The Paris Review's Blog, page 895

August 8, 2012

The Southern Underbelly: Remembering Lewis Nordan

The other night, in order to feel close to my friend Lewis “Buddy” Nordan, who recently died, I started rereading his novel Wolf Whistle, a story inspired by the murder of Emmett Till in 1954. (Buddy grew up in the Mississippi Delta near the place of the murder. He knew the murderers. He became friends with Emmett Till’s mother.)

After reading the opening chapter, I took my dog outside under the moonlight. I felt wrapped in Buddy’s language. The night was cool. The half-moon was bright enough to throw shadows. When my dog disappeared in the shadow of a cedar tree, I started sketching in my mind a few paragraphs of fiction about a boy and his dog. Minutes later, back inside, I had five paragraphs on paper, a novel opening, something I’d been seeking for months. I read it over. There in my sentences, besides the dog and the bright half-moon and shadows, I found an improbable gathering of nouns: frogs, the Battle of Fort Fisher, a flood plane, Bela Fleck, the planet Venus, and a set of plans for a freelance funeral militia. I had opened up to something. Both my opening up and the something were gifts made possible in large part by Buddy’s odd vision—a vision that allowed him to juxtapose thunderbolts and whispers, a vision on display here in his opening to chapter nine of Wolf Whistle, occurring after the murder at the center of the book:

From the eye that Solon’s bullet had knocked from its socket and that hung now upon the child’s moon-dark cheek in the insistent rain, the dead boy saw the world as if his seeing were accompanied by an eternal music, as living boys, still sleeping, in their safe beds, might hear singing from unexpected throats one morning when they wake up, the wind in a willow shade, bream bedding in the shallows of a lake …

The chapter continues from the perspective of the murdered boy’s eye.

All in a Single String

There’s a black-and-white photograph of me in my grandparents’ old Moscow apartment. I’m wearing a hand-knit wool dress, two white stripes down the front. My hair is a mess of tight curls around my head. A lopsided smile exposes my teeth. With my right hand, I’m petting a guitar that looks like it might be taller than I am. It is polished wood, dark around the edges, growing lighter toward the center, an intricate garland along its bottom edge. It’s my grandfather’s. It has seven strings.

“A guitar with six strings isn’t a guitar,” my grandfather tells me. “You can’t play on it. You can’t sing to it. It’s worthless. A guitar must have seven strings to be worth its name.” He stops. He closes his eyes. His voice takes on a new tone. “The seven-string guitar, that’s the real guitar. Its voice sings. That, that is the Russian guitar.” I don’t quite understand—to me, a guitar is a guitar—but I know enough to realize that the difference is real to him and that I should abandon my attempts, later, to get him to buy a regular guitar in any old American music shop. As much as he might love me and want to make me happy, he will never play a standard-issue instrument. He will keep searching for his lost seventh string—and if he doesn’t find it, I’ll never again have a chance to hear him play. The decision is final.

Some say the seven-string guitar, the semistrunka, was born with the Central European gypsies. A child of the lute-shaped torban, carried back by Ukrainian Cossacks from Flanders after their mercenary stint in the Thirty Years’ War. The torban, whose familiar bass notes distinguished it from other members of its family. Some say it came from the Turks, during their thirteenth-century migration from Abkhazia to Poltava—a descendant of the kobza, that other lute-like instrument that could have as few as three and as many as eight strings—and might not the number have been seven? Some say it is a child of the Renaissance, the flat-backed cittern—an instrument akin to the mandolin and the English guitar (the latter perhaps its closest relative). With its metallic strings, its popularity in song, and its quick spread over Europe, it seems not altogether unlikely—though the cittern had four strings or six, sometimes five. Not seven. The seven-string guitar has many creation myths. But the most accepted version is that, whatever its origins, it first came of age as a uniquely Russian instrument.

Psychos, Pencils, and Fines

This terrific German blog gives the pencil its due (and, perhaps, then some).

In a time when e-books outsell their paper counterparts, NPR wonders whether cover design is a dying art.

In a gesture of either great magnanimity or great desperation, the Chicago Public Library waives all fines.

Movies you may not have known were inspired by books. (In the case of Psycho, probably because Hitchcock tried to buy up all the copies so there’d be no “spoilers.”)

On the one hand, we take issue with some of the rankings on this list of the hundred greatest young-adult novels. On the other, it’s encouraging to know kids are voting. (At least, we hope that’s the explanation.)

In obligatory Fifty Shades of Grey news, author E. L. James is curating an album of the classical music featured in the trilogy. (For the uninitiated: in addition to being the world's youngest billionaire and most accomplished lover, Christian Grey is also a world-class musician.)

August 7, 2012

Your Eyes Deceive You: Claire Beckett at the Wadsworth Atheneum

Marine Lance Corporal Nicole Camala Veen Playing the Role of an Iraqi Nurse, Wadi Al-Sahara, Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, CA, 2008

In Hartford overnight for reasons that would take too long to explain, my wife and I visited the Wadsworth Atheneum, the city’s art museum, where she had interned a number of years before. Hartford is one of those midsize American cities, like Cincinnati or Worcester, dominated by Chris Ware cityscapes.

The Atheneum is a small, good museum and interesting in that way that Hartford is interesting: on a comparatively small stage the choices are more evident, the collections more particular. Things that would be pushed into the storeroom at another museum are given fascinating pride of place. What is less well known is not so consistently edged out by what is too well known.

We walked past the museum’s two Balthuses into a room full of photos of men in headdresses, dusty streets, namelessly Middle Eastern scenes. A man fiddling with a bomb. Something was off, however: there was too much unfinished plywood and the people staring into the camera were clearly … what?

We slowed down, read wall text. This woman is a Marine lance corporal.

Letter from India: When the Cat’s Away

The Pin Valley is near the Tibetan border. In fact it was a part of Tibet. It was given to India in the fifties, to protect it. In winter it is snowbound. In summer, at three miles elevation—above the tree line—it is a stone bowl of dust.

The Pin Valley is near the Tibetan border. In fact it was a part of Tibet. It was given to India in the fifties, to protect it. In winter it is snowbound. In summer, at three miles elevation—above the tree line—it is a stone bowl of dust.

Two years ago, I was following a seventeen-year-old around the world, trying to get permission to write about him. I followed him from Kathmandu to India, and that was when I heard of the Pin Valley for the first time. Westerners living in India were going up for the last ten days of a month-long program for the monks in Pin Valley. There were no guest houses there. People who wanted to attend the program would stay in Kaza, the nearest town. They would ride in and out by car daily, an hour and a half each way.

This year, 2012, was different. An enterprising Westerner had partnered with a Tibetan tour operator—a trekker by trade—to build a camp a kilometer and a half from the monastery, on a piece of unused farmland with a well.

Loving Gorey, Trashing Ulysses

Eve Bowen on the enduring cult of Edward Gorey.

We love Bookdrum’s interactive maps of the real locations featured in famous novels.

On his tumblr Newcover, graphic designer Matt Roeser gives books the covers he thinks they should have.

At the Atlantic, a discussion of what grown-ups can learn from kids’ books.

Paolo Coelho made waves when he told a Brazilian newspaper, “One of the books that caused great harm was James Joyce’s Ulysses, which is pure style. There is nothing there. Stripped down, Ulysses is a twit.”

Should you happen to disagree, here is a free audiobook of the modernist classic.

Joshua Cohen, a visiting scribe at the Jewish Book Council, talks the art and business of writing with Justin Taylor.

August 6, 2012

Benjamin Franklin’s Clippings, Circa 1730

An illustrated series of short news items written by Benjamin Franklin for The Pennsylvania Gazette. News at that time was fueled by hearsay and favored brief, outlandish anecdote. Where Franklin was running his paper in a wilderness devoid of information, we now operate in a wilderness so granite-packed with information that perhaps we now feel just as isolated, just as in the dark. These represent the dawn of American journalism, but I think in the present climate we’re moving back in that direction.

Jason Novak works at a grocery store in Berkeley, California, and changes diapers in his spare time.

Gore Vidal’s Bully Republic

A few years ago, fresh off a diet of Wilde, Maugham, and Saki, I was beginning to feel disappointed by the gay pantheon. Not the actual writing—no one could find fault with that. It was the example of their lives that depressed me, ending more often than not in loneliness and/or despair, if not complete exile.

I remember having a conversation with my father about it. I told him what I’d really have liked to find, in my exhaustive search of the canon, was a gay superhero. You know: fucking dudes, saving the world. Never mind the fact that superheroes, with their notoriously contour-hugging apparel, are usually assumed gay by default. I wanted something that had existed, something from history. My father considered my criteria.

“I think what you want is Gore Vidal.”

I think it took me all of one day to read Myra Breckinridge in full and possibly a month to process it. The cartoon version of gender deviance it put forth was one that, against all odds, enraptured me. From its famous opening (“I am Myra Breckinridge whom no man will ever possess”) to Myra’s core, radical aim in life (“the destruction of the last vestigial traces of traditional manhood in the race in order to realign the sexes…”), to the lengthy rape scene three quarters through, wherein Myra rapes a guy with a strap-on, comparing herself to an Amazon and making him say thank you afterward, the message was clear. She was the ultimate queer bully, taking no prisoners and getting a comeuppance so ridiculous that Vidal gives the reader no choice but to discount any kind of moral implications it might have otherwise had.Read More »

Man Pulls Sword over Badly Treated Book: Happy Monday!

“Christopher Meusburger, twenty-nine, of St. Paul, Minnesota, allegedly threatened his sixty-two-year-old neighbor with a sword on Monday night after she complained that he mistreated a book she lent him, the Pioneer Press reports.”

A list of great lists.

“The birth scene is now a staple of film and television, but strangely absent from fiction—sometimes alluded to in passing, but rarely dwelt on in closeup.”

“The hardest and most frustrating books ever written.”

Meet Bardowl: Spotify for audiobooks.

August 3, 2012

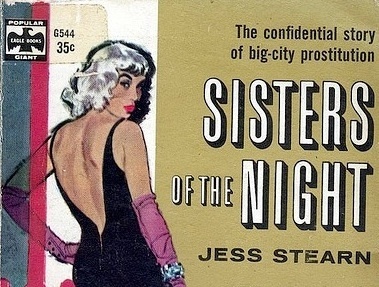

Sisters of the Night

The bookstore, and especially the used bookstore, is vanishing from New York City. Today there are a few, but there used to be a multitude of them, crammed between kitchen appliance shops and Laundromats and thrift stores. They all had temperamental cats prowling their aisles and they all smelled wonderfully of what a team of chemists in London has called “a combination of grassy notes with a tang of acids and a hint of vanilla over an underlying mustiness.” I will miss terribly this stimulating fragrance, and the books that produce it, when it’s washed from the city for good. Luckily, there are towns that still accommodate used bookshops. Lambertville, New Jersey, is one of them. On North Union Street, there are two used bookstores, Panoply and Phoenix Books, one right across from the other. You can spend hours here, and it’s guaranteed that you’ll return with some grassy, musty artifact of the past. On my last visit to Panoply, I came home with a copy of Sisters of the Night: The Startling Story of Prostitution in New York Today by “veteran newspaperman” Jess Stearn.

Published in 1956, the book began as an assignment for the Daily News when Stearn’s editor told him to find out what makes prostitutes “tick.” He was told, “Get out and talk to the girls, see the judges, the social workers, the cops, the headshrinkers—you won’t win a Pulitzer Prize but it should be worth reading.” Dragging his feet, the reluctant Stearn complied, going out in search of what one of the book’s reviewers called the “orchidaceous girls” of the city.

A faded black-and-white photo. Suited and tied, he looks tired as hell, resting his arms atop his clunky manual typewriter at a desk covered in a snowdrift of papers. He has deep, dark circles under his eyes. I wonder if the photo was taken during the writing of Sisters of the Night, when Stearn was up all hours prowling the city’s backwater joints, pretending to be a john so he could talk one-on-one with hard-edged young women in crummy rooms and dingy restaurants, where they dragged at cigarettes and told their stories of abuse, drugs, and fun. He worked hard to depict them just as they were. As the girls speak, leaning close, you can almost smell the spearmint chewing gum snapping in their mouths, mixed with nicotine and a cloud of Tabu, “the forbidden perfume.”

Tabu: The Forbidden Scent, 1950s

In a bar near Madison Square Garden, a blonde B-girl (the B stands for “bar”) explains to the author why she prefers sailors to other men: “With sailors there’s not much chance of getting hurt. They’re on the go and so are we . . . I’ve taken many a sailor who was down and out to my room. I might have spent the night with a boy from Princeton and done myself some good, but I didn’t.” The B-girl likes getting letters from the sailors, envelopes with exotic stamps that she collects and trades with other B-girls. But she’s no stamp-collecting whore. “I want you to know one thing, Mr. Reporter,” she tells Stearn. “I’m not a tramp. I work hard during the day. I’m a clerk in a factory. It’s damn dull, and the nights are the only thing that keep me alive.”

The B-girls hope to find romance, maybe even marriage. Some are attractive, others not so much. Most started hustling in their teens. Peggy is one of them. In her diary—stuffed with paper Valentines, restaurant menus, and ticket stubs—she writes about nights smoking “reefers” and juggling a stable of brutal men who offer small gifts in exchange for favors—“He bought us a gang of drinks, plus cigarettes and nickels for the jukebox and when we were going home he gave me $1 for cab fare.” But Peggy is still in pain. “I went to the candy store to listen to records. I had Steve’s picture with me. And, diary, while listening to the records, I felt so lonely and empty inside.” Peggy got busted as a first offender, then vanished from the NYPD’s records.

After the B-girls, Stearn learns about “pony girls.”

A cross between a B-girl and a call girl . . . a pony’s big-time stuff, but she picks her own men. They generally work out of some East Side bar where the Johns know where to find them. The bartenders freeze out servicemen and other stiffs because they aren’t well heeled. The ponies are after big money.

Cool in their metallic gowns, slinking through bars on shabby streets near Rockefeller Center, the pony girls cost $50 an hour, far more than the lowly streetwalker who offers herself to men at a hamburger counter for 75 cents a pop.

52nd Street, 1950s

Stearn teams up with a friend for courage and tracks the pony girls to 52nd Street. Also known as Stripty-Second, this part of the street has been taken over by burlesque. Time magazine said of the scene: “nightclubs in sorry brownstones crowd each other like bums on a breadline,” each one featuring dancers peeling it off to three-piece bands. In one shabby club, Stearn and his friend talk with a buxom blonde chanteuse from Buffalo who loves the poetry of Dylan Thomas. She laughs when Stearn propositions her, saying, “The only thing we hustle here is drinks—I’d get canned if I took a live one out of here.” But the dancer on stage is rumored to be “a call girl in flimsy disguise,” a star who charges $100 for her phone number, $200 for lunch, and $1,500 for weekend cruises. “Why does she bother with a night-club act?” Stearn’s friend asks him over watered-down whiskies. “That’s easy,” Stearn jokes, “even Macy’s has to advertise.” But he and his friend can’t afford her and they move back out into the night. The author still hasn’t answered the question “What makes these girls tick?” and he’s getting tired.

In a downtown restaurant he talks to Willie the Weasel, an emaciated pimp who watches his girls through a peephole while they work.

“I used to have to hold on to my sides,” he says, “or I might have split a gut from laughing. They were a howl. Some of these old guys with the big bellies would stand there and say to the girl, ‘Whip me.’ So she’d whip until they were screaming. And they’d scream, ‘Harder, harder!’ And you should have seen the looks on their faces—like baboons.”

Next, Stearn visits an apartment on Central Park, in a “very respectable building” where the management thinks the girls are models in the Garment District. Here, high-end call girl Jane sits chain-smoking and stroking a Pekingese in her lap, telling of her days making $1,000 a week. She fell in love with one of her Johns, a boy who “sent me so many flowers the place smelled like a funeral parlor.” But that didn’t last. “Love, schmove,” she says, “who knows about love?” Jane hopes for a career in show business. “They tell me that I have more versatility than a lot of those dames on TV.”

In an East Side bar, Georgia sips a Martini and talks of working stag parties where she takes on gangs of Johns. She gets beaten up by bachelors, clean-cut young men who leave her blacked out, surrounded by empty bottles and cigarette butts. It’s nothing a bowl of hot broth and some sleeping pills can’t fix. She keeps going back for more. In an untidy tenement living room, a “vivacious redhead” shares the poetry she writes about suicide, about jumping into the East River. She was once the wife of an iceman, then she was a hat-check girl, and now she hustles, searching for the “big-timer” who’ll marry her and make her “Mrs. Rich Bitch.” But it hasn’t happened yet.

And there’s Eileen, a girl from a good family who came to New York to work a legitimate job, but the employment agency men “kept asking me to lift my skirt, so they could see my legs. A couple of them suggested that I start as a cigarette girl or camera girl in night clubs.” She fell into prostitution, and now she feels too dirty to live the straight life. “I’ve made my bed and I’m going to lie in it,” she says, resigned.

After all his talking to prostitutes and pimps, Stearn still doesn’t understand “what makes them tick.” So he seeks out a psychoanalyst, a “headshrinker” who’s an authority on the subject. Prostitutes hate men, the shrink explains, they all have a weak father figure and they seek revenge against him. “They are sick women bent on self-destruction,” he says, “and they first destroy what men prize above everything else in a woman—female virtue.” But prostitutes also have a paradoxical love for unfortunate men. Why are they so kind-hearted, Stearn wonders, with blind beggars, violin-playing cripples, hunchbacks, and legless mendicants perambulating on roller-skate platforms?

I don’t know if Jess Stearn ever satisfied his questions and I wondered what became of him, that tired, beleaguered fellow on the back of the book jacket. A quick Googling revealed that, after Sisters of the Night, he went on to write books with subtitles like Drug & Delinquent Stories, A Startling Investigation of the Spread of Homosexuality in America, and A Report on the Secret World of the Lesbian. Then he left smutty New York City for the clean living of Malibu where he dedicated himself to psychic phenomena, yoga, reincarnation, and the life of New Age forefather Edgar Cayce. In later photos and videos, he is no longer the weary newspaperman, but a smiling, silver-haired Californian wearing cable-knit sweaters among the palm trees. He died in 2002 at age 87. His New York Times obit read: “No funeral services are planned for the writer, who believed he had lived previously and would live again.”

As for all those B-girls and pony girls, did any of them get to live another life? I imagine that some went back to checking hats and selling cigarettes, some tried acting, some ended up dead too soon—murdered, overdosed, jumped into the East River—and some surely left the city’s seamy joints and dives to shuffle back to Buffalo (or Kenosha, Cuyahoga, Lambertville), where they became mothers and grandmothers, members of the local Junior League, spending summer weekends weeding gardens and whipping up batches of Ambrosia. They’d be into their seventies by now. I’d like to think there’s a woman somewhere who, wisely suspicious of e-readers, will wander into some moldy shop, hungry for the smell and the feel of old books. She’ll happen upon Sisters of the Night and recognize herself as Georgia, Jane, or Eileen—no, this is Peggy, the girl who got away. (She goes by Margaret now.) Turning the yellowed pages, she’ll read excerpts from her forgotten teenage diary, heart pounding to recall the wild, lost girl she was when she wrote long ago: “I remember once wanting to be a nurse, or else going to teaching school. I knew all along they were only dreams. I guess the only way you get anyplace is by hustling for it. I wonder whether I’ll make a good hustler.”

I just hope I didn’t take the copy meant for her.

Jeremiah Moss is the pseudonymous author of the blog Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York. He has also written about the city for The New York Times.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers