Jason Micheli's Blog, page 54

January 16, 2024

The Season of Theophany

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

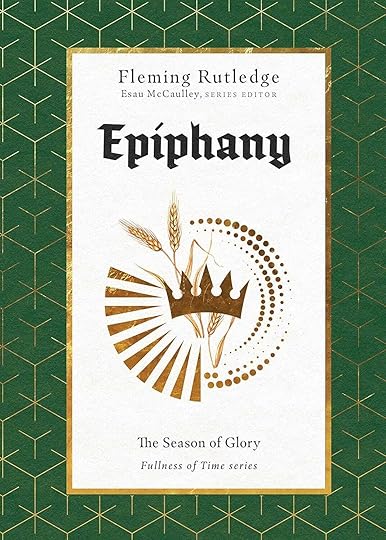

Here is our first conversation on Fleming Rutledge’s Epiphany, in which we discussed the concept of glory and its connection to the season of Epiphany.

We explored the significance of the liturgical calendar and how it helps the people of God order their time around the person and work of Jesus Christ. The conversation delves into the nature of glory and its relationship to God's being. We also discussed the importance of recognizing Jesus as the full revelation of God's glory and the transformative power of beholding God's glory. We reflected on the gift of faith and the humility required in approaching faith. We also explored the connection between glory and grace, as well as the role of the church in proclaiming the glory of God. In this conversation, we discussed various themes related to the season of Epiphany. We explored the significance of the book 'The Last Temptation of Christ' and its portrayal of Jesus' humanity and divinity. We also touched on the Council of Chalcedon and the challenge of holding the paradox of Jesus' nature. The parable of the sower is discussed as a reflection of the gift of Christ and the different responses to it. The weight and radiance of Jesus' glory are highlighted, along with the silent and transformative gift of God. The conversation concludes with a focus on the church's role in narrating God's work and the disarmingly glorious humanity of Jesus.

TakeawaysThe liturgical calendar helps the people of God order their time around the person and work of Jesus Christ.

Jesus is the full revelation of God's glory, and beholding him can transform us.

Faith is a gift, and it should be approached with reverence and humility.

The glory of God is often revealed in ordinary and mundane moments. Epiphany is a season that invites us to hold the paradox of Jesus' divinity and humanity.

The parable of the sower reminds us of the gift of Christ and the different responses to it.

Jesus' glory is both weighty and radiant, and it is given silently and in unexpected ways.

The church's role is to narrate God's work and invite others into the story of Jesus.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the appChapters

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the appChapters00:00Introduction and Opening Remarks

04:22The Season of Epiphany and the Liturgical Calendar

09:36Understanding the Glory of God

12:14Exploring the Concept of Glory (Doxa)

13:41The Relationship Between Glory and God's Being (Asaity)

16:19The Glory of God as Manifestation

18:02Jesus as the Full Revelation of God's Glory

19:32The Transformative Power of Beholding God's Glory

20:41Theophany and the Connection to Jewish Liturgical Calendar

23:37The Importance of Recognizing Jesus as the Son of God

25:42The Danger of De-Glorifying Jesus

27:32The Gift of Faith and the Humility of Belief

31:49The Reverence and Humility in Approaching Faith

34:37The Connection Between Glory and Grace

37:04The Glory of God Diminishing Us

40:35The Glory of God and the Work of Transformation

43:48The Relationship Between Glory and Grace

46:09The Gift of Faith and the Sacredness of the Story

50:19The Ordinary and Mundane Nature of God's Glory

51:28The Continuity Between Epiphany and the Cross

51:58The Last Temptation of Christ

53:25The Council of Chalcedon

54:54The Challenge of Holding the Paradox

55:44The Parable of the Sower

57:16The Weight and Radiance of Jesus' Glory

58:14The Silent Gift of God

59:41The Accomplishments of Jesus

01:00:40Breaking Down the Dividing Wall of Hostility

01:01:38The Church Narrating God's Work

01:02:37The Disarmingly Glorious Humanity of Jesus

01:04:13Chapters Three and Four Next Week

01:05:21The Special Emphasis of Epiphany

January 15, 2024

“Something Impossible for Unaided Humanity”

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Happy MLK Day Friends,

Our online class resumes tonight at 7:00 EST. For the next five Mondays of the Epiphany season, we will be discussing Fleming Rutledge’s new book, Epiphany: The Season of Glory.

We will work our way through the book two chapters at a time.

Panelists will include the posse from previous Monday night session: Todd Littleton, Josh Munnikhuysen, Tony Robinson, Kelly Watts, and Johanna Hartelius. Fleming says she hopes to be able to join us sometime too.

You can still sign up to join us live in the Zoom webinar here.

As a supplement to our discussions, my friend Josh Retterer will be writing brief reflections for us along the way.

Here is his initial post:

The newly installed pastor tossed the copy of Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion – gifted the previous week – onto the pew beside me. The dreaded Elvis lip curl of disdain wasn’t what I was expecting as he mumbled a couple of words that may have been “thank you.” The whole encounter felt rather Lynchian; the awkward fast-walk away really selling it. Everything was red flags and sirens and flashing red lights— even the flashing lights were waving red flags. I never did find out why he returned it, what his objections were to it, or to me. If you can’t talk about The Crucifixion with your pastor…

As you can see, Rev. Rutledge can produce some strong reactions, but so can the Crackers & Grape Juice folks! Matter of fact, I found Crackers & Grape Juice because of Fleming Rutledge. I heard her interviewed on The Mockingcast about her then new book, and had to find more! I soon found Crackers & Grape Juice’s Fridays with Fleming, which were/are some of my favorite episodes. Rev. Rutledge’s clarity about the gospel is so refreshing, mainly because it’s rarely heard. She talks about Christ’s power to save so freely, with a palpable sense of both joy and awe, that you can’t help but be affected. She isn’t on the bleeding edge of experimental theology, which often feels like the process of removing the necessity of Jesus from Christianity. Rev. Rutledge unapologetically preaches and writes about the faith once delivered, of which Christ is central. She has spent a lifetime pointing the same direction. Why? There is nothing else more important.

So, when Rev. Rutledge writes an entire book on Epiphany, and calls it, Epiphany –again, it must be important. I tend to trust where she points. From the very first chapter, Jesus is front and center.

“The glory of the love of Jesus is not the same as human love, because his glory is something that is impossible for unaided humanity: namely, it is able to triumph over all that would destroy it. The body of Christ needs to recommit to this concept of the glory of God. It has been in semi-eclipse of late, as Jesus has been presented as a moral exemplar, social activist, and religious teacher minus his unique identity as Son of God. Perhaps the very word glory seems bombastic to some, for reasons similar to recent attempts at eliminating the idea of Jesus as “Lord.” However, the glory of God and the lordship of Christ are too central to the biblical message to be pushed to the side in the church’s witness. In particular, the glory of God needs to be recovered as a preaching theme if we are to seek a more obviously revelatory way of proclaiming Christ. The Epiphany season, with its narrative arc shaped by manifestations of Jesus’ uniquely divine identity, is well suited to this project.”

This week we will explore, in part, this recovery project, why it’s vital, and ways they attempt to do the same in their own churches and ministries.

Thanks for joining us!

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 14, 2024

The Boy Who Lived

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

1 Kings 17.16-24

Over twenty years ago, I was part of a captive audience for a class on preaching at Princeton. I was captive in the worst kind of way, because this belligerently confident, hyper-evangelical classmate preached his “sample sermon” before the students in the homiletics class.

His sermon was a lot.

Throughout the entire twenty minute sermon our homiletics professor, Dr. James Kay, looked restless and irritated. And once the sermon was finally over Dr. Kay looked exasperated. It was not the reaction the beaming student preacher had anticipated. The professor was an amateur boxer and he appeared suddenly like he was squaring up against an opponent.

“Do you realize,” Dr. Kay thundered with genuine offense, “not one of your sentences had God as their subject!”

The point seemed lost on the preacher.

“God was not the subject of any of the verbs in your sermon,” he explained. “If the word works what it says, if the preaching of the word of God is the word of God, then you don’t need any “I’s” in your sermon. The Lord is the subject of every sermon. Let the Living Word have its way with you.”

It was a mic drop moment before mic drops were memes.

Though seldom do I practice what Dr. Kay preached that afternoon— here I am, caught in the act, telling one of my stories— I’ve never forgotten the lesson.

I felt liberated to hear that there need not be any I’s in the sermon (my stories, my spiritual experiences, my religious insights, my— God forbid— advice) in the sermon— not if the Living God is a God determined to reveal himself, at work through his word to bring us to himself.

The Lord is the subject of every sermon.

Let the Living Word have its way with you.

The reason we must be diligent about keeping the main thing the main thing in the church is because the good news is that you are not the good news. I am not the good news. Neither Joe Biden nor Donald J. Trump are the good news.

Jesus Christ is the good news.

The Lord Jesus is not dead.

And he is up to something in the world.

The grammar of the gospel is essential.

We are the objects the Lord acts upon.

Arguably there is no better passage of scripture to buttress Professor Kay’s point than the story of Elijah. The Book of Kings is an ironic title for the narrative it tells, for Israel’s kings and the world’s power brokers are impotent bystanders to the power and purpose of the word of the Lord. Read properly, the story of Elijah is not even the story of Elijah.

The Book of Kings repeatedly refers to Elijah not as a prophet but as a Man of God, and the preposition of possession is quite literal. Yahweh is not Elijah’s copilot; Elijah is the vehicle for the Lord’s purposeful activity. In the fullness of time, when a pall of idolatry and corruption had enshrouded the promised land, the Lord plucks un-credentialed, unprepared, unqualified Elijah from obscurity in Gilead and the Lord thrusts him into Ahab’s oval office. After Elijah proclaims the word the Lord has given him— just like the Spirit flings Jesus into the desert to be tempted by the devil— God propels the prophet out into the pagan wilderness.

With the sky shut up and the fields fallow, Ahab sends soldiers to scour the land for the Man of God whose word struck like a fever into the heart of the earth. Jezebel dispatches her spies from Sidon. Even though Elijah sojourns in Jezebel’s own territory, no harm comes to him. The Lord protects him. He is the exception to the judgment that falls upon all. All of Israel suffers drought and famine. But every evening and every morning the Lord satisfies Elijah’s hunger and slakes his thirst. Just as the Lord fed Moses manna and quail, every day the Lord offers Elijah meat by means of ravens and water from the Wadi Cheri.

The Living God is the subject of all the verbs.Once the Wadi dries up— because, by the Lord’s word, there has been no rain— the word of the Lord comes to the Man of God and hurls him to Zarephath to the house of a widow, whom the Lord has preveniently commandeered to his cause. She knows his name before he shows up.

In the Bible, widow is shorthand for bottom of the ladder, without either hope or future. Needless to say, in a pandemic of drought and famine, a widow is the least likely person to have the resources to provide for the prophet Elijah. She had less on her shelves before God’s judgment fell across the land.

The widow confides to the Man of God that, just then, she had been gathering sticks to cook for her son. Like a prisoner on death row, with only a handful of flour left and a couple of tablespoons of olive oil in the jug, this would be her last meal. “I am now gathering a couple of sticks,” she says, “so that I may go home and prepare it for myself and my son, that we may eat it, and then die.”

As the angel Gabriel to Mary, Elijah issues a command only God can command, “Do not be afraid.” Just so, for months the flour and oil are like manna in the wilderness. The Lord feeds them. The Lord shelters them from the the shut up sky and the shriveled earth. The Lord keeps them until he once again sends rain upon the earth.

God gets all the verbs.Meanwhile—Ahab and Jezebel, the president and first lady, are incidental to the action.They accomplish nothing.Kings are supposed to provide food and water. Presidents are supposed to provide stability and security. Leaders are selected to protect their people from all enemies, foreign and domestic. But Ahab is impotent in his attempts to arrest the famine. The administration’s attempts to capture Elijah are ineffectual— the prophet sneaks across the porous border. The desperate situation reveals Ahab’s government to be dysfunctional and discredited, without the ability to remedy what ails the nation. Any of Ahab’s subjects would be right to read the newspaper and despair over the future of their nation.

Unless God is the subject of verbs.

Despair is the most rational disposition in the world— nihilism is the sanest, most honest philosophic position— if God is not up to something in the world.

Shortly after he transitioned from parish ministry to university teaching, the theologian Karl Barth learned that many of his fellow faculty members at the University of Bonn in Germany had become enthusiastic members of the fledgling Nazi movement, including— especially— the professors in the department of homiletics.

Though he had taken his position on the condition that he would abstain from political activity, the Lord told Barth that students of preaching should not learn preaching from those whose preaching had been corrupted by nationalism and populism and racism and xenophobia. "How can they proclaim the gospel,” Barth asked, “when their teachers know not that Jesus is Lord?” And so a year before the Reichstag fire election ushered a different Ahab to power, Karl Barth began teaching an unofficial, uncredited, underground series of lectures on homiletics.

A book based on his students’s notes was later published under the title, The Preaching of the Gospel. In his instructions for the “actual preparation of the sermon,” Barth infamously rails against sermon introductions:

“Basically the sermon should not have an introduction…[all rhetorical strategies at the beginning of the sermon] are to be rejected in principle.”

What is the principle?

The principle that listeners can only hope to hear a word from God if God speaks.

Deus dixit.

Our only hope, Barth insisted, is that the Word is up to something in the world. “For what do introductions really involve at root?” Barth asked his students:

“Nothing other than the search for a point of contact [between the listener and the word of God]. It is believed that this little door must be opened first before it is worthwhile to bring a message…Nein! This is plain heresy…If we understand the Bible after the manner of the Reformers, we know that no such possibility for a point of contact exists. There is only one exception, the contact which is made, of course, by the miracle of God on high.”

If they’re going to hear a word from the Lord, then it’s not because you’ve prepared them to hear but because Jesus Christ has elected to speak.

So, just get on with the sermon!

In other words—

God is more than the subject of the sermon.He is the acting subject in the sermon.If you grasp Barth’s point, then you see it’s not really about sermon preparation at all. It’s every bit about his fellow faculty members who fell, enthralled, under the spell and spectacle of the Ahab of their day.

Barth rejected introductions and all other rhetorical devices as a way of reminding his students that no matter what was going on in the capital, no matter what the headlines said, the Lord was surely doing greater works through his word.

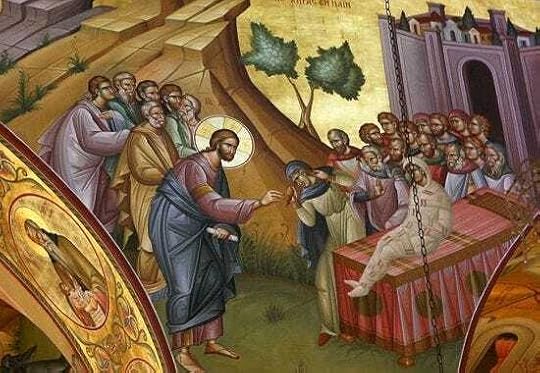

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus enters a town called Nain. He’s followed by a great crowd. As Jesus and the crowd approach the city gate, they collide with a crowd trudging mournfully in the opposite direction out of the city. They see pallbearers carrying the body of a boy, a widow’s only son.

Death is like that in the Bible. The work of God and God’s people advances forward and then, inexorably, it collides into Death. Death, the apostle Paul writes, is always a malevolent intruder, a cohort to the Power of Sin, the Enemy. As in, the Enemy; Death in scripture is synonymous with the Prince of Lies.

Ahab may have been ineffectual, but Death is not so impotent.

After months of manna-like miracles, Death intrudes in Zarephath. Death collides against the bulwark the Lord has erected around the Man of God. From the widow who has next to nothing, the Enemy takes her boy.

The subject of the sentence.

Death gets a verb.

And we know he was a little boy because she picks him up and she carries him over to Elijah and she holds his limp body out to the prophet as evidence of her indictment, “What have you against me, O man of God? You have come to me to bring my sin to remembrance, and to cause the death of my son!” The widow thinks her proximity to the Man of God has brought under divine inspection.

Your God has done this to him because of me, my sin!

With the same audacity he displayed in Ahab’s council chamber, Elijah responds. He takes the boy from her bosom. He carries the boy up to the upper room. He lays him on the bed.

And the prophet prays to the Lord who has rested on his lips.

In the midst of his prayer, the Man of God offers an odd act. Mind you— corpses are intensely clean; they are contagious with their uncleanness. But the righteous Man of God stretches out his body to cover completely the unclean body of the dead boy.

Three times he does it.

Almost like Jesus covering you completely.

Covering your sin with his permanent, perfect record.

With water and the Spirit.

Three times.

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

The Man of God covers the unclean corpse with himself.

And then, as simply as Jesus says to Jairus’s dead daughter (“Talitha cumi”), Elijah says the widow, “Your son lives.”

In the second century, a theologian named Marcion contended that the God of the Old Testament could not possibly be the Father of the Lord Jesus Christ. Though Marcionism was promptly dismissed as a heresy, it has stubbornly abided in the church like a weed. In all likelihood, you have watered that weed at some point with your words.

Marcion was condemned in part because of the straightforward reading of passages like this one in the Old Testament. Quite obviously, the Word who arrests Elijah’s life and rests on Elijah’s lips is the same Word who overshadows Mary’s belly. This passage is the gospel before the Gospels. The Word commandeers Elijah and crosses the boundary into the wilderness— just like Jesus. The Word hijacks Elijah and crosses the boundary into territory held by the Enemy— just like Jesus. The Word covers over uncleanness with his own body and crosses the boundary into Death to bring a sinner back— just like the Lord Jesus Christ.

The Word of the Lord who comes to Elijah is Jesus.

And this should not surprise us.

Fact is:

Jesus never meets a corpse that does not rise.The widow of Nain’s son.

Jairus’s daughter.

Mary’s and Martha’s brother, Lazarus.

And here in Zarephath.

Of course, the widow’s boy rises from the dead.The word of the Lord on Elijah’s lips when he prays over him is Jesus.They all rise from the dead.

The widow’s son, Lazarus, Jairus’s girl, Nain’s son— they all rise not because Jesus does a number on them, not because he puts some magical resurrection machinery into gear, but simply because Jesus has that effect on Death.

They rise because he is Resurrection.He is both subject and verb.Meanwhile, King Ahab— Elijah is safe, Elijah is fed. Elijah has saved a son from death— is utterly absent from the drama.

Which is to say, you can be so preoccupied with presidents and politics that you miss the power of God at work in the world.

During the pandemic, I paid a pastoral call to an eighty something man from the neighborhood who called the church office worried that “when the virus finally gets here, I’m exactly the kind of geezer who will have a bad go of it.”

He asked me to come visit him and “do more than shoot the breeze.”

While he made instant coffee, I looked at the flag he had hung on the wall, folded and framed in a wooden triangle. Photographs of a younger man surrounded it. I started to ask him a question but he waved me off. He had something he wanted to get off his wheezing chest.

He was a Vietnam vet, he told me. The cancer that was killing him slowly likely came from the Agent Orange that killed others. Then he corrected himself, “That I killed others with.”

I nodded.

He handed me a mug of Folgers and gestured for me to sit down.

“It’s been weighing on me for a while,” he said, “but then when this plague struck, I thought I shouldn’t waste any more time.”

I took a sip and looked at him, unsure where this was headed.

“I want to confess, I guess” he told me staring at the steam coming off his coffee, “what I had to do in the war— it was necessary, maybe, but it was still sin.”

And so he confessed.

Before he was done, he was weeping like a widow.

I put my mug down on the coffee table. I stood up from the recliner. I made the sign of the cross on his forehead and I said, “Vince, in the name of Jesus Christ and by his authority alone, I declare unto you the entire forgiveness of all your sins.”

I waited until his eyes were dry before I stood up to leave.

He had been dead in his sins.In the middle of a pandemic, with the nation bitterly divided over who would sit in Ahab’s Oval Office, God had just raised the dead to new life.By grace.

Notice—

The widow of Zarephath believed in God. She had been on the receiving end of a manna-like miracle for months. But she didn’t know God. She didn’t know God is a God of grace. When Death collides with her life, she assumes the Lord has slain her son to punish her for her sins.

Your God has done this to him because of me, my sin!

Notice too—

Elijah has no reply for her. He doesn’t know whether God has taken her child as a punishment for sin. He asks that very question in the first part of his prayer. Elijah doesn’t yet know God is a God of grace. It’s as though the only way you can be certain of God’s grace— the only way you can truly know God and God’s heart and God’s character— is if you have witnessed the Lord raise the dead to new life.

In other words, you need an empty tomb.

“Grace, grace, grace. I get it,” a listener griped to me after I had preached here for about year, “I get it. When are you going to move on and preach a different message?”

“I’ll stop preaching grace,” I said, “when you actually start believing it.”

“I do believe it!” She said, “It’s not that hard to understand!”

Really? Bless your heart.

Four years later— last February— she braced me in the fellowship hall, wanting to know my take on the alleged awakening that was sweeping Asbury University in Kentucky. What had begun as an ordinary Wednesday morning chapel service at a small college, far away from any place important with far more urgent matters going on around the world, turned into a multiweek Outpouring of the Holy Spirit that drew young people from hundreds of other colleges and universities, some from as far away as Japan and Russia.

“You don’t really believe that’s a revival, do you?! You don’t really think the Holy Spirit is responsible for whatever has swept over those kids, do you?!”

I stammered that I wasn’t sure, that I didn’t know enough about it, that I’d have to learn more.

She shook her head, as dissatisfied as she was certain:

“At Asbury of all places? You really think the Holy Spirit would work a miracle at Asbury? Don’t you know Asbury’s politics? It’s in the reddest of red states! Asbury is one of the main antagonists in the fight in the United Methodist Church. They’re not even real Methodists— they’re evangelicals. They’re for Trump. They’re against inclusion. They’re the bad guys as far as I’m concerned. There’s no way God would work a miracle among them.”

“Well,” I said, “Now that you’ve put it like that I guess I’d say, ‘Yes, that sounds exactly like something a gracious God would do.’”

After he’s tempted in the wilderness, Jesus preaches his first sermon. For his hometown synagogue, Jesus preaches from the Book of Isaiah. Once Jesus finishes the sermon, the congregation immediately “spoke well of him and marveled at his gracious words.” That Jesus was from Nazareth they took as a sign that God was on their side.

So Jesus grumbles, “Doubtless…you will demand that I do here in my hometown for you what you have heard I did in Capernaum.”

Right then the self-satisfaction starts to disappear from their faces. And just before they’re filled with wrath and try to kill Jesus— try to throw him off a cliff— Jesus preaches grace one more time.

“Remember,” Jesus says, “there were many widows in Israel in the days of Elijah. It didn’t rain for three and a half years— famine gripped the whole land. There were many widows in Israel in those days. And there were many mothers with dead children. And what did God do? Did Yahweh send Elijah to a single one of those Jewish widows in need? Did God raise any of their starved children from the dead? Did the God of Israel roll up his sleeves and show up for the people whose side he was supposed to be on? Elijah was sent nowhere else but to Zarephath in the pagan land of Sidon, to a gentile widow outside the promised land.”

They hated the message of grace so much they tried to kill him.

But Jesus got the grammar straight.

Elijah was sent.

It’s passive voice, but flip it around and God is the subject of the verb.

So come to the table.

The Risen Christ is the host.

He invites you.

He wants to give himself to you.

It’s easy to miss if you’re looking in the wrong places.

It’s easy to miss if you’re preoccupied with the wrong people and powers.

The Lord is at work in the world.

Here.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 13, 2024

The Dangerous Lure of Hot Takes

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

SummaryIn this conversation, Rabbi Prof. Joseph Edelheit and I explore the challenges of engaging in interfaith dialogue and addressing complex issues. We discuss the importance of patience, asking questions, and embracing complexity over certainty. We delve into the complexities of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the misuse of words, and the need for shared vocabulary. We also examine the role of idolatry in modern society, the challenges of monotheism and exclusivity, and the importance of caring for the public. Throughout the conversation, we emphasize the need for humility, engagement, and the recognition of the not yet-ness of certain issues.

TakeawaysEmbrace complexity and patience in interfaith dialogue, avoiding the temptation of certainty.

Engage in conversations with a shared vocabulary and understanding, respecting the complexity of different perspectives.

Recognize the challenges of monotheism and exclusivity, and strive for inclusivity and understanding.

Avoid the allure of idolatry in modern society, such as the idolatry of certainty and public performance.

Take responsibility for caring for the public and engaging with complex issues, while recognizing the not yetness of certain solutions.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the appChapters

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the appChapters00:00Introduction and Setting the Context

02:19The Importance of Patience and Asking Questions

03:16Addressing Misuse of Words and Certainty

04:07Responding to Comments with Complexity

05:29Understanding the Devastation in Gaza

06:15Personal Stories of Tragedy and Complexity

07:51The Complexity of Sabbath Services in Israel

08:12Embracing Complexity in Interfaith Relations

09:18Distinguishing Hate for Jews and Criticism of Israeli Government

10:00The Historical Context of Israel and Palestine

11:48Setting Boundaries in Dialogue

12:20The Complexity of October 7th and Moral Equivalency

13:26The Challenges of Monotheism and Exclusivity

14:17The Church's Role as Moral Arbiter

16:17The Uncertainty of the Times We Live In

17:46The Need for Shared Vocabulary and Understanding

18:40The Siloed Nature of Information Sources

19:27The Challenge of Certainty and the Church's Formation

20:01The Tension Between Pluralism and Exclusivity

21:07The Flaw in Monotheism and Exclusivity

22:31Idolatry in Modern Society

23:41The Role of Religion and Spirituality

24:06The Challenges of Serving as Clergy

25:06The Not Yetness of Institutional Promises

26:19The Temptation of Idolatry in Modern Life

27:50The Allure of Certainty and Public Performance

29:09The Importance of Revering the Old Testament

30:32The Over-Specialization of Scripture Studies

31:36The Loss of Shared Vocabulary and Dialogue

33:17The Inscrutable Nature of God's Name

35:11The Mystery and Complexity of Scripture

37:07The Idolatry of Certainty and Rapidity of Life

38:49The Danger of Disinformation and Denial of Reality

40:19The Complexity of Elijah's Mission

41:57The Aspirational Promise of Elijah

44:32The Need for Humility and Engagement

45:57The Fear of Anti-Islam Sentiment

48:20The Responsibility to Care for the Public

49:30The Importance of Time and Reflection

51:15The Need for Accountability and Complexity

52:10The Promise of Unity and the Not Yetness

January 12, 2024

The LORD Speaks by No Other Word But Jesus

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming joining the posse of paid subscribers.

1 Samuel 3:1-10, (11-20)

In the lectionary for this coming Sunday of Epiphany, the Old Testament text is 1 Samuel 3. To my mind, the most auspicious but least noticed feature of the passage is verse 7: “…and the word of the LORD had not yet been revealed to him.”

It’s critical we understand that locution. And it’s essential we hear it in the context of the Gospel’s prologue: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” If we do not, then Christians have neither the reason nor the right to read Israel’s Bible as also our scripture.

When the Old Testament tells us that “the word came to…” it does not mean that the Father sent some words to one prophet or patriarch and then sent another batch of words to another prophet or patriarch.If that’s what it means, then, for Christians, the documents which comprise the Old Testament are nothing more than interesting historical background and cultural context for the New Testament.Of course, this is all the Old Testament is for a great many— maybe most— Christians.

But this is not what “the word of the Lord came to…” means.

When the Old Testament tells us that the word of the Lord came to Jacob, when the Old Testament reports that the word of the Lord came to Isaiah son of Amoz, when the word of the Lord came to Elijah, saying ”Go and present yourself to Ahab, and I will send rain upon the land,” the word of the Lord in the Old Testament is the word incarnate.

The word of the Lord who calls Hannah’s son is Mary’s boy.

The word of the Lord— the Logos— is Jesus.

The reason the word of the Lord responds, over and over again, to the hot mess that is the house of Israel, responds just like Christ before the woman caught in adultery, is that the word of the Lord in the Old Testament just is Jesus.

Fully human, fully divine Jesus. Jesus did not become fully human and fully divine— that’s not the dogma. Jesus is fully human and fully divine, eternally so. As Jesus says in the Gospel of John, “Before Abraham was, I am.”

The logos who speaks in the Old Testament is not some other extra word of God.The logos is Jesus.January 11, 2024

Seven Ways of Looking at the Transfiguration

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Jesus metamorphosed. Celebrities from the past. Petrified disciples. Luminous cloud. An event as important as Christmas or Easter! My friend Sarah has a new book coming out on the Transfiguration, and I think this conversation demonstrates why you’ll want to check it out.

Get in on the book here. It will go live on Tuesday.

Find out more about Sarah here.

SummaryTakeawaysSarah discusses the significance of the Transfiguration and its importance in the church calendar. She explores the distinction between the transfigured Jesus and the risen Jesus, highlighting the unique characteristics of each. Sarah also delves into the misunderstood offer to build booths and its connection to the Festival of Booths. She examines the representation of Moses and Elijah in the transfiguration and their role in the eschatological narrative. Sarah emphasizes the Jewish reticence to capture the glory of God and the modesty of biblical miracle stories. She concludes by emphasizing the importance of listening to Jesus. In this conversation, Sarah Henlicky Wilson discusses the transfiguration in the Gospel of John and its connections to Sukkot and other Jewish festivals. She highlights the allusions to Sukkot in John and the significance of Jesus' entrance into Jerusalem for the final Passover. Sarah also explores the presence of Greeks in the Sukkot story and their connection to Jesus' hour of glorification. She emphasizes the similarities between the synoptic transfiguration and the transfiguration in John, suggesting that both narratives are mapping the same thing in their own distinctive ways. Sarah concludes by inviting listeners to support her Kickstarter campaign for her book on the transfiguration.

The Transfiguration is an important event in the church calendar, often overlooked compared to Christmas and Easter.

The transfigured Jesus and the risen Jesus have distinct characteristics, and the transfiguration cannot simply be seen as a preview of the resurrection.

The offer to build booths in the transfiguration story is connected to the Festival of Booths and the eschatological gathering.

The presence and movement of God in the Old Testament are described with a sense of awe and reverence, avoiding capturing or naming the glory and splendor of God.

The transfiguration serves as proof for the second coming of Jesus, emphasizing the importance of his eschatological role. The Gospel of John contains allusions to Sukkot and other Jewish festivals, connecting them to the transfiguration.

The synoptic transfiguration and the transfiguration in John share similarities and are both mapping the same thing.

Jesus' entrance into Jerusalem for the final Passover is significant in relation to the transfiguration.

Sarah Henlicky Wilson has launched a Kickstarter campaign for her book on the transfiguration.

Chapters00:00 Introduction to the Book Project

00:30 The Significance of Transfiguration Sunday

01:40 The Neglected Importance of the Transfiguration

02:12 The Problem of Moralistic Preaching

03:25 The Transfiguration as Important as Christmas and Easter

03:54 The Distinction Between the Transfigured Jesus and the Risen Jesus

06:22 The Misunderstood Offer to Build Booths

10:10 The Festival of Booths and the Eschatological Gathering

12:22 The Significance of Peter's Mistaken Offer

15:06 The Transfiguration and the Eschatological Jesus

19:19 The Presence and Movement of God in the Old Testament

22:07 The Representation of Moses and Elijah

25:45 The Role of Moses and Elijah in the Transfiguration

28:46 The Transfiguration as Proof of Jesus' Second Coming

30:27 The Jewish Reticence to Capture the Glory of God

35:15 The Absence of Visual Detail in 2 Peter

38:09 The Modesty of Biblical Miracle Stories

39:37 The Importance of Listening to Jesus

39:47 Transfiguration in the Gospel of John

40:20 Allusions to Sukkot in John

41:16 Connection between Sukkot and Palm Sunday

41:43 Greeks and the Sukkot Story

42:13 Jesus' Hour Has Come

42:40 Incomprehension of the Crowd

43:28 Mapping the Same Thing in Different Ways

44:13 Jesus' Pilgrimage Festivals

44:39 Hanukkah in the New Testament

45:39 Importance of Ascension and Pentecost

46:32 Sarah's Kickstarter Campaign

48:57 Sarah's Contact Information

49:42 Memories of Sarah

50:03 Harry Potter Trivia Challenge

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 10, 2024

Living the (Correct) Questions

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

The lectionary Gospel for this coming Sunday of Epiphany is John 1:43-5:

The next day Jesus decided to go to Galilee. He found Philip and said to him, "Follow me." Now Philip was from Bethsaida, the city of Andrew and Peter. Philip found Nathanael and said to him, "We have found him about whom Moses in the law and also the prophets wrote, Jesus son of Joseph from Nazareth." Nathanael said to him, "Can anything good come out of Nazareth?" Philip said to him, "Come and see." When Jesus saw Nathanael coming toward him, he said of him, "Here is truly an Israelite in whom there is no deceit!" Nathanael asked him, "Where did you get to know me?" Jesus answered, "I saw you under the fig tree before Philip called you." Nathanael replied, "Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!" Jesus answered, "Do you believe because I told you that I saw you under the fig tree? You will see greater things than these." And he said to him, "Very truly, I tell you, you will see heaven opened and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Man."

People often send me their questions about faith, doubt, God, and the Bible.

A recent such question was posed so:

“Jason, there are a lot of questions I could submit to you, but in my opinion, given what science teaches us about the world’s origins, all those questions boil down to the biggest question of all.

Is there a God?”

When I started out as a pastor twenty plus years ago, it was vogue to reconstruct catechesis under the slogan “Living the Questions.” Of course, the gospel can never be said the same way twice; therefore, it’s appropriate to present the message of Jesus’s death and resurrection according to the idioms of our time and place. Nevertheless, it was the case then as much as it is now: you don’t need any encouragement to question the faith.

Many beleaguered believers never venture beyond deconstructing their former faith. Indeed, ours is a cynical culture, one that conditions us to question and doubt received tradition and the institutions that steward it, including the Church and her gospel.

Now I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with questioning; I’m not suggesting there’s anything wrong with doubt.

After all, by definition the very concept of faith requires doubt.You can only have faith in what is not certain.For example, I have faith that my children will always love me, but that my children will always love me can never be a certainty. And if something is not certain then it is not immune to doubt. There’s nothing wrong with questioning.

Jesus in the middle of Sunday’s lectionary Gospel passage chastises Nathaniel for believing too quickly, too blindly:

The problem is that I don’t know many people who are like the Nathaniel, believing quickly and without question.Instead I know a lot more people who are like the pre-Christian Nathaniel at the beginning of the Gospel story—The Nathaniel who rolls his eyes dismissively at the notion that any wisdom could ever come from a backward, ignorant, archaic place like Nazareth.Nathanael replied, "Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!" Jesus answered, "Do you believe because I told you that I saw you under the fig tree? You will see greater things than these."

I know a lot more people who are like that Nathaniel, who think all religion is, in a sense, “from Nazareth.”

If you think you have to choose between intellectual honesty and belief in God, then you’ve simply not understood what Christians mean by the word God.

If you think empirical science could ever disprove God, then you’ve only proven that you forgot to investigate the ancient meaning of the word God. If you think the biggest question boils down to “Is there a God?” then you don’t realize what Christians— and Jews and Muslims and Hindus and even some Buddhists— mean when we say the word God.

So in light of the lectionary Gospel for this Sunday of Epiphany, I don’t want to encourage you to question your faith.

Or rather, instead, I want to encourage you to question your faith in the assumptions the modern world has given you:The assumption that the 21st century raises questions to which the ancient faith has no answers.

The assumption that Christianity is not as intellectually rigorous as any other discipline.

The assumption that we as modern people know a great many things the ancient Christians did not know— and that may be true, but it’s also true that the ancient Christians knew a few things very well that very few of you know at all.

Namely, philosophy and logic.

I don’t want to encourage you to question God.

Instead I want to make an argument, for God.

I want to make a philosophic argument, one that comes out of the ancient Christian tradition, from Thomas Aquinas, who was probably the greatest thinker in the history of the Church. I want to take you through Thomas’s argument because if you understand his logic then you will understand what Christians mean, fundamentally, by the word God.

If you understand the word God, then you will understand why “Is there a God?” is not, in fact, the biggest question.Rather, God is the answer to the biggest, most obvious question of all.Now first, Thomas would say that not only is the question “Is there a God?” not the biggest question of all; it’s not even a good question. It’s a bad question. Why?

It’s a bad question because its premise is wrong.

January 9, 2024

Epiphany: The Season of Glory

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Hi Friends,

My mentor and muse, Fleming Rutledge, has a new book out, Epiphany: The Season of Glory.

I invite you to join me and some friends on the Monday nights before Lent as we discuss her book. My friend Josh Retterer will also be offering some reflections on the book that we will push out to participants during the weeks of the study.

Register— do it— HERE.Here is an excerpt from the book’s introduction. Buy the book here.

Many scholars have attempted to reconstruct the earliest years of the liturgical calendar. It is pleasing to imagine the leaders of the emerging Christian communities discussing the various portions of the Bible and attaching them to the various liturgical feasts and seasons, selecting which ones to use and how to place them in a sequence. Exactly how all of this was accomplished in the first four centuries is largely unrecoverable to historical method. The wonder is that still today, the liturgical calendar retains its power. The list of historical calamities over the centuries has been amplified by the extreme, indeed unprecedented, global threats of our own time in the third millennium, and yet the Word of God read in the sequence of the church seasons remains ever “living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword” (Hebrews 4:12). Whatever charges can be brought against the lectionary, it remains an extraordinary sword in the hands of the Church Militant.

We know for certain that the liturgical calendar began to take shape in the first four centuries AD, but it did not become embedded in all formal Christian worship until the sixteenth century. When the Protestant Reformation declared its independence from the Church of Rome, a large part of the Western church abandoned the calendar, along with a great many other accumulated traditions.

Observation of the church seasons remained largely intact, however, in the Anglican Communion (including American Episcopalians), the Lutheran church, the Moravian church, and a few other smaller branches. In recent decades, there has been a phenomenal resurgence of interest in the other American “mainlines”—Methodists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, the Reformed churches—and also in a surprising number of looser forms of Protestantism.

This somewhat unexpected development has shown that the calendar can be a powerful aid to growth in faith and service. The rhythm of the seasons, the repetition of the sequence year after year despite outward circumstances, the variety and richness of the Scripture readings, and, most of all, the story that the seasons tell in narrative progression throughout the year—all of this can be powerful for the nourishment of growth in grace. Thus we may say that the calendar is edifying—providing instruction, guidance, and inspiration for the upbuilding of the church.

But above all, the church year leads us to Jesus Christ. This will be the central focus of the pages that follow. The progression of seasons, when all is said and done, is designed so that the members of Christ’s body may participate even now in his eternal life by rejoicing in his living presence, following him in our various vocations, enacting his teachings in our ministries, knowing him as our Savior, and above all glorifying him as Lord. In our time, however, many of the very same mainline churches who show a new interest in the church seasons have grown weak in proclaiming Christ. It does not give me any pleasure to note this. Jesus of Nazareth is revered as a teacher and moral exemplar, not infrequently side by side with various other religious figures, but the apostolic message about the unique identity and destiny of the Messiah (Christos) has become attenuated. As for the so-called evangelical, conservative, or right-wing churches, they have often allowed Jesus to become a repository of various grievances, so that the invocation of his name at political rallies has become commonplace.

When something or someone less than God in Jesus Christ is evoked in worship, the central focus of the apostolic message is obscured, if not negated outright.The good news that the Scriptures proclaim will not thrive in this theological crisis. Serious attention paid to the themes of the season following the Feast of the Epiphany, in particular, can be a strong antidote to a weak Christology. To be sure, all of the church calendar is formed around Jesus, but there is a sense in which Epiphany is the most specifically christological season.

The lectionary readings for Epiphany are chosen and arranged in an order designed to glorify him. When the season is preached and taught with this in mind, there can be no doubt—for those who have ears to hear—as to who Jesus is and what he has been born to accomplish. As we shall see, there are particular events from Christ’s life that have been part of Epiphany for two millennia— events that specifically elevate him as Savior and Lord.

Because of this, the season needs to be brought into the foreground along with Christmas. If the season of Epiphany were to be strongly presented as a central, cohesive narrative during the winter months by clergy, teachers, and other leaders, it would make a powerful impression.

Lent gets more attention, and for good reason, but Epiphany can excel in theological and narrative power if it is forcefully shaped, preached, and taught. If those who shape worship in local congregations took seriously the opportunity to manifest the identity, mission, and, yes, the glory of Christ as Epiphany unfolds, it could be a transformative season of growth in faith. It is not for nothing that the season has been associated with mission and growth— with the spread of the gospel (much more of that later).

The season of Epiphany always begins on January 6 (the Feast of the Epiphany) and extends until Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent. Ash Wednesday’s date is determined by the date of Easter, so Epiphany is much shorter in some years than in others. This may have something to do with its comparative neglect in the church.3

Despite its beauty and depth, it is arguably the least understood and least appreciated of all the seasons. We know Advent, or think we do, because it comes just before Christmas—a fact which, for better and worse, has shaped the season. We know that Lent means the cross, and Easter means the empty tomb. Pentecost means the descent of the Spirit.

Epiphany means . . . what, exactly?

Epiphaneia in New Testament Greek means manifestation. An effective method of teaching the content of the faith, not often enough used, is to instruct congregations in the texts of the seasonal hymns.

The fulness of the incarnation that has taken place will be manifested in various ways during the Epiphany season—and climactically in Lent and Easter soon to follow. The themes of Epiphany can be powerfully preached and taught for the health and growth of the church. They are revelatory themes, suitable to the overall motif of manifestation or showing forth—the basic definition of epiphaneia in New Testament Greek. What exactly is it that is shown forth? We shall see as the biblical witness unfolds.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 8, 2024

Because of the Bicycles

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

Anne Frank, in the Broadway play adapted from her classic diary, according to the playwright Meyer Levin, wrote: “Why are Jews hated? Well one day, it’s one group, and the next day another….” But that is not what she said at all. It was the play’s author who wanted to de-Judaicize antisemitism. Her words were far more profound: “Who knows, it might even be our religion from which the world and all peoples learn good, and for that reason and that reason only do we now suffer.”

Here is the most recent conversation with my friend Rabbi Joseph Edelheit.

Below is one of the articles we reflected upon:

Why do they hate us?

I first asked this question when I was a young boy, fleeing the Holocaust on the last boat out of Europe. Now I have an answer.

Ever since I was a young boy, fleeing with my family who managed on the eve of the Holocaust to somehow escape on the very last boat of refugees from Europe to the safety of the United States, the question has consumed me: Why do they hate us?

My father, a prominent rabbinic scholar, who in my mind knew everything, avoided answering me. But soon, he assured me, I would no longer be victim of the antisemitism that swept through my birthplace. Soon, America would prove to me that hatred of Jews was a disease that was curable, a profound sickness of the soul whose expiration date would coincide with the defeat of Hitler and his Nazi demons.

And in large measure, he was right. America increasingly began to live up to the promise of the words inscribed as welcome on the Statue of Liberty. Jews found unparalleled freedom, respect, equality — the hallmarks of a civilized society. Until now! Until “genocide” — a word invented to express the unique horror perpetrated against the Jews — is used as an accusation of the victim; bestially slaughtering and raping Jews is exempt from criticism, depending upon “context”; and a people with a 3,000-year history of linkage to the land of Israel, as descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, to whom the land was biblically promised, is condemned as “colonials,” by followers of a religion whose founder was born in the sixth century!

Once more I need to ask: Why do they hate us?

Anne Frank, in the Broadway play adapted from her classic diary, according to the playwright Meyer Levin, wrote: “Why are Jews hated? Well one day, it’s one group, and the next day another….” But that is not what she said at all. It was the play’s author who wanted to de-Judaicize antisemitism. Her words were far more profound: “Who knows, it might even be our religion from which the world and all peoples learn good, and for that reason and that reason only do we now suffer.”

Perhaps we will never really understand. Perhaps Emil Fackenheim was right when he sought an explanation for the Holocaust: “There will never be an adequate explanation. The closer one gets to explicability, the more one realizes nothing can make Hitler explicable.” Perhaps to offer reason for the unreasonable is a step down the path of Spinoza’s famous maxim that “to understand all is to forgive all.”

But there is one explanation that just may be the most valid because it came from Hitler himself. It is the confession of the prime prototype of the antisemite used to justify its application to six million victims. Indeed, it is the very debt of the world to Judaism’s discovery of ethics and morality that for some necessitate its destruction.

These are the words of Hitler himself: “Providence has ordained that I should be the greatest liberator of humanity. I am freeing man from the restraints of an intelligence that has taken charge, from the dirty and degrading self-mortifications of a false vision called conscience and morality…The Ten Commandments have lost their validity. Conscience is a Jewish invention; it is a blemish like circumcision.”

It is an insight long ago expressed by the Talmud: Why, the Rabbis ask, was the Torah given on a mountain called Sinai? Because the Hebrew root of the word Sinai is “sinah” — the Hebrew word for hatred. The message of Sinai is the essence of Judaism: God places moral demands upon us. These obligations define us as human beings created in the image of our Maker.

And for that, Jews continue to be hated, and presumably will be until the world acknowledges conscience not as curse but as blessing.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 7, 2024

God’s Balm from Gilead

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

1 Kings 17.1-16

Fleming Rutledge recalls the confirmation program in the parish where she first preached. The group of thirteen year olds met every week for seven months. At the start of the course, Fleming prompted them with a simple exercise.

She asked each confirmand to draw a picture of God.

The results were not surprising.

“All sorts of things emerged,” she writes, “clouds, suns, circles, triangles, and a preponderance of old men with white beards.”

Once the confirmands completed the illustrations— idols— the class sat in a circle and took justifying their depiction of God. “At this point,” Fleming recalls, “a clean, empty wastebasket was brought in and set down in the middle of the circle.”

She then instructed each confirmand, one by one, to tear up his or her picture of God and throw the pieces in the trash. As they did so, the Bible was opened and the Second Commandment read solemnly, "Thou shalt not make for thyself any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, or in the waters under the earth."

The law provoked silence from the students who had just trespassed against it. The turn came, Fleming writes, when she then asked the students the question at the heart of biblical faith, ”If we can't draw a picture of God, and if we don’t know what God looks like, and if God isn't like anything in heaven or earth, then how can we know anything about God at all?"

While the students pondered the question, the teacher turned to an earlier chapter in the Book of Exodus, the story of the Lord encountering Moses at the Burning Bush.

As Fleming remembers it:

“We did this exercise every year at Christ Church, and every year the Lord was good enough to give us one or two bright-eyed young people who would catch on. Let me read the crucial parts again. Remember the question: How do we know anything about God? In the light of the Second Commandment, how do we know anything about God? That was the question. Every year, the story of the Burning Bush would elicit this answer from one or another boy or girl, ”He tells us! God tells us who he is!" It was always a magical moment in the class for those who "got it.””

The Lord Jesus insists on nothing less in the Gospels when the Sadducees attempt to entrap him with questions about the woman who was widowed seven times.

“In the resurrection, whose wife will she be?” they ask Jesus.

And the Lord replies, “Is not this the reason you are wrong, that you know neither the scriptures nor the power of God?"

Neither the scriptures nor the power of God.

The link between the two is the key.

The power of God is manifest in his word.

For those who get it, it’s better than magic.

It is God’s message itself.

“Now Elijah the Tishbite, of Tishbe in Gilead, said to Ahab, “As the Lord the God of Israel lives, before whom I stand, there shall be neither dew nor rain these years, except by my word.” And the word of the Lord came to him.”

The Lord’s calling of Elijah makes up the dramatic center of the book of Kings, and Elijah's narrative in the Old Testament marks an epochal shift in the way the Lord works with and among and against his people Israel.

From the time of Moses through the period of the judges, the Lord worked through the twelve tribes of Israel with the high priest as the central mediating figure.

After the Book of Judges, with Saul and then David especially, the Lord worked with Israel as a whole through Israel’s king.

After King David’s death, when successor after successor rejected the Lord and succumbed to syncretism and idolatry, the Lord’s way of working once again shifted, away from Israel’s kings and to the Lord’s prophets and the remnant community created around them.

Elijah inaugurates this final shift in the Old Testament.

In the chapter before the passage, King Ahab of Israel enters into a diplomatic marriage with Jezebel, a pagan consort from Sidon. Jezebel brings with her to the holy land four hundred and fifty prophets of Baal. No sooner has Ahab said “I do” to Jezebel than he erects a temple to Jezebel’s god, Baal, and initiates a violent campaign to persecute the faithful remnant of Jews.

The narrator of the book of Kings puts it bluntly:

“Ahab son of Omri did more evil in the sight of the Lord than all who were before him…as if it had been a light thing for him to walk in sin…[thus] Ahab did more to provoke the anger of the Lord, the God of Israel, than had all the [unfaithful] kings of Israel who were before him.”

The Holy Spirit blows where it will, Jesus says.

Just so—

In 1 Kings 17, Elijah bursts upon King Ahab’s council chambers without an iota of introduction or warning, and, inexplicably, the man of God from Gilead dares an explosive, seemingly self-endangering announcement, “As the Lord the God of Israel lives, before whom I stand, there shall be neither dew nor rain these years, except by my word.”

The nineteenth century German preacher F.W. Krummacher described Elijah as “a man mighty in word and deed, and in miracles besides; who broke forth suddenly like a fire, and whose word burnt like a torch…”

Baal is the Canaanite Zeus.

Baal is the god of the sky.

Baal is the rain god.

There shall be neither dew nor rain except by my word.

King David has been dead for a century. Dead also, it has seemed, is David’s Lord. For a long time, Yahweh has appeared to be in retreat from the rival gods.

F.W. Krummacher writes, “Under Ahab’s reign, heathen altars occupy the holy land, every hill smokes with their sacrifices, darkness reigns throughout the land with no cheering epiphany star until…the word of the Lord comes to Elijah of Gilead.”

His name is his sermon.

Elijah means, “Yahweh is my God.”

Or, Yahweh is the only true God.

To prove it, Elijah prophesies drought and famine with divine infallibility thereby revealing the impotence of Ahab’s barren deity.

There shall be neither dew nor rain.

And immediately the prophet’s word strikes like a fever into the heart of the earth because the word of God is the power of God.

Elijah is the balm God brings from Gilead.

A few years ago, in a Wall Street Journal article entitled “Revelation Revised,” Stephen Prothero, a professor of religion at Boston University, wrote:

“Any claim of revelation is preposterous. It presumes that God exists, that God speaks, and that all is not lost when human beings translate that speech into ordinary language.”

Needless to say, Professor Prothero’s rejection of revelation reflects a skepticism which many people— many church people, in fact— share. He certainly did not intend it as such, but those two sentences in his Wall Street Journal article are the perfect distillation of biblical faith. Ironically, they are the same fundamental presuppositions that appear in the prophet Elijah’s self-introduction in 1 Kings 17.

1. The true God is a living God; that is, the true God is lively, at work and up

to something in the world.

2. His word comes to us with the power to execute what it announces— the

word works what it says.

3. All is not lost therefore— with mere ordinary language, we are armed

with the power of God.

As Karl Barth taught, the question the Bible answers is not, “Does God exist?” The Bible threatens us by answering a more disarming question, “What has the God who exists said? What does God say to us?” According to Barth, all of scripture and the entire Christian faith hang on the veracity of Elijah’s introduction, “And the word of the Lord came to him.”

He tells us. God tells us who he is.

The apostle Paul writes about this dynamic between the word of God and the power of God in the climax to his epistle to the Romans, “So then faith is awakened by the message, and the message that awakens faith comes through the word of Christ.”

Faith is created by the message itself.

The word is the active agent.

This is exactly why Paul is not ashamed of the gospel.

It is the power of God.

Years ago, a worshipper came up to me after service and introduced himself. “Hi, I’m John Bobo,” he said. “I’m new here, and I want to talk to you about transferring my membership to this congregation.”

“Really? What makes you want to join this church?”

“The preaching,” he replied.

“Oh,” I said, as I felt my head swell a little bigger. “You think the preaching’s pretty good, do you?” And I elbowed the choir director standing next to me.

“Good? No, you’re not very good, sorry. But, you do preach like you really believe God said all this stuff, that God spoke. That’s what I want. That’s harder to find in the church than you might guess.”

And I thought of Fleming’s story about her confirmation class.

“God says,” I said to him.

“What’s that?” he titled his head like the U.S. Attorney he was and he asked me to fill in the loophole.

“God says,” I said, “It’s not that God said all that stuff in the Bible but is otherwise silent. It’s that with it— with scripture— God says. What God said is the way God speaks still.”

I watched him mull it over and then I witnessed the epiphany come over him as he got it. Fleming’s right, it was a magical moment.

“I get it,” he said, “I get it.” This is the word of God for the people of God, he muttered to himself in sudden realization. “That gives me even more reason to join.”

Regarding the scarcity of conviction in the power of the word, Fleming Rutledge writes:

“The spectacle of mainline church decline is not encouraging to anyone. Speaking as one who has traveled extensively through the mainline churches, I believe that the essential problem[afflicting the mainline churches and the reason for their decline and divisions can be precisely identified in the words of Jesus to the Sadducees: “Is not this why you are wrong, that you knowneither the scriptures nor the power of God?”

The power of God is manifest through his Word. This is the power that created the Church in the first place, it is the engine that drove the Reformation⎯yet this power today is increasingly less heard in mainline churches, either as thunder or as still small voice, for mainline Christians have largely ceased to believe that God speaks. All the symptoms [of our shrinking and schisms] arise from that cause. That is the underlying ailment that is producing the morbid effects. The vitality of Protestantism will only come in the present as it camein the past, through the power of the Word itself.”

You do preach like you really believe God said all this stuff. That’s harder to find in the church than you might guess.

I have never forgotten his judgment.

I’m still not very good. But I am not ashamed of the gospel. Even attached to my words— I know. In my bones— in my cancer-carrying bones— I know even attached to my words, the word of God is the power of the living God.

The correlation Fleming Rutledge draws between the vitality of the people of God on the one hand and their appreciation for the power of the word of God on the other hand is not an arbitrary connection.

It is a causality drawn clearly by the scriptures.

For instance—

Just after Elijah proclaims the word of the Lord to Baal’s king and consort, the Lord sends him into the wilderness— an exodus from the promised land.

An exit.

A century before, the Philistines captured the ark, a sign that the Lord had removed himself from Israel.

In judgment.

Just so, when God sends Elijah out into the wilderness, God’s word is silenced in Israel, for Elijah is the only bearer of Yahweh’s word left in the promised land. To the famine of bread and water, Yahweh adds a famine of the word.

In other words—

By sending Elijah out of Israel, the Lord removed from his people the word they refused to revere and to hear.

You’re not going to listen, I’m leaving.

Deprived of God’s word, they were deprived of God’s power.

And so they dwindled.

Which is to say, every Christian believer has an obligation— no, a vocation— to attend to and abide with the scriptures. It is your calling to search the scriptures.

Mind you— there can be no calling without one who calls.

Elijah obeys the word of the Lord so far as to allow unclean ravens to feed him. Elijah obeys the Lord so far as to journey into Zarephath, Jezebel’s territory, where he has every expectation of being captured and killed. Elijah runs for seventeen miles alongside Ahab’s chariot. Elijah calls down fire from the Lord and defeats four hundred and fifty prophets of Baal. Elijah is, as Ahab names him, “the Troubler of Israel.”

Nevertheless!

The most important part of his story comes in the first verses, “And the word of the Lord came to Elijah.”

In his Wall Street Journal article, “Revelation Revised,” Professor Stephen Prothero writes, "Any claim of revelation is outrageous. It presumes that God exists, that God speaks and that all is not lost when human beings translate that speech into ordinary language.”

“But,” Prothero continues, “time mutes the outrage, or muffles it. Many of us greet the miracles of Jesus with a shrug, and there is little scandal any more in claiming that the Bible is the word of God.”

Notice—

The professor of religion makes the same mistake the U.S Attorney first made.

He puts revelation in the past tense.

The scholar knows not what the seventh grade confirmand knew.

He tells us.

The claim is indeed outrageous.

The claim is not that once upon a time God spoke— you’re wasting your Sunday morning if that is our claim.

The claim is not that God spoke; the claim is that God speaks.

The claim is not that God spoke long ago and we call this past revelation scripture; the claim is that the living God speaks today by means of the scriptures.

To paraphrase the Second Helvetic Confession, the saying of what the Lord has said just is the Lord’s saying.

It’s revelation, revisiting us each and every time anew.

The theologian Steven Paulson tells the story of one of his seminary students who took his first church out in the hinterlands of Minnesota.

After a few weeks, the newly minted pastor called Professor Paulson to update him on his new parish.

“How do you fire a volunteer?”

Dr. Paulson asked him what he meant, and the rookie pastor replied, “There’s this old widow in the congregation. She’s here every day sweeping the hallways with her straw broom. She’s mean. She’s rude. She’s generally unpleasant, and she does a terrible job of sweeping and cleaning. But, we’re not paying her, so I don’t know how we’re supposed to get rid of her.”

“Maybe there’s a reason she needs to be there day after day. Try finding out what it is, and if it is, don’t waste any time. Give her the goods. Lay the Gospel on her.”

Paulson says a few days later the student called him again. “Dr. Paulson, Dr. Paulson...I did it. I asked her why she spent so much time at church, but seemed so miserable doing it.”

“And?”

“And she told me, ‘Forty years ago, I cheated on my husband with another man, and twelve years ago he died without ever knowing I had betrayed him.’”

“So, I did what you told me,” the student told the professor, “I said to her, ‘In the name of Jesus Christ and by His authority alone, I absolve you of all your sins.’ And as soon as I gave her the absolution, her whole countenance changed and she said, ‘I have been here Sunday after Sunday, day after day, week after week, for forty years pushing this God-forsaken broom, waiting to hear God say that to me.”

Notice—

She didn’t say, “I’ve been waiting to hear someone say…”

She said, “I’ve been waiting to hear God say.”

To the former student’s story, the professor laughed and said, “Amen.”.

“Wait, it gets better,” the student added.

“No sooner had she told me she’d been waiting to hear God speak, she threw the broom down on the floor and said, ‘I don’t have to do this anymore,’ and she walked out the front door, light on her feet, freed of her burden.”

The word works what it says.

The word of God is the power of God.

Present tense.

All is not lost.

What is the word the Lord has in this word for you this day, I wonder?

I sure as hell don’t know.

I’m not in charge up here.

Because God speaks, because Jesus lives with death behind him and is the one who so speaks through scripture, Robert Jenson proposes a bracingly simple question for those come to the word of God for a word from God.

“What does the text promise,” Jenson asks, “and what may I thus promise that can be and only can be because Christ lives and speaks? What future may I promise others and cling to myself by the leading and authority of this text?”

Here’s what I know.

And here’s what I can promise.

I know some of you are facing the fears that come with the fact that none of us are getting out of life alive and you wonder where God is amidst all the beeps of the monitors and drips of the bags and the aromas of the disinfectant and the steamed smells of the hospital food.

I know some of you are discouraged that more than one quarter of the churches in our denomination have left our denomination in the past year.

I know some of you are worried about our partisan divide and what the coming year portends for our democracy.

I know some of you see new families in our midst but fret how they will foot the bills covered by long-timers.

I know some of you are burying marriages.

I know some of you are sitting shiva next to parents.

I know some of you are attempting to climb back onto the wagon.

I know you’re all wondering where God is in the midst of it.

That’s what I know.

And this— on the basis of this word of the Lord to Elijah— this is what I can promise, and perhaps it is the Lord’s word for you this day.

So listen for the word of the Lord.

In Elijah’s day and for a hundred years before—

It has appeared that Yahweh is in retreat.

Gone.

Absent.

Dead or distant or disinterested.

Nevertheless!

The word of God comes to God’s balm from Gilead.

Therefore— hear the good news:

While the church may suffer setbacks, while God’s people may suffer, while you may mourn or steward fright, the Lord is never frustrated. He never retreats. He never has to regroup or reconsider. His resources or numbers are never too little or too stretched or too meager to use to accomplish his promises to you, for us. As stuck as a situation might seem, his word is always moving forward, ready “to strike like a fever into the heart of the earth.” No matter how far gone a circumstance may seem, he always has a balm from Gilead.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers