Kay Kenyon's Blog, page 12

December 20, 2016

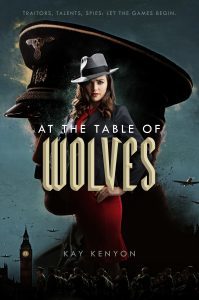

Cover release, At the Table of Wolves

So pleased to share the lovely cover of my next book, a paranormal spy novel! The book will be published by Saga Press on July 11, 2017, and is available for pre-order at your favorite e-retailers.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy meets X-Men in a classic British espionage story. A young woman must go undercover and use her superpowers to discover a secret Nazi plot and stop an invasion of England.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy meets X-Men in a classic British espionage story. A young woman must go undercover and use her superpowers to discover a secret Nazi plot and stop an invasion of England.

In 1936, there are paranormal abilities that have slowly seeped into the world, brought to the surface by the suffering of the Great War. The research to weaponize these abilities in England has lagged behind Germany, but now it’s underway at an ultra-secret site called Monkton Hall.

Kim Tavistock, a woman with the talent of the spill—drawing out truths that people most wish to hide—is among the test subjects at the facility. When she wins the confidence of caseworker Owen Cherwell, she is recruited to a mission to expose the head of Monkton Hall—who is believed to be a German spy.

As she infiltrates the upper-crust circles of some of England’s fascist sympathizers, she encounters dangerous opponents, including the charismatic Nazi officer Erich von Ritter, and discovers a plan to invade England. No one believes an invasion of the island nation is possible, not Whitehall, not even England’s Secret Intelligence Service. Unfortunately, they are wrong, and only one woman, without connections or training, wielding her Talent of the spill and her gift for espionage, can stop it.

November 16, 2016

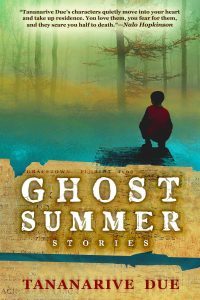

Worldbuilding with Tananarive Due

Photo by Daniel Ebon

For our concluding interview in my Ways into Worldbuilding series, I am honored to welcome a distinguished voice in fantasy and science fiction, Tananarive Due.

Tananarive Due is an author, screenwriter and educator who is a leading voice in black speculative fiction. Her short fiction has appeared in best-of-the-year anthologies of science fiction and fantasy. She is the former Distinguished Visiting Lecturer at Spelman College (2012-2014) and teaches Afrofuturism and creative writing at UCLA. She also teaches in the creative writing MFA program at Antioch University Los Angeles. The American Book Award winner and NAACP Image Award recipient is the author of twelve novels and a civil rights memoir. In 2010, she was inducted into the Medill School of Journalism’s Hall of Achievement at Northwestern University. She also received a Lifetime Achievement Award in the Fine Arts from the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation. Her first short story collection, Ghost Summer, published in 2015, won a British Fantasy Award.

Aside from reader expectations, why do you build worlds? Is it more of an obligation than a pleasure? If the latter, what is enjoyable or rewarding about this aspect?

All storytelling, to me, is worldbuilding–even if it’s our mundane world, we have to create the specific world of that character. But in terms of broader worldbuilding in my speculative fiction, since scope is not my natural strength, I am very character-focused i.e. what world would create this person? Or what interactions with the world would tell the best story for this character? I’m thinking specifically of my African Immortals series, where I was pulled out of my comfort zone in each book to expand the world for my characters. This also has bearing on my post-apocolyptic stories “Herd Immunity” and “Carriers.”

How important is worldbuilding in your stories? Is it a goal for you to create an innovative world, or do you favor having the milieu sit more comfortably in the background?

Yes, the BACKGROUND is where I’m most comfortable. When I write science fiction, especially, it’s just enough seasoning of futurism to be credible so I can tell my story–and often near-future at that.

Do you apply any sort of process to worldbuilding? How does a coherent world emerge in your work?

I write about human characters, to my first steps are built on my understanding of sociology and psychology in OUR world. “Wherever we go, there we are.” So any world I create cannot go counter to human nature. So if it’s a world with a specific kind of magic or technology, I start with asking myself why people would build this world or how they would use it.

Describe a milieu from one your works, and the aspects you found most rewarding. Which ones did readers comment on the most?

My African Immortals series is probably my most popular “world”–a sect of immortal Africans in an underground colony in Lalibela, Ethiopia. Their world involves advanced technology, telepathy, and healing blood (magic).

What kind of worldbuilding tropes are you tired of? Please share a couple of worlds that have especially impressed you.

I have seen changes in this trend, but I’m tired of worldbuilding that is exclusionary, i.e. the original Star Wars, which neglected to show a multiracial universe. Too often, aliens stand in for minority groups–and there’s no need for that, when actual black and brown people can also appear. I admire the worldbuilding in Octavia Butler, where she veers between aliens, dystopian futures and vampires to show the dangers of hierarchy and power dynamics. Her books are also always multiracial.

In a series, do you lay in mysteries, trusting that readers will be intrigued and look forward to learning the answer in later books? How do you feel about making the reader wait to learn important world features?

In my case, if a world feature pops up in Book 2 or Book 3, it’s only because I didn’t think of it earlier. **smile** But in all seriousness, sometimes I respond to questions from primary readers (like my husband, Steven Barnes) to account for features of the world that don’t quite seem consistent with human psychology, etc. If he asks, “But why are the immortals–who are mostly men–so docile in their colony?” I have to explain that later.

Do you consciously work against reader expectations for a milieu? If so, please give an example of a surprise you brought in to a familiar setting, and how successful you think it was.

I do like an almost-like-our-world in my storytelling approach, i.e. everything is like our world except this ONE small difference (though, depending on the difference, that can be hard to pull off). I don’t know how well it succeeds, but in my short story “Vanishings” I wanted to explore a world where death means the literal vanishing of the body, and “paleness” in illness means you’re literally fading away. So my story explores a family’s confusion and denial when the father never came home–is he dead, or did he run away? And how that confusion enables denial.

Any peeks you’re willing to disclose about your next world or what we might learn about the milieu in your next story?

My novel-in-progress is set in the fictitious town I explore in my short story collection, Ghost Summer, where magic exists and has a special impact on children.

___________________________

About this series. Ways into Worldbuilding is a series of interviews I conducted in the summer and fall of 2016 with sf/f writers, asking about their opinions on, and approach to, creating fictional worlds, especially fantasy worlds.

Previous interviews:

November 9, 2016

World Fantasy Award Winners

LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT

David G. Hartwell

Andrzej Sapkowski

NOVELS

* Anna Smaill, The Chimes (Sceptre)

LONG FICTION

* Kelly Barnhill, The Unlicensed Magician (PS Publishing)

SHORT FICTION

* Alyssa Wong, “Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers,” (Nightmare magazine, Oct. 2015)

ANTHOLOGY

* Silvia Moreno-Garcia and Paula R. Stiles, eds., She Walks in Shadows (Innsmouth Free Press)

Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Paula R. Stiles

COLLECTION

* C. S. E. Cooney, Bone Swans (Mythic Delirium Books)

ARTIST

* Galen Dara

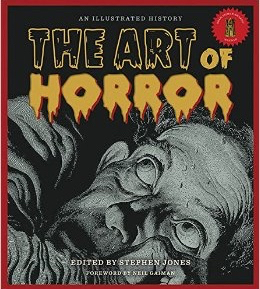

SPECIAL AWARD – PROFESSIONAL

* Stephen Jones, for The Art of Horror (Applause Theatre Book Publishers)

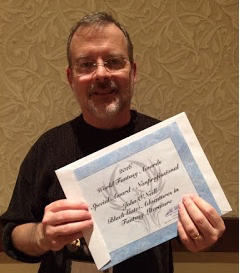

SPECIAL AWARD – NONPROFESSIONAL

* John O’Neill, for Black Gate: Adventures in Fantasy Literature

Richly deserved congratulations to all!

November 3, 2016

Worldbuilding with Sharon Shinn

This is the next to last guest post for the Ways into Worldbuilding series. I am especially pleased this week to welcome a true master of fantasy, Sharon Shinn.

This is the next to last guest post for the Ways into Worldbuilding series. I am especially pleased this week to welcome a true master of fantasy, Sharon Shinn.

Sharon Shinn has published 26 novels, one collection, and assorted pieces of short fiction since her first book came out in 1995. Among her books are the Twelve Houses series (Mystic and Rider and its sequels), the Samaria series (Archangel and its sequels), the Shifting Circle series, and the Elemental Blessings series. She lives in St. Louis, loves the Cardinals, watches as many movies as she possibly can, and still mourns the cancellation of “Firefly.” Visit her website at or see her on Facebook at sharonshinnbooks.

Aside from reader expectations, why do you build worlds? Is it more of an obligation than a pleasure? If the latter, what is enjoyable or rewarding about this aspect?

Hmmmm. I think I do it because worldbuilding is as much a critical aspect of what I write as a dead body is to a mystery. To make my stories as rich, as tactile, as complete as I want them to be requires coming up with details that illuminate the characters’ lives and placing them in settings that feel real. If I were writing historical fiction, I think I’d try to be just as detailed—because, again, I’d want readers to have a sense of being in a very specific place and time. I don’t know that I’d call this an obligation—it’s just part of the compact between the author and the reader.

I don’t know that I’d call it a pleasure, either. There are times I groan out loud when I think, “Oh no! I have to describe another room! Another outfit! Another meal!” But I’m awfully pleased with myself when I come up with a custom or a detail that I think is particularly cool.

How important is worldbuilding in your novels? Is it a goal for you to create an innovative world, or do you favor having the milieu sit more comfortably in the background?

It’s important, but it’s no more important than creating memorable characters. Actually, I would say I generally want the world to support the plot; I don’t want it to drive the plot.

Do you apply any sort of process to worldbuilding? How does a coherent world emerge in your work?

I usually start out with a couple of elements that are other. That are fantastical and set the tone for the world I’m creating. Then, as I’m writing the book, I add details to reinforce those elements. (So I’ve got angels. What kinds of clothes do they wear? Do they have to sit in special chairs that accommodate their wings? Can they swim?) As my story progresses, I sometimes have to add new elements to fit the plot, or change elements I thought were in place. Thus, it’s a very organic process, and the world tends to grow more vivid and complex as the first draft goes along. Then of course I have to go back to the beginning and harmonize all the details.

Describe a milieu from one your works, and the aspects you found most rewarding. Which ones did readers comment on the most?

Readers have seemed to really respond to the ritual of the blessings in the Elemental Blessings books (Troubled Waters, Royal Airs, Jeweled Fire). (Is this where I mention that you came up with the title for Royal Airs?) In these books, everyone is affiliated with one of the elements of air, earth, water, fire, or wood. The numbers three, five, and eight are considered propitious. There are eight blessings associated with each of the five elements, as well as three extraordinary blessings. When newborns are five hours old, their parents go to a temple and ask three strangers to pull blessings for their children, and these follow them for the rest of their lives. But people also can go to a temple at any point and draw blessings to provide guidance for that day, or for a current enterprise.

I had my webmaster create artwork for the 43 blessings and there’s a printable version posted at http://www.sharonshinn.net/troubledwaters/. I’ve started pulling three blessings every Monday morning and posting them on my Facebook page. Readers will pull their own blessings and let me know what they’ve gotten. A few readers have made their own sets of blessings by painting them on acrylic buttons, for instance. It’s been a lot of fun.

