The Paris Review's Blog, page 894

August 13, 2012

Carp: How to Catch Them

The Clown Continuum

A strange man asked if he could hit me in the face, straight on, with a pie. He said he was a clown, pies were his thing.

“Sure!” I emailed back, complete with the seemingly uncontrollable enthusiasm, perhaps a little forced, implied by an exclamation point.

“You’re a good sport, Monica,” he wrote.

His words unnerved me.

When I tell people about the story, I want to talk about the clown. I want to say that Jusby the Clown has a degree from Evergreen State College. A degree! He’s worked to forge “a bridge between Eastern and Western forms of clowning.” He’s interested in “the special healing role of the clown around the world” and “the organic link between the clown and the shaman.”

I want to build his credibility because that builds mine: I didn’t just meet a strange man in a park to let him smear my mascara in his whip cream in front of children. I opened myself up to a spiritual experience.

But the truth is, I didn’t know his credentials when I said yes, and before I ever get that far telling the tale my friends, my audience, stop on the first part. You said yes?

Why would I say yes? A woman I know, a writer, recently published an essay that starts out, “At the very beginning of what I now know was a mid-life crisis, I let a guy pee on me.” And I found myself at a party spilling my drink as I leaned over to insist, “It’s entirely different! It was a pie! He’s a clown! He teaches laugh yoga, for God’s sake.”

Really the only thing I knew about Jusby, when I agreed to his plan, was that he’d read my novel Clown Girl and quoted from it. That was plenty.

This is what it means to be a first-time novelist: I’d spent ten years writing and revising a novel about clowns, clown community, and the creative struggle. Now a member of my newfound readership wanted to offer me that big, physical comedy kiss of a pie in the kisser. How could I turn my back?

Booksellers tell me the best way to move a book is to hand-sell it, one person urging it on another. When Clown Girl came out I said yes to everything, always for that chance to hand-sell. I drove across state lines and read in chain bookstores. One night I read to an audience of empty orange chairs and a lone man in a trench coat who yelled over my words then tried to touch my hair. I drove my little Nissan through dark streets to a tiny radio station for an interview where the late-night host hadn’t read any of my writing. I flew to the heart of the country, slept in a stranger’s house, and taught workshops in exchange for a bottle of water.

My friend of the golden-shower essay writes, “I was desperate to know I was desirable.” She says, “The man who would pee on me … he’d read my memoir.” Oh, booksellers! Oh, honorable Best Seller list! Those sweet enticements. Somebody tell me there’s a difference between dating and marketing, between seeking readership and a relationship, blind dates and the ongoing literary conversation, because I have lost track.

Though the secret truth is, I may be made for the life of the reclusive writer merged with risk taking. I’ve been both shy and a hand-raiser my whole life. I was in a theater class, ages ago, when a stranger sent a note through our teacher that he needed clowns. There was money in it. I raised my hand. That job led to more clown work, the way one decision stumbles into the next. That experience led to my novel, and the novel led Jusby the Clown to me.

Pie throwing could be a valid act of cultural criticism in the clown world. Maybe it’s a necessary baptism or a hazing. Going along with the role of willing victim, I chose the time (daytime, definitely) and the place (public). We’d meet in Peninsula Park, one of Portland’s many urban green spaces. I arranged my own blind date with a clown.

People who say they’re afraid of clowns oversimplify the demographic. There’s plenty to be afraid of, more in some corners than in others, but clowns aren’t a single species. It’s a continuum, and ranges from the Evangelical arm of Christian clown ministries to the hot and bothered corners of the fetish scene. In between you’ve got birthday parties, business promotion, political activism, and rodeos. Depending on how you do it, clowning can have a built-in drag-queen glitz or a transformative, outsider appeal. There’s been a serial murderer or two behind the paint, John Wayne Gacy–style, but that’s not the norm. And then there are the Juggalos, latchkey followers of Insane Clown Posse, a branch of youth culture with no actual clown skills, not even when it comes to eyeliner.

The day I said yes, for all I knew Jusby could be anywhere on this continuum. I rounded up a crew, my backup, who’d serve as witnesses, partners, and a roving party. I invited three friends, all of them at the time also first-time novelists. They were the willing. I invited Lance Reynald, James Bernard Frost, and Kassten Alonso. Kass is my husband. Whatever tricks Jusby the Clown had up his silky sleeve, my husband and I would be in it together.

Our troupe arrived at the park first. We gazed out between towering cedar trees, then over the concentric rings of a manicured rose garden, past a giant classical fountain. Kids played on the swings and slides. It was Oregon’s best weather, with blue skies and a reasonable sun. I wore a retro nylon maxi-dress salvaged from the seventies, a cross between a muumuu and prom wear, fancy yet synthetic enough to clean up in a basic wash. We scanned the perimeter.

What to expect? I looked for a fetishist creeping up behind me, stalking a pie virgin. Then I saw our guy. He loped across the park sporting a red rubber nose. Jusby has a soft, manly face, made for the role of a rugged clown. He came in full paint, his eyes highlighted with a heavy white arch over each lid, and a classical clown smile that crept up onto his cheeks. His lapels were festooned with buttons, around a mix of black and white stripes and polka-dots. Under that he wore layers of red against red. A workingman’s white Hanes T-shirt poked out at the neckline. He’s a bear of a man.

“Aboriginal clowns called [pie-ing] entering the Creamtime, in Old French the Tarte Blanche, ancient Romans had Cobbler Rasa.” Jusby poured out a quick patter that gave the impression he’d done this a dozen times. Turns out, he’s done it upwards of 560 times. He handed me a clipboard and a pen. A man with a camera trailed behind him. It was all more formal and ritualized than I expected—formal to the point of involving forms. The clipboard held a waiver of liability. I signed away photo rights and legal rights, as though I were an extra in some improvised theater. He passed another set of the same forms to my husband, then to Lance and Jim.

With the camera involved, I had new reservations. I was in makeup. Not clown face, but ordinary woman’s war paint. My skin would totally blotch under whip cream and the social pressure of anything like audience. I’m a blusher, big time. James Bernard Frost, aka Jim, gave it up fast. He got down on his knees near a flower bed in a supplicant’s position and made the universal bring it on gesture with both hands. Jim could go first.

Jusby has rules about his pie work. He also has beliefs. Later he’d tell me, “The pie gets a sensory experience that’s also a ritualized initiation.”

He tipped a pie in front of Jim’s face, moving with a grace and strength I know now was developed through studying Butoh dance and Poekoelan, an Indonesian fighting art.

He says, “The pie represents crossing into dreamtime, into a lucid euphoria, a liminal space between ordinary states, neither the known world nor the unknowable ... ” He works with anticipatory anxiety, extending that moment of knowing a pie is on the way, like a sneeze coming on. A Latino woman and a pack of what may have been grandchildren paused to watch, held by the energy of an event about to happen.

And in that moment it happened: Jusby offered Jim a dose, a hit, a big smack of clown pie, whip cream in an aluminum tin. He welcomed Jim into the unknown of dreamtime, and there, indeed, was the euphoria! Jim broke into a grin, wiped his eyes, fumbled for a towel. He laughed out loud. Maybe he laughed at himself.

Lance Reynald stepped up next and chose his own corner of the park. Fine by me. The audience for our little pie-an-author event grew. We still had the grandmother and kids, joined now by a pair of hot Portland-style hipster lesbians, a white guy in a basketball jersey, and somebody’s golden retriever. They got in line as though Jusby was an amusement park ride. They wanted to be hit! They asked for it, begged for it, recruited each other, and willingly signed waivers of liability.

Could it be they sensed the possibility of a transformational magic through public spectacle, a moment out of time, carving a significant experience out of an otherwise fleeting, incidental slice of existence? Maybe not. Maybe we were in a modern day town square, lining up to be pied by the village idiot. Who, exactly, was the fool then?

Jusby bent and swirled whip cream into another aluminum tin with the hiss of a whip-it. He didn’t actually throw the “pies,” but pressed them into each face. Lance was sticky with whipped cream. A guy in sideburns and skinny girl jeans slid into his place, in the new official/unofficial pie-ing corner. I’d lost my spot in line.

And I thought, this guy, was he even a writer? Had he published? If he had, was it with a vanity, indie, or corporate publishing house? I mean, I was the one who brought everyone together. I’d worked for a decade on a book about clowns. It was my pie party. Jusby slapped a little boy with a pie, at the boy’s request and delight. The photographer took pictures of every mom and baby, duck, and dog—but I was the author who’d been sought out for this!

It was up to me to make a move. So why did I hesitate? Sure, there was the makeup question, my own vanity, and a photographer’s lens trained on each pie recipient. Mostly, it was just easier to take on the audience role. As TV watchers, we’re trained for it. I could stay witness or step into action, take a spot on that fleeting stage, a place defined only by the eyes of the crowd. I said, “Okay.” We’d do it, while there was still space on that camera’s memory card.

Jusby waved Kass forward. “Husband and wife, let’s do this together.” Kass stepped up with me. We stood side by side and held hands. Jusby rolled up his sleeves, reached into his duffle for a fresh pie tin. The photographer raised his camera. I felt in my stomach a familiar flutter of trepidation. It was our wedding all over again. Who were those strangers in the crowd? They made me self-conscious. I’d been eight months pregnant at our actual wedding, that’s how shy we’d been about having a ceremony. I waited until the last moment I was willing to put on a dress.

I was thirty-nine before I had a child, that’s how long I hesitated—until my last good egg.

A plane cut across the blue sky, leaving its white line of toxic exhaust. Jusby tipped the nozzle of a whip cream canister to his pie tin. Everything I’ve ever done that matters has been through saying yes, haltingly, in the face of doubt.

Jusby managed to balance a second pie tin in the same hand as the first, one for each of us.

Lance smiled at me from the crowd. His hair was sticky and in spikes. James Bernard Frost had gone off to duck his head in the park’s do-not-swim-here chemical-laced water feature of a fountain. And I saw the hipster-girl couple, their eyes on us. If they ever wanted a wedding, they could have one! At least this kind—the clown kind, which is to say not the legally binding sort, not the religious version, the kind considered “real.” They too could have a moment in a park.

The sun gleamed off the whipped cream and the edge of the aluminum tin as Jusby put down his canister. And I felt in my body the beauty of saying yes against doubt: it’s necessary. Yes to the future, and to this moment, and to our daughter, the most important decision we’d ever made. I wanted to give back to the world. I was in love, in that wedding ceremony way. Everyone should have the right to say yes, wildly, within the law. The crowd smiled back at us. I beamed into the camera. I wanted our lives to have meaning, our actions to take on a narrative shape.

“A messenger arrives and the recipient becomes the message,” Jusby said. The camera flashed.

The world went dark. I couldn’t breathe. He’d caught me off guard. The aluminum pan pressed against my face, my nose, my mouth—the whip cream was giving, but the pan wasn’t. My nose flattened. I was drowning! I’d suffocate under cheap whipped cream. It was no way to go. The audience roared. They laughed. This was the end.

I’d made a mistake, said yes once too many times. I heard a child yell, me next! And I wanted to tell that child, Go back. Don’t do it! I flapped an arm, tried to drop my husband’s hand, but he held on. Then the pressure on my face subsided. I blew whipped cream out my nose, opened my mouth to gasp for air. Somebody put a towel under my fingers.

The sun came back, while my eyelashes were heavy and clotted. I gulped for air and laughed out loud, and now the laugh was at my own fear of death. My heart knocked against my chest. “You may kiss the bride!”

I was newly baptized, married, initiated. I was the fool and the folly. Maybe I’d hand-sell one book out of this. My books weren’t even there. It wasn’t about books. It was about the careless freedom to make random adult mistakes and see what would come next.

When the whipped cream pies were gone, and the sun sat low over the roof of a Java Hut across the street, I pulled a bottle of red wine and cups out of my bag. Jusby accepted a cup with a nod, that silent clown language of the body, then found a bench. My friends and I were tourists in the pie world, high on new experience. Jusby was spent, and deflated. It showed in the slope of his shoulders. He sipped wine with the calm energy of a bartender after hours.

Our friend of the golden-shower essay writes a redemptive tale: She wised up, she says, and found instead the life and experiences she really wants. My experience wasn’t so sordid, and perhaps that’s why my break hasn’t been so clean or clear.

I have photos of that day. They’re as lovely as any from our wedding. Over a year later, I’m still sorting out why the pie-ing was important. Jusby’s explanation goes like this: “When the clown comes … you’re participating in an event that lasts seconds but whose residue lasts quite a bit longer.”

That’s exactly how I’d describe our wedding. “When the clown comes … ” Maybe that’s one way to describe that sex act, the moment that led to the birth of our daughter, to ballet classes and tantrums and sticky kid hands.

The residue lasts much longer.

Monica Drake is the author of Clown Girl (soon to be a major motion picture) and The Stud Book, out in February, 2013. She lives in Portland.

Rich Writers, Niche Bookstores, Darwin

Check out the handmade books of Berlin-based Palefroi.

Maria Papova presents the literary jukebox, in which quotes are matched to thematic songs.

Forbes lists the highest-grossing authors.

A salute to niche bookstores of the world.

The fate of dead books: a history of pulping.

Prior to proposing to Emma Wedgwood, Charles Darwin did a cost-benefit analysis of marriage, with one of the deficits listed as “less money for books.”

August 10, 2012

In Which the Author Reads the Works of Albert Cossery: An Illustrated Essay

David Rakoff, 1964–2012

We are sad to learn of the death of David Rakoff, at forty-seven, after a long battle with cancer. Rakoff’s essays and contributions to This American Life include what must be the most melancholy humor writing of our time, or else the funniest melancholy writing. Even at his most arch, Rakoff wrote with an undertone of kindness that made his fans love him. Many of his readers will feel that they have lost a friend.

We are sad to learn of the death of David Rakoff, at forty-seven, after a long battle with cancer. Rakoff’s essays and contributions to This American Life include what must be the most melancholy humor writing of our time, or else the funniest melancholy writing. Even at his most arch, Rakoff wrote with an undertone of kindness that made his fans love him. Many of his readers will feel that they have lost a friend.

What We’re Loving: Old New York, The Boss, SodaStream

I didn’t think I would ever read another book about Henry James. But here I am, three quarters of the way through Michael Gorra’s Portrait of a Novel, a book-length study—or really, essay—on The Portrait of a Lady. It reads like an old-fashioned work of belles lettres, combining biography, travelogue, and literary history (plus a good deal of helpful synopsis) to explain how and why James wrote his best-loved novel. The explanation is full of grace and deep learning lightly worn. Yet Gorra takes for granted James’s homosexuality, and his sexual knowledge, as well-established facts. In this sense, it is a book of our moment, a hi-def image of the Master coming into his own. —Lorin Stein

The host, for some reason, was taking Instamatic pictures of his guests. It was not clear whether he was doing this in order to be able to show, at some future time, that there had been this gathering in his house. Or whether he thought of pictures in some voodoo sense. Or whether he found it difficult to talk. Or whether he was bored. Two underground celebrities—one of whom had become a sensation by never generating or exhibiting a flicker of interest in anything, the other of whom was known mainly for hanging around the first—were taking pictures too.

I have Lorin to thank for introducing me to Renata Adler’s 1976 first novel, Speedboat. Maybe its unconventional structure (a series of vignettes) and plotline (there isn’t really one) are not for everyone. But for sheer linguistic pleasure, fierce intelligence, and a vivid picture of seventies New York, look no further. I breezed through it in a day and have been recommending it left and right with the kind of excitement I haven’t felt in a long time.—Sadie O. Stein

Bruce Springsteen’s music is the Staff Pick of my heart. “Bobby Jean” and “Secret Garden” give tremble to the word rock, while “Born to Run” accomplishes something in music that Holden Caulfield did in literature, honestly portraying the anxiety of adolescence in a desire to escape. The New Yorker’s profile of Bruce Springsteen is a breathtaking homage to the now sixty-two-year-old rocker, who is set to embark on yet another world tour. The piece follows a young Springsteen watching Elvis on the black-and-white telly, takes us through his years of top-forty glory and out into a political movement that gave hope to the country. The profile shows that there is still heart in the music industry—even if that heart was born in Jersey. —Noah Wunsch

Conrad Signals, Server Signs

Because it is Friday, a Joseph Conrad bat signal.

A pair of Irish researchers have determined that Homer’s epics are (partially) based in fact. “We’re not saying that this or that actually happened, or even that the individual people portrayed in the stories are real ... We are saying that the overall society (that emerges from the stories) and interactions between characters seem realistic.”

The son of John Steinbeck has publicly objected to the invocation of Of Mice and Men to justify the Texas execution of a mentally handicapped man.

Celebrate Julia Child’s centenary with these ten titles.

If you wish to rakishly mix your media, here is how to make a screen saver from your favorite book cover.

The secret language of restaurants; or, how your waiter knows who gets what.

And how did you celebrate Book Lover’s Day?

August 9, 2012

Larger Than Life: An Interview with Will Self

Last August, I interviewed Will Self—whose latest novel Umbrella has just been long-listed for the prestigious Man Booker Prize—in his London home. I had been given two weeks to prepare and I was quite terrified. My terror was warranted; I had spent the last ten days immersed in his hallucinatory fictional worlds, composed of seven novels, three novellas, and countless short stories. Through these parallel and often overlapping fictions, Self has constructed a relentless critique of our institutional failings, hypocritical cultural mores, and political inadequacies. My fears, notwithstanding being intellectually dwarfed, were largely to do with the sheer madness of many of his writings. Here was the writer who, over the years, had invented:

1. A man who wakes up with a vagina behind his left knee and has an affair with his (male) GP (Bull: A Farce);

2. A parallel Earth populated by nymphomaniacal and exhibitionist apes seen through the eyes of its most prominent experimental psychiatrists (Great Apes);

3. The afterlife taking place in the purgatorial London district of “Dulston,” a suburb populated uniquely by senseless, chain-smoking dead people, haunted by their aborted fetuses and old neuroses, and living out the rest of infinity in dire office jobs (How the Dead Live);

4. A postapocalyptic London governed by a religion based on a cab driver named Dave’s insane writings to his estranged son in the 2000s (The Book of Dave).

And then there was the public figure—an acerbic satirist of towering intellect, a giant man of letters with a rhetorical bite strong enough to tear a lesser being apart. By the time I rang on the doorbell, Will Self had, to my mind, transmogrified into The Fat Controller—the Mephistophelian antihero in his My Idea of Fun—ready to shred me from limb to limb for my idiotic questions and inadequate readings.

The Alligator Lady

It was one of our first tours back in the summer of 1999. We had been on the road for a month when we pulled into Lawrence, Kansas. The show at the Replay Lounge was sparsely attended, and we spent most of the night dumping quarters into tired, malfunctioning versions of Pole Position, Joust, Tempest, and Dig Dug. At the bar, we heard a rumor about a woman in Kansas City who raised alligators in her home.

The next morning we drove into Kansas City to eat Gates BBQ and look for the house. We were pointed in a general direction, but no one in town could verify this place actually existed. We found ourselves in a lonely part of town right at the edge of the city’s border. After two blocks of knocking on doors, we were ready to call it quits, and then an elderly woman in her seventies opened the door. We introduced ourselves as alligator enthusiasts and asked if she knew anything about the legend of Alligator Woman. “Know her? I am her.” She had a bright smile like a former actor. Her teeth were perfect. No stains, gaps, or cracks in those real teeth. She pushed aside a pile of chicken wire and welcomed us into the dark rooms. I can’t even tell you how good it was.

Excerpted from Who Farted Wrong? Illustrated Weight Loss for the Mind, by permission of Write Bloody Publishing.

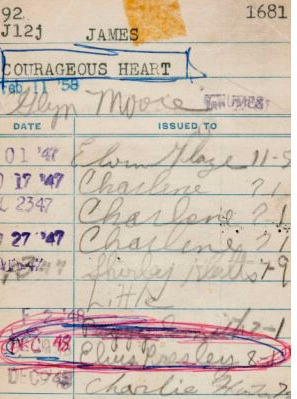

Buy Elvis’s Library Card

Elvis Presley’s 1948 library card can be yours. At thirteen, The King checked out The Courageous Heart: A Life of Andrew Jackson For Young Readers from his high-school library.

We appreciate this peek into book psychology by one who should know, Waterstones: “Being books, and not understanding most things beyond their limited understanding, the books attribute most events to Father Christmas.”

Adam Gopnik remembers Robert Hughes.

Some encouraging bookstore news, for a change: on their Kickstarter page, the founders of Singularity & Co. explain that their mission is to “choose one great out of print work or classic and/or obscure sci-fi a month, track down the people that hold the copyright (if they are still around), and publish that work online and on all the major digital book platforms for little or no cost.”

In 2013, John Banville will bring Raymond Chandler’s hard-boiled detective Philip Marlowe back from the dead under his crime-writing nom de guerre, Benjamin Black.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers