Alex Quigley's Blog, page 3

June 14, 2025

Is it better to read on paper or an e-reader?

Should we ditch the Kindle and pick up a paperback? Or put away the plain ol’ textbook and dive into digital learning instead?

In our brave new world of ever-present technology, we are left with questions about what is best: tried and tested traditional methods or innovative new technologies.

New research from the University of Valencia, Spain, has synthesised research from the last two decades and has found that when it comes to text comprehension – reading to learn – that print reading on paper may still be bettering glossy new screens.

Importantly, for teachers and school leaders, age really mattered in this synthesis of research when it came to the impact of the mode of reading.

When learning to read, such as in primary school, a negative relationship was observed between leisure digital reading and text comprehension. However, for secondary and university age students, the relationship turned into a positive one.

Age and stage of reading development matters when it comes to what mode of reading we choose.

What are the benefits of traditional reading methods?Reading a lot and making it a habit is vital. There is simply little substitute for reading widely and well. We can learn thousands of words a year, but reading supercharges that process and it offers a uniquely powerful diet of rare words we only encounter in reading.

What the research indicates is that reading 10 hours of print on paper may prove more likely to be retained. We don’t exactly know all the reasons why this is the case, but the ‘reading mindset’ of traditional texts likely makes a difference.

With digital texts, we can scroll and click, but that can potentially disturb the careful act of reading. Pop ups and additional texts or graphics may distract and much as add value to reading comprehension.

The ‘deep reading mindset’ of traditional reading likely proves more immersive. Additionally, seeing the words in print offers thousands of tiny cues for meaning, and patterns that can make a meaningful difference over time.

I often feel the loss of print when I am listening to an audiobook. Even though it offers me lovely experiences (such as on a long car ride, when I can read immersively), I tend to forget what I have listening to much easier.

Personally, when I read digital texts, such as research, I can get lost in a digital-rabbit hole of interesting stuff, but I can invariably lose track and also get struck by attractive images and links that lure may attention away.

Should we embrace new technology?When it comes to wider reading, parents and teachers can and should consider e-readers and audiobooks. They can offer alternative to traditional habits than can surprise and offer an engaging alternative. For example, on a car ride with young children, an audiobook could prove much more beneficial than they watching a video on a tablet or similar.

Age, stage of reading, motivation, and simply a change of routine can all matter, and technology can have its place.

We should be wary of a Luddite attitude to technology that rejects e-readers or digital textbooks, but at the same time we should select our mode of reading with care.

It is helpful to identify goals for reading and when it comes to leisure reading, aim to retain a steady diet of memorable print reading. In my personal reading, if I want something to stick and learn about a topic, I’ll buy the book or print off a paper copy for text marking and similar.

When it comes to younger children, we should give them lots and lots of exposure to traditional print (thereby developing ‘print knowledge’). It is like how young children also need to undertake lots of traditional handwriting and spelling to embed these into their writing habits.

The feel and touch of traditional reading, such as simply turning the page and scanning the text, may offer lots of small gains we should be careful not to lose.

Should we put down the e-readers? For young children, we likely should. Once they are skilled, deep readers, we can vary the reading diet further. But we should always be careful to pay attention to both what and how we read.

May 31, 2025

5 ways to revive form time reading

Tutor time reading has experienced a wave of popularity in English secondary schools over the last few years. As schools responded to plummeting reading habits, along with a focus on reading in inspection and across curriculum, it became a popular fix for promoting and practising more reading during the school day.

In terms of implementation, I’ve mostly worked with, or observed, schools undertaking tutor time reading two or three times a week. In some cases, a brilliant store of new books was invested in to promote the new strategy, along with new resources being produced to communicate and promote reading.

But a couple of years on, I now speak to lots of literacy leaders who are strained in their attempts to sustain form time reading. In some cases, there is an honesty that admits that tutor time reading is in need of life support.

When reading goes wrong: failed implementationWhy is the implementation so variable and in need of reviving in so many cases?

The common issues I observe include some of the following:

Teachers are unclear of the value of why they are doing form time reading. Teachers understand how reading fiction texts may be interesting, but not useful for their science curriculum, so their ‘buy in’ is pretty weak.Teachers are too busy and so the time gets pushed out by other priorities.Some teachers lack confidence in reading aloud, or don’t know the texts very well, so they cannot promote them with the understanding, or be nimble responses to questions, that are needed. Teachers, and students, get pulled into interventions or other events, so the management and timing of form time reading can easily be knocked off.Poor behaviour and student resistance to reading.Form time reading gets off to a good start, but form tutors change roles, leave, or new teachers (or cover) don’t get the same launch experience, or training, and so year 2 sees a steep decline.Implementation of any whole approach is difficult and sustaining it across terms, and particularly school years, is doubly hard. It is no surprise, despite schools investing in stacks of lovely book stock, that they don’t get read and used with the same shiny excitement.

5 strategies to revive tutor time readingIn most cases, it is worthwhile attempting to revive tutor time reading (although in some cases it would be the brave and right thing to stop it completely to do other things). Like most attempts at implementation, it requires time, effort, and there is an ‘opportunity cost’ that comes with such effort.

I’ve worked with a range of schools and literacy leads looking to make the effort to improve upon their literacy strategy. Here are 5 strategies that may have revive flagging form time efforts:

Audit existing approaches and respond to the feedback with changes. School leaders are so busy, there is often too little time to monitor and evaluate how things are going (which is why fewer school priorities is often key). An honest audit, with a sample of students and form tutors contributing, is likely a necessity to work out how to improve upon the existing approach.Make intelligent adaptations to approach. Are the text choices working? Is there enough time to do the reading? Is Wednesday a nightmare for year 8 form classes? Do some pupils need targeted support resources? It is rare that a literacy strategy doesn’t require tweaks or even wholesale changes. A literacy lead should determine what is likely the most effective approach to implementing reading once more, and adapt and clarify the new model based on feedback to targeted evaluation.Overcommunicate the ‘why’, ‘what’ and ‘how’. Teachers are incredibly busy. In reality, form time is rarely at the top of the priority list. As a result, literacy leads need to overcommunicate the ‘why’ of additional reading. They can use compelling personal stories and refer to robust evidence. Not only that, but leaders also need to overcommunicate the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of every practical element of the sessions. Offer training and targeted support for teachers. Many literacy leads (often with a background in English or Drama) don’t anticipate all the issues for teachers trying to read aloud. They may need training in how to read aloud, or how to respond to questions that keep up the ‘flow’ of reading. I have worked with leaders who have had to support teachers who struggle to read due to being dyslexic, or don't know what to do when high need students appear locked out of the experience. In short, some targeted support is likely to be needed.Routinely celebrate success. It is easy to move onto the next thing and assume everything is going fine after a bit of a September revival and training. The reality is going to be patchy progress. Aim to sustain interest and focus that can drive improvement to the process. Celebrate with students, parents, and especially staff. For instance, tell the stories of students having their understanding unlocked, and its connection to school success and home reading.It all feels like a lot of effort for 40, 50 or 60 minutes of extra reading a week. That is because it is!

For the opportunity to be worth the cost, it needs to be clear that the effort leads to some positive impact. Implemented well, form time reading could nudge a reading culture, or see individual students be successful with reading beyond what they thought possible. But getting there is likely to be hard and in need of a revival effort for many schools.

Related reading:

There is a powerful Greenshaw Research School blog series HERE on how they implement form time reading.*** TRAINING OPPORTUNITY ***

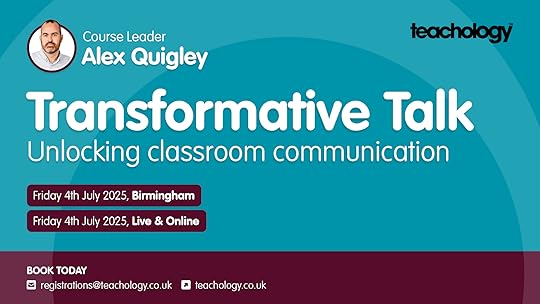

Is everyone at your school clear about what transformative talk should look like and sound like? Can every teacher exploit the power of talking about what you read in class? My new Teachology Masterclass on 'Transformative Talk: Unlocking Classroom Communication', explores manageable classroom routines that impact learning. Teachers, middle leaders, literacy leads, and school & college leads are all welcome. It is live and in person in Birmingham on the 4th July. FIND OUT MORE HERE.

May 24, 2025

Rosenshine on Knowledge Structures

Barak Rosenshine is most famous for his principles of instruction, but what did he have to say about building knowledge?

In his writing on ‘Advances in research on instruction’, he put forward the important – and familiar notion – of ‘knowledge structures’. Put simply, this is how information is organised and stored in our long-term memory.

Most importantly, when considering ‘knowledge structures’, Rosenshine emphasises the size of these structures, the strength of the connections between pieces of knowledge, along with the richness of the relationships, so that learners can process new information and solve problems.

What Rosenshine was emphasising, decades before the recent interest in cognitive science, was that building knowledge and retrieving it was crucial, but making it meaningful, and applying it, was just as vital.

For example, you may be able to remember quotes from 'Romeo and Juliet' for an exam, but the trick is to be able to connect, explore, and apply the evidence from the play to the exam question. You can recall the prologue about the ‘star-crossed lovers’, but also connect it to Shakespeare’s aim to forceful grasp the attention of his audience.

For Rosenshine, emphasising the importance of cultivating ‘knowledge structures’ meant three implications for teaching:

1. The need to help students develop their background knowledge.

2. The importance of student processing, and:

3. The importance of organisers.

Now, these three implications sound familiar to those leaders and teachers exposed to the promotion of a knowledge-rich curriculum. And yet, perhaps the necessity to support ‘student processing’ was perhaps obscured by the dominance of curriculum sequencing and promoting retrieval practice?

Rosenshine cites Palincsar and Brown, as they aimed to describe how to support a deeper processing of information:

“Understanding is more likely to occur when a child is required to explain, elaborate, or defend his position to others; the burden of explanation is often the push needed to make him or her evaluate, integrate, and elaborate knowledge in new ways.”

What is striking is how active the requirement is for explanation and argument. It poses a challenge to notions that developing knowledge is the mere stacking of information in quiz after quiz, or that building knowledge is somehow passive.

Promoting processingRosenshine goes on to share an array of practical teaching strategies for promoting ‘processing’:

Extensive reading of a variety of materials. It is apt that reading comes first when it comes to knowledge structures. The special language of reading is dense and packs in more rich information than most verbal explanations. It is therefore essential to carve out curriculum time for wider reading. Identifying ‘reading clusters’ around specific topics can help, along with finding as many opportunities for extended reading as possible.Explain the new material to someone else. The call for explaining promotes high quality classroom talk, such as ‘Think-pair-share’, or ABC feedback, where pupils are expected to share their ideas, offer evidence, and more. The ability to explain and teach someone else aids pupils’ attempts to cohere and express their knowledge. Write questions / answer questions. It is common practice to answer questions on a new topic, but less so to generate questions for a topic you’re learning. This minor shift to getting pupils to generate questions can prove a powerful way to process a tricky topic (we don’t need to obsess about exam-type question framings to do this well either).Develop knowledge maps. Devising concept maps, mind maps, or other graphic organisers are a familiar strategy to teachers, but perhaps we are less explicit about training our pupils to use these strategies for more consistent use. In a subject like science, using concept maps for biomes or similar can help pupils cohere and organise a mass of seemingly unconnected knowledge.Write daily summaries. Summary writing appears to be powerful for reading comprehension and understanding complex new knowledge about a topic. Even single sentence summaries can help organise and evaluate what has been learned and to better process it. Apply the ideas to a new situation. Pupils can find it difficult to apply knowledge to new scenarios or questions (it is a common reason why they fail with an unfamiliarly worded exam question that seems new to them). Intentional application of knowledge to new situations and questions is therefore essential for meaningful knowledge structures. For example, when learning about ‘adaptation’ in biology, you can apply the concept to different environments that haven’t been explored in the lesson.Give a new example. Generating new examples, like applying new ideas, forces pupils to cohere what they knowledge and extend upon it. For instance, if you used an example of a deep sea adaptation, you could then pose the task for pupils to process an adaptation in a desert biome. Compare and contrast the new material to other material. The power of comparing examples with non-examples is well known, as it hones a pupil's ability to really understand the nature of a concept. For example, when exploring the Great Fire of London in history, you might compare primary sources with secondary sources, to understanding the changing views of the fire, its causes and significance. Study for an exam. The ‘testing effect’ is a well-known concept. We all know that being given a goal and a deadline for a test makes you organise your learning and attempt to process what you know. Making the testing low stakes can build momentum, whilst 'real' exams (love 'em or hate them!) create a meaningful goal to apply one's knowledge.Rosenshine’s strategies are not exactly novel – decades ago or now – but they still prove to be essential teaching approaches to best help pupils better process and develop their knowledge structures. I'd speculate they don't all happen regularly or are implemented with consistent success.

As curricula change, trends pass, and language to describe teaching shifts, it is reassuring to explore enduring insights into the importance of knowledge and how pupils can actively organise into structures that are likely to lead to success.

May 17, 2025

May 3, 2025

Learning barriers, not labels

Let me introduce you to James.

James finds it hard to articulate his thoughts due to limits to his vocabulary and a difficulty in understanding complex language in class. He can rely on simple words, repeat phrases, and non-verbal communication to get through the school day.

In science, he particularly struggles with following the rare, specialist language in the textbook.

In English, when asked to describe how a character felt, he says, “They were sad,” but he cannot elaborate on why or how he knows.

How would you teach a student like James? Take a moment to reflect on the teaching strategies, and subject content, you would focus on to support James to access the school curriculum.

Now, consider the following: you have been informed that James has autism. Or you have been informed that James has development language disorder (DLD). Or you have been told that James has dyslexia.

Would you teach differently if you were to learn about the designation of the special educational need?

Do labels always help learning?

Understanding special educational needs can be a useful starting point in helping teachers understand effective approaches for teaching high need pupils like James. For instance, autism and dyslexia have research and advocacy to guide teachers regarding generic learning barriers.

In addition, for James and his family, there could be significant emotional benefits to the discovery that your issues have a root cause. Labels can liberate families and help them understand, with a supporting community, to take the next step.

Crucially, however, the benefits may quickly dissipate or even backfire if we are not careful. Take dyslexia. The reality of dyslexia is that it presents on a complex spectrum and James may or may not present with most of the common indicators. His assessment may be rather opaque about what to do, and it may be co-occurring with speech and language issues that are less well picked up on via the chosen assessment.

Too often, given the complex, and often co-occurring nature of SEN designations, they can sometimes tell us little about what to do to support James most effectively. For teachers, we may unwittingly lower our expectations for James’ reading and writing ability because ‘he is dyslexic’, or pursue poorly evidenced solutions, such as special ‘dyslexia fonts’ or unproven technology.

To support James best, it is likely we need to concentrate on his barriers to learning and focus less on broad and complex (sometimes contested) SEN labels.

Teaching language: being inclusive by design

We know a lot about high quality teaching of reading, writing, and academic vocabulary.

Of course, many pupils can struggle with language in similar ways to James because academic language is intrinsically difficult and translating speech into writing can prove uniquely tricky.

Positively, many teachers will already possess the powerful teaching strategies that can best support James in science, English, and beyond. The EEF guidance report on ‘Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools’ states:

“Yet, far from creating new programmes, the evidence tells us that teachers should instead prioritise familiar but powerful strategies, like scaffolding and explicit instruction, to support their pupils with SEND. This means understanding the needs of individual pupils and weaving specific approaches into every day, high-quality classroom teaching—being inclusive by design not as an afterthought.”

To best support James, we likely need to explicitly support his reading, through reading fluency strategies, reading comprehension strategies, vocabulary or decoding skills. When we more closely diagnose why he cannot understand why a character is sad, it may be that he struggled to understand the meaning from the text, or it was a struggle to generate synonyms to describe a range of nuanced emotions.

The barriers he is experiencing require careful diagnostic assessment, but the more we focus on the learning – be it reading, talk, writing or vocabulary – the more targeted our approach for James.

If we were to utilise evidence-informed strategies related to teaching vocabulary, or reading fluency, or dialogic talk, we are likely not just to aid James to access more of the curriculum, but we are also likely to teach and be inclusive by design. Lots of pupils struggle with translating the tricky vocabulary or science or reading aloud and engaging in complex book talk.

I think that teachers can make gains from building their knowledge about specific educational needs, but their actual practice is most likely to improve if they focus on the barriers to learning and the effective strategies to address those barriers.

Teaching to the generic notion of a ‘dyslexic learner’ may obscure what may actually be best to support James’ learning.

Let’s focus on learning barriers and not labels.

April 26, 2025

Should we scrap An Inspector Calls?

The canon of English literature - and what is taught in English classrooms - is always the stuff of fierce debate and news headlines.

A new TES article claims schools 'need support to break away from An Inspector Calls'. So, we should ask the question, should it be scrapped, what should change in the curriculum, and why that might prove so difficult and not offer the results we may hope for?

Are teachers struck with a strange case of excessive Inspector Calls, or are more complex factors at play when it comes to what is being taught? The TES article poses that budget constraints and a lack of resources are important reasons why relatively few texts being taught over and over again in English literature.

The article also argues that time and professional development are a necessity for any curriculum change to English literature. This is no doubt true too. I think they are both vital to build the confidence of teachers so they are willing to experiment with a new text for a qualification that can mean so much to their students.

An excellent 'Lit in Colour' report is cited by the TES article. 'The effect of studying a text by an author of colour: The Lit in Colour Pioneers Pilot', reveals the crucial point that any change of texts in English literature requires "time, money, subject knowledge and confidence", but also "a high level of effort and commitment" to "make change happen".

Final call on the inspector?I think it is also helpful to try and understand the effort and commitment invested by English teachers which likely accounts for the enduring popularity of 'An Inspector Calls'.

First, why is the inspector calling to 84% of students sitting English AQA English literature?

In pragmatic terms, people do have copies of the text and resources. Perhaps more so, the play is also short and relatively accessible to students - many of whom can struggle with other more complex texts on the specification. When curriculum time feels thin, and students struggle, picking the most amenable text makes sense and it proves helpful to many students.

I first taught 'An Inpector Calls' in my fourteenth year of teaching. I had written it off myself (for no good reason in truth). And yet, upon giving it a go, for a change, I was happily surprised just how much my year 10s enjoyed reading it.

Did they enjoy the essays and the revision? Probably not. Did they enjoy the pressure of translating the play into exam speak? Not so much. But such is the way go all examined texts who are brokered for annual exams.

They did enjoy the exploration of power and privilege, and gender and violence, of billionaires and benefactors. Though the text can commonly be written off as stale and pale, there is something pressingly contemporary about a rich patriarch ignoring his responsibilities and making daft comments about war and wealth. The book offers an interesting mirror on the contemporary world students are submerged in.

Seeing it dismissed by many has made me think of why English teachers do, year-in and year-out, teach the same texts. It is not merely laziness, or boredom, or just cold hard pragmatism.

Literary texts are also taught because they are familiar. This breeds confidence, which can make a teacher feel safe and creative with their truculent year 10s on a Tuesday afternoon. Though I do believe these traditions can stall the introduction of even better texts, we should take care not to write off the hard-won habits and routines of lots of hard working teachers.

There is also some emotional investment in having been taught a text in school, then going on to teach it yourself. Like Alan Bennett's 'The History Boys' the urge to 'pass it on' can prove compelling. This likely isn't merely inertia from English teachers, nor do I think it is simply a rejection of change or diversity.

As the new curriculum assessment review looms into view, I am sure the English literature qualification will see a timely evolution. Practicalities like text length and teacher training will rightfully be raised. Contemporary, diverse texts should be introduced alongside the familiar classics. But we must ensure teachers have the time, training and resources to support them to do it confidently and well.

Calling for change and supportIt is vital that when we call for curriculum change, that it is balanced with the necessary supports to enact that change.

As curriculum expert, Lawrence Stenhouse, put it well over half a century ago,“The central problem of curriculum study is the gap between our ideas and aspirations and our attempt to operationalise them.”

If we do choose to move on from An Inspector Calls, or place it alongside contemporary, new texts, we need to understand the support needed for busy teachers. Curriculum development depends on teacher development.

One of my favourite quotes about teaching is from Vivianne Robinson. It is from her book on reducing change to increase improvement (and yes, that is a counterintuitive statement):

“Instead of taking for granted that change will lead to improvement, we should do the opposite – that is, believe that change will not deliver our intended improvement unless there are structures and processes in place for ensuring that all involved can learn how to turn change into intended improvement.”

I think all the contributors writing in the TES article - whether they like 'An Inspector Calls' or not - recognise the reality that changing literary texts is tricky and it requires sensitive handling. As already stated, it requires subject expertise, time, training, resources, and sustained support.

Maybe it is time for the inspector to make a final call. If it is, then it will require a chain of events that sustains support for teachers, even when the headlines have faded and the classroom doors close on another GCSE cycle.

April 12, 2025

Alex Quigley's Blog

- Alex Quigley's profile

- 12 followers