The Paris Review's Blog, page 877

November 1, 2012

Happy November!

Bookstores Take a Beating, and Other News

Brooklyn's Powerhouse Books, post-Sandy

How did bookstores fare in the wake of Hurricane Sandy?

A sad reality for many right now: how to care for water-damaged books.

The (thankfully unscathed) New York Public Library has waived fines ... until November 8.

Many independent bookstores are refusing to stock books from the Amazon imprint.

The Proper Art of Writing: a compilation of all sorts of capital or initial letters of German, Latin and Italian fonts from different masters of the noble art of writing.

October 31, 2012

Circus and the City: New York, 1793–2010

As we—like Lady Justice at her scales—weigh the virtues and policies of our presidential candidates, our very future in the balance, it is perhaps not without merit to reflect upon the classical history of democracy, and a fledging nation, now great, which has taken up a banner of representative government as passed down from the Greeks and Romans of antiquity. Perhaps, as well, as the airwaves are electric with the storied truths apropos to this most momentous of elections—this cotterpin in the history of humanity, perhaps the very universe, this year of destiny, of DECISION 2012!—we might look to the birth of our comedic and dramatic tradition, which we will find in the Dionysian festivals of Ancient Greece. Or, wait, is it more of a circus?

Circus it is. Hollywood may claim Aristotle as a father, and Washington may fancy itself an ancestor of the Roman Republic, but don't we all know that our truer father is P. T. Barnum—tabloid king and political boss—and that our truer tradition is the circus, three rings?

“Nixon & Co.’s Mammoth Circus: The Great Australian Rider James Melville as He Appeared Before the Press of New York in His Opening Rehearsal at Niblo’s Garden,” 1859. Poster, printed by Sarony, Major, & Knapp, New York. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

1797

1796, Captain Jacob Crowninshield, future congressman, speculates upon the transport of a Bengal elephant. Upon arrival in New York Harbor, Crowinshield is rewarded with an unheard of bid: $10,000. With that, the posters and handbills are printed, and the show is on. The elephant is on display on the corner of Beaver Street & Broadway. “Admittance one quarter of a dollar—children one eighth of a dollar.”

“The Elephant,” 1797. Broadside with woodcut illustration, printed by William Barrett, Newburyport, Massachusetts. Collection of The New-York Historical Society.

1835

The American circus married the British equestrian display (which had added acrobats, clowns, and other traveling and fair performers) to the Americanism of exotic animal exhibitions, or menageries.

“It is a season of still deeper excitement, in such a retired country village, when once a year, after several days’ heralding a train of great red wagons is seen approaching, marked in large letters, CIRCUS, 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on. This arrival has been talked of, and, produces an immediate bustle and sensation. Fifty boys breaking loose from school, rush immediately to the street, and in treble tones cry ‘Circus!’” —The Knickerbocker, 1839

“Magnanimity of the Elephant Displayed in the Preservation of his Keeper J. Martin, in the Bowery Menagerie in New York,” 1835. Etching and aquatint. Somers Historical Society, Somers, New York.

Circa 1846

Isaac Van Amburgh (1811–1865, the surname was the invention of his Native American grandfather) found inspiration in the biblical tale of Daniel and the lion’s den. Van Amburgh found employment and eventual fame in North Salem’s Zoological Institute of New York, which was not a scientific venture, but a brand/franchise of small menageries. (The Zoological Institute was initiated at the Elephant Hotel, owned by Hachaliah Bailey, of the future Barnum & Bailey Circus.) Rising from cage-cleaner to chief attraction, to favorite of Queen Victoria, Van Amburgh emphasized the danger and ferocity, and man’s dominion over the beasts. “The Lion King” dared to walk into a cage with wild cats, and put his head in the lion’s jaw.

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer. “Portrait of Mr Van Amburgh, As He Appeared with His Animals at the London Theatres, 1846–47.” Oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

1853

The circus—as theatrical mainstay or touring spectacle—continued to evolve and gain currency in the rapidly populating cities of the United States. With the innovation of the tent, 1826, the circus found the rest of the nation.

“The Circus is a national institution. Though originating elsewhere, and in ages long previous to the beginning of History, it has here reached a perfection attained nowhere else.” —Walt Whitman, 1856

“Exterior View of the Grand Pavilion of Franconi’s Hippodrome, Covering an Area of Two Acres, as it Appears When Erected for Public Exhibition,” 1853. Tinted lithograph, printed by Sarony & Major, New York. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

1858

The calliope—a clamorously loud steam organ—was first adapted for circus use in 1857. The calliope originated in locomotive whistles, and was readily implemented by riverboats, which were also steam powered. The circus calliope, or carousel, was an apparatus entirely proclamatory, and drawn by horses. The calliope procession, which could be heard for miles around, announced the arrival of the circus through the nineteenth century.

“Grand Procession of the Steam Calliope Drawn by a Team of Six Elephants in the City of New York. Now Attached to Sand’s, Nathan’s & Co.s American & English Circus,” 1858. Color lithograph poster, printed by Sarony, Major & Knapp, New York. Collection of The New-York Historical Society.

Circa 1860

Barnum’s attractions spanned biblical tales to minstrel routines to strange science to temperance shows to live animals to “freaks.” The freaks came in two varieties: those born (Siamese twins, albinos, giants, etc), those made (the often eroticized tattooed ladies, strong men, “Circassian Slaves”). A third variety, the exotics—“Wild Men,” “Missing Links”—emerged in the later years of the nineteenth century.

“Vantile Mack, The Infant Lambert, or Giant Baby!!,” ca. 1860. Hand-colored lithograph, printed by Currier & Ives. © Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont.

1875/1879

In 1868, P.T. Barnum’s American Museum burned down for the second time. Barnum, who was active in politics, vowed retirement from show business. But in 1871, Barnum pitched a new tent, this time in Brooklyn: “P. T. Barnum’s Great Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Hippodrome.” At only fifty cents, the ticket offered a wealth of entertainment. Taking to the railways, “the Greatest Show on Earth,” marked the onset of what is now termed the “Golden Age” of the U.S. Circus.

“I Am Coming,” 1875/1879. Framed poster with woodcut illustrations, printed in two colors, inset portrait of P. T. Barnum engraved by Mayes; border by Roylance & Purcell, New York. Hertzberg Circus Collection of the Witte Museum, San Antonio, Texas.

1882

The “big four” circus animals, that is to say the animals that any respectable circus would have, were the elephant, the giraffe, the hippopotamus, and the rhinoceros. When Barnum purchased Jumbo, a large African elephant, from the Royal Zoological Society in London, for the sum of $10,000, British public sentiment weighed in—their elephant must stay!—and Barnum seized the opportunity. Jumbo would be Barnum’s greatest earner. As marketed, the family friendly giant, upon his arrival in New York in 1882, set off a “Jumbomania.”

“Jumbo the Children’s Giant Pet,” 1882. Poster, printed by the Hatch Lithographic Company, New York. Collection of the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Tibbals Collection.

1885

In 1885, while walking in a railway yard, Jumbo was struck by a train and fatally injured. The death did not stop the ballyhoo; Barnum claimed that Jumbo had given his life in an attempt to save the life of Tom Thumb, a young circus elephant. Through the 1886 season, Barnum displayed Jumbo’s skeleton; a headline in the New York Times assessed: “Jumbo Stuffed a Greater Attraction than Jumbo Alive.” Jumbo’s skeleton is currently in the possession of the American Museum of Natural History, where it is occasionally displayed.

Souvenir cross-section of Jumbo's tusk, 1885. Ivory, ink. Circus World Museum.

1900

The first Madison Square Garden, so named for its location—on Twenty-Sixth Street near Madison Square—was an open arena built with circuses in mind. The second incarnation of the Garden soared to thirty-two stories, and boasted its own theater and concert hall, a roof garden, the largest main hall in the world, and the largest restaurant in the city. It was here in 1919 that the “Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus” made its debut; the show merged the nation’s two largest circuses.

Madison Square Garden III would come in 1925, followed by the current Madison Square Garden, which would break ground in 1968. The Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus of the Madison Garden III era hoped for a boost from Cecille B. DeMille's 1952 film, The Greatest Show on Earth, and the draw of celebrities; Marilyn Monroe opened the 1955 show. Through the 60s and 70s, economic instability and a distrust of conventional entertainment dampened enthusiasm for what had become a bloated, indoor moneymaker.

“Every country gets the circus it deserves. Spain gets bullfights. Italy the Church. America Hollywood.” —Erica Jong, 1995

“Forepaugh & Sells Brothers Enormous Shows United. Madison Square Garden New York / The World Famous Metropolitan Home of These Combined Stupendous Shows,” 1900. Poster, printed by the Strobridge Lithographing Co., Cincinnati & New York. ˝ Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont.

1905

Circuses were not integrated workplaces—not until 1968 did Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus feature its first African American act, the King Charles Troupe (basketball-playing unicyclists). But as of the latter half of the nineteenth century, with the influence of minstrel and Vaudeville performance, African American musicians and performers were popular sideshow attractions.

Frederick Whitman Glasier. Sideshow band, ca. 1905, printed 2009. Print from a glass plate negative. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Glasier Glass Plate Negative Collection.

1910

In “Frog’s Paradise,” husband and wife “benders,” Harry DeMarlo (born James Dwight Morrow, 1882–1971) and Friede DeMarlo (born Gobsch, 1890–1980) performed aerial and contortion stunts in cumbersome paper mâché frog heads. (A full costume is on exhibit at the Bard exhibition.)

With the turn of the century “thrill acts,” circuses promoted billings of life-defying danger. In the “Whirl of Death,” Friede gripped a leather bit in her teeth, and was spun as high as 100 feet in the air by a powerful electric motor. In 1927, the electricity gave out while Friede was on the Whirl. The London News featured the story: “La Marletta, The Human Top, Crashes To The Ground At The London Olympia ... taken to the West London Hospital at Hammer Schmidt Crossing. Fearful accident. Women in audience screamed in panic and a great number fainted away, many others hurried out.” After a brave recuperation, Friede returned to the Whirl, but the electric motor was replaced by a more reliable (but still persnickety) system of uncoiling rope.

Harry and Friede De Marlo. Photos ca. 1912.

1913

The lineage of the grand spectacle traces to theatrical pageants, the European art of pantomime, and the tableau vivant of France. The early twentieth century circus returned to the form in august style; but the “spec,” as it was known in circus parlance, owed as much to the developing consciousness of film as to performative tradition. Historical reenactments of a previously unimagined scope had become a reality in 1908’s La Mort du duc de Guise, two versions of The Three Musketeers (1903 and 1911), 1911’s A Tale of Two Cities, and other early silent era films.

“Ringling Bros. Magnificent 1200 Character Spectacle / Joan of Arc,” ca. 1913. Color lithographic poster, printed by the Strobridge Lithographing Co., Cincinnati & New York. © Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont.

1913

May Wirth (1894–1978), a second generation circus performer, astounded audiences with her “Back Across,” which landed her, via backwards somersault, on a horse that closely followed her own. Her billing, as “the world’s greatest female bareback rider,” was, in the estimation of her spectators, deserved. In 1920, the New York Times echoed the sentiment: “when P. T. Barnum, or Mark S. Orelius or whoever it was said: ‘There is nothing new under the sun,’ Miss Wirth had not been born. Otherwise he would not have said it.”

May Wirth’s “back across,” 1913. Photograph. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida.

1915

A sideshow banner by Siegmund Bock, an early and influential painter in the oeuvre.

Siegmund Bock. “Miss Louise and Her Den of Alligators,” ca. 1915. Sideshow banner, painted canvas. Circus World Museum, Baraboo, Wisconsin.

1936

The Federal Government stepped in to keep the New York circus alive during the depression. Under the auspice of the Federal Theatre Project, the WPA Circus employed 375 performers, and entertained millions of New Yorkers, 1935 to 1939.

“The World’s Greatest Circus / Under the Big Tent… Schley Ave. at E. 177th St., Bronx…,” 1936. Silkscreen poster, printed by the Poster Division, Federal Theatre, New York City. Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

1940-50

Felix Adler (1895–1960), with a tenure of fifty years at the Barnum & Bailey Circus, was the quintessential sad clown. The “King of Clowns,” as he was known, believed that comedy and tragedy were inextricably entwined, and embraced improvisation and accident. During the course of one performance, Adler and his mule toppled in a heap, and Adler was unexpectedly treated to the presence of a mule sitting in his lap. It was a gloriously hilarious moment, but, as Adler opined to the New York Times, “of course, not for love, oats or sugar could I ever get that mule to sit in my lap again.”

“A national political campaign is better than the best circus ever heard of, with a mass baptism and a couple of hangings thrown in. I confess I enjoy democracy immensely. It is incomparably idiotic, and hence incomparably amusing.” —H.L. Mencken on the 1952 presidential election.

Birdcage hat worn by Felix Adler, ca. 1940-50. Circus World Museum.

1943

Influenced by the New York World’s Fair, the struggling Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus undertook a total makeover. In 1941, the circus recruited Norman Bel Geddes, who designed the Futurama exhibit of the World’s Fair, to oversee a new look for all aspects of the show, promotion, and performance. Bel Geddes, who had Broadway experience, took Mother Goose as his cue.

Lawson Wood. “Ringling Bros / Barnum & Bailey” with monkey band, 1943. Color lithograph poster. © Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont, Gift of Harry T. Peters Sr. Family.

1968

In 1967, John Ringling North sold the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus to a consortium of investors led by music promotor Irving Feld. Purchase price: $8 million. Feld promptly revamped the show, and instituted the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus Clown College.

Circus animals on 33rd Street, April 1968. Photograph. © Bettmann/CORBIS.

1977

The three-ring experience of Ringling Brothers was spectacular, but it had lost much of the original funky fun of the tent and small theater circus. Through the 1970s, a surge in New York circus arts coincided with a surge in New York performance art. In 1974, in a guerrilla thrill act, french highwire artist Philippe Petit spanned the Twin Towers by cable. The daredevil routine delighted New Yorkers, even the police. In 1977, the Big Apple Circus, founded by the juggling duo of Paul Binder and Michael Christensen, pitched its first tent in the sand at the foot of the twin towers, a then TriBeCa wasteland known as “the landfill.”

“New York School for Circus Arts Presents the Big Apple Circus.” Louisa Chase, 1977, Cut paper 29 × 23 in. (73.7 × 58.5 cm), Big Apple Circus.

Through February 3, Circus and the City: New York, 1793-2010, is on display at the Bard Graduate Center for Decorative Arts, Design, History, Material Culture. The show spans three floors of the Upper West Side Townhouse, and claims New York—and rightly so—as the wellspring of the American Circus (which, alas, isn't just under the bigtop).

“The Lottery”: PG-13 Version

In honor of the master of the creepy story, Shirley Jackson, we bring you this incredibly misleading pulp paperback cover. It must have led to some really disappointed —or freaked out—readers. Also: who is this demon lover of which they speak?

In honor of the master of the creepy story, Shirley Jackson, we bring you this incredibly misleading pulp paperback cover. It must have led to some really disappointed —or freaked out—readers. Also: who is this demon lover of which they speak?

The Haunting; Or, the Ghost of Ty Cobb

In July, a bat of Ty Cobb’s sold at auction for $250,000. The buyer, a Denver collector named Tyler Tysdal, said the bat was a present for his two-year-old son, John Tyler. This seemed to me very risky: as a small child, I was terrified of the ghost of Ty Cobb.

In July, a bat of Ty Cobb’s sold at auction for $250,000. The buyer, a Denver collector named Tyler Tysdal, said the bat was a present for his two-year-old son, John Tyler. This seemed to me very risky: as a small child, I was terrified of the ghost of Ty Cobb.

I can only imagine this had its genesis with my own dad. When I was small, he wrote a novel that dealt with the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, and baseball players of the era were a frequent topic of dinner-table conversation. In any event, I was somehow aware of the outfielder’s penchant for virulent racism, spiking opposing players, and general nastiness.

The real fear, however, did not set in until the day in 1985 when Pete Rose broke Cobb’s all-time hit record. Read More »

Boo! And Other Ways to Scare Kids

The top ten books for creeping out kids: a guide for parents.

“Give your ghost a life story, and other rules for writing a ghost story.”

What scares Neil Gaiman?

Scariest of all: “I wouldn’t have known about my Russian pirate translator had I not set a Google Alert for the title of my debut novel when it was published, in April 2011.” Peter Mountford chronicles an unlikely alliance.

“It was, perhaps, inevitable that Homo floresiensis, the three-foot-tall species of primitive human discovered on the Indonesian island of Flores, would come to be widely known as ‘hobbits.’ After all, like J. R. R. Tolkien’s creation, ‘they were a little people, about half our height.’ But a New Zealand scientist planning an event about the species has been banned from describing the ancient people as ‘hobbits’ by representatives of the Tolkien estate.”

October 30, 2012

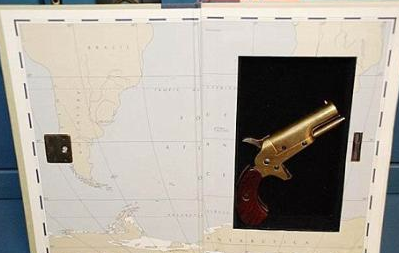

Gun Found in Donated Book, and Other Book News

When Indiana librarians opened a donated copy of Robert Stone’s Outerbridge Reach, they found it contained an Arma San Marco .31-caliber, a single-shot black-powder handgun. Reported reaction: “Oh, my.”

Essential stormy-weather reads.

Faulkner vs. Woody Allen: the plot thickens.

How to care for old and lovely books.

A breakdown of the megapublishing merger.

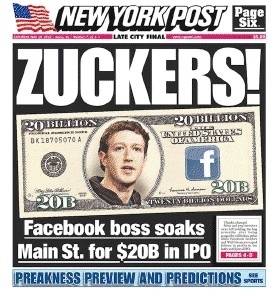

Like: Facebook and Schadenfreude

I was the 501st person to join Facebook. The inimitable Hatty Hong, number 499, urged me on from her desk across our freshman dorm room. I hardly used it the first few months because so few others were active, and as a senior I logged on to look at dead people’s profiles. Or to click through photographs of myself to remember where my time went. I didn’t think it was appropriate to remain a member after graduation. Facebook was something you were to outgrow, like Tommy Girl perfume or AOL Instant Messenger. Five years since graduation, I use it more now than ever.

I was the 501st person to join Facebook. The inimitable Hatty Hong, number 499, urged me on from her desk across our freshman dorm room. I hardly used it the first few months because so few others were active, and as a senior I logged on to look at dead people’s profiles. Or to click through photographs of myself to remember where my time went. I didn’t think it was appropriate to remain a member after graduation. Facebook was something you were to outgrow, like Tommy Girl perfume or AOL Instant Messenger. Five years since graduation, I use it more now than ever.

As an elder user, I can say one thing with authority: When it comes to disseminating news about Facebook, few media are more effective than Facebook itself. That’s how I came to learn that longtime users like me are more likely to believe others happier than themselves. At least according to a study from Utah Valley University. The longer one has used Facebook, they found, the more likely he or she is to recall other people’s positive posts: the stunning honeymoon in Greece of a girl you never really knew in high school—and whose last name now looks, well, Greek; a list of very impressive graduate school acceptances, the likes of which prompted one Awl writer to dash off a lesson in Facebook manners. Read More »

Document: Tim O’Brien’s Archive

The Professional, edited by Tim O'Brien, October 11, 1969. Reproduced by permission of Tim O'Brien, courtesy the Harry Ransom Center.

Tim O’Brien was drafted into the U.S. Army and sent to Vietnam on April 5, 1969, to serve with the Third Platoon, Company A, Fifth Battalion, Forty-Sixth Infantry Division. What he saw in battle has been so well documented that while reading his memoir I expected each page to be his last, anticipating the report of his own death. After eight months he secured a coveted rear job where his most onerous task was the preparation of The Professional, “a weekly authorized publication of the 5th Battalion, 46th Infantry, APO 96219,” of which he said this:

The newsletter was one of my assigned duties as battalion clerk, the job to which I was assigned after 8 months in the field with Alpha Company. By that point in my tour, as I discussed in some detail in If I Die… I was no longer doing infantry stuff, just the typical things you might expect of a clerk—typing letters and reports, filing paperwork, counting casualties, etc. (I despised the job, and I especially despised that ridiculous newsletter. But it beat getting shot dead.)

After the war O’Brien went for a graduate degree at Harvard, where he prepared his memoir, If I Die in a Combat Zone. Not much draft material survives for that book, but we never doubt its veracity. In his archive, now ensconced at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, there are letters home, to his parents; there are photographs; there is a uniform; there are medals. There is a lot of material from the nineties as he tracked down fellow members of Alpha Company, and as he revisited Vietnam. And there are two copies of The Professional: October 11 and October 20, 1969. The first issue, two pages from which are reproduced here, includes illustrations, cartoons, Vietnamese-English vocabulary lists, stories, and news. It also prints a story by O’Brien entitled “Trick or Treat,” portions of which appear verbatim in If I Die.

The Professional is a remarkable survival, especially given the handful of specific objects O’Brien mentions in the memoir which have not surfaced: letters from a girl he loves, unrequitedly, who sends him a poem by Auden, and who tells him, he writes, that he “created her out of the mind. The mind, she said, can make wonderful changes in the real stuff.” A letter to his parents, asking for his passport and immunization card, as he considers the appeal of Europe over Vietnam. Escape plans he kept folded up in his wallet. A journal he began, “vaguely hoping it will never be read.” And, perhaps most interesting, two letters from his first army friend, Erik Hansen, transcribed into the book. None of these narrative prompts within If I Die appear to have survived.

Perhaps surprisingly, much more of the more fictional The Things They Carried is documented by material in the archive. Why surprising? He's prepared us to believe it's as true as it isn't. He writes that, “story-truth is truer sometimes than happening-truth,” and “But only to say another truth will I let the half-truths stand.” In the chapter “How to Tell a True War Story,” O’Brien writes that a “true war story, if truly told, makes the stomach believe.” In the chapter “Notes,” he explains, “By telling stories, you objectify your own experience. You separate it from yourself. You pin down certain truths. You make up others. You start sometimes with an incident that truly happened … and you carry it forward by inventing incidents that did not in fact occur but that nonetheless help to clarify and explain.” In “Good Form”: “It’s time to be blunt. I’m forty-three years old, true, and I’m a writer now, and a long time ago I walked through Quang Ngai Province as a foot soldier. Almost everything else is invented.”

And yet, it’s not, not from the opening line:

“First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross carried letters from a girl name Martha, a junior at Mount Sebastian College in New Jersey.” Tim O’Brien carried letters from a girl named Gayle, and carried them back to civilization, and preserved them for decades. He also saved a letter he wrote to her on October 17, 1968, but never mailed. In his youthful, tense, inconsistent hand, he is already conscious of the disconnect and unity between reality and his presentation of it:

The very form of the letters and words here (my penmanship is straight & jerky & kinda childlike) conveys wrong things now. Add to that the fact that the thoughts themselves, the substance I put down, is inaccurate to reality, and you have a real problem. … I can go over to Vietnam, set up shop, and try to keep bullets & shrapnel & blood off my body & hands; the other choice is desertion, pure and simple. No, just pure. Not so simple, if you think about it, and I admit that I have done that. All night after getting the news.

Martha of the first chapter, the reader eventually learns, was not Jimmy’s—or even O’Brien’s—first love. That place of honor was held by the nine-year-old Linda of the last chapter: his fourth-grade sweetheart who died of a brain tumor in the summer of 1956, before returning for the fifth grade. Linda, the book version of a girl named Lorna Lou Moeller with whom O’Brien had been in love at the age of nine, incites and dominates the book’s final chapter, “The Lives of the Dead,” which appeared on its own (as did several chapters of the book) in Esquire. After publication O’Brien received a five-page letter from Mrs. Moeller, who had read the chapter, recognized her daughter, and remembered the O’Brien boys. She sent O’Brien a dozen photos of Lorna Lou, and a clipping documenting the too short life of a girl who would occupy space in O’Brien’s consciousness throughout his teens and adulthood. Moeller recalls her daughter’s feelings for the O’Brien siblings, and recounts the course of her illness and death.

In “The Lives of the Dead” O’Brien had written, “It is now 1990. I’m forty-three years old, which would’ve seemed impossible to a fourth grader … And as a writer now, I want to save Linda’s life. Not her body—her life.” These thoughts dated back, though, to the late fifties: two stories, composed in high school, have been preserved, in which he grapples with Lorna Lou’s illness and inevitable death. In “Two Minutes,” composed on seven leaves of his father’s letterhead from the Equitable Life Assurance Society, he recounts his futile attempt to save “Nancy,” who killed herself because “I’d persuaded her—no forced her would be a better word—to come with me to New York from her Indiana farm.” He races home in his car, knowing she is at death’s door, hoping he’ll make it in time to save her. Another story, called “Tulips,” filling twenty-two leaves of letterhead, is about a girl named Linda and a boy named Tim. O’Brien writes in 1990 that he had, in his youth, “saved” Lorna Lou in his dreams, always seeing her alive, sometimes discussing her death with her. In one dream he asks her what it’s like to be dead. She responds, “I guess it’s like being inside a book that nobody’s reading.”

By the time O’Brien came to write The Things They Carried, he had experienced staggering death and loss as an adult, but his mind returned, still, to the nine-year-old girl:

And then it becomes 1990. I’m forty-three years old, and a writer now, still dreaming Linda alive in exactly the same way. She’s not the embodied Linda; she’s mostly made up, with a new identity and a new name … She was nine years old. I loved her and then she died. And yet right here, in the spell of memory and imagination, I can still see her as if through ice, as if I’m gazing into some other world a place where there are no brain tumors and no funeral homes, where there are no bodies at all.

He can also see his dead Company mates, Kiowa, Ted Lavender, Curt Lemon. “And sometimes I can ever see Timmy skating with Linda under the yellow floodlights. I’m young and happy I’ll never die.”

In response to my description of The Things They Carried as “(perhaps marginally) more fictional than If I Die,” O’Brien commented,

by any ordinary standard the vast bulk of TTTC is invented and is fiction. Even the Gayle/Martha material is almost entirely the product of my imagination, both in terms of its detail and in its rendering of events. The Lorna Lou/Linda stuff calls more heavily on actual events, yet 80 or 90 percent of the chapter is completely invented. As a novelist, I have ruthlessly (and joyously) sacrificed the so-called ‘real world’ for the sake of story.

What interests me, then, is the process by which O’Brien cast and shaped and finessed objects, facts, memories, and dreams into a compelling narrative. Working papers for this—though not for If I Die—proliferate in his archive. In addition to raw drafts of individual chapters and two annotated rounds of the complete manuscript, I saw page proofs, with O’Brien’s final autograph revisions throughout.

He put his hand to eighty-five pages, sometimes adding, dropping, or changing a word, other times, revising an entire speech or paragraph or striking through a line or series of lines. He seems to have had the most difficulty settling on text in “In the Field” and its complement, “Field Trip,” but the distribution of the balance of revisions is fairly even throughout the book.

Where we’ve all seen “Joint Chiefs of Staff,” he originally had “Bobby Kennedy.” The “orange glow of napalm” was originally black. Bad breath had been fever blisters, and before that, acne. An aluminum suitcase turned into a cardboard box, and then back, to “a metal suitcase.” A banyan tree became a palm tree. Was it “hot and steamy,” or, better, “cold and steamy?” High school had been college, and a “lacy red blouse” had originally been a pink T-shirt. More substantively, he deletes “I was a coward” and a discussion of gallantry, and rewrites a sentence about losing the Silver Star. Such examples convey the spirit of this final round of revision and show a fair sampling of the sort of changes that could be either alterations to enhance the story, or more simply reversions to accuracy (after all, if Faulkner was right, “memory believes before knowing remembers”).

O’Brien has played so much, and so successfully, with genre that I wonder that we still bother to acknowledge some of the distinctions that still seem so important to the publishing sales force and the bookstore buyers and the talk-show hosts. Does it make any kind of sense to separate If I Die from The Things They Carried and even Going After Cacciato in the bookstore? Clearly, someone thinks we as readers care. I’d argue strenuously that we should not. We should simply take a page out of one of O’Brien’s books: “The thing about a story is that you dream it as you tell it, hoping that others might then dream along with you, and in this way memory and imagination and language combine to make spirits in the head.”

Sarah Funke Butler is a literary archivist and agent at Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, Inc.

Singular, Difficult, Shadowed, Brilliant

The ancients are right: the dear old human experience is a singular, difficult, shadowed, brilliant experience that does not resolve into being comfortable in the world. The valley of the shadow is part of that, and you are depriving yourself if you do not experience what humankind has experienced, including doubt and sorrow. We experience pain and difficulty as failure instead of saying, I will pass through this, everyone I have ever admired has passed through this, music has come out of this, literature has come out of it. We should think of our humanity as a privilege.

—Marilynne Robinson, The Art of Fiction No. 198

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers