L.E. Carmichael's Blog, page 22

March 2, 2020

Teach Write: The Purpose of Lit Reviews, Critical Analyses, and Other Forms of Academic Writing

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Last time, I talked about the purpose of the most popular form of academic writing – the argumentative essay. You can also read about the distinct (but closely related) purposes of lab reports and scientific papers here. If you’re a student, however, you’ll probably be assigned several other types of documents, and today we’re going to take a quick peak at the goals of those.

Critical Analysis

The goal of a critical analysis is to break down a published paper, identifying its strengths and weaknesses. Key point: both strengths and weaknesses. The most common error I’ve seen in these types of papers is focusing entirely on weakness and overlooking strengths. It’s very important to keep in mind the purpose of the type of document you’re analyzing – if you know what an argumentative essay is supposed to do, you’ll have more luck figuring out whether the one you’re writing about is actually successful.

Science students often ask me what to do if the results of the experiment they are analyzing turn out to be wrong. True story: that happened to me when I was an undergraduate! I found a second experiment that directly contradicted the paper I was writing about. With a little further research, I figured out that my focal paper was incorrect, but also why the experiment had given a false result. And let me tell you, if you can do the same, your instructor will be seriously impressed.

Hot tip: when choosing your focal paper for a critical analysis, read newer papers that cite your paper – you’re allowed to reference other people’s opinions in your own analysis.

Literature Reviews

A lit review is a research paper that provides a summary of existing scholarship on a topic. The goal is to provide an up-to-date overview of what we already know, and what questions still remain to be answered. The audience (remember when we talked about audience?) is people who are familiar with the field (for example, microbiology), but might not know much about this particular subtopic (for example, designer bacteria for cleaning up oil spills).

Because lit reviews typically follow a chronological structure, one of the biggest mistakes people make when writing them is to fall into a “This happened, and then this happened, and then this happened” pattern. Remember that part of the goal is always to show your instructor that you understand your research: context, synthesis, and a point of view matter just as much as summary.

Annotated Bibliography

This is basically “lit review light” and might actually be assigned as an early stage of your total assignment. In addition to providing citation information for your sources, you will give a short summary of the main points of each source. Short is the operative word – focus on major ideas that relate to your overall assignment. As always, there are two goals: a) to direct researchers in your field to useful sources of information, and b) to prove to your instructor that you actually did the reading!

Case Study

These are more commonly assigned in business or medical degree programs, so I have less direct experience with them. Generally speaking, you’ll be given a scenario, asked to analyze it in the context of theory in your field, and required to provide recommendations for action. Case studies test your ability to relate theory to the real world, so your goal will be to demonstrate that you understand how principles are used in practice.

Final Thoughts…

After essays and lab reports, these are the most common assignment types I’ve encountered in my decades as an academic writer and writing instructor. We’ll be looking at personal statements and letters of intent in a later post, but let me know if there are other genres you’d like to see discussed in this column. Also bear in mind that your assignment may involve a new and exciting hybrid of any of these elements. If you’re ever in doubt about what you’re being asked to do, always check with your instructor before you start.

Happy writing!

Hey, did you know I teach writing workshops? It’s true – I work with adult writers, teachers, and students of all ages. Contact me to learn more.

February 23, 2020

STEMinism Sunday: What Not to Wear

The only picture of me wearing a lab coat in existence. Ironically, it’s not my lab coat. It’s not even my lab. This photo was taken specifically for my book Fuzzy Forensics, which was written several years AFTER I finished my PhD and left academia! Notice the sweater – it was cold in this lab, too.

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to learn more about these intellectual badasses.

So, you’re a woman in science. Good for you! Have you thought about what you’re going to wear?

Nope, I’m not talking about latex gloves, hip waders, or safety goggles, although you do look very cute in those. I’m talking about what’s under your lab coat – those outfits you’ll wear to work, or during class, or at a conference…. all places where, I’m sorry to say, you will be judged on the presentation of your femininity far more than the presentation of your results.

If you’ve been a woman in science for more than five minutes, you know this already. From this hahahsob piece of satire about planetary bodies bold enough to go #nomakeup to a professor friend’s recent quest to find a safety pin for raising the neckline of her dress, to the entirely serious online articles offering sartorial advice to the lady scientist, to the offhand comments of male students and colleagues, we all know that we’re going to be judged on the way we look.

And though we are disappointed, we are not surprised, because we’re women. Being judged for the way we look is a defining experience of femininity. And it’s exhausting in all contexts, but especially in contexts where women are outnumbered and therefore operating at a disadvantage.

Such as STEM (science, engineering, technology, and math) fields.

It wasn’t as bad for me as it was for some of my friends. Because genetics is a biological science, there tended to be more women around than there are in “hard” sciences that were and continue to be dominated by men. I spent most of my lab hours in jeans and t-shirts (or sweaters, because it was freezing in there). But when I needed to assert my authority – for example, as a TA instructing a room full of students – or my credibility – at conferences – I was (and still am) intensely aware of my clothing choices. I need to look professional, but approachable. Authoritative, but not intimidating. And, every woman’s favourite – “appropriate.” Heaven forbid my heels are slightly too high or my neckline an inch too low and suddenly become #distractinglysexy

Because of my own experiences and those of many of my friends, I was particularly fascinated by this article by Canadian scientist Eve Forster. Forgoing her usual bun and letting her literal hair down ONE DAY resulted in such an egregious example of mansplaining (by one of her students, no less), that she decided to run a short experiment – tweeting exactly as she normally would for a week, using a female avatar, then tweeting exactly as she normally would for a week while using a male avatar. The results are a female scientist’s working environment in miniature. It’s a longer article, but pretty eye-opening.

As a white woman, I can’t even imagine how much harder it us for women of colour, or indigenous women, or women with disabilities, or anyone in the LGBTQ+ community to be taken seriously. All I know is that I was interviewed for this article on gender equality in science back in 2006…. and we still have a long, long way to go.

Your turn. Have you been told what not to wear at work? In school? In public? How do you handle these kinds of issues in your own life? Share your storied in the comments.

February 19, 2020

Happy I Read Canadian Day!

It’s the first ever I Read Canadian Day! Take 15 minutes out of your day today to read a Canadian book. Any Canadian book! And if you are so inspired:

read out loud to your class, library, family, or pet

post about that book on your social media feeds

write a book review on Goodreads, Amazon, or Indigo

donate to the I Read Canadian Fund, which helps put Canadian books in the hands of Canadian kids.

Looking for Canadian kids books to read from? The Canadian Children’s Book Centre has great resources, and CANSCAIP is full of Canadian authors. You won’t be able to read from my new book, The Boreal Forest: A Year in the World’s Largest Land Biome, because it isn’t coming out until April. BUT, you can watch these two videos I made for I Read Canadian Day. In the first, you’ll get a sneak peak at the art and text. In the second, I talk a little bit about the inspiration for the book and how it came to be.

Enjoy!

February 17, 2020

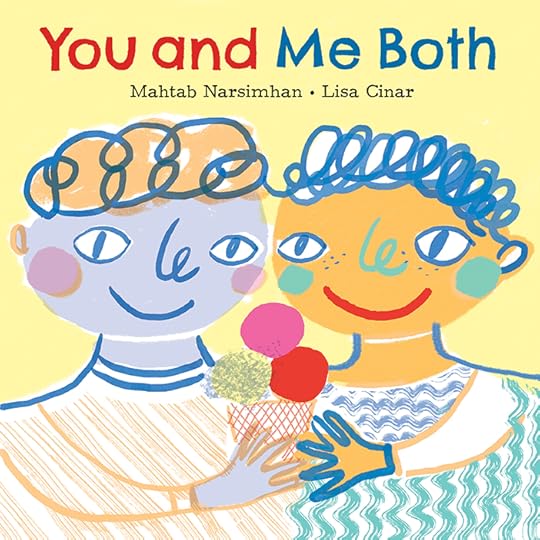

Cantastic Authorpalooza: Mahtab Narsimhan

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Mahtab Narsimhan

. Take it away, Mahtab!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Mahtab Narsimhan

. Take it away, Mahtab!

I dread reading the news these days. It’s important to stay up to date with current affairs but what do you do when almost everything you read ratchets up the stress, the tension?

I’ve figured it out.

You keep your eyes and ears, but especially your heart open for good news, for a story that makes you smile.

In 2017, I found that story in The Telegraph. It had gone viral and rightly so. It made me grin as I read it. A young Caucasian boy needed a haircut and asked his mother if he could get one exactly like his best friend so that their teacher wouldn’t be able to tell them apart. The picture accompanying the story was a slam dunk into my happy place. The Caucasian boy’s best friend was African. The only difference that this boy saw between them was their hairstyle.

It took a while for the picture book to come about but once I had it worked out in my head I wrote it in a single day. In the following months I tweaked and massaged it. The shorter a story is, the more difficult it is. Anyone who says otherwise has not attempted a picture book. At a hundred and forty words, this was the hardest thing I had ever written!

The more I read it, the more I loved it. If the kids in that story could see only hairstyles as the distinguishing aspect between them, at what stage in life would they start noticing other aspects? When would they begin to draw a line between them and us? Did it have to be this way?

I knew I had to write this story in a form that was accessible to the very young. If we could show kids that differences on the outside did not matter, that only shared interests and mutual love and respect mattered, we’d have a more tolerant future generation.

I knew I had to write this story in a form that was accessible to the very young. If we could show kids that differences on the outside did not matter, that only shared interests and mutual love and respect mattered, we’d have a more tolerant future generation.

I’m grateful to Editorial Director, Karen Li, and Publisher, Karen Boersma, at Owlkids Books who saw the potential in this story and agreed to publish it. With vibrant and colourful illustrations by Lisa Cinar, this story now has life. I hope You and Me Both reaches a wide audience and encourages meaningful discussions.

As a person of colour, I have faced a fair share of discrimination. I’ve lived in India, the Middle East and finally Canada. While most of my experiences have been positive, there have been times I wished I could be someone else. I don’t feel that way anymore. The zeitgeist encourages diversity, and openness. I am thrilled to be part of the conversation and am committed, through my writing, to champion diversity.

As a child I often read books that were windows. Though I glimpsed fascinating worlds I wasn’t familiar with, I always longed to see someone like me in those stories. Now I have the privilege and responsibility to provide a mirror.

You And Me Both is a step in the right direction and I sincerely hope we continue down this path towards an empathetic future.

February 10, 2020

Mad Science Monday: Coronavirus, Flu, and Wanderers

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

Last week, the news broke that Canadians who are being evacuated from China will be quarantined at Canadian Forces Base Trenton for two weeks, to ensure they’re not infected with the new coronavirus. This got my attention because CFB Trenton is about 10 minutes from my house.

I’m not actually that worried though, for several reasons:

passengers will be screened for illness before they’re even allowed on the plane

quarantine is designed to isolate infection until the danger of transmission has passed

I hardly ever leave my house anyway, so I’m pretty unlikely to come into contact with an infected person

I’m actually at greater risk of infection IN my house, due to the fact that Tech Support is a biomedical engineering technologist, and medical equipment is constantly moving in and out of this place.

If your exposure risk is higher than mine, all the things you’d normally do to avoid catching colds and flu apply:

wash your hands

wash stuff you touch

if you get sick, quarantine yourself at home

Also, if you’re going to wear a mask in public, get N95 (not a fabric mask) and make sure it’s fitted properly and pinched down around your nose. Don’t be this guy:

Attributed to @CarlZha/Twitter by iol.co.za

New illnesses are definitely scary (if you really want to lose some sleep, Chuck Wendig’s terrifying apocalypic novel Wanderers is brilliant and will keep you up nights), and as a result, a lot of misinformation circulates very quickly, on social media but also in the mainstream media. This is not surprising, because there’s a lot of misinformation out there about the flu, too, and we have flu outbreaks every year.

I was waiting around at the walk-in clinic this morning (no one was coughing or sneezing, fortunately), and overheard a very familiar conversation:

Patient: I’m here for a flu shot, but I hate them. I never get the flu, but every time I get the shot, I get sick. But my boss is making us get them.

Receptionist: Where do you work?

Patient: At a senior’s home.

I didn’t say anything at the time (I don’t like to be THAT person), but…

I have no idea whether this person’s immune system just gets extra excited about vaccines, or whether she’s been unlucky enough to catch a cold right around the same time, or if it’s just one of those years that scientists guess the wrong strain of flu when they start making the vaccine months in advance of flu season. But flu shots can’t give you the flu. They really, really can’t. And vulnerable people, like seniors and those of us with egg allergies who aren’t allowed to get flu shots,* rely on the protection that comes from you getting yours. It’s called herd immunity, and it helps keep everyone safer.

So please, get your flu shots, because, as scary as coronavirus sounds, the flu kills WAY more people.

End of PSA.

February 3, 2020

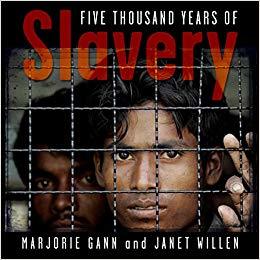

Black History Month: Slavery is Not History

It’s Black History Month, so today I have a special guest: Marjorie Gunn, Canadian author of two children’s books on the legacy and ongoing practice of slavery around the world.

When Francis Bok was seven years old, his mother sent him to the market near his village in southern Sudan to sell hard-boiled eggs and peanuts. This was the first time she’d entrusted him with this responsibility, and he felt very proud. But Francis’s pride was cruelly cut short when raiders on horseback galloped into the square and began shooting. He was one of many children captured, sold, and taken miles away.

At first Francis could not speak [his owner] Giemma’s language, but he listened carefully so that he could learn. One day he was able to ask Giemma a question: ‘Why does no one love me?’ Giemma did not answer. Francis tried again. ‘Why do you make me sleep with the animals?’ For two days Giemma said nothing, but then he replied, ‘Because you are an animal.’

This excerpt comes from the book Five Thousand Years of Slavery, which I co-authored with Janet Willen. Francis’s experience with contemporary slavery (he was captured in 1986) forms the framing story of our book. Although Five Thousand Years surveys the full scope of world slavery from antiquity to the present, the story of slavery in Africa occupies many pages and is worth retelling now, during Black History Month. Slavery is intrinsic to the story of Africa.

This excerpt comes from the book Five Thousand Years of Slavery, which I co-authored with Janet Willen. Francis’s experience with contemporary slavery (he was captured in 1986) forms the framing story of our book. Although Five Thousand Years surveys the full scope of world slavery from antiquity to the present, the story of slavery in Africa occupies many pages and is worth retelling now, during Black History Month. Slavery is intrinsic to the story of Africa.

The first chronicler of African life, quoted in Five Thousand Years, was a late-ninth century Arab geographer named Al-Yaqubi, who observed that “kings of the blacks sell their own people without justification or in consequence of war.” Centuries later, a Muslim traveller from the north coast of Africa wrote The Journey, which paints a vivid picture of the trans-Saharan slave trade: The traders, Ibn Battuta notes, “vie with one another in the number of slaves and servants they have.” Female slaves were a prized commodity: “From this country are brought beautiful slave women and eunuchs and heavy fabrics.” As they were to the later European and American slave traders, slaves were a commodity like any other. None of these traders showed any concern for the trauma their human cargo endured.

Struck by the plight of these human beings, Janet and I wanted our readers to hear the slaves’ voices. This was not difficult in the case of Caribbean and American slavery; robust abolition movements in Britain and North America prized (and often helped publish) the eyewitness accounts of escaped slaves like Frederick Douglass and Solomon Northup, whose narratives continue in print to this day.

But there were no African abolitionists, so the voices of enslaved Africans went largely unheard until missionaries arrived to engage with vulnerable communities. Five Thousand Years tells the story of Meli, captured in East/Central Africa (today’s Zambia) in the late nineteenth century when she was about five years old. Decades later, having been rescued and educated by English missionaries, she recounted her ordeal to her grandson, who recorded it:

She and other captives were forced to march for miles, carrying chickens, cooking pots, and other loot from their devastated village. If a mother collapsed, too exhausted to keep carrying the heavy loads and her baby, the marauders tied the baby up into a bundle and hung the child from a tree to starve. To them, chickens and cooking pots were worth more than children.

Meli’s first owner was a man who put her to work drying harvested grain by the fire. Chilled by the damp cold, she threw extra wood on the fire. A spark set the hut ablaze.

“I shouted, ‘Help! The hut is on fire!’

“The man and his wife were furious and they scolded me very strongly. The husband, mad with rage, seized me and almost threw me into the fire. But, thank God, the woman objected strongly, saying, ‘Do not bring evil upon us. Don’t you know that this person belongs to a chief’s family?’

“The man said, ‘You have been saved! But from now on you will eat only wild things you find yourself.’”

And what about Francis? How do we know his story? In the end, his deep religious faith (he was a Sudanese Christian) and his memories of his parents’ faith in him gave him the courage to flee. He made his way to a United Nations refugee camp in Cairo, where he was granted asylum in the U.S. He now lives in Massachusetts and speaks on behalf of the American Antislavery Group about slavery in Africa today

As Francis’s story shows, slavery is not history. We close Five Thousand Years with a survey of modern slavery, not just in Africa, but in prison camps in China, Cuba, and North Korea, on vegetable farms in the United States, in carpet factories in Pakistan, and among trafficked women. Black History Month can be a springboard for learning about the much broader story of human slavery, in the past and in the present.

As Francis’s story shows, slavery is not history. We close Five Thousand Years with a survey of modern slavery, not just in Africa, but in prison camps in China, Cuba, and North Korea, on vegetable farms in the United States, in carpet factories in Pakistan, and among trafficked women. Black History Month can be a springboard for learning about the much broader story of human slavery, in the past and in the present.

Marjorie Gann has written two books on slavery together with Janet Willen. The first, Five Thousand Years of Slavery (Tundra, 2011) was a 2012 Notable Book for a Global Society, Children’s Literature and Reading Special Interest Group of the International Reading Association. Their second book, Speak a Word for Freedom: Women Against Slavery (Penguin Random House/Tundra, 2015) tells the stories of fourteen women who have fought against slavery.

January 27, 2020

STEMinism Sunday: Patricia Bath and the Fight for Sight (part 2)

Dr. Patricia Bath is featured in my kids book about pioneers in medicine!

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to get to know some of these intellectual badasses.

Imagine it’s the 1960s and you’re a black person in the USA. Congratulations – you’re twice as likely to be blind as a white person.

I hope that fact makes you as mad as it makes me! It made Dr. Patricia Bath mad, too, but, because she was a good scientist, it also made her curious. As she began researching reasons for this disparity, Bath discovered that the most common cause of blindness in white people at the time was old age; in contrast, the most common cause of blindness in black people was glaucoma – a disease that can be treated if it’s caught early. Many black Americans, however, didn’t know the early signs of glaucoma, purely because they didn’t have the same to access to medical education or affordable health care. As a result, they were suffering in ways their white neighbours weren’t.

Bath set out to change that, and invented an entirely new branch of medicine called community ophthalmology. Instead of waiting for patients to come to doctor’s offices for care, health care workers (both professionals and trained volunteers) met with patients in schools and seniors’ centers and other spaces in the community. They gave kids eye exams, identifying those who needed glasses to help them succeed in school. And they screened people for eye diseases, identifying and treating problems before they caused blindness.

Because of Bath’s work, thousands of people who might have gone blind still have their sight. Today, community ophthalmology is used to help people all over the world.

A founder of the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness, Bath continued her fight for sight until her death in 2019.

To learn more, check out my first post about Patricia Bath, or read her profile on this great website all about women in medicine.

January 20, 2020

Cantastic Authorpalooza: Sylvia McNicholl

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Sylvia McNicholl

. Take it away, Sylvia!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Sylvia McNicholl

. Take it away, Sylvia!

The Great Mistake Mysteries and Growth Mindset

Sometimes I find it’s hard to stop being angry with yourself when you make a stupid mistake. Berating yourself then leads to a feeling of inadequacy which can easily morph into anxiety and a lack of confidence to try something new.

That’s me, a writer with over thirty years of experience and at a certain age where I’m feeling my vulnerability. However, I’m shocked to find kids feel this way too.

One six year-old boy told his mother not to replace the mittens he lost—he wasn’t worth it because he was only going to lose them again. Heartbreaking.

In writing workshops I hesitate when kids talk about the “good” copy of their story in contrast to their first draft. Is a first draft a bad copy? It contains all the energy and excitement of a brilliant idea. So what if you need to add a layer of detail or fix a plausibility or time issue. When I mentor emerging adult writers, too, they often email anguished questions—should they reveal a detail now or later? Should they end the chapter here or there? Should they get rid of this character, add a love interest?

Just try and see! There is no one right way. We have to try new paths for our stories (and our lives!) even though they don’t end up being the final ones. We’re playing and practicing to become stronger. Developing resilience. Growth mindset is the new educational buzz phrase for this.

Just try and see! There is no one right way. We have to try new paths for our stories (and our lives!) even though they don’t end up being the final ones. We’re playing and practicing to become stronger. Developing resilience. Growth mindset is the new educational buzz phrase for this.

Which is why I wrote The Great Mistake Mystery Series.

Writing the Mistake Mysteries became therapy for me. If I made a spectacular mistake, I rubbed my hands in delight and thought how to write it into the plot. The stupidest mishaps make for the best stories, after all. That’s how I comforted myself when I accidentally pushed off with someone else’s grocery cart complete with their purse and wallet, or threw away my new health card instead of the old one, or printed off nine copies of my latest chapter to critique with my writing group and then left them behind and read out loud instead from my computer screen.

Twelve year-old Stephen Noble walks two dogs Ping, a Jack Russell who resembles my own dog, and Pong, a greyhound who behaves a lot like the grand dog I often look after. An intense observer of life, Stephen counts and analyzes his and others’ mistakes and they become the chapter headers. He makes ten mistakes a day over a three-day mystery—so thirty error-chapters a novel, unless someone makes a bonus boo boo. At the end of the story he solves the crime with the help of 12 year-old Renée Kobai whose great weapon is pizazz. When life gets her down she dresses even more sparkly. Always the solutions to the gentle neighbourhood crimes involve the help of Ping and Pong, and often they’re informed by Stephen’s mistakes.

When I visit classrooms I invite kids to trade their mistake adventures in for the story of a famous invention that arose from error. I talk about my days’ mishaps, how I sent my husband off with a defrosting steak instead of his actual lunch—same bag—what a mis-steak, hahaha. Go read how that gets written into the Best Mistake Mystery!

So hopefully children, and maybe adults, will learn from Stephen to look more closely at theirs errors, squeezing the juices of discovery from them. Celebrate the brilliant recoveries we make, such as when we track down a cell phone that fell off the top of the car where we put it when we needed a free hand to open the door. Finding something like that requires keen detective skills. Or if nothing else, learn compassion for others who inconvenience us with their errors.

“I’m sorry.”

“That’s okay, we all make mistakes.”

Mistakes are great. Enjoy yours.

January 13, 2020

Mad Science: The Brides in the Bath Murders

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

I’ve been watching Murder Maps on Netflix recently (because what’s more Christmasy than murder?) and if you’re into forensic science, it’s solid viewing – a sort of historical Forensic Files, but with more social context. So far, S1E4: The Brides in the Bath Killer is my favourite, probably because I first came across this case while researching my YA book on the history of forensics, Forensic Science: In Pursuit of Justice.

I’ve been watching Murder Maps on Netflix recently (because what’s more Christmasy than murder?) and if you’re into forensic science, it’s solid viewing – a sort of historical Forensic Files, but with more social context. So far, S1E4: The Brides in the Bath Killer is my favourite, probably because I first came across this case while researching my YA book on the history of forensics, Forensic Science: In Pursuit of Justice.

Short version: Not one, but three of con man George Smith’s wives (he had seven altogether) drowned in their bathtubs. That’s unlikely enough to begin with, but when you consider that the deaths occurred very soon after their marriages, and that new wills and life insurance policies were involved, well… it’s not surprising that Scotland Yard started giving Smith the hairy eyeball.

British pathologist Bernard Spilsbury handled the forensic side of the investigation, which was challenging, because there were no signs of struggle or injuries on the victims to suggest they’d met with foul play. Autopsies showed that they really had drowned, but it just didn’t seem possible that one man would have three wives who’d met with identical accidents, even if, as Smith claimed, the women may have suffered from epileptic seizures.

But how could Smith have held the women under long enough for them to drown without leaving a single bruise on their bodies?

Spilsbury, like any good scientist, suggested that Detective Inspector Neil conduct an experiment. By today’s standards, the approach was pretty shocking: he found a female volunteer and filled up a bathtub. How Neil convinced the woman to get in it, I have no idea, but she was a strong swimmer, so it’s likely everyone figured she’d be fine. That assumption was almost fatal. After first trying to force her under the water, Neil grasped the volunteer’s ankles and pulled. To everyone but Spilsbury’s astonishment, she was instantly rendered unconscious!

Modern science suggests that water rushing into her nose and mouth put pressure on the vagus nerve in her neck, causing the faint. The volunteer was pulled from the tub and resuscitated, but Smith’s wives would have drowned before they regained consciousness.

Dastardly crimes, seriously cool science, and some jaw-dropping (but luckily non-fatal) experimentation – it’s no wonder that this case is a landmark in the history of forensics!

Want more? Check out one of my four children’s books on forensic science, or better yet, contact me to schedule a school visit! My forensic science programs are a huge hit with grades 7-12.

January 6, 2020

Teach Write: What Is an Essay For?

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Happy New Year, and welcome to January, also known as “the start of a new semester.” Which means it’s a perfect time to talk about the most common form of writing assigned by university professors – the essay. Students in high school, colleges, and other institutes of higher learning will also find today’s column helpful, as we answer the question “what is an essay for?”

First, a caveat – there is more than one type of essay. If you’re in any way uncertain about what your instructor is asking you to do, find out! Trust me, getting some clarity before you start writing will save you a whole lot of time down the road. But for our purposes today, we’re going to focus on the most common type of academic essay: the argumentative essay.

As you may recall, we’ve been talking about the importance of understanding the purpose of what we’re writing before we actually start. Unlike other forms of writing, where the goal can be a bit more obscure, the purpose of the argumentative essay is right there in the name:

To make an argument.

But let’s take that one step further and ask, “What is the purpose of an argument?”

If you answered, “To convince someone that I’m right,” you get a gold star.