L.E. Carmichael's Blog, page 19

June 14, 2020

STEMinism Sunday with Conservation Biologist Rina Nichols

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to learn more about these intellectual badasses. Today, we’ve got a guest post from conservation biologist and children’s writer, Rina Nichols.

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to learn more about these intellectual badasses. Today, we’ve got a guest post from conservation biologist and children’s writer, Rina Nichols.

I have always loved animals and nature—and it was in my first year of university when I discovered that there was an entire field of science dedicated to conserving them, called conservation biology. That was also the year I read Dr. Goodall’s In the Shadow of Man for the first time. I was hooked.

I went on to receive a B.Sc. in Biology at Acadia University; followed by a graduate degree in Biopsychology (animal behavior) at Memorial University.

Then, for the next 18 years, I was lucky enough to travel to some amazing places across the globe like Mauritius (land of the ill-fated Dodo), the Caribbean, and Madagascar to study and help endangered species.

The goal of conservation biology is to maintain the planet’s biological diversity (biodiversity). So basically, it is a science born from the impact that humans have on nature. But it differs somewhat from other biological sciences because it is a crisis discipline. Meaning, sometimes conservation biologists must act quickly to help protect a species or a habitat before knowing all the facts (not ideal, but reality) – thus, it is a science driven by adaptive management.

Many of the ideas, techniques and methods used in conservation biology come from other biological fields including ecology, biogeography, ethology (think Jane Goodall!), systematics, genetics, evolution, animal husbandry, and veterinary science. It also incorporates social sciences like resource economics and policy, ethnobiology (the study of how different cultures utilize and treat living things), and environmental ethics.

To show how conservation biologists try to help maintain biodiversity, I’ll use one of my past field missions as an example.

This little creature is the narrow-striped mongoose or bokiboky (it’s Malagasy name, and yes for those creators out there, it’s pronounced bookie bookie). It is a small carnivore found only in Madagascar. The closest Canadian comparison would be our pine marten.

This little creature is the narrow-striped mongoose or bokiboky (it’s Malagasy name, and yes for those creators out there, it’s pronounced bookie bookie). It is a small carnivore found only in Madagascar. The closest Canadian comparison would be our pine marten.

Studying the bokiboky was an adventure. I was part of a team of international and national biologists who traveled to the western coast of Madagascar and set up camp (a very rudimentary base camp) in a remote dry deciduous forest—in the middle of nowhere—to search out and study this elusive species. Only one other study had been carried out on the species way back in 1976, so there was a lot to learn. We set out live-trapping grids throughout the bokiboky’s suspected range and carried out mark-recapture sessions. For each captured animal, we recorded their age, sex, health condition, breeding status and collected genetic samples (its taxonomic status was unclear). This gave us information on the population size, distribution and demographics.

We also wanted to study what factors were impacting the population. Could it be habitat loss/degradation or invasive species or poaching? Was there something about the species’ biology or ecology that was making it more likely to be endangered? We conducted standardized habitat sampling and walked forest transects looking for signs of habitat loss (clear-cutting), invasive species and poaching traps. Then, we visited villages in the surrounding area and surveyed the residents to find out what they knew about bokiboky and talked with them about their experiences and their knowledge of the mongoose.

We also wanted to study what factors were impacting the population. Could it be habitat loss/degradation or invasive species or poaching? Was there something about the species’ biology or ecology that was making it more likely to be endangered? We conducted standardized habitat sampling and walked forest transects looking for signs of habitat loss (clear-cutting), invasive species and poaching traps. Then, we visited villages in the surrounding area and surveyed the residents to find out what they knew about bokiboky and talked with them about their experiences and their knowledge of the mongoose.

By using a combination of ecological studies, genetics, social science and traditional knowledge, we uncovered new information about the bokiboky population and its habitat status. It was this combination of information across many disciplines that allowed us to make recommendations to help conserve and protect them.

And since the bokiboky share their habitat with many other species (including the world’s smallest primate, Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur) these recommendations help preserve the biodiversity of the area.

And since the bokiboky share their habitat with many other species (including the world’s smallest primate, Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur) these recommendations help preserve the biodiversity of the area.

Today, I am not so much trekking through forests of Madagascar as I am writing at my computer, both reports and stories about animals for youth. I live in Guelph with my partner who is director of a conservation NGO, our two tween-aged boys who are animal lovers, a Newfoundland dog, a royal python, a milksnake and a bearded dragon. I’m a part-time environmental consultant but my favorite thing now is talking to kids about biodiversity and conservation. I supervise a weekly Wildlife Club at a K-8 school and I give classroom presentations.

During my school visits, I’ve met many of our next generation’s scientists and ecowarriors: kids who love exploring the magic of the natural world around them—asking clever questions about nature and creating innovative ideas and activities that help our planet. They understand, better than I ever did at their age, that the planet needs our help.

June 12, 2020

The Final Forest Friday

In the three years I spent working on The Boreal Forest and preparing to release it into the world, I never in my wildest dreams expected to have to do it during a pandemic. And it’s been both harder and more hopeful than I could have imagined. I lost opportunities to celebrate… but new ones arose that wouldn’t have been possible under other, more “normal” circumstances. I’ve learned things and met people, and been so proud to see how members of the literary community came together to support each other – not to mention all the kids and parents and teachers whose lives were instantly turned upside down.

Huge thanks to my partners in online promo:

Kids Can Press and the members of the Spring Reading Relay (check out my video before it’s gone!)

Erin Thomas and Centennial College

Carmen Oliver, Darren LeBeuf, and the International Day of Forests

Stephen Hurley and VoicEd Radio

And a special shout out to the readers, teachers, bloggers, and bookstores who contacted me online, or bought a book, or told your friends to buy my book. I couldn’t do this without you. Thank you all!

Today is your LAST DAY to ENTER THE GIVEAWAY, or to contact me for a signed bookplate for your copy of The Boreal Forest. So don’t delay – send me your request by 11:59 Eastern Time.

Contest closes soon – enter now!

Contest closes soon – enter now!

June 8, 2020

Cantastic Authorpalooza: Medea Kalantar

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Medea Kalantar

. Take it away, Medea!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Medea Kalantar

. Take it away, Medea!

I was born in Georgia, USSR and immigrated to Canada when I was four years old. I lived in Toronto, Ontario for the most part of my life. I’ve been married to my husband Esfandiar for over 28 years and we have two grown children, Shanaz and Jean-Diar who are both married now.

Aside from being a children’s book author, I’m also a Reiki Master/Practitioner.

In the summer of 2018 my daughter Shanaz told me she was pregnant. When I found out I was going to become a Grandma it was a full circle moment for me, so I started to bake a honey cake in honour of my Grandmother. My Bebi taught me how to bake a honey cake when I was a little girl. As I was making the cake, I realized all the different spices the cake had, like cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, vanilla, coffee, brown sugar, and honey. It made me think of all the different ethnic mixes my new grand-baby would have and how they would be just like this honey cake I was baking. The words and stories started to pour out of me. The fact that I have no formal training as a writer didn’t stop me from trying. I always wanted to write my biography someday, later down the road, because I’ve had so many hardships in my life that I had to overcome. But I never had any intention of writing— especially not a children’s book series. But the universe sent me a sign, and the messages were in me to share, and they simply had to come out. I wrote five books in four days, I couldn’t stop. Clearly the universe had something planned.

Like I’ve previously stated, I never set out to become a writer, so I had no clue what to do with the stories I’ve written and how I was going to get them published.

The biggest challenge I had to face was, fear: Fear of failure, and fear of the financial impact on my family since I was independently publishing my own books. As I was facing my fears I remembered a quote by the late and great Maya Angelou:

Hope and fear cannot occupy the same space. Invite one to stay.

So, I released my fears and chose hope. I’m so glad I did because my books have been welcomed with open arms and I’ve received such positive feedback from so many people. The most rewarding experience has been the outpouring of messages I’ve been receiving from people around the world. I’m beyond grateful and so happy to see that my books are making a positive impact.

All the characters and illustrations in all my books are a cartoon version of my actual family. Nala is the only fictional character, and she is based on my grandson Lukenzo. My daughter Shanaz and son-in law Brandon welcomed our first grandchild, on March 2, 2019. Our beautiful little Luka has a mix of Georgian, Persian, (Shanaz) Jamaican, Chinese, Portuguese, Indian and Guyanese (Brandon). This unique mix is a perfect recipe, and it’s the reason why I call my grandchildren my little Honeycakes.

There so many children in the world now that have diverse multicultural families like mine, and there still aren’t many books that represent them. At the end of the day we are all Honeycakes, we all have a little bit of spice in us. With all the negativity around diversity in this day and age, I feel it’s very important to create books with a more positive message to help caregivers teach children to accept others, help children to become more balanced, kind, grateful and honest. Books to help children manage their emotions when things don’t go the way they hoped. I always say there is no such thing as winning or losing, there is only winning. You win when you reach the goal you wanted to achieve or you win by learning a very valuable lesson. It’s all about perspective and how you look at things. Giving children these tools at an early age will help them grow into happy and fulfilled adults that aren’t stressed out, but live in harmony with a healthy mind, body, and spirit.

Visit Medea’s website for more information on her inspiration and her books. You can purchase each book in the series here:

Visit Medea’s website for more information on her inspiration and her books. You can purchase each book in the series here:

Honeycake: “Help, I Swallowed a Butterfly”

Honeycake: Special Magical Powers

June 5, 2020

How Can We Preserve The Boreal Forest?

Announcements!

Announcements!Happy World Environment Day! Do something good for planet today – just remember to wash you hands and wear your mask.

The giveaway ends in ONE WEEK. Get those entries in! And if you’d like a signed bookplate for your copy of The Boreal Forest, make sure to contact me by June 12.

A Boreal Bouquet of Conservation Organizations

Last week we talked about some of the reasons that the boreal forest matters – not just to those of us who live there, but to the entire world. This week, I wanted to draw your attention to some forest and nature focused organizations that you can contact for more information, or if you’d like to get involved in boreal conservation. This is a small sampling of Canadian or provincial organizations based in Ontario (where I currently live). If you’re looking for something closer to you, do a Google – there are a ton of other great groups and resources out there.

In addition to general information and ways to get involved, the Forests Ontario website has links to lesson plans, fact sheets, and other forest-activities for families and educators.

Ontario Nature has an annual conference AND an annual youth summit. There’s a ton of boreal forest information at this link.

Birds and bugs and other wildlife! Also some fascinating information about Canadian Indigenous peoples and the boreal forest.

This one’s for people who want to get their hands dirty and actually plant a tree. They have urban forest programs, too.

Great info for kids, including a Young Leader Grant. Also info on backyard nature, as well as boreal.

Want to see the boreal forest in person? Parks Canada is a great place to start – you can also check for provincial parks in the boreal forest near you.

Do you know of other organizations that are working to protect the boreal forest? Have suggestions for citizen science projects or other ways “ordinary” people can get involved? Please share your resources in the comments!

Time’s running out on the giveaway – enter now!

Time’s running out on the giveaway – enter now!

May 29, 2020

What Is a Forest For?

Announcements!

Announcements!Reminder that both the giveaway and the free signed bookplate offer expire June 12, so if you haven’t taken advantage of those yet, make sure you do.

And now, on to this week’s instalment of Forest Friday!

What is a Forest For?

When I was writing The Boreal Forest, one of my goals was to shine some light on ecological processes – by showing how a forest works, I could hopefully show what a forest is for… by which I mean, why do we need forests anyway?

The obvious answer is that forests provide habitat for animals. Billions of birds live in or visit the boreal forest, and that’s just birds – there are mammals and reptiles and fish and insects and spiders and, well, an endless list of other critters both great and small (ask me about soil bacteria!). In other words, the boreal forest matters because of the biodiversity of plants and animals that call the biome home – many of which live nowhere else on earth.

The forest matters to people, too. In my first Forest Friday post, I mentioned a few of the many, many Indigenous nations that live in boreal forests around the world. There are also millions of non-Indigenous people within the biome… and the forest influences the quality of life of billions of others across the globe who will never take a walk in these particular woods. How? Through functions that scientists call “ecosystem services”:

Supporting nutrient cycling and soil formation, allowing plants to grow

Primary production – “science speak” for the plant photosynthesis that converts sunlight into chemical energy… also known as “food.” That includes food for animals, but also wild food products like mushrooms, berries, and medicinal plants

Primary production also leads to trees, which lead to lumber and a huge range of wood and paper products that are… pretty darn essential to modern life

Cleaning water, preventing flooding, slowing erosion

Climate regulation

During photosynthesis, plants remove CO2 from the air, releasing oxygen. That reduces the concentration of greenhouse gases in the air, but is also crucial to our ability to keep breathing

Plants convert CO2 to biomass (living plant matter), and trees especially can trap that carbon for years

Enormous amounts of carbon are also stored in forest soils, peat, and permafrost, a third way the biome slows climate change

The boreal forest also influences local weather patterns and helps break down ozone in the air (ozone is awesome high up in the atmosphere, but pretty dangerous down low)

That’s a LOT of reasons why the boreal biome matters to all life on Earth. But there’s one more. It’s not economic or environmental – it’s cultural, spiritual, aesthetic, educational, recreational…. it’s all of the important, intangible benefits that a living forest offers to the human heart, mind, and soul. If not the most important reason to protect this vast and vital wilderness, definitely the most personal.

So let’s get personal today. What does the boreal forest mean to you? Share your thoughts, feelings, and encounters with boreal wildlife in the comments – I would LOVE to hear your stories.

Contest closes soon – enter now!

Contest closes soon – enter now!

May 25, 2020

Teach Write: Five Tasks to Complete BEFORE You Start Writing

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers and students can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers and students can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

For the last few months, we’ve been talking about the first two things we must do before we sit down to write:

Identify our audience

Who are we writing for? Kids, adults, professional peers, our teachers?

What does that audience need from our work?

Identify our purpose

What is our goal as a writer? To entertain, inform, persuade?

What is the goal of the type of document we’re writing? To make an argument, to present scientific results, to evoke emotion?

These tasks fall under the “preparation” phase of writing. In the three-step writing process, preparation is the first 40%…. meaning the first 40% of the total amount of time and effort that we put towards a particular piece. Click here to access posts that dig into these topics in more detail.

Perhaps, at this point, you’re thinking that we’re about to get on with the actual writing now.

Hahaha – no. Stow that misplaced enthusiasm and put down your pens.*

Nope, my friends, there are still several things that we really need to do before we are ready to begin with the making of the words:

get an idea

do the research

outline

Granted, not all of these will apply to every project. If you’re a student, a freelancer, or a children’s writer doing work-for-hire projects, the idea might have been handed to you. In which case, all you have to do is brainstorm to flesh it out. Likewise, not every project requires research… but a lot more projects need it than you might think.**

The hill I will die on, though? The outline. Unless you’re a poet, outlines are not negotiable. And even then, I’m willing to bet they help.

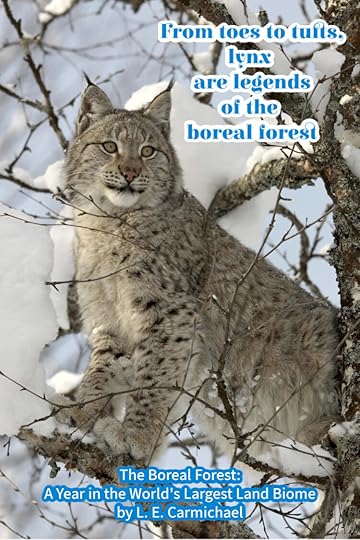

May 22, 2020

How Do You End a Book, Anyway?

I was supposed to be prepping for the Nova Scotia leg of my book tour this week, but, well, that’s not happening. And that’s OK, because quite frankly, the idea of traveling right now is just a little too scary. Possibly because Tech Support (who has an essential medical job that requires him to travel) recently returned from Nova Scotia and between the apocalyptic emptiness of the airport and the fact that it was basically him and a box of lobsters on the entire airplane, I think I’m good right here. I hope you are, too.

Let’s dive right on in to the final deleted scene in my Forest Fridays series! Next week, we’ll start looking at conservation in the biome.

Deleted Scene – The Last Scene

This is the original draft of the final scene in The Boreal Forest:

Snow falls from a flat grey sky. It hisses in the steam that rises from a hotspring. A snowshoe hare laps at the warm water. She nibbles on a willow, balancing on big back feet.

Snow crunches beneath a lynx’s stalking paws. The hare’s ears twitch and the cat stills. The hare relaxes. The lynx leaps. Hare in his jaws, he climbs a tree to eat . The spruce shivers and—whoomp!—snow falls.

Katie Scott, my very brilliant editor, pointed out (gently) that it might not be the best idea in the world to end the book with bunny blood. It is, after all, a touch grim. Perhaps instead of death, she suggested, we could refocus on the idea of rebirth and renewal.

Katie Scott, my very brilliant editor, pointed out (gently) that it might not be the best idea in the world to end the book with bunny blood. It is, after all, a touch grim. Perhaps instead of death, she suggested, we could refocus on the idea of rebirth and renewal.

While it pained me to cut the only cat in the book, (Sorry, Sasquatch!) I had to admit she had a point. Instead of murder, we decided on mating. Or rather, a competition for mates – this is a kid’s book, after all! I chose porcupines because:

they mate in Alaska during the month in which the scene is set

they are ridiculously cute

I got to add a sidebar that allowed me to use the word “porcupette.”

Bonus fact – did you know that the most common cause of death for porcupines is actually falling out of trees? It’s true. For animals that spend so much time shinnying up trunks and waddling along branches, they are actually really, really bad at it. A lot of these falls happen during mating season, when males fight each other while 30 feet up.

Second bonus fact – the fisher is the only wild animal that preys on porcupines. I will spare you the details of their hunting strategy, because fishers are MEAN, and it’s kind of gross. Google if you really need to know!

Totally bonus bonus: watch this totally bonkers video of a lynx chasing a squirrel through the treetops near Drayton Valley, Alberta.

How do you feel about endings? And porcupines? And big-footed cats? Click Comment and tell me all about it! And if you haven’t already, make sure to enter the giveaway and to contact me if you need a signed bookplate for your copy of The Boreal  Forest (offer valid until June 12).

Forest (offer valid until June 12).

May 17, 2020

June Steube On the Art and Science of Nature Illustration

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to learn more about these intellectual badasses.

A special treat today: an interview with illustrator June Steube! June’s specialty is science and nature illustration, and she’s worked for clients as diverse as Canada Post and the Canadian Museum of Nature. She’s currently illustrating her first children’s book, but she still found time to stop by and share some tips for anyone who wants to give their animal art a little more realism – not to mention personality!

What kind of research do you do to make sure your illustrations are scientifically accurate?

Usually, I begin with photo research using Google image search, books, and if possible, drawing and photographing a live animal or a specimen at a museum. I look up descriptions of the animals and their habits, noting especially what characteristics distinguish them from closely related species. When preparing illustrations for museums, I work closely with a scientific expert who will check the drawings for accuracy.

What steps do you normally follow when working on a new illustration?

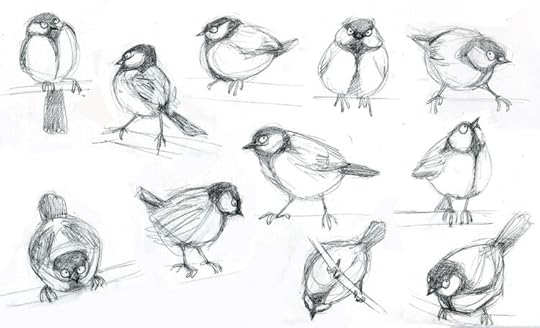

For nature drawings that don’t require strict scientific accuracy, I’ll begin by sketching the animal in many poses from various angles. I look for dominant shapes that are pleasing and that portray certain characteristics — such as pointy, long and leggy, and I exaggerate those. I will usually see a touch of emotion in some of the sketches – such as shyness, grumpiness, curiosity, or joy and will push that feeling in the facial expression, pose, and viewpoint.

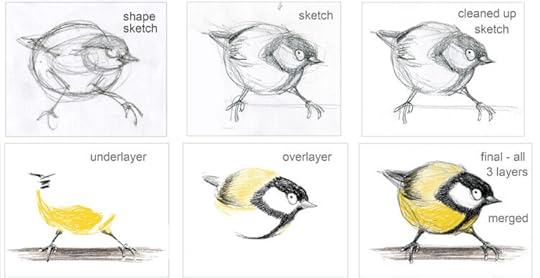

For my illustration work, I will further refine one of the drawings, scan it and use Photoshop for very small retouches such as the eyes, or at other times, for colouring the entire drawing. I ‘multiply’ the drawing in the layers palette then work on the colour in layers above and below the drawing. Some illustrations can have 3 layers and some detailed artwork with backgrounds can have as many as 40 layers or more.

How do you “fix” a drawing that doesn’t go the way you want it to?

I much prefer working in traditional media such as pastel or watercolour on paper or illustration board, but both the thrill of using that media and the drawback is, once you make a mark you usually can’t change it. I am not keen on using a computer but it allows me to do needed revisions and work faster.

I will usually redraw the revised section, scan it, and in Photoshop I will patch that portion over the area that needs to be altered. Sometimes it goes easily and other times a revision can be mind-numbing work that can go on for hours.

How do you give your animals movement and personality while still keeping them realistic?

I will add expressive eyes using the same techniques for facial expression that some animators use when they do character studies. The eyes will be more cartoonish and there may be added eyebrows. I may extend the mouth line into a smile or frown and may exaggerate features that I find comical, such as pouchy cheeks. Even the fur can express the personality with smooth fur showing a persnickety neatness and attention to detail or a wildly hirsute character carrying around its own population of fleas. The basic features can remain the same – a wolf can look like a wolf but you can choose to create a shy nervous wolf or a loud show-off wolf. I try not to overly sentimentalize animals but instead to create a moment of recognition.

Do you have any advice for kids who want to draw better birds?

Begin with basic shapes – a goose is like a wide bowling pin with a small head and triangular wings and a chickadee is a fat triangle with a circular head somewhat ‘set into’ the body. Look at the skeleton of a bird. When you draw a bird, imagine seeing through those feathers – where does the top of the bird’s legs meet the pelvis? Notice the backward bend at the ‘knee’ area before the leg meets the foot. Note the tail position and how the bird’s position affects where the legs and tail are — how they are both used as ballast to keep the bird from tipping over.

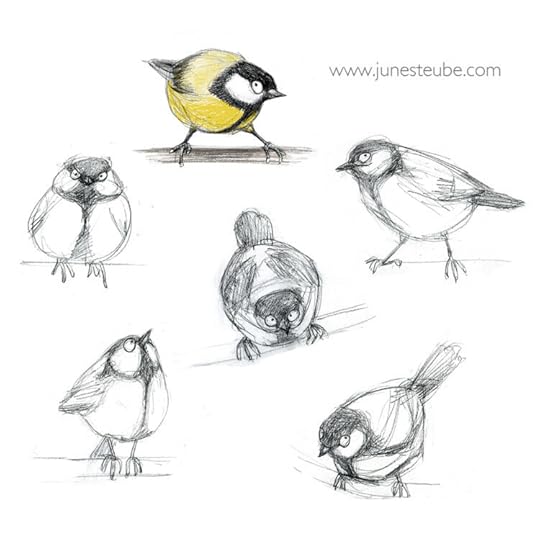

You can check out how I drew a Great Tit below, finishing with a grouped set of birds ready for my website portfolio or for sharing on social media. Why not try drawing your favourite bird using coloured pencils on paper or with your drawing app on a tablet?

Reference photo of a Great Tit, courtesy of Pixabay.com

Initial Great Tit character studies

Taking one drawing from a sketch to full colour

Final sketches arranged for social media

May 15, 2020

Hoards: Not Just for Dragons Anymore

Announcements!

Announcements!Have you entered the Rafflecopter giveaway for your chance to win the boreal forest prize pack? If not, scroll down to do so, and for a peak at the prizes.

Got a copy of The Boreal Forest and wish you could have it autographed? Well, you can, in a totally contact-and-COVID-free way. Drop me a note and I will mail you a free autographed bookplate for every copy of the book you purchase before June 12.

On to today’s foresty goodness!

Deleted Scene – Stocking Up for Winter

Pages 34-35 of The Boreal Forest show boreal birds migrating south for the winter. That scene originally included this snippet, showing a different winter survival strategy:

Red squirrels fill their winter pantries. One hauls a mushroom up a pine, wedging it between branch and trunk. Dangling from a nearby twig, a Siberian chickadee eyes the find. The squirrel chucks a warning—a sound like horse’s hooves.

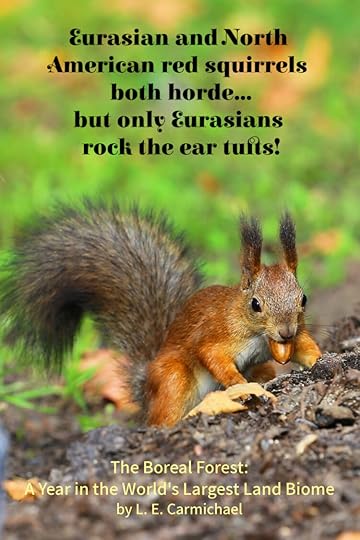

This scene was set in Russia, so these are Eurasian red squirrels (see below). Some scientists think they hide mushrooms in trees because this leads to air drying, which helps preserve the snack (mushroom jerky, anyone?). Second fun fact? Chickadees can actually dangle upside down! I would have loved to have seen that in the illustration…

This scene was set in Russia, so these are Eurasian red squirrels (see below). Some scientists think they hide mushrooms in trees because this leads to air drying, which helps preserve the snack (mushroom jerky, anyone?). Second fun fact? Chickadees can actually dangle upside down! I would have loved to have seen that in the illustration…

Extra bonus content: you can listen to the sounds Eurasian red squirrels make at this website (warning: you will likely spend hours perusing to their huge collection of animal recordings). I described the sound in the draft because, to my ears, it was totally different than the chattering sound Canadian red squirrels make!

Something else I found fascinating while researching this scene was that different animals hoard in different ways. The sidebar from the original draft:

Red squirrels and chickadees don’t migrate or hibernate. But food is scarce in winter, so they have to plan ahead. North American red squirrels store pinecones in mounds called larder hoards. One hoard contains up to 16,000 cones, enough food for 100 days.

Eurasian red squirrels hide cones and berries and mushrooms in many different locations. Chickadees also use this strategy, called scatter hoarding. It helps prevent theft, but requires very good memories.

Here’s an amazing fact about those chickadees – in one study, they stashed 170,000 separate food items from August to November, and an additional 30,000 from December to February. Data like that really make me wonder why “bird brain” is considered an insult!

Squirrels and chickadees are favourite backyard wildlife species – share your encounters with these critters in the comments! I love hearing from you.

There’s still time to enter the giveaway!

There’s still time to enter the giveaway!

May 12, 2020

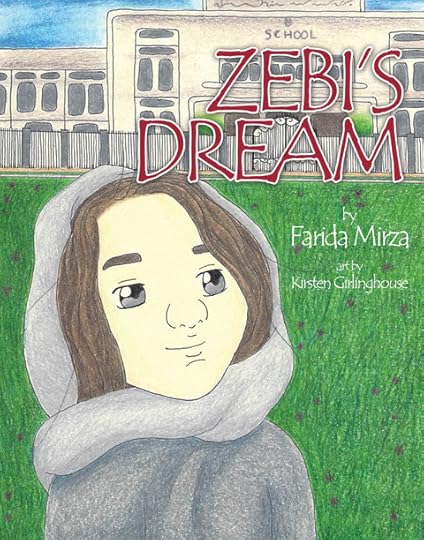

Cantastic Authorpalooza: Farida Mirza

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Farida Mizra

. Take it away, Farida!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Farida Mizra

. Take it away, Farida!

My memories of growing up in pre-digital South East Asia are rich with images of living in extended families, sharing lives and loves with relatives, friends and neighbours and enjoying lifestyles not driven by speed and material wants, but of leisure and simplicity.

There are also cringing memories involving injustices born out of prioritizing tradition rather than embracing changes.

My mother was homeschooled in Farsi and Urdu. My father however, like many young men, went to the UK to pursue his medical studies. There was an apparent gender inequality in formal education.

There was another kind of inequality. The poor had almost no access to public education.

Women, the underprivileged and the privileged, were not becoming aware of the new findings in child development that were creeping in through a slowly changing environment.

I became conscious of the ‘exploitation’ of children. I saw, not to my liking, innocent but ignorant adults not changing their ways while the world was changing around them. Girls were still married young rather than allowed to complete their education. Women were exploited in rich as well as poor households. Gender inequality seemed hard to accept by my young self.

As an adult, I came across the words, ‘I am to … learn’ (anonymous) and they affected me profoundly. The words had the potential to answer many of my questions, philosophical and mundane. I took them immediately to mean ‘learning’ as in education, while I decided to let them mull around in my mind for finer and deeper implications.

I’d always loved writing, especially compositions in my English class. My father took my siblings and me regularly to borrow books from a library. I grew up reading Grimm’s Fairytales, Aesop’s Fables and many fabulously illustrated children’s books. The illustrations and visions of a landscape and people different from my own fascinated me and stimulated my imagination.

My passion for writing was confirmed when I had to write an imaginary essay for my high school final exam: a day in the life of a farmer. I was so carried away by what I was writing that I forgot the time limit and had to stop midway. Luckily I was able to think of a quick conclusion!

Many years passed. After high school, there was university, marriage, children and jobs – years in which I was too busy to write. I did occasionally but it was sporadic and not as often as I wished; actually, it still isn’t.

My children grown-up, I decided to start writing with the aim of publishing. I decided to write for children. I wanted to write fun stories with something children could take away from.

I finally wrote three stories about Suraj, a tiger cub. Suraj teaches himself to overcome common childhood-related fears such as separation anxiety, inability to make friends and bullying. I decided to weave an important strategy into the stories – the strategy of ‘pausing to think out a solution before taking action’ when faced with a problem. Children do not always have a supportive adult around when they face a problem. The stories would make children aware of an option to find solutions independently. Children have tremendous potential that is often underestimated. As Dr. Seuss says, A person’s a person, no matter how small.

I loved writing the Suraj stories and I still love reading them. I sent the three stories to publishers in the US but received rejections. I decided to self-publish. Facing financial restraints, I managed to find someone who did the illustrations for me free because she had time and the inclination to illustrate a book. She is a great illustrator. However, because of personal commitments she had to stop the project half way. She had done the sketches but could not do the colouring. I found someone who did the colouring.

I self-published all three stories under one title, Suraj The Tiger Cub, as publishing three separate books was not viable. Soon after, when I was visiting my homeland in 2014, a children’s publisher saw a copy of my book. They offered to acquire it and publish it under the banner of Oxford University Press (OUP): you can find it in their catalogue, here. Since then, OUP has published five more books of mine.

I continued writing and self-published three more books on Amazon, Poems That Empower Children, I See Things From Where I Am, and Zebi’s Dream. Zebi’s Dream has recently been acquired by Waldorf Publishing and is available on their website.

Two of my books, Hala’s Window (OUP) and Zebi’s Dream (Waldorf) are about education, poverty and girls. My current WIP is a middle grade novel. To learn more, visit my website at www.fmirza.com.