Alex Quigley's Blog, page 7

June 29, 2024

How to do disciplinary literacy?

How pupils read, write, talk, and the vocabulary they use in every classroom is specialist and unique. There are general words and literacy strategies to deploy, but as pupils move up through school, the language they use gets more specialist and subject specific. As a result, the language of the subject discipline matters.

'Disciplinary literacy' matters.

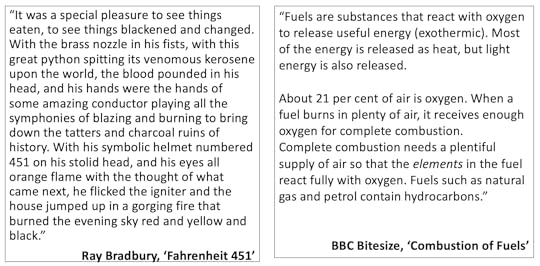

Take a moment to quickly read the two following texts:

What do you notice?

Both texts are ostensibly describe fire, but their language mediates that concept in very different ways. The fiction text by Ray Bradbury is a tour de force description full of imagery and action verbs. By contrast to the literary text, the BBC Bitesize extract deploys the more abstract language of science. You notice the different vocabulary choices, sentence lengths, grammar choices, and much more.

For a skilled reader, we can read both texts so automatically that we do not quite notice the different language, the background knowledge we activate as we read, or the different reading moves undertaken. In concrete terms, disciplinary literacy is the act of explicitly paying attention to those subtle but vital differences. For a chemistry teacher, it is important to teach the language of science with explicitness because it is so unique and often far away from the everyday language pupils use.

Disciplinary literacy is nothing new. In 1975 - nearly 50 years ago - The Bullock Report stated "a policy for language across the curriculum should be adopted by every secondary school." Arguably, disciplinary literacy has struggled to take hold ever since. Too often perhaps, we have assumed a literacy coordinator, or a reading lead, had too much responsibility, but too little knowledge of the different subject disciplines to actually support a range of teachers across the school.

Disciplinary literacy might matter, but it clearly proves difficult to implement successfully.

Doing literacy differently"As students progress through an increasingly specialised secondary school curriculum, there is a growing need to ensure that students are trained to access the academic language and conventions of different subjects. Strategies grounded in disciplinary literacy aim to meet this need, building on the premise that each subject has its own unique language, ways of knowing, doing, and communicating"

EEF, Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools

Implementing disciplinary literacy effectively is a collaborative effort. Given the importance of subject expertise in deciphering how to read, write or talk in a given subject domain, any literacy coordinator or school leader, is unlikely to have all the answers. Done well, and done collaboratively, disciplinary literacy can offer pupils a set of tools to crack open the curriculum.

For those seeking to lead disciplinary literacy, it makes sense to solve the problems pupils face when they are grappling with difficult reading or writing tasks. We can ask teachers to share maths word problems, or exam questions, that have proven uniquely tricky. Then we can scrutinise what exactly is it that makes the reading specifically challenging. For example, in maths, we can identify some of the problems that attend reading must-step word problems, such as:

Pupils can find it difficult to move between text and graphics.

Pupils can find maths vocabulary difficult given some words have highly specific meanings only found in maths (e.g. isosceles), whereas other words have very wide common use but a different meaning in maths (e.g. prime, factor). Alongside this, some maths terms sound like familiar words, but are not (pi – not pie!).

Pupils have to interpret words to find the appropriate mathematical symbol, so ‘increase’, ‘positive, ‘add’ and ‘more’ can denote ‘+’.

Pupils can easily confuse related mathematical terms, e.g. denominator and numerator.

(from 'Closing the Reading Gap')

For busy maths teachers, we can identify disciplinary reading challenges and go about collaborating with 'reading in maths' (see my blog on 'Does reading really matter in maths?'). Thus, disciplinary literacy becomes concrete - solving real problems for busy teachers.

What I have observed in the last year or so are lots of blogs by teachers who are doing disciplinary literacy and explaining how they have done it. Take a look at the following:

' How to develop disciplinary literacy in maths ', by Elizabeth Bridgett.' Exploring disciplinary literacy in science ', by George Duoblys. ' What is disciplinary literacy and how can we embed it? ' by Johnny Richards. ' Exploring disciplinary literacy in maths ', by Amarbeer Singh Gill. ' Disciplinary literacy: Reading in subject disciplines ', by Mark Miller.' Using dialogue to secure scientific understanding ', by Kate Walter. ' How I teach extended writing in science ', by Dr. Jo Castelino. ' Improving primary science: Developing pupils' scientific vocabulary ', by Jody Chan.My literacy content and engagement specialist at the EEF, Chloe Butlin, has also developed a handy tool to begin discussing and implementing disciplinary literacy. 'The Disciplinary Literacy Tree' is an interactive resource, which also includes a useful discussion prompt for secondary school colleagues, for those wanting to start talking and doing disciplinary literacy.

June 15, 2024

Adaptive teaching or reasonable adjustments?

“Is adaptive teaching the same thing as ‘reasonable adjustments’?”

I get asked this question often when working with teachers and leaders on developing adaptive teaching. It is no surprise, given they can often appear similar when applied to classroom practices that support pupils with learning needs. It is helpful for busy teachers to know some of the parallels, but also to be clear about some of the differences.

What are reasonable adjustments?

‘Reasonable adjustments’ are specific changes that are made to a child’s life at school so that they are not disadvantaged compared to their peers. It is commonly used to describe approaches taken for supporting children with SEND. More specifically, in British law, it is about the changes made to support a disabled child.

The Department for Education describes reasonable adjustments as approaches that schools and teachers can take to do things differently to ensure we ultimately treat pupils equally. For example, reasonable adjustments can include:

a pupil with a visual impairment sitting at the back of the class to accommodate their field of visiona pupil struggling with severe dyslexia can be given a laptop to support their writing.There are an array of small, carefully chosen adjustments that can have a beneficial impact on pupils that can be classed as reasonable adjustments, but they could just as easily be classed as adaptive teachingapproaches in the repertoire of teaching supporting all pupils to learn with success. For instance, the British Dyslexia Association suggest reasonable adjustments for pupils that can include:

Repeat instructions/information and check for understanding of tasksBreak information down into smaller ‘chunks’Encourage peer support to record homework tasks in the planner.For many teachers, these approaches would commonly be described under the umbrella adaptive teaching (or more specifically, ‘microadaptations’). Lots of people would, with good claim, describe them plainly as 'just good teaching'! It is clear that they don’t seem specialist or ‘different’ enough for what we typically consider to be reasonable adjustments. Though the differences start to get a little fuzzy, these subtle approaches can be of great value, so they are worthy of allocating time to define and deploy effectively.

Some differences between adaptive teaching and reasonable adjustments

The more typical reasonable adjustments we consider when we think about supporting pupils with dyslexia include extra time in exams, laptops for writing, or other tech supports for reading.

Many of these reasonable adjustments are crucially important. There is also, however, some myths and popular products that masquerade as necessary reasonable adjustments. For example, ‘dyslexie’ fonts were offered as a solution for struggling readers, but the research evidence didn’t back up the claims of its developers. Fidget spinners and other fads come and go. Clearly, teachers need support to separate the wheat from the chaff when it comes to tools labelled as reasonable adjustments (and it may just save a lot of expensive ‘special’ printing and spurious purchases too!).

It is helpful for teachers to consider those approaches that are likely to benefit all pupils’ learning, whilst explicitly posing advantages for pupils with specific needs. It helps moving beyond the assumptions that can attend some labels. For pupils who have dyslexia, extra time in exams may be a desirable outcome, but teachers can also make a positive difference to pupils reading in timed conditions by focusing on reading fluency practices, such as choral and ‘echo reading’. Instead of specialist fonts for such pupils, teachers can instead focus on supporting pupils with dyslexia with reading and spelling strategies such as explicit vocabulary instruction and focusing on morphology to enhance spelling and reading.

Teachers are too often short on time, so specialist knowledge of the latest additional tools can be lacking. Happily, however, some of the reasonable adjustments offered to pupils with SEND that also appear to be adaptive teaching approaches can prove of great value, but at a low cost (or more plainly, just great teaching). Both will matter and both can make a difference, so supporting teachers to consider both reasonable adjustments and adaptive teaching could prove a good use of time.

June 8, 2024

Fixing Learning with Formative Assessment

Even with the best-laid curriculum plans, classroom learning can easily go awry. A painstakingly crafted lesson plan is always at the mercy of pupils’ misunderstanding.

In his brilliant book, entitled ‘The Hidden Lives of Learners’, Graham Nuthall observed and recorded around 10,000 lessons and concluded that:

“One of the greatest enemies of effective teaching is pupil misunderstanding. No matter how well you describe something, how well you illustrate and explain it, pupils invent some new way to misunderstand what you have said.”

It is a chastening truth. They may remember that their friend joked about the ‘Peasant’s revolt’ but have scant memory for the careful explanation expertly crafted by their teacher.

A solution to these learning failures is a recognition that learning is not readily visible and that it is important to continually expose pupils’ thinking – their prior knowledge, preconceptions, misconceptions, beliefs, and more. Continuous monitoring of learning is necessary if we are to effectively seek out success or failure. Formative assessment offers up the essential information about pupils’ learning in the moment so that teachers can better discern the difference.

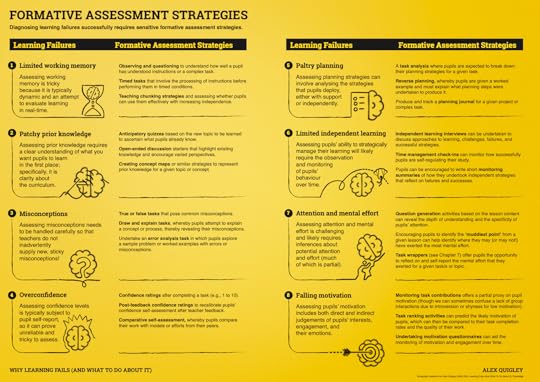

Formative assessment strategies to solve key learning failures

Formative assessment approaches are those moment-by-moment responses to the tricky issues and barriers that beset even the best laid lesson plans. They are part of the typical repertoire of expert teachers. Just some strategies include:

Limited working memory

Observing and questioning to understand how well a pupil has understood instructions or a complex task. Timed tasks that involve the processing of instructions before performing them in timed conditions. Teaching chunking strategies and assessing whether pupils can use them effectively with increasing independence.Patchy prior knowledge

Anticipatory quizzes based on the new topic to be learned to ascertain what pupils already know. Open-ended discussion starters that highlight existing knowledge and encourage varied perspectives.Creating concept maps or similar strategies to represent prior knowledge for a given topic or concept.Pupil misconceptions

True or false tasks that pose common misconceptions. Draw and explain tasks, whereby pupils attempt to explain a concept or process, thereby revealing their misconceptions. Undertake an error analysis task in which pupils explore a sample problem or worked examples with errors or misconceptions.Pupil overconfidence

Confidence ratings after completing a task (e.g., 1 to 10). Post-feedback confidence ratings to recalibrate pupils’ confidence self-assessment after teacher feedback. Comparative self-assessment, whereby pupils compare their work with models or efforts from their peers.Paltry planning

A task analysis where pupils are expected to break down their planning strategies for a given task. Reverse planning, whereby pupils are given a worked example and must explain what planning steps were undertaken to produce it. Produce and track a planning journal for a given project or complex task.Limited independent learning

Independent learning interviews can be undertaken to discuss approaches to learning, challenges, failures, and successful strategies. Time management check-ins can monitor how successfully pupils are self-regulating their study. Pupils can be encouraged to write short monitoring summaries of how they undertook independent strategies that reflect on failures and successes.Attention and miserly mental effort

Question generation activities based on the lesson content can reveal the depth of understanding and specificity of pupils’ attention. Encouraging pupils to identify the ‘muddiest point’ from a given lesson can help identify where they may (or may not!) have exerted the most mental effort.Task wrappers offer pupils the opportunity to reflect on and self-report the mental effort that they exerted for a given task/s or topic.Failing motivation

Monitoring task contributions offers a partial proxy on pupil motivation (though we can sometimes confuse a lack of group interactions due to introversion or shyness for low motivation). Task ranking activities can predict the likely motivation of pupils, which can then be compared to their task completion rates and the quality of their work. Undertaking motivation questionnaires can aid the monitoring of motivation and engagement over time.Many of these approaches are familiar to teachers, but their success requires careful application and adaptations over time. Fixing predictable learning failures and misunderstanding can be both better predicted and solved with a focus on formative assessment strategies.

You can find a high-res PDF infographic with all of these flexible formative assessment strategies on my resources page HERE. See the image below.

This blog is adapted content from my new book for teachers, ‘Why Learning Fails (And What To Do About It)’. You can find the book on Amazon HERE and on Routledge HERE.

June 1, 2024

May 31, 2024

The Problem with Past Papers

My weekend typically involves helping coach my boy’s football team in muddy fields in the far corners of North Yorkshire. It is one of those parental experiences that mingles pleasure with pain. From narrow wins to thumping losses.

Coaching is a lot like teaching. From wrangling a bunch of excitable teens to the pressure of a big game proving parallel to an exam. What the weekday training drives home is that how novices learn looks very different from the big game.

The paradox of learning can be hard to grasp: playing the big game – like sitting a mock examination – is rarely the best means to prepare for future success beyond some minimal practice of exam conditions.

With my fellow coaches, we recognised this season (after some sobering losses) that we needed to get back to basics. Drills on the absolute basics, such as passing, simple positional play, and even how to kick and tackle, were needed because in the tumult of the big game.

Effectively, novices learn differently from experts. We need to shrink the big game into learnable chunks, before overlearning these moves. Whether it is football, chess, or an English GCSE exam, the moves of the game invariably need more practice.

The past papers problem

It wasn’t so long ago that I spent most weekends away from the muddy football field and instead marking GCSE exam essays. Half of most spring holidays would be filled by the bag full of mock exam essays.

What is the problem with past papers, beyond teachers lugging home mountains of marking? The key issue is that for novice pupils, a big summative assessment reveals so many gaps in pupils knowledge and skills, you have to give scattergun feedback on lots of things.

Even when you chunk an English Literature exam into two halves, it still leaves a significant essay on a character or theme – such as Juliet or immature love in ‘Romeo and Juliet’. Pupils play the ‘big game’ of remembering quotes, writing insights about character theme, social context, all in a coherent structure, with written accuracy. Usually, this is undertaken without the practice and focus on specific knowledge and skills needed to do all of these things.

Dylan Wiliam describes this typically skilfully when describing baseball:

The coach has to design a series of activities that will move athletes from their current state to the goal state. Often coaches will take a complex activity, such as the double play in baseball, and break it down into a series of components, each of which needs to be practised until fluency is reached, and then the components are assembled together. Not only does the coach have a clear notion of quality (the well-executed double play), he also understands the anatomy of quality; he is able to see the high-quality performance as being composed of a series of elements that can be broken down into a developmental sequence for the athlete. 'Embedded Formative Assessment, p.122'

An alternative to summative past papers

So, what is the alternative to doing past papers? How do you avoid playing the ‘big game’ too early?

My teaching shift was to move to quizzing pupils on core elements of the text. A quiz on characters and themes would help to consolidate the base knowledge they need. A short answer test on key quotations would prove useful. Multiple choice questions to tease out their knowledge and understanding of the social and political context of the text would each help narrow the focus of assessment. Discussion and debate of key quotations or themes would offer me crucial diagnostic insights into pupils understanding (it just doesn’t feed the whole school data manager in the same way!).

After developing a coherent progression of diagnostic assessment, they’d be better prepared to tackle the Romeo and Juliet essay. The mock exam with more than one essay would be done at the latest possible opportunity. Given each of these more precise formative assessments offer more accurate diagnoses of gaps and issues, you are more prepared to aid their progress. Like my weekend football coaching, some novice players need more passing work, some positional play, others the basics of tackling an opponent.

Although it seems like a simplistic assessment, a cumulative quiz helps you to narrow the filed within the given ‘game’. It is the equivalent of a ‘rondo’ drill in football. This ultimately builds up a more reliable judgement to bear on what your pupils know and need to know and do in future. It still challenges many teacherly assumptions though.

I had been doubtful of the efficacy of multiple choice question for the study of English Literature. To me, they felt reductive and limited as a teaching tool. Now, a well-constructed multiple choice question appears to me to be concise but very effective. They are tricky to write (you need ‘plausible distractors’ and more), but they can save a lot of time and effort later as they can diagnose key misunderstandings and isolation important insights, while leading to rich discussion and debate.

For English Literature, improved assessments that delay the summative assessment of the big game could include a vocabulary test; quotation recall quizzes; literary term quizzes, and more. They seem inadequate, but they are diagnostic and secure the base knowledge pupils need to do the complex extended stuff later.

In the spring and summer, conversations can bemoan the lack of past papers for exams. There is a cottage industry of mock SATs, GCSEs and A levels. Rather, paradoxically, we should see this an opportunity to shift to (marking friendly) assessment practices that focus on diagnostic assessment over summative.

And so, back to football. On a bright Spring weekend, I want my boy to keep practicing great drills and skills in his training. Just playing mini matches would improve his skills. He may still career around the pitch like a balloon in a cyclone, but he will – in some longed-for future, do better in the big game!

For busy teachers, reducing the past papers marking burden – cutting out the endless mock exam marking frenzy – may free up more successful weekends too!

Related reading:

'4 Reasons to (Re)Focus on Formative Assessment’ – see HERE .The EEF guidance report on ‘Teacher Feedback to Improve Pupil Learning’ (featuring Dylan Wiliam) distils the evidence on feedback and formative assessment - see HERE .May 18, 2024

Focusing on Learning Failures and Problems

If you want to guarantee clicks on an article or to sell a new product, a focus on failure is the last thing you’d do. People want success. Ideally, they want success quick, cheap, and easy. And yet, when it comes to securing success in classrooms, I think it is imperative that we focus more on learning failures and problems.

If we only focus on solutions – be they curriculum planning, oracy, or ‘cold calling’ – a busy teacher won’t be prepared when they inevitably go awry in the classroom. If we better understand the problems we are looking to solve, and the likely failures that attend learning, then we offer teachers a richer understanding of teaching and learning.

The late Mary Kennedy was a brilliant education professor from Michigan State, in the USA. She wrote about teaching and learning with rare sensitivity and wisdom – founded on working with teachers – which every teacher could appreciate and relate to.

In a paper she wrote – entitled ‘Parsing the Practice of Teaching’ – she explored the challenges of supporting teacher development. Crucially, she captured how we focus on solutions and not problems, and how we obsess over success but can ignore the reality of likely failures:

“When we do research, we seek solutions to problems, and when we teach, we teach about the solutions we have discovered over time. Even if our solutions change over time, they are always taught with certainty. Thus, at one time we teach teachers about direct instruction, at another we teach them how to use cooperative groups, at another we teach lesson study, and at yet another we teach core practices. These are all plausible solutions to one or more problems of practice, but we often fail to discuss the problems themselves. Instead, we present these solutions as if these are the only possibilities available. But what novices need to learn is that none of these solutions can repeatedly satisfy all of the persistent challenges they will face.”

Mary Kennedy, ‘Parsing the Practice of Teaching’

Focus on failure and persistent problems

Mary Kennedy characterises five persistent problems faced by every teacher:

1. Portraying the curriculum. I.e. ordering, sequencing, and presenting the curriculum as a comprehensible whole or as a developing story.

2. Enlisting student participation. I.e. ensure pupils are cooperating and focusing on the learning at hand – including a willingness to do some hard thinking!

3. Exposing student thinking I.e. eliciting formative assessment of what pupils know and can do, with strategies such as questioning, or discussion.

4. Containing student behaviour. i.e. the glaring reality that is ensuring that every pupil is behaving and following instructions and enacting routines.

5. Accommodating personal needs i.e. balancing all these other problems with your personal teaching style and needs.

Many of these will chime neatly with busy teachers grappling with the realities of teaching twenty-eight teens, and similar.

There have been other ways of conceiving of this vital focus on solving problems and fixing failures. Tom Sherrington has characterised common teaching problems in his usual accessible, perceptive style with his ‘Teaching Problems and Solutions. The TPS Collection’.

He describes ten problems to solve:

1. Knowledge gaps.

2. Covering a class (substitute teacher).

3. Wide ability range!

4. How can parents help with learning and revision?

5. How do I adapt material for a wide ability range?

6. How do I engage passive learners?

7. How do I handle a misogynistic group of boys…?

8. How do I manage a congested curriculum?

9. How can I work most effectively with a teaching assistant in my lessons?

10. How do I manage a class when a bee enters the room?

There are clear parallels with Kennedy and Sherrington’s teaching and learning problems. One distinctive difference though is what Kennedy calls – 'grain size' – that is to say, how big or how wide ranging the problem. ‘Portraying the curriculum’ is massive, but ‘adapting material for a wide ability range’ and ‘managing a congested curriculum’ can fit underneath that wider problem. Usually we need both - understanding the big picture challenge and ready to enact the granular problems that arise daily.

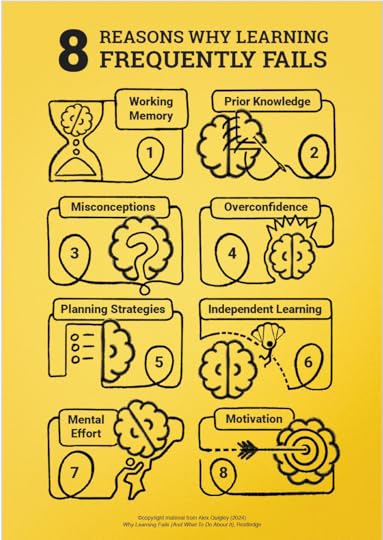

I wholly agree with Kennedy and Sherrington – we need to be more specific about the problems we are seeking to solve with our latest teaching and learning strategy solutions. In my latest book, ‘Why Learning Fails (And What To Do About It)’, I characterise eight common failures why learning frequently fails:

1. The narrow limits of working memory

2. Patchy prior knowledge

3. The nagging nature of misconceptions

4. A curious case of overconfidence

5. Faulty planning strategies

6. An inability to learn independently

7. Wandering attention and miserly mental effort

8. Falling motivation in the face of failure.

You can read my short explainers of these eight failures HERE.

[See the infographic below – and download a free PDF copy on my Resources page ]

The structure of my book is ‘problem > solution’ for all the aforementioned reasons. If our focus is curriculum design, we need to first address failures of our limited working memory, patchy prior knowledge and misconceptions. If the focus is ‘Cold calling’, then understanding the failures of wandering attention or overconfidence are essential to understand if we are to enact the strategy with adaptive expertise.

My hope is that teacher development, discussions, and debates become less led by the latest popular 'solution' (which can bubble into a fad), and instead become more focused on solving the problems that teachers really care about addressing.

With the ultimate aim of securing teaching and learning success, let’s focus more on our problems and pursue fixing our learning failures.

Order from Amazon now HERE

Order from Routledge now HERE.

May 12, 2024

Why Learning Fails - Free Resources

My new book - 'Why Learning Fails (And What To Do About It)' - has been published this week. It explores eight common problems that beset the classroom and beyond. To make sure this book is practical for every teacher, I have also developed a range of free resources.

The resources include:

8 Reasons Why Learning Fails (infographic). This simple resource visually captures the eight key issues that can see learning fail.Independent Learning Strategies. This checklist compiles some key research informed strategies to sustaining successful independent learning. Formative Assessment Strategies. This resource complies short lists of actionable formative assessment strategies for each of the eight potential learning failures. Successful Goal Setting. Goal setting can sometimes be viewed too simply. This resource shares the five key goal types that teachers should consider. Prioritisation activity. You cannot address every cause of learning failure all at once. We need to prioritise. This simple template supports just that.Simply sign up to my website and these resource (along with a range of others) are freely available.

May 11, 2024

Alex Quigley's Blog

- Alex Quigley's profile

- 12 followers