Kay Kenyon's Blog, page 13

September 7, 2016

Worldbuilding with Martha Wells

Guest posts for the Ways into Worldbuilding series will appear most Wednesdays through early November. Today I welcome one of my favorite authors to the site: Martha Wells.

Martha Wells has written many fantasy novels, including the Books of the Raksura series (beginning with The Cloud Roads), the Ile-Rien series (including the nebula-nominated The Death of the Necromancer) as well as YA fantasies, short stories, media tie-ins, and nonfiction.

Aside from reader expectations, why do you build worlds? Is it more of an obligation than a pleasure? If the latter, what is enjoyable or rewarding about this aspect?

I enjoy it, and it’s one of my favorite parts of developing a story. I like coming up with the details, and exploring how the world has affected my characters, and how it can determine the direction and feel of the story. I find it rewarding to come up with something that feels true and consistent no matter how fantastic or far out it is.

How important is worldbuilding in your stories? Is it a goal for you to create an innovative world, or do you favor having the milieu sit more comfortably in the background?

I find it pretty important, and I try to make as much use of it in my fantasy as possible, since it’s something I enjoy a lot in the books and stories I read. I try to use it to shape the story and develop the characters.

I like to try to create an innovative world, but I also feel it should be fairly transparent to the reader. Getting across what is unique and interesting in your world without weighing down the pacing or plot is important to me, and it’s something that I think takes a lot of experience and practice, and reading other authors who do it really well.

Do you apply any sort of process to worldbuilding? How does a coherent world emerge in your work?

I don’t really have a set process. For me, the characters and the world come to life together. The characters are shaped by their world, in their physical attributes, their goals, their problems, what they have to do to survive. So while I’m developing the main characters, I’m building the world, and I add more detail as the plot goes along.

Describe a milieu from one your works, and the aspects you found most rewarding. Which ones did readers comment on the most?

In The Books of the Raksura series (the first book is The Cloud Roads) the setting is the Three Worlds, a vast landscape that the reader (and the writer to a large extent) is discovering along with the characters. There are a large number of sentient species, none of them human, occupying the ground, sky, and water. Many of them have different levels of technology, often based on biological or magical processes, or combinations of both. The characters encounter many remnants of vanished or scattered civilizations, and stories and evidence of past cataclysmic wars.

The two elements that readers have mentioned the most are that none of the characters are human, and that the world feels so big and so limitless.

What kind of worldbuilding tropes are you tired of? Please share a couple of worlds that have especially impressed you. (Please take Kenyon novels out of the running on this one.)

I’m tired of worlds based on medieval Europe that are extremely grim where everything’s cold and hopeless and violent, though I’ve seen a lot of them that were written extremely well and were very compelling. I think at this point in my life I just want to see more worlds that are hopeful. (And warm.)

Two worlds lately that have really impressed me are: the setting of Kai Ashante Wilson’s The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps and A Taste of Honey. At first it seems to be a vibrant, original fantasy world, then the science fiction elements start to come into focus and that just makes it even more exciting.

Also, The Best of All Possible Worlds by Karen Lord, which is a really intriguing SF journey across a planet populated by different groups who have come to it for refuge.

Any peeks you’re willing to disclose about your next world or what we might learn about the milieu in your next story?

In The Harbors of the Sun, the last in the Books of the Raksura series, the setting includes a place that’s been mentioned a lot but hadn’t been seen yet. That’s Kish Karad, the capital of the Empire of Kish.

_________________________

The Edge of Worlds at www.amazon.com and at Barnes and Noble.

About this post. Ways into Worldbuilding is a series of interviews I conducted in the summer of 2016 with SFF writers, asking about their opinion on, and approach to, creating fictional worlds. Watch this space for upcoming interviews with Kris Rusch, Django Wexler, Louise Marley, Tananarive Due and more amazing writers!

Previous interview: L.E. Modesitt, Jr., August 31.

Next interview: Kristine Kathryn Rusch, September 21

August 31, 2016

Worldbuilding with L. E. Modesitt, Jr.

Guest posts for the Ways into Worldbuilding series will appear most Wednesdays through early November. We lead off with L. E. Modesitt, Jr.

L. E. Modesitt, Jr. is the author of more than 70 science fiction and fantasy novels, a number of short stories and technical and economic articles. His novels have been translated into German, Polish, Dutch, Czech, Russian, Bulgarian, French, Spanish, Italian, Hebrew, and Swedish. He has been a U.S. Navy pilot; a market research analyst; a real estate agent; director of research for a political campaign; legislative assistant and staff director for U.S. Congressmen; Director of Legislation and Congressional Relations for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; a consultant on environmental, regulatory, and communications issues. His first story was published in Analog in 1973, and his latest books are Solar Express [Tor, November 2015] and the forthcoming Treachery’s Tools [Tor, October 2016].

Aside from expectations, why do you build worlds? Is it more an obligation than a pleasure? If the latter, what is enjoyable or rewarding about this aspect?

I build worlds because (1) I can’t conceive of having a meaningful story without it being set in a consistent and multifaceted world; (2) setting up and deepening the world enriches the story, both for me and for the reader; and (3) it just feels right. The entire process is rewarding because the details bring a richness and an “aliveness” to the world, at least for me.

How important is worldbuilding in your novels? Is it a goal for you to create an innovative world, or do you favor having the milieu sit more comfortably in the background?

In anything I write, my goal is to have a world that is realistic and consistent in its own terms, and in all of my fantasy series, there’s a key innovative aspect of the magic system which affects everything from the smallest to the largest aspects of people’s lives. In the Saga of Recluce, magic is based on the conflict between order and chaos, not on a gigantic scale, but because the entire Recluce universe is based on the energy flows between order and chaos. In The Imager Portfolio, certain individuals have the ability to visualize objects into being, but that visualization requires a great amount of personal energy and great skill, and most untrained imagers die before adulthood. In the Corean Chronicles, the ability to do “magic” is literally tied to the life-forces of all living things, and in the Spellsong Cycle, magic requires perfectly sung and rhymed spells matched perfectly to accompaniment.

So, in all of these instances, the magic system is innovative, but also almost pedestrian in the sense that it melds with the culture and the geography.

Do you apply any sort of process to worldbuilding? How does a coherent world emerge in your work?

In anything I write, and particularly in fantasy, I begin with the concepts of the world – the technological (and/or magical) level, the geography and climate, the cultures (and all of my worlds have multiple cultures, although in the SF, it’s sometimes not so obvious),and the governmental structures. For fantasy series, I have a rough map, as much to scale as I can manage, which gets refined as I go along. Equally important, I build in a history, because every society has a history, and there are references throughout to historical or mythical figures and events.

Describe a milieu from one your works, and the aspects you found most rewarding. Which ones did readers comment on the most?

The world-building in the “Ghost” books was particularly intriguing and rewarding, because those three books, beginning with Of Tangible Ghosts, and one short story take place in the 1990s of an alternative history of our Earth where ghosts are indeed real, and manifest themselves as electro-magnetic phenomena created by violent knowledgeable death. There are a number of societal and historical implications of very real ghosts that also raise questions about how and why certain societal behaviors exist, and even the impact on population growth and the way war is conducted – or not conducted.

Most likely the Recluce Saga has received the most comments, but I suspect that’s simply because the Recluce books – eighteen so far – have been continuously in print for twenty-five years. The Imager Portfolio books also receive quite a few comments.

What kind of worldbuilding tropes are you tired of? Please share a couple of worlds that have especially impressed you. (Please take Kenyon novels out of the running on this one.)

I’m tired of high-tech worlds that don’t make sense either technologically or economically, and I’m especially tired of grotesque world-building of the sort that China Mieville often engages in where one of the major points, if not the only major point, seems to be, at least to me, to make the setting both as detailed and as grotesque as possible. As far as really impressive world-building, I think Ursula K. LeGuin did a magnificent job with The Left Hand of Darkness. In fantasy, I was impressed with what Aliette de Bodard did with The House of Shattered Wings.

In a series, do you lay in mysteries, trusting that readers will be intrigued and look forward to learning the answer in later books? How do you feel about making the reader wait to learn important world features?

I don’t artificially create mysteries about the world, but I try to let the reader know things as the protagonist either encounters or thinks about those aspects of the world which affect the development of the story. And often what a protagonist thinks isn’t quite the way things really happen or the way those events will be seen by later generations. This becomes apparent in the Saga of Recluce because the events in the books and stories take place across nearly 2,000 years, and no one protagonist occupies more than two books.

Any peeks you’re willing to disclose about your next world or what we might learn about your latest world in your next book?

The tenth Imager Portfolio book – Treachery’s Tools – will be out this coming October, and the eleventh book – Assassin’s Price – will be out in July of 2017. In both these books, and especially in Assassin’s Price, readers will find out a great deal more about the twisted lineages of the ruling family and their ties to the stronger imagers, not to mention the most pivotal murder in the history of Solidar. As for the Saga of Recluce, the next book is Recluce Tales, coming in January, which features 20 stories, all but three of them new, set across two thousand years, one of which deals with the first “Rationalist” colonists.

The tenth Imager Portfolio book – Treachery’s Tools – will be out this coming October, and the eleventh book – Assassin’s Price – will be out in July of 2017. In both these books, and especially in Assassin’s Price, readers will find out a great deal more about the twisted lineages of the ruling family and their ties to the stronger imagers, not to mention the most pivotal murder in the history of Solidar. As for the Saga of Recluce, the next book is Recluce Tales, coming in January, which features 20 stories, all but three of them new, set across two thousand years, one of which deals with the first “Rationalist” colonists.

About this post. Ways into Worldbuilding is a series of interviews I conducted in the summer of 2016 with SFF writers asking about their opinion on, and approach to, creating fictional worlds. Watch this space for upcoming interviews with Martha Wells, Django Wexler, Claire Cooney, Kris Rusch, Tananarive Due, and more amazing writers!

August 22, 2016

One Step at a Time

Today I hit a muddy patch in the novel. Not exactly a brick wall. Not really a bout of writer’s block, but a serious resistance to doing the work.

I did feel like writing but I just couldn’t quite picture the next sequence. If I’m perfectly honest, I

didn’t really believe in the plot at that point. I had confidance in the overall plot, but this section was like looking across a chasm where the bridge was down.

Twenty minutes into staring at the screen and getting nowhere, I reluctantly concluded I had to do some deep, methodical plotting. I was going to have to think this section of the story through in excruciating detail. And I so did-not-want-to.

Mind games.

This reminds me how much of writing is a mind game. The game of talking yourself into things (like writing anyway) and out of things (like worrying that it’s not very good.) I mean, I knew what I had to do, but it took a little while to convince myself. These are the kinds of times when a writer often decides to go shopping or clean out the in-basket. But my rule is that I have to work on the novel until a certain time each day. And that time was a long way away. So I could either do the work or sit there bored as hell for a few hours.

I was going to have to create a Step Sheet.

You know how sometimes you sit down to write, and you seem to know exactly what to do, or you trust that it will sort out as you write the scene? This was not one of those times.

Step Sheet.

The Step Sheet is a logical plot progression composed of 2-3 sentences in each step. First this happens, then this, then this. All the while making sure that it could believably happen in that order and that it satisfies external logic, internal motives, and of course dramatic content. It isn’t a scene plan–nothing complicated–it’s just a simple list. Because when you need this much heavy lifting on your plot, it isn’t about nuance. You just need to get across the chasm. You can make it pretty when you write it.

I like to number the Steps. It helps me believe that this is going to be simple. One, two, three, four. I do my Step Sheets in a notebook, never at the computer. I’m not a superstitious person, but Step Sheets must be done with a pencil and paper.

And yes, it worked. It wasn’t quite as unpleasant as I feared it would be. And, as I worked and reworked the Step Sheet, I found cool (for now, extraneous) ideas occurring to me. I jotted them in the margins, but continued building that bloody bridge.

So now I’m in a good mood again about the novel. (Oh, fragile writer’s mind!) Nothing annoying or daunting about tomorrow’s work. When I sit down to write in the morning, I’ll just walk over that bridge.

Hey, what was so hard about that?

July 18, 2016

Picky questions on the novel

For writers, what is the hardest part of a novel? Maybe it’s page 1 and page 400–and many big chunks in between. Some books go like that.

But today I’m more interested in what’s the most important part of a novel. Despite how crucial a good ending is, and how challenging the middle is, I think the beginning is the critical place. At least the beginning in terms of the musing you do before you write.

For me, first come the big-picture questions.

Big, sloppy questions.

1. What genre? Some of the aspiring writers I meet are surprisingly conflicted about what type of story to write. My only advice is to read in likely genres. Read a lot. Learn what stories you adore. You’ll be spending many years with them.

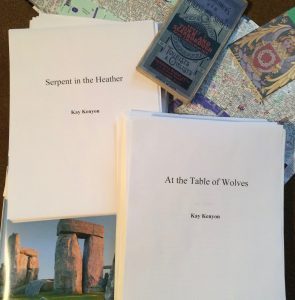

In my recent two books forthcoming from Saga, the answer to the genre question was Fantasy.

2. What kind of fantasy? Paranormal espionage. So many kinds of fantasy. Just read the nominees for the World Fantasy Award, and you’ll see the amazing variety of the literature.

3. What makes it stand out? Set in inter-war Britain. Let the story have something fresh, even unique. But not so unique that you’ll never be able to sell it.

4. Multi-book or stand alone? Multi-book, let’s say. I was in love with my idea (still am) and thought it had legs for several books. After all, I reasoned, The Entire and The Rose didn’t kill me. Right, let’s do a series. (Wait, TEATR did kill me, but distant past, distant past.)

Picky, in-depth questions.

Zooming in to more detailed questions, these are areas where changes and tweaks often occur as I write. But its helpful to have a default setting in case nothing new suggests itself.

5. What is the milieu, what is the magic about? Psi-powers have come into the world as a result of the suffering of World War I.

6. What is the story problem? A Nazi plot against Great Britain based on cold and ice.

7. What is the title? Some writers save this question for after they’ve written the novel, but I have to have it early. At the Table of Wolves.

7. What is the title? Some writers save this question for after they’ve written the novel, but I have to have it early. At the Table of Wolves.

To avoid spoilers, I’ll hide my answers to the following questions, but the considerations are still ones I use every book.

8. Who is the major character (MC)?

9. MC backstory. What makes him or her tick?

10. Who or what stands against the MC?

11.What am I trying to say? What is the point, the theme that all aspects serve in a subtle, yet fundamental way?

12. Who else is in the story and how will they add to the tension or depth?

13. In what inevitable but surprising way does the story end?

14. Who gets a point of view?

15. Who gets a subplot? This decision oftn will change as I begin to write. Actually, many answers to the “picky” questions change along the way. My first answers just give me direction, and sometimes you change direction.

16. What secrets can I lay in to fuel mysteries and major turning points?

Despite all the picky questions and (tentative) picky answers, I still need to write the story and let myself fall into the moment by moment work of the page. That’s where the real story magic happens. But for me, a little advance work woos the magic and inspires the journey.

May 10, 2016

Generating Ideas

It’s a perverted fact of the universe that writers are sometimes stumped about what to write. Give them a snappy first line in a timed writing exercise, and they jump in, keyboard clicking furiously, and then wow you with what they read out loud.

But for an original story? Um. A novel for crying out loud? Um, indeed.

Not that I’m talking about myself, you understand. Of course not.

But we shall fret no more, because there are three–count ’em, three–chances to shake loose your story ideas in a small, brilliant conference this weekend. And if there’s no way you can pack up and get to Wenatchee, I’ll close this post with an idea-generating strategy of my own.

First the conference: This Friday through Sunday. Sunny side of Washington State, nestled between Cascade foothills and the Columbia River. Fiction, nonfiction, indie publishing, traditional. Fun. First class presenters. To learn more and to register, click here: Write on the River Conference.

Among much else, we’ll have three nifty sessions on generating ideas.

Matthew Sullivan

Power Up Your Writing Imagination – led by novelist Elizabeth Fountain

Generating Ideas from Our Lives – Matthew J. Sullivan, literary mystery writer

Generating Ideas from the World – Matthew again

Join us for these sessions and others, tailored to inspire, draw out your best ideas and encourage interaction and sharing.

And my tip? Take a tour through a list of short story titles. Not for the stories, but for the titles. (Short story titles are often more creative and mysterious than ones for novels. Why? I don’t know. Maybe because less seems to be at stake, and people feel free to experiment.)

I often find my mind waking up and energized by titles. What story would *I* tell, given that title? Such as the following, but pick your own, because you’ll know which titles set you to dreaming:

The Hell Bound Train (Robert Bloch)

Scyilla’s Daughter (Fritz Leiber)

The Bagfull of Dreams (Jack Vance)

The Woman Who Loved the Moon (Elizabeth Lynn)

Unicorn Tapistry (Suzy McKee Charnas)

Wong’s Lost and Found Emporium (William F. Wu)

Pity the Monsters (Charles de Lint)

Every Angel is Terrifying (John Kessel)

Travels with the Snow Queen (Kelly Link)

All are winners of the World Fantasy Award for short story, by the way. I’m a judge this year and wow, the titles!

April 11, 2016

The Cozy Con with Big Inspiration

Robert Dugoni

What do Robert Dugoni, Agent Rachel Letofsky, and memoirist Bonnie J. Rough all have in common? A: They’ll all be in Wenatchee WA for Write on the River in 5 weeks!

Join us on the sunny side of Washington State for a day-and-a-half conference on the beautiful campus of Wenatchee Valley College. The Write on the River Conference annually attracts approximately 120 writers to learn from the experts, including New York Times best-selling authors like Robert Dugoni and Rebecca Zanetti. Sessions include:

Django Wexler

Science fiction and fantasy

How to get rep’d by an agent

Writing for the internet

Memoir

Intensive Saturday fiction class

Romance writing

Power editing your manuscript

Powering up your imagination

Indie marketing

The writing life

First page feedback from an agent

Poetry

Kid Lit

Voice in creative nonfiction

Career planning and even more . . .

Bonnie Rough

All this for $95! In addition, on Sunday, a 3 hour master fiction class from Robert Dugoni. Sunday class, $45.

We’re g0ing to have a blast. Come join us!

May 13 – 15. For more details.

Matthew Sullivan

April 5, 2016

The Door Into Scene

Scenes are the building blocks of the long story.

One simple step can save your next scene.

Even with the loosest of plot outlines, authors usually have an idea of the next thing that can happen. But there are always options. Refer to the action or insight in a narrative bridge? Bring it on stage by itself? Tuck the information bit by bit into several scenes?

“Forward the plot” is the usual scene advice. But even following that criteria it’s easy to write tepid, low-interest scenes. So how do we sort out the on-target and meaningful next sequence?

Let your intuition help

Here’s a quick way to help you open the right door into the next scene: Give it a title.

It doesn’t need to be catchy or meaningful to anyone else. But to you, it reflects the dramatic essence of this sequence. Examples from my work in progress:

Blood on the silver screen

Breaking into the sanatorium

Having to beg

To take advantage of your intuition, do the naming quickly. Does the title speak to you in shorthand, reminding you of the deep currents of your story? If so, maybe that’s the right scene–dramatic if possible, or at least inherently interesting. If you have trouble nailing the title, take it as a diagnostic warning. Or if the title doesn’t sing to you. Such as:

Nina takes the coach to town

Drowning his sorrows at Scotty’s bar

Logically, Nina might have to get to town. Or your main character might well be upset after losing his job. But these titles, if they reflect the heart of it, beg you not to bring this material on stage.

The malicious meander.

Will it hurt if you have a scene of the major character drowning his sorrows in a bottle of tequila? Yes, if nothing else happens, if the insights aren’t crucial. The coffee-cup-in-hand scene where the kindly supporting character feels badly about the major character’s setback. The instinctive title is perfect: Coffee and empathy.

Um, maybe pass on that one.

Many writing decisions lie in wait: the beats of the scene, the escalation, the pay off. But an apt title allows you to make a quick judgment of whether the next few pages will be worth the ink and the sweat.

Therefore: help yourself avoid the malicious meander and the boring plot chunk. The next time you start a scene, try giving your idea a title.

For more on scene-writing, my posts:

Writing in Scenes, part 1

Writing in Scenes, part 2

April 1, 2016

SF Trading Card Winners

You know you want to be on my newsletter mailing list (4-5 times/year) for the giveaways and insider information. Last time, I offered a drawing for cool packets of Walter Day Science Fiction Trading cards. Also, remember that if you sign up for my newsletter I’ll send you a free short story.

And the trading card winners are (drumroll here):

Thomas Morrow and bn100. Congrats to both! I’ll be in touch today to ask for addresses.

My thanks to all who entered!

March 17, 2016

A Dangerous Game of Spycraft . . .

My new series, beginning with At the Table of Wolves.

Coming from Saga Press next winter!

THE MILIEU:

England. Spring, 1936. Magic has come into the world in the form of psi-abilities. These powers have broken through in a slow, subconscious tide since 1914, brought to the surface by the suffering of the Great War. The advent of this phenomenon is called the bloom. Talents occur in perhaps one in a thousand people. The full range of paranormal abilities is not yet known, but they include hypercognition, remote view, mesmerizing, hyperempathy, darkening and the spill, with strength classified from 1 to 10. Talents come into people at various stages of their lives, especially at adolescence. People still mistrust the bloom, with its paranormal gifts, both coveted and despised. Kim Tavistock is a 5 for the spill.

The Third Reich has been working for years to weaponize these powers. Now they have succeeded in a manner no one could have guessed.

THE STORY:

Kim Tavistock, 34 years old, has the spill, a Talent that–sometimes–compels people to confide in her. They tell their secrets. It will come in handy for espionage.

Kim is passionate about England, where she was born (she was raised in the US by her American mother), and is devoted to the memory of her older brother, Robert, killed at Ypres. Because of this, she despises Nazi apologists. Her father, Julian Tavistock, has become one of these, consorting with his fascist-leaning friends, including the poisonous London hostess, Georgi Aberdare.

While the Third Reich has been working for years to weaponize Talents, England has been slow to grasp their potential threat–and promise. However, clandestine research is now under way at the ultra-secret Monkton Hall, a country estate housing researchers and testing facilities. Among the test subjects is Kim Tavistock. When she wins the confidence of case worker Owen Cherwell, he recruits her into an effort to expose the head of Monkton Hall as a German spy.

Kim’s uses her career as a stringer for magazines to go on assignment for Owen Cherwell. Her first clandestine mission is to get a spill from Georgi Aberdare at the great country manor of Summerhill. There she will meet a charming and merciless undercover German agent, Erich von Ritter, and receive from him a spill that will lead her into the heart of a ruthless Nazi plot against Britain.

From von Ritter she discovers that the plot is led by one of England’s own. Is it in fact her own father? Has he gone over to the wolves?

In WWII there were several plans to use ice as a weapon in the English Channel. What Whitehall doesn’t know is that the world will soon feel the brunt of a devastating and unguessed-at weaponized Talent. One that can force a breech of England’s finest defense: its island isolation.

Kim must penetrate von Ritter’s operation, but there is only one way in. To join him.

February 22, 2016

Aphids in the story

Have you got aphids in your story?

Aphids are today’s metaphor for repetitive and unnecessary words, paragraphs, and scenes that can suck the life out of your story. Aphids undermine the health of your story by:

Aphids are today’s metaphor for repetitive and unnecessary words, paragraphs, and scenes that can suck the life out of your story. Aphids undermine the health of your story by:

destroying the pacing

inserting flab into lines and pages

sending the plot wandering

The story may be strong in all other respects, but flab and even short detours can cause readers to grow bored and annoyed. I’m the last person who should tell you to write tight and short, since I enjoy evocative writing. However, that style is no excuse for aphids.

Look for aphids when you’re ready to revise. Adopt a hunter attitude. You’re going to kill these sap sucking little beasts. You’ll be wearing your editor hat for this task, and adopting an editor’s attitude.

Macro level bugs.

Take a look at your chapter and scene openings. Set up paragraphs showing the character traveling, arriving, and thinking about arriving are tiny little story killers. Begin in the middle of a conversation, or at least when the door is already open and the main character’s ex-wife is standing there, frowning. Aftermath sequences where we consider what just happened guarantee that nothing happens right now. Sometimes you gotta have them, but cut out most of them, or piggy back such internal narrative on scenes that do forward the action. Beware of scenes without plot or structural purpose.

Why? Again, pacing. You don’t need one big action scene after the next, but be fearless in cutting scenes when there is no mission the scene delivers.

At the story level, pacing is a tricky element to get right. Your story’s ideal pacing will be dictated by your material and the style of book you’re writing. Also, the amount of description and context will be influenced by the inherent interest of your milieu. One trick I use to grab an overview is to make a list of every scene (whether or not it’s a chapter) and state what the forward movement is, or the vital mission. I rate the scenes from 1 to 5 for conflict and tension. Too many 2s and 3s, and I can suspect pacing is an issue.

It’s easier for readers to forgive background, exposition and character portraits early on in a book,

when the author is providing context and set up for the story. But after the middle of the novel slow pacing becomes a good excuse to put a novel down.

Micro level critters.

At the line level, watch for those life-sucking little quirks that wilt lines in a hurry: liberal use of adjectives, adverbs, and just plain too many words, saying things twice, plus repeating yourself. Any good book on editing will give you cringe-worthy lists of words or syllables that are indicators of aphids at work, such as -ly, -ion, of, that, was, were.

One of the best is Ken Rand’s concise and classic guide, The 10% Solution.

The Garden as a Whole.

It’s amazing how the quality of the whole story can be undermined by things as small as habitual word choice and a few extraneous paragraphs. But when we consider the experience of the reader, isn’t it true that the pages themselves have to flourish and shine? Every page we write gives the reader either another reason to go on or reason to consider setting this one aside. At the rate people are downloading books onto reading devices, they always have something else to read. I know I do.

It’s amazing how the quality of the whole story can be undermined by things as small as habitual word choice and a few extraneous paragraphs. But when we consider the experience of the reader, isn’t it true that the pages themselves have to flourish and shine? Every page we write gives the reader either another reason to go on or reason to consider setting this one aside. At the rate people are downloading books onto reading devices, they always have something else to read. I know I do.

Pick up a page of your manuscript at random. How inherently interesting is it? How many critters lurk in the lines?

It is undoubtedly hard to rewrite. Sometimes we get revision blindness because we’re so close to the work that the critters easily hide from us.

A few diagnostic questions.

Here are some questions I use when searching for flab in my stories.

Why will anyone care about this scene? What is the point, here?

Is there enough tension in this scene? How far have I strayed from strong emotion?

Could I cut 10% from this page without hurting it? (Try it!)

Am I using a “cinematic eye”? In this movie-obsessed age, I try to remember that my novel is not a movie. In spite of the fact that I may see a movie in my head, I will never convey this movie by writing visual descriptions.

Are there opportunities to accelerate the pace after the midpoint, and then further in the book’s last quarter?

If we’ve worked hard at premise, story, and character, let’s not drop the ball with this part of the execution. The pace of your story and the experience of the reader at the line level will have a huge impact on its appeal.