L.E. Carmichael's Blog, page 24

October 15, 2019

Teach Write: Age Groups and Audience in Children’s Literature

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

This will be our final column on audience (at least for now). So buckle up for a crash course on age levels in children’s literature!

First, a caveat: the categories I’m presenting here are not absolute. Different people use different words to describe them, and set the cutoffs in slightly different places. As children’s writers, we must also be aware that every kid learns to read at his or her own pace, so there’s going to be a lot of variation in text complexity within categories, too. Publishers and parents are always looking to strike a balance between a child’s reading comprehension, and the ideas or themes they are emotionally ready for (see my previous Teach Write post about dual audiences in kid lit).

End of PSA, let’s dig in!

Pre-Readers – Ages 0-6ish

This category (obviously) is designed for kids who aren’t yet reading on their own. We’re talking board books and picture books, and magazines like Babybug. The word count is typically very short, but the vocabulary can be relatively high, because at this age, adults are reading to kids.

Early Readers – Ages 6-9

Now we are talking about kids that are learning to read independently. Kids in this age group have a wide range of confidence levels, so may be reaching for anything from a picture book, to a levelled reader, to an early chapter book.* At the chapter book phase, the text is obviously longer than for picture books. However, sentences tend to be shorter and simpler in structure, and vocabulary is typically lower than for books targeting pre-readers. That’s because beginning readers are still building their visual word-recognition skills, and they can become intimidated if the text looks too hard.

Middle Grade – Ages 8-12

Kids in this age group have developed more confidence as readers, so they can handle more complex texts. That will involve higher vocabulary and greater complexity in syntax (hello, compound sentences!). It could also involve novels that have subplots in addition to the main plot, or a larger cast of characters. Themes (in both fiction and non-fiction) are also “older” at this level, reflecting the audience’s greater emotional maturity and curiosity about the wider world.

Teen or Young Adult (YA) – Ages 12+

Most bookstores have a single section for YA, but most publishers (and booksellers) will tell you that there are actually two categories here: tween, which is typically 10-14, and “upper YA”, which is typically 15+. Teens in both groups are proficient readers, so this split is all about content. How much do your characters swear and how physical are their romantic relationships? If there’s a lot of realistic violence (as opposed to the kind typical of fantasy novels), or drugs/alcohol, you’re probably writing for older teens.

Teen Hi-Lo, or Reluctant Readers

This is a special category, for teens** who are emotionally ready for mature themes, but are not yet proficient readers. These books have high-concept, engaging plot lines, with a snappy pace and lower text complexity. They give teens stories that are interesting and relevant to their lives, while being quick reads for those who are still building their reading skills.

Bonus Writing Exercise: How to write about practically anything for practically any audience.***

Your challenge (should you choose to accept it) is to brainstorm ways to adapt a single topic for every type of audience listed here. A topic to get you started: the perennial favourite, DINOSAURS! And feel free to share your results in the comments, for those of us who learn by example!

Hey, did you know I teach writing workshops? It’s true – I work with adult writers, teachers, and students of all ages. Contact me to learn more.

*Kids that have reached the “chapter book” stage are (justifiably!) VERY proud of themselves!

**When I worked at Chapters, we also had adult literacy organizations looking for books like these. Ask for them if you’re working with adult or second-language learners.

***Yes, of course there are exceptions. That’s why I said “practically.”

October 6, 2019

STEMinism Sunday: Tahrana Lovlin, Snow Specialist

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to get to know some of these intellectual badasses.

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to get to know some of these intellectual badasses.

Today, my guest is Tahrana Lovlin, brilliant woman and accomplished engineer… with an unusual specialty. Take it away, Tahrana!

So I’m writing this because Lindsey asked me to and I’ve known her for almost 30 years (wow, crazy). And I’m an engineer. Not your stereotypical engineer, the ones you see in the movies that work for NASA and wear ties and carry pocket protectors. Those engineers don’t exist – well, not anymore. Or if they do, they are a small portion of the overall world of engineering. As an engineer, I problem solve with a team that requires daily communication and coordinating, I write A LOT of reports, and occasionally I get to go to cold places for work. I’ve helped on projects in Alaska, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, northern Labrador, and Antarctica.

So I’m writing this because Lindsey asked me to and I’ve known her for almost 30 years (wow, crazy). And I’m an engineer. Not your stereotypical engineer, the ones you see in the movies that work for NASA and wear ties and carry pocket protectors. Those engineers don’t exist – well, not anymore. Or if they do, they are a small portion of the overall world of engineering. As an engineer, I problem solve with a team that requires daily communication and coordinating, I write A LOT of reports, and occasionally I get to go to cold places for work. I’ve helped on projects in Alaska, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, northern Labrador, and Antarctica.

I got a bachelor degree in Civil Engineering at the University of Waterloo in 2000. I did a year of structural design in Yellowknife, and then returned to southern Ontario to get married. I applied to a few design firms, but ended up at RWDI, a niche engineering consulting firm that did some pretty cool stuff according to the Discovery Channel.* I got a job there pretty much based on the fact I had “experience” with snow, meaning I had lived in the Northwest Territories for more than a decade. And since then, I have spent my career figuring out how wind and snow interact with buildings, and how this interaction affects pedestrians and users of the building. I now work for SLR Consulting in Guelph, Ontario.

So let’s talk snow, which is one of my favourite subjects. I like the way snow sounds, especially at -40C. I love the way it drifts into these perfect aerodynamic shapes that seem to defy gravity. It amazes me how much can accumulate in front of my garage after a good storm!

So let’s talk snow, which is one of my favourite subjects. I like the way snow sounds, especially at -40C. I love the way it drifts into these perfect aerodynamic shapes that seem to defy gravity. It amazes me how much can accumulate in front of my garage after a good storm!

There are two facts about snow that are essential in my job. One fact is that snow only moves or “drifts” once the wind speed reaches about 20 km/h. Which means, if you consider the average winter wind speed, there is less chance of drifting snow in Inuvik (~ 8km/h) than in St John’s (~ 25 km/h). The second fact is that snow can only drift for about 3 km and then it rubs itself out; this is probably a good thing or there would be way more snow in Winnipeg than I would care to consider.

Now, if you put a building in the way of this wind and snow, the snow will only accumulate in sheltered areas where the winds speeds are calm, and would be scoured from areas with strong winds. If the building is square and on the ground, and the wind hit it perfectly perpendicular to the upwind side, the snow would form a horseshoe-shaped drift around three sides. Right against the building the ground would be scoured by the wind, but a few metres away from the building a 1 to 3 m tall drift would form. On the downwind side, the drift would form right against the building facade, and if there were enough snow, the downwind drift could be as tall as the building!

Now, if you put a building in the way of this wind and snow, the snow will only accumulate in sheltered areas where the winds speeds are calm, and would be scoured from areas with strong winds. If the building is square and on the ground, and the wind hit it perfectly perpendicular to the upwind side, the snow would form a horseshoe-shaped drift around three sides. Right against the building the ground would be scoured by the wind, but a few metres away from the building a 1 to 3 m tall drift would form. On the downwind side, the drift would form right against the building facade, and if there were enough snow, the downwind drift could be as tall as the building!

However, if you were to raise the building above the ground, as they do in the Canadian Arctic, the downwind drift would form away from the building. Where the drifts form can significantly impact the accessibility of the building in winter, and the effort required for snow removal, which affects the day to day life of people that use the building. Think of it, do you want to shovel out your front entrance every day or would you rather use the sustainable approach of having Mother Nature clear it for you? As a snow engineer, it’s my job to think of that stuff for you.

*I can vouch for that – some of RWDI’s work on the world’s tallest building appears in my teen book, Amazing Feats of Civil Engineering.

September 30, 2019

Cantastic Authorpalooza: Frieda Wishinsky

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest: Frieda Wishinsky

. Take it away, Frieda!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest: Frieda Wishinsky

. Take it away, Frieda!

My Writing Career and the Many Writing Roads I Travel….

A poet and illustrator once said to me, “Why don’t you stick to one kind of writing? You’re all over the place. You should write one kind of book and brand yourself.”

It’s true. I write in many genres— picture books, chapter books, series, novels, hi-lo and non-fiction. I’ve written book reviews and articles for adults. The only kids book genre I’ve never attempted (and probably never will) is young adult. I write “all over the place” while this accomplished poet sticks to one genre and one style of art. People immediately link her name with her humorous content and the distinctive look of her illustrations.

I don’t know if her approach is better or more successful but it isn’t for me.

I love variety. I love trying something new. I’m interested in a broad range of topics and themes.

I’ve always been fascinated by how historical events connect. (I have a BA in International Relations, Honours in History and a Master’s of Science in Special Education.) I read memoirs and biographies as a kid and I still do. When I was young I wanted to be a scientist and cure cancer—till I realized I didn’t like studying science or working in a lab. What I loved was reading about the lives of scientists. And now I write about them.

Even though I love writing in different genres, picture books are my favourite genre. I’ve written 13 of them. A few rhyme but most don’t. Some are for the very young like my latest, ALFIE, NO! and my first, OONGA BOONGA (both Scholastic Canada). Some are more sophisticated like THE MAN WHO MADE PARKS, The story of park builder Frederick Law Olmsted (Tundra). Many are laced with humour, even when they touch on a serious theme like bullying (YOU’RE MEAN LILY JEAN, Scholastic).

Picture books are also the most challenging genre. It’s hard to create a page-turner with vivid characters your readers care about, a fast-paced plot, and a meaningful theme in only about 500 words. You want kids and adults to want to read the book over and over. You want your book to be timeless and universal. You have to remember that someone else will be adding a huge dimension to your words through the art. You need to leave room for the art by not writing too much but just enough.

Picture books are also the most challenging genre. It’s hard to create a page-turner with vivid characters your readers care about, a fast-paced plot, and a meaningful theme in only about 500 words. You want kids and adults to want to read the book over and over. You want your book to be timeless and universal. You have to remember that someone else will be adding a huge dimension to your words through the art. You need to leave room for the art by not writing too much but just enough.

All of this goes into the delicate, demanding work of a picture book. Yet when it works, it’s so satisfying. It’s taken me years to get some picture books right. My first picture book, ONNGA BOONGA is still in print (and now it’s a board book too). That makes me happy. But, so does writing a recent non-fiction for middle grade readers (or older) called HOW TO BECOME AN ACCIDENTAL GENIUS (Orca). And just to add to the mix of variety, that book was my fourth with my wonderful writing partner, Elizabeth MacLeod.

Maybe what connects all my books is my style and my themes. I write clearly. Humour is important. My stories are fast-paced and I’m not a flowery writer. Some of my core themes are the power of friendship, how to deal with bullies, and the connections in history.

I never know what character, subject or idea will engage me next. Maybe a trip will spark a story or perhaps a walk across a bridge. When I walked across the Brooklyn Bridge, one of my favourite places in my hometown of New York City, I read a plaque about Emily Roebling and was intrigued. Soon after I looked her up. And as soon as I did, I knew I wanted to tell her story.

HOW EMILY SAVED THE BRIDGE (Groundwood) came out this year.

September 24, 2019

Mad Scientists of Stranger Things: Part II – Sam Owens

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

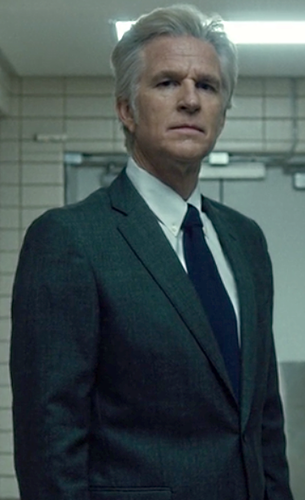

And we’re back for another look at the scientists of Stranger Things. Today, Dr. Sam Owens, successor of the horrible Martin Brenner, new head of Hawkins Lab.

Let’s just take a moment to reflect on the stroke of brilliance that was casting Paul Reiser in this part. I don’t know about you, but my first exposure to Paul Reiser was in the 1990s sitcom Mad About You, where his character is smart and funny and endearingly neurotic. My experience of that character infused my reactions to Sam Owens, whom I found immeasurably more appealing than Brenner.* Sam is also a paternal figure, but he’s paternal in the genial-country-doctor kind of way, the way that puts people at their ease and convinces them to trust him. It’s a very comforting form of paternalism.

However, that paternalism is based on a flaw that’s all too familiar – arrogance.

It’s not the same kind of arrogance as Brenner’s. Brenner’s arrogance is based in an unshakeable belief in his own power. Owen’s comes from a lack of imagination. He can’t imagine that people who aren’t scientists can understand the situation. And he can’t imagine a world where science might actually fail – a world where the unknown defies our attempts to define it, predict it, and ultimately put it in a safe little box where it can’t hurt us. Because of this lack of imagination, Owen’s apparent humility and willingness to admit he doesn’t know everything comes off as somehow false – particularly when we see the differences, early in the season, between the way he treats Joyce and Hopper (the public) and the way he treats his colleagues.

That being said, Owens differs from Brenner is one more way, a way that matters more than anything else: he’s redeemable. He genuinely cares about people other than himself, and particularly those more vulnerable than himself: his kindness towards Will and Eleven is real. Also unlike Brenner, Owens has the ability to learn from his mistakes. And once his eyes are opened, he adapts.

His willingness to recognize mistakes, and to recognize that sometimes, people are more important than discovery, is what makes me like him, despite his flaws.

Next time – Alexei!

How do you feel about Sam Owens? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

*But let’s be honest, if you DON’T like this guy more than Brenner, I don’t think we can still be friends.

September 17, 2019

Teach Write: The Dual Audiences of Children’s Literature

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Last time, we discussed the special, double audience that we have to consider when writing a class assignment for a teacher. Hopefully that advice will help all the students that have now gone back to school! The audience* for today’s column is totally different: children’s writers. We are going to talk about the dual audiences that we need to be aware of when writing children’s literature.

The first thing children’s writers need to recognize is that, much like students, we are ALWAYS writing for two audiences:

our young reader

the adult gatekeepers surrounding that young reader

If you’re a parent, you know all about adult gatekeepers, because you are one. So are teachers and librarians (and going back even earlier in the road to publication, editors and reviewers). The younger the child you’re writing for, the more say the adults in that child’s life will have over the material they are exposed to.

This creates an interesting tension between the scary, silly, gross, mature things kids like, and what adults think kids SHOULD like: a tension between what kids think is interesting and what adults think is appropriate.

One obvious example of this is language. The use of curse words is basically a no-no unless writing for teens, even though you’ve probably heard much younger kids using them in real life.** However, concern over language may also apply to official terminology for human anatomy – just ask Susan Patron about the uproar over her use of the word “scrotum” on the first page of The Higher Power of Lucky.***

Content and theme can also be tricky areas to negotiate in children’s literature. When I worked in the children’s section at Chapters, I was always astonished by adults that had no concerns about violence in kid lit, but drew a hard line at other forms of human contact.**** Serious or “heavy” themes also spark flurries of concern, as debate over whether YA has gotten “too dark” pops up online every six months or so.

In part, these concerns arise from a genuine desire to protect kids from the harsher realities of life. And I definitely understand that. But I also think that, when we become adults, we forget what being a kid was actually like. We forget the things that we, as kids, experienced and endured–or watched those we love experience and endure. To paraphrase Canadian author Alma Fullerton, kids experience things every day that adults won’t let them read about.

So how do we, as writers, proceed? First, we do our homework. Don’t worry, it’s the best kind of homework–reading! We have to read a ton of recently-published work for our intended audience to get a sense for where the boundaries lie. As a bonus, this helps us figure out how our overall book idea compares to what’s already out there.

Second, we trust. We trust our instincts and our memories of childhood. We trust the story we are trying to tell, and our ability to be honest and authentic in the telling. And we trust our editors to help us navigate the grey areas as they arise.

Next time, we’ll wrap up our discussion of audience in writing with a closer look at different age categories in kid lit, and how almost any idea can be written for any age. Stay tuned!

Hey, did you know I teach writing workshops? It’s true – I work with adult writers, teachers, and students of all ages. Contact me to learn more.

*See what I did there?

September 8, 2019

STEMinism Sunday: Dr. Linda Campbell

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to get to know some of these intellectual badasses.

Today, we’re talking to Dr. Linda Campbell of Saint Mary’s University. I worked with Campbell at SMU, and she’s passionate about both her science and science communication, so she’s a perfect fit for this blog!

Your work focuses on aquatic ecosystems – lakes, wetlands, and their associated life forms. What made you want to work in this field?

I have always enjoyed being outdoors being curious about what was around me since I was a little kid. That curiosity has led me in many interesting directions, and resulted in my decision to take Biology at university. I took many types of courses, and realized that I was most concerned about freshwater issues.

A lot of your research has focused on environmental contaminants, especially those from industry. What would you say is the most important discovery you’ve made?

Mercury is a very old contaminant used by humans for millennia around the world, but remains a modern legacy in freshwater ecosystems around the world.

What the heck is a Chinese mystery snail, and why should we be concerned about them?

Chinese mystery snails are large freshwater snails that are native to eastern Asia and Russia. Those are popular food species for humans and are also used as aquarium species to keep fish tanks clean. Chinese mystery snails were brought to western USA in the late 1800’s, and gradually were re-introduced to many ecosystems across North America. We are currently tracking presence and abundance of Chinese mystery snails in Nova Scotia where those species are under-studied and under reported. We are concerned that the new presence of Chinese mystery snails may have impact on freshwater food webs and water quality of our lakes.

You serve on the Board of Gallaudet University for Deaf and hard-of-hearing students and are involved in research and advocacy for Deaf academics and the Deaf community in general. How have your experiences as a Deaf scientist changed over the course of your education and career? Do you see more opportunities for Deaf students than were available to you?

You serve on the Board of Gallaudet University for Deaf and hard-of-hearing students and are involved in research and advocacy for Deaf academics and the Deaf community in general. How have your experiences as a Deaf scientist changed over the course of your education and career? Do you see more opportunities for Deaf students than were available to you?

Being a Deaf scientist in a hearing world can often mean more work and more responsibility for me as I must constantly educate my colleagues and students, and people often look to me for answers regarding diversity and inclusion. It also means more opportunities as I meet a very wide range of people beyond the usual pool of scientists and university colleagues. As a result, I get opportunities to solve problems via lateral thinking or even via “orthogonal thinking”, e.g. thinking perpendicular to issues and finding solutions beyond the usual patterns.

Deaf scientists are rare due to implicit biases, communication barriers and scarcity of role models in scientific fields. In my field, there are only 2 aquatic environmental researchers who are Deaf in the world, with my colleague Dr. Caroline Solomon being at Gallaudet University in Washington DC. There are several graduate students in this field who are Deaf, so we are hoping it won’t be long before our numbers grow!

Capitalizing the word “Deaf” indicates that we are members of a culture and linguistic community who use sign languages and visual communication strategies, and the Deaf community is global in nature with strong networks, shared love of multiple sign languages and cultural practices. Being a member of this community is wonderful, and being able to share and talk science with another Deaf scientist in one of our sign languages is a fantastic opportunity.

What advice would you give to girls (and any other kids!) who are interested in working in STEM?

Be curious about the world around you, read and think as much as you can, find people of all ages who share your curiosity and passion for discussing science. Mentorship is important, not only for you, but also you becoming a mentor to others, so seek opportunities to learn from others and to teach others.

September 2, 2019

Cantastic Authorpalooza: Robin Stevenson

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest: Robin Stevenson . Take it away, Robin!

Ghost’s Journey: A Refugee Story

Ghost’s Journey: A Refugee StoryBack in 2015, I became involved in refugee sponsorship when I joined a group sponsoring a Syrian family with four small kids. It was a great experience. In fact, this first sponsorship led me to start three more sponsorship groups to help other refugees come to Canada and resettle in my community. I was learning a lot about refugee issues– so when I started working on the second edition of my book Pride (Pride: The Celebration and the Struggle, coming out with Orca Books in March 2020), I knew I had to include a section about the particular challenges faced by LGBTQ+ refugees. Around the world, more than 70 countries still criminalize same-sex relationships—and in many of these countries violence against LGBTQ+ people is common and widespread. As part of my research, I spoke with two gay men—Rainer and Eka– who fled persecution in Indonesia and resettled in Vancouver.

And this led to a whole new book- my first picture book! When Rainer and Eka travelled to Canada, there was one thing they couldn’t bear to leave behind: their cat, Ghost. In September, Rebel Mountain Press— a BC publisher who shares my interest in LGBTQ+ rights and in supporting refugees— will publish Ghost’s Journey: A Refugee Story. It is inspired by Rainer and Eka’s story, and the illustrations are created from Rainer’s photos of the real Ghost.

Here’s an early review from Kirkus. They write, “Stevenson tells the real-life story of Eka Nasution and Rainer Oktovianus with simplicity and clarity for younger audiences…This introduction to LGBTQ human rights for young children is a gentle and effective one.”

Here’s an early review from Kirkus. They write, “Stevenson tells the real-life story of Eka Nasution and Rainer Oktovianus with simplicity and clarity for younger audiences…This introduction to LGBTQ human rights for young children is a gentle and effective one.”

There are a couple of organizations doing important work to help LGBTQ+ refugees. Rainbow Railroad is one of them. They help LGBTQ+ people who are facing state-sponsored persecution and whose lives are in danger. Here is a very powerful video about the life-saving work they do. Another is Rainbow Refugee, a Vancouver-based organization that helps LGBTQ+ refugees come to Canada, and supports LGBTQ+ asylum seekers who are already here. You can watch a video about their work here.

All my author royalties and partial publisher proceeds from sales of Ghost’s Journey will go support LGBTQ+ refugees, through Rainbow Refugee and Rainbow Railroad, and through Canada’s Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program and BVOR Program. Ghost’s Journey will be available in stores in September, and you can also order directly from the publisher. I am hoping this book will help raise both funds and awareness, and I am very grateful for any help spreading the word!

Robin Stevenson is the author of 25 books for children and teens. She is a Silver Birch winner, Stonewall honour recipient, and Governor General’s Award finalist. This fall, she is also launching KID ACTIVISTS (Quirk Books). Robin’s books have been translated into a number of languages and published in more than a dozen countries. She lives on Vancouver Island with her family.

Find her online at www.robinstevenson.com

August 26, 2019

Mad Scientists of Stranger Things: Part I – Martin Brenner

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

Time to get a little… strange… over here, with a series of posts about the scientists* of Stranger Things. We’re going to start with Martin Brenner, the true Big Bad of Season One, and a textbook example of one of Hollywood’s favourite scientist tropes: the Machiavellian scientist who believes that knowledge matters more than decency, ethics, or human rights… the one who will do anything to get his answer.

But first, I give you the notes I scribbled while rewatching Season One in prep for this post:

When dudes in lab coats are fleeing in panic, we all need to be worried….

When did Matthew Modine get so creepy?

Uh oh, biohazard suits. Never a good sign. Neither are scorched and brain-splattered walls.

Or barefooted girls in hospital gowns.

Or anytime people have tattooed numbers instead of names.

And that was just episode 1!

In case there was any doubt that these scientists are up to NO GOOD, let’s take a moment to appreciate the aesthetic of their leader, Martin Brenner:

Pale, thin, stretched, well dressed. This guy is clearly a vampire, sucking the life out of small children for fun and profit (or knowledge and power). And his arrogance, his conviction that what he’s doing is justified, and that he can control the things he unleashes, is practically oozing out of his eyes.

We can all agree that tearing a hole in reality is bad enough, but for me, the thing about Brenner that’s truly unforgivable is the fact that he cultivates a paternal relationship with Eleven, combining evil scientist and abusive father* in a truly unsettling synergy. The first real sign of affection he shows El is in Episode 3, when she has just murdered in self-defence, and the affection isn’t even for her – he touches her head, the seat of her power, telling us that (much like Mother Gothel in Disney’s Tangled), he only really cares about what she can do.

And then there’s the cat.

It’s a well known truth among writers of all stripes that your character can do a lot of awful things, but as long as they commit one good act, like saving a cat from a burning building, they are empathetic and redeemable. (See the infamous screenwriting bible, Save the Cat.)

Brenner, however, not only kills the cat, he forces a child who calls him Papa to kill the cat. There’s no way back from that.

What are your thoughts on Martin Brenner, or Stranger Things in general? Next time, Dr. Owens!

*Not the science. This time, I’m more interested in the people doing the science.

**Both of which are deplorable.

August 20, 2019

Teach Write: When Your Teacher is Your Audience

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Listen up, students, because this edition of Teach Write is all for you: today, we continue our exploration of audience with a critical one: teachers.

When teachers give us writing assignments, they are trying to measure two things:

whether or not we understand the material we are writing about*

whether or not we’ve mastered the form and format we’re writing in.

The first point is about having our facts straight – it’s our chance to prove that we’ve understood what the teacher was talking about all those weeks in class, or perhaps the material that we dug up during our research. Needless to say, if you’re not sure you understand your subject matter, you’re going to want to sort that out BEFORE you start writing!**

The second part is about demonstrating that we understand what a research paper, argumentative essay, lab report, or general interest piece is supposed to look like, and that we are able to work within the conventions of that form. It’s also about recognizing that, in addition to our teachers, every writing assignments has a second, hidden audience that we have to take into account.

True story:

In my fourth year of university, one of my professors told us to write a magazine article that explained a genetic disease to a general audience. Sounds simple enough, except for the fact that I hadn’t read a magazine since my childhood subscription to Highlights for Children had expired. I had NO idea what the form, style, and tone of a magazine article was like, and it didn’t actually occur to me to go read some magazines before starting to write.

Needless to say, I did not do so well on that assignment.

The face that my teacher must have made when reading my assignment!

So, before you start your assignment, make sure that you know your material, but also that you know what the end product is supposed to look like and who it’s supposed to be written for. If you can’t tell from the instructions, make sure to ASK.***

Bonus tip for teachers: Give students samples of the format you’re looking for. Some of us work best from examples (on unrelated topics, natch!).

Comments? Questions? I welcome discussion from both teachers AND students!

*assuming that our assignment is not poetry or some other type of writing that’s purely creative, in which case, it’s all about the form

**ASK someone, preferably your teacher or librarian (or TA in the case of college or university). Never hesitate to seek help when you’re confused, because we are ALL confused at some point.

***Seriously.

Hey, did you know I teach writing workshops? It’s true – I work with adult writers, teachers, and students of all ages. Contact me to learn more.

August 11, 2019

STEMinism Sunday: Stigmatization of “Women’s Work” in Netflix’s Point Blank

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to get to know some of these intellectual badasses.

Today we’re branching out – rather than talking about a specific woman in science, we’re going to talk about the perception of women – and men – in medicine. Specifically, the perception of nurses.

It all started when Tech Support and I sat down to watch Netflix’s Point Blank. Less than five minutes into the movie, Paul, an emergency room nurse, comes home to his pregnant wife Taryn:

Taryn: Yes, Doctor.

Paul: (speaking to baby bump) That’s a very mature response for you . But… I’m not a doctor.

Taryn: YET.

At which point, Tech Support turned to me and said, “Because, remember, it’s only OK for men to be nurses if they’re actually trying to become doctors.” *

Where to begin, where to begin…

How about with a very firm statement that the profession of nurse is in no way inferior to the profession of doctor. And that people do not choose to become nurses because they couldn’t get into medical school. And that, while doctors have specialized training that nurses don’t have, nurses have specialized training that doctors don’t have.

Nursing is not a stepping stone into something “better” or “more prestigious.” It’s a difficult and demanding career practiced by talented people dedicated to helping other people. People like my mom, and Tech Support’s mom, and Tech Support’s sister. People without whom our modern medical system would cease to function.

And yet, nursing is stigmatized, because it’s considered “women’s work.” And “women’s work” is stigmatized because, well, it’s full of women.

The fact that a majority of nurses are women doesn’t mean that the work is in some way lesser.** And because the work has value, men who choose to pursue it shouldn’t be stigmatized, any more than women who chose to pursue it should be.

STEMinism isn’t just about promoting the work of women in traditionally male-dominated fields, just like feminism isn’t only about elevating the rights of women. STEMinism is about supporting the rights of all people – women, men, non-binary, and everyone else – to use their talent and hard work in the pursuit of any career, calling, or lifestyle they choose.

End of rant.

Have you seen Point Blank? What are your thoughts on this issue, or on the movie in general? I love hearing from you!

* The fact that Tech Support gets why this is so enraging is one of the reasons we are married.

** Actually, what it means is that, for a long, long, time, women have been actively excluded from pursuing so many other “unsuitable” careers.