T.S. Rhodes's Blog, page 8

October 17, 2016

Punishing Pirates – The Horror of the Gibbet

It’s the opening of Pirates of the Caribbean – Curse of the Black Pearl. Captain Jack in his raggedy rowboat sail past a string of hanging corpses. “Pirates Be Ye Warned” says the sign. Jack pauses his bailing to salute his fallen comrades, even as his own craft begins to sink.

These pirates were being “gibbeted” a horrible punishment, meant to inspire terror in potential wrong-doers.

Gibbeting was firmly rooted in Christian belief in the sanctity of the human body. Church doctrine said that in order to be raised on Judgement Day, a person needed to be buried “entire” – in other words, whole of body.

This belief inspired several medieval practices, including severing heads and displaying them on pikes, and cutting traitors into several pieces and sending the pieces to the far corners of a kingdom. Not only could the remains not be visited by followers, but the very gates of heaven were denied to the soul of the deceased.

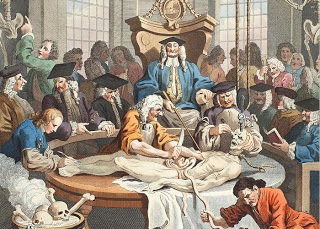

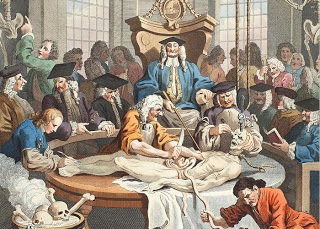

In London in the 1600’s the fate of executed pirates was a matter of great ceremony. A veritable parade, led by on official carrying a silver oar – symbol of the British Admiralty’s authority to rule the seas – led the condemned pirate to Execution Dock, located on the Thames River. The Admiralty’s authority began at the edge of the sea, and so the place of execution was located in the mud flats of the Thames, below the high tide line.

Here the pirate was hanged, and here the body would remain until it had been “washed by three tides.” The Thames at this point was close enough to the ocean that tides made the level of the river rise and fall. After the dead body had been through this ritual, it would be covered in tar and left on display until the corpse fell utterly apart.

The bodies of famous pirates were something of a tourist attraction, and the authorities wanted them to stay around for as long as possible. Most notable was the body of William Kidd. To this end, for certain pirates, a gibbet, or iron cage, was often made to surround the body.

There was no special design for these. Nobody published plans. Instead, officials went to a local blacksmith and ordered a gibbet to be made. Each one was its own gristly work of art. Some were designed to simply hold the body, letting the arms and legs flop loose. Others contained the appendages in their own iron supports – either jointed, for eerie movement, or held firmly still by iron bands. Some held the whole body, like a loosely woven iron mummy.

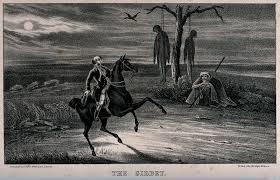

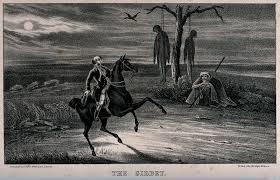

Gibbets weren’t just for pirates, of course. Other criminals – murderers especially, were contained after death in similar structures. The classic location for display of these remains was a crossroads. It was popularly believed that – should the dead man get loose from his confines and decide to go for a stroll that the many choices of direction would keep him from finding his way into town.

Gibbets were designed for maximum horror. The point of the iron container was to hold the body in the shape of a human. Gibbets were hung out of reach of passersby, and suspended by chains designed to move and rattle in the wind. When they were first put up, crowds would gather in a kind of macabre holiday.

But very soon, the horror would set in. First was the smell. People living downwind suffered, and needed to close their windows when the wind blew from the gibbet. Animals – birds, and small predators, gathered to feed, and their activities could be plainly seen. In the early days, brave little boys might dare each other to play near the corpse. Lovers might meet near the gibbet, sure of being alone.

But as time went by, the place grew more and more horrible, and a tarred body might last – to some degree – for decades. The remains of William Kidd are said to have hung for twenty years. Bits of bone might be found under the gibbet, and strange plants were said to grown there… Believable, since the area was most horribly fertilized.

In the end, gibbeting fell out of favor. Early Victorians finally made the connection between filth and sickness. And the gibbet’s goal of preventing crime had not materialized. In fact, the gibbet was a location of yet more murders, such as a case where one servant girl invited her friend to a picnic near such a place, then poisoned her.

The finally gibbet in England was removed by the nearby townspeople in 1832, and two years later the practice was officially banned.

But, strangely enough, some of the hanging corpses on the gibbet achieved a kind of immortality. In a time of unmarked roads, when people navigated by landmarks, a body in a gibbet was notable enough – and long-lasting enough – to be noted by travelers. So we have place names like Old Paar Road, named for the corpse of a murderer who had once marked a crossroads.

These pirates were being “gibbeted” a horrible punishment, meant to inspire terror in potential wrong-doers.

Gibbeting was firmly rooted in Christian belief in the sanctity of the human body. Church doctrine said that in order to be raised on Judgement Day, a person needed to be buried “entire” – in other words, whole of body.

This belief inspired several medieval practices, including severing heads and displaying them on pikes, and cutting traitors into several pieces and sending the pieces to the far corners of a kingdom. Not only could the remains not be visited by followers, but the very gates of heaven were denied to the soul of the deceased.

In London in the 1600’s the fate of executed pirates was a matter of great ceremony. A veritable parade, led by on official carrying a silver oar – symbol of the British Admiralty’s authority to rule the seas – led the condemned pirate to Execution Dock, located on the Thames River. The Admiralty’s authority began at the edge of the sea, and so the place of execution was located in the mud flats of the Thames, below the high tide line.

Here the pirate was hanged, and here the body would remain until it had been “washed by three tides.” The Thames at this point was close enough to the ocean that tides made the level of the river rise and fall. After the dead body had been through this ritual, it would be covered in tar and left on display until the corpse fell utterly apart.

The bodies of famous pirates were something of a tourist attraction, and the authorities wanted them to stay around for as long as possible. Most notable was the body of William Kidd. To this end, for certain pirates, a gibbet, or iron cage, was often made to surround the body.

There was no special design for these. Nobody published plans. Instead, officials went to a local blacksmith and ordered a gibbet to be made. Each one was its own gristly work of art. Some were designed to simply hold the body, letting the arms and legs flop loose. Others contained the appendages in their own iron supports – either jointed, for eerie movement, or held firmly still by iron bands. Some held the whole body, like a loosely woven iron mummy.

Gibbets weren’t just for pirates, of course. Other criminals – murderers especially, were contained after death in similar structures. The classic location for display of these remains was a crossroads. It was popularly believed that – should the dead man get loose from his confines and decide to go for a stroll that the many choices of direction would keep him from finding his way into town.

Gibbets were designed for maximum horror. The point of the iron container was to hold the body in the shape of a human. Gibbets were hung out of reach of passersby, and suspended by chains designed to move and rattle in the wind. When they were first put up, crowds would gather in a kind of macabre holiday.

But very soon, the horror would set in. First was the smell. People living downwind suffered, and needed to close their windows when the wind blew from the gibbet. Animals – birds, and small predators, gathered to feed, and their activities could be plainly seen. In the early days, brave little boys might dare each other to play near the corpse. Lovers might meet near the gibbet, sure of being alone.

But as time went by, the place grew more and more horrible, and a tarred body might last – to some degree – for decades. The remains of William Kidd are said to have hung for twenty years. Bits of bone might be found under the gibbet, and strange plants were said to grown there… Believable, since the area was most horribly fertilized.

In the end, gibbeting fell out of favor. Early Victorians finally made the connection between filth and sickness. And the gibbet’s goal of preventing crime had not materialized. In fact, the gibbet was a location of yet more murders, such as a case where one servant girl invited her friend to a picnic near such a place, then poisoned her.

The finally gibbet in England was removed by the nearby townspeople in 1832, and two years later the practice was officially banned.

But, strangely enough, some of the hanging corpses on the gibbet achieved a kind of immortality. In a time of unmarked roads, when people navigated by landmarks, a body in a gibbet was notable enough – and long-lasting enough – to be noted by travelers. So we have place names like Old Paar Road, named for the corpse of a murderer who had once marked a crossroads.

Published on October 17, 2016 18:38

October 10, 2016

Turtle Soup and Pirates

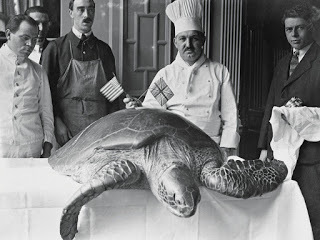

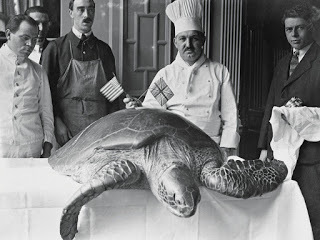

One of the great foods of the 18th century… Indeed, of centuries before, and at least one century afterwards, was turtle. Slow moving, plentiful, and tasty, turtles were a preferred food, especially for sailors.

On merchant and navy ships, turtles of all kinds, but especially sea turtles, were kept in ship’s holds as a ready food source. The animals needed little space, and their slow-moving metabolisms allowed them to live for months on little or no food. A section of the ship could be petitioned off for turtle storage, and the animals would stay there, alive, until they were needed for dinner.

To people today, myself included, this seems horrific. Keeping an animal in close confinement, without food or water or any of the possible pleasures of life, feels like an assault on the morals of eating. Yet men like the pirates of old faced disease and death due to lack of fresh food. They needed the calories and nutrition that fresh turtle meat provided.

And, in many ways, it wasn’t much worse than a modern-day factory farm.

I’ve got my own opinions about turtles, formed not in the least because of my beloved pet, Karai, a Midwestern box turtle (technically a tortoise.) She chirps pleasantly, and watches TV with me, and eats strawberries, I would never eat her or any of her kin. So I’ve decided to look at turtle hunting and eating as a history lesson.

During the Golden Age of Piracy, turtles were plentiful on the beaches and islands of the Caribbean. Many tales of pirates also involve turtle hunting, or “turtling” as it was called. When Anne Bonny and Jack Rackham went looking for the man who betrayed them to Woods Rogers, the Nassau governor, they found him as he was hunting turtles.

When Charles Vane was shipwrecked on an empty island, he survived by eating turtles.

Pirates, known to taking to shore for drinking parties, often celebrated with turtle soup.

The first actual record of eating turtles in the New World goes all the way back to 1609, when a group of Englishmen, shipwrecked in Bermuda, finally headed toward Virginia on the the Sea Venture, along with supplies of turtle meat.

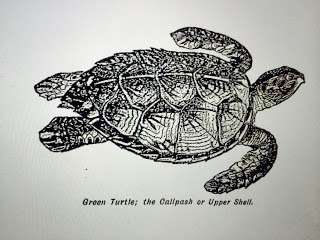

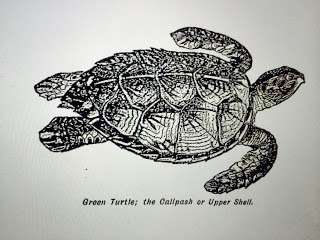

Indeed, 17thcentury over-turtling resulted in some of the very earliest efforts to protect wildlife. But this very early form of environmental protection didn’t work. The turtle population was decimated in Bermuda. So aspiring turtle-eaters had to go farther afield. Most popular, and supposedly the best eating, were giant sea turtles, some weighing over 400 pounds. One of the benefits was that the turtle yielded a pot to cook itself in – the turtle’s top shell made a suitable cooking pot.

I won’t go into the methods of killing a sea turtle – but the usual method was quick. Once the shell was cut open, the animal supplied 3 sections of meat. The forequarters (musculature that moved the head a front flippers) the rear quarters (muscles that moved the tail and hind feet) and a narrow band of muscle along the shell that joined them. Unlike other animals, turtles don’t have much in the middle.

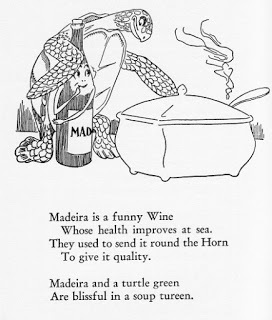

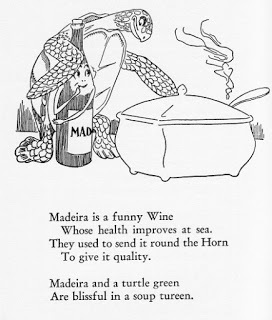

A typical recipe for turtle soup “in the wild” suggested cooking and eating the center loin muscles, then chopping up the rest of the meat, adding spices (thyme, parsley, savory and young onions, according to one recipe) and a couple of bottle of wine. The turtle’s tripe and maw (the digestive tract) were considered the best part, and cooks encouraged them to be boiled in veal stock, with plenty of added butter. Killing and dressing a 400 pound turtle took hours. And cooking it took even more. 6-8 hours were needed to prepare the dish.

The resulting soup was apparently quite addicting, and those who ate it soon wanted more. This led to price increases, as rich men in England were clamoring for the famous soup. In short order, turtle soup became known as the food of the wealthy.

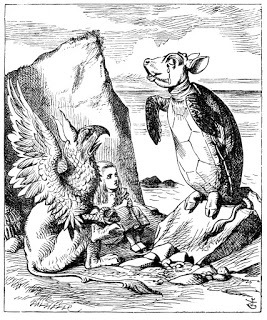

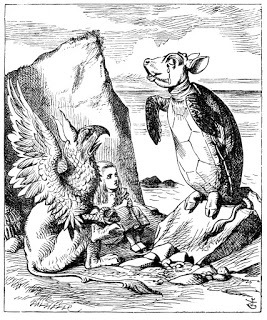

In response, England’s middle class soon created a dish called mock (fake) turtle soup. The recipe for THIS started with a calf’s head (the bony, cartilage-rich head helped create the slightly gelatinous texture of Real Soup) and included beef, chicken stock, lemon, herbs, tomatoes, wine and grated hard boiled eggs.

The taste of real turtle flesh is said to be a cross between crab and beef. Apparently this came close. It was wildly popular for nearly a century, and can still be found in some upscale restaurants. The image of the Mock Turtle can also be found in Alice in Wonderland, where Lewis Carroll described an animal with the body of a turtle, but the head and feet of a calf. (Calf’s feet were sometimes used to make mock turtle soup instead of the head.)

Why do people no longer eat real turtle soup? One reason is that many turtles are now protected as endangered species. Another is probably that once more people lived in cities, they no longer ate nearly such a wide variety of creatures. Our ancestors thought nothing of devouring raccoons, opossums, parrots, monkeys, and any other meat that became available. In this wild variety, turtle fit right in. To modern folk, it’s far more exotic, and maybe a little frightening.

Turtle soup, food to former presidents, kings, nobles and pirates, can now be had only in the most expensive and exotic of eateries. Or the most primitive. Cajuns and rural southerners still have turtle hunts, and make delicious soup from the animals captured.

And this is why the historical turtle soup is a uniquely piratical dish. The people who ate it were the wealthy… and the very poor. The lure of selling turtle meat for profit never seems to have persuaded poor sailors from enjoying the dish, and they benefited from the healthful properties of wild-caught ocean protein.

Event today, it’s well known that the healthier, more varied diets available to the rich grant longer life. In the 1700’s pirates grabbed a little bit of this “good life” for themselves.

On merchant and navy ships, turtles of all kinds, but especially sea turtles, were kept in ship’s holds as a ready food source. The animals needed little space, and their slow-moving metabolisms allowed them to live for months on little or no food. A section of the ship could be petitioned off for turtle storage, and the animals would stay there, alive, until they were needed for dinner.

To people today, myself included, this seems horrific. Keeping an animal in close confinement, without food or water or any of the possible pleasures of life, feels like an assault on the morals of eating. Yet men like the pirates of old faced disease and death due to lack of fresh food. They needed the calories and nutrition that fresh turtle meat provided.

And, in many ways, it wasn’t much worse than a modern-day factory farm.

I’ve got my own opinions about turtles, formed not in the least because of my beloved pet, Karai, a Midwestern box turtle (technically a tortoise.) She chirps pleasantly, and watches TV with me, and eats strawberries, I would never eat her or any of her kin. So I’ve decided to look at turtle hunting and eating as a history lesson.

During the Golden Age of Piracy, turtles were plentiful on the beaches and islands of the Caribbean. Many tales of pirates also involve turtle hunting, or “turtling” as it was called. When Anne Bonny and Jack Rackham went looking for the man who betrayed them to Woods Rogers, the Nassau governor, they found him as he was hunting turtles.

When Charles Vane was shipwrecked on an empty island, he survived by eating turtles.

Pirates, known to taking to shore for drinking parties, often celebrated with turtle soup.

The first actual record of eating turtles in the New World goes all the way back to 1609, when a group of Englishmen, shipwrecked in Bermuda, finally headed toward Virginia on the the Sea Venture, along with supplies of turtle meat.

Indeed, 17thcentury over-turtling resulted in some of the very earliest efforts to protect wildlife. But this very early form of environmental protection didn’t work. The turtle population was decimated in Bermuda. So aspiring turtle-eaters had to go farther afield. Most popular, and supposedly the best eating, were giant sea turtles, some weighing over 400 pounds. One of the benefits was that the turtle yielded a pot to cook itself in – the turtle’s top shell made a suitable cooking pot.

I won’t go into the methods of killing a sea turtle – but the usual method was quick. Once the shell was cut open, the animal supplied 3 sections of meat. The forequarters (musculature that moved the head a front flippers) the rear quarters (muscles that moved the tail and hind feet) and a narrow band of muscle along the shell that joined them. Unlike other animals, turtles don’t have much in the middle.

A typical recipe for turtle soup “in the wild” suggested cooking and eating the center loin muscles, then chopping up the rest of the meat, adding spices (thyme, parsley, savory and young onions, according to one recipe) and a couple of bottle of wine. The turtle’s tripe and maw (the digestive tract) were considered the best part, and cooks encouraged them to be boiled in veal stock, with plenty of added butter. Killing and dressing a 400 pound turtle took hours. And cooking it took even more. 6-8 hours were needed to prepare the dish.

The resulting soup was apparently quite addicting, and those who ate it soon wanted more. This led to price increases, as rich men in England were clamoring for the famous soup. In short order, turtle soup became known as the food of the wealthy.

In response, England’s middle class soon created a dish called mock (fake) turtle soup. The recipe for THIS started with a calf’s head (the bony, cartilage-rich head helped create the slightly gelatinous texture of Real Soup) and included beef, chicken stock, lemon, herbs, tomatoes, wine and grated hard boiled eggs.

The taste of real turtle flesh is said to be a cross between crab and beef. Apparently this came close. It was wildly popular for nearly a century, and can still be found in some upscale restaurants. The image of the Mock Turtle can also be found in Alice in Wonderland, where Lewis Carroll described an animal with the body of a turtle, but the head and feet of a calf. (Calf’s feet were sometimes used to make mock turtle soup instead of the head.)

Why do people no longer eat real turtle soup? One reason is that many turtles are now protected as endangered species. Another is probably that once more people lived in cities, they no longer ate nearly such a wide variety of creatures. Our ancestors thought nothing of devouring raccoons, opossums, parrots, monkeys, and any other meat that became available. In this wild variety, turtle fit right in. To modern folk, it’s far more exotic, and maybe a little frightening.

Turtle soup, food to former presidents, kings, nobles and pirates, can now be had only in the most expensive and exotic of eateries. Or the most primitive. Cajuns and rural southerners still have turtle hunts, and make delicious soup from the animals captured.

And this is why the historical turtle soup is a uniquely piratical dish. The people who ate it were the wealthy… and the very poor. The lure of selling turtle meat for profit never seems to have persuaded poor sailors from enjoying the dish, and they benefited from the healthful properties of wild-caught ocean protein.

Event today, it’s well known that the healthier, more varied diets available to the rich grant longer life. In the 1700’s pirates grabbed a little bit of this “good life” for themselves.

Published on October 10, 2016 20:37

October 3, 2016

Run Aground!

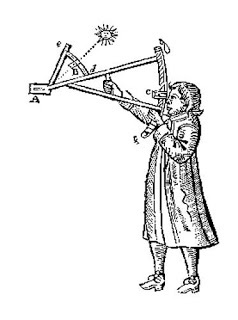

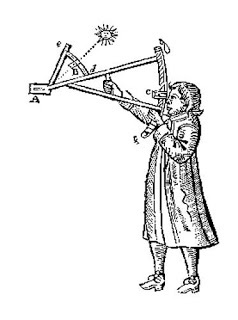

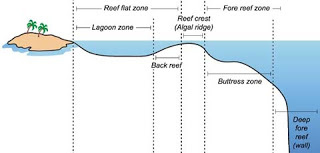

First one must imagine sailing during the early 18thcentury. Navigation was as much an art as a science. The compass showed north, and calculations gave a good approximation of the latitude (the distance north or south of the equator) but no one had yet figured out how to calculate longitude (the distance from east to west.) Because of this, it was impossible to ever tell exactly where you were.

Most navigators also used a version of navigation called “ded reckoning.” This worked by making notes to the effect of “we traveled northwest for 6 hours at about 7 knots, and then turned and traveled for 2 hours at about 4 knots.” Assuming that you knew where you were when you started and did the math right, you could figure where you were at the end of the day.

If you think this seems like a terrifyingly vague way to determine where you were you would be right. Add to this that many European ships were traveling to places that they had no record of, and you have a recipe for disaster.

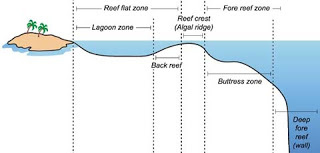

Ships ran aground. This happened when the bottom of the bottom of the ship (like icebergs ship have a lot of their bulk underneath the water) hit the bottom of the sea (coral reef, rock outcropping or shore.) Because all this was happening underwater, it was hard to tell how deep the water under the boat was.

Ships tried to get information about the bottom of the sea by dropping a piece of lead coated with wax and tied to a string. Once the lead weight hit the bottom it would be pulled up and examined. The length of the string told how deep the bottom was, and whatever stuck to the wax gave an indication of what was down there… It might be soft sand or hard rock.

This system was far better than nothing, but a sudden change might leave a ship bumping along the bottom. If the ship struck hard enough, it might run aground.

A grounded ship was in trouble. Striking a hard surface would damage the bottom of the boat, allowing water to get in. This was when the ship’s carpenter might show his skills. A good carpenter might be able to plug any holed before the ship took on too much water.

But even if the hull was not damaged, or the damage could be repaired, the ship was now stuck. Friction with the sea bottom might prevent the vessel from moving.

The crew could do many things to get off the underwater hazard. In some cases a rising tide might simply lift the ship clear. But if the accident happened when the tide was already high, a receding tide might leave the ship literally high and dry.

Ships were not designed to hang in the air, supported at one point by a solid object, but with other parts dangling unsupported. Some ships came through accidents like this but in many cases the keel (essentially the spine of the ship) broke. A ship with a broken keel was damaged beyond repair. The crew’s only recourse was to load supplies into smaller boats and try to get home some other way, or to move supplies to the nearest shore, assuming an island or mainland was nearby.

Another method was to lighten the ship. Cannons could be thrown overboard (each cannon might weigh as much as several tons) or heavy cargo could be pitched over the side or if the crew was lucky, hauled to a nearby shore. If the crew was desperate, even the precious drinking water might be pumped over the side.

These actions might allow the ship to float free on the next high tide.

Other actions taken to free s ship that had run aground included running a line to another ship, or even a small boat, and attempting to tow the larger sailing ship clear. Obviously efforts would also be made to harness the wind to drive the vessel off the ground. Once again, if some other kind of solid matter – an island perhaps – was close enough, rope might be tied to anything handy, such a spike run into rock or perhaps a palm tree, in an effort to haul the ship free.

If the vessel was stuck in mud, it might have an un-damaged hull and yet be held firm by suction. In order to break the tension of the mud, the crew might try moving suddenly form one side of the ship to the other, trying to cause enough side-to-side movement that the suction would break. War ships sometimes fired their guns into a muddy entrapment, hoping the shock and vibration would set them free.

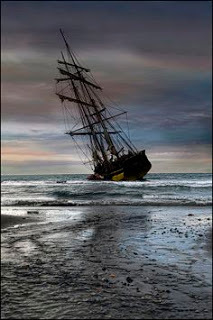

These were the good ways to run aground.

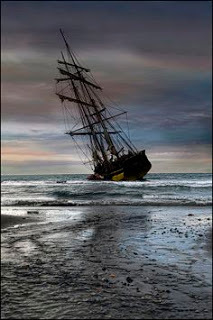

The worst way was to be blown onto a rocky shore by storm winds. This was every sailor’s nightmare. On a dark night or in an unfamiliar place, the grounding might come without warning. The momentum of the ship would put a terrible strain on the masts, and it was very common for them to break.

The loss of masts and therefor sails, meant that the ship lost all headway. This put it at the mercy of the sea. With no forward momentum, the ship would turn broadside to the waves. And if the seas were high, waves could wash up over the deck. A strong enough sea might even roll a ship upside down.

This was the disaster that sunk the mighty pirate ship Whydah, flipping her upside down and killing all but 7 of her 150 man crew. It destroyed the Spanish Treasure Fleet of 1715, wiping out 11 out of 12 vessels and strewing gold over Florida’s coasts, and dropping so many doubloons into the sea that they are still washing ashore today.

So, if you go sailing, thank your lucky stars that we now have accurate maps not only of the coasts but of the sea’s bottom as well. And thank them again for boat motors and GPS. Sailing is safer now, though less romantic.

Most navigators also used a version of navigation called “ded reckoning.” This worked by making notes to the effect of “we traveled northwest for 6 hours at about 7 knots, and then turned and traveled for 2 hours at about 4 knots.” Assuming that you knew where you were when you started and did the math right, you could figure where you were at the end of the day.

If you think this seems like a terrifyingly vague way to determine where you were you would be right. Add to this that many European ships were traveling to places that they had no record of, and you have a recipe for disaster.

Ships ran aground. This happened when the bottom of the bottom of the ship (like icebergs ship have a lot of their bulk underneath the water) hit the bottom of the sea (coral reef, rock outcropping or shore.) Because all this was happening underwater, it was hard to tell how deep the water under the boat was.

Ships tried to get information about the bottom of the sea by dropping a piece of lead coated with wax and tied to a string. Once the lead weight hit the bottom it would be pulled up and examined. The length of the string told how deep the bottom was, and whatever stuck to the wax gave an indication of what was down there… It might be soft sand or hard rock.

This system was far better than nothing, but a sudden change might leave a ship bumping along the bottom. If the ship struck hard enough, it might run aground.

A grounded ship was in trouble. Striking a hard surface would damage the bottom of the boat, allowing water to get in. This was when the ship’s carpenter might show his skills. A good carpenter might be able to plug any holed before the ship took on too much water.

But even if the hull was not damaged, or the damage could be repaired, the ship was now stuck. Friction with the sea bottom might prevent the vessel from moving.

The crew could do many things to get off the underwater hazard. In some cases a rising tide might simply lift the ship clear. But if the accident happened when the tide was already high, a receding tide might leave the ship literally high and dry.

Ships were not designed to hang in the air, supported at one point by a solid object, but with other parts dangling unsupported. Some ships came through accidents like this but in many cases the keel (essentially the spine of the ship) broke. A ship with a broken keel was damaged beyond repair. The crew’s only recourse was to load supplies into smaller boats and try to get home some other way, or to move supplies to the nearest shore, assuming an island or mainland was nearby.

Another method was to lighten the ship. Cannons could be thrown overboard (each cannon might weigh as much as several tons) or heavy cargo could be pitched over the side or if the crew was lucky, hauled to a nearby shore. If the crew was desperate, even the precious drinking water might be pumped over the side.

These actions might allow the ship to float free on the next high tide.

Other actions taken to free s ship that had run aground included running a line to another ship, or even a small boat, and attempting to tow the larger sailing ship clear. Obviously efforts would also be made to harness the wind to drive the vessel off the ground. Once again, if some other kind of solid matter – an island perhaps – was close enough, rope might be tied to anything handy, such a spike run into rock or perhaps a palm tree, in an effort to haul the ship free.

If the vessel was stuck in mud, it might have an un-damaged hull and yet be held firm by suction. In order to break the tension of the mud, the crew might try moving suddenly form one side of the ship to the other, trying to cause enough side-to-side movement that the suction would break. War ships sometimes fired their guns into a muddy entrapment, hoping the shock and vibration would set them free.

These were the good ways to run aground.

The worst way was to be blown onto a rocky shore by storm winds. This was every sailor’s nightmare. On a dark night or in an unfamiliar place, the grounding might come without warning. The momentum of the ship would put a terrible strain on the masts, and it was very common for them to break.

The loss of masts and therefor sails, meant that the ship lost all headway. This put it at the mercy of the sea. With no forward momentum, the ship would turn broadside to the waves. And if the seas were high, waves could wash up over the deck. A strong enough sea might even roll a ship upside down.

This was the disaster that sunk the mighty pirate ship Whydah, flipping her upside down and killing all but 7 of her 150 man crew. It destroyed the Spanish Treasure Fleet of 1715, wiping out 11 out of 12 vessels and strewing gold over Florida’s coasts, and dropping so many doubloons into the sea that they are still washing ashore today.

So, if you go sailing, thank your lucky stars that we now have accurate maps not only of the coasts but of the sea’s bottom as well. And thank them again for boat motors and GPS. Sailing is safer now, though less romantic.

Published on October 03, 2016 21:17

September 26, 2016

Mermaids and Pirates

“On the previous day, when the Admiral went to the Rio del Oro [on Haiti], he said he quite distinctly saw three mermaids, which rose well out of the sea; but they are not so beautiful as they are said to be, for their faces had some masculine traits.”Source – Christopher Columbus – in the Caribbean - January 9, 1493

Sightings of mermaids have taken place all over the world. Even the famed pirate Blackbeard is said to have sighted them, and to have kept away from certain areas, for fear of encountering more of the creatures.

The earliest surviving tale of these creatures, half-woman and half fish, date from about 3,000 years ago. The story involves the goddess who, upset because she had accidentally killed her human lover, throws herself into the sea. Perhaps she had contemplated suicide, but her divine virtue protected both her life and her beauty, transforming only her lower half into a fish, while maintaining her lovely face and allowing her to live under the waves.

According to legend, Alexander the Great’s sister was transformed into a mermaid. She would stop passing ships, and ask if Alexander still ruled. If told that he still ruled and conquered, she would quiet the sea, but if told the truth, that Alexander had died years before, she would raise up a storm.

Some believe that the magical powers of mermaids come from association with sirens. Others believe that the two are one and the same. This give rise, not only to tales of magical powers, but legend of mermaids who rise from the depths to drag men down to their doom.

Whatever their origin, mermaids are conceived as beings more than mortal. It is said that they live eternally, unless killed, and that they have the power to bring good luck or bad luck. Some are perceived as beings with a fish’s tail, but others are said to be exactly like humans. These mermaids are sometimes seen on land. One such tale tells of a very young mermaid who came onto land to steal a little girl’s doll.

In this story, the mother mermaid appeared with her child the next day. She made her daughter apologize for the theft, and give the little human a necklace of valuable pearls in return.

So apparently mermaids are good parents.

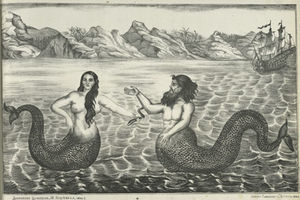

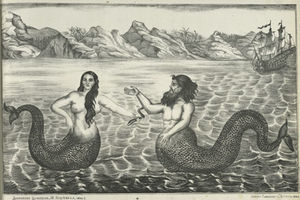

Where there are mermaids, of course, there are mermen. Mermen are not nearly as widely reported as their female counterparts, but they do exist, and it is generally assumed that they live together under the waves. Mermen, however, are usually described as being hairy and wild-looking, even brutish. Perhaps this explains the fascination that females of the species have with passing sailors.

Of course, tastes in masculine beauty have changed over the years. A modern viewer might see a brawny-chested, bearded merman as quite a “catch.”

Of course, tastes in masculine beauty have changed over the years. A modern viewer might see a brawny-chested, bearded merman as quite a “catch.”

Of course, the most famous of these under-sea creatures is The Little Mermaid. Many people will be surprised to learn that the story is much older than Disney. In fact, it was written by Hans Christian Andersen in 1837. In this story, the Little Mermaid wants, not only to marry the handsome prince, but also to achieve a human soul. Though she trades her tongue and voice to a sea-witch, and endures terrible trials, the prince ultimately marries another.

At this point the Mermaid’s sisters also deal with the sea-witch, and get an enchanted knife that will return their sister to her original state if she kills the prince with it. Yet the Little Mermaid’s love is true. She cannot kill the prince, but throws herself into the sea to drown. Her only consolation is to be changed to sea-foam, and then into an air spirit, which has the chance to win a soul by doing good deeds.

Disney’s version of the story is credited with rejuvenating the studio.

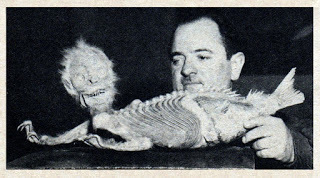

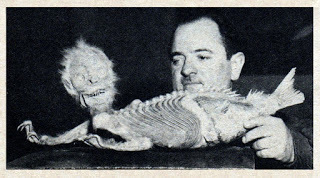

The fact that mermaids are not real has never stopped humans, however. Many, many false mermaids, usually an artificially attached money and fish, have been shown in various places. The most famous, the Fiji Mermaid, was concocted by P.T. Barnum.

But what did sailors see during the Golden Age of Piracy? Or even today, for that matter, because sightings are still reported? The “mermaid” is usually supposed to be a manatee or a dugong. These sea-mammals are known to sit upright in the water, and use their flippers much like hands. Still, it would take a desperate man, or one with a very vivid imagination, to see a beautiful woman in one of these!

But the human imagination is powerful. Without any actual mermaids, people have resorted to creating their own. One such attraction is Weeki Wachee Springs in Florida. Beginning in 1947, a natural spring was turned into an underwater theater, where beautiful young women wearing fabric tails would perform underwater ballet.

The attraction is now a state park and performances are still held, though the performers are now part time, and all are licensed scuba divers.

More recently we’ve seen mermaids in Pirates of the Caribbean. Many people were shocked to see the man-eating version of these beautiful creatures, but the Pirate’s franchise was only honoring all the lore of mermaids – including their ability to walk on land.

Mermaids have many fans, and mermaid clubs are springing up all over. It’s a popular Halloween costume, and fabric tails for kids can be purchased for as little as $5.99. But if you want the real thing – a custom-made silicone tail that will convince your friends and family that you’ve actually turned “fishy” you can have that too.

Of course, these come with a steep price, meaning several thousands of dollars. But for a true mermaid fan, no expense is too great. Nowadays mermaid pools, with ladies (and gentlemen) in this high-end swimwear can be seen at many pirate events, and even at Renaissance Fairs.

I wonder what Columbus would have to say?

Sightings of mermaids have taken place all over the world. Even the famed pirate Blackbeard is said to have sighted them, and to have kept away from certain areas, for fear of encountering more of the creatures.

The earliest surviving tale of these creatures, half-woman and half fish, date from about 3,000 years ago. The story involves the goddess who, upset because she had accidentally killed her human lover, throws herself into the sea. Perhaps she had contemplated suicide, but her divine virtue protected both her life and her beauty, transforming only her lower half into a fish, while maintaining her lovely face and allowing her to live under the waves.

According to legend, Alexander the Great’s sister was transformed into a mermaid. She would stop passing ships, and ask if Alexander still ruled. If told that he still ruled and conquered, she would quiet the sea, but if told the truth, that Alexander had died years before, she would raise up a storm.

Some believe that the magical powers of mermaids come from association with sirens. Others believe that the two are one and the same. This give rise, not only to tales of magical powers, but legend of mermaids who rise from the depths to drag men down to their doom.

Whatever their origin, mermaids are conceived as beings more than mortal. It is said that they live eternally, unless killed, and that they have the power to bring good luck or bad luck. Some are perceived as beings with a fish’s tail, but others are said to be exactly like humans. These mermaids are sometimes seen on land. One such tale tells of a very young mermaid who came onto land to steal a little girl’s doll.

In this story, the mother mermaid appeared with her child the next day. She made her daughter apologize for the theft, and give the little human a necklace of valuable pearls in return.

So apparently mermaids are good parents.

Where there are mermaids, of course, there are mermen. Mermen are not nearly as widely reported as their female counterparts, but they do exist, and it is generally assumed that they live together under the waves. Mermen, however, are usually described as being hairy and wild-looking, even brutish. Perhaps this explains the fascination that females of the species have with passing sailors.

Of course, tastes in masculine beauty have changed over the years. A modern viewer might see a brawny-chested, bearded merman as quite a “catch.”

Of course, tastes in masculine beauty have changed over the years. A modern viewer might see a brawny-chested, bearded merman as quite a “catch.”

Of course, the most famous of these under-sea creatures is The Little Mermaid. Many people will be surprised to learn that the story is much older than Disney. In fact, it was written by Hans Christian Andersen in 1837. In this story, the Little Mermaid wants, not only to marry the handsome prince, but also to achieve a human soul. Though she trades her tongue and voice to a sea-witch, and endures terrible trials, the prince ultimately marries another.

At this point the Mermaid’s sisters also deal with the sea-witch, and get an enchanted knife that will return their sister to her original state if she kills the prince with it. Yet the Little Mermaid’s love is true. She cannot kill the prince, but throws herself into the sea to drown. Her only consolation is to be changed to sea-foam, and then into an air spirit, which has the chance to win a soul by doing good deeds.

Disney’s version of the story is credited with rejuvenating the studio.

The fact that mermaids are not real has never stopped humans, however. Many, many false mermaids, usually an artificially attached money and fish, have been shown in various places. The most famous, the Fiji Mermaid, was concocted by P.T. Barnum.

But what did sailors see during the Golden Age of Piracy? Or even today, for that matter, because sightings are still reported? The “mermaid” is usually supposed to be a manatee or a dugong. These sea-mammals are known to sit upright in the water, and use their flippers much like hands. Still, it would take a desperate man, or one with a very vivid imagination, to see a beautiful woman in one of these!

But the human imagination is powerful. Without any actual mermaids, people have resorted to creating their own. One such attraction is Weeki Wachee Springs in Florida. Beginning in 1947, a natural spring was turned into an underwater theater, where beautiful young women wearing fabric tails would perform underwater ballet.

The attraction is now a state park and performances are still held, though the performers are now part time, and all are licensed scuba divers.

More recently we’ve seen mermaids in Pirates of the Caribbean. Many people were shocked to see the man-eating version of these beautiful creatures, but the Pirate’s franchise was only honoring all the lore of mermaids – including their ability to walk on land.

Mermaids have many fans, and mermaid clubs are springing up all over. It’s a popular Halloween costume, and fabric tails for kids can be purchased for as little as $5.99. But if you want the real thing – a custom-made silicone tail that will convince your friends and family that you’ve actually turned “fishy” you can have that too.

Of course, these come with a steep price, meaning several thousands of dollars. But for a true mermaid fan, no expense is too great. Nowadays mermaid pools, with ladies (and gentlemen) in this high-end swimwear can be seen at many pirate events, and even at Renaissance Fairs.

I wonder what Columbus would have to say?

Published on September 26, 2016 19:27

September 19, 2016

What did a REAL pirate sound like?

Well, we’ve just about made it through Talk Like a Pirate day, a day that really annoys many of the people who recreate historic pirates (not me, but that’s another story…) Everyone knows the traditional pirate speak… As Cap’n Slappy and Old Chum Bucket, the originators of Talk Like a Pirate Day, inform us “Avast, there me hearties, how you be keeping, an’ why you be ye not speakin’ yer mind on this most glorious holiday! Aaare!”

By this time, most of the folks reading this blog know that all of this started as a result of one man, actor Robert Newton, who played the part of long John Silver in Disney’s first live-action movie, Treasure Island, in 1950. Newton set the standard for pirate talk forever after.

But did you know that all he did was to emphasis his own broad West Country accent? The West Country of England was known for its smugglers and pirates, and so there’s a solid bite of truth in Newton’s original vocal interpretation.

But pirates were so much more! For instance, some historians estimate that as many as 30 percent of pirates were of African origin. So, if you want to shake things up (especially if you have some African heritage yourself) try adopting a West African accent (that being the region of Africa where many of the slavers traded their wares.) Here’s a link to a proud British/African explaining how to imitate his accent. English slave traders, African slaves, plus pirates equals African pirates…

And I wish more folks of African ancestry wanted to play as pirates!

Another accent found in the real pirating world was the Irish. Many Irish, as well as Africans, were shipped to the Caribbean as slaves, and the “Caribbean accent” of today is heavily influenced by the lilt of Ireland. So an Irish accent is perfect for a pirate!

And just in case you doubt the Irish in real pirate speak… Check out this video of some really interesting Irish speakers on the Emerald Isle of Montserrat in the Caribbean.

Of course, some of the most famous pirates, including Olivier Levasseur– The Buzzard – were French. So, if you’re partial to French, you might try out a French accent for your pirate persona. Levasseur was from a so-called good family. So you don’t even have to make an effort to sound “rough.” Being a French pirate would also be a great excuse to swill wine and wear some nice pirate clothes.

Dutch pirates have been used for comedic effect in shows such as Black Sails (coming again this January for its last season on Starz.) But many, many Dutch were pirates. One of the most interesting was Hendrick Quintor, a Black man of Dutch nationality who sailed with Sam Bellamy on the Whydah Galley. I think a Dutch accent on a Black pirate would be sure to be engaging, encouraging members of the public to ask questions and learn about historic pirates.

Or, if you enjoy playing Bad guy pirates, you might want to channel the ghost of Roche Braziliano, whose family emigrated from the Netherlands to Brazil, and who sailed with the notorious Captain Morgan. Either of these men, or any of a hundred others, would have had an accent like this.

The point is that ANY accent can be a pirate accent! Pirates came from nearly every nation, so Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, and even Chinese and Japanese can be pirate accent.

But what about English? You see, the English language has changed a lot in 300 years –even more than most languages. How did native English speakers sound 300 years ago? Well, you might be surprised to learn that they sounded American! It’s a generation, of course, but once English speakers migrated away from the British islands, their language largely stopped changing. (All languages change over time, some more than others.)

Scholars think that the least evolved English in the Americas is the language of the Appalachian Mountains. English-speakers migrated here, and then their language didn’t change. Instead, “English” migrated away, making changes that define a so-called English accent today. So if you want to stir things up, try the “pirate accent” here.

By this time, most of the folks reading this blog know that all of this started as a result of one man, actor Robert Newton, who played the part of long John Silver in Disney’s first live-action movie, Treasure Island, in 1950. Newton set the standard for pirate talk forever after.

But did you know that all he did was to emphasis his own broad West Country accent? The West Country of England was known for its smugglers and pirates, and so there’s a solid bite of truth in Newton’s original vocal interpretation.

But pirates were so much more! For instance, some historians estimate that as many as 30 percent of pirates were of African origin. So, if you want to shake things up (especially if you have some African heritage yourself) try adopting a West African accent (that being the region of Africa where many of the slavers traded their wares.) Here’s a link to a proud British/African explaining how to imitate his accent. English slave traders, African slaves, plus pirates equals African pirates…

And I wish more folks of African ancestry wanted to play as pirates!

Another accent found in the real pirating world was the Irish. Many Irish, as well as Africans, were shipped to the Caribbean as slaves, and the “Caribbean accent” of today is heavily influenced by the lilt of Ireland. So an Irish accent is perfect for a pirate!

And just in case you doubt the Irish in real pirate speak… Check out this video of some really interesting Irish speakers on the Emerald Isle of Montserrat in the Caribbean.

Of course, some of the most famous pirates, including Olivier Levasseur– The Buzzard – were French. So, if you’re partial to French, you might try out a French accent for your pirate persona. Levasseur was from a so-called good family. So you don’t even have to make an effort to sound “rough.” Being a French pirate would also be a great excuse to swill wine and wear some nice pirate clothes.

Dutch pirates have been used for comedic effect in shows such as Black Sails (coming again this January for its last season on Starz.) But many, many Dutch were pirates. One of the most interesting was Hendrick Quintor, a Black man of Dutch nationality who sailed with Sam Bellamy on the Whydah Galley. I think a Dutch accent on a Black pirate would be sure to be engaging, encouraging members of the public to ask questions and learn about historic pirates.

Or, if you enjoy playing Bad guy pirates, you might want to channel the ghost of Roche Braziliano, whose family emigrated from the Netherlands to Brazil, and who sailed with the notorious Captain Morgan. Either of these men, or any of a hundred others, would have had an accent like this.

The point is that ANY accent can be a pirate accent! Pirates came from nearly every nation, so Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, and even Chinese and Japanese can be pirate accent.

But what about English? You see, the English language has changed a lot in 300 years –even more than most languages. How did native English speakers sound 300 years ago? Well, you might be surprised to learn that they sounded American! It’s a generation, of course, but once English speakers migrated away from the British islands, their language largely stopped changing. (All languages change over time, some more than others.)

Scholars think that the least evolved English in the Americas is the language of the Appalachian Mountains. English-speakers migrated here, and then their language didn’t change. Instead, “English” migrated away, making changes that define a so-called English accent today. So if you want to stir things up, try the “pirate accent” here.

Published on September 19, 2016 18:36

September 12, 2016

A Pirate’s Letter Home

Sometimes I wonder about whether pirates ever wrote letters home. It’s a hard topic to research, since I have never found an example of a pirate’s letter to a private individual. Some open letters by pirates have been published. We’ll look at those at a later date.

What was mail like at about 1700? Very, very different than it is now, that’s for sure.

For one thing, right now most of us have a device in our pockets that allows us to speak to nearly anyone on the planet. We can use it to send text messages, to send emails, to send pictures and videos. Communication was very different 300 years ago.

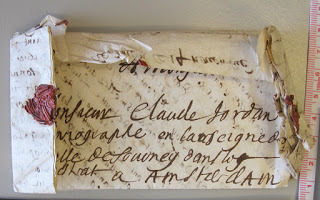

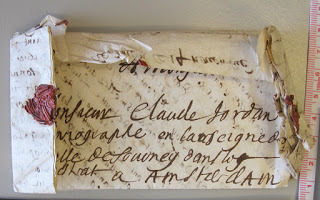

People communicated by hand-written letter. There were no envelopes, so once the letter was written, the paper was folded up to protect the writing, and the result was held shut with a blob of wax. (Despite all the celebration of “wax seals” in movies, and modern sale of the things in card stores, only official documents and those written by royalty or the very rich were sealed with much more than a blob of wax.)

The wax was used because of the primitive nature of glue at the time – glue was rare, and glue that worked might destroy the paper it was attached to. Some letters were sewn shut.

Here's a video of one way to write and seal a letter.

As well as no envelopes, there were also no stamps. (The first postage stamp, called the Penny Black, was introduced in 1840 in Great Britain.) In 1700, the fee to have a letter delivered was paid by the person receiving it.

Why? For one thing, the postal system was not well organized. Letters in England were carried by post boys on horseback. Being a post boy was not a career, merely and occupation for a young man with some tolerance for traveling and having adventures. Since these young men were paid when they delivered the letters there was some chance that the young man would show up with the mail. There was no set schedule for deliveries. The post boys rode when there was mail, and went where the mail needed to be taken. No daily deliveries!

The original mail service had been set up by Henry VIII, and it relied on a set of post-roads, roads that were maintained by the government. (Few roads were.) These roads were better than most, but were still unpaved. Muddy, meandering, surrounded by robbers, these roads rarely let travelers exceed 3 miles per hour. Post boys, noted by their red jackets, were famous for taking time off to fish, drink beer and flirt with women, or simply take a nap on roadside grass.

Postmasters were usually innkeepers, since part of the postmaster’s job was to keep at least three horses on hand for the use of post riders. Postmasters were also the ones who recruited post boys, which may have explained why so many of these riders were lackadaisical in their duties. Being a post master cemented an innkeeper’s place in the community as a source of news and gossip.

The limits of actual service were very small as well. Mostly, it was for areas within 100 miles of London. (Mail traveling from London to Bath, 115 miles away, took 3 days by regular post, 2 days express.) Postage within the city limits of London cost a penny in 1660, half a day’s wages for many people. Postage outside the city was a shilling, or a week’s wages.

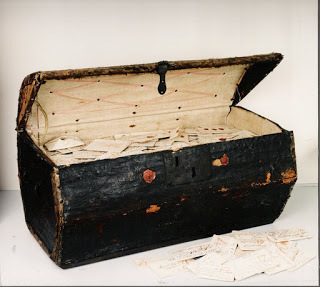

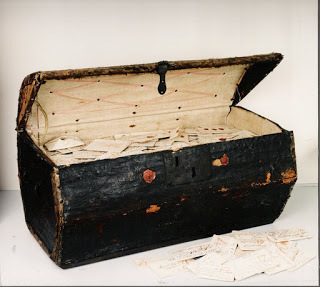

Many letters were never delivered. The red-coated post boys were targeted by robbers, who cut the post bags off the saddle while post boys stopped for a drink. Letters were also sometimes lost or simply abandoned. In November of 2015, a trunk full of letters was found in the back of a historic postmaster’s trunk in the Netherlands. Over 2,600 undelivered letters were discovered.

Modern academics are not opening the letters – they rely on X-rays to read the contents without disturbing the seals or the aging paper. But the original postmaster does not seem to have been so delicate. Many of the letters were opened.

They reveal the voices of a wide range of people, from the barely literate, to scholars with beautiful handwriting. They tell the stories of academic achievement, financial problems, and love. One told the story of an opera singer who had left her lover, and now wanted him to take her back (and pay her passage home to him.)

The trunk contained mail from France, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands. Some of the letters were written in Latin.

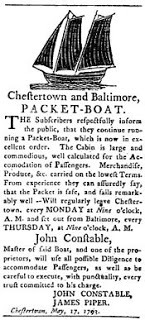

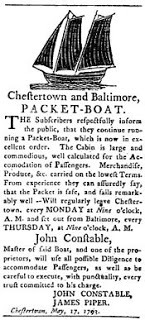

Mail moved officially between countries on vessels called Packet Ships (a term for any ship carrying an official packet of mail in addition to its other cargo.) During the Golden Age of Piracy, no regular shipping routes were in use, so the shipping of mail was very irregular.

Rich people often send mail by private carrier in order to circumvent all this, and poorer folk sent letters along with kind strangers who happened to be traveling in the right direction. Since post roads were often used by general travelers, (despite the fact that they were bad, they were better than other roads) it would not have been much of a chore to drop a letter off with an innkeeper/postmaster. Then, another traveler might carry it along. Or not. You never quite knew.

What was mail like at about 1700? Very, very different than it is now, that’s for sure.

For one thing, right now most of us have a device in our pockets that allows us to speak to nearly anyone on the planet. We can use it to send text messages, to send emails, to send pictures and videos. Communication was very different 300 years ago.

People communicated by hand-written letter. There were no envelopes, so once the letter was written, the paper was folded up to protect the writing, and the result was held shut with a blob of wax. (Despite all the celebration of “wax seals” in movies, and modern sale of the things in card stores, only official documents and those written by royalty or the very rich were sealed with much more than a blob of wax.)

The wax was used because of the primitive nature of glue at the time – glue was rare, and glue that worked might destroy the paper it was attached to. Some letters were sewn shut.

Here's a video of one way to write and seal a letter.

As well as no envelopes, there were also no stamps. (The first postage stamp, called the Penny Black, was introduced in 1840 in Great Britain.) In 1700, the fee to have a letter delivered was paid by the person receiving it.

Why? For one thing, the postal system was not well organized. Letters in England were carried by post boys on horseback. Being a post boy was not a career, merely and occupation for a young man with some tolerance for traveling and having adventures. Since these young men were paid when they delivered the letters there was some chance that the young man would show up with the mail. There was no set schedule for deliveries. The post boys rode when there was mail, and went where the mail needed to be taken. No daily deliveries!

The original mail service had been set up by Henry VIII, and it relied on a set of post-roads, roads that were maintained by the government. (Few roads were.) These roads were better than most, but were still unpaved. Muddy, meandering, surrounded by robbers, these roads rarely let travelers exceed 3 miles per hour. Post boys, noted by their red jackets, were famous for taking time off to fish, drink beer and flirt with women, or simply take a nap on roadside grass.

Postmasters were usually innkeepers, since part of the postmaster’s job was to keep at least three horses on hand for the use of post riders. Postmasters were also the ones who recruited post boys, which may have explained why so many of these riders were lackadaisical in their duties. Being a post master cemented an innkeeper’s place in the community as a source of news and gossip.

The limits of actual service were very small as well. Mostly, it was for areas within 100 miles of London. (Mail traveling from London to Bath, 115 miles away, took 3 days by regular post, 2 days express.) Postage within the city limits of London cost a penny in 1660, half a day’s wages for many people. Postage outside the city was a shilling, or a week’s wages.

Many letters were never delivered. The red-coated post boys were targeted by robbers, who cut the post bags off the saddle while post boys stopped for a drink. Letters were also sometimes lost or simply abandoned. In November of 2015, a trunk full of letters was found in the back of a historic postmaster’s trunk in the Netherlands. Over 2,600 undelivered letters were discovered.

Modern academics are not opening the letters – they rely on X-rays to read the contents without disturbing the seals or the aging paper. But the original postmaster does not seem to have been so delicate. Many of the letters were opened.

They reveal the voices of a wide range of people, from the barely literate, to scholars with beautiful handwriting. They tell the stories of academic achievement, financial problems, and love. One told the story of an opera singer who had left her lover, and now wanted him to take her back (and pay her passage home to him.)

The trunk contained mail from France, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands. Some of the letters were written in Latin.

Mail moved officially between countries on vessels called Packet Ships (a term for any ship carrying an official packet of mail in addition to its other cargo.) During the Golden Age of Piracy, no regular shipping routes were in use, so the shipping of mail was very irregular.

Rich people often send mail by private carrier in order to circumvent all this, and poorer folk sent letters along with kind strangers who happened to be traveling in the right direction. Since post roads were often used by general travelers, (despite the fact that they were bad, they were better than other roads) it would not have been much of a chore to drop a letter off with an innkeeper/postmaster. Then, another traveler might carry it along. Or not. You never quite knew.

Published on September 12, 2016 12:03

September 5, 2016

Pirate Phrases… Real or Hollywood?

With Talk Like a Pirate Day right around the corner, many of us are brushing up on our pirate phrases and language. Here’s a fun list of common sayings. Can you tell if they’re fictional or the Real Deal?

Espy, descry: To see something. Usually when searching the horizon for a sail. Authentic.

Me hearties!: During the Golden Age of Piracy the phrase was “My hearts!” as in “Friends of my heart.” “Heart” was also a slang term for a “stout heart,” and thus for a sailor. By the late 18th century the pronunciation was often rendered as “My hearties,” and in the 19th as “Me hearties.” A little authentic, a little from Hollywood, so your answer is right no matter what you guessed.

Pluck a crow: To pick a fight. Authentic.

Catch a Tartar: Pick a fight with someone stronger than yourself. The reputation of Genghis Khan and his so-called Tartars was still strong in the 18thcentury. Authentic.

Shiver me timbers: Timbers are the wooden parts that make up the ship’s hull and support the decks and, they did shiver, meaning they splintered and shattered, as in “shivered to pieces.” This was most likely to happen in a ship that has run aground. However, the phrase was not used by pirates. It was first popularized by novelist and naval officer Francis Marryat (famous for his semi-autobiographical novel Mr. Midshipmen Easy) in the early 19th century. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Long John Silver made it famous in Treasure Island. Though this period is often thought of in connection with pirates, it was in fact 100 years later. Fiction.

Dead man’s chest: The phrase became famous through Treasure Island and no one is quite sure what Stevenson meant. “Dead Man’s Chest” is the English translation of caja de muerto, or coffin. Caja de Muerto is the name of an island off Puerto Rico, so-named because it resembles a coffin. Fun to know, but real pirates probably never talked about it.

Show your heels: To run away. Authentic. Also – having light heels meant likely to run away.

Ballast her well: Ballast was the weight put into the bottom of a ship which causes it to stay upright in the water. This phrase was also use to request that a bartender pour a tankard completely full. Authentic.

Yo ho ho: Though “Yo ho,” was a chant used to help a group work together when hauling or heaving. It was popularized in Treasure Island. Fiction.

Piece-of-eight: a Spanish dollar, worth eight reals or royals, and the currency upon which the U.S. dollar was founded. A silver coin that could be divided into eight pieces. Authentic.

Plain-dealer: one who speaks plainly Many sailors, seamen and pirates prided themselves on speaking plainly and honestly. They felt that this was a contrast to landsmen, who often lied and acted dishonestly. Authentic.

Thundering fellow: a loud, shouting person with a deep voice, often the bosun. Authentic.

Arr! A common phrase on the West Country of England, exaggerated by Robert Newton who played both Long John Silver and Blackbeard in the 1950s. Newton exaggerated his own West Country accent, as in “Arr, yer a good ‘un, Jim,” which was his pronunciation of “Aw, you’re a good one, Jim.” Fiction.

Linguister: a translator, one who speaks other languages. Authentic.

Jackanapes: A cocky or impudent person. From the term “Jack, from Naples.” Monkeys were often carried by traveling entertainers, many of whom came from Italy, or pretended to. The term may have been applied to sailors a sailor due to their ability to climb aloft. Sailors, like monkeys, were also known for being impudent. Authentic.

Smart as paint: Although this phrase may sound like the modern-day “smart as a cheese sandwich,” it was a genuine complement. “Smart” is a term often meaning well-dressed or fashionably decorated. Ships were painted to make them look “smart” and so by saying that a person was “smart as paint,” one was comparing him to the origin of a ship’s “smartness.” But it’s entirely fictional, invented by Robert Lewis Stevenson for Treasure Island.

Espy, descry: To see something. Usually when searching the horizon for a sail. Authentic.

Me hearties!: During the Golden Age of Piracy the phrase was “My hearts!” as in “Friends of my heart.” “Heart” was also a slang term for a “stout heart,” and thus for a sailor. By the late 18th century the pronunciation was often rendered as “My hearties,” and in the 19th as “Me hearties.” A little authentic, a little from Hollywood, so your answer is right no matter what you guessed.

Pluck a crow: To pick a fight. Authentic.

Catch a Tartar: Pick a fight with someone stronger than yourself. The reputation of Genghis Khan and his so-called Tartars was still strong in the 18thcentury. Authentic.

Shiver me timbers: Timbers are the wooden parts that make up the ship’s hull and support the decks and, they did shiver, meaning they splintered and shattered, as in “shivered to pieces.” This was most likely to happen in a ship that has run aground. However, the phrase was not used by pirates. It was first popularized by novelist and naval officer Francis Marryat (famous for his semi-autobiographical novel Mr. Midshipmen Easy) in the early 19th century. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Long John Silver made it famous in Treasure Island. Though this period is often thought of in connection with pirates, it was in fact 100 years later. Fiction.

Dead man’s chest: The phrase became famous through Treasure Island and no one is quite sure what Stevenson meant. “Dead Man’s Chest” is the English translation of caja de muerto, or coffin. Caja de Muerto is the name of an island off Puerto Rico, so-named because it resembles a coffin. Fun to know, but real pirates probably never talked about it.

Show your heels: To run away. Authentic. Also – having light heels meant likely to run away.

Ballast her well: Ballast was the weight put into the bottom of a ship which causes it to stay upright in the water. This phrase was also use to request that a bartender pour a tankard completely full. Authentic.

Yo ho ho: Though “Yo ho,” was a chant used to help a group work together when hauling or heaving. It was popularized in Treasure Island. Fiction.

Piece-of-eight: a Spanish dollar, worth eight reals or royals, and the currency upon which the U.S. dollar was founded. A silver coin that could be divided into eight pieces. Authentic.

Plain-dealer: one who speaks plainly Many sailors, seamen and pirates prided themselves on speaking plainly and honestly. They felt that this was a contrast to landsmen, who often lied and acted dishonestly. Authentic.

Thundering fellow: a loud, shouting person with a deep voice, often the bosun. Authentic.

Arr! A common phrase on the West Country of England, exaggerated by Robert Newton who played both Long John Silver and Blackbeard in the 1950s. Newton exaggerated his own West Country accent, as in “Arr, yer a good ‘un, Jim,” which was his pronunciation of “Aw, you’re a good one, Jim.” Fiction.

Linguister: a translator, one who speaks other languages. Authentic.

Jackanapes: A cocky or impudent person. From the term “Jack, from Naples.” Monkeys were often carried by traveling entertainers, many of whom came from Italy, or pretended to. The term may have been applied to sailors a sailor due to their ability to climb aloft. Sailors, like monkeys, were also known for being impudent. Authentic.

Smart as paint: Although this phrase may sound like the modern-day “smart as a cheese sandwich,” it was a genuine complement. “Smart” is a term often meaning well-dressed or fashionably decorated. Ships were painted to make them look “smart” and so by saying that a person was “smart as paint,” one was comparing him to the origin of a ship’s “smartness.” But it’s entirely fictional, invented by Robert Lewis Stevenson for Treasure Island.

Published on September 05, 2016 19:01

August 29, 2016

Michiana Ren Faire

Your first question would be “Why are we reviewing a ren faire?” and tnhe second would be “What’s a Michiana, anyway?” Both wise questions, and they will be answered here.

This particular faire is notable for pirates because it is divided into different “realms” for the pleasure of visitors. Since ren fairs have largely ceased to be entirely Renaissance themed (at least in the Midwest) and have become places where costume geeks, Doctor Who fans, history buffs and pop culture fans gather to show off their strange clothes and be strange together, it makes sense to divide the area into sections that appeal to different people.

Michiana’s sections were Renaissance, Fairytales, Pirates, and Vikings, and therefore the event is of interest to our readers.

As to what a Michiana is, it is the region containing southwestern Michigan and northern Indiana, centered on the city of Mishawka. (To those not familiar with the Midwestern United States, the place name is based on terms used by the native tribes.)

Mishawaka is a moderately sized city in an area where there is not much else. A beautiful, thriving community, it offers among other things beautiful Kamm Island Park, a beautiful natural area with wide walkways and lovely trees, located on Kamm Island in the St Joseph River.

The site provided an ideal location, offering limited access and providing performers and vendors with comfortable locations and beautiful backgrounds. An estimated two thousand people enjoyed the event this year. (2016)

The Pirate area was located between the Vikings, and area dominated by a recreated Viking settlement which showed off Viking crafts and lifestyle. Between the two were belly dancers. Were these entertainers historically accurate? Not really. But everyone agrees that belly dancers and pirates are two great things that go great together, and with an abundance of dancers, the Pirates were willing to share with their Viking brethren.

The Pirate area was definitely dominated by fantasy pirates. Booths hawked broadswords and katanas in addition to cutlasses, and performers were as likely to offer “Sloop John B” (famously recorded by the Beach Boys in 1966) as traditional sea shanties.

But it was a happy crowd. Strolling pirates were dressed in tricorn hats and striped pants, garb no inconsistent with real 18th century buccaneers. Calls of “Rum!” and flirtatious looks were common. One gentleman of fortune, calling himself “Captain Duckworth” offered to deliver extravagant complements to anyone on the grounds for a small fee.

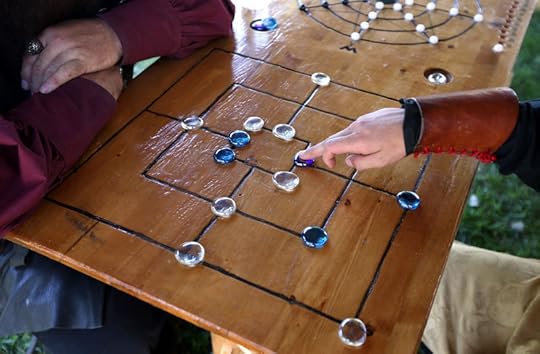

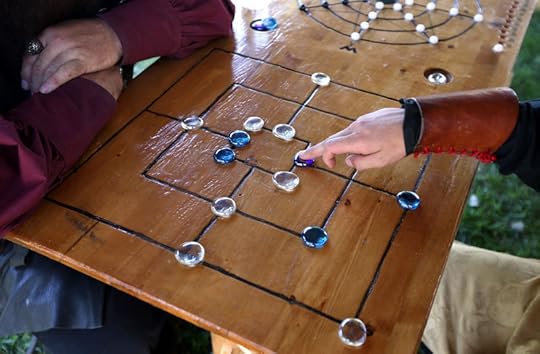

Pirate offered sword fighting demonstrations, showed (with a huge amount of noise) how black power guns operated) and offered a large number of 18th century games in the games tent. I was there too, telling true pirate tales, and offering autographed copies of my books for sale. Non-fiction was definitely the item of the day, with my young-adult books, Pirates of the Golden Age outselling fiction. But Gentlemen and Fortune, my thrilling tale of Scarlet MacGrath, female pirate captain with attitude, came in a close second.

[image error]

Probably the most fun for me, a performer and vendor, was the large number of folks who came through the area in costume. It’s always a pleasure to see visitors enjoying themselves, and when folks take the time to dress up it means they’re in the right mood to have a good time.

In other areas, the Middle Ages and Renaissance were recreated with authentic encampments, dancing and music. And in the Fairytale section, storytelling was king, while folk in fairy costumes sold hand-made goods and entertained children with giggles and games.

This was also the place to find the Fair’s most amazing crafts, from one-of-a-kind jewelry to amazing hand stitched capes. The Fairytale section was colorful and fun.

One of the things I liked the least was the amount of trouble given to the Ren Faire by the Powers That Be. The Mayor of Mishawaka came by the let the organizers know that he didn’t like the festival, and several locals showed up with some king of anger leveled at the “strange people” who were dressed up and having a good time. I should note here that Faire-goers were a well-behaved crowd, and while a local watering hole had organized an on-site tavern, I saw not one person misbehaving or causing trouble.

Perhaps it’s a good thing that the Michiana Ren Faire is now looking for a new home. Kamm Island has been a great location, but with the local city government hostile to anyone doing things “differently” the Michiana Ren Faire will be better served by finding a different location. Fortunately funding is adequate, and the core of this wonderful festival’s organizers remain optimistic and full of energy.

I’ll be looking forward to the next Michiana Ren Faire, wherever it is.

This particular faire is notable for pirates because it is divided into different “realms” for the pleasure of visitors. Since ren fairs have largely ceased to be entirely Renaissance themed (at least in the Midwest) and have become places where costume geeks, Doctor Who fans, history buffs and pop culture fans gather to show off their strange clothes and be strange together, it makes sense to divide the area into sections that appeal to different people.

Michiana’s sections were Renaissance, Fairytales, Pirates, and Vikings, and therefore the event is of interest to our readers.

As to what a Michiana is, it is the region containing southwestern Michigan and northern Indiana, centered on the city of Mishawka. (To those not familiar with the Midwestern United States, the place name is based on terms used by the native tribes.)

Mishawaka is a moderately sized city in an area where there is not much else. A beautiful, thriving community, it offers among other things beautiful Kamm Island Park, a beautiful natural area with wide walkways and lovely trees, located on Kamm Island in the St Joseph River.

The site provided an ideal location, offering limited access and providing performers and vendors with comfortable locations and beautiful backgrounds. An estimated two thousand people enjoyed the event this year. (2016)

The Pirate area was located between the Vikings, and area dominated by a recreated Viking settlement which showed off Viking crafts and lifestyle. Between the two were belly dancers. Were these entertainers historically accurate? Not really. But everyone agrees that belly dancers and pirates are two great things that go great together, and with an abundance of dancers, the Pirates were willing to share with their Viking brethren.

The Pirate area was definitely dominated by fantasy pirates. Booths hawked broadswords and katanas in addition to cutlasses, and performers were as likely to offer “Sloop John B” (famously recorded by the Beach Boys in 1966) as traditional sea shanties.

But it was a happy crowd. Strolling pirates were dressed in tricorn hats and striped pants, garb no inconsistent with real 18th century buccaneers. Calls of “Rum!” and flirtatious looks were common. One gentleman of fortune, calling himself “Captain Duckworth” offered to deliver extravagant complements to anyone on the grounds for a small fee.

Pirate offered sword fighting demonstrations, showed (with a huge amount of noise) how black power guns operated) and offered a large number of 18th century games in the games tent. I was there too, telling true pirate tales, and offering autographed copies of my books for sale. Non-fiction was definitely the item of the day, with my young-adult books, Pirates of the Golden Age outselling fiction. But Gentlemen and Fortune, my thrilling tale of Scarlet MacGrath, female pirate captain with attitude, came in a close second.

[image error]

Probably the most fun for me, a performer and vendor, was the large number of folks who came through the area in costume. It’s always a pleasure to see visitors enjoying themselves, and when folks take the time to dress up it means they’re in the right mood to have a good time.

In other areas, the Middle Ages and Renaissance were recreated with authentic encampments, dancing and music. And in the Fairytale section, storytelling was king, while folk in fairy costumes sold hand-made goods and entertained children with giggles and games.

This was also the place to find the Fair’s most amazing crafts, from one-of-a-kind jewelry to amazing hand stitched capes. The Fairytale section was colorful and fun.

One of the things I liked the least was the amount of trouble given to the Ren Faire by the Powers That Be. The Mayor of Mishawaka came by the let the organizers know that he didn’t like the festival, and several locals showed up with some king of anger leveled at the “strange people” who were dressed up and having a good time. I should note here that Faire-goers were a well-behaved crowd, and while a local watering hole had organized an on-site tavern, I saw not one person misbehaving or causing trouble.

Perhaps it’s a good thing that the Michiana Ren Faire is now looking for a new home. Kamm Island has been a great location, but with the local city government hostile to anyone doing things “differently” the Michiana Ren Faire will be better served by finding a different location. Fortunately funding is adequate, and the core of this wonderful festival’s organizers remain optimistic and full of energy.

I’ll be looking forward to the next Michiana Ren Faire, wherever it is.

Published on August 29, 2016 21:50

August 15, 2016

Belize and the Bucaneers

I first heard of the nation of Belize while reading the introduction to Colin Woodard’s excellent book, The Republic of Pirates. In it, Woodard states that he decided to write the book while vacationing in Belize. He also notes that the tiny nation is one of the few places on earth where the original accent of 18th century pirates lingers on.