Jason Micheli's Blog, page 61

October 27, 2023

Listen to Us!

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

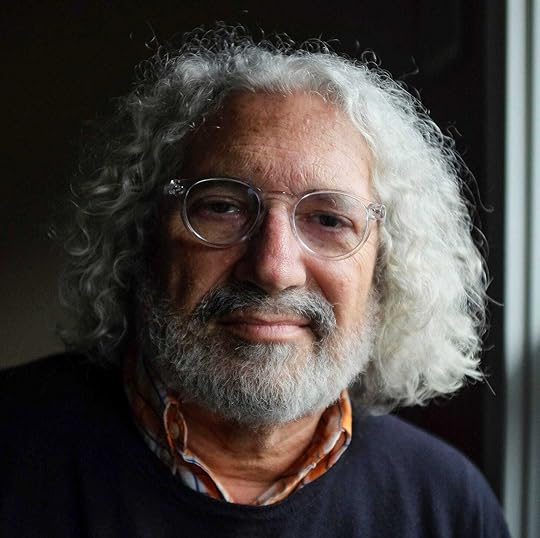

Here’s a video preview at an upcoming podcast episode with my new friend Rabbi Joseph Edelheit, who's promised to return several more times so we can learn from and listen to one another.

Rabbi Joseph joined Johanna and me to share his reflections as a Jew living in Diaspora on the 10/7 Hamas massacre. We discuss other matters but never wander far from today’s headlines.

Here’s a bit about Joseph:

50 Years in the Rabbinate: Rabbi Joseph A. Edelheit (C ’73) on the Unique Experiences of His Rabbinic Engagement:

When I thought about becoming a rabbi as an undergraduate at CAL Berkely in 1966, I could never have imagined the extraordinary experiences I would have. For fifty years, people have asked me to engage them, teach them, and sometimes lead and interpret a meaningful ritual in their life.

I have served three Reform congregations over thirty years in the Upper Midwest. where I learned what “windchill” meant. From the outset, the reality of interfaith couples and families became a central focus of my rabbinate. “Intro to Judaism” education and congregational programming have always been a significant concern.

Eventually regional and national rabbinic work about gerim/gerut provided me with an opportunity to be a leading advocate for Patrilineal Descent. University teaching became important, especially Jewish-Christian dialogue, which led to an opportunity to do doctoral work at the Divinity School of the University of Chicago.

HIV/AIDS emerged at a time when those who were among its first patients and deaths were alone and often rejected. I served this tragically unique community, which led to opportunities to lead in how Reform Judaism faced these challenges both in Chicago and nationally. Eventually my work was recognized, and I was asked to serve on President Bill Clinton’s Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS, 1996–2000.

I retired from my congregational rabbinate in 2001 because of challenges to my health, and I finished my doctoral work (DMin) at the University of Chicago in 2001.

A state university that settled a class-action lawsuit over antisemitism asked for my help. As part of the settlement, I created a program of campus and community engagement about Jewish culture. Eventually, I became tenured faculty, and retired as Emeritus Professor of Religious and Jewish Studies.

Though I tried to bracket my rabbinate at a state university, my pastoral role was called upon by students, faculty, and administration alike. My academic career required teaching about and interpreting Jews, Jewish life and texts, and Judaism to a campus and community of less than fifty Jews.

I helped to bring a unique symphony and choral Holocaust memorial program, “To Be Certain of the Dawn,” to the state university and a nearby Catholic university. We later took more than 250 students and faculty to France and Germany and performed it at Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp with survivors in the audience.

During this period, there was an opportunity in India to continue my HIV/AIDS work with multi-faith organizations who worked among infected children whose parents had died of AIDS. I participated in creating an international NGO that funded and provided service for sixty AIDS orphans in rural India who were all living with HIV/AIDS. Engaging people who had never met a Jew, but invited me to share a meal while sitting on the floor of their hut, added to my life commitment of pluralism.

My ongoing academic participation in the Society for Ricoeur Studies, is another unique experience of my rabbinate. I am the former student of Paul Ricoeur, who insists that philosophers and religious thinkers can and should engage in dialogue with a Jewish thinker.

My participation in conferences, took me to Rio de Janeiro in 2011 when I was invited to speak to a Reform congregation, ARI. Now eleven years later, that unexpected Shabbat invitation, led to exceptional personal love and another chapter of my rabbinic life, serving the World Union of Progressive Judaism. I volunteer for Brazilian communities who have no rabbi, and whenever asked, I teach at ARI where it all started.

During retirement I have written and edited two books with a third in preparation. The current crisis in antisemitism has added a new emphasis to my work in Jewish-Christian dialogue. I will co-teach a course at a Protestant seminary that deals with the challenges of preaching and teaching in response to antisemitism.

In 2021, the Divinity School of the University of Chicago, honored me as their alum of the year, the first time a rabbi has ever been awarded this recognition.

These fifty years were more meaningful because of the unconditional presence of my children. Still today, it is the love and respect of my family that I cherish the most.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 26, 2023

Luther and God's Two Words

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

This month marks the 506 anniversary of the preaching movement called the Protestant Reformation.

Importantly, a year after his hammer ignited the Reformation, Martin Luther wrote a disputation whose subtitle did not sound like an academic treatise, For the Inquiry into Truth: For the Comfort of Troubled Consciences. In the years just before he wrote the disputation, Luther had been “plagued” by “the two monsters” of the “power of the law” and “the sting of sin.” Rather than consolation for his troubled conscience, Luther suffered despair and deep anxiety, fear and “weary bones,” that caused him to cry out, “Is there any comfort— any hope?”

“Is there any comfort— any hope?”

Thanks be to God that Luther eventually discovered an unqualified “yes” to his anguished question. Commenting on Paul’s epistle to the Galatians, Luther writes:

“The distinction between the Law and the Gospel is a sure comfort…these words are the sermon which we should study daily…the sermon that speaks of, and as God’s word, accomplishes, both imprisonment and redemption, sin and forgiveness, wrath and grace, death and life.

Luther recalls elsewhere:

“I lacked nothing before this except that I made no distinction between the Law and the Gospel. I regarded both as one thing and said that there was no difference between Christ and Moses except time and perfection. But when I discovered the proper distinction, that the Law is one thing and the Gospel is another, I broke through.”

In order for us to appreciate the healing vocation that is gospel proclamation, it makes all the difference to see that Luther conjugated both Law and Gospel in the present tense.

Luther didn’t say the Law was one thing and the Gospel is another. It’s not a Before and After.They both are.

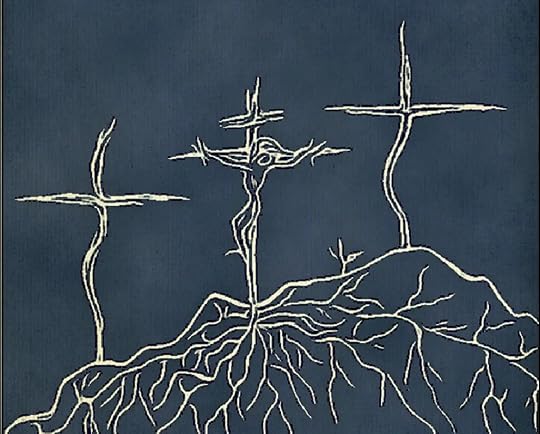

Paul proclaims in his letters that the Law has come to an end in Jesus Christ. The law until Christ, Paul says. Jesus has forever removed the curse of the Law, he writes in Galatians, by bearing the curse in his body upon the tree. Paul is not alone in this regard. The entire New Testament is unanimous that the cross is the hinge of history, the turning of the ages, from the old aeon of Sin and Death to the new aeon that only now awaits the second advent.

Luther’s great insight, however, is that when it comes to the Gospel of grace, we’re like the man Jesus heals in the Gospel. No longer blind, we see people but they look like trees, walking. That is, the fulfillment of the Law by Jesus Christ was an event, actual, in history. It happened, between noon and three, on a Passover Friday in 33 AD, a fifteen minute walk outside the city. “Around tea time,” as Monty Python puts it.

The overcoming and annulment of the Law’s accusation took place in history, yet Luther understood that it is not experienced by us as behind us in the past.

We experience the Law just as accusing today as it was yesterday.It’s critical that Luther does not refer to Law and Gospel as epochs.They are more than two times.They are words.They are words whereby God enacts God’s healing works. The Law still speaks in the present, and thus threatens the future, because God still speaks through the scriptures. Law and Gospel are Both/And not simply Before and After.

They are not historical epochs. They are states of existence.The Law speaks still as scripture thus it still accuses us, keeps diagnosing sin, persists in imprisoning us in our trespasses; consequently, we need Christ to have done more than silence the Law in the past on Golgotha and we need Christ to do more than come again and kick-off a glad future that Robert Capon compares to “Miller Time.” We need Christ to come to us in the present and create the reality that corresponds to the Gospel word.

“What other time does the Church have in which to live but the time of advent, the time of waiting,” Karl Barth asks rhetorically in the Church Dogmatics. Luther, however, intensifies the stress on advent. For Luther, advent is not only once for all, it is again and again.

Advent is not only once for all, it is again and again.

The Law was but the Law still is until Christ.Advent names the first and second comings of Christ, past and future, but it also names for Luther what half-blind believers experience spiritually and personally every day because we are made aware every day that we have many character flaws.

It’s not just human history that is divided into the two times of cross and resurrection. The human heart is so divided as well and logically then always stands in need of the One who is “the dispenser of grace, the savior, the joy and sweetness of a trembling and troubled heart…nothing but sheer, infinite mercy, which gives and is given.”

I’m going to repeat that point because I think it’s a post-it note every pastor should stick somewhere they will see it every Sunday morning. The human heart always stands in need of the One who is “the dispenser of grace.”

In other words, daily do we need a do-over. And the way Christ restores our sight to the time of the Gospel is by “proclaiming the day that divides history.”

But to take the day that divides history for granted, to assume the Gospel, to make something other than the main thing the main thing is to aid and abet the Accuser who is ever afoot to addict you once again to the false comfort of merit and demerit.

Where the Gospel is assumed, the Gospel is lost because the Law still speaks.Apart from the unceasing promise of the day that divides history, the astonishing gift recedes into your past and your once joyous heart trembles still more with unabated troubles.

If the Law was but the Law still is, if the Gospel we somehow believed on Monday morning has grown fuzzy and out of focus by Friday, then this means that whatever is the preacher’s text for Sunday you must speak a word of promise through it. Even if the word with which you’re working for Sunday is straight-up, undiluted, 100 Proof Law, it must also speak Gospel.

Every word must speak God’s two words.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 25, 2023

The Norm which Norms and is Not Normed

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

In light of Reformation Sunday, we will offer a short series of discussions on the five Solas which have served as a shorthand slogan for the chief concerns of the Protestant movement.

To kick things off, we discussed the most widely cited of the Solas, Sola Scripture.

Sola Scriptura = Scripture Alone

"There was no New Testament for the first 150 years of the church; thus the rule that the writings there collected are authoritative for the life of the church is itself a pure piece of churchly tradition. The use of sola scriptura to enforce "not tradition" is thus a mere oxymoron and fosters the delusion that we could ignore the centuries of theological reflection and debate that actually join us to the primal church without the loss of scripture itself. The church received the New Testament as a controlling part of her tradition, not as a substitute for it."

— Robert Jenson

Next Monday, we will talk about Sola Fide, faith alone.

To join us, click HERE.

If you have any questions or feedback, drop them in the comments below or shoot me an email.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 24, 2023

David’s Lord Always; David’s Son in Time

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Matthew 22.34-46

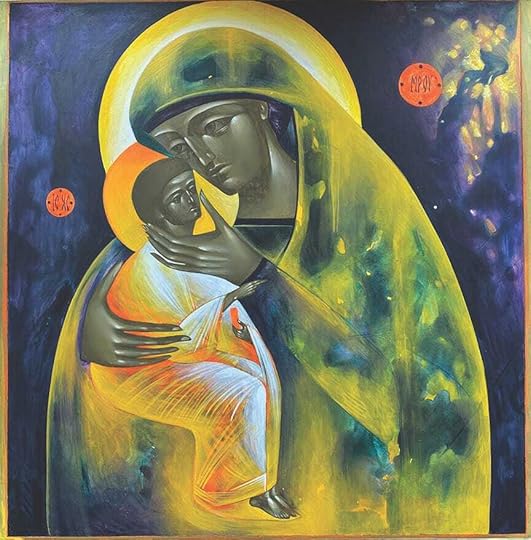

Cliches aside, it’s straightforwardly not the teaching of the scriptures that God’s too big to be put in a box. Rather, God has chosen the smallest of all possible boxes— Mary’s womb— to place himself.

Until we can answer Jesus’s question (“Who do you say that I am?”) none of the questions we ask about God can answer what God wants us to know.

“Hang on,” Jesus says to us in Sunday’s lectionary Gospel, “I’ve got a question for you. What do you think about the Messiah? Who’s son is he?”Here in Matthew’s Gospel, we’re in the temple— we’re at church— with Jesus, and for some thirty verses we’ve been assaulting poor Jesus with the kinds of questions imaginative sinners like us ask.

How do you feel about the current administration, Jesus? We didn’t vote for him. Should we pay taxes to that lying, conniving grifter?

How about heaven, Jesus— what’s it like beyond those pearly gates? Let’s say I married my brother’s widow. Who’s wife is she going to be in the kingdom?

Give us some homework, Jesus, some marching orders. Of all the oughts and shoulds in scripture, Jesus, what do you think is the greatest?

And Jesus answers so hastily it’s almost as though he’s bored by us or he thinks the things we think are important are beside the point.

“Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and render unto God what is God’s!”

“Why are you bothering to speculate about heaven? God is the God of the living not the dead.”

“And why are you asking me about the most important ought? It’s already in your Bible, people. Deuteronomy 6: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart…”

And then Jesus goes on the offensive before we have a chance to make a break for the coffee hour, “Now, let me ask a question of you.”“What do you think about the Christ? Who’s son is he?”And we all stare down at the sanctuary carpet unsure if this is a trick question or just a stupid one.

“Uh, that’s an easy one, Jesus. Don’t you remember the palm branches from the other day? ‘Hosanna to the son of David.’”

“Really?” Jesus replies, “You think so? Is that your final answer?”

And we all look across the pews to check with each other before we nod our agreement.

“Well then, you tell me,” Jesus says, hopping up and pulling a pew Bible out of the rack, “How is it that David, when he’s caught up in the Holy Spirit, calls the messiah, Lord?”“Yahweh says to my Adonai,” says Psalm 110, “The Lord says to my Lord, sit at my right hand until I make your enemies your footstool.”

“If the messiah is just another ordinary mortal like David, then why the heck did David call him Lord? And what’s he doing sitting in glory at the right hand of the Lord— a place, scripture’s clear, no creature can sit?

“I am the Lord, that is my name;” God says to the prophet Isaiah, “my glory I give to no other, nor my praise to idols.”

“Remember Moses,” Jesus adds, “Moses came closer than anyone to the glory of God, up on Mt. Sinai, and it so marred him— transfigured him— that Moses had to wear a veil over his face for the rest of his life.”

Only God can abide in the glory of God and by it be not consumed.

“Jesus Christ is the name of God,” says Karl Barth, “Otherwise, do we really have anything to talk about other than ourselves when we claim to be talking about God?”

Jesus Christ, the one who lived briefly, died violently, and rose unexpectedly is God. That’s the claim Christians make about the world, and today Jesus tells us that that claim is more important and far more interesting than any of the questions we like to bring to God.

“How can a son be lord of father?” St. Augustine asked, preaching on Sunday’s text in the fourth century.

Augustine’s answer:

“Jesus is great David’s greater Son: David’s lord always; David’s son in time.”

Augustine continued:

“David’s Lord, born of the substance of his Father, David’s son, born of the Virgin Mary, conceived by the Holy Ghost. Let us hold fast to both…He was made that which He made…Very Man, Very God; God and Man, whole Christ. This is the Christian faith.”

And this is why, though it’s doubtful Psalm 110, is your favorite psalm, it is the New Testament’s favorite psalm, quoted thirty-seven times.

Psalm 110 is the New Testament’s favorite psalm, quoted thirty-seven times.

It’s the only psalm to make it into the creeds. Charles Wesley had Psalm 110 in mind when he wrote his Christmas carol, “Veiled in flesh the Godhead see, Hail th’ incarnate Deity! Pleased as man with man to dwell, Jesus our Emmanuel.”

“So tell me again,” Jesus says to us, “What do you think about the messiah? Who’s son is he? Who do you say that I am?”

And Matthew reports not one of us had the chutzpah to “answer him a word nor from that day forward did anyone dare to ask Jesus any more questions.”

I wonder—

I wonder if they’re afraid because Jesus has just said, “I’m not just David’s son; I’m David’s God.

Or, are they afraid because Jesus has just told them that God has not come among them to answer their questions but to put his enemies under his footstool.Hang on, Jesus— enemies? I thought Jesus loved everybody, even Jim Jordan, so who are Jesus’s enemies? I thought Jesus was the friend of sinners, a first century Mr. Rogers, a Jewish Joel Osteen without the private jet.

Enemies?

October 23, 2023

What is Theology?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Early last week I discussed Advent and the Incarnation with my friend Will Willimon. The latter term names the biblical claim that the true God, the God of Israel, enters into time and space in Mary’s boy. The former term anticipates the Day when he will do so again. These are claims that are even more particular than they are peculiar. Meanwhile at the end of the week I traveled to Springfield, Missouri for a theology conference. Knowing that most of those who would gather with me— friends— have commitments and convictions other than my own (that is, I believe the term progressive Christian to be an oxymoron), I have been doing a bit of deconstruction myself.

Just so, the question: What is theology?If we refuse the philosophic a-priorism of the competing religions of Plato and the Enlightenment, a handful of axioms suggest themselves.

1. Theology is simply the thinking of the church in its service to its gospel message that Jesus lives with death behind him.Theology is the church’s maintenance of the particular evangel, Christ is risen. Because it’s a message, it must be conveyed from one person to another— a speaker must gospel someone. Theology therefore requires a community of tradition and interpretation, i.e., the church. Just as there is no salvation outside the church, there is no theology outside it. “Church” and “Theology” are as mutually determinative terms as “Gospel” and “Theology.”

Clearly, the gospel’s community has no way to copyright her labels for herself and her activity. Some may use the term gospel to describe an alien or variant message while others may purport to be doing theology with an object other than the God who raised Jesus from the dead but this is not theology as the church has defined her practice. As the ancient church has stipulated the rule: lex orandi, lex credendi. That is, our theology (lex credendi) conforms to our liturgy (lex orandi). Thus, what we say of and to God in prayer and praise and petition takes priority in our thinking about God.

Straightforwardly, then, theology cannot be done outside the church.

And because the church is the only proper place from which to do theology, theology can never start from the general, “God,” and move then move to the particular. Theology begins by saying “Jesus Christ.”

2. Theology is hermeneutical not speculative.

2. Theology is hermeneutical not speculative.Theology is an act of interpretation. As an act of interpretation, theology begins outside of myself, independent of my assumptions and convictions. Theology begins with a received word and issues a new word only on the basis of the old word.

Thus, theology requires that our metaphysics be accommodated to the biblical drama rather than, as happened in the modern era, the reverse.

3. Theology is a communal activity.

3. Theology is a communal activity.Hence, theology is a communal activity. One may deconstruct their received theology but one cannot detach oneself from Christ’s body and still be doing theology.

Theology is for proclamation.

And theology is with precisely those we wish Jesus had not called friends.

4. Theology is neither anthropology nor ethics.

4. Theology is neither anthropology nor ethics.Just as theology revises received philosophical assumptions in order to conform them to the biblical drama, theology (precisely because it is thinking about the message of the Incarnate God) must not make history subservient to being.

What the Greeks called “Ousia” (Being) is not in charge.

For example, early in its mission to transmit the gospel to the part of the ancient world shaped by the religion of Plato, the church hit up against that religion’s commitment to the notion that God is immune to time, incapable of pathos, and uncontainable in the finite world.

But the eternal God of the scriptures, who will be whosoever he will be, is manifestly not a god to whom time does not matter.

As Jewish theologian Peter Ochs notes, the effort to conform the biblical drama to antecedent philosophical assumptions displaces the God of history with the generic study of “religion.” Rather than maintenance of the message of God’s mighty acts in Israel and her servant Jesus, theology thus becomes anthropology and ethics.

This is how the gospel gets perverted into glawspel and Christianity reduced to the golden rule.

5. Theology is normed by the biblical drama.

5. Theology is normed by the biblical drama.Virtually every theological sin, says Gerhard Forde, and false formulation of the faith can be traced to the intrusion of the pagan notion of timelessness into the scene. Instead any onto-theological claims (e.g., “God does not act in history” or “God is not a human” or even “God does not wreak weal or create woe”) are derivative of what we already know about God. And we know God only by way of his revelation in historical time called the Old and New Testaments.

Scripture need not be “inerrant” or “infallible” to be nevertheless the means by which the true God identifies himself.

Thus, theology is normed by the biblical drama because we are capable of no true knowledge of God until God reveals himself to us in time and history. And the biblical drama is the memory of those incarnations.

6. Theology is trinitarian discourse.

6. Theology is trinitarian discourse.If theology is normed by the biblical drama, then, just so, theology is trinitarian discourse because God is a colloquy. God’s being is a being in history and this history is a story with a dramatis personnae— what the church father Gregory of Nyssa called God’s “temporal infinity.”

Once again, therefore, God’s being in history— scripture’s narrative of Father, Son, and Spirit— is not derivative to a priori convictions about God’s being. Contrary to all ontological foundationalisms, the true God is known only by self-revelation. And when the true God unveils himself fully, we discover the One is three person’d.

The biblical drama recounts the history by which God identifies himself— the happening of God.

As Gregory of Nyssa put it:

“The triune event is temporal infinity. God in Christ is infinite over the past and infinite over the future. The triune life is God of the past, the present, and the future.”

Thus—

Trinity is not a philosophic construction.

Trinity is a proper name.

Because trinity is a proper name, theology must be trinitarian discourse. A theology which speaks only of “God” in the general or abstract speaks of a god other than the Colloquy that is God.

Because God is triune, God’s identity is inseparable from the story of Israel and, thus, an abstracted, universal theology is an assault on the identity of God. Worse still, if God has not so entered into time and made himself an object in Mary’s arms or in Israel’s temple, neither can he be an object of our knowledge.

7. Theology has more than one audience.

7. Theology has more than one audience.(And one audience is more important than the other.)

Once again the lex orandi, lex credendi.

Theology is maintenance of the church’s message that the God of Israel has raised Jesus from the dead, having first raised the Jews from slavery in Egypt.

Directed outward to the world, this message is the stuff of promise. But the world is not the only hearer to whom we speak— the world is not even primarily the listener we address with gospel. In Jesus Christ, God the Son makes his Father our Father too. We’re invited into the Colloquy that is God.

Directed to the world, the gospel is promise.

Directed to God, the gospel is prayer and praise and petition.

Theology that is not firstly in service to prayer is not theology.Just so, a theology so deconstructed that prayer no longer does anything, theology that posits a God who is no longer persuadable, is a theology unmoored from the ancient rule, lex orandi, lex credendi.

As Robert Jenson writes:

“When the universal rule from prayer is not followed, theology slips from its object, for it is in the church’s prayer and praise, in their verbal form and in the obtrusively embodied form called sacrifice, that the church’s discourse turns and fastens itself to God as its object. And it is the ineluctably trinitarian pattern of the church’s prayer, its address to the one Jesus called Father, with Jesus who thus made himself the Son, in their common Spirit, by which the church’s discourse grasps the resurrection’s particular God as the object finally given to it.”

8. Theology is a listening as much as an utterance.

8. Theology is a listening as much as an utterance.Deconstructing conventional Christianity (Christianity accommodated to culture) is holy and good; it is the church reformed, always reforming.

Deconstructing— so as to detach from— traditional Christianity (the faith of the church fathers) is destructive; the deposit of the saints just is what God has said and done.

If God has not so said and done in the past, we have no reason other than sinful pride to suppose that God speaks or acts amongst us in the present.

In which case, there is no Future.

Therefore—

In theology, the golden rule and greatest commandment apply across the veil of death.

Love of neighbor includes our dead neighbors whom the church calls saints.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 22, 2023

The Progressive Spiral of Eternity

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Hi Friends,

Here is the final session of our exploration through the last book of the Bible. In this conversation we discussed chapters 19-22 of Revelation.

We’re done with the Apocalypse, but we’re not finished learning from one another and growing in the Spirit.

Heads Up!Given that this coming Sunday is Reformation Sunday, starting tomorrow night we will kick-off a short series dedicated to the five Solas of the Reformation:

Sola Scriptura

Sola Fide

Sola Gratia

Sola Christus

Soli Deo Gloria

The Solas are a shorthand slogan that captures the ethos and endeavor of Luther’s preaching movement; in that, the Solas provide Christians with the linguistic rules to ensure that they are always speaking gospel when they attempt to gospel another person.

How to join us:

You can join us live and ask questions at our Riverside Studio. Note, Riverside works best with Chrome or Edge as your browser. Here’s the link.

You can join the livestream at YouTube. Here’s the link.

You can find it here on Substack after Monday.

Back to our final session Revelation…

Here is the passage from Robert Jenson with which I began the session:

The result is that the canonical account of Ezekiel's vision is rather like Luke's account of the Christian mission. It lacks closure. And perhaps for a similar reason, the story is expected to continue. Indeed, the canonical Ezekiel's lack of a proper ending makes a decisive point about its content. Whatever story may be told about the final goal of God's way with us, it must not be told as the achievement of a thereafter static perfection. Had Ezekiel or his editors wrapped everything up neatly, they would have belied the story they had been telling about God. For the heaven of popular apprehension, where nothing more ever happens, is not a place into which the biblical God would or indeed could bring his people. Rather, whatever blessing we may in a particular context invoke to speak of the kingdom, we must imagine a sort of spiral of the granting and pursuit of that blessing. That is why throughout Christian history, Love has been the favored blessing by which to characterize the life of the kingdom. For love is the gift and goal that once given and achieved is both a completed work and each time a new beginning. Jonathan Edwards having in biblical fashion equated knowledge and love put it so. It seems to be quite a wrong notion of the happiness of heaven that it is in that manner unchangeable that it admits not of new joys. On the contrary, the saints will be progressive all eternity.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 18, 2023

Heaven and Earth

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Here’s a sneak peak at a forthcoming podcast episode with my friend and mentor, Will Willimon, about his new book Heaven and Earth.

Hamas’s massacre in Israel and Israel’s response in Gaza is a reminder to us that, as Karl Barth note…

October 17, 2023

Jesus's Pockets are Empty

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Matthew 22:15-22

Teacher, is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not?

In this Sunday’s lectionary Gospel passage, Jesus pointedly implies that the begrudgers’s question about taxes to Caesar and the law of God is a question that in itself violates the law of God. Jesus responds to their question about the commandments with another commandment, a commandment given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai, do not put the Lord your God to the test. The same commandment Jesus recites when tempted by the devil in the desert. In other words, our question to Jesus about Caesar's claim on our stuff makes us sound like Satan.

Asking Jesus what we should do about Caesar's claim on us makes us sound like Satan.“Teacher, is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not? But knowing their hypocrisy, Jesus said to them, why are you putting me to the test?”

Teacher, is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not?

Should we or shouldn't we, Jesus?

Yes or no?

The gospel story begins by telling you about a tax levied by Caesar Augustus to make the Jews pay for their own subjugation. And the gospel story ends with Pontius Pilate killing Jesus. On what charges? On the charges of claiming to be a rival king and telling his followers not to pay the tax to Caesar.

The tax in question was the Roman head tax levied for the privilege of being a Roman citizen.

Incidentally, this same tax is where we get the word gospel from in the first place. In ancient Rome, that word gospel referred to the announcement that Caesar had conquered you. And now, he was not just your salad, he was your god too and now you have the awesome privilege of paying taxes to cover the cost of his having colonized you.

The Roman head tax could only be paid with a silver denarius from the imperial mint. It's the only way it could be paid. The denarius was the equivalent of a quarter. Just a quarter. Less than a cup of coffee. So it's not that the tax was onerous, it was offensive.

On one side of the coin bore the image of the Emperor, Caesar Tiberius, and on the other side was the inscription, Caesar Tiberius, son of God, our great high priest. Carrying the coin broke the first and most fundamental law, you shall have no other gods before me.

And because it broke the law of God, the coin rendered anyone who carried it under God's wrath. The coin made anyone who carried it ritually unclean. Therefore, it couldn't be carried into the temple, which is why money changers set up shop on the temple grounds to profit off the Jews who needed to exchange currency before they worshiped or made an offering.

You see how the system works?

Teacher, is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not?

You see, what they're really asking here is about a whole lot more than taxes. But to see that, in order to see what they're really asking, you've got to dig deeper into the passage.

The scene takes place during Holy Week, on the Tuesday before the Friday that Jesus dies. On Sunday before this passage, Jesus rides into Jerusalem to a King's welcome. On Monday the day before this passage, Jesus cleanses the temple. Jesus pitches a temple tantrum, crashing over all the cash registers and the money changers and animal sellers and driving them from the temple grounds with a whip. And that's when they decide to kill Jesus. Why? To answer that question, you need to know a little history.

Two hundred years before this passage, Israel suffered under a different empire, a Greek one. And during that time, there was a guerrilla leader named Judas Maccabeus. He was known as the Sledgehammer.

The sledgehammer's father had commissioned him to quote, avenge the wrong done by our enemies, and pay attention, and pay back to the Gentiles what they deserve. So Judas the sledgehammer rode into Jerusalem with an army of followers to a king's welcome. He promised to bring a new kingdom. He symbolically cleansed the temple of Gentiles, and he told his followers not to pay taxes to their oppressors. Judas Maccabeus, the sledgehammer, got rid of the Greek kingdom only to turn around and sign a treaty with Rome.

The sledgehammer traded one kingdom for another just like it.

But not before he became the prototype for the kind of Messiah Israel expected. That was 200 years before today's passage. About twenty five years before today's passage when Jesus was just a kindergartner.

Twenty-five years before this passage, another Judas, this one named after that first sledgehammer, Judas the Galilean, called on Jews to refuse paying the Roman head tax. And with an armed band, Judas the Galilean rode into Jerusalem to shouts of what? Hosanna. Judas the Galilean cleansed the temple and then he declared that he was going to bring a new kingdom with God as their king. Judas the Galilean was executed by Rome.

You see what's going on?

Jesus the Galilean has been teaching about the kingdom for three years. He's just ridden into Jerusalem to a messiah's welcome. He's just cleansed the temple and driven out the money changers. The only thing left for Jesus, the sledgehammer, to do is to declare a revolution, to stand up to injustice, to deliver the oppressed, to cast down the principalities and powers from their thrones, to take up the sword.That's why the Pharisees and the Herodians trap Jesus with question about this tax.Jesus, do you want a revolution or not?That's the real question.Come down off the fence, Jesus.

October 16, 2023

The Hidden and the Clothed God

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

The Old Testament lectionary text for this coming Sunday is Exodus 33:12-23.

My friend Ken Jones has a relevant passage on Luther’s distinction between the Hidden God and the Preached God (or, God Naked and God Clothed in the gospel word) from his wonderful book.

The problem with philosophical proofs for God is that once you get yourself a provable God, it leaves way bigger questions standing there: If this God exists, how do you know who that God is? Is this God actually good? In the end, what will God’s judgment on you be?

All the questions and proofs force a difficult realization on you: using your senses and your rational mind, you can’t truly know anything about God’s existence, actions, or attitudes toward you.

And you wind up with my Twin Bed Theological Terrors.

If you try to suss it out by looking at the world around you, you might say you have found evidence in nature. The breathtaking beauty of a sunset, a rainbow, the variety of snowflakes and human faces, and the way harmony works in music—all these things show us both God’s existence and his goodness. You can add plenty more to the list from your own experience, from the taste of ripe strawberries, to rumbling thunder, to the twinkling of a field of stars on a summer’s night or that of your beloved’s eyes. Yet it is not hard to find other scientific explanations for all these things that say nothing at all about God.

What’s more, if you want to use beautiful and amazing things as proof of God’s existence or goodness, you also have to take with them all the bad things you see and experience in nature: natural disasters, cancer, the perils of toilet training, adolescent angst, and all those things insurance companies call “acts of God.”

Even if you could argue for God’s existence, when you add these things to the mix, it becomes hard to say whether God is even good. Luther said this was the greatest temptation.

Like Luther, you can get to the point where you say you “don’t know if God is the devil or the devil is God.”And in our game of divine Sardines, God remains tucked away in some inaccessible eternal nook. That is the exact confusion that crops up in the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden in Genesis 3. The temptation the serpent sets before the woman is not whether she and the man should eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Instead, the serpent asks whether they can trust God’s motives in commanding them to keep away from the tree and God’s judgment of death. The serpent says, “You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:4b–5).

Instead of trusting God to give them all that they needed for their creaturely existence, they turned to the serpent for its wisdom and to themselves as agents for concocting their future. They came to think that God was holding back something especially good. At best, they regarded God as their lackey and, at worst, their enemy. Thus our first parents and every generation after them have taken matters into their own hands. That’s what happens when God remains hidden behind the veil, when you can’t grasp what God is up to, and when the threats and temptations of this world move you to seek certainty. You scramble to cobble together something sure.

Luther knew something of such things when he wrote his explanation of the first article of the Apostles’ Creed in the Small Catechism in 1529:

I believe that God has created me together with all that exists. God has given me and still preserves my body and soul: eyes, ears, and all limbs and senses; reason and all mental faculties. In addition, God daily and abundantly provides shoes and clothing, food and drink, house and farm, spouse and children, fields, livestock, and all property—along with all the necessities and nourishment for this body and life. God protects me against all danger and shields and preserves me from all evil. And all this is done out of pure, fatherly, and divine goodness and mercy, without any merit or worthiness of mine at all!

This is nothing like the vast, terrifying power of a God who remains hidden. Luther came to know a God who is gracious, patient, and lavish in bestowing gifts. In fact, he argued that you could come to see God in creation, even in the hard facts of life and the terror of nature’s perils.

You could come to regard all these things as simple masks covering the face of God.In the Old Testament, seeing God without a mask is a dangerous thing.When Moses and God’s people were enslaved in Egypt and Pharaoh finally released them from bondage, they stood trapped at the sea with the Egyptian armies, with all their horses and charioteers, coming up behind them. God appeared behind the masks of a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. But when God gave the enemy armies a glimpse of divine might and glory, they were thrown into a panic. Their chariots were stuck, and people fled hither and yon—all from a wee glimpse behind the veil.

Later, when Moses was given the commandments on Mount Sinai, the mountain was clouded over, and the people below were protected from God’s nearness. When Moses said to God, “Show me your glory,” God said to Moses, “You cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live” (Exodus 33:18–20). Moses was instructed to hide in a crack in the face of the rock, and Moses had to wait until God said “when.” The most Moses was allowed to see was God’s back, but still, when he came down from the mountain, Moses had been physically changed: “The skin of his face shone because he had been talking with God” (Exodus 34:29).

Looking at the guy who had looked at God so spooked the Israelites that from that time forward, Moses took the clouded Mount Sinai as his model: he wore a veil over his head and only took it off when he went back to the summit to chat with the Lord.

The commandment-inscribed tablets that God gave Moses were placed in a golden ark, which was carried with the Israelites in their wilderness wanderings and in their conquest of the land God had promised them. The ark that contained these tablets that God’s own hand had touched was so holy and so dangerous that when the Israelites moved their encampment, only the priests could come close, and the rest of the people were instructed to stay 1,000 yards away from it (Joshua 3:4). Years later, when the ark was being moved on an oxcart, the holy crate began to slip. A man named Uzzah reached out to steady it, and—Zap! Learn your lesson, Uzzah!—he was struck dead on the spot. King David heard of these things and was afraid to have the ark anywhere near him (1 Chronicles 13:9–14). When the temple was finally built in Jerusalem, the ark was installed in a space with floor-to- ceiling curtains surrounding it. The space was called the Holy of Holies, another way of saying it was the holiest of spaces. Ever. No one was allowed to enter except the high priest, and he could only do it on the Day of Atonement.

In the 1981 Steven Spielberg blockbuster, Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nazi villains and the hero, Indiana Jones, are on a race to capture the Ark of the Covenant. The Nazis hope to harness its powers and use God as a weapon for Hitler and the Third Reich. At the climax of the movie, Indy and his companion Marion are themselves captured and bound while the Nazis intone the ancient words of the Israelite priests. As the villains lift the lid of the ark, Indy says, “Shut your eyes, Marion. Don’t look at it, no matter what happens.” The villains come to their end when the power and glory of God rise out of the ark and cause wholesale destruction: lightning-fried soldiers, melting faces, and exploding Nazi heads. But the protagonists are saved because they didn’t look or come near.

Of course, Raiders is a fiction, but in at least one way, it tells the truth.

Be careful about wanting to see an unhidden God.Even encountering God secondhand is dangerous stuff, and God will brook no attempts to get behind the veil. You won’t get to crawl into God’s hiding space and have other seekers cram in with you. The game of divine Sardines can’t end. You’re left to wander, grumpy and frustrated, and wonder what kind of God this is. You’ll say, “Hidden God? No thanks. I’ll stick with something I can see and trust.” And that’s where Article I of the Augsburg Confession is in your corner. By including the language of the Holy Trinity (the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit), Philip Melanchthon points to the places God wants to be encountered and where faith can actually see God. And it gets even more specific. The article speaks of who Jesus is: both completely divine and wholly human.

That means that in this person, Jesus of Nazareth, you have access to a God who is overflowing with loving kindness for broken and sinful human creatures.It means that God has determined to call everyone in from hiding, “Olly olly oxen free.” Or as Paul said in Galatians, “For freedom Christ has set us free”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 15, 2023

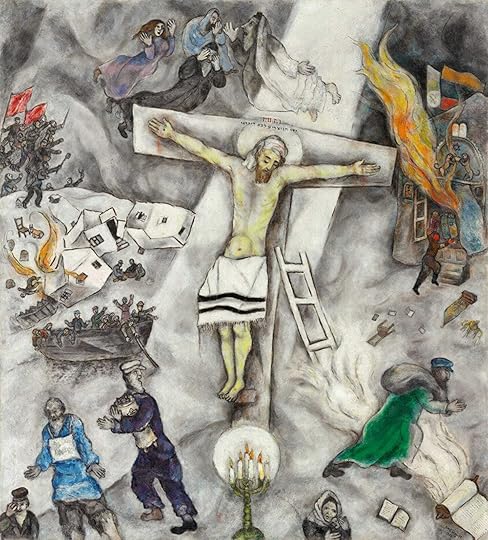

Salvation is from the Jews

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Revelation 15.1-8

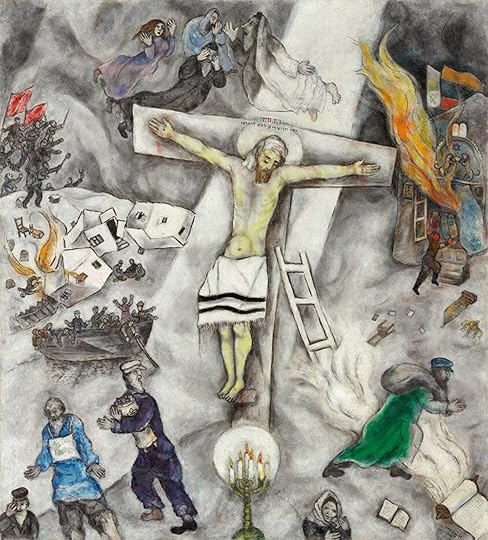

Two days after the 10/7 terrorist attack on Israel, I spoke with my friend Liel Liebowitz who is an Israeli journalist.

Words fail.

Not knowing what to say, I simply asked him a question.

“What have the last two days been like for you?”

Liel replied:

“You know, Jason, I am a ninth generation Israeli. I served in the Israeli Defense Force. I have endured many gun battles. I've survived several wars. I know from this, I'm no squish, but when I started receiving frantic phone calls from my family in Israel, unusual on a Shabbat morning, and I rushed to look at these horrendous images and I was shocked not only to see what was happening, but to see, in an unprecedented manner, these atrocities being live streamed on the internet, to see terrorists rushing into the home of an eighty-five year old woman, grabbing her phone, torturing and murdering her while filming their crimes on her own phone and then posting it to her own Facebook page so that her family would see their atrocities. Even after everything I saw during my years of service, this was a level of demonic barbarism that shocks me. To see Jews, once again, go like sheep to the slaughter, our babies like sheep to the slaughter— our horror, it’s indescribable.”

Though words fail to capture the indescribable, words are nonetheless necessary for Jews to remember (as they have always had to remember). Thus, Liel has begun a project for Tablet Magazine, archiving eyewitness testimonies from the Hamas massacre in Israel. I asked Liel to share some of the accounts he has documented.

He told me about the five star chefs in Tel Aviv who immediately turned their restaurant kitchens kosher so they could send food to the front lines.

He told me about the Jewish businessman at the El Al ticket counter at JFK in New York, who took out his credit card, held it up in the air, and announced to everyone in line, “This credit card has a cash limit of half a million dollars. Anyone who can show me a note from the Israeli army that he or she is going back to fight in this war, I will pay for your ticket right now.”

He told me about an elderly cab driver in southern Israel who was driving around Saturday morning when he came across a bunch teenagers running, covered in blood, hysterical, barefoot. “So the old man— he’s in his 70’s,” Liel told me, “he stops and picks them up in his cab and asks what had happened. And they tell him that they had been to this music festival when terrorists came. As the cab driver explained it to me, “Right then and there, I understood, I have to save as many of them as I could.”

And then Liel said to me:

After I listened to some of the stories Liel has collected, I asked my friend what Christians could do for Jews.“This old man drove around for over an hour under heavy gunfire, grenades, RPGs flying like right over his head, picking up as many kids as he could, cramming them into his cab. He saved something like thirty or forty lives.”

“Well,” he said, “I think it’s really very easy. It really is three simple things. The first is call a Jewish friend. The second thing you could do is double down on being great Christians: worship God, study his word, and commit yourselves to the teachings of our faith.”

After we stopped recording, I said to Liel, “You said there were three things we could do.”

“What’s that?” he asked.

“Three things— you said there were three things Christians can do but you only mentioned two of them.”

“And the third one is the most important one of all!” he exclaimed, “especially for clergy!”

“What is it?”

“Remind your people that salvation is of the Jews. Remind Christians that salvation is from the Jews.” If his was not a word from God, then this passage most surely is the word of God.And, notice, it bears the selfsame message.

If his was not a word from God, then this passage most surely is the word of God.And, notice, it bears the selfsame message.The Apocalypse is as much a book of sounds as signs. What the Spirit reveals to John are auditions as much as visions. Thus far, the Seer has encountered two signs. Now John beholds a third sign in heaven. But a sound also accompanies the sign.

The Spirit shows the prophet seven angels armed, like the angels of Exodus, with the wrath of God. Their plagues are the final plagues “because the anger of God is fulfilled in them.” However, before the Lord’s wrath is ended, in the midst of this third sign, the Seer hears another sound, a brief eruption of rejoicing.

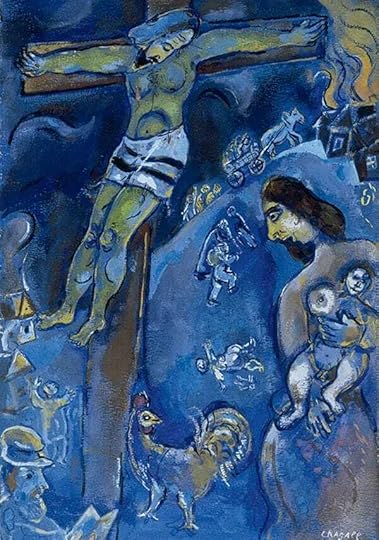

Much like the Israelites stood on the banks of the Red Sea and sang as the walls of water fell upon Pharaoh’s soldiers, John sees the company of heaven standing beside “a sea of glass mixed with fire” and singing about the coming judgment and deliverance of the Lord.

According to the prophet, the music in heaven is polyphonic.The beloved community praises God with two simultaneous melodies.The company of heaven sing the Song of the Lamb, a song which John heard previously:

”Worthy is the Lamb that was slaughtered to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!”

And those gathered around the Lamb also sing, says John, the Song of Moses:

“I will sing to the Lord, for he has triumphed gloriously;

horse and rider he has thrown into the sea.

The Lord is my strength and my might,

and he has become my salvation;

The Lord is a man of war;

the Lord is his name.”

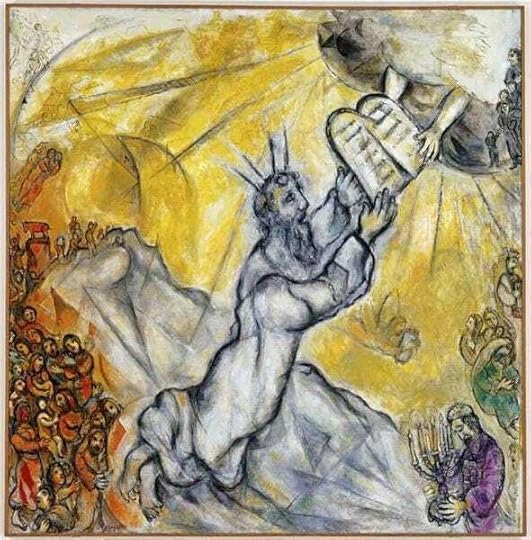

At the beginning of the Apocalypse, the prophet sees heaven’s throne surrounded by both the twelve apostles of the church and the twelve patriarchs of the people Israel. Now, in this third sign, John hears what he previously saw. Straightforwardly, John hears Christians and Jews together, in the Spirit, praising the God of Israel and the Lamb who is Israel’s Lord made flesh. Indeed that the Seer hears the Song of Moses first, that Israel’s song has priority, suggests that in the New Jerusalem the tribes of Israel will lead the church’s gentiles in praise of her Lord and study of his law.

On its face this is not surprising.

After all, the Lamb is himself one of the Israelites who sings the Song of Moses.“The End is music,” as Robert Jenson writes, but the music is polyphonic.

There are two simultaneous melodies.

The polyphony of the Last Future bears implications for the present day, for if the End revealed to the prophet John shows that the Fulfillment does not conclude God’s purposes with his people Israel, then neither are the Lord’s aims for them ended in the meantime.

Salvation still is of the Jews.

As the apostle Paul understood in his Epistle to the Romans, the promise was never:“I will be your God and some other people will be my people.”And therefore the question was never, “Are the Jews saved?”

The question is always, “Are we?”

On a Friday night in April almost thirty years ago, in the dining room of his family’s Nebraska home, Rabbi Michael Weisser opened his Haggadah and began to read the Passover script in Hebrew. As Moses had taught, the Passover that night in Nebraska began with the youngest child asking, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” And as always, Weisser gave the ritual response, commemorating the Jew's rescue from slavery. Rabbi Michael made no mention of the other factor that made this Passover night different from all other nights. Sitting at the table with Michael and his family and their friends was Larry Trapp, an ailing, near-blind diabetic who only recently had been an avowed Neo-Nazi and the Grand Dragon of the Lincoln Ku Klux Klan.

In 1991, Rabbi Weisser and his family moved from New York to Lincoln, Nebraska where he served as cantor and spiritual leader of the South Street Temple, the oldest Jewish congregation in Lincoln. One Sunday morning, only a few days after the rabbi and his family had moved into their new home, Larry Trapp phoned the rabbi and snarled an ugly, anonymous threat, “You’re going to be sorry you moved into that house, Jew boy.”

For Trapp, who was forty-two at the time, the call was just another message of a lifelong campaign of racial hatred.

“The Klan was power and community,” he says. “I loved it.”

Trapp worked for the Klan out of his home, harassing victims over the phone. No strangers to bigotry, the rabbi and his wife refused to be victims. The rabbi called the police, who quickly figured the perpetrator was Larry Trapp, who was known in the Lincoln community as a white supremacist.

Surprisingly, the rabbi decided to reach out to Larry. Every week, right before he taught Bar Mitzvah lessons, Rabbi Michael, would call Larry and leave a message on Larry’s answering machine.

“Larry,” he would tell Trapp, who had lost both legs to diabetes in 1988, “with your physical disabilities, the Nazis would have made you the first to go.”

Or, “Do you really want to face God with all this hatred, Larry? Let me help you.”

The rabbi kept at it.

He kept calling Larry for months.

“Why are you calling me? You are hassling me!” Larry griped, when he finally answered the phone one day.

“I just want to talk to you,” said Rabbi Michael.

“What do you want to talk about?”

And Rabbi Michael replied, “I hear you’re disabled, Larry, and I thought you might need a ride to the grocery.”

“For a minute there was this dead silence,” the rabbi said, “but then the tone of his voice completely changed. He said, ‘I’ve got that taken care of, but thanks for asking.”

As Larry Trapp later told the NY Times, “I could detect love in Michael’s voice. I had never heard love from a stranger before. I felt lonely.”

Rabbi Michael kept calling, week after week, month after month, leaving what the rabbi called “love notes” on Larry’s phone.

“Larry, there’s a lot of love out there and you’re not getting any of it.”

Finally, one evening in 1991, on the sabbath, Larry Trapp called the rabbi back.

As Rabbi Weisser recalls it, “Larry said, quote-unquote I’ll never forget it, it was like a chilling moment, in a good way. He said, “I want to get out of what I’m doing, and I don’t know how. Can you help me?””

When Larry opened the door to them, he was holding a gun. But Larry handed the gun to this rabbi, and then he invited them inside.

Stepping inside, the rabbi offered Larry his hand.

“It was like a jolt, an electrical current,” said Trapp, brushing away tears. “I looked down at my hands, at my two Swastika rings, and I took them off. I said, I can’t wear these anymore. They’re a sign of hatred.”

Inside Larry’s home, the three of them talked for over three hours. Not surprisingly, Larry told them about his childhood history of abuse. Before they finished, Larry wept and confessed to the rabbi, “I don’t want to be who I have been.”

Even more remarkable—

Larry wasn’t just disabled. Larry was sick, chronically so. His kidneys were failing. So, the rabbi and his wife decided to welcome Larry into their home and to take care of him. They invited him to sleep in the bed of the daughter whose life he’d once threatened. Rabbi Michael’s wife, Julie, gave up her job in order to be Larry’s full-time caregiver.

I have shared that story before as an illustration of grace; the rabbi did not regard the sinner according to merit and demerit.

But today I tell the story as the prose counterpart to the poetry the prophet hears in heaven. As with Larry Trapp so for all us gentiles.

The Last Future just is the sound of Jews welcoming us into their home to glorify the God of Israel and enjoy him forever.

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In the second century, a theologian named Marcion of Sinope argued vociferously that the God of Israel’s scriptures— allegedly violent and full of wrath— could not possibly be the Father of the Lord Jesus Christ. Marcion expunged the Old Testament and even redacted the New Testament to conform it to his convictions. Although the church quickly condemned Marcion as a heretic, going so far as to excommunicate him in 144, Marcionism has survived and often thrived in the church.

The ancient heresy abides in no small part because Christians neglect to consider “Israel’s place in that will of God which the church relies for her own meaning.” But Christians must have a theology of Israel because, as the Apocalypse makes clear, Judaism does not fall under the rubric of comparative religion.

The church can regard neither the old Israel of scripture nor contemporary Judaism as an other religion.For example, if a Jew wished to convert to Christianity and join the church, then he or she would be exempt from the renunciation formula in our baptismal liturgy exactly because he or she already had been worshiping the true God.

Christians can disagree about the politics of present-day Israel.

But Christians cannot broker any compromise on the Christian claim that we are bound eternally to the Jews as Jews.

The extent to which this strikes you as new information is the cause for the church to lament and repent.

It is the straightforward teaching of the New Testament that Israel must continue separately from the church as a necessary part of God’s final intention. Much like Marcionism, the proposition that the church has replaced Israel in God’s intentions may be common but it is nevertheless a pernicious heresy, today called supercessionism.

Remember, scripture anticipated the resurrection of all Israel not a single Israelite; likewise, scripture promised that the resurrection would occasion a final judgment, the permanent overturning of injustice, and the immediate arrival of the Kingdom.

This is not what the Father did with the Son.

Like so many of the wanderings in the Old Testament, the Lord took a detour. Israel’s Messiah has come but not in such a way that consummates Israel’s vocation.

As Robert Jenson writes:

Again, it’s a strict correlative to the doctrine of justification that what happens happens according to the will of God.“The truth is simple if at first perhaps surprising: God institutes the church by not doing something, by not letting Jesus’ resurrection be itself the End, by appointing the famous “delay of the parousia.” At the ascension, Luke has the disciples ask, “Lord, is this the time when you restore the kingdom to Israel?” Jesus avoids the question, and instead he promises the gift of the Spirit as the power to conduct a mission to the gentiles. The church, which came when the kingdom should have come, and leads to the kingdom by way of the mission to the gentiles, is precisely a detour from what before the fact had to be seen as the straight line of God’s purpose. Detours, indeed, are not uncommon in the Lord’s history with us.”

Therefore, what has happened is what God had to happen; that is, Israel did not credit the claims about her risen messiah. She did not do so; so that, the church would take the gospel to gentile world. As the apostle puts the matter clearly, God has consigned Jews to disbelief in Israel’s messiah as a intermediate component to his saving work for all.

Jenson writes:

“After the fact we can discern the appropriate step in the story: what had to happen is a gathering of the gentiles that is at once a mission conducted this side of the End and an event of the End itself. The needed step in the story is a body of Jews and a body of gentiles within the last great Day of the Lord, within the space opened by the delay of the Lord’s final advent, a detour from the straight path of the kingdom.”

“I will be your God and you will be my people.” This is not only the central promise of Israel’s scriptures, it’s a promise the church’s New Testament takes for granted. For instance, when the New Testament references “the people of God,” in every case but one it refers to the Jews. And even in the lone example when it does not refer to the Jews exclusively, it refers to the church in her relation to the Jews.

Following the strict logic of the New Testament:

Because the promises cannot fail, Israel abides as the people of God.

Meanwhile, the church can now claim to be the people of God only as an element of her hope, “only as she claims to be in God’s intention one people with the continuing nation of the Jews, and she must make this claim whether the recognition is reciprocated or not.”

In other words, Christians can lay claim to be God’s people only on the basis of the promise that in the End our song to the Lamb will be added to Israel’s more enduring melody.

It’s not simply that in Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim, God became a Jew. In that Mary’s boy ascended to the Father’s right hand, the second person of the Trinity remains a Jew, eternally so.And because the Son is the Israelite through whom we are incorporated into the triune life, the Jews are the people through whom we can claim to be God’s people.

Salvation is from the Jews.

This is nothing more than the mystery scripture names when it refers to the church as the body of Christ.

The risen Christ is the church but the risen Christ is also other than the church.

Both of the New Testament’s propositions are true.

On the one hand, “Lo, I am with you always.”

On other hand, “This Jesus, who was taken up from you . . . will come in the same way . . . .”

When the risen Christ is no longer other than the church, the “totus Christus” will be realized and God will be all in all.

But in the meantime—

Where is the risen Christ when he is other than the church?Once again, the answer is simple if perhaps initially surprising:

In that he is a Jew, in that his proper people is Israel, and in that the continuing community of Israel is a community other than the church, the risen Jew, Mary’s boy Jesus, must now not only be embodied as the church, but embodied also in the people Israel—until the End when the Song of the Lamb and the Song of Moses will resound into the simultaneous music of one people.

That Passover night in Nebraska, when the Haggadah was complete, Larry Trapp sat in the Weisser’s living room listening to Michael discuss the scriptures when Weisser’s daughter, Rebekah, interrupted them, kissing Trapp on the top of his balding head and offering to give him a facial.

Trapp laughed, and Rebekah returned a giggle. “Feels great,” she says. “Doesn’t it, Uncle Larry?”

Just so, when Larry’s kidneys failed, Rabbi Michael told NPR that it felt like he had lost a member of his family.

In that Larry, like most of us, was a Gentile, our gospel hope is that the rabbi was right.

He had lost a member of his family.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers