Alex Quigley's Blog, page 15

April 30, 2022

Leading Literacy… And Influencing Teachers

This short series is targeted at literacy leaders – either Literacy Coordinators, Reading Leads, or Curriculum Deputies – with a key role in leading literacy to ensure that pupils access the curriculum and succeed in meeting the academic demands of school.

Every school policy should be seen through the eyes of a recently qualified teacher on a full timetable, with a tricky class or classes.

When you begin with this assumption, it immediately makes you consider the difficulty level of embedding any shiny innovations, changed curricula, or new teaching techniques. Even a seemingly minor new teaching strategy must be integrated into a complex array of existing habits, classes, timetabling, and classroom peculiarities.

Then we consider literacy. Its scale and scope are near limitless: reading, writing, talk routines, spelling, grammar, editing, text choices, text choices, curriculum planning, and pupils’ literacy barriers etc. The list goes on.

With these challenges attending developing teaching techniques and teacher habits, it makes sense for literacy leaders to carefully about implementing a small number of meaningful but manageable literacy developments.

COM-B – A helpful model to consider teacher behaviour changeIt is helpful to try and distil down a likely literacy challenge/development, such as ‘improve the reading of informational texts and curriculum access’.

First, what specific teacher behaviours are we are looking to support? For instance, it may be we want teachers to appraise the difficulty level of all informational texts they’re using. In addition to that, it may be we are after teachers pre-teaching ‘keystone vocabulary’, or planning retrieval quizzes on the basis of selected tricky informational texts.

We then may consider what active pupil behaviours we are intending to support, so that pupils read informational texts more successfully. It may be that we teach them older pupils specific note-taking strategies, such as Cornell Note-making, to help them chunk down, navigate and record challenging informational texts.

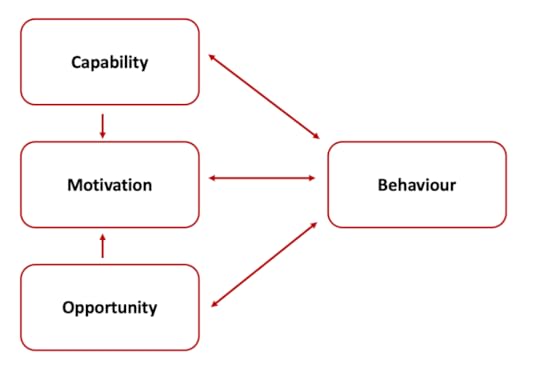

Once you have refined the specifics you can then use the COM-B model to reflect further on the behaviour change we are after. The COM-B behaviour model, is part of a ‘behaviour change wheel’ devised by Susan Michie and colleagues. At the heart of the approach is a useful consideration of the drivers of human behaviour – teachers or otherwise:

You can apply the model to the relevant literacy approach you are looking to support:

Capability: This describes both the physical and psychological capability to undertake a behaviour. For instance, do teachers have the energy and stamina, along with the deep knowledge and skills to replan lessons and focus in on changing the reading approach to tricky informational texts. When it comes to informational texts, there is likely a subject knowledge challenge to collate a range of apt texts and to be able to break them down and scaffold them appropriately.

Opportunity: This describes both the physical opportunities (time for SOL planning and physical resources – such as new textbooks) and social opportunities (do my department or phase team colleagues want to make similar changes and want to collaborate?). Perhaps the chief reality here is giving over the time to make a change and having a team of colleagues working with you. Without these supports, opportunities are always limited. Remember the busy RQT on a full timetable?

Motivation: This describes a reflective motivation (whereat teachers plan and reflect upon their work, thereby influencing our attitudes and behaviours), along with our automatic motivations (such as the habits that drive our daily practice). Of course, if you have both ‘capability’ and ‘opportunity’, then motivation is more likely. With informational texts, our curriculum planning may steer our teaching approaches, along with our habitual approaches to successfully scaffolding difficult texts in our subject or phase. In truth, teachers just may not recognise there is an issue, and so are just not motivated to change.

COM-B and Literacy PrioritiesUsing this model to reflect on any proposed literacy priorities can prove useful. For example, if there are challenges with regard to teacher knowledge or technique, then CPD is the solution. And yet, if motivation is low, or there is too little time or opportunity, then CPD is likely to prove necessary but insufficient.

You can try it quickly. You want to improve the teaching of the editing process for pupils’ writing at all key stages across a wide range of teachers and TAs? Well, what teacher problem is this solving (motivation)? How much subject knowledge and confidence do teachers have in explicitly teaching sentence variation or spelling patterns (capability)? Where in the school day are these approaches being embedded and how do teachers find the time to give meaningful feedback to pupils (opportunity)?

Now, consider the approach to behaviours that drive improved spelling, editing, and writing accuracy from a pupil perspective. Capability, opportunity and motivation still apply.

We may come to new reflections as literacy leaders. A CPD session, or even a sequence of training, is unlikely to prove a silver bullet.

Not only that – it may not be that teachers are resistant to adjusting their literacy practices at all – it may just prove that they are not wholly clear what specific behaviour changes are actually necessary in the classroom. For instance, teachers may understand an aim to read more extended texts, but they aren’t clear when or how best to enact extended reading within the limited scope of current curriculum time.

Let’s consider every literacy development, indeed all school improvement plans, through the lens of that harried, enthusiastic RQT facing a stacked timetable. COM-B could help to better support and steer successful change. If we are leading literacy, in whatever role, let’s ensure we seize every opportunity to influence and support teachers to make successful changes.

Read the series:

Part 1: ‘Leading Literacy… And Perennial Problems’

Part 2: Leading Literacy…And Influencing Teachers

Part 3: Leading Literacy…And Purposeful Professional Development

Part 4: Leading Literacy…And Communicating Complexity

Part 5: Leading Literact…And Evaluating Impact

April 24, 2022

Leading Literacy… And Perennial Problems

This short series is targeted at literacy leaders – either Literacy Coordinators, Reading Leads, or Curriculum Deputies etc. – with a key role in leading literacy to ensure that pupils access the curriculum and succeed in meeting the academic demands of school.

The old African proverb goes that it takes a village to raise a child. When it comes to the challenging task of developing skilled academic readers and writers, it also takes the proverbial village.

Literacy leaders take on various guises in these vital collective efforts of the ‘village’, from ‘literacy coordinators’, to ‘reading leads’, curriculum deputies, Trust leaders, and more. They are expected to understand a wealth of issues, engage their colleagues, implement change, and evaluate impact. Often, it is a task that is Sisyphean in scale.

Despite the shared understanding of the importance of literacy, these role face perennial problems and near-insurmountable challenges.

Five common barriers for literacy leaders

Too much to know and do in too little time. It is the omnipresent issue for school leaders – a lack of time to implement the careful, sustained change that is necessary for improved practice in the classroom. The research evidence that attends literacy can too often seem so vast as to appear unmanageable.

Too little focus. So, what is the literacy priority of the school: what about improving reading? Writing? Spelling? Grammar? Academic talk? Vocabulary? The list goes on and each problem and solution interact with one another. The well-meaning guidance to do ‘make fewer but more strategic choices’ is harder than it sounds when it comes to leading literacy.

Too little status. It is a common occurrence for literacy roles to be perceived as junior leadership opportunities. This notion is flawed as too little status can mean that school leaders lack the levers to enact change, they can lack the budget, and ultimately the authority necessary for the role. Teachers follow people, not policies, so the literacy lead needs meaningful authority and trust.

Too disconnected from other priorities and practices. Busy teachers are assailed by priorities. When it comes down to it, understandably, classroom management and curriculum ‘coverage’ can supersede complex and nuanced changes to how you teach academic writing or how to develop pupils who are struggling with spelling.

Too much reliance on a policy. You can enshrine a catalogue of purposeful approaches in a well organised literacy policy document, but then…well, school happens! Busy teachers can struggle to follow policies (or even read them!). For instance, what is a science teacher to make of supporting writing if they are relatively untrained? How confident is a year 5 teacher following the usual spelling policy when a dyslexic pupil is exhibiting complex individual needs?

So, what is the solution for beleaguered literacy leads? Well, there is no magic wand here. This is difficult work, in compromised conditions, requiring ample effort and probably some luck too.

Ultimately though, it is a task worth taking on. There is no school improvement priority that can out-do that of helping a child to learn to read and write, and to go on to read and write to learn. It may take the whole village, and brilliant literacy leads, but it is vital work worth doing.

Coming up…This short series offers literacy leads of all stripes and stages to explore some useful ideas and strategies. Here are the proposed topics for upcoming blogs in the series:

Leading Literacy…And Influencing TeachersLeading Literacy…And Purposeful Professional DevelopmentLeading Literacy…And Communicating ComplexityLeading Literact…And Evaluating Impact The post Leading Literacy… And Perennial Problems first appeared on The Confident Teacher.April 2, 2022

5 Micro-moves for Academic Talk

It is time to talk… about the importance of academic talk.

Since the beginning of the year, I have worked with lots of school leaders, with discussions quickly turning to the impact and experience of the pandemic, then onto reflections about future plans.

A regular refrain is the limiting experience of lockdown on academic talk. Despite the brilliant efforts to communicate and teach remotely, I hear the repeated examples from teachers frustrated by talking in the black void and of missing the countless opportunities for conversations, clarifications, and careful interactions in the classroom.

Of course, there is a time for authoritative teacher talk, there is a time for ‘golden silence’, and there is a time, and a need, for purposeful and well-structured academic talk.

What are the micro-moves of effective academic talk?

Though we can all recognise the value of academic talk as part of the fabric of teaching and learning, too often we can miscommunicate and misunderstand one another when it comes to talk. It can trigger assumptions and arguments with ease.

The varied terms we routinely use in education may not help the cause. Academic talk, speaking and listening, dialogic talk, oracy, turn-taking, and more… It is too easy to speak at crossed purposes and not develop a shared language or to properly codify the specific moves of effective academic talk.

Not only that, notions of academic talk or oracy can be misinterpreted as just the acts of making speeches or taking part in debates. We miss the opportunity to distil the precise micro-moves of academic talk that can be undertaken every day in every classroom. Experienced teachers can undertake these moves regularly, and seemingly naturally, but it pays off to make those moves explicit and to develop a shared language and understanding.

So, what are those micro moves that skilled teachers enact so effortlessly?

Revoicing. This micro move describes when the teacher repeats back a pupil response, verifying and often clarifying their insight. For instance, ‘So, you’re saying…’; ‘I think you are arguing…., is that right? Revoicing has the benefit of simple repetition. Pupils get the opportunity to hear an idea once more, distilled and made clear, offering the chance for greater understanding. It also offers a great opportunity to scaffold pupils’ language to use apt academic vocabulary. Read an excellent research article on revoicing HERE.

Restating peer reasoning. You can harness the power of repetition, and encourage pupils to listen more actively to one another, by habitually encouraging that pupils restate one another’s reasoning. For instance, ‘So, Jane thinks there are multiple causes that triggers the war… Adil, can you put Jane’s argument into your own words?’ A further move, to develop a rich dialogue is to clarify once more with Jane – thereby repeating, refining and extending the academic talk.

Expanding and recasting. A crucial teacher talk move is to expand upon a pupil response and carefully recast their utterance with apt academic vocabulary where necessary. For example, “Pupil: ‘He stretches the people like in his other paintings.’ Teacher: ‘Yes – the elongated bodies are a really crucial feature El Greco’s artistic style.’” We can be explicit about this sophisticated academic code switching, encouraging pupils to do it (sensitively) with one another too.

‘Simple <> Sophisticated’. You can model and scaffold the selection of apt academic vocabulary in every utterance in the classroom. With the modelling strategy, ‘Simple >< Sophisticated’, teachers can quickly and repeatedly model apt word choices. For instance, if a pupil uses the word ‘sweat’, then the teacher may model the use of ‘perspire’. We can use such pairings repeatedly and discuss the choice and whether it does the job. Should pupil’s use ‘chop off’ in history, should we substitute it with ‘decapitate’? Sometimes simple will be best, but the sophisticated word choice is often necessary.

Wait time. Captured in the seminal 1972 research by Mary Budd Rowe, ‘wait time’ is that subtle but often overlooked habit of ensuring pupils have more time to think before they are expected to engage in academic talk. The impact from giving pupils nine-tenths of a second as compared to three to five seconds was marked decades ago, and we can assume it is no different this side of the pandemic. Longer wait time can encourage more extended pupil responses (assuming pupils have enough background knowledge to draw upon).

We can easily assume that these subtle talk moves are all part of our repertoire. But so much research on classroom talk shows that developed academic talk is too often truncated – often unintentionally and tacitly. The delicate development of these micro-moves may be trickier and more subtle than is typically conceived, so we should pay them close attention.

It may well be the right time to talk with colleagues about the restating and refining the routines of academic talk.

Related reading: The brilliant Mary Myatt makes a compelling case for ‘Walking the Talk’ – HERE . Professor Lauren Resnick and colleagues have summarised what they term as ‘Accountable talk’ which is a useful overview for all facets of effective academic talk – HERE .Tom Sherrington explains in a 5 minutes of utter clarity from his kitchen (‘Kitchen Pedagogy’) his questioning routines: https://youtu.be/LAqde38TwE0. The post 5 Micro-moves for Academic Talk first appeared on The Confident Teacher.6 Micro-moves for Academic Talk

It is time to talk… about the importance of academic talk.

Since the beginning of the year, I have worked with lots of school leaders, with discussions quickly turning to the impact and experience of the pandemic, then onto reflections about future plans.

A regular refrain is the limiting experience of lockdown on academic talk. Despite the brilliant efforts to communicate and teach remotely, I hear the repeated examples from teachers frustrated by talking in the black void and of missing the countless opportunities for conversations, clarifications, and careful interactions in the classroom.

Of course, there is a time for authoritative teacher talk, there is a time for ‘golden silence’, and there is a time, and a need, for purposeful and well-structured academic talk.

What are the micro-moves of effective academic talk?

Though we can all recognise the value of academic talk as part of the fabric of teaching and learning, too often we can miscommunicate and misunderstand one another when it comes to talk. It can trigger assumptions and arguments with ease.

The varied terms we routinely use in education may not help the cause. Academic talk, speaking and listening, dialogic talk, oracy, turn-taking, and more… It is too easy to speak at crossed purposes and not develop a shared language or to properly codify the specific moves of effective academic talk.

Not only that, notions of academic talk or oracy can be misinterpreted as just the acts of making speeches or taking part in debates. We miss the opportunity to distil the precise micro-moves of academic talk that can be undertaken every day in every classroom. Experienced teachers can undertake these moves regularly, and seemingly naturally, but it pays off to make those moves explicit and to develop a shared language and understanding.

So, what are those micro moves that skilled teachers enact so effortlessly?

Revoicing. This micro move describes when the teacher repeats back a pupil response, verifying and often clarifying their insight. For instance, ‘So, you’re saying…’; ‘I think you are arguing…., is that right? Revoicing has the benefit of simple repetition. Pupils get the opportunity to hear an idea once more, distilled and made clear, offering the chance for greater understanding. It also offers a great opportunity to scaffold pupils’ language to use apt academic vocabulary. Read an excellent research article on revoicing HERE.

Restating peer reasoning. You can harness the power of repetition, and encourage pupils to listen more actively to one another, by habitually encouraging that pupils restate one another’s reasoning. For instance, ‘So, Jane thinks there are multiple causes that triggers the war… Adil, can you put Jane’s argument into your own words?’ A further move, to develop a rich dialogue is to clarify once more with Jane – thereby repeating, refining and extending the academic talk.

Expanding and recasting. A crucial teacher talk move is to expand upon a pupil response and carefully recast their utterance with apt academic vocabulary where necessary. For example, “Pupil: ‘He stretches the people like in his other paintings.’ Teacher: ‘Yes – the elongated bodies are a really crucial feature El Greco’s artistic style.’” We can be explicit about this sophisticated academic code switching, encouraging pupils to do it (sensitively) with one another too.

‘Simple <> Sophisticated’. You can model and scaffold the selection of apt academic vocabulary in every utterance in the classroom. With the modelling strategy, ‘Simple >< Sophisticated’, teachers can quickly and repeatedly model apt word choices. For instance, if a pupil uses the word ‘sweat’, then the teacher may model the use of ‘perspire’. We can use such pairings repeatedly and discuss the choice and whether it does the job. Should pupil’s use ‘chop off’ in history, should we substitute it with ‘decapitate’? Sometimes simple will be best, but the sophisticated word choice is often necessary.

Wait time. Captured in the seminal 1972 research by Mary Budd Rowe, ‘wait time’ is that subtle but often overlooked habit of ensuring pupils have more time to think before they are expected to engage in academic talk. The impact from giving pupils nine-tenths of a second as compared to three to five seconds was marked decades ago, and we can assume it is no different this side of the pandemic. Longer wait time can encourage more extended pupil responses (assuming pupils have enough background knowledge to draw upon).

We can easily assume that these subtle talk moves are all part of our repertoire. But so much research on classroom talk shows that developed academic talk is too often truncated – often unintentionally and tacitly. The delicate development of these micro-moves may be trickier and more subtle than is typically conceived, so we should pay them close attention.

It may well be the right time to talk with colleagues about the restating and refining the routines of academic talk.

Related reading: The brilliant Mary Myatt makes a compelling case for ‘Walking the Talk’ – HERE . Professor Lauren Resnick and colleagues have summarised what they term as ‘Accountable talk’ which is a useful overview for all facets of effective academic talk – HERE .Tom Sherrington explains in a 5 minutes of utter clarity from his kitchen (‘Kitchen Pedagogy’) his questioning routines: https://youtu.be/LAqde38TwE0. The post 6 Micro-moves for Academic Talk first appeared on The Confident Teacher.March 20, 2022

Simple Questions to Support Change

Making positive changes in schools is incredibly hard work. It typically involves lots of teachers who are naturally inclined to protect their hard-won habits. As such, it is crucial to draw upon their experience and expertise, whilst recognising their beliefs, challenges, and sensitively handling their natural hesitations.

By asking simple questions about the acceptability, the appropriateness, and the feasibility of a proposed change, or new approach, it is probable that we increase the likelihood of its success. Happily, accessible questions have been developed by researchers seeking out insights into whether a change is likely to be implemented with success.

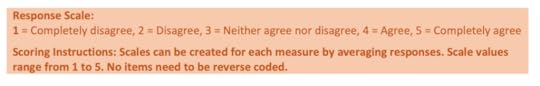

Take a look at following three measures (they can be used together or separately):

Acceptability of Intervention Measure (AIM)

1) [The proposed change] meets my approval.

2) [The proposed change] is appealing to me.

3) I like [The proposed change].

4) I welcome [The proposed change].

Intervention Appropriateness Measure (IAM)

1) [The proposed change] seems fitting.

2) [The proposed change] seems suitable.

3) [The proposed change] seems applicable.

4) [The proposed change] seems like a good match.

Feasibility of Intervention Measure (FIM)

1) [The proposed change] seems implementable.

2) [The proposed change] seems possible.

3) [The proposed change] seems doable.

4) [The proposed change] seems easy to use.

These three quick and simple questionnaires can be shared easily. Their language is accessible and they can be used to stimulate useful discussion, or the information can offer a prompt to adapt a proposed approach.

It is an all-too-human trait to be confident in making a successful change. Such optimism helps us get out of bed in the morning. And yet, we should probably temper it with a dose of pragmatism. These questions can help draw out that pragmatism and offer us rich information to intelligently adapt our efforts.

Related reading: Why disrupting education doesn’t work – Innovation is hard and ‘disrupting education’ is threatening to teachers. What do teachers really care about? – Teachers wan’t calmness and control – policy proposals need to be responsive to the needs of teachers. The post Simple Questions to Support Change first appeared on The Confident Teacher.February 19, 2022

Why ‘disrupting education’ doesn’t work

There are trillions of choices teachers make when they teach. This dizzying complexity makes teaching rewarding, tiring, stressful, and sometimes even thrilling.

Understandably, faced with the complexity of the classroom, teachers are necessarily creative, but they also seek out stability and tranquillity. For many teachers, hearing calls for ‘disrupting education’, or the mention of radical reform sounds disconcerting and threatening.

It is often the case that the reimagining of education emerges from outside the classroom. Well-meaning thinkers see rapid technological changes happening, or children immersed in the latest game, and they imagine their easy and attractive implementation in the classroom.

When you actually take the time to explore inside the classroom, and speak to teachers, the barriers to bold new ideas become clearer. In her brilliant book, ‘Inside Teaching’, Mary Kennedy (a US educationalist), she lifts the lid on real (US) teachers and their perceptions and feelings. She revealed teachers pursuing the avoidance of distractions, their aims for tranquillity, and even the dampening of pupil engagement when is threatens the necessary calmness of the classroom.

There is an enduring meme of dull, dry teaching that is pervasive in our culture. But is it fair?

Rather than some caricature of soulless, dull, or even controlling teachers, Kennedy presents a more subtle notion of small ‘c’ conservative attitudes to teaching:

“These intentions are quite different from the authoritarian motives that critics often attribute to teachers’ routines. Teachers clearly view routines as important contributors to emotional and social tranquillity.”

Page 92, Inside Teaching

Shiny, new approaches that break beyond typical classroom structures and routines are often disruptive in real terms – at least at first – and so teachers naturally resist this risk to their hard-earned routines.

Why shift seldom happensEvery few years, ambitious policy makers the world over enact significant curriculum shifts (‘Shift happens’, anyone?). We have seen the fuzzy notion of ‘21st Century Skills’ come and go. Classrooms get redesigned and new roles are assigned. New technology often proves a favourite motivator, and method, to transform the classroom from its traditional ‘teacher at the front’ focus.

And yet, teachers are brilliant at quiet, closed-door resistance. In a recent study by Darren Hannah, Claire Sinnema & Viviane Robinson (2021), entitled ‘Understanding curricula as theories of action’, they characterise curriculum reform in Japan and the staunch rejection of new curricula designed to disrupt more traditional approaches.

In 1999, policy makers initiated the ‘Yutori’ reforms – which aimed to usher in a ‘Relaxed education’ or ‘Zest for Life’ reforms. Traditional subjects were cut and approaches like ‘Integrated Studies’ were added to the curriculum. Teachers assimilated some of the practices into their existing habits, but Junior School teachers simply refused to enact the majority of these progressive new curriculum plans, given they clashed with their beliefs and hard-won annual gains.

In Japan, the glossy new curriculum was quietly shelved. The real ‘change makers’ closed their classroom doors and carried on teaching.

Vivianne Robinson has helpfully characterised why so many ‘disruptive’ changes fail. In her aptly named book, ‘Reduce Change to Increase Improvement’, she describes teachers’ ‘theory of action’: that is to say, their ingrained beliefs and practices that drive their behaviour and choices in the classroom. Too often, new teaching policy ideas bypass teachers’ real priorities. By not talking with teachers, they fail to understand the real barriers to new practices and change, along with the hard-won habits of teachers.

Her answer – and one I would share – is that we need to talk to teachers and better understand their beliefs and needs. I suspect they’ll seldom include a desire to radically disrupt their routines. This small ‘c’ conservative attitude is no Luddite rejection of new ideas; it is most typically founded on a care for their pupils and the privileging of calm stability in the crucible of the classroom.

Let’s then make a call for careful, gradual change that is shared with teachers and is sensitive to the complexities and stresses of the classroom. It won’t prove as catchy as ‘Shift Happens’. It is unlikely to generate a stack of slick YouTube videos. But it just might work.

The post Why ‘disrupting education’ doesn’t work first appeared on The Confident Teacher.February 12, 2022

Who should read aloud in class?

There are fewer more important acts in all of education than reading in the classroom. From what is read, to the specifics of when, why, and by whom, the how of reading in the classroom can prove a vital daily decision.

Given reading aloud in class is part of the fabric of teaching and learning, there is inevitably a legion of daily practices that attend the act of reading in the classroom. And so, we must ask, are we clear what reading practices we should do more of and what practices we should adapt or stop?

There is evidence to suggest that we should stop, or at the very least carefully adapt, the common act of ‘Popcorn reading’ or ‘round-robin reading’ (RRR). ‘Popcorn reading’, or RRR, describes the all-too-common act of selecting pupils at random to read aloud one after another. RRR sometimes makes for a more selected approach to the same practice. For instance, every pupil on the register reads that week etc. – but no significant practice or rehearsal is involved.

Invariably, reading without careful preparation and practice for novice pupils is prone to go awry. This is especially likely with demanding curriculum texts.

I used the RRR approach for years, just like I was taught, unthinkingly. I simply didn’t know there was useful evidence to substitute it for better strategies that focus on fluency.

Put away the ‘Popcorn reading’Part of the problem with Popcorn reading and RRR is the emotions that can often attend these approaches. For some pupils, it causes stress and takes up their mental bandwidth. They aren’t actually thinking about what they are reading – they are waiting to be asked to read. For some pupils, they are patently dysfluent, so they get embarrassed, which obviously impacts their confidence (including the impact on their sense of self-efficacy as a reader).

An interesting small study from Spain compared the teacher reading aloud, silent reading, and ‘follower reading’. ‘Follower reading’ described the act of listening along to your peers. The study showed what many teachers would suspect: trying to follow and listening to a peer who is not a fluent reader can hamper your comprehension.

Compared to the expert model of a teacher, listening to slow-going peers, picked without any preparation for reading a given passage, can prove an issue. Hearing and practising fluent reading matters, for pupils young and old. And so, teacher-led reading – with confident, clear expression, that offers important cues to support understanding – should trump the ad hoc selection of pupils’ reading.

Pupils reading aloud in class is typically slower than a fluent, expert teacher. As such, pupils can get in the bad habit of following their peers along and even baking errors into their mental model of the text. For instance, in ‘Goodbye Round Robin’, Professor Tim Rasinski and Michael Opitz suggest that when pupils listen to their dysfluent peers they quietly read along (this is labelled ‘sub-vocalisation’) and thereby unhelpfully imitate slow, dysfluent reading. They can pick up bad habits and not grasp the text.

Another gain when teachers model expert reading of complex texts is that it allows for the increasingly demanding texts pupils need to progress through the academic curriculum.

Additionally, teachers knowing and reading a text with fluency and precision can be undertaken with timely strategies, such as ‘interactive reading aloud’ (IRA). That is to say, teachers don’t just read aloud – but they make timely comprehension prompts, such as clarifying an important word, or stopping and questioning at the key point in a given text.

What should replace ‘popcorn reading’/RRR?The teacher reading aloud and expertly modelling fluency (pace, expression, volume etc.) is likely a better bet than selecting underpractised pupils to read.

It is important to state that pupils do need to practise reading aloud if they are to develop and improve their own reading fluency. What evidence-informed strategies can help this aim?

Professor Diane Lapp, from San Diego State University, in the categorically titled, ‘If you want students to read widely and well – Eliminate ‘Round-robin reading’, suggests the following approaches:

Repeated reading, which involves repeating a reading modelled first by the teacher or another proficient reader.Choral reading, which means reading together with others who are proficient readers.Echo reading, or the student echoing or repeating what the proficient reader has just read.Readers’ Theatre involves a dramatic reading of a text or script by the students.Neurological impress, which involves the student and teacher reading together while tracking words.Let’s put away the popcorn, retract RRR, and put efforts into teacher-led reading and a purposeful focus on fluency-building practices.

Related reading: Read and download my free tool comparing ‘Whole Class Reading Approaches’ – HERE .Read the EEF ‘Improving Literacy at Key Stage 2’ guidance report and the focus on fluency, ‘Reader’s Theatre’, and more – HERE .Professor Tim Shanahan explores a useful critique of RRR in ‘Round robin by any other name – Oral reading for older readers’ – .Of course, you could always explore ‘Closing the Reading Gap‘ to find out much more!

[Image via Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/115089924@N02/12212474014] The post Who should read aloud in class? first appeared on The Confident Teacher.February 5, 2022

Marking is murder!

Every so often the issue of marking and feedback emerges and fractious debates kick off. Teachers with marking ingrained as a daily habit, can view it as essential; whereas, many teachers see it as extraneous to their core work and simply not worth the time and effort.

So, if marking is murder, is it worth the effort? And is ‘marking or verbal feedback’ even the right question to be asking about feedback anyway?

Last year, the EEF published a guidance report on ‘Teacher feedback to improve pupil learning’. A key tenet of the guidance was that there is a perennial see-saw of methods:

“One can see this as a ‘feedback methods see-saw’ that has tipped back and forth between an emphasis on extensive written feedback and a focus on more verbal methods of feedback, which may take less time.”

Teacher Feedback to Improve Pupil Learning, Page 4

In the last week, I have read that written marking is an act of care for pupils and pretty much irreplaceable as a medium for responding to pupils’ writing. Conversely, many teachers have responded by restating the significant workload that can attend marking (the EEF guidance cites that KS3 teachers were spending over 6 hours a week on marking) and questioning its impact.

Like the see-saw in the aforementioned analogy, the arguments over written feedback invariably don’t get us very far.

What does recent evidence reveal?The best available evidence on feedback cited in the guidance report is inconclusive when it comes to the question of ‘marking or verbal feedback?’ Indeed, it is more accurate to state that both written marking and oral feedback can be effective… if they follow key principles. It is less conclusive, nor does it make for good online arguments, but it is a more accurate state of affairs.

The research evidence indicates some helpful steers. It might even avoid some stale arguments. It doesn’t matter so much about the colour of the pen for written feedback (perhaps the red pen needn’t be dead), nor does whether teachers use grades or not make a conclusive difference either. It doesn’t appear to matter to learning how frequent feedback proves.

It is inconclusive whether pupils think their teachers care more because they mark their writing. Personally, I think good teachers show they care in a hundred meaningful ways that means you needn’t mark for the sake of it.

Indeed, in an interesting study involving year 7 pupils in Wales, those pupils who received ‘enhancing formative feedback comments’ didn’t make any obvious gains over those pupils who didn’t receive such comments. When comments like “very good” were used, pupils didn’t beam with uncontained pride, they were simply “poorly understood by the students and did little to enhance the learning process”. Perhaps ‘tick and flick’ and a nice comment daubed here and there is less welcome than we think?

What about “a good murder”?Professor Valerie Shute offers a helpful analogy for teachers considering how regularly they should mark, or whether oral feedback can be impactful: effective formative feedback is like a ‘good murder’. She states:

“Formative feedback might be likened to “a good murder” in that effective and useful feedback depends on three things: (a) motive (the student needs it), (b) opportunity (the student receives it in time to use it), and (c) means (the student is able and willing to use it).”

Valerie Shute (2008 )

The murder analogy offers a helpful lens on maintenance marking, or ‘tick and flick’. Does the pupil really need it (motive)? Wil they be provided time to respond to it (opportunity)? Will they use it (means)?

A common alternative to written marking is whole-class feedback. Once more, using Shute’s ‘murder’ model is helpful. If you are giving whole-class feedback, do pupils think they need it, or do they think it is even feedback for them or their peers (motive)? Is the whole class feedback session structured with enough time and support so that they use the feedback meaningfully (opportunity)? Did they understand our feedback, and do they know what to do next with your whole class summary (means)?

For too long, teachers have been forced to endure the see-saw of feedback methods based on not much more than routine compliance, the need to please parents, or simply to retain long-held rituals.

If marking is murder…and plain hard work to get right…we should think much more about these long-standing routines. We should think about the seeming-heroics of marking every book, as much as we should consider the likely effectiveness of ‘tick and flick’, writing “great work!”, and similar.

[Image from Roger Evans: https://www.flickr.com/photos/2868197... post Marking is murder! first appeared on The Confident Teacher.January 29, 2022

10 things to know about teaching and learning

There is lots to know about the brilliantly complex act of teaching and learning. Here is my list of 10 things to know in the plainest terms possible:

Find out much more here…

1. Pupils knowing stuff helps them to learn more stuff (background knowledge).

2. It is effective and efficient to explicitly teach pupils the stuff (explicit instruction).

3. Pupils cannot learn lots of new stuff at any one time (working memory limitations).

4. We need to teach with pupils’ limited working memory in mind (cognitive load theory).

5. We need to make helpful connections between the complex stuff (schema building).

6. Plan to revisit the stuff with careful timing to secure remembering (spacing and retrieval).

7. Reading strategically is also vital to understanding complex stuff (reading comprehension strategies).

8. Pupils need to build confidence in their ability to learn and know stuff (self-efficacy).

9. Pupils need to exercise their attention and control their emotions to learn stuff (self-regulation).

10. Pupils need to pick the right strategies to learn the stuff successfully (metacognition).

If you want to dig a little deeper, the following reading list should offer a wealth of handy, freely-accessible online resources:

To find out more about the important role of background knowledge read:Dan Willingham’s AFT article on ‘How Knowledge helps’.

Reading Rockets article on ‘Building Background Knowledge’.

Lapp, Frey & Fisher article on ‘Building and Activating Students’ Background Knowledge’.

2. To find out more on the value of explicit instruction read:

Rosenshine’s AFT article on his ‘Principles of Instruction’.

Archer & Hughes chapter extract on ‘Explicit Instruction: Effective & Efficient Teaching’.

Anita Archer ERRR Podcast on ‘Explicit Instruction’.

3. To find out more on the importance of working memory read:

Gathercole & Alloway’s booklet on ‘Understanding Working Memory’.

Marc Smith on ‘Chunking to Improve your Memory’.

Watch Dr Joni Holmes YouTube presentation on ‘Working Memory and Classroom Learning’.

4. To find out more about teaching with cognitive load theory in mind read:

NSW Government report on ‘Cognitive Load Theory: Research that Teachers Really Need to Understand’.

Blake Harvard article on ‘Cognitive Load Theory & Applications in the Classroom’.

Oliver Lovell podcast on ‘Cognitive Load Theory in Action’.

5. To find out more about schema building read:

Jeff Pankin has outlined the long history of schema theory.

My article on ‘Schema Building and Academic Vocabulary.

Tom Sherrington on ‘Schema Building: A Blend of Experiences…’.

6. To find out more about spacing and retrieval read:

The EEF review of cognitive science in the classroom offers a helpful explainer.

Retrievalpractice.org has produced a guide to using spaced retrieval.

Learning Scientists podcast on ‘How Students Can Use Spacing & Retrieval Practice’.

7. To find out more about the role of reading comprehension strategies read:

Professor Tim Shanahan on ‘Comprehension Skills or Strategies?’

Caroline Bilton on ‘Getting to Grips with Reading Comprehension Strategies’.

Chloe Woodhouse YouTube explainer of ‘Reciprocal Reading’ in her school.

8. To find out more about the value of self-efficacy read:

Dylan Wiliam explaining self-efficacy.

The Education Hub on ‘6 Strategies for Promoting Students’ Self-efficacy in Your Teaching’.

My blog on ‘The Power of Teacher Expectations’.

9. To find out more about self-regulation read:

Robert Bjork and Nate Kornell on ‘Self-regulated Learning: Beliefs, Techniques and Illusions’.

East London Research School YouTube series on ‘Self-regulation in the Early Years’.

Harry Fletcher-Wood on ‘Why Self-regulation is the Wrong Goal’.

10. To find out more about the importance of metacognition read:

Education Endowment Foundation guidance report on ‘Metacognition & Self-regulation’.

John Dunlosky on ‘Strengthening the Student Toolbox: Study Strategies to Boost Learning’.

Sadie Thompson explaining metacognition in her school and MFL classroom.

I am certain there are debates to be had, glaring omissions, and more, but these 10 things are a start!

The post 10 things to know about teaching and learning first appeared on The Confident Teacher.January 22, 2022

Commonly Confused Academic Vocabulary

It is vital for our pupils to possess a wealth of academic vocabulary if they are to succeed in school.

For most of my teaching career, this issue was tacit and flew beneath my radar. Vocabulary issues were often hidden in plain sight. In the last few years, however, developing academic vocabulary has become talked about much more (given countless teachers have related the issues of their pupils).

It is now broadly accepted that breadth and depth of vocabulary knowledge is needed to make the academic language of school better understood. It is a complex combination of knowing lots of words, along with their many layers of meaning, as well as how words relate to one another, such as their families, roots, and more.

Given most academic words are complex and polysemous (that is to say, they have more than one meaning) just sharing word lists with pupil-friendly definitions is typically inadequate. ‘Thesaurus syndrome’ can ensue, as pupils fill their writing with seemingly-superior synonyms, but end up with confused sentences.

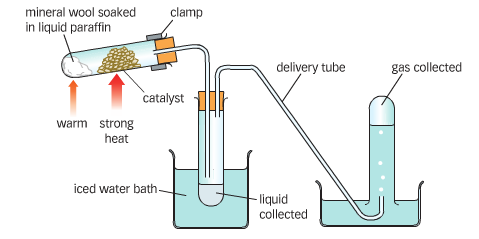

Limited word knowledge is exposed in the classroom when polysemous vocabulary confuses familiar everyday meanings with specialist academic word meanings. One such example is ‘cracking‘ in science. I use ‘cracking’ in my everyday speech: ‘it was a cracking match’ or ‘what a cracking dinner’. However, if you are studying GCSE chemistry, you need to know that ‘cracking’ is a term for breaking large hydrocarbon molecules into simpler molecules.

The process of ‘cracking’ in science

The process of ‘cracking’ in scienceThe mere familiarity of many polysemous words means that misconceptions can develop easily in the minds of pupils. They can self-report confidence in their vocabulary knowledge, but on closer inspection it proves misplaced. Not only that, it is hard to select the right meaning when pupils are searching through a dictionary for answers.

We should consider: what words in each subject discipline are most prone to such misunderstanding?

Here are 10 examples of commonly confused academic vocabulary:

Factor. In maths, factor means a number or algebraic expression that divides another number or expression easily (with no remainder) e.g. 2 & 4 are factors of 8. In history, factor is most likely linked to causal arguments. In our wider culture, an X-factor still holds sway. Interception. In geography, interception describes precipitation that does not reach the soil (it is intercepted by leaves etc.). Whereas in PE, and in our wider culture, we commonly associated an interception with a pass being seized by the opposition.Force. In science, force has a precise meaning to describe the push or pull of an object that causes it to change velocity. In history, force may commonly describe an army battalion or similar. Whereas, in our wider culture, you may quickly get mixed in Star Wars!Bleeding. In art and textiles, bleeding is a specialist technique describing the loss of dye from a coloured textile in contact with a liquid. Everywhere else bleeding stems from a wound and similar. Moment. In physics, a moment describes the turning effect of a force. Everywhere else, it is to do with a moment in time and nothing to do with gears and levers.Culture. In biology, it describes the propagation of microorganisms. In sociology, and in our wider culture, it describes the language, beliefs, values, and more, held by members of a social group.Attrition. In geography, this describes the erosion process – whereat rocks gradually wear away at one another. In history, and more commonly, attrition is a broader reduction in strength, such as a loss of staff in schools, or the saying ‘war of attrition’.Abstract. In art and design, abstract is quite specific in describing art the intentionally does not attempt to represent external reality. In describes a branch of algebra in maths, but most commonly, it describes something that exists as an idea and not a concrete reality. Tone. In art and design, tone describes the relative lightness or darkness of a colour. In English or drama, it means the general character of writing, or the quality of a voice – its pitch and quality. Depression. In geography, depression has a specific meaning a sunken landform or subsidence, such as a river valley. In history, we may leap first to the Great Depression. In everyday life, depression more broadly describes feelings of dejection (often clinical).To avoid confusion and potential misconceptions, being explicit about the specialist language of our subjects is essential (it is the stuff of ‘disciplinary literacy’). The differences can prove subtle. Explicit vocabulary instruction can of course help, as well as simply tackling word meanings, and layers of meaning, head on in explanations and discussion.

Akin to studying the earth in geography (or chemistry), we should pay attention to layers of meaning, digging into words, making rich connections, and thereby discovering their rich histories, parts and meanings.

The post Commonly Confused Academic Vocabulary first appeared on The Confident Teacher.Alex Quigley's Blog

- Alex Quigley's profile

- 12 followers