ takes form in yet another humble, humiliated manner: the church-community.Remember, Bonhoeffer delivered these lectures in Berlin in 1932-1933. His vision of the church is in no way sentimental. Nevertheless, Bonhoeffer insists that the church is not a voluntary association of like-minded believers. It is the body of Christ himself, not metaphorically but in reality.

The church is the place where Christ is present in the world.