Alex Quigley's Blog, page 14

September 10, 2022

Does writing *really* matter in art and design?

What do you assume are the skills of a successful art and design pupil? Perhaps you consider an understanding of perspective and proportion, colour and tone, or knowledge of different media, all deployed with creativity. We know pupils must do some writing in art and design, but it doesn’t *really* matter so much, right?

Though we associate art and design with expression in paint and similar, or the production of creative products, there is a significant amount of writing required to succeed in the classroom. You find it in researching products or painting, annotating, evaluating, and more.

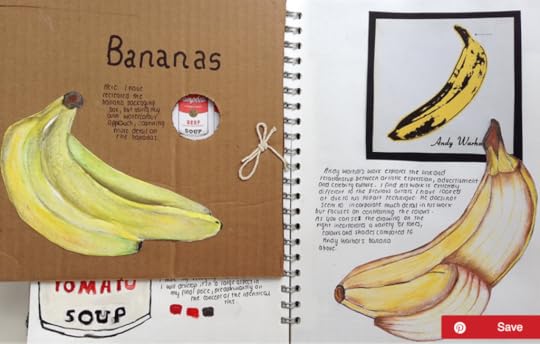

Consider this question: what writing was undertaken in the production of this piece of art planning?

This young and skilled artist is also very literate. Likely they read lots about Andy Warhol and made notes to record those insights, processing and distilling their understanding to inform their own artistic moves. There is the visual of Warhol’s banana image, but in the writing there is the vital recognition of the links between style, medium, and Warhol’s pastiche of advertisements.

For pupils’ portfolios and projects at secondary school, the ability to annotate your plans and finished projects is vital. Not only that, but pupils are also expected to evaluate their ideas in writing.

A near-hidden reality is that pupils need to do a lot of research, reading and writing to interpret the ideas of great artists or other products designers. You could fairly argue that you could read up on Abstract Expressionism, but not have the skill to paint with mastery of brushstrokes or colour. And yet, there would be few advanced qualifications or professional roles that didn’t assume the knowledge and skill of writing about research or products that attending the creative acts of design or art.

Practical strategies to improve writing in art and designAmple research evidence indicates that writing about you read improves your comprehension and memory of the reading material. Making judicious and well organised notes is a skill that is too often assumed.

It is helpful then to support novice pupils with organising their notes and insights via graphic organisers. From relations diagrams to concept maps or Venn diagrams, different graphic organisers help communicate different ideas (see Oli Cav’s brilliant doc on ‘Organising Graphic Organisers’ HERE).

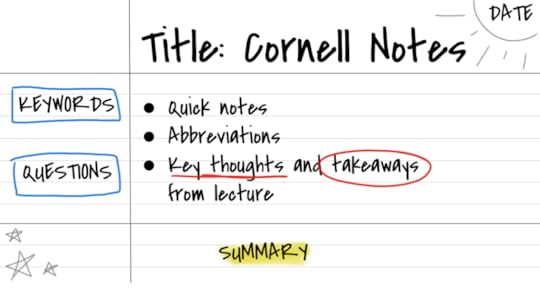

A popular approach to organising notes across different subject disciplines is the Cornell Note-taking Method:

The Cornell method is useful for a variety of reasons. First, it ensures we explicitly teach pupils that note-taking requires some hard thinking and purposeful organisation. Being prompted to note key vocabulary and questions to consider ensures pupils are being more precise about the information they need to use and retrieve. Additionally, summarising helps ensure pupils elaborate and attempt to synthesise their knowledge.

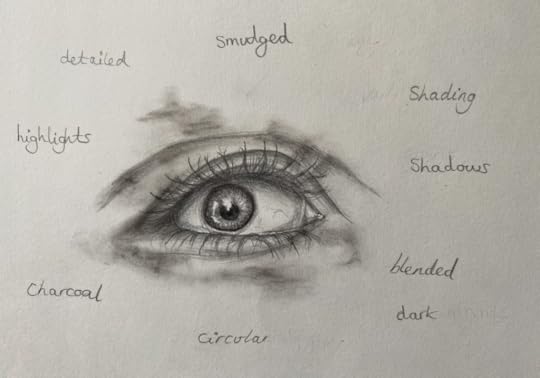

Another area of writing that is too often assumed to be done with understanding by novice pupils is art and design annotation. We all know a spattering of key words is broadly the approach, but if the annotation is to be purposeful, it is an opportunity to record the specialist vocabulary of artistic technique and meaning that we want pupils to remember and use habitually.

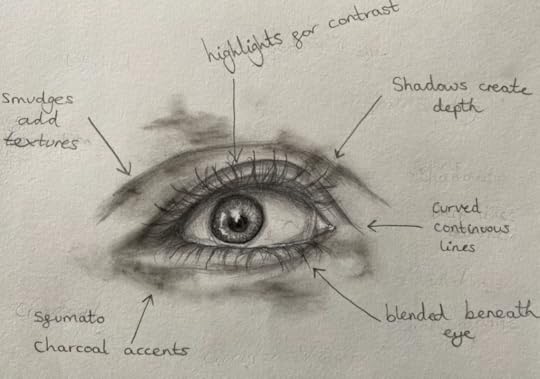

As such, a small prompt to move from single-word annotations to ‘Three-word annotations’ can enhance pupils use of precise subject terminology and makes for accurate, skilled annotation. The exam specification may deem single word annotations adequate, but more precise, detailed annotations can help develop knowledge and understanding that is better than adequate and goes beyond the narrow boundaries of the specification.

Compare this before and after, from single word annotations, to scaffolded ‘Three word annotations’:

The more precise and detailed annotations allow the pupil to exhibit their understanding, but also it allows for more targeted, purposeful teacher feedback too (for instance, for the next project, you could fairly ask the pupil to concentrate on the use of ‘shadows and charcoal accents’). When you add the specialist subject language consistently into note-making and annotations you support pupils to habitually use accurate and precise disciplinary language. They better write, talk and communicate like artists and designers.

Such writing habits obviously ensure that pupils’ writing for design coursework or examinations are more likely to use apt academic terminology. It is common to use writing scaffolds for such projects. For instance, with a Year 7 design technology new product brief, you can begin with the cluster, ‘First…furthermore…so that…’ to introduce your product, followed by a cluster to focus in on one specific element of the product development, such as ‘Due to…for this reason…notably…’.

Additionally, ‘So that sentences’ stand out as a manageable and meaningful scaffold to use regularly in art and design. Pupils take a technique in an evaluative sentence and ‘so that’ prompts their purposeful explanation:

I used [Art technique] so that Please view this post in your web browser to complete the quiz..

I used the sfumato technique for the face so that the portrait appeared soft and youthful in contrast to the harsh, jagged lines of the busy street background.

Structuring more extended writing can be scaffolded at the whole text level too. For instance, in art, Rod Taylor’s ‘Content, Form, Process, Mood’ structure can offer a useful set of prompts to scaffold the written analysis of any work of art.

Too often, we deem artistic creativity as a rare gift bestowed on a lucky few. But every genius artist and designer has undertaken a long path of practice and careful, incremental improvement. Lots of drawing, planning, moulding, creating, painting, planning, evaluating. Success in art and design is borne out of these small improvements, practised week after week. Writing too is woven through this lengthy pursuit of art and design excellence – with explicit attention on research, annotation, note-taking, and more.

Does writing *really* matter in art and design? Yes… yes it does.

Related reading: The strategies from this blog are drawn from my book, ‘Closing the Writing Gap‘. You can grab a copy on Amazon HERE or from Routledge HERE . This blog describes ‘disciplinary writing‘. To find out more about the importance of ‘disciplinary literacy‘ more broadly, read the EEF guidance report on ‘Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools‘ HERE . The post Does writing *really* matter in art and design? first appeared on The Confident Teacher.September 3, 2022

Why teaching academic vocabulary matters

A new school year begins, full of old routines and new challenges. It is only natural to seek out novel ideas to start the year afresh, but we should be wary they are not at the expense of long-held priorities and practices. The teaching of academic vocabulary is one of those priorities that still matters.

Let’s begin with some recent, familiar school reading: the summer SATs paper for KS2 from this year. Read this paragraph from the third reading passage from the national assessment:

I was suddenly aware how quiet it was. I might have been the only person in the world. Even the clock stopped ticking, and the mice ceased rustling in the wainscot. I turned my head and saw a lady coming downstairs from the upper floor. She was dressed in a black dress which swept round her like a cloud, and at her neck was a narrow white frill which shone like ivory. Her eyes were very bright and blue as violets. I sprang to my feet and smiled up at her, into the beautiful grave face she bent towards me. She gave an answering smile, and her deep-set eyes seemed to pierce me, and I caught my breath as I stood aside to let her pass. I never heard a footstep; she was there before I was aware.

What do you notice about the SATs reading passage as an expert adult reader? Perhaps you notice the similes and the stark imagery of piercing eyes, or detect the building tension and sensual details familiar to a suspenseful ghost story.

Of course, vocabulary knowledge required to make sense of this passage. Words like ‘ceased’, ‘wainscot’, ‘frill’, ‘ivory’, ‘violets’, ‘sprang’, ‘grave’, ‘pierce’, all matter greatly to comprehension. Perhaps ‘wainscot’ can understandably be dismissed as extraneous to the drama of the description. By contrast, the meaning of ‘grave’ appears redolent with layers of meaning that is more important for understanding. Understanding ‘grave’ and ‘pierce’ are crucial to deep comprehension of the passage.

What is clear is that the language of what we read in passages like this is different to our daily talk. The vocabulary is more rare, the sentence structures more complex, the patterns of imagery more elaborately constructed. Research from Professor Kate Nation and colleagues – entitled ‘Book Language and Its Implications for Children’s Language, Literacy and Development’ – reveals the many differences between book language and daily talk.

This academic ‘book language’ needs teaching. In various guises, vocabulary instruction may include pre-teaching, such as identifying a key word in a text (such as ‘grave’), explaining its meaning, and recording it using a Frayer model. Alternatively, pupils may be encouraged to discuss ‘grave’ after reading, or to independently record important items on a ‘vocabulary bookmark’, or similar.

This school year, next school year – any school year – high-quality vocabulary teaching will matter to mediate the complex language of the classroom.

Academic vocabulary in different key stages, subjects, and text typesLet’s move to an informational text in geography, for older pupils, from an AS Geography Fieldwork Insert from a past AQA exam, which defines the term ‘interception’:

“Interception is the process where water is retained in the vegetation canopies. The rate of interception is likely to change with land use. Woodland areas are likely to have higher interception rates after a precipitation event because a proportion of the rainfall is retained. Areas with less vegetation would have lower interception rates. Areas with higher interception rates are likely to have less overland flow because some water will be recycled into the atmosphere through evaporation, and some will be infiltrated into the ground.”

You’ll notice the ‘nouny’, dense vocabulary that fills the paragraph which characterises the academic language of so many school texts. Tricky, dense noun phrases such as “vegetation canopies” and “lower interception rates” characterise this type of informational text. Pupils themselves recognise the “complicated”,” posh words” that they have to grapple with. The difference between the SATs story are significant and mark some of the stark differences with the language of the secondary school curriculum.

The familiar language of home can sometimes even interfere with understanding this classroom language. Vocabulary like ‘interception’ is polysemous – that is to say, it means one thing in geography and another thing in the real world. It would be understandable for pupils to mistake ‘interception’ as something that happens on a football or rugby pitch if they were to quickly skim it!

This is the ‘vocabulary gap’ that teachers recognise writ large each time pupils read and in almost all classrooms. The ‘gap’ is no reflection on the rich, valuable language pupils use with their friends at football, or with their family; but it is a reflection of the language of the classroom is so challenging and diverse that it can mean many pupils struggle to understand it. To understand this tricky vocabulary is to have the tools to succeed in school.

Vocabulary and complex curriculum questionsWe cannot teach all the words in the same way, nor in the same depth. A primary school teacher may choose to pre-teach ‘grave’ to initiate pupils’ thinking before reading a particular ghost story passage, or they may raise the word in discussion after reading the passage. A geography teacher may pre-teach ‘interception’ alongside ‘evaporation’ in depth, but not choose to give other academic words the same degree of attention. Not all academic words are equal, so planning and curriculum design really matter.

We are left with complex curriculum and teaching questions:

What are the most important words to teach?What are the ‘keystone vocabulary’ items to connect in curriculum topics?What words will we pre-teach explicitly, compared to the words which may receive a quick check for understanding?What words should we deliberate over and what words should pupils discover?How will pupils learn, record, and be supported to remember key vocabulary?Such difficult questions require professional development and planning time. There is no silver-bullet word list: vocabulary instruction is much more complex than that. This complex but vital aspect of understanding, learning, teaching and curriculum, needs to be sustained and maintained as a priority.

Best wishes with your vocabulary teaching this year.

Related reading: Three Pillars of Vocabulary Teaching . A post on the three pillars: 1) Explicit vocabulary teaching 2) Incidental vocabulary learning, & 3) Cultivating ‘word consciousness’ 5 Vocabulary Teaching Myths . An evidence-led challenge to the common myths that critique vocabulary teaching. Edutopia: ‘New research ignites debate on the ’30 million word gap’ . This article is a good overview of critiques of the famous Hart & Risley study on the ’30 million word gap’, along with more recent research. Note: though some studies have limitations and deserve critique, the wealth of studies assert the importance of vocabulary development. Academic Vocabulary and Schema Building . An exploration of how (and why) connecting vocabulary into rich schemas of knowledge is essential for pupils.The post Why teaching academic vocabulary matters first appeared on The Confident Teacher.July 9, 2022

Is teaching writing the ‘Neglected R’?

If you can write well, you can succeed in school. But the impact of being unable to write with confidence can be crippling, in the classroom, as well as far beyond the school gates.

The recent White Paper on ‘levelling up’ education by the government, predictably attempts to address writing and the age-old ‘3Rs’. By 2030, the government wants the number of primary school children achieving the “expected standard in reading, writing and maths” to reach 90%.

Despite widespread recognition of the importance of writing though, it is routinely the ‘Neglected R’ when compared to reading and a(r)ithmetic (maths).

Many teachers don’t feel confident teaching writing, it doesn’t feature so highly in school inspections, nor does it feature so ubiquitously as a priority in school improvement planning. This relative ‘neglect‘ means it doesn’t have the cottage industry of supporting products, apps, and intervention programmes that accompany the likes of reading.

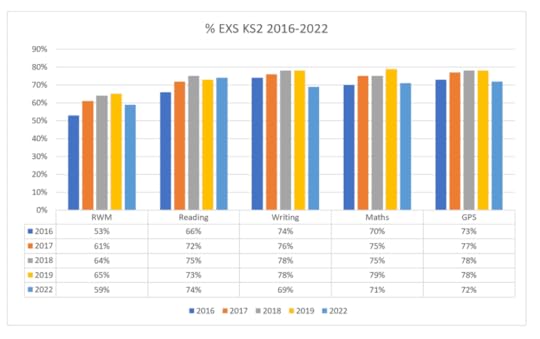

Has writing got worse as a result of the pandemic? [Graphic from James Pembroke of SigPlus]

[Graphic from James Pembroke of SigPlus]Do these plummeting results reflect the unique impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and partial school closures on writing development? What can we realistically infer from this teacher assessment (usually more generous than standardised testing)? Is it an anomaly, or it is representative of a wider issue with pupils’ writing development in schools?

We can speculate that the conditions of the pandemic made it hard to support and sustain pupils’ writing development. Reading at home during partial school closures, along with a legion of maths apps, may have been easy to deliver than the complex act of improving writing.

There is a peculiar magic when it comes to developing writing in the classroom that was missed. Pupils get ample feedback on drafting and crafting writing. Complex writing tasks are broken into small steps and modelled. Pupils of all ages hear the examples of peers, often writing collaboratively or collectively, and have a live audience to ensure that editing (correcting errors) and revising their writing is completed with due care and attention.

Additionally, many parents may have lacked the confidence to support their children with writing. With my son, I quickly recognised his handwriting had been affected by reduced practice, never mind spelling, grammar, planning extended writing, and more.

What do we need to do about writing?We should not have any knee-jerk reactions to SATs outcomes, but we should be conscious that developing writing has always been tricky and too many pupils have failed to develop their writing skills.

If we live in a country where functional illiteracy affects millions of families – before the corrosive impact of the pandemic – then we need to pay equal attention to all of the 3Rs. Indeed, writing may even matter more right now.

So, what do we need to do about it?

Across the world of education, there have been calls for a ‘writing revolution’ and an awareness that new teachers (and old) can struggle with the teaching of writing. Research indicates it may lack the requisite curriculum time and training for schoolteachers.

For 90% of pupils to master such a complex skill requires sustained support and expert teaching. It requires policy support and thorough planning. If teachers struggle with teaching writing, then training and sustained focus on professional development will be key. From early writing – to disciplinary writing in secondary school subjects, as pupils develop to ‘write to learn’ – there needs to be a roadmap for teacher knowledge and practice.

There is likely a need to revisit national assessments for writing. Does the GPS (Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling) test in year 6 translate to better writing? Is writing assessed and developed well into secondary school?

Beyond testing and assessment, do we need to focus school improvement attention on writing progression in the curriculum? Does handwriting need a higher profile? Can we support spelling beyond weekly testing? Can we explicitly teach the writing process more consistently and successfully?

Do we need to revisit our curriculum intent when it comes to improving ‘writing like a historian‘ or a scientist, and more (the stuff of ‘disciplinary literacy’, twinned with subject expertise)? As an ex-secondary school teacher, I may even offer the provocation that writing is routinely neglected – based largely on a lack of awareness and intent to address the issue.

Aiming for 90% of pupils leaving primary school as strong writers may be a laudable aim, but it will we not get anywhere near if writing continues to be the ‘Neglected R‘.

The post Is teaching writing the ‘Neglected R’? first appeared on The Confident Teacher.June 18, 2022

Teaching Vocabulary and Mighty Morphemes

How do you teach a tricky new word, or seek to boost the word hoard of the pupils you teach?

One of the most common approaches to developing academic vocabulary is to study morphology – breaking words down into their component parts and roots. It can support the development of academic vocabulary in subjects like science that are laden with technical vocabulary, as well as building a rich networks of new word families for use across the school curriculum.

It is an approach as ancient as the Greek and Latin societies that generated so many of the words that clothe our modern-day school curriculum. New research keeps adding to the picture that this is an approach teachers should consider as part of essential classroom practice.

A small recent US study on, ‘What’s in a word? Effects of morphologically rich vocabulary instruction on writing outcomes among elementary students’ (2022), revealed that young children who were taught with a morpheme focus to thier instruction made gains with spelling and understanding word meanings, though it was less effective when judging essay writing (a much bigger challenge, where word knowledge and choices may be compromised).

The second recent study on morphology teaching, entitled ‘Growth in written academic word use in response to morphology-focused supplemental instruction’ (2022), showed that for older primary school age US pupils, they developed an increase in academic word use across two terms when given morphology instruction compared to business as usual. Interestingly, pupils who struggled with literacy didn’t make as many gains – which should give us pause.

How often do the word rich get richer, no matter our attempts? It doesn’t rule out teaching vocabulary using morphology, but we should recognise that some pupils will still struggle to develop academic vocabulary and they need our additional supports to access the curriculum. Breaking words into their component parts can simplify the complex act of getting to grips with academic language, but trialling and testing it in the crucible of the classroom will matter.

What practical approaches can mobilise morphology teaching? Here are 4 Mighty Morpheme strategies:

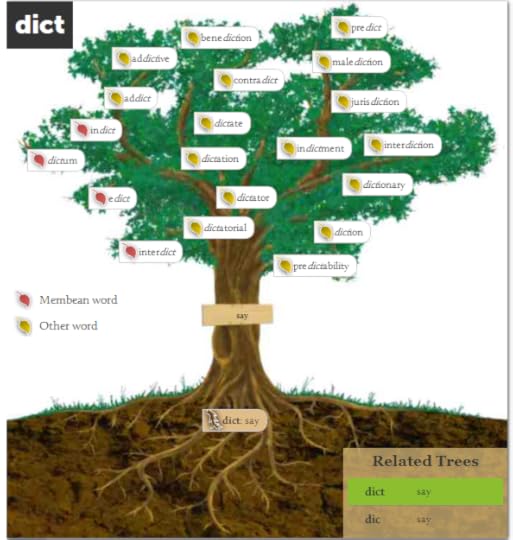

Root Races (or ‘Spelling sprints’). Pupils enjoy being exposed to new word roots and making a race for generating as many words from that root as possible. Take the root ‘Magni’, meaning ‘great’. We give pupils a minute or two to generate as many words as possible (individually or in groups). Think ‘magnificent’, ‘magnanimous’, ‘magnitude’ and ‘Magna Carta’. Then, after some counting of words, we can explore their connections and meanings and create rich academic word families.Word trees. A popular approach to exploring word families is to generate word trees. Websites like Membean.com do a great job of generating these, but it can be equally as good to generate them on a classroom display, or together as a class on the whiteboard (this can be planned, or spontaneous, if the pupils detect some meaningful morphology. Membean.comMaking morphemes visible. A lively way to generate ideas is to hold back on the word root, but to instead to share three images that are all represent words connected by their common roots. For instance, what do they follow three images represent?

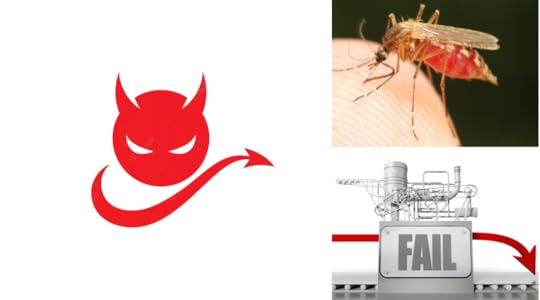

Membean.comMaking morphemes visible. A lively way to generate ideas is to hold back on the word root, but to instead to share three images that are all represent words connected by their common roots. For instance, what do they follow three images represent? ‘Mal’ – meaning ‘bad or evil’ – so, ‘malevolent’, ‘Malaria’ and ‘malfunction’

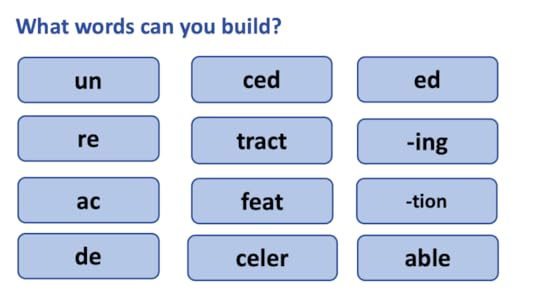

Word building. For the very youngest of children, all the way up to A level, we can develop vocabulary via word building. It has many variants, but the kernel of the approach it to select prefixes (e.g. ‘un’, ‘re’ or ‘exo’) along with word roots (e.g. ‘tract’, ‘feat’ etc.) and suffixes (‘ed’, ‘ing’ etc.) and encouraging word building. You can even have fun making up some nonsense words!

‘Mal’ – meaning ‘bad or evil’ – so, ‘malevolent’, ‘Malaria’ and ‘malfunction’

Word building. For the very youngest of children, all the way up to A level, we can develop vocabulary via word building. It has many variants, but the kernel of the approach it to select prefixes (e.g. ‘un’, ‘re’ or ‘exo’) along with word roots (e.g. ‘tract’, ‘feat’ etc.) and suffixes (‘ed’, ‘ing’ etc.) and encouraging word building. You can even have fun making up some nonsense words! Related reading:

Related reading:I have written before on the power of morphology for teaching academic vocabulary:

7 Strategies to Explore Unfamiliar Vocabulary. What is in a Word? Etymology for Every Teacher 5 Vocabulary teaching myths The post Teaching Vocabulary and Mighty Morphemes first appeared on The Confident Teacher.June 12, 2022

Write like the Romans

Apart from the sanitation, the medicine, wine, public order, roads, and public health, what have the Romans ever done for us?

Well, they taught us how best to teach writing.

Not a week goes by when new apps or AI isn’t promised as the answer to all our educational ills. But what if our contemporary literacy challenges are not all solved by the spells cast in Silicon Valley? We are often encouraged to look to the future for solutions, but perhaps they can be found by digging into our ancient past?

The Romans developed the first real systematic approach to teaching writing. It was explicit, carefully crafted, and still essential to how we now teach writing.

The greatest teacher to wear a togaPerhaps the most important teacher in recorded history taught in ancient Rome was Marcus Fabius Quintilianus – known more commonly as Quintilian.

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (Quintilian) – The British Musuem

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (Quintilian) – The British MusuemBorn around 35AD, Quintilian would move from the Rioja region of northern Spain to become a teacher in Rome who became celebrated by emperors and philosophers, parents and pupils. He was the most famous proponent of an explicit and systematic approach to teaching that would see youngsters in ancient Rome become brilliant orators and writers.

Quintilian’s views articulated in his books on rhetoric and writing are remarkably modern sounding. Notions that ancient teaching was merely teaching writing rules by rote are crushed by Quintilian, who argued that learning grammar rules outside of lots of rich models of great writing was like a ship drifting aimlessly without a captain.

He recognised that lots of reading and debating was essential to offer pupils the ‘abundance of the best words, phrases and figures’. Quintilian would teach with a tonne of practice of Roman rhetoric. There would be lots of imitation of good models, and lots and lots of effortful practice. On their wax tablets, pupils would have practised their rhetoric and their extended writing, before wiping it off and practising some more (‘Erasure‘ – the act of revising and editing your writing, was viewed as crucial by Quintilian).

Writing like the Romans would have been good enough for Shakespeare.

Hundreds of years later, the Bard would have been taught the ‘Progymnasmata’ that was promoted by Quintilian (it had its origins in Ancient Greece) This fourteen-step system of writing exercises would have likely begun with taking a model text, such as Aesop’s famous ‘Hare and the Tortoise’. Pupils would have copied the story, contracted it, added to it, played with sentences from it, created wise sayings in response to it, compared it, argued about it, and, of course, performed it aloud.

The 14 Progymnasmata writing exercises Fable. Pupils were given a fable (or similar) to abbreviate, amplify, or to create a similar fable of their own.Narrative. Pupils were given a factual or fictional story and had to retell it in their own words, with close attention to the facts (who did it? What was done? Etc.).Chreia (or Anecdote). Pupils were expected to write a brief anecdote that reports a saying, a moral action, or both (e.g. praising the action & comparing it).Proverb. Pupils took a common proverb and explained its meaning, giving examples and contrasts.Refutation. Pupils were trained to argue and to criticise an opposite view (e.g. attack the credibility of a legend like ‘The Tortoise and the Hare’).Confirmation. The opposite of Refutation, pupils had to prove a given view, such as arguing for the credibility of a given legend.Commonplace. Pupils would take a vice or a virtue and would amplify it by arguing for or against it, with examples and contrasts (e.g. criticising the sloth of the Hare).Enconmium. Celebratory writing about a person or thing (e.g. celebrating Aesop’s tortoise!)Vituperation. The opposite of an Enconmium – it is writing to criticise a person or thing (e.g. giving Aesop a hammering).Comparison. You can combine a celebration and a criticism, or praise two people by way of comparison (e.g. praising the tortoise, whilst pillorying the hare)Impersonation. Writing in the words of a person, real or imaginary, living or dead (e.g. taking on the mantle of Aesop himself commenting on his stories).Description. A full description of a person or thing.Thesis or theme. Exploring a balanced argument on a theme, often applied to moral or political questions.Defend / attack a law. Most English teachers are familiar with the age-old banning uniform argument and similar.(See this helpful online resource for the Progymnasmata HERE.)

What other approaches would have likely been promoted by the Romans to enrich writing?

Collect and remember (Roman) root words. Want to improve pupils’ writing? Enriching vocabulary is of course vital to improve writing. So, how do we make sophisticated vocabulary more memorable? We can help to build pupils’ vocabulary networks (or their vocabulary schema) by making meaningful connecting. Identifying root words – many of Roman origin – offer up memorable connections. There are lots of Roman Greek root word lists available (see HERE ). Take the root ‘ corp ‘, meaning body. How many words can you generate? Corpus (body of language), corpse (dead body), corpulent (a big body…or fat!)… what about corporation (to combine in one body)? Now, how about the root ‘ cardio/cor ‘ (think ‘cardiac‘, ‘cordial‘ and ‘courage‘) or ‘ carn ‘ (think ‘carnivore‘, ‘carnage‘ or ‘reincarnation‘).Sentence stacking. For younger writers in particular, crafting quality sentences would have proven common practice (like writing pithy proverbs). Sentence variation strategies would have been deployed to hone and overlearn the grammar moves that make for effective writing (using ample modelling). With ‘sentence stacking’, you simply take a single sentence and encourage pupils to vary the same sentence (perhaps add a word, omit a word, edit a phrase, shifting the style). You can then stack the variations together and discuss their effects and effectiveness.‘Write it, read it, say it, revise it‘. It is all-too-human to rush writing and make errors and not meet our aims. For novice writers, we must slow them down and encourage revisions that consider accuracy and audience. Quintilian focused on ‘erasure’ (Roman pupils would wipe their wax slate clear) and the meaningful repetition of reading written drafts aloud. The simple active ingredient of slowing pupils down, reading writing aloud, talking about it, and providing purposeful repetition and revision is likely of value. Lots of purposeful modelling of writing was promoted by Quintilian long before Visualisers were ever imagined.Lots of these approaches are familiar of course – in English, but also in history, religious education, and across the curriculum in lots of subtle ways. Not only that, as busy teachers grapple with the complex task of teaching writing, I think there is something profoundly reassuring in children today learning to write just like their ancient peers!

Thousands of years after Quintilian, scientific research on writing and the brain would go to prove that this explicit, step-by-step approach to writing, with lots of effortful practice, would be essential for writing success.

If we want to improve pupils’ writing, we should consider how they can write like the Romans.

Related reading: There are lots of brilliant advocates of learning Latin and schools can access funding, support and resources from organisations such as ‘ Classics for All ‘, ‘ Classics for All North ‘ and ‘ The Classical Association ‘. There are countless useful available online like this web article from ThoughtCo. – HERE . You can read more about the history of writing (and the teaching of it) in chapter 2 of ‘Closing the Writing Gap‘!The post Write like the Romans first appeared on The Confident Teacher.June 5, 2022

Leading Literacy… And Communicating Complexity

This short blog series is targeted at literacy leaders – either Literacy Coordinators, Reading Leads, or Curriculum Deputies – with a key role in leading literacy to ensure that pupils access the curriculum and succeed in meeting the academic demands of school.

Few school leaders get trained in communications. Yet, in almost all facets of school leadership, savvy communication is necessary. From sensitively worded emails to colleagues, school website page updates, job adverts, to the many communications with parents. When you are tasked with leading an area like literacy, you are forced to consider an array of tricky communication choices to elicit support for successful change.

It is helpful to consider leading literacy like a successful political campaign. You need a compelling strategy, clear messaging about any changes, and a solid story to convince busy teachers to buy into your plans. Easy, eh?

We can distil such communications into principles to navigating communicating complexity well.

5 Principles of communicating complexity1. People follow people and their stories over policy documents. A literacy leader is often tasked to write purposeful policies about literacy practices, such as approaches to SPaG, whole school reading, and more. The problem is that teachers are too busy to read them anyway. Given that we privilege stories psychologically, we should work hard to identify a small number of concrete stories that convince teachers why a change is necessary, alongside characterising that change. Some of my most memorable professional development involved the video of struggling pupils from my school explaining what support strategies helped them most. It was people and their stories that instigated my habit changes – not the small print in a literacy policy.

2. Little and often is vital for busy teachers. There has been an entire industry built on behaviour insights and how to adapt your communications for a busy audience (see the BIT team and their excellent EAST Framework). We see it in education. Texts to parents approve to prove accessible for parents, so why wouldn’t the same principles of regular nudges work for teachers? Some of the most effective school approaches I have seen recently offer regular emails nudges, with positive reminders by slotting in good practice into weekly slots that work with the rhythm of the school week.

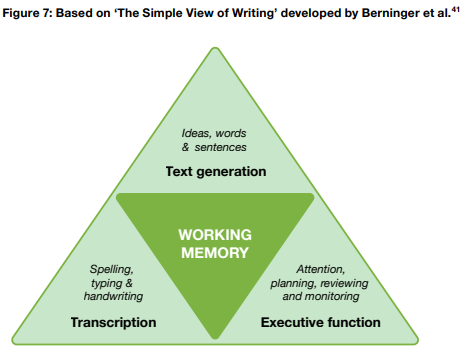

3. Short and sweet – like a text or a tweet. Not only are teachers busy, but their day is so chock-full of decison-making and an array of practices, that they understandably find it hard to translate complex insights into concrete actions. Helpfully, literacy does include accessible models, such as the ‘Simple View of Reading‘, the ‘Reading Comprehension House‘, the ‘Simple View of Writing‘ etc. By shrinking insights down to a working model, you then offer a hook upon which some practices can hang. For instance, with the ‘Simple View of Writing‘, you can more easily cluster practices to improve pupils’ writing. The next ‘short and sweet’ step has to be selecting a small number of actionable practices than can be implemented well (doing even few things well may just be at the edge of manageable for professionals with limited bandwidth).

from the ‘Improving Literacy at Secondary School’ EEF Guidance Report

from the ‘Improving Literacy at Secondary School’ EEF Guidance Report

4. Over-communicate, over-communicate, over-communicate. There is an adage that when you give a talk on a topic for the hundredth time – feeling the message is worn and tired – someone is hearing the message for the first time. Plan to communicate your literacy strategy… and bake in repeating that communication. For instance, communicating about how to develop whole class reading may get tuned out of deleted emails, not quite make the agenda in meetings, and be forgotten as it is relayed in the far reaches of a CPD twilight. Over-communicating your literacy messages, replaying that central story, can be done if you have distilled insights into those ‘short and sweet’ messages that are so vital for any working literacy strategy.

5. Pay attention to multiple audiences. It takes a village to raise a child; it takes a school community to enact a literacy strategy. It may be that approaches to reading or writing are communicated and practised with teachers, but if we are to clearly and concisely mediate similar messages to both pupils and parents, we can create a positive alignment. Sometimes it take a little reciprocal pressure, knowing everyone else knows about the literacy focus, for it to be sustained when everyone is tired, busy and reverting to old habits. Consider how to calibrate the message to different audiences with very different levels of expertise (remember to get the timing right for time-poor parents), but do consider over-communicating to all audiences with those vital literacy strategy developments.

We can have the best literacy strategy, with a polished 10-page policy, but all too easily it can get lost in the hubbub of a busy school term. Careful, well-crafted communication planning is essential to ensure that plans are picked up by everyone in school.

Read the rest of the series:

Leading Literacy…And Influencing Teachers

Leading Literacy…And Purposeful Professional Development

Leading Literacy…And Communicating Complexity

Leading Literacy…And Evaluating Impact

May 28, 2022

The Grammar Gap

There are few topics in education – indeed, English life – that inspire fear, loathing and unfulfilled expectations quite like the subject of grammar.

Researchers are quick to challenge notions of ‘standard English’ and how grammar is being taught in primary school, or the tyranny of tests. Sadly, amidst these loud debates, too many teachers muddle along quietly and with little confidence about how to teach grammar to improve pupils’ writing.

My own ‘grammar gap’ began in school and extended to my teacher training (being trained to teach the English language no less). The harsh baptism of teaching A level English meant that I had to teach myself grammar. I was spectacularly undertrained to support struggling writers. What chance a busy religious education teacher largely untrained in the many ‘moves’ of academic writing?

Almost universally, teachers lack confidence in teaching grammar and explaining the effects of grammatical choices. With a little support, we could improve annotations in art, essays in history, arguments in RE, experiment write-ups in science, and much more. Even when teachers have a good knowledge of grammar, they can lack confidence in teaching it. It is a frustrating tale of innumerable missed opportunities.

We are left asking: are teachers in both primary and secondary schools suffering from a crippling lack of confidence when it comes to teaching grammar?

A very short history of grammar teachingCriticisms attending grammar teaching come from all angles. The more formal teaching of grammar has its roots in early grammar schools, centuries ago. At regular intervals since, grammar teaching has been routinely criticised as an ineffectual ‘confining cage’ that produces ‘square cucumbers’ and not skilled writers.

Back in the 1960s, when grammar teaching plummeted out of fashion, it was challenged and described as having a ‘harmful effect on the improvement of writing’ and simply being a waste of time.

After some decades in the wilderness, more formal grammar testing has seen a slow renaissance. In 2013, the new year 6 grammar test (the EGPS – English Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling) was created and how to teach and test grammar, and pupils’ writing, has again lurched back into the limelight.

Arguments about ‘correct grammar’ and fierce arguments about the relevance of ‘fronted adverbials’ have generated lots of heat and headlines, but too little light and guidance for busy teachers grappling with their own grammar gap.

Closing the gap…And the ‘Top 10 Grammar Moves for Academic Writing’The real problem with the teaching of grammar is not a single test with a few debatable terms, but instead the dearth of support offered to teachers, so that they can teach grammar effectively and consistently, across both primary and secondary schools.

When teachers are supported to have a more confident understanding of grammar – with meaningful and well- targeted terminology – we can in turn help pupils to better notice, describe, and practise the moves of successful writers.

For example, noticing how a writer uses adverbs for explanations in food and nutrition can lead to meaningful practice in writing fitting instructions for preparing food (should they stir ‘quickly’ or ‘slowly’?). Additionally, in music, Italianate adverbs like adagio and pianissimo offer precise instructions on how to play an instrument.

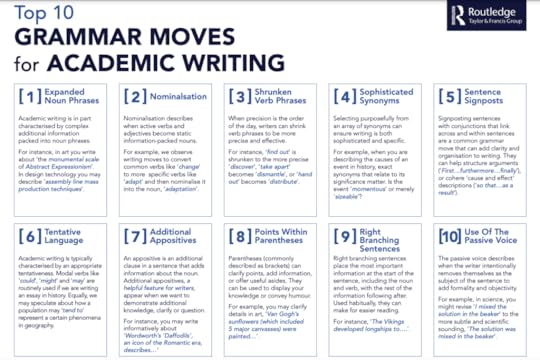

We can help teachers by identifying the common grammar moves for academic writing. My ‘Top 10 Grammar Moves for Academic Writing‘ (download it free from my RESOURCES page HERE). is a starting point for supporting teachers to teach grammar meaningfully to improve pupils’ writing:

For teachers, parents, and even grammar pedants, such terminology shouldn’t simply trigger arguments, they should be the start of a discussion about how to teach grammar and writing with success. We can then work on how to integrate teaching these moves in ways that a sensitive to pupils’ writing development and the subject specific academic writing (the ‘passive voice’ in science; ‘tentative language’ in history; ‘additional appositives’ in art; shrunken verb phrases in geography in art, and much more) that becomes so key to exam success and much more.

With sustained training and support, we can help every teacher to close the grammar gap in their classroom, as well as attend to their own.

Read the book! If you are interested in reading about teaching grammar and much more, you can buy my new bestselling book:

Amazon UK: HERE.

Routledge: HERE. (Use CWG20 for a 20% discount)

The post The Grammar Gap first appeared on The Confident Teacher.May 22, 2022

Closing the Writing Gap – New Resources

It is crucial that busy teachers are supported with timely and accessible resources to support their work. As a result, to go alongside my new book, ‘Closing the Writing Gap’, I have produced a small number of tools that I hope will help translate the insights from the book into action.

The free resources include:

7 Steps to Close the Writing Gap. This simple infographic offers a basic summary of the key steps to improve writing that feature throughout the book.

Prioritisation activity. This is a simple summary of comment writing priorities that feature in all school types. The resource can be used as a prompt for discuss and purposeful prioritisation.

Top 10 grammar moves. This infographic summarises the key grammar moves that feature in academic writing.

Teaching sentence variation. This resource concisely summarises the four key types of sentence level moves that pupils can practise to develop their writing style.

Modelling writing approaches. This resource summarises different approaches to modelling writing, including potential benefits and limitations.

You can freely download all of these tools on my updated Resources Page – HERE.

If you want to read the book, you can pick up a copy now:

Amazon UK: HERE.

Routledge: HERE. (Use CWG20 for a 20% discount)

The post Closing the Writing Gap – New Resources first appeared on The Confident Teacher.May 17, 2022

Introducing… Closing the Writing Gap

Writing a book about teaching writing is a daunting prospect. Sharing the reality that I spent years in the classroom struggling to support weaker writers only adds to the trepidation. What if my teacher knowledge gap wasn’t the norm? What if my attempts to translate practical strategies fell flat?

I was delighted and relieved then to receive really positive commendations from a brilliant array or teachers, leaders, and research experts. You can read their quotes below:

“‘Our lives can be filled and fulfilled by writing,’ says Alex Quigley. In this important new book: ‘That story begins with our birth certificate and ends with our epitaph …’. I can’t think of a text which better articulates the importance of writing, and then goes on to articulate how to put ambition into practice. It is a book of wise principles and practical implementation. In it, Quigley establishes himself even further as my go-to source of insights into the all-important subject of whole-school literacy.”

Geoff Barton, General Secretary, Association of School and College Leaders, and former English teacher

“This book provides an easy-to-read and entertaining synthesis of research on writing, beginning with a compelling overview of how writing developed. It has written text at its heart and offers readers a succinct insight into textual research and its practical application to the writing class- room. The book is a rich source of directions for further reading and examples of strategies for teaching writing which will support teachers to reflect on what happens in their writing classrooms and to make enabling changes.”

Professor Debra Myhill, Director of the Centre for Research in Writing, University of Exeter, UK

“Alex Quigley has written another brilliant book for classroom teachers and school leaders. This book gets right to the heart of closing the writing gap; it is thought provoking for the reflective teacher whilst also offering helpful guidance and advice for every teacher. Alex is an exceptional writer himself, communicating his expertise and experiences with clarity and precision.”

Kate Jones, History teacher, education consultant, author, and blogger @KateJones_Teach

“As this important and necessary book makes clear, many teachers struggle with the teaching of writing. Teachers recognise the huge significance of writing, but they find it difficult to translate their own writing expertise for the benefit of their students. In Closing the Writing Gap Alex Quigley provides evidence-informed, highly practical strategies to bridge this pedagogical chasm. Both erudite and accessible, it covers the vital ingredients of effective writing teaching – from the building blocks of the grammar to the art of rhetoric and the pragmatics of the drafting and editing process. Closing the Writing Gap is an essential addition to the bookshelves of all teachers.”

Mark Roberts, English teacher and author of The Boy Question

“Closing the Writing Gap is the perfect antidote to the problems surrounding writing in the classroom today. Alex Quigley’s razor-sharp focus pinpoints the clear ways teachers can address and improve writing in the classroom. The book’s real strength, for me, is its practical approach to writing, offering strategies and methods that all teachers could, and should, use in the classroom. Alex walks you through the various aspects of writing and provides a brilliant insight into how practitioners can support and improve writing in their classroom today. The book to read if you want to improve disciplinary literacy in a school.”

Chris Curtis, Head of English and author of How to Teach English

I hope the commendations ring true for teachers who pick up this book. It is a book for teachers and school leaders, those who train or work with teachers, or who are simply interested in how writing can be taught well.

If you want to read the book, you can pick up a copy now:

Amazon UK: HERE.

Routledge: HERE. (Use CWG20 for a 20% discount)

The post Introducing… Closing the Writing Gap first appeared on The Confident Teacher.May 7, 2022

Leading Literacy… And Purposeful Professional Development

This short blog series is targeted at literacy leaders – either Literacy Coordinators, Reading Leads, or Curriculum Deputies – with a key role in leading literacy to ensure that pupils access the curriculum and succeed in meeting the academic demands of school.

Picture the scene: it is the first school day of the new year and staff are shuffling in their seats. In the absence of their pupils, teachers eagerly await the opportunity to get back to their classroom or office to plan their upcoming week.

Amidst the chatter, the literacy lead stands up, shaking off the new-school-year nerves. They have an entire fifteen minutes to re-inspire and re-instigate important approaches to whole school reading.

What are their chances of success?

Professional development and developing literacySchools have lots of competing priorities for improvement. Teaching approaches, assessment, and curriculum development, all understandably receive most of the current bandwidth of precious professional development time.

Literacy can sometimes proves to be the topic ‘we do already’, lacking the novelty value to grab attention. It is unsurprising then that literacy, if perceived as a bolt-on to ‘covering the curriculum’, gains the professional development slots that are decidedly after the Lord Mayor’s Show.

Any leader of literacy therefore needs to ensure that they convince colleagues that literacy is not an add-on, but is in the fact the access point to the taught curriculum. If the case can be well made that literacy should be the focus of school improvement, then a proposal to develop literacy is almost guaranteed to require some high-quality professional development for teachers.

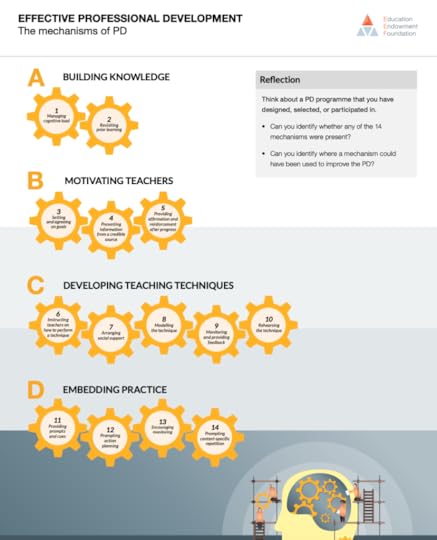

The recent EEF guidance report on ‘Effective Professional Development’ offers a helpful starting point to consider the ‘how’ for a well-structured and sustained approach to literacy professional development.

There are so many potential places to start when it comes to literacy priorities. You could pick from a plethora of purposeful starting points: developing pupils’ vocabulary; enhancing pupils’ reading fluency; cohering a reading rich curriculum; improving pupils’ extended writing; teaching pupils how to write in a formal academic style; introducing ‘disciplinary literacy’; a renewed focus on implementing phonics; supporting high need pupils who struggle with reading; and much more. [See this blog for helpful sources and resources for literacy priorities]

First, it is vital when leading literacy to shrink the challenge. You can identify one priority, before considering a suitable sequence. For instance, if you wanted to improve reading across the span of a school year in secondary school, you might want to sequence it to ‘understanding reading challenges’ > ‘reading fluency’ > ‘reading and background knowledge’ > ‘reading strategies’ etc.

The guidance is helpful in that it helps literacy leaders to think hard about the ‘mechanisms’ (that is to say, the core building blocks of professional development). It presents an accessible ‘balanced design’ that offers a scaffold for structuring PD:

Effective Professional Development: The Mechanisms of PD Poster

Effective Professional Development: The Mechanisms of PD PosterLet’s explore each of the four areas of the ‘balanced design’ model with a focus on literacy and reading development.

A balanced design for literacy PDA: Build knowledge (reduce cognitive load; revisit prior learning)

A helpful way to reduce cognitive load when it comes to understanding reading comprehension and reading barriers is to begin with an understandable model, such as the Simple View of Reading. A further example is to select multiple examples of curriculum texts, to reflect closely upon their respective difficulty, barriers and support factors.

When it comes to revisit prior learning, we can too easily ignore that teachers need helpful reminders of previous PD sessions. We use cumulative quizzes for teaching pupils, but these approaches can be just as useful for professional adults.

Revisiting prior learning is of course much easier if the sequence for the PD sessions of the year have been considered beforehand. Though difficult, it is likely the last session of the year needs to be clearly outlined before the first session is undertaken. In short, teacher PD across a year should be as considered and connected as a skilful curriculum plan.

B: Motivate staff (set & agree goals; use credible sources; affirmation & reinforcement)

We can be motivated to address literacy in their classroom, with the best intentions, but then school happens, and we defer to our habits. Decisions that attend reading can impact on fifty different teaching practices, so it can also blur and without clear goals we change very little.

It is not enough to have a really interesting PD session. Like any human, we need affirmation, nudges, reminders, and supports if we are to sustain a new habit or two. For instance, we may film pupils discussing what reading approaches have proven effective for them and how their increased fluency has made the curriculum more accessible.

C: Develop teaching techniques (perform techniques; practical support e.g. coaching; feedback; rehearsal opportunities)

I have been guilty in the past of doing training on a complex concept, but not spending enough time sharing and encouraging practise of apt teaching techniques that solve real classroom problems (that are sensitive to subject and even phase differences). Theory and interesting insights into models like ‘cognitive load’ will not be enough. Teachers need concrete practical approaches, along with some time to practice and rehearse them out of the white heat of the classroom.

When it comes to reading, there are countless ways to mediate tricky curriculum reading. As such you may narrow it down a PD focus to four strategies for developing reading fluency (see this excellent blog by Sarah Green on reading fluency). Rehearsing them in the training session itself is likely necessary. Helpfully, teachers and TAs can grapple with reading fluency if we practise with some unfamiliar foreign language or similar.

D: Embed Practice (prompts & cues; prompting action planning; self-monitoring; prompts for context-specific repetition)

Perhaps the hardest trick of all when it comes to literacy professional development – or on any topic or subject – is to sustain the habits and practices that were shared in training.

Too few PD structures offer supporting prompts to embed manageable and meaningful reflection when it comes to literacy practices. Maybe it is reciprocal teacher observations of parts of lessons, or the sharing of short videos of practice. Too little time is of course a barrier, which is why any PD programme needs to bake in these mechanisms and privilege them as much as any preparation for a new year PD session with all staff present.

P24, Effective Professional Development Guidance Report

P24, Effective Professional Development Guidance ReportRead the series:

Part 1: ‘Leading Literacy… And Perennial Problems’

Part 2: Leading Literacy…And Influencing Teachers

Part 3: Leading Literacy…And Purposeful Professional Development

Part 4: Leading Literacy…And Communicating Complexity

Part 5: Leading Literact…And Evaluating Impact

Alex Quigley's Blog

- Alex Quigley's profile

- 12 followers