Jose Vilson's Blog, page 22

August 4, 2016

Text of My Speech in Little Rock, AR (Decenter Yourself)

I gave this speech at the Clinton School for Public Service in Little Rock, AR as part of Noble Impact’s NobleTalks series. For those who read the last post, I deviated from this text somewhat after my visit to Central High School. Special shouts to Chris Thinnes for hearing me say this aloud in the wee hours of the night.

Good evening, class.

Thank you for having me here in Little Rock, AR.

We are living in the best of times and worst of times, but the one place that always gives me hope is my classroom.

My classroom has four turquoise-painted walls, long, tall windows, and a bookshelf that’s about seven feet high.

In the back, I keep a poster of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech, centered so every time I see myself getting tired, I can look at him with outstretched hands greeting the thousands of onlookers who are listening to him give the greatest speech of the 20th century. In the speech, he spoke truth to power by speaking to the aspirations of his people, not just his own.

Just to the left of that poster is a huge bulletin board dedicated to our lives mattering, images and quotes from the current street movement, one which I’m still learning from.

In my classroom, a typical student might ask, “Mr. Vilson, what’s the answer?” I tell them, “I don’t know.” They’re visibly frustrated, and they ask again, “What’s the answer?” I tell them, “I don’t know.” They get mad some more, smoke coming out of their little ears, and they ask, “Yo, Vilson, what’s the answer to this?” To which I reply, “I don’t know.” continue reading

The post Text of My Speech in Little Rock, AR (Decenter Yourself) appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

August 1, 2016

Between Little Rock and This Hard Place

“She wasn’t with the rest of the other Black students. Can you imagine having all those harassers, reporters, and guards blocking her from letting her get into school?”

As I was listening to the ranger tell us the story of Elizabeth Eckford’s first day of school at Central High School in Little Rock, I found myself zoning out.

In a few hours, I’d be telling an audience of mostly white educators, business leaders, and students that they need to incorporate a sense of activism in their approach to loving and showing compassion for our kids. I had been nervous about this event because of the breakneck schedule I’d undertaken to get there.

Flight delays. Cancellations. Maintenance issues. Broken laptops. Snapped watches. Erased notes, remarks, and slides. Too many “first world” problems in a 48-hour window.

Our first morning in Little Rock, AR started with a casual breakfast and a visit to the Clinton Presidential Library, courtesy of Noble Impact and the Clinton School of Public Service. My poker face didn’t give much away in terms of my aforementioned issues or the critical thoughts triggered by different renditions of the 42nd president’s legacy in this country. Instead, I let the experience just be.

After lunch, I felt this nervousness about my remarks. Would my words make sense? Do they matter? Will they spark someone to change direction or embolden them to follow the harder path? Could I deliver them with the right level of urgency and passion that they’d understand how much this all means to me? continue reading

The post Between Little Rock and This Hard Place appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

July 29, 2016

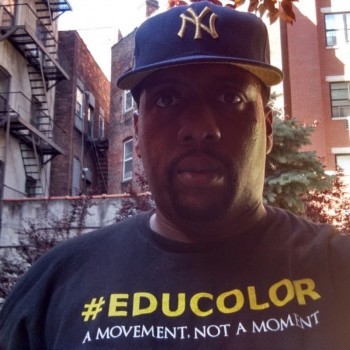

A Quick Note on Race Talks in Education Spaces #EduColor

Premise: educators who aren’t challenged to think about systemic inequity offline don’t want to think about it online.

In the last week, much has been made about my impromptu #educolor chat about race and schools, but, like #EduColor itself, it wasn’t borne of a chat, but by resistance to ignorance amongst our colleagues.

You can read the recap for yourself here.

Behind the scenes, I had contemplated whether I even wanted to participate. There were pros and cons to both. The main con was that connected folks of color shouldn’t have to participate in this chat because white educators should do the work themselves without our involvement. This puts the onus on white folks to talk to white folks about race in a space that normally doesn’t do it.

But as I watched it unfold, I started to see how few participants either wanted to engage. In fact, the folks who were originally energized by the topic started to drop out quickly as they saw how quickly some #edchat participants deflected any attempt at critical thought. None of the moderators wanted to take any particular responsibility for the historical negligence of this topic.

The post A Quick Note on Race Talks in Education Spaces #EduColor appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

July 20, 2016

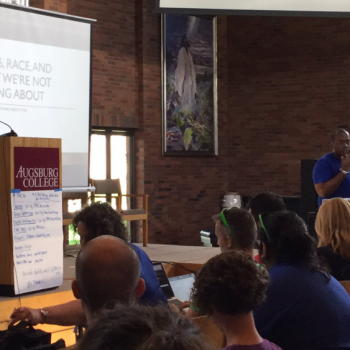

Twitter Math Camp and the Convergence of The Work

This weekend, I had the pleasure of attending Twitter Math Camp 2016, a conference organized by the collective known as MTBoS. As the name suggests, this set of social-media-connected math teachers created a conference where they could network, have deep conversations, and share ideas about pedagogy, curriculum, and content. Even though I’m technically part of this collective as a veteran math teacher who’s been on Twitter since June 2008, I’ve felt disconnected from this community for some time. I set aside my protractors and pocket protectors for raised fists and black wristbands.

Yet, the entire time, I thought if I held my breath long enough, the folks in that community would inch themselves over to my arena, even if just to take a peak.

The culmination of said efforts happened when they invited me to come speak. I take all speaking engagements seriously, but this one felt meaningful for two reasons:

Minneapolis was already a site of civil unrest after the murder of Philando Castile.

With 200 attendees, I was reminded on several occasions how excited people were to hear me speak.

I almost wanted to respond, “You know this is a package deal, right?” I’m going to speak on Black lives mattering. I’m going to speak on under-served to Native American / First Nations children across the state of Minnesota. I’m going to tell math people to do more than talk about math. I won’t swear, but I will call this conference and its participants white. White people feel some sort of way about being called white. I will not mistaken professionalism for conservatism, so my truth is my truth.

And these folks still said, “yes.”

And because I was the first keynote, because I am still a math teacher, because I needed them to do the work with me, I still said, “Thank you.”

Math teachers, contrary to our own beliefs, already have parts about us that allow us to engage in difficult work. Conversations about math and identity aren’t all that different if we establish principles:

Math teachers ask critical questions of themselves and others. Depth matters here.

Math teachers prepare for teachable moments. We need to be nimble when complicated questions come up.

Math teachers expect non-closure. We won’t solve all of the problems all of the time, but, with the right approach, we can tackle it meaningfully.

Math teachers stand on principles of inquiry and openness. If we keep asking and keep ourselves vulnerable to not having the right answer, we do better in these conversations.

Math teachers allow for multiple pathways. We won’t all arrive at the same methods for how to tackle any one thing, but we can allow for multiple ways of getting to the ultimate goal, especially if other people can learn and understand these other methods.

I know I’m abstracting, and that’s purposeful. Often, when critical conversations arise, people shy away from them, hoping their friends have the answers, or that someone else is going to solve the problem. But if those of us who already solve complex math problems can’t use the same tools to solve complex world problems, then why do this work?

That’s my nervousness. I prompted the audience to ride with me on the ideas of cultural competence and social justice because I believe in their intention of bringing me there. For so many of our kids, none of this is adding up. We had a whole room of people who can push back and say, “Well, here’s a start.”

The post Twitter Math Camp and the Convergence of The Work appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

July 10, 2016

The Classroom Next Time (On My Last Day of School)

Over the last week or two, I’ve had a hard time compressing the experience of teaching students over the last year. There’s something disconcerting about teaching 90 students in the beginning of the year to 150 in almost in the blink of an eye. Yet, that’s what happened in December.

But before I speak on that, you should know the intense preparation I undertake to begin the school year. I hop in more than a week early, scrubbing desks, emptying lockers, labeling baskets. I re-order books, wash whiteboards, and toss out scrap material from the prior year. I order multi-colored folders, boxes of pencils, and reams of copy paper. I go through routines and rituals as if they were seated right in front of me then and there. I skim over lesson plans and quotidian First Day of School posts. I test out my teacher voice and blast inappropriate rap music at high volume while doing all of this. I become one with this classroom, the space my students might occupy.

In short order, they are introduced to adults left and right, some who they’ve passed by in the hallway but never bothered to inquire about. Their schedules have rectangular grids with enough space in the text to color-code with fresh neon marker. They’re given a redundant set of behavioral norms. They read their teachers for initial signs of weakness and codes of engagement. Who gives the most homework? Who shouts the loudest? Who’s too strict for their own good? Who’s going to give me that 90?

Meanwhile, I had re-dedicated myself to aligning my inside and outside personas, because I already carried so many multitudes that having one more grew tiresome. My students deserved this new me. The political self. The soulful self. The ebullient self. The serious self. The quixotic (and at times sarcastic) self. The fatherly self. In full display. From day 1.

We uncovered rules of exponents in September, explored the measurements of the solar system through scientific notation in October, and applied patterns to linear relationships in November. The students never grew weary of asking me questions, and I had enough willpower to prevent myself from giving direct answers. I stuck to this principle. All the while, students in a couple of other classes heard about my reputation and wanted to opt into my class.

They got their wish, unwittingly, when adults thought it best to have me teach 145 students and not 85, 5 classes instead of 3. They saw to it that 5/6ths of the entire eighth grade would have me for half of their math program. For two of my original classes, it meant resenting their other math teacher. For another two, it meant resenting me. For the fifth class, it meant picking sides over the better math teacher. For the adults, it meant sharing students and having critical discussions about their conceptual understandings.

But for me, it meant too much. It meant allaying the fears of students who were only used to me as their math teacher. It meant having stronger relationships with the classes that naturally came in during September versus those that abruptly came in December. It meant at least three different approaches and lesson plans, and a load that didn’t match with my concepts of middle school. It meant questioning some of my colleagues and pushing them to care about my kids as much as I did. It meant my paper stacks were that much higher. It meant my quizzes and performance tasks took that much longer to give back. It meant new colored folders and different seat arrangements every 45 minutes instead of every 90. It meant a sore throat by seventh period daily, and a new set of parents to call and inform them of our new complicated system. It meant digging deeper than I ever did to make all of my students meet the standard I had originally set in September.

From a bird’s eye view, it also meant I was entrusted for 45 minutes a day with ~80% every eighth grader academically and socioemotionally, a burden I gladly bore.

To what end? I witnessed scholars, think tank occupants, hustlers, and bosses hypothesize all of the ways educators, parents, and students don’t teach, don’t cultivate, don’t learn. Their all-students-matter rhetoric belie their distance from the day-to-day lived experience of those who’ve chosen this path. An even slimmer road exists for those of us who chose to adjust ourselves on behalf of students, disregarding the current urge to call children a digit or a state-sponsored label. Some educators traverse a thinner road still, one that spiritually connects students’ plight with their hopes, their ears, and their hymns.

In acknowledging this, I sharpened my foci on them as people. Their 90+ average does not make them impervious to racial, sexual, or class-based oppression. Their 55s do not make them incapacitated to greatness, love, and compassion. Elevated test scores are nice to have, but their scores are slivers of their capacity for learning. Their manners and mannerisms, their shoes and lowered pants, their hair and loud laughter are inextricable, ever movable parts of their actual person.

I threw my whole heart into this and laid my flaws out because the world that analyzes them, judges them, corrects them lost its heart somewhere in the footnotes of their ill-conceived policies.

On the last day, I told my main class many truths. Some folks will care whether they learned. Some won’t. Some folks will love them. Some won’t. They only had to be steadfast in their self-determination, and they must grip firmly their resolve. They need not worry about being loved because they already have people who love them. Including me. They were a wonder before they walked through my class, and I now joined in the wonderment.

This year, I didn’t take into consideration whether they would be college and career ready. I simply asked them to consider being their best selves daily. As I tried. I failed lots, but I continue to succeed more often than not. I needed for them to burn brighter than I did.

That’s the blessing.

The post The Classroom Next Time (On My Last Day of School) appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

July 5, 2016

The Kids Can’t Read, But They Can Read You

When I was seven years old, a frio-frio man used to park his cart in front of our elementary school in the spring and sell his Italian ices for 50¢ for 2 scoops. Whenever my mom had enough change, she’d give me two quarters and I’d treat myself to the street delicacy. At the time, a counselor from our now-defunct after-school program picked me and my friends up from school. Even though I was from the hood, my mother rarely let me delve too deeply in the ways and means of the hood for fear that I’d get involved in hood life the way my cousins did. I was the smart one in the family, and those same cousins forced me out of the shady spots to keep my nose in the books.

One eventful day, the frio-frio man fielded 15 kids at once, all clamoring for their icey before the kids from the school across the street swooped in. In a hurry, I stretched my hand out with two quarters. The man took it and never gave me my order. I went directly to my counselor and told him what happened. He then proceeded to yell a few Spanish words for stealing my money and demand that I get my helado. I smiled for a few minutes, but before I could take my first taste, the counselor turned around to me and said, “How can you be so dumb and give him your money before getting your icey? Pay some damn attention and make sure you get yours!”

Lesson learned. Reading doesn’t just matter in the school, but outside as well. continue reading

The post The Kids Can’t Read, But They Can Read You appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

June 26, 2016

Ralph Wiley and The Next Level of Education Writing

College was the first time I was exposed to higher-speed Internet. Aside from downloading gigs of music in a matter of seconds, I had the opportunity to read every and any article on the web without worrying whether a phone call would disrupt my access to it. ESPN’s now-defunct Page 2 was always one of those sites. Yes, it had its share of hyperbole, as every post-Y2K moment had to be ranked and re-ranked almost weekly.

But it also gave me Ralph Wiley, one of the best writers I’d ever read in my life.

I didn’t understand the mechanics then, but his blend of fact-based argument with conversational flow read like some of the hood intellectuals I’d heard talk sports all my life. The sentences in his essay would cut through the same points through different angles. Imagine a well-made pizza and the chef using short slices, pushing his forearm into the pie with force and brevity. Observe Wiley’s thoughts on now-retired NBA legend Kobe Bryant:

“So a human thoroughbred starts to think about spitting the bit and running elsewhere, where whips and chains and self-important appraisals are not so often forthcoming, for a man without a temper is not worth his salt. Or, if he’s Kobe the Finisher, he can also become Kobe the Puppet Master, and let people rant or rave or do St. Vitus’ dance however they chose as he pulls the strings and levers of his dominant basketball talents. I’d like to see what Charlie Kaufman could do with this guy’s head. In an Association with at least eight other truly great players, and a good 50 or so who can drop 40 on a given night, Kobe rules. As yours truly pointed out in GQ last summer, days after the Lakes had won a third straight NBA title, if Kobe’s hands were as big as Michael’s, they’d have to shut down the league.”

The post Ralph Wiley and The Next Level of Education Writing appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

June 19, 2016

Choosing A School For My Son In A Segregated State (A Reprise)

A few weeks ago, I attended my son’s prospective school’s fundraising fair in their backyard. They had the standards: a bouncy house, a ball toss, a face-painting station, and a plastic frog pond. They also had some unique features: a DJ that played Black music standards like Shalamar, Michael Jackson, and James Brown, a raffle for a dinner voucher at Sylvia’s, a principal in a smock running around with the kids and parents in a playful manner. As first time pre-K parents, we’re nervous for Alejandro, a boy who already counts to 100 and reads Dr. Seuss with clarity and regularity. Academically, he’ll be fine. His mother is an assistant principal and thoughtful educator. His father has taught for 11 years and waxes poetic about the latest education research and its ramifications for a well-read blog. He’s supposed to be fine.

But our question was, will the teachers like him?

I read Nikole Hannah-Jones’ latest piece shortly after the school fair. This article focused on the confluence between her work as a reporter for the New York Times and her daughter’s schooling threw tapped every nerve possible. In my mind, I’ve played Nikole’s words in my mind while trusting my child to Mayor Bill de Blasio’s UPK program. I believe in social justice. I believe that the choices each of us makes for our child affects other children thereafter. I believe my child will be alright regardless of what school he goes to. I don’t think public schools are all that public, but, as fate would have it, I live in the middle of Harlem / El Barrio, the heart of some of the most well-known – or notorious, depending on who you ask – charter schools in the country, from Eva Moskowitz’ Success Academy 1 to Geoffrey Canada’s Harlem Children Zone. Not only did I openly resist these school options, I even winced at the Catholic school options. As a Catholic school graduate, I hoped that the schools we chose had open spaces, creative pedagogy, and a loving environment for Ále.

We’re trusting these institutions with our child. continue reading

The post Choosing A School For My Son In A Segregated State (A Reprise) appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

June 16, 2016

What It Means To Speak Truth To Power (About That Medium Post)

The whole point was to speak truth to power. 20,000 views later, I don’t know what to do about the new eyeballs on my writing.

In subsequent tweets, [Perry] comes within inches of calling himself the next Messiah, stopping kids from stuttering and pulling them from gangs, stepping in for their absent fathers, and keeping them up until midnight for no other reason than his own need to set these boys straight. In subsequent tweets, he shouts down tweeters who resent his anti-Black message, chiding him for implying that dreads and braids?—?hair styles with African traditions?—?make black boys look dirty and, worse yet, unsuccessful. He continues to use this weekend experience of setting boys straight (yes, like the jail, but only with a comedian and an army veteran) to make other wild assertions about the American school system and absentee fatherhood. He admittedly spends 29 tweets extolling the virtues of depriving boys their sleep and cutting their natural hair to detractors, then makes an about face to chastise “y’all” for spending time on Twitter instead of getting to work.

How do you lead an education revolution when your ideas are so revolting?

I didn’t intend on focusing on any one person or restarting the same old education debates. As is my annual tradition, I just wanted to put the conversations so many of us put in our private messages out there for non-educators to see. For a classroom teacher who’s been doing this for 11 years, I’m fascinated by the plethora of critique that I either a) write hit pieces or that b) I have no solutions. The bulk of my work has been largely to find solutions in the murkiest, most complicated spaces. continue reading

The post What It Means To Speak Truth To Power (About That Medium Post) appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

June 13, 2016

On Latinos in Education and America

A few days ago, I had the pleasure of attending Soledad O’Brien’s I Am Latino in America event, a tour featuring some of the most prominent Latino leaders in entertainment, politics, and yes, education. None of O’Brien’s features, from the seminal Black in America to the series of other CNN programming aimed at specific groups, present anything new per se, but they do feature different facets of what it means to be [insert given identity]. So, as a Black Latino (Afro-Latino, if you must), I was struck by hearing the younger folks like poet Denice Frohman and comedian Vladimir Caamaño to the established figures like actor Rosie Perez and musician Willie Colon giving their honest visions for the work they’re doing.

Of course, NYC schools chancellor Carmen Fariña and National Education Association (NEA) president Lily Eskelsen Garcia were there, too, thus my interest in this event.

As Ms. O’Brien highlighted, education is the #1 issue among those who identify as Latino, not immigration, according to a recent poll. Yet, the only issue most major news networks have hung like a carrot on a stick for Latinos is immigration. Shorter version of this election with respect to Latinos:

Trump: “We’ll kick you out of here and build a wall behind you.”

The Democrats: “We’ll keep you and … we’re still trying to figure out the rest.”

The back and forth between Sanders supporter Rosario Dawson and Hillary Clinton endorser Dolores Huerta stands to accentuate a generational divide. But, even though both exclude Donald trump from their framework for Latino empowerment, it also illustrates the majority of Latinos who have disparate views on every major political issue. If one listens to the talk out there, you don’t get the richness of the conversations happening online, at dinner tables, and, yes, in our schools. continue reading

The post On Latinos in Education and America appeared first on The Jose Vilson.