T.S. Rhodes's Blog, page 16

March 30, 2015

Pirates and the Law

We all know that pirates were law-breakers. That’s kind of a definition of the job. But what were the laws, anyway? What was the British legal system like in 1715?

The beginning of this answer is: A lot different than it is today.

British law was undergoing a rather radical change at the time, from a medieval system primarily designed to punish people who stepped outside the system, to a system designed to deter crimes against property.

The difference was the rise in what we would call the upper middle class. Unlike previous people with money, their wealth was not tied up in land, but in property such as homes, carriages, artwork and fine clothing. These people wanted to protect their possessions, and also their business dealings.

Because of this, England set out on a course of new laws designed to deter undesirable behavior. Crimes like shoplifting, robbing a house or rioting were punishable by death. The list of crimes that fell under this category grew by leaps and bounds, form about 26 during the Golden Age or Piracy to well over two hundred by the mid 1700’s.

The laws of the time are today referred to as “The Bloody Code” though they were never called this while they were in force.

The goal – to paraphrase a quote from the time – was not to punish the stealing of horses but to prevent the stealing of horses.

Today we wouldn’t understand many of the distinctions in these laws. For instance, it was legal for a nobleman to rape a common woman, on the theory that she would necessarily be so flattered at the possibility of bearing a noble child that she was not capable of resisting.

A commoner raping a noblewoman, however, was a crime against the woman’s family.

It was perfectly legal to beat a person nearly to death, so long as they were not permanently disabled or killed. But it was illegal to damage their clothing by cutting it, as this was property damage. Women were not legally allowed to own property. Counterfeiting was illegal for both men and women, but men were hanged for the crime, while women were burned alive. These are only a few examples, but you get the drift.

Similarly, the court proceedings would not be recognized by modern folks, especially Americans. The job that Americans refer to as “lawyer” was divided between a solicitor (who represented the client in court) and a barrister (who was hired by the client and researched the law).

People who were arrested did not get out on bail. They were kept in chains and locked up in prison, where they were kept pending trial. If they did not have much money, or friends outside to help them, they did not receive food or drink above the bare necessities for survival. They slept on the floor in piles of straw, and were not provided a change of clothing, or even wash water. Trial could be expected to come within a few weeks, but the accused would be filthy, bedraggled and much thinner when standing before the judge. It would be easy to convict such a person.

Nor were the accused given any information about the case or their legal rights, unless they or some friend could afford to hire legal representation. This put the poor at a severe disadvantage. But the laws were written specifically for the rich, anyway. God, it was believed, had already decided that the rich were better and more important people than the poor. That was why they were rich. God had blessed them.

Bringing a court case was more difficult for a poor person as well. The burden of proving the case was entirely on them. There were no police departments yet. Instead, men similar to private detectives could be hired – for a price – to investigate, gather evidence and bring the accused to be locked up. These men were called thief-takers. Though their fees were not prohibitive to the well-to-do, they could destroy a poor family.

Thief-takers were also very prone to corruption. Since they were paid to gather evidence, they could accuse an innocent person and be believed. This in turn could lead to blackmail, protection rackets and perjury. The system was ripe for abuse.

Even bringing a case to court was expensive. The person bringing the case needed to pay the court costs up front, and this kind of money was out of the reach of the poor. If a rich person cheated on a contract or took the property of a poor person, it would be almost impossible for the poor person to raise enough money to hire legal help, have papers served, and pay the necessary court costs. The rich were safe.

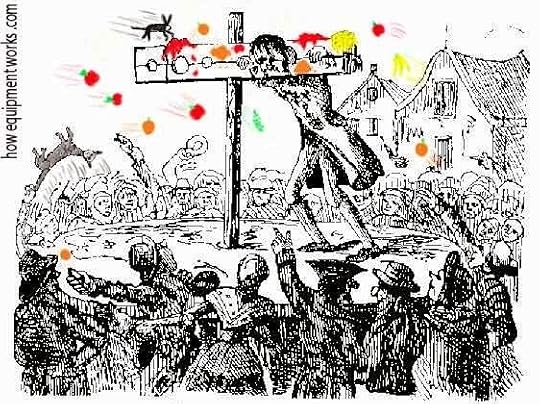

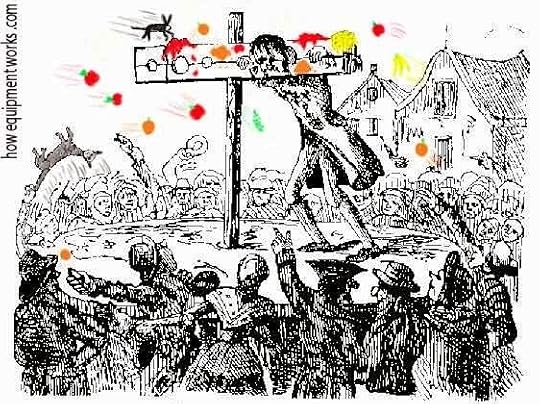

Punishments, besides hanging, were also not what modern people would expect. Instead, the system looked more like something one could imagine in a radical Islamist state. People could be burned at the stake, hanged, or skinned and cut into pieces. For less severe crimes, the punishment might be lashes with a whip, strokes with a rod, or even being tied to the back side of a cart and dragged through town while being beaten by a gang of men with various instruments. Simply being locked up was not an option.

Even “the stocks”, that cute little punishment that we today associate with the Puritans, was much more harsh than it seems. Yes, the punishment was to be confined by having the head and hands, or maybe the head hands and feet, immobilized by a wooden device. What we don’t think of was that, while confined, the person could have rocks thrown at them, or rotten fruit, or dead animals. Hot oil could be poured on them. In fact, any abuse that an angry or bored populace could dish out was okay.

Once again, the rich got off easier. Their families could afford to hire body guards for the event.

Oh, and piracy? The date when piracy became illegal is not clear, but was a death-penalty crime since long before the Golden Age. Piracy broke both the old laws (being outside the social structure) and the new ones (stealing and destroying property, and committing murder). Hanging was the penalty, but further rituals grew up around it. In England, it was traditional to hang a pirate at low tide, then bind the dead body to a pole and let 3 tides wash over it. After this, the body would either be given to a medical school for dissection or covered in tar, bound with iron bands and hung up as a warning to others.

Piracy was one of the last death penalties still on England’s law books. The death penalty for piracy, along with high treason, was reduced to life imprisonment in 1998.

The beginning of this answer is: A lot different than it is today.

British law was undergoing a rather radical change at the time, from a medieval system primarily designed to punish people who stepped outside the system, to a system designed to deter crimes against property.

The difference was the rise in what we would call the upper middle class. Unlike previous people with money, their wealth was not tied up in land, but in property such as homes, carriages, artwork and fine clothing. These people wanted to protect their possessions, and also their business dealings.

Because of this, England set out on a course of new laws designed to deter undesirable behavior. Crimes like shoplifting, robbing a house or rioting were punishable by death. The list of crimes that fell under this category grew by leaps and bounds, form about 26 during the Golden Age or Piracy to well over two hundred by the mid 1700’s.

The laws of the time are today referred to as “The Bloody Code” though they were never called this while they were in force.

The goal – to paraphrase a quote from the time – was not to punish the stealing of horses but to prevent the stealing of horses.

Today we wouldn’t understand many of the distinctions in these laws. For instance, it was legal for a nobleman to rape a common woman, on the theory that she would necessarily be so flattered at the possibility of bearing a noble child that she was not capable of resisting.

A commoner raping a noblewoman, however, was a crime against the woman’s family.

It was perfectly legal to beat a person nearly to death, so long as they were not permanently disabled or killed. But it was illegal to damage their clothing by cutting it, as this was property damage. Women were not legally allowed to own property. Counterfeiting was illegal for both men and women, but men were hanged for the crime, while women were burned alive. These are only a few examples, but you get the drift.

Similarly, the court proceedings would not be recognized by modern folks, especially Americans. The job that Americans refer to as “lawyer” was divided between a solicitor (who represented the client in court) and a barrister (who was hired by the client and researched the law).

People who were arrested did not get out on bail. They were kept in chains and locked up in prison, where they were kept pending trial. If they did not have much money, or friends outside to help them, they did not receive food or drink above the bare necessities for survival. They slept on the floor in piles of straw, and were not provided a change of clothing, or even wash water. Trial could be expected to come within a few weeks, but the accused would be filthy, bedraggled and much thinner when standing before the judge. It would be easy to convict such a person.

Nor were the accused given any information about the case or their legal rights, unless they or some friend could afford to hire legal representation. This put the poor at a severe disadvantage. But the laws were written specifically for the rich, anyway. God, it was believed, had already decided that the rich were better and more important people than the poor. That was why they were rich. God had blessed them.

Bringing a court case was more difficult for a poor person as well. The burden of proving the case was entirely on them. There were no police departments yet. Instead, men similar to private detectives could be hired – for a price – to investigate, gather evidence and bring the accused to be locked up. These men were called thief-takers. Though their fees were not prohibitive to the well-to-do, they could destroy a poor family.

Thief-takers were also very prone to corruption. Since they were paid to gather evidence, they could accuse an innocent person and be believed. This in turn could lead to blackmail, protection rackets and perjury. The system was ripe for abuse.

Even bringing a case to court was expensive. The person bringing the case needed to pay the court costs up front, and this kind of money was out of the reach of the poor. If a rich person cheated on a contract or took the property of a poor person, it would be almost impossible for the poor person to raise enough money to hire legal help, have papers served, and pay the necessary court costs. The rich were safe.

Punishments, besides hanging, were also not what modern people would expect. Instead, the system looked more like something one could imagine in a radical Islamist state. People could be burned at the stake, hanged, or skinned and cut into pieces. For less severe crimes, the punishment might be lashes with a whip, strokes with a rod, or even being tied to the back side of a cart and dragged through town while being beaten by a gang of men with various instruments. Simply being locked up was not an option.

Even “the stocks”, that cute little punishment that we today associate with the Puritans, was much more harsh than it seems. Yes, the punishment was to be confined by having the head and hands, or maybe the head hands and feet, immobilized by a wooden device. What we don’t think of was that, while confined, the person could have rocks thrown at them, or rotten fruit, or dead animals. Hot oil could be poured on them. In fact, any abuse that an angry or bored populace could dish out was okay.

Once again, the rich got off easier. Their families could afford to hire body guards for the event.

Oh, and piracy? The date when piracy became illegal is not clear, but was a death-penalty crime since long before the Golden Age. Piracy broke both the old laws (being outside the social structure) and the new ones (stealing and destroying property, and committing murder). Hanging was the penalty, but further rituals grew up around it. In England, it was traditional to hang a pirate at low tide, then bind the dead body to a pole and let 3 tides wash over it. After this, the body would either be given to a medical school for dissection or covered in tar, bound with iron bands and hung up as a warning to others.

Piracy was one of the last death penalties still on England’s law books. The death penalty for piracy, along with high treason, was reduced to life imprisonment in 1998.

Published on March 30, 2015 19:36

March 23, 2015

Pixie Pirate

Grownup pirates like us aren’t supposed to enjoy movies aimed at five year old girls, but since Black Sails isn’t on again until Saturday, and Pirates of the Caribbean Dead Men Tell No Tales isn’t due out until 2017, I found myself sitting in front of Pirate Fairy, Disney’s 2014 movie short in which Zarina, a pixie from Pixie Hollow in Neverland takes up work as a pirate.

The movie is the fifth of the straight-to-video Pixie Hollow series, and pre-supposes a certain knowledge of the Pixie Hollow universe. It’s a series aimed primarily at pre-school girls, so I didn’t expect much, especially in the pirate department.

The first movie in the series apparently fixed the most enormous problem, which was that Tinkerbell was REALLY mean. Then there’s a cast of pixie characters, all pretty much stereotypes and color-coded, in case you can’t tell them apart. The pixies seem to have their own little community in Neverland, and the series seems to pre-date the introduction of Peter Pan to the island.

The plot of this video involves Zarina, who has a pretty boring job packaging pixie dust at the pixie-dust factory. In her spare time she performs chemical experiments, trying to find out the possibility of formulating different types of dust.

Now, it may seem odd that movies about fairies are meant to encourage little girls to take up chemistry and engineering, but this is the case. “Tinker” bell likes to build things, and Zarina does a lot of things right in performing her chemical experiments. For instance, she carefully records her experiments in a book, and the thickness of the book, along with other clues, indicate that she’s been at this quite a while.

She’s also made some personal sacrifices in order to perform these experiments. She uses her personal share of pixie dust in her lab, and is therefore forced to walk everywhere, instead of flying like her friends.

What we see, of course, is her big breakthrough. She makes all kinds of dust that do all kinds of things (also color-coded). But if she continued her research and development with careful product safety and dosage testing there wouldn’t be much of a story. So she goes crazy with the new dust, does a lot of damage and gets in trouble.

Her answer to all this is to use her new products to put all the fairies to sleep and steal the dust-producing element for her own use. She then takes up with a pirate crew who offer to further her research in exchange for her giving their ship flying powers, enabling them to rob people far inland and get away with the goods.

[image error]

I wasn’t expecting much from the pirates. The entire ship’s crew consists of six guys, but I put this down to the requirements of low-budget CG, and keeping everything clear for the kids. They show a variety of nationalities, including an Asian, an Italian and an Irishman, but no African pirates, which kind of disappointed me.

The ship looks good – surprisingly good, although work on the ship was an investment – a CG good ship can have a lot of uses. It’s referred to as a “frigate” though it’s clearly a galleon. But hey, any time the word “frigate” gets used in a kids movie, I’m all for it.

The pirate fairy is, of course, the captain. She gets a headband, a sword and a pair of really cool boots to go with the title. After all, it’s aimed at little girls, so we have to include some cute clothes.

Weird little things were good. The pirate’s shoes are perfect straight-last buckle shoes. The one-eyed pirate is the cook. The cannons actually look like real cannons. The use of the term “offering you quarter” is properly defined, and almost properly used.

The other friendly fairies set out, first to rescue their friend, and once it’s clear she’s become a pirate of her own free will, to get back the dust-generator. Along the way, there are hijinks in which the fairies’ powers get changed around, and also assorted fairy-dust generated special effects. One of the fairies “imprints” a newly hatched baby crocodile.

More to my interest was the gradual revelation of the identity of one long-faced pirate. First we learn his name is James. Then that he went to school at Eaton. (There’s only one pirate who’s been to Eaton.) About the time the pirates reveal they were only joshing Zarina along until she could make the ship fly, James opens a closet and whips out a long red pirate coat and an enormous hat.

By this point most kids will have figured out who James is, but the movie never actually says it. Instead, the baby crocodile swallows an alarm clock, a pretty funny scene, as objects are being thrown at the crocodile, and I’m waiting for the alarm clock. Then James picks up a hook as a tool. Finally, at the end, after the crocodile has bitten him on the butt. James is washed out to sea, and is picked up by none other than Mr. Smee. I’m imagining the delight of a child who figures out, all on her own, who James is.

Of course the fairy dust generator is recovered and the fairies have a happy ending. We knew that would happen. I’m just thrilled with such a great little biography of the early days of Captain Hook.

The movie is the fifth of the straight-to-video Pixie Hollow series, and pre-supposes a certain knowledge of the Pixie Hollow universe. It’s a series aimed primarily at pre-school girls, so I didn’t expect much, especially in the pirate department.

The first movie in the series apparently fixed the most enormous problem, which was that Tinkerbell was REALLY mean. Then there’s a cast of pixie characters, all pretty much stereotypes and color-coded, in case you can’t tell them apart. The pixies seem to have their own little community in Neverland, and the series seems to pre-date the introduction of Peter Pan to the island.

The plot of this video involves Zarina, who has a pretty boring job packaging pixie dust at the pixie-dust factory. In her spare time she performs chemical experiments, trying to find out the possibility of formulating different types of dust.

Now, it may seem odd that movies about fairies are meant to encourage little girls to take up chemistry and engineering, but this is the case. “Tinker” bell likes to build things, and Zarina does a lot of things right in performing her chemical experiments. For instance, she carefully records her experiments in a book, and the thickness of the book, along with other clues, indicate that she’s been at this quite a while.

She’s also made some personal sacrifices in order to perform these experiments. She uses her personal share of pixie dust in her lab, and is therefore forced to walk everywhere, instead of flying like her friends.

What we see, of course, is her big breakthrough. She makes all kinds of dust that do all kinds of things (also color-coded). But if she continued her research and development with careful product safety and dosage testing there wouldn’t be much of a story. So she goes crazy with the new dust, does a lot of damage and gets in trouble.

