Jason Micheli's Blog, page 58

December 3, 2023

Even the Darkness is Not Dark to You

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

First Sunday of Advent: Genesis 21

A friend of mine, Rabbi Joseph Edelheit, recently forwarded me a poem written by the celebrated Jewish writer Maya Tevet Dayan. An Israeli citizen, Dayan composed the poem in the days following the October 7th massacre by Hamas. The poem was read in a synagogue in southern Israel during the Friday sabbath that followed the black Saturday of rage.

Dayan entitled her poem, “Trigger Warning:”

“Trigger warning : Sabbath

Trigger warning : Kibbutz

Trigger warning: Grass

Trigger warning: Party

Trigger warning: Baby

Trigger warning: Door

Trigger warning: Door handle

Trigger warning: Each time my daughter takes a shower in the evening, each I’m cold,

Each I’m hungry, each what would you like to eat, each omelette, each sweater,

Each I don’t want to wear socks, each “Mommy” (Trigger warning: Mommy), each time

Every hour when I wake up in the middle of the night (Trigger warning: Night, Night) each time the blanket rises and drops God make it rise and drop

Each time I whisper to myself in the dark

She’s here, she’s here,

Each time I whisper to her Mommy’s here, Mommy’s

Here.”

In the historic tradition, Advent begins not with luminous Chrismons nor with nostalgic anticipation of the birth of Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim. In the Church’s liturgical tradition, Advent begins in the dark and with desperate yearning for the return of Christ. Hence, every year Advent begins with John the Baptist wailing in the wilderness about the imminent winnowing fork of God’s wrath, “You brood of vipers!”Every year Advent begins by giving us Gospel passages with Jesus preaching apocalyptically, “Beware, keep alert…keep awake--for you do not know when the Master of the house will come.” And every year Advent begins with prophets like Isaiah forsaking any hope that we can improve our situation and pleading for God to rip the seam between heaven and earth and come down.

Every year Advent begins in the dark.Every year Advent begins in the dark because Advent is the season not of the first coming but of the second coming. We are waiting in Advent not for the eve of his arrival to Mary and Joseph. We are waiting on the angel’s promise at the beginning of the Book of Acts, “This Jesus who has been taken up from you into heaven will return in the same way as you have seen him going into heaven.” This is why the Church in the Middles Ages spent the Sundays of Advent reflecting upon the four last things (Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell).

Advent is the season of the second coming.

Just so, Advent— as scripture itself does— beckons us to look for redemption from beyond another sphere entirely.

Or, as St. Gregory of Nyssa summarizes the takeaway of Advent:

“Any apparent progress forward in history is really, underneath it all, nothing more than the futile washing in and washing out of waves on a beach.”

Advent typically begins in the dark so as to force a frank and sober acknowledgment that sin is frighteningly real and that human progress is a deep deception. So understood, there is no better time on the liturgical calendar than Advent for the Church to sit with a poem like Maya Deven’s “Trigger Warning.”

Baby.

Door.

Door handle.

Nevertheless, an observant Jew like the poet Maya Deven might point out that such a stress on the Lord’s distance from the world’s darkness does not jibe with the only scriptures Jesus and the apostles knew.

The world can indeed be a bleak and broken place.

No one knows this closer to the bone than Jews.

The world can be awful and humanity evil but that does not mean the Lord is absent or uninvolved.This is the unremitting confession of the Psalms:

Advent begins in the dark.But I wonder—Should it?“Where can I go from your spirit? Or where can I flee from your presence? If I ascend to heaven, you are there; if I make my bed in Sheol, you are there. If I say, ‘Surely the darkness shall cover me, and the light around me become night’, even the darkness is not dark to you…for darkness is as light to you.”

Should Advent begin in the dark?

Should Advent accent absence?

Each time I whisper to myself in the dark

She’s here, she’s here,

Mommy’s here.

An Advent stress on Christ’s future return and the world’s present darkness can suggest a God who is otherwise removed from us.

To posit the incarnation as the invasion of God into enemy territory implies that the Lord was absent prior to Mary bearing God.But such an aloof God is not the God of Israel. Indeed Mary’s assent gives a space for the God who all along has taken up space with his people Israel.Incarnation has been God’s modus operandi all along.As Daniel Boyarin, a Jewish scholar at the University of California, Berkley, writes:

Incarnation has been God’s modus operandi all along.In fact, the claim of the gospel is still more audacious.“If there is one thing that Christians know about their religion, it is that it is not Judaism. If there is one thing that Jews know about their religion, it is that it is not Christianity. If there is one thing that both groups know about this double not, it is that Christians believe in the Trinity and the incarnation of Christ and that Jews don’t. If only things were this simple…there was a time when many Jews believed in something quite like the Father and the Son [Jews certainly believe in the Father and the Spirit] and even in something like the incarnation…Christian ideas are not alien to us; they are our own offspring and sometimes, perhaps, among the most ancient of all Israelite-Jewish ideas.”

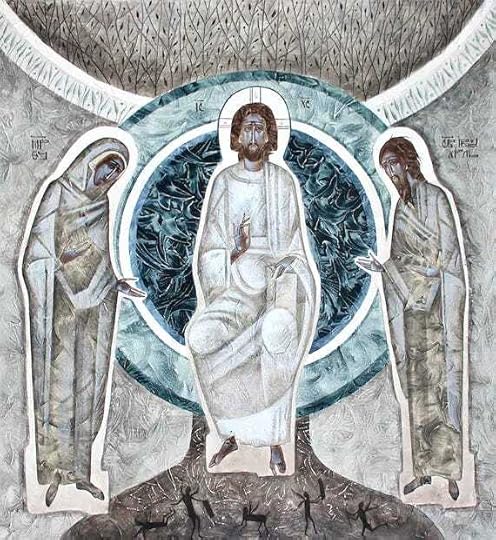

Not only is the God of Israel present to his people prior to the incarnation— the Spirit that overshadows Mary’s womb is the same Spirit who spoke by the prophets— the Lord Jesus himself is present to his people Israel more than a millennia before the Israelite named Mary gives birth to him.

This is the astonishing yet straightforward claim of the faith.

The events of the exodus occur thirteen hundred years before the nativity and the patriarchal narrative of Genesis recounts history that happened generations prior to God’s rescue of Israel from Egypt.

Thousands of years before she utters to the angel in Galilee, “Let it be with me according to thy word,” Mary’s boy comforts the mother of Ishmael in the wilderness of Beer-sheba.

This is what we have the audacity to assert every time we call God by his proper name: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

“Oh, how foolish you are,” the Risen Jesus gripes to the disciples on Easter, “and how slow of heart you are to believe…all of the Bible is about me.”

Exhibit A on the way to Emmaus very well could have been Genesis 21, in which the Lord Jesus consoles Hagar, Abraham’s Egyptian slave, “What troubles you, Hagar? Do not be afraid…for I will make a great nation of him.”As the ancient church father Tertullian puts it, in God there are three dramatis personae Dei, three persons of the divine drama. What scripture does is tell the drama of God with his people, showing three personae of the drama, each of which is other than the other two and yet is the same God as the other two. From the very beginning, the Father and the Spirit are straightforwardly two dramatis personae in the Old Testament, but what of the Trinity’s third person? “The Son’s presentation in the Old Testament,” Robert Jenson writes, “is even more clearly a matter of a plot-structure displayed both by the Old Testament’s total narrative, and by many of its individual incidents.”

For example, look again to the passage in Genesis.

Ishmael is the Plan B product of Abraham and Sarah having despaired of God’s promise. With Isaac weaned, Sarah feels little enthusiasm for Abraham’s and Hagar’s son sharing space with her own boy. At his wife’s insistence, Abraham casts off Hagar and Ishmael, exiling them into the wilderness where mother and child fall into weeping.

Take note how the passage displays the reality of God:

“The angel of God” speaks to Hagar “from heaven.”

The angel of the Lord at first refers to God in the third person, “God has heard the voice of the boy.”

Next— pay attention— without any break in the angel’s discourse, the angel shifts into the first person, “I will make a great nation of him.”

The angel of the Lord is thus one who simultaneously speaks of God in the third person and in the first person. The angel of the Lord is both one who is other than God and also one who is identical with God and is God’s speech-act. Or, as John puts it plainly in his own nativity of sorts, “The word is with God and just so is God.”

What the Gospel of John calls the Logos, the Old Testament calls the Angel of the Lord, both another than God and by virtue of the character of his otherness also God.Again, don’t take my word for it.

As the Jewish scholar Daniel Boyarin writes:

If you follow—That’s a Jew giving you, a Christian, permission to believe.Believe:Jesus is the one who comforts Hagar in the wilderness.Jesus is the one who meets the mother in her darkness, her fright and despair for her child, and says, “I’m here.”“The Angel of the Lord is precisely the point of a tension or ambiguity about monotheism at the heart of Israel’s religion. Throughout the Hebrew Bible there is confusion between YHVH himself, as it were, and his Mal’akh, the single, unnamed angel of the Lord, precisely in theophanies…No clear-cut distinction between YHVH this special Mal’akh is intended; they are two aspects of one divinity.”

How can this be so? The Christian answer is Easter. It’s the Risen Jesus, come from the Last Future— back in time, who consoles Hagar and cares for her son. You see— as a Christian, you have permission to believe astonishing things!

Maya Dayan, the Jewish poet, wears a bracelet she received at the music festival just prior to the October massacre at the hands of Hamas. It reads, “Radical love.” And yet, she writes, “I keep a long kitchen knife by my pillow. Fear has no limits and no sense. My land is bleeding. The same knife with which I cut salad for my daughters for supper is the one that lies by my head at night. I don't know how to tell my girls that brutality isn’t necessarily over even after a massacre ends.”

The darkness is real.

Your darkness is real— whatever black cloud enshrouds you.

Nevertheless!

Neither Advent nor any other season in your life can begin in the dark.It just cannot— darkness can never be the starting point for any of us.Because wherever you are, the Friend of Sinners is already there.And maybe you can’t hear him. Perhaps you can’t see him in the dark. But, like a mother over her child, Jesus is whispering to you, “I’m here. I’m here. I’m here.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

December 1, 2023

Is It Time for Me to Conceal My Jewish Identity?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Here is the latest in my series of conversations with my friend, Rabbi Joseph Edelheit.

This is the piece from The Forward that informed our discussion of anti-semitism, the cease-fire, and the ongoing hostage situation in Gaza:

When I lived in Germany six years ago, I didn’t wear Jewish star necklaces on the street. I didn’t tell strangers I was researching the state of the country’s Jewish community, lest they ask me if I was Jewish myself. The Jewish people within Germany as a whole seemed to be hiding: They didn’t wear kippahs or Jewish jewelry outdoors. Jewish institutions didn’t have signs on the fronts of their buildings.

Jews in Germany, I came to understand, were living within a culture of fear. Over the last several years, antisemitic incidents have risen dramatically there due to the rise of far-right populist politicians, anti-Zionist far-left rhetoric, as well as antisemitic activity by some members of the country’s Muslim community. When I got to Germany, enough antisemitic incidents had taken place there that most Jews felt they were better off concealing their identity publicly.

In 2019, I wrote an essay about how emotionally difficult it was for me to hide my Jewish identity in Germany. It seemed impossible — this culture of hiding.

When I returned to America, I found it difficult to stop hiding my Jewishness and started to come up with reasons not to wear my Jewish star: Maybe people who voted for Donald Trump might not like Jewish people. Maybe I’d pass an anti-Zionist on the street who didn’t like Jews.

My family members helped me learn how to combat this fear — my mother and sister still wore their Jewish jewelry around town, and my brother for a period of time wore a kippah. My father proudly kept his mezuzah on the front door post of his medical practice. Soon, I started to wear my Jewish star outside again too.

But after the attacks of Oct. 7 and the rise of antisemitic incidents in America, I’ve wondered: Can we really be so unafraid?

My brother doesn’t know if he’s safe to pray at his Chabad house in Atlanta anymore because the building doesn’t have sufficient security. On the week leading up to Hamas’ Day of Rage (a day on which Hamas leaders encouraged people around the world to attack Israelis and Jews), my sister texted me not to wear my Jewish star necklace outside in New York City where I lived.

My mother was afraid to go to our hometown synagogue to commemorate the yahrtzeit (death anniversary) of my grandfather in case an active shooter came. My father was the holdout — he was nervous to go to synagogue on the Day of Rage but felt determined not to give into his fear. He convinced my mother to go with him to shul that night. They said the Kaddish for my grandfather and luckily were safe.

When I told my grandmother I was going to a Shabbat dinner on the Day of Rage, she advised me to bring a knife with me in case someone attacked the apartment, which was located in a building known for having many Jewish residents.

When I came back from Europe, I felt confident that things in America could never be so bad for Jews. Our government was a lot better at welcoming the stranger, at embracing hyphenated identities. But now I see the problem of antisemitism getting worse here — more far-right-wing extremists are acting up, planning mass shootings and using social media to spread their message. Far-left advocates are using hatred of Israel to exile Jewish people from progressive spaces. The other day, my non-Jewish roommate told me she was happy we didn’t have a mezuzah on our door because if we did she’d be afraid.

My Orthodox Jewish friends are afraid to wear their kippahs on the subway. But on Friday nights, we still all get together for dinner.

On the Day of Rage, I had dinner with my Jewish friends and we sang. In fact, we screamed the words of Ariana Grande, Adele and Taylor Swift so loud in our apartment that if an attacker came, they would know where to find us. We didn’t care, we just wanted to be loud. I hadn’t felt so exuberant in so many days. It had felt like the world around me was crashing down, but singing with my friends brought in so much light. We didn’t know whether we wanted to hide, but together, we could feel joy, rest, and maybe even be at peace.

These days, I’m still wearing my Jewish star necklace, sometimes. It depends how brave I’m feeling. I shouldn’t have to feel brave in America to show my Jewishness, but here we are.

If you have questions for the rabbi, drop them in the comments or shoot me an email.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 30, 2023

Incarnation in Advent

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

This Sunday the Body of Christ begins a new liturgical year with the season of Advent. Formally, Advent anticipates not the first coming of the Father’s only-begotten Son but his coming again. In this way, the Church acknowledges the dissonance between the hopes named by the Old Testament’s expectation for Messiah and the world as it is presently constituted. The world, in Paul’s words, is still groaning in labor pains and suffering the last flickers of Sin. While Advent officially points to the Second Coming, I believe it behooves the Church to spend the season reflecting upon the mystery of the incarnation itself. After all, the Christmas season— the festival of the incarnation— is so short that it’s often over before folks return to worship from the holiday.

What’s more, an Advent stress on Christ’s coming again and the world’s present darkness can suggest a God who is otherwise absent from us— or was absent prior to Mary giving birth to God.

Such an absent God is not the God of Israel and her scriptures.Indeed Mary gives a space for the God who all along has taken up space with his people Israel.Here is a conversation on Advent and Incarnation between my podcast partners, Johanna Hartelius and Joshua Munnikhuysen.

Before you go:

Advent Class

On the Incarnation by St. Athanasius is by any standard a classic of Christian theology. Composed by St. Athanasius in the fourth century, it expounds with simplicity the theological vision defended at the councils of Nicaea and Constantinople: that the Son of God himself became fully human, so that we might become god. Its influence on all Christian theology thereafter, East and West, ensures its place as one of the few "must read" books for all who want to know more about the Christian faith.

The book is only about 50 pages long!

You can join us on the three Mondays of Advent at 7:00 PM or catch the recording later.

The link to the live class is HERE.

The book is in the public domain and available for free online, such as this example.

We will be using this new and accessible translation.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 29, 2023

The Light's Winning

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

The Old Testament lectionary text for the first Sunday of Advent is Isaiah 64.1-9:

O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence--as when fire kindles brushwood and the fire causes water to boil-- to make your name known to your adversaries, so that the nations might tremble at your presence! When you did awesome deeds that we did not expect, you came down, the mountains quaked at your presence. From ages past no one has heard, no ear has perceived, no eye has seen any God besides you, who works for those who wait for him. You meet those who gladly do right, those who remember you in your ways. But you were angry, and we sinned; because you hid yourself we transgressed. We have all become like one who is unclean, and all our righteous deeds are like a filthy cloth. We all fade like a leaf, and our iniquities, like the wind, take us away. There is no one who calls on your name, or attempts to take hold of you; for you have hidden your face from us, and have delivered us into the hand of our iniquity. Yet, O LORD, you are our Father; we are the clay, and you are our potter; we are all the work of your hand. Do not be exceedingly angry, O LORD, and do not remember iniquity forever. Now consider, we are all your people.

Every year Advent begins in the dark.

Every year Advent begins with John the Baptist wailing in the wilderness about the imminent winnowing fork of God’s wrath, “You brood of vipers!” John the Baptist always kicks off the most wonderful time of the year, “Even now the ax is at the root of the trees, and every tree that does not produce good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire!”

Every year Advent begins with Jesus of Nazareth preaching apocalyptically about the end times:

And every year Advent begins with prophets like Isaiah forsaking any hope that we can improve our situation and pleading to the God who appears to be absent in our world.”In those days…the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light,” Jesus preaches every Advent, “Then they will see the Son of Man coming in clouds with great power and glory…about that day or hour no one knows…Beware, keep alert; for you do not know when the time will come. It is like a man going on a journey, when he leaves home and puts his slaves in charge, each with his work, and commands the doorkeeper to be on the watch. Therefore, keep awake--for you do not know when the Master of the house will come.”

This year is no exception.

Every year Advent begins in the dark.

Here’s an Advent story—

Zachary Koehn is the now thirty-year-old father who was found guilty of murder by an Iowa jury. after less than an hour of deliberation. His four-month-old son, Sterling, had been found dead in a motorized swing. Sterling’s father, Zachary Koehn, was convicted of first-degree murder and child endangerment causing death. On Aug. 30, 2017, authorities arrived at the home of Zachary Koehn and twenty-one-year-old Cheyanne Harris where they discovered the lifeless body of their son, Sterling Koehn, in the swing. Autopsy results report that medical examiners found “maggots in various stages of development” in the boy’s “clothing and on his skin.” The baby, who weighed less than five pounds at death, was left in the baby swing for over a week. He was not bathed or changed that entire time. The county sheriff told jurors he found maggots and larva when the medical examiner began to remove the layers of urine-soaked blankets and clothing from the child.

The prosecutor distilled the shock in his opening statement:

“He died of diaper rash.”

"O that you would tear open the heavens and come down!” laments the prophet Isaiah.

The Old Testament scholar Brevard Childs argues in his commentary on the Book of Isaiah that this communal complaint in chapter sixty-four is not original to Isaiah, but rather is a Psalm of lament that predates Isaiah.

The prophet borrows from this preexisting corporate lament, Childs suggests, in order to speak to Israel’s despair and hopelessness as exiles in an evil and unrighteous world.

In other words, this collective, rage-filled indictment leveled at the state of the world and our complicity with it is not original to Isaiah’s time and place, but is an indictment relevant to every time and place— and will continue to be so until the Lord does, indeed, tear open the heavens and come again to judge the quick and the dead.

Advent is the season of the second coming.

You heard that right— Advent is the season of the second coming.Don’t let the decorations fool you.

In Advent, we do not— as popularly misunderstood— prepare ourselves for the rehearsal of Christ’s first coming.

No, in Advent we rehearse the righteous rage of the prophets who augured Christ’s first coming in order to long for his promised coming again.We are waiting in Advent not for the eve of his arrival to Mary and Joseph. We are waiting for his return “in great power and glory.” Advent is not the season when we anticipate his first coming. Advent is the season when we anticipate his coming again.

This is why the Church in the Middles Ages spent the Sundays of Advent reflecting upon the four last things (Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell).

Advent is the season of the second coming.

Don’t take my word for it. Consider the Advent hymns:

Sleepers, wake!” The watch cry pealeth,

While slumber deep each eyelid sealeth:

Awake, Jerusalem, awake!

Midnight’s solemn hour is tolling,

And seraph-notes are onward rolling;

They call on us our part to take.

Come forth, ye virgins wise:

The Bridegroom comes, arise!

Alleluia! Each lamp be bright with ready light

To grace the marriage feast tonight.

— “Sleepers, Wake!”

Lo! he comes with clouds descending,

Once for favored sinners slain;

Thousand thousand saints attending

Swell the triumph of his train:

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

God appears, on earth to reign.

Every eye shall now behold him

Robed in dreadful majesty;

Those who set at nought and sold him,

Pierced and nailed him to the tree,

Deeply wailing

Deeply wailing

Deeply wailing

Shall the true Messiah see.

Yea, Amen! let all adore thee,

High on thine eternal throne;

Savior, take the power and glory:

Claim the kingdom for thine own:

O come quickly!

Alleluia! Come, Lord, come!

— “Lo, He Comes with Clouds Descending”

The Sundays of Advent run backwards, the movement of the season is from the second coming to the first coming, starting with the eschaton and concluding with the incarnation.

This makes Advent unlike all the other seasons of the liturgical year. Whereas, the every other feast day of the church year— Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, Pentecost— celebrate the mighty acts of God in history, Advent looks beyond history altogether and awaits the return of Christ our Lord.

That Advent— as scripture does— beckons us to look for redemption from beyond another sphere entirely is a frank and sober assessment of our human situation.Advent points us beyond history so that we might recognize that human progress is a deception.

Or, as St. Gregory of Nyssa summarizes the takeaway of Advent:

“Any apparent progress forward in history is really, underneath it all, nothing more than the futile washing in and washing out of waves on a beach.”

The season of the second coming points us beyond history in order to compel us into the acknowledgment that “nothing that is possible can save us.” During Advent, therefore, we do not pretend— as many believe— that we are in the darkness before the birth of Christ. Rather, during Advent, we take a good hard look at the darkness we are in now, facing it and naming it honestly, so that we will understand with utmost clarity that our great and only hope is in Christ’s final, victorious return.

This is why we do not mark Advent with the color of Christmas— white— but with the same purple paraments that accompany us to Good Friday.

To grasp the scope of God’s great redemptive work in Jesus Christ— a work whose completion we still await— we must plumb the depths of the human predicament.Otherwise our faith is nothing more than sentimentality, and the promise of the Gospel is not a comfort, but a shallow idea.Grace is not amazing until you have apprehended the wretchedness of our state.

The philosopher Blaise Pascal wrote in his Pensees, “God being thus hidden, every religion which does not affirm that God is hidden, is not true; and every religion which does not give the reason of it, is not instructive. Our religion does all this: Vere tu Deus absconditus.”

“Truly, you are a God who hidest thyself.”

We need look no further than Advent to establish the truth of Christianity on Pascal’s terms. Even the prophet Isaiah today reverses the typical understanding of the problem of sin.

Notice, Isaiah does not say that God has hidden himself from us because we sinned— as a punishment.Isaiah flips it and concludes that we sin, because God has hidden himself from us.November 28, 2023

An Advent Conversation with Fleming Rutledge

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Hi Friends,

To kick off the Advent season, I thought you might enjoy this conversation I shared a few years ago with the inestimable Fleming Rutledge. Thanks to the (evil?) powers of A.I., I’ve included a transcript of the conversation below.

As always, thank you all for the questions, comments, and encouragement you send my way. I’m grateful for the community you’ve helped create through this space.

— J

Welcome to Crackers and Grape Juice, where we talk about faith without using stained glass language. On behalf of my partners, Joanna Hartelius, Teer Hardy, and Taylor Mertins, I am the commander of this podcast ship, and my name is Jason Micheli. Our guest today for this latest episode is the one and only...

Fleming Rutledge. Fleming is a hero of mine. I think she's the best damn preacher in the world, and I also count her as my backup wife should anything happen to my beloved. Fleming has a new book out called Advent: The Once and Future Coming of Jesus Christ. And so she joined me for a conversation about this book and the season of the second coming called Advent. And we've also gone beyond just this conversation with her. We have set up a Christmas that in Fleming's honor we are calling Advent Begins in the Dark. You can find these devotionals by going to AdventBeginsInTheDark.com. You can subscribe there to get the daily devotionals by email. You can also go to our Crackers and Grapefruit Facebook page and there join a private group for Advent Begins in the Dark where you can discuss the devotionals with a group of 300 of your closest strangers and go a little bit deeper.

Devotionals are being written by us from the podcast as well as other people from our constellation of listeners and friends. So you'll be getting devotionals from people like Will Willem and Fleming herself and a host of others. So without further ado, I want to just let you know also, also news on the podcast front, we have added an official producer to this show. That's right. We're moving up in the world. Tommie is now serving on the team in that capacity. So give her a shout out for the good work that she is doing for us. And you can do that by finding our podcast on iTunes and giving us a rating. You can go to our Facebook page or our website and share it on all those different social media channels. Share the love, express your gratitude. We didn't ask for a damn penny from any of you on Giving Tuesday instead of being manipulated with hashtags, we're just asking you to pass it along and pay it forward. So that's it.

Enjoy this conversation I had with Fleming.

Have you got more of a beard now? No, it's the same. It just looks different. All right. All right, Jason, what do you want to talk about today? Advent. Oh, all right. I assume you're ready to do that. Yes, I am. So I have your Advent book here.

And so I thought maybe we could start by you connecting your two most recent books. And so it seems to me that your emphasis on rectification in your book on the crucifixion connects to God's commitment to return in Advent. So just talk about Advent in the context of rectification. It's really extraordinary that you should start with that because I do have this quotation here that I want to read and I was thinking that it didn't really necessarily fit into the book.

program for today. But if you are talking about rectification, then it certainly, most certainly does. I've got two books that I'm reading that I want to talk about. I usually have three or four books going at once, as I think most readers do. And I'd like to read something from Charles Dickens' great novel, David Copperfield, which I had never read before, incredibly.

And it brings up the whole matter of rectification very strongly, not that Dickens had that in mind, but that's what it hit me. This is a 900 page novel, so I'm only halfway through it. And I'm laboring against Dickens' well-known sentimentality, which bothers me, but the greatness of Dickens does continue to override that problem. And I'll give an example, which is related to rectification.

This is a scene from the book, it's a very moving scene, in which little Emily has run off with a scandalous young man. And the situation is really very distressing because she is so much beloved by her uncle who adopted her when she was little. And he vows that he will go and find her and bring her home. Sounds like John Wayne looking out, running after his niece through thick and thin, but with a very different frame of mind say the least. He's ready, John Wayne, as you will remember, was ready to murder his niece, rather than bring her back into civilized society. And so we have to hear a couple of different images of ways to face and come to terms with sin, suffering, distress, human failure, and the enormous waves of recrimination that reverberate through a human community when there is an episode of sin and or evil. So the situation is that the uncle, Mr. Peggati, has vowed to go and find his niece, who is certainly in a distressing set of circumstances because the young man that she's been seduced by has no intention of marrying her. And her uncle is a very moving scene and I won't read all of it at all. I'll just read this short part. At the very end of the chapter, young David Copperfield says that he cannot forget the solitary figure of the uncle Toileon, poor pilgrim, and recalling his final words. I'm going to seek her far and wide. If any hurt should come to me, remember that the last words I left for her was.

My unchanged love is with my darling child and I forgive her. Now that's one of the choke up moments that Charles Dickens gives us on a regular basis, but it is a Christ figure. The uncle is clearly a Christ figure and Dickens certainly was some kind of a Christian because he often has moments in his books where you can see it coming through the the uncle who is going to seek for the lost sheep, even if it comes to his own death because he's going into dangerous places where there are all sorts of unsavory characters. Even searching at the risk of his own life and his own mental health and his own fortune, not that he has one, he says, my unchanged love is with my darling child, clearly a Christ figure. And then he says, and I forgive her.

Now one of the themes that ties together my two books, The Crucifixion and Advent, is the subject that you have just brought up, justification as rectification, and the word rectification meaning, essentially, to make right what has been wrong. Now in the case of the girl in David Copperfield, the action of the young man in seducing her with absolutely no concern for her welfare or for her family and her own weakness and vulnerability in falling for his seductive and very underhanded and really wicked ways. All of this reverberates through many, many families and has multiple effects, which reminds me so much of Garrison Keeler's now well-known reflection about a man who is about to leave his wife.

And as I recall it, he is sitting out in front of his house, maybe waiting to be picked up. I'm not sure, I don't remember the details, but I know that he is positioned in his neighborhood, on his street, as he prepares to abandon his family. And he has this image in his mind of a little girl in a neighboring house, upsetting her glass of milk. And he connects that directly with his own action and he decides not to leave because he sees the reverberations of such an action throughout his community and its effect even on the youngest members of the community. A lot of people have been much struck by that reference, almost an offhand reference that Garrison Keeler made, but I emphasize this because every human act of disruption has ripple effects throughout families and communities forgiveness alone cannot make that right. That's the point I'm driving toward. The uncle in David Copperfield says, I forgive her. And that is very important because he is forgiving her even as he is seeking her out. In direct contrast to John Wayne, who is seeking his niece throughout the West, but has not forgiven her and is storing up anger in his heart throughout the story, leaving him in the famous conclusion, alone outside the door. What I'm driving at here, in case people are wondering, is that God's action in Jesus Christ, his action of righteousness for the justification of the world is more than forgiveness. I want to emphasize that because most people seem to think that the very heart and center of the Christian faith is forgiveness. And that's true, but that's not enough to say. As Reginald Fuller, a very important New Testament professor said 50 years ago, forgiveness is not enough to describe what God does. And you brought up rectification, for which I'm very grateful because I had this so much on my mind in the last couple of weeks as I've been reading. The other book that I'm reading that is directly related to this subject is James Cone's The Cross and the Lynching Tree. I did not know about this book somehow, which is incredible. I can't believe it. Apparently a lot of people didn't know about it either because no one told me I should read it.

All the people who were advising me about my book, The Crucifixion, never mentioned it. I go into a lot of detail about the civil rights movement and racial issues in The Crucifixion. Nobody said, you must read this book. And I'm just really very grieved that the name of the author, James Cohn, who I knew at Union Seminary, his name does not even appear in my index the book does not appear in the bibliography of the crucifixion. This is a major gap. And he points out repeatedly in the book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree, that virtually no white person in the church, no theologian, no biblical scholar, no pastor, no teacher, no writer, no white person linked the cross with the lynching of black people. And that is an appalling fact, apparently.

And it's certainly true of me. I try to, in my book, The Crucifixion, I try to find a contemporary reference, a contemporary form of execution that might be comparable. The electric chair has been mentioned, and I bring that up, but then I say that doesn't do the job. I never even bring up the lynching tree because I never thought of it. I thought of lynching often. I knew about...lynching and I knew about the photographs that were taken and I knew about the crowds that would come out and watch and I knew about the mocking and I knew about the postcard pictures that were passed around. I knew all that but somehow I missed the connection to the crucifixion of Christ. The book The Cross and the Lynching Tree makes this connection, well I start to say at great length, it's not a long book and it's very easy to read so I want to urgently recommend it to everyone. It is a limited book in the sense that it focuses only on one aspect of Jesus' crucifixion. People will complain, well, there's no atonement here. That's true. People will complain that there isn't any doctrine of recapitulation here. That's true, and so forth. It's really, in a sense, not a very theological book. It's a passionate, literate outcry on behalf of James Cone's own community, the Black community.

And I think every white person who is serious about the depth of the problems that we face needs to read this as well as we the fact that we need to read it in order rectify our own imagination. Our failure of imagination. Jim Cone talks a lot about failure of imagination and how the black writers and poets, even the ones who were not religious like W.E.B. Du Bois, who was not a poet, but was a storyteller and of course, a thinker. He, with imagination, repeatedly invokes the crucified Christ in his writings. I didn't know that. I know something about James, about W.E.B. Du Bois. I'm very interested in him because he was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts and raised there. And that's where we have our country hosts. So I'm very keen on W.E.B. Du Bois, but did not realize how frequently he invoked the image of the crucified Christ in his work. So all of this in the long run is about rectification. And rectification is the word that some, not all, but some New Testament scholars now prefer to the word justification because it emphasizes this power of God and the promise of God to make right what has been wrong. And forgiveness can't do that. Forgiveness can create a breakthrough or what we often refer to as healing. But even with healing, the scars are there. The feelings are still there. You don't ever get past them entirely with forgiveness. And the wrong is not righted either. And the damage done to the larger community is not affected in any complete way by the act of forgiveness. Although the act of forgiveness is very, very powerful and often will stop the violence, but it will not rectify what has been wrong.

And so when we think of the word justification in Paul's writing, certainly one of his favorite words, we need to think of it not just as saying, that's all right, I forgive you, it's done away with, you can move on, you are a new person now. All of that is true of forgiveness and true of what is traditionally thought of as justification. But what Ernst Kasemann, the extraordinary New Testament scholar of the 20th century. What he saw that was really rather revolutionary was that righteousness, justification, de kiosu in Greek or de kios in Greek, means the power of God to make right. And that is what is linked to the second coming in the teachings of the scripture about the day of the Lord in the Old Testament. What do you think is the necessary connection between righteousness as something that's declared about us and something that God does in us and in the world? As usual, Jason, you have a way of going right to the heart and clarifying a point that I'm trying to make it in way too much length. That's the distinction. That's the distinction that Kasemann wanted to make. And that's the distinction that his very numerous, what shall I say, not disciples, not followers, but

And those who have been profoundly influenced by Kasemann want to hold on to precisely that distinction that you just made. Justification has been traditionally interpreted, especially in the Lutheran tradition, as what did you say? About us. Yeah, a declaration that we are justified means that we are cleared of our guilt and sin, made new people. This is all very important. I don't want to denigrate it. But it doesn't say everything that needs to be said. It doesn't speak to the power of God for new creation. And new creation means, and I can't help thinking again, of Miroslav Volf here, his book called The End of Memory, where he speaks about how even the memory of evil, sin, death, unrighteousness, wickedness, if you will, maybe we should use the word wicked more often, in a theological sense, even the memory will be gone. That's what justification is capable of. We are not capable of that. We are not capable even in forgiveness of erasing the memory. The memory is still there. It's eating away. Not as much as before the forgiveness, but it's still there. And it recurs involuntarily from time to time and has to be fought down. In Christ, in the justification wrought by God in Christ, Miroslav Volf suggests that even the memory will be erased and all will be made new. How do you feel about the idea of memory being erased? Well, I don't want to oversimplify it. It's complicated. We certainly don't want to. We want the memory of love to be erased, or that the memory of those whom we love, and those whom we did not even know we loved, and those whom we did not love, but now love in the new day, that will not be erased. We're talking here about the corroding and corrosive memory of evil confront this in a dramatic sense. And that's one of the things that people who work with tortured victims have to struggle with, the persistence of the memory of the torture, which flares up unbidden in all kinds of ways. I would like to return to the subject of the Advent season, and to say that I found echoes of its meaning throughout the book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree. It's a motto of the book of the dialectic between faith and doubt, the dialectic between suffering and hope, the dialectic between pain and promise. And those are the themes of Advent. I like to say we have to keep our hands in the air all the time, like the scales of justice balancing one off against the other. He contrasts, for instance, he doesn't contrast, he brings into conversation, into the dialectic, the figures of Job and Jacob. Job on the one hand, Jacob on the other hand. Jacob representing the future and hope and Joe representing protest, protest against the treatment that he has received, which seems to be so unjust. So he, Cone, talks about the struggle of the black community to live with their suffering all the time. And that hasn't changed. Living with it all the time, living with the doubt about whether God even exists all the time. And yet, in an unusually powerful dispensation in the black African-American community, an unusually almost unique character of the Christian faith in the black church, the power of hope. What did Desmond Tutu refer to this in a quotation from I think it's Zachariah, I have a hard time remembering Zachariah versus Zephaniah, but I think it's Zachariah who talks about prisoners of hope. When I first read that biblical passage, that really jumped out at me. Prisoners of hope. We are held by hope in captivity to hope.

In spite of our captivity to bondage, we are also captive to hope. And that meant a lot to Desmond Tutu during his struggle against apartheid. So it really does seem to me that the Black race in general, its particular form of Christian faith is a very Advent faith. And I'm just thinking about all the criticism I'm going to get on Twitter and otherwise about how the cross and the lynching tree is very narrow in its focus in terms of what the crucifixion represents doesn't deal with the various Biblical images in the way that I do in my book about the crucifixion, but I'm gonna push back very hard against that kind of protest, because it represents to me a kind of restriction of the work of Christ on the cross, where we have to fit him into our favorite box, whether it's substitution or penal substitution or Christus Victor or whatever it might be. We seem to want to imprison him in our own take on the subject of the meaning of the cross. And whereas in my book, The Crucifixion, I've tried to expand that as far as I was capable. I also want to say that I want to protest against people excluding voices like James Cone because he does not voice traditional motifs or theories of atonement. I was just wondering how you would recommend preachers preach about racism and the season of Advent in particular. I think it's always best in sermons of this sort to make it concrete. I remember Jim Conant, always protesting that theology was not concrete enough. That was his theme. He used to talk about that all the time. It got a little bit annoying actually. But sermons do need to be concrete. We need to give examples of what we're talking about. And it's not hard to find examples of black people express hope in the midst of hopelessness. It happens all the time. I read it in the newspapers constantly. I've always noticed how the New York Times simply will not quote anything Christian unless it's said by a black person, and then they'll quote it. The name of Jesus Christ is not quoted unless it's a black person talking. And I've got so many examples of that in my files. It's just really striking how they will quote the testimony of a black preacher or a black person who has suffered, and they'll call on the Lord or they'll call on the name of Jesus, the New York Times will quote it. We owe the black church so much, and I think of them particularly in terms of Advent, because whereas they never lose sight of the cross, the suffering Jesus, they also live out every day this dynamic, this dialect between doubt and hope, faith and disbelief between what's going on now and the promise of God. Holding onto the promise and looking for signs that the promise is true is what the Christian life is shaped by. That's Advent. Holding onto the promise, even though all the indicators are to the contrary. That's Advent. But the Advent season with its overpowering note of anticipation and promise by its very nature reveals to us in glimpses, glimpses only, but nevertheless life-sustaining glimpses of the promise making itself known even now, even in the worst situations in the faith of believers.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 27, 2023

Apocalypse Later

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

The church begins a new year this Sunday with the start of the Advent season. The assigned gospel for the first Sunday of Advent is the “Little Apocalypse” in Mark’s Gospel, chapter 13:

Isn’t it funny how we persist in thinking of Jesus primarily as a teacher of golden rules and a dispenser of good deeds?Jesus's longest discourse, by far, in Mark’s Gospel is this sermon that makes Halloween seem tame by comparison.

"But in those days, after that suffering, the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken. Then they will see 'the Son of Man coming in clouds' with great power and glory. Then he will send out the angels, and gather his elect from the four winds, from the ends of the earth to the ends of heaven.

"From the fig tree learn its lesson: as soon as its branch becomes tender and puts forth its leaves, you know that summer is near. So also, when you see these things taking place, you know that he is near, at the very gates. Truly I tell you, this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place. Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away. "But about that day or hour no one knows, neither the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father.

Beware, keep alert; for you do not know when the time will come. It is like a man going on a journey, when he leaves home and puts his slaves in charge, each with his work, and commands the doorkeeper to be on the watch. Therefore, keep awake--for you do not know when the master of the house will come, in the evening, or at midnight, or at cockcrow, or at dawn, or else he may find you asleep when he comes suddenly. And what I say to you I say to all: Keep awake."

During his three year ministry, Jesus has spent a lot of his time at the temple; so that, by the time we get to the cusp of the passion story, Jesus is like Peter Finch in Network. He’s mad as hell and he’s not going take it anymore.

Jesus has just been condemning the temple guild for “devouring the homes of widows,” widows like the old lady with the pocket change she set aside from her old man’s pension. Yet the disciples manage once again to miss the point. As soon as they march out of the temple Jesus has just condemned as the first century equivalent of a payday lender, the disciples start admiring its architecture.

"Teacher, look, what large stones and what large buildings!”

“Let me tell you about those buildings. It’s all going to come crumbling down.”

Jesus says no more until they come to the Mount of Olives, the place where the prophet Zechariah had proclaimed God’s messiah would commence his saving work. “Lo, the Day is surely coming,” Zechariah prophesies, “On that day the Lord’s feet shall stand on the Mount of Olives, which lies before Jerusalem on the east; and the Mount of Olives shall be split in two.”

Stones will be turned, one upon another.

So it’s not surprising that, as they sit on the Mount of Olives looking across the valley at the edifice Christ has just said will soon be eradicated, they’d get to thinking about what Zechariah called the Day of the Lord, the time when God will come again to judge the quick and the dead. No sooner has Jesus just predicted the temple’s destruction than they’re sitting at ground zero for God’s mushroom cloud-laying messiah. In other words, it’s a rather obvious question the disciples ask.

“When?”

“‘Tell us, when will this be, and what will be the sign that all these things are about to be accomplished?’”

And immediately Jesus cracks the whip, chastising his disciples “Do not be led astray by asking ‘When?’”

“Only the Father knows the day and the hour,” Jesus preaches at the end of his fire and brimstone sermon.

That is—

“When?” is a question that cannot be answered; therefore, “When?” is a question that should not be asked.Do not be led astray by the when question, Jesus warns.

There will be wars and rumors of more. There will be earthquakes and famines and floods. There will be plagues and pandemics and polarized families. There will be grifting prophets and phony preachers. It’s going to get worse before God makes all things new. All the bad that’s certain to be is but the beginning of the birth pangs.

Do not get distracted, trying to read the signs of the times, Jesus scolds.

Do not get preoccupied, attempting to make predictions, Jesus reprimands.

Do not be led astray by asking “When?”

When are you coming again?

When will be the End?

Nonetheless, Jesus would make an absolutely horrible HR director. He’s a rotten evaluator of talent. Down through the years, the rest of his recruits have proven to be every bit as bad at heeding his words as the initial dozen.

I mean— despite this unambiguous rebuke from Jesus, for two thousand years his friends have frittered away their time and squandered much of their witness, busying themselves with the one question Christ Jesus commands us clearly not to probe.

When will this be?

What will be the signs of the end time?

For example, the year 500 AD proved too auspicious to avoid speculation. Long before Dan Brown or that purple haired lady on the Trinity Broadcasting Network, ancient Church Fathers— legitimate thinkers and leaders— like Hippolytus of Rome and Irenaeus of Lyon predicted Christ would come again in the year 500. And they attempted to prove their prediction by “decoding” the dimensions of Noah’s ark. Pope Sylvester II predicted the apocalypse would occur at the turn of the first millennium, Y1K. When Jesus did not come again to judge the living and the dead, Sylvester and others regrouped and insisted that the only detail they’d gotten wrong was the starting point. The End would come not a thousand years after Jesus’s birth as they’d thought but a thousand years after his death, 1033 AD. Joachim of Fiore was a Catholic mystic who discovered what he called the secret “eternal gospel” in the Book of Revelation, 14:6. According to him, Christ would come back and inaugurate the Age of the Spirit in 1260 AD.

Flash forward a couple hundred years and it gets worse.

Thomas Muntzer was an Anabaptist in Germany— a Mennonite— who scoured the scriptures to interpret the signs of his time. Muntzer became convinced that the world teetered at a tipping point. He predicted that the New Age would arrive in the year 1525. The revolutionary furor his prediction unleashed ignited a violent rebellion by the peasants in central Germany. The revolt was quelled with equally great violence. The when question led Thomas Muntzer was led astray and before he knew it ploughshares and pruning hooks were being beaten into swords.

John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement— otherwise, kind of a normie guy, he got led astray too. He read a verse— a single verse— in Revelation and came to the conclusion that the apocalypse would be in 1836. Not long after Wesley, a Baptist preacher named William Miller led a movement of believers called the Millerites.

William Miller got more specific than any Christian heretofore had dared. Based on his idiosyncratic reading of Daniel 8, William Miller insisted that the Lord would return (to upstate New York) on October 22, 1844. As it turns out, the most remarkable event that happened on October 22, 1844 was that President James Polk had urinary bladder stones removed. Well, the bladder stones came in second place after what the press dubbed “The Great Disappointment” referring to Miller’s failed prediction. The Great Disappointment didn’t stop William Miller though; his movement of Millerites became known as the Seventh Day Adventist Church.

Christians on cable television went nuts as the year 2000 approached. When Barack Obama became president, Jerry Falwell predicted the End was nigh.

And maybe you recall—

Family Radio host and self-taught Bible expert, Harold Camping, predicted the rapture would happen on May 21, 2011, paving the way for the destruction of the world’s remaining sinners a few months later on October 21, 2011. Harold Camping led hundreds, likely more, so astray they quit their jobs, left their families, sold their homes, and cashed out their 401Ks in anticipation of the end times. As a result, one of Camping's coworkers committed suicide.

“‘Tell us, Teacher, when will this be, and what will be the sign that all these things are about to be accomplished?’”

When it comes to Christ’s Second Advent, there’s a better question to ask than “When?”

When it comes to Christ’s Second Advent, there’s a better question to ask than “When?” Not only is it a better question to ask, it’s a question Christ does not forbid us to ask.

The question we should ask is not “When?” but “Why?”Why has the End with a capital E not yet come?Why has Christ not yet come again?Why does God give more time?Remember—

The Bible is absolutely unique in the history of religion. Unlike the paganism of ancient Rome and Greece, the scriptures do not view the universe as eternal. Likewise, the Bible departs from eastern religions which understand existence as circular, an endless cycling loop of reincarnations. No, the Book of Genesis and the Gospel of John alike claim that creation had a beginning. Before anything was God spoke all that is into existence. Creation had a beginning and, thus, creation will have an end.

Time, according to Christianity, is less like the reliable constancy of grandfather clock and more like the sand in an hour glass.Time will run out.Just as there was a first day, one day there will be a last day. God is bringing history to a head. This is what Paul means when he writes to the Church at Rome, “Your salvation is nearer than when you first believed.” As we pray at the table, one day Christ will come back in final victory, time will be transformed into glory, and we will, as the catechism puts it, enjoy him forever.

Why the meantime?November 26, 2023

The Church is like a 12 Step Recovery Program

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Ephesians 1.15-23

The lectionary epistle for this Christ the King Sunday is from Paul’s letter to the Ephesians.

Here is an old sermon on the text:

A question that gets right to the heart of the Apostle Paul’s rhetoric here in the first chapter of his epistle to the Ephesians.

If God chose us from before the foundation of the worldIf everything has already been done- everything for your redemption, everything for your justification, everything for your salvation- by Christ for youThen why bother?In other words:

If you’re already and always forgiven in Christ, then why bother with Christianity?

Doesn’t that strike you as superfluous as purchasing the service plan at Best Buy? If you’ve no reason to fear fire and brimstone, then what reason do you have to follow?

Because you don’t you know— have any reason to fear.

Fear God or fear for your salvation.

As St. Paul says here in verse 20, Christ has sat down at the right hand of the Father. As the Book of Hebrews puts it, Christ’s sitting down marks the cessation of God’s judgement, for Christ our Great High Priest has offered himself as a perfect, once-for-all sacrifice for your every sin.

Christ has sat down from his work. Never to get up again. And though we still like to the play the judgement game with each other, he’s taken a seat from it and put up his feet, with all our sins forgotten underneath his heels, like a father waiting for his prodigal child to come home.

You are forgiven.

You have no reason to fear.

Because, as Paul says here in verse 23, the pleroma, the fullness, the plentitude, the whole reality of God (without remainder), dwells in Christ Jesus who bore your sins in his body upon the tree.

Pleroma-

You’ve been incorporated in to Christ fully, Paul says, and so you are fully restored to God. You have fullness with God through Jesus Christ in whom God fully dwells.

Fully is Paul’s key boldfaced word here at the end of Ephesians 1.

Fully: there is no lack in your relationship with God.At least— from God’s side there’s not.No other book of the New Testament stresses the completeness of what Christ has done like the Book of Ephesians.

There is no tension in Ephesians between the already and the not yet.In Ephesians, it’s all already.It’s all been done.What he has done for you, it’s fact. And it has nothing to do with how you feel about him. Christ’s incorporation of you has happened- literally- over your dead body, your sin-dead body, when you were buried with him in your baptism.

From Paul’s perspective, “What must I do to be saved?” is the wrong question to ask this side of the cross because you were saved- already- in 33 AD and Christ’s cross never stops paying it forward into the future for you.

Because you are fully in him.

And in him, you are forever safe from the wages of your sin.

He has sat down from his work with all our sins beneath his feet— that’s a sign as obvious as an empty tomb. A sign that God forever rejects our rejection of him.

God literally does not give a damn anymore.But, that begs the question, your question: If you’re already forgiven, once for always and all

If you’re a sinner in the hands of a loving God

If God’s grace is not transactional

If there’s no work you must do to merit it

Then, why bother following?

Why bother giving up your time on a Sunday morning?

Why bother forking over your hard-earned dough into the offering plate?

If we have no reason to fear God, if we are in him and all our sins sit forever underneath his feet, then what’s the incentive to follow Christ?

Why would you bother?

Why would you forgive that person in your life, who knows exactly what they do to you, as many as 70 x 7 times? Why would you do that if you know you’ve already been forgiven for not doing it?

Why bother arguing about welcoming the stranger and caring for the immigrant in your land?

Why all the heartache and anxiety about it if, when you don’t welcome or care for them, Christ is only going to say to you what he says to the woman caught in sin: I do not condemn you?

What’s the point?

What’s the benefit to you?

If you’ve no reason to fear Christ, if you’ve nothing to earn from him that isn’t already yours, then why bother following the hard and peculiar path laid out by Christ?

Earlier this week, I rewatched this little documentary from 2011 about Delores Hart.

Delores Hart was an actress in the 1950’s and 60’s. Her father was a poor man’s Clark Gable and had starred in Forever Amber. She grew up a Hollywood brat until her parents split at which time she went to live with her grandpa, who was a movie theater projectionist in Chicago.

Delores would sit in the dark alcove of her grandpa’s movie house watching film after film and dreaming tinseltown dreams. After high school and college, Delores Hart landed a role as Elvis Presley’s love interest in the 1956 film Loving You, a role that featured a provocative 15 second kiss with Elvis. She starred with Elvis again in 1958 in King Creole.

She followed that up with an award-winning turn on Broadway in the Pleasure of His Company. In 1960 she starred in the cult-hit, spring break flick Where the Boys Are, which led to the lead in the golden-globe winning film The Inspector in 1961.

Delores Hart was the toast of Hollywood. She was compared to Grace Kelley. She was pursued by Elvis Presley and Paul Newman. Her childhood dreams were coming true. She was engaged to a famous L.A. architect.

But then-

In 1963 she was in New York promoting her new movie Come Fly with Me when something compelled her- called her- to take a one-way cab ride to the Benedictine abbey, Regina Laudis, in Bethlehem, Connecticut for a retreat.

After the retreat, she returned to her red carpet Hollywood life and society pages engagement but she was overwhelmed by an ache, a sensation of absence.

Emptiness.

"I had it all, everything really, but my life wasn’t full,” she says in the documentary.

So, she quit her acting gigs. She got rid of all her baubles. And she broke off her engagement. She renounced all of her former dreams- and joined that Benedictine convent where she is the head prioress today.

What’s more remarkable—’What’s more remarkable than her story is the documentary filmmakers’ reaction to it, their appropriation of it.This is HBO remember, the flagship station for everything postmodern, postChristian, purient and radically secular.

Here’s this odd story of a woman giving up her red carpet dreams and giving her life to God, and the filmmakers aren’t just respectful of her story; they’re drawn to it.

They’re drawn into it. They’re not just interested in her life; they’re captivated by her life. Even though it’s clear in the film that her motivation- her life in Christ- is a mystery to them, you can tell from the way they film her story that they think, even though she wears a habit and has no husband or family or ordinary aspirations, they think her life is captivating, that believing she is God’s beloved and living fully into that belief has made her life not just captivating but beautiful.

You can tell these Hollywood have-it-alls, they suspect that maybe she is somehow more human than they are.More fully human.

That’s why-

Why we follow even though there’s nothing for us to fear.

Why we bother even though there’s absolutely nothing we need to earn we’ve not already been given by grace.

We are fully in him, that’s true— fully forgiven, with no more we must do, with no reason we ought to fear.

We are fully in him.But we are not fully like him.I know I’m not, and neither are you, not by a long shot.

We are fully in him but we are not fully like him.

And if he is the image of the invisible God, as Paul says in Colossians, then what it means for us to be made in God’s image is for us to resemble him.The image of God is not ours innately, by nature; it’s ours by imitation.If he is the first born of creation, the first fruit of the new creation, as Paul says in Corinthians, then what it means for us to be a human creature is for us to look like and live like him.

If he is the Second Adam, as Paul names him, then he is who we were meant to be all along from Adam on down. If the fullness of God fills Jesus Christ, if Jesus is what God looks like when God fills our flesh with himself and becomes fully human- totally, completely, authentically human- then we follow Jesus not because we hope to get into heaven one day but because we hope one day to become human.

We do the things that Jesus did not because we’re commanded to do the things that Jesus did.

No.

The Gospel, declares Galatians, is that Christ has set us free from the Law. His obedience has freed us from the burden of obeying the commandments, even his commandments.

So don’t you dare give me that verse about the sheep and the goats because the Gospel is that the Good Shepherd became a goat so that a goat like you might be counted among his faithful flock.

Christ has set us free from any anxiety about obeying the commandments, even his commandments.

We do the things that Jesus did not because we’re commanded to do the things that Jesus did.

We do the things that Jesus did because Jesus did them.

And his is what a fully alive life looks like.

The reason Christ’s yoke does not feel easy nor his burden light, the reason we’re daunted by forgiving 70 x 7, and intimidated by a love that washes the feet of strangers and enemies is that we’re not yet, fully, completely human.

As human as…God. We get it backwards.It’s not that God doesn’t understand what it is to live a human life; it’s that we don’t. We’re the only creatures who don’t know how to be the creatures we were created to be.Before it’s anything else, the Church- it’s the ultimate recovery program.

It’s a community for all of us addicts hooked on the highs of our un-human habits. And just as in AA, the first step is admitting you have a problem. Or, as St. Paul puts it: “While we were yet sinners…” The Church- before it’s anything else, it’s a recovery program. Where once a week we’ll hand a self-involved narcissist like yourself a cup of coffee and force you (with hymns and stained-glassed language) to confront the fact that you are not the center of the universe.

We call that step “worship.”

The Church- it’s like a 12 step recovery program.

Fo you with your log-jammed eyes, content to let the sun go down on your anger, we have a step called “confession and pardon.” Don’t kid yourself, it’s not for God to forgive you- you’re already forgiven. It’s for God to make stubborn unforgiving you a more forgiving person; that is, more fully human.

For you addicted to the tit-for-tat way of this un-human world, we’ll force you to do something odd called passing the peace.

For you who is a junkie to the delusion that what you have is yours by your own doing, we’ll pass you not the peace but a plate where you will recover a creature’s sense of gratitude to the Creator from whom all blessings flow.

For you who are anxious about accruing not just for tomorrow but for the next day and the day after that and the day after that and the day after that, we’ve got a prayer (not about serenity) about daily bread.

For you hooked on the high that comes from the illusion that you are responsible for this world, we’ve got the same prayer.

It goes “Thy Kingdom come…” in order to teach thou that its not your Kingdom to bring. Or, even, to build. For you used to using your talents to take and make, we have this table of wine and bread, where all you can do is receive.

And by the way, it’s a table reserved not for the best and the brightest but for betrayers- learning that is a hard step on the path to recovery too. We’ve got other steps too, like rolling up your sleeves and serving your neighbor so that you can no longer convince yourself that God is the stuff of idle, pious speculation because you’ve met Him in them, just as He promised you would.

Before it’s anything else, the Church is a recovery program where you learn through word and sacrament and service to say “Hi, my name is Jason and I’m a sinner who needs Jesus.”

When Delores Hart took her finals vows as a Benedictine nun, 7 years later, she wore the dress she’d bought for her red carpet Hollywood wedding. She thought the wedding dress was the perfect sign to others that fullness of life comes not from the things with which we so often try to fill our lives: career, children, relationships, riches, reputation, success.

She thought the wedding dress was the perfect sign for others of where- in whom- fullness of life was to be found.

And were that it, it’d be a nice uplifting story, right?

The perfect sort of slice of life story to end a sermon.

Except, St. Paul says that at your baptism you were clothed in the wedding garment of Christ’s own righteousness.

And here in Ephesians Paul says not only that Christ was fully God and that you are fully in him but that you are fully him. You are his Body.

He has no other Body but you the baptized.

In other words:

By virtue of your baptism, you’re wearing Delores’ wedding dress.

Which makes you not just an addict in recovery.

It makes you a sponsor.

For the sake of others.

For the sake of them finding their full humanity.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 23, 2023

Even in the Eschaton, We Must Say Thanks

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

“All sacrifices, everything that's written about in the Hebrew Bible will be abrogated. None will require our attention except one, the Hodah, the Thanksgiving sacrifice. I think it's a profound lesson that even when everything is perfect, which it will be when the Messiah comes again. We have to say thank you.”

Happy Thanksgiving to all of you in this community.

Here is the latest installment in a new friendship for which I am grateful this holiday. To begin, Rabbi Joseph talks about the sacrifice of thanksgiving abiding even in the eschaton.

I’ve included an article on archaeologists working to identify remains in Israel after the 10/7 massacre by Hamas:

Wearing gray gloves and with a soot-blackened face, Dr. Joe Uziel shakes the thin mesh screen, which rests on four legs and has a tub-like receptacle underneath. His movements recall the sifting of flour or separating wheat from chaff.

Uziel is not a miller or farmer, though. He’s an archaeologist, the head of the Dead Sea Scrolls unit in the Israel Antiquities Authority, and the tool he’s using is an archaeological sifting screen to separate tiny fragments from soil. 'We are working according to archaeological methods of uncovering strata. But we’re not sifting through strata that are tens of thousands years old.'

The sifters team of sifters he oversees spread out on the partially trampled lawn of Nir Oz, opposite several one-story buildings that were destroyed or burned along with their occupants during Hamas’ October 7 assault on the kibbutz and other nearby communities.

Dr. Joe Uziel in kibbutz Nir Oz, this week. 'This is a difficult task for us emotionally, but important professionally.'Credit: Yossi Melman He and the reservist troops who have been assigned to assist him have a sacred mission: trying to identify the possible remains of any missing victims. “This is a difficult task for us emotionally, but important professionally,” he says. “We enter the burned houses, collect the ashes, and try to find fragments of teeth or bone or any part or item that could help with identification.”

Israel's dead: The names of those killed in Hamas massacres and the Israel-Hamas war Families of Muslim hostages held by Hamas: 'This isn't a religious war' Nir Oz wasn't a battle, It was a systematic massacre Oren Shmueli, his teammate, says, “We are working according to the archaeological methods of uncovering strata. But this time, we’re not sifting through strata that are thousands or tens of thousands years old, but rather from just the past weeks, made of houses whose roofs collapsed and rooms that imploded.”

The archaeologists arrived in Nir Oz after working in the kibbutzim of Be’eri, Kissufim, and Kfar Azza and the convoy of destroyed and abandoned cars from the Nova Music Festival beside Re’im. Their findings are sent to the Shura military base south of Ramle, which serves as a center for the Military Rabbinate and the National Center of Forensic Medicine. The scientists there extract DNA from the findings and cross-check against the database of names of those still missing since the attack.

An empty dining table at Nir Oz's shared dining hall with posters of kibbutz members who are missing following the Hamas attack.Credit: Yossi Melman. The devastation at Kibbutz Nir Oz after Palestinian terrorists infiltrated the kibbutz, murdered many of its inhabitants and burned down their homes.Credit: Hadas Parush Uziel and Shmueli say that the archaeologists’ devoted efforts have led to the identification of 10 victims, allowing them to be declared deceased and brought to burial.

The kibbutz dining hall is just a two-minute walk from where Uziel is working. It’s remained practically untouched since Black Saturday, with shattered dishes, bits of food, and ripped towels soaked with congealed blood still on display, sounding a silent yet piercing howl for the slaughtered, kidnapped, and missing. This is where journalists, primarily from the foreign media, have been brought to bear witness.

Nir Oz, was founded on the Gaza border in 1955 by the Hashomer Hatza’ir movement. Relative to its population, it suffered one of the deadliest attacks on communities in the south. More than a quarter of its population of 400 fell victim – 38 people were murdered and 75 abducted (nearly a third of the total number of hostages), including 16 children; two additional hostages, Yocheved Lifschitz and Nurit Cooper, have been released by Hamas a few weeks ago. Kibbutz spokesman Nitai Ladani says the kibbutz has decided not to distinguish between the hostages and the missing.

In the communal dining hall, the chairs have been covered with white cloths with the pictures and names of those killed and taken hostage attached, making the dimensions of the devastation wreaked on the kibbutz all the more palpable.

Natalie Madmon, sitting next to a picture of her mother, 77-year-old Ophelia Roitman, who is among the Hamas hostages. I was accompanied on this tour by Natalie Madmon, who sat down on the chair with a picture of her mother, 77-year-old Ophelia Roitman. A mother of three and grandmother of nine, Ophelia is among the hostages. “My mother was a teacher her whole life,” says Natalie. “She loved life and she loved the kibbutz and she was a woman of peace.”