What kind of worldbuilding tropes are you tired of? Please share a couple of worlds that have especially impressed you. (Please take Kenyon novels out of the running on this one.)

I love Martha Wells’ Raksura books, which are filled with many races, none of them human, all of them complex and fascinating. Actually, generally speaking, I think she’s one of the best worldbuilders around.

In a series, do you lay in mysteries, trusting that readers will be intrigued and look forward to learning the answer in later books? How do you feel about making the reader wait to learn important world features?

I did that in minor ways in the Twelve Houses books, because I planned them as a series and I had a pretty good idea of my overarching storyline. Most of the rest of the novels that ended up being Book One of a series were not intended as series, so I didn’t have the opportunity to do so! But I actually think it’s a great strategy. Not only does it give readers reasons to go on to the next book, I think it gives them a little thrill when they reread. “Oh, I missed this before, but here’s where she first mentioned the necklace!”

That being said, I’m also generally opposed to cliffhangers in books. I want the ones I read to be complete, so the ones I write tend to be complete. Even if there’s an unsolved mystery, I don’t like it to interfere with the reader’s satisfaction with this one particular story. So I wouldn’t mind making the reader wait to learn important world features as long as the heroine’s life wasn’t at stake in the final pages because those features hadn’t been revealed.

Any peeks you’re willing to disclose about your next world or what we might learn about your latest world in your next book?

The fourth book in the Elemental Blessings series, Unquiet Land, has just come out. The heroine is affiliated with the element of earth, which seems pretty staid until you think about earthquakes, for instance.

I also have a graphic novel, Shattered Warrior, coming out in May. It takes place on a secondary world about ten years after it’s been invaded by members of an alien race, who are still on-planet. So there was a lot of worldbuilding in terms of city ruins and superimposed alien technology. I wrote out the descriptions, but the artist, Molly Ostertag, did an amazing job of bringing the world to life.

Finally, I’m working on a story I hope to turn into my next series—but since it’s still in the very early stages, I don’t think I want to describe it yet! But just as a hint, my keyword for the series is “echo.” It has been as much fun to write as anything I’ve ever done.

In what sense do you mean keyword?

Whenever I’m writing a book, before I have the title, I save my files under some word or phrase that seems apt. When I was writing Archangel, for instance, my keyword was “Gabriel.” One of the later Samaria books had “angel” as its keyword. For the current book, it’s “echo.”

The disorienting side effect to this system is that my mind often associates the keyword with a song, which is then rumbling around in my head for however many months it takes me to write the book. So, while I was writing Archangel, the Christmas song “The Angel Gabriel” followed me around for weeks. Sadly, the only song I know that includes the word “echo” is the Partridge Family’s “Echo Valley 2-6809,” so I’ve been singing that since January. It’s almost enough to make me want to rewrite the book.

____________________________

About this series. Ways into Worldbuilding is a series of interviews I conducted in the summer and fall of 2016 with sf/f writers, asking about their opinions on, and approach to, creating fictional worlds, especially fantasy worlds.

Previous interviews:

October 21, 2016

World Fantasy Con: My schedule

Excited to be leaving for World Fantasy Convention on Thursday! The programming line-up looks especially interesting. After judging the World Fantasy Awards this year, I’m looking forward to the panels on differing types of fantasy and the diverse opportunities they give us as readers and writers.

My schedule:

FRIDAY

12:00 – Panel – UNION AB

Trilogies? Small Stuff! The challenges and triumphs of writing a long, multi-volume series. What should someone starting a long series know at the outset? Lee Modesitt, David Drake, David Coe (m), Sharon Shinn, Mercedes Lackey and me.

SATURDAY

2:30 – Reading – UNION C

I’ll read from my upcoming release from Saga Press: At the Table of Wolves, book 1 of a paranormal espionage series set in the thirties in England and Europe.

SUNDAY

3:30 – Judges panel – UNION AB

Check out the full programming here.

Some of the authors who’ll be there:

Louise Marley

Lee Modesitt

Sharon Shinn

C.S.E. Cooney

October 12, 2016

Worldbuilding with Django Wexler

Guest posts for the Ways into Worldbuilding series will appear on two more Wednesdays. This latest interview is  from fantasy author Django Wexler.

from fantasy author Django Wexler.

Django Wexler graduated from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh with degrees in creative writing and computer science, and worked for the university in artificial intelligence research. Eventually he migrated to Microsoft in Seattle, where he now lives with two cats and a teetering mountain of books. When not writing, he wrangles computers, paints tiny soldiers, and plays games of all sorts.

Aside from reader expectations, why do you build worlds? Is it more of an obligation than a pleasure? If the latter, what is enjoyable or rewarding about this aspect?

For me, worldbuilding is a pleasure, indeed sometimes a guilty pleasure. I often end up worldbuilding way more than finally makes it into the book, and have to reluctantly prune out paragraphs of exposition that illuminate world details but serve no story purpose.

I think I like it because I have a deep interest in history, economics, military theory, and all the various things that go into worldbuilding. I read a lot of non-fiction, both for research and just for fun. So getting to do the worldbuilding on a new project is both a kind of puzzle — fitting pieces from different times or places together — and an opportunity to show off some of the cool stuff I’ve found. Whatever it is, I love doing it!

How important is worldbuilding in your stories? Is it a goal for you to create an innovative world, or do you favor having the milieu sit more comfortably in the background?

There are definitely many approaches to worldbuilding, but for me, the most important thing is that the world support the story you’re trying to tell. The wonderful thing about fantasy is that because you get to tinker with the world design, you get to build a custom stage to show off the story and characters. That doesn’t mean making things too convenient for them, of course, and you need logic and self-consistency. But it means you can focus on the elements that are important by leaving other stuff out of the world.

For example, when I was first brainstorming the book that would become The Thousand Names, I knew I wanted it to be a military fantasy set at an 1800s level of technology, with an emphasis on realistic battles and tactics. While I wanted it to be a fantasy, knowing that I wanted to emulate real-life military situations helped me figure out the magic system. Magic couldn’t be too powerful, flashy, or common — battle-mages like those of Steven Erikson or Robert Jordan would completely change the nature of war. (As they in fact do in those series!) So magic in The Shadow Campaigns is rare, subtle, and personal; you can use it to fight ten soldiers, but not a hundred or a thousand.

Similarly, in The Forbidden Library, I knew I wanted magic to deal with the written word, with magic books and writing playing a big role. As a result, I decided to set the story in the 1930s, before technology like photocopiers and digital displays would have opened up a whole set of new questions.

Do you apply any sort of process to worldbuilding? How does a coherent world emerge in your work?

It’s not a particularly coherent process, I must admit. First I think about the general kind of story I want to tell, and what implications that might have. Often I have something in mind as a historical parallel, or a combination of several things, so I think about how that’s going to fit and what parts of it might be changed. I try to get a handle on how magic or other differences from the real world are going to work, even if the characters don’t really understand it.

If a map is going to be important, I sketch it out at a very vague level, then drill down to a more detailed version in the places where the story actually visits. The need for this varies — I love maps, but they’re way more important in a military story like The Shadow Campaigns then in an urban fantasy story, say. Rather than total scientific accuracy in terrain, etc, I strive for a map that basically looks like maps of the real world at a glance.

Once I know who my characters are, I think about their societies and what we need to know about them. It’s easy to get carried away here and try to nail down every last detail, but for the most part you can figure out the general flavor and then make things up as you go along, not forgetting to take notes for consistency. But you’re going to need to know some large-scale stuff about social classes, gender roles, religions, languages, etc. Figure out some good swear-words, you can tell a lot about a culture by how they blaspheme.

Also, all of this is flexible! I try not to get too attached to anything until I have a detailed outline of the story. Places in particular may need to move — it’s better to redraw the map first then try to fudge later, people will notice.

What kind of worldbuilding tropes are you tired of? Please share a couple of worlds that have especially impressed you. (Please take Kenyon novels out of the running on this one.)

A lot of people complain about stale tropes, like the Tolkien races, vampires, etc. But I think any trope can be used well, and there’s no point in being different just to be different. If you call your elves “bworfs” but don’t change anything else, it’s still just as bad.

What I am tired of, though, is what I think of as “package deals”. This is when the essential aspects of some trope get tied up with cosmetic or inessential aspects, and the whole thing gets dropped into a world willy-nilly, without the author thinking about it very much. With vampires, for example, you might say the essential aspect is that they’re risen dead creatures that drink blood. (Or something else! That’s okay.) But then when you put them into your story, you import all this baggage — fangs, can’t go out during the day, garlic, crosses, running water, etc. No matter how many minor twists you then add (“My vampires hate ginger instead of garlic!”) you’ve still got a hunk of someone else’s worldbuilding, inelegantly grafted onto your own. Dwarves are another good example — underground race that crafts things, sure, but do they have to be short, bearded, axe-wielding Scotsmen?

Max Gladstone’s Craft Sequence is a wonderful example of doing these things right. He uses some pretty well-worn tropes — gargoyles, vampires, etc — but he takes the basic essence and then recasts it in light of his world and magic system, so the result feels fully integrated and part of the world. Charles Stross’ Laundry Files does a similar job integrating vampires, superheroes, and many more common myths into his unique framework.

On the other hand, you can just go wild with invention! China Mieville’s Bas-Lag books are a wonderful example of the weirdness you can throw together by not including standard-issue fantasy tropes.

In a series, do you lay in mysteries, trusting that readers will be intrigued and look forward to learning the answer in later books? How do you feel about making the reader wait to learn important world features?

I like to keep some mysteries, but I think it’s important not to cheat the readers. Basically, if our point-of-view character knows something important, you shouldn’t keep it from the reader for very long unless you’re otherwise using an unreliable narrator. If the characters and the readers are learning the deep nature of the universe together, that’s fun. If the characters already know, but just aren’t telling so that you can spring a sudden twist on the reader, that’s a cheap gimmick. (This is sometimes called “The Jar of Tang“.

Do you consciously work against reader expectations for a milieu? If

so, please give an example of a surprise you brought in to a familiar setting, and how successful you think it was.

so, please give an example of a surprise you brought in to a familiar setting, and how successful you think it was.

I do this a lot in The Forbidden Library. There’s a ton of creatures in those books, both familiar and completely invented, but I made a rule for myself that I wouldn’t use anything from mythology purely as-is. So there’s a fairy, for example, but he’s got the coloring and nasty temperament of a wasp; elves with needles for hair; and cute little kiwi birds that gather into a terrifying swarm. The dragon has eight legs and six eyes. Just little things, but it helps give the setting an alien feel instead of a familiar one.

_______________

About this post. Ways into Worldbuilding is a series of interviews I conducted in the summer of 2016 with sf/f writers, asking about their opinions on, and approach to, creating fictional worlds. Watch this space for upcoming interviews with Tananarive Due and Sharon Shinn!

Previous interviews. L.E. Modesitt, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Martha Wells, C.S.E. Cooney and Louise Marley.

October 5, 2016

Worldbuilding with Louise Marley

Guest posts for the Ways into Worldbuilding series will appear most Wednesdays through early

November. This week’s guest is the award-winning author Louise Marley.

Guest posts for the Ways into Worldbuilding series will appear most Wednesdays through early

November. This week’s guest is the award-winning author Louise Marley.

Louise Marley is a former concert and opera singer, and the author of 18 novels of fantasy, science fiction, and historical fiction. A graduate of Clarion West ’93, she has twice won the Endeavour Award for excellence in science fiction, and has been shortlisted for the Campbell, the Nebula, and the Tiptree Awards. Her historical fiction, the Benedict Hall trilogy, is written under the pseudonym Cate Campbell. She lives on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State with her husband Jake and a rowdy Border Terrier named Oscar.

Aside from reader expectations, why do you build worlds? Is it more of an obligation than a pleasure? If the latter, what is enjoyable or rewarding about this aspect?

Since my inspiration is often visual, an image that comes to my mind, I love worldbuilding. When I read, I expect to go someplace beyond the mundane world we live in, and when I write, I very much want to do the same. I yearn for different scenery, different cultures, different societies, and a touch of the fantastic become real.

How important is worldbuilding in your stories? Is it a goal for you to create an innovative world, or do you favor having the milieu sit more comfortably in the background?

Worldbuilding for me takes third place. First place is in the firm grasp of character development. Second is plot (hardest of all, for this writer.) Third is worldbuilding, which influences both #1 and #2. I often feel more free in worldbuilding than in anything else, because I can create it in just the way I like, and then adapt the characters and the plot to fit.

Do you apply any sort of process to worldbuilding? How does a coherent world

emerge in your work?

emerge in your work?

The image always comes first for me, and the practical details as I move forward. The experience I remember most distinctly was my first one, creating an ice world (The Singers of Nevya) without technology, but where people find a way to survive. I had the picture in my mind of people living in giant stone buildings set against an eternally snowy backdrop. Research showed me there had to be a thaw once in a while, and that led me to the binary star system which brought summer once every five years. Plot needs made that summer short, too short to be able to mine things from the frozen ground in order to create technology.

Describe a milieu from one your works, and the aspects you found most rewarding. Which ones did readers comment on the most?

I’ve just described Nevya, a world readers seemed to enjoy living in for a time. I’ve had a lot of comments also on the operatic and mystical world of my novel Mozart’s Blood. A number of readers have told me that my books are often their only glimpse into the world of professional music. Some readers, I confess, complained about the rules of my particular brand of vampirism. I don’t argue, naturally, but it should be noted that, as far as we know, vampirism of any brand is invented, and there are no universal rules. It was fun creating the rules I wanted, which allowed me to develop the characters I had in mind.

What kind of worldbuilding tropes are you tired of? Please share a couple of worlds that have especially impressed you. (Please take Kenyon novels out of the running on this one.)

I would have discussed Kenyon novels if you hadn’t taken them out of the mix! The Entire and the Rose . . . oh, my. The best worldbuilding I have ever read, detailed and effortless and inventive. But you’ve said no, so . . .

The tropes that bother me are the ones that are so blatantly derivative, particularly of Tolkien. I say over and over to my writing students that they have the opportunity to create their own creatures, and there’s no need to use orcs and elves and dwarves borrowed from the great master of high fantasy.

A world that impressed me deeply, and which I think was overlooked when the books first appeared, is Sharon Shinn’s contemporary fantasy world. (The Shifting Circle novels, beginning with The Shape of Desire.) I’m so weary of so-called “urban fantasy,” which evidently feel they have to include every single fantastic creature ever invented, from vampires to werewolves to dragons. Shinn’s world is a wonderful creation, just an eyelash from reality, a seemingly normal world in which shapeshifters move and survive, sometimes just a step away from being exposed. Her characters live and breathe in that unexpected environment, and I fell in love with all of them.

In a series, do you lay in mysteries, trusting that readers will be intrigued and look forward to learning the answer in later books? How do you feel about making the reader wait to learn important world features?

What has worked best for me in a series is one essential unanswered question that takes three to five books to answer. Each individual book needs its own arc, of course. Characters common to all of them are a help, since if the reader cares about the characters, they will want to go on reading to learn the entire story. A great example of that, I think, comes from out of genre. I’m a big fan of the Alphabet Mysteries of Sue Grafton. Every single book is a complete story, but readers come back again and again (twenty-three novels now, I think) in order to follow the life of Kinsey Millhone.

It’s always been my preference to allow the world features to be perceived through the characters’ eyes. I loathe info-dumps, and don’t need, as a reader, to have my story appreciation front-loaded with facts about the world. If the world is cold and snowy for four and a half years, we see that as the characters move through the story. I find that discovery part of the fun of reading a story of the fantastic.

Do you consciously work against reader expectations for a milieu? If so, please give an example of a surprise you brought in to a familiar setting, and how successful you think it was.

Returning to Mozart’s Blood, I suppose I did, only because my vampirism had different rules from the ones with which people were most familiar. I didn’t make that choice, however, in order to work against reader’s expectations, but in order to create a world in which I could tell the story I had in mind. I think it worked out beautifully, but of course, it’s the readers who have to decide!

Any peeks you’re willing to disclose about your next world or what we might learn about the milieu in your next story?

I’m just at the beginning of a novel I think we would have to call historical science fiction. As is so often the case with us writers, I have no idea how to talk about it. Describing my own work is always frustrating, but I can say that it’s related to the flurry of UFO sightings here in Washington State (my home) in the late 1940s. The research is a complete blast!

________________________

About this post. Ways into Worldbuilding is a series of interviews I conducted in the summer of 2016 with sf/f writers, asking about their opinion on, and approach to, creating fictional worlds. Watch this space for upcoming interviews with Django Wexler, Tananarive Due, and more amazing writers!

Previous interviews: L.E. Modesitt, Martha Wells, Kristine Katherine Rusch, C.S.E. Cooney.

September 28, 2016

Worldbuilding with C.S.E. Cooney

Guest posts for the Ways into Worldbuilding series will appear most Wednesdays through early November. This week’s guest is C.S.E. Cooney.

C. S. E. Cooney (csecooney.com/@csecooney) is the author of the World Fantasy-nominated  collection Bone Swans: Stories (Mythic Delirium 2015). The Nebula Award-finalist title story appears in Paula Guran’s Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy Novellas 2016. She is the author of the Dark Breakersseries, Jack o’ the Hills, The Witch in the Almond Tree, and a poetry collection called How to Flirt in Faerieland and Other Wild Rhymes, which features her Rhysling Award-winning poem “The Sea King’s Second Bride.” Her short fiction and poetry can be found at Uncanny Magazine, Lakeside Circus, Black Gate, Papaveria Press, Strange Horizons, Apex, GigaNotoSaurus, Goblin Fruit, Clockwork Phoenix 3 & 5, The Mammoth Book of Steampunk, Rich Horton’s Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy anthologies, and elsewhere.

collection Bone Swans: Stories (Mythic Delirium 2015). The Nebula Award-finalist title story appears in Paula Guran’s Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy Novellas 2016. She is the author of the Dark Breakersseries, Jack o’ the Hills, The Witch in the Almond Tree, and a poetry collection called How to Flirt in Faerieland and Other Wild Rhymes, which features her Rhysling Award-winning poem “The Sea King’s Second Bride.” Her short fiction and poetry can be found at Uncanny Magazine, Lakeside Circus, Black Gate, Papaveria Press, Strange Horizons, Apex, GigaNotoSaurus, Goblin Fruit, Clockwork Phoenix 3 & 5, The Mammoth Book of Steampunk, Rich Horton’s Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy anthologies, and elsewhere.

Do you apply any sort of process to worldbuilding? How does a coherent world emerge in your work?

One way I’ve done it is to start with a character. Who is my protagonist? What is her home life like? Is it normal for the place and time she lives in? If not, how so? What sort of town or city does her home reside in? What is her town or city’s importance to her country? (Podunk? Capital?)

How was her country founded, and by whom? Who are its gods, its scientists, its wizards, its artists, its fighters? (What does my protagonist believe in? Is she traditional? Is she in for a rude awakening?) What language(s) do its citizens speak? What are the roots of this language (and therefore of this country)?

Who are this country’s heroes? (Of these, whom does my protagonist uphold or reject? How do their legends shape her?) Who are this country’s rulers? Are they competent? Elected? Designed? Inherited? (Is my protagonist an ally? A rebel? Indifferent to politics?) What is this country’s relationship to its neighbors? How does the political climate affect this country—and therefore its citizens—and therefore my protagonist? How does her world affect her? How does she affect her world?

Now, this is not necessarily the work of a single draft. I don’t sit there and ask myself all these questions, answer them in tidy summary, and THEN write the story. Possibly I ought to!

But it’s often more organic and chaotic than that. Usually, the world emerges more resplendently with every draft I write. As the protagonist acquires depths—and a rich inner landscape—so too does her out landscape become less of a sketch, more of a 3-D to-scale model. Their evolutions interlock. The process is unpredictable and organic. So much is written that can’t be used in-text, but it’s there, influencing the text.

Describe a milieu from one your works, and the aspects you found most rewarding. Which ones did readers comment on the most?

Another way I build a world is to start with a what-if.

Sometimes that what-if ends up as an interesting but empty world, which I set aside. It might twiddle its thumbs and hum tunelessly for years—until one day, a character swaggers along, her story in a sack upon her back, and says, “So, I’m homeless and up for any adventure. What have you got for me?”

This is how I made Bellisaar (of “Godmother Lizard” and “Life on the Sun”). It began with a what-if:

What if there was a desert, like the desert I grew up in (the Sonoran Desert, in the Southwest of the United States)—but what if it also like the mythical deserts I grew up reading about (specifically, in One Thousand and One Nights)? What if there were cacti and scorpions and rattlesnakes and dust storms, but also flying carpets, talismanic gems, and small deities who’ll readily interfere in your life?

What if, like the desert I grew up in, this desert has a history of oppression and broken treaties and bloodshed? What if there are also giants? And monsters that look like people? And bureaucrats who are monstrous?

And what if there are sunsets the like of which I’ve never seen since I moved to greener lands? And what if tears, like any waste of water in the desert, are considered at best rude and at worst criminal?

I wrote pages and pages of notes. But that was for the sake of the world itself. It had no plot; not a single soul populated it. Nothing ever happened there. Maybe a coyote ate a cactus wren from time to time.

So there it sat, vacant and lonely for years—until one story I’d tried to write several times in a sometimes contemporary, sometimes near-future Dystopian Earth-setting reared its head and said, “You know what? This ain’t working. Know what else? There’s this SWORD-AND-SORCERY magazine you could submit us to. If you just gave us a sword, and some sorcery, and maybe dumped us into a SECONDARY WORLD SETTING, we could really BE something! And you DO have that weird empty magic desert just sitting there, all dusty and sunshiny. Just sayin’.”

In a series, do you lay in mysteries, trusting that readers will be intrigued and look forward to learning the answer in later books? How do you feel about making the reader wait to learn important world features?

Oh, well, as far as novels go—I’m only just finishing the first book of a trilogy RIGHT NOW! It’s called Miscellaneous Stones: Necromancer, and yes, I have very happily laid the groundwork for Books 2 and 3!

What I figured was, Book 1 is sort of “getting to know you.” We meet the protagonist, enjoy and despair at her (fairly sheltered) worldview, watch it crack apart, and—hopefully—applaud when she starts her reluctant trudge toward a strange horizon.

In Book 2, I will aim my protagonist at countries she’s only ever read or heard about. She will walk new lands with her own feet, smell new spices, eat new foods, learn new languages. She will become a Woman of the World, so that by Book 3, her actions will help shape the world—and make new history.

And the world itself will, of course, emerge for us through her eyes. I shall have to establish what that world used to be, what it is now, what it could be—how it is endangered, fragile, I anticipate an exciting, if excruciatingly slow, writing process!

In my Dark Breakers novellas (a trilogy in novellas, starting with “The Breaker Queen” and “The Two Paupers”), I strewed the ground with hints in Books 1 and 2 of what is to come. Each novella focuses on a new pair of characters, but all the characters are present from the get-go. There are also three worlds involved in the Dark Breakers’ uber-plot, and all three intersects in one house—Breaker House—modeled after The Breakers, a mansion in Newport, Rhode Island. The house is slightly different in each world: Day Breakers, Dark Breakers, and Breakers Beyond.

The city where the story takes place—Seafell—is modeled after fin-de-siècle Newport, but it’s also a fast-forward-on-the-timeline version of a city I’ve written about before, in my fairy tale “How the Milkmaid Struck a Bargain with the Crooked One” and a short story called “The Last Sophia.” So, apart from its Earthly inspiration, Seafell already has a history and myth of its own that sets it further apart from Newport, and deeper into its own niche.

Any peeks you’re willing to disclose about your next world or what we might learn about the milieu in your next story?

I recently wrote a short story called “Lily-White and the Thief of Lesser Night” for an anthology that draws its inspiration from Lewis Carroll’s “Wonderland” and “Through the Looking Glass.” But I didn’t write in EITHER of these worlds; I invented a new one, so I didn’t have to play by Carroll’s rules.

It’s called THE WABE.

I stole that name right out of Carroll’s poem “The Jabberwocky,” and also from the ensuing discussion that Alice and Humpty-Dumpty have about the poem’s meaning—which is all nonsense of course.

“And ‘the wabe’ is the grass-plot round a sun-dial, I suppose?” said Alice, surprised at her own ingenuity.

“Of course it is. It’s called ‘wabe,’ you know, because it goes a long way before it, and a long way behind it.”

My world—the Wabe—therefore, is a HUGE SUNDIAL! The villages are dotted all around the numbers. Each village a Lesser Night in addition to Greater Night. What time their Lesser Night falls depending on when the shadow of Mount Gnomon passes over them. The mountain—of course, is the time-keeper at the center of the Dial.

My world—the Wabe—therefore, is a HUGE SUNDIAL! The villages are dotted all around the numbers. Each village a Lesser Night in addition to Greater Night. What time their Lesser Night falls depending on when the shadow of Mount Gnomon passes over them. The mountain—of course, is the time-keeper at the center of the Dial.

There’s a place called Cheshiretown, where all the Cheshire Bears and Cheshire Hyenas and Cheshire Pygmy Marmosets live. And there’s a Hetch at the bottom of the Dial, who regularly mows a new Motto into the grass—always in Latin, of course. It was hugely fun to write, and I love my two girl heroes—sisters, named Lily-White and Ruby-Red.

They, of course, will grow up to be the two great Queens of Carrollian Legend. But don’t tell them that! They’re too busy having adventures to listen anyway.

Bone Swans at www.amazon.com.

____________________________

About this post. Ways into Worldbuilding is a series of interviews I conducted in the summer of 2016 with sf/f writers, asking about their opinion on, and approach to, creating fictional worlds. Watch this space for upcoming interviews with Django Wexler, Louise Marley, Sharon Shinn, and more amazing writers!

Previous interviews: L.E. Modesitt, Martha Wells, Kristine Katherine Rusch.

September 21, 2016

Kristine Kathryn Rusch on Worldbuilding

Guest posts for Ways into Worldbuilding will appear most Wednesdays through early November. Today’s post is from one of our industry’s most versatile writers and editors, Kristine Kathryn Rusch.

International bestselling author Kristine Kathryn Rusch writes under several names and in every genre she can think of. She’s won more awards for her fiction than she can count, and she also edits. Her latest editing projects are The Best Mystery and Crime Stories 2016, which she coedited with John Helfers, and The Women of Futures Past. Her next novel, The Falls, will appear in October. For more information on her work, go to www.kristinekathrynrusch.com or sign up for her newsletter.

Aside from reader expectations, why do you build worlds? Is it more of an obligation than a pleasure? If the latter, what is enjoyable or rewarding about this aspect?

I’m constantly thinking about other worlds, other times, and other cultures. A big part of my what-ifs (the source of my fiction) is: What if I was born in that country? Or in that time period? Or on the Moon in the future? What would it be like?

As a kid, I used to imagine myself into photographs—what does the air smell like? What does the ground feel like? I still have a coffee table book of photos that my parents owned. I used to stare at it all the time, imagining myself watching those people or being them.

It was great practice. I studied history to learn more about other times, and then I became a journalist to force myself out of my comfort zone. All of that informs my world-building. I can’t write a short story set in a made-up world without thinking about things that will never make it into the story.

Worldbuilding is kinda who I am.

How important is worldbuilding in your novels? Is it a goal for you to create an innovative world, or do you favor having the milieu sit more comfortably in the background?

Well, huh. The answer to the first part of the question seems very elementary to me. You can’t write about a place without knowing what it is, where it is, what it smells, tastes, feels, sounds, and looks like. That’s worldbuilding.

The second part of the question could have been in Greek, for all I understood it. Innovative? Background? The world is the world, just like our world is our world. I don’t try to make something different from other writers—that’s working out of critical brain, and that destroys fiction, in my opinion. I don’t try to make something unusual: that will just happen. Down the road from where I live, people live differently than I do. Their lives—with children, dogs, day jobs—are very different from mine. So that will seem unusual to me.

As for “comfortably in the background”? If the world is in the background, I’m not doing my job. Anyone who has been stuck in a snowstorm knows that the world is rarely background. So, I try to be very detailed, very hands-on, and very deep in the story.

Do you apply any sort of process to worldbuilding? How does a coherent world emerge in your work?

I wish I was one of those people who outlined everything ahead of time. I need to make copious notes as I go along, because I discover the world as my characters do. Often, I’ll write a novella or short story to explain to myself a part of the world I haven’t seen yet.

It’s complicated and disorganized, and somehow it works for me.

In a series, do you lay in mysteries, trusting that readers will be intrigued and look forward to learning the answer in later books? How do you feel about making the reader wait to learn important world features?

Kris’s secret of writing: I write for me.

I love mysteries and the unexplained. I’m willing to wait to find out information, so the readers are going to have to wait sometimes as well. I’ve got an entire science fiction series, set in the far-future Diving universe, that is just now beginning to answer the central mystery of the entire series, six books and several novellas in.

Those things keep me interested, and if I’m interested, I have to hope the readers will be too.

Any peeks you’re willing to disclose about your next world or what we might learn about your latest world in your next book?

Right now, I’m focusing on science fiction in the novel form, under the Rusch name. (I have several pen names.) So as I mentioned above, I’m working on a huge far-future universe that has ships and time travel and intergalactic mysteries. I’ve just finished two books in that universe, The Falls, which started out as a novella to explain something to myself, and turned into a full-blown novel in a sector base planet (something I hadn’t written about before), and The Runabout, which explores, literally, a gigantic spaceship graveyard. The Falls comes out in October, and The Runabout next spring.

But I also write historical mysteries as Kris Nelscott, and I just finished a huge project there, called A Gym of Her Own. Set in Berkeley in 1969, the book follows three women as they work to establish a gym for women. All the skills I use to build sf/f worlds, I use in the Nelscott books, because the past is gone, and I have to recreate it in full. That’s fun, and hard, and exciting to me.

As for my fantasy fiction, right now, I’m doing mostly short fantasy fiction, primarily for a series of anthologies called The Uncollected Anthology. Several other writers and I pick a topic, then write a fantasy short story based on that topic. My most recent, The Latest Madame Fortuna, just appeared in Fortune Tales. You can find it here: http://www.uncollectedanthology.com/

Speaking of worldbuilding, that’s what’s slowing me down on returning to my Fey fantasy universe. I’ve written seven books in the Fey world, and need to return for a new trilogy, but I have to put that world back in my head completely before doing so. That’s a problem with 300,000 of worldbuilding materials (set aside from those books) and big fat fantasy novels to review.

But I’m doing it, albeit slowly. I’m really proud of those books, and they’re still available. If you’re interested, start with The Sacrifice and work from there.

But I’m doing it, albeit slowly. I’m really proud of those books, and they’re still available. If you’re interested, start with The Sacrifice and work from there.

Or if you want to get one of my other fantasy novels relatively inexpensively, I’m in a storybundle with several other authors. The Epic Fantasy Bundle (https://storybundle.com) contains my novel, Heart Readers.

As you can see, I’m really busy with all kinds of projects. I haven’t even mentioned the worldbuilding in my Kristine Grayson paranormal romance and YA novels (which are going to branch toward mysteries soon), and the three witchy sisters who are magical dramaturges, whom I plan to write more about, and, and, and…

Oh, but one more thing! If you want to see just how eclectic I am, come to http://kriswrites.com/ every Monday to read a free short story. Sometimes the story is fantasy, sometimes it’s sf, sometimes it’s mystery…it varies from week to week, like my work does.

Thanks for reading! And Kay, thanks for asking me onto the blog.

_________________________

About this post. Ways into Worldbuilding is a series of interviews I conducted in the summer of 2016 with SFF writers, asking about their opinion on, and approach to, creating fictional worlds. Watch this space for upcoming interviews with Sharon Shinn, Django Wexler, Louise Marley, Tananarive Due and more amazing writers!

Previous interviews: Martha Wells, L. E. Modesitt, Jr

Next interview: Claire Cooney, September 28

September 14, 2016

Starting a novel: Granite or fun house?

Today’s post: the mental state of being at the front-end of the novel. I love the start of novels. It may be the only time I can say I am unabashedly happy as a writer. Other times I may be confidant, poised, satisfied, or happily resigned. But there is only one sequence when I am in love: At the beginning.

Other authors do not love beginnings. Mary Higgins Clark has said:

“The first four months of writing a book, my mental image is scratching with my hands through granite.”

In contrast to this–quite common, I believe–writing experience is mine:

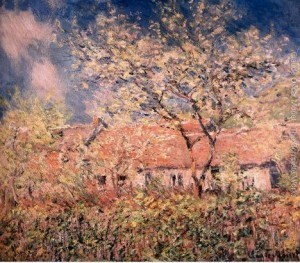

Springtime at Giverny – Monet

“The first hundred pages or so, my mental attitude is that of being lost in a fun house–no, not lost, more staggering from one wonder to another”

Once I have a general plot and I know my novel’s theme and major characters, it’s as though a door opens, and here is a world that was always present, people who have always existed, and a truth I’ve been waiting to tell. It’s the miracle of fiction writing, that the mind weaves lies which become the truest thing we know.

The first hundred pages can be tad exasperating, it’s true. There are many side paths which look germane, but which really are other books. Not this book. One might take a few steps in, and then realize, no, that’s not my story. So beginnings are largely about choices. We must choose from an embarrassment of riches. We must not gorge, indulge or be swept away by possibilities. Well, perhaps some of this on the first draft. But we know in our hearts that we must later, cut, cut, cut.

The first hundred or hundred and fifty pages are a time of intense creative fire and at times, joy. I know that I’m being shown a tremendous story, and that inevitably, I will get only some of it right. But nothing in my life quite matches the pleasure of getting to try, and watching the book come to life on the page.

And after?

Oh, that is another story. There will be granite and a small portion of boredom… Another post!

________________

Ways into Worldbuilding interview series: Stand by for next Wednesday’s interview with Kristine Kathryn Rusch!