Michael May's Blog, page 89

November 7, 2017

His Kind of Woman (1951)

It's Noirvember, so I'm taking the opportunity to watch some film noir movies this month. Not gonna do one every day or anything, but I hope to cover one or two a week.

Who's In It: Robert Mitchum (When Strangers Marry, Out of the Past), Jane Russell (The Outlaw, Macao), Vincent Price (Shock, The Web), Raymond Burr (Rear Window, Perry Mason), and Jim Backus (Mister Magoo, Gilligan's Island).

What It's About: Gambler Dan Milner (Mitchum) is coerced by gangsters to stay at a Mexican resort for mysterious reasons. It sounds like an easy job, but it gets complicated quickly by the resort's other inhabitants, which include thugs and government agents, but especially a singer (Russell) and the famous, married actor (Price) she's dating.

How It Is: One of my favorite noir films, largely for the cast, but the setting plays a big part, too.

Most of the action takes place at the resort, which is a small enough place that everyone knows everyone else's business. It's full of colorful characters and reminds me of a tropical version of the resort in Dirty Dancing with lots of little dramas going on around the main one.

Mitchum is one of my favorite actors ever and he's got great chemistry with Russell. (So much so that producer Howard Hughes wanted them back together for Macao, which I also like; just not as much as this one.) The film doesn't ask me to believe that they're falling deeply in love, but there's a palpable connection between them that convincingly throws their other plans into question. Dan is a charming, likeable guy and Lenore Brent (Russell) is funny and easy-going, even though she's clearly got secrets and some tragedy in her past.

As the head of the gang that's manipulating Dan, Raymond Burr is neither as terrifying as his Rear Window character, nor as suave as Perry Mason, but he's intimidating as hell and makes the part better just by being in it. Backus isn't super important to the plot, but he livens up the place as one of the resort guests and I'm always excited to see him.

I've saved Vincent Price for last, because he's one of the best characters, but also one of the most out-of-place. He plays movie star Mark Cardigan, a married man who's having an affair with Lenore when she meets Dan. Dan isn't the only one to throw a monkey wrench into Mark and Lenore's relationship though. Mark's wife (Marjorie Reynolds) shows up partway through, determined to put an end to her husband's philandering one way or another. How Mark reacts to and deals with all of this is unexpected and priceless. I love the character.

Or I do until the climax of the movie. It's around then that Mark realizes that he's tired of just playing adventurers onscreen. As he discovers what's going on around Dan, Mark sees an opportunity to participate in a real adventure. Which is very cool, but the script turns him into a cartoon character after that. His dialogue becomes almost entirely quotes from Shakespeare and his decision-making is absurdly comical. Price is great at it - totally hamming it up - but the character doesn't fit the rest of the movie anymore. Mark doesn't ruin the movie at all, but he does keep me from loving it as much as I would if he'd been reined in.

Rating: 4 out of 5 plaid jackets.

Published on November 07, 2017 04:00

November 6, 2017

Mystery Movie Night | The Wizard of Oz (1939), Labyrinth (1986), and Mortal Kombat (1995)

David, Dave, and I are joined by special guest Rob Graham to talk about Gales, Goblins, and Goro. And after learning what connects them all, we reveal our favorite '80s fantasy movies.

00:00:56 - Review of The Wizard of Oz

00:17:56 - Review of Labyrinth

00:42:26 - Review of Mortal Kombat

01:16:25 - Guessing the Connection

Episode 19: The Wizard of Oz (1939), Labyrinth (1986), and Mortal Kombat (1995)

Published on November 06, 2017 04:00

November 3, 2017

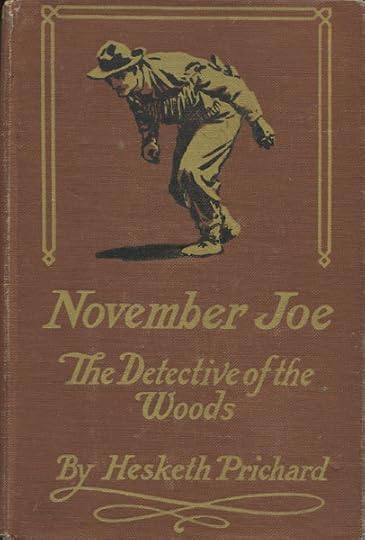

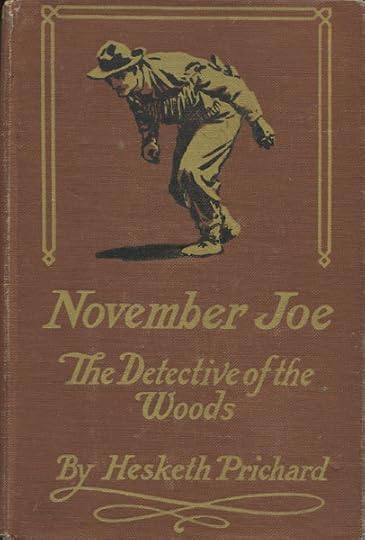

Guest Post | November Joe: Canada's Sherlock Holmes

By GW Thomas

Hesketh PrichardThe Northern was Canada’s one true contribution to genre literature. The majority of Northerns are tales of fur trappers or gold miners: strong men and women pitied against the rough conditions of life in the wilderness. One book amongst these tales of hunting, trapping, and the lives of the animals that dwell in quiet places belongs to another genre as well. The book is November Joe (1913) by Hesketh Prichard. Despite being a Northern of the highest order, it is also a detective novel, or rather, a collection of detective stories.

Hesketh PrichardThe Northern was Canada’s one true contribution to genre literature. The majority of Northerns are tales of fur trappers or gold miners: strong men and women pitied against the rough conditions of life in the wilderness. One book amongst these tales of hunting, trapping, and the lives of the animals that dwell in quiet places belongs to another genre as well. The book is November Joe (1913) by Hesketh Prichard. Despite being a Northern of the highest order, it is also a detective novel, or rather, a collection of detective stories.

Prichard's detective possesses the Sherlockian ability to see what others do not: "...Where a town-bred man would see nothing but a series of blurred footsteps in the morning dew, an ordinary dweller in the woods could learn something from them, but November Joe can often reconstruct the man who made them, sometimes in a manner and with an exactitude that has struck me as little short of marvelous."

The character of November Joe is incredible, but no more incredible than the man who created him. Hesketh Prichard was the son of a British officer who died weeks before his son's birth. Raised in England by his mother, he trained for the Law but became a writer instead. Through his acquaintance with JM Barrie, Prichard and his mother went to work for Cyril Arthur Pearson, the owner of Pearson's Magazine in 1897. Under the pseudonym E and H Heron, the mother-son team wrote a dozen tales of ghostbreaker Flaxman Low. But Hesketh was not limited to horror stories. He wrote books about hunting, sports, and his travels. These caught the attention of President Teddy Roosevelt who called Prichard's Through Trackless Labrador (1911) the best book of the season.

With the coming of World War I, Prichard enlisted as an "eyewitness officer" in charge of war correspondents. His observations at the front led him to lower the number of British casualties from snipers. He developed several techniques to locate German snipers, including inventing the dummy head and improved trench design. He also spent his time and his own money improving British sniping rifles and techniques. For this he was given the Distinguished Service Order in 1917. To say the least, Hesketh Pricard knew guns, shooting, and the wilds of Canada; all part and parcel of the story of November Joe.

With the coming of World War I, Prichard enlisted as an "eyewitness officer" in charge of war correspondents. His observations at the front led him to lower the number of British casualties from snipers. He developed several techniques to locate German snipers, including inventing the dummy head and improved trench design. He also spent his time and his own money improving British sniping rifles and techniques. For this he was given the Distinguished Service Order in 1917. To say the least, Hesketh Pricard knew guns, shooting, and the wilds of Canada; all part and parcel of the story of November Joe.

November Joe begins with our Watson, Mr. James Quaritch, leaving work for three months to go shoot moose. His friend, Sir Andrew McLerrick, recommends November Joe as his guide. Upon arriving in the woods of Quebec where Joe lives, Quaritch is asked to deliver a message to Joe. The Provincial Police offer him fifty dollars if he can find the killer of a dead trapper. The hunting trip off, Quaritch convinces Joe to let him tag along.

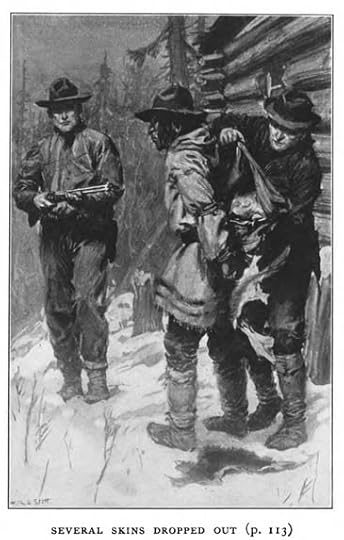

THE CASES OF NOVEMBER JOE

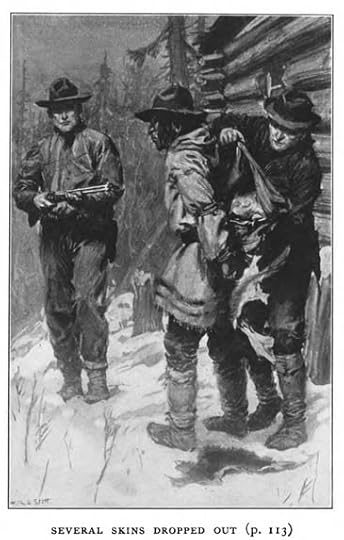

"The Crime at Big Tree Portage" gives Quaritch plenty of opportunities to see November Joe in action. The two men go to the lumber camp at Big Tree Portage where the dead man, Henry Lyon, lies. Joe quickly accesses the few clues, seeing that the killer pulled up in a canoe, called to the man, and then shot him, leaving virtually no evidence. But Joe isn't stymied. He backtracks Lyon to his camp before the murder. Here he finds two beds of spruce boughs and evidence of the identity of a second man. Going to the small town of Amiel, November Joe finds out the background of Lyon's life, the names of all the men away trapping, and quickly narrows his suspect list to one man. He and Quaritch visit the man and quickly get a confession. When they learn of his reasons for the killing, Joe helps him destroy evidence, making it impossible for the police to follow the trail. The fifty dollars is not as important to Joe as his sense of backwoods justice.

"The Seven Lumberjacks" has local tree-fallers being robbed by a gang of thieves. False evidence has them accusing their boss, Mr. Close, of the deed, but Joe's careful examination of the ground tells him that the gang is only one man, and one of the lumberjacks. He sets a trap too tempting for the thief to resist.

"The Seven Lumberjacks" has local tree-fallers being robbed by a gang of thieves. False evidence has them accusing their boss, Mr. Close, of the deed, but Joe's careful examination of the ground tells him that the gang is only one man, and one of the lumberjacks. He sets a trap too tempting for the thief to resist.

"The Black Fox Skin" has a widow, Sally Rone, seeking out Joe because someone is robbing her traps: a ploy to force her to marry or starve. One of the pelts that is taken is a black fox pelt worth eight hundred dollars. Suspicion falls on Val Black, one of Sally's suitors, when he is found with stolen furs and a condemning bullet is found in Sally's cabin. November Joe suspects a frame-up. He sets a trap for the culprit and Sally and Val are free to marry.

"The Murder at the Duck Club" is almost an English cosy with its select club members and enclosed space. Young Ted Galt is accused of murdering Judge Harrison while out shooting geese. The tracks do nothing to clear the fiance of Harrison's daughter, Eileen. Instead of tracks, Joe examines the guns that have been so damning for Galt, as only he uses size 6 shot in his shotgun. Joe gleans a different motive and quickly rounds up the killer, someone else with a grudge against the judge.

"The Case of Miss Virginia Plank" has November and Quaritch looking for a murdered girl. November's careful tracking proves the girl is not dead, but kidnapped. Later, after meeting the kidnappers (a big man who talked and a small one who didn't), November is onto the truth. The tracks of the small man reveal his moccasins are too large. November knows that Virginia Plank was the small man and the kidnapping is a set-up. With a knowledge of civilized girls and a little poking around, he identifies the girl's accomplice, Hank Harper, and finds her at his cabin. Virginia explains why she pulled the stunt, and like in "The Crime at Big Tree Portage," November's sense of justice outweighs his sense of law.

"The Hundred Thousand Dollar Robbery" has Joe following a missing banker named Atterson, who has absconded with $100,000 in securities. Joe finds the man, but realizes that he has been robbed in turn and in fact used by another to commit the crime. He deduces who would have been able to turn Atterson's head and tracks down the woman, getting the money back.

"The Hundred Thousand Dollar Robbery" has Joe following a missing banker named Atterson, who has absconded with $100,000 in securities. Joe finds the man, but realizes that he has been robbed in turn and in fact used by another to commit the crime. He deduces who would have been able to turn Atterson's head and tracks down the woman, getting the money back.

"The Looted Island" has a fox farmer named Stafford robbed of $15,000 in fur. His employee, Aleut Sam, is also missing. Joe agrees to track down the culprits for ten percent of the furs' value. The island is frozen and icy, so there aren't any tracks to follow. Instead, November examines the fox pens and the cabin where the robbers camped out for a few days. This produces some information, like the fact that all the carcasses are from red foxes, not black. Someone has taken the foxes and tried to make it look like they were killed. Before they can act, the three men notice smoke coming from the neighboring island. Here they find Sam who tells a story of being stranded for eleven days. November examines his campfire and knows he is lying. The ashes indicate only a two-day stay, as Sam has no axe with him. Stafford forces the truth out of Sam and the men are off to Jurgenson's fur farm. The Swede can’t deny the evidence November provides and agrees to return the black foxes and two extra for their trouble.

"The Mystery of Fletcher Buckman" is a traditional train murder mystery. Buckman is an oil expert traveling with his wife. He is to make a report that will either increase or decrease certain stocks. The man is found dead, hanging like a suicide. November quickly puts this idea to rest for he finds fingermarks on the man's throat where he was strangled. The report has also been stolen. A man who had been arguing with Buckman, a down-and-out oil worker named Knowles, looks like the killer, but November proves this untrue based on the clues in the murdered man's car. Taking all the evidence and geography in mind, November leads the provincial police to the post office where the killer is about to mail the stolen report. This story breaks one of the classic Ronald Knox's fair-play rules: "The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story...". The culprit is never even named, let alone known to November Joe. The story is more about proving Knowles innocent and tracking the killer.

The remaining chapters, "Linda Petersham," "Kalmacks," "The Men of the Mountains," "The Man in the Black Hat," "The Capture," and "The City or the Woods" tell the final tale of November Joe. (The previous chapters were obviously short stories sold to magazines, and now Prichard is attempting to give the book a final episode to fill it out.) Quaritch is approached by an old family friend, Linda Petersham. She's worried about her father, who has purchased a large hunting concession called the Kalmacks. In fairness, he paid out the local squatters, but someone has sent a death threat if Petersham doesn't pay another $5000. Quaritch brings in November Joe and all four are off to the wilds, surrounded by lurking danger.

The remaining chapters, "Linda Petersham," "Kalmacks," "The Men of the Mountains," "The Man in the Black Hat," "The Capture," and "The City or the Woods" tell the final tale of November Joe. (The previous chapters were obviously short stories sold to magazines, and now Prichard is attempting to give the book a final episode to fill it out.) Quaritch is approached by an old family friend, Linda Petersham. She's worried about her father, who has purchased a large hunting concession called the Kalmacks. In fairness, he paid out the local squatters, but someone has sent a death threat if Petersham doesn't pay another $5000. Quaritch brings in November Joe and all four are off to the wilds, surrounded by lurking danger.

Upon their arrival, Petersham is informed that one of his game wardens, Bill Worke, was shot through the knee while at Senlis Lake. November's tracking about the lake finds a 45.75 caliber cartridge. November has Petersham dump two loads of sand from the lake around the house to improve tracking. This keeps the blackmailers away for a while, but eventually they make their demands that the $5000 dollars be left at Butler's Cairn. The demand comes from a masked man who holds up the other game warden, Ben Puttick, at rifle point. Petersham doesn't want to pay and Joe agrees. He slips out the window and covers Butler's Cairn, but no one shows. This makes him suspicious so he sets up a plan for the following day.

November leaves for Senlis Lake, making sure everyone knows where he is going. Shots are heard and Quaritch runs to the lake to find Joe shot. Together they look at the body of the shooter, a man in a black hat with a beard. Joe has killed him with a shot to the throat. Quaritch carries Joe back to the cabin where he reveals that the mole in their group is Puttick. The dead shooter is identified as Dandy Tomlinson, who with his brother, Muppy (both names worthy of Jack London), devised the plan with Puttick.

Mystery solved, Petersham tries to show his gratitude to November by offering to set him up in business. Linda encourages November to take the offer so that she can marry him. In the end, November Joe refuses, returning to his woods. Prichard leaves just enough of an opening for a sequel if the book should sell well. (As no sequel ever happened, I guess it did not.)

Mystery solved, Petersham tries to show his gratitude to November by offering to set him up in business. Linda encourages November to take the offer so that she can marry him. In the end, November Joe refuses, returning to his woods. Prichard leaves just enough of an opening for a sequel if the book should sell well. (As no sequel ever happened, I guess it did not.)

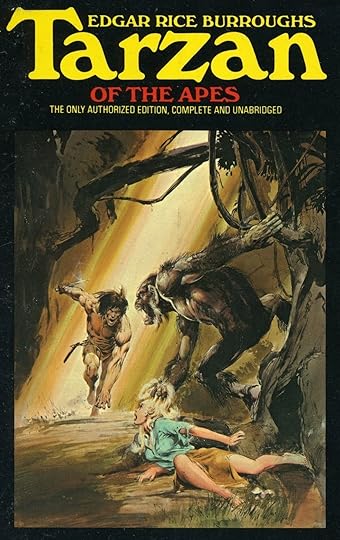

What struck me as interesting about this ending is how, in essence, it is the same as the final pages of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Burroughs would write his most famous novel around the same time, so I'm not suggesting either author had any influence on the other. What I am suggesting is that the theme of both is that the Natural Man refuses to be corrupted or tamed by civilization. Tarzan returns to his jungle, more ape than man. The difference is that Tarzan of the Apes was a huge success followed by twenty-three sequels. The first of those was The Return of Tarzan, in which Tarzan and Jane are united at last. Jane and Tarzan build a ranch and remain in Africa. This is a choice that November Joe refuses to think of for Linda Petersham. He knows she is a creature of civilization and will never be happy living the mean existence of a trapper's wife.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Hesketh PrichardThe Northern was Canada’s one true contribution to genre literature. The majority of Northerns are tales of fur trappers or gold miners: strong men and women pitied against the rough conditions of life in the wilderness. One book amongst these tales of hunting, trapping, and the lives of the animals that dwell in quiet places belongs to another genre as well. The book is November Joe (1913) by Hesketh Prichard. Despite being a Northern of the highest order, it is also a detective novel, or rather, a collection of detective stories.

Hesketh PrichardThe Northern was Canada’s one true contribution to genre literature. The majority of Northerns are tales of fur trappers or gold miners: strong men and women pitied against the rough conditions of life in the wilderness. One book amongst these tales of hunting, trapping, and the lives of the animals that dwell in quiet places belongs to another genre as well. The book is November Joe (1913) by Hesketh Prichard. Despite being a Northern of the highest order, it is also a detective novel, or rather, a collection of detective stories.Prichard's detective possesses the Sherlockian ability to see what others do not: "...Where a town-bred man would see nothing but a series of blurred footsteps in the morning dew, an ordinary dweller in the woods could learn something from them, but November Joe can often reconstruct the man who made them, sometimes in a manner and with an exactitude that has struck me as little short of marvelous."

The character of November Joe is incredible, but no more incredible than the man who created him. Hesketh Prichard was the son of a British officer who died weeks before his son's birth. Raised in England by his mother, he trained for the Law but became a writer instead. Through his acquaintance with JM Barrie, Prichard and his mother went to work for Cyril Arthur Pearson, the owner of Pearson's Magazine in 1897. Under the pseudonym E and H Heron, the mother-son team wrote a dozen tales of ghostbreaker Flaxman Low. But Hesketh was not limited to horror stories. He wrote books about hunting, sports, and his travels. These caught the attention of President Teddy Roosevelt who called Prichard's Through Trackless Labrador (1911) the best book of the season.

With the coming of World War I, Prichard enlisted as an "eyewitness officer" in charge of war correspondents. His observations at the front led him to lower the number of British casualties from snipers. He developed several techniques to locate German snipers, including inventing the dummy head and improved trench design. He also spent his time and his own money improving British sniping rifles and techniques. For this he was given the Distinguished Service Order in 1917. To say the least, Hesketh Pricard knew guns, shooting, and the wilds of Canada; all part and parcel of the story of November Joe.

With the coming of World War I, Prichard enlisted as an "eyewitness officer" in charge of war correspondents. His observations at the front led him to lower the number of British casualties from snipers. He developed several techniques to locate German snipers, including inventing the dummy head and improved trench design. He also spent his time and his own money improving British sniping rifles and techniques. For this he was given the Distinguished Service Order in 1917. To say the least, Hesketh Pricard knew guns, shooting, and the wilds of Canada; all part and parcel of the story of November Joe.November Joe begins with our Watson, Mr. James Quaritch, leaving work for three months to go shoot moose. His friend, Sir Andrew McLerrick, recommends November Joe as his guide. Upon arriving in the woods of Quebec where Joe lives, Quaritch is asked to deliver a message to Joe. The Provincial Police offer him fifty dollars if he can find the killer of a dead trapper. The hunting trip off, Quaritch convinces Joe to let him tag along.

THE CASES OF NOVEMBER JOE

"The Crime at Big Tree Portage" gives Quaritch plenty of opportunities to see November Joe in action. The two men go to the lumber camp at Big Tree Portage where the dead man, Henry Lyon, lies. Joe quickly accesses the few clues, seeing that the killer pulled up in a canoe, called to the man, and then shot him, leaving virtually no evidence. But Joe isn't stymied. He backtracks Lyon to his camp before the murder. Here he finds two beds of spruce boughs and evidence of the identity of a second man. Going to the small town of Amiel, November Joe finds out the background of Lyon's life, the names of all the men away trapping, and quickly narrows his suspect list to one man. He and Quaritch visit the man and quickly get a confession. When they learn of his reasons for the killing, Joe helps him destroy evidence, making it impossible for the police to follow the trail. The fifty dollars is not as important to Joe as his sense of backwoods justice.

"The Seven Lumberjacks" has local tree-fallers being robbed by a gang of thieves. False evidence has them accusing their boss, Mr. Close, of the deed, but Joe's careful examination of the ground tells him that the gang is only one man, and one of the lumberjacks. He sets a trap too tempting for the thief to resist.

"The Seven Lumberjacks" has local tree-fallers being robbed by a gang of thieves. False evidence has them accusing their boss, Mr. Close, of the deed, but Joe's careful examination of the ground tells him that the gang is only one man, and one of the lumberjacks. He sets a trap too tempting for the thief to resist."The Black Fox Skin" has a widow, Sally Rone, seeking out Joe because someone is robbing her traps: a ploy to force her to marry or starve. One of the pelts that is taken is a black fox pelt worth eight hundred dollars. Suspicion falls on Val Black, one of Sally's suitors, when he is found with stolen furs and a condemning bullet is found in Sally's cabin. November Joe suspects a frame-up. He sets a trap for the culprit and Sally and Val are free to marry.

"The Murder at the Duck Club" is almost an English cosy with its select club members and enclosed space. Young Ted Galt is accused of murdering Judge Harrison while out shooting geese. The tracks do nothing to clear the fiance of Harrison's daughter, Eileen. Instead of tracks, Joe examines the guns that have been so damning for Galt, as only he uses size 6 shot in his shotgun. Joe gleans a different motive and quickly rounds up the killer, someone else with a grudge against the judge.

"The Case of Miss Virginia Plank" has November and Quaritch looking for a murdered girl. November's careful tracking proves the girl is not dead, but kidnapped. Later, after meeting the kidnappers (a big man who talked and a small one who didn't), November is onto the truth. The tracks of the small man reveal his moccasins are too large. November knows that Virginia Plank was the small man and the kidnapping is a set-up. With a knowledge of civilized girls and a little poking around, he identifies the girl's accomplice, Hank Harper, and finds her at his cabin. Virginia explains why she pulled the stunt, and like in "The Crime at Big Tree Portage," November's sense of justice outweighs his sense of law.

"The Hundred Thousand Dollar Robbery" has Joe following a missing banker named Atterson, who has absconded with $100,000 in securities. Joe finds the man, but realizes that he has been robbed in turn and in fact used by another to commit the crime. He deduces who would have been able to turn Atterson's head and tracks down the woman, getting the money back.

"The Hundred Thousand Dollar Robbery" has Joe following a missing banker named Atterson, who has absconded with $100,000 in securities. Joe finds the man, but realizes that he has been robbed in turn and in fact used by another to commit the crime. He deduces who would have been able to turn Atterson's head and tracks down the woman, getting the money back."The Looted Island" has a fox farmer named Stafford robbed of $15,000 in fur. His employee, Aleut Sam, is also missing. Joe agrees to track down the culprits for ten percent of the furs' value. The island is frozen and icy, so there aren't any tracks to follow. Instead, November examines the fox pens and the cabin where the robbers camped out for a few days. This produces some information, like the fact that all the carcasses are from red foxes, not black. Someone has taken the foxes and tried to make it look like they were killed. Before they can act, the three men notice smoke coming from the neighboring island. Here they find Sam who tells a story of being stranded for eleven days. November examines his campfire and knows he is lying. The ashes indicate only a two-day stay, as Sam has no axe with him. Stafford forces the truth out of Sam and the men are off to Jurgenson's fur farm. The Swede can’t deny the evidence November provides and agrees to return the black foxes and two extra for their trouble.

"The Mystery of Fletcher Buckman" is a traditional train murder mystery. Buckman is an oil expert traveling with his wife. He is to make a report that will either increase or decrease certain stocks. The man is found dead, hanging like a suicide. November quickly puts this idea to rest for he finds fingermarks on the man's throat where he was strangled. The report has also been stolen. A man who had been arguing with Buckman, a down-and-out oil worker named Knowles, looks like the killer, but November proves this untrue based on the clues in the murdered man's car. Taking all the evidence and geography in mind, November leads the provincial police to the post office where the killer is about to mail the stolen report. This story breaks one of the classic Ronald Knox's fair-play rules: "The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story...". The culprit is never even named, let alone known to November Joe. The story is more about proving Knowles innocent and tracking the killer.

The remaining chapters, "Linda Petersham," "Kalmacks," "The Men of the Mountains," "The Man in the Black Hat," "The Capture," and "The City or the Woods" tell the final tale of November Joe. (The previous chapters were obviously short stories sold to magazines, and now Prichard is attempting to give the book a final episode to fill it out.) Quaritch is approached by an old family friend, Linda Petersham. She's worried about her father, who has purchased a large hunting concession called the Kalmacks. In fairness, he paid out the local squatters, but someone has sent a death threat if Petersham doesn't pay another $5000. Quaritch brings in November Joe and all four are off to the wilds, surrounded by lurking danger.

The remaining chapters, "Linda Petersham," "Kalmacks," "The Men of the Mountains," "The Man in the Black Hat," "The Capture," and "The City or the Woods" tell the final tale of November Joe. (The previous chapters were obviously short stories sold to magazines, and now Prichard is attempting to give the book a final episode to fill it out.) Quaritch is approached by an old family friend, Linda Petersham. She's worried about her father, who has purchased a large hunting concession called the Kalmacks. In fairness, he paid out the local squatters, but someone has sent a death threat if Petersham doesn't pay another $5000. Quaritch brings in November Joe and all four are off to the wilds, surrounded by lurking danger.Upon their arrival, Petersham is informed that one of his game wardens, Bill Worke, was shot through the knee while at Senlis Lake. November's tracking about the lake finds a 45.75 caliber cartridge. November has Petersham dump two loads of sand from the lake around the house to improve tracking. This keeps the blackmailers away for a while, but eventually they make their demands that the $5000 dollars be left at Butler's Cairn. The demand comes from a masked man who holds up the other game warden, Ben Puttick, at rifle point. Petersham doesn't want to pay and Joe agrees. He slips out the window and covers Butler's Cairn, but no one shows. This makes him suspicious so he sets up a plan for the following day.

November leaves for Senlis Lake, making sure everyone knows where he is going. Shots are heard and Quaritch runs to the lake to find Joe shot. Together they look at the body of the shooter, a man in a black hat with a beard. Joe has killed him with a shot to the throat. Quaritch carries Joe back to the cabin where he reveals that the mole in their group is Puttick. The dead shooter is identified as Dandy Tomlinson, who with his brother, Muppy (both names worthy of Jack London), devised the plan with Puttick.

Mystery solved, Petersham tries to show his gratitude to November by offering to set him up in business. Linda encourages November to take the offer so that she can marry him. In the end, November Joe refuses, returning to his woods. Prichard leaves just enough of an opening for a sequel if the book should sell well. (As no sequel ever happened, I guess it did not.)

Mystery solved, Petersham tries to show his gratitude to November by offering to set him up in business. Linda encourages November to take the offer so that she can marry him. In the end, November Joe refuses, returning to his woods. Prichard leaves just enough of an opening for a sequel if the book should sell well. (As no sequel ever happened, I guess it did not.)What struck me as interesting about this ending is how, in essence, it is the same as the final pages of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Burroughs would write his most famous novel around the same time, so I'm not suggesting either author had any influence on the other. What I am suggesting is that the theme of both is that the Natural Man refuses to be corrupted or tamed by civilization. Tarzan returns to his jungle, more ape than man. The difference is that Tarzan of the Apes was a huge success followed by twenty-three sequels. The first of those was The Return of Tarzan, in which Tarzan and Jane are united at last. Jane and Tarzan build a ranch and remain in Africa. This is a choice that November Joe refuses to think of for Linda Petersham. He knows she is a creature of civilization and will never be happy living the mean existence of a trapper's wife.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on November 03, 2017 04:00

November 2, 2017

Planetary Union Network | Bruce Broughton and "Majority Rule"

On the latest Planetary Union Network, we had the pleasure of interviewing composer Bruce Broughton, who wrote not only the Orville theme, but tons of classic movie scores from Ice Pirates and Monster Squad to Silverado and Tombstone. He was a great guy to talk to and I love the passion with which he answered my question about the many scores he wrote for Disney theme parks. The best part though is when he talked about the difference between scoring Westerns and Science Fiction and then demonstrated on the piano! The episode is worth listening to just for that.

But if you're into The Orville and wanna hear us talk about "Majority Rule," my favorite episode since "About a Girl," then there's that, too.

Published on November 02, 2017 04:00

November 1, 2017

N3rd World | More Blade Runner Than Blade Runner

On the latest N3rd World, we dig into both Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049 before discussing the final trailer for Last Jedi. The Blade Runner discussions are spoiler-filled, but I think we did a good job articulating why we all love both movies. And I also think we get a pretty good handle on deciphering what expectations the Last Jedi trailer wants us to have for the movie.

Published on November 01, 2017 04:00

October 31, 2017

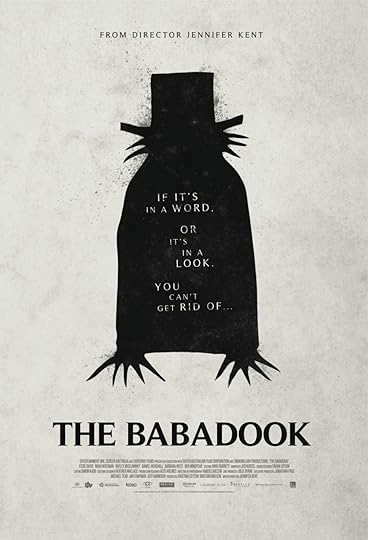

The Babadook (2014)

Who's In It: Essie Davis (the Matrix sequels, Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries, The White Princess) and Noah Wiseman (just this for now).

What It's About: A widow's (Davis) struggle to raise her special needs son (Wiseman) becomes harder when a character from a spooky children's book comes to life in their home.

How It Is: The monster looks great and there are cool, scary moments, but the beauty of the film is that it creates a new monster to represent a modern fear. I know single parents who are raising kids with special needs and/or challenging behaviors. I see just the tiniest part of their struggle and can't imagine how they do what they do. The Babadook doesn't make the "how" part any clearer, but it sure does highlight and underline the impossibility of the job and how much support is desperately needed. Throw a big helping of grief about a deceased spouse on top of that and it's even more powerful. I'll be watching this again and sharing it with others.

Rating: 4 out of 5 monsters under the bed.

Published on October 31, 2017 04:00

October 30, 2017

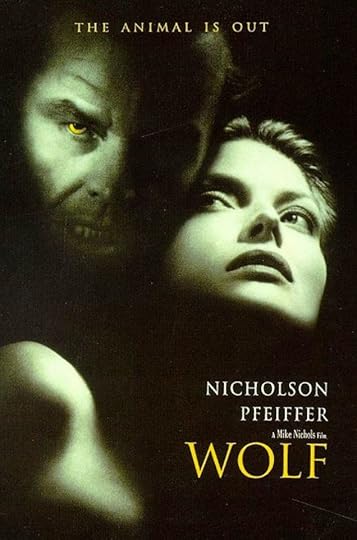

Wolf (1994)

Who's In It: Jack Nicholson (The Raven, The Witches of Eastwick, Batman), Michelle Pfeiffer (The Witches of Eastwick, Batman Returns, Dark Shadows), James Spader (Pretty in Pink, Stargate, Shorts), Kate Nelligan (the Frank Langella Dracula), Richard Jenkins (The Witches of Eastwick, Let Me In, The Cabin in the Woods, Bone Tomahawk), Christopher Plummer (Vampire in Venice, Dracula 2000), David Hyde Pierce (Addams Family Values, Hellboy, The Amazing Screw-On Head), and Ron Rifkin (Alias).

What It's About: An aging, complacent man rediscovers life and purpose when he's bitten by a werewolf.

How It Is: I almost didn't write "werewolf" in the description there, because Wolf makes a point of not using that word. But it's absolutely a werewolf movie and in my (apparently minority) opinion, a really good one.

Wolf came out two years after Francis Ford Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula and five months before Kenneth Branagh's Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, so in my mind it completed the trinity of early '90s monster movie remakes. Imagine a House of Dracula with Gary Oldman, Robert De Niro, and Jack Nicholson. I certainly did. But because Universal's Wolf Man wasn't based on a particular novel, there was no source material for Wolf to mess up. And that made it my favorite of the three.

My love of The Wolf Man is based in the tragic relatability of its main character, so that's what I'm always looking for in werewolf movies. Wolf has that, tied into a revenge fantasy about equally relatable problems like losing your job or finding out that people you're close to are unfaithful.

Some of the set up for the revenge fantasy is obvious to the point of being trite, but the cast is so good that I never care. Even hackneyed elements like the ruthless businessman who's acquiring Nicholson's company is made fascinating because Plummer plays him with humor and a wicked twinkle in his eye. And if you're going to have a traitorous best friend, who better to play him than James Spader? And I haven't even mentioned Pfeiffer yet, who's simultaneously butt-kicking and heart-breaking as Plummer's damaged, but resilient daughter.

Rating: 4 out of 5 Old Man Logans.

Published on October 30, 2017 04:00

October 29, 2017

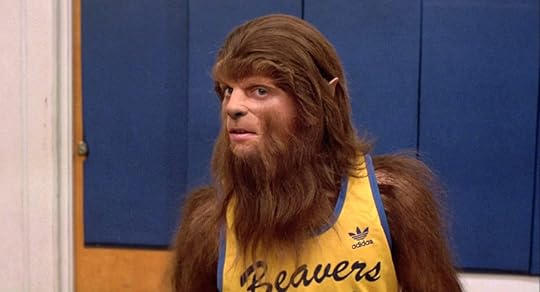

Teen Wolf (1985)

Who's In It: Michael J Fox (Family Ties, Back to the Future), James Hampton (Hanger 18, Sling Blade), Jerry Levine (Casual Sex?), and Jay Tarses (wrote The Great Muppet Caper and The Muppets Take Manhattan).

What It's About: An average teenager (Fox) struggles with his identity when he discovers that he's a werewolf.

How It Is: I haven't seen this in years and it wasn't originally on my list for this year either. But after the I Hate/Love Remakes: Wolf Man episode came out, David and I got to talking about werewolf movies and this is one that he's been aware of for a long time, but never seen.

I remembered liking it back in the day, but comparing it unfavorably to Back to the Future which sneaked out ahead of it in 1985. My memory was that I really liked Fox in it (of course), that I also liked his dad (Hampton), and that I loved the twist that the werewolf was an object of popular admiration and not fear. But I also remembered being super irritated by best friend Stiles (Levine) and a little confused about the film's ultimate message.

Seeing it again, I still love Fox and Hampton. I'm not as annoyed by Stiles as I used to be, but that's probably because that kind of character isn't as ubiquitous these days as he was in the '80s. I still love the twist of the werewolf's popularity, too. That first public transformation during the basketball game is so great, because the way that Scott (Fox) handles it and then the crowd's reaction is completely unexpected.

With age, though, I think I have a better handle now on what the werewolf represents. As a high school student myself when Teen Wolf came out, I thought it was awesome that everyone accepted the Wolf in all his oddity. This was a big theme for me growing up and it's the reason that I feel such deep connections to characters like Chewbacca, Worf, and the Frankenstein Monster. Teen Wolf was another example of that, so I didn't love it when characters like Boof and Lewis made Scott feel bad about embracing his uniqueness. And I didn't love it even more when Scott basically rejects the Wolf at the end. Scott had previously lamented his "average"-ness, which I interpreted as "normality" and "fitting in." I didn't get why he would go back to that, but I was bringing my own hang-ups to the story.

I still feel strongly about resisting conformity, but those feelings are deeply embedded at this point and don't dominate my thinking. Because I don't actively wrestle with them these days, I was able to watch Teen Wolf this time from a different point of view that made me appreciate its message more. Instead of being about general non-conformity, this time the Wolf was about being "special." That is, it's not so much about being "different" from everyone else as it is about being "better." I think that's pretty clear in Scott's language. He doesn't want to be an "okay" basketball player, he wants to be an exceptional one.

With that in mind, I like the movie's message much more. There's a price to pay for being The Best. Some, like Lewis and Mick, fear the exceptional. Others, like Stiles and Pamela, want to exploit it. It's Boof who has the perspective that Scott ultimately adopts for himself. She already likes him as he is. He doesn't need to be exceptional or the best at something to have value. That's an important and underheard message and it makes me really like the movie.

As a grown-up, I hope that Scott one day adopts his dad's perspective, which is to embrace his gifts responsibly. Teenagers aren't exactly known for balance though, so until Scott's able to do that, I'm thrilled that he's learned to like himself in the meantime.

Rating: 4 out of 5 shaggy shooters.

Published on October 29, 2017 04:00

October 28, 2017

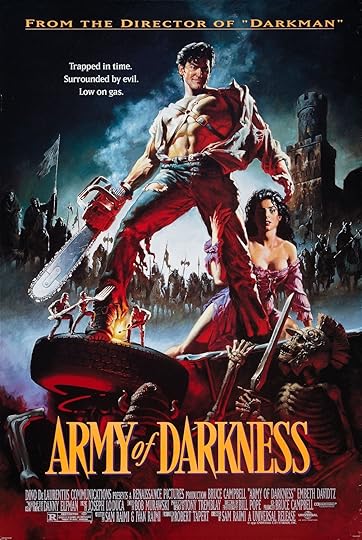

Army of Darkness (1992)

Who's In It: Bruce Campbell (Escape from LA, Xena: Warrior Princess, Bubba Ho-Tep), Embeth Davidtz (Schindler's List, Thir13en Ghosts, The Amazing Spider-Man), and Ted Raimi (everything, and yet not enough stuff).

What It's About: After being sent to the fourteenth century at the end of Evil Dead 2, Ash (Campbell) agrees to fight demons in exchange for a way back to his own time.

How It Is: Differentiates itself from the previous two movies by toning down the horror and ramping the comedy way, way up into full camp and slapstick. Ash is no longer supposed to be relateable; he's now a cartoon and I love it that way. Army of Darkness is an on-the-cheap fantasy movie (with horror elements) from the guys who would go on to bring us Hercules and Xena. And Bruce Campbell is at the absolute top of his game. It's super fun and super funny.

Rating: 4 out 5 boom sticks.

Published on October 28, 2017 04:00

October 27, 2017

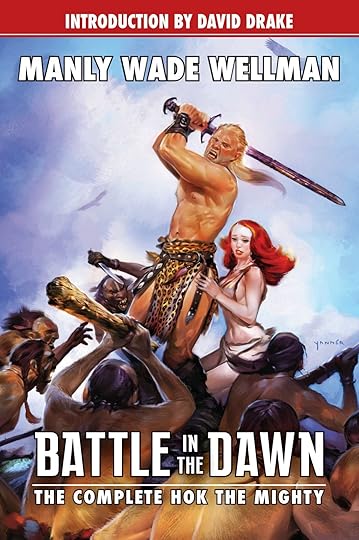

Guest Post | Manly Wade Wellman's Hok the Mighty

By GW Thomas

Prehistoric fiction began almost as soon as Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859. A lot of this early fiction seems silly in light of our current theories and archaeological discoveries, but some remains readable. HG Wells is one of these writers. He wasn't the first to pen a romance that included neanderthals, but he was certainly one of the most influential.

Prehistoric fiction began almost as soon as Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859. A lot of this early fiction seems silly in light of our current theories and archaeological discoveries, but some remains readable. HG Wells is one of these writers. He wasn't the first to pen a romance that included neanderthals, but he was certainly one of the most influential.

Wells' first try was called "A Story of the Stone Age" (1897). It doesn't feature any neanderthals, but is a tale of a rivalry between Uya and Ugh-lomi for the girl Eudena. This story was followed by the more important (if much shorter) "The Grisly Folk" (The Storyteller, April 1921). It is this one that I believe more likely inspired the pulp Stone Age tales such as Robert E Howard’s first sale, “Spear and Fang” and Manly Wade Wellman's Hok the Mighty series. Unlike "A Story of the Stone Age," "The Grisly Folk" is not expanded out in a full narrative, but reads more like an outline for a series of stories (an outline that Wellman gladly fills in). Wells postulates a small band of human hunters pressed north by competition and how they would survive against the grisly folk. He also tells how the neanderthals would become rarer and were the basis of the troll and ogre stories of childhood. Many of the elements in Wellman's first few Hok tales come right out of Wells's sketch. As with so much pulp SF, Wells is the wellspring.

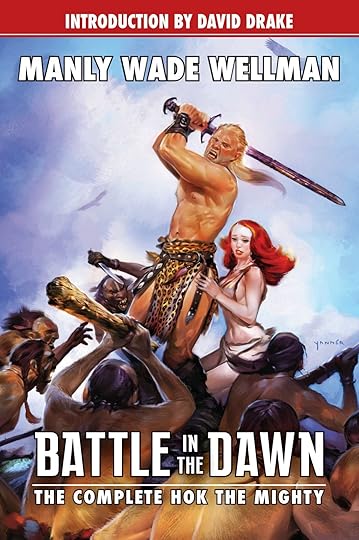

Battle in the Dawn: The Complete Hok the Mighty from Paizo Press collects all of the Hok saga nicely. I love Manly Wade Wellman's Silver John and Kardios stories, as well as the horror tales he did for Weird Tales. I am also a huge fan of Edgar Rice Burroughs, so this book seemed a natural. Wellman attempts something different than the fantastic Stone Age inspired by Burroughs, trying to remain scientifically plausible and avoiding dinosaurs (at first anyway). The Hok tales don't really remind me of Pellucidar so much as another book written many years later: Jim Kjelgaard's Fire Hunter (1951) with a realistic (for the time) portrayal of primitive man. The conflict is humans versus neanderthals, and considering recent genetic evidence, Wellman's tale of war could be fairly accurate. I suppose I should have become a Jean Auel fan, but Wellman's style of adventure appeals more to me. (That, and he didn't write 600-pagers.)

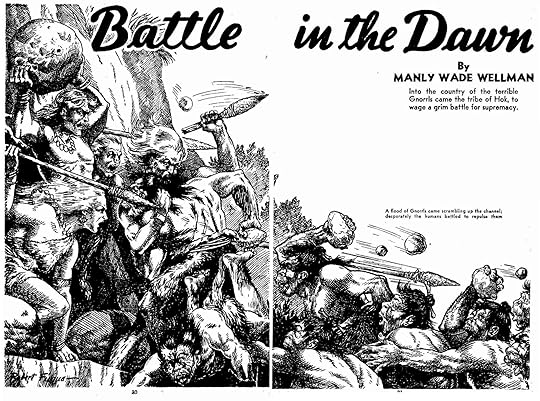

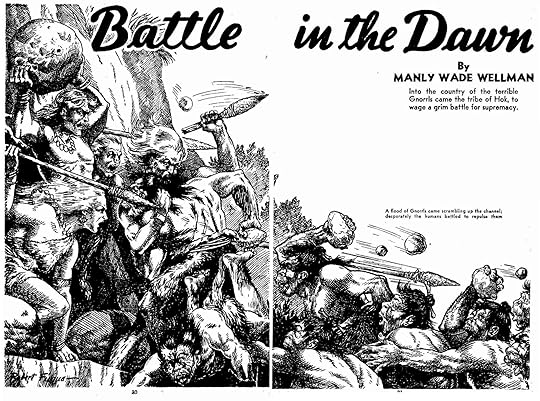

The first Hok story is "Battle in the Dawn" (Amazing Stories, January 1939). The plot is pretty simple. Hok and his band come to a land rich in game, but encounter the local neanderthals (known as Gnorrls). After stealing one of their winter homes, Hok swells their ranks by venturing south and finding a bride. He also saves her brother who has been captured by the Gnorrls so they can steal the human secret of making and using javelins. In the end, the small human band must face an army of a thousand neanderthals, which they defeat at great cost. The story is savage, unforgiving, and realistically brutal. Only the wooing of Oloana reminded me a little of ERB, and that in a very truncated form. The romance element also reminded me of Howard Browne's "Warrior of the Dawn" (Amazing Stories, December 1942). Did Wellman as well as Burroughs inspire Browne?

The first Hok story is "Battle in the Dawn" (Amazing Stories, January 1939). The plot is pretty simple. Hok and his band come to a land rich in game, but encounter the local neanderthals (known as Gnorrls). After stealing one of their winter homes, Hok swells their ranks by venturing south and finding a bride. He also saves her brother who has been captured by the Gnorrls so they can steal the human secret of making and using javelins. In the end, the small human band must face an army of a thousand neanderthals, which they defeat at great cost. The story is savage, unforgiving, and realistically brutal. Only the wooing of Oloana reminded me a little of ERB, and that in a very truncated form. The romance element also reminded me of Howard Browne's "Warrior of the Dawn" (Amazing Stories, December 1942). Did Wellman as well as Burroughs inspire Browne?

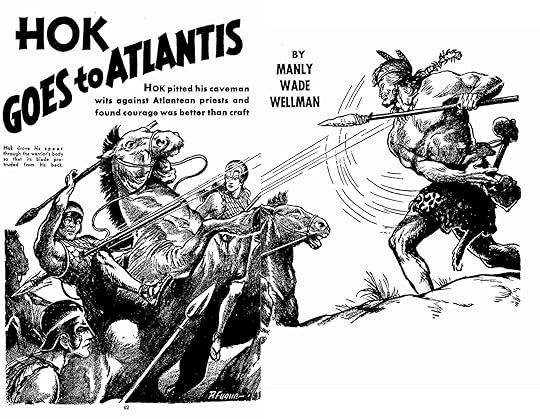

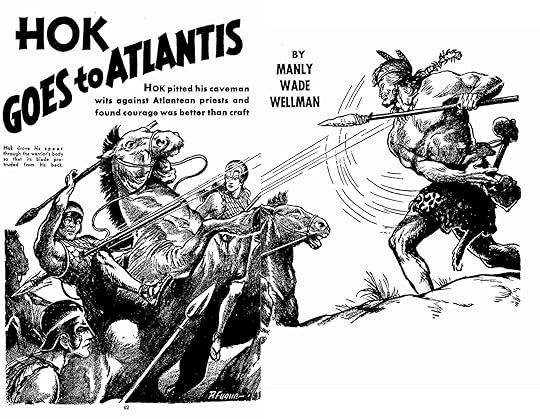

Wellman continued his series with "Hok Goes to Atlantis" (Amazing Stories, December 1939) where the caveman sees many wonders. He also runs afoul of Cos, the perverse king, and has the beautiful Maie fall in love with him. But Hok doesn't abandon Oloana for the queen. As with all love triangles, this is bad news for somebody: Maie. She dies in a bloody battle; a warrior's death for a warrior queen. Of course, it all ends with Tlantis sinking into the ocean and the legend starting. Wellman would use the other end of things with his Kardios series; he being the last survivor of the disaster (which through implication, he was also responsible for on some level). Also, I see how the Tlaneans may have inspired Howard Browne's civilized characters in Warrior of the Dawn, which appeared in Amazing three years later. Finished with the adventure, but richer in knowledge, Hok turns his back on such modern ideas as riding horses, using gunpowder, bronze weaponry, and feudal society. He prefers his simple caveman ways. He does keep a club with a gigantic diamond head, though.

What drew me to this story in particular was the suggestion that the Hok stories were sword-and-sorcery. This tale is probably the closest with a bronze-age society in it, but I would disagree with anyone who calls it sword-and-sorcery. First off, there is no real magic. The Tlanteans have gunpowder, which destroys them along with a volcano. The god they worship is Ghirann the Many-Legged, a giant octopus that Hok kills in a good fight scene. This kraken battle would be co-opted into other sword-and-sorcery tales such as John Jakes' Hell-Arms in the Brak series (and numerous Marvel Conan and Kull comics), though Hok's octopus is by no means the first in adventure/fantasy fiction.

The Hok series - and this particular story - is the outsider-comes-to-a-lost civilization story that started likely with HR Haggard (Allan Quatermain in particular) and then got recycled through Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan. Tarzan did go to Opar (at least three times) as well as a city of gold, a city of ant men, a city of Romans, and another of Aztecs. The Korak comics from DC were also of this ilk, with Korak visiting a different lost city each issue. One was even the underwater remains of Atlantis. The noble outsider almost always starts a rebellion that ends with his friends taking over. Hok was no different except that only he survived the whole mess.

The Hok series - and this particular story - is the outsider-comes-to-a-lost civilization story that started likely with HR Haggard (Allan Quatermain in particular) and then got recycled through Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan. Tarzan did go to Opar (at least three times) as well as a city of gold, a city of ant men, a city of Romans, and another of Aztecs. The Korak comics from DC were also of this ilk, with Korak visiting a different lost city each issue. One was even the underwater remains of Atlantis. The noble outsider almost always starts a rebellion that ends with his friends taking over. Hok was no different except that only he survived the whole mess.

The third installment of Hok the Mighty may be my favorite: "Hok Draws The Bow" (Amazing Stories, May 1940). The plot involves the coming of Romm, an evil-doer in the tradition of Hoojah the Slay-One from Edgar Rice Burroughs' Pellucidar series. Like Hoojah, Romm can speak the language of Hok's enemies and sets himself up as a god of the Gnorrls. He has invented the spear-thrower and also understands military strategy. He takes on Hok in a spear-throwing contest and makes it obvious he wants Hok's wife, Oloana. The Gnorrls kill many of Hok's people and drive the survivors away. In desperation, Hok takes his bow and goes after Romm with only his wife beside him. The ending is exciting and pure pulp.

The invention of the bow is part of Jim Kjelgaard's Fire Hunter too. Both stories try to imagine how new weapons and tools are invented. The invention of the bow predates history, so anybody could be right. Arrowheads from 64,000 years ago have been discovered, so Wellman is certainly well within the right range. If neanderthals died out about 30,000 years ago, that would set these stories just before then, because I don't see the Gnorrls being around for much longer in the Hok sequels.

A little extra with this issue of Amazing was Manly Wade Wellman's bio. The Paizo book includes it as well. What makes this so special is that it appeared before the Silver John stories and is the Wellman who was largely known as an SF writer.

A little extra with this issue of Amazing was Manly Wade Wellman's bio. The Paizo book includes it as well. What makes this so special is that it appeared before the Silver John stories and is the Wellman who was largely known as an SF writer.

A shorter and less impressive tale, "Hok and the Gift of Heaven" (Amazing Stories, March 1941) is still a pretty good read. Hok and his tribesmen are in the middle of a battle with the fisher folk when a meteorite falls on the battlefield. Hok is knocked unconscious and wakes to discover molten metal from the space rock. He uses this to create the first sword, which he names Widow-Maker. After the battle, Djoma and his fisher folk take Oloana and Ptao, Hok's wife and son. Hok follows the band back to the ocean and their village, which is built on stilts out in the water. Hok must face sharks and fight a battle against great odds that ends with him and his loved ones about to be sacrificed. Only a sudden surprise for the sword-wielding Djoma saves them. In the end, Hok gives up his sword and goes back to stone-age weapons. Wellman does a nice job of pitting Hok's Shining One (the Sun) against Djoma's sea-god in their arguments, perhaps the first theological disagreement of prehistory?

The final entry in the Hok saga is the longest, "Hok Visits the Land of Legend." Unlike the earlier installments, this one appeared not in Amazing Stories, but in Fantastic Adventures, April 1942. In this last tale, Hok is bored with the challenges of a hunter and decides to go after a mammoth on his own. He builds a giant bow and shoots a giant arrow into Gragru's chest, but the mammoth does not die. Hok follows his prey to a secret valley where the mammoths go to die. Here he is attacked by pterodactyls (at last! dinosaurs!) and fights and kills one in a fight reminiscent of Tarzan's visit to Pellucidar in 1929.

Then he discovers what he calls an elephant-pig (Dinoceras ingens) or Rmanth. The beast is devouring his dead mammoth. Hok shoots two arrows into the beast, but must flee into the trees. There he is saved by a voice from inside the tree. He enters a hole to find the tree hollow and inhabited by a man-like creature of slender build with prehensile feet. His name is Soko. He takes Hok to the village in the trees. (Jules Verne and Edgar Rice Burroughs may have inspired this, but Wellman's own upbringing in Africa is more likely.) The village is ruled by a tyrant named Krol who keeps the people under sway by allowing the pterodactyls (or Stymphs) to rule the tops of the trees, and the Rmanth to hold the ground. Hok fights the beasts and defeats the tyrant, leading to the legends of Hercules.

What struck me most about this tale was, first off, how far Wellman wandered from Wells' original, inspiring "The Grisly Folk," and how he made the series his own. Also, the basic plot set-up of this story is a dry-run for his classic John the Balladeer tale "O, Ugly Bird!" (F&SF, December 1951) in which a sorcerer uses a flying familiar to terrorize a rural community. Wellman liked stories in which a wandering hero (be he John or Kardios or Hok) comes to a troubled place and prevails. It is also a dry-run for The Last Mammoth (1953), a juvenile adventure novel about a friend of Davy Crockett's who goes to a far Indian village to kill a mammoth that is terrorizing them.

What struck me most about this tale was, first off, how far Wellman wandered from Wells' original, inspiring "The Grisly Folk," and how he made the series his own. Also, the basic plot set-up of this story is a dry-run for his classic John the Balladeer tale "O, Ugly Bird!" (F&SF, December 1951) in which a sorcerer uses a flying familiar to terrorize a rural community. Wellman liked stories in which a wandering hero (be he John or Kardios or Hok) comes to a troubled place and prevails. It is also a dry-run for The Last Mammoth (1953), a juvenile adventure novel about a friend of Davy Crockett's who goes to a far Indian village to kill a mammoth that is terrorizing them.

Thus ends the Hok series, with Hok keeping the hidden valley a secret; returning to his people to live out his days in more fantastic adventures that would come down to us as the tales of heroes from Hercules to Beowulf.

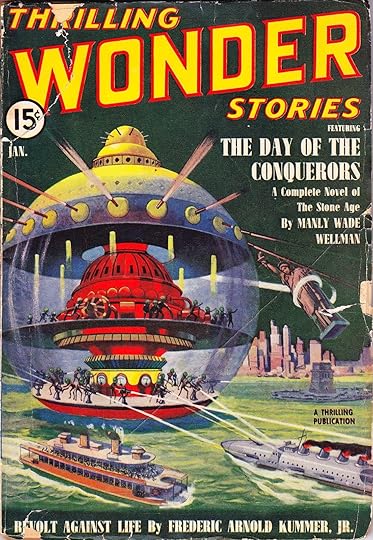

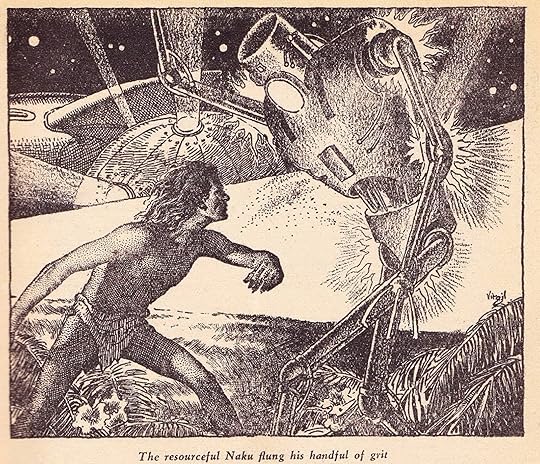

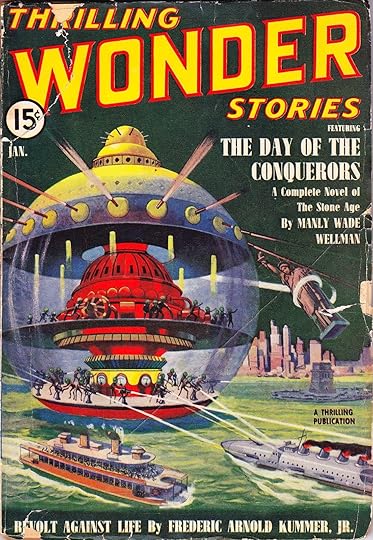

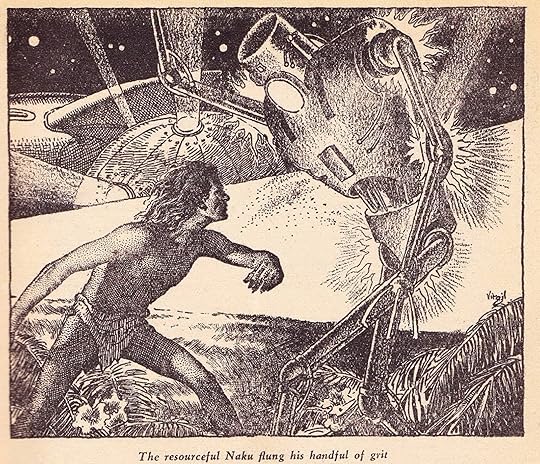

There is one other story that lies close to the Hok series, "The Day of the Conquerers" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, January 1940), appearing after the first two Hok stories. In this science fiction tale, Martians armed with death rays and robots come to Earth to take over the planet. They are faced with an able opponent in Naku (or Lone Hunt), one of the Flint People. Since he is armed with a bow, the story must take place chronologically after Hok's life, for Hok invented the weapon and he makes no reference to alien invaders. So, Naku is one of Hok's descendants and a worthy warrior and cunning fighter.

The Paizo volume includes this story along with a one-page fragment of an unfinished Hok story and an unpublished tale called "The Love of Oloana." Most of this story was incorporated into "Battle in the Dawn." The introduction by David Drake adds a nice explanation of Wellman's youth in Africa. All-in-all, Battle in the Dawn: The Complete Hok the Mighty is a Wellman or pulp fan's dream and a completist's treasure.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Prehistoric fiction began almost as soon as Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859. A lot of this early fiction seems silly in light of our current theories and archaeological discoveries, but some remains readable. HG Wells is one of these writers. He wasn't the first to pen a romance that included neanderthals, but he was certainly one of the most influential.

Prehistoric fiction began almost as soon as Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859. A lot of this early fiction seems silly in light of our current theories and archaeological discoveries, but some remains readable. HG Wells is one of these writers. He wasn't the first to pen a romance that included neanderthals, but he was certainly one of the most influential.Wells' first try was called "A Story of the Stone Age" (1897). It doesn't feature any neanderthals, but is a tale of a rivalry between Uya and Ugh-lomi for the girl Eudena. This story was followed by the more important (if much shorter) "The Grisly Folk" (The Storyteller, April 1921). It is this one that I believe more likely inspired the pulp Stone Age tales such as Robert E Howard’s first sale, “Spear and Fang” and Manly Wade Wellman's Hok the Mighty series. Unlike "A Story of the Stone Age," "The Grisly Folk" is not expanded out in a full narrative, but reads more like an outline for a series of stories (an outline that Wellman gladly fills in). Wells postulates a small band of human hunters pressed north by competition and how they would survive against the grisly folk. He also tells how the neanderthals would become rarer and were the basis of the troll and ogre stories of childhood. Many of the elements in Wellman's first few Hok tales come right out of Wells's sketch. As with so much pulp SF, Wells is the wellspring.

Battle in the Dawn: The Complete Hok the Mighty from Paizo Press collects all of the Hok saga nicely. I love Manly Wade Wellman's Silver John and Kardios stories, as well as the horror tales he did for Weird Tales. I am also a huge fan of Edgar Rice Burroughs, so this book seemed a natural. Wellman attempts something different than the fantastic Stone Age inspired by Burroughs, trying to remain scientifically plausible and avoiding dinosaurs (at first anyway). The Hok tales don't really remind me of Pellucidar so much as another book written many years later: Jim Kjelgaard's Fire Hunter (1951) with a realistic (for the time) portrayal of primitive man. The conflict is humans versus neanderthals, and considering recent genetic evidence, Wellman's tale of war could be fairly accurate. I suppose I should have become a Jean Auel fan, but Wellman's style of adventure appeals more to me. (That, and he didn't write 600-pagers.)

The first Hok story is "Battle in the Dawn" (Amazing Stories, January 1939). The plot is pretty simple. Hok and his band come to a land rich in game, but encounter the local neanderthals (known as Gnorrls). After stealing one of their winter homes, Hok swells their ranks by venturing south and finding a bride. He also saves her brother who has been captured by the Gnorrls so they can steal the human secret of making and using javelins. In the end, the small human band must face an army of a thousand neanderthals, which they defeat at great cost. The story is savage, unforgiving, and realistically brutal. Only the wooing of Oloana reminded me a little of ERB, and that in a very truncated form. The romance element also reminded me of Howard Browne's "Warrior of the Dawn" (Amazing Stories, December 1942). Did Wellman as well as Burroughs inspire Browne?

The first Hok story is "Battle in the Dawn" (Amazing Stories, January 1939). The plot is pretty simple. Hok and his band come to a land rich in game, but encounter the local neanderthals (known as Gnorrls). After stealing one of their winter homes, Hok swells their ranks by venturing south and finding a bride. He also saves her brother who has been captured by the Gnorrls so they can steal the human secret of making and using javelins. In the end, the small human band must face an army of a thousand neanderthals, which they defeat at great cost. The story is savage, unforgiving, and realistically brutal. Only the wooing of Oloana reminded me a little of ERB, and that in a very truncated form. The romance element also reminded me of Howard Browne's "Warrior of the Dawn" (Amazing Stories, December 1942). Did Wellman as well as Burroughs inspire Browne?Wellman continued his series with "Hok Goes to Atlantis" (Amazing Stories, December 1939) where the caveman sees many wonders. He also runs afoul of Cos, the perverse king, and has the beautiful Maie fall in love with him. But Hok doesn't abandon Oloana for the queen. As with all love triangles, this is bad news for somebody: Maie. She dies in a bloody battle; a warrior's death for a warrior queen. Of course, it all ends with Tlantis sinking into the ocean and the legend starting. Wellman would use the other end of things with his Kardios series; he being the last survivor of the disaster (which through implication, he was also responsible for on some level). Also, I see how the Tlaneans may have inspired Howard Browne's civilized characters in Warrior of the Dawn, which appeared in Amazing three years later. Finished with the adventure, but richer in knowledge, Hok turns his back on such modern ideas as riding horses, using gunpowder, bronze weaponry, and feudal society. He prefers his simple caveman ways. He does keep a club with a gigantic diamond head, though.

What drew me to this story in particular was the suggestion that the Hok stories were sword-and-sorcery. This tale is probably the closest with a bronze-age society in it, but I would disagree with anyone who calls it sword-and-sorcery. First off, there is no real magic. The Tlanteans have gunpowder, which destroys them along with a volcano. The god they worship is Ghirann the Many-Legged, a giant octopus that Hok kills in a good fight scene. This kraken battle would be co-opted into other sword-and-sorcery tales such as John Jakes' Hell-Arms in the Brak series (and numerous Marvel Conan and Kull comics), though Hok's octopus is by no means the first in adventure/fantasy fiction.

The Hok series - and this particular story - is the outsider-comes-to-a-lost civilization story that started likely with HR Haggard (Allan Quatermain in particular) and then got recycled through Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan. Tarzan did go to Opar (at least three times) as well as a city of gold, a city of ant men, a city of Romans, and another of Aztecs. The Korak comics from DC were also of this ilk, with Korak visiting a different lost city each issue. One was even the underwater remains of Atlantis. The noble outsider almost always starts a rebellion that ends with his friends taking over. Hok was no different except that only he survived the whole mess.

The Hok series - and this particular story - is the outsider-comes-to-a-lost civilization story that started likely with HR Haggard (Allan Quatermain in particular) and then got recycled through Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan. Tarzan did go to Opar (at least three times) as well as a city of gold, a city of ant men, a city of Romans, and another of Aztecs. The Korak comics from DC were also of this ilk, with Korak visiting a different lost city each issue. One was even the underwater remains of Atlantis. The noble outsider almost always starts a rebellion that ends with his friends taking over. Hok was no different except that only he survived the whole mess.The third installment of Hok the Mighty may be my favorite: "Hok Draws The Bow" (Amazing Stories, May 1940). The plot involves the coming of Romm, an evil-doer in the tradition of Hoojah the Slay-One from Edgar Rice Burroughs' Pellucidar series. Like Hoojah, Romm can speak the language of Hok's enemies and sets himself up as a god of the Gnorrls. He has invented the spear-thrower and also understands military strategy. He takes on Hok in a spear-throwing contest and makes it obvious he wants Hok's wife, Oloana. The Gnorrls kill many of Hok's people and drive the survivors away. In desperation, Hok takes his bow and goes after Romm with only his wife beside him. The ending is exciting and pure pulp.

The invention of the bow is part of Jim Kjelgaard's Fire Hunter too. Both stories try to imagine how new weapons and tools are invented. The invention of the bow predates history, so anybody could be right. Arrowheads from 64,000 years ago have been discovered, so Wellman is certainly well within the right range. If neanderthals died out about 30,000 years ago, that would set these stories just before then, because I don't see the Gnorrls being around for much longer in the Hok sequels.

A little extra with this issue of Amazing was Manly Wade Wellman's bio. The Paizo book includes it as well. What makes this so special is that it appeared before the Silver John stories and is the Wellman who was largely known as an SF writer.

A little extra with this issue of Amazing was Manly Wade Wellman's bio. The Paizo book includes it as well. What makes this so special is that it appeared before the Silver John stories and is the Wellman who was largely known as an SF writer.A shorter and less impressive tale, "Hok and the Gift of Heaven" (Amazing Stories, March 1941) is still a pretty good read. Hok and his tribesmen are in the middle of a battle with the fisher folk when a meteorite falls on the battlefield. Hok is knocked unconscious and wakes to discover molten metal from the space rock. He uses this to create the first sword, which he names Widow-Maker. After the battle, Djoma and his fisher folk take Oloana and Ptao, Hok's wife and son. Hok follows the band back to the ocean and their village, which is built on stilts out in the water. Hok must face sharks and fight a battle against great odds that ends with him and his loved ones about to be sacrificed. Only a sudden surprise for the sword-wielding Djoma saves them. In the end, Hok gives up his sword and goes back to stone-age weapons. Wellman does a nice job of pitting Hok's Shining One (the Sun) against Djoma's sea-god in their arguments, perhaps the first theological disagreement of prehistory?

The final entry in the Hok saga is the longest, "Hok Visits the Land of Legend." Unlike the earlier installments, this one appeared not in Amazing Stories, but in Fantastic Adventures, April 1942. In this last tale, Hok is bored with the challenges of a hunter and decides to go after a mammoth on his own. He builds a giant bow and shoots a giant arrow into Gragru's chest, but the mammoth does not die. Hok follows his prey to a secret valley where the mammoths go to die. Here he is attacked by pterodactyls (at last! dinosaurs!) and fights and kills one in a fight reminiscent of Tarzan's visit to Pellucidar in 1929.

Then he discovers what he calls an elephant-pig (Dinoceras ingens) or Rmanth. The beast is devouring his dead mammoth. Hok shoots two arrows into the beast, but must flee into the trees. There he is saved by a voice from inside the tree. He enters a hole to find the tree hollow and inhabited by a man-like creature of slender build with prehensile feet. His name is Soko. He takes Hok to the village in the trees. (Jules Verne and Edgar Rice Burroughs may have inspired this, but Wellman's own upbringing in Africa is more likely.) The village is ruled by a tyrant named Krol who keeps the people under sway by allowing the pterodactyls (or Stymphs) to rule the tops of the trees, and the Rmanth to hold the ground. Hok fights the beasts and defeats the tyrant, leading to the legends of Hercules.

What struck me most about this tale was, first off, how far Wellman wandered from Wells' original, inspiring "The Grisly Folk," and how he made the series his own. Also, the basic plot set-up of this story is a dry-run for his classic John the Balladeer tale "O, Ugly Bird!" (F&SF, December 1951) in which a sorcerer uses a flying familiar to terrorize a rural community. Wellman liked stories in which a wandering hero (be he John or Kardios or Hok) comes to a troubled place and prevails. It is also a dry-run for The Last Mammoth (1953), a juvenile adventure novel about a friend of Davy Crockett's who goes to a far Indian village to kill a mammoth that is terrorizing them.

What struck me most about this tale was, first off, how far Wellman wandered from Wells' original, inspiring "The Grisly Folk," and how he made the series his own. Also, the basic plot set-up of this story is a dry-run for his classic John the Balladeer tale "O, Ugly Bird!" (F&SF, December 1951) in which a sorcerer uses a flying familiar to terrorize a rural community. Wellman liked stories in which a wandering hero (be he John or Kardios or Hok) comes to a troubled place and prevails. It is also a dry-run for The Last Mammoth (1953), a juvenile adventure novel about a friend of Davy Crockett's who goes to a far Indian village to kill a mammoth that is terrorizing them.Thus ends the Hok series, with Hok keeping the hidden valley a secret; returning to his people to live out his days in more fantastic adventures that would come down to us as the tales of heroes from Hercules to Beowulf.

There is one other story that lies close to the Hok series, "The Day of the Conquerers" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, January 1940), appearing after the first two Hok stories. In this science fiction tale, Martians armed with death rays and robots come to Earth to take over the planet. They are faced with an able opponent in Naku (or Lone Hunt), one of the Flint People. Since he is armed with a bow, the story must take place chronologically after Hok's life, for Hok invented the weapon and he makes no reference to alien invaders. So, Naku is one of Hok's descendants and a worthy warrior and cunning fighter.

The Paizo volume includes this story along with a one-page fragment of an unfinished Hok story and an unpublished tale called "The Love of Oloana." Most of this story was incorporated into "Battle in the Dawn." The introduction by David Drake adds a nice explanation of Wellman's youth in Africa. All-in-all, Battle in the Dawn: The Complete Hok the Mighty is a Wellman or pulp fan's dream and a completist's treasure.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on October 27, 2017 16:00