Jason Micheli's Blog, page 46

April 4, 2024

At Once Justified and a Doubter

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

This Sunday’s lectionary gospel passage is John 20.19-31.

“Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book.”

Uh….

What’s that about?

Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his…

April 3, 2024

Easter Faith is All About the Adverb

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Chris E.W. Green recently shared this Easter Vigil sermon preached by the theologian Robert Jenson.

We have said it: Christ is risen! The Lord is risen indeed!

So what am I supposed to say now?

That cry is all there is to say—about everything! About our lives and sorrows and hopes, about the destiny of the universe, about ancient and current and future human history.

If that cry is true, then literally everything is utterly different than we would have thought.

It is a sad thing for a preacher to come tagging after it with whatever little thoughts he or she may have put together.

Tomorrow morning, at the first Thanksgiving after the Resurrection, preaching will be again in place.

But tonight, at the very moment of the event…

Even the Gospels have little to say about the Resurrection except that it happened, that Christ is risen, risen indeed. The Gospels have no description of of what someone hiding in the tomb might have seen, no explanation of how the thing was possible, no interpretations of what it “really” means. The Gospels present only those angelic figures at the tomb in the morning, saying “He is risen,” just as we have done. Then they recount the stories of how people came to know about the Resurrection and to believe it had happened, by unexpectedly meeting with the Lord they knew had died.

And that is all even the Gospels do.

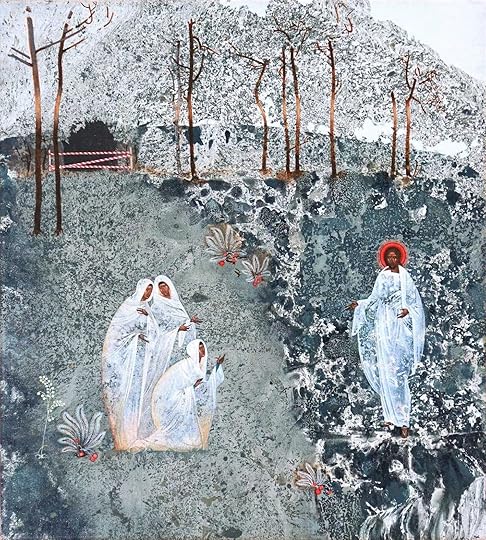

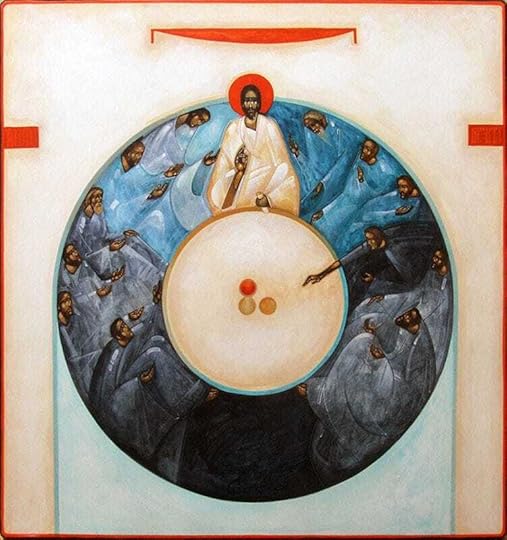

The church’s art has imitated the powerful silence of the Gospels, and has refused to portray the Resurrection, only showing the immediate before or after, the women coming with their spices, or Mary Magdalene meeting the newly risen One, or the tomb-guards bowled over on the ground—but never the event itself.

So—where the Gospels are silenced and Giotto’s brush is stilled, what am I to say or portray? The only hope I can see for preaching this night, is that adverb which appears when the cry is repeated: “He is risen. He is risen indeed.”

Why do we need it?

We need it because no sooner have we heard the tremendous claim—Someone is risen! Death is beaten! Death is beaten, and by the friend of publicans and sinners! By our friend! And perhaps even begun to believe it—than we are undone by the sheer size of the thing.

Between the address and the response, between the angelic “He is risen” and our responding “He is risen,” we already find it too much to handle, and need the reminder of that “indeed.”

Between the first and second “His is risen” the suggestion already presents itself—and has done from the very first days—that maybe all “He is risen” really means is something a little less wondrous and so a little less alarming than what it first sounds like saying. Maybe all it means is that his influence has continued after his death, or that his teachings are really great and should be followed even now, or that the resurrection is a symbol of something or other, perhaps of the general renewal of life out of death, or on and on through two millennia’s accumulation of bowdlerized versions that we can handle. We may even, somewhere in our hearts, a little hope it is something like that. We know how to deal with things like continuing influences and symbols of this or that and wonderful insights.

It would be a relief if the resurrection were something so trivial.And then there is the further wonder of it being a specific human individual, a male Galilean Jew of the time of Tiberius, whom God raised. Particularly in contemporary America, this also is almost too much for us to handle.

Why would God be so exclusive? If he is going to raise somebody why not all of us at once?Or at least one for each class and gender and ethnicity and so on? If this business about a resurrection of someone back there in Judea were perhaps a symbol of how we can all find new life if only we find the right self-help method—or whatever—that would be more sensible and easy to believe.

One of the half-dozen greatest theologians of the past century, Rudolf Bultmann, made the most sophisticated effort on these lines. What happened, he said, was that faith in God was born in the hearts of Jesus’ dispirited disciples, faith of which the only possible expression was “Our Lord lives!” Faith, he said, is a sufficient miracle. Now there is something in that, and we will come back to it.

But against all such cop-outs, including those of great thinkers, stands the adverb we have just confessed: He is risen—indeed! In a deed, in a fact, in an actuality, something happened and happened to Jesus.Not in the first instance to us or our faith in him, and not to his teachings or his influence, or to our obedience to them, but to him. A deed has been done by someone to someone; the resurrection was done to Jesus, and by the only one who could do such a thing, the God of life and death. That, and not one whit less is what the gospel claims and what the church, when she is even vestigially faithful, teaches.

Jesus actually—in-deed—lived, then actually died and was dead, and now actually lives. So he was not resuscitated, to die again later. Rather, he now looks back on his own death, not ahead to it as we still must do. There is one for whom death is over and done with, for whom death is an item in his biography, for whom death is not the future.

God has brought it to pass that death is not the universal end, since there is now one who has death behind him and quite another end before him, who looks back to death and forward to something very different, to that explosion of universal love which the New Testament calls the Kingdom of God.

To us, apart from this claim about Jesus, it surely looks as though death wins. To us, it looks as if the chief thing to be said about ourselves, about each and all of us is, “Tomorrow we die,” from which course the obvious conclusion is, “So eat and drink, there is nothing else.” To us, it looks as if the very universe were bound to entropy, as if its future were to be a sort of endlessly prolonged death, in which at every moment there are fewer stirrings. To us, it must look as though all the history of human striving is truly but a history of slaughter.

It all looks that way to us—unless we consider this one decisive thing that has indeed happened: that one has been killed, and now lives with that killing behind him.

Death cannot be evaded, but God beats it. We know, because God has indeed done it once, on Jesus.And it is—indeed—Jesus who has been raised by the Father. Not yet Peter or Paul, not yet you or me, not yet one of the great saints or gurus, but the particular person Jesus. Which is what makes the whole matter decisive for us. The particularity is a good thing. For simply that resurrection happened to someone, simply that someone had death behind and God before, might after all leave us out, might leave us staring at a great event that did not include us. It might have been that someone beat death, and so what?

It is whom God raised that makes his resurrection be an event that includes us. For he is one who did not just die, but died for someone, for us, for all of us.The specific person who is indeed risen lived a life that the New Testament can sum up as sheer love for all, love indeed unto death.

The great ancient teacher of the Western church, St. Augustine, liked to speak of “the whole Christ,” meaning Christ together with us, Christ as head of a body called the church. This Jesus refuses to go forward to the end for which he was raised, refuses to enter the Kingdom of God, without bringing us along. Indeed he cannot; he is not whole without us. As Paul once argued at length, if Christ does not carry us with him, he is not in fact raised himself.

Finally, because he is indeed risen, and because it is indeed this one and not someone else who is risen, we can believe—which is indeed, as Bultmann said, a great miracle. By ourselves we may wish that death not be the last word, but if we try to believe it, if we try to live by that vision of triumphant life, our resources fail us.

But since indeed Jesus is risen, our doubts and difficulties are finally irrelevant. He lives whether I believe it or not, and just so I can begin a little to believe it.By myself I may sort of hope that whatever future there is will be something like love and include me, but if I can depend only on my own hope, that is a frail defense against contagion of the world’s despair. But the one who is risen is the one who loved us to the death. It is indeed he who is the risen one and therefore I am included, whether I can always bring myself to believe it or not. Just so I can actually believe it. Just so we can keep our hope when all around are losing theirs.

This has been only a long appendix to the cry that is the heart of our faith. Please help me out of the appendix by joining once more in the cry itself, with a big Amen to cap it…

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 2, 2024

Where Did the Risen Jesus's Body God?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Luke tells us that on the third day after the unseemly events on Golgotha, the Risen Jesus encountered two disciples who were on their way home in Emmaus. Strangely, Cleopas and the other unnamed disciple do not recognize their traveling companion until “he took bread, blessed and broke it, and gave it to them. Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him…”

Coincident with the instant of their recognition, Luke reports, the Risen Christ “vanished from their sight.”

Note the difference:

Luke does not say Jesus walked off into the distance.

Nor does Luke write that Jesus decided to lodge outside of Emmaus before making his next Easter appearance in Capernaum by sea.

No, it’s: “He vanished from their sight.”

An odd body indeed.

Both the scriptures and the creeds are clear. The appearances of the Risen Jesus, such as on the one recorded in Luke 24, are decisive for the Resurrection claim of the primal church. The status of Jesus’s garden tomb is not so decisive. The tomb could have been empty while Jesus nevertheless could have been dead. Karl Barth and others even go so far as to suggest that the tomb could have not been empty and Jesus nevertheless could be said to be risen.

The appearances of the crucified, dead, and buried Jesus to his disciples are the occasion for Easter faith not the occupancy status of his resting place. Thus, a question presents itself that is all-important even if it is often unexamined.

What happened to Jesus’s body?The Father raised the Son’s body to where exactly?Where is the Risen Jesus in between the appearances of him?For that matter, at Eastertide’s end when the Risen Jesus ascends to sit at the Father’s right hand in heaven whither does the Son go?The Gospels make it clear. Between his Easter appearances, the Risen body of Jesus had no location in this world.

The Risen Jesus did not rent a room at the Super 8 in Jerusalem.

He was not glamping in Galilee.

He was not couch-surfing in Samaria.

Again, “he vanished from their sight.” But also the Risen Jesus was precisely not a ghost. He had wounds that neither festered nor healed, yes, yet he eats breakfast with his friends. He’s tangible in that, in the case of Thomas, he can make himself our object.

Of course, it’s true that the Resurrection is an event that could not have been photographed. The stone that’s been rolled away from the tomb testifies to an event that’s already happened not to the event itself. The Resurrection is not an event that could have had witnesses because the Resurrection is an event that happens to time as much as it’s an event that happens in time. Still, what’s straightforwardly clear from scripture is that the Resurrection was a bodily resurrection of the crucified Jesus.

To make it plain—

A body requires a place.

This locateability is exactly what distinguishes a body from a spirit.

Where is the place to which the Risen body of Jesus was raised?

Where is the place the Risen body of Jesus now resides?

April 1, 2024

God Shows Up Under the Sign of his Opposite

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Easter — Luther Memorial Church Mark 16

Here is an Easter sermon by my friend Dr. Ken Sundet Jones.

Χριστός Ανέστη!

Grace to you and peace, my friends, from God our Father and the crucified and risen Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

I have a brain that’s kind of a steel trap. My gray matter holds on to lots of useless trivia like when Elton John’s “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” was a hit. That would be ninth grade, December 1973. While I’m at it, it was track one on side two of record one of the double album of the same name. This is what my wife and son have had to put up with for over 30 years.

All this is to say that my head has a hard time shutting down. When we were members of another congregation, during the sermon I used to count the number of light fixtures or visible organ pipes. Nothing I suppose that pharmaceuticals wouldn’t solve. Here in this space lately my mind has been taken with our altarpiece. Not the painting of the woman at the well with Jesus, but the wood surrounding it.

I’ve heard that it was carved by the same artist who carved this pulpit. It’s quite a piece of woodworking. I suspect that the altar originally stood flush with it, but in the 70’s when the fashion changed it was pulled forward, so the pastor could stand behind it and didn’t face away from the congregation. Up at the top you’ll notice the cross at the highest point, the place of prominence where it should be. Around it and on the way down on either side and on top of the ministers’ chairs, and even echoed in the altar rail, are all kinds of spikes and filigree work. To my mind, all that filigree looks like briars and brambles, like the thorny patch from which Jesus’ crucifiers fetched the crafting supplies for the crown they mockingly placed on his head.

A few Sundays ago during the offering the thought struck me that we sing a hymn that talks about our altarpiece. I want to do something a little odd for Easter. I’d like you to grab a hymnal and find that hymn. It’s one every single one of you knows, but probably have never connected to this space.

Find hymn #267.

It’s “Joy to the World,” and I bet if Curtis gives us a D we can sing it acapella.

Let’s try the first verse:

Joy to the world, the Lord is come. Let earth receive its king. Let ev’ry heart prepare him room, and heav’n and nature sing…

I love being a member of a Danish congregation with a heritage of singing! Now let’s do the second verse. Pay special attention to the words.

“Nor thorns infest the ground.” We ought to think of all that filigree on the altarpiece as the thorny context that makes the cross up on top mean something.Another way of saying that is that the Resurrection, without the cross and everything that led up to it, without Jesus’ corpse, and without the darkness of a grave, is mere wonder. It’s simply a revival of a body without any of the true problems Jesus came to remedy being reckoned with.No more let sin nor sorrow grow, nor thorns infest the ground; he comes to make his blessings flow, far as the curse is found…

In Mark's gospel Jesus himself has to fight against people just wanting glorious wonders out of him. If you read Mark’s gospel (and I recommend you do — it’s the easiest and shortest gospel and has the forward movement of a thriller), you’ll encounter a strange thing: Whenever Jesus heals someone, he tells them to not broadcast it. He tells them to say nothing to anyone. Again and again, it’s “Don’t tell.”

People think he’s come to fill their hopes and dreams (and in the feeding of the 5000, their bellies, too). He’s going to fix what’s broken, whether it’s their bodies, the weather, or the political situation. He’s going to take away the bad stuff and give them mastery over their futures, so they’ll no longer feel so out-of-control. In other words, Jesus will make everything nice and comfortable or, as the Commodores once sang, “easy like Sunday morning.” No more struggle. No more aches and pains. No more sin and sorrow growing. That’s coming, to be sure — the book of Revelation is dedicated to that promise. But in Mark’s gospel, it’s not yet. First things first.

The cross and thorns first, then the glory.

Even the disciples have a problem with the way Jesus insists things be ordered. When Jesus asks them who they say that he is, Peter declares that Jesus is the Son of the Living God. So far so good.

But when Jesus starts letting his inner circle know what his identity entails — that he will suffer and die and then be raised — Peter goes ballistic, refusing to see that Jesus will do his work through the pain and agony and worldly failure of the cross. In frustration at the disciples’ unwillingness to see, Jesus has to stop them in their tracks by saying, “Get behind me, Satan!” They want the glory but not the briar patch it rises from.

People are often confused by Mark’s account of the Resurrection.Students of the Bible think Mark’s gospel ends right here with the women having been told of the Resurrection and then going away saying nothing because they were afraid. Nothing changes. The disciples are still uncommon doofuses. The world still goes on. The resurrected Jesus is still nowhere to be seen. Mic drop.

Mark’s ending is such

a sudden cliffhanger that, early on, people were uncomfortable with it and other happier endings were tacked on to it.

But if you go back to the first verse of the gospel, you’ll get a clue about what Mark is up to here. He starts with this statement: “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ the Son of God.”

He sets us up to think the story if going to be a rags-to-riches, poverty-to-power narrative, where Jesus shows up, grows up, and then goes all Bruce-Willis/John-Wick on his enemies. Wham-bam, world restored.

But Mark's tale is one where the last are first and the first are last. Blessed are the meek and the mourning. Those receiving God’s favor are not the professionally pious but the lawbreakers, the despised, the broken, the down-on-their-luck, the sinful, and the dead.

The story of Jesus is the story of God showing up among the briars, the brambles, and the thorns, among the hard stuff you’ve known in life or might be enduring right now.

There are some folks who call themselves Christian who’ve forgotten that, who’ve aligned themselves with power and prestige.They want to use politics to control other people they don’t like. Or like The Righteous Gemstones on HBOMax, they build an outwardly structure of success with a kind of prosperity gospel that in reality has a craven self-centered core.

That’s what a resurrection without a Good Friday produces: a kind of 59th Street Bridge Song faith — “Life, I love you. All is groovy.”

Paul Simon recently told Stephen Colbert he can barely sing those words anymore.

Jesus in Mark’s gospel sets us straight. It’s only after the shock of Jesus’ battered and bloody body breathing its last breath that anyone can know how radically and lovingly God operates.

God shows up under the sign of his opposite.It is in our failures and foibles, in our mourning and weeping, in our disasters and death — in those times and places where we have no ability to exert our efforts to fix anything, where God is the only power and the only hope, that we will ever let God be God.

Your thorns and brambles are the field where Jesus plants himself.All that filigree on the altarpiece— that’s you and your life. And once you’ve met Jesus at his cross and he meets you at yours, then the word is no longer, “Say nothing.”

After Jesus takes on the very worst we sinners have to sling at him, the command is finally given to the women at the tomb, “Jesus is raised from the dead. He is not here. Quickly now, go tell his disciples. It’s the first time anyone is told to tell. It’s the first command to preach.

Mark’s first verse is right. This is good news about the crucified Jesus being raised. It has to be told.But Mark tells us the women said nothing because they were afraid. Surely someone had to have told the good news of Jesus’ work on the cross being sealed by the Resurrection. Of course, someone did. But Mark leaves us with a cliffhanger, because as he said from the start, this is “the beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ the Son of God.” He means for the Jesus story to continue on in you.

The cross atop the brambles and briars isn’t just a pretty piece of carved wood whose workmanship is to be appreciated. It’s intended to be raised up amidst your thorny patches of grief, job loss, addiction, illness, aging, bad grades, broken relationships, financial problems, and parenting of toddlers.

When Jesus meets you right there, he also takes you through to his empty tomb.

That spring morning with the sunrise announcement that he is risen is also a promise for you to cling to.

God is unafraid of your sin and brokenness.That he’s raised with his wounds is a reminder he’s been through it already and says to you, “Today you will be with me in paradise.” The final divide of your own death is defeated. The curtain in the Temple is torn in two. Nothing is holding back Jesus and his power.

Resurrected and full of life, he’s rarin’ to go. He’s out to transform your briars into a wedding crown exploding with blossoms. Can you see the buds right now? Amen.

And now may the roses on our thorns which far surpass all human understanding keep our hearts and minds in Christ Jesus our crucified and risen Lord. Amen.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 31, 2024

The Gospel According to Judas

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Easter1 Corinthians 15.1-11 & John 20.1-18

The writer— my favorite writer— Cormac McCarthy published two novels last year before his death, The Passenger and its companion Stella Maris. Towards the conclusion of the former, Bobby Western, the man at the center of the story’s mystery, comes for a final visit to the psychiatric facility where, roughly a decade earlier, his sister, Alicia, a math prodigy and diagnosed schizophrenic, had received care before taking her own life.

At the facility, Bobby Western speaks with a patient named Jeffrey who was close with Alicia. During their conversation, Bobby asks Jeffrey about his sister’s delusions:

Did she ever talk to you about the little friends that used to visit her?

Sure. I asked her how come she could believe in them but she couldnt believe in Jesus.

What did she say?

She said that she’d never seen Jesus.

But you have. If I remember.

Yes.

What did he look like?

He doesnt look like something. What would he look like? There’s not something for him to look like.

Then how did you know it was Jesus?

Are you jacking with me? Do you really think that you could see Jesus and not know who the hell it was?

Did he say anything?

No. He didnt say anything.

Did you ever see him again?

No.

But you never lost faith in him.

No. The Israelite heals. That’s all you need to know. Let me quote Thomas Barefoot to you. His word is not going to come back to him void. It’s going to do what he wants it to do. You might want to think about that.

Who is Thomas Barefoot?

A convicted murderer. Waiting to be executed by the State of

Texas…

Regardless of what this exchange may mean for the characters in the novel, what Jeffrey the psychiatric patient says about Jesus is not at all different than the claim that John the Evangelist makes about Jesus in the resurrection narratives.

The Risen Jesus cannot be recognized except as he wants to be.

When the Risen Jesus does want to be recognized, he cannot not be known.

The essential attribute of an appearance of the Risen Jesus is that he is he obviously not anyone else. What makes the Risen Jesus recognizable is precisely his unlikeness.

The disciples on the road back to Emmaus from Jerusalem on Easter morning— they have no idea their traveling companion is the recently dead Jesus. Not until Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim breaks bread before their eyes are those eyes opened and the Risen Jesus recognized. The disciple named Thomas does not merely doubt the Easter news; Thomas does not recognize Jesus standing right in front of him until Jesus makes himself known to him. When the resurrected Jesus appears to the seven disciples along the Sea of Galilee, not a single one of them recognizes Jesus until Jesus commands them to cast their fishing nets starboard. Only then does Peter see, “It is the Lord!”

The Risen Jesus cannot be recognized except as he wants to be.

At the tomb, Mary mistakes Jesus for the gardener. Only by speaking her name does the Risen Jesus unveil himself to her. She’d come to his grave weeping and speaking of him merely as my Lord, “They have taken away my Lord, and I do not know where they have laid him.” Having unveiled himself to her, Mary runs from the tomb bearing witness to an identity of altogether different magnitude, “I have seen the Lord.”

When the Risen Jesus does want to be recognized, he cannot not be known.

On Easter night, the disciples are hiding behind locked doors. Despite Mary Magdalene having prepared them for the shock and awe earlier that morning, not a one of the disciples recognizes Jesus. The Risen Jesus says to them, “Peace be with you,” but still they do not know that its Jesus standing before them. Not until he reveals to them the holes in his hands and the wound in his pierced side do they recognize him— recognize him who appeared to them in a locked room, recognize him who stood amongst them without having passed through any door.

He simply appeared.

And then—

Exactly as he does on the road to Emmaus, he vanishes from their sight.

An odd body indeed.

What makes the Risen Jesus recognizable is precisely his unlikeness.

How did you know it was Jesus?

Are you jacking with me? Do you really think that you could see Jesus and not know who it was?

It was homecoming morning in Charlottesville in 1999. A month into

the fall semester of my fourth year at the University of Virginia, I’d planned

to skip the football game and was holed up at an empty carrel back in the stacks of the old Alderman library. I had a Bible on the desk for a class I was taking on the Gospel of John.

I also had a couple of LSAT prep books I’d already started to dog-ear and underline. At the library carrel on the other side of the row of bookcases was a tall, skinny, African American man wearing large headphones and an orange-and-navy track suit. He was busy highlighting a biochemistry textbook and taking notes on colored index cards. I’d started working on some sample problems from the prep book when suddenly there was a guy leaning against the end of the bookcase,

with his feet crossed nonchalantly and a crinkly, plastic-covered book in

his hands.

“What are you workin’ on?”

“Me? Um, studying for the LSAT,” I said.

“You’ve got a lot of lawyers in your family already, don’t you?”

“Yes,” I said. “Wait, how did you . . . ?”

“Don’t freak out, Jason,” he said, and pulled a different book—anthropology—from the shelf and flipped through it. “You like that other class a lot, don’t you?” he said, pointing at the Harper Collins Study Bible.

“Yeah, I really do,” I said. “But I like the other classes too. It’s hard, you know, knowing what God wants you to do with your life.”

“I just want you to enjoy your life,” he said.

I looked around for my roommates who surely must be punking me.

“Don’t do anything just to satisfy someone else’s expectations and don’t go down any path just to measure up to what the world defines as success.

That’s what I freed you from,” he said, smiling.

And then he pointed at the Bible and said, “If you’ll have the most fun doing that, then that’s what you should do.” He slid the book back in the empty space on the bookshelf.

He held out his arm to fist bump me and said, “Relax, man. You’re going to have a grand time.”

“Hold up,” I said, trying to find my voice, “I didn’t catch your name.”

But he’d already disappeared through the graffitied, heavy fire door at the end of the long row of stacks. After a few moments, I turned to the premed student on the other end of the bookcase.

Speaking up so as to be heard over his headphones, I said, “Did you catch that guy’s name?”

“What guy? Nobody been here, boss, but you and me.”

The Risen Jesus cannot be recognized except as he wants to be.

When the Risen Jesus does want to be recognized, he cannot not be known.

What makes the Risen Jesus recognizable is precisely his unlikeness.

Back in 1999—

When I was home for Christmas break, I shared the story of my encounter with my mentor, Dennis. When I finished, he took a sip of coffee from his tumbler and asked me, “What did he look like?”

I thought about it for a moment before I answered.

“I both could and could not say,” I said.

The Israelite heals. That’s all you need to know, I could’ve said to him.

And then I asked him a question, “Do you think it’s crazy that Jesus would show up in the stacks at the library?”

He laughed and replied, “I think what’s crazier are the places we know for sure that Jesus shows up.”

Then he leaned forward in his leather chair, like he was about to spill a secret in a whisper, “Word of advice. Don’t share your story with the ordination committee. They’ll send you to a therapist instead of a pulpit. It’s like they’ve not thought about what they’re claiming when they say, “Christ is risen indeed.””

What makes the Risen Jesus recognizable is precisely his unlikeness.

He is sui generis.

And of course this unlikeness should be his chief attribute. Jesus is the God-who-is-human; there is no other like him.

For instance—

Notice the detail John gives you.

First, Mary faces the tomb and addresses the angels, “They have taken away my Lord, and I do not know where they have laid him.”

Next, verse fourteen, John tells you that Mary turns.

Her back is to the tomb now.

And Mary “sees” Jesus but she doesn’t recognize him as Jesus.

Supposing him to be the gardener, she says to the man in front of her, “Sir, if you have taken him away, tell me where you have laid him, and I will take him away.”

And then— pay attention, John reports in verse sixteen that Jesus says to her, “Mary.”

And Mary turns, John says.

She turns in the direction of his voice. She turns towards the tomb so that her back is again to the man she took for the gardener. Mary’s facing the tomb when she says, “Rabboni! Teacher!”

She’s talking to the tomb.

And it’s from that same direction— from the “empty” tomb— that the voice of the Risen Christ corrects her. “Do not cling to me,” the Risen Jesus chastens her.

But again, note, John hasn’t said a word about Mary grasping anyone.

Rather, she’s facing the tomb and addressing it/him as “Teacher,” and it/he replies, “Do not cling to me.”

Which is to say, “I am not who you have known me to be. I am more than you have known me to be. I am free of even your memories of me.”

And then Mary turns again and she runs to tell the disciples and what she tells them is so mysterious, so unsettling, so incomprehensible that they turn to hide behind locked doors.

The tomb is not empty.

It’s full.

As the scripture says, the First Adam was a living being, a mortal, material body; the Second Adam, the Bible says, became a life-giving spirit. In other words, the resurrected body of Jesus Christ is a life-giving spirt.

Thus what makes the Risen Jesus recognizable is precisely this unlikeness.

Hector was an inmate at Trenton State Prison where I served as chaplain. Hector came to see me one hot summer day, his olive skin blanched white from fright. He looked both carsick and euphoric, like he’d just gotten off a rollercoaster.

“Man, no joke, Jesus Christ was just there—in my cell—last night before

lights out. He told me everything I ever done. And then he told it’s all forgiven. And then Jesus told me my kids are going to be alright. Preacher, don’t you get it? Everyone up in here is trying to get out and Jesus Christ broke in to tell me I’m forgiven.”

The Israelite heals— that’s all you need to know.

Hector looked absolutely terrified. but it didn’t stop him from asking me to baptize him the very next Sunday.

I thought about asking Hector how he knew it was Jesus.

But then I realized it would be a mistake to ask such a question. After all, the Bible tells us so. When the Risen Jesus does want to be recognized, he cannot not be known.

“Jesus broke in,” he told the congregation before I baptized him.

And I thought of Dennis telling me just a few years earlier, “I think what’s crazier are the places we know for sure that the Risen Jesus shows up.”

I think in some respects the Easter passages are so familiar to us that the staggering claims ventured by them simply slip past us. Consider, for example, the passage from the apostle Paul’s epistle to the church at Corinth. In rehearsing for them the gospel message they had first received from him— the gospel on which the church stands or falls, Paul reminds them that an item of the church’s gospel is that after Christ was raised on the third day, Jesus “appeared to the twelve.” This is both a strange claim and an unexpected appearance given the fact that, in between Christ’s resurrection and his ascension, there are only eleven apostles.

“The twelve” are no longer.

Like Jesus, Judas died on Good Friday. Judas is no longer alive come Easter. He not only handed Jesus over but by his hand he took his own life.

There are only eleven; there are not twelve.

Nevertheless, Paul reports clearly that “he appeared to the twelve.”

There is no possible way the risen Jesus could have appeared to all twelve of the apostles— at least, not on this side of the veil.

I think what’s crazier are the places we know for sure that Jesus shows up.

The Gospel of John calls Judas “the Son of Perdition.”

But 1 Peter insists that in between Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday the formerly dead but now rising Christ descended into hell in order to harrow it.

Jesus preached to the spirits imprisoned in hell.

Does that include even Judas?

If so, if not even Judas is beyond the reach of the risen Christ, then when the Old Testament proclaims that “love is as strong as death and [love’s] jealousy as fierce as the grave,” it is not speaking of love in the abstract. It’s referring concretely to Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim.

Jesus is stronger than death.

His jealous love for those whom he loves is fiercer even than the grave.

Judas is Jesus’s Eurydice.

Jesus is Orpheus for us all.

The Israelite heals… in ways way beyond our imagining.

But Judas? Even Judas?

If there is hell for anyone, certainly there is hell for the sinner who betrayed God to a cross for the cash equivalent of $216.

As the theologian Karl Barth writes:

“It may be noted that in 1 Corinthians 15 Paul does not hesitate to say that the risen Jesus appeared to the twelve even when Judas could no longer complete the number…We do not know the outcome of the dead Judas being encountered by the risen Jesus. Therefore, the church will not then preach a universal salvation. But nor will the church preach a powerless grace of Jesus Christ or a wickedness of men and women which is too powerful for it…she will preach the overwhelming power of grace and the weakness of human wickedness in face of it…for in faith in Jesus Christ, we cannot consider any as lost. We know of only one abandoned, rejected, and lost. And God raised him from the dead. He was lost then found again in order that none should be lost apart from him.”

Karl Barth made this same point teaching a university course on the Apostles’s Creed. Standing in the bombed out ruins of Bonn, Germany at the end of the second world war, Barth— who had been exiled by the Nazis— taught that the meaning of Easter is that:

“Man’s legal status as a sinner is rejected in every form. Man is no longer seriously regarded by God as a sinner. Whatever he may be, whatever he has to reproach himself with, God no longer takes him seriously as a sinner.”

Therefore—

Of course he appeared to Judas.

Judas was no longer a sinner.

Judas is only a friend loved by Jesus.

To offer absolution to someone like Judas, it is so unlike anything that any of us would do for someone like him. But precisely that unlikeness— it is a sign of the resurrection as obvious as the empty tomb.

His word is not going to come back to him void. It’s going to do what he wants it to do.”

Four years ago almost to the day, I paid a pastoral call to a 97-year-old in the neighborhood. Vince was worried that “when the virus finally gets here, I’m exactly the kind of geezer who will have a bad go of it.”

“I try to have faith,” he told me, sipping his Folgers. “but other times I don’t know. I’ve tried to be good, but I’ve not been perfect. And before I tried to be good, I was…well, I was bad."

He went on in that vein for a few minutes, somewhere between anxious and genuinely terrified by the truth that none of us is getting out of life alive.

Finally, I interrupted him.

I had heard enough.

I stood up, made the sign of the cross over him, and said, “Vince, in the name of Jesus Christ and by his authority alone, I declare unto you the entire forgiveness of all your sins.”

“You can’t do that,” he argued.

“I can do it,” I replied, “And I must do it— our Lord demands it.”

“But…but you’re just…a guy.”

“No, I’m not just a guy. The Risen Jesus has an odd body and I’m an appendage of it.

“But I haven’t told you everything,” he said, “There’s a reason I’m all alone— you don’t know all the things I’ve done. You don’t KNOW!”

“I don’t need to know all the things you’ve done to forgive you in Jesus’s name,” I replied, “I know the name of the very first sinner the Risen Jesus forgave, and whatever you’ve done, trust me, you’ve got nothing on him.”

Vince was still weeping when I left him.

He doesnt look like something. What would he look like? There’s not something for him to look like.

Actually, that’s not exactly accurate.

Jesus himself tells us that he looks precisely like you and you and you and…gathered around loaf and cup.

As mysteriously as Mary talking to an empty tomb, this is his risen body.

Once again—

The Risen Jesus cannot be recognized except as he wants to be.

And he wants to be found.

Here.

In creatures of bread and wine.

So come to the table.

Taste and see that God— for going on two thousand plus years now— no longer takes you seriously.

As a sinner.

Come to the table, the Israelite heals.

Take a chance: trust and believe.

There are crazier places we know Jesus shows up.

March 30, 2024

What Was Jesus Doing When He Was Dead?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

The theologian Chris E.W. Green jokes about how not long ago, someone asked him what he thought Jesus was doing while he was dead. “I knew what the questioner expected me to say,” Chris writes, “of course I knew the answer he wanted to hear. But the right answer is that Jesus wasn’t doing anything while he was dead. That’s what it means to say he was dead!”

“…he suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried,” the creed puts the particulars plainly.

Make no mistake, Jesus’s story ends on Good Friday.He is dead.He is every bit as dead as you will be dead one day.His death was final, conclusive, definitive—as yours will be, and mine.This is good news.While it’s certainly true that the Gospels’s passion stories are so long because Christ’s passion was primarily a problem for which the Church had to take account, it’s nevertheless the case that dying and its antecedent despair, fear, and suffering are a part of living.

Our dying is a part of our living.

Dying is an unavoidable, universal part of living.

That Christ’s passion comprises no less than a sixth of the Gospel’s narrative means, perhaps fortuitously, that Jesus displays how to negotiate that part of our living that we call dying.This is good news.As Jesus’s moments become memories, he takes the time to forgive those who have trespassed against him, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” He does not pretend that everything’s alright, “My God, my God” he cries, “Why have you forsaken me?” In so doing, the dying Jesus frees those terrified at the prospect of his death by giving voice to his own anguish. Jesus shows forth how to live the part of our living that we call dying. He provides for his family’s care in his absence, “Behold,” he says to his beloved disciple, “Here is your mother.” “And from that hour,” John reports, “the disciple took Mary to his own home.” The night before—rather than waste time trying to stay alive at any cost, Jesus took care to hand over his unfinished work to his friends, “If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet.”

Jesus exemplifies how to live the part of our living that we call dying.No, Jesus does more than exemplify the living we call dying.He transfigures it.In his letter to Cledonius, the ancient church father, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, formulates one of the most famous and critical maxims of the Christian faith,

“That which is not assumed is not healed.”

The full citation reads:

“That which is not assumed is not healed. That which is united to God, that will be saved. If half of Adam fell, also half will be taken up and healed. But if all of Adam fell, all of his nature will be united to God, and all of it will be saved.”

This is good news.

Gregory reminds us that the God-who-is-human has come to hallow the entirety of us, including our dying and death. There is no part of us, there is no part of our living, he does not assume in order to heal.

As the theologian Karl Rahner puts it,

“Jesus has accepted death. Therefore, this must be more than merely a descent into empty meaninglessness. He has accepted the state of being forsaken. Therefore, the overpowering sense of loneliness must still contain hidden within itself the promise of God’s blessed nearness. He has accepted total failure. Therefore, defeat can be a victory. He has accepted abandonment by God. Therefore, God is near even when we believe ourselves to have been abandoned by him. He has accepted all things. Therefore, all things are redeemed.”

One of my least favorite hymns sings, ““Because he lives, I can face tomorrow; because he lives, all fear is gone.” I dislike the hymn because it is closer to the true mystery of the incarnation to say that I can face tomorrow, with all its attendant fears, because he died.

That really, after all, is the charge I’ve offered at so many deathbeds.

I offer the assurance not simply that the Lord Jesus is for you.I offer the assurance that the Lord Jesus is before you.You are safe in Christ’s death, to be sure, his sins forgiven.

But even more so, you will be safe in death because Christ had entered death.

And even there, Christ had hallowed out a place where he may be found.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 29, 2024

In Jesus's Death, the Judas in Judas Died

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

John 18:1-19:42

Two or three hours after Jesus washes the feet of his disciples, Judas leads a torch-carrying posse of religious officials to the garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives where Jesus is praying.

“We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth.”

Jesus responds with a self-attestation that is as stripped down and bare as he soon will be upon the cross.

“I AM,” announces.

And immediately, John reports, Judas and the lynch mob stumble backwards and fall to the ground.

They understand.

One is not bold in an encounter with God.

Perhaps Jesus’s incredible self-assertion is the reason that Judas repents of his act almost immediately and forthwith returns the blood money.Judas does so before Jesus is even arraigned before Pilate.Jesus had said very carefully at the beginning of the Gospel that he chose Judas knowing Judas would hand him over to his enemies. This stone that Judas sets to rolling is— strangely, simultaneously— the eternal will of God.

Judas hands Jesus over to the chief priests.

The chief priests hand Jesus over to the Gentiles.

The Gentiles hand Jesus over to Pontius Pilate.

Pontius Pilate hands Jesus over to the mob.

The mob hands Jesus over to the cross.

And in every link in the chain lies the Father handing over the Son.

From all eternity, God willed to let this assault be made upon him. Nevertheless, Judas’s disobedience is certainly not obedience. Judas’s name is honorific, an homage to Israel’s last mighty military leader and messianic candidate. His other name— Iscariot— suggests that Judas belonged to the Sicarii, a sect that agitated for the violent overthrow of the empire. The Sicarii were exactly the sort to find Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim a disappointing messiah. Judas determines to hand Jesus over the Saturday before in Bethany, just after Jesus lauds Mary for lavishing upon him a prodigal amount of costly nard.

The Gospel of John concentrates its indictment upon Judas but Matthew, Mark, and Luke make clear that all of the disciples recoil when Jesus praised Mary for glorifying Jesus— specifically, glorifying him in his death.

None of them want a crucified Lord.

Thus Judas merely actualizes a sin that was a possibility for them all.

Judas is the only apostle from the tribe of Judah— as is Jesus; thus, like Jesus, Judas represents all of Israel. Just so, Judas personifies all our rejection of God. But, “betray” is not quite the right word to describe Judas’s act. All during his final week, Jesus has come in and out of the city to teach at the temple. He’s not been hard to find. He’s hardly an anonymous figure. He’s not in need of identification. The chief priests did not require a traitor to finger the suspect. With Jerusalem teeming with Passover pilgrims and tense with revolutionary fervor, the chief priests simply sought an opportunity to arrest Jesus when such an arrest would not set off an uproar.

Judas informs them of such a time and place.

He’ll be in the garden. Late tonight. After the passover. Just a few with him.

And in response the chief priests immediately weigh thirty pieces of silver. It’s an odd amount to have at the ready until you recall that it’s the exact amount the prophet Zechariah associated with the price of a bad shepherd.

A bad shepherd— hence, Judas is not precisely against Jesus. Rather Judas is not for Jesus in the way that Jesus demands of us if we are not, inadvertently, to be against him.Mary glorifying Jesus in his death—She is not exceptional.She is what Jesus expects.While Judas concluded to hand him over in Bethany, the chief priests first plot to kill Jesus after he raises Lazarus from the grave. At the soon-to-be-empty tomb, Jesus declared to the astonished onlookers, “I AM Resurrection and Life.”

And quickly Caiphas and the chief priests conclude:

“If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and the Romans will come and destroy both our holy place and our nation…It is better to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed.”

In other words, their reasoning is that of Judas.

What good is a messiah if he’s only going to get himself crucified?

And us crucified with him?

He’ll be in the garden. Late tonight. Just a few with him.

At the Fall, in the garden, God went searching for Adam, whose sin had caused him to hide in shame. “Adam, where are you?” the Lord had asked. On the eve of redemption, sinful Adam comes searching for God who is hiding in plain sight, naked and unashamed, in a homeless carpenter. “We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth,” we say.

After he walked on water, when Jesus taught in the temple and upset more than tables and cash registers, John reports that “No one was able to lay a hand on Jesus because his hour had not yet come.” But when his hour does come, when the handing over of Jesus by Judas leads these begrudgers through the darkness of night to the light of the world, Jesus voluntarily and deliberately gives himself up. The one who has preached peace does not resort to violence in order to resist them. He identifies himself.

No— he reveals himself.

“We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth.”

“I AM,” announces.

And immediately, they stumble backwards to the ground.

“I AM.”

Ego eimi.

As Fleming Rutledge writes:

”This statement cannot be construed as anything other than a deliberate appropriation by Jesus of the name given by God to Moses from the burning bush. Therefore, precisely at the moment when his passion begins, Jesus unequivocally identifies himself as nothing less than the living presence of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the creator of the universe, the Lord who is and who was and who is to come.”

Moses said to God, “Suppose I go to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ Then what shall I tell them?”

“Tell them I AM has sent you,” God says to Moses from the burning bush.

“We’ve been sent for Jesus of Nazareth,” we say.

“I AM,” says God.

Martin Luther compressed the mystery of this self-assertion by Jesus with the Latin phrase Finitum capax infiniti, “The finite is capable of containing the infinite.” The glory of God is camouflaged by humility and suffering, Luther said, for our God likes to hide himself beneath his opposite.

Of course this mystery also produces the absurdity of the Passion; that is, Judas et al are against the very God who is for them in Jesus Christ.

Then again, this mystery that produces the absurdity of Good Friday also begets the offense of the gospel; namely, Judas is the first of the sinners to save for whom Christ came in to the world.

Just the other day I typed into Google’s search engine the incomplete sentence, “God is…” and even before I was done typing Google autofilled the most common choices.

God is love.

God is good.

God is dead.

And then the next three:

God is in control.

God is just.

God is gracious

Good Friday is the only moment in time where all of those sentences are true statements.But when I scrolled even further down the list of the most popular searches for the definition and identity of God not one of them said, “God is a crucified Jew who lived briefly, died violently, and rose unexpectedly.”

Ironically, our search history proves that Jesus did not die alone. Judas too suffered death in place of others exactly to the extent that, like Judas, neither do we much want a crucified God.As the Apostle Paul notes at the opening of his letter to the Romans, fallen humanity is fallen precisely in that we don’t want to know about the real God and his will. But on Good Friday we are without excuse. We know the real God, and he has told us more about his will for our lives than any of us are willing to obey, for the one who bears our sins in his body on the tree began his journey there by saying, “I AM.”

“We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth.”

“I AM.”

True God from true God.

Begotten not made.

Of one being with the Father.

Nearly every account of something Jesus says or does in John’s Gospel ends with someone believing in Jesus. Believing not in the signs he performed or in the truths he spoke but purely and simply in him. When Jesus transforms water into almost two hundred gallons of top-shelf wine, the wedding at Cana doesn’t end with the partygoers exclaiming “Wow!” or looking forward to free Chardonnay forever. No, John says the disciples saw and believed in Jesus himself who is “the best wine kept until now.” When the man born blind sees Jesus for the first time, he says, “I believe.” Indeed John’s Gospel ends with Thomas testifying, “My Lord and my God.”

The only instance where Jesus says or does something in John’s Gospel that does not end with someone believing in Jesus is when Judas hands Jesus over to the chief priests’s posse. After stumbling backwards and falling to the ground, Judas runs away. He returns the thirty pieces of silver to the ones who bought him. And then he enters a passion of his own in a place the priests later named Akeldama, Field of Blood [Money].

Where Jesus gives up his life upon a tree, Judas takes his life upon a tree.

Where Jesus surrenders his life believing the Father will vindicate him, Judas forsakes his life upon a tree believing there was no longer any hope for him.

Where Judas usurps the role of Judge over his life, Jesus submits to being the Judge judged in our place.

Nevertheless, Karl Barth writes, Judas, though he may not fathom it, “is still an elect and called apostle of Jesus the Christ.” If Jesus comes to save the lost— and there is no one in the Gospel stories who is more lost than the one who betrays God for the modern day equivalent of $216— then surely the saving grace of God would include even Judas! If the shepherd goes to any length to save the single lost sheep, if the widow lights a lamp in the middle of the night to find a lost coin, and if a father joyfully celebrates the return of the prodigal, then surely, Barth insists, Judas is not out of reach for the One who has come to save us all.

According to Barth, after Christ himself, Judas is the most important character in the New Testament because Judas is the executor of the New Testament.He is the executor in that he wills what God wills to be done.

As Barth writes:

“The paradox in the figure of Judas is that, although his actions as the executor of the New Testament is so absolutely sinful, yet as such, in all its sinfulness, it is still the action of that executor. The divine and human handing over cannot be distinguished in what Judas did…in the case of Judas, sin is made righteousness and evil good…Was it not Judas, the sinner without equal, who offered himself at the decisive moment to carry out the will of God, not in spite of his unparalleled sin, but in it? There is nothing here to venerate, nor is there anything to despise. There is place only for the recognition and adoration and magnifying of God.”

In fact, Judas on his tree, utterly lost and without merit of any kind, becomes an icon of the merciful depths of the crucified love on Calvary’s tree. The love that is God is crucified love even— especially— for him.

And if for him, for you.

Ultimately, in handing Jesus over, this is what Judas took upon his conscience— to bring Jesus into the situation where apart from the Father no one can help Jesus. In handing Jesus over, Judas perverts his office as an apostle into its exact opposite. Rather than bringing sinners under the power of Jesus, he’s delivered Jesus into the hands of sinners.

Nevertheless!

As Barth writes:

“It is a serious matter to be a Pharaoh, a Saul, a Judas…a sinner…but whatever judgment God may inflict on Judas, God certainly does not inflict on Judas what God inflicted upon himself by handing over Jesus Christ.”

“We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth.”

“I AM,” Jesus replies.

“So the soldiers, their officer, and the Jewish police arrested Jesus and bound him,” John concludes, “…and they handed him over to Caiaphas, the high priest that year, who was the one that had advised the Jews that it was better to have one man die than for all to die.” Only Easter can reveal the irony: Caiaphas is correct. “Because the one man died for all,” Paul writes long before John writes his Gospel, “all have died.”

The divine and human handing over cannot be distinguished.Therefore—In Jesus’s death, the Judas in Judas dies.In Jesus’s death, the Peter in Peter dies.

In Christ’s death, the Judas in you dies.

In Jesus’s death, the Peter and the Pilate in you die too.

Because by water and the word, YOU ARE in him who says, “I AM.”

The promise alone should make you shudder and stumble backwards.

For the news itself of Christ and him crucified is an encounter with the One who will raise him the dead.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Good Friday Forever Settles God's Identity

Hi Friends,

I am humbled by messages like the one I recently received:

Steve’s exhibit A. Getting the gospel right and getting the gospel out is a matter of death and life. Help do both:

Jason, I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your ministry. You’ve made such a difference in my life. Eight years ago (so, 2016) I was one of the Bible teachers at my church and being prepared to be a pastor. Like you, I believe that we have to “give them the goods” every time. And I so did. Then, something happened. I found myself swimming against a rising tide of more vocal political opinions and science denial. I left my church, disillusioned. I became less certain, I began to question, and eventually I began to deconstruct. And soon, I was going too far. Then the Lord led me to you. Finding you really was providential. You are so correct when you say that nobody drifts toward the gospel. All of a sudden, it was me who needed to be given the goods. Thankfully, you did. It’s not an exaggeration to say that the Lord used you to save my faith. So - again - thank you.

— Steve

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber.

Mark 15.21:

“They compelled a passer-by, who was coming in from the country, to carry his cross; it was Simon of Cyrene, the father of Alexander and Rufus.”

Simon is how most people participate in injustice.

We’re just bystanders and passersby until, like a wave crashing over us, evil’s undertow pulls us into it.

Simon must be on pilgrimage to Jerusalem to celebrate the Passover. Cyrene is a colony in Libya. Simon has come a long way only to find himself pulled from the crowd and compelled to carry the instrument of torture and death by which the best and brightest of Church and State, along with their enabling mob, will murder God. It’s tempting to imagine Simon’s act captured on video and streamed onto social media. If Good Friday took place in the twenty-first century instead of the first, how many observers would cancel Simon of Cyrene, dox him, or charge him as complicit in the miscarriage of justice?

Mark characterizes Simon as a passerby, which could mean either he is an onlooker in the crowd, intrigued or intimidated by the ghastly spectacle or it could mean he’s like those in Jesus’s parable who passed by the man in the ditch, too busy to be bothered by the brutality in the street.

Did Simon join the crowd when they shouted, “Crucify him!”We do not know.We do know Simon did not shout, “Do not crucify him!”No one so shouted, “Do not crucify him!”Likewise, not everyone betrayed Jesus for pieces of silver but no one attempted to buy his release.

Mark does not report that Christ needed someone to carry his cross:

“They began saluting him, ‘Hail, King of the Jews!’ They struck his head with a reed, spat upon him, and knelt down in homage to him. After mocking him, they stripped him of the purple cloak and put his own clothes on him. Then they led him out to crucify him. They compelled a passer-by, who was coming in from the country, to carry his cross; it was Simon of Cyrene, the father of Alexander and Rufus.”

Mark does not say that the Lord Jesus needed Simon to carry his cross.

Earlier in the week, on Palm Sunday, Jesus did not need the disciples to lift him and place him on the donkey— it was only a foal; he could swing his leg over it. Nevertheless, Jesus humbly submitted to them and allowed them to lift him onto the ass. At the beginning of his ministry, Jesus did not need to be baptized with John’s baptism. He had no sins to repent. Nevertheless, Jesus humbly submitted to John and allowed him to wash away his sins. There is no indication in Mark’s Gospel that the Lord Jesus needs Simon’s help; nevertheless, Jesus humbly submits and makes a place for this passerby in his passion. As Cyril of Alexandria says, the wonder is that Jesus, the Beloved, not only shares with us what is his, but also includes us in who he is.

In this detail, Simon helping Jesus, the Gospel wants you to see not the uniqueness or honor of Simon but the constancy and steadfastness of Jesus.

Even now, Jesus is who Jesus has always been. He humbly submits and accommodates Simon though he needs him not. The Gospel wants you to see not the distinctiveness of Simon’s character—we don’t know anything about him. The Gospel wants you to see instead the consistency of Christ’s identity, the Man for Others, always.

As many in my parish know, Gary Sherfey’s last words to his wife were, “I love you.” For that matter, Gary’s last words to me also were, “I love you.” To those who know Gary, such a benediction sums up his life perfectly. Conversely, if Gary had left this life striking a discordant note (“I hate you. Get out of here. Shut the hell up!”) it would have unsettled the entire story by which we know and name Gary.

Before we glean any other meaning from Good Friday, we can and must say this much:Christ’s death forever settles his identity.What the tradition labels “atonement theories,” explanations for how Christ reconciles us to God, nearly all suffer the same fatal defect; namely, they do not start straightforwardly from the Gospel narratives. The Gospel of Mark, for example, permits us to draw no other conclusion from the crucifixion other than the fact that Jesus’s death brings an end to Jesus’s life. Therefore, Mark’s Gospel allows us to assert at least this premise: Christ’s death permanently settles his identity.

Until the story comes to an end, it is not settled whose story will have been written. What if George Washington had betrayed his country in his old age? What if Abraham Lincoln had gone home after the play only to bungle Reconstruction? What if Jesus had said no to Pilate’s question, “Are you the King of the Jews?” What if Christ had heeded the crowd and come down off his cross?

That the Man for Others died rather than seek his own kingdom settles that he is the Man for Others, always.The Lord Jesus can never now be other than who he was.Correlatively, this means you can never now be otherwise. You are right now and you always will be one the Man for Others is for.

Straightforwardly, Christ’s death brings an end to Christ’s life.

In so doing, Jesus’s death settles Jesus’s identity.

From this simple premise, Martin Luther constructed an equally simple theory of the atonement.

Jesus died, Luther argues in the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, in order to transform all his promises into a testament.

Of course the distinguishing feature of a last will and testament is that it becomes binding and irrevocable exactly because the promise-maker has died. By settling his identity once and for all, Jesus’s death removes Jesus’s promises from any possibility of retraction or qualification. His unconditional promises cannot be undone. Because he died, the Risen Jesus has no choice but to execute the promises of Mary’s son.

This is the basis and authority on which I can declare the entire forgiveness of your sins because the identity of the Lord is a settled matter. This is the basis on which we must pray today for the likes of Caiphas and Judas and Pontius Pilate and Simon of Cyrene (assuming his motives were as mixed as ours always are).

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 28, 2024

Do Not Keep Me Near the Cross

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Holy Thursday — Exodus 12.1-14

On the night he’s handed over, as the host of his last Passover, Jesus doesn’t just change the script (“This is my body” rather than “This is the body of the passover”) Jesus adds to it. According to the Haggadah, after they feast on the meal, Jesus is supposed to pour and bless the third cup of wine, and invite the disciples to drink it. Then, according to the script, they’re supposed to sing from the Book of Psalms before blessing and drinking the fourth cup of wine. Except, after they feast on the meal, when the time comes, Jesus takes the third cup of wine, the cup symbolizing God’s redemption promise (“I will deliver you from captivity”) and Jesus says, “This is my blood…drink from this all of you…”

Hang on— drink what?

What’s blood doing on our table?

They’d be better off going back to eating and drinking with hookers and thieves. Blood shouldn’t be anywhere near their table. The law stipulated that "anyone of the house of Israel who eats any blood, I the Lord will set my face against that person who consumes blood, and will forsake that person as accursed…”

Blood is forbidden.

Anyone who consumes it in any way is accursed. That’s why verse nine in Exodus 12 commands Israel to roast the Passover lamb over a fire not boil it or consume it raw. None of the blood of the lamb can end up on the table. And this isn’t an arbitrary law designed to bless the world with Jewish delis and kosher hot dogs.

Blood was forbidden because blood symbolized life.

As such, the blood belonged to the Giver of Life alone. Blood can’t be on your menu because it’s not yours to serve. And because God is the giver of life to every creature the blood of every creature, in fact, represents God’s own life. But now, Jesus is once again breaking the law of the covenant by inviting them to drink it, “Drink from this all of you. This is my blood of the new covenant poured out for you and for many for deliverance from sins.”

According to the law, the blood on the table makes him forsaken.

Which is to say, to obey him and drink his blood is to disobey the law in league with him and thus to share in his forsakenness. To obey him is to share in the curse he will bear. To be crucified with him. He’s offering them what belongs to God alone. He’s offering them his life. Which is to say, he’s offering them his death. He’s offering them a share in his death.

“This is my blood of the new covenant poured out for you and for many for the deliverance from sins.”

Not only should the blood of the lamb not be in the third cup or even on the Passover table at all, what’s left of the lamb’s blood Jesus should’ve smeared across the door to the upper room. The blood-smeared door will a sign, God promises; so that, when God’s angel of Death passes over, God’s people will be spared the wages of Pharaoh’s sin.

The blood— it will be a sign, God promises.But hold up— God doesn’t need a sign!The Almighty from whom no secret is hid does not need an SOS streaked in neon blood. In all of Midian, God managed to find Moses and meet him in a burning bush. God doesn’t need a sign like the Bat Signal to find his People.

No.

From God’s side, the blood is superfluous.

From God’s side, the blood is absolutely unnecessary.

God doesn’t need a sign. We do.We need something tangible and visible in which to place our faith.

We need something outside of ourselves to believe.

In his book The Preached God, the theologian Gerhard Forde recalls a seminary student for whom he served as an advisor. Returning to campus from the summer hiatus, the seminarian told her professor how during the course of her internship she had engaged the film-maker Woody Allen in a number of extensive and interesting conversations. Apparently the congregation where the seminarian had served during the summer owned the house next to the church, and Woody Allen had leased the house as the set for his forthcoming movie.

Having befriended the director, their conversations soon got around to theology. The seminarian shared her surprise with her professor that she had discovered that Allen was a fairly astute student of theology. He even recommended books to her, authors and biblical commentaries.

One day the film-maker said to the seminarian, “You know, I would like to believe in God. I would like to encounter God. But I don’t have the gift of faith.”

The professor listened to his student’s story and quickly interrupted her, “Aha! You hooked him! What did you say then?”

The student confessed her failure honestly, “I didn’t know what to say. He knew as much theology as I did. How was I going to convince him of God? Get him to faith? What was I supposed to say?”

After thinking about it, the professor replied to her:

“Well, suppose you could have said something like this: ‘Is this for real and not just idle chit-chat? Is this a confession? You would like to believe in God— be encountered by him— but you don’t have the gift of faith? Well, hang on to your socks because I am about to give both God and faith to you in one fell swoop!’

And then you put your hand on his head and say, ‘I declare unto you the gracious forgiveness of all your sins in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. There! Now I gave it to you, God and faith in him! Just as sure as you sensed my extended hand they are both now yours. Repent and believe it. And if you ever wonder about it or forget it, come back and I’ll do it again. Better yet, come to church. God shows up every Sunday and hands over faith in edible form. I can even wash you in God.’”

As the Large Catechism puts it, faith must have something concrete to believe, something to which it may cling and upon which it can stand. This is why Martin Luther insisted that the sacraments and faith should never be separated. Your faith must have something external to you to grab onto and cling to for life. Otherwise, faith turns inward and you're left attempting to have faith in your faith.

No one's faith is so strong.

Indeed for the first Protestants the phrase “by faith alone” could just as easily be substituted as “by bread and wine alone” or “by loaf and cup alone” or “by water and the word alone” because it's on sacramental faith that we stand.

What is sacramental faith?

Sacramental faith is the conviction that the gospel is not a once upon a time story about an event that happened in a Galilee far, far away.

Rather sacramental faith is the conviction that the living God acts in the here and now to reclaim the lost, that he comes to us extra nos, from outside of us, an alien word attached to creatures like water, wine, and bread.

In several places, the New Testament Book of Hebrews proclaims that Jesus is our great high priest, “a priest according to the order of Melchizedek.” Just after the flood, in the Book of Genesis, when he is still in the infancy of his election, Abram encounters a figure named Melchizedek, who is both a king and a priest. Melchizedek goes out to meet Abram. And Melchizedek takes with him bread and wine. In the name of the Most High God, Melchizedek blesses the bread and the wine, and he gives it to Abram, saying, “bless be Abram by God Most High, maker of heaven and earth, and blessed be God Most High.”

And there in the valley with the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah behind him, Abram takes the bread and the wine. And he eats the bread and he drinks the wine. And he tastes and sees the promise of the blessing of the Most High God. He grabs hold of it in his hands. And here and now.

Christ Jesus is a priest like Melchizedek, says the book of Hebrews.

Like Melchizedek, Christ comes down and meets us in the valley of the shadow of death, and Christ gives us wine and bread to which we can cling. Like Melchizedek, Christ gives us tangible, visible means which we can grab ahold of and know, in the here and now that, as Gerhard Forde says, “the one who runs the whole show is for you.” Without these external things, faith has nothing to believe but some incomprehensible promise about the distant future or some ancient history that happened over two thousand years ago.

We require more.

We need signs.

Faith can only be faith when it has a concrete promise to believe.After all, even the demons and the pagans believe in the history of Jesus. What the demons and the pagans do not believe is that that history of Jesus is for them. Faith then is not about you believing in God. Faith is not about you believing that two thousand years ago Jesus died for you. It's not even about you believing that three days later God raised him from the dead for your justification.

As Martin Luther proclaimed:

“If I now seek the forgiveness of sins, I do not run to the cross, for I will not find the forgiveness of my sins at the cross, but I will find it in the sacrament. I will find it in the gospel word which distributes, presents, offers, and gives to me today that forgiveness which was won on the cross.”

Thus, Holy Thursday is the day when we recall that faith is an everyday encounter. Faith is an ongoing, living, present-tense, laying hold of the promise that God makes to you in the here and now. Faith is holding out your hands to receive the bread and the wine through which God promises to you— tonight— “the body and blood of my Son given for you.” In other words, the Living God uses bread and wine to promise to you, in the present, that he loves you to the grave and back.

Grace is not cheap. It’s not even expensive.It's free.And it's precisely the freeness of the gift that destroys the self that so wishes to stay in control.

In precisely this way, the sacrament sanctifies.

It turns you out of yourself. It turns you inside out. It breaks the self's incurable addiction to itself.

And by doing so, it reverses the very first sin our parents made in paradise.

Therein lies the good news in God giving us the loaf and cup.As a Christian, you don't need to believe a thousand different things about God. You don't need to believe in a future you scarcely can imagine. You don't even need to believe in a two thousand year old history.You only need to cling to these promises made concrete in bread and wine and water.

“I’ll wash you in him— you could have said something like that,” Professor Forde said to his seminarian about her conversations with the filmmaker.

“But oh,” the student said, “that would take a lot of guts.”

To which her professor replied:

“Of course it takes guts, but in the church we call it the Holy Spirit! Why not, after all, take some chances, give it your best shot? Perhaps the man does not need any more explanations. He has heard them all.

It is the dirtiest trick in the theological arsenal to be everlastingly explaining that justification, faith, and grace are free gifts, but never getting around to giving them: never, that is, moving from explanation to proclamation, never taking the risk of actually handing over the goods!

When faced with doubt — “I don’t have the gift of faith” — shall we explain about God, his love, about how it is a free gift? All that is pure schwärmerei. It leaves the poor man on his own to make peace with an explanation.

When faced with doubt — “I don’t have the gift of faith” — do not explain about God. Speak for God. Give God.”

In John’s Gospel, on the night he’s handed over, Jesus gets up from the supper table, he sets aside his robe, and puts on an apron. Then he pours water into a basin, stoops over onto his knees and one-by-one he begins to wash his friends’s dirty feet.

When he gets to Peter, Peter starts arguing, “You're not going to wash my feet-ever!”

And Jesus says, “Unless I wash you, you can't be part of me or my kingdom.”

And Peter replies, “Not only my feet, then. Wash my hands! Wash my head! Wash all of me.”

We forget how the rest of that story goes.

We forget how Jesus promises to Peter and his disciples, “Now, I need only to wash your feet; soon I will make the rest of you clean forever.”

I’ll make the rest of you forever clean.

I’ll make the rest of you forever clean.