L.E. Carmichael's Blog, page 23

December 22, 2019

A Long Winter’s Nap

As the holiday season kicks into high gear, we’re going to take a brief hiatus here on ye olde blog. The blog-mistress is in dire need of a nap, and she’s willing to bet a lot of you are, too.

As the holiday season kicks into high gear, we’re going to take a brief hiatus here on ye olde blog. The blog-mistress is in dire need of a nap, and she’s willing to bet a lot of you are, too.

Wishing you all a healthy, happy, restful holiday season. Regularly-scheduled content returns January 6.

December 16, 2019

The Mad Science of The Lion King

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

Despite swearing off of live-action-remakes-of-Disney-movies-that-really-didn’t-need-to-be-remade-to-begin-with, Tech Support and I recently watched the new version of The Lion King. Which isn’t even “live action” so much as “slightly more advanced animation,” but whatever.

I have mixed feelings. On the one hand, many of the things I loved about the original are there – so many, in fact, that I once again question why Disney even bothered. On the other hand, of all the things to decide to cut, they go with “You can be a big pig, too?” Tech Support and I sing that song practically every time we eat bacon, because we are classy like that.

I was also a little disappointed that one of the things Disney kept was the portrayal of the hyaenas. Not so much from a standpoint of racism, a criticism that others have levelled against the original film. Nope, I’m talking about hyaena biology.

Disney’s hyaenas are lazy, destructive, scavengers that have to be excluded from the Pride Lands in order to protect the delicate balance of the neighbourhood.* Once Scar lets these mangy minions into paradise, the Circle of Life goes distinctly pear-shaped.

Here’s the thing, though. In the real world? The lions are great big bullies, stealing food from the hyaenas and often making the smaller hyaenas into snacks. Some studies show that hyaenas have to outnumber lions six to one to have a chance of protecting their prey, and that’s only if the lions in question are actually lionesses and youngsters. If we’re talking full-grown male lions, hyaenas just have to stay out of the way and hope they can cage some leftovers from their own kills.

Not only are hyaenas not evil, they are actually pretty cool critters. Yeah, they look a bit like they were made out of spare parts, and the sounds they produce are a tad on the creepy side. But they are pack animals, like wolves, that use communal hunting strategies and pup-rearing techniques. This is pretty helpful in an environment where many prey species are fast moving and migratory, meaning hard to catch. Hyaenas have some other completely fascinating quirks, too, which you can read about here, provided that frank discussions of animal anatomy and behaviour are a thing you are up for.**

Also? Hyaenas are matriarchal. Forget Mufasa: if lions were hyaenas, Sarabi would be in charge. Granted, Disney made Shenzi the leader of the gang, so credit for getting that part right, but it’s another reason why real-life hyaenas are interesting and worthy of a respect the film doesn’t offer them.

How do you feel about Disney’s hyaenas – or the real kind? Did you like the remake, or would you rather Disney, I don’t know… write something new? I’d love to hear from you!

*Hmm… that really does sound a little racist, doesn’t it?

**You’ve been warned.

December 9, 2019

Teach Write: Lab Reports and Scientific Papers

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

If you’re new to this column, we’ve spent the last couple months talking about the influence that our intended audience has on the way we approach a piece of writing, and now we’re discussing purpose – the goal of a piece of writing, and how our intention as writers affects format and style. And what better place to start than lab reports and scientific papers, two closely-related forms that I have extensive personal experience with, what with that whole being-a-scientist thing.

Lab reports and scientific papers are documents that describe experiments. They both follow the IMRAD format:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results and

Discussion.

Depending on the field (and perhaps the journal you hope to publish in), these sections can be split or merged. For example, sometimes Results and Discussion are combined, and sometimes a Discussion section will be split so there is a separate Conclusions section at the end of the paper. An Abstract, which summarizes the most important points of the paper in a single paragraph, might also be included prior to the introduction. More on these sections later. For now, let’s return to purpose.

In this case, the purpose of the paper is a reflection of the audience for each paper. Lab reports are written by students for their instructors. As a result, the purpose of a lab report is to:

demonstrate to the instructor that you understand what sections an IMRAD paper is supposed to contain, what goes in each section, and what the tone should sound like

demonstrate to the instructor that you actually understood the point of the experiment, most often an experiment that’s been done a lot of times by a lot of people before you.

Generally, you’ll be doing that while assuming that your primary audience is actually students with your level of experience, so you’ll be including information that your peers would need to know in order to repeat your experiment, and omitting stuff they would think is obvious.

In contrast, scientific papers are written for other professional scientists. Your purpose, therefore, will be to:

describe brand new results from research no one’s ever done before

explain any new materials or methods that you developed in order to do your experiments

prove that your methodology is appropriate to the question you’re trying to answer, meaning

your results are accurate

your conclusions are supported by data.

So, while you’ll be following a version of the IMRAD format no matter which document you’re writing, you can imagine that you’ll need to approach the actual writing quite differently.

We’ll take a closer look at each of the sections of an IMRAD paper in later instalments. In the meantime, one of the best ways to get a sense for the differences between lab reports and scientific papers is to read some! For papers, read journals in the field of study you’re working in. For lab reports, ask your instructor for examples. The science section of Afficio, a journal of award-winning undergraduate university papers, is also a great resource.

December 2, 2019

STEMinism Sunday: Dr. Patricia Bath and the Fight for Sight

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to get to know some of these intellectual badasses.

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to get to know some of these intellectual badasses.

I learned about Dr. Patricia Bath – ophthalmologist and laser scientist – while researching my children’s book, Innovations in Health. Of all the people I profiled, she’s one of my favourites. Bath was not just a woman in science, she was a woman of colour in science. Because she began her career in the 1970s, she faced even more discrimination and condescension than women of colour in STEM fields continue to experience today. In fact, working conditions in the USA were so bad, Bath transferred to a university in Germany, where her colleagues were more willing to let her get on with her ground-breaking research.

Some of the work she did there resulted in Laserphaco. Before Laserphaco, doctors removed cataracts with scalpels or drills. Bath’s device removed them using lasers – a method that was both safer and more precise. To me, the most interesting thing about Bath’s invention was that she first had the idea in 1981, but she couldn’t actually build the device until 1986, because laser technology wasn’t advanced enough! She also became the first African American woman doctor to receive a patent for her invention.

Laserphaco was just one of the ways Bath combated blindness. Come back January 27, 2020, to learn about the others!

Do you know anyone who’s had cataracts or laser eye surgery? Does the idea of a drill in the eyeball squick you out as much as it does me??

November 25, 2019

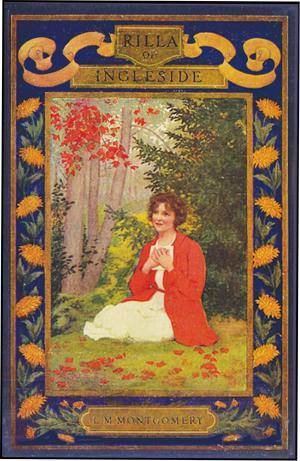

Cantastic Authorpalooza – Melanie Gall Reflects on L. M. Montgomery

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by great Canadian children’s writers! Today, something a little different – my friend, author, actress, singer, knitter, and all-around-amazing-talent Melanie Gall, discusses one of our favourite books, by legendary Canadian author L. M. Montgomery.

Take it away, Melanie!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by great Canadian children’s writers! Today, something a little different – my friend, author, actress, singer, knitter, and all-around-amazing-talent Melanie Gall, discusses one of our favourite books, by legendary Canadian author L. M. Montgomery.

Take it away, Melanie!

Tribute to a Classic: Rilla of Ingleside

Rilla of Ingleside is the eighth and final book in Canadian Author L.M. Montgomery’s iconic Anne of Green Gables series. It was published in 1921 (13 years after the series’ first novel), and three years after the novel’s central theme, the ‘War to End All Wars’.

Rilla is marketed and sold primarily as a book for children, but it is so much more than that. This book is the only Canadian work of fiction which represents the personal experience and wartime struggle of the ‘Soldier Girls at Home’ – the Canadian women who stayed behind while their men crossed the sea to fight. Rilla of Ingleside is a gem of a book, because it manages to encompass painful and difficult personal wartime experiences, while still essentially remaining a sweet, charming piece of literature.

It would be fascinating to address the many different wartime themes that were worked into what is essentially a simple story of one girl’s coming of age: The mirroring of Anne’s daughter Rilla’s awakening to adulthood with the awakening of her sleepy town (and, in many ways, the entire country), when faced with a global conflict. The personal struggle many young men faced when, as pacifists, battling their personal beliefs was just as difficult as the actual physical battle they were sent to fight. The heartbreak of women whose sweethearts perished overseas who – since they weren’t actually widows – had to suffer a grief that was not considered ‘real’.

This is a book you should read. Seriously, read the book, preferably after reading Rainbow Valley and Anne of Ingleside, which introduce secondary characters who are central to Rilla’s plot.

This is a book you should read. Seriously, read the book, preferably after reading Rainbow Valley and Anne of Ingleside, which introduce secondary characters who are central to Rilla’s plot.

For this analysis, I would rather address the representation of the author’s personal life in this work. L.M. Montgomery did not have an easy life – she was raised by her grandparents, which was followed by an unhappy marriage and a life of isolation in Toronto, thousands of miles from her beloved Prince Edward Island. However, Montgomery’s literary works generally seemed to be in direct contrast to the personal challenges she faced

Rilla of Ingleside was a notable exception. Written just after recovering from the Spanish Flu pandemic which killed almost 100 million people in a single year, this novel feels more personal than any of her other works (including the Emily series, which are often seen as autobiographical). At the time she was writing the book, L. M. Montgomery was sick, and tired, and struggling with duties of motherhood, church life, as well as with her husband’s endogenous depressive disorder. The world was still reeling from a war that had killed almost a generation of sons, and Montgomery herself was trying to reconcile her own religious beliefs with her disillusionment with World War I and her guilt at her initial ardent support for the war.

Rilla’s dedication reads: “To the memory of Frederica Campbell MacFarlane, who went away from me when the dawn broke on January 25, 1919—a true friend, a rare personality, a loyal and courageous soul.” Frederica, who died in the flu epidemic, was Maud’s inspiration for Anne’s ‘bosom friend’ Diana in the earlier novels. This dedication starts a book where Maud’s struggle and exhaustion is present throughout.

A central figure in both Rilla of Ingleside and the earlier novel, Rainbow Valley, is the Piper. The piper is inspired by an actual piper who had marched through the center of Leaskdale, Ontario daily for all four years of World War I, playing Highland war tunes, to inspire young men to enlist. In the books, it is a thematic embodiment of the Pied Piper of Hamlin, seen in a vision by Anne’s son Walter as someone who would lead the youth of Canada to a noble purpose. When this theme is revisited in Rilla of Ingleside, the Piper is more sinister, luring men to their deaths.

Another reflection of Montgomery in Rilla of Ingleside, is through the character of Anne. In so many ways, her actions and reactions mirror Montgomery’s wartime experience. Montgomery volunteered, wrote essays, and was constantly busy on the homefront. And in Rilla:

“Oh, let me work—let me work, Gilbert,” Anne entreated feverishly. “While I’m working I don’t think so much. If I’m idle I imagine everything—rest is only torture for me. No, I cannot rest—don’t ask it of me, Gilbert.”

In the earlier books in the series, Anne goes through various trials (including the infant death of her first child). She remains a resilient, inherently positive character. However, when personal tragedy befalls Anne in this final book, she collapses, spending weeks “[lying] ill from grief and shock.” This physical collapse reflects both Montgomery’s emotional distress from the war, as well as her physical collapse from Spanish Flu.

Throughout most of Montgomery’s books, Prince Edward Island was seen as an idyllic place, a happy and secure world that was not affected by events on the outside world. In Rilla, Montgomery references her own awakening, acknowledging that her idyllic island, her “Rainbow Valley”, has been irrevocably changed.

Rilla of Ingleside is an often-underestimated novel that can be approached on so many levels, and it is a fascinating and relevant piece of Canadian history that should not be forgotten.

Thank you, Melanie, for this tribute to a book we both adore! If you’d like to learn more about Melanie and her work, check out her recordings of wartime knitting songs – Rilla and the other women in the book spend much of their time knitting socks and scarves and sweaters for the men at war. And if you can, see Melanie during one of her live performances across the globe!

November 18, 2019

Mad Scientists of Stranger Things: Part IV – Mr. Clarke

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

Did you miss the previous instalments in this series? Check the archives for posts on Martin Brenner, Sam Owens, and Dr. Alexei. Today, we’re talking about my favourite character, never mind scientist, in all of Stranger Things: Mr. Clarke.

Mr. Clarke first appears in S1E1, and the very first thing he says is that experiments are not the only form of scientific investigation. Thank you, Mr. Clarke! My entire PhD* is a work of observational and descriptive science, so I was thrilled to see this guy define science in a far more open and inclusive way than a lot of real-life people do. If that weren’t enough, though, we also get this conversation between Hopper and Clarke in the woods:

Hopper: I always had a distaste for science.

Clarke: Well, maybe you had a bad teacher.

This is a thing that scientists, like writers, get a lot of – other people not understanding, liking, or valuing what we do. But Mr. Clarke knows the truth: science is COOL. Our perception of it is defined by how we’re exposed to it. If we’d all had science teachers like Mr. Clarke, the world would be a much better place.

Mr. Clarke takes kids, and their questions, seriously. If you ask, he will take the time to answer, even at 10PM on a Saturday. He helps his students open any “curiosity door,” a phrase I adore, no matter how random or seemingly bizarre their interests. Mr. Clarke loves the wild and weird, but unlike some of the other scientists in the show, he tempers his love of knowledge with compassion and morality. For Mr. Clarke, people come first. And not just his students.

In Season 3, Mr. Clarke helps Joyce figure out why her magnets are falling off her fridge – a question pivotal to the mystery. Unlike everyone else in Hawkins, who treats Joyce as irritating or unhinged, Clarke helps without hesitation. He doesn’t need to know why she’s curious to see her question as worthy of consideration. And hey, any excuse to build an electromagnet in the garage, right? Clarke’s delight in the power of science is both genuine and humble–he loves science for science, not for what it might give him.

Mr. Clarke isn’t just my favourite character. As Stephanie Garrison argues in this article, I believe he’s the real hero of Stranger Things. He doesn’t have El’s superpowers, it’s true, but he empowers everyone he encounters. He empowers them with knowledge and compassion. Without Mr. Clarke’s constant support and willingness to indulge their curiosity voyages, there’s absolutely no way these kids could save the world.

Have I mentioned I love this guy?

That’s it! We have reached the end of our look at the scientists of Stranger Things. No need for the discussion to end, though – I’d love to hear your thoughts!

*award-winning PhD, thank you very much!

November 12, 2019

Teach Write: An Introduction to Purpose

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

As part of our preparation for writing a new piece, we need to think about audience – who we are writing for and how the knowledge and needs of that audience affect the way we approach our work. Figuring that out before we start saves us a huge amount of time in the downstream phases, like drafting and revising our work.

Equally important, in terms of maximizing our focus, clarity, and efficiency, is understanding our purpose: identifying the intention or end goal of our work.

The purpose of the piece is so important that particular formats, styles, and conventions have been developed to make the intention of the writing more apparent to the reader. Don’t believe me? Compare the IMRAD format of a lab report or scientific paper – documents designed to present the results of an experiment to fellow scientists – with the format of a picture book. And consider how the format and style of a picture book varies depending on whether its purpose is to educate, entertain, involve, or help a small child drift off to sleep on a blanket of security and love.

So, as writers, one of the first things we need to establish is WHY we are writing a particular piece. Is our goal to:

explain, educate, or illuminate?

outline a process or provide concrete advice?

entertain?

inspire and uplift?

connect with others through presentation of shared experiences?

persuade or present an argument for a particular point of view?

motivate action?

demonstrate our understanding of how much we’ve learned in class?

That last one, obviously, is pretty specific to students. But notice how the others could apply to creative writing just as easily as to different styles of academic writing.

We’re going to be taking a deeper look at each purpose over the next few months, as we explore different formats and genres of writing, both academic and creative. In the meantime, here’s an exercise to help you start thinking about purpose:

Brainstorm one academic and one creative genre of writing that matches each purpose listed above.

Consider how, as a writer, you’d need to approach each of those genres differently, in order to achieve the intended effect.

Hey, did you know I teach writing workshops? It’s true – I work with adult writers, teachers, and students of all ages. Contact me to learn more.

November 4, 2019

STEMinism Sunday: Women in Space

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to get to know some of these intellectual badasses.

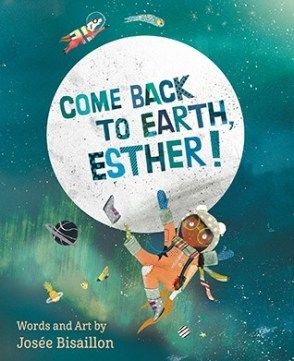

In honour of the recent, first-ever, all-female spacewalk, I thought I’d share three recent, amazing Canadian kids’ books united by the theme of women in space.

The first book authored by award-winning illustrator, Josée Bisaillon, Come Back to Earth, Esther! celebrates a child’s limitless imagination… and shows how much kids can accomplish when their imaginations are combined with determination. Bisaillon’s illustrations are lush and exuberant and full of details that kids will enjoy hunting through, discovering new things each time – much like Esther!

This book also gave me an intense Calvin and Hobbes vibe, which was an added bonus. Available in both English and French editions.

Next, we have Small World, by Ishta Mercurio. Small World was illustrated by Jen Corace, in a very different, but equally compelling style. I loved the way the texture and patterns in the pictures added depth and resonance to Mercurio’s spare, lyrical text. This is a book about that’s about comfort and home as much as exploration and limitless horizons. Kids will fall in love with it when young, and return to it over and over again as they grow. It’s also a perfect graduation gift for those who just can’t stand one more book by Dr. Seuss.

Next, we have Small World, by Ishta Mercurio. Small World was illustrated by Jen Corace, in a very different, but equally compelling style. I loved the way the texture and patterns in the pictures added depth and resonance to Mercurio’s spare, lyrical text. This is a book about that’s about comfort and home as much as exploration and limitless horizons. Kids will fall in love with it when young, and return to it over and over again as they grow. It’s also a perfect graduation gift for those who just can’t stand one more book by Dr. Seuss.

You can read the guest post Mercurio wrote for this blog, here.

And last but not least, Counting on Katherine: How Katherine Johnson Saved Apollo 13, by Helaine Becker, illustrated by Dow Phumiruk. This picture book biography has won…. well, pretty much ALL of the awards it’s eligible for. It’s really that good, and will satisfy kids who want their stories to be true, as well as inspiring. Becker did extensive interviews with Johnson and her family while researching this book, which is both accurate and uplifting and will make you want to yell “GIRL POWER!” at the stars. Johnson is brilliant and fierce and, with this book, even the youngest readers can appreciate her pivotal role in the space race.

And last but not least, Counting on Katherine: How Katherine Johnson Saved Apollo 13, by Helaine Becker, illustrated by Dow Phumiruk. This picture book biography has won…. well, pretty much ALL of the awards it’s eligible for. It’s really that good, and will satisfy kids who want their stories to be true, as well as inspiring. Becker did extensive interviews with Johnson and her family while researching this book, which is both accurate and uplifting and will make you want to yell “GIRL POWER!” at the stars. Johnson is brilliant and fierce and, with this book, even the youngest readers can appreciate her pivotal role in the space race.

Bonus: all three of these books feature protagonists who are girls of colour. Because girls of all backgrounds can be STEMinists!

October 28, 2019

Cantastic Authorpalooza: Jean Mills

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest: Jean Mills . Take it away, Jean!

How the setting sparked the story: Larkin on the Shore

Warning, readers: I’m not a science writer. But like any scientist, I do incorporate research findings (of a sort) into my stories. Here’s one example that’s especially true of my most recent YA novel, Larkin on the Shore.

When stories come to me, they usually start with scenes, like in a movie. The scenes start to evolve, characters spring up and talk and interact, and the story arc forms.

Did you notice that I didn’t mention “setting” in that process?

It’s true. Of all the elements needed to create a story, setting is usually the one that creeps up on me last.

All that changed when I wrote Larkin on the Shore because Larkin’s story started with the setting: more specifically, with the shore.

My shore is found on the Northumberland Strait near Pugwash, Nova Scotia. Once it was a farm in my husband’s family, but now he and his cousins all have sections of the original land for homes that we use in the summer and more recently for me, during other parts of the year as well. It’s my other home, and it’s magic.

Into the setting, this scene, comes Larkin. Some bad things have happened to her and she’s reeling and needs help. Her “shore” is sometimes internal – she’s on the edge of something that could drown her and she’s also on the edge of making choices that will keep her afloat. But it’s a real shore, too. She finds it, sometimes unfamiliar and scary, and sometimes soothing, here at her grandmother’s house in the little Nova Scotia community of Tuttle Harbour (aka Pugwash).

Writing this novel became a personal exercise in lifting real places that I know well and weaving them as important features into the fabric of the story. So here we go, my “research”: a tour of the real-life setting in Larkin on the Shore. (And I’ll try not to give too much away as I guide you through.)

The shore

I need to capture this moment, store it somewhere so that I can pull it out when I need it – the water and sky, the muted far-off evening sounds and the silence right here around me…

The shore for me is a thinking place, and it becomes a thinking place for Larkin too, the bad thoughts and the good ones. Being out on our little stretch of the Northumberland Strait at sunset, at low tide, when the wind drops – what is it about water that makes us think deep thoughts?

The Tuttle Harbour Café and Reading Room

A café. A small-town Starbucks wannabe. Granne’s big retirement project.

Around the walls, shelves for books. Used books. And a corner that can be turned into a performance nook for cool singer-songwriters or fiddlers or aspiring poets and writers to read on special literary open mic evenings. An arts hub, Granne calls it.

There is a café in Pugwash – The Chestnut Café (seen here). Pleasant and efficient. But before this, it had different owners and a different feel. This earlier café, called The Chatterbox, was the model for Granne’s big retirement project. It was a café where you could sit and read or work, with used books on the shelves for borrowing, an arts hub for occasional Friday-night concerts. (The Chatterbox was also the place we went to get Wi-fi, but I didn’t include that part…!)

The library

They talk about books and Granne asks me what I’m reading (some mystery series that everyone at school is into) and she takes me to the library in the village, housed in the old train station.

The Pugwash Library is indeed housed in the old train station. It’s a tiny little place with the most welcoming librarians (I see you, Mary!) and it’s a regular stop during my stay in town every year.

Becca’s house

“Great,” she says and swings up the lane towards her house, a classic white farmhouse with gables in the black roof, a wide verandah overlooking the front field, over the road to another field, and the channel beyond. A bright red front door.

The description of the house is mostly made up by me, but there actually is a gorgeous old farmhouse up on a hill at the end of a long lane on our road. When we have campfires at our cousins’ farmhouse (a pasture lies between the houses), we can watch the moon rise right over the house. It’s classic, and I wanted Becca to live there because a local writer friend of mine actually did live there, with her aging parents, for a time. A bit of real life incorporated into the story (and this photo, taken in the spring, includes a herd of hungry deer, too. Bonus!)

Rug hooking

Colours everywhere. On the stretched burlap canvas. All around me on the walls as I look around slowly. Hangings of all sizes, some actual images of people or trees or buildings and some just a textured mash-up of water colours, or sky, or flowers. People dancing, an owl staring out, a horse and wagon, a giant sunflower.

“This is where I work,” Becca says. “What do you think?”

I’ve been a knitter for a long time, but I only took up rug hooking a few years ago after discovering a beautiful rug on display in Thinker’s Lodge, the Pugwash museum in the former home of industrialist and activist Cyrus Eaton. The rug was by local artist Deanne Fitzpatrick and I soon after visited her studio in Amherst, Nova Scotia.

I was –yes, sorry – hooked.

Whether knitting, crocheting or hooking, when I work with wool, yarn, hook or needles, I find not only a creative outlet, but also a soothing place of escape. Larkin needs that, something Becca recognizes, and so I used Deanne and her wonderful studio as a starting place for Becca and her art.

Brenda’s Bakery with its “magic” cookies

So I shrug, say, “Let’s get the stuff,” and wave the twenty in the air. “Maybe a coffee and a giant ginger-molasses cookie will fix everything.”

He actually laughs at that. “Yeah, Brenda’s cookies are like magic.”

It’s actually Sheryl’s Bakery. And yes, the cookies (and, I hasten to add, the cinnamon rolls) are magic.

Back to the shore, where it started and where it ends

The tide has just turned and the first sandbars are emerging as I walk down the beach towards the point. The waves sound different as they leave the bars, hiss a little. It’s a night sound, a sound I’ve come to recognize now after a month here on the shore.

The setting was such a crucial part of Larkin’s story – hey, it’s a big part of my life too.

Jean Mills is a professional writer, editor and YA author living in Guelph, Ontario. Her novel Skating Over Thin Ice (Red Deer Press, 2018) was nominated for the 2019 Red Maple Fiction Award and named to the USBBY 2019 Outstanding International Books List. Her latest YA novel is Larkin on the Shore, published this month by Red Deer Press.

October 21, 2019

Mad Scientists of Stranger Things: Part III – Alexei

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

This is Part III in my series on the scientists of Stranger Things. Check the blog archive for thoughts on Martin Brenner and Sam Owens. Today, we take a look at everyone’s favourite Russian scientist, Alexei!

Here’s the thing about Alexei. Unlike his predecessors, he is without illusion. Opening the gate to the Upside Down was not his idea, and he is fully aware of the fact that doing so is a STUPID idea. He knows that if he does it, he might die, but he also knows that if he doesn’t do it, he will definitely die. Evil Russian movie generals, after all, are terribly unreasonable when it comes to employees who defy orders. Evil Russian movie generals are also bad at picking up cues like the sweat beading all over the foreheads of their scientists, especially if those cues suggest that their evil plans might not be the best plans.

Evil Russian movie generals are a lot like Martin Brenner that way.

Related: Is it weird that this entire season made me want to go “Oh, those Russians!” in my very best Boney M. voice?

Is it also weird that the secret Russian lair appears to be far more scientifically-advanced than the original Hawkins lab, but the Russian biohazard suits look like they are surplus from World War I?

But back to Alexei.