T.S. Rhodes's Blog, page 5

May 15, 2017

Gold

Pirate stories revolve around gold. Spanish gold, in preference, but any gold will do. Gold – getting it, keeping it, occasionally even getting rid of it, makes a pirate story work. It made the discovery and exploitation of the New World work, too. Without gold, history would have taken a very different turn.

As we now know, Columbus was far from the first European to set foot in the Western Hemisphere. The Vikings had established colonies in Greenland and northern Canada, and had dealings with several native American tribes.

There is also evidence that Europeans fished the Grand Banks of Newfoundland for codfish long before Columbus made his fateful voyage. Fish and trade with Native Americans brought riches to those who dared to think outside the box. But these were working class riches. No kings lusted after codfish.

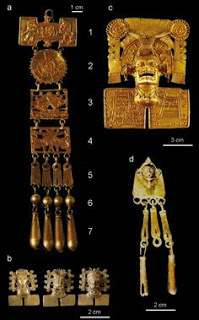

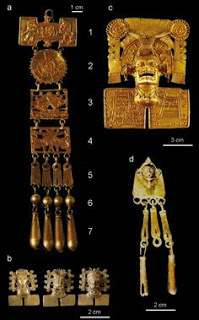

But on his first voyage, Columbus saw something to whet the appetite. Rowing out to meet him came natives… Nearly naked, rowing canoes, and wearing gold jewelry.

Gold jewelry was uncommon in Europe. Even nobility often didn’t own jewelry made of solid gold. In 1522, Anne Boleyn, child of a noble English family, educated in France, sent to be lady-in-waiting to England’s queen, brought with her only one piece of “gold” jewelry. It was really base metal, with a thin coating of gold, and the coating was visibly wearing off.

And in the Caribbean, half-naked “savages” wore jewelry of solid gold.

Needless to say, this excited the Powers That Be, and this effectively green-lit all subsequent voyages of exploration.

So why did the natives have gold?

Credit the Andes Mountains. Their geological formation has brought up many kinds of metal. Lead, copper, silver, and yes, gold, are abundant in the Andes.

Natives took these metals from streams that flowed out of the mountains. They liked the gold and silver, but only as a decorative material. They used it to make jewelry and to decorate statues and temples, but they did not make coins. The Carib, the Arawak, even the Incas used a barter system. They traded ducks for wool and thatched houses to pay their taxes.

One constant was that doing work for the Incan government was recorded, and could be “held” for years, being doled out to pay taxes or perhaps even traded for other goods. Sometimes the work that people did was to decorate public buildings or create statues. Gold was often used for these purposes.

The natives valued gold. It’s relatively easy to bring out of ore, it shines, and it does not ever tarnish. It’s also so soft that it’s easy to “work.” Gold can be pounded into a foil thinner than paper, or it can be shaped into cups, statues, and of course, jewelry.

But they didn’t value it more than beautiful bird feathers, or shiny shells, or other pretty things. Still, they had been picking up bits of gold that washed down from streams that began in the Andes for thousands of years. The Incas had a lot of gold.

So much that, when the Spanish conquistadores captures the Incan emperor, Atahualpa, he offered to fill a giant room half full of gold, and then fill it again twice with silver, if the Spanish would let him go. They agreed, not really believing him, and were shocked when the metal actually showed up. The gold alone, some 13,000 pounds of it, would be worth over two hundred and fifty Milliondollars today.

As the Spanish took over land in South America, they began to systematically mine gold. The mines were crude by modern standards, but they followed veins of gold, and produced the metal in near-industrial quantities. Between 1500 and 1650, the Spanish (officially) shipped 181 tons of gold out of the Americas, and 16,000 tons of silver. (These are some of the official numbers, but other sources estimate that as much as 20% more was collected and shipped out on the down-low. (It’s hard to stay honest, even if you want to, when you are collecting and shipping money.)

This would be worth today over 11 billion dollars. Doesn’t sound like much today, with multi-billion dollar governmental programs. But back then, it had a profound effect on even everyday life. As more precious metals came in, their value dropped. This cause inflation. One example is that between 1500 and 1650, inflation drove prices up 500%. In other words, in 1650, a loaf of bread cost 5 times as much as it did in 1500.

Of course, as it usually does, this left the poor in the lurch. Prices had risen, and landowners wanted to convert farmland into something that generated money. This involved throwing subsistence farmers off the land they had held for hundreds of years, which created a new class of homeless. These homeless men and women were then available to become cannon fodder in decades-long wars.

When the wars ran out, it left a generation that knew only fighting, and, in the case of sailors, capturing ships. These men, unemployed, became pirates.

So the pirates were made by gold, in many ways. In today’s world, with money becoming more and more concentrated in the hands of the few, and the ranks of the homeless increasing, I wonder what changes we may see coming in the world?

As we now know, Columbus was far from the first European to set foot in the Western Hemisphere. The Vikings had established colonies in Greenland and northern Canada, and had dealings with several native American tribes.

There is also evidence that Europeans fished the Grand Banks of Newfoundland for codfish long before Columbus made his fateful voyage. Fish and trade with Native Americans brought riches to those who dared to think outside the box. But these were working class riches. No kings lusted after codfish.

But on his first voyage, Columbus saw something to whet the appetite. Rowing out to meet him came natives… Nearly naked, rowing canoes, and wearing gold jewelry.

Gold jewelry was uncommon in Europe. Even nobility often didn’t own jewelry made of solid gold. In 1522, Anne Boleyn, child of a noble English family, educated in France, sent to be lady-in-waiting to England’s queen, brought with her only one piece of “gold” jewelry. It was really base metal, with a thin coating of gold, and the coating was visibly wearing off.

And in the Caribbean, half-naked “savages” wore jewelry of solid gold.

Needless to say, this excited the Powers That Be, and this effectively green-lit all subsequent voyages of exploration.

So why did the natives have gold?

Credit the Andes Mountains. Their geological formation has brought up many kinds of metal. Lead, copper, silver, and yes, gold, are abundant in the Andes.

Natives took these metals from streams that flowed out of the mountains. They liked the gold and silver, but only as a decorative material. They used it to make jewelry and to decorate statues and temples, but they did not make coins. The Carib, the Arawak, even the Incas used a barter system. They traded ducks for wool and thatched houses to pay their taxes.

One constant was that doing work for the Incan government was recorded, and could be “held” for years, being doled out to pay taxes or perhaps even traded for other goods. Sometimes the work that people did was to decorate public buildings or create statues. Gold was often used for these purposes.

The natives valued gold. It’s relatively easy to bring out of ore, it shines, and it does not ever tarnish. It’s also so soft that it’s easy to “work.” Gold can be pounded into a foil thinner than paper, or it can be shaped into cups, statues, and of course, jewelry.

But they didn’t value it more than beautiful bird feathers, or shiny shells, or other pretty things. Still, they had been picking up bits of gold that washed down from streams that began in the Andes for thousands of years. The Incas had a lot of gold.

So much that, when the Spanish conquistadores captures the Incan emperor, Atahualpa, he offered to fill a giant room half full of gold, and then fill it again twice with silver, if the Spanish would let him go. They agreed, not really believing him, and were shocked when the metal actually showed up. The gold alone, some 13,000 pounds of it, would be worth over two hundred and fifty Milliondollars today.

As the Spanish took over land in South America, they began to systematically mine gold. The mines were crude by modern standards, but they followed veins of gold, and produced the metal in near-industrial quantities. Between 1500 and 1650, the Spanish (officially) shipped 181 tons of gold out of the Americas, and 16,000 tons of silver. (These are some of the official numbers, but other sources estimate that as much as 20% more was collected and shipped out on the down-low. (It’s hard to stay honest, even if you want to, when you are collecting and shipping money.)

This would be worth today over 11 billion dollars. Doesn’t sound like much today, with multi-billion dollar governmental programs. But back then, it had a profound effect on even everyday life. As more precious metals came in, their value dropped. This cause inflation. One example is that between 1500 and 1650, inflation drove prices up 500%. In other words, in 1650, a loaf of bread cost 5 times as much as it did in 1500.

Of course, as it usually does, this left the poor in the lurch. Prices had risen, and landowners wanted to convert farmland into something that generated money. This involved throwing subsistence farmers off the land they had held for hundreds of years, which created a new class of homeless. These homeless men and women were then available to become cannon fodder in decades-long wars.

When the wars ran out, it left a generation that knew only fighting, and, in the case of sailors, capturing ships. These men, unemployed, became pirates.

So the pirates were made by gold, in many ways. In today’s world, with money becoming more and more concentrated in the hands of the few, and the ranks of the homeless increasing, I wonder what changes we may see coming in the world?

Published on May 15, 2017 19:24

May 8, 2017

Charleston, City of Pirates

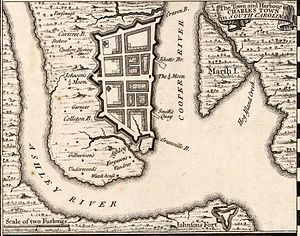

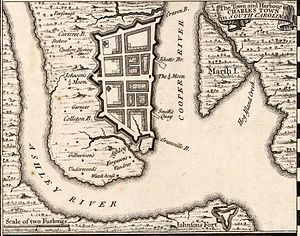

Founded in 1670, the city of Charleston is intimately linked to pirates and piracy. It has been raided repeatedly, is the fabled birthplace of the notorious Anne Bonny, and counts as part of its history a siege by Blackbeard that blockaded the port for nearly a week. In literature, it is the final resting place of Captain Flint, the legendary pirate from Treasure Island.

The colony was officially chartered as a colony in 1663, granted by King Charles of England to a group of men who had stood by the king during hard times. But it took 7 years, until 1670, to actually begin building a town.

Most of the original settlers came from Bermuda, brought to work in a colony that was supposed to be run more like a corporation than a government. The original site of the city was several miles from the current location, and the tiny settlement was called, not Charleston, but Charles Town, after the king.

The new settlement was under almost constant attack, from the local Natives, the French and Spanish, who were trying to claim the area for themselves. Pirates also attacked, and by 1680 a new city was planned – the first really planned city in the New World. Two things remain from the original town. “Pink House” – a genuinely pink residence, rumored to have been a boarding house for pirates who were in town selling their ill-gotten goods.

The old Powder House is also still standing. This structure housed, not people, but black powder for cannons.

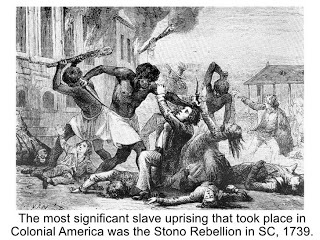

French, Scots-Irish, Scottish, Irish, and Germans migrated to the developing seacoast town, but Africans outnumbered them all. From very early times, slaves imported from Barbados and Native Americans captured and enslaved. During various times, the importation of slaves was outlawed. All free white men were required to carry guns – even in church. The point was to be ready in case of an uprising.

It’s been estimated that, between 1500 and 1864 (when slavery officially ended) that there were some 250 slave rebellion or revolts in North America. The earliest was while the territory was still under Spanish control, in 1526. This revolt was successful. Following a sickness that killed many of the Whites, the slave population rose up, and succeeded in breaking free and going out into the wilds to take up residence with the Native Americans.

In 1711, another bout of disease weakened the colonists, and a slave named Sebastian raised a small force, captured some guns, and kept the town in terror for weeks. He was finally killed by a hired “Indian Hunter."

Sickness was a persistent problem for the colony. Charleston has a humid subtropical climate. Smallpox, yellow fever and earthquakes (which then caused fires) plagued the city, which soon gained a reputation as the least healthy city in North America (though some would-be jet setters of time spent summers in Boston and winters in Charlestown.)

It was rumored that the African slaves were immune to yellow fever, but they initially caught it at roughly the same age of the Whites. Yet by 1750, most of the population seems to have become immune to the disease, so much so that people stopped calling it “yellow fever” and began to call it “the strangers disease.”

Anne Bonny is said to have been born in the town sometime around 1697. Although Charleston was the second-largest city in North America – Boston was bigger – it was still too small to support even a single full-time attorney. – under 6,000. Anne- then Anne Cormak – grew up living partially in town and partially at her attorney-father’s plantation.

Charlestown by this time sported one of the busiest ports in North America, and piracy was well-tolerated. Pirates needed to connect with people who had money in order to sell their stolen goods. The stolen articles provided a low-cost variety of goods to improve the lives of locals, while re-sale of goods enriched local merchants.

Part of the issue may be that the town had no town government. The original lords who had permission to found the settlement neglected to incorporate it. Later efforts to do so were thwarted by state officials, including the governor. The city was run by a hodge-podge of colony appointees and church officials.

Pirate House - or was it really?

Pirate House - or was it really?

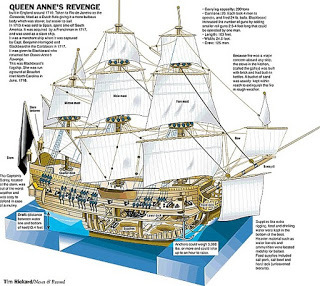

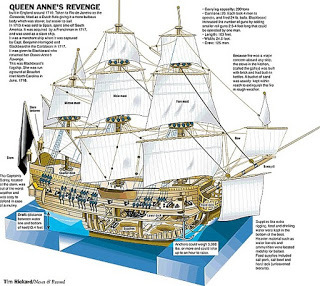

In late May 1718, Charles Town was besieged by Edward Teach, commonly known as "Blackbeard", for nearly a week. His pirates plundered merchant ships and seized a number of prominent people as hostages, while demanding a chest of medicine from Governor Robert Johnson. Once the pirates received it, they released their hostages, nearly naked and terrified.

Blackbeard sailed up the coast for North Carolina. The wreck of Blackbeard's flagship, the Queen Anne's Revenge, has since been discovered. Investigators have found what may be the contents of the medicine chest. Items include a urethral syringe (used to treat syphilis), pump clysters (used to provide enemas), a porringer (possibly for bloodletting), and a brass mortar and pestle for preparing medicine. Legend has always said that Blackbeard was looking for medicines and equipment to treat syphilis, likely caught by cavorting with prostitutes.

Today, Charleston shows off its heritage with art, music and a blending of cultures. English, French Huguenot, African and Southern American have created a vibrant culture that still shows off its piratical roots. Locations like Pirate House – a building that may or may not have hidden stolen goods, smugglers, and Blackbeard himself. Is any if it true? Probably not, but it’s fun to take the tour. Many places are also said the house the ghosts of pirates and their victims.

Pirate festivals crop up from time to time (this year’s is postponed due to renovation of the historic structure that hosts the fest) and you can walk the streets of the old city, which really felt the trod of pirates’ boots.

The colony was officially chartered as a colony in 1663, granted by King Charles of England to a group of men who had stood by the king during hard times. But it took 7 years, until 1670, to actually begin building a town.

Most of the original settlers came from Bermuda, brought to work in a colony that was supposed to be run more like a corporation than a government. The original site of the city was several miles from the current location, and the tiny settlement was called, not Charleston, but Charles Town, after the king.

The new settlement was under almost constant attack, from the local Natives, the French and Spanish, who were trying to claim the area for themselves. Pirates also attacked, and by 1680 a new city was planned – the first really planned city in the New World. Two things remain from the original town. “Pink House” – a genuinely pink residence, rumored to have been a boarding house for pirates who were in town selling their ill-gotten goods.

The old Powder House is also still standing. This structure housed, not people, but black powder for cannons.

French, Scots-Irish, Scottish, Irish, and Germans migrated to the developing seacoast town, but Africans outnumbered them all. From very early times, slaves imported from Barbados and Native Americans captured and enslaved. During various times, the importation of slaves was outlawed. All free white men were required to carry guns – even in church. The point was to be ready in case of an uprising.

It’s been estimated that, between 1500 and 1864 (when slavery officially ended) that there were some 250 slave rebellion or revolts in North America. The earliest was while the territory was still under Spanish control, in 1526. This revolt was successful. Following a sickness that killed many of the Whites, the slave population rose up, and succeeded in breaking free and going out into the wilds to take up residence with the Native Americans.

In 1711, another bout of disease weakened the colonists, and a slave named Sebastian raised a small force, captured some guns, and kept the town in terror for weeks. He was finally killed by a hired “Indian Hunter."

Sickness was a persistent problem for the colony. Charleston has a humid subtropical climate. Smallpox, yellow fever and earthquakes (which then caused fires) plagued the city, which soon gained a reputation as the least healthy city in North America (though some would-be jet setters of time spent summers in Boston and winters in Charlestown.)

It was rumored that the African slaves were immune to yellow fever, but they initially caught it at roughly the same age of the Whites. Yet by 1750, most of the population seems to have become immune to the disease, so much so that people stopped calling it “yellow fever” and began to call it “the strangers disease.”

Anne Bonny is said to have been born in the town sometime around 1697. Although Charleston was the second-largest city in North America – Boston was bigger – it was still too small to support even a single full-time attorney. – under 6,000. Anne- then Anne Cormak – grew up living partially in town and partially at her attorney-father’s plantation.

Charlestown by this time sported one of the busiest ports in North America, and piracy was well-tolerated. Pirates needed to connect with people who had money in order to sell their stolen goods. The stolen articles provided a low-cost variety of goods to improve the lives of locals, while re-sale of goods enriched local merchants.

Part of the issue may be that the town had no town government. The original lords who had permission to found the settlement neglected to incorporate it. Later efforts to do so were thwarted by state officials, including the governor. The city was run by a hodge-podge of colony appointees and church officials.

Pirate House - or was it really?

Pirate House - or was it really?In late May 1718, Charles Town was besieged by Edward Teach, commonly known as "Blackbeard", for nearly a week. His pirates plundered merchant ships and seized a number of prominent people as hostages, while demanding a chest of medicine from Governor Robert Johnson. Once the pirates received it, they released their hostages, nearly naked and terrified.

Blackbeard sailed up the coast for North Carolina. The wreck of Blackbeard's flagship, the Queen Anne's Revenge, has since been discovered. Investigators have found what may be the contents of the medicine chest. Items include a urethral syringe (used to treat syphilis), pump clysters (used to provide enemas), a porringer (possibly for bloodletting), and a brass mortar and pestle for preparing medicine. Legend has always said that Blackbeard was looking for medicines and equipment to treat syphilis, likely caught by cavorting with prostitutes.

Today, Charleston shows off its heritage with art, music and a blending of cultures. English, French Huguenot, African and Southern American have created a vibrant culture that still shows off its piratical roots. Locations like Pirate House – a building that may or may not have hidden stolen goods, smugglers, and Blackbeard himself. Is any if it true? Probably not, but it’s fun to take the tour. Many places are also said the house the ghosts of pirates and their victims.

Pirate festivals crop up from time to time (this year’s is postponed due to renovation of the historic structure that hosts the fest) and you can walk the streets of the old city, which really felt the trod of pirates’ boots.

Published on May 08, 2017 19:52

May 1, 2017

The Science of Writing in the 1700’s

Another tribute to science. Writing has often been the cutting edge of human technology. From the ancient Phoenicians, who invented writing by scratching tallies of their trade goods into slabs of clay, to the latest voice-recognizing, document transcribing software, writing is near the heart of human communication.

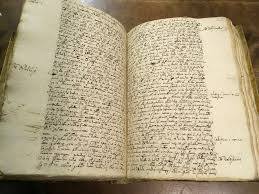

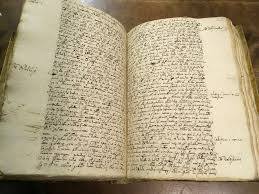

In the early 1700’s, most writing was done with a pen on paper. It sounds pretty normal, except that the pen was made out of a goose feather, and the paper… Well, that wasn’t quite the same as ours either.

Paper, as most of us know, was invented by the Chinese. In Europe, as soon as people had stopped using slabs of clay to write on, they had moved to parchment, or vellum. This was animal hide that had been treated, bleached and stretched thin – essentially super-thin leather. The advantages of this was that parchment didn’t need a lot of specialized equipment to make, and it was very durable. But it was expensive, and hard to make in large quantities.

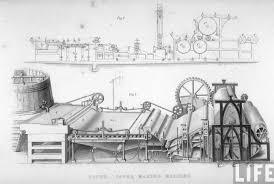

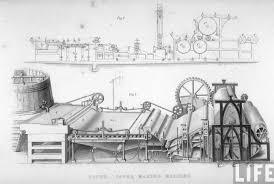

Paper making came to Europe through India and the Middle East. The first papermaking plant in Spain was built in 1056, and by 1692 the skill had reached all the way to Sweden.

The difference between parchment and paper is that paper is made from a variety of materials. Linen and cotton rags were pounded into pulp, then mixed with a glue-like substance and pressed into molds before being dried. This meant that paper could be made to specific sizes, with no waste. Later, paper mills were developed. Here, water powered a series of trip-hammers that quickly pulverized the raw materials.

Driven by a fresh need for writing materials, the development of paper was quick. By 1400, all paper was produced in paper mills, and had undergone dozens of improvements.

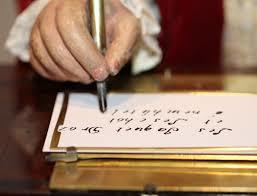

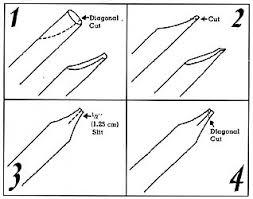

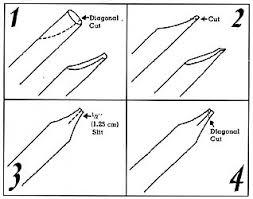

In 1700, a pen was a quill. What’s that? A quill in a feather, the large feathers from the wing tip of a goose or swan (and, later, a turkey.) The best feathers were the ones that had been shed normally in a process called molting, something that most birds go through every year.

The reason that a quill could be made into a pen was that it was a hollow tube. For a bird, the hollow shape gives lightness without sacrificing strength. For a human, the tube provides a delicate shape and flexible texture that technology at the time could not match.

Before quills, there had been reed pens. Reeds are also hollow, but they have less flexibility. They were wonderful for writing on slabs of clay, and perfectly fine for writing on parchment. But they dug into the soft new paper.

So pens made from quills became popular. They were used in the medieval period, and by 1600, efforts to write in a more elegant way meant that the technology of the quill superseded the technology of the reed.

Like reeds. Quills were carved into a point at the tip, and given a split up the middle. The hollow tube of the feather held the ink, the narrow point directed it, and the split allowed variations of pressure to control the width of the line.

The technology of the quill pen, with its flexible tip, hard point, and deep ink tube is so superior that some master-calligraphers still use them to do fine work on expensive paper.

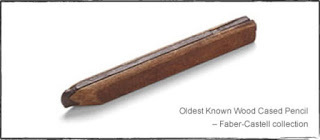

But the latest technology for writing in 1700 was the pencil.

Pencils did not exist before 1565. It was at about this time that a large deposit of graphite was found in England. The deposit was a large, solid block, and such a thing had never been found before. The science of chemistry was in its infancy, and the chemists of the day mistook the soft, grey metallic material for lead. This mistake – almost 500 years ago – is why we still call the material inside a pencil “lead.” Pencils have never written with lead.

The original pencils were simply sticks of graphite sawed from the original block. But it was quickly discovered that graphite had a much more valuable use. If graphite was rubbed inside the mold for a cannon ball, the finished ball would release much more easily. The English government took over the graphite mine and took out all the graphite they needed – then flooded the mine, to prevent anyone else from taking the graphite.

Meantime, people who wanted to write with a pencil wrapped their sticks of graphite with yarn, or sheepskin. The square sticks of graphite were only available in England, but early-adopters smuggled them to other countries in Europe.

Lacking the pure graphite of the one deposit in England, scientists began to try to find a way to make a pencil out of graphite dust. Germans worked on the earliest processes, which did not work very well. The Italians invented a process to encase a rod of graphite in wood, making a pencil that we would recognize today.

But it wasn’t until 1795, when Napoleonic France was utterly cutoff from English graphite, that graphite dust was mixed with clay to make the composition we know today.

In 1843, a method was developed to make paper from wood pulp, rather than cloth pulp. This gave a harder surface, which wore out quill pens at an alarming rate. It was only then that steel pen tips came into common use.

So that’s it, the technology of writing. Wonderful, modern things were happening in the Age of Piracy.

In the early 1700’s, most writing was done with a pen on paper. It sounds pretty normal, except that the pen was made out of a goose feather, and the paper… Well, that wasn’t quite the same as ours either.

Paper, as most of us know, was invented by the Chinese. In Europe, as soon as people had stopped using slabs of clay to write on, they had moved to parchment, or vellum. This was animal hide that had been treated, bleached and stretched thin – essentially super-thin leather. The advantages of this was that parchment didn’t need a lot of specialized equipment to make, and it was very durable. But it was expensive, and hard to make in large quantities.

Paper making came to Europe through India and the Middle East. The first papermaking plant in Spain was built in 1056, and by 1692 the skill had reached all the way to Sweden.

The difference between parchment and paper is that paper is made from a variety of materials. Linen and cotton rags were pounded into pulp, then mixed with a glue-like substance and pressed into molds before being dried. This meant that paper could be made to specific sizes, with no waste. Later, paper mills were developed. Here, water powered a series of trip-hammers that quickly pulverized the raw materials.

Driven by a fresh need for writing materials, the development of paper was quick. By 1400, all paper was produced in paper mills, and had undergone dozens of improvements.

In 1700, a pen was a quill. What’s that? A quill in a feather, the large feathers from the wing tip of a goose or swan (and, later, a turkey.) The best feathers were the ones that had been shed normally in a process called molting, something that most birds go through every year.

The reason that a quill could be made into a pen was that it was a hollow tube. For a bird, the hollow shape gives lightness without sacrificing strength. For a human, the tube provides a delicate shape and flexible texture that technology at the time could not match.

Before quills, there had been reed pens. Reeds are also hollow, but they have less flexibility. They were wonderful for writing on slabs of clay, and perfectly fine for writing on parchment. But they dug into the soft new paper.

So pens made from quills became popular. They were used in the medieval period, and by 1600, efforts to write in a more elegant way meant that the technology of the quill superseded the technology of the reed.

Like reeds. Quills were carved into a point at the tip, and given a split up the middle. The hollow tube of the feather held the ink, the narrow point directed it, and the split allowed variations of pressure to control the width of the line.

The technology of the quill pen, with its flexible tip, hard point, and deep ink tube is so superior that some master-calligraphers still use them to do fine work on expensive paper.

But the latest technology for writing in 1700 was the pencil.

Pencils did not exist before 1565. It was at about this time that a large deposit of graphite was found in England. The deposit was a large, solid block, and such a thing had never been found before. The science of chemistry was in its infancy, and the chemists of the day mistook the soft, grey metallic material for lead. This mistake – almost 500 years ago – is why we still call the material inside a pencil “lead.” Pencils have never written with lead.

The original pencils were simply sticks of graphite sawed from the original block. But it was quickly discovered that graphite had a much more valuable use. If graphite was rubbed inside the mold for a cannon ball, the finished ball would release much more easily. The English government took over the graphite mine and took out all the graphite they needed – then flooded the mine, to prevent anyone else from taking the graphite.

Meantime, people who wanted to write with a pencil wrapped their sticks of graphite with yarn, or sheepskin. The square sticks of graphite were only available in England, but early-adopters smuggled them to other countries in Europe.

Lacking the pure graphite of the one deposit in England, scientists began to try to find a way to make a pencil out of graphite dust. Germans worked on the earliest processes, which did not work very well. The Italians invented a process to encase a rod of graphite in wood, making a pencil that we would recognize today.

But it wasn’t until 1795, when Napoleonic France was utterly cutoff from English graphite, that graphite dust was mixed with clay to make the composition we know today.

In 1843, a method was developed to make paper from wood pulp, rather than cloth pulp. This gave a harder surface, which wore out quill pens at an alarming rate. It was only then that steel pen tips came into common use.

So that’s it, the technology of writing. Wonderful, modern things were happening in the Age of Piracy.

Published on May 01, 2017 18:20

April 24, 2017

Pirates and the Dawn of Science

In honor of Earth Day and the March for Science, we’re going to take a look at science in the early 1700’s. With an emphasis on pirates, of course.

This was the time period called “The Enlightenment.” After the Dark Ages, centuries when Europeans barely kept hold of the knowledge of ancient times, let alone created new knowledge or understanding of the world around them,

Some place the beginning of the enlightenment as late as 1715, others as early as 1620. It was based on the Science played an important role in Enlightenment discourse and thought. Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the sciences. They associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion and traditional authority in favor of the development of free speech and thought.

In many ways, this was a result of the printing press, greater literacy (at least among the wealthy) and a wider spread of knowledge. When human understanding of the world’s workings were confined to small enclaves, largely controlled by religious institutions, the words of old philosophers can be handed down as immutable fact. When many people can read, and communicate their ideas with each other, people can begin to question things that don’t line up with their observations.

For centuries, Aristotle and the Bible had agreed that Earth was the center of the universe. Galileo Galilei observed the motion of the moon (as revealed by tides), the phases of Venus, and the orbit of Jupiter’s moon, and determined that Earth orbits the Sun. This was a radical notion, and it got Galileo in a great deal of trouble. The old ways do not die easy.

(And a note, here. Neither pirates nor anyone else believed that the earth was flat. The ancient Greeks had proved its spherical shape, and had measured its diameter to a highly accurate degree. Sailors saw regularly that, as their ships traveled, land seemed to rise and sink from the ocean. Stories of monsters and falling off the edge were drunken bravado and tales for land-lubbers.)

However, as the dates in the third paragraph indicate, the Golden Age of Piracy falls in the beginning of this age of Reason. While the idea of “science” was catching on, it was still largely the thought-playground of the rich.

Take medicine. Our pirate friends, along with everyone else from Europe, still believed that disease was caused by “bad air” or “bad water.” Even the idea sickness could be transmitted directly from one human to another was radical. Germ theory was over a hundred years off. Even the idea that dirt causes sickness was not established.

Because of this, the most common form of treatment for sickness was trying to bring the “humors of the body” into balance. This was most often done by bleeding, or by giving the patient herbs or drugs that caused intense vomiting or diarrhea. The fact that a sudden loss of blood can end a fever, or temporarily treat high blood pressure, and violent intestinal spasms can drive out parasites, only muddied the issue.

Cleanliness was regarded with suspicion. The Protestant Churches (official religions of England and the Netherlands) discouraged washing as “worldly”. Most people lived in filth that would be difficult for a modern person to believe. In addition to not washing, they drank water straight from lakes and rivers, even if those contained raw sewage and decomposing animals.

Today, we can credit science with not only with understanding that germs are dangerous, and teaching us how to kill them, but with discovering other dangers in life. The 18th century was awash with alcohol – children drank liquor as soon as they were weaned. Mothers drank throughout pregnancy.

And of the other dangers, the most prevalent was lead. Today science has taught us that lead is a dangerous substance. Ingesting it can be deadly, and even touching it with bare skin can damage the brain. In the 18thcentury, the world was awash in lead. Lead water pipes, lead-based paint, lead based makeup. Sheets of lead were a common material, used for a variety of things. Pirates wrapped scraps of sheet lead around the flints in their guns, to better fit them into the screw-hold of the hammer. Every time I think of the lead being handled by common pirates and sailors, I wonder how many IQ points it cost them.

A pistol flint with its base wrapped in lead

A pistol flint with its base wrapped in lead

Anything resembling the practice of birth control was believed to be a sin against God. Women in Europe gave birth to a dozen or more children in their lives. This was necessary, however, since as many as a third of infants did not make it to their second year. The women, worn out by childbearing, died young. Today, women outnumber men. In the 18thcentury, there was a shortage of older women.

Capitalism was in its infancy. The old system of medieval feudalism had broken down. Land was increasingly held by a small number of the rich. Under the old feudal system, everyone was entitled to work, a home and a place in society. But as new lands were explored (This era is also called the Age of Exploration) and new products came to market, the rich wanted cash.

In the new spirit of understanding the world as a mechanism, understandable to the human mind, the owners of “capital” saw human labor as if people were machines. Employees were work-producing units, and employers had no more responsibility to the workers they employed than to the animals they owned, or the carts pulled by those animals.

So, while the place of the educated man was seen as being semi-divine, capable of grasping the very workings of the universe, the working class, the uneducated, were viewed as little more than animals.

This was what the pirates were fighting. In a changing world, the place of the working class was being pushed down, money was becoming more important, and human rights were failing, pirates struck out against the immediate cause of their oppression. Their leadership may have heard the stirrings of change… Humans were not locked into their place in the economic ladder. God had not ordained what a man did with his life. The pirates chose to stand up, and try to change the world.

This was the time period called “The Enlightenment.” After the Dark Ages, centuries when Europeans barely kept hold of the knowledge of ancient times, let alone created new knowledge or understanding of the world around them,

Some place the beginning of the enlightenment as late as 1715, others as early as 1620. It was based on the Science played an important role in Enlightenment discourse and thought. Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the sciences. They associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion and traditional authority in favor of the development of free speech and thought.

In many ways, this was a result of the printing press, greater literacy (at least among the wealthy) and a wider spread of knowledge. When human understanding of the world’s workings were confined to small enclaves, largely controlled by religious institutions, the words of old philosophers can be handed down as immutable fact. When many people can read, and communicate their ideas with each other, people can begin to question things that don’t line up with their observations.

For centuries, Aristotle and the Bible had agreed that Earth was the center of the universe. Galileo Galilei observed the motion of the moon (as revealed by tides), the phases of Venus, and the orbit of Jupiter’s moon, and determined that Earth orbits the Sun. This was a radical notion, and it got Galileo in a great deal of trouble. The old ways do not die easy.

(And a note, here. Neither pirates nor anyone else believed that the earth was flat. The ancient Greeks had proved its spherical shape, and had measured its diameter to a highly accurate degree. Sailors saw regularly that, as their ships traveled, land seemed to rise and sink from the ocean. Stories of monsters and falling off the edge were drunken bravado and tales for land-lubbers.)

However, as the dates in the third paragraph indicate, the Golden Age of Piracy falls in the beginning of this age of Reason. While the idea of “science” was catching on, it was still largely the thought-playground of the rich.

Take medicine. Our pirate friends, along with everyone else from Europe, still believed that disease was caused by “bad air” or “bad water.” Even the idea sickness could be transmitted directly from one human to another was radical. Germ theory was over a hundred years off. Even the idea that dirt causes sickness was not established.

Because of this, the most common form of treatment for sickness was trying to bring the “humors of the body” into balance. This was most often done by bleeding, or by giving the patient herbs or drugs that caused intense vomiting or diarrhea. The fact that a sudden loss of blood can end a fever, or temporarily treat high blood pressure, and violent intestinal spasms can drive out parasites, only muddied the issue.

Cleanliness was regarded with suspicion. The Protestant Churches (official religions of England and the Netherlands) discouraged washing as “worldly”. Most people lived in filth that would be difficult for a modern person to believe. In addition to not washing, they drank water straight from lakes and rivers, even if those contained raw sewage and decomposing animals.

Today, we can credit science with not only with understanding that germs are dangerous, and teaching us how to kill them, but with discovering other dangers in life. The 18th century was awash with alcohol – children drank liquor as soon as they were weaned. Mothers drank throughout pregnancy.

And of the other dangers, the most prevalent was lead. Today science has taught us that lead is a dangerous substance. Ingesting it can be deadly, and even touching it with bare skin can damage the brain. In the 18thcentury, the world was awash in lead. Lead water pipes, lead-based paint, lead based makeup. Sheets of lead were a common material, used for a variety of things. Pirates wrapped scraps of sheet lead around the flints in their guns, to better fit them into the screw-hold of the hammer. Every time I think of the lead being handled by common pirates and sailors, I wonder how many IQ points it cost them.

A pistol flint with its base wrapped in lead

A pistol flint with its base wrapped in leadAnything resembling the practice of birth control was believed to be a sin against God. Women in Europe gave birth to a dozen or more children in their lives. This was necessary, however, since as many as a third of infants did not make it to their second year. The women, worn out by childbearing, died young. Today, women outnumber men. In the 18thcentury, there was a shortage of older women.

Capitalism was in its infancy. The old system of medieval feudalism had broken down. Land was increasingly held by a small number of the rich. Under the old feudal system, everyone was entitled to work, a home and a place in society. But as new lands were explored (This era is also called the Age of Exploration) and new products came to market, the rich wanted cash.

In the new spirit of understanding the world as a mechanism, understandable to the human mind, the owners of “capital” saw human labor as if people were machines. Employees were work-producing units, and employers had no more responsibility to the workers they employed than to the animals they owned, or the carts pulled by those animals.

So, while the place of the educated man was seen as being semi-divine, capable of grasping the very workings of the universe, the working class, the uneducated, were viewed as little more than animals.

This was what the pirates were fighting. In a changing world, the place of the working class was being pushed down, money was becoming more important, and human rights were failing, pirates struck out against the immediate cause of their oppression. Their leadership may have heard the stirrings of change… Humans were not locked into their place in the economic ladder. God had not ordained what a man did with his life. The pirates chose to stand up, and try to change the world.

Published on April 24, 2017 20:15

April 18, 2017

Food of the Enslaved

Food of the Enslaved

The food of Black Slaves in the Caribbean affected the cuisine of the pirates 300 years ago, and its influence has continued, becoming an integral part of the cuisines of both the Caribbean and Southern America.

When slaves were first taken from Africa. African foods came with them. This was done by the salve=traders, not out of any form of compassion, but because their cargo, kidnapped, shocked, and grieving, often refused to eat unfamiliar foods. Okra, yams, and peanuts, and more were brought with the slaves.

Having arrived in the New World, African cooks began to use local foods in their cooking. Often, their own food was made from the leftovers or unwanted parts of the owner’s food. Organ meats (hog maw, or the stomach lining of a pig,) vied with chitterlings (the cleaned intestines of the pig) as a popular protein. Less-desireable meats like fatback and hog jowls were also popular.

Various types of beans, often paired with rice, were popular in North African cuisine, and were carried into the Americas. Following is a recipe for a bean-themed snack called Akara.

Akara

2 cups of black-eyes peas1 medium-sized onion, choppedParsley and spices to tasteFat for seep frying

Put the dried peas into a mortar and grind them until they are about the consistency of coarse coffee grounds. Add finely chopped onion and continue to grind. Add spices – parsley, and perhaps some hot peppers, and grind until it is a consistent texture.

Add boiling water to make a thick paste. Allow to sit for several minutes.

While the bean paste is resting, pour oil into a frying pan to a depth of about 1” and heat. To cook – drop spoonful’s of the bean mixture into the hot oil and fry until golden brown.

Once drained and cooled, these bean cakes can be eaten by hand.

Enslaved Africans also sometimes had access to leftovers from their owners’ tables. The following recipe is based on a type of African “falafel” that originated among African Muslims from the area of Senegal. It incorporates Northern African flavors.

Kush

About 4 cups of stale cornbread.1 medium sized onion, choppedDried sage, rosemary, thyme and red pepper to tasteFat for frying (butter or lard)

Put the spices into the bowl with the chopped onion to re-hydrate for a few moments, using the onion juice.

Crumble cornbread into the bowl with the onion and spices. Knead together. If the mixture seems too dry, you may wish to incorporate a small amount of water or broth. Fry the mixture on a pan liberally greased with butter, lard, or bacon grease.

The finished product should be similar to stuffing.

Okra is a vegetable of African origins, having probably originated in or around Ethiopia. The vegetable was often fried, or made into soups or stews. In Africa, the seeds were also toasted and served as snacks. It was brought to the Caribbean as early as the 1600’s, and traveled to the American South from there. Deep-fried okra is popular today, but had not yet been invented at the time of the pirates.

Okra Soup

4 cups of okra, sliced thin4 cups of diced onion3 cloves of garlic, coarse choppedFlour for dredgingButter or lard for frying4 medium tomatoesAbout 8 cups rich broth.

(Note: in the 18th century, many Europeans were afraid to eat tomatoes, because they are members of the nightshade family, and presumed to be poisonous. North Africans, however, had already figured out how wonderful tomatoes are, and ate them regularly.)

Create a rich stock from a mix of chicken and beef, and add rosemary, thyme and sage. Stud an onion with cloves and add to the stock. Boil for at least an hour. Then remove and discard the onion and cloves.

Mix the onion and garlic, dredge in flour, and fry in fat until soft and beginning to brown.Add to the stock and simmer. Add the sliced okra. Chop and add the tomatoes. Simmer for 1 hour.

You may add some chopped protein – pork or turkey – while the soup is cooking.

Three great recipes, based on African foods and firmly rooted in the slave culture of the 1700’s. Any pirate would be pleased to eat such delicious dishes – and many of them probably did.

This post is strongly influenced by the series “Food of theEnslaved” on Jas. Townsend and Son’s YouTube Channel, featuring Michael Twitty, a food historian.

The food of Black Slaves in the Caribbean affected the cuisine of the pirates 300 years ago, and its influence has continued, becoming an integral part of the cuisines of both the Caribbean and Southern America.

When slaves were first taken from Africa. African foods came with them. This was done by the salve=traders, not out of any form of compassion, but because their cargo, kidnapped, shocked, and grieving, often refused to eat unfamiliar foods. Okra, yams, and peanuts, and more were brought with the slaves.

Having arrived in the New World, African cooks began to use local foods in their cooking. Often, their own food was made from the leftovers or unwanted parts of the owner’s food. Organ meats (hog maw, or the stomach lining of a pig,) vied with chitterlings (the cleaned intestines of the pig) as a popular protein. Less-desireable meats like fatback and hog jowls were also popular.

Various types of beans, often paired with rice, were popular in North African cuisine, and were carried into the Americas. Following is a recipe for a bean-themed snack called Akara.

Akara

2 cups of black-eyes peas1 medium-sized onion, choppedParsley and spices to tasteFat for seep frying

Put the dried peas into a mortar and grind them until they are about the consistency of coarse coffee grounds. Add finely chopped onion and continue to grind. Add spices – parsley, and perhaps some hot peppers, and grind until it is a consistent texture.

Add boiling water to make a thick paste. Allow to sit for several minutes.

While the bean paste is resting, pour oil into a frying pan to a depth of about 1” and heat. To cook – drop spoonful’s of the bean mixture into the hot oil and fry until golden brown.

Once drained and cooled, these bean cakes can be eaten by hand.

Enslaved Africans also sometimes had access to leftovers from their owners’ tables. The following recipe is based on a type of African “falafel” that originated among African Muslims from the area of Senegal. It incorporates Northern African flavors.

Kush

About 4 cups of stale cornbread.1 medium sized onion, choppedDried sage, rosemary, thyme and red pepper to tasteFat for frying (butter or lard)

Put the spices into the bowl with the chopped onion to re-hydrate for a few moments, using the onion juice.

Crumble cornbread into the bowl with the onion and spices. Knead together. If the mixture seems too dry, you may wish to incorporate a small amount of water or broth. Fry the mixture on a pan liberally greased with butter, lard, or bacon grease.

The finished product should be similar to stuffing.

Okra is a vegetable of African origins, having probably originated in or around Ethiopia. The vegetable was often fried, or made into soups or stews. In Africa, the seeds were also toasted and served as snacks. It was brought to the Caribbean as early as the 1600’s, and traveled to the American South from there. Deep-fried okra is popular today, but had not yet been invented at the time of the pirates.

Okra Soup

4 cups of okra, sliced thin4 cups of diced onion3 cloves of garlic, coarse choppedFlour for dredgingButter or lard for frying4 medium tomatoesAbout 8 cups rich broth.

(Note: in the 18th century, many Europeans were afraid to eat tomatoes, because they are members of the nightshade family, and presumed to be poisonous. North Africans, however, had already figured out how wonderful tomatoes are, and ate them regularly.)

Create a rich stock from a mix of chicken and beef, and add rosemary, thyme and sage. Stud an onion with cloves and add to the stock. Boil for at least an hour. Then remove and discard the onion and cloves.

Mix the onion and garlic, dredge in flour, and fry in fat until soft and beginning to brown.Add to the stock and simmer. Add the sliced okra. Chop and add the tomatoes. Simmer for 1 hour.

You may add some chopped protein – pork or turkey – while the soup is cooking.

Three great recipes, based on African foods and firmly rooted in the slave culture of the 1700’s. Any pirate would be pleased to eat such delicious dishes – and many of them probably did.

This post is strongly influenced by the series “Food of theEnslaved” on Jas. Townsend and Son’s YouTube Channel, featuring Michael Twitty, a food historian.

Published on April 18, 2017 19:38

April 10, 2017

The Pirate Attack on Veracruz

One of the final actions of the Age of Buccaneering Pirates was the Attack on Veracruz, which took place in 1683. The attack includes spies, deception, forced marches through the south American jungle, a duel and a band of intrepid Dutch pirates.

First among them was Laurens de Graaf, a man of mysterious origins. Rumored to be a Spanish slave of African ancestry, de Graaf was captaining a French privateer and dabbling in piracy as early as 1670. Even before this, he is said to have been part of a raiding party that attacked the Mexican region of Campeche. The pirates successful captured the town, and burned a warship that was undergoing construction.

Then in a mad turn of fate, a merchant ship sailed into the harbor, unaware that it was in the hands of pirates. The pirates, who had already looted the town, took another 120,000 pesos in silver and goods.

By 1682, de Graaf was so famous that Sir Henry Morgan, once a famous buccaneer and now Governor of Jamaica, sent the frigate Norwich to hunt him down.

The Spanish were even more determined to end de Graaf’s career. They gathered a small armada, led by the war ship Princessa to get revenge for his raids. De Graaf sailed out the meet the Princessa and defeated her in a fight that took 50 Spanish lives. De Graaf had lost only 8 of his own men, and was kind enough to put the badldy wounded Spansih commander ashore with his servants and surgeon. De Graff then took the Princessa as his flagship, renaming her the Francesca, after his wife.

Nicholas van Hoorn had been a merchant sailor before becoming a pirate. Van Hoorn was engaged in the Dutch merchant service from about 1655 until 1659, and then bought a vessel with his savings.

Originally working as a privateer by the French against the Spanish, van Hoorn eventually quarreled with his employers and turned to the Spanish for help. He entered a New-World Spanish port as two huge galleons were being loaded and begged for the protection of the Spanish. He was persuasive enough that he was hired to protect the two galleons on their journey back to Spain. He immediately attacked and looted the galleons, taking 2,000,000 livres of silver, then headed out to Africa to loot the locals and join the slave trade.

By 1682, he and his flagship, the Saint Nicholas's Day, were wanted by the French, the English, and the Spanish.

Chevalier de Grammont was a French nobleman pirate, who was first run out of France for killing a man in a duel. He served the French navy in the Caribbean, and won the title of “pirate” by attacking and raiding Spanish settlements during peacetime.

[image error]

In 1682, at the request of the governor of Haiti, he joined Nicholas van Hoorn to harass Spanish shipping. De Grammont had always had s checkered career, full of incredible victories and embarrassing failures. (Among these – running his second command aground, and taking part in a fleet action that ended when all 17 vessels were wrecked.)

Together de Grammont and van Hoorn attacked several ships which, unknown to them, belonged to Laurens de Graaf. This led to a meeting with de Graaf on Bonaco Island. De Grammont and van Hoorn were so impressed that they asked de Graaf to join them. De Graaf refused at first, but later changed his mind when he was called upon to contribute manpower for a daring plan. They wanted to attack and sack the Spanish city of Veracruz.

On the 17th of May,1683 the pirates arrived off the coast of Veracruz. Their fleet included 5 large vessels, 8 smaller vessels and around 1300 pirates. At its head sailed two Spanish ships, possibly the galleons previously captured by van Hoorn. The plan was to confuse the townsfolk into thinking the fleet was Spanish.

While the fleet was anchored offshore, de Graaf set out in longboats and landed some distance from the town. He and his men waited until early the following morning. Then, while most of the town's militia were sleeping, they attacked and disabled the town's fortifications. This allowed van Hoorn and his group of pirates, who had marched overland, to enter the city and take out the remaining defenses. Together, the pirates sacked the town and took a large number of hostages including the town's governor.

As the pirates entered the second day of plundering, the Spanish fleet, with a large number of warships, appeared on the horizon. The pirates secured their hostages and retreated to the nearby Isla de Sacrificios. They intended to threaten the lives of these important men, and demanded ransoms.

When payments did not arrive immediately, Van Hoorn ordered the execution of a dozen prisoners. In a shocking display, he then had their heads sent to Veracruz as a warning.

De Graaf was furious. The two argued, the issue came to blows, and they arranged and fought a duel. De Graaf won - Van Hoorn received a slash across the wrist and was taken back to his ship in shackles. This was the 17th century, and even a small wound could be dangerous. The slash soon became infected, which led to gangrene, and Van Hoorn died.

The ransoms still did not come. Finally, giving up on further plunder, the pirates left the island, slipping past the Spanish without hindrance.

In July 1685, de Grammont and de Graaf sacked the Mexican city of Campeche: however, after two months of plundering the city with little result, de Grammont sent a demand for ransom to the governor, who refused. De Grammont then began to execute prisoners, but de Graaf stopped the killings and he and de Grammont parted ways.

De Grammont was last seen in April 1686 sailing northeast direction from of St. Augustine, Florida. His ship was reported lost with all hands in a storm shortly after he set sail.

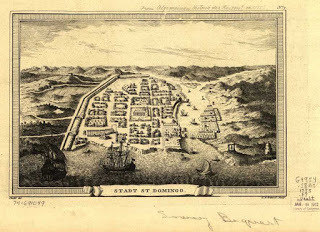

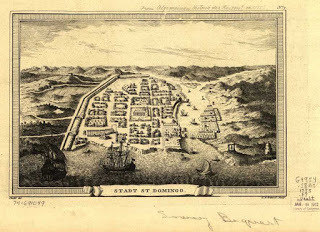

De Graaf continued to fight the Spanish, the English and local governments. He blockaded the coast of Jamaica for six months, then attacked Santo Domingo. Here he met forces three times the size of his own, and was soundly defeated. He narrowly escaped with his life.

In March 1693, a woman named Anne Dieu-le-Veut threatened to shoot de Graaf, because she claimed he had insulted her. He apologized and married her. He then spent the summer leading buccaneers against Jamaica in several raids. The English retaliated in May 1695 and captured de Graaf's family.

Laurens de Graff was last known to be near Louisiana, where he was to help set up a French colony near present-day Biloxi, Mississippi. Some sources say he died there; others claim locations in Alabama. He would have been about 42 years old.

First among them was Laurens de Graaf, a man of mysterious origins. Rumored to be a Spanish slave of African ancestry, de Graaf was captaining a French privateer and dabbling in piracy as early as 1670. Even before this, he is said to have been part of a raiding party that attacked the Mexican region of Campeche. The pirates successful captured the town, and burned a warship that was undergoing construction.

Then in a mad turn of fate, a merchant ship sailed into the harbor, unaware that it was in the hands of pirates. The pirates, who had already looted the town, took another 120,000 pesos in silver and goods.

By 1682, de Graaf was so famous that Sir Henry Morgan, once a famous buccaneer and now Governor of Jamaica, sent the frigate Norwich to hunt him down.

The Spanish were even more determined to end de Graaf’s career. They gathered a small armada, led by the war ship Princessa to get revenge for his raids. De Graaf sailed out the meet the Princessa and defeated her in a fight that took 50 Spanish lives. De Graaf had lost only 8 of his own men, and was kind enough to put the badldy wounded Spansih commander ashore with his servants and surgeon. De Graff then took the Princessa as his flagship, renaming her the Francesca, after his wife.

Nicholas van Hoorn had been a merchant sailor before becoming a pirate. Van Hoorn was engaged in the Dutch merchant service from about 1655 until 1659, and then bought a vessel with his savings.

Originally working as a privateer by the French against the Spanish, van Hoorn eventually quarreled with his employers and turned to the Spanish for help. He entered a New-World Spanish port as two huge galleons were being loaded and begged for the protection of the Spanish. He was persuasive enough that he was hired to protect the two galleons on their journey back to Spain. He immediately attacked and looted the galleons, taking 2,000,000 livres of silver, then headed out to Africa to loot the locals and join the slave trade.

By 1682, he and his flagship, the Saint Nicholas's Day, were wanted by the French, the English, and the Spanish.

Chevalier de Grammont was a French nobleman pirate, who was first run out of France for killing a man in a duel. He served the French navy in the Caribbean, and won the title of “pirate” by attacking and raiding Spanish settlements during peacetime.

[image error]

In 1682, at the request of the governor of Haiti, he joined Nicholas van Hoorn to harass Spanish shipping. De Grammont had always had s checkered career, full of incredible victories and embarrassing failures. (Among these – running his second command aground, and taking part in a fleet action that ended when all 17 vessels were wrecked.)

Together de Grammont and van Hoorn attacked several ships which, unknown to them, belonged to Laurens de Graaf. This led to a meeting with de Graaf on Bonaco Island. De Grammont and van Hoorn were so impressed that they asked de Graaf to join them. De Graaf refused at first, but later changed his mind when he was called upon to contribute manpower for a daring plan. They wanted to attack and sack the Spanish city of Veracruz.

On the 17th of May,1683 the pirates arrived off the coast of Veracruz. Their fleet included 5 large vessels, 8 smaller vessels and around 1300 pirates. At its head sailed two Spanish ships, possibly the galleons previously captured by van Hoorn. The plan was to confuse the townsfolk into thinking the fleet was Spanish.

While the fleet was anchored offshore, de Graaf set out in longboats and landed some distance from the town. He and his men waited until early the following morning. Then, while most of the town's militia were sleeping, they attacked and disabled the town's fortifications. This allowed van Hoorn and his group of pirates, who had marched overland, to enter the city and take out the remaining defenses. Together, the pirates sacked the town and took a large number of hostages including the town's governor.

As the pirates entered the second day of plundering, the Spanish fleet, with a large number of warships, appeared on the horizon. The pirates secured their hostages and retreated to the nearby Isla de Sacrificios. They intended to threaten the lives of these important men, and demanded ransoms.

When payments did not arrive immediately, Van Hoorn ordered the execution of a dozen prisoners. In a shocking display, he then had their heads sent to Veracruz as a warning.

De Graaf was furious. The two argued, the issue came to blows, and they arranged and fought a duel. De Graaf won - Van Hoorn received a slash across the wrist and was taken back to his ship in shackles. This was the 17th century, and even a small wound could be dangerous. The slash soon became infected, which led to gangrene, and Van Hoorn died.

The ransoms still did not come. Finally, giving up on further plunder, the pirates left the island, slipping past the Spanish without hindrance.

In July 1685, de Grammont and de Graaf sacked the Mexican city of Campeche: however, after two months of plundering the city with little result, de Grammont sent a demand for ransom to the governor, who refused. De Grammont then began to execute prisoners, but de Graaf stopped the killings and he and de Grammont parted ways.

De Grammont was last seen in April 1686 sailing northeast direction from of St. Augustine, Florida. His ship was reported lost with all hands in a storm shortly after he set sail.

De Graaf continued to fight the Spanish, the English and local governments. He blockaded the coast of Jamaica for six months, then attacked Santo Domingo. Here he met forces three times the size of his own, and was soundly defeated. He narrowly escaped with his life.

In March 1693, a woman named Anne Dieu-le-Veut threatened to shoot de Graaf, because she claimed he had insulted her. He apologized and married her. He then spent the summer leading buccaneers against Jamaica in several raids. The English retaliated in May 1695 and captured de Graaf's family.

Laurens de Graff was last known to be near Louisiana, where he was to help set up a French colony near present-day Biloxi, Mississippi. Some sources say he died there; others claim locations in Alabama. He would have been about 42 years old.

Published on April 10, 2017 19:35

April 3, 2017

Guillaume Le Testu, French Buccaneer

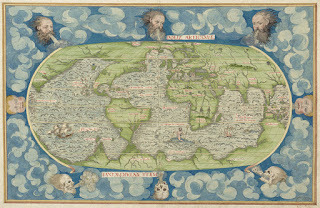

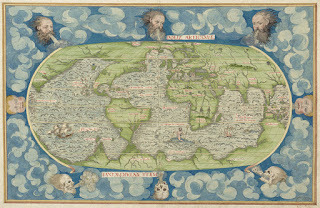

Guillaume le Testu was a French explorer, mapmaker, and sometime pirate, back in the days of the Buccaneers.

He was born sometime around 1509–12, and became one of the last pupils to be taught cartography at the famous school of Dieppe. Because of his mapmaking skills, Le Testu took part in voyages of exploration all through the Atlantic Ocean.

In 1550, Le Testu was commissioned by the king of France to create a map of the Americas. It was a dangerous mission, because at the time, knowledge of the landscape of the region was something of a military secret, held by Spain and Portugal. Le Testu charted areas as far as Rio de Janeiro, when he was attacked by the Portuguese and took heavy damage to his ship.

In 1555, Le Testu published a world atlas, and received an award from the King for his work. The book contained 56 maps, based on charts Le Testu had drawn by hand on his expeditions. This atlas was dedicated to his mentor and patron Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, who had become leader of the Huguenots three years earlier.

Interestingly enough, the work also contains a chart of Australia, which Le Testu called “Java Major.” The area of the map near the as-yet undiscovered continent contains drawings of what may be a black swan and a cassowary, birds native to Australia. It is notated as follows:

The present Figure contains … La Grant Jave [Java Major], and La Petite Jave [Java Minor] in which there are eight Kingdoms. The men of these two Countries are Idolaters and wicked. Several manner of spices grow in these two Regions, such as Nutmeg, Cloves, and other spices... This Land is part of the so-called Terra Australis, to us Unknown, so that which is marked herein is only from Imagination and uncertain opinion; for some say that La Grant Jave which is the eastern Coast of it is the same land of which the western Coast forms the Strait of Magellan, and that all of this land is joined together...

This Part is the same Land of the south called Austral, which has never yet been discovered, for there is no account of anyone having yet found it, and therefore nothing has been remarked of it but from Imagination. I have not been able to describe any of its resources, and for this reason I leave speaking further of it until more ample discovery has been made, and as much as I have written and annoted names to several of its capes this has only been to align the pieces depicted herein to the views of others and also so that those who navigate there be on their guard when they are of opinion that they are approaching the said Land...

Le Testu’s career was temporarily halted by the French Wars of Religion. The mid-1500’s to the mid 1600’s were a time of civil and religious upheaval. In France, this took the form of civil wars between the Huguenots (Protestant reformers) and Catholics. (Catholicism being the official religion of France.) Le Testu, who had been mentored by a member of the Huguenot cause, sided with the Huguenots. This was his entry into piracy. He conducted privateering raids for two years, but was eventually captured by the Catholics.

However, his service to France as a mapmaker came to his rescue. After four years of imprisonment, he was released by order of King Charles IX.

Francis Drake

Francis Drake

Le Testu went back to sea, perhaps aiming to improve his maps. On March 23, 1573, he bumped into Sir Francis Drake near Cativá, Panama. Drake shared news of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, an attack by the French King, a Catholic, that killed many French Huguenot nobles. (Estimates range from 5,000 to 30,000 dead.) Upon learning of this, Le Testu offered to join Drake in a raid against the (Catholic) Spanish. Drake intended to attack the mule train carrying treasure to the city of Nombre de Dios where galleons would pick it up for transport to Spain.

Drake and Le Testu sailed their combined fleet to Panama. They landed with their men just east of Nombre de Dios. Le Testu had 70 men under his command while Drake himself led only 31. As their ships sailed off, with orders to return for them in four days, the party headed inland to a spot south of the city, where they waited for the Spanish mule train.

Soon after their arrival the pirates heard bells in the distance – the bells on the Spanish pack mules. Scouts reported that the caravan consisted of almost 200 mules, each carrying up to three hundred pounds of treasure. Drake had chosen the spot for the ambush, believing the Spaniards to be at their most vulnerable as they were nearing their destination, having traveled through miles of jungle.

The attack was a complete success. Together Drake and Le Testu captured nearly 30 tons of gold and silver. There was so much treasure that the privateers were unable carry all the silver off and buried what remained. (This may be one origin of the legends of buried treasure.)

However, Le Tetsu was seriously wounded during the first assault. He was forced to rest by the roadside until he was able to travel. Two of his men stayed at his side.

The rest of the party continued onward. to meet the scheduled rendezvous with their fleet. But a Spanish fleet was waiting for them instead. Drake escaped by constructing a raft and sailing to an island three leagues offshore, where he contacted his own ships. Once safely aboard with his crew, he sent a rescue party back for La Testu. When Drake's men returned, they reported that the Frenchmen and his companions had been caught by Spanish soldiers and executed. Le Testu was beheaded. One of his men was tortured until he revealed the location of most of the buried silver. Le Testu's head was taken back to Nombre de Dios where it was displayed in the marketplace.

He was born sometime around 1509–12, and became one of the last pupils to be taught cartography at the famous school of Dieppe. Because of his mapmaking skills, Le Testu took part in voyages of exploration all through the Atlantic Ocean.

In 1550, Le Testu was commissioned by the king of France to create a map of the Americas. It was a dangerous mission, because at the time, knowledge of the landscape of the region was something of a military secret, held by Spain and Portugal. Le Testu charted areas as far as Rio de Janeiro, when he was attacked by the Portuguese and took heavy damage to his ship.

In 1555, Le Testu published a world atlas, and received an award from the King for his work. The book contained 56 maps, based on charts Le Testu had drawn by hand on his expeditions. This atlas was dedicated to his mentor and patron Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, who had become leader of the Huguenots three years earlier.

Interestingly enough, the work also contains a chart of Australia, which Le Testu called “Java Major.” The area of the map near the as-yet undiscovered continent contains drawings of what may be a black swan and a cassowary, birds native to Australia. It is notated as follows:

The present Figure contains … La Grant Jave [Java Major], and La Petite Jave [Java Minor] in which there are eight Kingdoms. The men of these two Countries are Idolaters and wicked. Several manner of spices grow in these two Regions, such as Nutmeg, Cloves, and other spices... This Land is part of the so-called Terra Australis, to us Unknown, so that which is marked herein is only from Imagination and uncertain opinion; for some say that La Grant Jave which is the eastern Coast of it is the same land of which the western Coast forms the Strait of Magellan, and that all of this land is joined together...

This Part is the same Land of the south called Austral, which has never yet been discovered, for there is no account of anyone having yet found it, and therefore nothing has been remarked of it but from Imagination. I have not been able to describe any of its resources, and for this reason I leave speaking further of it until more ample discovery has been made, and as much as I have written and annoted names to several of its capes this has only been to align the pieces depicted herein to the views of others and also so that those who navigate there be on their guard when they are of opinion that they are approaching the said Land...

Le Testu’s career was temporarily halted by the French Wars of Religion. The mid-1500’s to the mid 1600’s were a time of civil and religious upheaval. In France, this took the form of civil wars between the Huguenots (Protestant reformers) and Catholics. (Catholicism being the official religion of France.) Le Testu, who had been mentored by a member of the Huguenot cause, sided with the Huguenots. This was his entry into piracy. He conducted privateering raids for two years, but was eventually captured by the Catholics.

However, his service to France as a mapmaker came to his rescue. After four years of imprisonment, he was released by order of King Charles IX.

Francis Drake

Francis DrakeLe Testu went back to sea, perhaps aiming to improve his maps. On March 23, 1573, he bumped into Sir Francis Drake near Cativá, Panama. Drake shared news of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, an attack by the French King, a Catholic, that killed many French Huguenot nobles. (Estimates range from 5,000 to 30,000 dead.) Upon learning of this, Le Testu offered to join Drake in a raid against the (Catholic) Spanish. Drake intended to attack the mule train carrying treasure to the city of Nombre de Dios where galleons would pick it up for transport to Spain.

Drake and Le Testu sailed their combined fleet to Panama. They landed with their men just east of Nombre de Dios. Le Testu had 70 men under his command while Drake himself led only 31. As their ships sailed off, with orders to return for them in four days, the party headed inland to a spot south of the city, where they waited for the Spanish mule train.

Soon after their arrival the pirates heard bells in the distance – the bells on the Spanish pack mules. Scouts reported that the caravan consisted of almost 200 mules, each carrying up to three hundred pounds of treasure. Drake had chosen the spot for the ambush, believing the Spaniards to be at their most vulnerable as they were nearing their destination, having traveled through miles of jungle.

The attack was a complete success. Together Drake and Le Testu captured nearly 30 tons of gold and silver. There was so much treasure that the privateers were unable carry all the silver off and buried what remained. (This may be one origin of the legends of buried treasure.)

However, Le Tetsu was seriously wounded during the first assault. He was forced to rest by the roadside until he was able to travel. Two of his men stayed at his side.

The rest of the party continued onward. to meet the scheduled rendezvous with their fleet. But a Spanish fleet was waiting for them instead. Drake escaped by constructing a raft and sailing to an island three leagues offshore, where he contacted his own ships. Once safely aboard with his crew, he sent a rescue party back for La Testu. When Drake's men returned, they reported that the Frenchmen and his companions had been caught by Spanish soldiers and executed. Le Testu was beheaded. One of his men was tortured until he revealed the location of most of the buried silver. Le Testu's head was taken back to Nombre de Dios where it was displayed in the marketplace.

Published on April 03, 2017 18:41

March 27, 2017

Last Episode of Black Sails.

The Last Episode of Black Sails

As many of you may know I have spent the last four years reviewing a television show on Starz, which is called Black Sails. It’s about pirates, and DenofGeek.us wanted a pirate expert to lend some historical knowledge into the mix.

I was delighted, and I’ve followed the show for its entire four season run. I’ve watched as the characters run through their story arches; They have been raised up, cast down, and have scrambled back into power. I believe that it’s the best TV show ever made about pirates.

Pirates and TV don’t usually go well together. The classic pirate story is about the quest of r treasure… A full-throated quest for the one big score that will make everyone’s fortune for life. The theme was set by no less writer than Robert Lewis Stevenson, in his classic work, Treasure Island.

The problem is that, once the treasure has been found, there is no reason for the pirates to go on pirating. They can go ahead with their plans to move to London, buy a big house, and ride around in a carriage. Compared to the exciting life of a pirate, it seems like an enormous let-down.

Stevenson “fixed” the problem that he had created by taking the treasure away from the pirates in the end. And then he fixed the problem that was created by that disappointing fact by allowing the villainous and charismatic Long John Silver to escape – probably with a pocket full of gold and gems. I believe that the fascination with what Silver might be up to next is what cements the novel as a classic for the ages.