L.E. Carmichael's Blog, page 17

November 9, 2020

Research for Writers: How to Find Experts

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers and students can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers and students can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Today we’re continuing our discussion of research, with a focus on a special type of primary source – the expert. First, what do I mean when I say “expert”? As a former scientist and writer of sciencey books, I tend to define “expert” as “scientist.” And that’s definitely one type, but it’s certainly not the only type.

An expert is anyone that’s got first-hand, factual knowledge or experience related to your topic. In other words, the topic you’re writing about will determine who you’re looking for in an expert and how to go about finding that person.

Note that today’s post is going to focus on experts who have special knowledge derived from their professions. The sensitivity or authenticity readers a fiction writer might need to consult are a totally different kind of expert – people whose expertise comes from the lived experience of their particular identity. Identity absolutely intersects with profession – consider for example, how the profession of “scientist” is experienced differently by a black woman compared to a white man. But for today’s purposes, we’re going to focus on how to find people whose factual knowledge is relevant to your writing, rather than people who are commenting from a place of personal experience.

Where do you find those kinds of experts?

Friends, Family, and Other Folks You Know

If you consider the circle of people you actually know in real life, you’ll probably realize just how many of them are experts in their own fields. Your cousin the lawyer, your favourite auto mechanic, and your friend who’s obsessed with model trains are all gold mines of untapped information. And the best part? You probably already know how to get in touch with these people.

November 3, 2020

Women at War: The Female Heroes of World War I

It’s almost Remembrance Day in Canada, so it’s high time for a special edition of Cantastic Authorpalooza. Today, I’m welcoming my not-so-evil stepmother, Jaqueline Carmichael, who is celebrating the release of her newest book, Heard Amid the Guns: True Stories from the Western Front, 1914-1918. Heard Amid the Guns compiles lesser-known stories of World War I, including those of the women scientists, medics, and soldiers featured in this post.

It’s almost Remembrance Day in Canada, so it’s high time for a special edition of Cantastic Authorpalooza. Today, I’m welcoming my not-so-evil stepmother, Jaqueline Carmichael, who is celebrating the release of her newest book, Heard Amid the Guns: True Stories from the Western Front, 1914-1918. Heard Amid the Guns compiles lesser-known stories of World War I, including those of the women scientists, medics, and soldiers featured in this post.

Rapid advances in transportation around the turn of the 20th century led to innovations at war. It was the horseless carriage—the automobile—that made it possible to mobilize everything from tanks to dove-cotes on wheels.

A “petit Curie,” ready to roll into battle

In her book, Women Heroes of World War I, author Kathryn J. Atwood looks at “16 remarkable resisters, spies, and medics.” Among them, a young Marie Curie. The two-time Nobel Prize recipient for groundbreaking work in chemistry and physics, Curie was the mother of more than a million X-ray diagnoses. She brought technology someone else invented to battle zones on wheels in the form of mobile X-ray units called “petit Curies” to search for shrapnel and bullets inside the wounded.

“She pressed through the many bureaucratic obstacles placed in her way,” Atwood writes.

Elizabeth Foxwell, author of In Their Own Words: American Women in World War I, blogs on individual women and their roles in the war at elizabethfoxwell.com.

“It’s heartening to learn of these women’s achievements in WWI despite obstacles, yet troubling to learn about stories of discrimination,” she said, citing the example of female physicians who were rejected from the Army Medical Corps because they were female, and told they could be accepted only if they went as nurses. “They found support through the National American Woman Suffrage Association, organized and sent all-female medical units to Europe, performed heroic service, and were decorated,” Foxwell says.

She has heard from people proud of their relatives’ service in the war, and others who are simply interested in learning more about women’s involvement in the war effort.

She has heard from people proud of their relatives’ service in the war, and others who are simply interested in learning more about women’s involvement in the war effort.

“Some stories I’ve uncovered have been poignant, such as that of Jennie Cuthbert Brouillard, who obviously had experienced Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and stated in an oral history, ‘After I come [sic] home, I couldn’t nurse anymore . . . I was just all worked up inside,’” Foxwell says.

Women achievers in science in the services during the Great War stand out not only for their accomplishments, but also for their rarity. STEM careers were often reserved for men, while women were most likely to find a role in nursing, a profession they could more safely pursue within Western society’s traditional roles of the day.

Foxwell cited groundbreaking nurse Marie X. Long of York, Pennsylvania as the first female lab assistant at Camp Greene’s base hospital in North Carolina. Long had trained three years in lab analysis and worked at the US Army Hospital in Lakewood, New York. She went on to publish scientific articles in The American Journal of Nursing.

A modest biographical note in her papers at her alma mater Hanover College tells us Indiana-born Rachel Emilie Hoffstadt developed an oral vaccine for typhoid while serving as head bacteriologist in the hospital lab at Camp Sevier, South Carolina. Hoffstadt was also an instructor of chemistry and bacteriology at the Army Nurses School. She was the groundbreaking first female grad of Hanover College to earn a doctorate—and she earned two, one from the University of Chicago and one from Johns Hopkins University.

Milunka Savic, history’s most decorated female soldier

Women played many other roles in the war as well. Groundbreakers included Milunka Savic, the original Hunger Games-style heroine, who dressed as her brother to take his place in the Serb Army. When she was found out, she asked her superior officer if she could stay and fight, insisting she’d stand in front of him until he said she could. Savic went on to become the most decorated female soldier ever, and during the Second World War she stood up to occupying Nazis, even when it meant spending time in jail.

Heard Amid the Guns is available now.

For another perspective on women and war, check out this post celebrating L. M. Montgomery’s classic novel of the homefront, Rilla of Ingleside.

October 26, 2020

An Interview With Karen Autio, Author of Kah-Lan and the Stink-Ink

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest: Karen Autio . Take it away, Karen!

What inspired you to write your new sea otter chapter book Kah-Lan and the Stink-Ink ?

It all began at the Vancouver Aquarium where the instant I first saw sea otters, I was smitten!

Cuteness overload! Especially when they linked paws! But it got even better. I was amazed to learn that in the wild, these marine mammals not only survive, they thrive, in the cold ocean near shore, hardly ever setting paws and flippers on land. Now that’s resilience. I had to learn how they do it.

For my short story in a children’s literature course, I chose a wild B.C. sea otter as the protagonist and dove into research. Did you know sea otters can close their nostrils and ears to dive? I wish I could do that!

For my short story in a children’s literature course, I chose a wild B.C. sea otter as the protagonist and dove into research. Did you know sea otters can close their nostrils and ears to dive? I wish I could do that!

After revising that story many times (and I mean dozens of drafts, switching from first person to third person, and morphing it into a chapter book then advanced picture book and back to chapter book!), it was finally published in 2015: Kah-Lan the Adventurous Sea Otter, illustrated by Sheena Lott.

In the original short story, Kah-Lan got into serious trouble and was rescued by community members. However, as I expanded my research (essential for any writing!), I discovered that untrained citizens should never attempt to rescue a sea otter in distress. The animal’s jaws and teeth are strong enough to crack shellfish and would have no problem crushing the bones of a person’s hand. Rather, people should keep their distance and call the Marine Mammal Rescue Centre. So, the sea otter rescue in the first story had to go.

In the original short story, Kah-Lan got into serious trouble and was rescued by community members. However, as I expanded my research (essential for any writing!), I discovered that untrained citizens should never attempt to rescue a sea otter in distress. The animal’s jaws and teeth are strong enough to crack shellfish and would have no problem crushing the bones of a person’s hand. Rather, people should keep their distance and call the Marine Mammal Rescue Centre. So, the sea otter rescue in the first story had to go.

When you’re told to delete a favourite part of your writing because it isn’t working in the story, it’s heart wrenching. But I trusted the advice of my critique partners and removed the humans-rescuing-sea-otter scenes. I thought they were gone forever. Who knew they’d spark a whole other book? After my first Kah-Lan book came out, I thought, What if a Marine Mammal Rescue Centre rescue of sea otters could be the focus of a story? Believe it or not, one paragraph from that original story appears intact in my new book.

Photo by Jeff George

What mentor texts influenced your writing?

There were several, and I’ll talk about two. In my childhood, I read Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty multiple times, revelling in being immersed in the world of horses from an equine point of view. It’s inspiring how Anna Sewell turned her time of being confined to her house into creative expression by writing this classic story published in 1877. I wore out my copy as a child and recently read it again.

Sara Pennypacker’s middle grade novel Pax was a mentor text for me with sections of her story written from the fox’s point of view. Through the ultra-sensitive pads of Pax’s paws and his never-wrong sense of smell, the reader encounters the world in a fresh way.

These stories and lighthouse keeper Jeff George’s photos of a lone wild sea otter near Lennard Island, B.C., inspired me to immerse myself in Kah-Lan’s watery world and bring the reader along.

My goal with Kah-Lan and the Stink-Ink was to write it entirely from a wild sea otter’s point of view, as non-anthropomorphically as possible.

Could you share an excerpt?

Illustration by Emma Pedersen

“The sound of water and air shooting up high makes Kah-Lan’s heart pound. He looks back.

It’s an orca spouting, heading their way!

Zid screeches a warning. They must hide in sea-trees or haul out on shore. Now.

But there is no sea-tree forest here. And these rocks are too steep to climb. The otters streak along the rocky coast to escape their enemy.

Whoosh. The orca speeds after them. The otters swiftly paddle closer to shore.

At the surface, Zid whistles, urging Kah-Lan and Gula to go faster. Kah-Lan desperately pumps his flippers. His legs quiver.”

What was the most challenging aspect of this project?

Making non-anthropomorphic sea otter characters relatable to young readers. I invented sea-otter-specific words (e.g. sea-trees (kelp) and stink-ink (oil)) that reflected Kah-Lan’s view of the natural world and understanding of the activities of furless ones (humans). One of the hardest parts to figure out was how to include human speech for the reader’s benefit but in a way that shows Kah-Lan’s limited understanding based only on the humans’ tone, volume, and actions.

All set for my virtual book launch!

What’s the most rewarding aspect of this project so far?

A critique partner saying she was riveted reading the story! And receiving the full endorsement of the story from Lindsaye Akhurst, Manager at Marine Mammal Rescue in Vancouver, BC. Now I can’t wait to hear what young readers think of Kah-Lan and his sea otter friends!

Children’s author Karen Autio writes animal stories and historical fiction and narrative nonfiction. She grew up horse-crazy and book-loving in Nipigon, Ontario, then majored in math and computer science at university. Karen’s love of family history and the tale of a Finnish silver spoon inspired her to begin writing for children. Her books have been finalists for several awards and Kah-Lan the Adventurous Sea Otter won the 2016 Word Award for Children’s Novel. When she’s not researching, writing, or working as a freelance editor, Karen enjoys canoeing, photographing wildlife, reading, and travelling. She delights in revealing nuggets of little-known natural history and Canadian history in her author presentations to students. Karen lives in Kelowna, British Columbia.

October 19, 2020

The Boreal Forest of Reading!

YOU GUYS.

The Boreal Forest has been nominated for a YELLOW CEDAR AWARD in the FOREST OF READING.

Kermit GIF from Kermit GIFs

If you’re not familiar, the Forest of Reading is the largest recreational reading program in Canada. Kids across the country can register to read the nominated books and vote for their favourites – last year, more than 270,000 kids took part. It’s a great way to get kids reading books, thinking about books, and talking about which books they like and why. I am absolutely thrilled that a book I wrote will be included in this process… and also a little embarrassed to admit that I have not personally read ANY of the other books in my category:

Thanks to CBCBooks for this lovely collage of the Yellow Cedar nominees!

So let’s fix that, shall we?

Kids participating in the Forest of Reading have to read at least 5 of the 10 books in a category to vote. I don’t get to vote – of course! – but I’m still going to read all 9 of the other Yellow Cedar nominees… and I’m going to release a series of videos explaining why I think every one of those books is awesome.

The first video will launch in January – stay tuned for details. And in the meantime, check out the amazing Canadian books nominated in EVERY category of the Forest of Reading!

Thank you, Ontario Library Association, for including The Boreal Forest in this year’s Forest of Reading Program!

October 12, 2020

Research for Writers: How to Find Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers and students can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

Last time we compared primary and secondary sources and talked about how to use them when researching writing assignments or creative projects. Today, we’re getting a bit more practical, with some tips for finding and accessing peer-reviewed journal articles, the gold-standard of primary sources. But first…

What IS Peer Review Anyway?

You know how factories have quality control systems in place to ensure that their products meet a certain standard before being offered to customers? Peer-review is quality control for knowledge. It’s a way of ensuring that the new facts and ideas that are produced during research are as accurate and trustworthy as possible, BEFORE they make it into print. Here’s the short version:

Researchers submit a paper describing their work to a professional journal

The editor sends the paper to 2-5 other researchers who are working in the same field

Those experts (the peers of the original researchers) review the paper for errors, flawed logic, bad research practices, alternative possibilities that should have been considered but weren’t, and anything else they think isn’t up to scratch

The authors of the paper have to make every single change the reviewers suggest, OR come up with really good reasons why not

If the editor believes the paper has improved enough, it will be published

It’s an extensive, time-consuming, chocolate-binge-inducing process* and it doesn’t always work… but it’s the best method yet invented for vetting new knowledge. This quality control process is the reason that journal articles are often considered even better sources of information than other primary sources, like interviews.**

Now that we know WHAT peer-reviewed articles are, let’s talk about how to get them. There are two methods, depending on whether or not you have access to a university library. We’ll start with “yes I do” and go from there.

Accessing Journal Articles Using University Libraries

First things first, you need to find yourself a database – a searchable digital index that includes information on articles from a whole whack of different journals. If you’re researching in the STEM fields, you want Web of Science. It is hands down the best source for science and technology. For other fields, ask the reference librarian to recommend a good database.

Reference librarians: best friends of both students and professional writers. Also, they are usually bored, so take them your questions and you’ll make their day.

Most databases will let you search by title, author, or keyword, depending on where you are in the process. Try a range of different keywords related to your topic, because you might get different results. If you need help navigating the database, who will you ask? That’s right, the reference librarian.

September 28, 2020

Lydia Lukidis: How To Research Nonfiction

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Lydia Lukidis

. Take it away, Lydia!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Lydia Lukidis

. Take it away, Lydia!

Once upon a time, I had a dream: I wanted to write nonfiction. Keep in mind, this was many years ago, and I came from a poetry and fiction background. I had been writing poetry since I was six, and also composed fictional stories. When I began my journey in the world of kidlit, I always assumed I would write fiction.

And I do. But in between the industry research, numerous webinars and the reading I was doing, the world of nonfiction began to call to me. I loved reading it and reading about it, so it only seemed logical that I should write it. Once I did, I immediately fell in love. Though, I admit I made some rookie mistakes along the way, so I’m writing this article to help steer other aspiring nonfiction lovers in the right direction.

My first mistake? Not including a bibliography! Oops. I wrote a slew of short stories and sent them to magazines such as Highlights. One editor responded immediately, and notified me she wouldn’t even read my article because I didn’t supply a bibliography. I felt embarrassed, but it was a pivotal learning moment.

You better believe the next articles I wrote contained bibliographies. I’ve been told that some editors flip to it BEFORE even reading your work. But, I made another fatal mistake: my references were not reliable and I had too many secondary sources. At the time, I had no idea what a primary or secondary resource was. In the words of author Susan Hughes:

A primary source provides direct firsthand evidence about the subject, so, for example, if you’re looking for historical information, a letter or photo or eyewitness account or a legal document would be primary sources.

A secondary source discusses or analyzes or comments on primary sources, so, for example, an article in a scholarly journal discussing someone else’s research or a book.

What I learned is this: you can’t just surf the web for a few hours and complete your research. You have to dig deeper, become a quasi-detective, and track down reliable sources. Here’s a short list of research tactics I find useful:

Find experts!

You’re likely not an expert on your topic, so it’s imperative that you find someone who is. Start with online interviews with experts and try to track down their emails. Searching university databases is effective, or use Profnet. In my experience, most experts are more than willing to speak with you. But it’s critical to come to these interviews prepared- don’t ask basic questions. Respect their time and write down a list of focused and specific questions only they can answer. For my STEM book THE BROKEN BEES’ NEST, I interviewed the head of a bee conservation organization, and she helped fact checked the text.

The library is your best friend!

You’ll be spending a lot of time here. Grab every book you can on your topic, and then choose a couch and get comfortable. Look through all the books, take notes, and borrow some to continue your research at home. A tip: don’t bother with books in the juvenile section because the information is too generalized. Find books targeted for adults, and bonus points if experts in the field wrote them.

Universities & specialized libraries are also your best friend!

Universities & specialized libraries are also your best friend!Universities often have a multitude of references that libraries don’t, so don’t be shy to check them out. Specialized libraries also open the door to rare texts. In addition, look up journals, periodicals, newspaper, and magazine articles. You can also purchase a membership to online resources such as https://www.newspapers.com/ and literally fall down the rabbit hole of nonfiction research heaven.

Government agencies = a goldmine!

Government agencies and departments also post a wealth of information and facts, free of charge. Here are a few examples that have come in handy with my own research:

https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/welcome.html

The internet has a million resources!

There are many other useful online resources. Here are a few I often use:

Internet Archive: https://archive.org/

Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/

Library of congress: https://www.loc.gov/

Smithsonian Libraries: https://library.si.edu/

LSU Library: https://www.lib.lsu.edu/

JSTOR online database: https://about.jstor.org/

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/

Pro Quest: https://www.proquest.com/

EBSCO: https://www.ebsco.com/

Online encyclopedias like Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/

The best part is, all these resources are free! But you’ll need to devote a lot of time to your craft, as you might not necessarily know what you’re looking for until you find it. But when you do, that’s when the magic happens. You’ll be able to formulate a unique hook that will set your book apart from others. Good luck to all you aspiring nonfiction writers!

About the Author

Lydia Lukidis is a children’s author with a multi-disciplinary background that spans the fields of literature, science and puppetry. So far, she has 40 books and eBooks published, as well as over 30 educational books. Her latest STEM book The Broken Bees’ Nest was nominated for a CYBILS Award. Lydia is also passionate about spreading the love of literacy and has been giving writing workshops in elementary schools across Quebec since 1999.

September 21, 2020

Happy Science Literacy Week!

All these kids’ science books are autographed and ready to give away to young readers this week!

Welcome to Mad Science Mondays, where we talk about depictions of science in movies, TV shows, books, and the media. We dissect the good, the bad, the comical and the outright irresponsible. Who says learning about science can’t be fun?

It’s Science Literacy Week!

*Fires cannons full of biodegradable confetti*

The brainchild of Jesse Hildebrand, Science Literacy Week started as a grassroots initiative meant to raise awareness about science: what it is, how it works, and why it’s awesome. It’s grown into a national celebration with a wide range of exciting programming – this year, safely socially-distanced or hosted online. It’s also the perfect antidote to the misrepresentation of science that I usually talk about on Mad Science Mondays!

As a scientist and science writer, Science Literacy Week is one of the highlights of my annual presentation schedule. This year, I am absolutely thrilled to be serving as Virtual Author in Residence at Queen’s University. I’ll be presenting to everyone from elementary students to student teachers to graduate students who need to polish up their sci comm skills. I’m also doing a couple of public events for the Kingston Frontenac Public Library, so if you’ve got a library card, come on (virtually) down!

Thank you to the Queen’s Community Outreach Centre and funding partners NSERC PromoScience, Canadian Wildlife Federation, and Science Odyssey presents Science Rendezvous for giving me this opportunity. I AM SO EXCITED!!!

I’m also going to be super swamped and probably a little stunned, so if you don’t see me around the internet for a few days, don’t worry – just drop a caffeinated beverage or two on my doorstep, and check out some of the amazing events happening across the country, all week long.

September 14, 2020

Research for Writers: Comparing Primary and Secondary Sources

Welcome to Teach Write! This column draws on my 20 years’ experience teaching writing to kids, university students, and adult learners. It includes ideas and exercises that teachers and students can use in the classroom, and creative writers can use to level up their process.

It’s September, which means school, which means writing assignments, which (often) means research. Research is a key part of the preparation phase for many writing assignments, not to mention for creative writers working on nonfiction projects or (usually) novels. Research is also one of my favourite parts of writing. I love learning new things – the weirder or more obscure the better!

What can I say, I’m nerdy that way. #ownit

We are going to be devoting many Teach Write columns to the intricacies of research for student and professional writers. Today, we are starting with the fundamentals: the difference between primary and secondary sources. Students need to understand this distinction, because teachers (particularly in college or university) will often require a particular type and number of sources in their assignments. Creative writers need to understand it, too, and not just because editors have a favourite (hint: it’s the first kind).

We are going to be devoting many Teach Write columns to the intricacies of research for student and professional writers. Today, we are starting with the fundamentals: the difference between primary and secondary sources. Students need to understand this distinction, because teachers (particularly in college or university) will often require a particular type and number of sources in their assignments. Creative writers need to understand it, too, and not just because editors have a favourite (hint: it’s the first kind).

Each type of source has advantages and disadvantages, and both have value. Let’s dig in!

Primary Sources

Primary sources are original, first hand sources of information. This is information held or presented by the people who created or discovered the knowledge in the first place. In other words, it’s your personal experience or someone else’s.

For research purposes, there are a couple major categories of primary sources:

peer-reviewed academic journal articles, where researchers publish first-hand accounts of their research

interviews with living experts, where expert can mean anything from a scientist to a carpenter to a pet groomer, depending on the topic and context

archival material like maps, diaries, letters, photographs and other materials produced by experts who are no longer living

Advantages of primary sources:

there is nothing between you and the original source of the information, increasing the chance that the facts you collect are accurate

they are full of odd, interesting, unique, and specific details that you won’t find anywhere else

Disadvantages of primary sources:

they are focused and specific and assume a certain level of background knowledge, meaning they are usually a terrible place to begin research on a new topic

journal articles are written for other experts, and tend to be pretty heavy going for the casual reader

they can be hard to access

academic journal articles are easiest to find using specialized databases, which most public libraries don’t subscribe to. And many journals are behind paywalls, so unless you have access to a university library, using these sources can be very expensive

reaching out to living experts can be very intimidating (more on this in a later column), and they may not respond before your deadline

In general, however, the advantages of using primary sources outweigh the disadvantages, so include them in your research whenever you can. Just don’t START there. Instead, I recommend starting with…

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources are – shocker! – second-hand information. This is information that has been collected, compiled, filtered, synthesized, or simplified from primary sources.

Categories of secondary sources include:

textbooks

popular nonfiction books for kids or adults

newspapers and magazines

documentaries

most of the internet

Advantages of secondary sources:

with the exception of textbooks, they are relatively easy to access online or through public libraries

they’re written for general audiences, like students (textbooks) or the general public (everything else), meaning they are usually easier to understand. This is especially helpful if you’re researching a brand new topic and need to get a handle on vocabulary or major concepts in the field

they often contain interviews with experts, providing names of people you can contact for more information

Disadvantages of secondary sources:

someone else stands between you and the original information, so you have to trust that

the author understood their own research and is explaining it correctly

the author has not introduced a bias or made conclusions that the original sources might not support

in the case of kids’ book, the author hasn’t simplified to the point of introducing inaccuracies

the information may be out of date – particularly in the case of books and textbooks, which can take several years to research, write, and publish

In short, secondary sources are a great place to begin research, but they have to be used cautiously and, ideally, in combination with primary sources. Personally, I like to get the basics from secondary sources and then use primary sources for confirmation, and for fresh, interesting details that haven’t already been reprinted in a million secondary sources.

September 6, 2020

Guest Post: Drones Over Your Head – Part 2

To learn more about Nidhi Kamra, visit her website.

Welcome to STEMinism Sunday! As a former woman in science, I have a deep and enduring interest in the experiences and representation of women in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). This series will be an opportunity for me – and you – to learn more about these intellectual badasses. Today, we have the second of two guest posts from Nidhi Kamra. To read Part 1, click here.

D for Dangerous

While selecting a drone, it is imperative to first define the mission. Missions fall under the Ds category – for example, Dull, Dirty, Dangerous, Difficult, Dash, Delivery etc. ‘Dull,’ synonymous with ‘boring,’ is exactly that – a mission that would have long endurance (many hours to days), like surveying a forest or urban area. A dirty mission would involve dealing with spraying pesticides, detecting chemical agents, radiation exposure etc. Dangerous missions are a lot of what the military is involved with, for example rescuing people from a war zone, fire etc. Based on the type of D, and several other factors, a drone must be selected that will perform the job best. Examples of more missions include providing telecommunications’ infrastructure, news broadcasts, hostage situation monitoring, crowd control when people go wild at a concert, building security, poaching detection, climatology, warfare etc.

Pick Your Drone

Once the mission is defined, picking the right drone is key. Most drones are either fixed wing (like an airplane where the wings are fixed), or rotary (like a helicopter where the wings are attached to one or more rotors and move). A mission that requires hovering over an area, perhaps to pick up or lower a parcel, is the job of a rotary drone because rotary drones can hover. If the mission requires monitoring pipelines by flying along the pipeline, a fixed wing drone would be a better option since these drones have longer endurance.

If your mission is to fly a drone for fun, there are many types available at hobby and electronics stores at affordable prices. Just attach a video camera and use it to capture bird’s-eye views of landscapes on your next vacation!

Drones can be classified based on size, endurance, capability etc. The Department of Defence categorizes them in groups based on weight, altitude and speed. The US Airforce classifies them in tiers, depending on if the drones are LALE (Low Altitude Long Endurance), MALE (Medium Altitude Long Endurance), HALE (High Altitude Long Endurance) etc. Drones will generally fall within categories inside the following parameters:

Weight: less than 250 grams to over 1000 kg

Range: distance is less than 10 km to over 2000 km

Altitude: flying height is 150 m to over 20 km

Endurance: flies continuously for less than one hour to a couple of days

If you own a hobby or toy drone, it’s likely a Micro or Mini UAV, weighing less than 25 kg (Or a few grams!), with endurance less than two hours, range less than ten kilometres, and chances are, you don’t have a license for it (though in most cases you should).

Here are some examples of cool drones:

DJI’s Spark mini drone can be launched from your palm, flown via hand gestures, and is the perfect companion for the selfie lover in you – you can take a selfie by making a square with your fingers!

This NAV (Nano Air Vehicle) was developed by AeroVironment. It looks and flies like a hummingbird. Drones that resemble and fly like birds are using “biomimicry.” The Hummingbird is equipped with a “spy camera” and can fly indoors and outdoors. It weighs less than one AA battery, and will only cost you pocket change — $4 million (though it’s not for sale to the general public).

Boeing’s Phantom Eye is a HALE (High Altitude Long Endurance) drone. It is designed for persistent intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (S&R), and communications missions. It has an endurance of four (or ten) days at an altitude of 65,000 ft. Since it cruises above the stratosphere, it is uninterrupted by turbulence, storms, and other aircraft.

NASA’s X-43A was a hypersonic drone, meaning it flew faster than the speed of sound. It was designed to fly up to 10 Mach. If an aircraft flies at the speed of sound, the Mach number = 1 and it is called a transonic flight. The speed of sound is about 343 metres per second. The X-43A holds a Guinness world record for speed. It was designed to test various aspects of hypersonic flights. These drones were not designed to land, and subsequent test versions of this drone crashed intentionally into the ocean.

Launch

While your hobby drone can be launched from the ground or your palm, some other drones are launched in different ways, depending on their design, mission, and performance characteristics. Some examples of launching methods are:

Conventional Launch: This is a runway launch and is the same as that of a passenger airplane, wherein the plane reaches a minimum airspeed and “takes-off” from a runway. A runway can be as small as your kitchen dining table, or as big as that in an airport. The drone requires energy from fuel or batteries to conduct a conventional launch.

Vertical Takeoff: These drones launch vertically like a helicopter, with the help of thrust, a force that allows the drone to lift. One advantage of vertical takeoff is no runway is required.

Catapult Launch: A catapult-like launcher is used to launch the drone with the help of bungee (elastic) cords. A catapult launcher can also be hydraulic (using oil and gas) or pneumatic (using pressurized gas) to assist with the launch. Since this type of launch is assisted, the drone’s battery or fuel is not used much for the launch process, and no big runway is required. This launch is perfect for landscapes that have a rough terrain.

Car or Boat Launch: When the vehicle or boat achieves the required takeoff speed, the drone is released. This method is again suitable in situations where there is no proper runway.

Air Launch: This launch method has a sci-fi flare to it. It involves “dropping down” drones from a host ship in the air at a considerable altitude. In this article, you can see a photo of drones called “Gremlins” (being built by a company called Dynetics) being dropped out of a C-130 Hercules aircraft to perform a specific mission. Once their mission is complete, these drones can be collected mid-air by the same aircraft.

Here’s a cool video of a catapult launch of the RQ-7 Shadow Reconnaissance drone:

Recovery

Like launch methods, there are several recovery (landing) methods for drones. The usual ones are conventional (like an airplane) and vertical recovery (like a helicopter). Some other interesting examples are:

Net and Cable-Assisted Recovery: Think of net recovery as scoring a goal in soccer wherein the ball lands in a net. Similarly, the drone is automatically guided to fly right into the net! With cable-assisted recovery, the drone gets stuck in a cable that helps it stop. These recovery methods are beneficial where there is no suitable landing area.

Parachute Recovery: In this method, a parachute is deployed by the drone and assists with slow landing speeds.

Don’t Monkey Around!

Before you venture into Droneland, check your country’s policies for drones to ensure you are flying safely and legally, as well as to avoid heavy penalties. Depending on your country, different organizations define regulations and policies for drone operators.

In Canada, Transport Canada asks operators to review the rules in the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) document before flying a drone for the first time.

Some points to note are:

Drone pilots must have a pilot certificate and only fly drones that are registered

A drone weighing less than 250 grams does not require a registration or pilot’s certificate. 250 grams is one and a half times as heavy as a hockey puck. Anything over 250 grams requires a license.

Children less than 14 years of age must be supervised

Children over 14 years of age can get a basic license, while those over 16 can get an advanced license

Your drone should always be visible

The drone should not exceed an altitude of 400 feet. That is about two times as high as the Cinderella castle in the Magic Kingdom (Disney World, Florida), or one fifths as tall as the CN tower in Toronto.

Do not operate the drone less than 100 feet from another person. That is five times as tall as a giraffe.

Don’t fly the drone in restricted areas like airports

Don’t fly if you are unfit in any way

Operate in open space, away from buildings, wildlife, obstruction, hazards etc.

To ensure you are complying with all the rules, visit the CARs website.

Well, that’s all for now, folks. Hopefully it didn’t all fly over your head. Perhaps next time you see a hummingbird, a bee, or a bat, you may be inspired to design your own drone, as long as you don’t use it to spy on your neighbour. But till then, be safe and have fun in Droneland!

For more information:

https://www.businessinsider.com/drone-delivery-services

https://www.businessinsider.com/commercial-uav-market-analysis

BBC News – Google Wing launches first home delivery drone service

https://time.com/rwanda-drones-zipline/

https://www.dronedeploy.com/resources/stories/oil-gas-pipeline-leaks/

https://www.gislounge.com/uavs-improve-pipeline-routing-process/

Wide Awake Films – Benefits of Using Drones to Capture Video

https://truefilmproduction.com/drone-videography-top-8-benefits-of-drone-video-for-businesses/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unmanned_aerial_vehicle

Airpower Journal – Spring 1991 – Unmanned Ariel Vehicles

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unmanned_aerial_vehicle#Canada

PenState College of Earth and Mineral Sciences – Classification of the Unmanned Aerial Systems

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._military_UAS_groups

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AeroVironment_Nano_Hummingbird

The Atlantic – Robot Hummingbird Drone Is Military’s Latest Spy Toy

https://www.dji.com/ca/guides/mini-drones

Boeing – High Altitude Long Endurance

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NASA_X-43

https://www.nasa.gov/missions/research/x43-main.html

https://sprudge.com/in-australia-the-coffee-drones-were-looking-for-are-here-139555.html

https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/mach.html

https://www.wetalkuav.com/new-us-military-drone-will-launch-recovered-mid-air-cargo-planes/

Dynetics – The Gremlins program Fact Sheet

https://www.butlerparachutes.com/military-parachutes/uav-recovery-systems/

https://www.tc.gc.ca/en/services/aviation/drone-safety/flying-drone-safely-legally.html

Designing Unmanned Aircraft Systems by Jay Gundlach

Nidhi Kamra is a picture book author. She currently has two titles under her name: Ten Sheep to Sleep, and recently released, Simon’s Skin. Her books can be purchased on Amazon and other online book stores.

You can also learn more about Nidhi Kamra on her website, or follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

August 31, 2020

Charis Cotter: The Tenacious Ghosts of Newfoundland

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Charis Cotter

. Take it away, Charis!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s writers! Today’s guest:

Charis Cotter

. Take it away, Charis!

Ghost. That one word has a strange power. All I have to do is announce that I’m going to tell a ghost story and children sharpen to attention. Grownups too. It seems that we are all touched by ghosts, whether or not we believe in them.

I’m often asked why I write about ghosts. It’s not an easy answer. I am intrigued by the unseen, the uncanny, the unsettling possibility that there is more to life (and death) than meets the eye.

Ghosts are a gateway for me. A gateway into the imagination. I use Newfoundland ghost stories in my books and in my storytelling to convey something of the culture and history of this unique island, but I also use ghosts in my novels to lure readers into a world that is just like the one they live in, but where ghosts are real. I like to suggest that reality is deeper than we are led to believe, and that imagination can take you into mysterious and profound places. Ghosts let me do this.

Newfoundland ghost stories have a particular draw for me. The landscape is perfect for ghosts: vast lonely barrens stretching on and on, a rugged and dangerous Atlantic coastline that has seen multiple shipwrecks, violent storms and disorienting fog. Many families have lived in the same community for two hundred years or more, passing down their ghost stories from one generation to the next. Where the only entertainment is what you create yourself, storytelling has been polished to a fine art in many a Newfoundland kitchen.

However, when I first went looking for Newfoundland ghost stories, I couldn’t find any. Everyone I asked said something like, “Oh my dear, what a shame, old Samuel Whalen could freeze your blood with his stories, but the poor soul passed just two weeks ago.” I quickly became convinced that the glorious Newfoundland oral tradition was on its way out and I had missed my chance. The received wisdom was that our modern technology—television, computers, internet, video games—had usurped the old stories, and no one was telling them anymore.

But with a little more patience I soon discovered that this wasn’t strictly true. Talk to any Newfoundlander for five minutes and they’ll tell you some kind of a story: they can’t help themselves. And while the old ghost stories aren’t being dished out around the kitchen table on a regular basis, those spine-tingling tales are still being told. Newfoundland ghosts have a persistent way of coming back again and again to haunt this very spooky island, no matter how much technology we are using.

Eventually I was lucky enough to meet some bona fide Newfoundland storytellers, the kind who make you laugh one minute and scare you to death the next. I hit the ghost-story jackpot when I began to work in schools, conducting writing and publishing workshops based on local ghost stories. I asked students to go home and ask their parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts if they knew a ghost story. The kids returned with the most wonderful tales: some had been passed down from one generation to another, some were more recent, some were different versions of the same story. Supported by ArtsSmarts and ArtsNL, I published two books of ghost stories with the students, getting everyone involved. The little ones drew pictures of ghosts and the older children wrote the stories. Knowing that I’d want to tell some of these stories, I sent home permission forms for the children and their parents to sign, agreeing that I could use their stories as inspiration for my own.

Eventually I was lucky enough to meet some bona fide Newfoundland storytellers, the kind who make you laugh one minute and scare you to death the next. I hit the ghost-story jackpot when I began to work in schools, conducting writing and publishing workshops based on local ghost stories. I asked students to go home and ask their parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts if they knew a ghost story. The kids returned with the most wonderful tales: some had been passed down from one generation to another, some were more recent, some were different versions of the same story. Supported by ArtsSmarts and ArtsNL, I published two books of ghost stories with the students, getting everyone involved. The little ones drew pictures of ghosts and the older children wrote the stories. Knowing that I’d want to tell some of these stories, I sent home permission forms for the children and their parents to sign, agreeing that I could use their stories as inspiration for my own.

I took a few of these stories and reimagined them from a child’s perspective, changing some of the main characters and circumstances, but keeping the essence of the ghost at the heart of the story. These became part of my storytelling repertoire, and then crept into my books.

Storytelling is a fluid art. One person will tell a story, then another will retell it, adding their own details. This is how stories survive, being passed from one person to another, changing and evolving as they are told and retold. So I find that I have become part of the oral tradition myself, as well as carrying the stories into the future in a different form.

With Halloween and the scary time of year approaching fast, I’m looking forward to telling my ghost stories in a new way this year. Thanks to COVID, my twelfth annual Ghost Tour of Newfoundland schools will be a little different—I’m hoping to go virtual and tell my stories to students with the help of the very technology that has been accused of squelching the old stories. A friend suggested I call it the Disembodied Ghost Tour. Works for me. And I daresay it works just as well for the tenacious Newfoundland ghosts, who still hover just outside the kitchen door, sighing in the wind, waiting to be invited in.

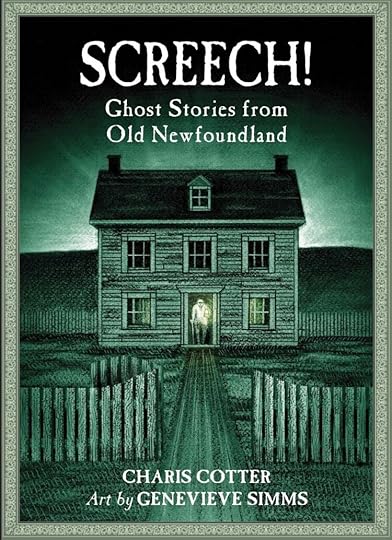

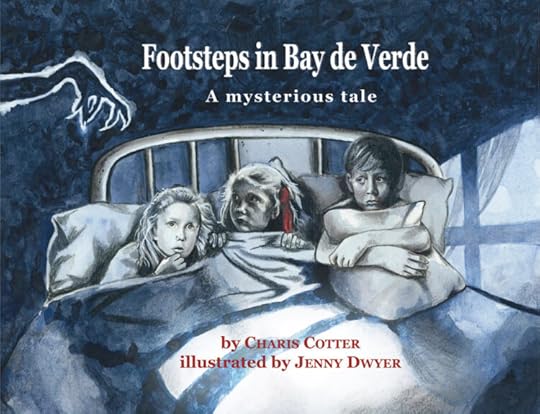

Charis Cotter lives near a cemetery at the end of a road in Western Bay, Newfoundland. Her latest books are Footsteps in Bay de Verde: A mysterious tale, illustrated by Jenny Dwyer (Running the Goat Books & Broadsides) and Screech! Ghost Stories from Old Newfoundland, illustrated by Genevieve Simms (Nimbus).

You can read more about Charis and her books here: www.chariscotter.ca