The Paris Review's Blog, page 880

October 22, 2012

Heroine Worship: Talking with Kate Zambreno

Kate Zambreno’s first book, O Fallen Angel, won Chiasmus Press’s “Undoing the Novel” First Book Contest, and her second book, Green Girl, was a finalist for the Starcherone Innovative Fiction Prize. So it should come as no surprise that her provocative new work, Heroines, published by Semiotext(e)’s Active Agents imprint next month, challenges easy categorization, this time by poetically swerving in and out of memoir, diary, fiction, literary history, criticism, and theory. With equal parts unabashed pathos and exceptional intelligence, Heroines foregrounds female subjectivity to produce an impressive and original work that examines the suppression of various female modernists in relation to Zambreno’s own complicated position as a writer and a wife. It concludes by bringing the problems of the modernists into conversation with the contemporary by offering a timely consideration of the role of the Internet and blogs in creating a community for women writers.

What was it about the modernist wives that first interested you?

I think I came to the wives through an initial discovery of more neglected modernist women writers—Olive Moore, Anna Kavan, Jane Bowles, maybe I’d add Jean Rhys to that list. I was living in London working in a bookshop and not doing much in terms of trying to write a novel, so I pitched to Chad Post at Dalkey that I write an essay on Kavan. And because I had nothing else to do, I sat in the British Library and read everything by her. And started reading all these other experimental women writers, like Elizabeth Smart—not the Mormon abductee, but the one obsessed with the poet George Barker, an obsession she documents in the amazing By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept. Not a modernist, I know, but I sat at the British Library and read the communal notebook she kept with Barker and thought about Vivien(ne)’s hand on “The Waste Land” manuscript. I began to be really interested in ideas of literary collaboration.

The Paris Review App

Have you heard the news? Two weeks ago we launched our very own iPad/iPhone app, which features new issues, rare back issues, and archival collections—along with our complete interview series and the Paris Review Daily. And best of all, it’s free!

Have you heard the news? Two weeks ago we launched our very own iPad/iPhone app, which features new issues, rare back issues, and archival collections—along with our complete interview series and the Paris Review Daily. And best of all, it’s free!

The New York Daily News called it “a real treasure”; Gizmodo named it app of the day; and The Rumpus recommends it over an M.F.A.!

Current print subscribers, you’re in luck: we’ve granted free digital access to any issue covered by your print subscription! If you’re a print subscriber and haven’t already heard from us, send us an e-mail at support [at] theparisreview.org.

To those with Android devices: we hope to have a version for you soon!

Literary Salons, Unfilmable Books

The Cleveland Public Library introduces a new library card commemorating the life of Cleveland-based author, film subject, and misanthrope Harvey Pekar. The Pekar-edition card will be available from this month at branches of CPL.

Everyone’s a salonniere: Louis Vuitton has started a Parisian literary salon. Well, sort of. It also sells stuff. And will later be incorporated into the LV boutique, so.

“I start a book in 1978 and finish it 34 years later, without enjoying a single minute of the enterprise.” Joe Queenan’s reading habits.

The alternative approach: how to talk about books you haven’t read.

Allegedly unfilmable books.

October 19, 2012

Finnegans Wake: An Illustrated Panorama

I wanted to illustrate something impossible, so I chose Finnegans Wake. It would be silly for me to draw in a few panels a work that took James Joyce seventeen years to complete. So I cheated.

The name of the book comes from a nineteenth Century drinking song, “Finnegan’s Wake” (note the apostrophe). The song is about death and rebirth, and ends in a whisky-fueled brouhaha. There is little in agreement, on the other hand, on what Joyce’s book is about. Reading a page at random from Finnegans Wake is a bit like trying to read while drunk. But death and rebirth are undoubtedly major themes, as the book begins halfway through its final sentence. So here’s a single strand of DNA—perhaps the first—in Joyce’s impossibly dense opus infinitum.

Jason Novak works at a grocery store in Berkeley, California, and changes diapers in his spare time.

What We’re Loving: Angry Generals, Contemptuous Gumshoes

Several of us are in San Francisco at the moment. As such, I am obviously revisiting that hard-boiled Fog City classic, The Maltese Falcon. How can you beat it? “Spade took her face between his hands and he kissed her mouth roughly and contemptuously. Then he sat back and said: ‘I’ll think it over.’” —Sadie Stein

This week I’ve returned to The Coal Life, the 2012 debut collection from Birmingham Poetry Review editor Adam Vines. And it’s still staggeringly good. Vines has this way of delivering a deliciously playful line with a face so straight you feel like a fool for thinking words could work any other way. Check out “River Politics” over at Poetry for a prime example, and then spring for the full set. —Samuel Fox

007, Moby-Dick, Literates

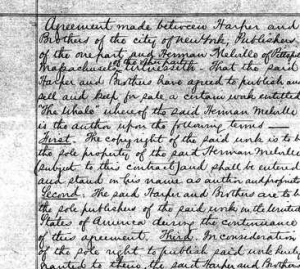

The handwritten contract for Moby-Dick.

The top ten literary parodies! (Warning: highly subjective and skews very British. But then, it would.)

Watch the trailer for Midnight’s Children. In the words of one YouTube commenter, “can b a gud movie for literates.”

In news that will shock no one, Swedish researchers find writers are unusually prone to depression, mood disorders, and substance abuse.

The Economist charts the kills, conquests, and tipples of the various James Bonds.

October 18, 2012

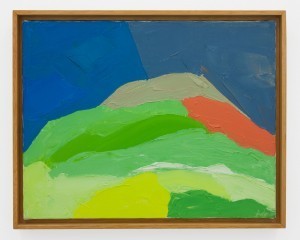

Sea and Fog: The Art of Etel Adnan

Etel Adnan wasn’t there. “It’s hard for her to travel these days,” Photi told me. Too bad, I thought. She is an iconic Lebanese-American cultural figure and I had hoped to meet her. She was also missing out on the impressive turnout in her honor in New York’s Lower East Side.

I had arrived just as the reading had started. The tiny gallery was packed, and I had to squeeze my way through the many bodies. Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, an art critic, was already speaking. I was surprised she was there. She lives in Beirut; I lived there once. So did Etel. Etel and I were both born there, albeit forty-five years apart. And we were both there during the fifteen-year Lebanese Civil War (she, here and there; me, throughout much of its first ten years). Etel wrote the defining novel about that war, in 1978. It’s called Sitt Marie Rose and is based on the true story of a woman who was kidnapped and killed by the Christian Phalangists for her support of the Palestinian cause. The Phalangists were one of innumerable militias during the war; they ruled East Beirut, where I, a daughter of two Palestinians, lived. The book was translated into dozens of languages and is regarded as an important contribution to Arab feminism.

Kaelen was holding Etel’s new book, Sea and Fog, in her hand. It’s a book of prose and poetry that had just been released by Nightboat Books, a small, independent press from Callicoon, New York. It was originally written in English, Etel’s first language these days. She penned it in California, where she has been based for decades. (Etel also spends part of the year in Paris.)

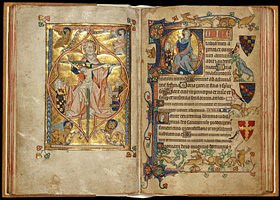

At Callicoon Fine Arts, the small, independent gallery where we were standing, Photios Giovanis, the gallery’s owner, was showing Etel’s paintings. I had never seen Etel’s art in person before. Until very recently I didn’t even know she was an artist. I only knew her as a writer. As Kaelen spoke, I swiveled left and right, trying to get a glimpse of the works, but there were too many heads in the way. “Whenever I’m hanging out with a group of artists in Lebanon and Etel comes in, everyone is like ‘Oh, here’s Etel.’ She’s a very influential figure,” Kaelen, said. Kaelen hangs out with Lebanese artists often. She knows the Lebanese art scene very well. She writes about it for publications like Bidoun, Frieze, and Artforum. I don’t, in fact, know where Kaelen is from. But she writes great articles about Lebanese art. They almost all have the same theme: Lebanon is an insane, unruly, unstable place—but it has great artists.

As Long As It Was Deep

Mimes, Tattoos, and Whales

The Mime Alphabet Book and other odd titles.

Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies: Man Booker Prize winners and now BBC miniseries and stage plays, too.

This children’s librarian has perhaps the ultimate children’s librarian tattoo.

A slide show of Robert Frost’s Vermont home.

Moby-Dick gets the Google treatment.

October 17, 2012

Chamber of Secrets: The Sorcery of Angela Carter

Illustration by Igor Karash

Fairy tales were reviled in the first stirrings of post-war liberation movements as part and parcel of the propaganda that kept women down. The American poet Anne Sexton, in a caustic sequence of poems called Transformations, scathingly evokes the corpselike helplessness of Sleeping Beauty and Snow White, and scorns, with fine irony, the Cinderella dream of bourgeois marriage and living happily ever after: boredom, torment, incest, death to the soul followed. Literary and social theorists joined in the battle against the Disney vision of female virtue (and desirability); Cinderella became a darker villain than her sisters, and for Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, in their landmark study The Madwoman in the Attic, the evil stepmother in “Snow White” at least possesses mobility, will, and power—for which she is loathed and condemned. In the late sixties and early seventies, it wasn’t enough to rebel, and young writers and artists were dreaming of reshaping the world in the image of their desires. Simone de Beauvoir and Betty Friedan had done the work of analysis and exposure, but action—creative energy—was as necessary to build on the demolition site of the traditional values and definitions of gender.

Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers