The Paris Review's Blog, page 886

September 20, 2012

Object Lesson: Classics

As you may recall from prior bulletins, in Object Lessons: The Paris Review Presents the Art of the Short Story, the editors approached twenty contemporary writers, presented them with our vast fiction archive, and asked them to write an introduction to their favorite short story. And did they deliver: the anthology is not just a great collection, but a veritable primer on what makes this medium work. Today’s quiz: Can you guess who wrote the following selection?

I always noted this tablet to the boys on their first day in my classroom, partly to inform them of their predecessor at St. Benedict’s, and partly to remind them of the great ambition and conquest that had been utterly forgotten centuries before they were born. Afterwards I had one of them recite, from the wall where it hung above my desk, Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” It is critical for any man of import to understand his own insignificance before the sands of time, and this is what my classroom always showed the boys.

Find out! And pre-order a copy today!

Fake Books, Fictional Detectives

“Would anyone go and ‘consult’ him? One feels not.” In a rediscovered Agatha Christie document, the author admits to a love-hate relationship with her creation, the debonair Belgian detective Poirot, and critiques other mystery writers.

The Marquis de Sade wanted even more days of Sodom? Unfinished novels of great writers.

“Wanting for some unknown reason to fill a space in his study with a selection of false books—complete with witty names he thought up himself—[Dickens] wrote to a bookbinder with a list of ‘imitation book-backs’ to be created specially for his bookshelf.” Now, the New York Public Library has re-created several of these fake books.

And speaking of the NYPL! Thanks to a donation, the library has reconsidered its controversial plan to relocate many of its books.

September 19, 2012

Open Sesame

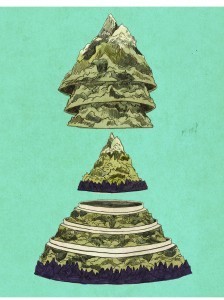

Artist: John Gagliano

A writer stands outside a story yelling, “Open Sesame!” and the story, as if a seed, opens. And treasure is found inside. That treasure, of course, is just another story, and it all begins again…

Or else, say the writer is no different from any other of his tribe—say he’s actually a thief. And the story is no story, but really a mountain. “Open Sesame!” (this writer continues)—the mountain opens and my meaning is revealed.

A version of this nonsense—this magician’s stage business—occurs in the tale “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves,” popularly known from the One Thousand and One Nights.

But Ali’s tale is not to be found in the oldest manuscripts of that collection. Some scholars believe it to be the invention of one Youhenna Diab, known as Hanna of Aleppo, an Arab Christian storyteller said to have communicated it to Antoine Galland, the first translator of the Nights into French. Others argue for a purely Western source, and believe that Ali is the incorrupt fiction of Galland himself (though Richard Burton, the first translator of an unexpurgated Nights into English, claimed that Ali was to be found in an Arabic original, a mythical manuscript often forged but never found).

A Week in Beirut

WEDNESDAY

I wake up early to make ice cream for an old friend who is visiting from Riyadh. I blow a fuse in the power converter getting the machine to turn fast enough, but I have a spare fuse and all is well. The visiting friend, Matt, flies in on Saudi Arabian Airlines, which is now a member of SkyTeam, so you can use your miles on Delta or Air France. That night, Matt, my wife, and I stay up late drinking beer and wine and telling stories about the life we shared in Riyadh, where my daughter was born and where Matt still spends weekends DJing parties.

THURSDAY

Matt and I follow the old coast road up to Byblos, where the ticket taker laughs when I say we met in Riyadh. He asks, “You are an American?” When I confirm, he says, “Ahlen Wa Sahlen,” which means “welcome.” Under a blazing September sun, Matt and I climb ten-thousand-year-old stairs, noting how few guardrails or official paths there are. Then I find a pomegranate tree growing from rocky soil, and we pause to admire the strange fruit hanging from gnarled branches. Hungry, we take a car to a fish restaurant that’s been open forty years. Lunch is grilled sea bass, which we eat on a table in the water, so that waves wash up our legs and sometimes splash on the fish, giving it a little more salt. Before we can leave, our waiter insists on my taking a shot. I ask for something brown, and he takes down a bottle of coffee-flavored Patrón.

FRIDAY

I make sure Matt sees this killer little cassette shop, Deep Music, which is just down the block from my apartment. Then we have a final lunch at a nearby restaurant, where they bake their own bread and many, if not all, of the salad greens are local and organic. We each drink a spicy pale ale, brewed by a guy I see around town, and then we share a bowl of merguez sausages drowning in sour syrup, and a seafood frikeh made with an intensely, earth-green grain.

Kids Are Alright, Like E-books

Onscreen writers “can be cynical hacks, genre stars or dislocated sportswriters. In romantic comedies, the writer is often a witty Lothario or a good-natured wimp. Either way, the profession’s primary function is to provide the character with plenty of free time.”

Jane Austen can stimulate brain function. Presumably, so can other authors.

“I am posting this for people who have Kindles, are in the U.S., and might want to get this. I am not posting this for people to tell me that they hate Kindles, hate all e-books, or are grumpy because they do not live in a country where they can download this.” Neil Gaiman makes a PA on Facebook.

You know who loves e-books? Kids.

As for the old-fashioned, paper kind, well, nowadays they’re less “reading material” and more

Object Lesson: Kings

The story so far: in Object Lessons: The Paris Review Presents the Art of the Short Story, we asked twenty contemporary writers to choose their favorite short stories from our fiction archive, and write an introduction. The result is a crash course in the short story, an introduction to some new authors and a reintroduction to others, and a terrific anthology.

Today’s quiz: Can you guess who wrote the following selection?

Today I have learned a great lesson; our cook was my teacher. She is twenty-five years old and she’s French. I discovered that she does not know that Louis-Philippe is no longer king of France and we now have a republic. And yet it has been five years since he left the throne. She said the fact that he is no longer king simply does not interest her in the least—those were her words.

And I think of myself as an intelligent man! But compared to her I’m an imbecile.

Find out! And pre-order a copy today!

September 18, 2012

Letter from Portugal: To a Portuguese Nun

Around the sixth day of my trip to Portugal, I forced myself to accept the fact that I would not be returning home with vast quantities of convent-made lingerie, replete with handwork and bobbin lace. Not, I assure you, for lack of trying. When something doesn’t exist, as a hundred thousand visitors to Loch Ness will tell you, finding it makes for very tough work.

Why the obsession, you ask? Well, I will tell you. First, I happened to reread Rebecca just before we left. Do you remember when Mrs. Danvers shows the narrator Rebecca’s exquisite nightdress, folded and left waiting for her in a silk case? “Here is her nightdress … how soft and light it is, isn’t it? … They were specially made by nuns of St. Claire.” This alone would have been enough to fire my imagination: this one garment, after all, serves as a symbol of Rebecca’s unattainable perfection: delicate, beautiful, worthy not merely of the most exquisite things but of the work it entails. Somehow both ethereally pure and erotically charged. A sex goddess blessed by Brides of Christ. No wonder the nameless narrator is intimidated.

Then, flipping through D.V., I ran across the passage wherein Mrs. Vreeland describes her London lingerie atelier:

The most beautiful work was done in a Spanish convent in London, and that’s where I spent my time. There was a brief period in my life when I spent all my time in convents. I was never not on my way to see the mother superior for the afternoon. “I want it rolled!” I’d say. “I don’t want it hemmed, I want it r-r-r-rolled!”

And a conviction grew in my breast: I would return to New York with a wearable piece of the Old World. Read More »

Dreaming in Welsh

Hiraeth.

It’s pronounced “here-eyeth” (roll the “r”) and it’s a Welsh word. It has no exact cognate in English. The best we can do is “homesickness,” but that’s like the difference between hardwood and laminate. Homesickness is hiraeth-lite. A quick history lesson is a good idea before a definition: in 1282 Wales became the first colony of the English empire. Because England eventually ruled half the globe, we all know its first colony by the name the colonizers gave it: Wales, which means “Place of the Others,” or “Place of the Romanized Foreigners.”

So that’s how the Welsh—the original Britons—became “foreigners” on their own island. Talk about a semantic insult. To Welsh speakers Wales is Cymru (pronounced Kum-ree): home of the Cymry, or fellow countrymen. But not too many schoolkids outside Llandysul know that. Arthur—the once-breathing chieftain, not Merlin’ s once-and-future pal—lived around the time the name “Wales” stuck, in the sixth century. He tried to hold back the English (really the Saxons) and failed. Then in 1282 Llywelyn failed too. He was the last Welsh-born Prince of Wales, aptly named The Last, and he was killed in battle by soldiers of Edward I. After that Wales became a subject state. Since then time’s centrifuge has spun it to the margins of history. Wales is a poor, rural place of mountains and ribboning hills with empty underground pockets where its coal used to be, but which, miraculously, has clung to its birthright language. Twenty years ago Welsh was spoken by eighteen percent of the population, mainly elderly folk in isolated areas. Today twenty-two percent speak it, including a burgeoning segment of young professionals who’ve helped create things like Gweplyfr (Facebook) and Twitr (Twitter).

An Object Lesson: Beware of Getting Out of Touch

Publisher’s Weekly called it “a kind of mini-M.F.A.”

In Object Lessons: The Paris Review Presents the Art of the Short Story, we asked twenty masters of the medium to choose their favorite short stories from our sixty-year archive, and write an introduction. The result is a series of “object lessons” in the art of short fiction, a look back at our incredible history, and, not incidentally, a terrific read.

Can you guess who wrote the following selection?

“Beware of getting out of touch,” his therapist had warned. “It happens gradually. It creeps over you by degrees. When you’re not interacting with people, you start losing the beat. Then blammo. Suddenly, you’re that guy in the yard.”

“I’m who?” asked Buddy.

“The guy with the too-short pants,” said the therapist.

Find out! And show your commitment to keeping the short story alive by pre-ordering a copy today!

Beat Letters, Literary Ink

Check out this letter from Jack Kerouac to his editor, in which the Beat presses for publication of On the Road.

Librarians with literary tattoos!

While we’re at it, writers in underpants. (No exclamation mark.)

Books You’ve Never Heard of By Authors You Have. (Spoiler: you may have actually heard of a few of them, but you get the idea.)

“An audio version [of Gravity’s Rainbow] does exist, though it came from the time of cassettes, not MP3s. The book was recorded in 1986 by George Guidall … it runs to 34 hours.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers