Jason Micheli's Blog, page 59

November 18, 2023

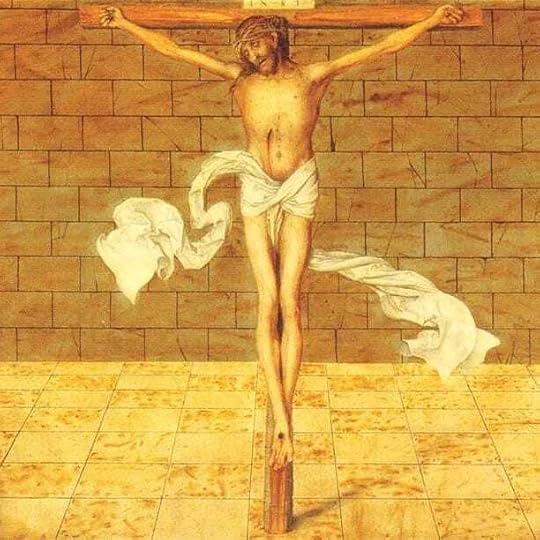

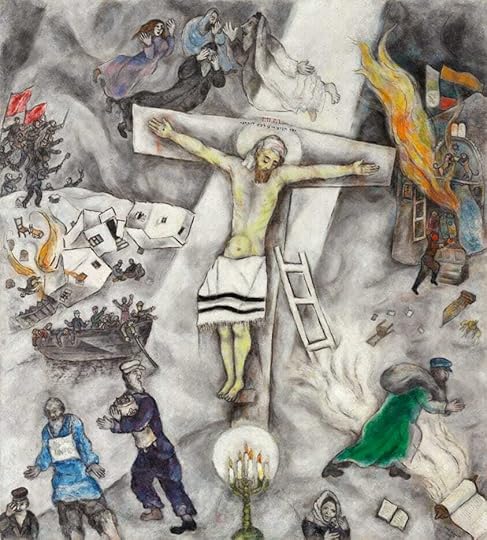

We Should Not Cover the Cross with Roses on Christ the King

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

This Sunday marks the end of the Christian year with Christ the King Sunday.

The theologian Gerhard Forde writes that conspicuously missing from the way most Christians speak of the crucifixion is the brute fact that we killed him.

We’ve so pushed the cross into the realm of theory, anchored it to divine necessity (what Forde calls “covering the cross with roses”) that we forget the cross was an event, in actual history, as real as any story in the newspapers, the end result of a basically simple story: In Christ, God came preaching the unconditional forgiveness of sins for sinners who do not deserve it, and we killed him for it.

November 17, 2023

Good Preachers Should Be Like Bad Kids

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Here is the latest in a series of conversations on preaching with preachers (and those who suffer them).

Number eight in our 9.5 Theses on Preaching:

Only preachers who have suffered under the judgment of the law and been freed from it by the proclamation of the gospel are able to hand on what they were first given to people in similar straits.

In his book The Foolishness of Preaching, Robert Capon makes a similar point about preachers needing to know firsthand the gospel as lifesaving:

I think good preachers should be like bad kids. They ought to be naughty enough to tiptoe up on dozing congregations, steal their bottles of religion pills, spirituality pills, and morality pills, and flush them all down the drain. The church, by and large, has drugged itself into thinking that proper human behavior is the key to its relationship with God. What preachers need to do is force it to go cold turkey with nothing but the word of the cross – and then be brave enough to stick around while it goes through the inevitable withdrawal symptoms.

But preachers can’t be that naughty or brave unless they’re free from their own need for the dope of acceptance. And they won’t be free of their need until they can trust the God who has already accepted them, in advance and dead as door-nails, in Jesus. Ergo, the absolute indispensability of trust in Jesus’ passion. Unless the faith of preachers is in that alone – and not in any other person, ecclesiastical institution, theological system, moral prescription, or master recipe for human loveliness – they will be of very little use in the pulpit.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 16, 2023

This is Not Darker than the Darkness We Have Known

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Here is my latest conversation with my friend Rabbi Joseph Edelheit, in which he reflected on the sense of aloneness that abides with Jews’s Jewishness.

Here is the article to which he refers:

Perhaps the most enduring wound for Jews from the Holocaust is the memory of aloneness. For 12 long years, the international community scarcely intervened as Nazi persecution gradually turned to extermination. Even as we established a sovereign state and created thriving communities in a free diaspora, there remained a lingering anxiety that the post-Holocaust era of Jewish acceptance was an aberration and that someday we would once again be alone.

The ancient fear of the Jews is immutable otherness. “They are a people that shall dwell alone and not be considered among the nations,” declared the pagan prophet Balaam in the Bible. The miracle of the post-Holocaust Jewish recovery was that, just as history seemed to confirm Balaam’s prediction, we managed to become a “normal” people, securing our place in the world.

But now we are at one of those defining moments in Jewish history when we find ourselves at a moral disconnect with much of the international community. As we struggle to absorb the enormity of the October 7 massacre and to confront a global wave of antisemitism, the trauma of aloneness has returned. Non-Jews rarely see the bitter messages that fill Jewish social media. One typical tweet in my feed reads: “First they came for LGBTQ, and I stood up, because love is love … Then they came for the Black community, and I stood up, because Black lives matter. Then they came for me, but I stood alone, because I am a Jew.”

Another tweet shows an empty street, with the words “London When Hamas Massacres Jews,” followed by that same street packed with pro-Palestinian demonstrators, and the words, “London When Israel Responds.” Anti-Israel rallies, we have noted, routinely attract large numbers of non-Muslims, but pro-Israel rallies attract mostly Jews.

Naively, we had assumed that the October 7 massacre would linger in the world’s consciousness. Surely those who had played down Israel’s security fears would now understand the nature of the threat we face on our borders. After all, this was no “ordinary” terror attack but a pre-enactment of Hamas’s genocidal vision. “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” – free, that is, of Jews.

Moral clarity

But a mere month later, the memory of Oct. 7 has faded, absorbed into the “cycle of violence.” “The attacks by Hamas didn’t happen in a vacuum,” said UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, citing the 56-year Israeli occupation. Both sides are responsible, added former president Barack Obama, urging us to “take in the whole truth” of the conflict. Yes, many Jews readily acknowledge, Israel bears its share of the blame for this hundred-year conflict. So do Palestinian leaders, who rejected every peace offer ever put on the table. But for all the complexity of the Palestinian-Israeli tragedy, this is not a complicated moment. No, we patiently explain, the massacre was not in response to anything Israel does but to what Israel is. And yes, the suffering of innocent Gazans deserves the world’s urgent humanitarian attention, but not at the expense of moral clarity about the justness of this war.

Once again we recite the litany of Oct. 7 – the burned and raped and dismembered bodies that were so disfigured that, a month later, many still haven’t been identified, the dying woman paraded to cheering and abusing crowds in Gaza, the kidnapped babies and the elderly, the pride with which the terrorists filmed their work. This is not a political conflict, we remind the world, but an outbreak of evil. Just like ISIS, we note, recalling the terrible devastation caused by the necessary American assault in Mosul and Raqqa. But increasingly, we sense that we are talking to ourselves.

The postreligious West, which substitutes the ideological rhetoric of academia for a genuine language for evil, doesn’t understand the old Jewish language we are speaking. Increasingly, we modern enlightened Jews find ourselves sounding like our grandparents. We may as well be speaking in Yiddish.We watch the mass marches against Israel with astonishment. What may well be the most horrific massacre of our time, outdoing even the atrocities of ISIS, has resulted in the unprecedented popularity of the Palestinian cause. Has the world lost its mind, we ask, even as we feel our own grip on reality faltering.

No, Israel is not a paragon of virtue. Hundreds of thousands of Israelis have spent this last year protesting every week against the anti-democratic Netanyahu government. But with the Hamas massacre, those arguments have been deferred until after the war. For now, we agree: Those who did that to the Jewish people must not be allowed to claim victory. To leave a genocidal regime on our border would be a betrayal of the founding ethos of Israel as a safe refuge for the Jewish people. It would be the beginning of our unraveling. We know that many of those who are demanding a ceasefire are our friends, good people who are horrified by Gaza’s devastation. But the fact that even they don’t seem to understand what’s at stake in this war, and that a ceasefire would allow Hamas to regroup, only reinforces our sense of isolation.

Yes, we say, the suffering of the innocent in Gaza is heartbreaking. But how to compare a deliberate assault on civilians with a war against a terrorist group embedded in a civilian population? Over and over we repeat what we’d assumed was self-evident: One side seeks to maximize civilian casualties, the other side to minimize them.

We are living the ultimate Jewish nightmare: to be slaughtered and then branded the criminal.Shifting the blame of genocide from Hamas to Israel is indicative of a deeper assault on the Jewish story. For anti-Zionists, the Jews are not an indigenous people returning home, but “white European colonialists” stealing another people’s land. Jews don’t belong in their own history. Denying the Jewish people the right to its narrative is an echo, however unconscious, of the ancient Christian doctrine of “Supersessionism,” which regarded the Jews as interlopers in the biblical story they had created. Instead, the Church had become “the true Israel,” replacing the fallen Jews who had rejected the messiah and were in turn rejected by God. Only after the Holocaust was that doctrine, the basis of centuries of persecution, rescinded by the Catholic Church and part of the Protestant world.

Most of us don’t want to live in bitter seclusion from the world. Zionism intended two kinds of Jewish return: The first was to the land of Israel; the second was to the family of nations. In 1945, the overwhelming majority of Holocaust survivors embraced the Zionist vision of the dual return of the Jews to their land and to the world. Like those survivors, we reject the ultra-Orthodox approach of radical separatism and see the Jewish people as inseparable from humanity.

Still, there are moments when we must risk going alone. We know that the longer the fighting in Gaza lasts, even our friends will begin to pressure us to relent. We must resist that pressure and not fear the consequences.

The ancient rabbis say that Abraham was called “the Hebrew” — “HaIvri,” from the root word for “across” – because he stood on one side proclaiming his truth and the entire world stood on the other. During the Second Intifada, when the IDF fought suicide bombers in Palestinian towns and villages, an exasperated Kofi Anan, then secretary-general of the UN, demanded: “Can the whole world be wrong and only Israel is right?” Israelis unhesitatingly replied: Absolutely.

This is a similar moment for us to reaffirm our identity as Hebrews. Last week, together with thousands of mourners, I attended the funeral of a 23-year-old soldier named Yonadav Raz Levenstein, who was killed fighting in Gaza. Yonadav, the grandson of my colleague and friend at the Shalom Hartman Institute, Chaim Solomon, married two months ago. Speaking at the gravesite, Yonadav’s brother called on the government to resist world pressure and persevere. He invoked Israel’s first prime minister: “David Ben-Gurion said that it doesn’t matter what the gentiles say, only what the Jews do.” Israelis across the political spectrum agree that the regime of Oct. 7 must be destroyed. Like Ben-Gurion, we are willing to pay the bitter price of being alone.

– Yossi Klein Halevi (A version of this essay appeared in the Globe and Mail)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 15, 2023

Why Do We Think Jesus is Talking about Money?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Matthew 25.14-30

This Sunday’s lectionary Gospel passage is Jesus’s parable of the talents.

From the vault, here is my riff on the text.

November 13, 2023

The Word that Gives Us Christ

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Hi Folks,

A couple of us are on the bench today with whatever is going around. So no Sola Session tonight. We will resume next week.

To whet your appetite for next week, here are some sessions we did with theologian Phillip Cary on the Gospel back during the pandemic.

November 12, 2023

Paradise for the Insane

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Revelation 21.1-6

There is a wonderful crescendo at the end of a famous sermon by the ancient church father Leo the Great, in which the fifth century preacher riffed on the two little words, “pro nobis.”

For us.

For us, he got up off his knees in Gethsemane.

For us, he carried his cross to Calvary.

For us, he surrendered his hands and his feet and his breath.

For us, he entered into death.

And storming the gates of hell, he harrowed it— for us.

Over ten years ago, in the days after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut— days which were deep into Advent— I referenced Leo the Great’s sermon in a reflection I wrote for my congregation:

When it comes to Christmas (and Christianity in general, for that matter), we tend to think the operative word of the season is “for.” Christmas is a time we feel drawn to doing things for others.

“For” is our operative Christmas word.

But that’s a problem. Because “for” despite all its good intentions, can’t repair broken the relationships between us, ease the alienation amongst us, or keep the poor from remaining strangers from us.

More fundamentally, our fixation with “for” at Christmastime is problematic because “for” isn’t the way God celebrates Christmas. Remember, the angel says to Joseph, “Behold, the virgin shall bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel,’ which means, “God is with us.”

With.

It’s a tiny little word but it gets to the heart of Christmas.

In fact, with is the most important word in the Bible. Scripture testifies that God’s grace in Jesus Christ is “the beginning of all the ways and works of God;” therefore, God’s whole life and action and purpose are shaped to be with us.

One of the lessons we discover when we refuse to run away from the sorrow of those mourn is that with is a lot more difficult than for. For doesn’t require a conversation, a real relationship, or any change in your own life to incorporate the other. What makes a gesture like “thoughts and prayers” ring hollow is not that they’re necessarily ill-intentioned, but that what those who weep the tears of Jesus need is not words for them but the faithful presence of a people who will be with them.

But with can be scary because the with seems to ask more of us than we can give.

And that’s why it’s gospel, good news, that God didn’t settle on for.

At Christmas, God said unambiguously, “I am with you. My name is Emmanuel, God-with-us. And how do we celebrate this good news in a world seemingly bereft of any? By being with people in their distress, even when there’s only so much we can do for them. By being with one another as an end in itself. By being with God in word and wine and bread rather than rushing in our anxiety to do or say, type or tweet, yet more things for God and others. More so than for, with is the word that gets decisively to the crux of the Story God is creating.

“And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, ’See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them.”

The Father only speaks to us in the Gospels two times.

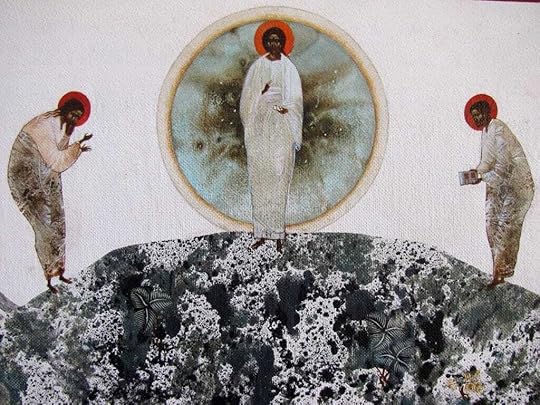

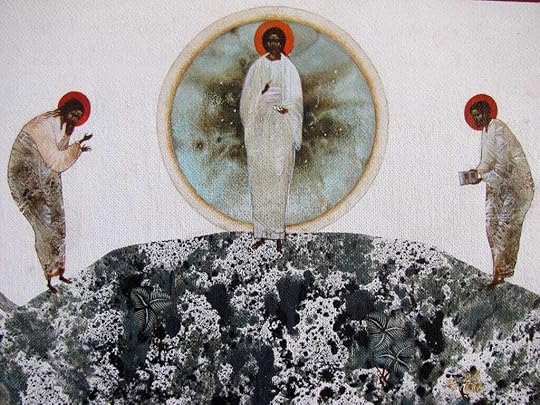

The first time God speaks is at Jesus’s baptism in the Jordan when the Father declares, “This is my priceless Son, with whom I am well-pleased.” The second time the Father speaks to us is on the high mountain where Jesus is transfigured before Peter, James, and John. Both times the Father speaks in the Gospels it’s to signal his identification with the Son who is likewise Mary’s boy and soon will be Pilate’s victim.

That the Transfiguration is just the second time the Father speaks in the Gospels is the interpretative key, for it discloses to us that the Transfiguration signals not an alteration in Jesus but a revelation of Jesus.

The disciples experience an epiphany. They experience what alcoholics call a moment of clarity. They see briefly who Jesus has been all along.

In the words of the church father, St. John of Damascus:

“Christ is transfigured, not by putting on some quality he did not possess previously, nor by changing into something he never was before, but by revealing to his disciples what he truly was.”

As Jesus shimmers with the uncreated light of God’s glory, Moses and Elijah appear on the mountaintop alongside the incandescent Christ. Of the three, only Jesus is like the Burning Bush, afire with the kabod of the Father but not consumed by it. The disciples see what the creed says— that Jesus is “Light from light, true God of true God, of one being with the Father.” Later in his life, recalling his glimpse of glory, the Apostle Peter will write in his second epistle that, looking back, the Transfiguration was the defining experience of his life.

In the moment, however, Christ’s transfiguration is more reality than the disciples can bear.

As before in the Gospels, Peter fills his fear with words:

“Lord, it is good for us to be here; if you wish, I will make three tabernacles here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.”

Tellingly, Jesus does not once again rebut Peter, “Get behind me, Satan!”

Jesus says not a word.

In fact, the Mount of Transfiguration is the only instance in any of the Gospels where Jesus does not respond at all to something someone has said to him.

The Transfiguration is the only instance where Jesus offers no reply.Thus, Peter is not completely wrong.He is more correct than we typically credit him.It is good to dwell with Christ.Indeed dwelling with God as God is your destiny from before the foundation of the world.“I will be your God,” the Lord uttered in his primal promise, “and you will be my people.”

Peter’s mistake is not in wanting to abide on the mountain and dwell with God.

Peter’s mistake is thinking that Jesus, Moses, and Elijah require three tabernacles when they need only one dwelling place.Peter’s mistake is not realizing that Elijah and Moses are not separate from Christ.

They are already in Christ.

With him.

In him.

He is their home.

Ellen Baxter is the founder of Broadway Housing Communities in New York. In the 1970s, as a psychology student at Bowdoin College, Baxter set out to discover a more humane way to treat the mentally ill.

As an undergraduate, she faked her way onto a psychiatric ward with a bogus diagnosis of dangerous depression so that she could observe how the patients were treated.

She left convinced that American culture's obsession with improving and fixing and changing ourselves had infected the mental health system too.

We're stuck on recovery, I heard her tell NPR.

We're stuck on recovery, but when you fail to deal with people as they are, when you're dead set determined to do things for them, fixing them and changing them, you end up changing them for the worse.

Because you erode their humanity.

Ellen Baxter's research through old medical journals and psychology articles led her to a modest village in Belgium named Geel.

According to those dusty journals, Geel had the highest success rate of recovery for the mentally ill.

At the center of Geel is a church dedicated to Saint Dymphna, who was martyred in Geel in the seventh century.

Saint Dymphna is the patron saint of the mentally ill, which is why, beginning in the eighth century, Geel became a pilgrimage destination for the mentally ill.

Five centuries later, starting in the 13th century, the residents of Geel began boarding those pilgrims into their homes.

Geel became a place where everyday people, farmers, bartenders, blacksmiths, ordinary people, welcomed the mentally ill into their homes, no questions asked.

Just as they were.

No matter the risks.

Welcome them like you would a beloved aunt or uncle.

By the 19th century, this practice of hospitality earned Geel the nickname “Paradise for the Insane.”

And by the turn of the 20th century, this Christian practice became a public system where doctors now place patients into the homes of hosts who have no idea what diagnosis their guests bring with them.

By 1930, over a quarter of all the residents of Geel were mentally ill, about 12,000 people.

According to Ellen Baxter, the average length of stay for a guest with a host family— and notice they call them guests, not patients— the average length of stay for a guest is 28.5 years.

More staggering, in Geel a third of all of the guests stay with their host foster family for almost 50 years.

They take these broken, crazy guests into their homes, and they live with them. In many cases, they die with them.

Baxter won a grant fellowship to study for a year in Geel.

She describes going from house to house in Geel, interviewing foster families, asking the same questions, and always getting the same answers.

“Do you find it to be a burden?”

“No."

“Do you find it tiring?”

“No.”

“Do you find it painful?”

“It's just life,” the bus driver told her.

“Over and over again,” she says, “I heard the same response from host foster families.

Host families would shrug their shoulders and reply that “crazy” is just a part of normal life.

It made me wonder if I had stumbled upon a race of angels.”

But Ellen Baxter says she still didn't understand why the villagers of Geel were so successful at rehabilitating guests, more successful than modern medicine.

And these are people with serious mental illnesses.

She didn't understand what made it all work until she met someone that she calls “The Buttons Guy.”

The Buttons Guy was a middle-aged man, a boarder, who every single day would twist all the buttons off of his shirt, nervously twirl them off slowly every single day.

And every single night— every single night— his host foster mother would sew all the buttons back onto the button guy's shirt.

Every day for 30 years, he twists them off.

And every night, she sews them back on.

"What a waste of time,” Ellen said, she said, when she first heard the foster mother describe what she did in order to live with the Buttons Guy.

“You should sew the buttons back on with fishing lines so he can't twist them off."

And the host mom reacted with something like offense.

“No. No, that's the worst thing you could do,” she said. “This man needs to twist the buttons off. It helps him to twist the buttons off every day. You don't understand,” she explained, “In order to accept the mentally ill into your home, you first have to accept what they're doing. You have to accept their oddness and their idiosyncrasies. You've got to let them take their buttons off.”

“Being with them, she told Ellen Baxter, “is the first step in being able to do anything for them."

And that's when Ellen Baxter stumbled upon what she calls the “Solution of No Solution.”

Once she knew what to look for in Geel, she said she saw it practiced from house to house.

What freed guests for healing and rehabilitation was the way their hosts refused to treat them as people with problems to be fixed.

Instead, they just welcomed them into their homes to share life with them.

The hosts’s acceptance of their guests without any expectation of changing them is itself the elixir with the power to change them.

Ellen Baxter calls what she found in the homes of Geel, quote, “The strange healing power of not trying to fix the problem for them.”

The strange healing power of that little word.With.

A decade ago, I concluded my letter to the congregation thusly:

If we are to offer our thoughts and prayers for those who sorrow, then let us pray rightly. As Robert Jenson insists, "We pray to God (the Father) with the Son and in Jesus’s Spirit. If we only pray to God, if our relation to God is reducible to the ‘to’ and is not decisively determined also by “with” and “in,” then it is not the true God whom we identify in our address, but rather some distant and timelessly uninvolved divinity whom we have envisaged…

The particular God of scripture does not just stand over against us; he envelops us. And only by the full structure of the envelopment do we have this God-who-is-with-us.” If there is any hope in this present evil age, it’s praying with Jesus, in his Spirit, to the God who has promised to be come and be with us.

Only that compact, conclusive word alone— with— can rectify what is wrong with us.”

The serpent says to Eve in Eden, “You will not surely die. For God knows that when you eat of the fruit of the tree…you will be like God.”

The last book of the Bible reveals what had been hidden in the first book’s opening chapters.

The serpent is not wrong.

Satan’s trespass is not to lie.The Tempter’s trespass is to give away the plot of the Story.Death will be behind us.

We will know God as God.

And just so, we shall be like him.

This is what the prophet sees and hears in the Apocalypse’s penultimate chapter.

The picture John sees matches the promise he hears:

“See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them.”

But then— notice— the prophet does not see God the Father.

Even in the Fulfillment, the Father’s infinity exceeds our grasp.

“God is unknowable in two senses,” Robert Jenson writes: “first, when we know God, we embark on an act that can never achieve rest, since it is finite knowledge of an infinite object; second, the very completeness of his revelation hides him. When God is all in all, these two come together. God will be more and more unknowable for being so intimately known. In God, we will know that he is infinitely beyond us. And this experience will be precisely the experience of his glory and of our participation in it. Even in the light of eternal beatitude, God is only known by being forever sought.”

Even at the End, the Father is a figure unseen.

Instead John sees the dwelling place descend from heaven to earth, already prepared by God.

The Tabernacle that is the New Jerusalem measures 12,0000 stadia— 1,500 miles— in every direction. Thus the City of God is a perfect cube. “It lies foursquare,’ John reports, “its length the same as its width.”

That is, the Kingdom is a perfect cube.Just like the inner sanctum in Israel’s Temple.In other words, it is the Holy of Holies stretched to an infinite size fit for all.The Lord will be our dwelling place.And since only God can dwell in the Holy of Holies, it follows that shall be made like him.Therefore, being taken into the heavenly home will simultaneously be our healing.On the mountaintop, Peter was only wrong about the number. To Eve in Eden, the Tempter’s trespass was not to lie. Like Peter, the serpent is correct. The Tempter’s trespass was to give away the plot prematurely.

We will be like God and live with death behind us.The Tempter’s trespass was spoiling the plot.But then, so did the ancient church fathers when they summarized the gospel with the slogan, “God became what we are; so that, we might become God.”

God means to make us like him.And God means to make us like him precisely by welcoming us into the home that is him and dwelling with us— we who are so disconnected from reality if it is true that Jesus Christ is Lord.

“God became what we are; so that, we might become God.”

Ellen Baxter describes another guest she met in Geel named Des. Des suffered tears every night that bloodthirsty lions were about to pounce through the walls to eat him. It wouldn't work to tell him the lions aren't really there. It wouldn't work to try to convince him that he should change and be not afraid, his foster mother, Tony, explained. Instead, every night, Tony and her husband would rush outside, banging pots and pans and roaring like lions themselves to scare the lions away. And that would work every time, Tony explained. He could rest. And then, eventually, one day, Des wasn't afraid of the lions anymore. And then, one day, the lions weren't there anymore.

“But this is important,” she said, “Making him unafraid of the lions, curing him of his tears, was not our goal. Our goal was simply to welcome Des into our home, just as he was, and to share our life— and here’s that little word again—with him. Only that with has the power to transform.”

In other words—

With is the ultimate For.

Look, maybe you don't twist the buttons off your shirt day after day. And you might not think lions are about to leap out of the walls. But we all suffer delusions. We all fall prey to seductive fictions. And we all hear voices.

I mean, some of you might be crazy enough to think that you're basically a good person and, like Peter, you think you can build a tabernacle for yourself, all by your lonesome, alongside Jesus. Some of you might be so insane, you actually think your sins are too great for Jesus Christ to have forgotten them forever in his grave. And some of you might just be deluded enough to think God’s going to evict you from the Last Tabernacle on account of your outstanding debts and poor credit history— your resentments and your jealousies, your broken relationships and your bitter strings of regret.

That's plain crazy.

We all suffer delusions. And we all hear voices in our heads. Voices telling us that we are unlovely or unloved or unlovable, voices telling us that we are inadequate or unforgivable, voices that never tire of pointing out all the ways we fall short of a standard that exists only in our heads, voices that never quite go away or quit their whispering.

Those are delusions.

But don’t beat yourself up, not a one of us is well.

So here the good news— spoiler alert:

The most important word; the little word with strange, healing power; the compact, conclusive word that is a solution that looks like no solution at all, God’s with is a word on which you need not wait.

As John Behr says, the earliest Christians referred to them as “passages of scripture” because if we sit patiently with them, like Elijah nestled in the crook of a rock, God will pass by us and, for a little while at least, dwell with us.

As Jesus says, ask, seek, knock and the Lord will answer his door to you.

With is a word on which you need not wait.Every humble prayer, every sitting with scripture— the Lord dwells there.

With is a word on which you need not wait.

The Lord comes to you, just as you are, with all your sin and insanities, without trying to fix you first, and he takes up temporary residence in the words of my mouth, at font and table.

The most important word is a word on which you need not wait.

Every gospel word, every creature of water, wine, and bread is a tabernacle of the Lord and thus, for us, they are paradise for the insane.Some come to the table, the operative words there may be “For you…” but Christ is the host and, therefore, the for is secondary to a more ultimate and healing with.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 11, 2023

Justification by Unbelief Alone

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Here is our most recent Monday night session on the Solas of the Reformation.

This week we discussed Sous Christus, Christ alone.

Here is the quote I read from Robert Jenson:

“Faith no longer means, in ordinary usage, what it did in the usage of the Reformers. Perhaps the abstract best would be to eliminate the vocabulary for ‘justification’ and ‘faith’ from our gospel-language altogether; for, as the words ‘justification by faith’ are now almost certain to be understood, they are an exact contradiction of the Reformation proposition. As we shall see, the whole point of the Reformation was that the gospel-promise is unconditional; ‘faith’ did not specify a special condition of human fulfillment, it meant the possibility of a life freed from all conditionality of fulfillment…

’Justification by unbelief alone’ could be, now, the only way to make Reformation point with this vocabulary.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 10, 2023

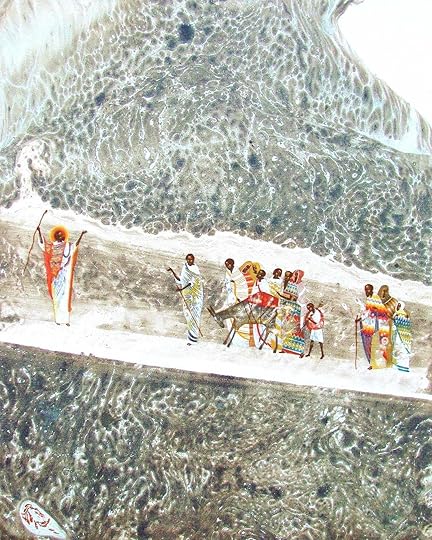

God Needs a Name

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

In her book, And God Spoke to Abraham, Fleming Rutledge recalls the confirmation program in the parish where she first preached. The group of thirteen year olds met every week for seven months. At the start of the course, Fleming prompted them with a simple exercise.

She asked each confirmand to draw a picture of God.

The results were not surprising.

“All sorts of things emerged,” she writes, “clouds, suns, circles, triangles, and a preponderance of old men with white beards.”

Once the confirmands completed the illustrations— idols— the class sat in a circle and took justifying their depiction of God. “At this point,” Fleming recalls, “a clean, empty wastebasket was brought in and set down in the middle of the circle.”

She then instructed each confirmand, one by one, to tear up his or her picture of God and throw the pieces in the trash. As they did so, the Bible was opened and the Second Commandment read solemnly, "Thou shalt not make for thyself any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, or in the waters under the earth."

The law provoked silence from the students who had just trespassed against it.

The turn came, Fleming writes, when she then asked the students the question at the heart of biblical faith: "If we can't draw a picture of God, and if we don’t know what God looks like, and if God isn't like anything in heaven or earth, then how can we know anything about God at all?"

While the students pondered the question, the teacher turned to an earlier chapter in the Book of Exodus, the story of the LORD encountering Moses at the Burning Bush.

As Fleming remembers it:

“We did this exercise every year at Christ Church, and every year the Lord was good enough to give us one or two bright-eyed young people who would catch on. Let me read the crucial parts again. Remember the question: How do we know anything about God? In the light of the Second Commandment, how do we know anything about God? That was the question. Every year, the story of the Burning Bush would elicit this answer from one or another boy or girl, ”He tells us! God tells us who he is!" It was always a magical moment in the class for those who "got it.””

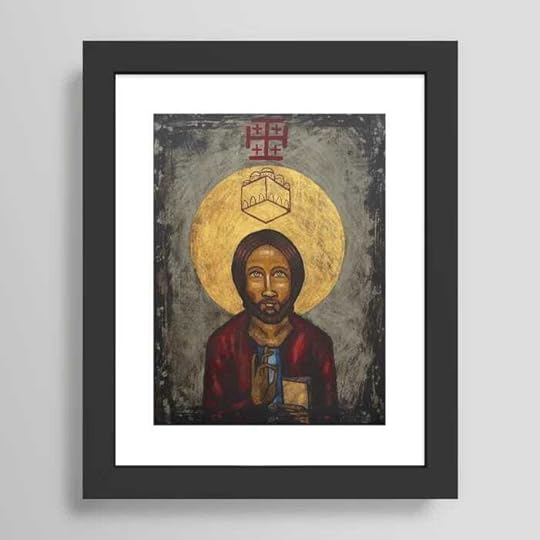

Unique against all other religions, the scriptures of Israel and the Church introduce a great contradictory interpretation of reality: God has told us who he is.That is, unlike all other putative gods the true God has a proper, personal name.Just so, God likewise has an identifying description.

Unique against all other religions, the scriptures of Israel and the Church introduce a great contradictory interpretation of reality: God has told us who he is.That is, unlike all other putative gods the true God has a proper, personal name.Just so, God likewise has an identifying description.The proper name Jason Micheli conveys an identifying description (e.g., the handsome fellow who loves Woody Allen movies). So too, the LORD’s name comes with a correlative identifying description; he is whomever raised Israel from slavery in Egypt.

Because God has a proper name and an identifying description, the word God is inadequate to speaking Christian, for it is neither a name nor a description.

It is a noun and an abstraction.

In common religious discourse, the term God has no particular definition other than the eternity which makes life in time possible. This is precisely why we prefer the general term God and its cognates (Creator, Redeemer, Sustainer) to the particular name of the LORD/Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

If God does not have a proper name and a particular identifying description, then we can project onto him whatever prejudices we may harbor about deity.For instance, if I simply address the pilot of my Southwest flight as Pilot, then I can entertain the fantasy that he is a fan of the Washington Nationals. Once I learn he’s Larry from the Southside of Chicago; however, I am forced to reckon with the knowledge that he is instead, regrettably, a fan of the White Sox. Thus, the proper name introduces the potential for irreconcilable differences between the LORD and what others call God. And difference— conflict—- is exactly what strivers in a secular culture want most to avoid.

Once again—

In that the scriptures of Israel and the Church posit the LORD’s proper name and a personal history, they insist upon a great contradiction of conventional religion.

Because his name is Yahweh, whenever believers in the scriptures hear a functional atheist protest, “I don’t go to synagogue or church, but I believe in God,” they should respond by querying, “Which god is the god in whom you believe— the God who sent Israel into exile because she’d cheated on him? Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim?”

With the claim that the LORD has a proper name and an identifying history, the Bible contends that all religious uses of the word God are but the verbal equivalents of the pictures Fleming once consigned to the rubbish bin.

Some may be nearer to the truth than others; nevertheless, they are projection not revelation. This is stern stuff perhaps, but there is a reason Israel has suffered persecution from the time God chose her (simply because he had fallen in love with her). Even when the Israelites were willing to go so far as to change their Hebrew names to pagan ones (Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego), they would not call Yahweh by one of his false rivals masquerading under generic nouns.

Yahweh is “the name above every name.”Yahweh is not the name that is equivalent to any other name.We make a fatal mistake if we use the word God with others under the assumption we’re all talking about the same person(s).

The scriptures use the generic noun LORD not as a way to accommodate all other names but out of reverence for the exclusivity and power of the true God’s proper name, “God said to Moses, "I AM WHO I AM.... Say this to the people of Israel, I AM has sent me to you." God also said to Moses, "Say this to the people of Israel, `The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob has sent me to you: this is my name for ever.”’

”He tells us! God tells us who he is!"

The true God has a proper name and an identifying history.

Still more importantly, you need the proper name if you are to trust the identifying description:

The Promise Needs a Proper NameThe generic noun in a slogan like, “God loves you,” is mere sentiment. “Who loves me?” the hearer would be right to wonder, “The Inner Self? The God of Trump’s “God Bless America?” The Invisible Hand of the Free Market? The distant First Mover of Jefferson’s Deism?”

Apart from the proper name, there is no absolution.Only knowledge of the proper name supplies an affirmative and trustworthy answer, “The God who raised Jesus, who came announcing pardon for sinners, loves you.”

Precisely, if we are to utter a promise about God— if we are to gospel another— it must be a promise made in God’s name.

Only the proper name carries with it a particular history by which the recipient can assess its intelligibility and trustworthiness.

Can it be promised that Allah forgives all your sins, gratis?

The Law Needs a Proper NameGod’s moral will— the law— also requires a proper name. For God to have a discernible moral intention for his creatures, he must have previously revealed and displayed it. He must have told us what his will is. That is, he must also have an identifying history.

The god of “In God we trust” very much wants me to covet my neighbors’s possessions. Our economy runs on such envy and fear of scarcity. Meanwhile, the LORD of the Exodus commands me not to covet, to seek him as my treasure and to trust him to provide for my needs.

The moral will of God must be proclaimed as a particular will if we are to follow it.If it is not a particular will, then our morality will invert the story of Abraham’s visitation and we will discover that we have only been worshipping ourselves unawares.

Straightforwardly, this is the standard Paul sets out in Philippians, “Have this mind among yourselves.” Paul does not exhort believers to have amongst them the mind of God. Rather, Paul implores the Philippians to “Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who…” and the whither of Paul’s counsel goes on to narrate the history which identifies and describes the name of Jesus.

The Future Needs a Proper NameThe news that Saddam Hussein lives with death behind him in the Last Future where will one day gather around him would be bad news not good news.

But the news that when you die you will spend eternity with God is every bit as frightening for its ambiguity.

The eschatological promise is only good news because of the name named in it, Jesus Christ the Friend of Sinners. As the End is the Fulfillment of the covenant, it makes all the difference that we know who is the God who has made this promise of the future to people of the long ago past.

An anonymous God cannot make an unconditional promise.The nub of the matter is simple if seldom examined.

We pray to God (the Father) with the Son and in Jesus’s Spirit.

As Robert Jenson writes:

“The decisive gospel-insight is that if we only pray to God, if our relation to God is reducible to the ‘to’ and is not decisively determined also by ‘with’ and ‘in,’ then it is not the true God whom we identify in our address, but rather some distant and timelessly uninvolved divinity whom we have envisaged…the particular God of scripture does not just stand over against us; he envelops us. And only by the full structure of the envelopment do we have this God.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 9, 2023

Trigger Warning

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Here is a another conversation I shared with Rabbi Joseph Edelheit.

Your questions and feedback have been helpful to both of us so keep it coming.

Here is the poem, “Trigger Warning,” Rabbi Joseph shares in our conversation:

מיה טבת דיין

אזהרת טריגר: שבת

אזהרת טריגר: קיבוץ

אזהרת טריגר: דשא

אזהרת טריגר: מסיבה

אזהרת טריגר: תינוק

אזהרת טריגר: דלת

אזהרת טריגר: ידית של דלת

אזהרת טריגר: של מקלחת של הילדה בערב,כל קר לי,

כל אני רעבה, כל מה את רוצה לאכול, כל חביתה, כל סוודר,

כל לא רוצה גרביים, כל "אמא" (אזהרת טריגר: אמא) כל

פעם בשעה שאני מתעוררת בלילה (אזהרת טריגר: לילה,

לילה) כל פעם שהשמיכה עולה ויורדת, אלוהים תעשה

שהיא עולה ויורדת, כל פעם שאני לוחשת לעצמי בחושך

היא כאן היא כאן, כל פעם שאני לוחשת לה אמא כאן אמא

כאן.

Maya Tevet Dayan

Trigger warning : Sabbath

Trigger warning : Kibbutz

Trigger warning: Grass

Trigger warning: Party

Trigger warning: Baby

Trigger warning: Door

Trigger warning: Door handle

Trigger warning: Each time my daughter takes a shower in the evening, each I’m cold,

Each I’m hungry, each what would you like to eat, each omlette, each sweater,

Each I don’t want to wear socks, each “Mommy” (Trigger warning: Mommy) , each time

Every hour when I wake up in the middle of the night (Trigger warning: Night,

Night) each time the blanket rises and drops God make it rise and drop

Each time I whisper to myself in the dark

She’s here, she’s here, each time I whisper to her Mommy’s here, Mommy’s

Here.

Finally, here is the essay on “On the Seriousness of Prayer” by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel that we discussed in our time together:

Seriousness is a hallmark of prayer. There is no prayer without seriousness. But what does “seriousness” mean? This concept seems to include four aspects, namely: honesty, commitment, authenticity, and weightiness. When we speak seriously, we are honest; a serious word is committed; a serious word is authentic and weighty. In prayer it is impossible to make false claims or pretenses, or to yield consciously to deception. Rather, everything depends on the measure of equality between intention and expression, on the harmony between conviction and awareness. Prayer without honesty is like scooping up water with a bottomless cup. A person praying means what he says. Prayer is not an impulse, not something frivolous or private, but a highly committed and consequential action. To pray means to engage directly with God, to expose oneself to Him, to His will and His insight. The person who prays intends to change his life: he places his fate in the metaphysical dimension and more or less desists from arrogance. Without that intention, prayer remains a monologue and a private recitation. The recognition of divine rule, yes, His engagement as ruler of the world, and the affirmation of all obligations that entails—these form the daily exoteric mystery of Jewish prayer. Anthems and hymns of praise are not meditations but acts of engagement taken seriously. Prayer is a weighty act. The word doesn’t flow by but applies itself with its full weight from out of the deepest layer of personal life. It forms the Spirit; it determines the fate of the person who prays. Again and again, true prayer is an event in a person’s life. Prayer is not a game, not an illusion, not emulation, not the generation of one’s own reflection, but an original act from which all elements spring, an occurrence that is real and true, in which nothing can be deceptive or manufactured. The use of slogans is the destruction of prayer. Prayer is not an activity that is in itself restorative or pleasurable. It is demanding and strenuous. It does not spring, like play, from an excess of energy, but rather from suffering and humility. It is not an activity that, free and aimless, finds satisfaction in itself, but rather it is directed to a goal and should have consequences. There is no room for nonchalance. A person who prays is aware of his responsibility and concerned about the content of his prayer. A person who prays wants to represent his concerns directly. An ironic stance toward their essential content is unthinkable. The expression of prayer flows forth, as if purely and directly from its intention, without the addition of any thoughts, whether central or ulterior. There is a wariness, a diffidence about praying with words that are not canonized in the fixed prayer texts. Rarely do new prayers arise. For in prayer every word has weight and a mysterious validity, every word is a word of honor before God.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 8, 2023

