Jason Micheli's Blog, page 60

November 7, 2023

(un)Like A Virgin

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

The lectionary Gospel passage for Sunday is Jesus’s parable Matthew 25:1-13 of the Wise and Foolish Virgins.

Remember:Parables are stories Jesus tells about himself.November 6, 2023

Lives of Truth

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

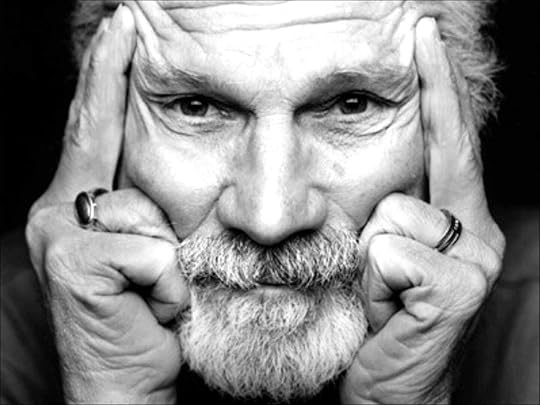

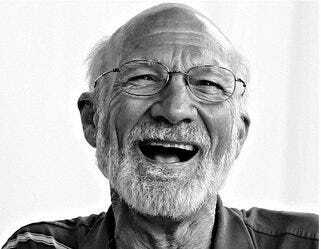

My mentor and muse, Stanley Hauerwas, shared his All Saints sermon with me and I share it here with you. I do so because, in my own life and vocation, Stanley is one of the lives of truth of which he preaches.

All Saints Sunday: Revelation 7: 9-17/Psalm 34:1-10, 22/1 John 3: 1-3/Matthew 5: 1-12

Because it is true—when all is said and done that is why we are here.

We are here because we believe when all is said and done what makes us Christians is true.That is no small thing in a time when many no longer believe truth is possible or matters.

There is the question, however, of what the “it” is that we take to be true. Because Christians are often thought to believe twenty seven impossible things before breakfast some think truth applies to those beliefs that have passed some test that is generally accepted as determining truth from that which is doubtful. Yet what we take to be true as Christians is not some collection beliefs that are generally recognized as being non-problematic…Such beliefs may have their place, but what we take to be true is a different reality.

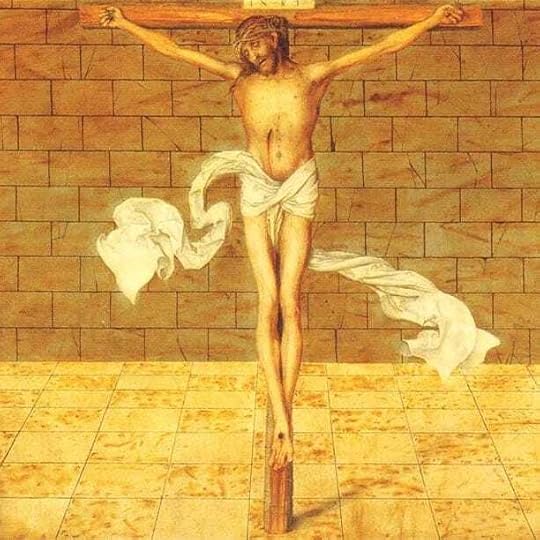

The truth that determines our lives is a person. His name is Jesus.Jesus told us that he is the very Son of God and we rightly believe that to be true. We believe that to be true, however, because he lived a life that was true to who he said he was, namely, he was the one who would be crucified, who would die, only to be raised from the grave.

It seems a bit odd to say what we believe is true is a person even if the person is Jesus. I do so, however, as a way to suggest why this day, that is All Saints, is so important for our faith. It is not an accident that we are charged to remember the saints, which we do every Wednesday at mid-week eucharist, because their lives have been made possible by the life of Jesus. Ours is a faith whose truth depends on witnesses.

Put abstractly we are a people who believe our lives only make sense in the light of a contingent fact of history.

When I lived in South Bend there was an upscale men’s clothing store interestingly enough called Gilberts. They were so sure of their standing as the best men’s clothing store in the area they had as a slogan “One man tells another.” The only problem with that slogan is they used it in their adds on TV to say how word got around about their excellence. What could they do given the competition of the clothing stores that had just come in new shopping centers.

But that is the way the Christian faith works— one person tells another.

The truth that is Jesus rides on the backs of witnesses whose lives are incoherent if Jesus is not who he says he is.In the words of Cardinal Suhard:

“To be a witness does not consist in engaging in propaganda or even in stirring people up, but in being a living mystery. It means to live in such a way that ones life would not make sense if God did not exist.”

We live, however, in a shopping center world even if the shopping center has become the internet. In general most of us want what we call true to be non-problematic and if possible certain. Or faced by the fragility of all claims of truth. many simply give up on any account of truth that would commit them to standing by what they believe or say. The result too often is a cynicism whose result for many is to produce lives that cannot be lived. They have lives that cannot be lived because the cynic cannot help but turn their doubts on themselves.

Some in a desperate attempt to find something that is free of doubt think they can take refuge in some theory to insure the truth of what they believe.

But if you need a theory to underwrite the conviction that Jesus was raised from the dead you ought to worship that theory not Jesus. That is why I began by claiming what we believe is true is Jesus. You cannot get behind Jesus to a deeper reality. He is as deep as it gets. This is serious business.If what we do here is something less than true then we are surely making a great mistake by trusting our lives to a story of a life that for many seems no more than a reassuring fable.

That is particularly the case in a time when it is assumed that people with religious convictions bear the burden of truth. Too often I fear that results in some who remain Christian justifying their being so with reasons that have little relation to the worship of a crucified messiah. I do not deny that to emphasize the significance of truth is a problematic evangelistic strategy in the world in which we find ourselves. Christianity for many centuries provided the structures that made sense of the world but that is no longer the case for many. There are no doubt many reasons for the increasing number of people who describe their religious conviction as “nones” but in the absence of any compelling claim that truth matters for being Christian we have little way to respond

And then there is the problem of tolerance. We are allowed to believe whatever we like as long as we do not expect anyone else to believe what we believe. or for me to believe what they believe.

Tolerance may be a virtue but it can play havoc with attempts to be serious about truth.There is a story about the philosopher Wittgenstein and his friend Drury that I think relevant to these matters. Wittgenstein and Drury were taking a walk in Dublin and found themselves confronted by a street preacher. This self-appointed evangelist was shouting at the few he had attracted. He was demanding that those he had gathered needed to be saved. As Wittgenstein and his friend walked away Wittgenstein observed that if the preacher believed what he said he would not have used that tone of voice.

The saints are those among us whose lives reflect the appropriate tone made possible by their worship and praise of a crucified Lord.

The saints are those among us whose lives reflect the appropriate tone made possible by their worship and praise of a crucified Lord. Their lives and deaths, particularly their deaths, testify that their lives are true. Accordingly the saints are witnesses to the One who teaches us what it means to be blessed.. For it turns out, as Rowan Williams maintains, that the saints are witnesses who establish the truthfulness of their convictions by giving evidence that turns out to be their very lives.

This is what the saints do for us. By their very lives they exemplify what it means to be overwhelmed by the truth that bears the name Jesus of Nazareth.His life unleashes lives that make possible the discovery that we are a people blessed to be surrounded by those whose lives we call true. So let us thank God for the lives of the faithful who have made Jesus known to us. In the Book of Common Prayer we find this prayer:

Almighty God, you have knit together your elect in one communion and fellowship in the mystical body of your Son Christ our Lord. Give us grace to follow your blessed saints in all virtuous and godly living, that we may come to those ineffable joys you have prepared for those who truly love you; through Jesus Christ our Lord who with you and the Holy Spirit lives and reigns, one God, in glory everlasting. Amen.

When all is said and done we are here today because it is true that Jesus is the Christ. It is here we are joined with those across time whose lives have been formed by the story of Jesus. Their stories, their lives, bless our lives making it possible to live as joyful witnesses to the One that is the truth. Amen.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 5, 2023

The Light We Cannot See

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

All Saints— Revelation 19.11-16

Last year, during Advent, after the Christmas Pageant, one of the children in the cast came up to me in the fellowship hall.

“I have a question,” she said.

“What’s your question?”

“So…Jesus is alive?”

I nodded.

She thought about it for a moment. Clearly this hadn’t been her question.

“Well, if Jesus is alive, then how come we can’t see him?”

I knelt over and leaned in towards her and I whispered, like this was a secret too special to share.

“Actually,” I said, “you can see him; in fact, you did see him just last Sunday.”

“I did?”

I nodded.

“Yes, of course,” I said, “He was that bread on the table and the cup next to it. And all of us gathered around him in praise and petition. Jesus is alive and that’s the form— one of them, anyway— his body takes now.”

She nodded.

“Is that true,” she asked.

“What if it is true?” I replied, “What would it mean?”She thought for a beat.“I guess it means there isn’t much difference between there and here.”“What do you mean?”

“That there isn’t much difference between the there where God is and here where we are. Like, we don’t have to go very far to find love.”

Someone asked me this week, “Why do we do celebrate communion every Sunday?”

“Because John Wesley so instructed us,” I answered, “People accuse me of being insufficiently Methodist but I’m more Methodist than any of you.”

“Why did John Wesley instruct us to celebrate constant communion?”

“Because the Lord Jesus joins us at the table,” I said, “He is us at the table.”

The only body of the risen Christ to which the New Testament ever refers is not an entity in heaven but the Eucharist’s loaf and cup and the church assembled around them.

“You are the body of Jesus,” 1 Corinthians implores us to remember.

And the teaching there is a proposition and not trope. “The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ?” the apostle Paul writes in the epistle, “The bread that we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread.”

Again, we are “one body” in that we do something that can equivalently be described as “sharing in the body of Christ” and partaking of “the one bread.”

“The church is his body,” Ephesians says, “the fullness of him who fills all in all.”

Scripture demands nothing less than that you reconfigure your definition of what constitutes a body.The body of the risen Lord just is those believers who are baptized into him gathered around the loaf and the cup in praise and petition.The bread that we break and the cup that we bless is, as Martin Luther insisted, the gate of heaven.

Jesus is here.

You can see God.

And if this is the gate of heaven, if Jesus is present and available to us in the bread that we break and the cup which we bless, then likewise present and available to us are all those who have died in Christ.

Thus we pray, “And so, with your people on earth and all the company of heaven, we praise your name and join their unending hymn.”

This is the gate of heaven. The Lord Jesus is here. For you.But so are all his friends, Joseph and Liz and Gary and Jeanne and John…I know some of you are just going through the motions.

But imagine if it were true.

The journalist William Dalrymple wrote a travelogue of Christians in the Middle East called From the Holy Mountain, in which he tells an anecdote about the monks at St. Anthony’s Monastery in Middle Egypt.

St. Anthony was the Christian tradition’s first hermit.

William Dalrymple visited St. Anthony’s cave and met the monk, Father Dioscuros, who told Dalrymple a story about the body of Jesus and the communion of the saints:

There is a portion of the church which awaits the Kingdom not on earth but in heaven.

“You won’t believe this”—here Fr. Dioscuros lowered his voice to a whisper. “You won’t believe this, but we had some visitors from Europe two years ago—Christians, some sort of Protestants —who said they didn’t believe in the [communion of the saints]” The monk stroked his beard, wide-eyed with disbelief.“No,” he continued. “I’m not joking. I had to take the Protestants aside and explain that we believe that St Anthony and all the fathers and mothers have not died, that they live with us, continually protecting us and looking after us. When they are needed—when we go to them at the altar—they appear and sort out our problems.”

“Can the monks see them?”

“Who? Protestants?”

“No. The deceased, the saints. . . .”

“Well, take last week for instance. The Bedouin from the desert are always bringing their sick to us for healing. Normally it is something quite simple: we let them kiss an icon, give them an aspirin and send them on their way. But last week they brought us a small girl who was possessed by a demon. We took the girl into the church, and as it was time for vespers one of the fathers went off to ring the bell for prayers. When he saw this the devil inside the girl began to cry: ‘Don’t ring the bell! Please don’t ring the bell!’ We asked him why not. ‘Because,’ replied the devil, ‘when you ring the bell it’s not just the living monks who come into the church: all the holy souls of the saints join with you too, as well as great multitudes of angels and archangels. How can I remain in the church when that happens? I’m not staying in a place like that.’ At that moment the bell began to ring, the girl shrieked and the devil left her!”

Father Dioscuros clicked his fingers: “Just like that. So you see,” he said. “That proves it.”

“Proves what?”

“That just as the church fathers taught, the separated souls are hanging out around the altar because the consecrated bread and wine of the Eucharist—the post-resurrection body of Christ—are the closest they can get, until the general resurrection, to getting their bodies back.”

The fellowship of the baptized, because it is a communion of God’s eternally, life-giving Spirit, cannot be broken by time’s discontinuities, particularly not by death.

Thus, the church is a single, active communion across time of living believers and perished saints.

The communion of the saints is a communion across time; therefore, the communion of saints includes, even, your future self and, indeed, those saints not yet born.

Register the claim—At table, around loaf and cup, we commune with people not yet born.All Saints is not the remembrance of the dead.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are alive now only in Christ— and their availability to us.

All Saints is not the remembrance of those who have departed.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are here— and their power to minister to us.

This is the logical, sequential connection in the creed between the communion of saints and the forgiveness of sins, Maximus the Confessor teaches. The forgiveness of sins is not an item of the past but ongoing present labor. Contrary to Charles Wesley’s hymn, they are not at rest. We still sin against one another, and those who are now alive only in Christ are at work, in and with the Lord, to restore all things.

Scripture claims nothing less than this when it teaches that our faith directed at the Lord Jesus is simultaneously love directed at all the saints.The claims of scripture are astonishing if we can learn not to look the other way.All Saints is not the remembrance of those who have gone.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are here.

Here— present with the Lord Jesus.

We are not alone.

You are not alone.

The saints are the light we cannot see.

Not only are we responsible for one another, there is a vaster number still who are responsible for us. As Jonathan Edwards writes, “The church in heaven and the church on earth are more one people, one city and one family, than generally is imagined.”

All Saints is not the remembrance of those who have gone.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are yet here.

And though we may not always see or hear the saints, they know us infinitely better than we know ourselves exactly because their knowledge is a participation in the Lord’s knowledge of us.

When I was a boy, during the years when my father’s disease was at its nadir and he was seldom at home and my mother worked the night shift, I had a respite of sorts at my grandparents’s home.

I walked to their house from school, and they played with me and fed me and watched game shows with me and put me to bed.

My grandmother Theresa was an Italian immigrant and, like so many, a cook.

So far as I know, my grandmother did not attend Mass.

But she did have a portrait of Pope John Paul on the wall near the kitchen.

And the bed into which she tucked me had mounted above it a frighteningly large, baroque crucifix. And she prayed.

Theresa may not have been a churchgoer, but she was a praying woman.

Every night that she put me to bed, she would smooth my hair and pray the Our Father over me and then, as a sort of benediction, she would say, “We’re here. We’re here for you.”

To paraphrase Cormac McCarthy, if my grandmother's words were not, for me, the word of God, then God never spoke.

When I was in junior high, Theresa joined what Hebrews calls the “great cloud of witnesses.” Eighteen years ago, at my ordination service, I knelt before the bishop who stood beside the loaf and the cup on the altar as the body of believers gathered around us. And as the bishop laid hands on me to consecrate me to this bewildering, ill-fitting vocation, I suddenly had this apprehension— this vision and audition— of my grandmother Theresa.

And I heard her as clearly as I heard you all earlier profess the creed.

She said to me, “We’re here. We’re here for you.”

Those who have died in the Lord are not departed.

Not only are they not gone, the Lord is not done with them.

The verse in the Book of Hebrews that immediately precedes the description of the great cloud of witnesses says, “Only together with us will the saints be made perfect.”

It’s astonishing how we read right past the astonishing claims of scripture.The saints are not gone but neither are the saints yet fully sanctified.Which is also to say, the dead who have died in the Lord are not merely alive.They are more alive than we are.The same passage in Corinthians:

When Paul gives the church instructions for celebrating the Eucharist, how does he introduce the sacrament? After all, Saul was not present at the last supper. Paul doesn’t say to the Corinthians, “As I read in the Gospel of Matthew.” Paul did not have the New Testament. Nor does Paul write, “This is what the other apostles have shared with me.” No, Paul testifies, “For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you…”

Paul learned the Eucharist, so to speak, from Saint Jesus.All Saints is not the remembrance of those who have gone.

All Saints is the celebration of those who are yet here.

We are not alone.

There is more to reality than what we can make out.

There is a reality that is deeper than the darkness we can see.In an essay entitled “What If It Were True?” Robert Jenson writes:

“There is a reason for our skittishness with the gospel’s truth claims…So soon as we pose the question, “What indeed if it were true?” about any ordinary proposition of the faith, consequences begin to show themselves that go beyond anything we dare to believe…The most Sunday-school- platitudinous of Christian claims say, ‘Jesus loves me’ contains cognitive explosives we fear will indeed blow our minds…

Let me give a prolegomenal instance. We sometimes join our daughter’s family for the main Sunday Eucharist at New York’s cathedral of St. John the Divine. Besides seeing our family, we go there because what happens of a Sunday morning often makes an occasion within which we can credit biblical stuff that stumps us in other contexts. For our time’s sake I will stick to what the cathedral’s organist, the amazing Dorothy Pappadokos, does. While her French-style improvisations are shaking the stones of the building, and my stony heart, when climax upon climax each improbably eclipses its predecessor, I am able to sustain the notion that all God’s various holy ones are gathered there with us, that in fact we are praising God, as the liturgy of my church has it, “with angels and archangels and all the company of heaven,” that if only we could see what is actually there, we would see the mighty thrones and dominions and Mary and Paul and Olaf and my father-in-law and so forth around us in the cavernous spaces.

But sitting in front of my computer to write for publication, I chicken out, and begin looking for ways to pare down the proposition [according to] modernity’s prejudices…And of course it is a mind-bending exercise to consider in what mode dead believers make one living company with living ones, but do they or don’t they? Is Papa Rockne there for our Eucharist or is he not?” If we say yes, then we must repent of all our assumptions about what constitutes the “real world.”

War in Israel, fear amongst Jews, grieving in Gaza, despair in Ukraine, dysfunction in Washington, a lethargic pace of change in the UMC, a burning planet, your breaking marriage, the Big Lie— nevertheless; there is a reality afoot that is deeper than the darkness we can perceive.

There is light we cannot see.

This is the central, abiding announcement not just of this passage but of the entire Book of Revelation. Here in chapter nineteen, John simply sees what we say in the second article of the creed about Jesus sitting at the right hand of the Father. John sees Jesus not as the Son of Man from Revelation 1 or Jesus as the slain Lamb from Revelation 5.

John sees the Lamb is a Lion.The Pale Rider is Christ the King.More to the point, the array of names in chapter nineteen (Faithful and True, Word of God, A Name No One Knows But Himself) is but an indication that the Christ who is King is none other than The Name— HaShem— who encounters Moses in a bush that was ablaze but not consumed by it.

Jesus of Nazareth is the God of the exodus.This just is what John sees.And Jesus is judging with justice.He is fighting for righteousness.And he is so right now, the Spirit shows John.That is, no matter what the headlines say, no matter what your eyes can see, no matter what your faith can perceive, the earth’s truer reality is that the Lord Jesus is King.

In this regard, it makes all the difference that chapter nineteen comes before chapter twenty. The Spirit shows the prophet the Lordship of Christ over the earth not as the product of evil’s demise but as the precursor to it. The Last Battle with Satan does not come until the end of chapter twenty but already in chapter nineteen Christ is King.

There is a reality afoot that is deeper than the darkness we can see.

Jesus is Lord.

And, as surely as I heard my grandmother, the Lord Jesus and all the company of heaven are speaking to us, “We’re here. We’re all here.”

Just last Sunday, a friend of mine, a Christian who lives in Northern Israel, emailed me to say, “My mother and father died ten years ago. Yesterday they appeared to me in my dream and they told me to tell you that they’re praying for you. They said your name, Jason. How on earth do they know you unless it is all true?”

She underlined that last clause.

Once you ask Jenson’s question, “What if it were true?” once you give Christians permission for their Christianity to be weird, you hear stories like this all the time.

Stories like this story a former parishioner sent me:

“Almost thirty years ago, our son was a teenager. He was troubled. We were able to get him registered in a prep school in New England. But during orientation, he ran away into the streets of Portland and was missing for days. Both my wife and I were worried sick had been praying that he would be okay. On the third day, I had been listening to religious music in my car, and there in my vehicle, in the dark and in silence, I heard my son’s voice say— I heard my future son’s self say, “Everything is going to be ok.” Those six little words from beyond what we can see pulled us through an awful time.”

Nothing that is possible can save us.

Once you ask Jenson’s question, “What if it were true?” once you allow Christianity to be weird, you can discover a reason for actual hope.

In that same essay, Jenson writes:

“It makes a difference. What do we think we inhabit? A machine of some sort? If so, we are victims of an illusion. What we really inhabit is rather a drama, the drama of Israel’s God…

It makes a difference. I do not know if our culture can be rescued from the superstition that recognizes only sub-personal forces as finally real.

If it cannot be rescued from that illusion, we will, for but one matter, continue so to present reality to students in the schools as to persuade them of their own meaninglessness and of the inconsequence of all their actions. I acknowledge that left to myself, I would despair. But since we are not left to ourselves. who knows? The church, anyway, must fight in all the ways she can against the realization of the Clockwork Orange also in her own life.”

All Saints is a way we fight against the Clockwork Orange. All Saints is a way we fight against the resignation that only what we can see is real. Allow me to throw a punch in the fight.

In the Book of Malachi, Jesus speaks to the prophet, telling him to exhort God’s people to remember the commandments given to Moses. But— Jesus cautions Malachi— even if the people do keep the law, I am sending Elijah to convert the hearts of generations.

Elijah is but one of the saints.

In other words— and, again, it’s weird— Jesus dispatches the saints from the Last Future back through time to turn hearts towards him.

Which means nothing less than…

My grandmother did not say, “We’re here. We’re here for you,” merely to steady me in the midst of a turbulent childhood.Rather, Saint Theresa gave those words to my grandmother so that I would apprehend them at my ordination.Still further, Saint Theresa gave those words to my grandmother to speak over me as a boy; so that, today I could relay them to you and with them, through them, you would know that everything is going to be okay.

No matter how dark the world may appear, the light is winning.

What if it were true?

For starters, there would be no reason you would not rush. Run straightaway to the table. With God, there is no here and there. There is only ever here. Therefore, you don’t have to go very far to find love.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 4, 2023

Nude Faith

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

First up—

I TOTALLY forgot I’d set up the Founding Member Subscription Offer so that you’d receive a signed copy of my new book. Those will go out this week! In other words, now’s your chance to subscribe and become a Founding Member and you too will get a copy of A Quid Without Any Quo.

We’re doing a short series of sessions on the five Solas that served as a summary slogan for the Reformation: sola scriptura (Scripture alone), solus Christus (Christ alone), sola fide (faith alone), sola gratia (grace alone), and soli Deo gloria (glory to God alone).

Session #1 on Sola Scripture is here.

On the critical insight in the Reformers’s stress on faith alone apart from works:

The Reformers’ fundamental insight was that the radical question about ourselves can accept as answer only an unconditional affirmation of the value of our life.

An affirmation which sets a condition of any sort whatever, which in any way stipulates “you are good and worthy if you do/are such-and-such” only directs me back to that very self that is the problem.The point made by “without works” is: any affirmation of our life which says “if you do/are …” is not merely a poor answer to the Reformation question about justification, it is no sort of answer to the question being asked; for what is being asked is whether it is worth doing or being anything at all.

We can already see why “justification without works” is a doctrine by which the church stands or falls; in times of meaning-crisis, preaching and teaching which disobeys this rule is not merely inadequate in certain respects, it speaks altogether past any possible issue. Perhaps we can also begin to see why the doctrine might be more relevant to our own time than its desuetude in the church would make it seem.

The Reformation discovery was that the message about Jesus, told without the medieval past tense, is an affirmative answer to the radical question, and so was so intended by its original speakers. If the gospel is allowed the present tense, if it is allowed to invade the previous reserve of “cooperation,” it says:

The Crucified lives for you. This affirmation is unconditional, for it is in the name of one who already has death behind him, and whose love can therefore by stopped by nothing.As Luther usually put it, Jesus died in order that his will to give himself to us might be a “last will and testament,” and so be subject to no further challenges.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 3, 2023

The Shape of Anglican Theology: Faith Seeking Wisdom

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Here is a conversation I shared with Scott MacDougall about his new book, The Shape of Anglican Theology: Faith Seeking Wisdom. Scott also helped us place John Wesley within the Anglican theological tradition and offered a helpful corrective to the many misapplications of the “Wesleyan Quadrilateral.”

Here is the abstract for the book:

Beginning with a treatment of the ways in which Anglican theology is and is not distinct from other types of Christian theology, the theological features that mark the general boundaries of Anglican theologizing are described before considering a set of eight interconnected characteristics that provide Anglican theology with its distinctive profile.

It is argued that, by setting its boundaries as widely as possible and requiring subscription to specific theological propositions as little as possible, Anglican theology is in essence a wisdom theology that seeks to build the capacity for faithful Christian discernment in belief and practice.

Scott, Ph.D. (Fordham University, 2014), is Associate Professor of Theology at Church Divinity School of the Pacific, Berkeley, California. He is Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Anglican Theological Review, and Theologian to the House of Deputies of the Episcopal Church.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 2, 2023

All Saints: The Courage to Make Others Suffer for Our Convictions

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

All Saints

When I was a Master’s student at Princeton, I had a number of side hustles to fund my bed and board. In addition to serving as a teaching assistant for the homiletics professor and working as the assistant director for the after-school program at Princeton Junior School, I also fell into a lucky gig as a waiter at the weekly faculty lunch.

Not only did it pay better by the hour than my other gigs, it quite profoundly changed my life and forever altered the shape of my ministry.

I remember at one of those lunches early in the fall semester— around the time when I was considering dropping out of seminary due to how out of place I felt— Professor Max Stackhouse held forth over gray beef tips and over-sauteed squash about some “reckless” and “profane” theologian at Duke named Stanley Hauerwas.

If I’d been honest in narrating my call story to the ecclesial bureaucrats during the ordination process, I would’ve told them this meal was nearly as consequential to me as the Last Supper. To the bemusement of some and the alarmed agreement of others, Professor Stackhouse worked himself up into a red-faced lather about this “sectarian tribalist” named Stanley something or other.

This was not long after September 11, 2001, and Dr. Stackhouse was irate that this Stanley person had the gall to insist that it was now incumbent upon Christians in America to separate the American “We” from the Christian “We.” “Christians in America,” this Stanley person had apparently asserted, “now needed to live in manner that bore witness to fact that the date that changed the world was not 9/11 but Good Friday, 33 AD.”

By the time I served his dessert, the vein in Dr. Stackhouse’s forehead was throbbing. I leaned over his shoulder to fetch his dirty plate just as he griped, “Hauerwas’ arguments are even more irresponsible and inappropriate than the four-letter words and off-color humor with which he makes them.”

Even though I’d gone to UVA for my undergraduate work and had been taught by many of Stanley Hauerwas’ students, classmates, and colleagues, I’d enrolled at Princeton unaware of anyone named Stanley Hauerwas.

But the Law, St. Paul warns, only increases the trespass, and I’d just heard Stanley Hauerwas condemned as being both radical and vulgar. So naturally, I quickly concluded that anyone who could arouse such animus and consternation at a normally tight-sphinctered faculty lunch was certainly someone worth my reading.

As soon as I washed the dishes, I headed over to the Princeton library and checked out a book called A Community of Character along with a set of audio cassettes, lectures delivered by this Stanley person entitled Discipleship as Craft. And because modesty has never been a virtue I possess, I had the gumption to look up the email address of this Stanley Hauerwas person and let him know I had begun apprenticing myself under his work.

To my surprise, at the crack of dawn the next morning, he wrote back to me:

“Dear Jason, I’m so pleased you’ve happened upon my work, even if inadvertently. There may be hope for Princeton yet! Please tell Max he encouraged you to dive deeply into my work, and then write back to tell me how he reacted. While I’m pleased to have you as an apprentice, be warned, Jason. I tell my students at the beginning of every course that I have no intention to teach them in a manner invites them to think for themselves. Rather, my goal is to make my students think just like me. That is, you don’t have a mind worth making up until your mind has been shaped by me. Indeed, to so teach shocks our modern democratic sensibilities; however, to teach in any other fashion is a cowardice the Church mustn’t permit if we believe it’s true that Jesus Christ is Lord.

Your (New) Friend,

Stan”

“Be imitators of me!” the Apostle Paul has the temerity to exhort the church at Philippi, “Become as I am!” Talk about the gall, passing out to the congregation his very own WWPD bracelets “What Would Paul Do?” Paul says nothing less offensive than, “To imitate me is to imitate Christ Jesus our Lord.” I mean, really now— most of us are hesitant to pray in front of other people.

The early Church was no less demanding in their expectations than Paul. According to the historian Alan Kreider in his book, The Patient Ferment of the Early Church, in the first few centuries of the faith the worship service was not the entry point for newcomers into the Church. Corporate worship was instead the final threshold.

Worship was closed to outsiders until after they’d first undergone rigorous catechesis and baptism. Indeed, the first Christians didn’t even do what would be called “evangelism.” In addition, the early Church made baptism extraordinarily strict and selective, rejecting as many catechumens as they accepted. You see, the Church wanted to insure that anyone who bore the name of Jesus Christ would bear faithful witness to Christ.

The first Christians made faithfulness rather than friendliness their priority, and the ancient Church grew, Alan Kreider shows, by being a community capable of saying to the world, “Imitate us! To like we are is to become Christ!”

Recall as well that the early church did not have what we now have, the New Testament. The saints were their scripture.We simply cannot avoid that Paul could and should call attention to himself, because in doing so he believed he was calling attention to Christ.

The Holy Spirit never alights on anything, but bodies.

Accordingly, Paul would have us realize that we must finally reflect Christ’s life to one another if we are to know Christ at all. Ours never stops being an incarnational faith. Jesus is not a principle or an idea. Jesus is not an eternal possibility always available to all persons if they but make use of their experience. Jesus is only available to people bodily— through people whose lives have been touched by Christ and his Holy Spirit and so gospel another person.

As much as we might prefer the lie that faith is intelligible apart from imitation, the liturgical calendar this week reminds us that the Church is necessarily a performative community.That God has raised the crucified Jesus from the dead and made him Lord is a truth claim that cannot be proven through apologetics. It can only be known through exemplification. Embodiment.

The Gospel is a story that cannot simply be told. It must be enacted.No scientific investigation can prove that Jesus is Lord. No philosophical theory can corroborate his resurrection. No social science research can teach someone how to love their neighbor. To know what it means to confess Jesus as Lord requires that someone live a life under Jesus’ Lordship, which also means you are not the arbiter of whether or not you are living a life in line with the Lordship of Christ.

It doesn’t matter when you invited him into your heart; you are not arbiter of whether or not you are living a life in line with his Lordship. As Jesus warned, “Not everyone who says to me, 'Lord, Lord,' will. enter into the Kingdom of Heaven…” You are not the arbiter. The lives of the saints are the arbiter. The saints are those who embody how to live with the intentions that the story of Jesus demands of the whole Church.

Demands.

If we’re honest with ourselves, we resist Paul’s emphasis on imitation not because it strikes us an example of Paul’s alleged hubris, but because it strikes against our own lack of nerve.

A couple of summers ago, when our intern, David King, preached his first few sermons, a number of you commented on your way out the door, “David preaches just like you!” To my surprise, my immediate reaction to such comments was to rebut them, to dismiss the likeness and to reaffirm the importance for preachers to find their own way and discover their own voice in the pulpit.

I’ve known David since he was six years old, so it’s not unusual that he would preach like me.

Still, I did my best to shake my head at any who understood David as imitating me. If that were the case, then suddenly I have a responsibility to David— and possibly others— that I didn’t choose.

Not to mention, to discover that someone else might be imitating you, your example, is suddenly to wonder if you’re prepared to be exposed to the discerning glare of an apprentice.

What if they find that you’re doing it all wrong, or learn that you are not who you pretend to be?

And what if, I thought, David’s imitation of me led him into ministry? Being a preacher is a little like being nibbled to death by ducks, what if he followed me into an endeavor that eventually did him harm or gave him not the joy he had expected? What if one day he holds me liable for his disappointment, or his frustration, or his meager pension?

Stanley was right all those years ago.What we couch as modesty and respect is cowardice.“There are many paths to God— we’re all on a journey to the same destination.” “Who am I to say what’s right?” “Faith is a private matter, I want you to make up your mind for yourself.” “ I’m letting my kids choose their religion for themselves.”

We’re reluctant to take our convictions so seriously that others might take them seriously because, of course, we are not prepared to make others suffer for of our convictions. It’s this lack of nerve that produces a nonsensical statement such as, “I believe Jesus Christ is Lord, but that’s just my personal opinion.”

Nico Smith was a South African Afrikaner minister, a prominent opponent of apartheid, and a professor of theology at the University of Stellenbosch.

Eventually in the mid-1960’s, Nico Smith began aggressively challenging apartheid in his classes, which provoked his superiors who wanted him to give his students the theological material without shaping them in a particular direction. “Teach theory, not conclusions,” they ordered.

Smith didn’t heed them. He also joined public protests against the government's bulldozing of squatter shacks in Cape Town.

Summoned before a church commission to justify himself, Smith decided to resign his professorship. Instead, he left the pro-apartheid Dutch Reformed Church and joined its colored branch. In 1982 he undermined the apartheid regime by preaching in an area of Pretoria designated for non-whites only. And in 1985, he and wife moved to that community to live.

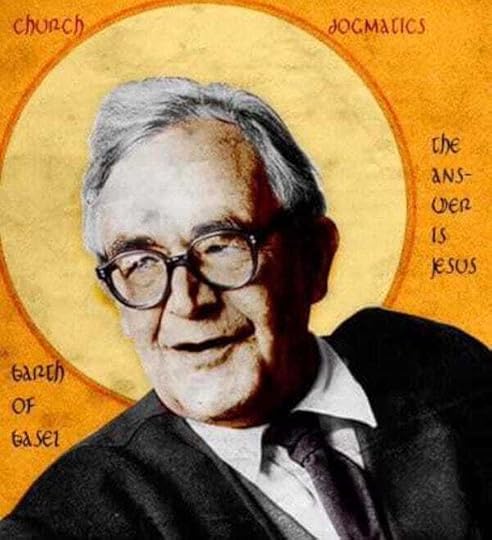

Nico Smith attributed his peculiar and dangerous witness to an encounter he had with the theologian Karl Barth in the early 1960’s.

A staunch supporter of apartheid at the time, Smith attended a lecture by Barth and the two spoke afterward. Smith describes the key moment of the exchange as follows:

“Barth then looked at me and said: “May I ask you a personal question before you leave? Are you free to preach the Gospel in South Africa?” “Of course,” I replied, “I’m completely free as we have freedom of religion in our country.”

Barth immediately responded by saying that that was not the type of freedom he had in mind.

He wanted to know whether I, if I came across things in the Bible that were not in accordance with what my friends and family believed, would be free to preach about such things? Or would I temper the demands of obedience?

I was once again embarrassed and said I really did not know as I had never yet had such an experience.

Barth then leaned a little forward in his chair, and said, “But you, it may become even more difficult. You may discover things in the Bible that are contrary to what your country is doing. Will you be free to preach about such issues?”

Once again, I had to say, “I really did not know.”

Barth then just said, “It’s OK, you may go.”

In the tram back to the city center, I thought about Barth’s questioning of me, and I said to myself, “I’m sure Barth thinks we in South Africa are Nazis and he wanted to warn me against apartheid. Barth had had the courage of his convictions, the courage to make me suffer, potentially, for his convictions. With his gentle questioning and in so many words, he had said, “Imitate me!”

The world is quite right to judge Christianity by the lives it produces. Judging from the polls, this is going to be a long-term problem for the church (in America).

There is no gaslighting our way out of the truth that Christian discipleship is utterly dependent on our ability to identify examples.While it’s true that the Bible says we are all saints right now, that Jesus is our righteousness, that he is both our justification and our sanctification, it’s also true that the reality of who we are in Jesus Christ is exemplified by some better than others.

That’s the embarrassing, unspoken truth when we light these candles for the dead every All Saints Day.

The Church is not a democracy.There are some who bear a better witness than others.But this is good news! This is good news because the nature of discipleship didn’t change after the Cross. It’s always been a Master-Apprentice relationship. Discipleship is not about knowing or doing certain things you would not know or do if you did not know Christ. Discipleship is about being transformed, and transformation is not the result of facts, but the result of teaching. It’s the product of formation, not information.

Our fellowship as Christians, therefore, is a moral practice. We are not friends in Christ as an end unto itself. Most of you might not choose me as your friend. But, we are friends brought together by the Living God for the common activity of trying to give a visible witness to the Lordship of Jesus.

And this is no easy or uncontested task.

That our citizenship is in heaven means that the salvation brought in Jesus Christ has made us citizens of a time and space that is in tension with all other forms of citizenship. It’s exactly through the process of conforming ourselves to the Cross, it’s through the process of conforming ourselves to the Lordship of Christ, it’s through the process of suffering the consequences of living as though God really has raised Jesus from the dead— it’s through that process of enactment and embodiment and exemplification of our ultimate citizenship that the Living God transforms us into the Body of his glory.

The pursuit of happiness is not necessarily the pursuit of the good. We need to be shown the good. We need witnesses. Thus, our hope for the world rests not in what you do with your ballot on Tuesday. Our hope for the world rests in what we remember this week: That the Living God is capable of raising up a peculiar people, citizens of heaven, who embody how to live with the intentions that the story of Jesus demands.

When I first became a pastor, I was extraordinarily uncomfortable and embarrassed whenever a little child would come forward for the children’s sermon and, seeing my robe and beard, confuse me with Jesus. Today I believe the possibility of such a likeness is not only a part of God’s good humor, I believe it is the way in which God has elected “to make all things subject to himself.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

November 1, 2023

The Mystery of Grace in Our Most Fearful Hours

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

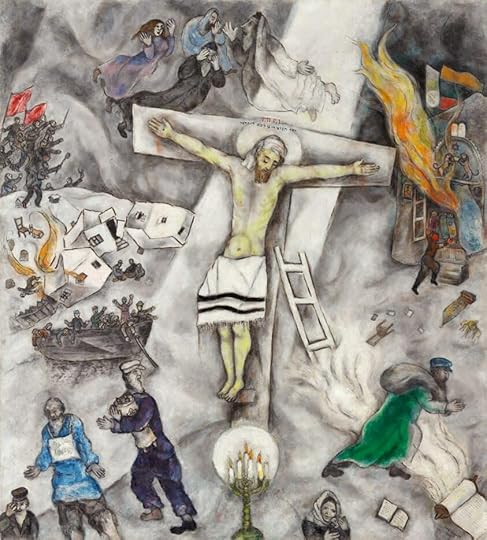

Here is my most recent conversation with my new friend Rabbi Joseph Edelheit. We talked about fear, the dangerous idioms in our cultural ether, the antisemitism lingering in Christian liturgy, and how Jews understand death, sanctity, and the promise of the eschaton.

Here is the benediction Rabbi Joseph offers at the end for All Saints Day:

On this All Saints Day, we remember those whose lives are called to religious service. There are many different faiths that these human beings have served. There are many today, unnamed, unknown, who continue to serve the mystery of grace.

May they sustain us in our most fearful hours. And may those who are still held hostage know freedom so their families might finally know peace. Amen.

For those of you who missed it, HERE is the first conversation Johanna and I had with Rabbi Joseph.

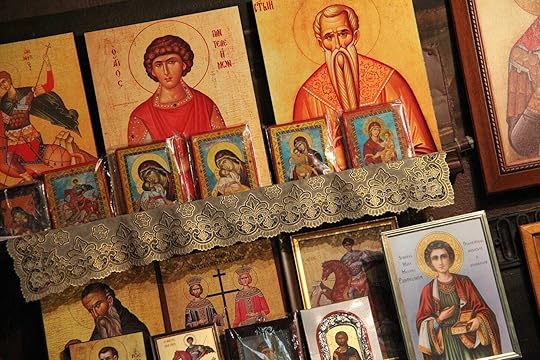

If you have questions for Rabbi Joseph for future conversations, leave in the comments or shoot me an email.The image above is “White Crucifixion” by the Jewish artist Marc Chagall, whom Rabbi Joseph referenced in our first conversation.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

October 31, 2023

It'll All Come Round Right

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

The piece today is from friend and reader, Dr. Ken Jones, a chapel sermon at Grandview University in Iowa.

Grace and peace to you, my friends, from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

In a way, All Saints Day is a day to consider our deepest losses and what God promises to do about them. The game of grief and loss is a game of percentages. I think it’s a game that far too few college professors are aware of. We don’t realize how deeply our students' lives are steeped in the dark brew of grief and loss. We professors can joke with one another about how the rate of students reporting the death of a grandparent seems to go up as we near the end of the semester and more work comes due and the stakes get higher and room to breathe gets more desperate.

But the reality of grief and loss is much more serious and more prevalent than tired students using a fictional grandparent’s death and imaginary funeral as a way to get out of school work.

Kenneth Doka, whose work my students encounter in “Death and Dying,” gives us some interesting numbers. He cites research that shows that, on average, in any group of people around twenty percent are actively grieving the death of a loved one. [Pick out one in five.] In a class of 25 students, that’s five people who have some kind of sorrow they’re carrying, that they’re contending with (often invisibly and unmentioned), along with every other demand laid on them by professors, coaches, advisors, parents, bosses, and the Iowa state legislature, not to mention God.

I imagine the classroom would feel more humane and the world would feel more kind if we kept that percentage in mind.

But Doka goes on to say that grief and loss are much bigger than we initially imagine. If we consider disenfranchised grief, those losses and deaths that aren’t regarded with such respect or given such room, then it’s even more pervasive. People with disenfranchised grief experience things like a relationship breaking up, a crush that’s just not gonna be fruitful, an athletic injury and weeks of PT, a D on a test you studied all night for, the death of your childhood pet, not getting a hoped for spot in a dance team routine, the ongoing loss of your parents divorce, a learning disability or physical disability, a dunning notice from the business office, or too-frequent empty cupboards, empty gas tank, and empty bank account.

All this is real grief and loss.

At any given time and in any group of people, 80 percent of us have it bubbling that same dark brew under the surface.

The other day I was talking to a group of students about what’s going on in the world, with the terrorist attack on innocent Israelis, the inability of Congress to function, the seemingly daily reports of mass shootings, including the most recent one that left 18 dead in Maine.

I asked them if they feel hopeful about life. They all shook their heads.Not one could say they believed the future would be brighter. That’s a sign of chronic grief that comes from living in a world of seemingly unsolvable, intractable problems.This is where Jesus’ promise breaks in.God is no god who merely observes us creatures dispassionately from afar. Jesus is God-with-us, Immanuel, who has so fully entered into human life that he knows our hopelessness, our griefs, our sorrow and pain intimately. At one point he sees Jerusalem and weeps over the city. The promise we heard from John’s gospel is aimed squarely at the painful core we know inside us, at even the most private, most shameful, most don’t-tell-anyone truth you have tucked away for self-protection.

Jesus declares, “If I’m raised up, I will raise all with me.”

He’s raised up from the water at his baptism. He’s raised to glowing form in his Transfiguration on the mountain. Those things are true, but the most important place he’s raised is on a cross in his suffering and death. That means that you are not alone in your experience of loss. It’s what he takes with him to Golgotha and to the tomb, tucked into the spear wound in his side. His wound is bigger on the inside and has room for every sorrow you carry, for all your not-good-enoughs, for every one of your questions, and, yes, even for your fictional dying grandma.

The good news is that every bit of brokenness from the foundation of the world is also right there in him when he’s raised from the dead and ascends to God in heaven.

That includes every death, loss, grief, demonic force, dire weapon, and hell itself.

He claims it all as his own so that, as the Shaker hymn puts it, it’ll all come round right.It’s all raised.

That means that, whatever your grief and loss, it will end. Whatever relationship is broken will be mended. Whomever you have lost will be joined to you again. For the cross and resurrection have made it sure.

When Jesus promises you’ll be raised up, too, it’s not something to wait for. It’s already a done deal. You can count on it.Wherever you land on the divide of percentages in this life, you are 100 percent lifted up in him. As we name those who’ve died in this community over the last year, we can also picture them emerging into God’s promised new eternal life of freedom and joy. We can see them turn back and beckon to us in witness, saying “It’s all good. Keep living. Keep hoping. We’ll see you soon.”

Amen.

October 30, 2023

Can We Pray to the Saints?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

All Saints

The door from this life to the life to come isn’t just narrow.

It’s thin.

In an essay for First Things, my former teacher, David Bentley Hart, reflected on his childhood friends Angela and Jacob. Fast friends through their teenage years, their contact became intermittent as the three went their separate ways for university. Two years after their last get together Angela was killed when a drunk driver struck her car in an intersection; she was alive for several hours after the collision, but never regained consciousness. Hart writes,

“I learned of her death three days after from Jacob. I won’t bother to say how the news affected me, but I will remark that I had had what in retrospect seemed to have been a premonition of it. On the night of her death, Angela had suddenly, for no discernible reason, come into my mind, attended by an inexplicable sense of aching melancholy, which at the time I simply took for acute nostalgia. Jacob, though, had had something that seemed like much more than a premonition.

On the night of Angela’s accident, apparently during the hours when she was lying in the hospital unconscious but still breathing, he had had a particularly vivid dream in which she and he had spoken to one another in a strange house that, after the fashion of dreams, was also somehow a garden. Their conversation, which had been pervasively sad, concerned her imminent departure for somewhere far away; and it seemed to Jacob that it was understood between them—in that way in which, in dreams, many unspoken things seem simply to be presumed—that she was leaving on a journey from which she would never return. She told him, he recalled, that she had come only to say good-bye.

Now, these things—my vague intuitions, Jacob’s haunting dream—may have been merely coincidences; but, frankly, I can’t make myself believe that the universe is quite large enough to accommodate coincidences of that kind.

What was most extraordinary about our experiences, however, is that they were not that extraordinary at all. That is, it is rather astonishing how common these encounters with the uncanny really are. You may not recall any yourself, but it is quite likely that you need only ask around among your acquaintances to discover someone who does. I myself have had at least two others, one utterly trivial, one of the most crucial importance, and both together sufficient to convince me that consciousness is not moored to the present moment or local space in quite the ame way that the body is.”

The door from this life to life everlasting is narrow. Of course its narrow. It excludes every last one of your good works. But the door from this life to the life to come— it isn’t just narrow.

It’s thin.

We’re just too thick to recognize it most of the time.

October 29, 2023

To Be Certain of the Dawn

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers.

Revelation 19.1-10

A little over four years ago, a Dallas patrol officer entered the apartment of a twenty-six year old accountant and fatally shot the unarmed man. The police officer, Amber Guyger, claimed she’d entered Botham Jean’s apartment by mistake. Thinking it her own apartment, she believed him to be a burglar.

He had been sitting on the sofa eating ice cream.

The shooting ignited a nationwide feeding frenzy about police corruption and institutional bias. But even more so than the transgression, the news of the absolution that followed both captivated and confused the country.

In the fall of 2019, a Dallas jury found Amber Guyger guilty of murder, and Judge Tammy Kemp sentenced her to ten years in prison.

The trial was over. Justice had been served. Punishment had been meted out. Yet this judge was not done.

Or, as one observer in the courtroom commented, “It was like she had only just begun her work.” First, she invited Brandt Jean to speak to the woman who had murdered his brother. “I don’t want to say twice or for the hundredth time how much you’ve taken from us. I think you know that,” Brandt Jean said, “But I just…I hope you go to God with all the guilt, all the bad things you may have done in the past. … If you truly are sorry, I speak for myself, I forgive you. If you go to God and ask him, he will forgive you.” The African American judge, reporters noticed, wept as Brandt Jean spoke of forgiveness. After speaking with and hugging the victim’s parents, Tammy Kemp returned from her judge’s chamber to the courtroom with her personal Bible in hand. She gifted it to the convicted officer and pointed to John 3:16, “For God so loved the world…” Later that day, Brandt Jean posted on his Facebook Page, “Whenever you open the Bible, the Accuser— that is, the Devil— gets a headache.”

Receiving this judge’s personal Bible, Amber Guyger reached out her arms to the judge. The judge, still in her black robe and pearled necklace, wrapped her in a merciful embrace. “It was like she was sharing in the woman’s guilt and anguish,” said another observer in the courtroom.

The reactions to Brandt Jean’s absolution of his brother’s murderer, the reactions to Judge Tammy Kemp’s act of compassion— the reactions were so swift and so divergent and so dependent on one’s place in society, one’s privilege relative to another and one’s political perspective that, as one legal expert from Stanford told a reporter, “It feels as though we are actually the ones on trial not the accused.”

Many Christians celebrated the display of forgiveness, “This is Christianity,” they said. “This is what the world needs.”Others, however, themselves also Christians, refused to celebrate the display of forgiveness as somehow a summation of the gospel.The theologian J. Kameron Carter, for one, questioned it, writing:

"The verdict on the police officer in Dallas of 10 years in prison plus the show of grace and forgiveness by the brother of the murdered victim, just like after the massacre at Emanuel AME, requires that we ask some hard questions: What if “grace” and “forgiveness,” and their compulsory racialized performance in this society, are part of the antiblack world? What if the sacredness of “grace” and “forgiveness” precisely helps keep in place the structures that murder us?”

Put more succinctly, Carter insists that grace, if it is truly God’s grace, must accomplish more than mere forgiveness.

Grace, if it is truly God’s grace, must accomplish more than mere forgiveness.

Exactly because God’s love is God’s justice, Christianity does not envision God’s forgiveness as the triumph of mercy over justice.Rather, Christianity envisions God’s forgiveness as the triumph of God’s justice in mercy.While we were yet sinners, the God who is human died for the ungodly— yes. But also, the Lord Jesus promises that those who mourn will be comforted just as those who hunger and thirst for righteousness will be filled. One promise is not to the exclusion of the other promise. These twin promises are as true today in Israel and Gaza, in Moscow and Ukraine and Maine, as they were in that Dallas courtroom four years ago.

The hope of the gospel is not mercy instead of justice.The hope of the gospel is justice in mercy.In other words, the hope of the gospel includes the promise of hell. The process of hell is constitutive of God’s heaven.

The promise of heaven is unintelligible apart from the process of hell.That is, God is heaven and God is hell.

In popular imagination, the last book of the Bible, the Unveiling to John, is likely the scripture most often associated with the doctrine of hell, but heretofore I have avoided addressing it directly.

I have bided my time.

I have been waiting for this passage because only when you appreciate how the scriptures conceive of the character of salvation will you understand why the ancient church fathers and mothers— who complied the documents we call the New Testament— insisted on the reality of God’s hell.

Only when you understand the kind of salvation the scriptures anticipate will you understand why the fathers insisted on the reality of hell— in the way they understood it.

A holy apprehension of hell is intelligible only when you see that salvation is the Marriage Supper of the Lamb.The prophet’s phrase meta tauta (“after these things”) in verse one signals a fresh set of visions, yet the jubilation that follows comes as the consequence of the fall of Babylon in the previous chapter. The kings of the earth mourn Babylon’s demise but the people of God celebrate it. The saints laud the victory of God by lifting up the psalmist’s familiar cry for the first time in the Apocalypse; they shout “Hallelujah,” which means simply, “Praise Yahweh.” The company of heaven sings “Hallelujah” not only because the devil's tyrants have been toppled but because the Father’s Son will finally wed his spouse and take her into his body.

Straightforwardly, when the Spirit of Jesus finally reveals to the prophet the event of salvation he shows him nothing other than the consummation of a wedding between himself and his bride.“Let us be glad and rejoice, and give honor to him: for the marriage supper of the Lamb is come, and his wife hath been made ready.”

Such imagery for salvation is not new in scripture.

Before his passion, Jesus promises his disciples that he is about to go to prepare a place for them in his Father’s house. It’s so familiar a scripture— a passage we associate with funerals not weddings. It’s so hackneyed a text we miss that Jesus is comparing salvation to the culmination of a nuptial ritual. In first century Jewish weddings, when a bridegroom betrothed himself to a bride, before the wedding ceremony, he would first go to his father’s house and build an addition onto the family home. Only after the bridegroom had prepared a place for his bride at his father’s house would the bridegroom return, make his promise of forever to his bride, and then take her to the place he had prepared for them and there take her unto himself.

The candid parallel between sexual union and salvation may make you squirm, but it’s the plain teaching of the scriptures.

The apostle Paul perhaps had Jesus’s farewell discourse in mind when, in his letter to the Ephesians, he interprets the mystery of sexual union by relation of Christ and the Church and by relation to the triune life itself.

This linkage between the erotic and the eternal is not limited to the New Testament.

In the Old Testament— the scriptures by which the church understood herself— Israel experienced the favor of her God as his burning, unquenchable, passionate love for her. The Book of Deuteronomy insists upon it as a matter of dogma. The Lord chose Israel not because Israel had a particular proclivity for covenant or unique potential for faithfulness.

The Lord chose Israel and made her his own for no other reason than that the Lord loved her.Israel’s election, her chosenness, is the result neither of a rational decision nor an arbitrary one. God is the God of Israel because the Lord fell in love with her.

Meanwhile, the Song of Songs, a biblical book that is all about erogenous zones and seductive aromas and lovers looking for a place to be alone, unabashedly asserts that human sexual love is the most precise analogue of the love between the Lord and his people.

And take care to notice the claim made there. Sexual love is only an analogy.

Salvation is like a lover delighting in their beloved and enjoying their bodies’s grace.

But—

Of all the analogies we might use, out of all the other images and pictures we might conjure, sexual love is the most precise analogue.And for this reason the Song of Songs was quite possibly the book of the Old Testament most important to the church fathers who compiled the New. Thus, in the Song of Songs, Israel does not long for forgiveness of sin or rescue from exile or for other gifts detachable from the Giver. Israel longs simply for the Lord himself. And it is a longing precisely for the Lord’s touch and kiss and fragrance. Just so, the Old Testament imagines lovemaking out of doors in a springtime Eden as an image of the Lord with his people in the Last Future.

Salvation, the Song extols, is akin to a woman sheltering under her lover and tasting his fruit.

Whatever salvation is, it’s most like that.

For Israel, “the Lord is simply lovable, and salvation is union with him, a union for which sexual union provides the most precise analogy.” Or as St. Augustine captured this very theme in the Confessions, “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they find their rest in you.”

On Saturday, I went to the hospital to visit a dear friend whose wife had suffered a massive heart attack the night before.

She had collapsed in their living room just before they left for a dinner date.

Steve had tried to mimic the chest compressions he had seen in movies.

By the time the ambulance arrived, Kathy’s heart had been still for over three minutes.

After cardiac surgery, Kathy’s lungs filled with fluid and so she was intubated, the ventilator preventing her breath from becoming air.

When I knocked on the glass door in the ICU, Steve was holding his wife’s hand and whispering in to her unresponsive ear, “I love you. I love you. I love you. I love you.”

No longer his pastor, I tried to be his friend.

I sat down next to him and put my arm around him and listened to his worries about his children, his regret about not letting her die quickly in their home, and his fear of living in that home after she dies.

At one point in our conversation, he looked over at me, with raised emphatic eyebrows, and he pointed at her and said, “All I want to do— all I want to do— is pull all that stuff off of her and give her a kiss on the lips.”

He was pointing at the tubes obscuring her nose and mouth and neck.

“All I want to do is pull all that stuff off of her and give her a kiss on the lips. Is that crazy?”

“No, it’s not crazy,” I said, “It’s holy.”

It’s salvation.

The erotic terms in which scripture envisions the End may discombobulate us or even embarrass us; nevertheless, they are a logical correlative to the consummation of history.

That is, scripture likens salvation to the consummation of a marriage because scripture anticipates the consummation of history.When history ends, there will be nothing left for us to enter into other than God; just so, sexual union is the most precise analogue for the Lord’s End with us.As Robert Jenson writes,

“Let me put the question: What could be an end of history, other than a sheer and thus meaningless termination? God, we said, creates a history that is a whole, a creation, only because it has an end. But what could "an end" be? If we got to history's end, what would we discover? That time and discourse had simply stopped? How then could we discover this? And why anyway would one want to get to such a point? Is the notion even intelligible?

The one conceivable end of history, that will not cancel the whole being of history, must again be a sublation. But into what? When creation ends, there is only one thing left to be taken into, and that of course is God. Thus the doctrine of theosis, the doctrine that our end is inclusion in God's life, is not merely the brand of eschatology preferred by the Eastern churches; it names the only possible "end" of a creation, the only possible end of being that is history and drama.”

Scripture envisions salvation in such carnal terms because in the End, when God consummates history and there is no remainder to creation, the Father’s people— the Son’s bride— will enter into his triune body.

Because salvation is union with God, the process of God’s hell is necessary for God’s heaven.A bride must be prepared for her groom.It’s the fourth verse of Charles Wesley’s hymn, “Finish then, thy new creation; pure and spotless let us be…” Because salvation is union with God, the process of God’s hell is necessary for God’s heaven. As imperfect as the word process is, it is an essential word in that it reminds us what the church fathers so clearly taught but what we so often fail to heed.

Namely—

Heaven and hell are not locations.They are relations.Hell is not a place.Hell is a process.To be clear, the doctrine of hell as the church fathers taught it is not hell as Michelangelo or Bosch painted it. The doctrine of hell as Gregory of Nyssa or Origen taught it is not hell as Dante described it. The doctrine of hell in the tradition or in the scriptures is not the same as the hell of popular imagination.

Hell as a place of eternal conscious torment into which God sorts individual people— such a hell “requires a mythical sort of God.” Hell so conceived is unworthy of God and at odds with the gospel. God is not cruel. God is just and loving. Indeed, properly understood, “God is just” and “God is loving” are redundant statements.

Therefore, the doctrine of hell is a necessary component to the gospel hope because without it God’s character is impugned. God cannot fail to do justice for those who were wronged, even as he has mercy on those who did the wrong.

Hell is not so much for sinners as it is for those who sinned against sinners, those who took advantage of others’s brokenness or oppressed them in their misery.

God damns the abusers, the victimizers, the violators. And he damns them both for their own sake and for the sake of those abused, victimized, and violated. No wrong can go unanswered.

Again, this is the straightforward teaching of the church fathers, many of whom simultaneously taught that all shall be saved.In the tradition— the tradition that gave us the New Testament— hell is the name for the process in which God separates sinners from their sins, destroying not only those sins but the evil that animates them. Hell is what the theologian Pavel Florensky called:

A “fiery surgery,” in which “every impure thought, every idle word, every evil deed, everything whose source is not God, everything whose roots are not fed by the water of eternal life … [is] torn out of the formed empirical person, out of human selfhood.”

In other words, hell is the process at the end of which nothing is left but pure creatureliness, burning with the divine light in the divine love.

This hell is what the scriptures announce when they declare the “the Lord is a refining fire.”

Preaching on this doctrine of hell, George MacDonald insists:

“Love loves unto purity … Therefore all that is not beautiful in the beloved, all that comes between and is not of love’s kind, must be destroyed. And our God is a consuming fire.”

For MacDonald and, just so, for the tradition, God is heaven and God is hell. Heaven and hell are not locations. They are relations.

In particular, hell is the way God relates to us; so that, both we and those we have sinned against are delivered from our sins.As the Irish theologian from the Middle Ages, Eriugena, puts it:

“It is not part of God’s justice but wholly alien from it to inflict penalties on what he has made. Instead, God inflicts penalties, justly, on all that he has not made.”

That is, sin, not the sinner, evil, not the evildoer, is destroyed. Murder and abuse and rape and despotism and racism and lying, like all evils, are God-damned and forever eradicated. God does not merely “forgive” the rapist and then expect the one who was raped simply to accept that this forgiveness is just. God, somehow, consumes the sin itself, the evil that was done, so that both the victim and the victimizer are made whole.

Hell and heaven do not name the sorting of individuals according to who did and did not believe.

In the End, there is neither the good place nor the bad place there just is God.And because he is the Bridegroom who will take us into his body, our sins must be separated from us.This is the doctrine of hell.This is hell as the fathers taught it. Hell as purgation not perdition. Far from being frightening news, rather than being the gospel’s contrary, this doctrine of hell— hell as separation of the sinner from his sin, hell as the eternal eradication of evil—only this doctrine of hell can answer the problem of evil.

The intersection of justice and mercy in Amber Guyger's judge, the offer of undeserved forgiveness from her victim’s brother, it not only perplexed the secular media it provoked outrage from observers.

Meanwhile many religious people meanwhile insisted that Brandt Jean should not have forgiven his brother’s trespasser in the absence of any penance.

One religious leader tweeted, “Forgiveness without justice is injustice.”

And, of course, he was correct, forgiveness without justice is injustice.

I mean—

Should the mothers mourning in Israel and in Gaza simply forgive the terrorists who beheaded their babies or the soldiers bombing their children?

Forgiveness is too weak a word to summarize the gospel hope.

Hell as a place of eternal conscious torment is anathema to the gospel.

Hell as the process by which God separates sinners from their sins is righteous.

Is it possible that some creatures are so consumed by their sins that nothing of them will remain after they’ve encountered the consuming fire of God’s love?

The tradition has been reticent to answer.

Nonetheless, hell as purgation is not a doctrine to be avoided. It’s a doctrine to be celebrated— a promise to pray for and a hope to cling to— because it teaches us better than anything else that God’s forgiveness is not the triumph of mercy over justice but the triumph of justice in mercy. Scripture is clear, Yahweh offers no amnesty to the wicked. The Lord insists on a reckoning. In the end, simultaneous to the End, the consuming fire of God’s love will actually make all wrongs right, transfiguring what we have done and what has been done to us without simply undoing what has happened.

Because God is loving, we can be certain of the dawn.Because God is just, we can look forward to hell.Robert Jenson asks what makes final salvation in fact both final and salvation, and he answers:

“Precisely that we are set right with each other, that I have the joy of God’s rebuke for my sin against my brothers and sisters, and the joy of seeing the repair of my injuries to them, at my cost.”

That is the hope— first God is hell; then God is heaven.

That is what the Song of Songs means by declaring that love never fails.

I visited my friend last night in the hospital.

After I prayed, I watched as he delicately, meticulously moved all the tubes and tape safely to the side of her mouth— moved everything that was in the way between them— so that, he could kiss his bride.

The hope called hell is that in the End God will do likewise with us.

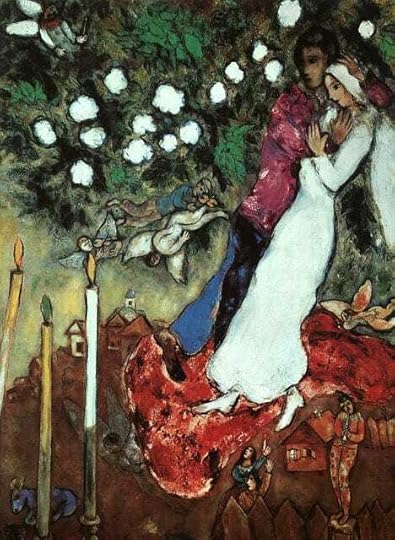

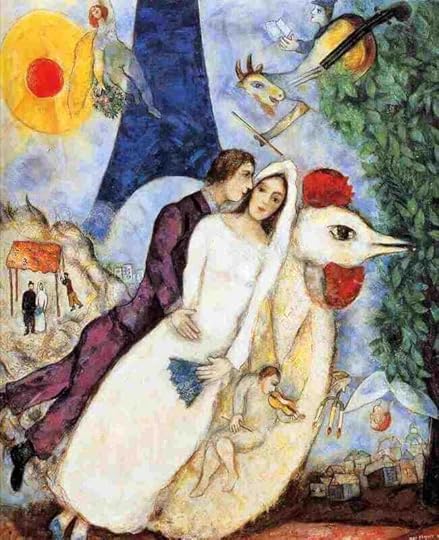

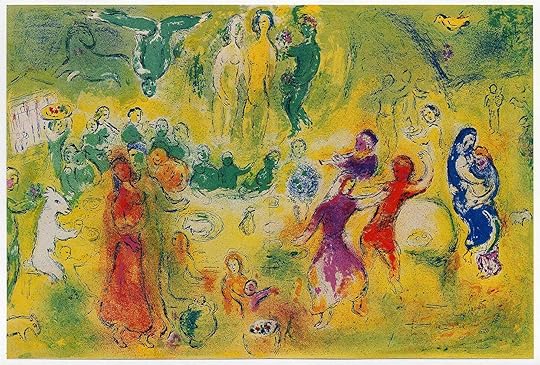

(images, “The Wedding,” by Marc Chagall)

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers