The Paris Review's Blog, page 890

August 29, 2012

English Smocks

The Dead Preside

A few months ago, the first poetry reading I ever attended in New York came back to haunt me, almost literally. I was folding laundry on a Sunday night, listening to iTunes on shuffle, when a ghostly, familiar voice issued out of my speakers, interrupting the music. Soft, deeply resonant, and a little like Boris Karloff—or more precisely, Bobby “Boris” Pickett’s impersonation of Boris Karloff on “The Monster Mash”:

Samuel Menashe here. On June 19, in the year two thousand and one. In the city of New York, where I was born on September 16, in the year nineteen hundred and twenty-five. I am reading a selection of my poems from a book called The Niche Narrows.”

This time capsule–like announcement introduced a series of poems recorded by Menashe in some hermetic sound booth for the CD New and Selected Poems, released by Rattapallax Press in 2000. And listening to them gave me the most wonderfully uncomfortable feeling I’ve had since—well the last time I’d heard Samuel Menashe read. Which was more than five years ago. Read More »

In Memory of Daryl Hine

We were saddened to learn of the death of Daryl Hine last week at the age of seventy-six. Throughout the years, his work appeared with regularity in our pages, and his is a voice that will be greatly missed. The following poem appeared in issue 155.

A Rebours

Time’s one-way traffic won’t reverse

Summer’s sentimental course

Or force the headlong universe

Perversely backwards to its source.

Reverting to the title page

Cannot erase a book once read;

What echo of a golden age

Gilds an eternity of lead?

All the spontaneous happenings

Of the erotic pantomime.

Precipitate, straightforward lovers

Intimate that certain things

Are irreversible as time.

Bradbury’s File, The Unified Field

Seattle band Fleet Foxes is launching an arts and literary journal, The Unified Field . Quoth the L, “Round one features a journal entry penned by recently freed West Memphis 3 member Damien Echols on adjusting to life after eighteen years on death row, an excerpt from Gloria Steinem’s forthcoming book, a photo essay on adolescence by noted rock photographer Autumn de Wilde, a contribution from SPIN’s Charles Aaron, and another from Animal Collective sister/visual collaborator Abby Portner, among 30-plus other pieces.” Proceeds benefit nonprofit 826 National.

During the sixties, the FBI kept a file on suspected communist sympathizer Ray Bradbury. According to the bureau’s then-source, “some of Bradbury’s stories have been definitely slanted against the United States and its capitalistic form of governmental.”

Kindles don’t have a soporific effect according to one study: “a two-hour exposure to light from self-luminous electronic displays can suppress melatonin by about 22 percent … Stimulating the human circadian system to this level may affect sleep in those using the devices prior to bedtime.”

The Marriage Plot hits the small screen.

Across languages, “the fundamental colour hierarchy, at least in the early stages (black/white, red, yellow/green, blue) remains generally accepted. The problem is that no one could explain why this ordering of colour exists. Why, for example, does the blue of sky and sea, or the green of foliage, not occur as a word before the far less common red?”

August 28, 2012

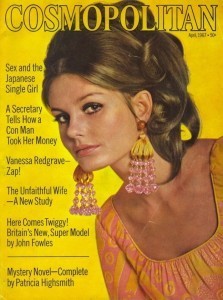

Gurley Girls

I was one of the last to get in on the sexual revolution, letting the other virgins sprint out of the starting gate ahead of me. Though sex wasn’t formally a competitive sport, in the sixties it could feel like a relay race with men and herpes being passed along by Team America. Cosmo girls were encouraged to be players—to experiment, seduce, and manipulate ... in no particular order. For seventy-five cents, we got monthly tips on being alluring and adventurous. Our coach was Helen Gurley Brown.

In those early days of Cosmopolitan, we ripped into each new issue to find out “How You Can Become a More Likeable, Secure, and Less Jittery Person ... and Change Your Life.” You might think that, having read that, you would never need another self-help article, but Helen Gurley Brown had endless ways of tapping into our self-doubts while simultaneously giving us license to lust. Virtue was no longer a virtue. The shame connected to sex that our mothers had tattooed on our DNA was suddenly spun on its head by a woman who never had a daughter. And maybe that’s why she made so free with recipes to heat up the bedroom, renovating what was done in bed the way Better Homes and Gardens had our bedrooms. We could now have orgasms along with mismatched bedside tables.

Even if we didn’t manage to snag one of the Bachelors of the Month, we might consider other options after reading, say, “The Undiscovered Joys of Having a Chinese Lover,” “Should You be Faithful to Somebody Else’s Husband,” “Buddy-Flirting—the Bold, New Way of Having Him Notice and Like You,” “Foot Fetishes: The Trade Secrets of the Sexiest Ladies in History,” and “When He Wants You to Make the Orgy.” Married women, often overlooked, could learn “How to Get Our Husbands to Love Us Like a Mistress.”

Heal Thyself

According to every epidemiological study of medical-student mental health ever published, a large percentage of us suffer from, well, something. The discussion sections of these research papers generally propose we educate one another in mental hygiene. They suggest we should practice more “mindful medicine.” And, good students, we oblige. A medical student may not come into med school knowing how to handle a “high-functioning” anxious type in clinic, but the diagnosis doesn’t require an office pamphlet. It’s visible right there in the room.

At my school, we first learn to integrate this understanding of acute and chronic anxiety into clinical practice via the required six-week psychiatry clerkship. Six weeks of immersion in “ICU psychiatry,” the psychiatry faculty argues, is not enough time to master the management of anxiety disorders, but at least it is something. Third-year medical students spend six weeks on one inpatient psychiatry ward as well as several night shifts in a CPEP (Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation Program), the ER for the ill at ease.

In these settings you learn to triage threat and fear until you know from anxiety. There you learn the difference between anxiety and agitation. Panic-attack patients stay in the ER for a while for cardiac and thyroid workups. Anxiety in the CPEP counts as psychosocial stressors, or Axis IV on the DSM-IV: losing your edge, losing your family’s support, your job your benefits, your place to live. Maybe you will have an adjustment disorder on Axis I, or existential anxiety that keeps you off your axis. Agitation is losing your cool, and sometimes losing your hospital gown if you’re especially feisty. For anxiety there is benzos and SSRIs; for agitation, benzos and antipsychotics and sometimes four point restraints. They call the agitation cocktail a 5+2, for 5 milligrams of Haldol and 2 milligrams of Ativan, though I saw one “frequent flyer” get a 10+4.

Fuzzy Austen, Tipsy Wilde

The literary felted dolls of My Cozy Classics are, quite simply, delightful. Above, a felted Elizabeth Bennett.

Norman Mailer, film director.

Exactly how Ladbrokes goes about determining their literary odds.

Drink like Oscar Wilde: strongly against your doctor’s orders.

The DNA of a successful book.

August 27, 2012

On Cataloguing Flaubert

Joanna Neborsky is a book lover’s illustrator. She may be as passionate and romantic about books and bookmaking as anyone I’ve met. She also draws the kind of pictures I’ve always wanted to make. They are deceptively simple due to the naive charm of each wobbly line, and they owe a great deal to the inspiration of mid-twentieth-century illustration—an obsession she and I both share. A few years ago Joanna and I collaborated on the cover of John Bowe’s Americans Talk About Love. A recent art school grad, she was willing to endlessly modify caricatures of the people interviewed for the book. The final package made for a witty and accessible take on social history. I always urge the artists I work with to keep me apprised of new projects, and so a few weeks ago I was tickled to discover a jpeg of Joanna’s poster “A Partial Inventory of Gustave Flaubert’s Personal Effects, As Catalogued by M. Lemoel on May 20, 1880, Twelve Days after the Writer’s Death” in my inbox. We had to share it with readers of The Paris Review, and now I wanted to share a little about how it came to be.

Power Lunches

As a penny-pinching undergraduate in New York, my idea of a power lunch was saving up for the Friday whitefish sandwich special at B&H Dairy on Second Avenue. Sitting alone on a vinyl swivel stool, I’d daydream about my boho-intellectual fantasy life, which involved large groups of opinionated writerly types laughing and arguing over exotic communal meals and bottomless tumblers of whisky, which I did not actually drink.

If my luncheonette-fueled fantasy was a bit overstuffed, at least it was rooted in historical accuracy: power lunches are an institution in New York, so much so that they warrant their own section in the New York Public Library’s new exhibit, “Lunch Hour NYC,” a retrospective of 150 years of lunch history and culture in the city. While the term power lunch didn’t officially appear in print until a 1979 Esquire article about the Grill Room at the Four Seasons (unfortunately, “America’s Most Powerful Lunch” is nowhere to be found online), the ritual itself has been an important part of the city’s lunch landscape for well over a century.

Lunch helped shape the rhythm of life in a rapidly industrializing New York at the turn of the last century: lunch breaks were hurried affairs, with rushed stops at quick-lunch counters in the early 1900s and Horn & Hardart automats a few years later. Time was a luxury, and leisurely midday meals were reserved for those wielding considerably political, financial, or social power. “Power lunches weren’t necessarily about exchanging money,” explains Lunch Hour cocurator Rebecca Federman. “They were about connecting with each other and exchanging thoughts, and there can be great power in ideas,” she says.

The earliest power lunches likely took place in the 1830s at Delmonico’s, whose culinary wizardry (Lobster Newburg, Baked Alaska) and prime location in the financial district made it popular with well-heeled suits. Apart from the occasional visit from such authors as Charles Dickens or Mark Twain, Delmonico’s remained largely populated by business and finance moguls. Other powerful groups gathered at different locales over the years: playwrights and actors descended upon Sardi’s in the theater district in the forties, while wealthy socialites clustered at Le Cirque, Le Pavillion, and La Grenouille in the fifties and sixties, earning the not-entirely-flattering nickname “ladies who lunched.”

For literary types, the lunch venue of choice was the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street. What would later come to be known as the Algonquin Round Table (or, as its members preferred, “The Vicious Circle,”) began in June of 1919, when Vanity Fair writers Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, and Robert E. Sherwood joined like-minded pals for a midday soiree to welcome back famously sharp-penned New York Times drama critic Alexander Wollcott from a stint as a World War I correspondent overseas. Theater agent John Peter Toohey had organized the lunch as a practical joke, ostensibly as a welcome home, but instead used the opportunity to roast Wollcott for failing to include one of his clients in a column. Legend has it that all attendees—Wollcott included—enjoyed the gathering so much they decided to do it again the next day, and the next, and the one after that.

Dining upon free popovers and celery sticks, or, in flush times, chicken hash with pancakes, the aforementioned writers—along with an ever-evolving cast that included playwrights George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly, columnist Heywood Broun, and author Edna Ferber—bantered and gossiped, played endless games of cribbage and poker, and devised elaborate practical jokes to deceive one another. Conversation was fast, clever and biting—hence the “vicious” nickname, though the Round Table moniker was widely used after a Brooklyn Eagle caricature depicted the group draped in armor around a circular table. (Not all were fans of the club: Groucho Marx, whose brother Harpo occasionally joined the group, distanced himself from the table, claiming “the price of admission is a serpent’s tongue and a half-concealed stiletto.”)

Of course, the Round Tablers also wrote—Kaufman, Connelly, and Sherwood all won Pulitzers for their work, and the Table’s wit was made famous nationwide in columns by Broun and Franklin Pierce Adams, who dutifully reported Tableside gossip in his “Conning Tower” column in the New York Tribune. Ernest Hemingway wrote his infamous “Baby Shoes” short story during a visit to the Round Table, collecting ten dollars apiece from the other writers who dared to bet he couldn’t write a complete tale in only six words.

But the most enduring legacy of the Algonquin Round Table was undoubtedly the creation of The New Yorker in 1925, the masterwork of editor and Round Table regular Harold Ross, who secured funding for the magazine at the hotel (to this day, Algonquin guests receive a complimentary copy of the magazine). Many Round Tablers contributed to the magazine, whose urbane, sophisticated tone mirrored the conversations at the Algonquin’s power lunches.

Over the course of the twenties, as its founding members moved on and away from New York, the Vicious Circle gradually disbanded (the hotel had long since stopped serving free popovers). The legacy of the Round Table has remained strong, however, in the generations since: in 1987 the Algonquin was designated as a New York City Historic Landmark, and in 1996 it was declared a National Literary Landmark by the Friends of Libraries USA.

And the history of the power lunch, too, continues today, albeit in less ostentatious incarnations: Federman suggests Union Square Café as a modern-day haunt for literary agents and authors, while Michael’s in Midtown has long been a favorite for publishing-world honchos. The perennially hip Momofuku restaurant empire—which last year launched its own food-lit magazine, Lucky Peach, in conjunction with McSweeney’s—now hosts a series of lunchtime discussions at its Midtown outpost, Ma Peche. Called the “56th Street Round Tables,” the forums are billed as “lunch and lively discussion, in the spirit of the Algonquin Round Table.” This month’s discussion, presented in conjunction with the library, concerned the history and legacy of street food in New York, with insight from Federman; Robert La Valva, the founder of the New Amsterdam Market; Jane Ziegelman, the curator of the Tenement Museum’s Culinary Conversations; and Zach Brooks, the founder of the blog Midtown Lunch.

The New Yorker’s midday meal, it seems, will continue its reign as the quintessential venue for the exchange of thoughts, ideas and power; to say nothing of the fare consumed. Perhaps for my next trip to B&H, I’ll split the sandwich with company.

Visit NYPL’s “Lunch Hour NYC” through February 17, 2013.

Jamie Feldmar is a Brooklyn-based writer and editor focused mainly on food, both professionally and personally.

The Beet Goes On, Chicken Soup for Soul and Stomach

Perhaps inevitably, Chicken Soup for the Soul is launching a line of seven soups, “led by iconic chicken noodle, made with tender chunks of chicken, egg noodles, and vegetables in a signature broth.”

In their annual Nobel Prize run-up, Ladbrokes favors Haruki Murakami at 7 to 1 odds.

The Shakespeare Insult Generator.

Ian McEwan: “Whenever I see the word beetroot it looks so appealing. The word looks its colour, so I’m going to have that.”

“One of Mr. Rutherford’s clients, who confidently commissioned hundreds of reviews and didn’t even require them to be favorable, subsequently became a best seller.” The business of raves.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers