Jason Micheli's Blog, page 52

February 4, 2024

Inspired Stumbling Blocks

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

1 Kings 18.40-46

The New Testament Book of Hebrews exhorts followers of Christ to sabbath rest on the grounds that "the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart.”

In other words, the word does not record; the word works surgery upon us.

Two thousand years later it may surprise Christians that the word of God so named by the Book of Hebrews is the Hebrew Bible.

What we now call the Old Testament was the only scripture known to and authoritative for the apostles. Accordingly, the New Testament has a different, more provisional authority than the Old Testament. Whereas the scriptures of Israel were the unquestioned Bible of Mary’s boy and so authoritative, the New Testament canon came together under emergency duress.

A second century bishop named Marcion of Sinope took it upon himself to codify the very first Christian canon. Marcion divided his proto- New Testament into two sections, the Evangelikon, which was a shorter version of the Gospel of Luke, and the Apostolikon, which was a selection of ten Pauline epistles.

One of Paul’s most radical apprentices, Marcion allegedly understood the apostle Paul so well that he ultimately misunderstood Paul and his message. What prompted Marcion to codify the church’s own scripture was his revulsion over the violence and evil displayed in the Old Testament and often attributed to its God.

Reading the Hebrew Bible, Marcion insisted that the God of Israel could not possibly be the Father of the Lord Jesus Christ.Consequently, Marcion rejected the Old Testament outright and excised from apostolic documents any sections he found offensively Jewish. Marcion was the first in the church to posit a distinction between the "wrathful Jewish God" of the Old Testament and the “loving God of Jesus Christ.”

By contrasting the God of Israel with the one true Israelite, Jesus Christ, Marcion pitted the Father against the Son and so ruptured the Trinity. Just so, the church excommunicated Marcion as a heretic and repudiated Marcionism as heresy in 144 AD and, forthwith, before another Marcion could rear his head, the church cobbled together the canon we now call the New Testament.

Marcion was an antisemite probably.

Marcion was a fundamentalist certainly.

Marcion was a heretic incontrovertibly.

Nevertheless!

Marcion was not irrational.Only a liar would argue the Old Testament never seems to portray Yahweh in ways incommensurate with Christ and him crucified.

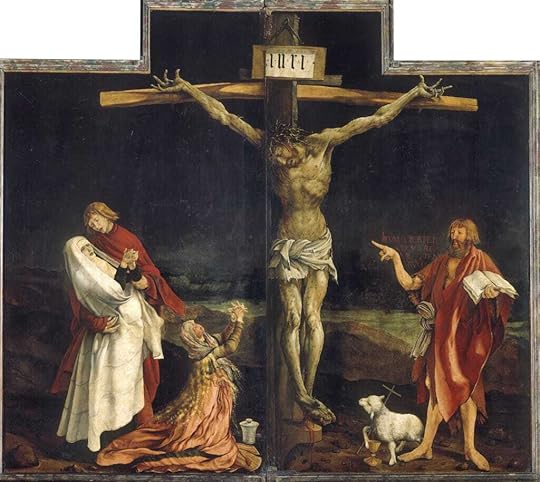

But if Jesus is who scripture attests, “the image of the invisible," then what do we do with passages like this passage in the Book of Kings where, having answered the prophet’s prayer with fire, the Lord leads Elijah to drag the false prophets of Baal down to the Wadi Kishon to kill them.

All four hundred and fifty of them.

It’s a strict stipulation of the doctrine of the Trinity that whatever you may say about one person of the Trinity you may say about another person of the Trinity.

For example, “The Holy Spirit created heaven and earth.”

And, “On the cross, God died.”

Or, in this case:

“Jesus commanded Elijah, saying “Seize the prophets of Baal; do not let one of them escape.” Then they seized them; and Elijah brought them down to the Wadi Kishon, and, according to Jesus’s word, he killed them there.”

Marcion was not unreasonable.

I remember my first summer as a preacher.

The church was in Year B of the lectionary and the assigned Old Testament passage for that Sunday of July was from 2 Samuel 6.

The story of Uzzah and the ark.

Dew was still burning off the grass in the parking lot as people trickled into the sanctuary.

Because Irma, the organist, wanted to take a break that Sunday, the morning’s music was led by her husband Les, who was as deaf as anyone I’ve ever met and who played the accordion in tones I can only describe as “asthmatic kitty.”

Because I was not only new to preaching but relatively new to the faith, I didn’t know any better and I treated the scripture text as straight up as Marcion of Sinope might have interpreted it.

In case you have forgotten it, 2 Samuel 6 reports King David, having defeated the Philistines, reclaiming the ark of God to take it to Jerusalem.

With thirty thousand soldiers celebrating before the ark with lyres and harps and tambourines and castanets, David dances half-naked. At a certain point in the procession, however, the oxen pulling the cart on which the ark rested “stumble.”

The oxen stumble.

The cart rocks.

The ark tips over.

And the poor bastard walking beside the cart— Uzzah— reaches out his hand to steady the ark of God to keep it from falling.

That’s all he does.

But, reports the Book of Samuel, “the anger of the Lord was thus kindled against Uzzah, and God struck him down there because of his error.”

Back then, I knew the Lord. But I did not yet know how to read his word. Or preach it.

I knew the Risen Lord; he had encountered me. But I did not yet know how to seek him in the scriptures. That Sunday, I took the text matter-of-factly.

The congregation that day they listened politely, but I could see. I could spy it from Sheldon sitting in the front pew and from Bob seated halfway back and from Andy all the way in the back by the aisle— I saw they didn’t care much about about the ark, or about Kingdom history or about David’s political maneuvering.

I could see in their furrowed brows and anxious faces.

They wanted to know about Uzzah.

At that point in my ministry I wasn’t very observant from the pulpit, but that morning I could tell that ever since Pam had read the scripture aloud everyone in the congregation was wondering, “Well, wasn’t Uzzah just trying to help?’

I pressed ahead anyway.

According to 1 Samuel 6, I told them, the ark was supposed to be carried on poles by Levites, Israel’s special caste of priests.

But that’s not what happens here. Either everyone had forgotten or, in their rush to get the ark to Jerusalem, they didn’t care. So instead of on gilded poles, it’s put on a wagon. Instead of being carried by priests it’s pulled by oxen.

In other words, according to this interpretation, Uzzah dies because he didn’t follow the directions.His haste to catch the ark is actually his trying to avoid the consequences of his actions. In other words, he had it coming to him.Seeing their sphincters tighten, I conceded— I still have the manuscript:

“You can parse this passage a hundred different ways. But the bottom line is that Uzzah’s death is meant to be a reminder of God’s holiness. Uzzah’s death is meant to point out to us what it points out to King David— that this God is not One with whom we can trifle.”

And from there I wound my sermon to a close with a litany of DON’Ts.

Don’t reach out to this God if you’re aren’t serious about it, if you don’t want an answer or won’t follow through.

Don’t live any way you want, just coming here once a week, taking God’s mercy for granted.

Don’t come to Christ’s Table if you’re not sincere about living according to his Kingdom.

DON’T.

Don’t confess your sins if you’re not going to live a redeemed life.

Don’t pray if you’re not going to heed the answer.

Don’t come here on Sunday if you’re not here to worship.

This God is not One to treat casually. This God has the freedom to be angry. And his righteous wrath has the power to knock you down. Faith in this God is not for the phony or feeble-hearted. Faith in this God is like playing with fire.”

I preached.

And if memory serves me right I even wagged my finger at them.

Looking back, I suppose it was a bit intense for what was only my second Sunday at that church.

But not only was it too intense— all law— it was unworthy of Jesus.As it happens, in short order the Lord Jesus would show me my interpretation of his word was not worthy of him.

And Jesus would use that very passage— that text of terror— to teach me.

The Jewish philosopher Martin Buber recalls a day he sat on a train next to a stranger Buber quickly deduced was a devout Jew. Soon the philosopher found himself confessing to the worshipper his revulsion at a particular passage of scripture the stranger was reading, Saul’s slaughter— on the Lord’s command— of all the Amalekites.

Buber confided to the stranger that the Bible passage had perplexed him since he was a boy.

He confessed to his fellow passenger, “I have never been able to believe that this is a message of God,” Buber told his train mate, “I do not believe it.”

In reply, Buber writes, the stranger’s glance “flamed into my eyes” like a surgeon’s scalpel. Then the man merely sat silently for a long duration, pondering the philosopher’s words in his heart. After a while, the stranger asked Buber, “So, you do not believe it?”

The philosopher said he did not.

The stranger nodded.

A few beats later, the stranger asked him again, this time almost threateningly, “So, you do not believe it?”

Buber again said he did not believe it.

The stranger asked again— three times— “So, you do not believe it?”

And Buber replied:

“I believe that Samuel misunderstood God.”

Both of them then fell into silence, Buber recalls, until the stranger asked again, “So, you believe that?”

“Yes.”

“Suddenly, the man’s anger vanished.”

And Buber writes that the stranger looked up at Buber and smiled, like a teacher to a student, “Well, I think so, too.”

Looking back on the train ride, Buber observes how it surprises him, even years later:

“There is in the end nothing astonishing in the fact that an observant Jew, when he has to choose between God and the Bible, chooses God: the God in whom he believes, Him in whom he can believe. And yet, it seemed to me at that time significant and still seems so to me today.”

After worship that Sunday in July, Uzzah’s unfortunate fate still ringing in everyone’s earballs, a woman in her late thirties came up to me at the church doors.

She had a streak of white in the black hair she wore pulled back into a ponytail. She was crying. And clearly she had been crying. Her cheeks were wet and her eyes a tired red. Like my first Sunday, she’d come alone to worship, clutching her purse like a teddy bear.

She took off her glasses to blow her nose, and then she stared at me.

She didn’t look angry. She looked like I’d pulled the rug out from underneath her. Or like she’d just crashed against the scripture. And now she was falling.

“I never thought I would be able to get pregnant,” she said to me well above a whisper. She was too upset to worry who might overhear her. “I never thought I would be able to get pregnant— that’s what the doctors always told me. But then, by some miracle, I did. My husband and I, we even called it that, “Our miracle.” We called it that for six months. And then last month we lost her.”

Sadie.

She looked at me, and I felt all her grief being imputed to me.

And immediately I wondered if my LSAT scores were still good for law school.

Then she said, “Your sermon— that scripture, the God you described…all I kept thinking…”

She shook her head side to side and her voice trailed off.

“Yes?”

This time she got loud.

“All I kept thinking throughout your sermon was WHAT ABOUT UZZAH’S MOTHER?! WHAT ABOUT HIS MOTHER?! What about her?! What word do you have for her?!”

WHAT ABOUT UZZAH’S MOTHER?!

And just then I felt like the one who’d been dashed against the passage.

Busted and broken.

And in need of surgery.

Like a gaping wound, I suddenly saw that the Lord who had encountered me and summoned me to faith and called me to ministry was not the same person I had just preached.

In his book On the Inspiration of Scripture, the theologian Robert Jenson points to the many medieval paintings which show the Holy Spirit hovering beyond a biblical writer as he puts his witness to the page to compose the canon.

It is our tendency to think of the Spirit’s relation to the scriptures as extrinsic— outside of us— and historic— back before us— that is the chief error that has distorted the church’s understanding of the inspiration of scripture.

“The pictures that show the moment of inspiration as the Spirit bending over a busily writing prophet or apostle,” Jenson writes, “depict the wrong scene altogether.”

Because, of course, as we acknowledge at every baptism and in every prayer meeting, “the mighty acts of God” go on today.

The apostolic church enjoys no advantage over us in terms of the Spirit’s activity.To make it plain:

The scriptures were not inspired by the Spirit.

The Spirit inspires the scriptures.

The Spirit inspires with the scriptures.

The doctrine of inspiration does not mean that the Bible is a record of reliable information about God. Of course that’s not what it means— rabbits don’t chew the cud, as the Book of Leviticus seems to think.

The doctrine of inspiration does not mean that the Bible is a record of reliable information about God.The doctrine of inspiration means that the Bible is the reliable way God acts savingly in our lives.The correct picture of scripture’s inspired nature is not the picture that shows the Spirit bending over the narrator of 1 Kings or Paul as he writes to the church in Corinth. The correct picture is, well, you and me, waiting like Moses in the cleft of the rock, for the Lord to pass through a passage of scripture: “May the words of my mouth and the meditation of all our hearts be your living word…”

Just so—

When it comes to scripture, the question is not How.How can we know the scriptures are true?When it comes to the Bible, the questions are Who and Why.Who has given us the scriptures?And why has the Lord given them to us?That is, who is he making us to be?In other words, before you have a definition of scripture’s authority, you must be able to answer the question, “Saved for what? To what End has the Lord acted for us in Jesus Christ?”

Once again, the passage from the Book of Hebrews provides the answer. Your sin belongs to Christ and his righteousness is your permanent perfect record; so that, we would become both a temple and a kingdom of priests for the sake of the world.

Fundamentally, the word is no different than water, wine, or bread. The Lord gives us the scriptures in order to make us holy.

The Lord gives us the scriptures in order to make us holy by our encountering him there.He uses scripture to do surgery on us. He uses scripture to cut away the parts of us that do not comport with him. As scripture itself attests, "the word of God is sharper than any two-edged sword, cutting joint from marrow, and exhuming the thoughts and intentions of the heart.”

If the Bible is not a record of reliable information about God but is instead the reliable way God acts savingly in our lives, then it surely follows that God can use even the troubling texts of scripture to sanctify us.

In fact, this is what the ancient church fathers called “spiritual exegesis.”

According to the church father Origen, scripture is inspired in that it is divinely designed exactly to elicit our troubled response that in turn sanctifies us.

That is to say, the Lord intends for us to trip over certain scriptures so that we fall in to the mercy of the true God.

Remarking on the difficulty presented by Old Testament passages like 1 Kings 18.40, Origen commented:

“The Word of God has arranged that certain stumbling blocks, as it were, and obstacles and impossibilities be inserted into the midst of the Law and the narrative, in order that we may not be drawn away completely by the sheer attractiveness of the language and so we either completely reject the teachings, learning nothing worthy of God, or, not moving away from the letter, we learn nothing more divine.”

In other words—

Scripture sanctifies us not by merely reporting information about God.

For example, “God is love.”

Scripture sanctifies us by catching us up in our assumptions about God.

For example, it’s not God who is called into question.

Today, it’s not God who is called into question; its Elijah.

Notice the passage never explicitly says God told Elijah to slaughter the prophets of Baal.In our sin and unbelief, we supply the summons— and I’ve gotten you this far into the sermon assuming it was so.I lured you into thinking the Lord probably issued such an order.But verse forty does not begin, “The word of the Lord came to Elijah, saying, “Seize the prophets of Baal…”” Look again, it’s not there. And turn to the next chapter, what do you discover? Elijah is depressed and bereft, lamenting that he was zealous for the Lord but the Lord is now with him not.

Why?

Because in his zeal for the Lord, he took it upon himself to execute the four hundred and fifty prophets of Baal. He did that act, and—like so many believers today— he attributed his actions to the Lord.

According to Origen, the Lord providentially sticks stumbling blocks into the Bible precisely so that we will trip up and tumble over and fall into his gracious and loving arms.In other words, the ugly parts and nasty bits are there for a purpose. Or, as the Protestant Reformers put it, we are mortified and vivified in our encounter with the troublesome texts of scripture. They open us up and expose us. And, so doing, they heal us.

“WHAT ABOUT UZZAH’S MOTHER?!”

She asked me in the exit line— no, she demanded of me.

I stammered.

Until finally I said, “Well, what would you say to Uzzah’s mother? I suspect she’d rather hear from you.”

And then she took my hands— both of my hands— and placed them on the belly where her baby had been.

I attempted to ignore the shame flushing on my cheeks and the tears welling in the corners of my eyes.

She looked me straight on— damn the vulnerability— and she said, “I think God’s power and presence and holiness was found not in a gilded box that could blow at any time, but in the ark of a mother’s womb, like Mary’s womb.”

“Like this one,” and she pressed my hands deeper into her belly.

She held my hands there and said, “On those same grounds, I refuse to believe what you said and I don’t believe you really believe it. I don’t believe that God takes us from us for reasons all his own. I believe that God loves us so much that he gives, gives even himself.”

She released me from my her grip.

My hands fell back from her belly.

They landed at my sides like I was a patient on an operating table.

“I guess I’d say something like that to Uzzah’s Mom. What do you think?”

“What do I think? I think the Lord stuck this passage into scripture; so that, you would preach this precise word. To me. Today.”

The word of the Lord is not always comforting Frequently, it is confusing. Rarely, is it finished.

So come to the table.

It is more than a supper table; it is an operating table.

The word has opened the wound.

So come to the table. With word and wine and bread, let the Great Physician finish his work. To make you what you otherwise would not be.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 3, 2024

Learning the Creed with Karl Barth

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Hi Friends,

I hope you are having a wonderful weekend. As a thank you to the tribe of paid supporters who make this little hamster wheel spin, here is the second installment of our series “Learning the Creed with Karl Barth.”

Show Not…February 2, 2024

Nine Exhortations for Preachers

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers! Seriously, do it.

I was at a coffee shop this week, working my way through my inbox, when I overheard a customer speaking casually with his table mate about hell and the eternity of its infernal torments. Like Samwise eavesdropping at the window of Crickhollow, I listened to their— again, casual— conversation and I muttered to myself, “If you truly believed what you’re saying, then you’d be moving about this place like madmen attempting to rescue the rest of us.”

The ease with which they so spoke of God betrayed that it was not God of whom they spoke.

It was a garish instance of a fact of faith that Christians seldom stop to acknowledge. Namely, we do not have any idea what we are doing when we speak of God. We do not have any idea what we are doing when we speak of God; therefore, we should not do it. We do not have any idea what we are doing when we speak of God; unless, God has first spoken to us. We do not have any idea what we are doing when we speak of God; unless, God has first spoken to us, in which case we should stick stubbornly to what God says to us.

This suggested reticence may sound surprising, yet it is a straightforward implication of the doctrine of justification.When Christians understand the doctrine of justification (in Christ alone by grace alone through faith alone) as a doctrine of the church’s beliefs rather than a rule to govern the church’s speech, they fail to appreciate that the gospel is not only the content of the church’s speaking it is the control over all other God-talk.

If the gospel-promise is unconditional, it must be God’s word and not merely our word. Only God can be the Promiser of the gospel-promise, for only God can make an unconditional promise. All our promises are bounded by and founder against death. If God alone is the Promiser of the gospel, the speaking of the gospel just is God’s living reality.

Just so, the gospel is not relativized by another reality.Thus—

There is no way to move from speaking the gospel to some other more complete or fuller reality of “God.”

And there is no way to move from some other more complete or fuller reality to the particular word called gospel; e.g., you cannot get from the god with whom you connect on the golf course to a Jew who lived briefly, died violently, and rose unexpectedly.

Put differently, as Robert Jenson puts it:

“The Christology of the entire church is an assault on inherited pagan ways of conceiving God and his relation to us; it seeks to interpret the reality of God entirely by what happens with Jesus.”

Christologically, the gospel is the message that God meets us “otherwise than abstract deity.” The unconditionality of the gospel is simultaneously the insistence that God does not at all meet us as abstract deity. The God of slogans such as “God is love” is not God and we should surely cease to speak of him. Not only are unbelievers right when they suspect we know not what we’re doing when we speak of God (unless, that is, God first speaks to us), even our proclamation of the gospel is a partial utterance.

Because the gospel is a promise— a promise about the future— Christian proclamation, not unlike scientific discourse, is an assertion, a positing, a hypothesis which awaits verification.

I cannot prove that you will, like the Lord Jesus, live with death behind you until the Fulfillment comes and we both discover whether the proclamation was true or false. Hence, Christian proclamation is necessarily eschatological; that is, Christian preaching is dependent on the End for its verification or falsification. The fellow in the coffee shop yesterday did not appear to speak with a humility such future confirmation requires.

The fragility of all human God-talk and the precise nature of what humans are, in fact, authorized to utter about God suggests a kind of rule of parsimony when it comes to speaking of God, to say nothing of speaking for God.

Commending such parsimony, Robert Jenson sketches several exhortations on proclamation. In the spirit of hortatory, Jens frames then in the form of lettuce sermons, “Let us.”

Let us talk of God matter-of-factly.

Our utterances containing “God” must all be, at least implicitly, informative statements about the man Jesus of Nazareth and what he has done and will do. If we find ourselves about to say something about God and are in any doubt that this is so, let us keep silent.

Let us resolutely avoid all talk of God as being “out there” somewhere.

And let us more resolutely avoid all talk of God as “the principle” or “force” or “immanent reality” of something or other. If we want to say that God is “love” then let it be clear in every turn of the discourse that by “love” we mean neither a great Lover out there nor that prime nonesuch, love-in-general or “the principle of love,” but Jesus’s love, what he did and will do. This is not a mere exhortation to “Christocentric.” There is a way of talking about Christ or Jesus where he too loses his matter-of-factness. The “Jesus Christ” who is simply the God of popular theism is no improvement. And to baptize spirituality-in-general as “Jesus” changes little: “Jesus is love in general” is even hollower than “God is love in general.” Let our rule be: We will about “Jesus” only that to which the history of Jesus could be in some way relevant.

Let us avoid analogies.

If we are to say something about God that if pressed we will have to explain in terms of analogy, picture, symbol, or the like, we will not say it. If we are to say something about that “only believers can understand,” then we will admit that we do not understand it either, and not say it.

Let our talk of God be a word-event.

Back to the guy in the coffee shop, casually speaking of eternal conscious torment to anyone in earshot. Whenever we are about to say “God,” let us stop and ask: Suppose my utterance is affirmed by my hearers, what step in his or her life will that affirmation be? If we are not sure that it will be any step, let us keep silent.

Let us understand uttering “God” as an act of violence upon the hearers.

For better or worse, if he or she hears, they must come from the experience of hearing a different man or woman than they went in. Let us speak the law as executioners and the gospel as friends at the cell of the condemned. If we are to speak of God, let us remember: We will be commanding, blessing, cursing, complimenting, and insulting our hearers.

Let us deliver the goods.

Here is the terrible and almost complete failure of our preaching. Our preachers do not proclaim absolution: they say, “Go home and tell God about it and he will forgive.” We do not bring the good news; we say, “The good news is in the Bible. Read it diligently.” It must clear; such preaching does not say anything about God at all. For God is real for us only as the word-event in which we then and there, as speakers and hearers, are condemned and rescued.

Let us be parsimonious in our speech about God.

Let us say “God” only when we cannot absolutely avoid it. This is not a recommendation of retreat to silent inwardness. The point is to speak always so that the truth of our lives occurs in our speaking— and to speak of Jesus Christ so that in this speaking the truth of our lives is uttered. If we do this, then ever and again we will not be able to avoid “God” until the day when Jesus confronts us, and all our truth will uttered in an utterance of “God” that will take all of eternity.

Let us use many future tenses.

To speak of Jesus matter-of-factly is to speak eschatologically. It is only in that we tell about Jesus as about the end of our human story that a transforming word-event can occur as factually informative narrative. When we use past tenses, then let us do so in the context of the one particular past tense: “He rose.”

Let us speak of God in fear and trembling.

Because the gospel is a promise about the future, the language of faith is never achieved in the meantime. We speak faithfully only when we make clear that the promise will one day speak the meaning of life in God. In the meantime, let us speak in fear and trembling and in reliance on forgiveness, saying, “Here, Lord, is what we must say. If we misspeak, forgive us.”

It seems then, in light of the gospel, that the traditional plea of the psalmist is the wisest course for proceeding in speaking of God, “May words of my mouth and meditations of all our hearts be acceptable in your sight, O Lord, our rock and our redeemer.”

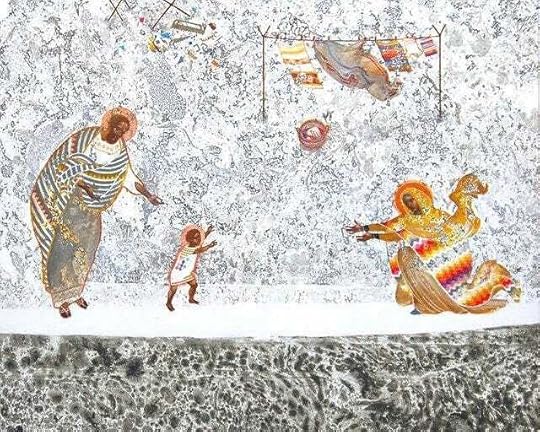

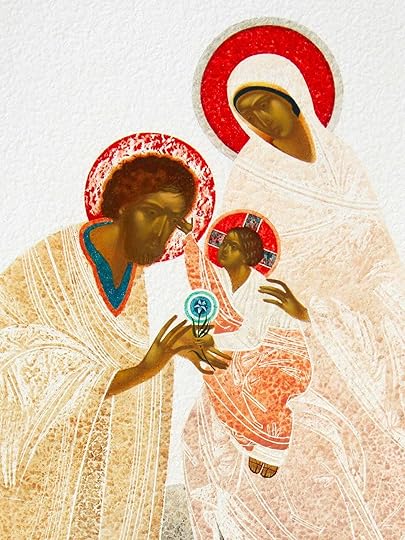

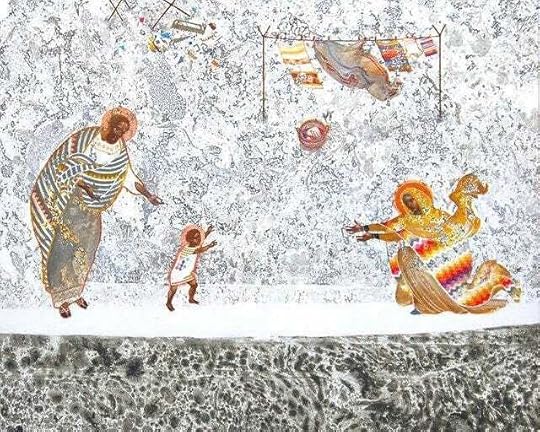

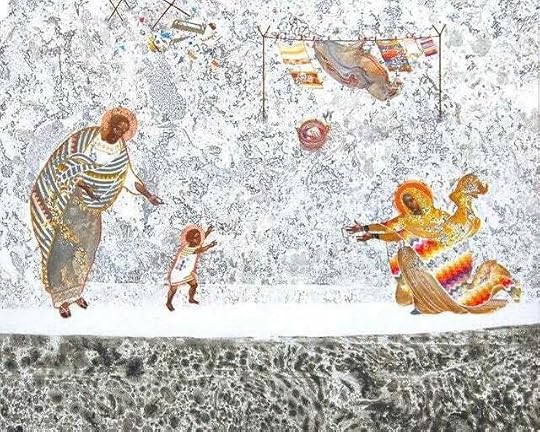

(“Visible Words” by Chris E.W. Green)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

February 1, 2024

Pray with Your Feet

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Hi Friends,

Here is the latest conversation with my friend Rabbi Joseph Edelheit. This week we discuss the recent op-ed by Yehuda Kurtzer of the Shalom Institute, whose title is “We must continue to support Israel’s war — and honestly grapple with tough questions from critics (copied below).”

Many new folks have recently subscribed to this site. If you missed it, HERE is the first conversation with Rabbi Joseph in the immediate aftermath of the 10/7 Massacre.You can find the other weekly installments in the archive.

Don’t forget—

You can join Rabbi Joseph every Monday evening during Lent as we discuss his book, What Am I Missing?

Learn more and register HERE.

Show Notes:SummaryThe conversation explores the ongoing conflict in Israel and Palestine, focusing on an article by Yehuda Kurtzer. The chapters cover topics such as the complexity of the conflict, the length of the war, critiques of the war, the death toll and proportionality, political divisions and protests, the fate of the hostages, the question of victory, moral imperatives and various opinions, personal reflections, and the need to prepare for the final accounting. The conversation emphasizes the importance of prayer and action in addressing the complex issues surrounding the conflict.

TakeawaysThe conflict between Israel and Palestine is complex and multifaceted, with no easy solutions.

The death toll and proportionality of the war are difficult to determine and quantify, making it challenging to establish a clear threshold for acceptable casualties.

The fate of the hostages and the dilemma of negotiating with terrorists raise moral and ethical questions.

The concept of victory in the conflict is complicated, and there are no clear winners.

The ongoing conflict has led to divisions and tensions within communities, both in Israel and globally.

Prayer and action are necessary to address the complex issues and work towards a just resolution.

Here is the article which guided our conversation:

Yehuda Kurtzer

At the outset of the war in Gaza — a war that Israel did not seek, a war triggered by a heinous attack by Hamas — I argued in the Forward that our responsibility as Jews was to define the war as a “just war” and to commit to support Israel’s fight.

I understood myself then to be an “Amos Oz Zionist,” following the model of the late Israeli author who broadly identified with the politics of the left and was an outspoken critic of the Israeli occupation, but who consistently supported the moral and political necessity of Israel’s military response to Hamas’ history of brazen violent incursions.

In 2014, a German reporter asked him, “Are you among the 85% of Israelis who want the offensive to continue until the strategic goals of destroying the tunnels and rockets are reached?”

Oz responded: “Unlike European pacifists I never believed the ultimate evil in the world is war. In my view the ultimate evil in the world is aggression, and the only way to repel aggression is unfortunately by force. That is where the difference lies between a European pacifist and an Israeli peacenik like myself.”

The challenge for liberals in this just war moment is to support the fight and hope it is fought justly and speedily. I find affirmation in the philosopher Michael Walzer’s words: “Now I pray for a smart war and a smart politics afterward.”

But it is also true that as the war drags on, it is getting harder to hold onto this view. The costs of the war are profound: thousands of Palestinian deaths, incalculable destruction in Gaza, and a constant stream of the news of deaths of Israeli soldiers from whom I often have but one degree of personal separation.

It is our responsibility to reckon with the arguments of those who challenge the morality of continuing this war, as difficult as doing so may be. Should we limit our support? Is there a limit to the blood sacrifice we must demand or endure in support of even a just war? With the passage of time, some of the initial broad consensus American and American Jewish support for the legitimacy of the war is starting to fade.

Public opinion is still on the side of Israel against Hamas, and when those are the two choices, thank God for that moral clarity. But various liberal Zionist organizations have gradually shifted their stances about the war, from opposing the calls for a cease-fire in the early days to tentatively embracing them. I do not agree with those decisions, but I do not fault them. The visible failings of many in the global left over the past 114 days have done little to assuage my own anxiety about where I stand on this war. The rape denialism among progressive groups, the slanderous overreach in characterizing Israel’s behavior as genocide, the quick leap to calls for ceasefire instantly after Oct. 7 — denying Israel the legitimacy of selfdefense — and the regular omission of calls to release the hostages as part of the ceasefire conversation are all colossal moral failures, and they have helped me understand my own political positionality. Israel has just cause in its victimhood, and just cause to fight back.

However, just because the most extreme articulation of an anti-war position caricatures itself in this way does not mean that there is no room for legitimate skepticism about the war. No war should be able to demand indefinite loyalty. I see three critiques of the war that we must seriously wrestle with if we are to, as I still do today, continue to support Israel in fighting it.

A rising death toll in Gaza

The first critique of the war is the death toll. Surely there must be a limit to supporting a war as the number of Gazan civilian deaths continues to climb.

But here is the thing: Since every death in war is a tragedy, there is simply no objective way to determine what quantity of deaths should be considered “acceptable” and when we cross an imaginary threshold to say that there are “too many.”

There is no doubt that some amount of the death and destruction inflicted by Israel in Gaza could have been prevented while achieving the strategic objectives of the war, as the IDF periodically admits, and it is encouraging to see that the strategy is changing and the daily death toll declining.

This is both an argument for ethics and an argument for better strategy. But the bulk of the blame is at least shared if not owned by Hamas, who routinely position themselves amidst a civilian population and does not always wear uniforms that help differentiate between civilians and combatants. The IDF is forced to make impossible decisions as they fight an urban war against an enemy entrenched amidst its civilians that stalwartly refuses to obey the rules of war and refuses to engage the military ethics to which Israel holds itself accountable.

I cannot say personally whether the Palestinian death toll demands an end to this war. I cannot say with certainty, and neither can anyone, what percentage of the death toll has been civilians and what has been combatants. But because leaving Hamas in place creates a permanent and imminent threat to Israeli lives, there is no obvious stopping point.

I feel that I can only pray for there to be fewer deaths going forward, and to rely cautiously on the knowledge that international law does not evaluate the morality of a war on the number of casualties, but rather on the justification of the war, its intent, and the way that it is prosecuted.

The fate of the hostages

The second critique of the war revolves around the fate of the hostages. Some argue that we must prioritize their safe release over the other stated military objectives of the war. Many of the hostages’ families are demanding that Israel do whatever it needs to do to “bring them home,” no matter the cost, and we are right to be chagrined in the presence of their public suffering.

The dilemma that Israel faces in balancing between the objectives of trying to defeat Hamas and trying to redeem our hostages is excruciating and laced with moral complexity. Hamas has successfully exploited the compassionate love that we Jews have for our fellow Jews, and their ruthlessness in seizing the vulnerable together with the healthy demonstrates that they know that the price we will pay is staggering. But now — is it too high?

The first negotiated temporary ceasefire resulted in a hostage-prisoner exchange with the most favorable terms Israel ever received, and it is reasonable to speculate that the force of the military effort helped coerce Hamas into such an agreement. Meanwhile other Israelis — who speak more quietly, out of fear of being perceived as being heartless — worry that the cost of the proposed future exchange of many terrorists with blood on their hands, and others who will incur blood on their hands, is simply too dangerous.

Is the price too high? I simply do not know. I do not know whether there are other levers to bringing home the hostages, beyond Israel ceasing its military objectives and leaving Hamas in power. I make no claim as to which of Israel’s horrifying choices is the right one. But I know that neither argument on this issue has a monopoly on moral certainty.

Can Israel win this war?

And the third important criticism against continuing the war is the claim that Israel’s objectives have not been met so far; or worse, that they cannot succeed. It is hard to tell if Israel is “winning,” with the Hamas leadership still in place. And the critique of how Israel is prosecuting the war is increasingly tied to speculation that an indefinite, purposeless war is a strategy that Prime Minister Netanyahu is employing to advance his own political aspirations.

I do not know whether it would take mere months or many years to weaken Hamas to the point of Israel being able to declare victory. But those that approach Israel’s military struggles convinced that the lack of certain victory after three and a half months means that the whole war plan was wrong, or that it was always an unwinnable fight, or entirely a political ploy, are, I believe, displaying a dangerous hubris that should be interrogated.

Is it possible that amidst the fog of war, some aspects of the Israeli invasion have succeeded more than we think? And most of all: if you have decided that you know enough to establish that this war is unwinnable by this strategy, what military strategy do you offer us instead?

These three arguments opposing continuing the war raise serious issues, questions and doubts. But they are not dispositive enough to create a moral imperative that we oppose this war.. Unlike the first weeks of this war, when supporting the war felt essential to ensure the legitimacy of Israel’s right to self-defense, I feel secure in my views but recognize the moral legitimacy of various opinions. I hope that others who take an opposing view feel the same.

The complex path forward

We have two easy choices before us as a Jewish community now, or an alternative path forward. The easy choices are the choices rooted in certainty: unapologetic support for the war that refuses to countenance these criticisms, whether they come from the outside or from our own evolving moral instincts; or unapologetic opposition to the war, broadcasting our opinions in endless open letters and petitions that likely alienate us more from most Israelis in the process. Both positions fall short; and their entrenchment against one another also threaten to rupture a Jewish community that needs to try to stay whole as best it can right now.

A third path forward, the one I choose, is that even as I support Israel in fighting this war, I am also leaning into the pain of the war without looking away. I am leaning into the many questions that I pose above, and I think this may be a moment for essential epistemological humility in the face of what we don’t know, especially those of us whose lives are not literally on the line; and an opportunity to try to inhabit a place of solidarity with Israelis as they negotiate their impossible choices, regardless of what we believe about the war itself.

There are many ways to show solidarity, and to fight for what is just, besides affirming the decisions made by an army or a government or publicly dissenting from them. We can express solidarity by investing in personal relationships, finding ways to support Israeli civil society and its many needs amidst a war, continuing to try to proliferate a Jewish voice that affirms humanity amidst so much death, and planning now for the Israel of tomorrow.

A commitment to solidarity while being circumspect about the war might also empower Diaspora Jews to help Israelis see better what we see, the carnage not fully covered in the Israeli press, and the consequence of Israel’s isolation on the rest of world Jewry. The decisions we make now could literally reshape the future of Jewish peoplehood.

And a commitment to fight for what is just right now, which also need not be limited to calling for an end to the war, should include the obligation incumbent on us to fight against the spillover effects of discrimination and violence against Palestinian citizens of Israel, vigilante violence against Palestinians in the West Bank, and the dangerous threats from extremists to “resettle” Gaza after the war.

And most of all, we can pray for peace. We pray for it, without demanding it.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

January 31, 2024

The Scandal of the Scandal of Particularity

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

In her book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard observes:

“That Christ’s incarnation occurred improbably, ridiculously, at such-and-such a time, into such-and-such a place, is referred to—with great sincerity even among believers—as “the scandal of particularity.” Well, the “scandal of particularity” is the only world that I, in particular, know. What use has eternity for light? We’re all up to our necks in this particular scandal.”

The Monty Python film, Life of Brian, makes the same wry point about particularity by noting that the crucifixion took place on Good Friday at Golgotha “around tea time.”

In this season of glory, I think of the scandal of particularity when I read the lectionary Gospel passage for the Fifth Sunday of Epiphany is Mark 1.29-39. At the top of the text, the evangelist reports that the disciples, having listened to Jesus teach in the synagogue, go with him to the home of Peter’s mother-in-law. While there, Jesus not only healed the old lady of a fever but many others of ailments and he notched a few exorcisms too.

The detail Mark leaves out— the scandalously particular note you need to be there to appreciate— is that from synagogue to the home of Peter’s mother-in-law Jesus and the disciples traveled about the distance of a pickle-ball court.

January 30, 2024

Live with Fleming Rutledge

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Here is the latest discussion of Fleming Rutledge’s new book, Epiphany: The Season of Glory. Scroll down for the Show Notes. Fleming and Dick Rutledge joined us for the conversation.

Here’s the best part of the evening:

Reflection — by Josh Retterer“I was slower to enter into the immensities of the other sacraments. What baptism means has become more and more important to me,” confesses the religious hermit/television art critic, Sister Wendy Beckett. “St. Paul is the one who understands it best so far as this mystery can ever be understood, which isn’t very far. Baptism means we are “in” Jesus, taken onto a completely new level of being. As St. Paul says, we die with Him and we rise with Him. Everything is out of our control now except that He enables us to say yes to this, to Him being our life and not ourselves.”

Immensity is the perfect word for what happens to us, dying and rising with Him is a non-trivial thing. The Light of the World, applied internally, has an expulsive effect on darkness, it’s gone. No wonder baptism is also considered a minor exorcism; that kind of candle power would blow the demons hiding in there clean out of you! In chapter 5 of Epiphany, we find Rev. Rutledge talking about the baptism of Jesus as well as what our own baptism means, via Romans. We find Paul furiously underling exactly why baptism is such a big deal, in permanent marker.

“This is a good place to address the theme of recapitulation, firmly planted in the great tradition by Irenaeus in the second century. It is founded in the story told by Paul in Romans 5. Because it is so important to Paul, he retells the story six times in six separate sentences! Here’s just one of them: As one man’s [Adam’s] trespass led to condemnation for all men, so one man’s [Jesus’] act of righteousness leads to acquittal and life for all men. (Romans 5:18) Paul then writes definitively to the Romans, “We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life” (Romans 6:4). The baptisms of believers would be victory celebrations and the church would be renewed if these biblical passages and others like them were made a standard part of every Christian’s knowledge and faith.”

Rev. Rutledge also preaches about what being “in” means for us in her collection of Romans sermons, Not Ashamed of the Gospel. As an aside, having two clergy people quote Paul, particularly from Romans, approvingly is so rare, I feel like I should play the lottery. I would have loved to hear Rev. Rutledge preach this sermon live. There is a rhythm and a passion to her words as she lists the ways Christ permeates everything about us. We not only get to witness it, but to experience God’s pleasure as He’s working in and through us. You sense she is speaking from direct experience, because she is..

“Christ, through the Holy Spirit, has already implanted himself within our hearts. His power is with us in the running, in the pressing on, in the laying hold of the prize. He is never simply standing by, watching to see how we perform; he is actually present in the actions we take on behalf of the poor, present in the reconciliation of sinners, present in the recovery from addiction, present in the congregation gathered to praise the congregation gathered to praise him and receive his mercies anew at each Eucharist. He is powerfully working in us to guarantee the future of his beloved children. Because he himself is the righteousness of God, and because he is raised from the dead and his living powerful presence is with us, the saying "Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling" has a completely different meaning "for God is at work in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure."

Yes, that verse does have a completely different meaning now. This isn’t about an abstract thought form, or angry sky god, this is the real God, one who is with us, because we are in Him. Not as if we are, or sort of like we are, it is as real as I am, as you are. Wonderfully, Chrst is even more real. Like the difference between dead and alive real. Now we are alive, as beloved children with a guaranteed future. Yes please!

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the appShow Notes:Summary

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the appShow Notes:SummaryThe conversation explores the importance of the question 'Who is Jesus?' and the need to address the Christological crisis in the church. It highlights the timidity in proclaiming Jesus as Lord and the casualness often associated with baptism. The chapters also discuss the significance of baptism as a transformative event and the need for awe and reverence in its observance. The conversation concludes with a discussion on elevating the understanding of baptism in Baptist churches and discerning a calling beyond lay ministry. In this conversation, Fleming Rutledge and Dick Wills discuss various topics related to faith and the Christian life. They touch on the impact of discovering the doctrines of grace, falling in love with Jesus, and the significance of baptism. They also explore the connections to South Africa and the meaning of apocalyptic. The conversation delves into the turning of the ages and the role of John the Baptist in heralding the coming age. They discuss apartheid as belonging to the old age and the hope of the age to come. The conversation concludes with reflections on the vocation of baptism and the support and love shared between Fleming and Dick.

TakeawaysThe question 'Who is Jesus?' is central and needs to be addressed in the church.

There is a Christological crisis in the church, with a lack of bold proclamation of Jesus as Lord.

Baptism is a transformative event and should be approached with awe and reverence.

There is a need to elevate the understanding of baptism in Baptist churches.

Discerning a calling beyond lay ministry requires deep reflection and seeking God's guidance.

Chapters00:00Introduction and Reconnecting

05:35Opening Prayer and Getting Started

08:57The Importance of the Question 'Who is Jesus?'

13:17Timidity in Proclaiming Jesus as Lord

22:32The Significance of Baptism

35:00The Need for Awe and Reverence in Baptism

38:53Elevating the Understanding of Baptism in Baptist Churches

46:24The Objectivity of Baptism and the Active Agency of God

50:37Discerning a Calling Beyond Lay Ministry

51:35Meeting Dennis and His Story

52:34Discovering the Doctrines of Grace

53:34Falling in Love with Jesus

54:04Baptism and Apocalyptic Transfer

55:03Connections to South Africa

55:31The Meaning of Apocalyptic

56:20The Turning of the Ages

57:19John the Baptist and the Coming Age

58:30Apartheid and the Old Age

58:58Children of the Apocalypse

59:16The Promise of the Age to Come

59:55The Kingdom of God

01:00:25Ash Wednesday and Confession

01:01:21The Vocation of Baptism

01:02:06Dick's Ministry and Support

01:03:38Dick's Hunger for Jesus

01:04:07Supporting Fleming's Vocation

01:05:06The Gift of Each Other

01:06:14Appreciation for Jason and the Church

January 29, 2024

God Gives a Feck

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

On the liturgical calendar, today is the Presentation of the Lord for which the assigned lectionary passage is Luke 2.21-35. While most of you will not observe the holy day in worship, you can ponder the happy mystery of the covenant with this offering:

In Martin McDonagh’s film The Banshees of Inisherin, actor Brendan Gleeson plays Colm Doherty, an amateur musician in the clutches of a crippling melancholia and existential dread. Colm lives on a a sparsely populated island off the coast of Ireland, close enough to the mainland to hear gunshots traded during the early years of “The Troubles.” Gripped by despair over the fleetingness of time and the meaninglessness of life, Doherty hopes his music somehow will justify his existence and insure that the future will remember him.

Thus Colm vows to waste no more of his precious time in the company of his kind-hearted but “dull” friend, Pádraig. Colm, literally, spites himself in order to cut off his former friend. Colm’s shocking ultimatum leads inadvertently to the death of Padraig’s last remaining companion, his pet donkey Jenny. While Colm shows no remorse over the cruel way he suddenly shunned his former pub mate, Colm does regret that his despondent tantrum killed Jenny the donkey.

Genuinely vexed, Colm confesses his transgression to a feckless priest who comes to the fictional island on Sundays in order to dispense the sacraments.

"How's the despair?" the priest asks Colm.

Colm replies it's been not so great lately.

”But you're not going to do anything about it, right?"

Colm replies that no, he's not going to do anything about it.

But the reply hangs in the air.

Later Colm confesses to Jenny’s accidental killing.

Deaf to Colm’s spiritual desolation, the priest loses patience with Colm’s contrition and coldly dismisses him, blurting out the question:

“Do you really think God gives a feck about a miniature donkey?”

Colm looks over at his confessor.

And with sincere and absolute alarm on his face, Colm replies:

“Father, I’m terrified that he doesn’t.”

Do you actually think the Almighty cares about a single creature?

On the lips of the film’s indolent priest, the question shocks. In the mouth of anyone else, the question deserves a hearing.

According to the National Zoo, there are 20,000 miniature donkeys in this country alone. The National Wildlife Federation says scientists have identified 5,400 different species of mammals; meanwhile, the World Bank estimates the global population, as of 2021, at 7.837 billion. I cannot even do the math— that’s an awful lot of people for the Lord to number every hair on every head.

Sure, God is all-knowing, all-powerful, all-everywhere.

But all-caring?

All-involved?

It’s no wonder the possibility terrifies Colm. The priest’s position makes more sense. The only downside is that what could be said of Jenny could be said of you. You might be the single creature for whom God does not care.

Do you really think the Eternal One gives a feck about a single miniature donkey— there are thousands upon thousands upon thousands of them?

It’s a good question. It’s one of the most important questions. It’s a question, I believe, that gets at the heart of our scripture text from the Gospel of Luke.

According to the Lord’s command to Abraham in the Book of Genesis, Mary and Joseph have their baby circumcised on the eighth day after his birth. In so doing, the child becomes an official participant in the people of Israel and receives his name, Yeshua— the name first given to them by the angel Gabriel.

Thenceforth, the Holy Family travels nine miles from Bethlehem to Jerusalem, up to the temple to fulfill two obligations prescribed by the Torah. First, Mary and Joseph must redeem their firstborn son. Because every firstborn child and every firstborn creature belongs to God, they needed to be redeemed from God. Clean animals, such as sheep or goats, would be sacrificed. Unclean animals, like donkeys, would be redeemed by offering a clean animal in its stead. The redemption price for a firstborn son, according to Numbers 18.16, was fixed at five shekels. It’s one of the only prescribed offerings in the Torah that’s not scaled according to wealth or poverty.

After making Jesus a participant in the people of Israel by means of circumcision, Mary and Joseph venture to the temple in Jerusalem in order to make Jesus a participant in their family. They make an offering so that God’s child might become their child. The second obligation Mary and Joseph perform in Jerusalem is purification. Bearing a son meant that Mary— and anything Mary touched— was ritually unclean for seven days. To avoid defilement from his wife, Joseph needed to immerse himself daily in the temple’s miqveh. Having given birth to a son, the Torah also forbid Mary from handling “holy things” (for example, alms for the poor or a tithe to the temple) for a period of thirty-three days. At the end of this period, Mary could come to the temple with an animal offering. As set out in Leviticus 12, the sacrifice required of a poor woman was two doves.

So thirty-three days after his birth and twenty-five days after his redemption from the Lord, Mary and Joseph journey through the massive colonnaded courtyard that marked off the Court of the Gentiles and walk up to the animal vendor stalls set up alongside the towering outer wall of the temple. They purchase two doves, walk through the Court of the Gentiles, past the low wall through which only Jews were permitted, and up the steps to the inner courts of the temple.

Taking her two doves in one arm and her month-old baby in the other arm, Mary enters the Court of Women through a side door where a Levite waited to take Mary’s offering to a priest who waited for it in the Court of Priests. At some point, as they rove from the chaotic Court of the Gentiles to the busy vendor stalls to the crowded Court of the Jews and finally to the Court of Women, Mary and Joseph, their baby and doves in tow, bump into Simeon. Not only has the Holy Spirit led Simeon to this encounter, the Holy Spirit commandeers Simeon’s lips and the old man prophesies that in their baby God is making good on his promise of consolation first given through Isaiah. That Torah did not permit Simeon to enter the Court of Women meant that Mary encountered him just before her sacrifice; in other words, Mary entered the Court of Women and made her offering with Simeon’s words still ringing in her ears that somehow she carried in her arms not just two doves and more than an ordinary baby.

Circumcision is the sign of the covenant that the Lord makes to Abram, “I will be your God and you will be my people.” Circumcision is the sign of the “covenant in your flesh.” The rituals for the redemption of a first born child and the purification of its mother are acts of fidelity to that covenant. Luke tells you five times that Mary and Joseph did everything in obedience to the Torah. Meanwhile, according to Simeon, their child is the fulfillment of that covenant.

Everything in this passage is about the covenant.Circumcision is the sign of the covenant. Redemption and purification are acts of obedience to the covenant. Jesus is God’s commitment to the covenant made flesh.

The postpartum particulars, the shekels and miqveh, doves and defilement, may strike us as strange today. So much so, we miss entirely a far stranger feature of the Bible and fail to ask a most basic question.

What kind of odd God makes a covenant?

Almost twenty years ago a sociologist at the University of Notre Dame conducted the National Survey of Youth and Religion. It was the largest and most exhaustive assessment of the religious beliefs of teenagers in the U.S. The results of the survey revealed that the vast majority of Christian youth, especially white Mainline Protestants, were incredibly vague and inarticulate about their faith. Indeed the religion these youth practice is so unrecognizable from historic Christianity the authors of the survey gave it a new and distinct name. They called it Moral Therapeutic Deism.

The basic tenets of Moral Therapeutic Deism hold that:

1) a God exists who once ordered the world but now watches over life from a far remove.

2) God wants people to be nice.

3) The central goal of life is to be happy and feel good about oneself.

4) God is not involved in the world or in my life

5) Good people go to heaven when they die.

Contrary to the myth of teenagers rebelling from the religion of their parents, the researchers at Notre Dame discovered that most of the teenagers subscribe to Moral Therapeutic Deism exactly because that is what their parents believe about God.

God is a kind of Cosmic Butler. Unseen, uninvolved. Distant and dispassionate.

In other words, the God in whom most Americans believe is not a Covenant Maker. Needless to say, the pagan deities of the first century as much as the twenty-first would not, could not, make a covenant. God is omniscient and omnipotent, transcendent and sublime, self-contained and self-sufficient, ineffable and impassible. No God worthy of the title God would deign to enter into time and make a covenant, the pagans of antiquity believed.

A covenant is a promise.

To make a promise, the promise-maker must address an other.

But to so address an other means the promise-maker is interested and invested in the other’s existence. What makes the gods God is precisely the absence of any such personal concern. For Aristotle, God is the Unmoved Mover. God doesn’t send rain when you pray for rain; God established systems whereby secondary causes may or may not bring rain. For Plato, God is simply the One. For Nietzsche, there is such an infinite qualitative difference between Creator and creature that to suggest God loves Jenny is analogous to you claiming you cherish the ant crawling under the pew at your feet. For pagans, today and in antiquity, it’s blasphemy to imagine God speaking to Abraham or wrestling with Jacob or showing Moses his backside. Pagan religion, then and now, cannot abide communication between Creator and creature; therefore, there can be no covenant. Without communication, there is no promise.

What kind of odd God makes a covenant?

A covenant is a promise addressed to an other.

To make a promise to an other, the promise-maker must have an other.

But for God to have an other to whom he can address a promise, God must be a God who creates. By contrast, the Greeks believed creation was eternal, that it had always existed. A God who makes a covenant must be a God who instigates an other other than himself.

This is why Jews point to a tiny Hebrew word in the Genesis account of creation, tov.

“And God saw that it was tov.”

Not simply good.

Tov means “good for.”

Creation is good for covenant.

God creates for the purpose of making a covenant.

As the second Book of Esdras puts it unabashedly, “It was for us that you created the world.” Believers sometimes get up on the how or the when of creation without realizing that the why of creation is the entire reason scripture bothers to proclaim the story in the first place.

As Karl Barth writes, “Creation is the outer basis of the covenant and the covenant is the inner basis of creation.”

The whole reason for light and darkness, morning and evening, sky and stars and every creeping creature upon the earth is for God to deliver the consolation of Israel in Jesus Christ. Everything is made for the baby in Mary’s arms and for us to be in him.

What kind of odd God makes a covenant?

A covenant is a promise the binds the promise-maker to an other.

To make a promise to an other, the promise-maker must acquire a shared history with the other.

But for God to inaugurate a joint history with an other, God must accept no other future than with this other. A covenant is like a wedding vow.

The promise creates a shared history and a mutual future that would not have been apart from the promise.Which means— pay attention— the promise makes God an actor in the history God authors.

This joint history and shared future is why the God of the covenant is simultaneously both the author of the history he makes with creatures and one (or more) of the dramatis personae of that history. A God who makes a covenant is not unlike Martin McDonagh, the writer and director of Banshees, showing up in scenes as one of the actors. As the theologian Robert Jenson summarizes, “Israel’s scriptures are rife with figures that are actors in the history determined by the Creator yet who turn out to be the same Creator God.” Think of the “Angel of the Lord” on Mount Moriah who stays Abraham’s hand from cutting Isaac’s throat. In the story, the Angel of the Lord turns out to be the Lord himself just as the pillar of fire that accompanies the Israelites in the wilderness is none other than the same God who met Moses in the Burning Bush, the same God who sits invisibly above the cherubim throne.

“God is in heaven and you are on earth,” Solomon waxes in the Book of Ecclesiastes. Not exactly.

In making a promise, God commits himself to being both the author of history and an actor with us within that history.

Trinity is nothing more than a shorthand way of narrating the fact that there is no other God but the God who acts within the very history he authors.

God acts as Father, God acts as Son, God acts as Holy Spirit.

The good news of great joy is that God is not abstract deity.

God is a participant in his own Providence.The true God is not immune to time; but rather, God’s faithfulness to his promise is the how of God’s eternity.

As Robert Jenson says, “God is roomy.”

God has room to accommodate all your stories within his story, casting himself as a player in all your lives.

Take Luke’s conclusion to the nativity as a case in point.

As Mary and Joseph approach the Temple in Jerusalem, the Shekhinah of the Lord dwells invisibly in the holy of holies, yet, at the same time, there’s God the Holy Spirit taxiing Simeon to the exact spot where he will encounter Mary and Joseph with words the same Spirit will lay on his lips about the child in her arms. The baby in Mary’s arms also happens to be the eternal Son of God made flesh.

In making a promise, God commits himself to being both the author of history and an actor within that history.

Because now— because of the promise— God has as much stake in your future as you do.

Therefore, the story in Luke’s Gospel of Mary and Joseph and Simeon is no different than any of our stories.

Because God is a God who makes covenant, there is no distinction between the world of the Bible and our world.

God is invisibly enthroned above and beyond, the author of your story, yes.But God is also with you, a cast member in your story, graciously—sometimes painfully— in ways seen and unseen, driving your story to the future God desires for us all.

A couple of days before Christmas, I got a request from a stranger named Bob to meet in my office. He had a large bequest he wanted to gift to the church before the end of the year, but he said he wanted to deliver it to me in person.

“If you’re really giving us that much money,” I said into the phone, “I’ll meet you in Kiev. Or, Cleveland even.”

He laughed. He thought I was joking. The next day I met Bob in my office. Sitting down and starting to tell me his story, I could see that he was already crying.

Bob told me how he was a part of the congregation here until about ten years ago. During his time at the church, Bob befriended an older widower named Ralph who came to worship with his daughter Helen.

Bob and his late wife had had three children. Two of them predeceased Ralph. All three of Ralph’s children had special needs. Helen, his only surviving child, had autism. At some point over the course of their friendship, Ralph, who had no other family or close friends, asked Bob if he would serve as the executive of his estate.

Bob accepted the role without realizing the obligation he would assume. When Ralph died, Bob became responsible for Helen.

“Her autism,” Bob explained to me, “Her autism was such that if she flushed the toilet in the middle of the night and the toilet ran for longer than twenty seconds, she thought it was busted and she’d call me.”

He doubled down to make his point, “In the middle of the night!”

And then he chuckled and wiped his eyes.

He took her to all her medical appointments and covered her errands.

“Eventually she needed more serious care,” Bob continued, “So I got her set up at a nursing facility, but she’d still call me to take care of anything she got it in her mind needed taking care of. I had no idea what I was saying yes to when I said yes, but I guess it was all part of a plan.”

When his story was finished, he held out his palms like he’d just handed something over to me and now they were empty.

He had handed something over to me.

“That’s a remarkable story,” I told him, “Thank you.”

“I don’t know that it’s all that remarkable,” he pushed back, embarrassed.

“No,” I said, “You just bore witness. You bore witness to a woman with special needs who would not have been cared for apart from a friendship made possible by the church.”

He chewed on that idea for a moment. Then he looked up at me and smiled.

“I guess the church being the Body of Christ isn’t a metaphor,” he said.“No, it can’t be a metaphor,” I said.“It can’t be a metaphor,” I didn’t add, “because God has made a covenant. God has no other choice now but to be an actor in the very Story he’s unspooling.”The name that Mary and Joseph give to their child is Yeshua.

But the name of God is Trinity.

And at the end of the day that is our only answer to the question the feckless priest asks the despairing Colm, “Do you really think God gives a feck about a miniature donkey?”

Yes, God gives a feck.

We know so because the only true God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

In fact, God so gives a feck he’s promised to show up here, for you, even you, the consolation of Israel made flesh in creatures of word and wine and bread.

January 28, 2024

A Bird With Many Branches

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

1 Kings 18.20-40

“If the Lord be God, follow him, but if Baal be God, follow him, and go to hell!”

Thus did the preacher Peter Marshall conclude his famous sermon, “Trial By Fire,” on 1 Kings 18 during Lent in 1944.

An immigrant from Scotland, Peter Marshall served for two years as the Chaplain of the United States Senate until his premature death in 1949. Prior to the position, Peter Marshall served as the pastor of the so-called President’s Church, New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington DC.

Nearly a decade earlier, on March 11, 1944, Peter Marshall was the guest preacher at St. Charles Presbyterian Church in New Orleans, Louisiana. Knowing he had the ear of many leaders in Washington, the preacher fixed upon verse twenty-one in the passage, the prophet’s question to God’s fickle, inconstant people: “How long will you go limping with two different opinions? If the Lord is God, follow him; but if Baal, then follow him.”

In his thick Scottish burr, in a city still haunted by an authoritarian demagogue, Marshall exhorted his hearers with words that ring eerily prescient:

“A time like this demands strong minds, great hearts, true faith, and ready hands — men whom the lust of office does not kill, men whom the spoils of office cannot buy, men who possess opinions and a will, men who have honor, men who will not lie, men who can stand before a demigod and damn his treacherous flatteries without winking… We need a prophet who will say to America now, “How long will you go limping between two opinions? If the Lord be God,

follow him, but if Baal be God, follow him, and go to hell!”

I don’t know how the preacher’s word landed at St. Charles Presbyterian, but when posed to its original hearers the question induced only guilt-stricken silence, “The people did not answer Elijah a word.”

Actually, the Hebrew word is hop not limp. And the word translated into English as opinion is branch.

Actually, the Hebrew word is hop not limp. And the word translated into English as opinion is branch. Like a bird hopping between two branches, hesitating to choose which branch finally to stand perch:

“How long will you go hopping between two branches? If Yahweh is God, follow him, but if Baal is God, follow him!”

However you translate it, the response is the same.

God’s people offer no reply.

Carmel means vineyard or orchard. With the Mediterranean stretched out on one side of the mountain and the Wadi Kishon unfurled on the other side and the Mount of Transfiguration rising up in the distance, the verdant Mt. Carmel was associated with fertility and abundance in Elijah’s day. The Carmel range marked the boundary between the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Tyre— Jezebel’s home. Thus, Elijah challenges the prophets of Baal on the border of Baal’s territory.

Challenges the prophets of Baal.

Interpreters typically pose this passage as a decisive contest between the God of Israel and the Canaanite Zeus, but this misses the judgment running through the Book of Kings— a judgment upon the kings.

This is not a bout between Yahweh and Baal. There is no Baal with whom the Lord could contend.The parched land has proven Baal to be a lie and his prophets to be grifters. This passage is not a contest between God and not god nor is it a competition between the prophet Elijah and the charlatans of Baal.

As has been true since Solomon, the problem in Israel are the Ahabs; in this case, the corrupt tyrant with his foreign wife. God’s people have wandered away from their covenantal vocation and have fallen into unfaithfulness not because Baal has any power over them but because Ahab does.

The rain god cannot even make it rain.

Baal wields no power over the people.

His prophets are pretenders.

It’s all a Big Lie.

The Lord’s faithful are few in number— Elijah, Obadiah, a hundred Jews hidden in caves— because Ahab has either frightened the rest of God’s people into unfaithfulness or enticed them with the power and profit promised by his patronage. As Peter Marshall put it, the silent majority are not people who can stand before a demigod and damn his treacherous flatteries.

Just so—

The confrontation at Mt. Carmel is not a contest between Yahweh and Baal.

The confrontation at Carmel is a defenestration of Ahab. It’s an unveiling— a revealing— of the Big Lie at the heart of his corrupt administration.

“How long will you go limping between two opinions?”

And the people did not answer him a word.

“To act half as children of time and half as children of eternity, brings with it entire death.” So preached F.W. Krummacher in his 1845 sermon, “Elijah and the People at Mt. Carmel.” A German Reformed pastor, Friedrich Wilhem Krummacher was the Peter Marshall of the nineteenth century. In 1853 Krummacher became the court chaplain for the Prussian King and remained in the position until his death.

In his sermon on 1 Kings 18 in 1845, Krummacher similarly fixed his focus on verse twenty-one. A century before Peter Marshall and three thousand years after the prophet Elijah first posed it, the question remained a live one to God’s people, “How long will you keep hopping from branch to branch without standing firm?”

After first describing the scene and surrounding landscape at Carmel, Krummacher preached:

“But if Elijah were now preaching amongst ourselves, surely he would not long endure to witness the double-mindedness and indecision which prevails among professed Christians…They prefer the golden calf of the lusts and honor of this world…Be therefore pilgrims and strangers decidedly; lay aside every sin, everything which would impede your progress; esteem all such things as dross and dung, that ye may enter in at the strait gate, and that the word “Eternity” may not at the last be a word of thunder to you.”

“How long will you go limping between two opinions?”

Krummacher's sermon inspired the composer Felix Mendelssohn to write the oratorio, Elijah; otherwise, the people did not answer him a word.

When the Israelites offer Elijah no reply, the Man of God commands Ahab’s prophets to put up or shut up. He orders them to sacrifice a bull and call upon Baal for fire.

So they pray.

From morning to noon and then from noon to three, they prattle and plead, “Oh Baal, answer us!” Like a bird from branch to branch, they hop about their altar. When words don’t work, they try blood, cutting themselves and smearing the altar. But, the Book of Kings reports, Baal was as silent as Ahab and all the Israelites; “there was no voice, no response, no answer.”

All the while Elijah dishes what every tyrant most hates. He mocks and ridicules them. “Speak up! Baal must be hard of hearing. Maybe he’s away from his desk or taking nap.”

Four hundred and fifty “prophets” praying to Baal.

That’s a lot of noise, a lot of prayers, a lot of blood.

Before dusk falls and after the prophets have failed, Elijah beckons all of Israel to gather closer to him on top of Mt. Carmel. Then Elijah simply calls upon the name of the Lord. This is the only instance where the Book of Kings calls Elijah a prophet.

And the Lord answers with fire.

When they witness the Lord’s mighty deed of power, like nervous birds God’s people hop to the other branch, declaring, “Yahweh is indeed God!”But, time only tells— that was not our final answer.God’s people did not long remain on that perch.

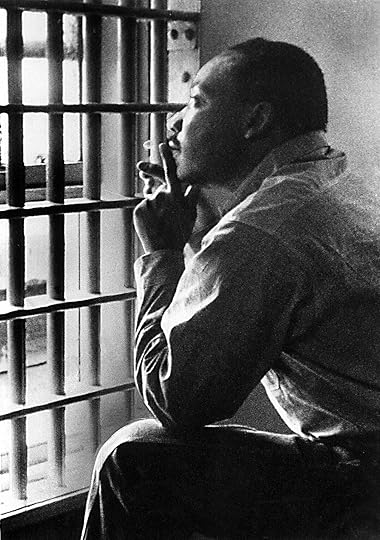

In the handwritten notes he filed in a folder marked “Sermon Notes,” the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. sketched several possibilities for preaching on 1 Kings 18. And while King did not explicitly mention Elijah in his 1963 Letter from Birmingham Jail, the prophet’s unanswered question is at the heart of King’s rebuttal to the eight liberal Christian and Jewish clergymen who had admonished him publicly to be more moderate— limping— in his activism.

“How long will you go hopping from branch to branch?”

When Will Willimon became the United Methodist bishop of the Birmingham region in 2004, he hung a framed copy of preacher King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in his episcopal office.

He writes: