Jason Micheli's Blog, page 49

March 7, 2024

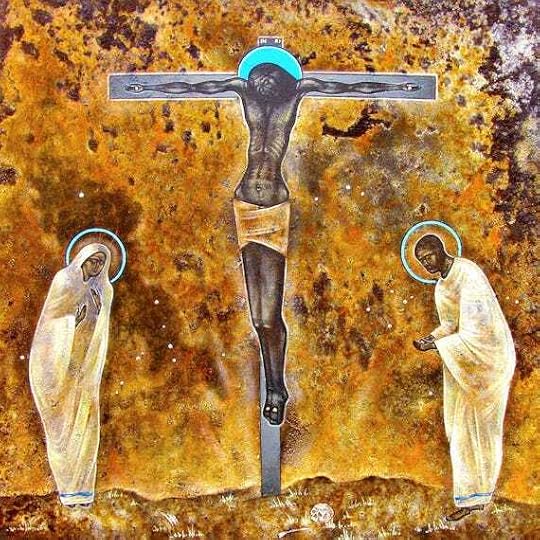

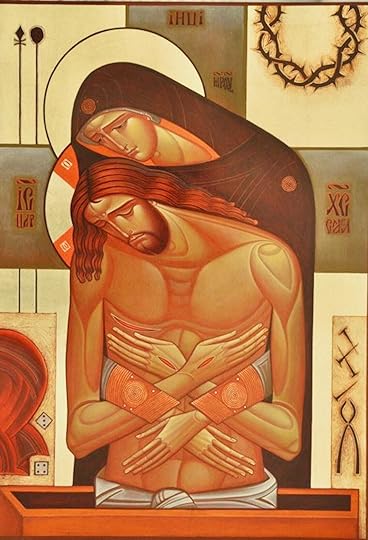

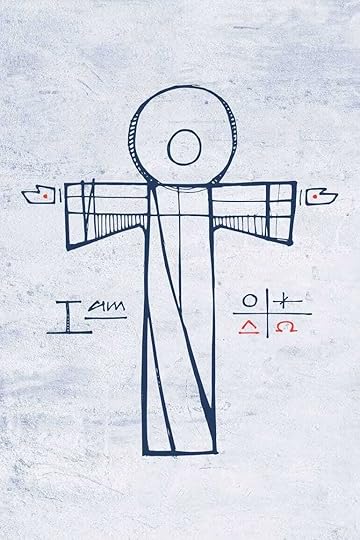

Squeamish about the Bible’s Blood Speak?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Nearly a decade ago, Hannah Graham, a UVA student from my parish, went missing near her campus. Weeks later her body was found. She’d been assaulted and brutally murdered.

Theologically, I’ve always been committed to the sheer nothingness of evil. Rather than a thing with any substance or subsistence of its own, the tradition holds that evil is absence. Maybe evil is the privation of the good, as Augustine thought it, but during the prayer service I led in the days when Hannah was still missing, when everyone hoped for the best but suspected the worst, the presence of sin and evil was felt palpably throughout the sanctuary. In the months after then the devastation and trauma felt from her murder grew and festered. I watched with sadness and something like righteous anger as many of Hannah’s friends in my congregation struggled with depression, despair, and a loss of faith. When it was reported that Jesse Matthew, her accused murderer, had decided to plead guilty, I rejoiced confident that God rejoiced too now that Hannah would receive at least this measure of justice.

My takeaway from this experience:A vital refrain of scripture gets obscured when we individualize and moralize sin.Sin costs something.Sin must be atoned for.Yes, Jesus enjoins us to forgive as much as 70 x 7 times, but sin, like the sin done to Hannah and the entire community who loved her, requires justice too. As my mother used to tell me, “Saying sorry doesn’t cut it. You’ve got to repair the damage you’ve done.” Even for my mom, repair required sacrifice.

Sin costs something.

This is the convicting acknowledgment running through the rituals of sacrifice in the Book of Leviticus. Counter to the popular complaint about traditional atonement theories which asks, flippantly, “Why can’t God just forgive?” the fundamental presupposition of Leviticus is that there must be atonement for sin. Put aside distracting conceits like God’s offended honor and simply focus on the concrete, real-world devastation wrought by sin.

As Fleming Rutledge argues in her book, The Crucifixion:

“Sin can’t just be forgiven and then set aside as though nothing has happened. If someone commits a terrible wrong, Christians know that we are to forgive; but something in us nevertheless cries out for justice. The Old and New Testaments both speak profoundly to this problem. It is not enough to say, ‘Mistakes were made, or ‘I didn’t mean to’ ; the whole system in Leviticus is set up to prevent anyone from thinking that unwitting sin doesn’t count.”

In Part 2 of The Crucifixion, Fleming Rutledge examines at length the primary atonement motifs (her preferred term over atonement theories) in the biblical narrative. She gives considerable attention to the motif of blood sacrifice, seeing it not only as the foundational motif upon which many other atonement motifs depend but also because blood sacrifice, along with passover, is the primary lens through which the early Christians interpreted the death of Jesus. They did so, after all, because ‘their single source for discovering the meaning of the strange death of their Lord was the scriptures they had always known.’

They grappled with the meaning of Christ’s death in the terms available to them, in other words, and in their scriptures blood sacrifice was a recurring motif for understanding how sinful humanity is brought near to their God. In particular, the Book of Leviticus became fertile ground for interpreting the terrible mystery of the cross.

As Rutledge imagines:

“It must have been a very exciting process. Anyone reading Leviticus and thinking of Jesus at the same time could hardly fail to notice a phrase like ‘a male without blemish’ in the list of stipulations. This is the sort of detail that would would jump off the page of the Hebrew Scriptures in those first years after the resurrection.”

Mainline and progressive Christians frequently express disdain for the blood imagery of scripture. We judge it, snobbishly Rutledge thinks, to be primitive; meanwhile, we let our kids play violent games and we fill theaters for violent films. We exult in gore and violence in our entertainments, but we feign that we’re too fastidious to exalt God by singing “There’s a Fountain Filled with Blood.” Rare is the Christmas preacher bold enough take the Slaughter of the Innocents as his text while the Washington Post app on my iPhone makes it uncomfortably obvious that the slaughter of innocents goes on every day. Never mind that in its use of blood imagery, scripture remains reticent, refusing to dwell in gore by focusing instead on the effects of the sacrificed blood.

In our disinclination towards the language of blood and sacrifice, treating it as a detachable option in atonement theology, Christians today could not be more different from the writers of the Old Testament who held that humanity is distant from God in its sin and atonement is possible only by way of blood.

Viewed from the perspective of the Hebrew Scriptures, we make the very error Anselm cautions against in Cur Deus Homo. We’ve not truly considered the weight of sin.My friend, Tony Jones, once featured a guest post on his blog from someone who advocated altering the traditional serving words for the eucharist (The body of Christ broken for you. The blood of Christ shed for you.) to “Christ is here, in your brokenness. Christ is here, bringing you to life.” Or, “Christ broken, with us in our brokenness. Christ’s life, flowing through our lives.” Such redactions just won’t do the heavy lifting if one is committed to taking seriously the language of scripture. While the traditional imagery of blood sacrifice may make some squeamish, Fleming Rutledge insists it is:

Editing out blood sacrifice commits the very act it’s intended to avoid, violence.It commits violence agains the text of scripture by eviscerating the language of the Bible.Scripture speaks of the blood of Christ three times more often than it speaks of the death of Christ.“Central to the story of salvation through Jesus Christ, and without this theme the Christian proclamation loses much of its power, becoming both theologically and ethically undernourished.”

Such a statistic alone reveals the extent to which blood sacrifice is a dominant theme in extrapolating the meaning of Christ’s death.

March 6, 2024

Unpacking the Bible Belt Baggage of "You Must be Born Again"

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

The lectionary Gospel passage for the Fourth Sunday of Lent is John 3.14-21:

“And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life. Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him. Those who believe in him are not condemned; but those who do not believe are condemned already, because they have not believed in the name of the only Son of God. And this is the judgment, that the light has come into the world, and people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil. For all who do evil hate the light and do not come to the light, so that their deeds may not be exposed.

But those who do what is true come to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that their deeds have been done in God."

Question:

Is eternal life contingent upon my decision to believe?

Do you need, as Jesus says earlier in the passage, to be born again to be saved?

Earlier in the chapter, Nicodemus says to Jesus, “I’ve seen the signs you do. Tell me, who are you?”

And oddly, Jesus answers in verse 5 of this chapter with that verse which tightens the sphincter of every good, liberal Protestant:

“Very truly I tell you, no one can see the Kingdom of God without being born again.”

Apparently, Nicodemus knows what he doesn’t know. Nicodemus must suspect his faith is somehow inadequate and lacking; otherwise, Nicodemus— a Pharisee, a member of the Sanhedrin even— would not take the great risk of coming to Jesus under the cover of darkness. Sure, it’s only chapter three, but here in John’s Gospel Jesus has just thrown his temple tantrum and already he’s made himself public enemy number one. But Jesus, in typical Jesus fashion, doesn’t do anything at all to mitigate whatever spiritual crisis has led Nicodemus to Jesus. He doesn’t bother to comfort Nicodemus or reassure Nicodemus or do anything to relieve whatever religious tension has brought Nicodemus to Jesus.

“Oh, you’re one of those seekers, are you, Nicodemus? Well, try this on for size: “No one can see the Kingdom of God without being born again.”

Notice how Jesus tightens the screws on whatever worry has prompted Nicodemus to seek out this marked Messiah.

Jesus doesn’t do what United Methodist pastors are trained to do. Jesus doesn’t let Nicodemus off the hook with some bland assurance like, “It’s okay. Don’t worry, Nicodemus, be happy. God loves you.”

Jesus doesn’t offer Nicodemus a non-anxious presence and say, “Your faith is fine just as it is, Nicodemus. We’re all on a journey. There are many paths to my Father.”

No, Jesus sticks his thumb in whatever existential wound Nicodemus is nursing and raises the stakes absolutely, “If you want to see the Kingdom of God, Nicodemus, you must be born again.”

Oh, and FYI, he’s not just talking to Nicodemus.

Jesus dials it up to DEFCON ETERNAL for all of us because that “you” in “You must be born again” is plural.We are swept up in that you.It’s, “You all must be born again if you want to see the Kingdom of God.”

No exceptions.

No loopholes for raking your neighbor’s yard or never missing a Sunday service.

That you— it’s all of us.“You all must be born again.”

And Nicodemus, he’s a Pharisee. He’s super religious so he responds— like we religious types always respond— with what he’s supposed to do.

“How do I do that, Jesus? Crawl back up into my mother’s womb?”

To which Jesus says, “Ewww.” (John doesn’t mention it, but I’m sure Jesus said it.)

And then Jesus says:

“Very truly, I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and Spirit. What is born of the flesh is flesh, and what is born of the Spirit is spirit. Do not be astonished that I said to you, “You all must be born again.”

Pay attention to the verbs Jesus uses on Nicodemus— on us— in verses three and five.

The verbs are what makes this passage good news for everybody.

March 5, 2024

Father Abraham was an Immigrant

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

In this conversation, Rabbi Joseph Etelhite discusses the story of Abraham and its significance in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He explores the themes of infertility, surrogacy, blended families, and the ethical complexities of Abraham's actions. Rabbi Etelhite emphasizes the importance of engagement, empathy, and the rejection of indifference in relationships. He also highlights the role of Abraham as an immigrant and the challenges faced by those seeking a new place to live. The conversation concludes with a discussion on Rachel and the importance of pluralism in religious faiths. This conversation explores the tension of identity, the exclusive claims of religion, the challenge of pluralism, and the limitations of human language. It delves into the changing nature of God, the power of pluralism, and the increase in antisemitism. The legacy of Rachel is examined, highlighting the importance of narrative. The conversation also addresses the interpretation of scripture and how to address transphobia. It concludes by emphasizing the need to balance personal experience with communal interpretation and move beyond oppositional discourse.

Takeaways

Abraham's story is significant in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, as he is considered the first patriarch and an example of monotheistic faith.

Infertility is a common issue in the Hebrew Bible, and surrogacy is explored through the story of Hagar and Ishmael.

Abraham's story highlights the challenges and complexities of blended families and the importance of empathy and engagement in relationships.

The story of Sodom and Gomorrah is often misunderstood, with the focus being on sexual perversity rather than social indifference and cruelty.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 4, 2024

God’s Grace in Christ isn’t Cheap

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

The lectionary epistle for this coming Fourth Sunday of Lent is Ephesians 2.1-10, a passage so powerful and important it bears quoting:

“You were dead through the trespasses and sins in which you once lived, following the course of this world, following the ruler of the power of the air, the spirit that is now at work among those who are disobedient. All of us once lived among them in the passions of our flesh, following the desires of flesh and senses, and we were by nature children of wrath, like everyone else. But God, who is rich in mercy, out of the great love with which he loved us even when we were dead through our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ--by grace you have been saved--

and raised us up with him and seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus, so that in the ages to come he might show the immeasurable riches of his grace in kindness toward us in Christ Jesus. For by grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God-- not the result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are what he has made us, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand to be our way of life.”

Preachers barely need to preach this Sunday.

As we make our way to the cross this Lent, it’s worth noting that, according to the apostle Paul, we need it— the cross.That is, our condition before Almighty God is both more helpless and more hopeless than our requiring a co-pilot. We don’t need help. That’s Americianity. That’s not Christianity. That’s not the gospel. According to the apostolic message, we don’t need help; we need an embalmer. We don’t need an instructor; we need an undertaker. Or we need someone who can raise the dead.

The Gospel is not that Jesus will do the rest if or after you’ve done your best. No, that’s an ancient heresy called Pelagianism, and, while it might be the most popular religion in America, it is not the gospel.

You do your best and Christ will do the rest.

No.

“You were dead through the trespasses and sins.”

A corpse can’t cooperate with God. A stiff can’t set out to improve itself. With rigor mortis, you can’t even repent. Apart from the unmerited, uninitiated, one-way work of Jesus Christ for you upon you— applied to you at your baptism— you are dead in your sins. The gospel begins not with you behind the wheel of life and God as your co-pilot. The gospel begins with you dead in the grave. Jesus doesn’t help us steer our lives. Jesus takes our sin-dead corpses out of the trunk of the car, and he makes us alive again. That’s the gospel.

He makes us alive for him. He makes us alive for good works, Paul says. But notice, Christ does not make us alive for good works that we self-select. Christ makes us alive for good works he has chosen from beforehand.

We do not pursue good works for God.God places us into good works for himself. So that, from beginning to end, the gospel is not about what we do but about what God has done and is doing.

March 3, 2024

Your Future is Christ’s to Give One Another

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

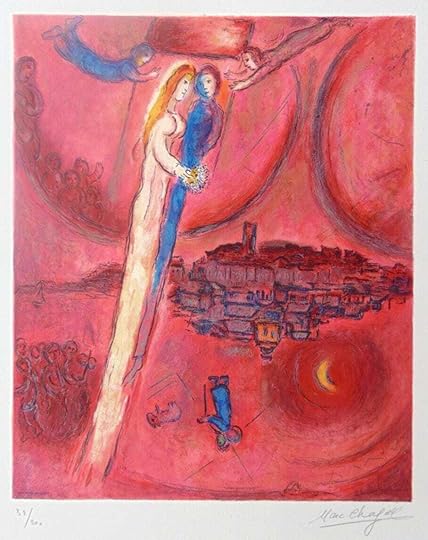

I’m down in St. Augustine, Florida to celebrate the wedding of Andrew and Gina. Here’s my homily for the passages they selected.

Romans 12.9-16, 1 Corinthians 13.1-13

No doubt we all would like a partner who is patient and kind and humble, as slow to anger as he is shy to boast— I know my wife wishes she enjoyed such a spouse. Despite my best efforts, however, she has yet to discover such a husband. Just so, I have no advice to give you. What’s more, neither does any husband and wife here have any reliable advice.

To put the crux of the matter theologically, if love is grace, then there is no law to ensure it will perdure.

On the upside, this means I have just freed you from having to listen to your parents.

I am not here to offer you advice for the course ahead. I am here to speak for the Author of the story you will call “us.” I am here to speak for God.

As bold as that may sound, I can up the ante.

That Jesus lives so as to be able to speak through a sinner like me is the necessary condition for the two of you to make otherwise impossible promises to one another.

In the scripture passages, the apostle Paul describes the attributes of the covenant of which your vows incorporate you. “Rejoice in hope,” Paul exhorts the church in Rome, “be patient in suffering.” Likewise, the apostle commends to the Corinthians a love that “is not irritable or resentful.” Paul overwhelms us with adjectives that may obscure the straightforward teaching of scripture.

Namely—

To love is not to give something (kindness, patience, constancy, etc.).To love is to give yourself.All the other gifts and affections I may give to my beloved are really mere tokens of the only thing which I have to give and that is the gift of myself. It is not my absent patience that wounds but my absent mind— that is, my forgetting to give nothing less than myself.

To love is to be patient and kind.

But to be patient and kind is not to love.

To love is not to give something.

To love is to give yourself.

Indeed we have nothing to give except ourselves.

But just how can I promise another myself?

Here’s the rub that the ancient vows obtrusively make plain: I am going to die.

In fact, none of us is getting out of life alive; therefore, none of our promises can be truly unconditional precisely because they are all conditioned by death.

Whether you’re a believer or not, the brute fact is incontrovertible.

The future is the one thing we cannot promise.Thus, we cannot truly give ourselves to another.While the two of you have composed your own vows to bind your union, the rude conclusion to the traditional vows (“Until we are parted by death”) is nevertheless latent in Paul’s beloved song to Love. After all, as Andrew, who remains one of my brightest confirmation students, knows, the love of which Paul speaks in 1 Corinthians 13 is not a description of human love but Christ’s love— or rather, Christ himself.

“Faith, hope and love abide,” Paul writes, “but love never ends…”

Only Jesus, who was before creation and who was raised from the dead, is without beginning and end. Jesus is the Name Paul names with love: “Jesus is patient, Jesus is kind, Jesus is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. Jesus does not insist on his own way.”

Jesus is the name for Love.More to the point, Jesus is the world’s only true lover, for Christ’s gift of himself to you his beloved was not conquered by the grave. Jesus did not get out of life alive, yet he lives with death behind him. The wedding liturgy begins with a remembrance of your baptism, in which you died with Christ. And now I speak for God in reminding you that the one in whom you died promises to you, “Because I live, so shall you live.”

Hence, on this basis and only on this basis, you can love. Your future is Christ’s and he gifts it to you to give to each other. Because he promises, “I am the Resurrection and the Life,” you can promise to one another, “I do.”

Leave the God who raised Jesus from the dead out of the equation and to love is simply a means to eat, drink, and be merry before we die.

Because your future is his to give, because you too will live with death behind you, because you are in him by water and the Spirit, your love may go farther than patience and kindness (even though your patience will often be in short supply and your kindness will prove fleeting). Jesus promises exactly this when he says after washing his disciples’s feet, “A new command I give you.”

This is something different.It’s not, “Love God and love your neighbor as yourself.”It’s, “Love one another as I have loved you.”Christ is the end of a love that need not go further than self-love as the standard. But the way Christ has loved us is nothing like the way we love. Love broke bread with those he knew would betray him with a kiss. Even in the midst of their betrayal, Love says to them, “I call you friends.” Love gave his life not for the good but for the ungodly. Love loved his enemies, and, as every married person here already knows, the ability to love your enemy is often the necessary condition to love your spouse.

The way Love has loved us is nothing like the way we love even ourselves.

Nevertheless!

The Love who lives with death behind him insists we can so love.Such a claim is intelligible only to the extent we are willing to be as arrogant as the New Testament is when it proclaims that the church is the body of the Risen Jesus and the temple of his Spirit.From this day forward, your marriage is an outpost of the people called church and therefore your relationship is constituted not by two people. There is a third person. Your love can do better than patience and kindness. You can love according to Christ’s new commandment because while you two today will give each other rings, I will give you what alone makes love possible.

Like I said, I don’t have any advice for the two of you except perhaps the warning that there are days before you where simply scrubbing the toilet will strike you as heroic work (at least that’s what my wife says).

I don’t have any advice.

But I can— by Christ’s authority alone— lay my hands upon you and bestow you with the Holy Spirit. His love is genuine because it’s always grace. And because his love is grace, his bond to you irrevocable.

The way forward from this day can never be known. That your future is unknowable is what makes this act a beautiful risk and a leap of faith. Whatever the Author of your story has in store for you, hear the good news.

The story you will call us is not the story of you two. From this day forward, in better and in worse, there will be always a third. The Holy Spirit who just is the love between the Father and the Son.

Therefore—

As the Lord says so often in scripture, I say to you: “Do not be afraid.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

March 2, 2024

Starting with God

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Hi Friends,

Apologies for the delay! I am out of town to celebrate a wedding and I did not pack my laptop and editing this proved harder on my iPad than I anticipated. I will enjoy my forgiveness and remind you that we will be talking again with Rabbi Joseph on Monday night at 7:00! If you have questions for Rabbi Joseph, drop them in the comments or shoot me an email!

Show Notes:SummaryIn this conversation, Rabbi Joseph and the host discuss the importance of sharing scripture and the challenges of interpretation. They explore the defining characteristics of God, Torah, and Israel, and the need for critical reading of scripture. They also discuss the continuity between Judaism and Christianity and the complexity of translations. The conversation concludes with a discussion on the language used in communal prayer and the importance of respecting different beliefs while finding common ground. The conversation explores different concepts of God and the challenges of praying together. It delves into the inexplicability of God and the importance of embracing the mystery. The interpretation of scripture and the understanding of Israel are also discussed. The conversation touches on the Trinity and the differences in beliefs between Judaism and Christianity. It explores the concept of non-biblical Judaism and the challenges of interpreting the Bible in the modern world. The significance of the Ten Commandments and the different interpretations of Judaism are also explored.

TakeawaysSharing scripture is essential for understanding and appreciating different religious traditions.

Critical reading of scripture requires considering different contexts and interpretations.

There is continuity between Judaism and Christianity, and both share a belief in God, Torah, and Israel.

Translations of scripture can vary and impact the understanding of the text.

In communal prayer, it is important to find language that is inclusive and respectful of different beliefs.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 29, 2024

Learning the Creed with Karl Barth

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Show Notes:SummaryThis conversation explores the necessity of professing Jesus Christ's conception by the Holy Spirit and birth from the Virgin Mary. It delves into the mystery and humanity of Christ, distinguishing the incarnation fr…

What Would Jesus SAY?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Here is my latest conversation with Rabbi Joseph, in which we discuss this essay in The New Yorker.

Show NotesThe conversation explores the role of the Pope in times of conflict, particularly in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It discusses the limits and possibilities of the Pope's role, the value of silence, and the complexity of the conflict. It also delves into the reevaluation of Zionism and the loss of moral clarity in the face of ongoing violence. The conversation emphasizes the need for humility, acknowledging the limits of our understanding, and the importance of coexistence.

ChaptersIntroduction and Article Summary

What Would Jesus Say?

The Limits of the Pope's Role

The Value of Silence

The Plight of Christians in Palestine

The Role of Moral Authorities

The Complexity of the Israel-Palestine Conflict

Reevaluating Zionism

Moral Clarity and Unknowing

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 28, 2024

There is No Reward for Your Virtue

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Exodus 20.1-17

For the Second Sunday of Lent, the lectionary offered the church Paul’s presentation of what became the Reformation’s slogan, Justification by grace alone in Christ alone through faith alone— apart from works. In an apparent contrast, the lectionary’s Old Testament text for this coming Third Sunday of Lent is the Lord’s giving of the law to Moses on Mt. Sinai in Exodus 20.

The two Sundays thus give us God’s “Two Words.”

Law and Gospel.

Or, as Karl Barth rearranged them: Gospel and Law.

How can we understand Sinai this Sunday in light of the slogan from last Sunday?What is the relationship between promise and command, done and do? Having heard last week that God rectifies us apart from any obedience on our end, how are we to hear this week that, say, we must not take the Lord’s name in vain?

For Protestants, the slogan is our starting point, justification by faith apart from works.

The obverse of the Reformation mantra is that our work— good or bad— serve a purpose otherwise than making us righteous before God.

As Robert Jenson notes:

From its inception, Protestants have both been offended by and retreated from the proclamation at the heart of their preaching movement.“If I feed my hungry neighbor, I need seek in this act no judgment of my life, his life, or even of our life together. My life is undoubtedly a better one if I feed him than if I do not, on several scales of ‘better and worse.’ But my life is no more justified. To the question, ‘ What is your excuse?’ I have no more answer if I feed hi than if I do not.”

Not only is justification by faith apart from works the doctrine of predestination put in the passive voice— thus making God the active agent in it all— the Reformation’s central slogan cuts the nerve of our moral narcissism.

The good news in the gospel is that we are not the good news.

The bad news in the gospel is that we are not the good news.

Just so—

To the question, “Why should I feed my hungry neighbor?” the article of justification demands a straightforward answer: So that your neighbor’s belly might be filled.

In the context of the Decalogue, “Why should I not bear false witness?” the article insists we answer simply: Because otherwise leads to societal chaos.

Of course, we can come up with other reasons why it may be a good practice to feed your neighbor (fuller bellies, fewer crimes, more fulfilled families), but the chief article limits how far our answers can veer. If our justification is by God’s grace alone— if the one-way love of God is the sole agent whereby we are righteous before God, then we can NEVER answer the question, “Why should I feed my hungry neighbor?” with anything of the sort: “So I may be justified in my life.”

Importantly, the Reformation’s mantra does not mean that we should serve our neighbor in a selfless way, hoping that the selflessness itself escapes the egocentric trap cautioned against by the article of justification.

Despite the church’s best efforts to obscure the message, the gospel really is as radical as it sounds at first hearing:

The gospel does not merely tell you that you ought not try to get anything out of your good deed for your neighbor.

The gospel insists that you cannot get anything out of your good deed for your neighbor.

The gospel is the good news that you will not be rewarded in any way for your good deed-doing.

In fact, it’s the purpose of the Protestant slogan to make you understand that only the message “You have nothing to gain from filling your neighbor’s belly,” can free you to attend to your neighbor’s belly.

As Jenson writes:

“To the question, ‘Why should I do good?' the radical gospel replies, ‘If you put it that way, no reason.’”

February 27, 2024

The End of Civility: Christ and Prophetic Division

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, pay it forward by becoming a paid subscriber!

Here is a conversation with Ryan Newson that is perfect grist for this week of Lent in which we hear of Jesus throwing a temple tantrum in John 2.

Show Notes

Show NotesIn this conversation, Ryan Newson discusses his book The End of Civility: Christ and Prophetic Division. He explores the concept of civility and its historical development, highlighting the different theories of civility put forward by philosophers such as John Locke and Thomas Hobbes.

Newson also examines the role of Martin Luther King Jr. and Jesus in challenging the status quo and the tendency to sanitize their messages. He critiques the idea of civility as a means to maintain the existing power structures and argues for a more nuanced understanding of when civility should be heeded or ignored. Newson also addresses the issue of Christians locating their primary identity in American civil life rather than the church and the challenges of political preaching. The conversation explores the themes of love, prophetic witness, communal discernment, and the avoidance of difficult conversations. It emphasizes the importance of following the character of Jesus and engaging in patient and discerning action. The discussion also delves into the fear of disruption and the need for balance in prophetic witness. It highlights the significance of processing emotions in public and the avoidance of living contingently. The conversation concludes with a reflection on white theology and the desire for control.

TakeawaysThe concept of civility has a complex history and different theories of civility have been put forward by philosophers throughout time.

Martin Luther King Jr. and Jesus both challenged the status quo and were not always seen as paragons of civility in their time.

The appeal to civility can be used to maintain existing power structures and silence prophetic critique.

The idea of separating theology and politics is problematic, as theology inherently has political implications.

Churches should be willing to engage in dialogue and discernment, even if it challenges the status quo and makes people uncomfortable.

Balancing law and gospel is important in preaching, as it allows for both prophetic critique and the message of grace and love. Love should be grounded in the character of Jesus as revealed in the gospels.

Prophetic witness requires complexity and communal discernment.

Patience and wisdom are essential in navigating difficult conversations and avoiding reactive activism.

Balancing love and disruption is crucial in prophetic action.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the appAbout the Book:

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the appAbout the Book:"I have come not to bring peace, but a sword." These words of Christ echo in our current times. In recent years, a growing number of commentators have decried a lack of civility in public discourse. Considered in isolation this concern is innocent enough, but no call for civility happens in a vacuum, and there is good reason to be suspicious of civility in our current political context. Calls for civility can encourage passivity and blunt prophetic action against injustice; truly heinous policies can be pursued under the guise of civility. And yet civility should not be dismissed outright, especially as presented by its more nuanced defenders―when it is presented as a limited good in a pluralist society.

In The End of Civility, Ryan Andrew Newson analyzes the development of the concept of "civility" as we know it in modern discourse and names some of the criteria Christians can use to judge between healthy and toxic appeals to civility. The challenge, Newson contends, is discerning when civility is called for and when its pursuit becomes vicious. Pleas for civility cannot be assessed without considering the context in which they are made. Some appeals to civility merely seek to lessen conflict, even conflict necessary in the struggle for a more just world. But when issued by people struggling for justice on the margins of society, calls for civility can name the types of conflict that might lead to liberation.

One must be attentive to what counts as "civil" in the first place and who gets to make that determination. Which bodies are considered civil and "ordered," and which people are under suspicion of being "uncivil" before they ever say a word? For Christians, civility can never be an ultimate good but remains subordinate to the call to follow Christ―in particular, the Christ who is not always "civil" but who calls people to an ethic of resistance to injustice and solidarity with people who are suffering.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers