T.S. Rhodes's Blog, page 11

March 14, 2016

Pirates of the Golden Age

The new non-fiction book by TS Rhodes

We’re interviewing TS Rhodes, the author of the new pirate history book, Pirates of the Golden Age: Revealing the True History of Pirates and Their World. Hi, Ms. Rhodes!

Hi! It's a pleasure to be here!

Question: How did you become interested in pirates?

Answer: I saw Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean. Since I couldn’t find any other really good movies about pirates, so I started reading books, mostly non-fiction.

Q: How long have you been doing research?

A: It would be thirteen years? I’ve been reading about pirates constantly. There's been a lot of discoveries lately. I’ve also been learning about life during the time of the pirates- the early eighteenth century. Fashion, food, customs, housing. I’ve also read a lot of general history and social history.

Q: What made you decide to write this book?

A: Well, for one thing, it seemed like there was a need for something like Pirates of the Golden Age. Many of the research books I’ve read were very detailed… Four hundred pages of information on the economic and political lives of eighteenth century sailors, a day-by-day breakdown of the movements of a pirate ship through the Caribbean... It can be a lot to get through.

Q: Didn’t you enjoy reading them?

A: I did. But that’s not for everyone. I was especially interested in writing for young people, and for folks who don’t usually read history books for fun.

Q: Why young people?

A: I’ve read my share of children’s pirate books. But there is this huge gap between How I Became a Pirate and Pirate Santa and grownup books like The General History of Pyrates. There are a few pirate history books aimed at younger readers, but they tend to be out of date. A lot of research and discovery has happened in the last thirty years. It’s changed our understanding of pirates quite a bit.

[image error]

Q: Are pirates really a children’s topic?

A: Young children love pirates because pirates get to run away from home and do whatever they want. But I hope that as kids get older, they will want to know the story of real pirates. By the time a young person is old enough to want to know what really happened in the past, they deserve to know the truth. I wrote this book especially to be an introduction to the Golden Age, the time between 1690 and 1720, which is what we think about when we think of pirates.

Q: What’s in the book?

A: Pirates of the Golden Age centers on the lives of nine pirate captains, two female pirates, and a child who was a pirate during the Golden Age. But it also contains information on why pirates became pirates – the situation that drove these people to take up a life of crime. It talks about the jobs they held before becoming pirates, how they learned the trade, the clothing these people wore, how they spent their time. I wanted to tell the whole story.

Q: Is it illustrated?

A: Yes. Woodcuts from the actual time of the pirates are included.

Q: Could adults read this?

A: I think many adults would enjoy it as well. So often history books assume that the reader already knows certain things. Maybe you don’t know what women’s rights were like in 1715. But this book fills in all the details that a person needs to know to really understand pirates. It was meant to be a fun read for anyone.

Q: Is it available on Amazon?

A: Yes, it is. Only $9.95! I hope that you'll buy a copy and enjoy it. And if you do, be sure to leave a review. Reviews are the best compliment you can give an author.

We’re interviewing TS Rhodes, the author of the new pirate history book, Pirates of the Golden Age: Revealing the True History of Pirates and Their World. Hi, Ms. Rhodes!

Hi! It's a pleasure to be here!

Question: How did you become interested in pirates?

Answer: I saw Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean. Since I couldn’t find any other really good movies about pirates, so I started reading books, mostly non-fiction.

Q: How long have you been doing research?

A: It would be thirteen years? I’ve been reading about pirates constantly. There's been a lot of discoveries lately. I’ve also been learning about life during the time of the pirates- the early eighteenth century. Fashion, food, customs, housing. I’ve also read a lot of general history and social history.

Q: What made you decide to write this book?

A: Well, for one thing, it seemed like there was a need for something like Pirates of the Golden Age. Many of the research books I’ve read were very detailed… Four hundred pages of information on the economic and political lives of eighteenth century sailors, a day-by-day breakdown of the movements of a pirate ship through the Caribbean... It can be a lot to get through.

Q: Didn’t you enjoy reading them?

A: I did. But that’s not for everyone. I was especially interested in writing for young people, and for folks who don’t usually read history books for fun.

Q: Why young people?

A: I’ve read my share of children’s pirate books. But there is this huge gap between How I Became a Pirate and Pirate Santa and grownup books like The General History of Pyrates. There are a few pirate history books aimed at younger readers, but they tend to be out of date. A lot of research and discovery has happened in the last thirty years. It’s changed our understanding of pirates quite a bit.

[image error]

Q: Are pirates really a children’s topic?

A: Young children love pirates because pirates get to run away from home and do whatever they want. But I hope that as kids get older, they will want to know the story of real pirates. By the time a young person is old enough to want to know what really happened in the past, they deserve to know the truth. I wrote this book especially to be an introduction to the Golden Age, the time between 1690 and 1720, which is what we think about when we think of pirates.

Q: What’s in the book?

A: Pirates of the Golden Age centers on the lives of nine pirate captains, two female pirates, and a child who was a pirate during the Golden Age. But it also contains information on why pirates became pirates – the situation that drove these people to take up a life of crime. It talks about the jobs they held before becoming pirates, how they learned the trade, the clothing these people wore, how they spent their time. I wanted to tell the whole story.

Q: Is it illustrated?

A: Yes. Woodcuts from the actual time of the pirates are included.

Q: Could adults read this?

A: I think many adults would enjoy it as well. So often history books assume that the reader already knows certain things. Maybe you don’t know what women’s rights were like in 1715. But this book fills in all the details that a person needs to know to really understand pirates. It was meant to be a fun read for anyone.

Q: Is it available on Amazon?

A: Yes, it is. Only $9.95! I hope that you'll buy a copy and enjoy it. And if you do, be sure to leave a review. Reviews are the best compliment you can give an author.

Published on March 14, 2016 20:22

March 7, 2016

Madagascar and the Pirate Republic of Libertatia.

Madagascar is the fourth largest island in the world. It lies off the coast of Mozambique, on the eastern coast of Africa. Geologically, it is a separation of India’s tectonic plate. The animals of the island have been developing in isolation for 88 million years. 80% of Madagascar’s plants and animals are found nowhere else.

The island’s climate is tropical, but a high, flat plateau in the center provide lower temperatures that have encouraged human habitation and have been planted in terraced rice fields.

Humans came to the island about 3000 years ago, but apparently only on foraging expeditions. Permanent human habitation started between 350 BC and 550 AD, probably by people who arrived on outrigger canoes from Borneo. Bantu people from Mozambique arrived shortly thereafter. The current name for the ethic group of the islands is Malagasy, which is also what the islanders call their home.

The name Madagascar was coined by the famous explorer Marco Polo who wrote about the island. Though other explorers tried to name the island after saints, the name Madagascar stuck, possibly for no other reason than its pleasing sense of the exotic.

The poster child for Madagascar’s native wildlife is the ring tailed lemur. There are over 100 different species of lemurs on the island, and lemur are found nowhere else. The island hosts over 260 species of lizard, probably all descendants from just a few individuals who reached the island. A catlike animal called a fossa is the largest predator on the island, but at only 31 inches long and maximum weight of 19 pounds, they are not generally dangerous to humans.

Until about 1700, the inhabitants of Madagascar ruled the island through a shifting group of tribal coalitions. But at about this time, the pirates arrived.

Europeans had finally reached a sufficient level of technology that they could sail around Africa with general success. When they did so, the stumbled across a thriving commercial culture. India, Arabia, and Southeast Asia all traded through the region, and Europeans wanted what these people had.

The East India Company, a corporation, had been founded by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600. They had struggled against distance, weather and competition from the Dutch. But even the smallest success had the possibility of enormous financial gains.

Madagascar and the surrounding smaller islands were the prefect base for pirate raids on these trading ships. Pirates robbed East India ships, Arab traders, and pilgrims going to and from the holy city of Mecca through the mouth of the Red Sea.

At one time the island of St Mary had a permanent colony of 1,500 pirates and traders. Dishonest merchants could pick up silk, cotton and spices form the pirates and transport these products to ports like New York and Boston, where they could be sold at a huge profit to people who didn’t ask too many questions.

The pirate nation of Libertatia may or may not have been a fiction. But it held a fir place in the hearts and imaginations of pirates world-wide. Supposedly the nation had been founded by a pirate named Captain Mission. According to the pirates, it was a direct democracy. The pirates elected officials to run the colony, but encouraged these people not to think of themselves as rulers, but as public servants, not in any way above the rest of the citizens.

The historian Marcus Riker described the pirates this way: “These pirates who settled in Libertalia would be "vigilant Guardians of the People's Rights and Liberties"; they would stand as "Barriers against the Rich and Powerful" of their day. By waging war on behalf of "the Oppressed" against the "Oppressors," they would see that "Justice was equally distributed."

The colony was supposed to be half-white and half-black, the races intermingled freely. Mission was supposed to have been a French sailor, born in Provance and converted to a belief in atheist, socialist anarchy by “a lewd priest” that he sailed with. When the sailors of Mission’s ship mutinied, they elected him captain, and he then created the pirate nation.

The pirates in this colony became farmers and married native women. They also freed many African, Indian and Arabian slaves, who they encouraged to join their society. Individuals who chose to make money by robbing ships simply turned their plunder over to the common treasury. Even farmer’s fields were held in common.

Was it true? The pirates certainly believed it was true. When pirates began to over-run Nassau in the Bahamas, they claimed that they “would make another Madagascar of the island.”

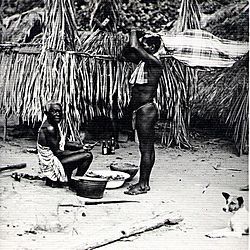

One thing which definitely attracted pirates to the area was the fact that the locals practiced polygamy. A pirate flush with gold and armed with firearms could hammer out a veritable kingdom on the island.

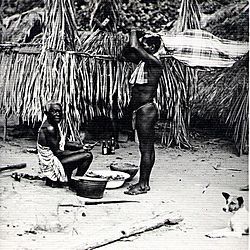

Visitors describe family compounds surrounded by walls and set apart in jungle terrain. Pirate families were huge, including many women and dozens of children. These visitors were horrified to see that any remnants of European clothing had fallen to rags, and the pirate lords dressed in native style (which was probably a lot more comfortable than the European style.)

Thomas Tew

Thomas Tew

We have some evidence that known pirates such as Thomas Cocklyn, Thomas Tew and Olivier Levasseur lived in or around Madagascar. Levasseur returned there for a number of years. But the island life, while pleasant and peaceful, was somewhat boring. Levasseur first ask for a pardon for his crimes, but upon learning that he would have to give back some of his stolen money, he returned to his lair. He was killed shortly thereafter, caught on a pirating mission that he had probably started simply to have something exciting to do.

[image error]

The pirates did not so much leave Madagascar as they and their descendants were simply absorbed into the local population. They did leave behind a spirit of freedom. Madagascar become a kingdom in order to stand off the increasingly invasive colonial powers. It spent a short time as a French colony, and it became an independent nation in 1960. Today it is a semi-presidential representative democratic multi-party republic (whew!) with a small industry in pirate tourism, among other things.

The island’s climate is tropical, but a high, flat plateau in the center provide lower temperatures that have encouraged human habitation and have been planted in terraced rice fields.

Humans came to the island about 3000 years ago, but apparently only on foraging expeditions. Permanent human habitation started between 350 BC and 550 AD, probably by people who arrived on outrigger canoes from Borneo. Bantu people from Mozambique arrived shortly thereafter. The current name for the ethic group of the islands is Malagasy, which is also what the islanders call their home.

The name Madagascar was coined by the famous explorer Marco Polo who wrote about the island. Though other explorers tried to name the island after saints, the name Madagascar stuck, possibly for no other reason than its pleasing sense of the exotic.

The poster child for Madagascar’s native wildlife is the ring tailed lemur. There are over 100 different species of lemurs on the island, and lemur are found nowhere else. The island hosts over 260 species of lizard, probably all descendants from just a few individuals who reached the island. A catlike animal called a fossa is the largest predator on the island, but at only 31 inches long and maximum weight of 19 pounds, they are not generally dangerous to humans.

Until about 1700, the inhabitants of Madagascar ruled the island through a shifting group of tribal coalitions. But at about this time, the pirates arrived.

Europeans had finally reached a sufficient level of technology that they could sail around Africa with general success. When they did so, the stumbled across a thriving commercial culture. India, Arabia, and Southeast Asia all traded through the region, and Europeans wanted what these people had.

The East India Company, a corporation, had been founded by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600. They had struggled against distance, weather and competition from the Dutch. But even the smallest success had the possibility of enormous financial gains.

Madagascar and the surrounding smaller islands were the prefect base for pirate raids on these trading ships. Pirates robbed East India ships, Arab traders, and pilgrims going to and from the holy city of Mecca through the mouth of the Red Sea.

At one time the island of St Mary had a permanent colony of 1,500 pirates and traders. Dishonest merchants could pick up silk, cotton and spices form the pirates and transport these products to ports like New York and Boston, where they could be sold at a huge profit to people who didn’t ask too many questions.

The pirate nation of Libertatia may or may not have been a fiction. But it held a fir place in the hearts and imaginations of pirates world-wide. Supposedly the nation had been founded by a pirate named Captain Mission. According to the pirates, it was a direct democracy. The pirates elected officials to run the colony, but encouraged these people not to think of themselves as rulers, but as public servants, not in any way above the rest of the citizens.

The historian Marcus Riker described the pirates this way: “These pirates who settled in Libertalia would be "vigilant Guardians of the People's Rights and Liberties"; they would stand as "Barriers against the Rich and Powerful" of their day. By waging war on behalf of "the Oppressed" against the "Oppressors," they would see that "Justice was equally distributed."

The colony was supposed to be half-white and half-black, the races intermingled freely. Mission was supposed to have been a French sailor, born in Provance and converted to a belief in atheist, socialist anarchy by “a lewd priest” that he sailed with. When the sailors of Mission’s ship mutinied, they elected him captain, and he then created the pirate nation.

The pirates in this colony became farmers and married native women. They also freed many African, Indian and Arabian slaves, who they encouraged to join their society. Individuals who chose to make money by robbing ships simply turned their plunder over to the common treasury. Even farmer’s fields were held in common.

Was it true? The pirates certainly believed it was true. When pirates began to over-run Nassau in the Bahamas, they claimed that they “would make another Madagascar of the island.”

One thing which definitely attracted pirates to the area was the fact that the locals practiced polygamy. A pirate flush with gold and armed with firearms could hammer out a veritable kingdom on the island.

Visitors describe family compounds surrounded by walls and set apart in jungle terrain. Pirate families were huge, including many women and dozens of children. These visitors were horrified to see that any remnants of European clothing had fallen to rags, and the pirate lords dressed in native style (which was probably a lot more comfortable than the European style.)

Thomas Tew

Thomas TewWe have some evidence that known pirates such as Thomas Cocklyn, Thomas Tew and Olivier Levasseur lived in or around Madagascar. Levasseur returned there for a number of years. But the island life, while pleasant and peaceful, was somewhat boring. Levasseur first ask for a pardon for his crimes, but upon learning that he would have to give back some of his stolen money, he returned to his lair. He was killed shortly thereafter, caught on a pirating mission that he had probably started simply to have something exciting to do.

[image error]

The pirates did not so much leave Madagascar as they and their descendants were simply absorbed into the local population. They did leave behind a spirit of freedom. Madagascar become a kingdom in order to stand off the increasingly invasive colonial powers. It spent a short time as a French colony, and it became an independent nation in 1960. Today it is a semi-presidential representative democratic multi-party republic (whew!) with a small industry in pirate tourism, among other things.

Published on March 07, 2016 18:18

February 29, 2016

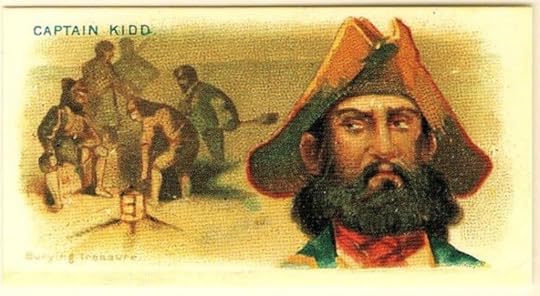

The Final Fate of Captain Kidd

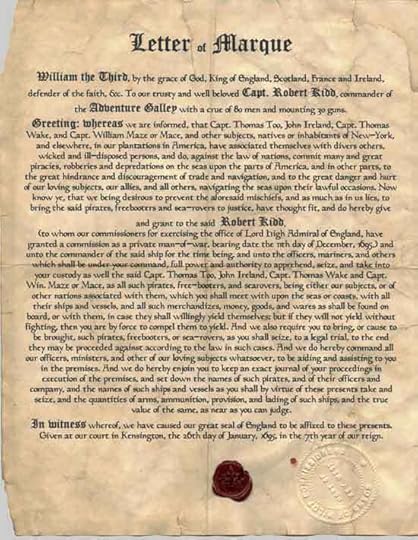

After spending two years chasing pirates in the Indian ocean, William Kidd arrived back home. He had made one significant capture, not of a pirate, but of a ship carrying a French shipping license. Since France and England were at war, Kidd assumed the French ship was a lawful prize.

But when Kidd returned to English territory - he made landfall in the Caribbean - he discovered that he was accused of piracy. He left his ship and much of his plunder, and returned to New York using a smaller vessel. The men that he had left buried the treasure and burned the ship as per Kidd's instructions.

Once in New York, Kidd visited his wife and step-children, and hired a lawyer. He also may have buried additional treasure in the area.

But Kidd’s royal backers were in a frenzy. The plan had been to send Kidd into the Indian Ocean, capture several pirate ships, bring their treasure home on a schedule, and declare victory. Instead, Kidd had taken years more than expected. The Indian Ocean situation was worse than ever, merchant ship owners were angry, the Royal Navy felt insulted, and people were accusing Kidd of turning pirate himself.

Worse, he may have been trying to cheat his financial backers.

Kidd did not do much to help his own situation. He turned the French licenses from the ship he had robbed over to his lawyer. The lawyer promptly gave them to Kidd's secret backer, Lord Bellomont, who made them disappear. Then Kidd tried clumsily to bribe various people. He also began to hint that he had vast riches buried.

Richard Coot, First Earl of Bellomont

Richard Coot, First Earl of Bellomont

Probably he thought that no one would hang him as long as he had money that only he could recover.At this time, all pirate trials were held in England. Kidd and the men who returned with him were taken back to England at once. They were held awaiting trial for over a year.

When the trial finally took place, it was a confusion of contradicting testimony. Kidd told a story that wasn’t very consistent. During one part of his testimony, he claimed that the Adventure Galley had sunk. Later he said that he had burned her.

But the real testimony against Kidd was the opinion of the English people. Kidd's mission had been, as much as anything, a public relations ploy. Powerful men in English politics wanted to be seen to be "doing something" about the pirate problem. But they were smart enough to keep their identities secret.

If the mission had gone as planned - a short voyage, the capture of several pirate ship, Kidd returning with piles of formerly-pirate treasure - these men probably would have stepped forward to take credit for the effort. Since it had become a disaster, they wanted their names kept as far away form the bad publicity as possible.

The end result had already been decided. Kidd was found guilty. But, perhaps because he still believed his powerful backers would save him, he never revealed the names of his financiers.

He did, however, offer to take officials to a “secret place” where he had stashed much treasure. Perhaps he believed that the lust for gold would protect him. Instead, he was sentenced to hang.

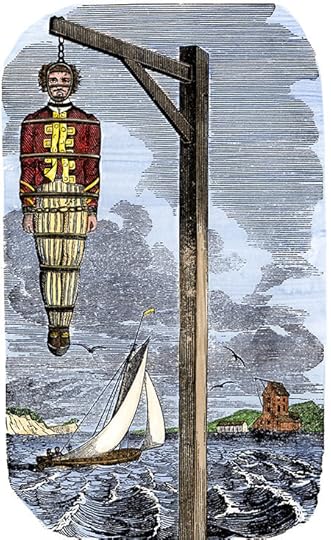

His backers, still terrified that he would implicate them, made sure that on the day of his execution, Kidd was too drunk to speak, or even to stand. He was hauled bodily to the scaffold. But when he was dropped, the rope broke. Another rope was quickly put up, and William Kid was hanged by the neck until dead on the 23rd of May 1701. According to custom, his body was then covered in tar and left on display, as a warning to other pirates.

Kidd may have never actually been a pirate, but he became the scapegoat of a failed mission. What he did do was to bury treasure. Conservative estimates say that if it were found today, Kidd’s stash would be worth many millions of dollars.

But where was the gold? Treasure hunters have looked in and around New York, the Carolinas, Catalina Island and Antigua in the Caribbean, and on various islands in the Indians Ocean. Recent explorers claim to have found the remains of the Adventure Galley but nothing is yet verified. Certainly no millions of dollars of plunder have yet been uncovered.

Kidd may not even have been a pirate. But he single-handedly started the stories of buried treasure, and as a pirate legend, he is immortal.

But when Kidd returned to English territory - he made landfall in the Caribbean - he discovered that he was accused of piracy. He left his ship and much of his plunder, and returned to New York using a smaller vessel. The men that he had left buried the treasure and burned the ship as per Kidd's instructions.

Once in New York, Kidd visited his wife and step-children, and hired a lawyer. He also may have buried additional treasure in the area.

But Kidd’s royal backers were in a frenzy. The plan had been to send Kidd into the Indian Ocean, capture several pirate ships, bring their treasure home on a schedule, and declare victory. Instead, Kidd had taken years more than expected. The Indian Ocean situation was worse than ever, merchant ship owners were angry, the Royal Navy felt insulted, and people were accusing Kidd of turning pirate himself.

Worse, he may have been trying to cheat his financial backers.

Kidd did not do much to help his own situation. He turned the French licenses from the ship he had robbed over to his lawyer. The lawyer promptly gave them to Kidd's secret backer, Lord Bellomont, who made them disappear. Then Kidd tried clumsily to bribe various people. He also began to hint that he had vast riches buried.

Richard Coot, First Earl of Bellomont

Richard Coot, First Earl of BellomontProbably he thought that no one would hang him as long as he had money that only he could recover.At this time, all pirate trials were held in England. Kidd and the men who returned with him were taken back to England at once. They were held awaiting trial for over a year.

When the trial finally took place, it was a confusion of contradicting testimony. Kidd told a story that wasn’t very consistent. During one part of his testimony, he claimed that the Adventure Galley had sunk. Later he said that he had burned her.

But the real testimony against Kidd was the opinion of the English people. Kidd's mission had been, as much as anything, a public relations ploy. Powerful men in English politics wanted to be seen to be "doing something" about the pirate problem. But they were smart enough to keep their identities secret.

If the mission had gone as planned - a short voyage, the capture of several pirate ship, Kidd returning with piles of formerly-pirate treasure - these men probably would have stepped forward to take credit for the effort. Since it had become a disaster, they wanted their names kept as far away form the bad publicity as possible.

The end result had already been decided. Kidd was found guilty. But, perhaps because he still believed his powerful backers would save him, he never revealed the names of his financiers.

He did, however, offer to take officials to a “secret place” where he had stashed much treasure. Perhaps he believed that the lust for gold would protect him. Instead, he was sentenced to hang.

His backers, still terrified that he would implicate them, made sure that on the day of his execution, Kidd was too drunk to speak, or even to stand. He was hauled bodily to the scaffold. But when he was dropped, the rope broke. Another rope was quickly put up, and William Kid was hanged by the neck until dead on the 23rd of May 1701. According to custom, his body was then covered in tar and left on display, as a warning to other pirates.

Kidd may have never actually been a pirate, but he became the scapegoat of a failed mission. What he did do was to bury treasure. Conservative estimates say that if it were found today, Kidd’s stash would be worth many millions of dollars.

But where was the gold? Treasure hunters have looked in and around New York, the Carolinas, Catalina Island and Antigua in the Caribbean, and on various islands in the Indians Ocean. Recent explorers claim to have found the remains of the Adventure Galley but nothing is yet verified. Certainly no millions of dollars of plunder have yet been uncovered.

Kidd may not even have been a pirate. But he single-handedly started the stories of buried treasure, and as a pirate legend, he is immortal.

Published on February 29, 2016 16:40

February 22, 2016

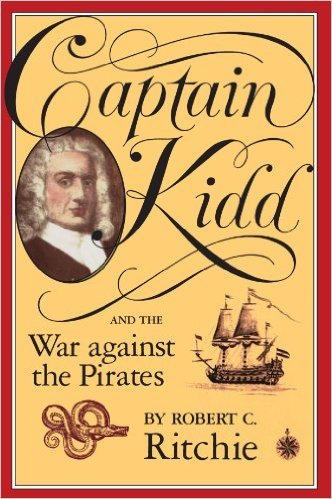

The Notorious Captain Kidd - Part 2

A former privateer, Captain William Kidd had been given a commission from King William of England to hunt pirates in the Indian Ocean

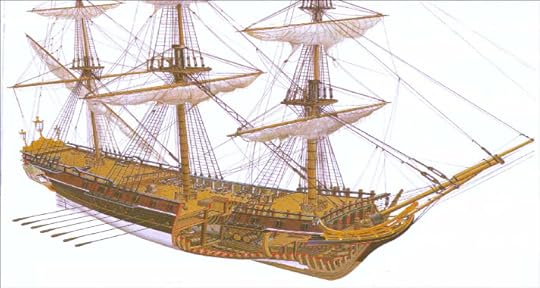

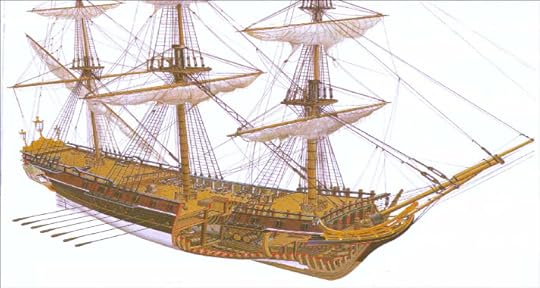

Kidd’s new ship was named the Adventure Galley, a 34-gun vessel with oars and sails, a perfect tool for such a mission. It was built in the King’s own shipyard, and completed in January of 1695.Kidd carefully selected a crew of 70 men whom he believed would not turn to piracy. Most of them had wives and families in England.

Kidd appears to have been drinking heavily during the launch party, and it caused problems almost at once. While still traveling down the Thames River toward the sea, the Adventure Galley passed a Royal Navy ship. The Adventure Galley was required by custom to salute the navy ship, but for some reason it did not. The navy captain complained, and Kidd’s men replied by dropping their breeches, sticking their backsides over the rail and smacking their bare buttocks.

The navy captain replied by pulling over the Adventure Galley and impressing many men from the crew, forcing them to join the Royal Navy on the spot. Kidd was immediately forced to find new crew members. He then sailed for New York, arriving in July 1696. He set sail again in September,

[image error]

His required return date, of March 1697 was already impossible to meet.

We next see Kidd and the Adventure Galley 100 miles from Africa’s Cape Town. Kidd stopped a ship of the Royal Navy and demanded that the captain supply him with new sails to replace those that had been damaged in his trip across the Atlantic. When he was refused, he threatened to stop the first English merchant vessel he saw and take the sails from it. The navy captain replied that he would charge Kidd with treason and impress more of his men.

Kidd’s answer was to use his ship’s oars to row away quietly during the night, before any further steps could be taken.

Because of this incident, Kidd did not stop in at Cape Town as planned, Instead he went straight around Africa. Once on the east coast, near Madagascar, he landed to refill supplies. Contact with African germs, coupled with a crew that had been at sea for months, took out fifty sailors through sickness. Once again, Kidd needed to get new crew members. Then he headed for the mouth of the Red Sea, the same spot where Henry Avery had waited with his pirate cohorts to ambush the returning treasure fleet, two years before.

But unlike Avery who seemed to have been graced by good luck, Kidd faced mounting problems. In addition to having lost almost all of his carefully picked original crew, Kidd’s brand new pirate-chasing ship was in bad shape. She had been under sail for only a year, but already her joints were getting loose, causing her to leak badly. The warm tropical waters had done her no good either. Her bottom was being eaten by salt-water parasites called shipworms.

And in only one month, Kid was due back in London with the goods from captured ships.

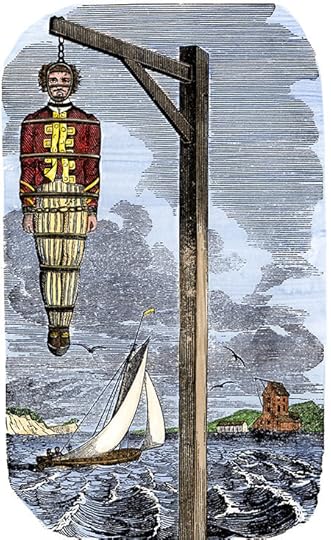

Weeks passed and they had still had taken no prizes of note, only a few fishing vessels. One man, a gunner named William Moore, got into a ferocious argument with Kidd. Like their captain, the common sailors would receive pay only if they captured ships, and the expedition had so far been unable to find any pirates. Moore began to talk mutiny. In response, Kidd threw a bucket at him and hit him in the head. Moore feel to deck, and died the next day.

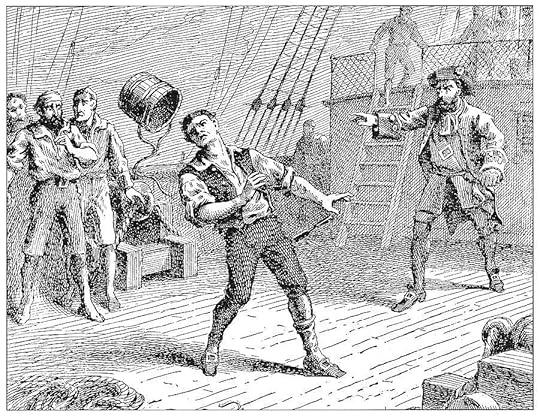

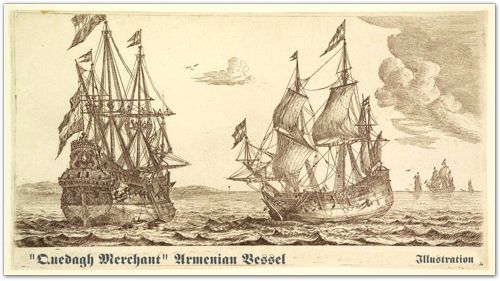

Finally, in February of 1698, almost a year after they were due back in England, Kidd and company attacked and seized a merchant ship called the Quedagh Merchant. The ship was owned by Armenians, crewed by Moors, carrying Persian cargo, and captained by an Englishman named Wright. She was also definitely not a pirate.

But she was carrying a French pass, and part of the voyage’s mission was to attack the French. It was good enough for Kidd.

What happened next is still under dispute. Kidd claimed that he was attacked by a pirate named Culliford, who took all the guns, shot and powder from the Adventure Galley, then sailed off. The ship was by this time ready to fall apart, so Kidd transferred everything left by the pirates into the Quedgah Merchant, and burned his former flagship.

More cynical sorts point out that Culliford was the man who had stolen the Blessed William from him in 1689. This story goes that Kidd, whose men were fired up by their recent success, wanted to become full-blown pirates.

According to this version, Kidd gave the Adventure Galley to Culliford, to replace his own ship, which had been badly damaged in a fight. The two men then hung out in local taverns while Culliford’s pirates worked to make the Adventure seaworthy again. Most of Kidd’s sailors did become pirates, but Kidd kept the bulk of the plunder and buried it – and his logbook – in a secret place on the island.

Why would Kidd do this? Why, out of all the pirates in the world, would he alone bury his treasure?

Unlike other pirates, Kidd had investors to pay off. If he arrived back in England with the spoils of his single capture, the bulk of the money would go to the king, the investors, and Blackham. Kidd’s share would have been less than 5% of the treasure he had been working for over two years trying to obtain.

But, if he came home with much less money, say, only £10,000 worth of treasure, he could pay off his investors and later go back for the buried gold. This plan, however, required hiding his logbook as well as the money, because it revealed the amount of plunder had been on the Quedgah Merchant.Kidd’s story was that Culliford took his logbook.

Kidd's biggest problem was that the Navy captains he had been confronting sent dispatches home regularly, and they had friends in London. Kidd had never treated the Royal Navy with the respect the captains thought they were due. And his loose words and disorderly conduct had inspired them to accuse him of piracy.

By the time Kidd made it back to England, his enemies' stories had been before the public for a long time. Ship owners harassed by Kidd while he looked for pirates, continued reports of blatant pirate activity (in spite of Kidd’s mission to find and attack them), and the reports of enraged navy captains had all painted him as a confirmed pirate long before he reached port.

Kidd made landfall first in the Caribbean. There he learned the story of his supposed “pirate” attacks. But he convinced his crew to return with him to New York, where he was sure he could prove his innocence. But, as a precaution, he sailed north on a small ship he purchased called the Antonio. The Quedgah Merchant with some of the crew, stayed behind on the island of Hispaniola. The crew stripped her of goods, buried the treasure, and then burned her.

Next week... The fate of Captain Kidd

Kidd’s new ship was named the Adventure Galley, a 34-gun vessel with oars and sails, a perfect tool for such a mission. It was built in the King’s own shipyard, and completed in January of 1695.Kidd carefully selected a crew of 70 men whom he believed would not turn to piracy. Most of them had wives and families in England.

Kidd appears to have been drinking heavily during the launch party, and it caused problems almost at once. While still traveling down the Thames River toward the sea, the Adventure Galley passed a Royal Navy ship. The Adventure Galley was required by custom to salute the navy ship, but for some reason it did not. The navy captain complained, and Kidd’s men replied by dropping their breeches, sticking their backsides over the rail and smacking their bare buttocks.

The navy captain replied by pulling over the Adventure Galley and impressing many men from the crew, forcing them to join the Royal Navy on the spot. Kidd was immediately forced to find new crew members. He then sailed for New York, arriving in July 1696. He set sail again in September,

[image error]

His required return date, of March 1697 was already impossible to meet.

We next see Kidd and the Adventure Galley 100 miles from Africa’s Cape Town. Kidd stopped a ship of the Royal Navy and demanded that the captain supply him with new sails to replace those that had been damaged in his trip across the Atlantic. When he was refused, he threatened to stop the first English merchant vessel he saw and take the sails from it. The navy captain replied that he would charge Kidd with treason and impress more of his men.

Kidd’s answer was to use his ship’s oars to row away quietly during the night, before any further steps could be taken.

Because of this incident, Kidd did not stop in at Cape Town as planned, Instead he went straight around Africa. Once on the east coast, near Madagascar, he landed to refill supplies. Contact with African germs, coupled with a crew that had been at sea for months, took out fifty sailors through sickness. Once again, Kidd needed to get new crew members. Then he headed for the mouth of the Red Sea, the same spot where Henry Avery had waited with his pirate cohorts to ambush the returning treasure fleet, two years before.

But unlike Avery who seemed to have been graced by good luck, Kidd faced mounting problems. In addition to having lost almost all of his carefully picked original crew, Kidd’s brand new pirate-chasing ship was in bad shape. She had been under sail for only a year, but already her joints were getting loose, causing her to leak badly. The warm tropical waters had done her no good either. Her bottom was being eaten by salt-water parasites called shipworms.

And in only one month, Kid was due back in London with the goods from captured ships.

Weeks passed and they had still had taken no prizes of note, only a few fishing vessels. One man, a gunner named William Moore, got into a ferocious argument with Kidd. Like their captain, the common sailors would receive pay only if they captured ships, and the expedition had so far been unable to find any pirates. Moore began to talk mutiny. In response, Kidd threw a bucket at him and hit him in the head. Moore feel to deck, and died the next day.

Finally, in February of 1698, almost a year after they were due back in England, Kidd and company attacked and seized a merchant ship called the Quedagh Merchant. The ship was owned by Armenians, crewed by Moors, carrying Persian cargo, and captained by an Englishman named Wright. She was also definitely not a pirate.

But she was carrying a French pass, and part of the voyage’s mission was to attack the French. It was good enough for Kidd.

What happened next is still under dispute. Kidd claimed that he was attacked by a pirate named Culliford, who took all the guns, shot and powder from the Adventure Galley, then sailed off. The ship was by this time ready to fall apart, so Kidd transferred everything left by the pirates into the Quedgah Merchant, and burned his former flagship.

More cynical sorts point out that Culliford was the man who had stolen the Blessed William from him in 1689. This story goes that Kidd, whose men were fired up by their recent success, wanted to become full-blown pirates.

According to this version, Kidd gave the Adventure Galley to Culliford, to replace his own ship, which had been badly damaged in a fight. The two men then hung out in local taverns while Culliford’s pirates worked to make the Adventure seaworthy again. Most of Kidd’s sailors did become pirates, but Kidd kept the bulk of the plunder and buried it – and his logbook – in a secret place on the island.

Why would Kidd do this? Why, out of all the pirates in the world, would he alone bury his treasure?

Unlike other pirates, Kidd had investors to pay off. If he arrived back in England with the spoils of his single capture, the bulk of the money would go to the king, the investors, and Blackham. Kidd’s share would have been less than 5% of the treasure he had been working for over two years trying to obtain.

But, if he came home with much less money, say, only £10,000 worth of treasure, he could pay off his investors and later go back for the buried gold. This plan, however, required hiding his logbook as well as the money, because it revealed the amount of plunder had been on the Quedgah Merchant.Kidd’s story was that Culliford took his logbook.

Kidd's biggest problem was that the Navy captains he had been confronting sent dispatches home regularly, and they had friends in London. Kidd had never treated the Royal Navy with the respect the captains thought they were due. And his loose words and disorderly conduct had inspired them to accuse him of piracy.

By the time Kidd made it back to England, his enemies' stories had been before the public for a long time. Ship owners harassed by Kidd while he looked for pirates, continued reports of blatant pirate activity (in spite of Kidd’s mission to find and attack them), and the reports of enraged navy captains had all painted him as a confirmed pirate long before he reached port.

Kidd made landfall first in the Caribbean. There he learned the story of his supposed “pirate” attacks. But he convinced his crew to return with him to New York, where he was sure he could prove his innocence. But, as a precaution, he sailed north on a small ship he purchased called the Antonio. The Quedgah Merchant with some of the crew, stayed behind on the island of Hispaniola. The crew stripped her of goods, buried the treasure, and then burned her.

Next week... The fate of Captain Kidd

Published on February 22, 2016 15:04

February 15, 2016

The Notorious Captain Kidd

Captain Kidd is one of the most notorious pirates of all time. Yet all his “pirating” was done during a single voyage to the Indian Ocean that lasted from 1695 to 1699, and there may not have been any pirating at all. Many people believe that Kidd was a lawfully licensed privateer, who never captured a ship that he was not authorized to attack.

William Kidd

William Kidd

Kidd, however, is the only pirate to have buried treasure.

William Kid was born in the town of Dundee, on the Scottish border, in 1645. His father was a ship’s captain, who was lost at sea, and the family live on charity during Kidd’s early years. Popular belief is that the young man went to sea when he was 15, but no historic details confirm this.

The first solid evidence about Kidd comes in 1689, when he is mentioned as a member of a privateering crew during the Nine Years War. Kidd’s ship captured a French vessel and sailed it into harbor on the island of Nevis, then an English colony.

The governor of the island responded by re-naming the captured ship the Blessed William and giving command of the vessel to Kidd. Whether this was because of Kidd’s family connections, his level of education, or simply because he was a persuasive man, we do not know.

Whatever the reason, it was Kidd’s first command. He defended the island, then joined an English squadron raiding a French sugar plantation. As was usual with privateering vessels, the cash and goods captured in the raid were divided to pay Kidd and his crew. The proceeds made Kidd a wealthy man, and lined the pockets of his crew comfortably.

The privateers were next required to join the squadron in standing up to equally well-armed French ships. This was a far different assignment than attacking a helpless plantation. Kidd’s crew were not happy, told their captain so. Kidd’s response was that they should do as instructed, for King and country. The crew responded by mutinying, stealing the Blessed William, and carrying off the valuable cargo. Kidd was assigned another ship, the Antigua, but then he disappears from history for a year.

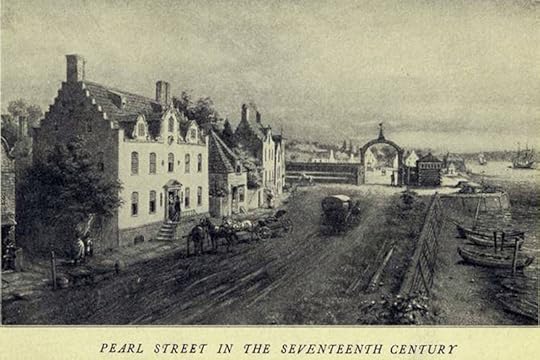

He next surfaces in New York City, then the second largest town in North America with a population of just under 5,000. There Kidd met and married Sarah Bradley Cox Oort, a woman twice widowed and very wealthy. The two lived very comfortably together for five years, and Kidd became a member of the highest level of society in the city.

New York City

New York City

Five years later, in 1695 Kidd became involved in a privateering mission to attack pirates in the Indian Ocean. We have no idea what motivated him. Perhaps he was tired of his wife’s company. Perhaps she was tired of his. Or perhaps Kidd was himself approached. We simply don’t know for sure.

The plan was sketchy from the beginning. England was still at war with France, and her international relationship with India had not been good since Henry Avery had attacked a ship carrying a member of the Indian royal family. In addition, pirates inspired by Avery were harassing the East India Company, while at the same time flooding English markets with gold and jewels which may or may not have been Arabian.

The Adventure Galley

The Adventure Galley

So, some of the highest placed men in England planned to build a mighty pirate-hunting ship, captain it with a man of know capabilities, and set it loose in the Indian Ocean, to capture pirate ships and hang wrong-doers. The plan was also to re-acquire plunder taken by the pirates, at a tremendous profit to captain and crew, but more especially to the scheme’s backers, who would fund 80% (£6,000) of the venture while remaining safely in England.

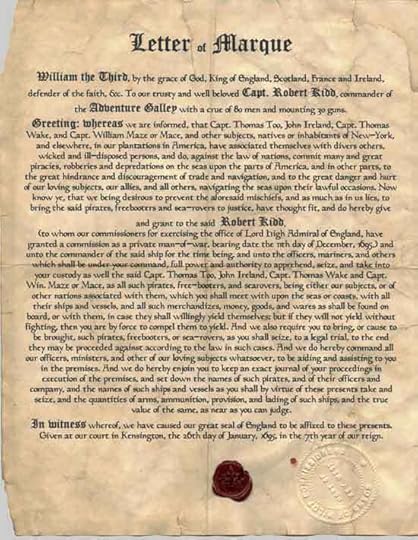

Kidd sailed to England to sign papers and receive his privateering commission. The deal, drawn up by some of the most powerful men in England, was not a standard one. In a normal privateering venture, risk was assumed by everyone. Under Kidd’s agreement, if the venture failed to produce a profit, he himself was liable to repay his bakers. It was also required that the names of the backers remain secret.

He also needed to come up with the other 20% (£1,500) not something that privateer captains were usually required to do. The profits from the venture were to be divided so that the first 10% went to the King, exchange for Kidd’s Royal Commission, and of the remainder, 60% was to go to the anonymous backers, 15% to Kidd and Livingston (the man who had brokered the deal.) The last 25% to be divided among all he members of the crew.

Kidd’s problem was that he didn’t have £1,500.

Livingston, however, also did not want to be caught out if the expedition failed. He introduced a wool merchant named Blackham, who was willing to provide a loan of the upfront money in exchange for 1/3 of Kidd and Livingston's shares. Once again, Kidd signed highly dubious documents, in complete secrecy.

Kidd’s commission, issued by King William himself, instructed Kidd to attack pirates, to attack the French, and to refrain from harming the King’s subjects or allies. Kidd was to leave on his mission as soon as possible, and return by the end of January, 1696.

Next week... Kidd's fateful voyage

William Kidd

William KiddKidd, however, is the only pirate to have buried treasure.

William Kid was born in the town of Dundee, on the Scottish border, in 1645. His father was a ship’s captain, who was lost at sea, and the family live on charity during Kidd’s early years. Popular belief is that the young man went to sea when he was 15, but no historic details confirm this.

The first solid evidence about Kidd comes in 1689, when he is mentioned as a member of a privateering crew during the Nine Years War. Kidd’s ship captured a French vessel and sailed it into harbor on the island of Nevis, then an English colony.

The governor of the island responded by re-naming the captured ship the Blessed William and giving command of the vessel to Kidd. Whether this was because of Kidd’s family connections, his level of education, or simply because he was a persuasive man, we do not know.

Whatever the reason, it was Kidd’s first command. He defended the island, then joined an English squadron raiding a French sugar plantation. As was usual with privateering vessels, the cash and goods captured in the raid were divided to pay Kidd and his crew. The proceeds made Kidd a wealthy man, and lined the pockets of his crew comfortably.

The privateers were next required to join the squadron in standing up to equally well-armed French ships. This was a far different assignment than attacking a helpless plantation. Kidd’s crew were not happy, told their captain so. Kidd’s response was that they should do as instructed, for King and country. The crew responded by mutinying, stealing the Blessed William, and carrying off the valuable cargo. Kidd was assigned another ship, the Antigua, but then he disappears from history for a year.

He next surfaces in New York City, then the second largest town in North America with a population of just under 5,000. There Kidd met and married Sarah Bradley Cox Oort, a woman twice widowed and very wealthy. The two lived very comfortably together for five years, and Kidd became a member of the highest level of society in the city.

New York City

New York CityFive years later, in 1695 Kidd became involved in a privateering mission to attack pirates in the Indian Ocean. We have no idea what motivated him. Perhaps he was tired of his wife’s company. Perhaps she was tired of his. Or perhaps Kidd was himself approached. We simply don’t know for sure.

The plan was sketchy from the beginning. England was still at war with France, and her international relationship with India had not been good since Henry Avery had attacked a ship carrying a member of the Indian royal family. In addition, pirates inspired by Avery were harassing the East India Company, while at the same time flooding English markets with gold and jewels which may or may not have been Arabian.

The Adventure Galley

The Adventure GalleySo, some of the highest placed men in England planned to build a mighty pirate-hunting ship, captain it with a man of know capabilities, and set it loose in the Indian Ocean, to capture pirate ships and hang wrong-doers. The plan was also to re-acquire plunder taken by the pirates, at a tremendous profit to captain and crew, but more especially to the scheme’s backers, who would fund 80% (£6,000) of the venture while remaining safely in England.

Kidd sailed to England to sign papers and receive his privateering commission. The deal, drawn up by some of the most powerful men in England, was not a standard one. In a normal privateering venture, risk was assumed by everyone. Under Kidd’s agreement, if the venture failed to produce a profit, he himself was liable to repay his bakers. It was also required that the names of the backers remain secret.

He also needed to come up with the other 20% (£1,500) not something that privateer captains were usually required to do. The profits from the venture were to be divided so that the first 10% went to the King, exchange for Kidd’s Royal Commission, and of the remainder, 60% was to go to the anonymous backers, 15% to Kidd and Livingston (the man who had brokered the deal.) The last 25% to be divided among all he members of the crew.

Kidd’s problem was that he didn’t have £1,500.

Livingston, however, also did not want to be caught out if the expedition failed. He introduced a wool merchant named Blackham, who was willing to provide a loan of the upfront money in exchange for 1/3 of Kidd and Livingston's shares. Once again, Kidd signed highly dubious documents, in complete secrecy.

Kidd’s commission, issued by King William himself, instructed Kidd to attack pirates, to attack the French, and to refrain from harming the King’s subjects or allies. Kidd was to leave on his mission as soon as possible, and return by the end of January, 1696.

Next week... Kidd's fateful voyage

Published on February 15, 2016 17:08

February 8, 2016

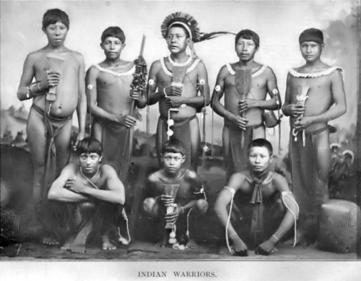

Maroons – A Tradition of Freedom in the Caribbean

One of Christopher Columbus’s first action upon making land in the Caribbean was to enslave several of the natives. He reported to Spain that the people already living in the Caribbean would make good slaves. This was the beginning of European slavery in the New World.

The Spanish, mostly concerned with looting their Caribbean and American lands of gold and silver, learned quickly that the natives did not, in fact, make effective slaves. They perished of European diseases, and often died of simple despair. Europeans put to hard labor in the area did not fare well either. They caught and died of tropical disease, or were unable to survive the hot climate.

By 152, the Spanish were importing African slaves. These people came from a similar climate, and fared well in tropical conditions, and also proved resistant to Caribbean diseases. But almost as soon as they arrived, the Africans began to run away from their Spanish masters.

The Africans could not go home, and because of their obvious racial differences, they could not blend into any European settlement. Instead, they formed small communities in unsettled areas. Often they intermarried with the beleaguered Natives. The people of these mixed communities were called Maroons, from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning escaped, feral, or wild.

Life was difficult for the refugees. The Spanish had taken the best locations for farming and fishing, and the people of Maroon communities often stated out with little besides their own hands and minds. They needed to obtain tools and seeds for farming, home building and hunting. They often did this by raiding Spanish settlements, and soon the Spanish began to fear them.

On the smaller island, the Spanish were able to defeat the Maroons, but on larger islands, such as Jamaica, the former slaves were able to form permanent communities in the mountains. From these outposts, they raided plantations, carrying on guerilla warfare.

Many of the early leaders of the Maroons are recorded in island history. François Mackandal, a houngan, or voodoo priest, who led a six-year rebellion against the white plantation owners in Haiti that preceded the Haitian Revolution.

In Cuba, maroon communities also survived in the mountains, where African refugees who escaped slavery and joined refugee members of the Taínos tribe. Before roads were built into the mountains of Puerto Rico, tough plant growth kept many escaped maroons hidden in the southwestern hills. Escaped Blacks also sought refuge away from the coastal plantations near the city of Ponce. Remnants of these communities remain to this day.

Maroon communities emerged in many places in the Caribbean - St. Vincent and Dominica, for example. But nowhere were they more successful than on the island of Jamaica. The island was originally Spanish, but the British captured it in 1655.

Originally the Maroon leader Juan de Bolas supported the Spanish, but in 1659 he allied himself with the British and guided their troops on a raid which finally expelled the Spanish in 1660. In return, in 1663, Governor Lyttleton signed the first Maroon treaty granting de Bolas and his people land on the same terms as British settlers.

Other groups of Maroons remained independent, living in Jamaica’s mountains and supporting themselves by farming and occasional raids on plantations.

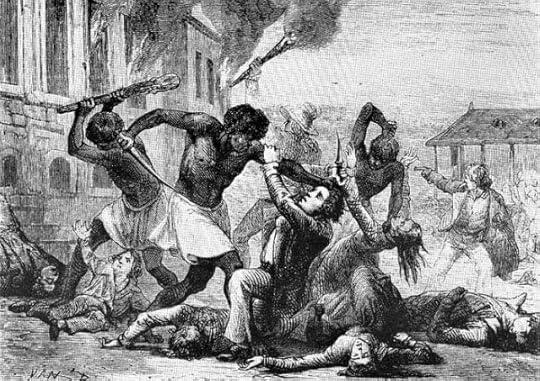

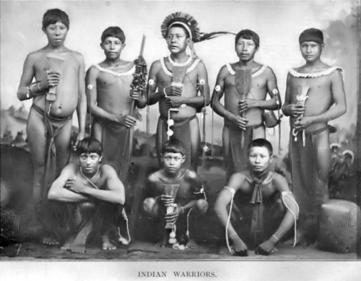

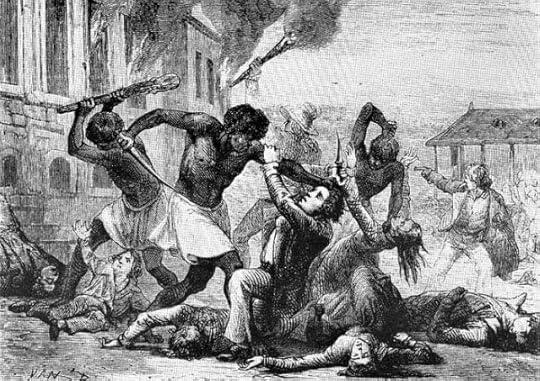

Between 1673 and 1690 there were several major slave uprisings, mainly involving newly arrived groups of slaves who had a background of soldiers in Africa. On July 31st 1690, a rebellion of 500 slaves from the Sutton estate in Clarendon Parish led to the formation of Jamaica’s most stable and best organized maroon group.

Although many of these rebels were killed, recaptured or surrendered, more than 200, including women and children, remained free after the rebellion. They established an African style government for their group. This group only accepted new members after a strict probationary period. Their most famous leader was named Cudjoe, but it should be noted that Cudjoe is a very common name in the African culture that gave this group of Maroons their origin. Several other Jamaican Maroon leaders had the same name.

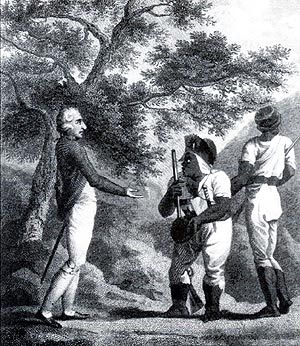

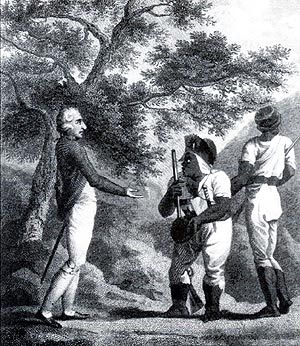

Captain Cudjoe negotiating with the British

Captain Cudjoe negotiating with the British

Another famous – some would say legendary – Maroon leader is the woman know as Nanny, also called Queen Nanny. She is today a folk hero, the only woman listed as one of Jamaica’s National Heroes. Legends say that she was a citizen of a Ghana, Africa, whose entire village was captured in an intertribal war and sold to the Europeans.

Other stories say that she came to Jamaica as a free woman. However she arrived, by 1720 she was the leader of a group of Maroons settled in Jamaica’s Blue Mountains. She was a folk healer, a priestess, and the founder of a settlement called Nanny Town. This community was so well located that direct attacks on it by the British Army failed. She was a master of guerilla warfare, and is credited with freeing over 1000 slaves and integrating them into Maroon society.

Nanny

Nanny

Nanny’s death is recorded in 1733, but in 1739 the British, tired of fighting the maroons, ceded 500 acres to land “to Nanny and her descendants.” This became the location of Nanny Town. Her death is also recorded at various times during the 1760’s.

Maroon settlements usually speak Creole languages a mix of European tongues and the original African languages of their members. At other times, the Maroons would adopt variations of local European language as a common tongue, because members of the community spoke a variety of mother tongues.

They kept African religions, traditions and holidays. They also kept alive African drumming traditions.

Modern day Maroons

Modern day Maroons

Some of the Maroon communities have survived for centuries. Eleven Maroon settlements remain on land given to them in the original treaty with the British. These Maroons still maintain their traditional celebrations and practices.

Island tourists are allowed to attend many of these events, while others are held in secret and shrouded in mystery. Singing, dancing, drum-playing and preparation of traditional foods form a central part of most gatherings. In their largest town, Accompong, Maroons still possess a vibrant community of about 600. Tours of the village are offered and a large festival is put on every 6 January to commemorate the signing of the peace treaty with the British.

2012 Mama G, a Maroon spiritual leader, dances with a young man

2012 Mama G, a Maroon spiritual leader, dances with a young man

The Spanish, mostly concerned with looting their Caribbean and American lands of gold and silver, learned quickly that the natives did not, in fact, make effective slaves. They perished of European diseases, and often died of simple despair. Europeans put to hard labor in the area did not fare well either. They caught and died of tropical disease, or were unable to survive the hot climate.

By 152, the Spanish were importing African slaves. These people came from a similar climate, and fared well in tropical conditions, and also proved resistant to Caribbean diseases. But almost as soon as they arrived, the Africans began to run away from their Spanish masters.

The Africans could not go home, and because of their obvious racial differences, they could not blend into any European settlement. Instead, they formed small communities in unsettled areas. Often they intermarried with the beleaguered Natives. The people of these mixed communities were called Maroons, from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning escaped, feral, or wild.

Life was difficult for the refugees. The Spanish had taken the best locations for farming and fishing, and the people of Maroon communities often stated out with little besides their own hands and minds. They needed to obtain tools and seeds for farming, home building and hunting. They often did this by raiding Spanish settlements, and soon the Spanish began to fear them.

On the smaller island, the Spanish were able to defeat the Maroons, but on larger islands, such as Jamaica, the former slaves were able to form permanent communities in the mountains. From these outposts, they raided plantations, carrying on guerilla warfare.

Many of the early leaders of the Maroons are recorded in island history. François Mackandal, a houngan, or voodoo priest, who led a six-year rebellion against the white plantation owners in Haiti that preceded the Haitian Revolution.

In Cuba, maroon communities also survived in the mountains, where African refugees who escaped slavery and joined refugee members of the Taínos tribe. Before roads were built into the mountains of Puerto Rico, tough plant growth kept many escaped maroons hidden in the southwestern hills. Escaped Blacks also sought refuge away from the coastal plantations near the city of Ponce. Remnants of these communities remain to this day.

Maroon communities emerged in many places in the Caribbean - St. Vincent and Dominica, for example. But nowhere were they more successful than on the island of Jamaica. The island was originally Spanish, but the British captured it in 1655.

Originally the Maroon leader Juan de Bolas supported the Spanish, but in 1659 he allied himself with the British and guided their troops on a raid which finally expelled the Spanish in 1660. In return, in 1663, Governor Lyttleton signed the first Maroon treaty granting de Bolas and his people land on the same terms as British settlers.

Other groups of Maroons remained independent, living in Jamaica’s mountains and supporting themselves by farming and occasional raids on plantations.

Between 1673 and 1690 there were several major slave uprisings, mainly involving newly arrived groups of slaves who had a background of soldiers in Africa. On July 31st 1690, a rebellion of 500 slaves from the Sutton estate in Clarendon Parish led to the formation of Jamaica’s most stable and best organized maroon group.

Although many of these rebels were killed, recaptured or surrendered, more than 200, including women and children, remained free after the rebellion. They established an African style government for their group. This group only accepted new members after a strict probationary period. Their most famous leader was named Cudjoe, but it should be noted that Cudjoe is a very common name in the African culture that gave this group of Maroons their origin. Several other Jamaican Maroon leaders had the same name.

Captain Cudjoe negotiating with the British

Captain Cudjoe negotiating with the BritishAnother famous – some would say legendary – Maroon leader is the woman know as Nanny, also called Queen Nanny. She is today a folk hero, the only woman listed as one of Jamaica’s National Heroes. Legends say that she was a citizen of a Ghana, Africa, whose entire village was captured in an intertribal war and sold to the Europeans.

Other stories say that she came to Jamaica as a free woman. However she arrived, by 1720 she was the leader of a group of Maroons settled in Jamaica’s Blue Mountains. She was a folk healer, a priestess, and the founder of a settlement called Nanny Town. This community was so well located that direct attacks on it by the British Army failed. She was a master of guerilla warfare, and is credited with freeing over 1000 slaves and integrating them into Maroon society.

Nanny

NannyNanny’s death is recorded in 1733, but in 1739 the British, tired of fighting the maroons, ceded 500 acres to land “to Nanny and her descendants.” This became the location of Nanny Town. Her death is also recorded at various times during the 1760’s.

Maroon settlements usually speak Creole languages a mix of European tongues and the original African languages of their members. At other times, the Maroons would adopt variations of local European language as a common tongue, because members of the community spoke a variety of mother tongues.

They kept African religions, traditions and holidays. They also kept alive African drumming traditions.

Modern day Maroons

Modern day MaroonsSome of the Maroon communities have survived for centuries. Eleven Maroon settlements remain on land given to them in the original treaty with the British. These Maroons still maintain their traditional celebrations and practices.

Island tourists are allowed to attend many of these events, while others are held in secret and shrouded in mystery. Singing, dancing, drum-playing and preparation of traditional foods form a central part of most gatherings. In their largest town, Accompong, Maroons still possess a vibrant community of about 600. Tours of the village are offered and a large festival is put on every 6 January to commemorate the signing of the peace treaty with the British.

2012 Mama G, a Maroon spiritual leader, dances with a young man

2012 Mama G, a Maroon spiritual leader, dances with a young man

Published on February 08, 2016 14:05

February 1, 2016

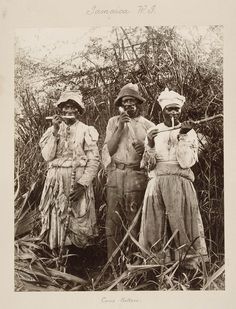

The Pirate Treasure of Sugar

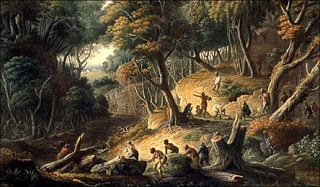

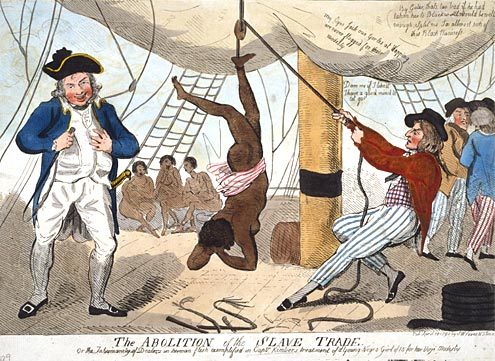

As this blog has discussed many times before, pirates stole not only gold and silver, but shipments of merchant goods as well. Of course, they chose the most valuable goods on a captured ship, and one of the most valuable trade goods was sugar.

[image error]

Sugar was not native to the New World. It had been domesticated, probably in New Guinea about ten thousand years ago. Trade in sugar quickly moved to Southeast Asia and China, and then to India, where people first discovered how to make the kind of granulated sugar that we buy in the store today. (Before this, people had just chewed on the stalks of sugar cane, enjoying the sweet juice.)

Trade with the Arabs brought the sweet stuff to Europe, but sugar did not grow well in the European climate. Demand for sugar was high, however, so Christopher Columbus carried cuttings of sugar cane with him on his second voyage. The plants flourished in the tropical climate of Hispaniola, and sugar became part of the Caribbean landscape.

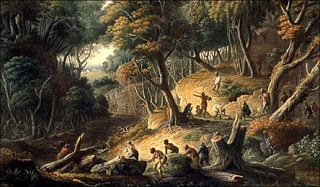

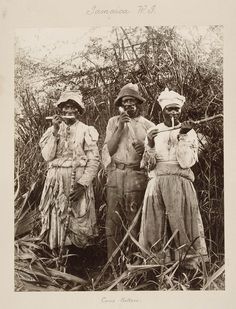

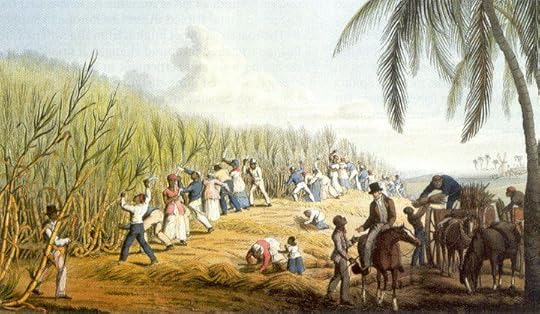

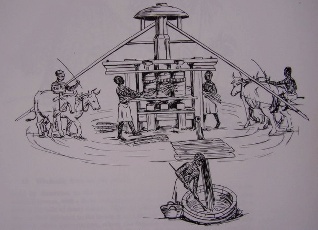

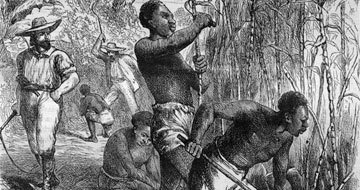

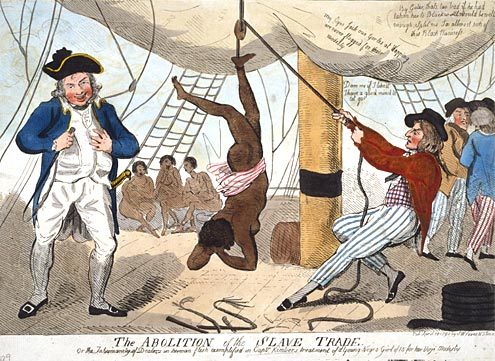

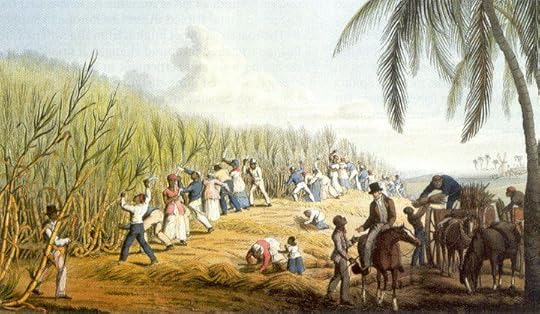

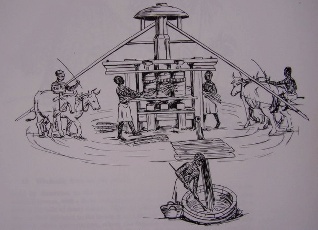

Sugar cane is a tall, grass-like plant that looks similar to bamboo. It has shallow roots, and long, flat green leaves with a serrated edge. During our time period, sugar cane was cultivated and harvested by hand, the harvesting done with machetes. The cane stalks were then stripped of their leaves and rough chopped, and the cane stalks were put into a mill.

The mill used a stone wheel, driven either by harnessed animals or by slave labor, which crushed the stalks. This released the sweet sugar sap, which was drained, collected, refined and boiled until the water evaporated and it became crystallized sugar.

Sugar refining has progressed over the years, and the product produced during the Golden Age of Piracy was a slightly sticky product, pale, but not as white as today’s sugar. Nevertheless, it was called “white gold” and quickly became the source of enormous profit.

Today, the average American eats an average of 100 pounds of sugar a year. In 1700, the average was closer to 4 pounds per year. But this was very much stratified by income. A single pound of sugar cost as much a laborer made in two days. Archeologists can determine the income level of bodies from the early 1700’s by looking at the teeth. Sugar consumption meant that the bodies of the rich had badly decomposed teeth. Poor people (like pirates) had healthy, white teeth in comparison.

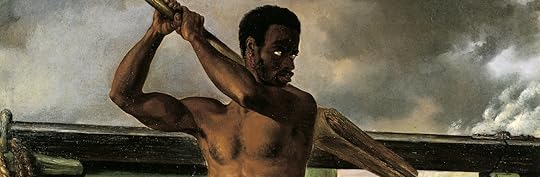

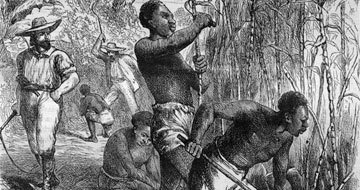

The problem was that no sane person wanted to cultivate sugar cane. Because only the juice was used from the plant, vast fields were needed to produce a profit. Because heavy equipment was needed to extract the juice and refine it, it was a rich person’s game. And the work of growing and harvesting the cane was brutal.

The tall cane stalks provided little shade for workers, while blocking any available breeze. Cane leaves were sharp on the edges, and cut the skin. The labor of cutting the stalks, stripping the leaves and carrying stalks to the grinder was exhausting. And the boiling kettles, often in the open under a tropical sun, produced killing temperatures.

Small family farms simply could not do this. So, large plantations, powered by slaves, became the norm. Barbados was the most valuable colony in the English empire because of its sugar production, and as sugar spread, the slave society grew with it.

In the very early days, slaves were often Irish rebels, or poor British citizens, transported to the Caribbean because of minor crimes. But these people simply could not stand the heat and the sun. (Remember, sunblock would not be invented until 1936.) Plantation owners quickly switched to kidnapped Africans, who worked 18 hours a day in the cane fields. It is estimated that the average life expectancy of a slave in the cane field was two years.

The plantation owners, surrounded and outnumbered by slaves, were constantly nervous. They feared slave uprisings, and demanded armed support from the government. This in turn supported the militarization of the English colonies.

The slaves, meanwhile, worked to death, created horror stories in which dead slaves were raised to work on after they had been laid to rest. These “zombies” still permeate modern mythology.

Undead worker from a movie "The White Zombie" 1932

Undead worker from a movie "The White Zombie" 1932

Sugar, as a luxury item, was also heavily taxed. England valued its sugar-producing colonies more than its mainland colonies because of the income they produced. It’s even been argued that England didn’t put its full effort behind fighting the American Revolution because they were busy defending Barbados from smugglers and pirates.

Pirates probably ate the sugar that they captured, but recipes containing sugar were still somewhat rare. Cany usually consisted of seeds or small fruits dipped in sugar and dried. Sugar was consumed in tea and coffee. Jams and jellies – fruit preserved by sugar – was just becoming popular, but pirates probably didn’t have the means to create these, and would have just consumed any such products they captured.

Rum and sugar production go hand in hand, since rum is made of the waste products of the sugar manufacturing industry. Molasses – unrefined sugar cane juice – is fermented into rum. In approximately our period (about 1700) Barbados alone was producing approximately 467,000 gallons of rum a year.

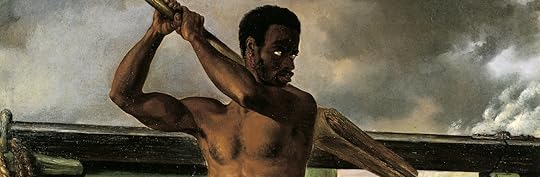

So that’s the basic situation. Pirates drank rum produced by sugar producers, captured ships laden with sugar and sold the sugar at a discount to merchants who had a ready market for it. Slaves – either escaped from sugar plantations or liberated by pirates from captured ships swelled the ranks of the pirates, and pirates dined in fine style on sugar products. In some instances, pirates even supported slave uprisings on sugar plantations.

The situation in which a few lucky individuals owned most of the resources, and the vast majority of people owned little or nothing fueled the fires of piracy and stirred men into desperate rebellion. Sugar shaped the Caribbean, and the Caribbean shaped the pirates.

[image error]

Sugar was not native to the New World. It had been domesticated, probably in New Guinea about ten thousand years ago. Trade in sugar quickly moved to Southeast Asia and China, and then to India, where people first discovered how to make the kind of granulated sugar that we buy in the store today. (Before this, people had just chewed on the stalks of sugar cane, enjoying the sweet juice.)

Trade with the Arabs brought the sweet stuff to Europe, but sugar did not grow well in the European climate. Demand for sugar was high, however, so Christopher Columbus carried cuttings of sugar cane with him on his second voyage. The plants flourished in the tropical climate of Hispaniola, and sugar became part of the Caribbean landscape.

Sugar cane is a tall, grass-like plant that looks similar to bamboo. It has shallow roots, and long, flat green leaves with a serrated edge. During our time period, sugar cane was cultivated and harvested by hand, the harvesting done with machetes. The cane stalks were then stripped of their leaves and rough chopped, and the cane stalks were put into a mill.

The mill used a stone wheel, driven either by harnessed animals or by slave labor, which crushed the stalks. This released the sweet sugar sap, which was drained, collected, refined and boiled until the water evaporated and it became crystallized sugar.

Sugar refining has progressed over the years, and the product produced during the Golden Age of Piracy was a slightly sticky product, pale, but not as white as today’s sugar. Nevertheless, it was called “white gold” and quickly became the source of enormous profit.

Today, the average American eats an average of 100 pounds of sugar a year. In 1700, the average was closer to 4 pounds per year. But this was very much stratified by income. A single pound of sugar cost as much a laborer made in two days. Archeologists can determine the income level of bodies from the early 1700’s by looking at the teeth. Sugar consumption meant that the bodies of the rich had badly decomposed teeth. Poor people (like pirates) had healthy, white teeth in comparison.

The problem was that no sane person wanted to cultivate sugar cane. Because only the juice was used from the plant, vast fields were needed to produce a profit. Because heavy equipment was needed to extract the juice and refine it, it was a rich person’s game. And the work of growing and harvesting the cane was brutal.

The tall cane stalks provided little shade for workers, while blocking any available breeze. Cane leaves were sharp on the edges, and cut the skin. The labor of cutting the stalks, stripping the leaves and carrying stalks to the grinder was exhausting. And the boiling kettles, often in the open under a tropical sun, produced killing temperatures.

Small family farms simply could not do this. So, large plantations, powered by slaves, became the norm. Barbados was the most valuable colony in the English empire because of its sugar production, and as sugar spread, the slave society grew with it.

In the very early days, slaves were often Irish rebels, or poor British citizens, transported to the Caribbean because of minor crimes. But these people simply could not stand the heat and the sun. (Remember, sunblock would not be invented until 1936.) Plantation owners quickly switched to kidnapped Africans, who worked 18 hours a day in the cane fields. It is estimated that the average life expectancy of a slave in the cane field was two years.

The plantation owners, surrounded and outnumbered by slaves, were constantly nervous. They feared slave uprisings, and demanded armed support from the government. This in turn supported the militarization of the English colonies.

The slaves, meanwhile, worked to death, created horror stories in which dead slaves were raised to work on after they had been laid to rest. These “zombies” still permeate modern mythology.

Undead worker from a movie "The White Zombie" 1932

Undead worker from a movie "The White Zombie" 1932Sugar, as a luxury item, was also heavily taxed. England valued its sugar-producing colonies more than its mainland colonies because of the income they produced. It’s even been argued that England didn’t put its full effort behind fighting the American Revolution because they were busy defending Barbados from smugglers and pirates.

Pirates probably ate the sugar that they captured, but recipes containing sugar were still somewhat rare. Cany usually consisted of seeds or small fruits dipped in sugar and dried. Sugar was consumed in tea and coffee. Jams and jellies – fruit preserved by sugar – was just becoming popular, but pirates probably didn’t have the means to create these, and would have just consumed any such products they captured.

Rum and sugar production go hand in hand, since rum is made of the waste products of the sugar manufacturing industry. Molasses – unrefined sugar cane juice – is fermented into rum. In approximately our period (about 1700) Barbados alone was producing approximately 467,000 gallons of rum a year.

So that’s the basic situation. Pirates drank rum produced by sugar producers, captured ships laden with sugar and sold the sugar at a discount to merchants who had a ready market for it. Slaves – either escaped from sugar plantations or liberated by pirates from captured ships swelled the ranks of the pirates, and pirates dined in fine style on sugar products. In some instances, pirates even supported slave uprisings on sugar plantations.

The situation in which a few lucky individuals owned most of the resources, and the vast majority of people owned little or nothing fueled the fires of piracy and stirred men into desperate rebellion. Sugar shaped the Caribbean, and the Caribbean shaped the pirates.

Published on February 01, 2016 12:17

January 25, 2016

Season 3 of Black Sails

Well, it’s January again, and for the third time, we’re welcoming the opening shots of Starz’ bloody, violent, sexy pirate series, Black Sails!

[image error]

Last season’s overriding theme was that the world the pirates left behind – the world of “law and order” – is not such a nice place. 18th century society was based on position drawn from birth, cash on hand, and complete intolerance of anything the least bit out of the ordinary. (The crowning injustice being the incarceration of one of the characters for the crime of being gay, and the ruination of the character’s family and associates. Actual historical practice would have hanged all participants in the gay sex, so the series’ Death-by-Incarceration-in-a-Brutal-Mental-Institution was actually quite merciful.)

At the end of Season 2, the pirates also realized, to quote the famous pirate associate Benjamin Franklin, “We must all hang together or we will hang separately.” No matter how much the Nassau pirates dislike each other, they must overcome their differences if they are to survive.

Season 3 opens with the problem of repairing Fort Nassau, the repository of the massive haul of gold won from the Spanish ship Urca. With plenty of cash and plenty of booze and women, the working-class pirates just aren’t interested in the hard drudgery of repairing their fortifications.

So, while the mad pirate Flint (the fictional Flint, from Robert Lewis Stevenson’s Treasure Island) sails up and down the east coast of what will someday be the US, murdering any magistrate who dares to hang a pirate, Jack Rackham and Charles Vane (based on real-life pirates of the same names from the Golden Age) try to scare up some labor to repair the fort.

The easy answer is to employ slaves. But they run into a problem or morals. These pirates are fighting for freedom. Is it moral for them to use slaves (captured as cargo on the high seas) to further their own ends? This is when the series is at its best, when the real life personalities and the problems of real pirates come to the fore.