Alex Quigley's Blog, page 13

February 4, 2023

Adaptive Teaching and Vocabulary Instruction

Teaching can be tremendously rewarding, but we also know the classroom can be crammed full of complexity, surprises, and problems to solve.

‘Adapting teaching’ is a recently popular – though long-standing – phrase. It captures the subtle and challenging art of teaching expertly so that pupils maximise their learning. The immense skill of effective teaching has often been described as ‘adaptive expertise’. It best describes a balance of hard-won, efficient teaching habits, along with moment-to-moment responsiveness.

We all know those situations whereby you teach a well-trodden topic, but students understand (and misunderstand) it is new ways each time. It could be the science teacher noting the experiment doesn’t generate the expected results and having to quickly translate this tricky issue and fend off any new misconceptions.

Perhaps it is the English teacher reading a set of essays on Macbeth and power that is sorely lacking meaningful analysis of the problematic representation of women. That is despite what seemed like hours of teaching… the problematic representation of women in Macbeth! Time to replan that next lesson…

It can be small misunderstandings, long-standing misconceptions, innovative new ideas, or brilliant insights from students that demands the responsiveness of ‘adaptive teaching’.

What exactly is ‘adaptive teaching’?Lyn Corno, in ‘On Teaching Adaptively’ helpfully distinguishes ‘adaptive teaching’ and describes different types of adaptations. She describes ‘macro-adaptations’ as changes to the curriculum or grouping students differently. Then there are ‘micro-adaptations’ that form the bread of butter of teachers tweaking their plans and responding sensitively to their students.

It is the ‘micro adaptations’ which I think are key to the expert teacher and their ability to be responsive to learning. Corno neatly describes them thus:

“Practicing teachers… make micro-adaptations all the time—in the ongoing course of instruction and in response to particular students. They interpret the to and fro of class- room life, and intercede. In fact, with respect to classroom teaching, the term micro-adaptation might be defined as continually assessing and learning as one teaches—thought and action intertwined.”

Lyn Corno, ‘On Teaching Adaptively’

Adaptive teaching appears to have supplanted differentiation in the plans and minds of teachers in England. In truth, differentiation has been stained with the bad name of ‘all – most – some’ lesson objectives, along with a legion of different worksheets organised in laborious fashion. Alas, too many teachers have seen their differentiation for struggle students fail and it add to their workload too.

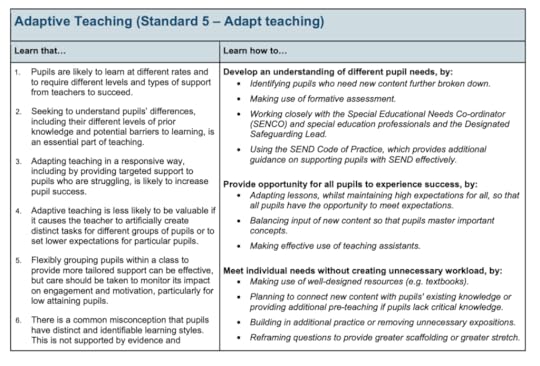

Adaptive teaching – recently enshrined in the Early Career Framework (ECF) – meanwhile, appears to better capture the nimble and necessary responses that are sensitive to a host of different responses the students generate as they grapple to understand the curriculum and develop their skills.

Adaptive teaching via vocabulary instruction

The ECF helpfully describes the common-place teaching method of ‘identifying pupils who need new content further broken down’, along with ‘planning to connect new content with pupils’ existing knowledge or providing additional pre-teaching if pupils lack critical knowledge’.

Most teachers will consider these adaptive teaching approaches to be well-served by vocabulary instruction. For example, a useful way to ‘identify students who need new content further broken down’ is to activate their prior knowledge of vocabulary. Academic vocabulary is often that unit of ‘broken down’ knowledge that proves accessible.

In English, you could be teaching a new unit of Gothic literature. Naturally, you would want to know what prior knowledge students already possess. We may also assume some cultural touchstones that could prove reference points (Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster etc.]. We might active their prior knowledge with a ‘Collage collection’ of gothic images, before asking students to generate words, phrases, and ideas they know well.

The subsequent discussion may offer up notions of Gothic monsters that need further breaking down. Most likely, we’d need to add in some additional teaching for some students who have far less experience of reading gothic texts than their peers.

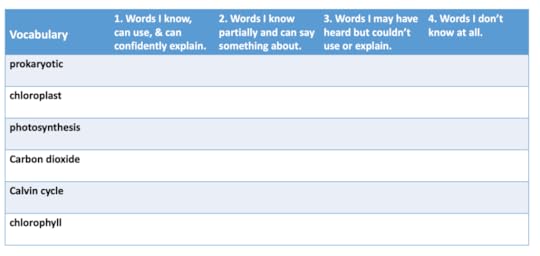

Alternatively, if we were teaching photosynthesis in science, we may begin the topic using a ‘Vocabulary diagnostic assessment’, like Dale’s word knowledge assessment:

This simple self-report vocabulary assessment can help with a familiar topic like photosynthesis to diagnose what students have remembered from previous teaching (of course, mere familiarity with vocabulary does not mean they understand this complex process, but it opens up the opportunity to diagnose what students do understand). It can result in a micro-adaptation where the terms ‘chlorophyll’ and ‘chloroplast’ are quickly retaught to a some students who need it and not others.

Vocabulary instruction lends itself neatly to ‘micro-adaptations’ because they form handy distillations of worldly knowledge that can be questioned, discussed, debated, defined, explained, and tested. They offer one route of valuable academic support so that pupils can access the curriculum, whilst being manageable units from which teachers can intelligently adapt their teaching.

Related Reading: Jon Eaton, from Kingsbridge Research School, has written an excellent EEF guest blog on ‘Moving from ‘Differentiation’ to ‘Adaptive Teaching’ HERE – with a brilliant free explainer on ‘Understanding Adaptive Teaching‘ resource HERE . Kirsten Mould has written an excellent EEF ‘adaptive teaching’ explainer blog entitled, ‘Assess, Adjust, Adapt: What does adaptive teaching mean to you‘ – HERE . For more vocabulary teaching strategies, my framework of ‘Three Pillars of Vocabulary Teaching‘ offers helpful strategies – HERE . The post Adaptive Teaching and Vocabulary Instruction first appeared on The Confident Teacher.January 28, 2023

5 Free Research Reads On… The Primary to Secondary School Transition

The primary to secondary transition is a topic of annual angst. For school leaders, teachers, and parents, gaining insight to supporting pupils making the leap to ‘big school’ is a crucial topic.

Much of the research on transition doesn’t offer easy packaged-up approaches. It does pose areas of promise (curriculum continuity when it comes to vocabulary; small interventions to increase belonging etc.) that could be implemented alongside the usual fostering of new friends and comfort in the new (often scary) environment. Every parent and school teacher wants a strong start in secondary school – it can matter a great deal and the impact endures – so allocating effort in this area could prove a best bet.

The following five sources are freely available and help school leaders and teachers to tackle the topic of transition with greater confidence:

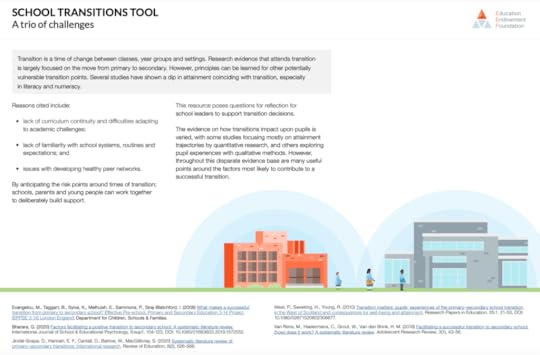

‘School Transitions Tool: A Trio of Challenges’, by Education Endowment FoundationBased on some of the best available research, this accessible tool synthesises three key challenges that emerge at the transition: 1) a lack of curriculum continuity; 2) a lack of familiarity with school systems and routines; and 3) issues with developing healthy peer networks. The resource helpfully makes clear that transition is both a pastoral and an academic challenge. It offers a starting point to identify areas with transition to focus our efforts… SEE HERE.

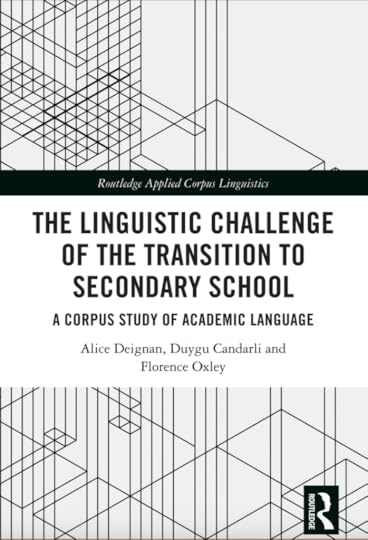

A key issue at the transition is the changing nature of the school curriculum and the academic language it contains. This book freely explains some of the vocabulary challenges faced by pupils in year 6 and then their experience of different, and increasing academic, vocabulary of the secondary school curriculum. The specifics of pupil views, maths and science vocabulary, and more, offer crucial insights…SEE HERE.

The insights into curriculum continuity at the primary secondary transition extend to reading and vocabulary in this valuable research study. Notions of a ‘summer slump’ did not appear and instead the researchers describe the curriculum ‘jump’ that pupils have to contend with at the transition. In many ways, they are positive findings that teachers can build on, but it does require a sensitive awareness to pupils’ language, the curriculum, and more…SEE HERE.

This thorough review of the transition research focuses on the importance of communicating and relationship building with schools, children, and the parents/caregivers. The pastoral focus highlights the importance of effective communications and the exchange of information. Pupils being ‘given a voice’ and families being involved in transition could trigger useful ideas to enhance the transition experience…SEE HERE.

5. ‘Social-Psychological Interventions in Education: They’re Not Magic’, by Yeager and Walton

Though this research isn’t specifically on the challenges of the primary to secondary transition, it does offer some really useful insights into small, manageable approaches schools can undertook to promote belonging and confidence as pupils start secondary school…SEE HERE. Small approaches that can help build confidence are within our grasp, and with careful alignment, could make a small but cumulatively positive difference. [Harry Fletcher-Wood wrote a great blog in 2014 translating these findings into practical approaches for his own pupils – HERE].

Related Reading:‘Thinking About Transition‘. I’ve attempted to summarise some of the key research in accessible terms HERE. ‘The Reading Gap Between Primary and Secondary School‘. I’ve aimed to distil some of the curriculum and reading differences that see reading challenges ramp up the older pupils get –

HERE

. ‘The Language Leap at Transition‘. I’ve narrowed the focus onto the changing language of secondary school and the increased focus on ‘disciplinary literacy‘

HERE

.

Related Reading:‘Thinking About Transition‘. I’ve attempted to summarise some of the key research in accessible terms HERE. ‘The Reading Gap Between Primary and Secondary School‘. I’ve aimed to distil some of the curriculum and reading differences that see reading challenges ramp up the older pupils get –

HERE

. ‘The Language Leap at Transition‘. I’ve narrowed the focus onto the changing language of secondary school and the increased focus on ‘disciplinary literacy‘

HERE

. Image rights – Gordon: https://www.flickr.com/photos/gordon-....

The post 5 Free Research Reads On… The Primary to Secondary School Transition first appeared on The Confident Teacher.January 22, 2023

The Problem with ‘Just Google It’

[I have cross-posted this blog on my Substack. You can follow my newsletter and Substack publications HERE]

The Internet is omnipresent in our lives. The magic of near-infinite knowledge in the palm of our hand would be scarcely believable for most humans since the dawn of history. Access to such knowledge is a boon, but it may prove problematic when it comes to learning.

Access to the Internet makes us smarter, right? We can ‘just Google it’.

But what if access to the Internet impaired our memory and stopped us thinking hard?

Research on ‘‘Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips’ (2011) revealed that when people expect to have future access to Google that they have lower rates of recall for the information. Instead, our brain enhances recall for where to access the information. It is a subtle change of mental emphasis. For adult experts, this savvy use of memory may be helpful, but for novice students learning new knowledge it may prove a problem.

The researchers argue that this ‘mental outsourcing’ can be a threat to learning. For students in the classroom, we need them to allocate attention and mental effort to the material we are teaching them, be it photosynthesis in science or pathetic fallacy in English literature.

Does searching the Internet stunt strategic, hard-thinking?A reliance on the Internet for information can create a habit or reliance on the resource. In a study on ‘using the Internet to access information’, researchers found that participants who used Google to answer difficult trivia questions were more like to use it for a new set of relatively easy trivia questions. So far, so unsurprising. For students, the implications for thinking hard over homework content, or problem solving with access to their phones, is obvious.

Ample evidence from cognitive science has shown that students need to think hard about what they learn to have a chance at understanding complex material. It may be effortful retrieval practice, such as trying to recall that definition of photosynthesis, or it could be the tricky task to self-test on that topic. Alternatively, it could be to explain aloud the meaning of pathetic fallacy and its meaning in Macbeth, instead of Googling some online analysis to pop into an essay.

With easy access to the Internet, it can result in easy thinking, but this may result in fragile learning.

In a recent US experiment, researchers explored the impact of Internet searching. Entitled, ‘Information without knowledge: the effects of Internet search on learning’, the researchers found the problematic presence of overconfidence that attended

Internet searches:

“Across five experiments, participants studied for a quiz either by searching online to access relevant information or by directly receiving that same information without online search. Those who searched the Internet performed worse in the learning assessment, indicating that they stored less new knowledge in internal memory. However, participants who searched the Internet were as confident, or even more confident, that they had mastered the study material compared to those who did not search online.”

We can speculate about the impact on novice students in classrooms. We can all recall that moment where we reached for our phones to find a fact we couldn’t quite remember. In many cases, this access to a wealth of knowledge can save mental energy to do more important, but we can also recognise it could compromise durable learning too.

Implications for ‘Just Google It’ in the classroomNot all information on the Internet is created equally. Every teacher recognises the issues of ‘fake news’ or flawed websites purporting to be factually accurate. If the ease of the Internet search promotes over-confidence, does lowering our critical faculties – stopping more strategic, careful reading – add another issue to the ‘just Google it’ problematic rap sheet?

Within a couple of clicks, a novice pupil could be faced with deeply problematic content but without enough knowledge to interpret it adequately. Students can make one quick Google search for Henry VIII, for their history homework, but end up reading the latest ‘news’ on a Daily Mail commentator berating the National Trust for a supposedly ‘woke’ depiction of the infamous king. A subsequent related search of ‘Woke King’ on YouTube would then take students onto vile criticisms of Martin Luther King!

What are the implications for teachers and students? We need not isolate all technology from learning, but we should retain a note of caution. Outsourcing our efforts to the Internet can inhibit building those rich networks of knowledge so necessary to school success.

Unfettered access to Google may be a near-unimaginable boon to our ancestors – and it is handy for us too – but we should take care to not assume Googling it will lead to knowing and learning it.

Our message to students? You can sometimes ‘just Google it’, but certainly don’t rely on it.

[Pop this one in your bookmarks for later – who needs recall, right?]

Image via Creative Commons attribution: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

The post The Problem with ‘Just Google It’ first appeared on The Confident Teacher.January 20, 2023

5 Free Research Reads on…Teacher Professional Development

It is January and that time of year when we consider new habits, routines and development. As new resolutions begin, we may consider it a good bet to focus some effort on how best to support professional development.

Here is a short selection of freely available reading on effective teacher professional development:

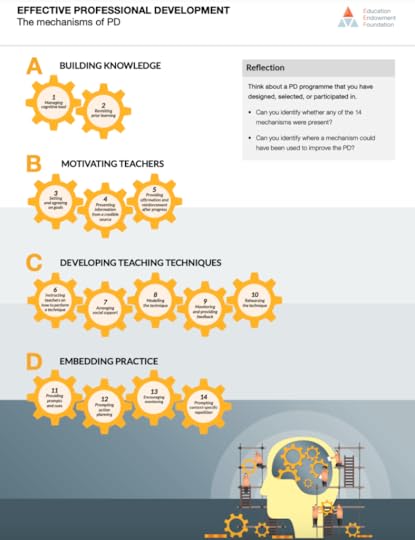

Effective Professional Development – EEF Guidance ReportThis guidance report does a really helpful job of defining what are the key ‘mechanisms’ that can help drive effective professional development. By identifying these supporting mechanisms, paying close attention to developing some of them (such as ‘social support’ or ‘prompting action planning’), you can help support and sustain professional development… SEE HERE.

[Additionally, Professor Rob Coe has written a helpful blog about the guidance entitled ‘Maximising Professional Development’ HERE]

2. ‘Against Boldness’, by Mary Kennedy

It is paradoxical perhaps to suggest that we should not be bold with teachers’ professional development. But, given the sheer complexity of the job, and the difficulties in changing our habits and practices, I think we should be greatly cautious about our ambitions for teacher professional development. Put bluntly, most attempts at PD fail. I think if every school leader read this challenging paper and reflected upon its call for more pragmatic, incremental change, then it would be a better bet that more teachers improve… SEE HERE. [If you’re intrigued about Mary Kennedy – you should be – read a great Harry Fletcher-Wood quick summary of her key work HERE.]

Teacher development needs to be practical and address real issues in the classroom, but it also needs to be supported by some simplified theory in how children learn. Willingham offers a clear argument and practical approaches. Though it is not the business end of professional development, for new and experienced teachers, mental models of the learner, memory, and more can prove helpful… SEE HERE. [Tom Sherrington has offered a compelling argument why a mental model of learning is needed – ‘A Model for the Learning Process: And Why it Helps to Have One‘ – HERE.]

4. ‘Teaching Practice: A Cross-Professional Perspective’ by Dr Pam Grossman et al.

What does the professional development of clinical psychologists, the clergy, and teachers have in common? It turns out, quite a lot. The development from novice to expertise shares lots of common steps and traits. Here, researchers draw upon the professions to argue that we need offer developing teachers ‘representations’ (videos of teaching, lesson plans, curriculum sequences etc), ‘decomposition‘ (we need to break down the complexity into more isolated moves that can be named and framed to aid development e.g. focusing on teacher questioning sequences), and ‘approximations’ of teaching (simulations of teaching, rehearsing with colleagues etc). It is a piece of research that really gets you thinking about precise elements of professional development…SEE HERE. [Expert teachers, like Adam Boxer, relentlessly focus on ‘decomposition’ – breaking down the nuts and bolts of teaching. See Adam’s blog on ‘Ratio lens’ for a great example – HERE.]

Teachers getting better is very specific to the context of the classroom, but we can learn a lot from the rich years of research evidence that characterises ‘behaviour change‘. The specificity about these techniques can prove helpful to steer professional change….SEE HERE. If you want to dig into a whopping 93 techniques, look HERE, but the EEF guidance above does a helpful job of distilling some of the approaches as ‘mechanisms’. [For a shorter overview, Harry Fletcher-Wood writes a great blog on ‘What Influences People? Specifying Behaviour Change Techniques’ HERE.].

If you do find them time to read even some of these documents, it is worth considering most teachers don’t and won’t find the time. Time, tools, support and collaboration, will be necessary.

The post 5 Free Research Reads on…Teacher Professional Development first appeared on The Confident Teacher.January 14, 2023

5 Free Research Reads On… Teaching Spelling

Debates about spelling never really go away. No matter what technological advancement is ushered in, it appears that spelling development still matters and we should sustain the teaching of spelling.

For young writers in particular, spelling is linked to writing, reading and vocabulary development. But teachers need support to understand the challenge and teach spelling with success. These freely accessible reads explore the importance of spelling and its vital place in the classroom.

‘Does Spelling Still Matter—and If So, How Should It Be Taught? Perspectives from Contemporary and Historical Research’, by Pan, Rickard and Bjork.Does spelling still matter? Spell-checking simply hasn’t made spelling instruction obsolete. Spellcheck and autocorrect are not foolproof, but more importantly, reading, writing, and vocabulary development are all linked to the foundational skill of spelling. Spelling can prove a particular constraint of writing development and quality… SEE HERE.

2. ‘What should teachers know about spelling?’ by Misty Adoniou

What should teachers know about spelling? Quite a lot, it turns out. This article outlines that spelling is not an innate skill and it requires explicit instruction. It goes on to detail aspects of that crucial knowledge, from knowledge of phonology (the letter to sound correspondences) and morphology (word parts and word roots)… SEE HERE.

3. ‘Why Teach Spelling?’ by Deborah K. Reed

This is one of the most comprehensive explainers on ‘why‘ and ‘how‘ to teach spelling. It details spelling development and its relationship to reading and writing. It advocates integrating a range of approaches using phonemic, morphemic, and whole word approaches. It comes with a really handy checklist at the end too…SEE HERE.

Is spelling being ‘taught’ or merely ‘caught’? Is the spelling test still king? This small survey of primary school teachers is accompanied by a very good explainer on the state of spelling instruction in England. Insights include formal spelling policies being rare, with a third of teachers not having professional development on spelling in the last five years. With some teachers gaining timely spelling development, is there a growing gap in classrooms when it comes to spelling ability? Read about spelling in primary…SEE HERE.

When you look at a vast array of research on spelling what does it show? Does it develop naturally with a test or two helping it along, or is systematic spelling instruction the difference maker? No surprise here: for all learners, systematic spelling instruction makes a positive difference…SEE HERE.

Related reading:‘Spelling: Avoiding Ignorance and Negligence‘. I have blogged about some practical approaches to spelling

HERE

. ‘How to Teach Spelling Patterns‘. This TES article does what it says on the tin…

HERE

. ‘Closing the Writing Gap‘. My latest book tackles spelling development as part of the writing process…

HERE

(use the discount code GAP30 for 30% off!).

Related reading:‘Spelling: Avoiding Ignorance and Negligence‘. I have blogged about some practical approaches to spelling

HERE

. ‘How to Teach Spelling Patterns‘. This TES article does what it says on the tin…

HERE

. ‘Closing the Writing Gap‘. My latest book tackles spelling development as part of the writing process…

HERE

(use the discount code GAP30 for 30% off!). Image via: https://www.flickr.com/photos/1532782...

The post 5 Free Research Reads On… Teaching Spelling first appeared on The Confident Teacher.January 7, 2023

7 Helpful Vocabulary Websites

The Internet is a minefield of useless websites, but sometimes you can unearth some gems. New AI applications, like ChatGPT, are making the news, with potential for useful vocabulary learning, applications for writing, the classroom, and more. For those seeking useful vocabulary websites, these 7 may just do the trick:

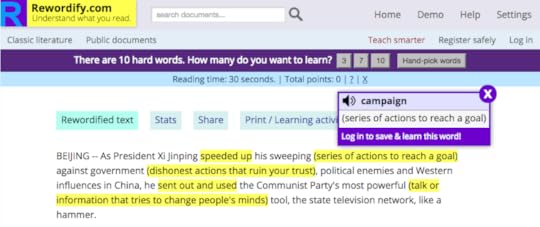

Rewordify.comThis website can take extracts and translate them really helpfully, from identifying complex (Tier 2 vocabulary), to creating glossaries, simplifying tricky vocabulary, and more…SEE HERE.

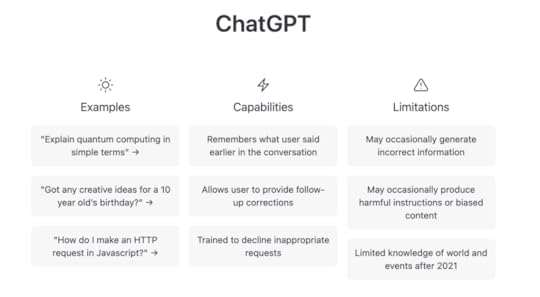

Newly famed, and for some notorious, this AI app is making lots of noise. It can help with vocabulary learning in a whole host of ways. It can explain academic vocabulary, generate vocabulary quizzes, translate sophisticated language into simple alternatives, produce extended writing, generate exam questions, and more… SEE HERE.

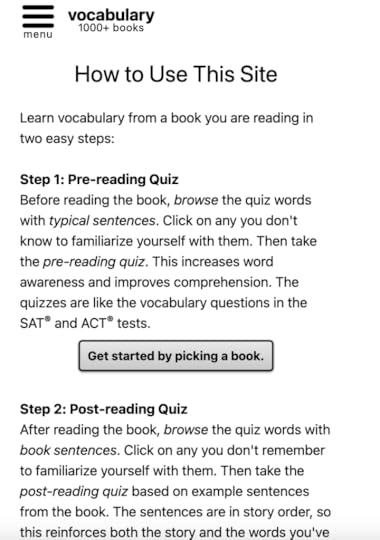

This clever US website takes famous books (particularly literary classics) and it generates some key vocabulary from those books, with related quizzes. You can explore specific vocabulary items from the books too….SEE HERE.

One of the original and best vocabulary websites. Vocabulary.com can function as a basic dictionary or thesaurus, but it really becomes interesting when it comes to its word root and morphology lists. It offers practice questions, quizzing, and spelling tests too…SEE HERE.

Do you ever have a word on the tip of your tongue? The ReverseDictionary offers a simple but powerful solution. Pop in your description of the word and it will offer you a wealth of potential words (with useful synonyms to boot)…SEE HERE.

6. Online Etymology Dictionary

The academic language of school can often be helpfully illuminated by exploring the etymology (the history) of the word. This online etymology dictionary is the original and reliable best…SEE HERE.

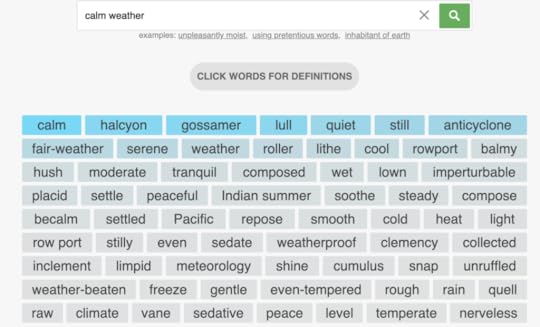

7. Describing Words

This simple website offers a range of descriptive words when you insert a noun into the search engine. This hunt for ‘collocations’ (words that are commonly used together) can offer a rich seam of vocabulary links for homework, story writing or descriptive writing…SEE HERE.

Useful vocabulary reading:

‘5 vocabulary Teaching Myths’

. Too many words to teach? Too busy teaching science to tackle vocabulary instruction? This blog takes on the most prevalent vocabulary teaching myths.‘

Teaching Vocabulary and Mighty Morphemes

‘. Wondering about how to teach word parts effectively? Want to maximise learning 20 words instead of 1 word at a time? This blog explores approaches to morphology and etymology learning.

Useful vocabulary reading:

‘5 vocabulary Teaching Myths’

. Too many words to teach? Too busy teaching science to tackle vocabulary instruction? This blog takes on the most prevalent vocabulary teaching myths.‘

Teaching Vocabulary and Mighty Morphemes

‘. Wondering about how to teach word parts effectively? Want to maximise learning 20 words instead of 1 word at a time? This blog explores approaches to morphology and etymology learning. I am running a Teachology ‘Closing the Vocabulary Gap Masterclass’ on the 20th January in Manchester, as well as beaming it online using Glisser recording technology. Find out more HERE.

Image rights for blog image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/feuilll... ‘Words’ by Pierre Metivier

The post 7 Helpful Vocabulary Websites first appeared on The Confident Teacher.December 3, 2022

Scurvy Seadogs and Using Research Evidence

What was more dangerous for sailors in centuries past: pirates, crushing canon, or storms and shipwrecks? The greatest scourge of sailors in the 16th and 18th centuries was… a lack of vitamin C.

Scurvy – a dietary deficiency caused by a lack of vitamin C – resulted in an estimated 2 million deaths in between the 16th and 18th century. The effects of the deficiency could be devastating. Sailors would lose teeth through softened, bleeding gums. Limbs would swell and develop foul, stinking ulcers. They would become emaciated and bleed from the nose and mouth before suffering a grim, painful death.

Ship surgeons would administer cures that would prove as brutal as the disease. How about drunken bloodletting or drinking diluted acid? One ‘cure’ was stuffing turf into the mouth of the sailor to counter the poisonous vapours of the sea air. Eating rats was another – although, ironically, their vitamin C content could actually help fend off the disease for many hardy sailors!

What have we learned from this gruesome tale? Well, using research evidence matters. It can even save lives, but it may take some considerable time to influence and change behaviour.

James Lind and undertaking research trialsJames Lind joined the Royal Navy as a surgeon’s mate in the late 1730s. This humble doctor would ultimately go onto save countless lives at sea. His small, controlled trial would ‘eventually’ go on to change naval protocols and prove the scourge of scurvy.

In his ‘Treatise of the Scurvy’ (published in 1753), Lind would detail the small trial on board a single vessel – The Salisbury.

In 1747, on board HMS Salisbury, he carried out one of the first controlled clinical trials recorded in medical science. Twelve men suffering from scurvy were each divided into six pairs. The pairs were then administered various remedies including: a quart of cider; 25 drops of elixir of vitriol, three times a day; half a pint of seawater daily; a garlic and gum concoction; two spoonfulls of vinegar, three times a day; along with two oranges and one lemon a day.

What was the winner of the small but vital experiment? Oranges and lemons. The key active ingredient to fend of scurvy was vitamin C.

And so, did this eureka-worthy experiment change everything and immediately begin to save the lives of sailors? Well, not quite.

Unfortunately, Lind himself didn’t quite recognise the significance of his controlled trial. His lengthy treatise was written with a sprawling exploration of the condition so that most readers didn’t recognise the vital value of the trial findings. The vitil vitamin was lost in translation.

It took the Royal Navy around half a century to apply the findings of the experiment into practice. To save money, they substituted oranges and lemons out for limes, as these were cheaper fruits to purchase (you may note that the Americanism attributed to Brits is the term ‘Limey’ – which derives from this practice).

Not only were limes used – that were weaker in vitamin C – but methods to preserve the fruits, such as boiling the juice, could fatally reduce the vitamin C content. Sailors continued to perish for decades.

It took around 42 years before the Royal Navy ordered stocks of lemon juice for sailors.

What can we learn from this seminal research in the killer disease?We will often hear of the scientific breakthroughs that have changed the world. In the last two years, we have lived the reality of scientific trials and advances transforming how we live and saving lives in a global pandemic. But what can we learn from the James Lind story?

Here are five insights from the scurvy story that could prove useful when it comes to using research evidence:

Good leadership values the generation of evidence. It can be a little too easy to take for granted research and development. Though global success stories, such as Apple, invest billions in R&D, public services can see their budgets compromised and their time limited, so R&D gets squeezed out. Carving out research questions, accessing high quality evidence sources, monitoring and evaluating impact, and experimenting and learning, can be woven through our work with effort and intent.Money matters. The Royal Navy chose limes over lemons because of cost. Money matters in carving out time to experiment and learn, but we also need to ensure that generating evidence can save money too. Buying a bunch of useless limes may be an apt analogy for using good quality research to seek out the key ingredients for success. Of course, it will cost money to generate research, but it may saves millions, or even billions, if it stops us wasting money on the wrong solutions.Robust research evidence will still be subject to staunch beliefs and even rejection. Bloodletting and lopping off limbs lingered for years after Lind produced his treatise. We are wedded to our old habits. Even good quality research can be rejected because it clashes with our beliefs and hard won practices. More experiments can help build confidence in the research and go some way to build a shared understanding. We need to research and reason about that research. We need to debate and ask for evidence for prospective changes too. But we need to do more than produce research to support people to change.Clear communication can make all the difference. A regular complaint about research evidence is that is uses obscure language and it doesn’t make sense to the general population. Lind himself may regret labouring over such a lengthy treatise that obscured his key insights. We need to generate good quality research, but we must work just as hard to communicate it well. Busy colleagues also need time boiled into their professional development that offers access, and time to interpret and apply, such research evidence.Isolate your ‘active ingredients’. Good research and development – indeed, any change – works hard to isolate the ‘active ingredients’ of an approach. In short, what is equivalent of the ‘vitamin C’ for a proposed solution or change – the essential ingredient. This will likely require some careful experimentation and access to reliable existing evidence to steer our efforts.(See the Education Endowment Foundation’s Implementation guidance report for more on ‘active ingredients’ HERE).

As scientific research has proven, the march of time can see solutions that save lives and improve our lot. From vitamin C solutions to school improvement plans, accessing research evidence, along with some careful and controlled experimentation, can make a positive difference.

Related links:If you want to accessible research evidence for education, then the EEF might be for you – see the website HERE.

In medicine, The James Lind Alliance (yes, that James Lind!) explores priority research questions for medicine – see the website HERE.

The post Scurvy Seadogs and Using Research Evidence first appeared on The Confident Teacher.November 19, 2022

10 Creative Ways to Teach Vocabulary

“Vocabulary knowledge is knowledge; the knowledge of a word not only implies a definition, but also implies how that word fits into the world.”

Steven Stahl (2005)

Developing vocabulary knowledge is so much more than word lists and student-friendly definitions. Even the most careful curation of vocabulary on a knowledge organiser may only give the illusion of knowledge. Pupils may be familiar with new words, but they cannot use them confidently in their writing or talk.

It is crucial that we help pupils develop a curiosity about words and make rich connections between them, their families, synonyms and antonyms. The need to make countless creative connections. They need to know words, but most crucially use them by weaving them into their writing.

Rather than dishing out the dictionary and thesaurus (they will routinely use these tools badly without careful training and practice), we need to ensure creative vocabulary strategies promote an awareness of words in use and how they fit in the world.

Here are 10 strategies that can be used to teach pupils to connect new vocabulary:

‘Connect 4’. This strategy is a simple way to isolate, emphasise and connect key vocabulary, whether it is reading a textbook in science, or exploring the Great Fire of London in Year 2. For example, in history, you could select the four words – ‘continuity’, ‘monarchy’, ‘power’ and ‘conservatism’ – thereby priming a given topic. Then you ask pupils to make as many connections between the words as possible – the more the better.‘Simple <> Sophisticated’. With this modelling strategy, teachers can quickly and repeatedly model apt word choices, in both verbal responses and in their writing. For example, if a pupil uses the word ‘sweat’ in Biology, then the teacher may model the use of ‘perspire’. We can use such pairings repeatedly and discuss the choice e.g. old >, or ask >< interrogate etc. Crucially, pupils need to develop an awareness that often the simple word is more apt, thereby avoiding the excesses of ‘thesaurus syndrome’.‘Engaging Etymologies’. A common strategy for all learning is to tell memorable stories. Given this fact, telling the story of the history of academic vocabulary can make for great teaching. For example, to better understand social attitudes to sex, you can help (older) pupils understand contentious words like ‘slag’, including how this industrial term became a label for promiscuous women. Common words we use can routinely have their history unveiled: did you know the Latin origins of the word ‘trivial’ emerge from casual chats where three roads meet? ‘Said is dead’ . In English, but also in history, geography, religious education and more, the use of ‘said’ is part of the fabric of academic writing. A concerted focus on alternatives, such as ‘shrieked’, ‘wailed’, ‘exclaimed’, offer alternatives in fiction writing. More neutral terms for essays can include ‘stated’, ‘observed’, ‘explained’ and ‘revealed’. We can also be more intentional about where said makes sense, but be creative about its variation too.‘Vocabulary triplets’. A historian writing an essay, or an artist annotating their sketches, all require well-chosen academic vocabulary. This strategy simply offers pupils three words to choose from, or synonyms, so that we can begin to shape their apt vocabulary selections. For example, in history, you may offer pupils the choice between ‘possibly’, ‘perhaps’ and ‘certainly’, to describe a specific source. By offering up potential answers, you let pupils concentrate on precise word choices, thereby honing their writing skill.‘Word chains’. We want to make explicit to our pupils that they should connect academic words to words they already know, along with other ideas and concepts. With this approach we encourage students to make as many connections as they can. Those pupils who can add most links create the strongest chains. For example, in Music, GCSE students who are given the term ‘pitch’ need to make links like ‘range’, ‘register’, ‘sharp/flat’ and ‘pentatonic’. Verbal explanation of these chains is a natural next step.‘Word building’. The ‘word building’ approach is about generating as many words as possible from common roots. For instance, in science it may the root ‘photo’ – meaning ‘light’ – that can prompt inquiry into words like photosynthesis, photon, photography and photobiotic. Similarly, in music, ‘phon’ – meaning ‘voice or sound’ – can generate words like polyphony, symphony, cacophony and euphony. Word mapping. Akin to concept maps, ‘word mapping’ connects words with the head word proving the main topic. For example, with ‘geothermic processes’ as a head word in geography, this would be followed by ‘endogenic’ and ‘exogenic’ processes. Each of these word headings then connects conceptually to other related words and processes. It is simple stuff, but it brings coherence and clarity with subject specific ideas that can prove difficult and abstract for some pupils. Asking pupils to explain their visual representations of their maps can lift the approach up a level. ‘Six degrees of separation’. The simple idea of this game is that all living things in the world are connected, or by six or fewer steps. Well, this little knowledge game works well enough for making linguistic links too. Take the following vocabulary links between ‘abnormal’ and ‘supercilious’. Straight away, pupils need to draw upon their vocabulary knowledge – of synonyms, antonyms, and more – before then drawing upon their personal word-hoard. My effort? Abnormal > strange > mysterious > special > superior > supercilious .Keystone vocabulary. Pupils need to build rich connections between words and how they represent concepts or topics in the world (often labelled schema development). ’Keystone vocabulary’ is the identification of a small number of key words that may offer foundational understanding of a topic. For instance, if pupils are learning about the Great Fire of London, we may select ‘capital’, ‘natural disaster’, ‘inferno’ and ‘urban’. Talking about these words, unpicking them, and linking them up, can make vital connections.Related reading: Three Pillars of Vocabulary Teaching . A post on the three pillars: 1) Explicit vocabulary teaching 2) Incidental vocabulary learning, & 3) Cultivating ‘word consciousness’. Academic vocabulary and schema theory . This post explores examples of how to connect words into coherent schemas – the creative connections at the heart of this post. The Problem with Teaching Sophisticated Vocabulary . Teaching vocabulary connections doesn’t always go smoothly. This blog explores some of the pitfalls and nuances of supporting pupils develop their vocabulary.The post 10 Creative Ways to Teach Vocabulary first appeared on The Confident Teacher.November 4, 2022

The Problem with Teaching Sophisticated Vocabulary

Should the title be ‘sophisticated vocabulary’, or could it be more simply ‘fancy words’? Small but significant language choices like these occur repeatedly in classrooms – and in pupils’ minds – daily. Teaching pupils to use sophisticated vocabulary can go wrong but it is a necessary bump in the road of pupils’ language development.

We can quickly spy when pupils go wrong. It is particularly obvious when they tend to write in an over-elaborate style in the classroom – commonly labelled ‘purple prose’ (purple because it was the colour of royalty and therefore gilded and excessive rich).

The issue of assuming bigger words are better, or misusing sophisticated vocabulary, is nothing new. In fact, Quintilian, one of the famed early teachers of writing during the Roman Empire, complained about the “corrupt style” of his pupils. Over two thousand years ago, he bemoaned “purple patches” and labelled them as “stilted bombast” and “blossoms of eloquence” that would easily fall (1).

Teachers today shouldn’t berate themselves for the predictable problems of their pupils try to overdo vocabulary. Instead, we should recognise that it is a natural stage of imitation that occurs in the safe confines of the classroom. Most novelists, poets and journalists, will describe their imitation of the styles of their favourite writers along their path of development. A bit of purple prose, it appears from thousand years of evidence, is natural and a part of the maturation of pupils’ developing vocabulary use.

As a truculent teen (who quietly wanted to impress his teachers), I once collated a sheet of seemingly impressive vocabulary cribbed from the dictionary. It attempted to weave it into my English lesson writing and beyond – with mixed success I am sure. Perhaps it didn’t do the job, but it did no harm (I still remember many of those vocabulary items today). For our pupils today, we can encourage them to develop their word hoard, but also, crucially, to make judicious word choices.

Supporting pupils to make apt vocabulary choices

What makes a word choice particularly fitting, apt, or appropriate? Well, of course, it depends on the job it is doing in talk or writing. Sometimes smaller words punchier and better…or more apt. Sometimes words that are more sophisticated, or more formal, are needed to do the job.

Alas, we cannot rely on the dictionary or thesaurus to be used well our pupils. Famous research from George Miller and Patricia Gildea, entitled ‘How Children Learn Words’, reveals some of the missteps by pupils trying to work synonyms into their writing.

A couple of comic examples they relate include switching ‘Mrs Morrow stirred the soup’ to ‘Mrs Morrow stimulated the soup’. Another, even better, was substituting eroding for ‘eats away’ in the sentence ‘Our family erodes a lot’. Even when children were given words in a sentence, or three, they could still struggle if they lacked word knowledge. The misuse of fancy words is not uncommon, sometimes comic, and it offers a teachable moment in the classroom.

Of course, the solution is not to only aim for simple words. The world, and our pupils, would be duller if that were the case. Instead, we can guide them to make more considered choices, to revise their writing, and to adapt their vocabulary appropriately to the task. We can celebrate and craft pupils word choices daily. When they use a sophisticated word that doesn’t quite work, we can sensitively recast it in our classroom talk. When it comes to writing we can do similar.

There are practical strategies that can promote the judicious selection of synonyms, but with more care taken over nuances of meaning and using those words well in sentences. Here are a few such approaches:

Clearly, Quintilian himself was prone to a bit of bombast and ‘purple prose’.The post The Problem with Teaching Sophisticated Vocabulary first appeared on The Confident Teacher.

‘Vocabulary 7-up’ is a simple vocabulary game that encourages pupils to record as many synonyms as they can for common words (seven ideally!). So, given ‘positive’, ‘effective’, ‘large’ or ‘small’, our students exercise their capacity to draw upon a range of synonyms for those words. This activity assesses their breadth of vocabulary but also overtly signals to students the necessary variety of words required in academic expression, whilst offering a forum to choose the right word for the right job.

‘Word Triplets’ offers students three words to choose from, or synonyms, so that we can begin to shape their apt vocabulary selections. For example, in history, you may offer students the choice between ‘possibly’, ‘perhaps’ and ‘certainly’, to describe a specific source. Pupils then select from the triplet and have to use the word and justify its use. By offering up potential answers you let students concentrate on precise word choices.

‘Said is dead’. The use of ‘said’ is part of the fabric of academic writing. A concerted focus on crafting alternatives, such as ‘shrieked’, ‘wailed’, ‘exclaimed’, offer useful variation for fiction writing. Whereas more neutral terms for arguments and essays can include ‘stated’, ‘observed’, ‘explained’ and ‘revealed’.

‘Simple >< Sophisticated’. Teachers can quickly and repeatedly model apt word choices, along with the movement from simple to sophisticated, and the reverse when it is needed. For example, if a pupil uses the word ‘sweat’ in Biology, then the teacher may model the use of ‘perspire’. We can use such pairings repeatedly and discuss the choice e.g. old >, or ask >< interrogate etc.

Word gradients. A common approach is to have pupils discuss and select from a range of word choices – debating their meaning and value for a given task. For instance, a simple range of synonyms for old may prove useful in making conscious word choices: old, ancient, archaic, or antediluvian. Trying them on for size, with some feedback and reflection, can drive out the false notion that bigger is always better, or that an audience want to be assaulted with a plethora of polysyllabic words!

September 17, 2022

Developing Skilled Readers (Knowledge + Strategy)

Take a read of this passage, entitled ‘An Encounter at Sea’, from the 2017 reading comprehension SATs paper. Can you predict what happens next?

What did you predict? Did you assume the ‘encounter’ was a dolphin (noting their mention in paragraph 2), perhaps a shark attack (for the ‘Jaws’ aficionados), or even a whale (‘Moby Dick’, anyone?) for a more dramatic and dangerous encounter? Maybe the encounter was another boat, or an approaching storm?

Now, let’s concentrate on that reading comprehension strategy of ‘prediction’ that you deployed.

It makes sense to encourage prediction with narrative texts because we assume that most readers can draw upon a vast store of story structures and genre knowledge. Questions and discussion attending predictions helps pupils activate their background knowledge of similar stories, structures, and patterns of language… if they possess enough knowledge to generate their predictions.

Such knowledge of stories, and their structures, complex patterns of characters, themes, and language, is like the sea in the Michael’s encounter: it is deep, wide, and vast, and – though not wholly visible – it proves vital to the entire story. As such, the ability of pupils to make meaningful predictions, and to comprehend what they read, rests upon a sea of background knowledge.

As E. D. Hirsh pithily put it:

“To grasp the words on a page we have to know a lot of information that isn’t set down on a page.”

For 11-year-old pupils, sitting and reading their SATs paper under timed conditions, the task is very demanding. They must get to grips with multiple texts that require a vast store of background knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, understanding of genre, audience, imagery (“baby finger crease”, anyone?), and more. Additionally, they need to be strategic: quickly clarifying the meaning of words, predicting next steps in the story structure, or questioning whether their prior knowledge of stories and informational text topics applies to the text at hand.

Knowledgeable readers who deploy timely strategies succeed in SATs and go on to access the curriculum in secondary school.

The reading jigsawWe can use the analogy of piecing together a jigsaw to describe the complex act of building comprehension every time we read, whether it is a story in year 6, or a textbook chapter in year 9 geography.

Let’s imagine that knowledge of vocabulary, genre, and understanding of structural features, along with identifying patterns of imagery, are the essential pieces of the jigsaw (read Professor Dan Willingham’s article on ‘How Knowledge Helps’ on why all the pieces matter). Reading comprehension strategies like ‘prediction’, ‘questioning’, ‘clarifying’, ‘summarising’ and ‘activating prior knowledge’ are the strategies to marshal the pieces of the jigsaw – just like starting with the corners – or clustering by colour when strategising your jigsaw (read Professor Tim Shanahan on ‘Comprehension skills or strategies: Is there a difference and does it matter’ to identify the value of reading comprehension strategies).

With the aforementioned story, getting you to predict what may happen next, or clarifying the reference to the dolphin, can go some way to activating and steering your background knowledge to piece together full comprehension. Broadly, such reading comprehension strategies help pupils to better organised their crucial background knowledge to construct the big picture of the text (known as a ‘schemata’ or a ‘mental model’ in various research interpretations).

We can take the jigsaw analogy and simplify the complex act of reading comprehension as follows:

Alas, like many simple models or analogies for complex acts, it isn’t quite so simple (!), but let’s go with the analogy.

The importance of building background knowledgeWhat happens when you lack vocabulary knowledge, or knowledge of similar story structures? Well, you miss fundamental pieces of the comprehension jigsaw. No comprehension strategy can help a pupil who does not have the knowledge to understand the words, structures, or patterns of a story or text.

Why do so many pupils lack the background knowledge to comprehend new, unfamiliar texts? For too many pupils, they lack deep reading experience of years of rich reading that develops knowledge of the predictable patterns of imagery, along with the rare and sophisticated vocabulary, that populates books and the perennial reading texts of the school classroom.

These pupils are continually missing vital pieces of the puzzle, so their comprehension is partial and compromised each time they read. They don’t remember what they read because they do not gain a coherent full picture of it, and this problem is compounded each time they read or return to topics in the school curriculum. Pupils who lack knowledge of the texts, genre, and words the read in the classroom don’t improve with a regular diet of reading comprehension strategies alone. We need to pay attention to connecting developing background knowledge and reading experiences into a coherent, sequenced curriculum.

So, if we know background knowledge is so crucial to reading success, then what is the problem? Well, it appears we don’t always support struggling readers to build this knowledge.

Instead of starting with a careful curation of background knowledge – such as reading related texts on topic, and doing lots and lots of reading, we may spend too much time aping national reading comprehension assessments, such as the SATs reading paper, or GCSE English language questions.

Paradoxically, pupils read less if they are doing too much practice of reading comprehension exam style assessments, with truncated reading extracts, and writing answers to legions of comprehension questions. If pupils only experience a diet of lots of short, disconnected texts, then they won’t be exposed to the complex demands of academic reading that build a rich, full picture of background knowledge and the pleasure that attends familiarity with a genre or topic.

Of course, pupils need some practice of national reading assessments, so they can understand the time pressures and gain some familiarity with question types. But, crucially, to succeed in those reading comprehension assessments, we need far fewer mocks and mini-faux exams dressed up as reading, to free up curriculum time to read whole texts. Whole texts that develop arguments, extend descriptions, slowly reveal characters. Whole texts that invariably don’t fit into easy bitesize worksheets with easy acronyms. IN short, reading that is compellingly challenging so that strategic thinking is necessary and worthwhile.

Is developing background knowledge enough?So, if we just teach them all they need to know in an organised reading sequence, will that do the trick… background knowledge is everything, right? Well, not quite!

We cannot simply teach all the background knowledge at the exact right time and in the exact right order (though sequencing knowledge is a meaningful task for teachers). Research studies have revealed the struggle to translate the teaching of background knowledge to direct gains of general reading comprehension. A reality is that pupils, especially in school, will need to strategically tackle texts that introduce new topics, ideas, and words. As such, a clear focus on knowledge building can be aligned with some timely strategy instruction (often rich classroom talk about the text at hand).

Let’s return to the formula:

Background knowledge + reading comprehension strategies = skilled reading

For decades there have been ample evidence for the efficacy of reading comprehension strategies. Strategies like ‘prediction’, ‘clarifying’ and ‘summarising’ are familiar in almost all classrooms to help pupils delve beneath the surface of unfamiliar topics and texts. They become valuable when pupils are piecing together the background knowledge they do possess with the new ideas, words, imagery, and ideas that they are being exposed to as they read the new text in the classroom.

What may have been lost over the decades is the apt weighing of the skilled reading formula. The EEF Teaching & Learning Toolkit entry on ‘Reading Comprehension Strategies’ reveals behind the average that:

Strategy instruction is likely brief – and is revisited briefly too. As such, there is little justification for practising endless ‘prediction’ questions each week of the school year in the hope pupils become better readers, if we pay too little attention to the ‘what’ of the prediction.

We can conceive curriculum development as cohering around the ‘what’ of the books being read and the topics being selected and connected. You can start with the reading selection and then strategy instruction emerging out of the specifics of those texts.

If we want 11 year olds to read and comprehend ‘An Encounter at Sea’, then practising reading short extracts is unlikely to offer the benefits of reading more extended fiction. Instead, reading the actual novel which the encounter is from, ‘Whale Boy’, by Nicola Davies

[SPOILER: beneath the surface in ‘An Encounter at Sea’ lurks a whale!]

Perhaps this fiction could be reinforced by reading science texts about evolution and inheritance or the oceans of the world, and/or learning about Jonah, Moby Dick, and more. When reading related texts – fiction or informational texts – it helps pupils make connections, meaningfully repeated, and deepens understanding of ideas and vocabulary and popular powerful cultural imagery. Predictions become meaningful and more likely to be made by pupils.

Let’s simplify some of these insights for better developing skilled readers in the classroom:

Start with careful planning a broad and balanced curriculum that brings a world of knowledge alive. Ensure pupils do lots and lots of reading of challenging texts. Support pupils to develop, connect and cohere their knowledge. Give pupils targeted, text sensitive support to deploy reading comprehension strategies, with a gradual release of responsibility. Avoid over-practising comprehension assessments that can compromise curriculum time for read extended texts. Related reading:Professor Huw W. Catts has written an article for the American Educator on ‘Rethinking how to promote reading comprehension’ .Caroline Bilton has written an EEF guest blog on ‘ Teaching Reading – Embedding Comprehension Strategies’ .I had the privilege to host an EEF podcast on the ‘ Exploring the complexities of reading comprehension ’.The post Developing Skilled Readers (Knowledge + Strategy) first appeared on The Confident Teacher.Alex Quigley's Blog

- Alex Quigley's profile

- 12 followers