All Shall Be Saved

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Preaching my way through the last book of the Bible these past few months, the visions given to John have demanded I reckon with the comprehensiveness of the Last Future promised in Christ.

Some years ago, I co-officiated at a burial in Arlington National Cemetery along with a megachurch pastor who was famous for his pithy radio spots aired in the Washington, D.C., area. A fundamentalist member of the immediate family had insisted on the participation of a pastor “from a Bible-believing church.” When parts for the brief liturgy were doled out, this pastor told me, “I’ll just say a few words.”

The deceased man had died too early and far too slowly of cancer. After I prayed and read from the First Letter of Peter about the promise of an imperishable inheritance, my co-officiant stepped to the head of the casket and, after acknowledging the deceased man’s bravery and accomplishments, informed us that he had nonetheless “failed his most important mission.”

“He’s lost forever to us—and to God—because he never accepted Jesus Christ as his personal Lord and savior,” the pastor said. Then he invited all of us gathered by the grave to “treat this tragedy as God’s way of giving you an opportunity.”

I wondered whether the horror on the widow’s face was directed at the pastor or at the God of whom he spoke. Only later did it occur to me that nothing this pastor had said to us about God and eternity had been biblical. It had sounded Christianish, sure, but none of it came from the Bible he’d waved in the air. By contrast, the ancient liturgy I’d celebrated was really nothing more than a pastiche of promises straight out of scripture, beginning with the very last of Christ’s words of grace: “I died and behold I am alive forever more, and I hold the keys of hell and death.”

In his little book The Doors of the Sea, David Bentley Hart recalls reading an article in the New York Times shortly after the tsunami in South Asia in 2005. The article highlighted a Sri Lankan father, who, in spite of his frantic efforts, which included swimming in the roiling sea with his wife and mother-in-law on his back, was unable to prevent his wife or any of his four children from being swept to their deaths. The father recounted the names of his four children and then, overcome with grief, sobbed to the reporter that “my wife and children must have thought, ‘Father is here . . . he will save us’ but I couldn’t do it.”

Hart wonders: If you had the chance to speak to this father in the moment of his deepest grief, what should you say? Hart argues that only a moral cretin would have approached that father with abstract theological explanation: “Sir, your children’s deaths are a part of God’s eternal but mysterious counsels” or “Your children’s deaths, tragic as they may seem, in the larger sense serve God’s complex design for creation” or “It’s all part of God’s plan.” Most of us, Hart says, would have the good sense and empathy not to talk like that to the father. Hart then takes his point to the next level: “And this should tell us something. For if we think it shamefully foolish and cruel to say such things in the moment when another’s sorrow is most real and irresistibly painful, then we ought never to say them.”

His point is as prophetic as it is pastoral. If we mustn’t say such things to a father in grief, we ought never to say them about God. Indeed, if we are able to utter such things about God, it’s a sure sign that scripture has been conscripted into the service of a dogmatic tradition and thus religion has corrupted our conscience.

Beating at the heart of That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation is this same righteous indignation. As readers of his previous work will anticipate, the book displays the diverse range of Hart’s intellectual gifts. It is at once a theological argument, an exegetical examination, a patristic study, a metaphysical inquiry, and an astringent and often playful polemic against the alleged doctrine of eternal hell. But behind the turns of logic and philosophical jargon, That All Shall Be Saved is primarily the work of a stirred and unyielding conscience.

Hart insists that the transcendent God of absolute love and infinite goodness would not bring into existence a world in which one or more human beings might be condemned to everlasting misery and suffering. If this key claim is true, then it surely follows that “the God in whom the majority of Christians throughout history have professed belief appears to be evil (at least judging by the dreadful things they say about him).”

The elegance and erudition of Hart’s sometimes overwrought prose can prove misleading. Whereas Flannery O’Connor employed bizarre characters and grotesque plot turns to shock her readers awake, Hart deploys syllogisms and writings of the church fathers to the same end. Readers who would place Hart nearer to Plato than, say, Amos have not grasped the pathos behind the writing. As much as the prophets, Hart thunders against the corrosive effects of Christianities rendered cruel through their incoherence. In doing so, he alerts readers to a simple but often forgotten truth: if the behavior or character of the deity you describe would elicit moral revulsion when attributed to any other creature, then the god in question is but a creature. It is not the Creator.

His theological arguments and scriptural exegesis aside, it really is that simple for Hart—just as it was, he argues, for more of the ancient Christians than their posterity has permitted us to remember. The Father is not less merciful than the Son enjoins his disciples to be, nor does the Spirit sow fruit in us that is absent in or incongruent with the Father’s own attributes. God is good, as we teach our children. And we can teach our children that God is good because our conception of the good is analogous to the God who is Goodness itself and who has been disclosed to us in the self-giving of Christ. As Gregory of Nyssa taught, “the Word and he from whom he is do not differ in their nature.”

The Father is not less merciful than the Son enjoins his disciples to be.Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers