T.S. Rhodes's Blog, page 4

July 24, 2017

How to Become a Pirate

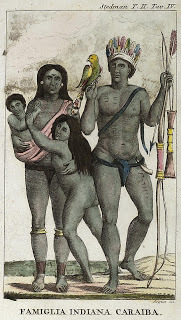

People often wonder how pirates recruited. Did they kidnap people and force them to join the crew? Did the worst of the worst of rapist s and murders simply go down to their local seaport and sign on? Were children brought up to be pirates?

A little of each is true.

Maybe Not Quite Like This

Maybe Not Quite Like ThisIn the past – as recently as the 1500’s in some places, as recently as yesterday in others, children were born to a pirating life. Probably the most famous of these pirates is Grace O’Malley, the Pirate Queen of Ireland. Grace inherited her father’s pirate fleet, after a youth spent on shipboard learning the trade. When pirating was a family affair, a tradition of taking ships out to robe the neighbors, or the inhabitants of the next country, people were indeed born into the pirating life.

For the most part, this tradition ended with the growth of corporations and corporate shipping. Raiding between clans or nations was just that… raiding. But attacks on powerful, rich, international entities like corporations brought legal reprisals.

At the beginning or piracy’s Golden Age, a large number of young men who had been employed by their national navies suddenly found themselves out of work. Often this included entire crews, from officers on down. Common sailors often followed a captain who turned to piracy.

Ben Hornigold was one such captain. It seems certain that Hornigold was a good leader, beloved by his crews and skilled at running a ship. When the European wars ran out, Hornigold continued to do what he considered to be his duty as an Englishman, robbing French and Spanish ships. As a navy captain at the time, this was legal, even praiseworthy behavior. But without the support of a national war, actions that he had been carrying on for perhaps a decade suddenly became illegal.

Hornigold was a natural teacher, and he taught men to be pirates. His most notable student was no less than Blackbeard himself. But scholars charting the “linage” of Hornigold-taught pirate captains believe that 1,500 individual pirates owe their occupation to the “school for pirates” that Hornigold ran as he sailed through the Caribbean.

Some pirates joined the trade for revenge. The Lioness of Brittany, Jeanne de Clisson, vowed revenge when her husband was accused of treason and beheaded by the King of France. She sold her lands to by three war ships, and set about a career in piracy, being sure to behead any Frenchmen of the noble classes who had the misfortune to be captured by her black-hulled ships.

Jeanne was of a time period (the mid 1300’s) and a class (nobility) which allowed her to retire quietly once her pirating career was over. Most pirates who became Gentlemen of Fortune came from a much lower class.

Common sailors were often badly mistreated by their captains and officers. Food was often far worse that it had to be, beatings were common, and punishments could run to the sadistic, as sailors might be hung up by their wrists, deprived of rest and sleep, and sometimes even killed. This sort of thing led to rage that led crews to disregard their own futures in order to get payback. Some crew rose against their officers due to some initiating factor. This might become a mutiny, or might lead to full-blown piracy.

The most common way that a person became a pirate was to be robbed by pirates. Once they captured a ship, pirates took opportunity to recruit from among the ranks of the captured sailors. Offers of money, better food, more liquor, or a chance to get back at people who had abused them led many men to sign the papers that made them pirates. It should be noted that, by far, the most popular name for a pirate ship was “Revenge.”

But it was a frightening business to leave everything one knew to take up a life of crime that might end in hanging. Some sailors approached pirates on the quiet, asking for a show of being kidnapped, so they could later deny that they had joined the brigands willingly. The pirates usually complied.

Some folk were actually kidnapped, but not many. Skilled workers, who were paid more and treated better on merchant ships, were not so anxious to take up with sea-thieves. Sam Bellamy is known to have forced carpenters to join his crew, though he did make an effort to take single men, who were not married and presumable had few family ties.

But the reasons for becoming pirates, and the methods used to achieve this goal, were as varied as the people who had them.

Stede Bonnet, a rich man from a rich family, paid to have a pirate ship built and hired a crew. His reason is said to be that he didn’t like living with his wife.

The cross-dressing former soldier Mary Reed seems to have gone to the pirate island of New Providence with the intention of simply being herself. In a world where women were confined to the home, Mary had a unique solution to her desire for freedom.

Many African slaves who had been captured by pirates were freed and joined their liberators. Hampered by lack of experience as sailors, few of these black pirates became famous, but they made up large percentages of some pirate crews.

The nine-year-old boy, John King, kicked his mother in the shins and demanded that Sam Bellamy’s crew allow him to join. We don’t really know what prompted the child, but one report states that “the boy’s father didn’t like him.”

The fact is that, if you wanted to be a pirate, it wasn’t that hard to find a way.

Published on July 24, 2017 21:13

July 17, 2017

An Ounce of Lead

Pirates and lead go together in this infamous phrase. “And ounce of lead” meant a bullet, or, as it was called at the time, a shot. Whatever it was called, it was probably close to 62 caliber by modern calculations, and when it hit, it hurt.

But why were the projectiles for 18the century muskets and pistols made out of lead?

For one thing, lead is a common metal. It is one of the earliest known elements, dating back to pre-history. And it has a low melting point, making it easy to extract from ore and to work after it is extracted. Lead does not oxidize (rust) easily, so it is fairly easy to keep around.

In addition, when people began using firearms to fling small objects at each other, it was quickly discovered that lead projectiles do a lot of damage to the human body. A lead projectile flattens as soon as it meets resistance, and it flattening, it spreads out. A 1” round shot going into the body makes a 1” hole. Coming out, it may make a 4” hole. Or it may break to pieces and spread out, doing even more damage.

Ancient Roman plumbing

Ancient Roman plumbing

Lead has many uses in the early 18th century. Dating back to early Roman times, it had been used for water pipes. That’s right, just like the ones in Flint Michigan. (As of this date, Flint still does not have drinkable water.) In fact, Roman word for lead – plumbum – is the origin of our modern word, plumbing. What happened to the people who drank water carried in these pipes?

It depended. As noted above, lead doesn’t usually react with water. But if the water is even a little acidic, it can pick up molecules of lead and carry them along. This can cause lead poisoning. Some scholars believe that lead poisoning of the general population contributed to the fall of Rome, while others are skeptical.

The problem is that lead is very easy to get and easy to work with. It can be melted over a campfire (at 621 degrees Fahrenheit) which made it easy to cast. Lead was used to make the type which was set into plates to print books, posters and newspapers. People who worked with it often dies of lead poisoning.

From Roman times onwards, folks who enjoyed drinking wine noticed that wine stored in lead containers tasted better than wine stored other ways. This is because lead reacts with alcohol to produce lead acetate (Pb(CH3COO)2) also called sugar of lead. This substance sweetened the wine.

Unfortunately, it also poisoned the drinker, if he enjoyed enough of it. Unfortunately, no one quite understood why. The Roman Catholic Church forbid the use of wine containing sugar of lead in communion, and wine bottlers who used it were viewed with suspicion, but the use of lead to sweeten wine remained in practice until long after the age of pirates.

Lead was also used for a variety of other purposes. White lead paint was applied to the underside of ships to discourage the growth of seaweed and discourage parasites such as shipworm from damaging the wooden structure. Guess what? These things didn’t like the poisonous lead.

Sheet lead was also used as we might use plastic today. For example, when the flint of a flintlock pistol was clamped into the gun, it was often wrapped in a small piece of sheet lead, which helped the jaws of the clamp to grip if firmly. These pieces of flint were often taken out for sharpening (a sharp flint makes a more reliable spark) and were also often replaced. The men who did this work would never have thought to wear gloves. But today we know that touching lead with bare skin can cause the metal to be absorbed through the skin.

Notice the sheet lead wrapping the base of the flint

Notice the sheet lead wrapping the base of the flint

Another way that pirates encountered lead was casting shot for their pistols and muskets. Some shot was shipped – and could be stolen – as ready-made round balls. But it the size didn’t fit the available guns, or if the only lead available was solid blocks, the pirates would melt it down (something easy to do, even on a ship) and cast their own projectiles.

Equipment to cast lead is simple – an iron pot, a fire, and a mold. The most simple mold-release agent was simple carbon from a smoking candle, and the shot could be hardened by dropping the recently cast spheres into water.

Shot casting kit

Shot casting kit

How-too instructions are currently available online, if you want to turn old lead pipes into anything from bullets to collectible figurines. But beware! You’ll also be told to wear breathing protection, and long sleeves, and to never get the fumes into your eyes. In fact, it’s not even recommended that you bring any of your lead-casting paraphilia into your home after you’ve used it. Don’t even put the clothes you wear while doing it next to clothing you use for any other purpose! Today we take the dangers of lead poisoning seriously.

It’s likely that many working-class pirates suffered from some level of lead poisoning. Symptoms can vary widely from individual to individual, and can start with relatively low levels of exposure, or at higher levels.

The symptoms – among which are muscle pain, abdominal pain, problems sleeping, depression, and reduced libido, are much like the symptoms of hard work and excessive alcohol. Pirates were also known to have hallucinations and personality changes, also easily attributed to drink. Damaged gums could be blamed on scurvy. Lead poisoning might have plagued many a pirate crew, and it would be hard to tell for sure, without modern blood testing.

Did lead poisoning contribute to the downfall of the pirates? One of the hallmarks of lead poisoning is also decrease in cognitive abilities. This may explain the sometimes vast differences between the pirate deck-hand, a fellow who prided himself in speaking and living by simple truths, and the wily and devious pirate captains, who, with their elevated status probably didn’t cast round shot or paint the boat.

Is it true? I don’t know, but it’s something to think about. One more bit of trivial from the age of pirates.

But why were the projectiles for 18the century muskets and pistols made out of lead?

For one thing, lead is a common metal. It is one of the earliest known elements, dating back to pre-history. And it has a low melting point, making it easy to extract from ore and to work after it is extracted. Lead does not oxidize (rust) easily, so it is fairly easy to keep around.

In addition, when people began using firearms to fling small objects at each other, it was quickly discovered that lead projectiles do a lot of damage to the human body. A lead projectile flattens as soon as it meets resistance, and it flattening, it spreads out. A 1” round shot going into the body makes a 1” hole. Coming out, it may make a 4” hole. Or it may break to pieces and spread out, doing even more damage.

Ancient Roman plumbing

Ancient Roman plumbingLead has many uses in the early 18th century. Dating back to early Roman times, it had been used for water pipes. That’s right, just like the ones in Flint Michigan. (As of this date, Flint still does not have drinkable water.) In fact, Roman word for lead – plumbum – is the origin of our modern word, plumbing. What happened to the people who drank water carried in these pipes?

It depended. As noted above, lead doesn’t usually react with water. But if the water is even a little acidic, it can pick up molecules of lead and carry them along. This can cause lead poisoning. Some scholars believe that lead poisoning of the general population contributed to the fall of Rome, while others are skeptical.

The problem is that lead is very easy to get and easy to work with. It can be melted over a campfire (at 621 degrees Fahrenheit) which made it easy to cast. Lead was used to make the type which was set into plates to print books, posters and newspapers. People who worked with it often dies of lead poisoning.

From Roman times onwards, folks who enjoyed drinking wine noticed that wine stored in lead containers tasted better than wine stored other ways. This is because lead reacts with alcohol to produce lead acetate (Pb(CH3COO)2) also called sugar of lead. This substance sweetened the wine.

Unfortunately, it also poisoned the drinker, if he enjoyed enough of it. Unfortunately, no one quite understood why. The Roman Catholic Church forbid the use of wine containing sugar of lead in communion, and wine bottlers who used it were viewed with suspicion, but the use of lead to sweeten wine remained in practice until long after the age of pirates.

Lead was also used for a variety of other purposes. White lead paint was applied to the underside of ships to discourage the growth of seaweed and discourage parasites such as shipworm from damaging the wooden structure. Guess what? These things didn’t like the poisonous lead.

Sheet lead was also used as we might use plastic today. For example, when the flint of a flintlock pistol was clamped into the gun, it was often wrapped in a small piece of sheet lead, which helped the jaws of the clamp to grip if firmly. These pieces of flint were often taken out for sharpening (a sharp flint makes a more reliable spark) and were also often replaced. The men who did this work would never have thought to wear gloves. But today we know that touching lead with bare skin can cause the metal to be absorbed through the skin.

Notice the sheet lead wrapping the base of the flint

Notice the sheet lead wrapping the base of the flintAnother way that pirates encountered lead was casting shot for their pistols and muskets. Some shot was shipped – and could be stolen – as ready-made round balls. But it the size didn’t fit the available guns, or if the only lead available was solid blocks, the pirates would melt it down (something easy to do, even on a ship) and cast their own projectiles.

Equipment to cast lead is simple – an iron pot, a fire, and a mold. The most simple mold-release agent was simple carbon from a smoking candle, and the shot could be hardened by dropping the recently cast spheres into water.

Shot casting kit

Shot casting kitHow-too instructions are currently available online, if you want to turn old lead pipes into anything from bullets to collectible figurines. But beware! You’ll also be told to wear breathing protection, and long sleeves, and to never get the fumes into your eyes. In fact, it’s not even recommended that you bring any of your lead-casting paraphilia into your home after you’ve used it. Don’t even put the clothes you wear while doing it next to clothing you use for any other purpose! Today we take the dangers of lead poisoning seriously.

It’s likely that many working-class pirates suffered from some level of lead poisoning. Symptoms can vary widely from individual to individual, and can start with relatively low levels of exposure, or at higher levels.

The symptoms – among which are muscle pain, abdominal pain, problems sleeping, depression, and reduced libido, are much like the symptoms of hard work and excessive alcohol. Pirates were also known to have hallucinations and personality changes, also easily attributed to drink. Damaged gums could be blamed on scurvy. Lead poisoning might have plagued many a pirate crew, and it would be hard to tell for sure, without modern blood testing.

Did lead poisoning contribute to the downfall of the pirates? One of the hallmarks of lead poisoning is also decrease in cognitive abilities. This may explain the sometimes vast differences between the pirate deck-hand, a fellow who prided himself in speaking and living by simple truths, and the wily and devious pirate captains, who, with their elevated status probably didn’t cast round shot or paint the boat.

Is it true? I don’t know, but it’s something to think about. One more bit of trivial from the age of pirates.

Published on July 17, 2017 19:34

July 10, 2017

Phantom Islands

The world of 18th century pirates was filled with ghosts, sea monsters, and even Phantom Islands. A phantom island is a supposedly real island that appeared on maps for a period of time (sometimes centuries) during recorded history, but was later proven not to exist.

The most famous phantom island is probably Atlantis. This large island (or small continent, depending on who you listen to) was first recorded by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. He claimed that Atlantis was located “past the pillars of Hercules” – in other words, outside the familiar Mediterranean Sea, in the wide ocean that was eventually named after it.

Plato was trying to make a point about pride. His story tells of a technologically advanced society that fell out of favor with the gods because of the arrogance of its leaders. In his story, Atlantis eventually sank beneath the waves.

This mythical place inspired the name of the Atlantic Ocean, and other imaginary islands have inspired names for real land forms. One is Brasil or Hy-Brasil, an island traditionally believed to lay off the west coast of Ireland. Supposedly, it was shrouded in mist, and could only be seen once every seven years. When explorers saw the South American mainland rising out of the morning mists, they must have thought of Ireland’s imaginary twin.

How do the stories of Phantom Islands begin?

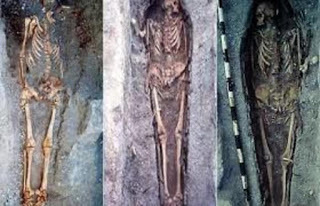

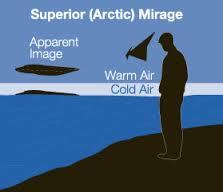

Sometimes, they are started by mirages. Just as the desert can provide images of water to travelers, the sea can offer up imaginary lands. Temperature inversions – layers of warm air laying above cooler air – can actually bend light, making a small object appear to be a towering mass. These kinds of inversions are rare, but can give a definite impression of land.

Another way that a phantom island can be recorded is that the explorer is simply lost. This happened a lot more 300-500 years ago. Misplaced travelers saw Greenland, or Africa, or Japan, when they believed they were far away from those locations, and thought they’d found something new. This is probably the origin of St Mathew Island, said to lie off the coast of Africa. Sailors who reported seeing it were probably looking at Ascension Island, which really does exist.

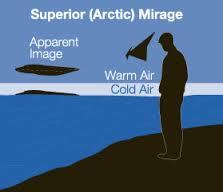

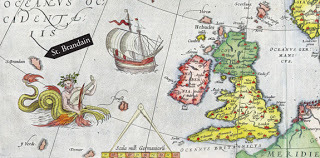

Once an island had been put on a map, there was social pressure for voyagers to confirm its existence. A sailor stands in a bar (or an officer stands before his superiors) and tells a tale of his travels. “Oh, you were near Saint Brendan’s Isle!” says someone. “Did you see it?”

What’s a man to do? “Of course I saw it!”

Some phantoms, such as Saxemberg Island, may have actually existed. It was discovered in 1670, and spotted again in 1804, 1809, and 1816, always in exactly the same location. This island is so well reported that it may have once existed… A piece of land that sank under the sea in some volcanic event.

Plenty of real things have been mistaken for islands. Ice bergs, fog banks, floating masses of seaweed (especially with the help of temperature inversions that makes them seem mountainous.) Antarctica has inspired several phantoms, The Terra Nova islands, for instance, were discovered in near Antarctica 1968, and haven’t been seen since.

Some phantoms are philosophical construction. Rupes Nigra was an island invented in the 14th century to explain why compasses point north. Since no one yet knew about the Earth’s magnetic poles, someone invented a magnetic, black island at the exact place we now call magnetic north.

Some phantoms islands were deliberate fabrications. When money is involved, all things are possible. Croakerland, for instance, was a hoax invented by the famous Arctic explorer, Robert E. Peary, to gain more financial aid from one of his financial bankers, George Crocker. And Isles Phelipeaux and Pontchartrain were invented in the Great Lake Superior in 1744 to persuade French financial backers to cough up more money for further explorations in the area.

But there are plenty of honest explorers out there, too. Johan Otto Polter, found an island he named Kantia. In 1884. But when he returned later, in four expeditions through 1909, he failed to find it again, and disproved the island's existence.

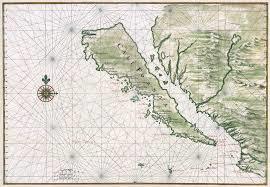

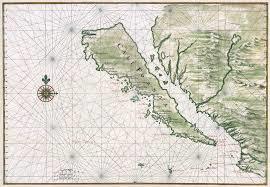

Map of The Island of California

Map of The Island of California

One of the most famous cartographical errors in history is the description of California as an island. This may have been inspired by fiction. A 1510 Spanish romance novel Las sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo - described the island in this passage:

Actual Strait of Baja

Actual Strait of Baja

Know, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons.

Men love those sex-starved Amazons. Whether it was this titillating tale, or an offer by the King of Spain that explorers could lay claim to any new islands they found, but could not similarly profit from discoveries of new sections of mainland, California was shown as an island for nearly 200 years.

Maybe not what they had in mindWhich leads us to one of the most enduring parts of Phantom Islands… their tendency to endure. Once put onto a chart, the predisposition is for the island to stay put. After all, to erase it is, in effectively call its discoverer either a liar or a fool. So, even today, a few unlikely islands and reefs still endure. Once such is Yosemite Rock, “discovered” in 1903, and supposed to be approximately 83°W, 32°S (Northwest of Robinson Crusoe Island). With all our technology, it’s never been officially disproved. Instead, in the Operational Navigation Chart of the United States Department of Defense it is listed as "Existence doubtful."

Maybe not what they had in mindWhich leads us to one of the most enduring parts of Phantom Islands… their tendency to endure. Once put onto a chart, the predisposition is for the island to stay put. After all, to erase it is, in effectively call its discoverer either a liar or a fool. So, even today, a few unlikely islands and reefs still endure. Once such is Yosemite Rock, “discovered” in 1903, and supposed to be approximately 83°W, 32°S (Northwest of Robinson Crusoe Island). With all our technology, it’s never been officially disproved. Instead, in the Operational Navigation Chart of the United States Department of Defense it is listed as "Existence doubtful."

The most famous phantom island is probably Atlantis. This large island (or small continent, depending on who you listen to) was first recorded by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. He claimed that Atlantis was located “past the pillars of Hercules” – in other words, outside the familiar Mediterranean Sea, in the wide ocean that was eventually named after it.

Plato was trying to make a point about pride. His story tells of a technologically advanced society that fell out of favor with the gods because of the arrogance of its leaders. In his story, Atlantis eventually sank beneath the waves.

This mythical place inspired the name of the Atlantic Ocean, and other imaginary islands have inspired names for real land forms. One is Brasil or Hy-Brasil, an island traditionally believed to lay off the west coast of Ireland. Supposedly, it was shrouded in mist, and could only be seen once every seven years. When explorers saw the South American mainland rising out of the morning mists, they must have thought of Ireland’s imaginary twin.

How do the stories of Phantom Islands begin?

Sometimes, they are started by mirages. Just as the desert can provide images of water to travelers, the sea can offer up imaginary lands. Temperature inversions – layers of warm air laying above cooler air – can actually bend light, making a small object appear to be a towering mass. These kinds of inversions are rare, but can give a definite impression of land.

Another way that a phantom island can be recorded is that the explorer is simply lost. This happened a lot more 300-500 years ago. Misplaced travelers saw Greenland, or Africa, or Japan, when they believed they were far away from those locations, and thought they’d found something new. This is probably the origin of St Mathew Island, said to lie off the coast of Africa. Sailors who reported seeing it were probably looking at Ascension Island, which really does exist.

Once an island had been put on a map, there was social pressure for voyagers to confirm its existence. A sailor stands in a bar (or an officer stands before his superiors) and tells a tale of his travels. “Oh, you were near Saint Brendan’s Isle!” says someone. “Did you see it?”

What’s a man to do? “Of course I saw it!”

Some phantoms, such as Saxemberg Island, may have actually existed. It was discovered in 1670, and spotted again in 1804, 1809, and 1816, always in exactly the same location. This island is so well reported that it may have once existed… A piece of land that sank under the sea in some volcanic event.

Plenty of real things have been mistaken for islands. Ice bergs, fog banks, floating masses of seaweed (especially with the help of temperature inversions that makes them seem mountainous.) Antarctica has inspired several phantoms, The Terra Nova islands, for instance, were discovered in near Antarctica 1968, and haven’t been seen since.

Some phantoms are philosophical construction. Rupes Nigra was an island invented in the 14th century to explain why compasses point north. Since no one yet knew about the Earth’s magnetic poles, someone invented a magnetic, black island at the exact place we now call magnetic north.

Some phantoms islands were deliberate fabrications. When money is involved, all things are possible. Croakerland, for instance, was a hoax invented by the famous Arctic explorer, Robert E. Peary, to gain more financial aid from one of his financial bankers, George Crocker. And Isles Phelipeaux and Pontchartrain were invented in the Great Lake Superior in 1744 to persuade French financial backers to cough up more money for further explorations in the area.

But there are plenty of honest explorers out there, too. Johan Otto Polter, found an island he named Kantia. In 1884. But when he returned later, in four expeditions through 1909, he failed to find it again, and disproved the island's existence.

Map of The Island of California

Map of The Island of CaliforniaOne of the most famous cartographical errors in history is the description of California as an island. This may have been inspired by fiction. A 1510 Spanish romance novel Las sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo - described the island in this passage:

Actual Strait of Baja

Actual Strait of BajaKnow, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons.

Men love those sex-starved Amazons. Whether it was this titillating tale, or an offer by the King of Spain that explorers could lay claim to any new islands they found, but could not similarly profit from discoveries of new sections of mainland, California was shown as an island for nearly 200 years.

Maybe not what they had in mindWhich leads us to one of the most enduring parts of Phantom Islands… their tendency to endure. Once put onto a chart, the predisposition is for the island to stay put. After all, to erase it is, in effectively call its discoverer either a liar or a fool. So, even today, a few unlikely islands and reefs still endure. Once such is Yosemite Rock, “discovered” in 1903, and supposed to be approximately 83°W, 32°S (Northwest of Robinson Crusoe Island). With all our technology, it’s never been officially disproved. Instead, in the Operational Navigation Chart of the United States Department of Defense it is listed as "Existence doubtful."

Maybe not what they had in mindWhich leads us to one of the most enduring parts of Phantom Islands… their tendency to endure. Once put onto a chart, the predisposition is for the island to stay put. After all, to erase it is, in effectively call its discoverer either a liar or a fool. So, even today, a few unlikely islands and reefs still endure. Once such is Yosemite Rock, “discovered” in 1903, and supposed to be approximately 83°W, 32°S (Northwest of Robinson Crusoe Island). With all our technology, it’s never been officially disproved. Instead, in the Operational Navigation Chart of the United States Department of Defense it is listed as "Existence doubtful."

Published on July 10, 2017 20:19

July 3, 2017

Logwood Cutters

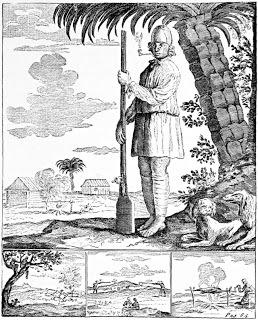

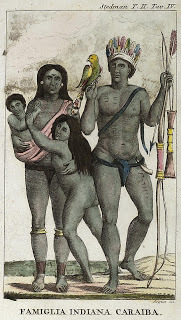

It’s been mentioned before, that the word ‘buccaneer” is closely related to the word “bacon” and that the term defined Englishmen who lived along the Spanish coast of the Americas, where they made their living by cutting a species of tree known as “logwood”, killing and smoking the meat from local pigs, and occasionally paddling out the attack Spanish boats that seemed vulnerable.

Making smoked meat

Making smoked meat

These were casual pirates. Their main interest was the illegally harvested wood. Logwood is a small tree which grows in clumps close to the seashore. Technically, the tree is a legume. It produces a single, edible bead in each of tis many small pods, and flowers with lovely yellow blossoms.

But it was the heartwood, and the sap, that made the trees valuable. The sap could be used to make a good-quality brown dye. The same sap, when treated with simple chemicals, could also produce purple dye. As English landowners converted their holdings from small, rented subsistence farms to larger spaces for cash crops, the business of wool production flourished, and dyes like logwood were in high demand.

Logwood cutting began in the early 1600’s and continued into the 19thcentury, leaving a mark on local culture. The nation of Belize called them “Baymen” and the egalitarian lifestyle they led strongly influenced the formation of Belize’s government.

The Spanish, of course, didn’t like this. They objected to foreigners on soil that they had taken from the natives, and they were enraged by that fact that these people weren’t even Catholic. They chased the logwood cutters off whenever they found them, and sometimes pounded them with cannon fire, captured them and held them as slaves, or caught them and tried to convert them, by torture if necessary.

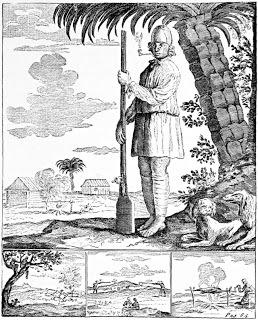

Logwood tree

Logwood tree

Despite this, camps flourished. It was a long coast, with plenty of hidden coves to beach boats on, and lot of jungle to hide in when the occasion arose. With few possessions to protect, these buccaneers had little to lose.

In addition, they were on generally good terms with the natives. The Spanish has long ago conquered the Central and South American population centers, but plenty of natives had fled into the woods. Though the buccaneers occasionally stole canoes and probably posed a danger to native women-folk, they had no interest in changing the native’s religion or chasing them off the land.

Indeed, the buccaneers were willing to trade European manufactured goods for items like food, medicine or tanned animal hides. They were one of the few groups to supply the native with guns, shot and powder (which further enraged the Spanish.) English wild men also brought mirrors, iron pots, knives and so on. Both groups kept a lookout for their enemies, and offered other kinds of support.

After life as a European peasant, logwood cutting must have seemed like paradise. The men worked when they wanted, ate and drank when they pleased, and endured no government but the opinion of their friends. All were equal. Escaped slaves, escaped bond servants, sailors who had jumped ship, all lived together on equitable terms. Of course, it was a rough life. Literate folk who encountered camps of logwood cutters came away with tales of drunkenness, constant swearing and cursing, and occasional violence. These were men who “didn’t know their place.” Or, more likely, they were aiming to carve out a new place for themselves.

One of my favorite observations about the culture comes from an archaeological excavation of a log-cutter camp. The remains of several such camps have been examined, but this one provided something different. Literally hundreds of clay pipes, almost all broken, were scattered around the site. The archaeologist had no idea why this camp should be so well-stocked with pipes, or why they lay in broken heaps.

My own theory is simply that one of this group’s informal raids had provided them with a shipment of pipes. Clay pipes were considered disposable at the time. Pipes could be rented in taverns, but with each new user, the tip was intentionally broken off, for sanitary reasons. After a few uses, the pipe stem would be too short, and the pipe would be discarded. This group, having far more pipes than they actually needed, may have made them a single-use item. Having an abundance of anything, even clay pipes, probably made them feel rich.

When enough logwood had been accumulated, the group would load it onto one or more boats and take it to Jamaica, where they would sell it, and load up on supplies, including vast amounts of rum.

As time went on, dyers in Europe discovered that when logwood sap, treated with copper, it produced a stable black dye, something that had not been available before. Demand grew even larger. This dye colored the formal black eveningwear of the rich, right up through Victorian times. A large-scale planter, Henry Barham, came to the Caribbean in the late 17th century and began planting logwood trees on Jamaica. Rich men made an effort to civilize the trade.

With more and more money coming from the logwood trade, by the early 1700’s the easygoing life of the buccaneers began to break down. The English government pressured the Spanish to recognize these informal English settlements, (though exactly how many settlements and what their locations were was never made clear.) By the end of Piracy’s Golden Age, slaves were doing most of the logwood cutting. Enslaved people, mostly from Africa, harvested the wood for masters who remained in town.

African families were based in settlements near their owners. The women and children worked as house servants, while the men lived in nearby camps and cut the valuable wood. Some of the men took the opportunities offered by their unsupervised work to strike out for freedom, but ties to their families kept most in line. These people were not freed until 1853.

Making smoked meat

Making smoked meatThese were casual pirates. Their main interest was the illegally harvested wood. Logwood is a small tree which grows in clumps close to the seashore. Technically, the tree is a legume. It produces a single, edible bead in each of tis many small pods, and flowers with lovely yellow blossoms.

But it was the heartwood, and the sap, that made the trees valuable. The sap could be used to make a good-quality brown dye. The same sap, when treated with simple chemicals, could also produce purple dye. As English landowners converted their holdings from small, rented subsistence farms to larger spaces for cash crops, the business of wool production flourished, and dyes like logwood were in high demand.

Logwood cutting began in the early 1600’s and continued into the 19thcentury, leaving a mark on local culture. The nation of Belize called them “Baymen” and the egalitarian lifestyle they led strongly influenced the formation of Belize’s government.

The Spanish, of course, didn’t like this. They objected to foreigners on soil that they had taken from the natives, and they were enraged by that fact that these people weren’t even Catholic. They chased the logwood cutters off whenever they found them, and sometimes pounded them with cannon fire, captured them and held them as slaves, or caught them and tried to convert them, by torture if necessary.

Logwood tree

Logwood treeDespite this, camps flourished. It was a long coast, with plenty of hidden coves to beach boats on, and lot of jungle to hide in when the occasion arose. With few possessions to protect, these buccaneers had little to lose.

In addition, they were on generally good terms with the natives. The Spanish has long ago conquered the Central and South American population centers, but plenty of natives had fled into the woods. Though the buccaneers occasionally stole canoes and probably posed a danger to native women-folk, they had no interest in changing the native’s religion or chasing them off the land.

Indeed, the buccaneers were willing to trade European manufactured goods for items like food, medicine or tanned animal hides. They were one of the few groups to supply the native with guns, shot and powder (which further enraged the Spanish.) English wild men also brought mirrors, iron pots, knives and so on. Both groups kept a lookout for their enemies, and offered other kinds of support.

After life as a European peasant, logwood cutting must have seemed like paradise. The men worked when they wanted, ate and drank when they pleased, and endured no government but the opinion of their friends. All were equal. Escaped slaves, escaped bond servants, sailors who had jumped ship, all lived together on equitable terms. Of course, it was a rough life. Literate folk who encountered camps of logwood cutters came away with tales of drunkenness, constant swearing and cursing, and occasional violence. These were men who “didn’t know their place.” Or, more likely, they were aiming to carve out a new place for themselves.

One of my favorite observations about the culture comes from an archaeological excavation of a log-cutter camp. The remains of several such camps have been examined, but this one provided something different. Literally hundreds of clay pipes, almost all broken, were scattered around the site. The archaeologist had no idea why this camp should be so well-stocked with pipes, or why they lay in broken heaps.

My own theory is simply that one of this group’s informal raids had provided them with a shipment of pipes. Clay pipes were considered disposable at the time. Pipes could be rented in taverns, but with each new user, the tip was intentionally broken off, for sanitary reasons. After a few uses, the pipe stem would be too short, and the pipe would be discarded. This group, having far more pipes than they actually needed, may have made them a single-use item. Having an abundance of anything, even clay pipes, probably made them feel rich.

When enough logwood had been accumulated, the group would load it onto one or more boats and take it to Jamaica, where they would sell it, and load up on supplies, including vast amounts of rum.

As time went on, dyers in Europe discovered that when logwood sap, treated with copper, it produced a stable black dye, something that had not been available before. Demand grew even larger. This dye colored the formal black eveningwear of the rich, right up through Victorian times. A large-scale planter, Henry Barham, came to the Caribbean in the late 17th century and began planting logwood trees on Jamaica. Rich men made an effort to civilize the trade.

With more and more money coming from the logwood trade, by the early 1700’s the easygoing life of the buccaneers began to break down. The English government pressured the Spanish to recognize these informal English settlements, (though exactly how many settlements and what their locations were was never made clear.) By the end of Piracy’s Golden Age, slaves were doing most of the logwood cutting. Enslaved people, mostly from Africa, harvested the wood for masters who remained in town.

African families were based in settlements near their owners. The women and children worked as house servants, while the men lived in nearby camps and cut the valuable wood. Some of the men took the opportunities offered by their unsupervised work to strike out for freedom, but ties to their families kept most in line. These people were not freed until 1853.

Published on July 03, 2017 18:11

June 26, 2017

Ye Scurvy Dog!

Pirate insults and what they meant.Scurvy dog, Lily-livered, Scabrous, Bilge rat, Poxy. You’re being insulted by a pirate, but you have no idea what any of it means.

Pirate slang, like any other kind, was strongly influenced by popular culture of the time. Just as modern phrases like “Not woke” are going to confuse future generations (He’s asleep?) pirate slang depended on knowing what was going on at the time. Popular songs, national culture, and even medical knowledge affected what word pirates used when they were angry, just like today. Let’s take a look.

Dog The Spanish were famous for calling the English “dogs.” “English dog!” was about as strong an insult as they felt like heaving around. What’s wrong with dogs? And why were the French not “dogs”? Or the Spanish themselves, for that matter?

To understand, you need to remember that the Moors, people of the Muslim faith, conquered parts of Spain and held the territory for roughly 700 years. A lot of Moorish culture wore off on Catholic Spain during this time, and Moors regarded dogs as ritually unclean. Dog drool was especially yucky. A person who touched dog drool was supposed to wash 7 times.

The ”dog” insult was especially pertinent to the English because of the Catholic/Protestant divide. By not being Catholic, the English were sort of “ritually unclean” as well. Also, the Protestant religion of the time discouraged bathing, calling it “worldly” and “luxurious.” Protestant Christians were supposed to ignore their physical bodies as much as possible. Of course, this didn’t smell very nice.

So the English were, by Spanish beliefs, spiritually unclean, and pretty physically dirty as well. Thus, “dogs.”

The English, who liked dogs just fine, used the insult as a mark of pride, and called themselves “sea dogs.”

Scurvy was also used as an insult. Most people know that the disease scurvy makes your teeth fall out. But the early stages of the disease, the ones more people had encountered, were marked by loss of strength and by emotional depression.

Winner of the 2014 World's Ugliest Dog Contest. His owners love him, I promise.

Winner of the 2014 World's Ugliest Dog Contest. His owners love him, I promise.

Loss of strength was a loss of manliness, and depression, just like now, held a lot of social stigma. People of the time called it “a lowering of spirits.” So, to refer to someone as a “scurvy” individual was to call them a weakling without pride or enthusiasm.

Scabrous means covered in scabs, or mange. A “scabrous dog” is a mangy mutt.

Poxy was another insult based on sickness. Smallpox, a deadly disease, often left its (living) victims horribly scarred. Marks similar to the worst possible acne scars would cover the face, the hands, and sometimes the whole body. Calling someone “poxy” generally meant “ugly.”

Sorry, no pictures of Smallpox. It's really too horrible.

Sorry, no pictures of Smallpox. It's really too horrible.

But “pox” was often a general term for any disease. And during this time period, the most fearful disease was the “French pox” (“English pox” to the French) known today as syphilis. Then as now, catching such a sexually transmitted disease carried a social stigma. So “poxy” could carry some of that, as well.

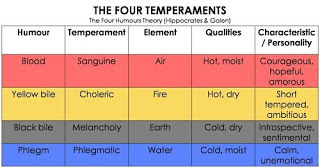

Lily-livered has got to be my favorite pirate insult. On the surface it makes on sense at all. Lilies are flowers, and the liver is an internal organ. What do they have to do with each other and how do they add up to an insult?

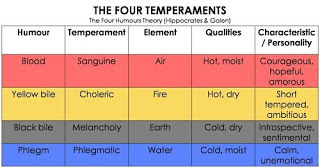

Let’s start with a little medial background. 300 years ago, people believed that their bodies were made up of a combination of 4 primal liquids –yellow bile, black bile, phlegm, and blood. When the proper amounts of these liquids mixed together, everything was fine. But when the liquids were out of balance, a person became sick.

However, most people had a predisposition to carry a little more of one fluid than the others. This affected the general characteristics of the body and personality. An abundance of phlegm, for instance, made a person who was introverted, “cold” emotionally, and had breathing problems.

Blood supposedly supplied courage, energy, and a happy, outgoing personality. Doctors at the time thought that all blood was made by the liver. (Part of this was because a healthy liver looks like a giant blood clot. It should be noted here that a sickly liver usually becomes pale.)

Now, about lilies. This ties to popular music and poetry of the day. Lilies were famously white. And soft. So descriptions of beautiful maidens referred to their “lily-white hands” as in “I took up her lily white hand…” Slightly racier songs remarked on the lady’s “lily white breast.” It was a cliché.

So, when one man calls another “lily livered” he means that the organ producing that man’s bravery is atrophied, sick, unable to do its job. The man is without courage. Furthermore, by referring to the organ as lily colored, rather than merely pale, the insulter also notes a similarity between his victim and a pretty young maiden. Not a comparison that most men appreciate.

Bilge rat Rats infested all wooden sailing ships. It was a fact of life. Hundreds, even thousands of them lived on a typical ship, and being social animals, they formed their own pecking order and society. High-ranking rats lived near the ship’s stores, enjoying the best food, and also may have enjoyed the relative peace and quiet of the captain’s quarters. Less healthy or strong rats may have lived officers’ quarters, and nursing mothers may have enjoyed the areas where spare sails were kept.

But the bilge – the very lowest level of the ship, was not a comfortable home for anything. The area collected all the water that seeped aboard. This stagnant water brewed up a terrible smell, augmented by sailors who used it as a toilet when seas were rough. In addition, since humans stayed away most of the time, there was no food… No stores, no table scraps. Anything forced by its society to live in this uncomfortable and lonely place was probably sick or crippled, and possibly disliked as well. To be a bilge rat was to be the lowest kind of rat their was.

Well there you go, the meanings of some of the most popular pirate insults. And if you’ve got one not mentioned here, put it in the comments, and I’ll see what I can do!

Pirate slang, like any other kind, was strongly influenced by popular culture of the time. Just as modern phrases like “Not woke” are going to confuse future generations (He’s asleep?) pirate slang depended on knowing what was going on at the time. Popular songs, national culture, and even medical knowledge affected what word pirates used when they were angry, just like today. Let’s take a look.

Dog The Spanish were famous for calling the English “dogs.” “English dog!” was about as strong an insult as they felt like heaving around. What’s wrong with dogs? And why were the French not “dogs”? Or the Spanish themselves, for that matter?

To understand, you need to remember that the Moors, people of the Muslim faith, conquered parts of Spain and held the territory for roughly 700 years. A lot of Moorish culture wore off on Catholic Spain during this time, and Moors regarded dogs as ritually unclean. Dog drool was especially yucky. A person who touched dog drool was supposed to wash 7 times.

The ”dog” insult was especially pertinent to the English because of the Catholic/Protestant divide. By not being Catholic, the English were sort of “ritually unclean” as well. Also, the Protestant religion of the time discouraged bathing, calling it “worldly” and “luxurious.” Protestant Christians were supposed to ignore their physical bodies as much as possible. Of course, this didn’t smell very nice.

So the English were, by Spanish beliefs, spiritually unclean, and pretty physically dirty as well. Thus, “dogs.”

The English, who liked dogs just fine, used the insult as a mark of pride, and called themselves “sea dogs.”

Scurvy was also used as an insult. Most people know that the disease scurvy makes your teeth fall out. But the early stages of the disease, the ones more people had encountered, were marked by loss of strength and by emotional depression.

Winner of the 2014 World's Ugliest Dog Contest. His owners love him, I promise.

Winner of the 2014 World's Ugliest Dog Contest. His owners love him, I promise. Loss of strength was a loss of manliness, and depression, just like now, held a lot of social stigma. People of the time called it “a lowering of spirits.” So, to refer to someone as a “scurvy” individual was to call them a weakling without pride or enthusiasm.

Scabrous means covered in scabs, or mange. A “scabrous dog” is a mangy mutt.

Poxy was another insult based on sickness. Smallpox, a deadly disease, often left its (living) victims horribly scarred. Marks similar to the worst possible acne scars would cover the face, the hands, and sometimes the whole body. Calling someone “poxy” generally meant “ugly.”

Sorry, no pictures of Smallpox. It's really too horrible.

Sorry, no pictures of Smallpox. It's really too horrible. But “pox” was often a general term for any disease. And during this time period, the most fearful disease was the “French pox” (“English pox” to the French) known today as syphilis. Then as now, catching such a sexually transmitted disease carried a social stigma. So “poxy” could carry some of that, as well.

Lily-livered has got to be my favorite pirate insult. On the surface it makes on sense at all. Lilies are flowers, and the liver is an internal organ. What do they have to do with each other and how do they add up to an insult?

Let’s start with a little medial background. 300 years ago, people believed that their bodies were made up of a combination of 4 primal liquids –yellow bile, black bile, phlegm, and blood. When the proper amounts of these liquids mixed together, everything was fine. But when the liquids were out of balance, a person became sick.

However, most people had a predisposition to carry a little more of one fluid than the others. This affected the general characteristics of the body and personality. An abundance of phlegm, for instance, made a person who was introverted, “cold” emotionally, and had breathing problems.

Blood supposedly supplied courage, energy, and a happy, outgoing personality. Doctors at the time thought that all blood was made by the liver. (Part of this was because a healthy liver looks like a giant blood clot. It should be noted here that a sickly liver usually becomes pale.)

Now, about lilies. This ties to popular music and poetry of the day. Lilies were famously white. And soft. So descriptions of beautiful maidens referred to their “lily-white hands” as in “I took up her lily white hand…” Slightly racier songs remarked on the lady’s “lily white breast.” It was a cliché.

So, when one man calls another “lily livered” he means that the organ producing that man’s bravery is atrophied, sick, unable to do its job. The man is without courage. Furthermore, by referring to the organ as lily colored, rather than merely pale, the insulter also notes a similarity between his victim and a pretty young maiden. Not a comparison that most men appreciate.

Bilge rat Rats infested all wooden sailing ships. It was a fact of life. Hundreds, even thousands of them lived on a typical ship, and being social animals, they formed their own pecking order and society. High-ranking rats lived near the ship’s stores, enjoying the best food, and also may have enjoyed the relative peace and quiet of the captain’s quarters. Less healthy or strong rats may have lived officers’ quarters, and nursing mothers may have enjoyed the areas where spare sails were kept.

But the bilge – the very lowest level of the ship, was not a comfortable home for anything. The area collected all the water that seeped aboard. This stagnant water brewed up a terrible smell, augmented by sailors who used it as a toilet when seas were rough. In addition, since humans stayed away most of the time, there was no food… No stores, no table scraps. Anything forced by its society to live in this uncomfortable and lonely place was probably sick or crippled, and possibly disliked as well. To be a bilge rat was to be the lowest kind of rat their was.

Well there you go, the meanings of some of the most popular pirate insults. And if you’ve got one not mentioned here, put it in the comments, and I’ll see what I can do!

Published on June 26, 2017 19:19

June 19, 2017

New Pirate Music

I don’t get to travel to nearly as many festivals as I’d like. Work, and obligations, and the fact that I make money more like a deck hand than a pirate lord keep me closer to home than I want to be. (Though if anyone would like to hire a pirate storyteller for their event, just shoot me a line at info@tsrhodes.com) So I don’t get to hear as much pirate music as I’d like.

But lately I’ve discovered some new (to me) bands and some new songs.

The Musical Blades started out a decade ago, as a comedy sword act in Kansas City – just about as far from piratical waters as it’s possible to get! Over the years their act grew and evolved, until they are now a full-fledged pirate band. The Blades have just released their tenth full-length album, “Live at the Voodoo.”

This group is tight, talented, and very creative. Renaissance Magazine awarded them Best New CD, Best Live Music Group, and Best Comedy Musical Show for 2016, with additional awards coming from other sources. Even their Facebook Page has won awards!

All I can say about these guys is – Where have you been all my life? (Yeah, I know. I’ve had my head stuck in a history book.)

So, for your enjoyment, here is the first of two of my favorite Blades songs, an original with a deceptively slow intro. Listen carefully, and you’ll catch a line from Pirates of the Caribbean, Curse of the Black Pearl.

Gotta dig the Black Sails images on this. (Black Sails had some great moments and a few idiotic ones, but the cinematography was always outstanding.)

Now, for our next offering, a song with a long history. A VERY long history. “Whiskey in the Jar” probably dates back to about the middle of the 17th century. There is some evidence that it was at least partially based on the life of an Irish highwayman (robber) named Patrick Flemmen who was hanged in 1650.

It’s an Irish rebel song, sung by nearly anyone who didn’t like being occupied by the English. The basic story is about a highwayman who robs an English army captain and gets away with the money. He goes home to his wife/lover, taking the loot. But as he sleeps, she betrays him and he is captured. The song often ends with the singer’s hope that his brother will help him escape, and the two of them will be robbers together in the Irish mountains.

And what does this have to do with pirates? Not a single thing.

BUT the song has been stuck into pirate playlists for decades. Pirates, after all, didn’t like the English, and they considered themselves to be in a state of rebellion. It doesn’t hurt at all that the Englishman robbed is a “captain.” And different version of the song have been sung in Scotland and even the United States – anywhere the English were unwelcome.

But even though the song is very popular, it still has not much to do with pirates. Until the Musical Blades got a hold of it. That is. A little pirate history, a little lyrical magic, and we have a filk song – a song whose lyrics have been altered in order to appeal to a special interest group, in this case, pirate lovers.

Our next band is The Jolly Rogers, another group that flits around the Midwest. They’ve been recording since 1992, with a total of 12 albums to their credit (thought the first 4 are out of print.) Their latest, XXV (Twenty five in Roman numerals, for those of you who ain’t read your classics.) The album covers a lot of ground – 32 songs, ranging from traditional shanties to original works.

This group does not have the professional finish of the Blades, but enthusiasm, imagination and hard work have taken them a long way. My favorite here is “The Flying Dutchman.” It’s hard to do a whole song that’s frightening and creepy, but the Rogers manage it here quite nicely. The driving rhythms move the song forward and the lyrics send a shiver up your spine.

I’ve saved the best for last. It’s been out since 2007, an comes from a real-live revolutionary. David Rovics is an anarchist, a critic of the Republican Party, Democratic Party, George W. Bush, and John Kerry. He also knows his pirates.

Rovics’ song is as close to history as a pirate song has ever gotten, and it’s pretty plain that he wishes that the pirates had taken over the world. Rovics is so enthusiastic about the “pirate” lifestyle that he has a song called “Steal this MP3.” And he gives a lot of his music away for free. And sheet music. And you can watch the video on his site without commercials.

So that’s my latest pirate music lineup. Visit the sites, download the music, and support these artists. It’s the piratical thing to do.

Published on June 19, 2017 20:03

June 12, 2017

A Pirate Rope for Me

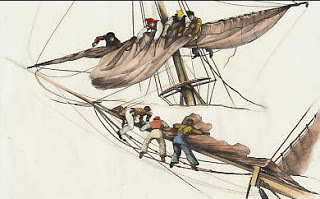

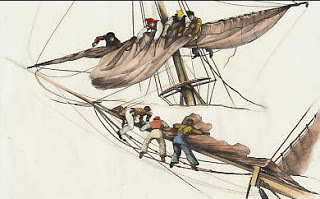

Rope bounded the lives of pirates, as it did for all sea-faring men. Rope held their vessels together, lifted their sails, held them to docks or to the sea bottom via the ship’s anchor. Men climbing to trim the sails depended on well-maintained rope to support them. And in an era when absolutely no safety regulations existed, damaged rope was a reason for mutiny.

A piece of preserved rope found on board the 16th century carrack

Mary Rose

A piece of preserved rope found on board the 16th century carrack

Mary Rose

The earliest evidence we have of human-made rope is in impressions made in clay and dating back 28,000 years. (No, that’s not a mistake.) Our earliest actual example of rope is a fossilized piece of “two-ply laid rope” which was found in the famous Caves of Lascaux – the ones with the famous animal paintings. These fossilized pieces date to approximately 15,000 BC.

All kinds of materials have been used to make rope. Palm fiber, flax, grass, animal hair and leather have all been pressed into use. By the late Middle Ages, and through the Golden Age of Piracy, hemp rope was the accepted standard. Hemp is a fast-growing plant, and produces long, strong fibers. Unfortunately, like most natural materials, it is prone to rot.

Rope was made in “ropewalks”, an early sort of factory. Fibers were twisted together into twine, then twine was twisted into rope. The process involved enormous amounts of both skill and humans muscle. Teams of men walked backwards, while hauling and twisting the fibers. The process produced a set length of rope, not a continuous stretch. In the early 17th century, Peter Appleby constructed a 300-metre long ropewalk (for the dockyard) in Copenhagen, Denmark.

As navies rose in importance, rope making became a matter of national security. The ropewalk at Chatham Dockyard in England is still producing rope commercially and has an internal length of 1,135 ft (346 m). When it was constructed in 1790, it was the longest brick building in Europe. The facility produced a huge variety of rope, and provide jobs for strong, skilled workers. It took over 200 men to form and close a 20-inch (circumference) cable laid rope.

The lengths of the buildings and the functional maximum length that a single length of rope could be made gave shipping a measurement – the “cable length” or average length of a piece of rope. Roughly 800 feet (thought it varies between nations.)

What if you needed a piece of rope more than 800 feet long? This could only be achieved by splicing, a method of braiding or weaving the ends of rope together to make a longer piece. Though different styles of splicing rope exist, each has its own problems. Some create a weak place in the rope. Others don’t, but make a bulge, which is difficult to get through pulleys.

But once it’s been put to use, rope is no longer rope. A ship may contain up to several MILES of rope, but each piece has a name and a function. It could take a novice sailor years to memorize all of this, and during the time he was studying, he was said to be “learning the ropes.” The phrase has since been adopted by other professions, signifying a period when a new employee is picking up the basics of his or her new workplace.

As an example of terminology, rope that is purposely sized, cut, spliced, or simply assigned a function, is referred to as a "line". Sail control lines are mainly referred to as sheets, for example a jibsheet. A halyard is a line used to raise and lower a sail, and is typically made of a length of rope with a shackle attached at one end. Other examples include anchor line ("rode"), stern line, marline and so on.

Most importantly for sailors, rope dating from the Golden Age of Piracy needs to be maintained. At minimum, current safety experts recommend that all natural-fiber lines should be inspected every year, with an eye to replacement. High-stress lines should be inspected every three to six months. Life-critical lines, such as the toe lines that sailors stood on while furling sails, should be inspected before every use.

But in the 17th and 18th century, there were no safety standards, and no requirements. Ship-owning corporations wanted lines to last as long as possible. Maintaining materials in the service of lowering maintenance costs was common practice. Lines were tarred (waterproofed) so often that sailors were known by the smell of tar they carried on their clothes., and even called by the nickname “Jack Tar.” Elaborate systems of protection came into practice (see the video below) But some commanders, ignorant of the properties of hemp, (most captains had been schooled in reading and writing, literature, cyphering or bookkeeping, astronomy or navigation and geography, but not the hands-on work of a ship) saw reason to replace lines only when they failed.

Enjoy this fine video about splicing and caring for line.

The fact that this might mean that one or more sailors died was not a problem, since a work-related death did not cost the company any money. In addition, time spent inspecting rope was not time spent making the ship go faster, or moving more cargo. Sailors were often left to discover dangerous lines by themselves. And since hemp rope absorbed water, it was most likely to rot from the inside out, hiding defects. A captain or corporate officer might ignore information from sailors about unsafe working conditions. Indeed, he might have a sailor who insisted on presenting facts about failing rigging flogged in punishment. After all, how dare a common sailor tell a captain how to run his ship?

Deaths and injuries from unsafe rigging had no direct effect on shipping companies or captains. But word got out that such-and-such was not a safe ship, and sailors looking for work tried to avoid these vessels. And when sailors were injured or killed resentment rose. This was exactly the kind of bad feeling which drove men to become pirates. After all, on a pirate vessel, officers were dependent on the good will of the crew, and having risen from the ranks (in most cases) pirate captains had first-hand knowledge of the dangers of old rope.

A piece of preserved rope found on board the 16th century carrack

Mary Rose

A piece of preserved rope found on board the 16th century carrack

Mary Rose

The earliest evidence we have of human-made rope is in impressions made in clay and dating back 28,000 years. (No, that’s not a mistake.) Our earliest actual example of rope is a fossilized piece of “two-ply laid rope” which was found in the famous Caves of Lascaux – the ones with the famous animal paintings. These fossilized pieces date to approximately 15,000 BC.

All kinds of materials have been used to make rope. Palm fiber, flax, grass, animal hair and leather have all been pressed into use. By the late Middle Ages, and through the Golden Age of Piracy, hemp rope was the accepted standard. Hemp is a fast-growing plant, and produces long, strong fibers. Unfortunately, like most natural materials, it is prone to rot.

Rope was made in “ropewalks”, an early sort of factory. Fibers were twisted together into twine, then twine was twisted into rope. The process involved enormous amounts of both skill and humans muscle. Teams of men walked backwards, while hauling and twisting the fibers. The process produced a set length of rope, not a continuous stretch. In the early 17th century, Peter Appleby constructed a 300-metre long ropewalk (for the dockyard) in Copenhagen, Denmark.

As navies rose in importance, rope making became a matter of national security. The ropewalk at Chatham Dockyard in England is still producing rope commercially and has an internal length of 1,135 ft (346 m). When it was constructed in 1790, it was the longest brick building in Europe. The facility produced a huge variety of rope, and provide jobs for strong, skilled workers. It took over 200 men to form and close a 20-inch (circumference) cable laid rope.

The lengths of the buildings and the functional maximum length that a single length of rope could be made gave shipping a measurement – the “cable length” or average length of a piece of rope. Roughly 800 feet (thought it varies between nations.)

What if you needed a piece of rope more than 800 feet long? This could only be achieved by splicing, a method of braiding or weaving the ends of rope together to make a longer piece. Though different styles of splicing rope exist, each has its own problems. Some create a weak place in the rope. Others don’t, but make a bulge, which is difficult to get through pulleys.

But once it’s been put to use, rope is no longer rope. A ship may contain up to several MILES of rope, but each piece has a name and a function. It could take a novice sailor years to memorize all of this, and during the time he was studying, he was said to be “learning the ropes.” The phrase has since been adopted by other professions, signifying a period when a new employee is picking up the basics of his or her new workplace.

As an example of terminology, rope that is purposely sized, cut, spliced, or simply assigned a function, is referred to as a "line". Sail control lines are mainly referred to as sheets, for example a jibsheet. A halyard is a line used to raise and lower a sail, and is typically made of a length of rope with a shackle attached at one end. Other examples include anchor line ("rode"), stern line, marline and so on.

Most importantly for sailors, rope dating from the Golden Age of Piracy needs to be maintained. At minimum, current safety experts recommend that all natural-fiber lines should be inspected every year, with an eye to replacement. High-stress lines should be inspected every three to six months. Life-critical lines, such as the toe lines that sailors stood on while furling sails, should be inspected before every use.

But in the 17th and 18th century, there were no safety standards, and no requirements. Ship-owning corporations wanted lines to last as long as possible. Maintaining materials in the service of lowering maintenance costs was common practice. Lines were tarred (waterproofed) so often that sailors were known by the smell of tar they carried on their clothes., and even called by the nickname “Jack Tar.” Elaborate systems of protection came into practice (see the video below) But some commanders, ignorant of the properties of hemp, (most captains had been schooled in reading and writing, literature, cyphering or bookkeeping, astronomy or navigation and geography, but not the hands-on work of a ship) saw reason to replace lines only when they failed.

Enjoy this fine video about splicing and caring for line.

The fact that this might mean that one or more sailors died was not a problem, since a work-related death did not cost the company any money. In addition, time spent inspecting rope was not time spent making the ship go faster, or moving more cargo. Sailors were often left to discover dangerous lines by themselves. And since hemp rope absorbed water, it was most likely to rot from the inside out, hiding defects. A captain or corporate officer might ignore information from sailors about unsafe working conditions. Indeed, he might have a sailor who insisted on presenting facts about failing rigging flogged in punishment. After all, how dare a common sailor tell a captain how to run his ship?

Deaths and injuries from unsafe rigging had no direct effect on shipping companies or captains. But word got out that such-and-such was not a safe ship, and sailors looking for work tried to avoid these vessels. And when sailors were injured or killed resentment rose. This was exactly the kind of bad feeling which drove men to become pirates. After all, on a pirate vessel, officers were dependent on the good will of the crew, and having risen from the ranks (in most cases) pirate captains had first-hand knowledge of the dangers of old rope.

Published on June 12, 2017 18:55

June 5, 2017

Pirates of the Caribbean - Dead Men Tell No Tales Trivia

So much to say abut the POTC movies. So this week I thought I’d share a little trivia, some historic, some merely interesting.

1. The British flag in the beginning of the movie is not the modern one, but it is historically accurate. The original English flag was a red cross on a white background. The Scottish flag was a white X on a blue background. When England and Scotland merged their flags in 1606, the two symbols were imposed over each other on the same flag. The flag stayed this way until 1801, when the red X of Ireland was added, making the modern flag.

[image error]

2. Jack Sparrow seems to have hit rock bottom in Dead Men Tell No Tales, but there have also been some good times since we saw him last. One of his teeth has been inset with a ruby.

3. Captain Jack Sparrow still has the right to call himself captain, even though his current, pitiful command is in dry dock. The small vessel is named the Dying Gull. Why? If it came that way, you can bet that Joshamee Gibbs has something to do with letting the name remain as it came. And if the pirates re-named the boat, this may be the cause of their current desperate state. Re-naming a boat is said to bring bad luck.

4. Carina Smith couldn’t have been a horologist. Yes, the word means “student of time” and it can refer to folks like watchmakers. But the word wasn’t coined until 1819, many years after the Pirates movies take place. No wonder everyone thought she was in a different line of work.

5. The phrase “Dead men tell no tales” was first used by Francis Becon (not Bacon) in about 1560. It means that once dead, a person cannot reveal secrets. Some people think that Long John Silver says this in the novel Treasure Island. But his phrase is, “Dead men don’t bite.”

6. The two pirates who interrupt Barbossa as he is eating were the two redcoats (Royal Marines) who were guarding the Interceptor in POTC I, right before Jack stole it. When Cutler Becket met his downfall, they deserted the Royal Navy and became pirates.

7. In the movie, the inhabitants of the island of St. Martin seem to all be English, but in reality the island was divided between the French and the Dutch. (The French/Dutch border, still in place on the island, is the only place on earth where France and the Netherlands share a border.)

8. The “Devil’s Triangle” wasn’t a thing back in pirating days, when there were no radios for communication, and ships got lost often and wrecked on a regular basis. The first reference to anything odd happening in this loosely defined patch of sea was in a newspaper article published in the Miami Herald on September 17, 1950.

9. Sailors are famous for their knowledge of stars, since astronomy is a vital part of navigation at sea. So Barbossa should have known that “Carina” is not a star, but a constellation. Or, he might have been celebrating the discovery of the Carina nebula on January 25 1752. But if the writers had gone with that, they would have had a hard time convincing us that the girl Carina was being accused of Witchcraft. After all, they “mysterious symbols” she was using were standard astrological notation, common knowledge to any educated person of the time.

10. Lieutenant Scarfield, the second antagonist of the film and a British Royal Navy officer and commander of the HMS Essex is played by David Wenham. Fantasy fans will know his for portraying Faramir in Lord of the Rings.

11. In the first POTC movie, Curse of the Black Pearl, the makeup designer decided to give Jack Sparrow a small open sore low on his right jaw. The sore has stayed in place, and has gotten bigger in every pirates movie since.

12. When Keith Richards had a scheduling conflict and couldn’t reprise his role as Jack’s father, an on-set brainstorming session suggested that Sir Paul McCartney might be a similarly notorious elder pirate. Johnny Depp has the former Beatle in his phone contacts, so he asked the famous rocker to come by a pirate via text.

13. The song McCartney is singing is an old sea shanty from Liverpool called Maggie May (NOT the Rod Stewart song.) It tells the story of a Paradise Street prostitute who is famous for robbing her customers, and is eventually sent to a penal colony. Nope, not a pirate song. It was written in the 1800’s.

14. The reason that the Black Pearl did not appear in the last movie was because it’s not a real ship – it’s a floating prop, built on a barge so it will look like it’s sailing. In Pirates 4 they needed to barge to build the Queen Anne’s Revenge on, so the Pearl had to be bottled. With no real rival ships in Pirates 5, the Pearl is free to float again.

15. Whatever powers Jack’s magic compass, it apparently isn’t a curse. After all curses are lifted, Jack still trusts the compass to help him reach his heart’s desire.

1. The British flag in the beginning of the movie is not the modern one, but it is historically accurate. The original English flag was a red cross on a white background. The Scottish flag was a white X on a blue background. When England and Scotland merged their flags in 1606, the two symbols were imposed over each other on the same flag. The flag stayed this way until 1801, when the red X of Ireland was added, making the modern flag.

[image error]

2. Jack Sparrow seems to have hit rock bottom in Dead Men Tell No Tales, but there have also been some good times since we saw him last. One of his teeth has been inset with a ruby.

3. Captain Jack Sparrow still has the right to call himself captain, even though his current, pitiful command is in dry dock. The small vessel is named the Dying Gull. Why? If it came that way, you can bet that Joshamee Gibbs has something to do with letting the name remain as it came. And if the pirates re-named the boat, this may be the cause of their current desperate state. Re-naming a boat is said to bring bad luck.

4. Carina Smith couldn’t have been a horologist. Yes, the word means “student of time” and it can refer to folks like watchmakers. But the word wasn’t coined until 1819, many years after the Pirates movies take place. No wonder everyone thought she was in a different line of work.

5. The phrase “Dead men tell no tales” was first used by Francis Becon (not Bacon) in about 1560. It means that once dead, a person cannot reveal secrets. Some people think that Long John Silver says this in the novel Treasure Island. But his phrase is, “Dead men don’t bite.”

6. The two pirates who interrupt Barbossa as he is eating were the two redcoats (Royal Marines) who were guarding the Interceptor in POTC I, right before Jack stole it. When Cutler Becket met his downfall, they deserted the Royal Navy and became pirates.

7. In the movie, the inhabitants of the island of St. Martin seem to all be English, but in reality the island was divided between the French and the Dutch. (The French/Dutch border, still in place on the island, is the only place on earth where France and the Netherlands share a border.)

8. The “Devil’s Triangle” wasn’t a thing back in pirating days, when there were no radios for communication, and ships got lost often and wrecked on a regular basis. The first reference to anything odd happening in this loosely defined patch of sea was in a newspaper article published in the Miami Herald on September 17, 1950.

9. Sailors are famous for their knowledge of stars, since astronomy is a vital part of navigation at sea. So Barbossa should have known that “Carina” is not a star, but a constellation. Or, he might have been celebrating the discovery of the Carina nebula on January 25 1752. But if the writers had gone with that, they would have had a hard time convincing us that the girl Carina was being accused of Witchcraft. After all, they “mysterious symbols” she was using were standard astrological notation, common knowledge to any educated person of the time.