The Paris Review's Blog, page 781

September 18, 2013

The Church of Baseball

Fireworks over the Durham Bulls Athletic Park. Photo: Kate Joyce

On Saturday, the Bulls won the International League championship. They won the championship! We showed up to document them, and it’s as if they responded to the scrutiny, performed for the cameras. I can’t help thinking of the observer effect. Did we help cause this?

The series was tied at one win apiece after the Bulls and the Pawtucket Red Sox split a pair of 2-1 games in Durham. The run deprivation bottomed out in game three at Pawtucket: neither team scored for an incredible thirteen innings. The futility (or great pitching, if you prefer) went on for nearly six hours. It was dazing and gripping, by turns, with blurry, barren stretches punctuated by a few dramatically thwarted rallies.

Around midnight, it became clear that whoever won this game would go on to take the best-of-five series, for the blood would go right out of the loser of this marathon. Finally, in the fourteenth inning, the Bulls scored two runs—without getting a hit, naturally: Pawtucket coughed up two walks and two errors. Even though Durham closer Kirby Yates loaded the bases with two outs in the bottom of the fourteenth, there was no doubt he’d pitch out of the jam. A rousing strikeout on a full-count pitch ended the game and, essentially, the series. Read More »

The Hemingways Hold Grudges, and Other News

Ernest Hemingway and Patrick “Mouse” Hemingway with a Gun in Idaho. Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Quoth Patrick Hemingway, “I’m not a great fan of Vanity Fair. It’s a sort of luxury thinker’s magazine, for people who get their satisfaction out of driving a Jaguar instead of a Mini.” VF rejected his dad’s story “My Life in the Bull Ring With Donald Ogden” in 1924, and apparently the Hemingways hold a grudge; although Vanity Fair reportedly wanted to publish it, the story will run in the October Harper’s.

“Insults from Kakutani about characters or the book or its author: 27.” Michi, by the numbers.

NYU’s Center for French Civilization and Culture kicks off its “Re-Thinking Literature” conference tomorrow. Speakers include Ben Lerner, Wayne Koestenbaum, Joshua Cohen, and many more scholars, critics, and writers.

A previously unpublished poem by Dorothy Wordsworth (poet, sister, and muse of William), “Lines addressed to my kind friend & medical attendant, Thomas Carr,” is on the Oxford University Press blog. Wordsworth was, at the time, suffering from arteriosclerosis and dementia.

September 17, 2013

Sacrosanct

The cement was dirty, but so were my pants after three weeks of traveling. I lay down on the sidewalk in front of the Sagrada Família, stretching back to look up at the Nativity Façade, trying to capture most of my older sister and all of the spires in my camera’s viewfinder.

Sagrada Família is one of the most beautiful churches that I have ever seen; it is also one of the few that I have seen under construction. Not renovation or restoration, but construction. Since 1882, except for a brief interruption caused by the Spanish Civil War, this church has been the constant, but hurried home of masons and stonecutters, carpenters and sculptors, architects and electricians. On any day, a few hundred might be working inside and outside its walls; every month, church authorities spend over a million euros on construction.

The church, like the tourists who scuttle about its lower crypt and the worshippers who bow their heads and fold their hands in its central nave, is in a state of becoming, not being. The most famous hands to touch the church were those of Antoni Gaudí, who took over its design in 1883. When he died forty years later, less than a quarter of the church was finished.

Originally the idea of a bookseller who was inspired by his pilgrimage to Rome, Sagrada Família has always been an expiatory church, funded by donations. It is hard to estimate the total number of persons who have donated to the cause over the last one hundred and thirty-one years. Millions visit the church every year, their admission fees funding the costly construction that will continue for at least another decade.

While it is only a minor basilica, lacking the seat of a bishop, Sagrada Família calls to mind the great gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages. When I lay down on the cement in front of one of its oldest facades, looking up at my sister, I thought of the many generations that had already witnessed its construction.

I thought of the mothers who brought their sons, only to have those boys take their own children to see the magnificent basilica in the making. I thought of all the fathers who came with their grandfathers only to return with their granddaughters to see light pouring through newly installed stained glass windows. I thought of all the generations who had seen and would see this church the way generations before had witnessed the building of the great cathedrals of the world.

Gaudí wanted the interior of Sagrada Família to look like a forest. The columns of the nave stretch like tree trunks from the floor to the ceiling, branching to support the heavy weight of the ceiling, but also sprawling, reaching like tendrils for the sky. The church is beautiful because of its continual incompletion, its revelation that human construction is not so unlike natural construction: you plant a sapling as a child, then years later it is still growing into something taller, something more; your grandparents planted daffodils that decades later you see still returning every spring; you sit reading the newspaper on a bench in a park that your father tells you was once under water, the river having receded miles from its ancient reaches.

Cathedrals reveal human construction for what it is. In “The Cathedral,” Rainer Maria Rilke wrote “Their birth and rise, / as our own life’s too great proximity / will mount beyond our vision and our sense / of other happenings.” The poet disdains the possibility that cathedrals eclipse their makers: “as though that were history, / piled up in their immeasurable masses / in petrifaction safe from circumstance.” Life, Rilke argued, was on the streets beneath the cathedral’s spires, while death was “in those towers that, full of resignation, / ceased all at once from climbing.”

Inherent Vice

Paper and Salt, a blog devoted to food and literature, is consistently excellent. In a recent post, author Nicole Villeneuve draws attention to a little-discussed aspect of Thomas Pynchon’s writing: his recurring interest in Mexican food. Why, she asks? “Let’s just say he had done plenty of ‘research’ on the subject. As his friends’ memories, he was always seeking his next meal: ‘wearing an old red hunting-jacket and sunglasses, doting on Mexican food at a taco stand.’ Throughout the late 60s and 70s, Pynchon became a regular at El Tarasco in Manhattan Beach (It’s still open today, if you want to follow in his culinary footsteps). Neighbors would frequently spot him chowing down—the notorious hermit, lured into public by a burrito.”

Alas! If Pynchon does, indeed, reside in pleasant anonymity on New York’s Upper West Side, his options for good Mexican food are (as California-bred Villeneuve points out) notoriously limited. Good thing she provides a recipe for Beer-Braised Chicken Tacos.

Little Syria

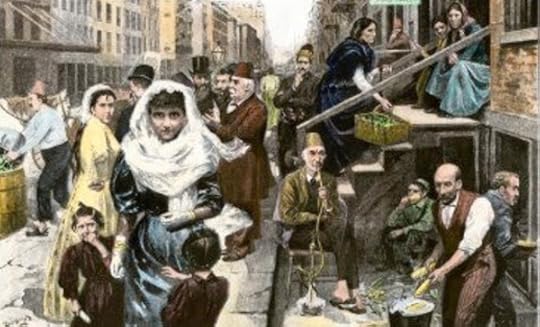

“The Foreign Element in New York—The Syrian Colony,” c. 1895

“When one leaves the hurry and roar of lower Broadway and walks southward through narrow Washington-st., the average New-Yorker of Caucasian descent might easily believe he was in the Orient. A block to the east roar the trains of the elevated. A little further eastward are the rushing throngs of Broadway. In the midst of all this tumult and confusion is situated the quiet village of Ahl-esh-Shemal.”

And so, in 1903, the New-York Tribune endeavors to take its readers into Little Syria. Concentrated on Rector and Washington Streets in the lower parts of Manhattan, Little Syria in 1895 was home to an estimated three-thousand residents from modern-day Syria and Lebanon (nearly all Middle Eastern New Yorkers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries would be referred to as Syrian or Arab, regardless of religion), most of whom had fled persecution under increasingly harsh Ottoman rule. Missionaries, dispatched to the Holy Lands to spread the Christian gospel, told tales of a city made of opportunity, ready and waiting to receive immigrants dedicated to hard work and moral living.

Philosophy Turns Violent, and Other News

During an argument over the works of Immanuel Kant, a Russian man was shot in the head. He is, shockingly, not seriously hurt, but the shooter faces up to a decade in jail for “intentional infliction of bodily harm.”

The distinguished poet Graham Nunn—former artistic director of the Queensland Poetry Festival—has apologized for serial plagiarism. After getting caught.

James Patterson: “I’m going to give away $1 million in the next twelve months or so, to help independent book stores. We’re making this big transition right now to ebooks, and that’s fine and good, and terrific, and wonderful, but, we’re not doing it in an organized, sane, civilized way. What’s happening right now is, a lot of book stores are disappearing, a lot of libraries are disappearing or they’re not being funded. School libraries aren’t being funded. This is not a good thing. It used to be you could go to your drugstore, you’d find books everywhere.”

The president of the Ohio board of education is calling for the ban of The Bluest Eye by native daughter Toni Morrison. Debe Terhar calls the 1970 novel “pornographic.” Says Morrison, “I resent it … I mean if it’s Texas or North Carolina as it has been in all sorts of states. But to be a girl from Ohio, writing about Ohio having been born in Lorain, Ohio. And actually relating as an Ohio person, to have the Ohio, what—Board of Education? —is ironic at the least.”

September 16, 2013

Tonight!

Tonight at the Powerhouse Arena: Lawrence Block, Chip McGrath, and Lorin Stein on John O’Hara, moderated by Steven Goldleaf. See you there!

Hemingway’s Hamburger

Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Fingers deep, I kneaded. Fighting the urge to be careless and quick, I kept the pace rhythmic, slow. Each squeeze, I hoped, would gently ease the flavors—knobby bits of garlic, finely chopped capers, smatterings of dry spices—into the marbled mound before me.

I had made burgers before, countless times on countless evenings. This one was different; I wasn’t making just any burger—I was attempting to recreate Hemingway’s hamburger. And it had to be just right.

My quest had begun in May when I read a newspaper story about two thousand newly digitized documents of Ernest Hemingway’s personal papers in Cuba finally wending their way to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. This was the second batch of Hemingway papers to arrive from his home in Cuba, where he lived from 1939 to 1960, and wrote numerous stories and the celebrated novels For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea.

In his Havana home—Finca Vigía, or “Lookout Farm,” a large house and sprawling tropical gardens filled with mango and almond trees—between tapping out books like A Moveable Feast (while standing up at his typewriter), he also enjoyed dining well and entertaining. The ubiquitous Hemingway Daiquiri, after all, comes from his time in Havana, when he wandered into the El Floridita bar, had his first taste of a daiquiri, then ordered another with no sugar—and double the rum. (So the story goes, anyway.)

Paradise Found

On this day in 1919, Maxwell Perkins accepted twenty-two-year-old F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise for publication. The novel had started as a shorter piece called The Education of a Personage; following a breakup with future wife Zelda Sayre, Fitzgerald became determined to achieve success and overhauled, expanded, and retitled the book (this time after a Rupert Brooke poem) while living with his parents in St. Paul. Published in March, 1920, This Side of Paradise was an instant bestseller. Scott and Zelda were married a week later.

Scottie Fitzgerald Lanahan donated the This Side of Paradise manuscript to the Princeton University Library in 1950; the library recently digitized the whole thing.

The Immortality Chronicles: Part 5

What have we not done to live forever? Adam Leith Gollner’s research into the endless ways we’ve tried to avoid the unavoidable is out now as The Book of Immortality: The Science, Belief, and Magic Behind Living Forever. Every Monday for the next two weeks, this chronological crash course will examine how humankind has striven for, grappled with, and dreamed about immortality in different eras throughout history.

In the late 1700s, a Scottish quack named James Graham, Servant of the Lord O.W.L. (Oh, Wonderful Love), became the talk of London for claiming anyone could live to 150 simply by making regular visits to his private clinic, the Temple of Health. Graham encouraged valetudinarians to rub themselves with his patented ethereal balsam. He also advocated earth baths, in which naked patients climbed into holes in the ground and were covered neck deep in mud. He spoke of the salutary effects of thoroughly washing one’s genitals in cold water or, even better, in ice-cold champagne. His most in-demand device, however, was the celestial bed, a massive stallion-hair-filled mattress supported by forty glass pillars that administered mild shocks of electrical current. Graham’s clients hoped the effects of “holding venereal congress” in the bed would cure barrenness—or at the very least help them live longer, if not forever.

Graham was only forty-nine years old when he died in 1794—a pivotal, auspicious year in the history of immortality. It was the same year that Blake engraved his Songs of Innocence and Experience with lines about being a happy fly whether he lives or dies, about immortal eyes in forests of night, about “that sweet golden clime / where the traveler’s journey is done.” What Graham sought in the physical, Blake found in the mystical. His visions showed him “what eternally exists, really and unchangeably,” that “which liveth for ever.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers