Jason Micheli's Blog, page 50

February 26, 2024

Why is Jesus So PO'd?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

John 2.13-22

The lectionary Gospel passage for the Third Sunday of Lent is John’s account of Jesus’s Temple Tantrum:

Here’s my question:Why is Jesus so righteously angry?The Passover of the Jews was near, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. In the temple he found people selling cattle, sheep, and doves, and the money changers seated at their tables. Making a whip of cords, he drove all of them out of the temple, both the sheep and the cattle. He also poured out the coins of the money changers and overturned their tables. He told those who were selling the doves, "Take these things out of here! Stop making my Father's house a marketplace!" His disciples remembered that it was written, "Zeal for your house will consume me." The Jews then said to him, "What sign can you show us for doing this?" Jesus answered them, "Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up." The Jews then said, "This temple has been under construction for forty-six years, and will you raise it up in three days?" But he was speaking of the temple of his body. After he was raised from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this; and they believed the scripture and the word that Jesus had spoken.

And notice, Jesus is not spontaneously PO’d— this is a premeditated crime.

What happened to the cute baby Jesus in the golden fleece diapers? I mean, this Jesus takes the time to craft his weapon, braiding his whip before cracking it. He drives the cattle off in all directions. He sends the sheep away bleating. He sets the caged birds free. And then Jesus kicks over all the ATMs.

John puts this moment of aggressive street theater at the beginning of the Gospel.

In Matthew, Mark, and Luke it comes at the end of Jesus’s ministry; in fact, it is the stunt that finally seals his fate.

Why?

Why does Jesus pitch this Temple tantrum? Why’s he so angry?

The economy of exchange? The animal kiosks and currency converters?

It’s in the Bible— this business had to be done.These priests and pilgrims are simply obeying God’s Law. They’re doing what the scriptures command them to do. On Mount Sinai, God doesn’t just reveal to Moses ten commandments. God keeps on talking and gives to Moses over six hundred commandments, including blueprints for the tabernacle and instructions for the cycle of sacrifices God’s People were to offer there, sacrifices of praise and thanksgiving and sacrifices for sin to make atonement.

The economy of sacrifice is explicit in the Law.

The economy of sacrifice is explicit in the Law. Because high holy days like Passover and Yom Kippur attracted pilgrims from all over the Jewish diaspora, from Gentile nations, Israel had to take care that no one made an offering to the Holy God with an unclean animal.

You needed your meat to be ethically sourced.

You didn’t want your Jewish cousin from Jersey coming into Jerusalem for the holiday with a cow from some pagan farmer’s herd in tow.

It’s spelled out. The animals sanctioned for sacrifice in the Temple had to be purchased at the Temple so that their provenance was guarranteed.

Is this why Jesus is angry?

If so, why? After all, Jesus is the one who spoke to Moses on Mt. Sinai.

Of course—

Roman occupation made even simple, everyday transactions in Israel morally complicated.Rome’s currency bore the image of Caesar along with the inscription, “Caesar Augustus, Son of God.” In doing so, Roman coins baldly violated Yahweh’s first and most important commandment (“You will have no other gods but God”); therefore, in order for Jews to make the sacrificial offerings prescribed by God’s Law they first had to exchange Caesar’s currency for special Temple currency— the Temple currency functioned like the coins at Chuck E. Cheese; they could only be spent in that place and they had no value outside of it. And sure, this currency conversion was not part of God’s design— and maybe it’s a bit unseemly with all the airport terminal upcharges— but what were God’s People supposed to do?

Is this really why Jesus is mad as hell?If so, he’s cracking the whip at the wrong people, right?Israel didn’t invite Caesar into their lives.Caesar invaded them.So, if it’s not the sacrificial animals or the currency exchange, then what is it? What’s Jesus driven to a felonious rage?

Notice—In the midst of his Temple tantrum, Jesus refers to himself as the Temple:

Notice—In the midst of his Temple tantrum, Jesus refers to himself as the Temple:“Destroy this Temple and in three days I will raise it up.”

By contrast, in Matthew, Mark, and Luke this statement is put on the lips of Christ’s accusers at his trial. What’s more, his accusers edit the statement, claiming Jesus said:

“I will destroy this Temple and in three days I will build another.”

In Matthew, Mark, and Luke the accusers make Jesus the agent of destruction.

But, in John’s Gospel, Jesus makes us the agents of destruction, which makes Jesus the Temple.

Hold up—

If Jesus is the Temple, if Jesus is the unmediated presence of the holy God, maker of heaven and earth, then what’s inside that other Temple?

February 25, 2024

The Justification of God

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Second Sunday of Lent — 1 Kings 21

On September 1, 1939, his covetous gaze having landed upon his neighbor’s land to the east, the Fuhrer in Berlin invaded Poland. The Nazi invaders met with open armed resistance, which they put down with brutality by the end of the next month. It took only a few more months until most of the Polish population acquiesced or enabled the German occupation.

One stood out.

In 1940, if not for the chaos and disarray of the occupation, Teresa Prekerowa would have been a high school senior. Teresa was a Christian. More importantly, Teresa was a Christian who knew that being a Christian might often or might eventually require her to act as Christ and stand out. Before the war, she had studied at a Catholic boarding school. Her family was relatively well-off, landowners in rural Poland. They even cultivated a vineyard. The Prekerowa family’s land had been passed down from one generation to the next as an inheritance. Their property was stolen when the Germans invaded and forced the family to relocated to Warsaw where they rented an apartment in the city.

Soon thereafter, as the thieves’s plot thickened and the occupation’s grip tightened, Teresa’s father was arrested by Section 581 of the Military Field Police. Her uncle was killed in battle. Two of her brothers languished in German prisoner-of-war camps.

In late 1940, after destroying much of the city and killing twenty-five thousand people in an air raid campaign, Germany began to establish ghettos in the parts of Warsaw under their control and to exile Polish Jews into the ghettos from which they would eventually be transported to death camps.

Teresa stood out.

Though only a young woman, she refused to adjust to her circumstances or accept the new situation as normal.

For example—

Teresa noticed how very early into the occupation Christian families in Warsaw quietly allowed their Jewish friends to slip away from their lives. Thus, they enabled the crime being done to them by neglecting what they ought to have done for their neighbors. Teresa’s own brother was one who, in the name of safety and survival, turned his back on his Jewish girlfriend and her family.

But Teresa stood out.

In late 1940, Teresa started sneaking into the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw. At first, she took food and medicine and clothing to the Jews she knew in the ghetto. Soon, she was taking supplies to Jews she did not know. By the end of 1940, Teresa had persuaded her brother’s girlfriend to escape the ghetto. In 1942, Teresa helped the girl’s parents and brother escape. That same summer the Germans carried out what they called the “Great Action,” deporting some 265,040 Jews to the death factory at Treblinka to be murdered and killing another 10,380 Jews in the ghetto itself. Thus, Teresa saved a family from certain death.

Teresa snuck in and out of the ghetto dozens and dozens of times.

The risk was terrific.

She never told her family.

Nor did she much like to talk about her witness at all.

After the war, Teresa Prekerowa became a historian of the Holocaust, but she did not write about herself. In an oral interview, Teresa dismissed the notion that she was in any way exceptional.

She called her actions “normal:”

“When a believer is bound by the double-love command of the Bible— love of God enacted as love of neighbor— then it’s simply to be expected that sooner or later you will need to embrace stranger-hood. It’s the normal course for a Christian.”

Notice—

No one stood out for Naboth.

After he anoints his successor, Elisha, the prophet Elijah disappears from the narrative. The Book of Kings shifts to reporting on the war which breaks out between Israel and Syria. Only with Yahweh’s help does King Ahab repel the host of King Benhadad of Syria. Victory in hand, Ahab then retires to his royal residence in the countryside at Jezreel in order to enjoy his hard-won peace.

These are the circumstances of the passage.

Adjacent to the king’s country estate is a vineyard tended by a Jew named Naboth. His name means “prophets.” Proving that idolatry is not a victimless crime (nor is God its only victim), no sooner has Ahab retired to his rural retreat than he begins to covet what belongs to his neighbor.

Initially at least, Ahab is not corrupt; he’s a good capitalist. He offers Naboth an exchange of land or the equivalent value in cash for the vineyard.

Ahab makes Naboth an offer he can’t refuse.

And Naboth refuses it.

He stands out.

He is not afraid to confront Ahab as a worshipper of Yahweh, “Yahweh forbid it that I should sell the inheritance of my fathers.” Naboth means that literally. According to Leviticus 25, it is unlawful for God’s people to sell an inheritance. That Naboth not only cites the command but obeys it is but an indication that he is one of the faithful few whom the Lord has preserved in Israel.

Naboth’s refusal to sell his inheritance wounds Ahab’s pride, and the king retreats home to pout. But just because a president is pathetic does not mean he is not dangerous. Once again Ahab gets another to do what he lacks the gumption to do. He tells his wife knowing that she will act for him without restraint. Whereas the king had recapitulated David’s sin, coveting what belonged to his neighbor, the queen now completes the recapitulation. Jezebel sends out letters, sealed under her husband’s name, designed to result in Naboth’s murder— just like David sent word to arrange for the husband of Bathsheba to be moved to the front lines. Jezebel’s letter proclaims a community-wide fast. Such a proclamation suggests either a calamity looms on the horizon or a serious crime has been committed.

Pay attention to the details in the passage:

The queen’s letters assemble “All the men of the city, the elders, and the leaders who lived in Jezreel.”

And “they all do as Jezebel told them.”

None stand out.

The idolatrous ruler cows and corrupts those under his rule.

The sealed letters gather the whole town in collusion.

As commanded by the queen, the town puts Naboth at the front of the crowd. On either side of Naboth they place two accomplices from whom they suborn false testimony before a sham trial in a kangaroo court.

Notice the charge against the faithful Jew, blasphemy: “Naboth cursed God and the king!” The charge is outrageously ironic given that it’s levied by idolators.

Without even the pretense of a verdict, like another faithful Jew, Naboth is handed over and led outside the city and executed in a judicial murder.

Jezebel could have simply ordered one of her soldiers to kill Naboth. The queen’s excessively expansive scheme ensured that everyone who knew of the plot was a part of the plot. Just so, there was no witness to their crime because they were all a party to it.

Except—

There was one witness: the Lord from whom no secrets are hid.

Naboth’s body was buried in the ground but his blood cried out to heaven for justice. Naboth’s blood adds its voice to the refrain that recurs throughout the Bible:

““How long, O Lord, will You refrain from judging and avenging our blood?”

There are no unsolved cases with the Living God. The Lord sees. He is not only our Judge. He is able to give eyewitness testimony to our crimes.

And so Jesus encounters Elijah and Jesus dispatches Elijah to confront Ahab once again. Remember, Elijah is still Israel’s Most Wanted Man. But Elijah makes no scruple about endangering himself to stand before God’s enemies and hand over the word that the Lord Jesus has given him to declare,

“Have you killed, and also taken possession? “Thus says the Lord: In the place where dogs licked up the blood of Naboth, dogs will also lick up your blood.””

The speaking of the word of God is God. Thus, for Ahab to receive this word of the Lord is for the king to stand before the Judge. And like the prophet Nathan to David (“You are the man!”), the word works on Ahab. Like the prodigal son in the far country, “he comes to himself.” Ahab suddenly realizes that he is “dead in his trespasses.”

He tears off his clothes, in ritual mourning.

Naked, he puts sackcloth over his bare body.

And then Ahab commences a fast.

Having seen his crimes, the Lord now sees Ahab’s repentance.And God changes his mind.He forgives Ahab's sins.Which— let’s be clear— DOES NOT BRING NABOTH BACK!

Perhaps it’s unsurprising, but the mainstream press has done a poor job of making clear that Alexei Navalny, the dissident whom Vladimir Putin most certainly had murdered last week in his arctic prison, was a committed and articulate Christian. In his closing remarks at his 2021 sham-trial, Navalny testified plainly to the Christian convictions which animated and informed his resistance to authoritarianism.

Navalny told the court:

“The fact is I am a Christian. That I am a Christian usually sets me up as an example for ridicule in the Anti-Corruption Foundation, because mostly our activists are atheists, and I was once quite a militant atheist myself.”

It’s not hard to be an atheist when the leaders of the church and so many of its members support a corrupt, lying authoritarian.

And then Navalny added:

“But now, I am a believer, and that helps me a lot because everything becomes clearer. There are fewer dilemmas in my life, because the Bible, in general, is more or less clear what action to take in every situation. It’s not always easy to follow this book, of course, but I am actually trying. While certainly not really enjoying the place where I am, I have no regrets. On the contrary, I feel a real kind of satisfaction. Because at some difficult moment I did as required and did not betray the commandment.”

Specifically, Navalny said, he was motivated by the words of Jesus:

The Greek word translated into English as righteousness (dikaiosune) is the same word for the English word justice.Blessed are those who are ravenous for justice.“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be satisfied.”

Here’s my question:Was Navalny wrong about God?Was he wrong that the true God is a God of justice?

Here’s my question:Was Navalny wrong about God?Was he wrong that the true God is a God of justice?After all, the Lord sees Ahab’s repentance and the Lord changes his mind. The Lord saw. The Lord hears Naboth’s blood crying out from the ground, and the Lord changes his mind?

The Lord passes over Ahab’s sins.

But Naboth’s blood does not cry out from the ground for forgiveness.

It demands justice.

As New Testament scholar Reginald Fuller insists:

“Forgiveness is too weak a word” to serve as shorthand for the gospel.

In Romans 3, in the midst of his argument about justification, Paul includes a claim that is as intriguing as it is often ignored.

First, Paul announces that “all are justified by God’s grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus.” So far so good— fairly familiar stuff.

Next in the logic chain, Paul explains that sinners are redeemed in Christ Jesus exactly because God the Father put forward God the Son “as a propitiation by his blood to be received by faith.” In other words, the Son’s self-offering is a sacrifice that appeases the wrath of the triune God. This self-offering includes you to the extent you receive it in faith. Again, this is astonishing but it is not surprising. It’s Gospel 101. Not only is it familiar, it sounds like Paul’s still speaking about forgiveness. But then, after he’s specified the What and the How of the gospel, Paul lays down the Why.

Why has the Father elected to redeem us through the Son whose blood he put forward as a propitiation for sin? Paul’s answer— pay attention: “This was to show God’s justice, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over former sins. It was to show his justice at the present time, so that he might be just.”

“This was to show God’s justice, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over former sins. It was to show his justice at the present time, so that he might be just.”

Thus—

Jesus is not simply God’s justification of sinners.Jesus is God’s justification of God.Again and again in scripture, the Lord demands justice for those who prey upon the poor. Again and again in scripture, God sends his prophets to announce impending judgment for his people’s idolatry and unfaithfulness, their sin and outright evil. But again and again in the Bible, just when God’s gavel is about to crack, God changes his mind.

He changes his mind.

He does not put wrongs to right.

He passes over sins.

To anyone who actually reads it, the offense of the Old Testament is not that God is angry and judgmental. The offense of the Bible is that God is so outlandishly, unjustly patient.By the time you get the end of the Book of Kings, you’re not left troubled by God’s wrath. By the time you come to 2 Kings 25.30, you’re left wondering, “How can God let them get away with this?”

If anything, the God of Israel is not angry and vengeful; in fact, by the Bible’s own estimation, the Lord is irresponsibly indulgent.

Again: “[The self-offering of the Son] was to show his justice at the present time, so that he might be just.”

Translation: Heretofore, God had not been just.

No doubt, Naboth wondered where in the hell was the God of justice as he was handed over and led outside the city.

According to the apostle Paul, before the cross is about us. It is about God.In putting forward God the Son on the cross, the triune God is actually justifying his own behavior. Finally, God shows that he is just by executing his judgment upon Jesus on behalf of those who are otherwise guilty and undeserving.

The patience of the Father culminates in the passion of the Son.The innocent Jesus, innocent because he fulfilled the double love commandment, offers himself on behalf of the guilty. In being handed over, in being condemned under a charge of blasphemy, in being led outside the city to what the Bible calls “the winepress of God’s wrath,” God the Son carries with him all the sins sinned against every Naboth. And then on the cross, the God the Father finally cracks the gavel and pronounces the judgment on Jesus. In doing so, the triune God displays his justice, giving sin what it deserves.

Only, the Judge is judged in our place.

Which— still— DOES NOT BRING NABOTH BACK!This is why the gospel is not gospel if the crucified one stayed in the tomb.As Paul continues his argument in the epistle, Christ, who died for our trespasses, was “raised for our rectification.”

Rectification—

Christ was raised for God’s creation to be put to right. Christ was raised for God’s justice to be complete. Christ was raised as the first fruit.

As the theologian Paul Hinlicky writes:

“The promise of the resurrection is the promise of the reversal of worldly injustices and the public justification of the justice of God to the eternal comfort of every innocent victim of human and superhuman malice at the culmination of the project of creation. God's will must finally prevail in this way, or we do not believe that God in the Christian sense exists whatsoever. That atheism is of course a human possibility. But it is not a Christian possibility.”

In other words, God is getting Naboth back.

If not, if there is no ultimate justice— justice that redounds all the way back through the past, righting every wrong— then it’s not the case that the God of the Bible is wicked.

It’s that the God of the scriptures is not.

Immediately after his murder, the Free Press published letters Alexei Navalny had exchanged with the former Soviet dissident Natan Sharansky.

Sharansky, a Jewish journalist, had been a prisoner in the same Gulag during the 1970’s about which Sharansky wrote a memoir entitled Fear No Evil. After reading the Fear No Evil, Navalny wrote to Sharansky, and Sharansky replied with two letters of his own. What’s striking about their correspondence is how replete it is with scripture and the moral clarity the Bible demands.

In his final letter to Sharansky, dated April 11, 2023, Navalny concludes with this confession of faith:

One day there will be what was not; and there will not be what was.

“In your alma mater— that is, this Gulag— everything is as it was. Traditions are honored. On Friday evening, they let me out of solitary, today on Monday—I got another 15 days. Everything according to the Book of Ecclesiastes: what was, will be. But I continue to believe that God will correct it and one day there will be what was not. And will not be what was.

Hugs,

A”

One day there will be justice.

And injustice will not be.

Or rather—

One day what was finished on Calvary will be fulfilled in New Creation.

That is—

One day God will stand out.

Which, of course, is exactly what we say at the end of the Great Thanksgiving, “when Christ comes back in final victory and we feast at his table.”

With Naboth.

Some come to the table.

And with bread and wine, point to the future.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 23, 2024

The Return of the Big Lie: Anti-Semitism is Winning

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Here’s my most recent conversation with my friend Rabbi Joseph.

We discussed Dara Horn’s article in The Atlantic, “The Return of the Big Lie: Anti-Semitism is Winning.”

Show NotesThe conversation explores the rise of antisemitism among the most educated people in America, as discussed in Dara Horn's article. It delves into the shift in liberal values and the toxic political environment that has contributed to the demonization of Jews. The distinction between criticism of Israel and antisemitism is examined, along with the persistence of anti-Semitic myths and conspiracy theories. The need for dialogue, reflection, and reconstitution of relationships is emphasized, as well as the importance of recognizing the value of Jewish survival. The failure of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives in combating antisemitism is discussed, as well as the fear and challenges faced by Jewish students. The conversation concludes with a call for institutions to engage in meaningful conversation and reflection to address the current climate of hatred.

TakeawaysThe most educated people in America are falling for antisemitic lies, highlighting the need for dialogue and reflection.

Criticism of Israel is not inherently antisemitic, but the demonization and dehumanization of Jews is a cause for concern.

Institutions, including universities, need to address the rise of antisemitism and create an environment conducive to living together.

The toxic political environment and the spread of conspiracy theories contribute to the persistence of antisemitism.

There is a need for a return to a time when Jews didn't have to constantly prove their right to exist and institutions were safe spaces for Jewish students.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 22, 2024

Justification is the Reverse of Predestination

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

The lectionary passages assigned for the Second Sunday of Lent center on the Reformation’s linguistic rule for preachers who would speak gospel, otherwise known as the doctrine of justification by faith alone— apart from works.

Thus, in Romans 4 the apostle Paul recalls Genesis 22 to assert that faith in the message of Christ and him crucified, at which Peter recoils in Mark 8, is the only criterion by which God reckons us righteous before his judgment.

Typically, preachers interpret this rule for preachers to mean that the hearer’s response (belief) is the sole property according to which God will save them, which of course makes faith exactly what the Reformation sought to unseat— an anxiety-producing human work. For instance, if your faith supplies the righteousness a holy God requires for salvation, then how can you ever establish that your faith is sufficient? Did you venture forth at the altar call out of authentic faith? Or did you do so in a moment of ecstatic experience or under the duress of peer pressure? And if it was a genuine gesture of faith, then how does your present compare to it? Does it look more mountain or mustard seed?

While I insist that I belong to a tribe of Jesus’s friends whose doctrine is actually justification by works apart from faith, the Reformation’s rule has become, in the Christian cohorts who retain it, the very bondage from which Martin Luther worked to free troubled consciences. That this is so illustrates Robert Jenson’s caution about the church’s slogans:

It’s sadly ironic that so many should now construe the rule for gospel as a law.“The problem with slogans is that as over time they become increasingly necessary, they just so tend to acquire live of their own, and then can become untethered from the complex of ideas and practices which they once evoked.”

After all, it should appear obvious that justification does not denote a human work of any kind given that the slogan renders its grammar in the passive voice: You are justified in Christ alone by grace alone through faith alone according to scripture alone. What the Reformers revolted to recover becomes clear when the rule’s speech is flipped from passive to active voice: God-in-Christ is— graciously, apart from works— making you righteous (because the gospel is a word in which Christ gives himself to you).

In other words, justification conveys just this surprising, perhaps unsettling, news:

The doctrine of justification insists upon nothing other than the one-way love of God.You are not the protagonist of the Story you call You.

Justification implies not predestination so much as post-destination. Nothing exposes the weakness of justification as a word of law not gospel quite like the resistance it elicits once one points out how it seeks to center God as the active agent.

The Reformers intended to issue the claim in bracingly clear terms:

All things happen by God’s will.

This is merely a restatement of Martin Luther’s insight in the Bondage of the Will:

Luther goes on to conclude that our resistance to the doctrine of predestination is truly just a distrust of God. Just so, our discomfort with justification’s correlative reveals our functional atheism.“For if you doubt…that God foreknows and wills all things, not contingently but necessarily and immutably, how will you be able…to rely on his promises?”

The church’s slogan about our justification simply names that God wills in our act of gospeling just as God works in our response of faith— because faith is neither an attribute nor an accomplishment but a gift of God the Spirit. Hence, more so than we’d like countenance, the linguistic rule known as the doctrine of justification betrays essential connective tissue to texts like Exodus 9.12, in which Yahweh hardens the heart of the very Pharaoh to whom Yahweh has dispatched Moses to plead for mercy on behalf of God’s people.

Notice—

The doctrine which has centered the centrality of individual decision (for Christ) is actually a rule of speech that celebrates God as the active agent in all of the salvation story.

Surprisingly then, Romans 4 is no less a troublesome text for autonomous individuals than Exodus 9.On the dialectic between the Lord’s agency and our own, Jenson writes:

God is said both to blind and deafen Israel and to send prophets in the hope that they may see and hear and repent. This is not mere incoherence. It is rather one manifestation of a logic that runs through all scripture.

The questions always come up, wherever the realities of God and faith are taken seriously. Putting them in the popular language about salvation: If salvation depends wholly on God, and if not everyone is saved, then if God does not choose to save me, what is the use of my faith or works? Or if I am responsible to open my own eyes, how can I fully rely on God as my Savior, since I may at any moment undo everything by failing that responsibility?

What we must come to understand is that neither question is appropriate, for the simultaneity of “God decides and works all things” and “see, hear, and be saved” is itself the truth about our situation with God.Believers are bound to “work out [their] own salvation,” precisely because “it is God who is at work” in them (Phil. 2:12–13). Both propositions can be true, and true only together, because between God’s will and a creature’s will there is no “zero-sum game.”

When you and I must decide some matter, to the extent that you choose I do not, and to the extent that I choose you do not. Thus we are always negotiating, for we are both finite creatures with a limited scope for choice. But it does not work that way when God decides to open my eyes and I must, in response to his simultaneous appeal, myself decide to open my eyes. High medieval Scholasticism’s statement of the relation between God’s choice and ours is so simple and so patently right that it is very hard to grasp: God’s will is impeded by nothing; therefore if he chooses that I shall do x, I will do it; and if he chooses that I shall do x of my own free will, that is how I will do it.”

In this way, the doctrine of justification is no more than a riff on the doctrine of creation ex nihilo. That is, God does not act upon his creatures in the same way his creatures act upon each other; in fact, he does not act upon them at all. What God does is speak creatures into being ex nihilo, continuously and eternally.

The Creator both hardens Pharoah’s heart.

Whilst Pharoah freely hardens his heart.

Both statements must be true if the creatio ex nihilo is true.

Just so—

Our justification is a matter of the same God who hardened Pharaoh’s heart.The Creator gifts us faith through the gospel.

Simultaneously, through the Lord, we freely open our hearts to the gospel’s content, Mary’s boy who lives with death behind him.

Ironically, such an uncompromising emphasis on God’s active agency throws us back onto what the slogan originally intended to secure, trust in God alone.

This is not about an abstract deity “picking” from outside of time. Rather, it describes the God whose reality and will are disclosed only in the event of speaking the gospel, who is the absoluteness and unconditionality of the gospel. The absoluteness of the gospel, Jenson writes, is the absoluteness of that very word the hearing of which, and only the hearing of which, is the event of our freedom before God.

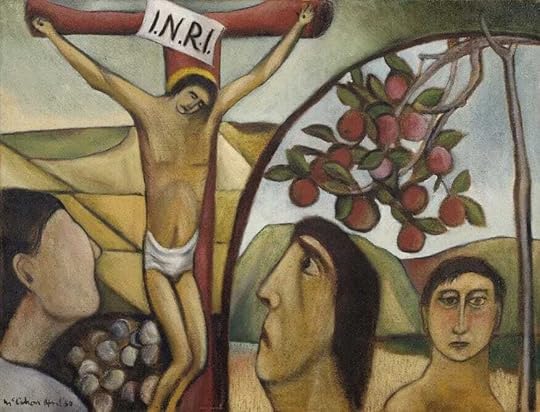

(art by Lyuba Yatskiv)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 21, 2024

Puzzle Pieces

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Hi Friends,

I think you will appreciate the first session we had with my friend Rabbi Joseph on his book. Don’t forget, if you have a question or comment for Rabbi Joseph, you can drop it in the comments here below or you can shoot me an email.

Show Notes:SummaryIf you haven’t registered for the webinar, you still can do so HERE.

In this conversation, Rabbi Joseph Edelheit joins us to discuss characters from the Hebrew Bible and the importance of dialogue between different faith traditions. The participants express their gratitude for the opportunity to engage in dialogue and share their missing puzzle pieces with one another. They emphasize the need for Christians to learn from the Hebrew Bible and recognize the ongoing dialogue within it. The conversation highlights the importance of taking risks, cultivating hope, and embracing different perspectives.

This conversation explores the importance of education, the need for self-reflection and growth, and the dialogue between Christians and Jews. It also delves into the mutual vocations of the Church and Israel, the role of Christians in dialogue with Jews, and the development of Judaism and Christianity. The conversation highlights the importance of sacrifice in Christianity, the limitations of the lectionary, and the need for a broad understanding of scripture. It also discusses the value of the Bible for prisoners, the significance of interfaith relationships, and the Mishnah and Talmud in Jewish tradition. The impact of the destruction of the temple and the importance of Old Testament figures are explored as well. The conversation concludes with a preview of the book's chapters and a closing blessing.

TakeawaysEngaging in dialogue with individuals from different faith traditions can lead to personal growth and a deeper understanding of one's own beliefs.

Christians can benefit from studying the Hebrew Bible and recognizing the ongoing dialogue within it.

Cultivating hope and embracing different perspectives are essential for meaningful dialogue and spiritual growth.

Taking risks and sharing our missing puzzle pieces can lead to transformative experiences and connections with others. Education is a crucial aspect of personal growth and development.

Self-reflection and the willingness to learn from others are essential for personal growth.

Dialogue between Christians and Jews is important for mutual understanding and respect.

The Church and Israel have distinct vocations that should be acknowledged and respected.

Christians have a responsibility to engage in dialogue with Jews and learn from their perspectives.

The development of Judaism and Christianity has shaped their respective beliefs and practices.

The sacrificial aspect of Christianity is often overlooked or misunderstood.

The lectionary can limit the exploration of scripture and should be supplemented with a broader understanding.

The Bible can provide comfort and guidance for prisoners.

Interfaith relationships can foster understanding and appreciation between different religious communities.

The Mishnah and Talmud play important roles in Jewish tradition and interpretation of the Torah.

The destruction of the temple had a significant impact on Judaism and Christianity.

Old Testament figures are important for understanding the foundations of both Judaism and Christianity.

The upcoming chapters of the book will explore various biblical characters and their relevance today.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 20, 2024

How Does Faith Make Us Righteous?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Genesis 22 & Romans 4

In this week’s lectionary epistle, the apostle Paul cites Genesis 22, which is also assigned for the Second Sunday of Lent. Recalling the Lord’s summons upon Abraham, Paul arrives at this critical if often confused conclusion:

“Therefore his faith "was reckoned to him as righteousness." Now the words, "it was reckoned to him," were written not for his sake alone, but for ours also. It will be reckoned to us who believe in him who raised Jesus our Lord from the dead, who was handed over to death for our trespasses and was raised for our justification.”

Romans 4.22-25

Note, the words translated alternatively into English as “righteousness” and “justification” are the same root word in Greek. Thus, Jesus was raised for our righteousness.”

This passage from Romans is important source material for the Reformation slogan, "justification by faith apart from works.” While I fear a good many contemporary Protestants have unconsciously adopted a different slogan altogether (justification by works apart from faith), those who still affirm the original maxim nevertheless often go astray with it.

Just so, the question:How does faith make us righteous?Many answers will fix upon that word in the lectionary text reckoned and align it with a word which the apostle does not use, despite. In other words, many Christians will respond to the question by insisting that faith makes us righteous in that the Father credits the Son’s atoning work to those in whom he finds faith; that is, despite what God sees when he regards a sinner, for Christ’s sake God credits you as what you are not, righteous.

The language of the financial ledger (credits) is both intentional and incomplete.

True, God creates ex nihilo by his word; the Lord’s speaking makes it so. Therefore, we must agree that what God declares to be righteous is, in fact, righteous, all appearances to the contrary perhaps. Just as God says light and there was light, God looks at you in your faith and declares “righteous!” and, presto, there is righteous you. Any further answer to the how question, we might conclude, is the stuff of mystery. Indeed were it not a mystery we would quickly move to mechanize the process. This, I think, is exactly what they who quietly abide the alternate slogan (justification by works apart from faith) do.

As Robert Jenson notes, although preachers often credit Martin Luther with the above juridical account of how faith makes us righteous— awkwardly— this is not how Luther actually understands the means by which the Lord makes us righteous.

Our righteousness, that is, is not a legal fiction.

In The Freedom of the Christian, Luther says that when we have faith— itself a gift— then we simultaneously possess, and truly so, all the salvific gifts of God, which of course includes his righteousness along with love and joy and so forth. Once again, how does this become our possession? How does faith makes us righteous?

Luther offers two ways God justifies through faith.

The Answer from the LawLuther notes that placing our trust in God is the highest honor we can bestow upon God; in fact, belief in the true God just is obedience to the first table of the Decalogue. Faith is not an ideal to which creatures can aspire; faith is called out of us by the first commandment. Just as your obedience to the other commandments is moot if you do not obey the first commandment by believing in the true God, so also your obedience to the first commandment results, however slowly and stubbornly, in obeying the subsequent commandments.

From obedience to the first table of the law, obedience to the second table surely follows; therein, we become righteous like the Giver of the tables. As Luther writes, “If we trust God, then we will seek to fulfill his stated will.” And this is the same logic Luther uses in his catechism for children, “We should fear and love God, so that we…”

The Answer from the GospelUsing Aristotle, Luther argues that hearing the gospel itself makes us righteous— really righteous not merely reckoned so. We become what we are hearkened to. When we hear the Word of God, we are shaped by the address and conformed to its content. The Word communicates its properties such as love and peace and generosity.

As Jenson puts it,

The Answer to How is Who“Thus when God declares those who hearken to the gospel righteous, this is a judgment of fact. When the sinner Jones is grasped by the gospel, “Jones is righteous” is straightforwardly true; the puny sins with which Jones still tries to shape his life cannot stand against God’s righteousness inhabiting him. Justification of the sinner is a mystery but not a paradox or fiction.”

The answer to the how question may still not be explicit.

Simply, the gospel makes righteous those who hearken to it because the gospel is a word in which Christ gives himself to us.

It is a rule of theology that God’s attributes and God himself are the selfsame reality. They cannot be separated. You cannot possess Christ’s righteousness apart from Christ. Faith makes the believer righteous because faith comes by the gospel which is the word that gives us Christ.

Luther states it according to the principle:

“Faith makes us personally and actually righteous because faith is a transforming and ruling presence in us of the righteous one himself.”

Of course, this is nothing other than the New Testament’s teaching about good fruit flowering from a vibrant vine or a healthy tree.

Once you understand that the gospel is God’s means to elicit faith through which Jesus Christ, will inhabit and shape your soul, then you can begin to see why it’s a thoroughly silly question to ask, “Well, isn’t there something we need to do now that we have faith?” That question presumes you’re still in charge of the you you call you.

How does faith make us righteous? It gifts us the Righteous One.And this is the point the Reformation was always after.

Jesus is the active agent disguised behind the word faith.

This is why apart from works is so essential to the formula.

Christ is the one who makes us righteous.

(“Slave Preacher, Harper’s Magazine, 1855)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 19, 2024

Listen Again to the Song at the Cross

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Psalm 22

Not only is one-third of Mark’s Gospel a passion story, much of that passion story is a prophetic enactment of songs from the Old Testament:

Just like the Suffering Servant portends, Jesus stands mute before those who accuse him of blasphemy.

Despite his innocence, Jesus suffers smiting and spitting just like the song in Isaiah 50 augurs.

Christ cries out “I thirst” according to the script in Psalm 69.

Christ commends his Spirit to the Father, echoing the thirty-first Psalm.

The soldiers cast lots for his clothes. He’s crowned in mock majesty. Naked and bloodied, he endures the shaming eyes of bystanders and passersby— all of it according to the songs.

And finally in Mark we hear Jesus cry out from another song, Psalm 22:

“My God, my God why hast thou forsaken me?”

ἐγκαταλείπω.

Utterly abandoned.

February 18, 2024

Christ’s Sinnerhood

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

1 Kings 19.9-18

I sometimes joke, “I love Jesus; it’s his friends I can’t stand.” Happily however, the communion of saints names the gift of friends we would not have if we had not the Lord Jesus. Because Jesus is not dead and hijacked me into his service, I providentially crossed paths with Alfred Dewayne Brown nearly a decade ago. He has remained a friend to me just as I have continued as a pastor to him.

As I have shared with you before, when he was twenty-five, Dewayne was charged in the murder of a police officer and cashier during a botched robbery of a cash check store in Houston. Upon his arrest, Dewayne had insisted that he’d been at home alone and that his girlfriend, whom he’d called from a landline in his apartment, could verify his alibi. The phone record was never recovered, and the prosecutor threatened Dewayne’s girlfriend with contempt, which meant she’d put her child at risk in the foster care system if she did not revoke her testimony.

Dewayne fit the profile for a convenient scapegoat and an easy conviction.

He’d grown up poor.

He’d dropped out of school in the ninth grade.

His skin was the right color.

So, a Texas doctor ginned up Dewayne’s IQ from sixty-seven, which qualified him as mentally handicapped, to seventy, which qualified him for execution.

Despite any forensic evidence whatsoever or eyewitness corroboration, an all-white jury sentenced Dewayne to death in 2003. He spent the next twelve years in a sixty-square-foot single cell. Dewayne had already been on death row for two years when he met my friend Brian, a fast-talking, wise-cracking white-collar defense attorney in D.C.

Brian’s firm took Dewayne’s appeal pro bono. Neither Brian nor the firm considered the possibility that Dewayne was innocent; that is, not until the initial interview after which Brian walked out of death row and threw up in the parking lot, realizing the likelihood that he would not be able to save an innocent man from death and that he would carry that guilt to his own death.

Brian gave the next decade of his life to freeing Dewayne. The case jeopardized Brian’s career. The time away and the depression almost ruined his marriage. By luck or by providence, Brian discovered that District Attorney Dan Rizzo had hidden the phone record, which corroborated Dewayne’s alibi. He also had a letter sent to Dewayne from a witness, the details of which would’ve cleared Dewayne, but the prosecution never told Dewayne what it said.

Dewayne can’t read.

In other words, Dan Rizzo was guilty of sending Dewayne to his death knowing his innocence from the very beginning. The evidence exonerating Dewayne was discovered in 2013. Dewayne wasn’t released from prison until 2015 when the State of Texas decided not to retry him. Five years later, the Harris County Assistant District Attorney’s office filed charges against their former DA, Dan Rizzo.

I called Dewayne when I saw in the news that the man who had unjustly condemned him would himself face justice.

“What do you make of the news?” I asked him.

“It’s an act of God, man.”

“Did you ever dream the crooked DA get what was coming to him?”

“Sure I did— I knew so. He may seem slow to us, but God’s always at work. And he doesn’t look past wrongdoing neither. I knew justice was coming.”

In the confrontation at Mt. Carmel, the Lord had answered Elijah’s prayer with fire and the Lord’s unfaithful Israel had responded, “Yahweh is indeed God!” But then, they all go back to their homes and resume their idolatrous lives. Meanwhile, Jezebel, the pagan Queen of Ahab, issues a warrant for Elijah’s capture and execution. Despairing over the futility of his call, Elijah forsakes the battlefield because he believes that he’s the only one left in Israel who has remained faithful to Yahweh.

After wandering in the wilderness for forty days, Elijah comes to the Horeb mountains of which Mt. Sinai is the peak. There Elijah finds the cave— not a cave, the cave; that is, the cleft of the rock in which Moses had hid as the Lord passed by him. At the cleft, the Word comes to Elijah and asks a question.

It is rarely good news when the Lord shows up with a question for you.God speaks and summons. The Lord seldom asks, “Would you consider dropping your nets and coming to follow me?” The God from whom no secret is hid does not often ask questions.

When he does, you’ve been caught in the act:

“Adam, where are you?”

“Cain, why is your face downcast?”

“Elijah, what are you doing here?”

In the context of the plot, you should hear the Lord’s question, “Elijah, what are you doing, here?” As in, “Elijah, why have you left Israel? Why are you so far outside your assigned work area?”

Remember—

The Troubler of Israel has evacuated to the southern-most edge of Judah.

The shepherd has abandoned his flock, having concluded that they are irreparably lost sheep.

Elijah replies to God’s question by responding with a severe accusation against his fellow Israelites. He dismisses them as entirely hopeless in their sins and he casts their idolatry against the backdrop of his own faithfulness. Elijah goes to law with God (never a good idea). “I have been very zealous for the Lord,” Elijah protests, “for the Israelites have forsaken your covenant…I alone am left, and they are seeking my life, to take it away.”

Elijah’s complaint is that God’s people have forsaken God’s covenant with them. And as Elijah suggests, their sin has the character of totality about it. That is, once you break the first commandment and have a god other than God, then killing and lies, greed and cheating and dishonor surely follow.

This is but a reminder that what sets the God of Israel apart from the barren deities of both antiquity and today is that the God of the Bible creates with moral intention.Baal never told his worshippers how to live in the world; Baal simply did or did not respond to his adherents’s petitions.

As Robert Jenson writes:

[By contrast] “God’s work on creatures is not random but morally purposeful. He creates and redeems us to be this and not that: faithful rather than questing, pious rather than neglectful, communal rather than autonomously individual, chaste rather than liberated, helpful to the fabric of community rather than harmful to it, mutually pleasured rather than covetous.

The Lord does not dispute Elijah’s indictment against the people. He instead instructs Elijah to stand on the mountain before the Lord. Typically, readers treat the first three elements of the theophany in contrast to the fourth. But the wind and quake and fire are not antithetical to the Lord’s presence, they are emanations from it.

As the biblical scholar J.C. Sikkel illustrates it:

The wind and the earthquake and the fire herald the king who arrives in a still, small voice.“When a king visits one of his cities, his coming is preceded by canon fire, the approach of cavalrymen and mounted police, and a ceremonial procession of high officials. All of this announces that the sovereign is on his way, even though the king himself does not travel with this vanguard. He comes at the end of the procession after his coming has been announced by all this pomp and splendor.”

Just to be clear—

It is a voice that encounters Elijah.

It is not “the sound of sheer silence” as some translations render it.

We know it is a voice that encounters Elijah because the first time God asks Elijah, “What are you doing here?” verse nine says it was the Word of Yahweh who asked the question. After the theophany, the question remains the same, but verse thirteen tells us that this time it was the Voice (same word, qol) that asked God’s question.

This is the voice of the Messenger of Yahweh that had fed and consoled Elijah earlier in the wilderness. This Messenger (malak Yahweh) is both one with Yahweh yet also other than Yahweh. The voice belongs to one who is God but who is simultaneously other than God. In other words— the ancient church fathers saw this clearly— the king whom fire and wind and earthquake herald is the Second Person of the Trinity.

The still small voice belongs to the Son of God who will be Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim.“All the Bible is about me,” the Easter Jesus says to the disciples on the way to Emmaus.

Therefore—

To listen to the still small voice is not (as I’ve been exhorted in myriad clergy gatherings) to retreat silently within your self. To listen to the still small voice is not to attempt to discern some ill-defined vagueness.

To listen to the still small voice is to listen to Jesus. Yet this is no more consolation for us than it was for Elijah, for this still small voice sounds so unlike the Jesus we think we know.After the fire and the wind and the earthquake have subsided, Jesus speaks of a storm of judgment coming to God’s people.

A few years ago, Dewayne and Brian gave a presentation to a group of law students at George Mason University. I went with them to sit with Dewayne while his attorney talked shop with future practitioners. Having listened to him to tell his story to the students, I once again marveled at his expressions of forgiveness over the wrongs done to him by crooked cops and ambitious lawyers, a prejudiced system, and an indifferent society.

“I’ve forgiven all that,” Dewayne told me in the same sort of classroom where lawyers who had turned a blind eye to his innocence were once trained into a supposedly blind justice system.

“How is that possible?”

He shrugged his broad shoulders and smiled his child’s smile.

“I can let go of what they done to me because I know God doesn’t look past it.”

The theologian Miroslav Volf now teaches at Yale. He grew up in the former Yugoslavia where, as a young pastor, Soviet interrogators tortured him. In his seminal book, Exclusion and Embrace, he attempts to recover the coherence of the category of God’s wrath.

He writes:

“A non-indignant God would be an accomplice in injustice, deception, and violence…My belief in divine vengeance will be unpopular with many Christians, especially theologians in the West. To the person who is inclined to dismiss it, I suggest imagining that you are delivering a lecture in a war zone. Among your listeners are people whose cities and villages have been first plundered, then burned and leveled to the ground, whose daughters and sisters have been raped, whose fathers and brothers have had their throats slit.

The topic of the lecture: a Christian attitude toward violence.

The thesis: we should not retaliate since God is perfect non-coercive love. Soon you would discover that it takes the quiet of a suburban home for the birth of the thesis that human nonviolence corresponds to God’s refusal to judge.

In a scorched land, soaked in the blood of the innocent, it will invariably die. And as one watches it die, one will do well to reflect about many other pleasant captivities of the liberal mind."

In Elijah’s contest on Mt. Carmel, the prophets of Baal are so impotent they can make the barren deities of Canaan appear as harmless trivialities. But, for example, in addition to Baal, Jezebel and her prophets worshipped the Canaanite god Moloch, to whom devotees sacrificed children. The reason God’s law prohibits pork is because when a human baby was not available for sacrifice Canaanites would offer a baby pig in its place; therefore, the Torah forbids pork in order to prevent any resemblance between Yahweh and Moloch.

When Elijah charges God’s people with forsaking the covenant, he’s accusing them of crimes more serious than praying for rain by the wrong name. When we forsake the covenant, there are consequences more severe than how we spend our Sunday mornings. For instance, in post-Christian Canada, euthanasia is now a leading cause of death. In a doom-scrolling culture, it is not hard to supply other exhibits of evidence.

The wrath of God is not arbitrary.It is righteous altogether.

That the Voice who encounters the recalcitrant Elijah belongs to Jesus makes it all the more critical we pay attention to the commands the still small utterance issues.

In our own sin and idolatry we tend to strip the signs (e.g., fire..wind..) from the words, but the both of them together make up the theophany.Without the Word which follows, the signs convey nothing for they leave Elijah unchanged. After all, when the still small Voice asks Elijah the same question the Word had earlier inquired of him, the prophet offers the very same answer, “The Israelites have forsaken your covenant…I alone am left…”

Of course, even Elijah knows that Obadiah has hidden away a hundred prophets faithful to the Lord. Elijah is so convinced of Israel’s ungodliness that he’s exaggerating the desolation of their situation. The Lord opts not to indulge Elijah’s despair and defeatism. “Go!” the Voice that is Jesus commands him. And what follows from the command to depart is the Lord’s explanation of the theophany.

Jesus issues three commands:

“You shall anoint Hazael to be king over Syria.”

“You shall anoint Jehu to be king over Israel.”

“You shall anoint Elisha to be prophet in your place.”

Jesus commands three anointings. The anointings are the explanation to the theophany. The men anointed in the name of Yahweh will be the rods with which Yahweh will chastise and punish his Israel. They will be instruments of God’s wrath.

Notice—

Like the signs that heralded the still small Voice, the judgments Jesus initiates are three-fold.

Hazael and Jehu and Elisha.

Wind and earthquake and fire.

Each of the latter corresponds with one of the former.

Sitting in the classroom at the law school, Dewayne repeated himself, “I can let go of what they done to me because I know God doesn’t look past it.”

I looked at him, unsure of what he meant. He nodded, understanding I didn’t understand.

“I can let go of all that because I know vengeance belongs to the Lord.”

He must’ve seen me balk at his use of the brute, old fashioned word.

“What— you’re a preacher; don’t tell me you don’t believe in God’s vengeance? His justice?”

“I may be a preacher,” I said, “But I’m also white and well-off. When the world’s rigged in your favor, you don’t have much need for God or his vengeance.”

He laughed.

And then he leaned towards me, suddenly and boldly serious.

“I can forgive all of it,” Dewayne said, “Because I know God damns every bit of it.”

Hazael and Jehu and Elisha.

Wind and earthquake and fire.

Notice—If each of the three anointings corresponds to one of the preceding signs, then we’re missing still a fourth judgment.Wind, earthquake, fire..But the passage speaks not of a judgment that corresponds to the still small Voice. That judgment comes when the Voice takes flesh.“On him,” the prophet Isaiah foresaw, “the Lord has laid the iniquity of us all.”

Of course, it’s true that the Voice arrives on the scene as the Friend of Sinners who announces the pardon of God. Yes, the Voice pronounces the forgiveness of sin. Certainly, the Voice eats and drinks with sinners and teaches his followers likewise to forgive sin.

But—

Jesus forgives sinners precisely because he’s going to die for them.The covenant with its commandments is not wrong. The law is holy, righteous, and good. The Lord does not look past our impunity. The crucifixion is not an injustice we visit upon Jesus. The crucifixion is the justice God visits upon us.

In himself.

In the human-who-is-God.

The cross is a true damnation.I realize a word like damnation tightens our collective sphincters, but as Christ’s death is the presupposition to his resurrection, God’s wrath is the dialectical presupposition to reconciliation.

“The Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all.”

Again, notice—

The Lord lays on him not the punishment due us all.The Lord lays on him the iniquity of every last one of us.That is, our sins.

The still small Voice is not a substitute for us.

The still small Voice is our sinner.

As Martin Luther lectured:

“Unless Christ was our sinner, we ourselves must be; but since through him we are not sinners, it follows that he was a sinner and had to be. If it were true that Christ is innocent and does not carry our sins, then we carry them and shall be damned in them.”

But how?

How are our sins Christ’s own sins?

Luther, following the Epistle to the Galatians, answers:

But how has Christ committed our sins?By “his intentional self-incrimination.”“Our sins are Christ’s not by means of some transcendent, super-historical transaction, in which Christ simply ‘regards’ our sins as his but by bearing our actual sins. Our sins are Christ’s by reason of his committing them.”

The Friend of Sinners sounds like a sentimental slogan.

But really, it means the still small Voice makes himself a collaborator to all our crimes.

He is the accessory to every bent cop and crooked DA. He is the partner in crime to every Putin. He is the accomplice to the spouse who cheated on you, the friend who betrayed you, the parent who abused you.

He is everything you’ve done. And left undone. Just so, the law’s accusation against him— and in him, you too— was just.

As Luther says:

The Gospel’s declaration“Behold, the lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world,” should be heard as Jesus himself declaring, “I have committed the sins of the whole world.”

He bears them all in his body— the body which, on the third day, the women come with spices to anoint.

Wind and earthquake and fire and voice.

Hazael and Jehu and Elisha and Jesus.

And there will not be another.

God has damned it all.

We were still sitting in the classroom at the law school.

A momentary silence had settled over us.

And then Dewayne said to me, “I don’t just forgive it. I feel bad for some of them who did me so wrong.”

“Feel bad? Why?”

“Well, I figure…their sins were big ones. And how they saw themselves and how they put themselves out to the world— it was all wrapped up in those sins. That means huge parts of themselves are dead and buried with Jesus. I feel bad for them. It’s got to be hard to go on in life with huge gaps in your story already in the grave.”

Your sins are forgiven.

They are.

But they are also a part of the Story you call You.

Which means, you’ve got holes in you that need to be filled.

So come to the table.

Jesus will give you himself to plug the holes.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 17, 2024

Tragically Engaged

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If. you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Here is my latest conversation with my friend Rabbi Joseph Edelheit. Together we spoke about The Atlantic article, The New American Judaism.

Show Notes: Summary

Rabbi Joseph will be joining us on Monday nights in Lent.

You can register HERE.

This conversation explores the challenges and transformations faced by American Judaism, particularly in relation to the evolution of synagogues and the changing demographics of Jewish communities. The conversation highlights the need for reflection and conversation in response to these changes. It also discusses the importance of religious communities in the face of global and local challenges. The conversation concludes with a discussion on the future of synagogues and the significance of sacrifice in Christianity and Judaism.

TakeawaysAmerican Judaism is experiencing institutional contraction and demographic shifts, leading to the closure of synagogues and the need for new forms of religious community.

The role of rabbis is changing, with a decline in the number of ordained rabbis and the emergence of lay people taking on para-rabbinical roles.

The challenges faced by American Judaism are not unique to the Jewish community, but are part of larger cultural shifts and changes in religious institutions.

There is a need for reflection and conversation in response to these changes, as well as a recognition of the importance of religious communities in addressing global and local challenges.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 16, 2024

Just This Offering

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Leading the gathered through Psalm 51 this Ash Wednesday, I noticed something as I followed along with the responsive setting. David’s indulgent confession of sin in Psalm 51 ends with this startling moment of recognition:

“…for you [God] have no delight in sacrifice; if I were to give you a burnt offering, you would not be pleased. The sacrifice acceptable to God is [only] a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.”

Surely this is a stunning epiphany to anyone who knows the Old Testament wherein sacrifices are frequent, systematized, and not only a delight to the Lord but prescribed by the Lord himself from Mt. Sinai.

Consider the remarkable dissonance. I realized on Ash Wednesday, only because my Bible was open flat on my lap, that immediately preceding David’s judgment against sacrifices is the contrary:

“Those who bring their thanksgiving sacrifice [as commanded in Leviticus] honor me…”

Declares God, in Psalm 50.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers