The Paris Review's Blog, page 882

October 12, 2012

Listen: Sylvia Plath Reads “Daddy”

Birthday Letter: Sylvia Plath and “Daddy”

Every morning, when my sleeping pill wears off, I am up about five, in my study with coffee, writing like mad—have managed a poem a day before breakfast. All book poems. Terrific stuff, as though domesticity had choked me.

—Sylvia Plath, letter to her mother, October 12, 1962

They were “dawn poems in blood,” those lines stormed onto paper while the children slept; several of them were written through fevers, and the heat seared onto the pages, those old memorandum sheets marked Smith College, or the back of a manuscript marked The Calm. That had been a radio play, drafted by Ted Hughes in their flat in London early the previous year; now Sylvia Plath was in the Devon farmhouse they’d bought soon afterward, and Hughes was back in London, banished, their marriage over. It was late 1962, and in the space of eight weeks, it brought Plath forty of what would become her Ariel poems. They were, she wrote to the poet Ruth Fainlight, “free stuff I had locked in me for years,” and now they were out. And they were astonishing. Only pain could have released them, only fury and outrage and jealousy and panic of the sort into which Plath’s daily universe had plunged. “I kept telling myself I was the sort that could only write when peaceful at heart,” she told Fainright, “but that is not so, the muse has come to live here, now Ted is gone.”

All of these poems would be in the black binder found in Plath’s London flat following her suicide just three months later, on February 11. They were poems so extreme they would be turned down by several magazines (only to become suddenly suitable for publication after the sensation of her death). Look how they came, one after the other, during that ferocious fall. September 26: “For a Fatherless Son.” September 30: “A Birthday Present.” October 1: “The Detective.” October 2: “The Courage of Shutting Up.” From October 3 to 10, Plath wrote her five bee poems, including “Stings” and “The Arrival of the Bee Box.” On October 10, “A Secret.” October 11 brought “The Applicant” (“It can sew, it can cook, / It can talk, talk, talk”). And fifty years ago today, on October 12, Plath sat down at the writing desk Hughes and her brother had made for her from a plank of elm, and she wrote her most famous poem. She wrote her father, and she wrote her festered grief, and she wrote her maddened Electra, and she wrote the unforgiving child who still ran riot in her veins; she finally got it down, so much of what had been propelling her from the moment she wrote her very first poem. “You do not do, you do not do”—what a line. What a spiel. What a fit of incantation. Whatever you think of “Daddy”—wherever you stand on the question of whether its tirades are transgressions, whether its swoop into Holocaust imagery is a mere looting and parading of angers not the poet’s own—there is no denying its extraordinary power. It stops the breath; it bothers the heart. What must it have been like, that morning, beneath the quaint thatch of that Devon farmhouse, for Plath to find herself writing this fireball of a poem?

October 11, 2012

The Modern Monastery: Pussy Riot in Prison

Philadelphia's Walnut Street Penitentiary

“Prison,” Nadezhda Tolokonnikova said in her interview with GQ, “is like a monastery—it’s a place for ascetic practices.” Member of the celebrated but incarcerated band Pussy Riot, Tolokonnikova gave voice to the belief that prison can be a soul-changing institution: an idea that inspired the American penal system.

The same year that America declared its independence from Great Britain, Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail opened. Its first major addition came in 1790 at the instigation of Quaker reformers who proposed “a penitentiary house” of sixteen individual cells for solitary confinement.

The penitentiary, unlike jails or prisons, set itself to the task of rehabilitating prisoners. Religious penance became the paradigm for criminal punishment; the monastic chamber served as the model for the prison cell. Walnut Street exemplified the philosophy of what became known as the Pennsylvania System, which separated prisoners from one another while enforcing silence and manual labor as mechanisms for transformation.

Drink the Water

Liquor has never touched my Middle Eastern father’s lips. Or so he claims. In the late sixties, when he lived a spell in Munich, embarked on spontaneous sojourns to Italy, and dated a Finnish broad named Helvi I once saw in a faded wallet-size photo—activities that made him sound so much more alluring than the stern killjoy I remember—I like to think he nursed a few carefree beers just like any lonely expat. When he made his way to New York a few years later, renting a dingy studio on the upper reaches of Broadway, when he was still the man my mother fell for—an Arab version of Adrian Zmed with a rustling gold chain around his neck and swarthy looks that back then meant you were handsome, not a possible terrorist—he used to smoke cigarettes, my mother tells me. Perhaps he also took nips of whiskey from a flask.

But the only father I know, the real one, returned from a trip to Saudi Arabia when I was eight years old a sudden gung-ho Muslim. He was no longer the aggressive moderate who was content with me just saying Bissmilah at the start of each meal. Now, every moment he wasn’t holed up in a Hilton for work or stuffing fried eggplant into pita bread at the dinner table was spent hunched over a miniature Koran, recapturing the lost Islam of his youth, of his family, of the native Syria he hadn’t called home for more than two decades.

Freshly brewed mint iced tea. Distilled water from the Poland Springs gallon bottles that lined our laundry room. Dr. Pepper, when its effervescence became a salve for the wheezing that permeated my bronchitis-ridden childhood. These were the beverages welcome in our teetotaler home. Although my mother, a Catholic girl from Queens, didn’t have religion propelling her consumption habits, she harbored something worse: distaste for even innocent bubbles. “Champagne burns my ears,” I remember her whining—and she rarely invited company over for anything more than a cup of Earl Grey.

Mo Yan Wins the Nobel Prize for Literature

Chinese author Mo Yan—whose pen name translates to Do Not Speak—has won the 2012 Nobel Prize for Literature. A short-story writer and essayist who, says the Nobel citation, “with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary,” Mo Yan said he was overjoyed and scared by the honor.

Continued the citation, “Through a mixture of fantasy and reality, historical and social perspectives, Mo Yan has created a world reminiscent in its complexity of those in the writings of William Faulkner and Gabriel García Márquez, at the same time finding a departure point in old Chinese literature and in oral tradition.”

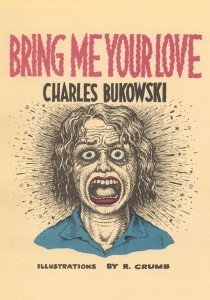

Crumb on Bukowski, Rushdie on James

A match made … well, you decide where! R. Crumb illustrates Charles Bukowski.

How to survive an online pan: in this case, persuade the author to remove it.

A history of cricket in literature.

A new attempt at a Breakfast at Tiffany’s musical is headed for Broadway.

“I've never read anything so badly written that got published.” Salman Rushdie on Fifty Shades of Grey.

October 10, 2012

See You There: The Paris Review at the Strand, Tonight!

Join us at the Strand tonight for another installment of our reading series. Readings by actor and filmmaker Alex Karpovsky, currently on HBO’s Girls, and author Ben Marcus, a contributor to our new anthology, Object Lessons. Wine will be served.

Wednesday, October 10, 7 P.M. to 8:30 P.M.

The Strand Bookstore, third-floor Rare Book Room

828 Broadway at Twelfth Street

Admission: Buy a copy of the current Paris Review or a $10 Strand gift card.

To reserve your seat, click here.

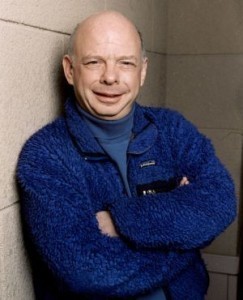

Wallace Shawn Reads Denis Johnson

Listen to a preview of the inimitable Wallace Shawn read from Denis Johnson’s “Car-Crash While Hitchhiking,” one of the stories included in the new anthology, Object Lessons.

The full audio recording will be available shortly in a new book, Three Stories: An Audio Book, only available on the Paris Review app.

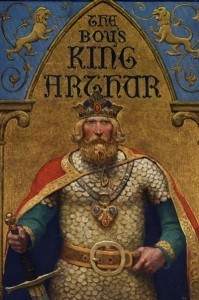

Arthurian Legend, Literary Restaurants

Oxford’s Bodleian Library has put more than three hundred thousand rare books online.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s previously unseen two-hundred-page Arthurian epic poem, The Fall of Arthur, will be released next May. His son has acted as editor.

As I Chipotle Dying: the #literaryrestaurants hash tag sweeps Twitter.

Lena Dunham’s purported $3.5 million sale prompts a list of outrageous book deals.

“Lolita, then, is undeniably news in the world of books. Unfortunately, it is bad news. There are two equally serious reasons why it isn’t worth any adult reader’s attention. The first is that it is dull, dull, dull in a pretentious, florid and archly fatuous fashion. The second is that it is repulsive.” The New York Times’s pan: just one of the bad reviews received by classics.

October 9, 2012

Crossroads of the (Art) World

Views of the Time Square Show (organized by Colab), 1980. Photo collage by Terise Slotkin

At what date on the calendar, at what precise location, did counterculture become pop culture? And who do we mark down in the history books as the hero, or the villain, who masterminded the switch? There is an answer: “The Times Square Show.” In June of 1980, more than a hundred artists, under the auspice and directed by the vision of Colab (Collaborative Projects), took over a four-story building on Forty-first Street and Seventh Avenue and mounted a two-month exhibition. There were big names: Tom Otterness, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kiki Smith, Jenny Holzer, Kenny Scharf, Nan Goldin. But, already, this is a wrong turn; the notion of individual heroism, of the creative ego that strives for and achieves recognition—in other words, a modernist view of the artist—is an anachronistic way to view “The Times Square Show.”

Time Square Show (organized by Colab), map of the first and second floors with list of participating artists. Floor plan by Tom Otterness, notations by John Ahearn

The idea behind “The Times Square Show” was different: a collaborative, self-curated, self-generated group show that transcended trappings of class and cultures. As John Ahearn, a Colab initiator who spotted the location on a Times Square jaunt with Tom Otterness, told the East Village Eye, “Times Square is a crossroads. A lot of different kinds of people come through here. There is a broad spectrum, and we are trying to communicate with society at large.” Ahearn went on to tell the Eye, “There has always been a misdirected consciousness that art belongs to a certain class or intelligence. This show proves there are no classes in art, no differentiation.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers