The Paris Review's Blog, page 889

September 6, 2012

Radical Chic

Ida Wyman, “Spaghetti 25 Cents.” New York. 1945.

One day in late March, I took some pictures of the crowds of protestors in Union Square, newly arrived from Zuccotti Park. The week before, more than seventy protestors had been arrested, and the Union Square encampment evicted in a fashion many Occupiers described as gratuitously violent. Ramarley Graham had been killed about a month before, and the racially-charged practice of stop-and-frisk was asserting itself into mainstream consciousness. Trayvon Martin was now a household name. And since the previous August, one revelation after another had surfaced about the NYPD’s secret Muslim surveillance program. So people gathered on March twenty-fourth.

Tall, glittery women milled about with signs that proclaimed Social Justice is Fabulous!, at one point posing for a picture with veteran progressives whose cardboard read Protesting is not a crime it is a right!. One man held a white square above his head with red Chinese characters and their English translation in black: PROTECT HUMAN RIGHTS. PEACE FREEDOM DEMOCRACY. A LONG WAY TO GO. A young guy pontificated, a lit, dripping, hand-shaped candle his microphone. A “naughty policewoman” balanced on ice-skated toes, legs angled and baton in hand, her sign saying something about police wiping their collective ass with the Constitution. Former Police Captain Ray Lewis promoted the documentary Inside Job, while the Hare Krishnas, gathered in the square as usual, sang and danced in full force.

These pictures, I didn’t realize at the time, would be lost. Innocent of their fate, I took photographs that day as most people do, with the idea that this was not a test.

Thirty minutes after leaving Union Square, I arrived at the Jewish Museum, where The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 was on view for its last day in New York City. (The exhibit is currently at the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio, set to travel to San Francisco and West Palm Beach.) And while the sparse grandeur of Museum Mile was in contrast to the teeming crowd of Union Square, the trajectory felt logical.Read More »

September 5, 2012

Horror Story

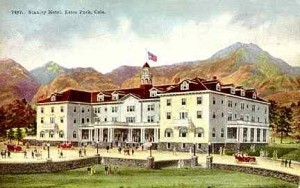

This month marks Stephen King’s sixty-fifth birthday. More than half a lifetime since he released The Shining, a novel inspired by the Stanley Hotel in Estes Park, Colorado. I’ve passed by the Stanley Hotel twice, between which two occasions I lived a scene that Stephen King himself could have written.

The first time, a Saturday morning a few weeks before my graduation from the University of Colorado, I was riding in my roommate Julie’s car toward a nearby hiking trail. The Stanley was grand, white, old-timey, and supposedly haunted, although not as isolated as the hotel in the movie. As we passed, our music playing, our ponytails blowing out the open windows, the Rocky Mountains rising like fists clenched in victory, I rested my feet on the dash, happy. Three years earlier, driving cross-country together, Julie and I had become best friends. Now, we hated separating even long enough to sleep. Every morning, we woke up, turned on TLC, one of the only channels we got, and danced together in our living room while watching shows about makeovers and brides. Throughout the day, unless we were in class, we were talking with each other. We believed that this was life. Once, a guy took us both on a date. “I thought I had to,” he told me later. In Julie’s car, the familiar smell of the interior soothed me. Out the window, the day was perfect, the sky huge. When it’s cloudless, a Colorado sky resembles a great, empty aquarium.

When we reached the trailhead to Gem Lake and stood stretching our hamstrings, a man sprinted down the trail, his backpack bouncing. When he saw us, he came to a halt and bent to rest his hands on his knees. He held up one finger, signaling us to wait while he caught his breath. This man was a typical Colorado sort—high socks and hiking boots, unruly gray beard, stocky calves. But there was nothing typical about what he told us: “Gunshot,” he panted, “by the lake.” He stood up straight and twisted to glance up the trail. Then he turned back to us. “I think she’s still alive,” he said. “I think she’s still twitching. Someone’s gotta get to her quick.”

Television Man: David Byrne on the Couch

I was born in a house with the television always on. The lyric comes from “Love For Sale,” a song penned by David Byrne and recorded on the Talking Heads album True Stories, but the same could be said for where I grew up, in suburban Philadelphia. My dad watched television even when cooking dinner, which seemed crazy to me, minding an open flame while keeping one eye on some “reality” courtroom drama—not sure you can rightfully call those staged scream-fests real. Judge Judy was such a constant presence, she feels like a family friend. I hear her gravelly voice chewing some idiot out and smell Dad's stir-fry.

I was born in a house with the television always on. The lyric comes from “Love For Sale,” a song penned by David Byrne and recorded on the Talking Heads album True Stories, but the same could be said for where I grew up, in suburban Philadelphia. My dad watched television even when cooking dinner, which seemed crazy to me, minding an open flame while keeping one eye on some “reality” courtroom drama—not sure you can rightfully call those staged scream-fests real. Judge Judy was such a constant presence, she feels like a family friend. I hear her gravelly voice chewing some idiot out and smell Dad's stir-fry.

Our house was small enough that, unless I played music, I couldn't escape the tube's empty murmuring, not even in my room, which abutted my parents'. As a teenager, then, it made sense that I'd fall in love with Talking Heads' song “Found A Job,” from their 1978 album More Songs About Buildings and Food. David Byrne, the band's vocalist, guitarist, and song-writer, doesn't so much sing as sing-narrates the story of a couple, Bob and Judy, frustrated watching television because “nothing's on tonight.” Byrne as narrator intrudes upon this domestic scene like one of those omniscient charlatans on infomercials—But wait! There's a solution to their problem!—suggesting they “might be better off... making up their own shows, which might be better than TV.”

By the song's end, Bob and Judy are collaborating, creating their own TV program, a show that “gets real high ratings.” They've saved their relationship and turned their whole lives around. “Bob never yells about the picture now, he's having too much fun,” the narrator tells us. He wraps it up like a fable, inviting the listener to “think about this little scene; apply it to your life. If your work isn't what you love, then something isn't right.” While Byrne tells the story, his guitar noodles on the edges of a funky, bass driven rhythm, until, at the end, a six note melody emerges like an epiphany over the groove. Bob and Judy have learned to sing a new tune.

September 4, 2012

Map Quest

The draw of the Yeah Yeah Yeah’s classic breakup song “Maps” is that it is as plainly sad as possible. “Wait,” the band’s lead singer, Karen O, sings over and over, “they don’t love you like I love you.” But “Maps” is also enigmatic: beyond its abject chorus, the lyrics are cryptic, with verses that are brief and opaque—“Packed up / Don’t Stray / Oh say, say, say / Oh say, say, say.” Karen O repeats maps, plaintive and without context, stretching the word’s aaa over four bars.

According to fan mythology, “Maps” is an acronym for “my Angus please stay,” referencing Liars lead singer Angus Andrew, whom Karen O has said the song is about. There may be other ways to read the song’s title, though. “Maps” evokes the physical and metaphorical distance that is felt from a lover who is leaving. It is a kind of emotional cartography, mapping two people’s painful journeys away from one another. This will serve as our foundation: maps aren’t impersonal, objective. They aren’t.

How Is the Critic Free?

A non-question has recently preoccupied the literary corners of the Internet: How rude should a book critic be? I call it a non-question because its non-answer is the same as for people in social situations generally: it depends. It’s impossible to find a universal rule that licenses rudeness. There’s always going to be at least one observer who feels that a conflict could and should be handled politely. (And who knows? Insofar as politeness is a skill, maybe there's always room for improvement.) Also, there’s always going to be at least one observer who describes as honest what others call rude. But even if you give up on unanimity and settle for a majority opinion, you still can’t formulate a general decision. Try it and see. Was William Giraldi justified in adopting a rude tone about Alix Ohlin’s novel? Was Ron Powers, about Dale Peck’s? Only the particular questions are worth debating, and no matter how many questions like them you answer, you never reach a rule that has the purity of math. The most you can hope for is etiquette.

Read More »August 31, 2012

John Jeremiah Sullivan Answers Your Questions

This week, our Southern editor, John Jeremiah Sullivan, stepped in to address your queries.

Dear Paris Review,

I live in the deep south and was raised in a religious cult.

Still with me?

Okay. I’m attempting to throw off the shackles of my religious upbringing and become an intelligent well-informed adult. My primary source of rebellion thus far has been movies. I would watch a Fellini movie and then feel suddenly superior to my friends and family because they only watched movies in their native tongue (trust me I know how pathetic this is). My main question involves my reading selections. Obviously, I have stumbled upon your publication and am aware of its status as the primary literary periodical in English. Also, I have a brand-new subscription to the New York Review of Books, since it is apparently the intellectual center of the English-speaking universe. I am not in an M.F.A. program or living in Brooklyn working on the Great American Kindle Single, I’m just a working-class guy trying to take part in the conversation that all the smart people are having. This brings me to my question: What books should I read? There are so many books out there worth reading, that I literally don’t know where to start. To give you some background info: I was not raised as a reader and was not taught any literature in the Christian high school that I attended. What kinds of books do I like? My answer to that would be movies. I’m desperate to start some kind of grand reading plan that will educate me about the world but don’t know where to start. The classics? Which ones? Modern stuff? Should I alternate one classic with one recent book? How much should I read fiction? How much should I read nonfiction? I went to college but it was for nursing, so I have never been taught anything about reading by anybody.

I realize this stuff may be outside of your comfort zone, as most of the advice questions seem to be from aspiring writers or college-educated people. Please believe me when I say that I am out of touch with the modern world because of a very specific religious cult. I want to be an educated, well-read, cultured, critically thinking person but need some stuff to read. Before I end this letter, I’ll provide an example of just how out of touch I am: you know how "Ms." is the non-sexist way to refer to a woman, and that "Mrs." is sexist? Yeah, I just found out about that. I’m twenty-five.

What We’re Loving: Stridentists, Oblivion

Of the first volume of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s long, uneventful bildungsroman, My Struggle, James Wood wrote, “Even when I was bored, I was interested.” Wood is a man who knows how to pay attention to long, boring books, even at times enjoys them, so I began My Struggle with trepidation; it was misplaced. The book kept me up till two almost every morning for a week. All the good things Wood says about the novel seem to me true; but I loved it even when the narrator slipped into clichés, because they made him seem that much more real and singleminded in his storytelling. I don’t read Norwegian, but it’s hard to believe that the translator, Don Bartlett, could have made such vital, humane prose—over such a long stretch—unless he was hewing close to a work of genius. —Lorin Stein

“Here’s my brutal / many-minded / poem / to the new city,” are the first words of Manuel Maples Arce’s “City: Bolshevik Super-Poem in 5 Cantos.” The poem was first published in Mexico City in 1924, and the subtitle isn’t entirely ironic. Another stanza begins, “Russia’s lungs / blow the wind / of social revolution / in our direction. / Literary dick gropers / will understand nothing.” I first read about Arce in Savage Detectives, where he is one of the deities in Bolaño’s pantheon of the Latin American avant-garde, identified as “the father of stridentism.” I thought this was a made-up group, but it really existed (that’s them, in the photo). They gathered in a café called Multánime (“many-minded”), where a contemporary reports that “the waiters placed their order via radio and the Pianola played music from intercepted Martian concerts.” —Robyn Creswell

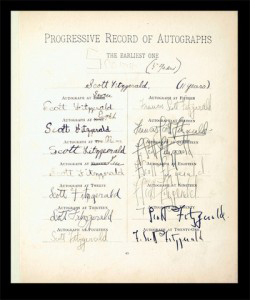

Signatures, Notes, and Lists

The evolution of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s autograph.

We have long been intrigued by the Strand’s “The Jean Files,” a series of notes, found in books, to a woman named Jean. The latest plea is especially intriguing.

Listen to Dylan Thomas read “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.”

Thank you to Iris Blasi for unearthing this vintage bit of Letterman, um, wit: Top Ten Bookstore Pickup Lines.

We may be biased, but are happy to disseminate the following: “According to a new study, people with an active interest in the arts contribute more to society than those with little or no such interest.”

August 30, 2012

Stuffed

Around Valentine’s Day, my gut finally confirmed what my head had long known: I would in fact be graduating from college in just three months, which meant that something would have to be done about the books.

This was in Philadelphia, in a large room on the second floor of a three-story house on Baltimore Avenue. Not wanting the hassle of selling a sofa or armchair at year’s end, I had furnished the room with little other than a bed, a salvaged nightstand, and a too-small desk borrowed from a friend’s girlfriend’s roommate. If it weren’t for the books (and the Robert Kennedy campaign poster that passed for decoration), a visitor to my room might surmise that its occupant tended toward a mildly disturbed kind of solitude. But there were books, lots of them. Books lined the mantel of the bricked-up fireplace. Books were stacked at the foot of the bed; they were strewn on the floor around the desk like a blast radius. Piles of books that frequently collapsed into small landslides annexed the nightstand. A stray book or two often lay on the floor in the middle of the room, the aftermath of hasty between-class transitions. For the first time in my life, I felt I had too many books.

You have to understand that like many bibliophiles, this was a Rubicon I never imagined crossing. In my experience, the adage “all things in moderation” carries much wisdom; until last winter, I thought books were an exception to this rule, occupying a higher moral plane than other things one might collect, like bottles of fine scotch or European football jerseys. In my reverence for the printed word, I subscribed to all the humanistic pieties: books as worlds between two covers, as food for the mind and soul, as a link between living and dead. Walking into Penn’s library every day for the last two years, I passed beneath a window bearing a breathless quotation from Samuel Daniel: “O blessed letters! That combine in one all ages past, and make one live with all!” The pane’s religiosity was apt; my faith in books had never been higher than in college. There, they protected me from the terrifying emptiness of Sunday afternoons, distracted me from one girl or another’s failure to return my call, and transported me from the campuses where I often felt I was merely playing at life, swept away from my old comfortable St. Louis existence because I needed a college degree. Books were the tributaries that returned me to the main current, if only for a few hours.

Bullet Points

1.

You will likely have noticed by now the writerly fashion of building an essay by numbered sections. These sections can vary from just a single sentence to many pages. Sometimes a section will bear one or more indentations or line breaks and will stretch into a mini-essay. Sometimes there will be as few as three sections and sometimes there will be more than a hundred.

Writers, such as God, have been numbering sections for a very long time indeed, and I do not wish to suggest that this technique is new, rather that it is increasingly used. My proof is a general sense that this is happening, nursed into conviction by a robust confirmation bias.

Two

Quite often these sections comprise a series of declarative sentences, near aphorisms, sayings that, breathed from the lips of drunks, would by most of us be taken in, swished around and then spat out.

III

These sections comprise wild declarative sentences, aphorisms, sayings that, belched from the throats of drunks, would be swished around and then spat out.

To take one example, “The only picture that it seems appropriate to paint in 2012 is a painting of people having their picture taken by famous paintings.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers