The Paris Review's Blog, page 785

September 5, 2013

Secret Book Landscapes, and Other News

These miniature landscapes, painted on the sides of nineteenth-century books, were recently discovered at the University of Iowa.

Jokes (of varying degrees of hilarity) for grammar nerds.

Adding to the indignity of Richard III’s parking-lot exhumation, scientists have now discovered that the monarch had worms. “Thy broken faith hath made the prey for worms,” wrote Shakespeare, calling it.

Speaking of cross-pond exhumation! “Exhuming Poirot is disrespectful towards Agatha Christie’s careful burial,” argues John Sutherland in The Guardian.

September 4, 2013

Letters from Jerry

Last Sunday, a ninety-four-year-old man appeared outside my door. His name, he said in a deep German accent, was Werner Kleeman. He had come all the way up to Washington Heights from Queens to celebrate the birthday of his cousin down the hall. He was invited. He is certain of the date. But his cousin is not there.

Severely hard of hearing, with no cell phone nor ride home, Werner slumps in a folding chair a neighbor brought, marooned. When he rises, he sways woozily, perspiring in his dapper suit. My husband takes one look and gets the car. Once on the Cross-Bronx Expressway, Werner revives and tells the story of his life.

Born in Bavaria, he had been interned in a concentration camp. But he was able to produce a visa to the U.S., and, as was still possible then, at the start of the war, he was freed. He emigrated to New York, and then returned to fight the Nazis as an American soldier. Stateside, he made a modest living in a unique niche—hospital drapery. His wife passed away three decades ago. Since then, he’s lived alone. This trip is his first outing in weeks. “Now!” he chortles raucously as we near his street. “To my museum! You will not believe your eyes. I can show you things like you have never seen!”

Werner’s museum, it turns out, is a low-ceilinged, jumbled Flushing bungalow where he has resided for the last sixty-two years. He leads us through the cramped rooms, playing tour guide to a host of treasures: a dented spice box rescued from the desecrated synagogue in his native village; scenes by a famed sketch artist from the European front; a framed proclamation of honor for his self-published 2007 memoir, From Dachau to D-Day, signed by now-rival mayoral candidates John Liu and Christine Quinn.

As we try to say goodbye, Werner blocks our exit, brandishing a packaged coffee cake. “I have decided,” he announces, as if to himself. “Kind people, educated people. Yes. Why not?” He puts on water for tea, takes my hand, and draws me into a shaded back office from which he carefully withdraws a file. “You have heard,” he enquires, “of the writer J. D. Salinger? Letters from my friend Jerry.” We sit down. Read More »

Franzen on Kraus: Footnote 18

Oskar Kokoschka’s 1925 portrait of Karl Kraus. Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna.

This week, to celebrate the launch of our Fall issue, we will preview a few of our favorite footnotes from “Against Heine,” Jonathan Franzen’s translation of the Austrian writer Karl Kraus. Click here to get your subscription now!

People are very talented in the jungle, and talent begins in the East around the time you reach Bucharest.18

(p. 196)

18 This sentence is very funny in German. I can’t translate it any better, and so I have to resort, dismally, to trying to explain the humor. Kraus is again going after easiness—here, the ease with which foreign travel lends spice to writing. The joke is, approximately, that the jungle is fascinating to us non-jungle-dwellers, and that we mistake this fascination for talent on the writer’s part. Thus: people are very talented in the jungle. Kraus ridicules this phenomenon by way of contrasting himself with Heine, whose best-known prose was his travel writing and his dispatches from Paris. Although Kraus vacationed abroad and spent parts of the First World War in Switzerland, his life’s work was focused exclusively on Vienna, and it obviously galled him to hear foreign-traveling writers praised for their “talent.” Here I think his venom is directed more at admirers of jungle writing than at its producers. The former are perpetrating bad literary values, the latter merely making the most of such talent as they have. There is, after all, a long tradition of writers venturing overseas for material. The funniest fictional example may be the young man Otto, who, in William Gaddis’s The Recognitions, goes to Central America in quest of the character he natively lacks, but the inverse relationship between travel and character is found in real life, too. I’m thinking of Hemingway, whose style was as strong as his range of theme was narrow (would he actually have had anything to say if he’d been forced to stay home?), and of Faulkner, a writer of real character whose best work began after he gave up his soldier dreams and his New Orleans flaneurship and returned to Mississippi. You can’t really fault Hemingway for being aware of his own limitations, but you can (and Kraus would) fault the culture for making him the face of twentieth-century American literature.

Hemingway’s star seems to have faded a little, so a takedown of him now wouldn’t be as incendiary as Kraus’s takedown of Heine, but he’s an interestingly parallel case, not only in the general outlines (both he and Heine were expats in Paris, obsessed with their literary reputations, and famously nasty to writers they perceived as rivals) but in their literary methods. Kraus’s critique of Heine’s writing—that it was fundamentally hack journalism, dressed up in an innovative and easily copied style—could apply to a lot of Hemingway’s work as well.

Seventeen Innings, Twenty-Nine Years

The old Durham Athletic Park. Photo: Kate Joyce.

Should anyone flatter us by asking us what we are searching for, we think immediately, almost instinctively, in vast terms—God, fulfillment, love—but our lives are actually made up of tiny searches for things … Add them together, and these things make up an epic quest. —Geoff Dyer

The playoffs begin in Durham tonight. It’s tempting to dismiss minor-league championships as dubious, if not entirely factitious, especially in Triple-A: major-league rosters expanded on September 1, so the Bulls and their competitors have been raided for some of their best players. The post-Labor Day games draw tiny crowds anyway. So who cares?

I do. The most exciting game I’ve ever seen was a Durham Bulls playoff game.

September 4, 1984. Twenty-nine years ago today, the Durham Bulls beat the Lynchburg Mets, 8-7 in seventeen innings, in game two of the Carolina League Championship series. I was at the game in a nominally official capacity. That year I was the “statistician” for Steve Pratt, the Bulls’ radio broadcaster. My job was also factitious: Steve kept his own stats; he was just carrying out a favor for the team owner, who was collegially friendly with my stepfather and humored him by taking me on. My pay was a free sandwich after the fifth inning. I had a calculator and crunched some numbers, but mostly I sat there all summer and watched baseball. Read More »

Fifty Shades of Rage, and Other News

Joey Ramone sings John Cage adapting Finnegans Wake. Got that?

Paul Muldoon’s eulogy for Seamus Heaney.

Fans of the Fifty Shades series are outraged at the casting; a petition is circulating and already boasts 7,300 signatures. The producer has taken to Twitter to defend herself.

The Agatha Christie estate has granted permission to author Sophie Hannah to write a new Poirot mystery.

September 3, 2013

Franzen on Kraus: Footnote 3

Oskar Kokoschka's 1925 portrait of Karl Kraus. Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna.

This week, to celebrate the launch of our Fall issue, we will preview a few of our favorite footnotes from “Against Heine,” Jonathan Franzen’s translation of the Austrian writer Karl Kraus. Click here to get your subscription now!

Believe me, you color-happy people, in cultures where every blockhead has individuality, individuality becomes a thing for blockheads.3

(p.189)

3 You’re not allowed to say things like this in America nowadays, no matter how much the blogosphere and the billion (or is it two billion now?) “individualized” Facebook pages may make you want to say them. Kraus was known, in his day, to his many enemies, as the Great Hater. By most accounts, he was a tender and generous man in his private life, with many loyal friends. But once he starts winding the stem of his polemical rhetoric, it carries him into extremely harsh registers.

(“Harsh,” incidentally, is a fun word to say with a slacker inflection. To be harsh is to be uncool; and in the world of coolness and uncoolness—the high-school-cafeteria social scene of Gawker takedowns and Twitter popularity contests—the highest register that cultural criticism can safely reach is snark. Snark, indeed, is cool’s twin sibling.)

As Kraus will make clear, the individualized “blockheads” that he has in mind aren’t hoi polloi. Although Kraus could sound like an elitist, and although he considered the right-wing antisemites idiotic, he wasn’t in the business of denigrating the masses or lowbrow culture; the calculated difficulty of his writing wasn’t a barricade against the barbarians. It was aimed, instead, at bright and well-educated cultural authorities who embraced a phony kind of individuality—people Kraus believed ought to have known better.

It’s not clear that Kraus’s shrill, ex cathedra denunciations were the most effective way to change hearts and minds. But I confess to feeling some version of his disappointment when a novelist who ought to have known better, Salman Rushdie, succumbs to Twitter. Or when a politically committed print magazine that I respect, n+1, denigrates print magazines as terminally “male,” celebrates the Internet as “female,” and somehow neglects to consider the Internet’s accelerating pauperization of freelance writers. Or when good lefty professors who once resisted alienation—who criticized capitalism for its restless assault on every tradition and every community that gets in its way—start calling the corporatized Internet “revolutionary,” happily embrace Apple computers, and persist in gushing about their virtues.

In Memoriam: John Hollander

During his five-decade career as a poet, the late John Hollander was a frequent contributor to The Paris Review. He was also renowned as a scholar and critic. Here he is remembered by two former students, our contributor Jeff Dolven and editor Lorin Stein.

John Hollander once told me a story that served him as a kind of ur-scene of explanation. As a boy he was sitting with his father at the breakfast table, and he asked, apropos of nothing he could later recall, “Dad, what is a molecule?” By way of an answer, his father reached into the sugar bowl and lifted out a cube.

“So what is this?” his father asked.

“Sugar,” said John. Next his father set the cube down on the table and rapped it sharply with a teaspoon, so that it broke into coarse crystals.

“And what is it now?”

“Sugar,” said John again.

“Well then,” said his father, “a molecule is the smallest piece of sugar you can get that’s still sugar.” The grown-up John delivered the last sentence like a punchline, laughing and widening his eyes and spreading his hands. Read More »

William Faulkner’s Unexpected Art, and Other News

William Faulkner’s drawings from his Ole Miss days are wonderfully Deco.

Random House UK launches The Happy Foodie, described thusly: “Bringing cookery books to life, helping you get happy in the kitchen.”

In other slogan-y UK books news, Books Are My Bag (which supports bookstores and features a tote bag bearing exactly those words) attracts celebrity adherents.

Cairo’s iconic German-language bookstore, Lehnert & Landrock, faces closure amidst the nation’s turmoil.

“Beckett had a lifelong interest in chess and was a keen player, following many of the big matches, says his nephew, Edward, who oversees the Beckett estate.” How chess influenced Samuel Beckett’s work.

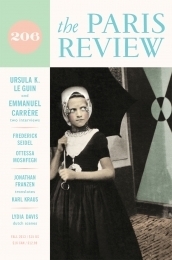

Introducing Our Fall Issue!

Since 1953, a central mission of The Paris Review has been the discovery of new voices. Why? It’s not just a matter of wanting to lead the pack or provide publishers with fresh blood. In “The Poet” Emerson wrote, “the experience of each new age requires a new confession.” That’s our idea, too.

Even by TPR standards, our Fall issue is full of new confessions. Readers will remember Ottessa Moshfegh, the winner of this year’s Plimpton Prize. We think our other fiction contributors—and most of our poets—will be new to you. They certainly caught us off guard.

We also have new kinds of work from writers you do know—a photography portfolio curated by Lydia Davis, and a project more than twenty years in the works: Jonathan Franzen’s translation of Karl Kraus, including some of the most passionate footnotes we’ve encountered since Pale Fire.

Find an interview with groundbreaking writer Ursula K. Le Guin:

A lot of twentieth-century— and twenty-first-century—American readers think that that’s all they want. They want nonfiction. They’ll say, I don’t read fiction because it isn’t real. This is incredibly naive. Fiction is something that only human beings do, and only in certain circumstances. We don’t know exactly for what purposes. But one of the things it does is lead you to recognize what you did not know before.

The Art of Nonfiction with Emmanuel Carrère:

Your first impulse is to be terribly embarrassed by the other’s suffering, and you don’t know what to do, and then there’s the moment when you stop asking yourself questions and you just do what you have to do.

All this plus new poems by former Paris Review editors Dan Chiasson, Charles Simic, and Frederick Seidel.

September 2, 2013

The Snack

I first considered the meaning of the word snack in fourth grade while reading the children’s book The Giver. The main character, Jonas, remembers elementary school, when the proper pronunciation of the word eluded him. He says “smack” instead and is punished with the literal smack of a ruler until he learns to pronounce the word correctly. The author uses Jonas’s confusion to highlight the book’s main theme: that knowledge and pain should never be tied together.

Though the “snack” incident plays only a minor role in The Giver, it made me realize that prior to pre-school there had been no such thing as a snack. There were three meals a day that were prepared and consumed rather formally. Meals were pleasurable and nourishing and that was that. They had purpose—they knew who they were, followed a routine schedule, had a role, and happily filled their recipients. They gave context to a day and helped quell any hint of insatiable hunger, or bouts of melancholy. They maintained a steady daily course from kitchen to table to belly. They delivered.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers