Sophfronia Scott's Blog: Sophfronia Scott, Author, page 32

September 15, 2012

My Essay in Numero Cinq

I have an essay, “White Shirts,” published this week in the online literary journal Numéro Cinq. It’s about a walk with Lena Horne; it’s about ironing; it’s about my dad. It’s about a lot of things! I am delighted, excited and just plain giddy. Please read and comment on the site at this link. While you’re there enjoy the whole issue. Every piece in Numero Cinq is gorgeous and well-chosen by the amazing author Douglas Glover. I hope you enjoy the piece and I can’t wait to hear what you think.

I have an essay, “White Shirts,” published this week in the online literary journal Numéro Cinq. It’s about a walk with Lena Horne; it’s about ironing; it’s about my dad. It’s about a lot of things! I am delighted, excited and just plain giddy. Please read and comment on the site at this link. While you’re there enjoy the whole issue. Every piece in Numero Cinq is gorgeous and well-chosen by the amazing author Douglas Glover. I hope you enjoy the piece and I can’t wait to hear what you think.

September 10, 2012

Book Review: Water and Abandon

Water and Abandon by Robert Vivian

Water and Abandon by Robert Vivian

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Disclosure: The author of this book is a mentor and friend. (In fact, there’s a picture of us in the header of this blog.) But as someone who has closely read all of his novels I believe I can offer a clear-eyed take on the style and structure of his work without fear of bias. So, here’s what I have to say about Water and Abandon.

What is the shape of grief? For Hank Little, whose 17-year-old daughter Kelsey went missing and was found drowned in the Sicangu River one year prior to the opening chapter of Water and Abandon, it is “the apostrophized arch of her foot” dragging a shredded white plastic bag when divers pulled her body from the water. For his wife Sam, it is the evaporated form of an intimacy she once thought she possessed with her cherished daughter. But when an autopsy reveals Kelsey was nearly four months pregnant at the time of her death, Sam realizes she has more than one apparition to contend with. For Javier Martinez, Kelsey’s boyfriend and father of her unborn child, the shape of grief lay in “the dunes of her tight backside or the little dimpled skulls of her kneecaps” and in her bright, shining love that he thought would save him from a hopeless future. In their contemplation of their grief the characters of Robert Vivian’s fourth novel allow their lives to deteriorate until the anniversary of Kelsey’s death demands that they account for the lost year. There is a reckoning of sorts happening here and we walk through it with them questioning whether or not things will be any different for them in another twelve months’ time.

Reading this book is akin to an ongoing meditation as the characters focus hard on their grief and swing back and forth between water and abandon. The “water” is the Sicangu River and all the dead it envelopes. It is as much a character in this novel as any two-footed being, and it holds, soothes, heals and lies just as effectively. The only one who knows this for certain is Ike Parrish, a veteran of the Korean War, who lives a reclusive existence near the river and believes his epileptic seizures are actually “river spells” that allow him to know all that the Sicangu has taken into it, including what happened to Kelsey. The “abandon” is twofold: first, it involves the many instances of Hank, Sam and Javier throwing themselves into extreme experiences, physically and mentally, thinking it will somehow get them to the other side of their grief. Next, it is actual abandonment: Kelsey mysteriously walking away from her family, Hank and Sam virtually abandoning their marriage, Javier abandoning all the good he did while he was with Kelsey, and Kelsey ignoring a dying man’s pleas for her to abandon him.

Vivian’s writing, as always, has a quiet, devastating beauty about it. One can’t help but feel the pain when Sam rushes to the attic in her house because she thinks she hears her daughter calling her:

“But Kelsey was going away even as she was making her way toward her, the light getting smaller and smaller like the rolling of a pencil diminishing with every precious millimeter of turning though the word and the cry kept their bell-tone brightness even as it faded, Sam reaching out to the narrowing spindle of light fast approaching the vanishing point a few seconds before Kelsey’s voice went silent and Sam was left reaching out to nothing in the sudden darkness of the attic, the pinpoint of light gone like a switch turned off somewhere in heaven.”

The downside to reading such gorgeous work is it can be emotionally exhausting as we watch the author dissect these people’s hearts with such aching surgical precision. Plus, Vivian constantly challenges us to take on more and more of what his characters are feeling. This especially happens in the parts of the narrative where he makes us privy to Kelsey’s thoughts and actions in the weeks before her death. We’re put in the uncomfortable position of being like Ike Parrish—we have information the other characters don’t have and we want to give it to them to assuage their grief, but we can’t. There’s also the sad realization that even if we could tell Hank, Sam and Javier what we know, it may not really help. Perhaps that’s Vivian’s point: to show us that with this kind of grief nothing can help, no one can help. These broken characters can only commiserate with those who know the same kind of loss.

The one aspect of this well-crafted novel I would question is the use of these portions written from Kelsey’s point of view. They are wonderfully written, but I believe Kelsey is more present in her absence, just as the powerful personality of the deceased Rebecca is in the Daphne du Maurier novel. The characters in Water and Abandon are not just missing Kelsey—they are missing the way she loved them, the way she moved other people, the way she had of being in the world that formed a necessary light and hope for them. The person who inspires that kind of emotion is already at once real and alive. We don’t need to know more than that even if she is telling us in her own words. In the end the shape of grief is the shape of Kelsey herself. The author can trust that, in showing us the depths of her loved ones’ suffering, he has already drawn her well enough for us to see her and know her for ourselves.

August 30, 2012

Your Writing: What’s It To You?

The Fall 2012 issue of Glimmer Train (Issue 84) opens with the following quote:

The Fall 2012 issue of Glimmer Train (Issue 84) opens with the following quote:

“You do get to a certain point in life where you have to realistically, I think, understand that the days are getting short and you can’t put things off, thinking you’ll get to them someday. If you really want to do them, you better do them…So I’m very much a believer in knowing what it is that you love doing, so that you can do a great deal of it.

You know when my close friend died, you know–we always played the game, What would your last meal be? Mine happens to be a Nate ‘n Al’s hot dog. But Judy was dying of throat cancer, and she said, I can’t even have my last meal.

And that’s what you have to know: If you’re serious about it, have it now. Have it tonight, have it all the time, so that when you’re on your death bed, you’re not thinking, Oh, I should have had more of Nate ‘n Al’s hot dogs.” –Nora Ephron (May 19, 1941-June 26, 2012) interviewed on NPR November 9, 2010.

Reading this was, for me, one of those wonderful instances of discovering someone had put words to a nameless thing I’m trying to express in my life. The “thing” is nameless because I’m acting on raw emotion and instinct. If you asked me to explain in detail you may or may not know what I’m talking about. But the late Ms. Ephron has given me, through her wisdom, an opening here. Two of her points struck my heart with a painful clarity:

knowing what it is that you love doing

do a great deal of it

I’ve known my responses to these two points for a long time: I know I love writing–my writing. I know I want to do a great deal of my writing. My problem has always been the question, How do I make it happen? The funny thing is, I’ve also had the answer–my answer– for a while: enroll in a masters program and get an MFA in creative writing.

However I didn’t do it for years because whenever I spoke about the idea someone would usually say, “You don’t need to do that, you’ve already published a novel.” Or they would talk about the endeavor being a waste of money. I would listen to these thoughts, put aside the concept of getting an MFA, and keep floundering along on my own. But, finally, early last year I began gaining confidence in my thought process which was this: There are certain things I want to accomplish as a writer; there’s a way I want to “show up” in the world as a writer. I also wanted a supportive community of writers/friends/teachers and I wanted them to inspire, encourage, and challenge me to write what I’ve never written before.

When the Vermont College of Fine Arts invited me to an open house in the spring of 2011 I went and after just one day on the Montpelier campus I came away with a handful of story ideas and a poem. I hadn’t written a poem since college! The experience confirmed everything I had suspected: my heart hungered for this learning. I needed it for me; it was what I wanted for my writing. It didn’t matter how little it made sense to anyone else.

When the Vermont College of Fine Arts invited me to an open house in the spring of 2011 I went and after just one day on the Montpelier campus I came away with a handful of story ideas and a poem. I hadn’t written a poem since college! The experience confirmed everything I had suspected: my heart hungered for this learning. I needed it for me; it was what I wanted for my writing. It didn’t matter how little it made sense to anyone else.

The loss of a close family member added urgency to my quest, increasing my awareness of, as Ms. Ephron put it, the days getting short. Suddenly I had no patience for all the reasons I didn’t need an MFA. I decided to focus on my reasons why I did.

Recently I heard from a writer considering attending VCFA, and the person commented, “I’m not sure I can see spending 40k.” That’s okay. We each make our choices depending on what we can “see.” I see the writer I want to be. I don’t particularly care about the money–I’ve had student loans before and I don’t mind having them again. I can’t put a price tag on what VCFA means to me. It has been less than a year and already I’ve grown more and produced more as a writer than I have in my previous five years. I love the people around me, teachers and students, and my life is different because of them. A friend, after seeing a photo of me writing at my VCFA summer residency, commented, “I love it! You are in your joy!” Yes. She is absolutely correct. To quote the MasterCard commercial, all this to me is priceless.

Recently I heard from a writer considering attending VCFA, and the person commented, “I’m not sure I can see spending 40k.” That’s okay. We each make our choices depending on what we can “see.” I see the writer I want to be. I don’t particularly care about the money–I’ve had student loans before and I don’t mind having them again. I can’t put a price tag on what VCFA means to me. It has been less than a year and already I’ve grown more and produced more as a writer than I have in my previous five years. I love the people around me, teachers and students, and my life is different because of them. A friend, after seeing a photo of me writing at my VCFA summer residency, commented, “I love it! You are in your joy!” Yes. She is absolutely correct. To quote the MasterCard commercial, all this to me is priceless.

Only you can know if you would value such an experience, or if this is even what you want or need as a writer. It is worth asking, though, so you can get what you need and begin having a “great deal” of what you love in your life all the time.

So…What do you want as a writer and how much is it worth to you?

Sophfronia

August 10, 2012

Traveling at the Speed of Write

I feel I need to writer faster. And it’s not because I have deadlines looming (which I do) and it’s not because I’m writing at a snail’s pace–I’m really not. It’s because I’m in this place where writing is leading to more writing. Ever since I started the MFA in Writing program at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, I’m having more ideas and more work I want to produce. The projects currently jostling for space in my brain include a novel, an emotionally hefty personal essay and a short story. There’s more percolating, but those three pieces are under my fingers right now. Make no mistake though: I want to get to the percolating ones too.

I feel I need to writer faster. And it’s not because I have deadlines looming (which I do) and it’s not because I’m writing at a snail’s pace–I’m really not. It’s because I’m in this place where writing is leading to more writing. Ever since I started the MFA in Writing program at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, I’m having more ideas and more work I want to produce. The projects currently jostling for space in my brain include a novel, an emotionally hefty personal essay and a short story. There’s more percolating, but those three pieces are under my fingers right now. Make no mistake though: I want to get to the percolating ones too.

Many writers tend to think in terms of speed and flow. The work comes either quickly and easily or it doesn’t. When it’s slow and difficult we start dreading writer’s block. But what’s really happening when we speed up or slow down with our writing? I think this is worth figuring out if only so we don’t beat ourselves up on the hard days. Here’s what I learned about my writing speed. I hope it helps you learn about yours.

First of all, I should say there is a virtue to writing quickly. I tell students in my classes and workshops all the time about how the first draft doesn’t have to be pretty, that they can just bang it right out. The initial writing is the hard part–rewriting is relatively easy. However the speed thing hasn’t been working out for me. Earlier this week I noticed something was interrupting my “bang it out” process. I decided to go to the library one afternoon so I could observe myself for a few quiet hours as I wrote as fast as I could. At first I thought I would be slowed by trying to write too perfectly, but no. I was letting the cliches roll and leaving plenty of awkward sentences to be tended to later. My page count grew.

Then I had one of those light bulb moments when I realized a certain action happening in my story would be better performed by a different character. The change opened up a wonderful range of possibilities and connected well with my overall theme. This is when the process slowed. Instead of writing fast, I had a puzzle to solve and the puzzle put the brake on my work. It was like playing “Tetris,” that computer game where you try to place blocks of various shapes as they fall from the top of the screen. When you fill a line of blocks, the line quickly disappears as more blocks fall. I couldn’t write so fast while playing Tetris on the page. As I wrote through my new idea I could see pieces of the puzzle falling all over the place. I would catch them, rearrange them. Sometimes I would have to turn or flip a piece to get it to fit into the puzzle. Once I got all the blocks filled in I could fly and write quickly again. But soon more pieces would fall and I had to slow down and go back to working the puzzle.

Then I had one of those light bulb moments when I realized a certain action happening in my story would be better performed by a different character. The change opened up a wonderful range of possibilities and connected well with my overall theme. This is when the process slowed. Instead of writing fast, I had a puzzle to solve and the puzzle put the brake on my work. It was like playing “Tetris,” that computer game where you try to place blocks of various shapes as they fall from the top of the screen. When you fill a line of blocks, the line quickly disappears as more blocks fall. I couldn’t write so fast while playing Tetris on the page. As I wrote through my new idea I could see pieces of the puzzle falling all over the place. I would catch them, rearrange them. Sometimes I would have to turn or flip a piece to get it to fit into the puzzle. Once I got all the blocks filled in I could fly and write quickly again. But soon more pieces would fall and I had to slow down and go back to working the puzzle.

Okay, now I know: this is my process, with fiction anyway. Sometimes I will be fast, sometimes not, especially as I see patterns developing in my story and I work to capture all these pieces of light. The next step? Learning to accept my process and be patient with myself, knowing I’ll complete the work as long as I remain persistent. What do you have to learn about your process and how fast you write?

Let me know and then? Keep writing!

August 5, 2012

Book Review: The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

The writing in this book is wonderfully subtle. It’s as though Carson McCullers spends the whole novel chopping quietly away at a grand old oak tree. You don’t realize so much is happening in the small everyday acts of these characters until the end when the whole tree comes down, leaving everyone shocked and sad and hyper-aware of a vast emptiness left behind.

The novel centers around John Singer, a deaf-mute who lives happily contented with his best friend, another deaf-mute, until the friend goes insane and must be institutionalized. Singer moves into a boarding house and becomes the receptacle for the dreams, thoughts, rants and loneliness of the rest of the main characters in the book including young Mick Kelly, the teenage girl whose family owns the boarding house, Dr. Copeland, the town’s only black doctor, Biff Brannon, a restaurant owner, and Jake Blount, a drunk mad with his ideas about how society should work. They all talk and talk at Singer, sometimes to his bewilderment, but none of them listen to him. Then, when tragedy strikes, they are all shocked and surprised. Isn’t that how life usually works, in too many sad and awful ways to mention?

I enjoyed The Heart is a Lonely Hunter for McCullers’s well-observed scenes and the thought-provoking clarity with which she sees the predicament of each of her characters. The way she develops this languid world of the south, layer upon layer, with sights, sounds, smells and the overall feeling of impotent dreams and disappointed hopes is truly a marvel to behold. I shall remember always the many small gestures that I found so touching as to be heartbreaking: the way Singer would look earnestly into the face of his friend before they parted each day to go to work; Mick spray painting the names of her idols on the walls of a house and then lying up on the roof so she could make her plans; Dr. Copeland wanting so much to reach out to his family, but being tongue-tied as though he and they would forever speak a different language; Biff Brannon dotting his dead wife’s perfume to his temples and absorbing the memories of when he had loved.

I highly recommend this book with the hope that each person who reads it will come away pondering the state of their own “inside rooms,” and take care to tend and spend time in that cherished space.

August 2, 2012

My Big Fat Writing Journal

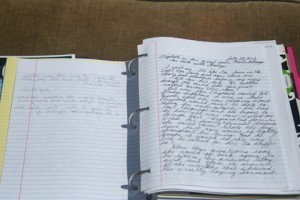

If you saw me on campus last month at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, chances are you saw my writing journal too. It’s a huge blue binder and I pretty much carried it everywhere until the sun went down–then I left it in my dorm room and gave it a rest. A few of my classmates have marveled at this monstrosity but until now I haven’t answered the burning question: What the heck’s in that thing? I will today. I discovered this journal system early last year and I’m sharing it here just in case you’re a creative like me (visual, tactical, very old school) looking for a way to keep your writing life organized. I learned it from Louis E. Catron in his book Playwriting: Writing, Producing, and Selling Your Play. Dr. Catron, who passed away in 2010, taught playwriting at the College of William and Mary and he required his students to keep binder journals. He wrote:

If you saw me on campus last month at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, chances are you saw my writing journal too. It’s a huge blue binder and I pretty much carried it everywhere until the sun went down–then I left it in my dorm room and gave it a rest. A few of my classmates have marveled at this monstrosity but until now I haven’t answered the burning question: What the heck’s in that thing? I will today. I discovered this journal system early last year and I’m sharing it here just in case you’re a creative like me (visual, tactical, very old school) looking for a way to keep your writing life organized. I learned it from Louis E. Catron in his book Playwriting: Writing, Producing, and Selling Your Play. Dr. Catron, who passed away in 2010, taught playwriting at the College of William and Mary and he required his students to keep binder journals. He wrote:

“The well-maintained writer’s journal is the writer’s constant companion, confidant, receptacle for ideas, storehouse of projects, and stimulus for further writing. For writers, the journal becomes an indispensable file system. The journal also contributes to the writer’s psychological well-being, providing an essential support system of reassurance and comfort, because it makes no demand upon the writer. ”

He recommended the binder format because “this will allow the writer to move materials easily from one section to another” and “the bound log or the spiral notebook…lack the versatility of the three-ring notebook.” Yes, Dr. Catron admitted, it’s cumbersome carrying the thing everywhere but “soon it will fit naturally under your arm.” Indeed that’s what I’ve found. At VCFA, when I wasn’t writing in it, my journal was always under my arm or in my roomy red L.L. Bean messenger bag (which I purchased specifically because the journal fit into it).

He recommended the binder format because “this will allow the writer to move materials easily from one section to another” and “the bound log or the spiral notebook…lack the versatility of the three-ring notebook.” Yes, Dr. Catron admitted, it’s cumbersome carrying the thing everywhere but “soon it will fit naturally under your arm.” Indeed that’s what I’ve found. At VCFA, when I wasn’t writing in it, my journal was always under my arm or in my roomy red L.L. Bean messenger bag (which I purchased specifically because the journal fit into it).

What’s in my writing journal? Everything, as you’ll soon see. It’s like my writing brain, warehousing both structured and random thoughts. If I’m ever stuck, the answer is in here. Do I need a bit of inspiration? It’s in my journal. It makes sense to me, and I think that’s the most any writer can ask of an important writing tool. So here, divider tab by divider tab, is what’s in my journal. Some of the categories were suggested by Dr. Catron and I’ve kept them. Others are my personal additions based on how I work.

Let’s start with the cover: it features my name in big lettering, just in case I do leave it somewhere. I love this image of a violin. It’s my reminder that my writing is my music, and it’s what I sound like when I “sing.” Inside the front cover is my contact information and another inspiring image, this one of the dawn. It’s my cue to get up and write. Now for the tabs, which I’ll number.

In Progress 1: This section features material from the novel I’m currently writing. It contains my outline, notes, photographs that remind me of my characters and yes, actual writing. I’m still old school and while I do write on computer, I almost always begin on paper.

In Progress 1: This section features material from the novel I’m currently writing. It contains my outline, notes, photographs that remind me of my characters and yes, actual writing. I’m still old school and while I do write on computer, I almost always begin on paper.In Progress 2: I’m revising a short story and its full manuscript is here. I also have notes in this section on the project that will replace the short story under this tab when the revision is done.

Scenario: These are notes for my next major work. Dr. Catron was very much all about having the writing journal keep you forward thinking.

Character Sketches: Here I put personality profiles for each of my characters. I’ll also write down ideas for characters I may create in the future.

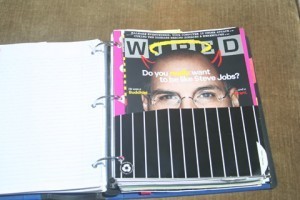

News Clippings: I have this habit from my days as a magazine journalist: I still clip articles or print up interesting stories I find online. Here you see a recent Wired magazine story that has inspired me to revise a character in my short story.

News Clippings: I have this habit from my days as a magazine journalist: I still clip articles or print up interesting stories I find online. Here you see a recent Wired magazine story that has inspired me to revise a character in my short story.Dialogue: Snippets of dialogue I hear in everyday life.

VCFA: This tab houses everything from my most recent residency at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. My lecture notes are here as well as the semester study plan I created with my advisor. During the residency it also held all of the stories being workshopped in my section, each one eventually annotated and returned to its author. When the semester is over this material will be removed to its own binder to make room for the next residency.

Situations: Interesting tidbits that have the potential to become full-blown stories.

Credo: This one is Dr. Catron’s idea, but I like it and I’ve filled it accordingly. His definition: “A credo is, simply, a personal statement of convictions. A credo is the writer’s beliefs concerning topics he or she feels are highly important…about which the author has a deep emotional attitude–a burning anger, a scorn, an affection….It is uniquely your own.”

Quotes/Excerpts: Piece of writing (and sometimes images) from songs, poems, or prose I find inspiring. There’s some Regina Spektor here, also Bruce Springsteen, Walter Mosley and Rumi.

Quotes/Excerpts: Piece of writing (and sometimes images) from songs, poems, or prose I find inspiring. There’s some Regina Spektor here, also Bruce Springsteen, Walter Mosley and Rumi.Calendar: Each month I write out my goals and deadlines here. I also give myself star stickers each day as my reward for writing. Seriously.

Notes from Self to Self: This section is for diary-like entries where I’m turning over situations in my mind or venting frustrations.

To Read: Yes, my current reading list. I print this up from Goodreads where I maintain all of my book lists.

Submissions: My spreadsheet of where I’ve sent stories for publication.

VCFA Semester Work: In addition to my creative work, I also have to write critical essays and letters of progress. The notes and drafts for that work go here.

In the back you’ll see my handy-dandy portable three-hole punch which I use for handouts or anything else not written on notebook paper. That’s my journal.

In the back you’ll see my handy-dandy portable three-hole punch which I use for handouts or anything else not written on notebook paper. That’s my journal.

Could I keep all of this information in a computer? Yes. Would that work? No. Things stored on a computer become out of sight, out of mind for me. My writing journal has its own table in my office and it’s always open to what I’m working on. Yesterday while cleaning house I had an idea for a piece of dialogue. I ran downstairs, wrote it into my open journal, then went back to my cleaning. I would not have booted up my computer for a few sentences and it’s possible I would have scribbled those words on the back of a random envelope and lost them. In that moment my journal did exactly what I needed it to do. It worked for me. What works for you? I’d love to hear about your writing journal and how you use it.

July 25, 2012

The Anatomy of Strength

“How did you get to be so strong?”

“I wish I had your strength.”

I’ve heard these comments or some variation on them many times throughout my life. The person making the comment is usually responding to how I handled a tragedy or how I got through a difficult situation that they believe would have floored them at worst, or rendered them useless at best. It’s also been pointed out to me there’s a fearlessness about my writing and how it must certainly come from a point of strength. Recently someone asked me, yet again, “the strength question” and I thought about it carefully because I wanted to give as clear an answer as possible. I came up with these two pieces:

1.) In most cases I am strong because the people I love require it of me.

2.) I am strong because often I have no choice to be otherwise. Is there really an alternative?

This answer served well in the moment, but when you consider the real reason the person was probably asking the question—they are trying to do the same or be the same way—the answer in fact fails because I didn’t tell them how to do it.

Process is important. As a teacher of writing and as a student I know I teach and learn best when I can figure out and explain the specifics of how I or another writer did something. Answering this question of strength with a basic, specific process could be the beginning of unlocking something vital for you—as a person and as a writer you will be called upon to take many emotional risks.

I’m writing about this today because lately I’ve had to deal with something that calls upon me to be my “strong” self. I recognized this immediately and I’ve been paying close attention to my process during this time so I can share with you how I’m doing it. I hope somehow this will help you find your own strength when you need it.

A friend has asked me to do something very difficult. I won’t go into the details because I want you to be able to read your own situation into this. Maybe you are terribly afraid of hospitals, but your dear friend wants you to accompany her to her chemo treatments for the next 8 weeks. Maybe you don’t like dogs but your friend is suddenly called away to care for a sick parent and you’re the only one who can take her dog for an indefinite period of time. You get the idea: you have to do something really hard, but you’re not exactly in a position to say “No.” You have to be really strong—you have to come outside of yourself to be the person your friend needs in that moment. Someone you love requires it, and you really have no choice. How are you going to get through it?

My process begins and ends with love. I don’t mean you simply think, “I love this person so of course I’ll do it.” That thought might get you started—it’s even what makes you say, “Yes” to your friend’s request. But in the thick of battle your first thought will soon become, “Why am I putting myself through this?” You might keep going but you won’t be strong and your friendship will suffer for it.

I mean you have to sit down and do the specific work of stoking the embers of your friendship’s love. I make myself actively feel why I love this person. Here’s how I do it. I have a mind that responds to repetition. I will go through photographs, re-read e-mails and letters (yes, for close friends, I have such things on hand) and I run through my head, like a movie, memorable loving times we’ve had together. My motivation, strength and faith rise to the surface.

It’s funny, but I really think my learning in this began from watching soap operas. It used to perplex me how the show would feature this loving super couple who had endured landslides, kidnappings, aliens, you name it. They would survive and get married, but the moment a possible rival appeared all the stuff they went through went out the window and a person would start fretting they’d lose their spouse. Their mind was too busy processing misleading signals in the present moment. If they had allowed their heart to guide them, they would have been grounded, comforted and confident based on all the loving acts that served as their relationship’s hard-built foundation.

The same foundation exists for friendships—if this is a close friend, someone you love, I’m assuming your friendship is built on a significant foundation of words, actions and memories that made you cherish the person in the first place. That stuff doesn’t go away. It’s in the “emotional bank,” as Stephen Covey called it in The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. A close friend will have made many, many deposits.

Your recalling the foundation of your friendship is kind of like what the participants do to get ready to walk over the hot coals at a Tony Robbins event. You want to get the heart pumping, the blood flowing and you psyche yourself up so you can do anything, including walking over hot coals without getting burned. I’m doing this now: I’m immersing myself in the love. It’s both a coat of protection and the thing that takes the focus off my fears and me and puts it firmly on my friend to the point where I’m willing to shoot myself out of a rocket for him or her. My thoughts are now, “I will do this because that’s how important my friend is; this is how much this friendship means to me. I believe in my friend.”

Your recalling the foundation of your friendship is kind of like what the participants do to get ready to walk over the hot coals at a Tony Robbins event. You want to get the heart pumping, the blood flowing and you psyche yourself up so you can do anything, including walking over hot coals without getting burned. I’m doing this now: I’m immersing myself in the love. It’s both a coat of protection and the thing that takes the focus off my fears and me and puts it firmly on my friend to the point where I’m willing to shoot myself out of a rocket for him or her. My thoughts are now, “I will do this because that’s how important my friend is; this is how much this friendship means to me. I believe in my friend.”

So I, or you, do the thing, whatever it is. And you get through it.

That’s when the questions from others begin: “How could you be so strong? Weren’t you afraid?”

By then, when it’s all over, you probably won’t even remember you asked this yourself at one point. You shrug your shoulders—you only did what you had to do.

July 20, 2012

Why I Live My Writing Life

My friend Jenny, when her son was a toddler, used to say that taking a nap was the most rebellious thing a person could do. I knew exactly what she was talking about. When you nap, you do it despite all the other things you know you should be doing instead. You know the nap will make you feel better, make you more yourself. At the same time you sense that if it feels that good, it must be bad. The little girl in me says, “I’m going to get into trouble.”

Writing is like that for me. I mean my writing—not ghostwriting for clients, not blog posts for my business, not the press release for my husband’s house concert. When I write my writing I am wielding magic: I wave my mystic keyboard and people think differently, or they cry or laugh. I love it. I feel joyous, I feel like myself. I wonder what I can do next. When I have spent a day living my writing life I have spent the morning writing and the evening reading and I feel like I’ve gotten away with something. I feel like my father will come into my office and yell about the dishes not being washed, as he used to do to my siblings and me. So I used to tell myself I would do my writing when everything else was done.

But here’s the thing: everything else is never done.

I would deny myself a little bit everyday and it got to the point where the very nature of what I did had nothing to do with who I am. I had to ask myself, “How do I get back to me, to my writing life?” I found the answer in my convertible. A few years ago I bought a used Mazda Miata. One day, when I no longer worked a 9-to-5 job, I realized I could hop in the Miata and go for a ride up Manhattan’s West Side Highway. With the top down, the sun shining, and the radio blaring I sped along and then I felt it–an awful tingling swirling around in my stomach that warned, “I’m going to get into trouble”. I almost jammed on the brakes! I decided I would have to claim my joy of this car by riding it every single day until the feeling went away.

I would deny myself a little bit everyday and it got to the point where the very nature of what I did had nothing to do with who I am. I had to ask myself, “How do I get back to me, to my writing life?” I found the answer in my convertible. A few years ago I bought a used Mazda Miata. One day, when I no longer worked a 9-to-5 job, I realized I could hop in the Miata and go for a ride up Manhattan’s West Side Highway. With the top down, the sun shining, and the radio blaring I sped along and then I felt it–an awful tingling swirling around in my stomach that warned, “I’m going to get into trouble”. I almost jammed on the brakes! I decided I would have to claim my joy of this car by riding it every single day until the feeling went away.

With my writing the question was the same. Could I claim my joy and live the writing life enough to master the feeling?

So I declared war of a sort by determining the writing life is the way I am going to live my life from now on. Attending the Vermont College of Fine Arts, as I do now, is the equivalent of me staging my very own French Revolution.

So I declared war of a sort by determining the writing life is the way I am going to live my life from now on. Attending the Vermont College of Fine Arts, as I do now, is the equivalent of me staging my very own French Revolution.

I live the writing life because it’s the most rebellious thing I can do. I live the writing life because it is when I am most myself.