Jason Micheli's Blog, page 65

September 14, 2023

The Road to Hell is Paved with Amnesia

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The lectionary Gospel for Sunday is from Matthew 18.21-35, the troublesome text in which Peter presses the Lord about mercy’s boundary.

When Peter asks Jesus if forgiving someone seven times is sufficient, Peter must’ve thought it was a good answer. Peter’s a hand-raiser and a butt-kisser. Peter wouldn’t have volunteered if he thought it was the wrong answer.

After all, the Jewish Law commanded God’s people to forgive a wrongdoer three times. Seven times no doubt struck Peter as a generous, Jesusy amount of forgiveness. Not only does Peter double the amount of forgiveness prescribed by the Law, he adds one, rounding the total to seven. Because God had spoken creation into being in seven days, the number seven was the Jewish number for completeness and perfection.

Peter might be an idiot, but he’s not stupid.

Peter knew seven times— that’s a divine amount of forgiveness.

Think about it— seven times:

Imagine someone sins against you. Say, a church member gossips about you behind your back. I’m not suggesting anyone in your church would do that, just take it as a for instance.

Imagine someone gossips about you.

And you confront them about it.

1. And they say: ‘I’m sorry.’ So you say to them: ‘I forgive you.’

2. And then they do it again. And you forgive them.

3. And then they do it again. And you forgive them.

4. And then they do it again. And you forgive them.

5. And then they do it again. And you forgive them.

6. And then they do it again for sixth time. And you forgive them.

I mean...fool me once shame on you. Fool me 2,3,4,5,6 times...how many times does it take until its shame on me?

It’s got to stop somewhere, right?“What’s the limit, Jesus? Where’s the boundary?”And remember, Matthew 18 is all one scene. It’s Jesus’ yarn about the Good Shepherd, who all but abandons the well-behaved ninety-nine to search out the single sheep too stupid to stay with the flock, that prompts Peter’s question and the parable that answers Peter’s question.

How many times should the lost sheep be sought and brought back, Jesus?

How many fatted calves does the father have to slaughter for his kid?

How many times do we have to forgive, Jesus?

And Peter suggests drawing the line at seven times. Whether we’re talking about gossip or anger or adultery or synagogue shooters, seven is a whole lot of forgiveness. Probably Peter expected a pat on the back and a gold star from Jesus. But he doesn’t get one.

Notice what Jesus doesn’t do with Peter’s question.

Notice what Jesus doesn’t do with Peter’s question.Notice— Jesus doesn’t respond to Peter’s question with another question. Jesus doesn’t ask Peter “What’d they do?” Jesus doesn’t say “Well, you know, it depends— the forgiveness has to fit the crime.”

No, Jesus takes it in the other direction: “Not seven times, but, seventy-seven times.”

Seventy-seven times— pay attention, now, this is important.Jesus didn’t pull that number out of his incarnate keister.By telling Peter seventy-seven times forgiveness for those who sin against you, Jesus hearkens back to the mark of Cain and the sin of all of us in Adam.In Genesis 4, after Cain murders his brother Abel, in order to prevent a cyle of bloodshed, God— in God’s mercy— places a mark on Cain, and God warns humanity that whoever harms Cain will suffer a sevenfold vengeance. They will receive seven times vengeance, God warns.

Later in Genesis 4, after civilization is founded east of Eden on the blood of Abel, Lamech, Cain’s grandson, murders a man. And in telling his two wives about the murder, Lamech plagiarizes God’s promise for himself and Lamech declares that if anyone should harm Lamech then vengeance will be visited upon them— guess how many times— seventy times.

If you don’t get this, you won’t get it.When Jesus tells Peter he owes another seventy-seven times forgiveness, Jesus is not fixing a boundary, albeit a gracious and superabundant boundary.No, Jesus is saying that in him there is no limit to God’s forgiveness because his is a pardon powerful to unwind all of our sin as far back as Adam’s original sin.September 13, 2023

The Exodus is an Apocalypse

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The Old Testament lectionary text this Sunday is Exodus 14:19-31.

God is whomever raised Jesus from the dead, having first raised Israel from bondage in Egypt, says Robert Jenson. Just so, the exodus is an apocalypse.

As much as we throw around that word, “apocalyptic,” it’s meaning in the Bible is “good news,” not grim news. Theologically speaking, apocalyptic (ἀποκάλυψις) in the Bible does not refer to brimstone and doom. Instead, ἀποκάλυψις means unveiling, revealing. Or, as Paul uses it in his letters, “an incursion.”

In the New Testament ἀποκάλυψις refers not to the end times, but to an event in time.

In the holy scriptures, an apocalyptic moment is when the Living God moves in this Old Age of Sin and Death, moves to act decisively on behalf of His people.“Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” is an apocalyptic moment.

“Lazarus, come out! Unbind him of his grave clothes and set him free!” is an apocalyptic moment.

“Little girl, wake up!” is an apocalyptic moment.

And so is the penultimate event of Almighty God delivering his captive children from Egypt.

In the Bible, the Exodus is an apocalyptic event second only to the Passion and Passover of our Lord Jesus Christ.

In fact, from the very beginning, the Church understood the latter in terms of the former. St. John of Damascus did so nearly a millenia ago in his Easter hymn, “O Come, Ye Faithful, Raise the Strain.” Listen to the way St. John narrates Easter in terms of the Exodus:

“Come, ye faithful, raise the strain of triumphant gladness; God hath brought his Israel into joy from sadness; loosed from Pharaoh's bitter yoke Jacob's sons and daughters; led them with unmoistened foot through the Red Sea waters.”

Or consider the preface to the ancient liturgy for the Easter vigil two nights from tonight,

“Dear friends in Christ,

On this most holy night, in which our Lord Jesus passed over from death to life, the Church invites her members, dispersed throughout the world, to gather in vigil and prayer. For this is the Passover of the Lord, in which, by hearing His Word and celebrating His Sacraments, we share in His victory over Death. He is the true Paschal Lamb, who at the feast of the Passover, paid for us the debt of Adam's sin, and by His blood delivered your faithful people...”

The Exodus event is how Jesus himself interprets the meaning of the apocalyptic event that will be his death and resurrection:

“On this night, when He was betrayed, Jesus took bread. He broke the bread, He gave thanks to God, He gave the bread to his friends and said, “Take, eat. This is my body [of the Passover] given for you.”

The full liturgy for the Easter vigil is quite long, guiding worshippers through nine thick scripture readings— all from the Old Testament. However, if a church must condense the Easter vigil for the sake of brevity, the liturgy stipulates that if only a single scripture is to be read, it must be this text from Exodus, the story of the deliverance at the Red Sea.

In other words, from the first Easter, the Church has insisted that Christ’s act of redemption is unintelligible apart from the apocalyptic event of Yahweh rescuing His people from the Enemy who bound them.

“Come, ye faithful, raise the strain of triumphant gladness; God hath led Jacob’s sons and daughters with unmoistened foot through the Red Sea waters.”

More so than the creatures of bread and wine, what’s important about the exodus is the apocalyptic event with which Christ frames His own mighty work on our behalf.

For Christians, more important even than the Exodus story is its God— a God who is powerful to move in our world on behalf of a frightened and powerless people.

A Living God who is able—

Able to make a way out of no way.

Able to call into existence the things that do not exist.

Able even to give life to the dead.

A Mighty God, who will in due season, the Apostle Paul proclaims, trample the Enemy under our feet, an Enemy Paul calls a Pharaoh named, “Death.”

Even in the Book of Exodus, the Passover meal, the bread and the wine, is not as important as the event to which they point. That’s why, long after the event, God kept addressing the Israelites as though they themselves were the ones He had delivered through the Red Sea. Hundreds of years after the Exodus, God says to the prophet Amos, “I brought you up out of the land of Egypt, and led you for forty years in the wilderness, to possess the land.”

It’s as if Amos had been there, with his back to the sea with nowhere else to turn— and, don’t forget, the sea in the Old Testament symbolized Death.What’s important about the exodus event is the Creator who has covenanted to be God for us and who will act to make good on the “no matter what” part of His promise.

And notice—“Moses stretched out his hand...the Lord drove the sea back.”God did not equip Moses with the ability to drive the sea back and divide the waters. The Lord himself did it. For you.

“But Moses said to the people, ‘Do not be afraid, stand firm, and see the deliverance that the Lord will accomplish for you today; for the Egyptians whom you see today you shall never see again. The Lord will fight for you, and you have only to keep still.’

Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea. The Lord drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night, and turned the sea into dry land; and the waters were divided.’”

September 10, 2023

Boot-stomping, @#$-kicking Jesus

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

I am away this week, canoeing with my friends Todd Littleton and Tony Jones and talking the theology of creation in the million acre Boundary Waters between Minnesota and Ontario. Tracking with my series through the Apocalypse, here’s an old sermon from the vault on Revelation 12.

Revelation 12.7-12

Nearly a year ago this month, I found myself trapped on the corner of Washington and King streets in Old Town. I was headed into Banana Republic. As folks in the 8:30 service frequently point out, I “don’t own many ties.” I have fewer dark ones. And that Friday I needed one, a black or a grey one. Because the night before, Jack, the little boy from our confirmation class, had been pronounced dead as I held his hand in the ER. I was in a hurry, still feeling numb. But standing there on the corner, blocking my path, were 4 or 5 men and women. Evangelists.

A couple of them of were holding foam-board signs high above their heads. The signs were brightly illustrated with graphic images of a lake of fire, a 7-headed dragon and a terrible-looking lion with scars on its paws. At the bottom of one of the signs was an illustration of people, men and women...and children...looking terrified, looking like they were weeping.

A couple of them were passing out pamphlets.

I tried to slip by unnoticed. One of them tried to hand me a tract, so I just held up my hands and said “I’m a Buddhist.” But the young man blocking my path wasn’t fooled. He pointed at my open collar and said, “But you’re wearing a cross around your neck.”

“Oh, that,” I feigned surprise.

The young man looked to be in his twenties. He didn’t look very different from the models in the store window next to us. He handed me a slick, trifold tract, gave me a syrupy Joel Osteen smile and said, “Did you know Jesus Christ is coming back to Earth?”

Then he started talking, with a smile, about the end of the world. I flipped through his brochure. It was filled with images and scripture citations from the Book of Revelation.

“Martin Luther said Revelation was a dangerous book in the hands of idiots,” I mumbled.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“Oh, just thinking out loud.”

Then he asked me if I was saved. “Because,” he said, “Jesus Christ was returning May 21 to destroy this sinful world, but that Jesus loved me and wanted me to invite him into my heart so I could be spared the tribulation.”

Now, don’t get me wrong, I’ll be the first to admit it. Sometimes, I’m prone to sarcasm. Sometimes, as the 8:30 folks like to point out, I have a tendency to be abrasive.

But that Friday, the day after Jack, what I felt rising in me was more like...anger.

“Lemme get this straight,” I said. “Jesus loves me so much that before he casts me and everyone else into the lake of fire and destroys all of creation, he wants to give me the chance to accept him as my personal savior.”

The evangelist smiled and nodded his head and immediately tried to close the deal, telling me I just had to accept that I’m a sinner and that Jesus died on the cross in my place.

Because he was still standing in my way, I decided to push his buttons.

“Why the cross?” I asked him. “Why does Jesus or anyone have to die? Why can’t God just forgive us?”

He gave me a patronizing chuckle and said, “But God can’t do that!”

“God can’t do that? God can create everything from nothing but God can’t forgive?”

He just nodded like this was the most obvious thing in the world and said, “That’s why Jesus has to die on the cross.”

“So what you’re saying is...my salvation hinges on how persuasive I find you- out here with your huge signs with dragons and lions on them?”

Okay, so maybe I was feeling a little sarcastic.

“I’m not sure you understand how serious this is sir,” he said to me.

“Oh, I got it. I just think its more serious that you don’t understand the cross or Jesus Christ and don’t even get me started on the Book of Revelation!”

It was right about then I became vaguely aware that I was creating something of a scene. A small crowd had stopped and were watching us like it was the scene of an accident.

And I could tell from the PO’d look on his face that this evangelist was now much less concerned about my eternal salvation, and if he could he’d probably volunteer to throw me in the lake of fire himself.

He reached into his back pocket and pulled out a business card.

“Maybe you should talk to a pastor instead,” he said.

“Yeah I’ll think about it.”

My assumption is that for most of you the Book of Revelation is like that acid-trip, boat ride scene from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

It’s like those Cosby Show episodes where Cliff Huxtable sneaks a midnight hoagie and then has whacked out dreams of pregnant men who give birth to toy boats and more sandwiches.

And why not?

Revelation is filled with bizarre, crazy images: dragons and horsemen named Death, lions that look like lambs, robes dipped in blood, pregnant women and numbers pregnant with meaning and above it all this image of a boot-stomping, butt-kicking Jesus Christ.

And my assumption is that, like those evangelists on Washington and King, you assume Revelation is about the future. That it’s like a visual morse code, warning us of what’s to come.

But when we treat the Book of Revelation like a Ouija Board that predicts the future, we miss the fact that St John writes down this vision God gives him, sneaks it out of the prison Rome has locked him in, and he sends it out to his churches not not to warn them of what’s to come one day but to remind them of what has already come to pass, once and for all, in Jesus Christ.

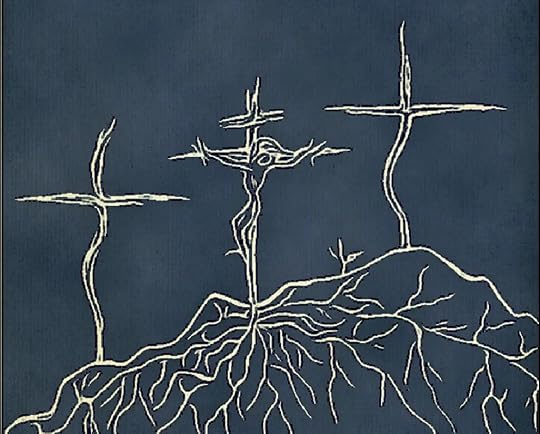

The Book of Revelation is not merely about the future.The church fathers believer it is also in scene after scene, in image after image, in symbol after symbol, about the cross. It’s a prophetic recapitulation of the passion story.

And not only that, as bizarre and crazy as Revelation might seem to you, if you don’t understand what John’s trying to convey, then you don’t understand the cross.

Here in chapter 12, John describes this vision of a heavenly battle between the forces of Satan and the forces of God.

On one side of this battle is the Dragon, whom John identifies as Satan.

But John doesn’t stop there. John gives the Dragon 7 heads and 7 crowns, the same number (everyone of John’s churches would’ve instantly known) as the number of Roman emperors from the regime that killed Jesus to the regime that threw John in prison and now persecutes his churches.

So John draws Satan as a dragon, as serpentine, and then costumes it as Rome to remind you that the powers that once killed Jesus and now persecute his People- this is the Evil that’s afflicted God’s creation from the very beginning.

On the other side of the battle that John sees is the archangel Michael, who in the Hebrew Scriptures personifies the power and might of God.

And in the middle, in Satan’s sights here in chapter 12, is a woman crowned with 12 stars- that’s Mother Israel, with her twelve tribes, from whom comes the Messiah.

Now notice— it’s the archangel Michael, the power of heaven, that throws the Dragon down, but notice what John says: it’s the blood of the Lamb that conquers and defeats the Dragon.

You see what he’s doing?

What John wants you to see is that if you could sit down in Heaven’s throne and look down upon the cross and see it as the angels see it, then what you would see is a battle, a cosmic battle.St John’s telling you the same story the Gospels tell you. He’s telling you the Passion story— only not from the perspective of those gathered near Jesus’s cross but from the perspective of heaven.

That when Jesus collides with the powers of Rome and the religious authorities and the mobs who scapegoat him and the friends who betray him, what’s really going on is that God, in Christ, is colliding, once and for all, with the Powers of Sin and Evil and Death. Satan.

You see—

It’s not that the cross is about placating an angry God who demands blood.

It’s not that there’s something in you, something about you, called sin that keeps God from loving you until someone dies for it.

No.

It’s that there’s something called Sin-with a capital S- in the world, outside us, all around us, that transcends us and victimizes us and dupes us and seduces us and enslaves us.

And God loves us so much that he takes flesh in Jesus Christ in order to throw the Dragon down once and for all.

John wants you to see that’s what’s really going on in the Passion story is that the Powers of Sin and Evil do their worst to Jesus:

He’s betrayed by one of his closest friends.

Peter, who’d sworn to always be there for him, to be with him till the end, swears Jesus off not once, not twice, but three times.

In the Garden, when Jesus is afraid for maybe the first time in his life, his friends aren’t there for him.

He’s spit on, struck and ridiculed.

He’s accused and lied about.

He’s stripped and mocked and beaten down and then he’s condemned.

To be nailed to the cross:

Where he’s stared at: naked and shamed.

And abandoned by everyone, including- it seems- God. Everyone but his mother and a friend.

The Powers of Sin and Evil and Death do their worst to Jesus. And how does Jesus respond?

Jesus never retaliates.

He never says a word in anger.

He never curses those who curse him.

He never raises a fist and strikes back.

He never prays for God to avenge him for what they’ve done to him. He never gives in.

Sin and Evil and Death do the worst they can do to him. And then three days later...guess what?...he comes back.

Jesus lives God’s love and forgiveness till his dying breath, and three days later his grave...is empty.

He wins. He conquers. He throws the Dragon down.

John wants you to see that from the foot of the cross Jesus might look like a suffering servant. But from the front row of heaven he looks like a boot-stomping, butt- kicking warrior.

Who wins with love.

What’s Good News about the cross is not Jesus’ death.

What’s Good News about the cross is that the cross is where the Powers of Death go to die once and for all.

What it means to be a Christian is to be believe that in Jesus Christ on the cross something cosmic and objective occurs.

Evil has been defeated and all that’s left of it in our world is like the last gasp of a dying enemy.

If you miss this...

The cross is not about individuals getting forgiven so that they can be with God in heaven when they die.

The cross and the empty tomb are God’s way of vindicating the life of Jesus; they’re God’s way of saying that love and forgiveness triumphs. Period.

And if that’s true, then it’s true not just on Good Friday, not just on Easter.

It’s true today and tomorrow and in our everyday lives: that the way we conquer and overcome and triumph over the sin and evil done to us is with love.

If I’m honest, I think what angered me most about those evangelists on the street corner- especially on the day after Jack- is how they made John’s Revelation seem so other-worldly.

And I know that for most of you any scripture about Dragons and Armed Angels and Women Crowned with Stars sounds very unrealistic.

It doesn’t seem to have much to do with this world, with this life, with your life.

I know that most of you have always assumed that any scripture with Dragons and Angels and Women Clothed with the Sun must be about some Future, not the Here and Now.

Then again, for many of you, I know something about your Here and Now. What’s it like.

I know plenty of you, in the Here and Now who’ve been betrayed, who’ve been sworn off by someone who promised to be with you always.

I know plenty of you, in the Here and Now, for whom those closest to you weren’t there for you when you needed them the most.

I know plenty of you, in the Here and Now, who know what it’s like:

To be struck

And ridiculed. Insulted and rejected. Lied about.

Scorned.

Rejected.

And I know there’s plenty of you in the Here and Now caught with someone else in an endless tit-for-tat, someone with whom you can’t resist returning every insult with a dig of your own, someone for whom you save one or two outstanding, unforgiven memories just to hang over their head and keep the upper hand.

I know there are plenty of you in the Here and Now who believe in Jesus Christ, who say you have faith in him, but still have someone in your life for whom you insist it’s impossible to forgive, someone in your life with whom no accusation can go unanswered, someone with whom you can’t put away the sword, turn the other cheek or show compassion or pray for the opposite of what they’ve done to you.

For a lot of you, I know plenty about your Here and Nows.

So maybe, despite all your assumptions to contrary, you need John’s Revelation to tell you that the Battle’s over, that the Enemy’s lost, that the sin and evil in your life only have their dying breaths left.

Maybe you need St John to paint his pictures of the cross to remind you that you don’t need to give in to what’s going on in your life.

You don‘t have to become what was done to you.

You can overcome. You can conquer. You can triumph.

But only with Love.

Because the love of Jesus Christ has already won.

Maybe you need St John to challenge you: to have more faith in the power of Christ’s love than you do in the power of Sin.

Maybe in the Here and Now, as bizarre and strange as it might sound, you need someone to tell you that the Dragon’s been thrown down.

September 9, 2023

Learning to Speak Christian

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Because the true God is triune, a colloquy unto himself, Christianity is primarily a linguistic endeavor. Jesus is the Word which words the world and Christianity is the attempt to learn how rightly to reply. Theology, then, is the discipline which attempts to equip believers to speak Christian.

The theologian Eugene Rogers was one of my first teachers. He has published the distillation of his undergraduate theology course as Elements of Christian Thought: A Basic Course in Christianese. He begins the book with a simple T/F, multiple choice test, the questions of which touch upon the matters Christians talk about when we talk about the God who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Try it for yourself:

True or FalseIf the human being had not sinned, Jesus would not have come.

Jesus could have come as a woman.

God should have become incarnate at the beginning.

The God of the Christians intends other religions.

O happy fault, that merited so great a Redeemer!

The ability not to sin is freer than the ability to sin.

God has died.

Multiple Choice1. How does God’s freedom relate to ours?

a. The freer God is, the less free I am.

b. The freer God is, the freer I am.

2. The word of God is

a. the sermon

b. Jesus

c. the Bible.

3. Jesus saves because

a. he pays the debt for sin

b. he teaches humans how to love

c. he defeats death

d. he tricks the devil at his own game

e. the Spirit gathers others around his body

f. he releases the prisoners of hell

4. The “debt for sin” is owed to

a. the devil

b. God the Father

c. your neighbor

5. Salvation is

a. freedom from sin

b. joining the Trinity

c. perfect community

d. resurrection of the body

6. Does God have a body?

a. No, silly, God doesn’t have a body

b. God has a body in Jesus

c. God has a body in the church

d. God has a body in the bread

Obviously, you can infer from the above that every question in Christian discourse can yield multiple orthodox answers, given the fact that scripture is a thick text and the Trinity is a lively conversation.

Got question?

Leave them in the comments.

September 8, 2023

Temporality is Not a Contrary to Eternity

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

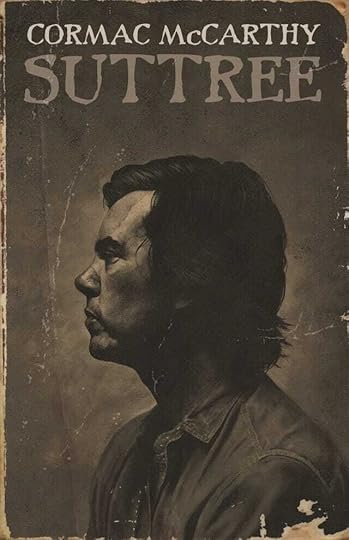

Of late and in light of his early summer death, I have begun to reread the work of my favorite writer of fiction, Cormac McCarthy. Suttree, the last and most ambitious of his southern quartet of novels, takes place among the least, the lost, and the left behind of 1950’s Knoxville. In it, the titular character, whose twin brother died stillborn, is haunted by the brevity of life and angry over the world’s brute contingency.

The theme runs like a seam throughout McCarthy’s work, “Given a time-bound world of chance, is belief in the Good/God intelligible?”

At the beginning of Suttree, Sut is trolling for fish from his ramshackle skiff when he floats past a rescue crew doing likewise for man who had jumped from the bridge in to the Tennessee River the night before. Having watched them pull the suicide from the water, a hook in his pale jowl, Suttree and Joe later walk past the dead man’s body on the riverbank.

McCarthy writes:

“They stood looking at the dead man. The squad workers were coiling their ropes and seeing to their tackle. The crowd had come to press about like mourners and the fisherman and his friend found themselves going past the dead man as if they’d pay respects. He lay there in his yellow socks with the flies crawling on the blanket and one hand stretched out on the grass. He wore his watch on the inside of his wrist as some folks do or used to and as Suttree passed he noticed with a feeling he could not name that the dead man’s watch was still running.”

Time marches on, and its dread momentum is its monument to the fact we do not.

Life is made up of minutes not moments.

Time takes hostages of all and brokers negotiations with none.That creatures are time bound, their distinction from the Creator must be a difference of finitude, or so the religion of Plato has long assumed. Thus, both common sense and philosophical discourse map the Creation/creature distinction according to pairings relatively foreign to the scriptures of Israel and the church— Infinite/Finite, Eternal/Temporal, Transcendent/Immanent. The biblical narrative, and the Christology it demands, however, display a distinction between Creator and creature that the pagan pairings attempt to avoid.

The Bible reveals a God who is the opposite of any deity Plato could countenance. The Bible reveals a Creator who is not immune to time.September 7, 2023

An Untidy Faith

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here is a recent conversation I had with Kate Boyd about her new book, An Untidy Faith.

In the wake of scandal, culture wars, and abuse, many Christians are wondering whether the North American church is redeemable—and if not, whether they should even stay. While many are answering no to those questions, this book is for those who long to disentangle their faith from all the cultural baggage and recapture the joy of following Jesus.

Through personal anecdotes, encounters with the global church, deep dives into Scripture, and helpful historical context about Christianity, An Untidy Faith takes readers on two journeys. The first journey lays out the grand vision of Christianity and the legacy passed on to us by the early believers in hopes of renewing readers’ belief in the church writ large. The second journey helps believers understand why they feel distant from their church settings and provides a reorientation drawn from Scripture of God’s vision for community.

A gentle companion, Kate Boyd walks alongside those who have questions but can’t ask them for fear of being labeled by or cast out of their communities. An Untidy Faith is a guidebook for those who want to be equipped with practices to rebuild their faith and shape their communities to look more like Jesus.

September 6, 2023

Christ is Not a New Moses

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The Old Testament lectionary text this week is Exodus 12.1-14 a passage with which Jesus summarizes himself the night he’s handed over to the cross.

On the night we betrayed him, Jesus’ Passover table in the upper room would’ve been set according to the Seder instructions in the Haggadah from the Book of Deuteronomy. The reason the disciples fall asleep later that night in the garden is because the Haggadah requires enough wine for four cups for each of them. Four cups of wine not one. Four cups, each of which represents one of the promises God makes to Israel about their deliverance:

Cup 1: ”I will take you out of Egypt…”

Cup 2. "I will save you from Pharaoh…”

Cup 3. "I will redeem you from captivity…”

Cup 4. "I will take you as a People…”

Along with the four cups, at the center of Jesus’ Passover table would have been brick-shaped mixtures of fruits, nuts and vinegar symbolizing the bricks that Pharaoh forced them to build, a plate of bitter herbs and a bowl of salt water symbolizing the bitterness and tears of their captivity, unleavened bread, symbolizing the urgency of their escape, and the lamb itself which the head of the household, the host, would’ve taken home from the Temple to skin it and then roast it for the feast.

Presumably Jesus is the one who kills and skins and roasts the lamb as he’s the host who leads the script that night. According to the Haggadah, that night in the upper room Jesus blesses the first cup of wine and invites them all to drink.

Then the bitter herbs, which Jesus blesses and invites them to eat with the salt water. Then comes the bread and the dried fruit and the lamb.

Next, Jesus the host would have poured the second round of wine, retelling the story of the Exodus, before inviting his disciples to drink.

Then, according to the script, Jesus breaks the bread.

And according to the script, according to the Haggadah, what Jesus is supposed to do next is bless the bread, mix it up with some of the herbs and fruit and lamb and say to his table mates, ‘This is the body of the Passover.”

But Jesus changes the script.He inserts himself into it. He doesn’t say, ‘This is the body of the Passover.” He says, “This is my body.”He connects the body of the Passover Lamb to his body and then he connects it to their bodies by saying, “Take and eat.”

Jesus changes the script.

Jesus takes the symbolism and promises behind the herbs and the fruit and the bitter herbs and the bread and the lamb and he ties them not to his teaching or his preaching, not his miracles, not to his compassion for the poor or his prophetic witness against power.

Jesus changes the script.

Jesus takes the symbolism and promises of the Passover meal and ties them to his body. To his death. “Take and eat. This is my body broken…”

As the host of his last Passover, Jesus doesn’t just change the script. He adds to it.According to the Haggadah, after they feast on the meal, Jesus is supposed to pour and bless the third cup of wine, and invite the disciples to drink it. Then, according to the script, they’re supposed to sing from the Book of Psalms before blessing and drinking the fourth cup of wine.

Except, after they feast on the meal, when the time comes, Jesus takes the third cup of wine, the cup symbolizing God’s redemption promise (“I will deliver you from captivity”,) and Jesus says, “This is my blood…drink from this all of you…”

Hang on. Drink what?

What’s blood doing on our table?

Leonardo DaVinci didn’t quite capture it in his Last Supper but if there was a WTF moment in the upper room it went down right there and then.

They’d be better off going back to eating and drinking with hookers and thieves. Blood shouldn’t be anywhere near their table. You didn’t need to be a rabbi like Jesus to know that according to the Law it was verboten to consume blood much less drink it. The law stipulated that "anyone of the house of Israel who eats any blood, I the Lord will set my face against that person who consumes blood, and will forsake that person as accursed…”

Blood is forbidden. Anyone who consumes it in any way is accursed.September 4, 2023

An Atheist's Ten Commandments

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Hi Friends,

Happy Labor Day!

Just a reminder to all who participate in the Monday evening sessions on the Book of Revelation, there will be no class tonight. We’ll resume next week. You’ll be the fine hands of Josh, Kelly, and the Minion while Todd and I attempt to survive our canoe trip in the Boundary Waters. They will pick up in Revelation 6.

Atheist philosopher Alain de Botton, author of The Consolations of Philosophy, offers a list of commandments for those who can't believe in the God of the more ancient and famous torah. The good news, I suppose, is that the philosopher provides no stipulations against coveting your neighbor’s spouse nor do you need any longer to fret over your failures to keep the sabbath holy. He lists the atheist’s virtues thusly:

Resilience: Keeping going even when things are looking dark.

Empathy: The capacity to connect imaginatively with the sufferings and unique experiences of another person.

Patience: We should grow calmer and more forgiving by being more realistic about how things actually happen.

Sacrifice: We won't ever manage to raise a family, love someone else or save the planet if we don't keep up with the art of sacrifice.

Politeness: Politeness is closely linked to tolerance— the capacity to live alongside people with whom you will never agree but at the same time, cannot avoid.

Humor: Like anger, humor springs from disappointment, but it is disappointment optimally channelled.

Self-awareness: To know oneself is to attempt not to blame others for one's troubles and moods; to have a sense of what's going on inside oneself, and what actually belongs to the world.

Forgiveness: It's recognizing that living with others is not possible without excusing errors.

Hope: Pessimism is not necessarily deep nor optimism shallow.

Confidence: Confidence is not arrogance; rather, it is based on a constant awareness of how short is life and how little we will ultimately lose from risking everything.

Alain de Botton does not end conclude his law-laying as does Christ, “Be perfect as your Father in heaven is perfect,” but he nevertheless proves that you need not believe in the Lord to feel accused by the Law.

Be confident, as your Father in heaven is confident!

How’s that working out for you?

Nonetheless, the philosopher’s commandments for navigating a world without God are if not attractive then at least a bit more practical and everyday than the list Moses brought down from Mount Sinai. I may not be able capable of keeping myself from coveting my neighbor’s wife, but I can determine to be polite in nearly everyday circumstances.

But the atheist’s list commits the same folly as those who foolishly wish to post the Mosaic commandments in civic spaces. The latter advocates, ironically enough, are just as atheistic as the former.That is, in both cases the commandments become merely a list aspirations or aversions shorn of any guiding narrative or interpretative community to exemplify them for some true End.

Just as it's not self-evident what it means to refrain from covetousness, it's not self-evident what the practice of empathy entails.

Both require exemplification and a community of authority, which is to say neither is possible apart from God and the communion of saints he makes possible.

Without a body ordered to a polity, one person's version of empathy will differ markedly from another person's definition, both will turn upon the narrative around which they orient their lives.

For Christians, after all, all notions of humor are unintelligible apart from the greatest joke of all time, the crucified Jesus lives with death behind him.And any understanding of forgiveness, for instance, falls short if it does not refer in its fullest to the death of Christ for the ungodly. Meanwhile, patience, for Christians, does not name the attempt to “grow calmer and more forgiving by being more realistic about how things actually happen.” Patience is simply the practice of prayer and eucharist, acts by which we point to the great nevertheless of God’s guaranteed End in a world that is red in tooth and claw with contingency.

The commandments, whether the atheist’s or the believer’s, are unintelligible apart the story-formed community one inhabits.And this is the dread lie and empty despair of something like an atheist’s torah. For it’s not a question of whether we will be shaped by a guiding narrative but which one we will allow to shape us.

The very notion that we don't need a controlling narrative to our lives is in fact the narrative of modernity; it's its own story.

Modernity calls this story “freedom.”

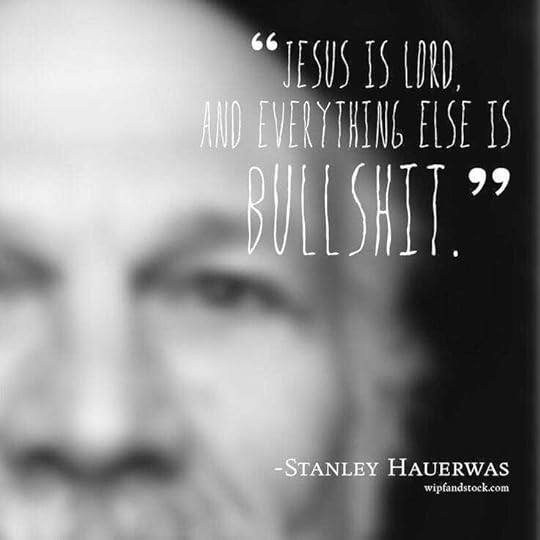

But, as Stanley Hauerwas notes, notice how “you never got to choose the story which told you that you should have no story but the story you chose when you had no story.”

Thus, the offer of commandments that need not the Storyteller is an invitation into a counter-story whose tellers seldom straightforwardly announce themselves. To Hauerwas’s point, usually these narratives’s gods go by names like Mammon and the Market, Nihilism or Empire.

While modernity was defined by the attempt to live in a universal story without a capital-S Storyteller, the story the Bible tells self-attests to be the story of God with his creatures. The Bible both implicitly assumes and explicitly asserts that there is a true Story about the universe exactly because there is, what Robert Jenson calls, a universal novelist. As Alain de Botton exemplifies, the modern world in the west— a modern western world the east is right to fear— was founded upon the attempt to live in a universal story (“Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”) without a universal Storyteller.

Without such a Storyteller, virtues will always be but arbitrary aspirations.For example, note how the atheist’s ten commandments manage to construe sacrifice in a way that requires not you offer your life for the sake of the other nor expect your children to suffer because of your convictions. Jonathan Edwards writes that true virtue will always be exceedingly rare in this world because it is the defining characteristic of the new one. Without a Storyteller to write this new world into being, virtue may be no less rare but we cannot know if it is true.

The experiment of modernity has failed.

It failed necessarily, for if there is no universal Storyteller, then the universe can have no story line. Neither you nor I nor all of us together can so shape the world that it can make narrative sense.

As Jenson writes:

“If God does not invent the world’s story, then it has none, then the world has no narrative that is its own. If there is no God, or indeed if there is some other God than the God of the Bible, there is no narratable world.”

In the project called modernity, the world lost its story.

The world lost its story by attempting to negotiate history without the One who is making history. This poses a question for all who otherwise attempt to speak gospel. In a world that’s lost its story, in a world “that entertains no promises,” how can the church speak her hope of the End?

The church, insists Jenson, must learn to do what Tolkien and Rowling, Lucas and the Duffer Brothers do so well.

The church must be world-builders:

"The church must herself be a communal world in which promises are made and kept. It is the whole vision of an Eschaton that is now missing outside the church. The assembly of believers must therefore itself be the event in which we may behold what is to come. Nor is this necessity new in the life of the church. For what purpose, after all, do we think John the Seer recorded his visions? If, in the post-modern world, a congregation or whatever wants to be “relevant,” its assemblies must be unabashedly events of shared apocalyptic vision. “Going to church” must be a journey to the place where we will behold our destiny, where we will see what is to come of us. Out there—and that is exactly how we must again begin to speak of the society in which the church finds itself—there is no narratable world. But absent a narratable world, the church’s hearers cannot believe or even understand the gospel story—or any other momentous story. If the church is not herself a real, substantial, living world to which the gospel can be true, faith is quite simply impossible.”

Stanley Hauerwas likes to joke that “Jesus Christ is Lord and everything else is bullshit.”

Like any good joke, it’s funny because so much is riding on its truth claim.

If Jesus is not Lord, if there is no Father to have raised him, then everything else is bullshit.

In which case, the atheist’s seventh and ninth commandments negate one another. Obedience to the former (self-awareness) makes the latter (hope) a cruel aspiration.

September 3, 2023

Heaven is a Yeshiva

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Revelation 11.15-19

In numbed America, the doom loop is so inexorable, you know how these stories almost always go.

Almost always go.

On August 20, 2013, as gun legislation languished in Congress, Michael Hill, a twenty-year old man who was off his psychiatric medications because his Medicaid had expired, walked into McNair Discovery Learning Academy in Decatur, Georgia armed with an assault rifle, five hundred rounds of ammunition, and, as he put it in a social media post, “nothing to live for.”

There were 870 children in in McNair Discovery Learning Academy that summer morning, all of them between the ages of five and eleven. Entering the school, Michael Hill immediately took a hostage— not a student or a teacher but the school’s bookkeeper, Antoinette Tuff.

Though she rightly feared for her life, Tuff offered an odd, miraculous act. Boldly, the school bookkeeper calmly poke to the aspiring mass shooter as one neighbor speaks to a fellow neighbor. For nearly a half hour, Tuff spoke to Hill with empathy and love. The emergency dispatcher recorded every word of their conversation. Her words to him during that abyss of time managed to save not only the lives of everyone else in the school but the gunman’s own life.

“We’re not going to hate you,” Tuff said, referring to Hill first as “sir” and later as “sweetie” and “baby.” The bookkeeper shared with the gunman stories of struggle from her own life to calm him– a recent divorce, a son with multiple disabilities.

At one point in the 911 call, Tuff told Hill:

“It’s going to be all right, sweetie. I just want you to know I love you, though, OK? And I’m proud of you. That’s a good thing that you’re just giving up and don’t worry about it. We all go through something in life. No, you don’t want that. You going to be OK. I thought the same thing, you know, I tried to commit suicide last year after my husband left me. But look at me now. I’m still working and everything is OK.”

Michael Hill was armed with an AK47 rifle.

Antoinette Tuff was armed with a faith formed by the commandments.

Recalling the incident to a journalist for the Guardian, Tuff said, “My pastor, he just started this teaching on anchoring, and how you anchor yourself in the Lord and his law,” recalled Tuff, who said she was terrified. “I was screaming and terrified on the inside. I didn't even know I was calm until everybody kept saying that. I just sat there and started praying that I could love my neighbor as myself…I prayed that everything that I had heard God say to me, was what I came out of my mouth with.”

Eventually, while keeping police at a distance, she persuaded him to give up his weapons, lie on the floor, and give himself up.

Anchor yourself in the Lord and his law.

Here in the eleventh chapter of the Apocalypse, we are still in the midst of the woes announced by the eagle two chapters earlier, “Woe, woe, woe to the inhabitants of the earth, at the blasts of the other trumpets that the three angels are about to blow!” In between those woes, we also remain in the middle of the interlude that began chapter ten. Just after the John eats the mighty angel’s scroll and hears the Lord’s command to preach to the principalities and powers, at the top of chapter eleven the Seer is given to see the world’s foreseeable backlash to the word of the cross.

The Spirit of Jesus shows John the dead bodies of the Lord’s faithful witnesses, their corpses paraded through the city for three and a half days. John sees how the violence done to the Lord’s witnesses actually deepens human solidarity; it brings people together. All the inhabitants of the earth come together, John sees, celebrating a kind of anti-liturgy, gloating over bodies of the martyred, exchanging gifts and offering thanks and praise.

The two dead and tortured witnesses represent the church. It’s a grim portrait of the world’s veracious and stubborn resistance to God. And it’s a sobering picture of the destiny that what awaits those who attempt to endure, faithfully witnessing to the word laid upon us. It’s an image that will inoculate you against all forms of prosperity gospel and against every sentimental reduction of the faith. It’s so frightening because this just is what full, unmeasured faithfulness looks like in a fallen world, John is given to see.

Nevertheless!

Exactly as Sodom’s inhabitants parade around the bodies of the martyrs with impunity, the story takes a turn. It ends different than as you might expect. Suddenly, the seventh archangel blows his trumpet and heaven erupts with the chorus made famous by Handel’s Messiah, “The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah, and he will reign for ever and ever.”

Has become.

Has already become.

Even before the third and final woe unleashes overwhelms the world, John sees heaven sing of God’s victory as a past act. For instance, notice how the tense changes in the middle of the chapter, starting in verse eleven, from the future tense to the aorist tense. No longer is the Kingdom a future possibility; it is a present reality. So much so, the twenty four elders— the patriarchs of Israel and the apostles of the church— they fall down on their faces and sing, but the end of their song is different than you might expect.

In verse seventeen, the elders omit the familiar formula, singing not “The Lord God Almighty who is and who was and who is to come.” Instead they now sing, “The Lord God Almighty, who are and who were.” Their song no longer includes the final clause, “…and who is to come.” Just as an aside— notice that they speak of God in the plural, the way you would sing if God were triune. The elders edit heaven’s song so that it ends not in the future, as you expect, but the present tense, “for you have taken your great power and begun to reign.”

In other words, no matter what befalls God’s witnesses in the world, with Christ’s cry on upon the cross, “It is finished” the future Kingdom is already as good as arrived. As Desmond Tutu preached in the face of apartheid, “You have already lost!”

And then, at the culmination of this vision of reality— of the real world where God’s future Kingdom is so guaranteed you can speak as if it is already so— John sees God’s temple in heaven opened up. Like the revelation to Moses, the opening of the temple occasions flashes of lightening and peals of thunder, earth quakes and heavy hail. Finally, what does the Seer see at the center of the temple at the center of heaven?

The Spirit of Jesus shows John the ark, the vessel for the commandments the Risen Jesus once spoke to Moses on Mount Sinai.

John sees what the prophet Ezekiel before him was given to see.

There is torah in heaven.Anchor yourself in the Lord and his law.

A number of years ago the New York Times did a story about a black pastor named William James in East Harlem. The pastor, the article noted, was famous in his community for his work on behalf of the destitute and the downtrodden. The author of the article writes:

“The streets of the neighborhood are lined with storefront churches, as many as five on a block, and some of the ministers said it was difficult to get across the Christmas message of hope, joy, and celebration to those who have so little. But Reverend James disagrees. “The Christmas message,” he said, “the good news to the poor, is that you’re not going to be poor anymore.” “That message is a lot easier,” the pastor said, “than trying to get across the Christmas message to the rich that they’re not going to be selfish anymore.”

Notice what the pastor didn’t say to the Times reporter.

He didn’t say the Christmas message to the rich is, “You shouldn’t be selfish anymore.” He didn’t say, “Empty your pockets, or else. Make yourself low lest you who are first be lost forever.” He didn’t even say, “Sinner, repent of your selfishness.”

He just said, “You’re not going to be selfish anymore.”

You’re not going to covet anymore. You won’t store up treasures for yourself anymore. You won’t bury your talent in the ground anymore. You’re not going to be like that anymore.

As though, it’s not up to us who we will become.

As though, you are at best a bystander to what will be done upon you.

You will be made righteous.

Just as the commandments were made for you, one day you will be remade for the commandments.

The End is different than you might expect. But it’s not all that mysterious or mystical. It’s an optical promise. John and Ezekiel simply see the Lord’s promise at the beating heart of heaven, “I will be God and you will be my people.”

The Book of Esdras professes plainly, “It was us that you created the world.” The order is important.

Creation serves the covenant; the covenant does not serve creation.Thus, even though the commandments come later at Mount Sinai they are a priori in the creative aim of God. When God speaks winged creatures into existence, when his word hangs the stars in the sky and alights upon the dark waters and brings forth life, God already has in mind his people, Israel and the church.

God creates precisely in order to have unto himself a peculiar people ordered according to a particular polity— torah, law. Indeed the initial act of creation is itself an instance of law. God said and there was; that is, God commands the world to be and the command is obeyed, and the event of obedience is the existence of the world. God creates the world by utterance of moral intention for beings other than himself— we learned this in Revelation 4.11. “Thus God’s creating of the world is agency of the same sort as the torah by which he creates Israel.” In his Large Catechism, the Protestant Reformer Martin Luther teaches that “anyone who knows the Ten Commandments perfectly knows the entire scriptures.” Surely this is a ridiculous assertion unless God’s act from creation to Kingdom is one of moral intention.

God created in order to have a people order to a polity.And by definition, God gets what God wants— if not in this world, then in the age to come.

“I will be God and you will be my people.”

On the one hand, therefore, it is not at all shocking that the Spirit of Jesus shows Ezekiel and the prophet John that when you go to receive your heavenly reward what you be handed is neither a harp nor a Mai Thai but the law.

On the other hand, this could not be more surprising to us whose images of the life everlasting have been shaped by the western tradition. Starting with St. Augustine in the fourth century, western theology has conceived of the Fulfillment in individualistic terms, individual perfection (In heaven you will be the best version of yourself) and individual fulfillment (Heaven will be your ideal Labor Day weekend raised to the nth degree). But, straightforwardly, this is not the vision revealed by the scriptures. Because notice how easily heaven construed in such individualistic terms becomes a vague, numinous afterlife, an End even atheists and pagans can adopt.

What the eastern tradition of the church understood and has always preserved— what John Wesley recovered from Orthodoxy— is that “the life everlasting” named by the creed’s third article refers to God’s own life, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Therefore, heaven is no mere place for individual perfection and fulfillment. Heaven is the event of theosis, deification, incorporation into God’s own life, Father, Holy Spirit, and the Son with his Spouse.

Quite simply, a vision of heaven that can be secularized or made ahistorical is not true.

Heaven is the final twist, Robert Jenson writes, of Israel’s and the church’s career under God’s rule.

There may be beer in heaven. I’m reasonably certain your enemies will be in heaven. But I know, because the Bible tells me so, there will be torah there. The End is different than you might expect.

A friend of mine, Chaim Saiman, is an Orthodox Jew who teaches at Villanova’s school of law. Not long ago, we were talking and he told me how one of the most intense political issues in Israel is how to apply minute or peculiar parts of the commandments that the Israelites, because of the exile to Babylon and subsequent occupations by Greece and Rome, never enjoyed the circumstances in which they could countenance obeying. “Some of torah, it’s like it got frozen in amber,” he said, “but now that Jews have their own nation, we’re cracking it open for the first time and arguing about it means to follow it.”

“Such as?” I asked him.

“Such as dogs!” he exclaimed, “there’s a halacha against owning any pet that your neighbor could perceive as threatening. In the diaspora, we never had the option even to consider obeying the command. We weren’t in charge. Now that we’ve got a place of our own, we’ve got to consider what obedience means. So there’s cities all over Israel where you cannot own a dog now.”

“Why the need to take the torah so seriously?” I asked him.

“Because,” he said, “We want to learn to live together now how we will live in the Resurrection.”

And then Chaim told me about a passage in the Talmud, in which the ancient rabbis elaborate on the vision of the temple given to Ezekiel.

“The rabbis call it the “Academy of Heaven,”” he said, “Sit with those words for a moment. If there’s a temple in heaven, an academy, then heaven is not a place of angels, halos, lyres, pearly gates, or fluffy clouds, or of chariots, smoke, lightning, or thunder. Heaven is a place of torah study.”

“So you’re saying heaven is a yeshiva?” I asked him.

“Exactly,” he said and snapped his fingers, “What do you think about that?”

“I think a whole of Christians are in for a surprise,” I said.

He laughed.

“So,” I asked him, “Are you saying there are no dogs in heaven?”

“Sure,” he chuckled, “just not in my neighborhood.”

Anchor yourself in the Lord and his law.

Last fall I delivered a series of lectures on preaching for the clergy of the Anglican Church of Canada. During the cocktail hour one evening, a young female Inuit priest came up and asked me how she might take what I had said to them about sticking to the message of grace while also preaching from the last book of the Bible. Her parish is on a reservation in Ontario near a tribal school where the government had recently discovered the unmarked graves of children who had been sent there by force.

“What’s your advice to a new priest” she asked me, “for preaching on the Book of Revelation?”

“Don’t,” I said, chuckling to myself.

My laugh disappeared as quick as it had come when I saw the righteous offense flash across her face.

“I take it Revelation is important to you,” I said.

“It is to all of us indigenous,” she said.

“Why so?”

“Because Revelation is the one place in the New Testament,” she replied, “where we see the promise that one day the Christians who look like you— many of whom have done horrible things to Christians who look like me— will be beyond the possibility of breaking God’s commandments.”

You’re not going to be selfish anymore.

The young priests’s answer so surprised me that, after a few moments, I realized I’d been standing there with my mouth agape.

“What’s your advice?” she asked me again.

“Look,” I said, “It doesn’t sound to me like you need my help at all. I mean, just now, like right here, you’ve helped me to see that the End will be different than I expected.”

Do not covet.

Do not lust in your heart.

Sell all you own and follow me.

Be perfect as your Father in heaven is perfect.

Exactly because we do covet and lust in our hearts, don’t even tithe and are far from perfect, the Protestant tradition, going back to Augustine, has said that in this age the commandments convict us. We hear them as threats, Do this or else.

Lex semper accusat.

The law always accuses.

Actually, the accusatory nature of the torah is not unique to Protestantism nor even to the New Testament. The Old Testament repeatedly confesses the very same function of the law. After all, it was Israel’s failures to keep torah that led to the Lord destroying her and dismissing her into Babylon.

But what Ezekiel and the prophet John both see is that the law will not always accuse.Lex Autem Non Accusatis.If the law is here in the heaven promised to us in Christ Jesus, then it necessarily follows that in the life everlasting we will have passed beyond the possibility of disobedience.Which is to say, even in the End God will not cease to be holy and we will not cease to be creatures. In the Kingdom, there is no possibility of not honoring the Lord’s holiness through obedience. You won’t be able to covet. You won’t be able to lust. You won’t be able to be ungenerous. Which is to say, you will be free.

You will finally be free.

“True virtue,” Jonathan Edwards wrote, “has no evidence in this world because it is defining characteristic of the new one.”

We want to learn to live together now how we will live in the Resurrection.

Antoinette Tuff, the bookkeeper whose obedience to the law subdued a mass shooter, was asked by an NPR reporter on why, in her myriad interviews, she never once mentioned that Michael Hall, the would-be gunman is white and that she is black. Tuff responded to the NPR reporter by saying:

“Well you know, one thing [in the commandments] God says, God doesn't say anything about color. He says “love thy neighbor.” He doesn't say love thy neighbor because you white. He doesn't say love thy neighbor because you black. He doesn't say love thy neighbor because you purple, green or orange. ... And so for me, I seen [sic] someone that was hurting, and did not need me to judge or pass judgment on them, show anger or be frustrated or mad at him. But I seen a young man in an unstable condition mind needing me to show him love.

If the law is a matter of attempting now how we shall live then, Ms. Tuff has a head start on…well, at least me.

The End is different than we expect, thank God.

“Keep all my commandments,” the Risen Jesus implores his church, “and, lo, I am with you always.”

One day, on the first day of the last future, it will be so.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

September 2, 2023

The Godless Crusade: Religion, Populism, and Right-Wing Identity Politics in the West

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here is a recent conversation I had with Tobias Cremer on his book The Godless Crusade.

Tobias is a Junior Research Fellow at Pembroke College, and an Associate Member of the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford. His research focuses on the relationship between religion, secularisation and the rise of right-wing identity politics. He is the co-author of Faith, Nationalism and the Future of Liberal Democracy (2021).

His book postulates that the rise of right-wing populism in the West and its references to religion are less driven by a resurgence of religious fervour, than by the emergence of a new secular identity politics. Based on exclusive interviews with 116 populist leaders, key policy makers and faith leaders in the USA, Germany, and France, it shows how right-wing populists use Christianity as a cultural identity marker of the 'pure people' against external 'others' while often remaining disconnected from Christian values, beliefs, and institutions. However, right-wing populists' willingness and ability to employ religion in this way critically depends on the actions of mainstream party politicians and faith leaders. They can either legitimise right-wing populists' identitarian use of religion or challenge it, thereby cultivating 'religious immunity' against populist appeals. As the populist wave breaks across the West, a new debate about the role of religion in society has begun.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers