Alex Quigley's Blog, page 2

October 4, 2025

Supporting struggling writers

The saying goes that what gets assessed gets taught. But for teachers, when it comes to the act of writing to learn, that is not always true. Students can spend thousands of hours writing in the classroom, but if they struggle with writing it can still remain unaddressed.

Why is writing the poor sibling to reading? And why can it remain a hidden problem for secondary school-age students?

There is an emerging recognition in primary schools that the foundations of successful writing, such as spelling and handwriting, may need more attention. It is patently obvious where children struggle with the basics as well as the ‘big game’ of writing.

There is a helpful policy direction of travel to support those who struggle with writing too. OFSTED’s new Toolkit identifies “foundational knowledge” such as “accurate spelling” and “legible and fluent handwriting”. The new DfE Writing Framework similarly identifies the same “foundational concepts in English”.

Move forward a few years and supporting students who struggle with writing gets murkier. Any student who sits their GCSEs has a battery of exams that are all mediated by writing skill. And yet, if you ask a geography teacher or a science teacher about handwriting fluency, and its potential impact on outcomes, they’ll likely be nonplussed.

How many words can your teen students write in a minute? What is the impact of dysfluent handwriting? How does weak spelling knock on to the types of academic words students use in their writing? These questions invariably go unanswered.

Why students may struggle to writeAsk teachers to identify struggling readers and they may start with talking about reading ages and standardised reading assessments. For writing, there is too little equivalent assessments to identify those students who struggle.

We should then identify the big problem areas where and why students are likely to struggle and fall behind their peers:

Troubles with transcription. Handwriting fluency, just like reading fluency, is vital to help students think and write effectively. (Read this on ‘ Developing handwriting ’). Spelling is just as foundational. Accurate fluent spelling unlocks language for writers, helping them be more ambitious in their vocabulary and cleaner in their expression. Insecure sentence composition. The sentence is the kernel of all writing. We can expand them, combine them, shrink them, signpost them, play with them, or break the rules with them. But if a strong sentence of sentence composition is not secure, students ideas become unclear, and their creativity is stunted. (Read this on ‘ Crafting great sentences ’). Getting lost in the writing process. The writing process is complex and multifaceted. You may plan, draft, editing, replan, revise, rewrite, and edit once more before publishing. Without careful scaffolding, students flounder and fail with various steps in the process. (Read this on the ‘ Challenge of Editing Writing ’). The writing game shifts in every subject. As students mature, writing gets more subject specific. Expectations in science, history and English, shift and move. Words and sentence structures are expected in one subject, then mean something else in another. It is enough to catch out any student. They may overwrite in science, annotate poorly in art, write with style in English, or without evidence in history. If you’re struggling with spelling, this subject level stuff feels out of reach. Writing requires ample reading. Students don't read habitually like they used to. Extended reading can also get a raw deal by an overfull curriculum in many areas. As a result, the many reading miles needed to generate knowledge, ideas, and language moves for writing don’t get enacted. Teachers end up over-scaffolding to compensate for a lack of reading. Writing can lack purpose, ideas, and the subtle genre or language features that are revealed by extensive reading.Is it any surprise that post-Covid writing outcomes have been worst impacted in English primary schools – below both maths and reading? Pre-pandemic results of 78% reaching the expected standard have plummeted to 71 and 72% more recently.

Are the brilliant opportunities gifted to students by their ability to write accurately, skilfully and creatively being lost?

We need to focus on supporting teachers to better identify students who struggle with writing – particularly, but not exclusively, teen writers in secondary school. We need more focus on assessment – both standardised and formative assessment.

Spying an issue with handwriting can be aided by formative assessments, such as the handwriting legibility scale. This can lead to a more standardised assessment, like the DASH assessment. Knowing how many words per minute your students can write is a start.

With better information, along with targeted training, we can play back to teachers the developmental practice that builds strong foundations for writing.

We can tackle the five key problem areas if we make them a clear school improvement priority, aligning them with reading approaches in focused and creative ways. But we must also confront the reality that likely over a third of students struggle with writing. Unless we address this head-on, many will continue to fall behind, and their chances of wider school success will be compromised.

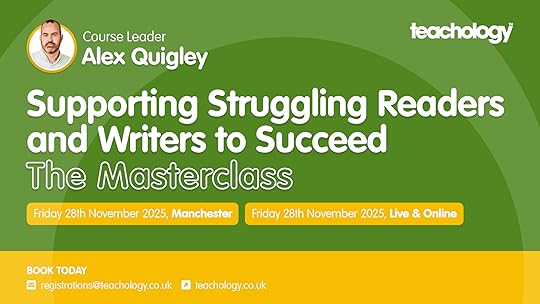

I am holding a unique Teachology Masterclass on 'Supporting Struggling Readers and Writers to Succeed'. It will be held LIVE in Manchester (and online) on November 28th. READ MORE DETAILS HERE.

September 20, 2025

The 3Rs - Reading, writing, and research to be interested in #69

Great teaching and targeted academic support

High quality teaching - each day and each hour - is likely to prove the greatest lever for securing success in education. Not only that, but it is likely to be disproportionately beneficial to pupils who struggle and have additional learning needs.

So far, so obvious.

In the new OFSTED Toolkit, its definition of inclusion states the importance of focusing on high-quality teaching straightforwardly:

"Leaders understand that the most effective inclusion strategy begins with everyday high-quality inclusive teaching, which has most benefit for the pupils who find learning hardest and reduces the need for individual adaptations." OFSTED, State-funded School Inspection Toolkit (2025)

It is welcome that the central importance of high quality teaching is so well established. This wasn't always the case.

Back in 2011, the UK coalition government initiated the Pupil Premium policy to 'raise the attainment of disadvantaged pupils and close the gap between them and their peers'. When this funding was initiated, the quality of teaching seemed to take a back seat, and a focus on sending pupils out of class for additional interventions was a dominant assumption for how to address barriers to learning.

Over time, the instinct for an extra 'fix' was corrected by a re-emphasis on the power of high quality teaching. Indeed, targeted additional supports started to be viewed sceptically. In 2018, Tom Sherrington wrote:

"At some point ‘intervention’ really has to be simply ‘teaching’. Given all the variables, uncertainties and unknowns, rather than chasing interventions, it is a far far better bet to focus on teaching everyone better." 'To Address Underachieving Groups, Teach Everyone Better'

Across a similar time-period, the boom in cognitive science, Rosenshine's principles and more, signalled a concerted focus on teaching methods alongside curriculum planning. High quality teaching synced with curriculum dominated edu-conversations.

Notions of 'intervention' were so varied, with many interventions being sold to schools with little good evidence, as to provoke healthy questions in some quarters. Practices such as taking pupils out of English lessons to do literacy interventions understandably aroused suspicions about effectiveness.

Guidance to support children from disadvantaged backgrounds

The Education Endowment Foundation's 'Guide to the Pupil Premium' shared guidance with schools since near the beginning of the 2011 government policy. Since its inception, the EEF have used the tiered approach model to help school leaders consider their pupil premium strategy. For example, in the newest guidance, it states:

"High quality teaching should be a top priority for Pupil Premium spending. Making sure an effective teacher is in front of every class, and that every teacher is supported to keep improving, is key.

Targeted academic support can have a strong positive impact on learning, and is an important part of any Pupil Premium strategy.

Wider barriers to learning are important to consider as part of your Pupil Premium strategy. While many challenges may be common between schools, the specific features of the community your school serves will affect which approaches you prioritise in this category."

See the latest ' EEF Guide to the Pupil Premium '

Often, however, the connections between high quality teaching and targeted academic support are not clear enough. In this gap, impact weakens and pupils' progress can suffer.

Pupils who are struggling can benefit from more intensive practice offered by high-quality targeted academic support. For pupils struggling to access the maths curriculum, for example, targeted academic support is often a focus on interventions that are intensive versions of high quality maths teaching. In approaches like maths tutoring, students should receive more explicitness of instruction, more feedback, and more practice of maths, along with more systematic reviews of progress.

Clearly, if the targeted academic support is to be maximised, it needs to sync with the approaches undertaken in the classroom daily by teachers. It is why the evidence for the effectiveness of tutoring is greater when it is "aligned" with teaching (be that scheduling, content, teaching strategies, and more).

Additional targeted academic support is essential for someIt is no doubt a good thing to focus on improving teaching. But we should chase interventions that amplify and align with high quality teaching. For some children with additional barriers to learning, this will be essential if they are to narrow the achievement gap with their peers.

Take David, who is a pupil in year 5 who struggles with reading, and who happens to be from a disadvantaged background.

David's struggling need to be explored and diagnosed with clarity before seeking out an intervention, or assuming a deficit caused by his background. Perhaps David has lacked access to wider reading from a young age, or has experienced language delays that disrupted early reading, or struggles to decode, or he has lacked confidence reading aloud, or has significant gaps in word knowledge, or who lacks background knowledge when reading informational texts... Even more likely, David exhibits a tricky combination of issues.

Diagnosing David' needs with effective assessment is vital and it is a key tenet of inclusive practice.

Targeted academic support should be a big help and prove necessary in addition, and in alignment with, high quality teaching. Both need to be based on good assessment.

If assessment reveals that David has issues with word reading, he is likely to benefit with intensive additional support with decoding and vocabulary instruction. He may have significant challenges with a lack of background knowledge and vocabulary from which to comprehend a text, so a different targeted intervention may help intensify his exposure to crucial 'book language' and help his develop knowledge similar to that of his strong-reader peers.

Throughout the school day, David is likely to benefit from high quality exposure to oral language. Lots of book talk, and lots of wider reading, lots of knowledge building, and reading strategies to unpick a rich diet of texts across the curriculum. High quality teaching will make a difference, but David will need additional targeted practice in relation to his peers.

Intensive, explicit practice posed by additional interventions can help narrow the attainment gap for David.

For example, the school may select 'Reciprocal Reading' to give David vital additional exposure to reading instruction and practice. The success of 'Reciprocal Reading' is that is offers intensive reading practice and exposure to book language. It models and scaffolds the strategies that David' strong-reader peers seem to exhibit more 'naturally', such as clarifying language they don't know, or questioning and summarising the text. Effectively it is a model for intensive, high quality book talk.

The impact of such an intervention will wash away if David doesn't continue to experience a rich reading diet through the curriculum, or his teachers don't get David to consolidate his understanding with lots and lots of high-quality book talk.

A school can maximise reading development for David if it aligns how reading is taught whole class, with the core components of what is taught in additional interventions. It is not a case of chasing fixes, but careful leadership planning and alignment.

The 'targeted' aspect of the reading approach is key here but often missed. Doing 10 more minutes silent reading in the morning could be handy, but it likely won't be targeted with explicit instruction and personalised feedback. Doing a cluster of revision lessons in year 11 with 20 pupils with 20 different reasons for underperformance is not targeted.

As the education system in England embarks on a new phase of understanding what inclusion means, and how high quality teaching can best support pupils, it is valuable to pause and consider how teaching and additional supports interact. How do we solve widespread issues with reading ability in key stage 3 with 'both...and' solutions?

The tiered model from the EEF for the Pupil Premium strategy encompasses a focus on high quality teaching, alongside aligned targeted support (interventions), and work on wider strategies (such as tackling attendance or strengthening parental engagement). It does offer a handy shortcut to consider all school improvement and inclusive practices.

High quality teaching should remain top of the agenda. Though it is vital to recognise that for some pupils it will not offer the volume of necessary practice posed by targeted academic support. Evidence-based interventions can prove essential and complementary to great teaching.

The challenge is therefore not choosing between great teaching and great targeted support. It is bringing them together. That way, pupils like David have the best chance to keep up with their peers, catch up where necessary, and ultimately go on to thrive and excel.

September 13, 2025

Adaptive teaching: Stretch and challenge

"A precocious child," Miss Honey said, "is one that shows amazing intelligence early on. You are an unbelievably precocious child.”

"Am I really?" Matilda asked.

Adaptive teaching is usually discussed as a responsive approach to teaching students who routinely struggle. It describes how teachers can anticipate, assess and adapt, so that all students access the curriculum.

However, the more you consider the diversity of classrooms, the more you consider adaptive teaching can also help focus on stretching students who can find learning easy, or who get bored by a task that isn’t challenging for them.

Stretching and challenging Matilda

A focus on ‘gifted and talented’ has largely faded into the background of national policy. Understandably, there is a greater focus on inclusion, pupils with SEND and those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Perhaps the implicit assumption is that children like Matilda, who prove precocious and academic throughout their education, are going to be just fine. In the race that is school success, they are speedy and seemingly have all the natural tools to win.

But when you consider the children that sit in a primary school class, like Matilda, or students in a GCSE maths class, they have their own needs and challenges that we should seek to meet.

Too often, for high prior attaining students, the default can be to give them additional tasks. If we are not careful, keeping highly capable students busy becomes a proxy for stretch and challenge when it isn’t. It smacks of some of the old approaches to differentiation, when we give an extension task with a couple more questions, but the bulk of the lesson isn’t challenging or stretching all students.

“Adaptive teaching is less likely to be valuable if it causes the teacher to artificially create distinct tasks for different groups of pupils or to set lower expectations for particular pupils.”

Early Career Framework, Standard 5 – Adapt Teaching

Stretch and challenge should not be deemed an extra task because you finished quickly. Nor should stretch and challenge be rationed out to the few students who are deemed ‘gifted and talented’ based on a test score or two from the previous year.

Adaptive teaching and challenging Matilda (along with everyone else)

Adaptive teaching can include lots of small microadaptations that make children like Matilda think harder, understand more critical reasoning, and exhibit greater independence.

For instance, for a year 4 teacher who is checking for understanding of the rainforest biome by getting children to answer quiz questions, can ask Matilda for a ‘Just a Minute’ explanation of ‘why rainforests are important for our planet’, along with recall of layers of the rainforest, plants and animals.

By stretching Matilda and expecting her to verbally reason, we then offer the start of a potentially powerful dialogue with the rest of the class (using the ABC feedback model):

‘Adil, do you Agree with Matilda?’

‘Freya – I think you might want to Build upon those threats to the rainforest that Matilda mentioned.’

In a year 8 history classroom, you can create a climate whereat students expect to tackle difficult tasks. You can take a school trip to visit a Norman Castle and it can be interesting and fun. But you can ensure it stretches and challenges too.

I love this example from Richard Kennett of a school trip that is framed by a debatable enquiry question (‘What was the purpose of Norman Castles?’) that combines historical scholarship along with sword buying and castle climbing! Small adaptations, such as answering the enquiry question at the end of the day, can enhance motivation whilst also increasing the degree of challenge. Matilda is likely to love it, but every student, regardless of their starting point, is scaffolded to succeed.

If a student like Matilda flies through their maths homework at lightning speed, a microadaptation can be to write (or record) a short ‘Debrief’ (see a detailed blog HERE) about the strategy they used, or even devise a problem of their own for peers to solve. Then when students share their strategies, we encourage reflection and the critical reasoning that stretches every student.

Sometimes students can read more, write more, independently explore topics of interest. But we should consider how small adaptations to every task in the classroom ensures it challenges thinking, not just keeps students busy. We can ensure high prior attainers are not bored, or go unchallenged, as much as we rightly focus on supporting struggling students not to fall behind their peers.

Related reading: See my ‘adaptive teaching’ collection of blogs and links HERE.

August 30, 2025

August 29, 2025

The oversimplification trap

Are we in danger of making learning too simple?

When it comes to students in the classroom, we can simplify an explanation of a concept into PPT where complex phrases become glossy icons. Books can become short booklets. Subjects become revision guides.

Tricky topics can get distilled into knowledge organisers without students actually engaging in the hard thinking necessary to produce such a distillation.

There are obvious reasons for distilling complexity into something more palatable for students, however, there are attendant dangers too.

The concept of 'deliberate difficulty' has always struck me as integral to what good teachers do. A teacher may have students grapple with word problem in maths without quickly posing the most effective solution. Students may sometimes have to linger with the ambiguity of a poem in English before the symbolism is explained to them in plain terms. In doing so, they think harder which can elicit more learning.

For example, I am a big advocate of vocabulary instruction to unlock the complexity of a topic as an entry point that reduces the initial difficulty. But teaching vocabulary and eliciting curiosity and interest is valuable, but teaching key words should not be a substitute for actually reading or going on to grapple with difficult concepts.

We know that students can have their attention robbed by the easy scrolling on screens. The experience of TikTok videos or short, simple messaging that makes up our students' world is quick and designed to be easy. But most learning is the opposite. It is usually difficult and it elicits struggle and hard thinking (or it should).

A common misconception I detect when I talk about 'cognitive load theory' is that it is fundamentally a message to make learning easier. The more subtle reality it conveys is that we need to make learning difficult, but not too difficult. It is about the tricky management of difficulty that defines successful teaching and learning.

Tesler's law (also known as the 'Law of conservation of complexity') describes how for any given task, there is a certain amount of complexity that cannot be removed or eliminated. Instead, we simply shift the complexity somewhere else. This law is instruction for learning complex knowledge and skills.

Take the example of the aforementioned knowledge organiser as a learning tool. For many students, it distils just enough difficulty so that they can learn and succeed. But it also shifts the complexity students need to know just out of sight.

You don't need to read too much extended texts about photosynthesis or 'A Christmas Carol' if you can simplify it to a knowledge organiser. You just need to remember the diagram, the word list, or the quotes on the knowledge organiser. It is expedient and gets students through the lesson, but it commonly doesn't stick.

Instead of focusing on simplification, teaching and learning should instead be intent on scaffolding learning so that students can productively experience more complexity and difficulty but with success.

Are we oversimplifying teacher learning too?You wouldn't expect a fighter pilot's cockpit to only feature an on-off switch and little else. Their job and their equipment is simply far too complex.

Similarly, handing a teacher a booklet or a poster is going to be an inadequate tool to capture the necessary complexity of teaching and learning.

"... handing a teacher a booklet or a poster is going to be an inadequate tool to capture the necessary complexity of teaching and learning."

It is understandable that busy teachers need manageable access points for their professional learning, but there are equivalent dangers to students' learning in classrooms if we oversimplify adult learning.

Teachers are commonly expected to engage with research evidence. Indeed, my day job is to lead the creation of resources that do just that. It makes sense to produce accessible posters that summarise evidence. However, if we don't walk teachers into the complexity of engaging with the actual research evidence in some depth and complexity, actual professional knowledge building is unlikely to happen (never mind teaching habits shifting).

Teachers need to think hard too. Given the sheer complexity and diversity of the classroom environment, successful teaching realistically requires a diverse and complex array of possible solutions.

Yes - experts can do the simple things well - but teacher professional learning must aspire to properly explore complexity and difficulty. A glossy poster will not be enough.

We must avoid the oversimplification trap as must as seek to make learning manageable and not too difficult. It may be a little more time-consuming. It may be a little harder to sustain. But it will be necessary to achieve successful teaching and student learning.

Related readingDaisy Christodoulou has written an article about the dangers of using AI and more so that we become a 'stupidogenic society', where offload our most important thinking to technology. READ MORE HERE . Sign up for Alex QuigleyAlex Quigley (The Confident Teacher) is a blog by the author, Alex Quigley - @AlexJQuigley - sharing ideas and evidence about education, teaching and learning.

Subscribe .nc-loop-dots-4-24-icon-o{--animation-duration:0.8s} .nc-loop-dots-4-24-icon-o *{opacity:.4;transform:scale(.75);animation:nc-loop-dots-4-anim var(--animation-duration) infinite} .nc-loop-dots-4-24-icon-o :nth-child(1){transform-origin:4px 12px;animation-delay:-.3s;animation-delay:calc(var(--animation-duration)/-2.666)} .nc-loop-dots-4-24-icon-o :nth-child(2){transform-origin:12px 12px;animation-delay:-.15s;animation-delay:calc(var(--animation-duration)/-5.333)} .nc-loop-dots-4-24-icon-o :nth-child(3){transform-origin:20px 12px} @keyframes nc-loop-dots-4-anim{0%,100%{opacity:.4;transform:scale(.75)}50%{opacity:1;transform:scale(1)}} Email sent! Check your inbox to complete your signup.No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

July 12, 2025

July 5, 2025

The problem with mindfulness in schools

Mindfulness is hugely popular across the world and there is a question to be asked about whether it could prove useful at scale in schools and colleges.

It is clear that mental health referrals are up across young people, from around one in eight children and young people in 2017 to one in five in 2023.

Not only that, more than a quarter of a million (270,300) young people were still waiting for mental health support after being referred to mental health services in 2022-23.

There have also been clear and proven links between mental health and school absence for year 11 students. Since COVID, schools have been grappling with falling attendance and struggles with young people not getting access to mental health support.

There is some consistent evidence that mindfulness interventions can help adults in groups. It makes complete sense then to trial it in schools to see if it can address the 'mental health crisis' that politicians and education leaders talk about so commonly.

The problem with mindfulness interventionsA proven, relatively cost effective approach like mindfulness is just what schools and colleges need, right?

Alas, what seems promising for adults doesn't appear to have the same positive effects on young people in groups based in schools.

The MYRIAD trial ('My Resilience in Adolescence') based at Oxford University producing disappointing results for whole-school interventions. It showed that a series of lessons on mental well being and mindfulness strategies made no positive difference a year later. Some children who got the intervention actually had higher teacher-reported emotional issues after undergoing the training.

Research published by the Department for Education in February showed in new research involving over 20,000 children, presented a more mixed picture. It claimed no impact on young people's emotional difficulties in the short or long term.

The DfE research found some interesting wrinkles about how children were impacted differently. Their analysis suggested that girls in primary schools may benefit from a short term approach, whereas children with Special Educational Needs and with higher levels of prior mental health symptoms may experience worsened emotional difficulties a year later.

They also found that relaxation techniques (seemingly harmless to the untrained eye) were associated with higher levels of emotional difficulties for young people in secondary school.

Though the finding are not categorial, mindfulness doesn't appear to be a group solution. Indeed, for the children in greatest need of support, it may even make things worse.

In a culture that expects schools to do more and more, it is a chastening example that scaled up universal approaches cannot compensate for targeted, individual, and expert, health services.

The evidence appears to reveal that we need to be more specific about groups and individuals - pretty much the costly, intensive support to address significant social and emotional issues.

It is pleasing to see that the government are committing to offering new investment so that 6 in 10 pupils will have access to a mental health support team by March 2026. Clearly, the expert services need building up again so that they can support every child. But what is also clear is that there is a long way to go before we have a functioning support system.

What should schools do?Mindfulness training... relaxation techniques...lessons on GRIT... approaches to boost belonging. It is all tricky territory of emotional health and well-being that we need to be careful about. The following the evidence trail is doubly important and should give us pause.

The assumption is that schools should always do more. Maybe share some simple strategies, or establish a mental health lead? Doing something is better than doing nothing, right?

The issue is that schools doing nothing - at least when it comes to universal mental health approaches, or well being assemblies that promote mindfulness - may be the safest, best course of action. It is paradoxical but it appears to be true.

Though access to mental health services is still crucially compromised, schools should devote their efforts to helping young people and their families to access the best local support available.

Related reading:

Approaches to whole school and system approaches can suffer from a 'voltage drop'. Find out more in my blog HERE .

June 28, 2025

June 21, 2025

Reading every day matters

In Brazil in 2012, the government offered prisoners the chance to read for their lives.

Their novel approach saw prisoners granted four days of remission for each book they read and reviewed. Prisoners had the opportunity to submit up to 12 reviews per year, which equates to a maximum of 48 days of remission in total.

There was some evidence that claimed Brazilian prisoners read nine times more than the national average of five books per year.

There is no easy fix to the challenge faced by prisoners, or any person young or old who struggles with literacy, but being a strong and successful reader is unequivocally valuable in countless ways for education, careers, well being, and for life.

Reading can offer early opportunities in education, as well as restoring hope and offer a change at real rehabilitation.

In short, reading every day, in school or even in prison, really matters.

Reading every day before school mattersBefore children ever get to school, reading every day matters.

Early book talk - with the brain building to-and-fro of reading picture books and similar - is vital for language development. Children being exposed to the unique vocabulary of early reading gives an early vocabulary advantage.

Researchers from the USA calculated that children who were read to daily (around five children’s books) would hear well over a million more words (an estimated 1.4 million more) than their peers who were not read to daily by the age of five.

A million word gap can emerge if children aren't reading every day. This matters.

Reading everyday in school mattersRemember school closures during the pandemic?

Research shows that across a range of European countries found a significant association between the duration of COVID-19-related school closures and the adjusted decline in reading literacy.

While remote learning did prevent complete learning loss, it was substantially worse than regular in-school learning. Students in England, who on average spent fewer days away from school than peers in countries like the USA, appear to have maintained reading standards, and therefore rocketed ahead of Europeans and anglophone countries. A focus on reading appears to have mattered.

In most cases, missing more school meant a decline in reading standards. The decline in reading in the home, along with adult reading habits, is a vital social issue. For children in England, during the pandemic at least, a battle for reading standards may have been won, but the war is far from over.

For students to access the wider academic curriculum, fluent and skilled reading is simply essential. Students sitting around 30 hours of exams for their GCSEs in reading have to tackle lots and lots of tricky academic reading.

The reading age of students, unsurprisingly, correlates with their GCSE outcomes. In subjects like English and history, this is obvious, but the link is just as strong in subjects like science and mathematics.

For those students who missed more days of school during the pandemic, or whose attendance has been patchy ever since, there are lots of challenges, but reading every day and reading successfully is one of the critical ones.

Reading in adult life mattersWeek after week, depressing articles chart the slow death of deep reading. Perhaps we won't realise just how important it is to thinking, learning, happiness and mental health until it is gone?

For those in prison, whose lives have mostly been taking away from them, the opportunity to read, and improving their literacy, may just be a lifesaver.

In England, around 57% of prisoners read below that of an 11-year-old. This correlation isn't just an interesting fact. Their ability to read will limit their ability to get a job and rehabilitate.

Adults may get life saving advice from reading, find enduring emotional sustenance from reading about characters in their favourite tales. They'll also be able to read an application and apply for an dream job to live a better life.

Prisoners in Brazil were given a chance to read for their life because the powerful value of reading each day was understood. Now, over a decade later, reading is in decline in England. We need to rediscover why reading really matters: before school, during school, and in all corners of adult life.

Alex Quigley's Blog

- Alex Quigley's profile

- 12 followers