T.S. Rhodes's Blog, page 12

January 4, 2016

Message in a Bottle

One of the iconic images in a nautical world is a message in a bottle. Bottles have carried dying words, requests of rescue, love letters, and even military secrets. They have brought light to the world as part of scientific research, and they have been part of sordid schemes to bilk people out of money.

[image error]

The earliest “message in a bottle” was created by the Greek philosopher Theophrastos in 310 BC. This was an early scientific experiment – Theophrastos theorized that the Mediterranean Sea was connected to the Atlantic, and to that end he sealed messages in several wine jars and threw them into the sea near his home. The drifting jars did indeed prove that the two bodies of water were connected. While it’s not as romantic as a lonely bottle, the jars are the precursor to many 18thand 19th century experiments.

For hundreds of years, notes in bottles were used to chart ocean currents. A typical example would include a pre-addressed postcard and either a blank check or the promise of a small reward if the finder noted the location where the bottle had been found and mailed the card. Today we use floating electronics to do the same job. This provides a detailed account of where the current has gone, and not just where it touched shore. But it’s not quite as romantic.

Christopher Columbus sent a more traditional message while returning to Spain after his first voyage to the New World. Caught in a severe storm, Columbus feared that his ship would go down and the news of his discovery would be forever lost when he and his shipmates drowned.

Columbus sealed a message, including details of his voyage and discovery, along with a request that the finder transport it to the Queen of Castile, into a cask, and threw it overboard. Columbus got lucky and made it through the storm, but the message didn’t fare so well. Lost, sunk or washed ashore in a country that couldn’t read the message, the cask was never heard from again.

By the 15thcentury, bottles carried military secrets. By this time, many ocean currents were mapped and well understood. English ships spying on the French or the Spanish sealed messages of their discoveries into bottles and tossed them into known currents, intending them to be washed ashore in England. Details of the scheme are hard to discover, but Queen Elizabeth I designated a post of “Uncorker of Ocean Bottles” and made message-bottle opening by any other person an offense punishable by death.

In 1784, Chunosuke Matsuyama set out to sea with 43 friends, hoping to find adventure and treasure. They did not make it far. A storm ripped the sails to pieces, broke the masts, and drive the ship onto the coral reef near a tiny island. Matsuyama and his friends waded to shore, but the island was barren. There was no water, and only a few coconut trees and tiny crabs.

As his friends slowly succumbed to hunger and thirst, Matsuyama realized he would never see home again. He found a bottle in the ship’s wreckage, pried a strip of wood from a coconut tree and carved a message onto it. Then he sealed it in the bottle and cast it as far as he could into the sea.

The bottle drifted for 151 years. It was finally found by a seaweed collector near the village of Hiraturemura, the birthplace of Chunosuke Matsuyama.

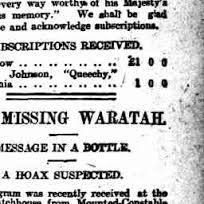

The case of the Waratah illustrates how people seek to profit from false messages. The Waratah left South Africa for Australia in 1909, but never arrived at its destination. For months, ships searched for any sing of the vessel. But in a time before shipboard radios, the fate of the ship was marked as simply “missing at sea.”

Over the next few years, dozens of letters about the Waratah came to Lloyd's of London, the famous insurer of shipping. These letters enclosed notes about the sinking. The letter-writers claimed to have found these letters in floating bottles.

But the insurance company said that all these notes were fakes. The names and address of the lost sailors had been printed in newspapers, and glory-seekers used this information to fabricate the notes. How did they know? For one thing none of the notes told the same story. For another, they were all suspiciously complete.

One note was proven genuine. Found five years after the event, the bottle washed up on the other side of the Atlantic, near a seacoast village in Scotland. It said simply “Top heavy, one side awash. Goodbye mother and sister – Charlie M’Fell, greaser.”

The handwriting on the note matched that of a man names Charles M’Fell, whose main job was keeping the moving parts of the ship’s engines lubricated. Charles did indeed have a mother and sister. His last note to them was poignant and brief.

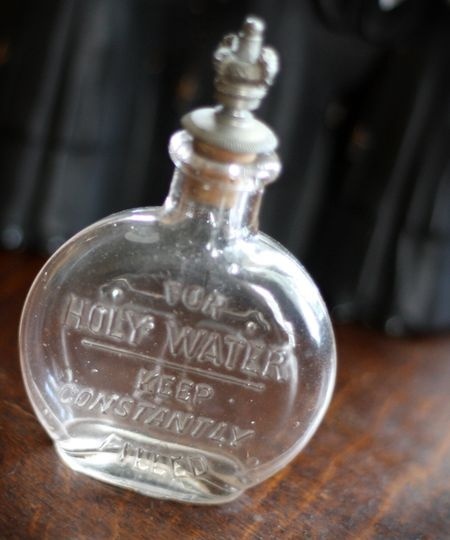

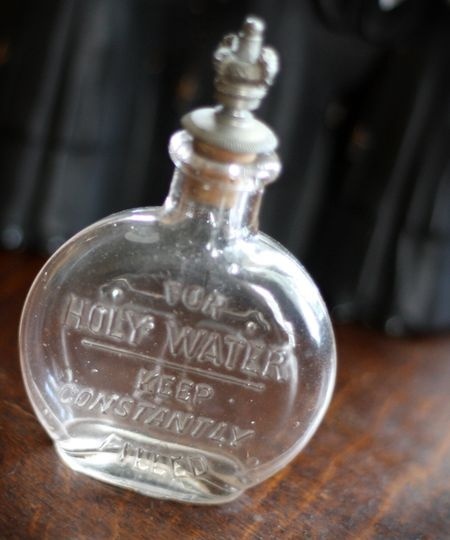

One message in a bottle was actually sent from the Titanic. An Irishman named 19-year-old Jeremiah Burke, traveling to America with a cousin, penned "From Titanic, goodbye all, Burke of Glanmire, Cork,” on a scrap of paper. He then emptied a bottle of Holy Water his mother had given him before he set sail, sealed the note in it and cast it forth into the waves. The bottle took a year to reach shore, but landed only a few miles from Burke’s home. Burke’s mother had already died of a broken heart over the loss of her son.

In 1957 Sebastiano Puzzo, a Sicilian factory worker, found a bottle with a note washed up on the shore. The note was in English, which he could not read. But his 18-year-old daughter had studied English.

The daughter, Paolina, read a note from Ake Viking, a Swedish sailor who was looking for love. Ake asked that, if any eligible young woman found the note, that she should write a reply and send it by mail, answering the question “Do you want to marry a handsome blonde Swede?”

Ake’s address and picture were attached to the note. Paolina replied, mostly as a joke. But a relationship between the two sprang up, and some months later the two were married.

Messages in bottles still occasionally make the news. In 2005, more than 80 migrants were abandoned on a crippled boat off the coast of Costa Rica. These passengers were being illegally smuggled by the ship’s crew, who left them with the vessel when it became disabled. Adrift without any means of typical communication, the passengers popped an SOS into a bottle and cast it adrift. The message, “Please help us,” was found by fishermen who delivered it to a nearby World Heritage site island. The workers there alerted their headquarters, the lost-at-sea drifters were rescued, and the group was taken to the island to recover.

[image error]

The earliest “message in a bottle” was created by the Greek philosopher Theophrastos in 310 BC. This was an early scientific experiment – Theophrastos theorized that the Mediterranean Sea was connected to the Atlantic, and to that end he sealed messages in several wine jars and threw them into the sea near his home. The drifting jars did indeed prove that the two bodies of water were connected. While it’s not as romantic as a lonely bottle, the jars are the precursor to many 18thand 19th century experiments.

For hundreds of years, notes in bottles were used to chart ocean currents. A typical example would include a pre-addressed postcard and either a blank check or the promise of a small reward if the finder noted the location where the bottle had been found and mailed the card. Today we use floating electronics to do the same job. This provides a detailed account of where the current has gone, and not just where it touched shore. But it’s not quite as romantic.

Christopher Columbus sent a more traditional message while returning to Spain after his first voyage to the New World. Caught in a severe storm, Columbus feared that his ship would go down and the news of his discovery would be forever lost when he and his shipmates drowned.

Columbus sealed a message, including details of his voyage and discovery, along with a request that the finder transport it to the Queen of Castile, into a cask, and threw it overboard. Columbus got lucky and made it through the storm, but the message didn’t fare so well. Lost, sunk or washed ashore in a country that couldn’t read the message, the cask was never heard from again.

By the 15thcentury, bottles carried military secrets. By this time, many ocean currents were mapped and well understood. English ships spying on the French or the Spanish sealed messages of their discoveries into bottles and tossed them into known currents, intending them to be washed ashore in England. Details of the scheme are hard to discover, but Queen Elizabeth I designated a post of “Uncorker of Ocean Bottles” and made message-bottle opening by any other person an offense punishable by death.

In 1784, Chunosuke Matsuyama set out to sea with 43 friends, hoping to find adventure and treasure. They did not make it far. A storm ripped the sails to pieces, broke the masts, and drive the ship onto the coral reef near a tiny island. Matsuyama and his friends waded to shore, but the island was barren. There was no water, and only a few coconut trees and tiny crabs.

As his friends slowly succumbed to hunger and thirst, Matsuyama realized he would never see home again. He found a bottle in the ship’s wreckage, pried a strip of wood from a coconut tree and carved a message onto it. Then he sealed it in the bottle and cast it as far as he could into the sea.

The bottle drifted for 151 years. It was finally found by a seaweed collector near the village of Hiraturemura, the birthplace of Chunosuke Matsuyama.

The case of the Waratah illustrates how people seek to profit from false messages. The Waratah left South Africa for Australia in 1909, but never arrived at its destination. For months, ships searched for any sing of the vessel. But in a time before shipboard radios, the fate of the ship was marked as simply “missing at sea.”

Over the next few years, dozens of letters about the Waratah came to Lloyd's of London, the famous insurer of shipping. These letters enclosed notes about the sinking. The letter-writers claimed to have found these letters in floating bottles.

But the insurance company said that all these notes were fakes. The names and address of the lost sailors had been printed in newspapers, and glory-seekers used this information to fabricate the notes. How did they know? For one thing none of the notes told the same story. For another, they were all suspiciously complete.

One note was proven genuine. Found five years after the event, the bottle washed up on the other side of the Atlantic, near a seacoast village in Scotland. It said simply “Top heavy, one side awash. Goodbye mother and sister – Charlie M’Fell, greaser.”

The handwriting on the note matched that of a man names Charles M’Fell, whose main job was keeping the moving parts of the ship’s engines lubricated. Charles did indeed have a mother and sister. His last note to them was poignant and brief.

One message in a bottle was actually sent from the Titanic. An Irishman named 19-year-old Jeremiah Burke, traveling to America with a cousin, penned "From Titanic, goodbye all, Burke of Glanmire, Cork,” on a scrap of paper. He then emptied a bottle of Holy Water his mother had given him before he set sail, sealed the note in it and cast it forth into the waves. The bottle took a year to reach shore, but landed only a few miles from Burke’s home. Burke’s mother had already died of a broken heart over the loss of her son.

In 1957 Sebastiano Puzzo, a Sicilian factory worker, found a bottle with a note washed up on the shore. The note was in English, which he could not read. But his 18-year-old daughter had studied English.

The daughter, Paolina, read a note from Ake Viking, a Swedish sailor who was looking for love. Ake asked that, if any eligible young woman found the note, that she should write a reply and send it by mail, answering the question “Do you want to marry a handsome blonde Swede?”

Ake’s address and picture were attached to the note. Paolina replied, mostly as a joke. But a relationship between the two sprang up, and some months later the two were married.

Messages in bottles still occasionally make the news. In 2005, more than 80 migrants were abandoned on a crippled boat off the coast of Costa Rica. These passengers were being illegally smuggled by the ship’s crew, who left them with the vessel when it became disabled. Adrift without any means of typical communication, the passengers popped an SOS into a bottle and cast it adrift. The message, “Please help us,” was found by fishermen who delivered it to a nearby World Heritage site island. The workers there alerted their headquarters, the lost-at-sea drifters were rescued, and the group was taken to the island to recover.

Published on January 04, 2016 19:05

December 28, 2015

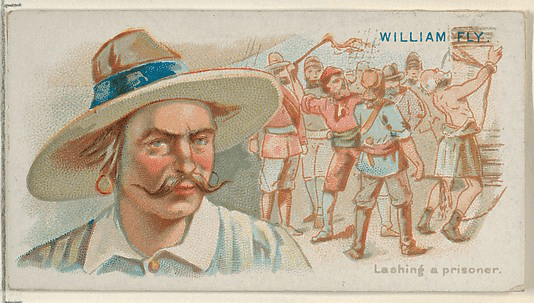

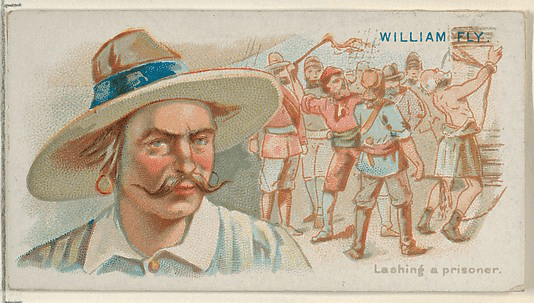

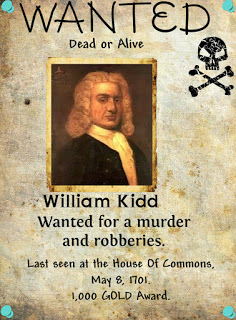

Captain William Fly, Die Hard Pirate

The exact end of the Golden Age of Piracy is a matter of debate. For a long time, I have thought that the death of Calico Jack Rackham (November 18th 1720) ended the most important pirating adventures of the Golden Age. But for sheer rage and pirating spirit, I have come to believe that Captain William Fly extended the Golden Age by sheer force of will.

Fly had a short career. Like most pirates, his birth date is uncertain, though he is believed to have come from Jamaica. There are no records of Fly having in his past any sort of family connections or respectable trade. The earliest reports of him list his occupation as “prize fighter,” a remarkable fact, given the history of prize-fighting at the time.

Simply put, fighters of the time used no safety equipment, and there were no rules. Biting was common (many men lost ears or noses.) Eye gouging was acceptable, and scooping an opponent’s eye from its socket was an art form. It was perfectly legal to punch or even kick below the waist, grapple, and stomp on a downed opponent. Only the very tough and/or the very desperate took up this kind of thing as a profession.

It’s safe to say, William Fly came from a poor family.

Fly, however, was not maimed, and quit the game to become a sailor. Once again, we don’t know how long he worked at this profession before he came to the attention of the authorities. We do know that he was rated as bosun, a responsible supervisory position, when he shipped out with Captain James (John) Green of board the Elizabeth in 1726.

Contemporary accounts say that Fly wanted to make a fortune, and that he had become a fighter to win one. These same accounts say that Fly turned to piracy as a get-rich-quick scheme, and hint that this was the only reason he took up work as a sailor.

But the fact that he was rated as bosun indicates that this was not the case. While ship’s captains sometimes held their positions due to family connections or financial investment in the ship, men with “blue collar” positions such as bosun need to be skilled at their jobs in order to make the ship work. A bosun scheduled work crews, and maintained the deck, ropework, and sails of the ship. Since a ship of the day contained literally miles of rope, each piece with a distinctive name and function, and had a wide variety of sails that needed to be constantly raised, lowered and adjusted due to wind and weather, this was not a job that could be mastered in only a few months.

Contemporary accounts also claim that Fly became a pirate because he was too “lazy” to work as a regular sailor. However, these accounts do not explain how, if this was the case, Fly persuaded the entire crew of the Elizabeth to mutiny.

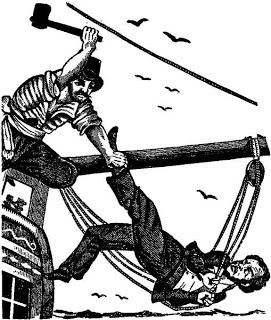

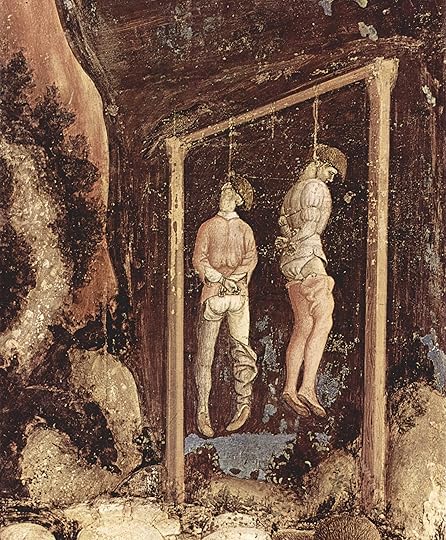

I believe that it is significant that the captain, Green, was lying drunk in his bed when the mutineers woke him and dragged him on deck. They seem to have been in a rage, though the cause of this has never been explained. Certainly some merchant captains abused their men terribly. Whatever drove Fly and the Elizabeth’s crew to mutiny, they lost no time in throwing Green and his first mate, Thomas Jenkins, into the sea.

This in itself was an unusually violent act. During other mutinies from the period, captains were put off in the ship’s boat, or left on a deserted coast. In fact, during at least one mutiny, the mutineers merely took the ship back to port and got off, and went looking for other work..

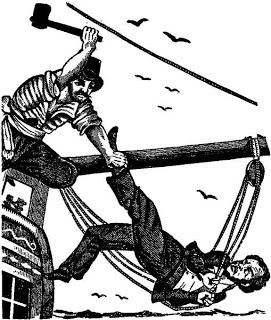

So Fly and his men were enraged. After drowning their former captain and first mate (neither of whom went down easily, and both of whom had to be beaten off the side of the ship with weapons) they made a big batch of alcoholic punch, and drank it while deciding what to do next.

The men elected Fly, the logical next in command, to the title of captain, and decided to become pirates. They created a Jolly Roger flag, renamed the ship Fame’s Revenge and began robbing ships between South Carolina and Boston.

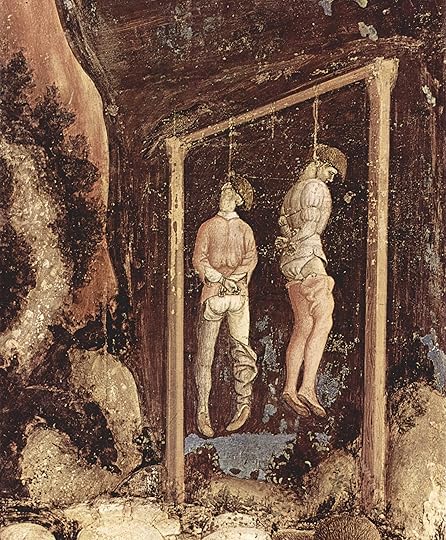

By this time, however, the authorities were in full pursuit of pirates. William Fly and the Fame’s Revenge lasted in their career only three months before they were captured and brought to trial in Boston.

It was here that Fly showed his metal as a pirate.

While held in prison, he was visited by none other than Cotton Mather, the famous puritan preacher, notorious for his prosecution of witches during the Salem Witch trials. Mather tried in vain to persuade Fly to recant his sins, to confess, or even to attend church services during his confinement in order to be spared the fires of hell.

Cotton Mather Fly replied that he hated the church almost as much as he hated the current social structure, and that he would go to his death as a brave fellow. On the day of his hanging, Fly leaped willing into the cart that would carry him to the scaffold in the town square, and bantered with the spectators along the way.

Cotton Mather Fly replied that he hated the church almost as much as he hated the current social structure, and that he would go to his death as a brave fellow. On the day of his hanging, Fly leaped willing into the cart that would carry him to the scaffold in the town square, and bantered with the spectators along the way.

Once on the scaffold, Fly took one look at the hangman’s noose awaiting him, berated the hangman for doing a sloppy job, re-tied the knot himself, and placed it around his own neck. He then berated the crowd.

Fly stated, in short, that selfish owners and brutal captains brought piracy down upon themselves, and that if seamen were paid on time, and treated like human beings, piracy would not exist. He is quoted as concluding: "Our Captain and his Mate used us Barbarously. We poor Men can’t have Justice done us. There is nothing said to our Commanders, let them never so much abuse us, and use us like Dogs."

William Fly and two of his fellow pirates were hanged on July 142 1726. A true pirate to the last, Fly urged all working class folks to stand up for themselves. May his legacy live on.

Fly had a short career. Like most pirates, his birth date is uncertain, though he is believed to have come from Jamaica. There are no records of Fly having in his past any sort of family connections or respectable trade. The earliest reports of him list his occupation as “prize fighter,” a remarkable fact, given the history of prize-fighting at the time.

Simply put, fighters of the time used no safety equipment, and there were no rules. Biting was common (many men lost ears or noses.) Eye gouging was acceptable, and scooping an opponent’s eye from its socket was an art form. It was perfectly legal to punch or even kick below the waist, grapple, and stomp on a downed opponent. Only the very tough and/or the very desperate took up this kind of thing as a profession.

It’s safe to say, William Fly came from a poor family.

Fly, however, was not maimed, and quit the game to become a sailor. Once again, we don’t know how long he worked at this profession before he came to the attention of the authorities. We do know that he was rated as bosun, a responsible supervisory position, when he shipped out with Captain James (John) Green of board the Elizabeth in 1726.

Contemporary accounts say that Fly wanted to make a fortune, and that he had become a fighter to win one. These same accounts say that Fly turned to piracy as a get-rich-quick scheme, and hint that this was the only reason he took up work as a sailor.

But the fact that he was rated as bosun indicates that this was not the case. While ship’s captains sometimes held their positions due to family connections or financial investment in the ship, men with “blue collar” positions such as bosun need to be skilled at their jobs in order to make the ship work. A bosun scheduled work crews, and maintained the deck, ropework, and sails of the ship. Since a ship of the day contained literally miles of rope, each piece with a distinctive name and function, and had a wide variety of sails that needed to be constantly raised, lowered and adjusted due to wind and weather, this was not a job that could be mastered in only a few months.

Contemporary accounts also claim that Fly became a pirate because he was too “lazy” to work as a regular sailor. However, these accounts do not explain how, if this was the case, Fly persuaded the entire crew of the Elizabeth to mutiny.

I believe that it is significant that the captain, Green, was lying drunk in his bed when the mutineers woke him and dragged him on deck. They seem to have been in a rage, though the cause of this has never been explained. Certainly some merchant captains abused their men terribly. Whatever drove Fly and the Elizabeth’s crew to mutiny, they lost no time in throwing Green and his first mate, Thomas Jenkins, into the sea.

This in itself was an unusually violent act. During other mutinies from the period, captains were put off in the ship’s boat, or left on a deserted coast. In fact, during at least one mutiny, the mutineers merely took the ship back to port and got off, and went looking for other work..

So Fly and his men were enraged. After drowning their former captain and first mate (neither of whom went down easily, and both of whom had to be beaten off the side of the ship with weapons) they made a big batch of alcoholic punch, and drank it while deciding what to do next.

The men elected Fly, the logical next in command, to the title of captain, and decided to become pirates. They created a Jolly Roger flag, renamed the ship Fame’s Revenge and began robbing ships between South Carolina and Boston.

By this time, however, the authorities were in full pursuit of pirates. William Fly and the Fame’s Revenge lasted in their career only three months before they were captured and brought to trial in Boston.

It was here that Fly showed his metal as a pirate.

While held in prison, he was visited by none other than Cotton Mather, the famous puritan preacher, notorious for his prosecution of witches during the Salem Witch trials. Mather tried in vain to persuade Fly to recant his sins, to confess, or even to attend church services during his confinement in order to be spared the fires of hell.

Cotton Mather Fly replied that he hated the church almost as much as he hated the current social structure, and that he would go to his death as a brave fellow. On the day of his hanging, Fly leaped willing into the cart that would carry him to the scaffold in the town square, and bantered with the spectators along the way.

Cotton Mather Fly replied that he hated the church almost as much as he hated the current social structure, and that he would go to his death as a brave fellow. On the day of his hanging, Fly leaped willing into the cart that would carry him to the scaffold in the town square, and bantered with the spectators along the way.Once on the scaffold, Fly took one look at the hangman’s noose awaiting him, berated the hangman for doing a sloppy job, re-tied the knot himself, and placed it around his own neck. He then berated the crowd.

Fly stated, in short, that selfish owners and brutal captains brought piracy down upon themselves, and that if seamen were paid on time, and treated like human beings, piracy would not exist. He is quoted as concluding: "Our Captain and his Mate used us Barbarously. We poor Men can’t have Justice done us. There is nothing said to our Commanders, let them never so much abuse us, and use us like Dogs."

William Fly and two of his fellow pirates were hanged on July 142 1726. A true pirate to the last, Fly urged all working class folks to stand up for themselves. May his legacy live on.

Published on December 28, 2015 20:50

December 21, 2015

Guided by a Star

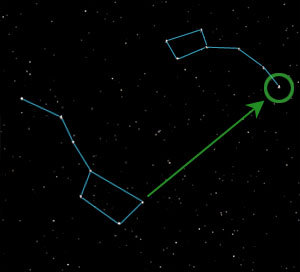

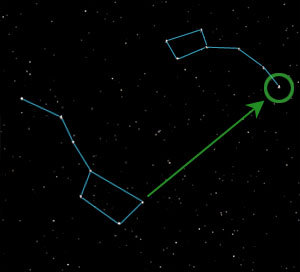

Celestial Navigation in the Golden Age of Piracy The Northern Hemisphere of the planet Earth has a very special star. Polaris, also known as the North Star, sits almost exactly over the axis point of Earth’s rotation. Anyone, looking into a clear night sky, can determine the direction North – no matter what the season, no matter what the time of night.

One ancient name for Polaris was Cynosūra, from the Greek word meaning "the dog’s tail" (reflecting a time when the constellation of Ursa Minor "Little Bear" was taken to represent a dog), hence the English word cynosure. Most other names are directly tied to its role as pole star.

In English, it was known as "pole star" or "north star"; in Spenser, also "steadfast star".

An older English name, attested since the 14th century, is lodestar "guiding star", similar in meaning to the old German and Old Norse names.

The name Polaris in English goes back to the 17th century (just before the pirates; time). It is a contraction for the Latin stella polaris "pole star". Another Latin name is stella maris "sea-star" denoting its importance to sailors. Stella Maris was also used as a title of the Blessed Virgin Mary, popularized in the hymn Ave Maris Stella –from the 8th century.

Navigation by the stars – celestial navigation – is believed to have started in the trackless wilderness of Earth’s deserts, and was almost immediately adopted by fledgling mariners.

The sea is a treacherous place to travel. Not only are there no landmarks (land-marks) but the water is constantly moving – often not going the direction that a sailor wants to go. Sailing against a strong current could – and in the early days of sail, actually did – mean a ship was actually traveling backwards. Add to this that the wind rarely blew in the direction a ship needed in order to sail, and it’s easy to see why navigation was a tricky matter at best.

Without instruments, it’s possible to figure an approximate location at sea by using ded reckoning. This was done with a peg-board, marking the approximate forward motion, the amount of drift, and the direction of travel, including changes of direction made during the day.

This method allowed an approximate location to be determined. But it was a matter of instinct as much as intelligence. Many of the calculations involved in ded reckoning were felt as much as known.

Celestial navigation involved MATH, and it involved instruments. During the Golden Age of Piracy, only latitude (the distance from the North Pole, shown on globes as a series of rings, the most recognizable of which is the Equator) could be accurately determined at sea. In order to find a given point, such as an island, the navigator tried to put the ship on track along a given longitude, then “run down the line” until the desired location was achieved.

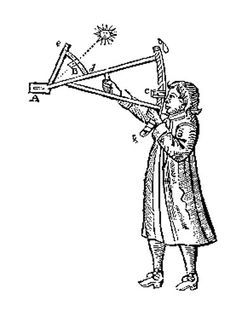

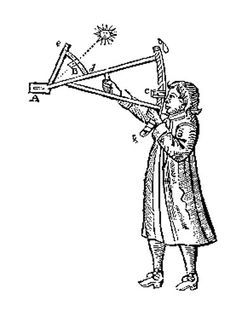

During the Golden Age, the most advanced instrument in common use was the Davis Quadrant. The device used to measure – in degrees – the distance from the horizon of a celestial body. If, for instance, Polaris is ten degrees from the horizon, he is about ten degrees north of the equator.

The method requires that a couple of conditions be met. For one thing, it requires a clear view of both the North Star and the horizon. It also requires that the navigator be somewhere north of the equator. On the southern side of the equator, Polaris is not visible, and there is no southern pole star.

The other method of celestial navigation uses the sun. If the exact position of the sun is calculated, relevant to the horizon, at exactly noon, the angle by which the sun’s position deviates from 90 degrees can be used to reveal the latitude. Using the right equipment, it’s a slightly more accurate measurement – and accuracy is important, especially when you’re all alone on the deep blue sea, looking for land.

Eventually, the invention of the sextant made latitude calculation even more exact. Longitude can be measured in the same way. If one can accurately measure the angle to Polaris, a similar measurement to a star near the eastern or western horizons will provide the longitude. The problem is that the Earth turns 15 degrees per hour, so these measurements depend on time. A measure a few minutes before or after the same measure the day before creates serious navigation errors. The invention of the modern chronometer by John Harrison in 1761 vastly simplified longitudinal calculation.

Of course, modern navigation relies not on the stars, but on GPS positioning. Satellites in geo-stable orbits over the earth’s surface send signals that can be used to determine the exact position of a ship at sea or a car whose driver wants to find the nearest Burger King. Technology has enabled navigation so precise that for a time, celestial navigation was no longer taught by the US Navy.

But navigation by the stars is making a come-back. The computers may break down, the satellites may even be shot down, but the stars will always be with us. The stars can be our guides until the end of time.

Heaven Bless all my readers, Happy Winter Solstice, and a Merry Christmas.

One ancient name for Polaris was Cynosūra, from the Greek word meaning "the dog’s tail" (reflecting a time when the constellation of Ursa Minor "Little Bear" was taken to represent a dog), hence the English word cynosure. Most other names are directly tied to its role as pole star.

In English, it was known as "pole star" or "north star"; in Spenser, also "steadfast star".

An older English name, attested since the 14th century, is lodestar "guiding star", similar in meaning to the old German and Old Norse names.

The name Polaris in English goes back to the 17th century (just before the pirates; time). It is a contraction for the Latin stella polaris "pole star". Another Latin name is stella maris "sea-star" denoting its importance to sailors. Stella Maris was also used as a title of the Blessed Virgin Mary, popularized in the hymn Ave Maris Stella –from the 8th century.

Navigation by the stars – celestial navigation – is believed to have started in the trackless wilderness of Earth’s deserts, and was almost immediately adopted by fledgling mariners.

The sea is a treacherous place to travel. Not only are there no landmarks (land-marks) but the water is constantly moving – often not going the direction that a sailor wants to go. Sailing against a strong current could – and in the early days of sail, actually did – mean a ship was actually traveling backwards. Add to this that the wind rarely blew in the direction a ship needed in order to sail, and it’s easy to see why navigation was a tricky matter at best.

Without instruments, it’s possible to figure an approximate location at sea by using ded reckoning. This was done with a peg-board, marking the approximate forward motion, the amount of drift, and the direction of travel, including changes of direction made during the day.

This method allowed an approximate location to be determined. But it was a matter of instinct as much as intelligence. Many of the calculations involved in ded reckoning were felt as much as known.

Celestial navigation involved MATH, and it involved instruments. During the Golden Age of Piracy, only latitude (the distance from the North Pole, shown on globes as a series of rings, the most recognizable of which is the Equator) could be accurately determined at sea. In order to find a given point, such as an island, the navigator tried to put the ship on track along a given longitude, then “run down the line” until the desired location was achieved.

During the Golden Age, the most advanced instrument in common use was the Davis Quadrant. The device used to measure – in degrees – the distance from the horizon of a celestial body. If, for instance, Polaris is ten degrees from the horizon, he is about ten degrees north of the equator.

The method requires that a couple of conditions be met. For one thing, it requires a clear view of both the North Star and the horizon. It also requires that the navigator be somewhere north of the equator. On the southern side of the equator, Polaris is not visible, and there is no southern pole star.

The other method of celestial navigation uses the sun. If the exact position of the sun is calculated, relevant to the horizon, at exactly noon, the angle by which the sun’s position deviates from 90 degrees can be used to reveal the latitude. Using the right equipment, it’s a slightly more accurate measurement – and accuracy is important, especially when you’re all alone on the deep blue sea, looking for land.

Eventually, the invention of the sextant made latitude calculation even more exact. Longitude can be measured in the same way. If one can accurately measure the angle to Polaris, a similar measurement to a star near the eastern or western horizons will provide the longitude. The problem is that the Earth turns 15 degrees per hour, so these measurements depend on time. A measure a few minutes before or after the same measure the day before creates serious navigation errors. The invention of the modern chronometer by John Harrison in 1761 vastly simplified longitudinal calculation.

Of course, modern navigation relies not on the stars, but on GPS positioning. Satellites in geo-stable orbits over the earth’s surface send signals that can be used to determine the exact position of a ship at sea or a car whose driver wants to find the nearest Burger King. Technology has enabled navigation so precise that for a time, celestial navigation was no longer taught by the US Navy.

But navigation by the stars is making a come-back. The computers may break down, the satellites may even be shot down, but the stars will always be with us. The stars can be our guides until the end of time.

Heaven Bless all my readers, Happy Winter Solstice, and a Merry Christmas.

Published on December 21, 2015 21:03

December 14, 2015

What to Get Your Favorite Pirate for Christmas

Christmas presents are a tough call for many of us. What to get for a sister who makes twice what you do, and vacations in Acapulco? Or for Mom, who’s in the process of downsizing the house? Or Dad, who claims that all he wants is “A little peace and quiet”?

If you have pirates on your list, it can be even harder. What might your pirate-loving friend want for Christmas?

Pirate fans usually got that way by watching movies or reading books. There are no new movies about Golden-Age pirates this year, but a good pirate read is a great way to spend those cold, dreary months waiting for pirate festivals to start again.

[image error]

The Pirate Empire seriesby TS Rhodes is something new for a lot of pirates. A set of well-researched novellas featuring a kick-ass female captain. Scarlet MacGrath only wants three things out of life – A decent meal, a glass of rum, and a good man waiting for her in the next port. Too bad life never works out so simply. In book one, Gentlemen and Fortune, Scarlet fights off the bloody-handed Red Ned Doyle, goes on a secret mission for pirate king Henry Avery, fights the Royal Navy and gets dragged into a effort to free a boatload of slaves.

Book two, Bloody Seas, finds her in desperate straits, battling wayward merchants, cannibals, and Captain Robert Davenport of the Royal Navy as she and her crew try desperately to stay alive in the unforgiving world of Golden Age piracy.

[image error]

In Book Three, Storm Season Scarlet and her crew land on the island of Nassau, home of the pirate empire. Here she meets old friends, and makes new enemies before setting out on a perilous journey to Port Royal, center of British law, and home port to the intriguing Captain Davenport.

These first three books of The Pirate Empire series are available now, with more coming out in 2016. Available in paperback or in a Kindle edition. [image error] But if your favorite pirate is more involved in drinking than reading, why not spring for a pewter or stainless steal tankard? Gifts like this are available from many sources, including online shops like Amazon. A tankard with a solid bottom can hold both hot and cold liquids, while glass or plastic-bottomed examples can be had for as little as $10.

But if your favorite pirate is more involved in drinking than reading, why not spring for a pewter or stainless steal tankard? Gifts like this are available from many sources, including online shops like Amazon. A tankard with a solid bottom can hold both hot and cold liquids, while glass or plastic-bottomed examples can be had for as little as $10.

Kraken rum is a good choice. It's tasty, and the bottle comes with an embossed sea-monster. I’m also fond of Pyrat brand rum (made by Patron). Not only is Pyrat an excellent rum, but the bottle has been molded with a shape similar to an old onion-bottle of the 18th century, and with glass that contains bubbles, much like hand-blown glass from the time.

Kraken rum is a good choice. It's tasty, and the bottle comes with an embossed sea-monster. I’m also fond of Pyrat brand rum (made by Patron). Not only is Pyrat an excellent rum, but the bottle has been molded with a shape similar to an old onion-bottle of the 18th century, and with glass that contains bubbles, much like hand-blown glass from the time.

Of course, if you want to go authentic, historic bottles are available through antique dealers or Ebay. But beware! An authentic bottle from the sunken city of Port Royal can be had, but be prepared to pay upwards of $600!

Historic coins can also be had (for a price!) through coin dealers such as Admiral Nelson Shipwreck Coins. I’m the proud owner of a few “pirate pennies” but authentic solid gold doubloons are available. Prices vary, but if you don’t want to sink thousands, Amazon also offers cast metal replicas for prices under $20

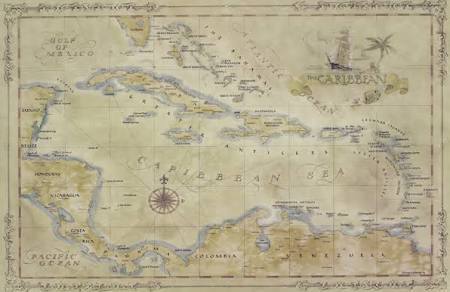

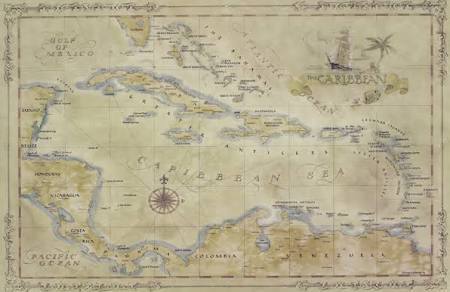

Your friend might also enjoy an antiqued map of the Caribbean. Many versions are for sale, but keep an eye out for authenticity. An accurate map with an antique feel seems to me a far better choice than a fantasy with “Pirates of the Caribbean” stamped on it. But you know your friend.

Of course, nowadays almost anything can be pirate themed. A quick trip through Google, revealed pirate themed chef’s aprons, shower curtains, bedspreads and cell phone covers. But beware! Your pirate friend may not be into whatever it is you’ve chosen. Know your subject, and use caution before shelling out your hard-earned cash for some odd object just because it has a skull-and-crossbones on it.

That said, there are a few really fun object that I, at least, wouldn’t mind receiving for the holidays.

I-clipmagnetic bookmarks with skull and crossbones. The things really work, and look like nothing else. I use them to mark pages that I return to over and over.

Pirate bottle opener. This little guy is everywhere, but he’s cute, and who doesn’t need another corkscrew?

A modern replica of an 18th century liquor bottle. Various versions of this are available. I’m pretty sure that this version was used on the set of the Starz series Black Sails. It would be especially thoughtful if you concocted one of the rum drinks from my post Authentic Pirate Rum Drinks to fill this beauty.

Last, it’s hard to go wrong if you buy your friend a pirate T-shirt. I’m especially fond of the ones that look like a pirate costume, though endless choices abound. Just make sure the size in right. After all, those of us who dream of pirate go through our pirate shirts pretty quickly.

And one more note: If you'd like to give a gift to your favorite author, review their book! Book reviews help drive sales. and nothing says love like a thoughtful review that proves you've enjoyued their work.

So dream of pirates this Christmas, and have a wonderful time. Yo Ho Ho Ho and a happy holiday to all!

If you have pirates on your list, it can be even harder. What might your pirate-loving friend want for Christmas?

Pirate fans usually got that way by watching movies or reading books. There are no new movies about Golden-Age pirates this year, but a good pirate read is a great way to spend those cold, dreary months waiting for pirate festivals to start again.

[image error]

The Pirate Empire seriesby TS Rhodes is something new for a lot of pirates. A set of well-researched novellas featuring a kick-ass female captain. Scarlet MacGrath only wants three things out of life – A decent meal, a glass of rum, and a good man waiting for her in the next port. Too bad life never works out so simply. In book one, Gentlemen and Fortune, Scarlet fights off the bloody-handed Red Ned Doyle, goes on a secret mission for pirate king Henry Avery, fights the Royal Navy and gets dragged into a effort to free a boatload of slaves.

Book two, Bloody Seas, finds her in desperate straits, battling wayward merchants, cannibals, and Captain Robert Davenport of the Royal Navy as she and her crew try desperately to stay alive in the unforgiving world of Golden Age piracy.

[image error]

In Book Three, Storm Season Scarlet and her crew land on the island of Nassau, home of the pirate empire. Here she meets old friends, and makes new enemies before setting out on a perilous journey to Port Royal, center of British law, and home port to the intriguing Captain Davenport.

These first three books of The Pirate Empire series are available now, with more coming out in 2016. Available in paperback or in a Kindle edition. [image error]

But if your favorite pirate is more involved in drinking than reading, why not spring for a pewter or stainless steal tankard? Gifts like this are available from many sources, including online shops like Amazon. A tankard with a solid bottom can hold both hot and cold liquids, while glass or plastic-bottomed examples can be had for as little as $10.

But if your favorite pirate is more involved in drinking than reading, why not spring for a pewter or stainless steal tankard? Gifts like this are available from many sources, including online shops like Amazon. A tankard with a solid bottom can hold both hot and cold liquids, while glass or plastic-bottomed examples can be had for as little as $10. Kraken rum is a good choice. It's tasty, and the bottle comes with an embossed sea-monster. I’m also fond of Pyrat brand rum (made by Patron). Not only is Pyrat an excellent rum, but the bottle has been molded with a shape similar to an old onion-bottle of the 18th century, and with glass that contains bubbles, much like hand-blown glass from the time.

Kraken rum is a good choice. It's tasty, and the bottle comes with an embossed sea-monster. I’m also fond of Pyrat brand rum (made by Patron). Not only is Pyrat an excellent rum, but the bottle has been molded with a shape similar to an old onion-bottle of the 18th century, and with glass that contains bubbles, much like hand-blown glass from the time.Of course, if you want to go authentic, historic bottles are available through antique dealers or Ebay. But beware! An authentic bottle from the sunken city of Port Royal can be had, but be prepared to pay upwards of $600!

Historic coins can also be had (for a price!) through coin dealers such as Admiral Nelson Shipwreck Coins. I’m the proud owner of a few “pirate pennies” but authentic solid gold doubloons are available. Prices vary, but if you don’t want to sink thousands, Amazon also offers cast metal replicas for prices under $20

Your friend might also enjoy an antiqued map of the Caribbean. Many versions are for sale, but keep an eye out for authenticity. An accurate map with an antique feel seems to me a far better choice than a fantasy with “Pirates of the Caribbean” stamped on it. But you know your friend.

Of course, nowadays almost anything can be pirate themed. A quick trip through Google, revealed pirate themed chef’s aprons, shower curtains, bedspreads and cell phone covers. But beware! Your pirate friend may not be into whatever it is you’ve chosen. Know your subject, and use caution before shelling out your hard-earned cash for some odd object just because it has a skull-and-crossbones on it.

That said, there are a few really fun object that I, at least, wouldn’t mind receiving for the holidays.

I-clipmagnetic bookmarks with skull and crossbones. The things really work, and look like nothing else. I use them to mark pages that I return to over and over.

Pirate bottle opener. This little guy is everywhere, but he’s cute, and who doesn’t need another corkscrew?

A modern replica of an 18th century liquor bottle. Various versions of this are available. I’m pretty sure that this version was used on the set of the Starz series Black Sails. It would be especially thoughtful if you concocted one of the rum drinks from my post Authentic Pirate Rum Drinks to fill this beauty.

Last, it’s hard to go wrong if you buy your friend a pirate T-shirt. I’m especially fond of the ones that look like a pirate costume, though endless choices abound. Just make sure the size in right. After all, those of us who dream of pirate go through our pirate shirts pretty quickly.

And one more note: If you'd like to give a gift to your favorite author, review their book! Book reviews help drive sales. and nothing says love like a thoughtful review that proves you've enjoyued their work.

So dream of pirates this Christmas, and have a wonderful time. Yo Ho Ho Ho and a happy holiday to all!

Published on December 14, 2015 20:18

December 7, 2015

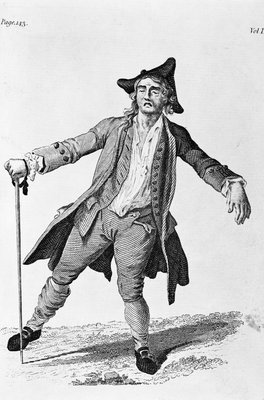

A Pirate’s Toothy Smile

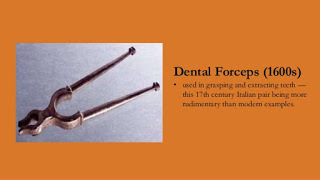

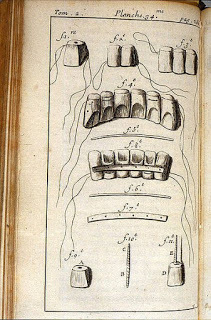

Dentistry in the 18thcentury. One of the things I didn’t especially like about Pirates of the Caribbean was the teeth. This may sound a little odd, but I’ve known for a while that the way teeth are shown in the movie are pretty much backward. Jack and company have horrible teeth, brown and marked with many crude metal fillings, While Elizabeth and her father sport healthy white smiles. This isn’t quite the way it fell out during the Golden Age of Piracy.

While tooth decay goes back as far as humanity, sugar has been the worst culprit when creating dental problems for humanity. And during the Golden Age, sugar was primarily a food for the rich.

Working class folks, pirates included, ate meat, bread, and vegetables, usually boiled. Luxuries involved butter and cream, fruit, and roasted foul.

“Gentlefolk” like Elizabeth and her father would have enjoyed cakes, custards, and “comfits” – small seeds or bits of fruit dipped into sugar syrup and dried. Flowers such as violets and rose petals were also dipped in sugar and eaten. Chocolate was not on the menu, except as a rather bitter drink, but tea and coffee might contain sugar.

This was a new phenomenon. Honey, the sweetener of choice before sugar became available, does not have the tooth- decaying properties of sugar. Honey, in fact, contains natural antibiotics which can actually protect teeth from decay. It was the white sugar from New World plantations that brought rampant tooth decay into the lives of Europeans.

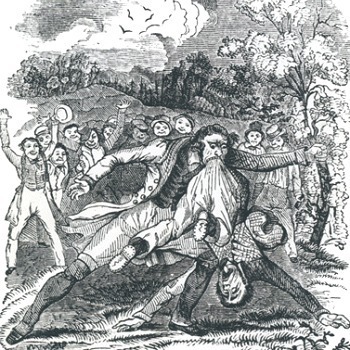

Notice the teeth

Notice the teethOf course, pirates had their own dental issues. Excessive alcohol consumption is not good for the teeth, and smoking can also cause problems. But these attack the gums more than the teeth, loosening teeth and causing direct tooth loss. Scurvy, that most nautical of diseases (actually a deficiency in vitamin C) also caused direct tooth loss.

It wasn’t unusual for a working-class person to be missing a noticeable number of teeth by the time they were in their thirties. And women often loss “a tooth for every child” as the saying went. Developing fetuses leached calcium from a woman’s bones and teeth, often leading to dental problems.

But it was the rich who sported truly terrible teeth.

Of course, they also had the best access to dental care, such as it was. This usually meant attempts to removed decay, plug holes in teeth and remove painful teeth. There was no such thing as toothpaste, and even the toothbrush was over a hundred years away.

So what was dental care like?

Dental drills existed, but they were hand drills, little more than pointed bits of metal with a handle, used to scrape decay out of rotting teeth. All of this was done without anesthesia, of course.

Once a cavity was cleaned out, attempts might be made to plug it with soft metals such as tin, gold or silver. These wore badly, of course, and often didn’t stay in the tooth. Other substances used in an effort to plug holes in teeth included resin, wax, and even stone chips. None of it worked very well.

Sophisticated “dental surgeons” might also treat holes in teeth via chemicals. Henbane, an herb, soaked in heated vinegar, might be poured into the hole. This was problematic, since the herb is poisonous, and could cause hallucinations or even death. But it was probably safer than powdered mercury, which some practitioners suggested dropping into the hole at least 3 times a day. Mercury is extremely poisonous, so doctors recommended spitting it out after it had done its work.

Medical science, such as it was, labored under a rather jarring misconception. They believed that cavities were caused by worms burrowing into the tooth, and their goal was to kill the worm. Steps taken to do this often killed the tooth as well. This ended the sufferer’s pain, however.

Medical science, such as it was, labored under a rather jarring misconception. They believed that cavities were caused by worms burrowing into the tooth, and their goal was to kill the worm. Steps taken to do this often killed the tooth as well. This ended the sufferer’s pain, however.Most dental work meat pulling teeth. Many cities had a tooth-puller, a man who went in with “crooked pliers” to grab a tooth an pull it out – no painkillers. If no professional tooth-puller was available, a barber or even a blacksmith might be persuaded to give dental care a shot. Barbers worked regularly as low-cost surgeons, due mostly to their skill with sharp tools. Blacksmiths had a variety of tongs available, and also had impressive upper-body strength, useful in puling molars.

The rich could also afford to have teeth replaced. Replacement teeth might be made of ivory, wood or even the teeth or poor people, purchased for the purpose. These teeth might be formed into dentures, or if they replaced only a few missing teeth, tied into the mouth with silk thread or wired in with gold wire.

Of course, prevention is better than cure. Though mouthwash wouldn’t exist for a long, long time, people did try to take care of their teeth. They chewed tree bark as a preventative measure, rinsed their mouths with vinegar, and scrubbed their teeth with salt, or mixtures of herbs crushed into a piece of line cloth and then rubbed on the gums. Parsley was also eaten as a method of cleaning the teeth (part of the reason parsley is used as a garnish). People also cleaned their teeth with honey, which, used as a sweetener, might have solved a lot of the problem in the first place.

Published on December 07, 2015 12:37

November 30, 2015

Sexy Pirate Babes

A NSFW Look at Pirate Pin-Ups

Female pirates are sexy. It’s a fact, independent of the fact that the number of documented female pirates is tiny, or that the ones who are documented rarely have sexy stories. The concept of a female pirate flames the male imagination. It always has, back to the origins of the Golden Age of Piracy itself. We have proof.

The proof comes in the form of Johnson’s book The Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, first published in 1724. The book was popular at the time, but had only a normal print history. Eventually it fell out of print, and the rights to the book were published by a Dutch company.

These printers made one change in the book. They replaced a historically accurate picture of Anne Bonny and Mary Read (in which the two were wearing men’s clothes, and were fully covered, as per the testimony of witnesses who had actually seen them) with a much more lurid illustration of the two virtually naked from the waist up. This put the book back on the best-sellers list, and it remains in print to this day.

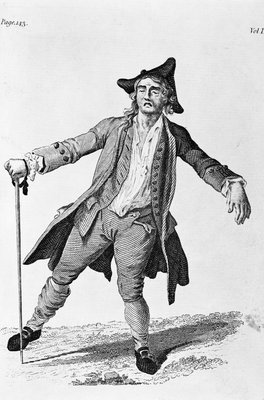

Even the Victorian, best remembered as buttoned-up prudes, loved them some female pirates. The illustrations of Victorian lady pirates look staid to us – but to folks who found the sight of a female ankle inflammatory, they were wild in the extreme.

Interestingly enough, we already see the two predominate image of the female pirate – the pirate wench and the full-fledged female pirate captain.

The pirate wench is AVAILABLE. She’s the saucy chick who gets drunk with you, parties really hard, and wouldn’t mind going all the way on a bar-side table. Pirate wenches in art often wear some version of female clothing, often a short skirt or flowing blouse. A corset is almost required, although some illustrations include only enough clothing to indicate the woman in question is a pirate.

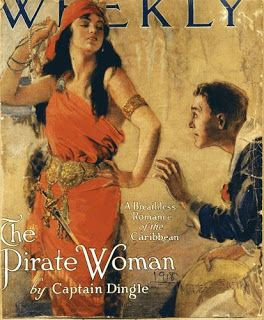

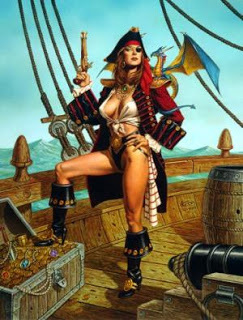

Pirate captains play to a different male fantasy. A female captain is in control and the man who meets her is at her mercy. It doesn’t matter at all that historic pirate captains didn’t have this kind of authority. Illustrations of hot pirate captains are about the fantasy.

Female pirate captains may be scantily dressed, but they always show their confidence and power. They are often shown as heavily armed, and often carry whips. Sometimes the imaged of the violent female captain can run out of control, as in this pulp-era book cover.

Pirate captains may wear corsets, but often show a bare midriff instead. Interestingly enough, they often also sport gloves. Why? I’m not sure, but perhaps it means nothing more than that men find gloves sexy.

Women often also identify with the female pirate captain. They often imagine themselves as this fearless leader, doing as they like without regard to law or propriety. Another attractive feature about the sexy female pirate – she’s often of luxurious proportions.

While skinny girls and waif types are sometimes seen, it’s much more common for a pirate to be all woman in the truest sense of the word.

In fact, the hallmark of the sexy female pirate is strength. And while, like any fantasy image, pictures of female pirates can be labeled as “objectifying” or “setting impossible standards” they also speak to independence, physical strength and daring-do.

Not bad for a pin-up!

Female pirates are sexy. It’s a fact, independent of the fact that the number of documented female pirates is tiny, or that the ones who are documented rarely have sexy stories. The concept of a female pirate flames the male imagination. It always has, back to the origins of the Golden Age of Piracy itself. We have proof.

The proof comes in the form of Johnson’s book The Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, first published in 1724. The book was popular at the time, but had only a normal print history. Eventually it fell out of print, and the rights to the book were published by a Dutch company.

These printers made one change in the book. They replaced a historically accurate picture of Anne Bonny and Mary Read (in which the two were wearing men’s clothes, and were fully covered, as per the testimony of witnesses who had actually seen them) with a much more lurid illustration of the two virtually naked from the waist up. This put the book back on the best-sellers list, and it remains in print to this day.

Even the Victorian, best remembered as buttoned-up prudes, loved them some female pirates. The illustrations of Victorian lady pirates look staid to us – but to folks who found the sight of a female ankle inflammatory, they were wild in the extreme.

Interestingly enough, we already see the two predominate image of the female pirate – the pirate wench and the full-fledged female pirate captain.

The pirate wench is AVAILABLE. She’s the saucy chick who gets drunk with you, parties really hard, and wouldn’t mind going all the way on a bar-side table. Pirate wenches in art often wear some version of female clothing, often a short skirt or flowing blouse. A corset is almost required, although some illustrations include only enough clothing to indicate the woman in question is a pirate.

Pirate captains play to a different male fantasy. A female captain is in control and the man who meets her is at her mercy. It doesn’t matter at all that historic pirate captains didn’t have this kind of authority. Illustrations of hot pirate captains are about the fantasy.

Female pirate captains may be scantily dressed, but they always show their confidence and power. They are often shown as heavily armed, and often carry whips. Sometimes the imaged of the violent female captain can run out of control, as in this pulp-era book cover.

Pirate captains may wear corsets, but often show a bare midriff instead. Interestingly enough, they often also sport gloves. Why? I’m not sure, but perhaps it means nothing more than that men find gloves sexy.

Women often also identify with the female pirate captain. They often imagine themselves as this fearless leader, doing as they like without regard to law or propriety. Another attractive feature about the sexy female pirate – she’s often of luxurious proportions.

While skinny girls and waif types are sometimes seen, it’s much more common for a pirate to be all woman in the truest sense of the word.

In fact, the hallmark of the sexy female pirate is strength. And while, like any fantasy image, pictures of female pirates can be labeled as “objectifying” or “setting impossible standards” they also speak to independence, physical strength and daring-do.

Not bad for a pin-up!

Published on November 30, 2015 20:08

November 23, 2015

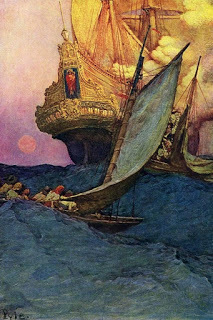

The Pirate Round

Travels of 17thand 18th Century Sea-Robbers During the early 17thcentury, piracy happened wherever no one was watching. English, French and Dutch seafarers snatched gold from the hugely prosperous Spanish Empire in the New World whenever they had the opportunity, frequently under the guise of “trading”, “self defense” or “exploration.”

But as international relations normalized – that is to say, as goodwill between nations became an important factor, and countries like England found it in their best interest to at least appear to have firm control over all their citizens, pressure began to mount for adventurous mariners to mind their manners.

The act of robbing Spanish ships and settlements had come under scrutiny from the buccaneering pirates’ own nations. It was time for a new and interesting way to harvest ill-gotten riches. And so began The Pirate Round.

“Rounders” as they were sometime called, started out in the New World, from places ranging from Nassau, to Bermuda to New York, and even including the Spanish city of Coruna. From these home ports, pirates would follow sea currents and winds to the Portuguese island of Madeira, where they would clean their ship-bottoms and re-supply.

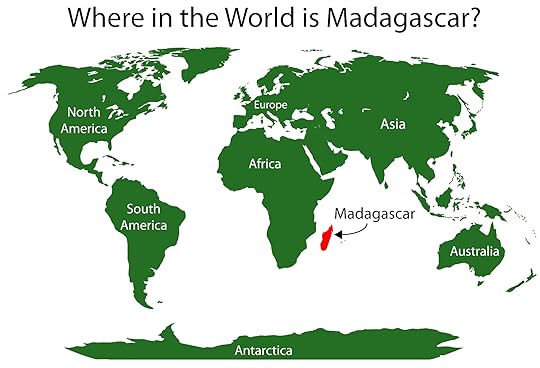

From there, these Rounders made their way around the horn of Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope (southern tip of the continent) and up the eastern coast to the Mozambique Straight, which led them to north eastern Madagascar. (Yes, that Madagascar, the one in the movie with all the talking animals.)

The island was a perfect pirate base. Claimed by no European power, it was outside of European law and the influence of European politics. A pirate named Adam Baldridge had staked out the area as early as 1687, subdued the natives (from whom he then collected tribute) and set up his most profitable venture of all, a trading company that supplied pirates with the necessities of clothing, powder and shot, and rum after their arduous journey.

His partner in this venture was Frederick Philipse, a formerly Dutch settler to New York. Philipse seems to have always been more interested in money than nationality. He had married a rich and driven widow, and when the English took over his colony, he joined with them and changed his name to better fit in with his new neighbors.

Philipse had no compunction about shady dealings. He dealt in illegal slavery, and was happy to trade with pirates as long as it brought a handsome profit. It did. The simple addition of a reliable, friendly base for re-supply brought sea-robbers and fortune hunters from all over the world.

They were hunting Eastern prey. Madagascar’s northern tip made a perfect spot from which to stake out Red Sea trading, and to waylay ships carrying Muslim travelers on their way to Mecca for the Haj, or sacred pilgrimage. Often these trading ships were richly appointed. Henry Avery took a ship valued at over £300,000 – more money than he, his ship and his crew could have realized in 20 years of honest trading. Thomas Tew made an even more enormous haul.

It was a perfect location for pirates. The Eastern ships were not used to attacks from the well-equipped, well-supplied and well-trained European pirates. Though shipping vessels were sturdy and armed with cannons, merchant vessels did not necessarily have the latest weapons, and often had not maintained their weaponry or fully trained their crews. Ship size and the appearance of great power was often enough to chase off local raiders.

Furthermore, The East was still largely outside of European relations. Eastern rulers might complain to Western nations, but complaints did not mean as much as objections from neighboring countries. It was also far easier for a European government to divest itself from the actions of men who were nowhere near European territories or colonies, and who had sailed halfway around the world to commit their crimes.

When England finally took steps to combat piracy by their citizens in the East, they followed the disastrous plan of hiring privateers to do the work. Men like Captain Kidd started out as pirate hunters, but far too many of them saw the riches to be had and quickly turned pirate themselves.

The Pirate Round flourished from about 1693 to 1697, when Baldridge left Madagascar for more civilized locations. Between 1700 and 1713, the War of Spanish Succession provided legal work as privateers for former pirates, and offered similar chances for plunder.

When the war ended in 1713, the Caribbean became the world’s greatest hotbed of piracy, as the former privateers hunted familiar waters for Spanish treasure and English merchant ships.

The Round took on a second life between 1720 and 1721, when the last pirate holdouts, men like Olivier la Busse and Bartholomew Roberts refused to accept pardons for their piratical past. These men came back to Madagascar to plunder Eastern shipping again, but were ultimately forced out by the East India Company, whose growing presence in the region demanded government protection, while its own might and power allowed it to build a private army and navy that influenced the region for nearly two centuries.

Published on November 23, 2015 08:33

November 16, 2015

What’s in the Pirate’s Chest?

Unlike common sailors, who traveled from ship to ship and kept their possessions in canvas bags, pirates were often dedicated to live on one ship for the rest of their lives (even if that wasn’t very long.) Pirates, seeking to live like “gentlemen” (we might say just to live like human beings) rose to the level of keeping enough possessions that they needed a private chest to hold them.

So, what would a pirate keep in such a chest?

Firstly, the same as any sailor, he would keep a change of clothes. Probably only one – the 18th century wasn’t big on anyone having huge amounts of clothing. Time, supplies, and the culture of the ship allowing, a sailor put on clean clothes for Sunday, and washed and repaired the other set on Monday. Then those clothes would wait until the following Sunday, when the cycle would be repeated.

Sailors also tried to keep a special set of clothes for going ashore. These were “party clothes” and were usually cleaner, in better repair, and “fancier” than common work clothes. A pirate, who had the luxury of stealing much nicer clothing from the officers and passengers on the ships he robbed, might have some very nice shore-going clothes indeed. But he probably wouldn’t have more than one set, and he would likely have only the coat and shirt. Pirates were often described as wearing grand coats along with common ragged work pants.

Perhaps they were loath to put their private parts in another man’s pants.

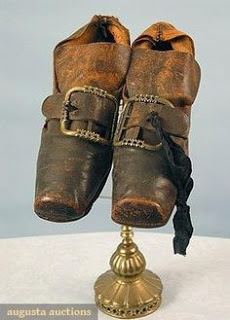

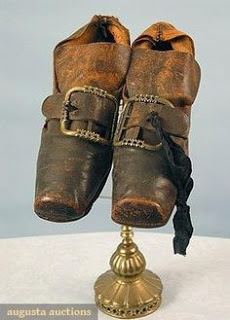

Also in the chest, part of the shore-going rig, would be shoes. Pirates usually went barefoot on the ship, and wore shoes only for special occasions, such as religious services, funerals, time on shore or attacking other ships. Boots, while worn, were very, very rare.

Now we are getting down to more individual items.

Each pirate would probably own a metal or wooden plate for eating, and a spoon. On merchant ships, the sailors were often fed out of buckets – it was quicker and easier to clean up after. Up to five men would share a bucket full of boiled beef and vegetables, which they would eat using their hands, or perhaps by scooping it up with pieces of ship’s biscuit. (This may be the origin of the word “mess.”)

Owning a pewter plate and a pewter spoon was the first mark that a pirate was going to live like a human being. Plates of this nature recovered from pirate ships often have the owner’s name crudely scratched onto the plate with a nail or other sharp object. Clearly they were important objects.

However, the pirate would not own a special knife for eating (he’d use his regular work knife) or a fork. Forks were still for royalty and the mega-rich, and a pirate probably wouldn’t see the use of them.

Of course pirates kept weapons, and the means to care for them. He might have as many as six pistols, and would certainly own a cutlass or machete. Weapons needed to be cleaned and oiled regularly, so oil and whetstones would be in the chest, in addition to spare flints, and a small supply of powder and shot.

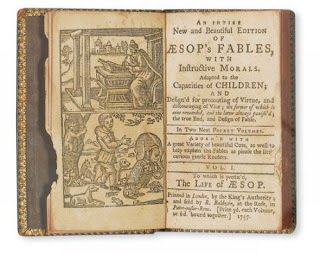

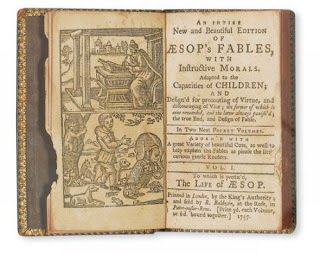

Literacy was low in the early 1700’s, but a pirate’s chest might still contain letters from home, or books. If the pirate couldn’t read, he might persuade a more literate friend to read to him, and he might be taking lessons in reading or writing in his spare time. Popular books were the Bible, editions of Shakespeare, or Aesop’s Fables, which was the closest thing to a children’s book back in the day.

Writing supplies might also be in the chest, though they weren’t common. Interestingly enough, men who could not write could often draw beautifully. Writing or drawing equipment would consist of paper, a bottle of ink, and one or more quill feathers cut into pens.

Tiny miniature portraits of loved ones were beginning to be popular. It would be very rare for a common sailor to be able to afford such a thing, but some people could.

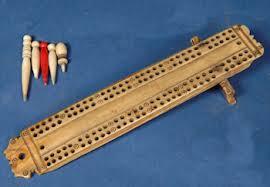

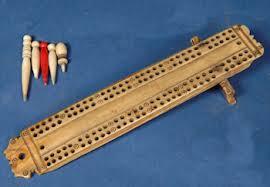

A pirate might also have gaming supplies, such as dice, cards, a backgammon or chess set, or a cribbage board. Gambling was usually not permitted on board ship (it often led to quarrels or bad feelings), but as soon as the crew hit port it was perfectly ok, and no one wanted to be without supplies. A pirate could also wile away the time by playing Patience, or what we would call Solitaire.

Most ships employed a musician, but a pirate might own and play his own musical instrument, such as a drum, a fiddle, a wooden flute or a guitar. Musical instruments weren’t much like modern ones, but pirates were well known to enjoy music.

Craft supplies would also be in the chest. Most sailors carved wood, did embroidery, knitting, or cross-stitch, or did fancy rope work for enjoyment. So, while rope wouldn’t be in the chest (that would qualify as ship’s supplies, and would be stored in a common area) he might have a ball of string, yarn, or twine.

Most British pirates smoked a pipe, so pipes and tobacco might be stored in the chest. Pipes were usually made of clay, and they broke easily. Huge piles of broken pipes are found near pirate sites. Pirates also smoked cigars, and might have some in the chest. Lighters and matches had not yet been invented. Smoking materials were lit by dipping a long splinter of wood into an existing flame (candle, lantern, or the galley stove) and carrying the flame to the pipe.

The pirate wouldn’t need to keep bottles of rum in his chest, since liquor supplies – all you cared to drink – were as much a part of shipboard life as food or water.

Sewing supplies, and other items to repair possessions would be in the chest. Pirates mended their own clothing and even shoes. Light thread, heavy thread, needles of various sizes, beeswax, oil, and other such things were in the chest.

Lastly, the pirate would have a small “purse” or carrying bag from money. Usually, they carried only a small amount. Why? Gold and silver are heavy, and so they were most often stored in some central location until needed. The ship’s Quartermaster kept a list of the treasure each pirate had earned, and a corresponding list of what he had drawn out of the fund. A quick calculation showed how much was being “held” for him. The system worked a lot like a pirate credit union.

Surprised? Even pirates knew that money doesn’t buy happiness. It’s the things that money CAN buy, however, that often bring a smile.

So, what would a pirate keep in such a chest?

Firstly, the same as any sailor, he would keep a change of clothes. Probably only one – the 18th century wasn’t big on anyone having huge amounts of clothing. Time, supplies, and the culture of the ship allowing, a sailor put on clean clothes for Sunday, and washed and repaired the other set on Monday. Then those clothes would wait until the following Sunday, when the cycle would be repeated.

Sailors also tried to keep a special set of clothes for going ashore. These were “party clothes” and were usually cleaner, in better repair, and “fancier” than common work clothes. A pirate, who had the luxury of stealing much nicer clothing from the officers and passengers on the ships he robbed, might have some very nice shore-going clothes indeed. But he probably wouldn’t have more than one set, and he would likely have only the coat and shirt. Pirates were often described as wearing grand coats along with common ragged work pants.

Perhaps they were loath to put their private parts in another man’s pants.

Also in the chest, part of the shore-going rig, would be shoes. Pirates usually went barefoot on the ship, and wore shoes only for special occasions, such as religious services, funerals, time on shore or attacking other ships. Boots, while worn, were very, very rare.

Now we are getting down to more individual items.

Each pirate would probably own a metal or wooden plate for eating, and a spoon. On merchant ships, the sailors were often fed out of buckets – it was quicker and easier to clean up after. Up to five men would share a bucket full of boiled beef and vegetables, which they would eat using their hands, or perhaps by scooping it up with pieces of ship’s biscuit. (This may be the origin of the word “mess.”)

Owning a pewter plate and a pewter spoon was the first mark that a pirate was going to live like a human being. Plates of this nature recovered from pirate ships often have the owner’s name crudely scratched onto the plate with a nail or other sharp object. Clearly they were important objects.

However, the pirate would not own a special knife for eating (he’d use his regular work knife) or a fork. Forks were still for royalty and the mega-rich, and a pirate probably wouldn’t see the use of them.

Of course pirates kept weapons, and the means to care for them. He might have as many as six pistols, and would certainly own a cutlass or machete. Weapons needed to be cleaned and oiled regularly, so oil and whetstones would be in the chest, in addition to spare flints, and a small supply of powder and shot.

Literacy was low in the early 1700’s, but a pirate’s chest might still contain letters from home, or books. If the pirate couldn’t read, he might persuade a more literate friend to read to him, and he might be taking lessons in reading or writing in his spare time. Popular books were the Bible, editions of Shakespeare, or Aesop’s Fables, which was the closest thing to a children’s book back in the day.

Writing supplies might also be in the chest, though they weren’t common. Interestingly enough, men who could not write could often draw beautifully. Writing or drawing equipment would consist of paper, a bottle of ink, and one or more quill feathers cut into pens.

Tiny miniature portraits of loved ones were beginning to be popular. It would be very rare for a common sailor to be able to afford such a thing, but some people could.

A pirate might also have gaming supplies, such as dice, cards, a backgammon or chess set, or a cribbage board. Gambling was usually not permitted on board ship (it often led to quarrels or bad feelings), but as soon as the crew hit port it was perfectly ok, and no one wanted to be without supplies. A pirate could also wile away the time by playing Patience, or what we would call Solitaire.

Most ships employed a musician, but a pirate might own and play his own musical instrument, such as a drum, a fiddle, a wooden flute or a guitar. Musical instruments weren’t much like modern ones, but pirates were well known to enjoy music.

Craft supplies would also be in the chest. Most sailors carved wood, did embroidery, knitting, or cross-stitch, or did fancy rope work for enjoyment. So, while rope wouldn’t be in the chest (that would qualify as ship’s supplies, and would be stored in a common area) he might have a ball of string, yarn, or twine.

Most British pirates smoked a pipe, so pipes and tobacco might be stored in the chest. Pipes were usually made of clay, and they broke easily. Huge piles of broken pipes are found near pirate sites. Pirates also smoked cigars, and might have some in the chest. Lighters and matches had not yet been invented. Smoking materials were lit by dipping a long splinter of wood into an existing flame (candle, lantern, or the galley stove) and carrying the flame to the pipe.

The pirate wouldn’t need to keep bottles of rum in his chest, since liquor supplies – all you cared to drink – were as much a part of shipboard life as food or water.

Sewing supplies, and other items to repair possessions would be in the chest. Pirates mended their own clothing and even shoes. Light thread, heavy thread, needles of various sizes, beeswax, oil, and other such things were in the chest.

Lastly, the pirate would have a small “purse” or carrying bag from money. Usually, they carried only a small amount. Why? Gold and silver are heavy, and so they were most often stored in some central location until needed. The ship’s Quartermaster kept a list of the treasure each pirate had earned, and a corresponding list of what he had drawn out of the fund. A quick calculation showed how much was being “held” for him. The system worked a lot like a pirate credit union.

Surprised? Even pirates knew that money doesn’t buy happiness. It’s the things that money CAN buy, however, that often bring a smile.

Published on November 16, 2015 06:36

November 9, 2015

Pirate Festival – The St Augustine Pirate Gathering

I’ve been to a few pirate festivals, but being landlocked in the middle of North America, there’s only one recurring one locally. This past weekend, I packed my pistols onto a plane (checked baggage) and headed down to Florida for the 8th annual St Augustine Pirate Gathering.

I’ve been to a few pirate festivals, but being landlocked in the middle of North America, there’s only one recurring one locally. This past weekend, I packed my pistols onto a plane (checked baggage) and headed down to Florida for the 8th annual St Augustine Pirate Gathering.Now, in the Midwest, pirate festivals are few and far between, but along the eastern seaboard there’s something happening nearly every weekend. This particular event came highly recommended, and besides, it’s in the oldest city in America, a place I wrote about here.

Air travel is certainly tiring, but it can go smoothly if you just keep your weapons out of the carry-on luggage. We met at Jacksonville airport, picked up our car (red VW Bug) and drove about 60 miles to St Augustine.

A few snags with the car meant the only event left on Friday night was the Buccaneer Bash, which was sold out. Our bad. The event featured all-you-can-drink rum, pirate rock and belly dancing. But my friend isn’t much of a drinker, and to tell the truth, neither am I. We hit the old fort instead.

The fort at St Augustine, Castillo de San Marcos, hasn’t changed much since 1695, but recent work has made it more visitor-friendly. We explored the site, talked to the park rangers and on-site reenactors, and exited through the gift shop, just like we were supposed to. A breeze was coming off the sea, and I enjoyed taking pictures during the ‘golden hour’, just before sunset.

We were up early to head to the festival the next day. Our hotel took one look at our costumes and comped us an excellent breakfast, but weather was not on our side. Not only was the temperature higher than expected, but humidity was 100%, and the Florida sun was merciless. I dressed in my coolest garb – a cotton skirt, gauze shirt, wide leather belt and accoutrements, including boots.

Kristi was cosplaying a pirate from one of my stories – a historical river-pirate named Sadie the Goat. Sadie got her nickname by head-butting her opponents in battle. She finally met her match and lost an ear to a huge Irish woman named Mag, who bit the ear off, pickled it, then gave it back to Sadie when they made up. Kristi was charmed by the story, and she wears a scarf over one of her own ears, and a human ear (plastic) on a string around her neck.