The Paris Review's Blog, page 784

September 9, 2013

Have Questions About The Paris Review? Ask Our Editors on Reddit!

Have a question about The Paris Review? How do the interviews work? What’s our pitch process? Are we a CIA front?

Paris Review editors will be hosting a Reddit AMA (short for “Ask Me Anything) tomorrow, September 10, at 3 P.M. EDT.

See you then!

The Immortality Chronicles, Part 4

What have we not done to live forever? Adam Leith Gollner’s research into the endless ways we’ve tried to avoid the unavoidable is out now as The Book of Immortality: The Science, Belief, and Magic Behind Living Forever. Every Monday for the next three weeks, this chronological crash course will examine how humankind has striven for, grappled with, and dreamed about immortality in different eras throughout history.

During the Middle Ages, every alchemist worth his saltpetre tried to find the philosopher’s stone, the water stone of the wise, the miraculous stone that is no stone. It was the means to transmute base metals into gold and—more importantly—concoct elixirs of immortality.

The word is Arabic in origin: al-kimia, al-khymia, or al-kīmyā. It’s how chemistry begins. Science, as we now conceive it, did not exist in the medieval period. (The word scientist only became commonplace in the nineteenth century after Cambridge University historian William Whewell coined the term in 1833.) Instead, there was natural magic and philosophy—and alchemy, the experimental attempt to combine different elements and uncover the factual mysteries of nature.

Dr. Who Poetry, and Other News

“We’re trying to reorder some of the myths based on the documents.” Bolaño’s unpublished work, on view in Spain.

Harper Lee and agent Samuel Pinkus have apparenty reached an “agreement in principle” to settle the eighty-seven-year-old author’s copyright lawsuit.

While he might have objected to their dissemination, here are twenty-two out-of-print J. D. Salinger stories that you can read online.

A crowd-funded Dr. Who poetry book? Oh, it’s happening.

September 6, 2013

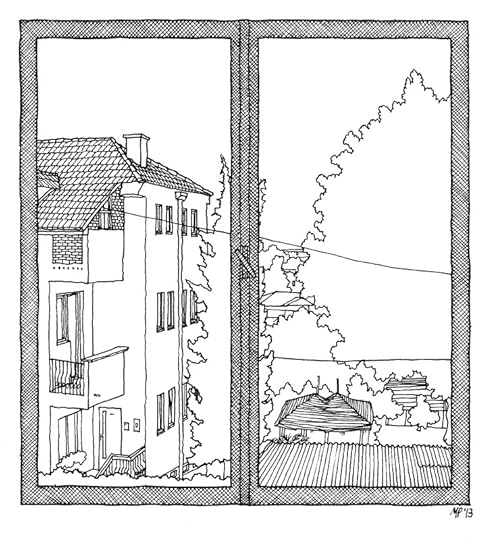

Lidija Dimkovska, Skopje, Macedonia

A series on what writers from around the world see from their windows.

My late childhood and entire youth window. I began to write in front of this view, and while I am here, I still do, at a low, small table. On a typewriter then, on a laptop now, but preferably in a small notebook with lines.

I look outside often; the pictures have become very familiar. Two brothers used to live in the building with their families and their old mother, a small, tiny woman in black who always was screaming at her grandchildren, often beating them or running after them. They also were screaming, and that noise was present in the air until the parents would come home from work. Later, I found out that they moved the grandma from the first floor to the cellar, where she died. One of her daughter-in-laws was Serbian; once, the Serbian woman sent me and my friends to the shop to buy her a special orange juice, Fructal. She opened it, and for the first time in my life I tried this juice that my family could not afford.

The roof of the building was always in my view. In the mornings a stork would come to the chimney on the roof and look through my window. We looked each other in the eyes, and we understood each other. He was my sky, I was his earth’s friend. It was impossible not to write. —Lidija Dimkovska

Franzen on Kraus: Footnote 89

Oskar Kokoschka’s 1925 portrait of Karl Kraus. Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna.

This week, to celebrate the launch of our Fall issue, we will preview a few of our favorite footnotes from “Against Heine,” Jonathan Franzen’s translation of the Austrian writer Karl Kraus. Click here to get your subscription now!

In the end, the people who never came out of their province will go farther than the people who never came into one.89

(p. 216)

89 I think there’s a lot of truth in this, but Kraus also seems to be making an implicit claim about his own decision to remain rooted in Vienna, in contradistinction to Heine. Here’s the story I tell myself about his agon with Heine. Basically, Kraus arrives too late. He’s an assimilated Jew who has an enormous facility with language but strikingly less talent with “original” forms like poetry, drama, and fiction. And unfortunately there’s already been a German-speaking Jew like him—Heine—who, worse yet, became one of the most famous and influential writers of the previous century. Kraus needs room to live and to work and to believe in the necessity of his work, and what does he have to hold on to in his struggle against his famous precursor? His feeling that there was something wrong with Heine—with the work, the man, his language. And so the story that he tells himself is that Heine was a proto-Kraus who betrayed his gifts by his moral failings and thereby betrayed assimilated German Jews, too. Heine helped create the stereotype of the rootless, linguistically facile Jew. Without Heine, no feuilleton, yes. But also: without Heine, Kraus could simply have been a great satirist who happened to be Jewish. Hence, I propose, the ferocity of the attack in this essay, and the peculiarly moral tone of it. If Kraus also sounds an anti-Semitic note, it’s because he’s trying to annihilate the bad Jew, the stereotypical Jew, so as not to hate himself. That so many Gentile German philistines are willing to forgive Heine’s Jewishness only adds to his rage.

I, too, often make moral arguments about art, but on my better days I’m suspicious of them, because I’m aware of the envy, the powerlessness and self-pity, that lurks behind them. Back in the nineties, I spent a lot of time assembling a moral case against John Updike. I was offended (rightly, I still think) by Updike’s famous comparison of a writer’s work to excretion: you take in life, digest it, and shit it out in paragraphs. Updike was very proud of his three-pages-per-day regularity, and I didn’t need to know much about his personal history to imagine his mother crowing over the neatness and beauty of his daily bowel movements. My moral complaint was that Updike had tremendous, Nabokov-level talent and was wasting it, because he was too charmed by his daily dumps and too afraid of irregularity to take the kind of big literary risks that might have blocked him for a year or two. His lifelong penchant for alliteration was of a piece with this. It made reading even his otherwise fine stories about the Maples painful; I couldn’t get through more than a few lines without running aground on the anal-retentive preciousness of his prose. Updike was exquisitely preoccupied with his own literary digestive processes, and his virtuosity in clocking and rendering the minutiae of daily life was undeniably unparalleled, but his lack of interest in the bigger postwar, postmodern, socio-technological picture marked him, in my mind, as a classic self-absorbed sixties-style narcissist. David Foster Wallace was the one who actually called Updike an asshole in print (in the New York Observer), but I felt the same way. If you’d suggested that I envied Updike for his unobstructed productivity, or for all the women he got to go to bed with him (and then wrote about in graphic detail), I would only have restated my moral case more trenchantly.

Later on, after Updike ceased to seem like such a threat, I went through a period of feeling deeply censorious of Philip Roth, because he didn’t seem to care about his many glaring technical deficiencies as a fiction writer, and because his admirers didn’t seem to, either. Roth’s writing seemed to me, as Kraus says of Heine’s, “always and overplainly informative,” which was why, I believed, the philistines had come to tolerate him a lot better than he tolerated the philistines. As with Updike, my judgments had a flavor of Krausian moralism: Roth was lazy, Roth was an asshole, etc. Naturally, I believed that I was merely sticking up for vital aesthetic virtues—a fiction writer ought to be able to write good dialogue, create convincing and well-rounded female characters, and let a story tell itself without discursive intrusions—but these “vital” virtues happened to coincide with some of my own abilities as a fiction writer. To make my moral case against Roth, I had to ignore or downplay other plausible virtues, most notably Roth’s heroic fearlessness of his readers’ moral judgments, because I subterraneanly envied his fearlessness and wanted people to pay attention to me and not him. This was the kind of thing that Nietzsche had in mind when he mocked the “slave” mentality of moral judgments.

“Heine and the Consequences” is the document of Kraus’s struggle to overcome his great precursor. On his own terms, he may have succeeded; his best-known and most shattering work, The Last Days of Mankind (a documentary “drama” of the First World War) was written in the decade that followed. German readers, however, are not so convinced that he vanquished Heine. My friend Daniel Kehlmann, the Austrian novelist, loves the essay and grants that Kraus scores a lot of points off Heine in it. “But,” he says, “Heine is still wonderful, too.”

What We’re Loving: Taxidermy, Heroines, Bad Ideas

There are moments, on a red-eye flight, when your brain is too jumpy and raw to figure out what, exactly, n+1 is arguing in its attack on “global literature.” When you can’t go back to your (global?) novel and don’t want to plug your head into a cooking show, and when sleep is out of the question. For such moments, pack Kevin Barry’s Dark Lies the Island—a story collection that roams over the Irish landscape during and after the Boom, and through several dozen varieties of bad idea, from selling meth, to having children, to organizing an ale-tasting excursion in Wales. At the risk of indulging in cultural stereotypes, Barry is Irish: when he writes a story, he tells a story, and he’s not afraid of a sentimental ending, if one presents itself. Along the way, he takes such contagious pleasure in his flawed, incorrigible people that I was happy to be on a plane. —Lorin Stein

In Sorting Facts; or, Nineteen Ways of Looking at Marker, Susan Howe writes, “I have loved watching films all my life. I work in the poetic documentary form, but didn’t realize it until I tried to find a way to write an essay about two films by Chris Marker.” The films in question are La Jetée and Sans Soleil. Howe splices her thoughts about these works together with childhood memories of watching Olivier’s Hamlet, the early history of Soviet cinema, an elegy to her husband, and the fallout of Hiroshima, among other subjects. It is an investigation, as she says, of “the immense indifference of history” and “the crushing hold of memory’s abiding present.” It is also, one feels, about the discovery of kinship between a documentary poet and a documentary filmmaker, via the essay—whose root meaning, as both Howe and Marker remind us, suggests experiment rather argument, and a commitment to the art of surprise. —Robyn Creswell Read More »

Tolstoy Goes Digital, and Other News

All of Tolstoy’s works are going online. “We wanted to come up with an official website that will contain academically justified information,” explains his great-great-granddaughter. The work on the site will have been triple-proofed by more than three thousand volunteers from some forty-nine countries.

This week, FSG has collected a lovely series of Seamus Heaney reminiscences and tributes—by Jonathan Galassi, Rowan Ricardo Phillips, Maureen N. McLane, Robert Pinsky, and more—on their blog.

Maya Angelou will be the recipient of the Literarian Award, an honorary National Book Award for contributions to the literary community.

UK charity shops are overwhelmed with a glut of Fifty Shades books—unrecyclable due to the glue used in their bindings. (Recommendation: find the nearest motel.)

A new app allows self-published authors to add their own sound tracks and effects to audiobooks. For good or ill.

September 5, 2013

Pynchonicity

“Paranoia’s the garlic in life’s kitchen, right, you can never have too much,” announces a character in the new novel Bleeding Edge—yet because its author is Thomas Pynchon, let’s not take that valorizing of paranoia too lightly; elsewhere the same character grouses about “when paranoia gets real-world.”

More than any other recurring Pynchonian concept, paranoia receives nuanced treatment in the novelist’s work. A tendency toward the “p” word would seem to color his personal life as well: although he reputedly lives in plain sight on New York’s Upper West Side, he keeps his private life more private than that of any other major American artist. And, after being a stone Pynchonophile for nearly thirty years, I’ve finally started feeling a bit paranoid myself. It’s not the dot-com “hashslingrz,” Pynchon’s latest fictional conspiracy, that’s freaking me out, but the author himself. Never before has he set one of his novels in a time and place which I myself inhabited, and as I whooshed back to the New York City of 2001—this time through Pynchon’s aesthetic filter—his world spookily coincided with mine, mapping over it at points both minor and major. Call it a case of “Pynchonicity.”

As it happens, I spent much of 2001 rereading the then-available Pynchon canon: the historical books (Gravity’s Rainbow, Mason And Dixon); the contemporaries set during Pynchon’s own adult years (The Crying Of Lot 49, Vineland); and his first novel, V., a hybrid of those two forms. I was thirty-eight then, Pynchon was sixty-four, and a goal of my project was to understand the man, to puzzle out what kind of mind could be equally open to profundity and vulgar puns, tenderness and cruelty, hard science and the occult, sweet lyricism and, well, Rainbow’s notorious shit-eating scene. Given Pynchon’s aversion to cameras, microphones, reporters’ notebooks, and public podiums, the texts were all I and his other readers had to work from. Read More »

Franzen on Kraus: Footnote 48

Oskar Kokoschka’s 1925 portrait of Karl Kraus. Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna.

This week, to celebrate the launch of our Fall issue, we will preview a few of our favorite footnotes from “Against Heine,” Jonathan Franzen’s translation of the Austrian writer Karl Kraus. Click here to get your subscription now!

And Heine had a talent for being embraced by young souls and thus associated with young experiences.48

(p. 210)

48 J. D. Salinger might be an example of an American writer whose reputation has similarly benefitted from being read in people’s youth. But consider here, too, the periodic arguments from Bob Dylan fans that Dylan deserves the Nobel Prize in Literature.

My Nothing to Hide

I tried not to look. The couple couldn’t see me but I could see them, day and night, if I chose, and often enough I did. It’s a benefit or drawback of urban living that our sight lines in the tight geometry of New York City drive us into the lives of others, into private moments not meant for spectators, if we do not pull the blinds, if we don’t look away or past what’s on offer.

I lived in Brooklyn Heights, as I still do, but at the time I found myself on the third floor of a jumble of an old building on the main drag, Montague Street. It’s a street more plaintively commercial and less pretty than the rest of tony Brooklyn Heights; it is more alive with neon and the coming and going of chain stores, salons, restaurants. And with noise, too—from the meals eaten, booze served, and the resulting high spirits, and then those ancient garbage trucks, circling and circling, their brakes screaming.

I stayed too long in that one spot probably, but the rent was affordable, the Greek landlord fatherly, a friend who often treated me to dessert and stories, and I felt safe then in what I described as a garret but was merely two small rooms that vibrated from the ventilation units from the restaurant below.

The front of my apartment looked out onto Montague. The rear faced an accidental courtyard, the back of the restaurant, Mr. Souvlaki, featuring a fountain that usually didn’t work, a small fenced-in patch of scattered plantings, and the backside of a few apartment buildings. The buildings were close, less than fifty yards from what was my combined kitchen and living room, and the apartment in which I came to see so much was slightly higher than my own, so my vantage allowed me to peer up and in, as if that one living space directly across the way was up on a pedestal.

I can’t say when the couple moved in because when they did I’d been in love and my eyes were diverted inside me, charting the ways in which I felt discovered, opened up, prized, or to the moments I’d be near him again, inside the gold of his skin, the wiry lengths of his arms, or to the future of more love and his lips on the back of my neck and shoulders, his tongue writing messages there, everywhere, reaching inside my insides. And there was the pull of his intoxicating smell and even of his home, not in Brooklyn or in New York state, but further north in a place by the Atlantic dotted with sea roses and overrun with green so dense, during the season I met him, that it seemed in revolt, poised to take over. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers