Clara Lieu's Blog, page 46

August 30, 2013

Something big

I’ve had a wonderfully eventful week, and the result is that I have some very big news coming up that I’m not allowed to announce just yet. All I can say is that I got quite possibly one of the best emails I’ve ever received in my entire life this week. Amazing how just a few typed words in an email will be dramatically changing my career very soon.

In other news, I visited the studio space at the Waltham Mills Artists Association in person and it looks like it’s going to happen. I am absolutely and completely thrilled. This will be my very first studio space ever. It sounds silly, but having a studio space makes me feel like a “real” artist, and I can’t wait to see how this is going to transform my artwork.

Between the studio space and my big news, I feel like I am now taking my career to a new level. I had been feeling over the past two years that I was at a plateau, and it finally feels like I am leaving that all behind.

Back to School Recommendation

Lucky is the student who gets Clara Lieu as their teacher. Currently she's an adjunct professor in the Freshman Foundation Program at Rhode Island School of Design. How do I know how good she is? I teach Sophomores at RISD, and one question I always ask my students in conferences is who they've had as influential teachers, to which all of Clara's ex-students reply, "I was lucky.

August 27, 2013

Ask the Art Professor: How do you get to the top of the art world?

Welcome to “Ask the Art Professor“! Essentially an advice column for visual artists, this is your chance to ask me your questions about being an artist, the creative process, career advice, a technical question about a material, etc. Anything from the smallest technical question to the large and philosophical is welcome. I’ll do my best to provide a thorough, comprehensive answer to your question. Submit your question by emailing me at clara(at)claralieu.com, or by posting here on this blog. All questions will be posted anonymously. Read an archive of past articles here.

Here’s today’s question:

“How do you get to the top of the art world? It seems nowadays (compared to the past) that there are just too many people out there doing it. With so many people out there who are technically brilliant with good work out there promoting their stuff it feels a bit like a giant crap shoot. Is it just all about luck and/or knowing the right people?”

If I truly knew the answer to this question, I would be there already.  Instead, I’ll provide my most educated guess at what it takes to get there. First of all, I’m going to define the “top” to be artists who are showing in internationally renowned galleries and museums, who are in art history textbooks, and who are winning MacArthur grants. I’m thinking of people like Shazia Sikander, Sarah Sze, Julie Mehretu, Tara Donovan, Jenny Saville, and John Currin, to name just a few examples. Many of these artists are so famous that they don’t even need to have their own personal websites!

Instead, I’ll provide my most educated guess at what it takes to get there. First of all, I’m going to define the “top” to be artists who are showing in internationally renowned galleries and museums, who are in art history textbooks, and who are winning MacArthur grants. I’m thinking of people like Shazia Sikander, Sarah Sze, Julie Mehretu, Tara Donovan, Jenny Saville, and John Currin, to name just a few examples. Many of these artists are so famous that they don’t even need to have their own personal websites!

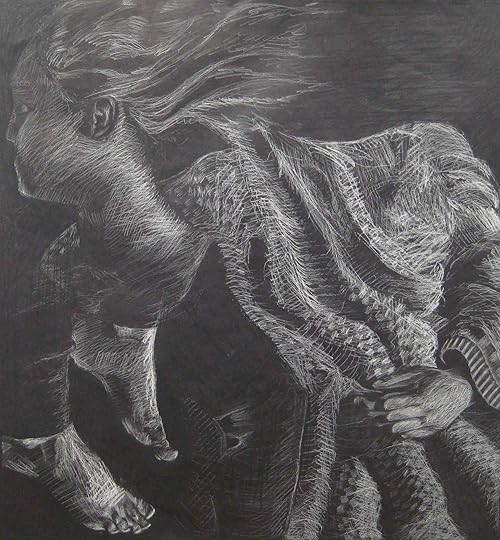

Jenny Saville

I think that a host of various factors have to come together in the right way to reach “the top”. There is definitely no artist who is able to get there by themselves; they have to have a support system in place that helps them get there. Connections with certain key people are undeniably part of the equation. This can be seen in concrete examples of the top artists today: Tara Donovan was a waitress at a New York City restaurant that Chuck Close used to frequent. Lisa Yuskavage was instrumental in getting Sarah Sze her first New York City gallery show. Jenny Saville was discovered by British collector Charles Saatchi.

Time and context also plays a huge role in how one’s artwork is received. Reception of an artwork can change dramatically depending on the historical context of the work. During the period of Abstract Expressionism, no one dared work with the human figure until Eric Fischl came along in the 80′s and resurrected that subject matter. For the time period that his work came about, his work was seen as revolutionary and gutsy. If Fischl’s work had emerged in a different time period, perhaps it would not have been received in the same manner.

While being in the right place at the right time can seem to be what determines everything, I have to argue that none of these artists would have made it if they hadn’t been ready at those critical moments. In other words, it doesn’t matter what kind of amazing opportunities you get if you aren’t prepared to take advantage of them. I am certain that every one of these artists who has “made it” has been working incredibly hard from the very beginning, and that it’s no accident that they were ready to go when the moment struck.

As for connections, remember that people only refer people who they are confident will represent their opinion well. People won’t want to help you if they don’t believe in the work that you’re doing. And to a certain degree you actually can control who you meet. These artists took initiative to position themselves to meet the right people; it’s no coincidence that almost all of them went to New York City, and that many of them completed their education of some of the most prestigious schools in the nation.

I don’t believe it’s a giant crap shoot, because luck and knowing the right people is really only half the battle. The other half is completely up to you.

Related articles:

“How do you know when your artwork is good enough to show to the world?”

“How do you get people to notice your artwork online?”

“When is it too early to start promoting your work on the Internet?”

“How do you retain the integrity of your artwork while promoting it?”

August 25, 2013

Ask the Art Professor: How would I go about studying the human body?

Welcome to “Ask the Art Professor“! Essentially an advice column for visual artists, this is your chance to ask me your questions about being an artist, the creative process, career advice, a technical question about a material, etc. Anything from the smallest technical question to the large and philosophical is welcome. I’ll do my best to provide a thorough, comprehensive answer to your question. Submit your question by emailing me at clara(at)claralieu.com, or by posting here on this blog. All questions will be posted anonymously. Read an archive of past articles here.

Here’s today’s question:

“How would I go about studying the human body? I am attempting to get a better idea of how to draw poses and I think I need to learn the body from the inside out. I’m just not sure how to go about doing this.”

The human figure is likely the most complex form studied by visual artists. One of the reasons why it’s so challenging to study is because the human figure is essentially a single form that can be continually subdivided into many smaller forms, making for an extraordinarily complex system. Depending on the person, the variations in form are infinite even though the basic structure is the same from person to person. Studying the human figure is one of the ultimate challenges of being an artist, and is an undertaking that lasts for many years.

Be sure that when you decide to study the human figure that you don’t mistake anatomical information for artistic application. I know artists who studied anatomy down to the absolute tiniest detail, but whose figure drawings were awful because they didn’t know how to apply their knowledge to their drawings. You could possess all of the information in the world about anatomy and still not know a thing about how to apply that knowledge in an artistic context. Understand that it’s the combination of knowledge and application together that will lead to an artistic comprehension of the human figure.

Since the skeleton is the most deeply embedded structure of the human figure, it makes sense to start there. The most ideal situation is to have a life size, plastic skeleton model that you can directly observe. However, if that is not an option, I recommend buying Dr. Paul Richer’s “Artistic Anatomy” book, which has good, simple drawings of the skeleton that you can draw from. Start out by doing very simple, basic drawings that approximate the major forms of the skeleton. Don’t let yourself fuss over every single rib or vertebrae, the larger concern is that you develop a thorough understanding of how all of the forms in the skeleton relate to each other. By doing many drawing studies of the skeleton, you’ll start to understand how all of the forms work together.

Once you have a grasp of the skeleton, it’s time to move onto other key concepts, working from a live model the whole time. I break this up into three steps:

1)Major Masses: Major masses are essentially the largest forms on the human figure. I recommend beginning a figure drawing by first addressing the torso, by far the largest form. The torso is where all of the limbs and the head intersect, so it’s critical to knock in the torso immediately when starting a figure drawing. The torso can then be subdivided into a ribcage and pelvis, which provides a sense of structure within the torso itself. From there, the head and thighs can be quickly added to provide more mass to the form. The limbs and the hands and feet should come in last.

2)Centerline: There is an imaginary centerline down the front of the torso and down the back of the torso. On the back of the torso, the centerline is easy to spot because it is basically the spine. On the front of the torso, the centerline starts at the pit of the neck, (the point in between the collarbones, aka clavicles) moves down the center of the rib cage, through the belly button down to the pubic bone on the pelvis. A centerline is highly descriptive of the type of pose that is being struck by a figure. Look at the centerline when a model is posing and ask yourself what the centerline is doing: is the centerline perfectly straight? Is it twisted, is it leaning to the right or left? If you quickly establish how the centerline is behaving in your figure drawing, you’ve won half the battle.

3)Boney Landmarks: Boney landmarks are areas on the human figure where the bone is directly under the surface of the skin. These landmarks are significant because they are consistent with every single person, regardless of how large or thin they may be. When you’re looking at a model, search for these boney landmarks and indicate them in your drawing. Some boney landmarks include: collar bones, elbows, kneecaps, ankle bones, shoulder blades, etc. Boney landmarks are considered to be details, so they should not be drawn in until the major masses and centerline are well established.

The final stage is to seek out key muscles on the human figure that are visible on the surface. Many muscles are hidden under other muscles, so it’s not necessary to learn every single muscle that there is on the human figure. Some examples of muscles that are visible on the surface would be the deltoids, the trapezius, the pectoralis major, the sartorius, etc. These muscles can all be seen in Dr. Paul Richer’s “Artistic Anatomy” book. Like the skeletons, do drawings of these major muscle groups from Richer’s book to get a sense for the forms.

Between the major masses, the centerline, the boney landmarks, the skeleton, and the muscles, you should be able to develop a comprehensive understanding of the human figure and it’s various forms and structures. You should be able to discern between muscle, bones, and skin in any area of the figure. Remember, drawing the human figure is not a skill that will happen overnight. It takes years and years of disciplined practice, tons of bad drawings, and rigorous focus. In this way, you will be able to accomplish a masterful understanding of the human figure.

Related articles:

“How do you draw the human face?”

“How can I learn to draw noses?”

“What is the best way to simplify the human figure?”

“How can you learn to draw hair?”

August 24, 2013

Interview with Dave Conrey at Fresh Rag

August 23, 2013

Ask the Art Professor: I need your questions!

Have you enjoyed my advice column, “Ask the Art Professor?” If yes, help me keep the column going by submitting some new questions! Submit your question by emailing me at clara(at)claralieu.com, or by commenting here on this blog. All questions will be posted anonymously, and you’ll receive notification when your question is online.

For now, have a look at this archive of past columns below.

On art school and degrees:

“What is the purpose of a degree in fine art?”

“When you have a fine arts degree, what do you do for the rest of your life?”

“How do you preserve your artistic integrity within the strict time limitations in an academic setting?”

“Is art education really so popular in western countries?”

“What do you do after you’ve finished formalized training?”

“Should art students study abroad even if it distracts from job preparation?”

“Who should you make art for, yourself or your professor?”

On college portfolio preparation:

“What are common mistakes in college portfolio submissions?”

“What should you include in an art portfolio for art school or college?”

On graduate school:

“Is graduate school worth it?”

“How are European MFA degrees viewed in the United States?”

On technique and skills:

“How can I tell if I’m skilled enough?”

“How do you find your own individual style?”

“How do artists manage to get their soul out into images?”

“How do you develop an idea from a sketch to a finished work?”

“How do you make an art piece more rich with details that will catch the eye?”

“How do you learn the basics?”

“Is it bad to start another piece of art before finishing another one?”

“How do you work in a series?”

“When and how should you use photo references to draw?”

On abstraction:

“How can I approach creating abstract art?”

“Does an abstract artist need to be proficient in traditional techniques?”

On painting & color:

“How do you achieve a luminous effect in a painting through color and value?”

“Does painting what you see limit your artistic possibilities?”

“What is the practical meaning of color theory?”

“How do you compose a striking painting with color?”

“Is hard work and experimenting continuously such a bad thing?”

On drawing:

“What is a gesture drawing?”

“Is drawing considered an innate talent or a craft, which can be learned by anyone?”

“How can I learn to shade objects in my drawings?”

“How can I draw what I see in my head?”

“What is the best way to practice my drawing skills?”

“How can you learn to draw hair?”

“How do you get yourself to practice drawing?”

“What is the best way to simplify the human figure?”

“How can I learn to draw noses?”

“ What is the most important mindset a student needs to have in order to create a successful drawing?”

“How do you draw the human face?”

On Promotion:

“How do you know when your artwork is good enough to show to the world?”

“How do you get people to notice your artwork online?”

“When is it too early to start promoting your work on the Internet?”

“How do you retain the integrity of your artwork while promoting it?”

On illustration:

“How do I become a children’s book illustrator?”

“Can I make a respectable income on freelance illustration?”

“Where is a good place to start with graphic novels?”

“What does t take to get a job at an animation studio?”

On galleries & museums:

“How do I leave my gallery?”

“How do you sell your art?”

“How do I approach a gallery?”

“How do museums select artists to exhibit? What is museum quality work?”

“How do I know I’m ready to start selling and approaching galleries?”

On doubt:

“Am I actually an artist?”

“How can one regain lost satisfaction with their work?”

“How do you gain confidence in your artwork?”

On learning:

“How do you keep pushing yourself to get to that next level?”

“Would you improve more if you took art classes than just studying on your own?”

“How do you learn the basics?”

“How do you break out of your comfort zone?”

“How do you get out of thinking you can’t get any better?”

“How do you develop patience for learning curves?”

“When do you let go of an idea?”

On teaching:

“How do I become an undergraduate art professor?“

“What should I be working on now if I would like to be an art professor?”

“What makes a student artist stand out from their peers?”

“How did you become an art professor?”

On life:

“How much of your emotional life do you allow to infiltrate your work?”

“How do you face artistic burnout?”

“How do you come up with ideas?”

On practical matters:

“What do you do for art storage?”

“How can an artist balance their life?”

“How can an artist overcome their financial issues?”

“How can an artist create an artistic group outside of school?”

Other:

“What is the most important thing you can do as an artist?“

“Does being an artist require much more thinking than in other academic fields?”

“What is the difference between fine arts and visual arts?”

“Will negative stereotypes about artists ever go away?”

“Is photography art?”

“What would you be looking for if you were judging for an art scholarship?”

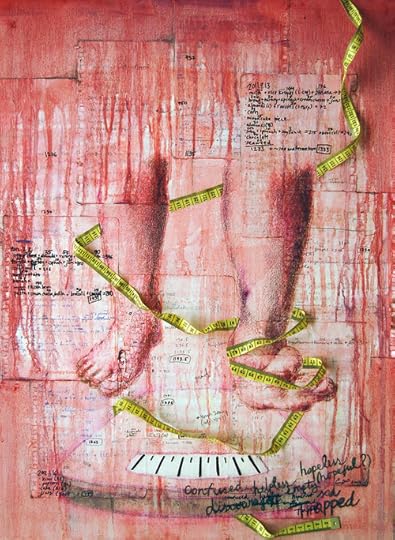

Crit Wall #18

Welcome to “Crit Wall“, where I offer online critiques of individual art pieces. To submit, send me a link to one image by commenting here, or by emailing the link to me at clara(at)claralieu.com. Please, NO ATTACHMENTS. Include the media, size, and title if you have one. Only submit original, finished works, no works in progress or sketches. Artwork created for a RISD degree program course is not eligible. You’ll receive notification if your piece is selected to be critiqued. Only one submission per person please, and know that I will not be able to critique every single work due to the volume of submissions. All images will be posted anonymously.

“Gotham City”

29″ x 23″

digital inkjet print

This is a very rich and exciting piece. Right away the piece establishes a dark and moody atmosphere through it’s agitated shapes and forms that seem to forcefully cut across the composition. There is a incredible rhythm to the movement of the shapes which is highly dynamic and powerful. The variety of shapes in this piece is extraordinary, and yet all of the shapes seem to be interconnected with each other and move fluidly with one another. While the composition does have a chaotic character to it, there certainly are a number of patterns within the piece that provide a sense of order within the chaos.

This is a piece that one would want to inspect for a long time; the details embedded within the composition are that mesmerizing and engaging. The piece makes an immediate, bold impact but at the same time has much to offer when examined in further detail.The larger shapes in the lower left hand corner have a heaviness and weight to them while the smaller shapes in the upper section of the piece appear to defy gravity the way that they move across the composition. The one aspect of the composition that could be better is the positioning of the area in the middle section with the red tones. This section is very exciting and calls much attention to itself, however its positioning in the dead center of the composition is too predictable. If there were some way to re-position this section so that it was higher or lower in the composition, this would make the composition more dynamic.

The more graphic shapes on the left are well contrasted against the crinkled forms on the right hand side. The crinkled forms on the right hand side have a vertical shape to them while the graphic shapes on the left move in a horizontal manner. The harsh, crisp, graphic shapes work well in contrast with the softer areas that are more atmospheric. The two areas transition very successfully from one section to the other; each section retains it’s own unique quality, yet they work together when shifting into the other area.

The sense of layering and transparency is extremely effective, creating a sense of depth that is very convincing and palpable. Many areas push forward and appear to leap out of the composition while others push back into the space fabricating deep sense of space. There is even a sense of a luminous light coming from behind these forms, which also enhances the translucency of certain areas.

The color is beautifully balanced throughout the entire piece. At first glance one might see this as a monochromatic piece, but upon deeper inspection it becomes clear how sophisticated the color scheme is. The warmth of the reds in the middle against the cool, greyish greens of the background work well together to create contrast and depth in the piece. Even the very slight and subtle passages of blue mixed in the middle of the work add a complexity in the color scheme.

It is impressive that this work stands on its own while referencing a number of different genres and artists. The piece is reminiscent of contemporary artists El Anatsui and Julie Mehretu, but without being derivative. There also seems to be a strong relationship with textiles, in terms of the patterns and colors being employed in this work.

Past “Crit Wall” pieces are below. Click on the images to read the critique.

August 22, 2013

Purgatory

Lately it seems like all I want to do is write and think. Searching for a studio space has been consuming my thoughts all day. I’m having a tough time wanting to start up anything major with my artwork until I find a work space. I know that I shouldn’t be waiting around, as it will likely take time before I find something. (still waiting on that space I mentioned a few posts back) I hate to admit it, but I feel paralyzed right now by my lack of studio space. This was one transition that I didn’t think was going to affect me so much.

I thought initially that I was going to want to just work on sketches for a long time, so working at home seemed like it would be okay. Actually, all I can feel right now is a strong itch to dive into the 7′ x 4′ drawings. I’m tired of the sketches. I’m yearning to draw something that is more refined, focused, detailed, and finished.

Ask the Art Professor: When and how you should use photo references to draw?

Welcome to “Ask the Art Professor“! Essentially an advice column for visual artists, this is your chance to ask me your questions about being an artist, the creative process, career advice, a technical question about a material, etc. Anything from the smallest technical question to the large and philosophical is welcome. I’ll do my best to provide a thorough, comprehensive answer to your question. Submit your question by emailing me at clara(at)claralieu.com, or by posting here on this blog. All questions will be posted anonymously. Read an archive of past articles here.

Here’s today’s question:

“When and how you should use photo references to draw?”

Too often I find that people use photo references out of laziness. Be careful that if you decide to work with photo references, that it’s for a very specific reason, not because of convenience. Photographs should only be used when direct observation of a subject is impossible. For a still life drawing, get the actual objects and set them so you can directly observe them from life. If you are drawing a self-portrait, it’s easy enough to get a large mirror and draw from that. Anything that you can possibly observe from life should be done in this way. Nothing can substitute experiencing a subject in real life: being able to touch it, smell it, walk around it, inspect it, etc. Staunchly set direct observation as your number one priority.

I’ve also seen many professional artists work with a variety of other references that are just as effective, if not more, than photo references. Artist James Gurney fabricates sculptures of dinosaurs for his paintings. After sculpting the dinosaur in clay, he paints the sculpture and then draws from the sculpture as his reference. You can watch him go through this process in this terrific video below. It goes to show that photographs are not the only option, and that other methods can provide a level of depth and understanding of a subject that photographs are incapable of providing.

Artist James Gurney on how he paints dinosaurs

If you’ve decided that photographs are indeed the only option for your drawing, the next stage is to do everything in your power to shoot the photographs yourself. If that means taking a trip to the zoo to take photographs of the gorillas, then do it. I know it’s very tempting to go on Google Images and simply pull a photograph off the Internet. However, when you use someone else’s photograph, your drawing will be vastly limited. You won’t be able to control the point of view, you can’t zoom in to get more details, and most likely the resolution of the photograph will be poor. Take the initiative to go to your subject and photograph it from every point of view, and get every detail that you need.

The only time I would advocate using someone else’s photograph as a reference is if there is absolutely, one hundred percent, no other way to get the visual information you need. For example, if you are doing an illustration of an elephant, and you need details of the wrinkles in the skin, that’s a circumstance where you’ll need to use someone else’s photograph. In general though, someone else’s photograph should be the last resort in terms of references.

When you do get to the point where you are working from a photograph, think about it as a process of gathering information which you then edit and manipulate. Nothing is worse than copying a photograph verbatim. If that is your intent, you might as well xerox the photograph and be done with it. Instead, take the information from the photograph and then process it, shift it, change it into something new and engaging. Be highly selective about what visual information you choose to use. Just because something is in the photograph, it doesn’t mean that you necessarily have to use it in your drawing. Think about yourself as an editor, where you get to choose from a vast buffet of visual information. Comb through all of the information in the photograph and use only what is going to help facilitate your drawing in a positive manner. I also find that it’s very helpful to work from multiple photographs, so that you are not so reliant on a single photograph for all of your information.

It’s extremely difficult to use a photographic reference well, very few people do it successfully. I firmly believe that the only way to truly learn how to draw from a photograph well is to establish a solid understanding of fundamentals in drawing with years and years of experience drawing from direct observation. Once you have solid skills drawing from direct observation, these skills will allow you to draw from a photograph successfully.

Related articles:

“How can I tell if I’m skilled enough?”

“How do you find your own individual style?”

“How do artists manage to get their soul out into images?”

“How do you develop an idea from a sketch to a finished work?”

“How do you make an art piece more rich with details that will catch the eye?”

“How do you learn the basics?”

“Is it bad to start another piece of art before finishing another one?”

“How do you work in a series?”

August 21, 2013

Ask the Art Professor: How do you draw the human face?

Welcome to “Ask the Art Professor“! Essentially an advice column for visual artists, this is your chance to ask me your questions about being an artist, the creative process, career advice, a technical question about a material, etc. Anything from the smallest technical question to the large and philosophical is welcome. I’ll do my best to provide a thorough, comprehensive answer to your question. Submit your question by emailing me at clara(at)claralieu.com, or by posting here on this blog. All questions will be posted anonymously. Read an archive of past articles here.

Here’s today’s question:

“I would like to ask if you have any tips for drawing the human face? I tend to have a hard time with proportions (I often draw the eyes way too large) and placement of different features in relation to each other.”

The human face is hands down the most intimidating subject matter for most artists. There is so much psychological baggage that comes with a human face that just is not there with other types of subject matter. We see and interact with human faces every day, and for many of us, it’s our primary form of visual communication when we talk in person. All of us are capable of knowing when something is “off” in a portrait drawing, although many of us wouldn’t necessarily be able to articulate exactly what it is that needs to be changed in the drawing. For this reason, we generally hold portraits to a much higher level of scrutiny, and are far more critical when it comes to getting results.

The major mistake that I see when approaching the human face is simply calling it a “face.” In actuality, you are drawing a human head. Artists spend so much time isolating their attention to the face only, that they miss out on establishing the bulk of the head, which is the supporting mass for the face. The face is actually a very small percentage of the head. Tell yourself that you are drawing a head, and that mentality will set the stage to have a more comprehensive understanding of what you’re doing.

The key to drawing the human face is to think about the underlying structure first, not what’s on the surface. This means really understanding the essential structure of the skull. I recommend starting out by drawing skulls before even beginning to draw the human face. Buy a plastic skull (you can get a decent one for about $40) and draw it from every point of view that you can come up with: three quarters view, straight on, profile, back, from below, etc. This process of careful observation of the skull will greatly improve your understanding of the human head.

The next step is to develop an understanding of where the subcutaneous areas are. Subcutaneous means “directly under the skin”, so you’re searching for areas of the head where the bone is directly under the surface of the skin. This would include the brow, the forehead, the cheek bones, the jawbone, and the chin. These subcutaneous areas are the sections of the head that you want to focus on and highlight in your drawing, as they will provide the structure for everything else to lie within.

The most common mistake that I see is when artists start out a portrait is by drawing the eyes, nose, and mouth first. Actually, the eyes, nose, and mouth should be the last forms that you draw. This is because there is technically nothing structural about the eyes, nose, and mouth. The eyes are soft squishy spheres, the nose is just cartilage, and the mouth is simply soft tissue. Start out by blocking in the bulk of the entire head first, and then the basic masses of the subcutaneous areas. (the brow, the forehead, the cheek bones, the jawbone, and the chin) Once these sections are established, very briefly block in loose shapes for the eyes, nose, and mouth. Then quickly move onto developing the supporting structures and muscle forms around the eyes, nose, and mouth. When these structures are well established, drawing in the eyes, nose, and mouth, should as easy as dropping sprinkles on a cupcake.

Proportions of the human head are another issue that many artists struggle with. The best advice I can give is to never spend too much time fussing over a single area. Instead, keep your arm moving from section to section, making adjustments along the way and constantly evaluating how one section relates to another. Allow all of the various parts of the draw to grow and develop at the same rate. Look at the nose in relation to the eyes, the eyes in relation to the ear, and so forth. If you work with a loose, gestural manner, and initially draw with very light, fluid lines, you’ll have a greater chance of knocking in the proportions properly.

Related articles:

“What is a gesture drawing?”

“Is drawing considered an innate talent or a craft, which can be learned by anyone?”

“How can I learn to shade objects in my drawings?”

“How can I draw what I see in my head?”

“What is the best way to practice my drawing skills?”

“How can you learn to draw hair?”

“How do you get yourself to practice drawing?”

“What is the best way to simplify the human figure?”

“How can I learn to draw noses?”

“ What is the most important mindset a student needs to have in order to create a successful drawing?”