Her answer to all this is to use her new products to put all the fairies to sleep and steal the dust-producing element for her own use. She then takes up with a pirate crew who offer to further her research in exchange for her giving their ship flying powers, enabling them to rob people far inland and get away with the goods.

[image error]

I wasn’t expecting much from the pirates. The entire ship’s crew consists of six guys, but I put this down to the requirements of low-budget CG, and keeping everything clear for the kids. They show a variety of nationalities, including an Asian, an Italian and an Irishman, but no African pirates, which kind of disappointed me.

The ship looks good – surprisingly good, although work on the ship was an investment – a CG good ship can have a lot of uses. It’s referred to as a “frigate” though it’s clearly a galleon. But hey, any time the word “frigate” gets used in a kids movie, I’m all for it.

The pirate fairy is, of course, the captain. She gets a headband, a sword and a pair of really cool boots to go with the title. After all, it’s aimed at little girls, so we have to include some cute clothes.

Weird little things were good. The pirate’s shoes are perfect straight-last buckle shoes. The one-eyed pirate is the cook. The cannons actually look like real cannons. The use of the term “offering you quarter” is properly defined, and almost properly used.

The other friendly fairies set out, first to rescue their friend, and once it’s clear she’s become a pirate of her own free will, to get back the dust-generator. Along the way, there are hijinks in which the fairies’ powers get changed around, and also assorted fairy-dust generated special effects. One of the fairies “imprints” a newly hatched baby crocodile.

More to my interest was the gradual revelation of the identity of one long-faced pirate. First we learn his name is James. Then that he went to school at Eaton. (There’s only one pirate who’s been to Eaton.) About the time the pirates reveal they were only joshing Zarina along until she could make the ship fly, James opens a closet and whips out a long red pirate coat and an enormous hat.

By this point most kids will have figured out who James is, but the movie never actually says it. Instead, the baby crocodile swallows an alarm clock, a pretty funny scene, as objects are being thrown at the crocodile, and I’m waiting for the alarm clock. Then James picks up a hook as a tool. Finally, at the end, after the crocodile has bitten him on the butt. James is washed out to sea, and is picked up by none other than Mr. Smee. I’m imagining the delight of a child who figures out, all on her own, who James is.

Of course the fairy dust generator is recovered and the fairies have a happy ending. We knew that would happen. I’m just thrilled with such a great little biography of the early days of Captain Hook.

Published on March 23, 2015 19:29

March 16, 2015

Why We Owe St Patrick's Day to Pirates

St Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, wasn’t Irish, but English. He owes his life on the Emerald isle, and ultimately his sainthood, to pirates.

Piracy and slavery had been practiced in Ireland back into pre-history. Icelandic Viking raiders attacked the island, carrying off women. (Modern DNA studies show that 60% of the maternal gene line comes from captured Celts.) In return, sea-going Irish chieftains captured slaves in the Nordic countries (giving rise to a gene strain of blond Celts), the rest of the British Isles, and even France.

Patrick, or Patricius, was the son of a well-to-do Roman living in Britain, then Britannia. He had been born some time between 390 and 400. (Yes, that’s a three-digit year number.) His parents, while nominally Christian, were not devout by any means, and Patrick was an atheist.

When he was 15, Irish pirates raided near his home, and he was captured and taken back to Ireland and sold as a slave.

For the next six years, Patrick herded sheep, lived in a stone hovel, and enjoyed no rights at all. He was, understandably, miserable. To make his life more bearable, he turned to prayer, and came to believe that it was because of his previous disbelief that God had chosen for him to become a slave. His devotion to Christianity earned him the mocking name “Holy Boy” among the other slaves.

Finally Patrick was visited with a dream. He dreamed that he should leave his master and find his way home. He walked through 185 miles of wilderness, found passage on a ship, and made it back home to his parents in Britain.

Once there, he had another dream. This time, he dreamed that the people of Ireland were calling for him to bring them Christianity. Patrick used his family’s resources to get schooling to become a priest. When this was finished, he went back to Ireland.

His task was daunting, and some say, has never really been completed. He faced a network of warring Irish kings, each controlling their own territory, often financed by piracy. The religion of Ireland was a form of Celtic paganism, presided over by Druidic priests and heavily ingrained into the culture. Though Patrick made inroads, it could not be truly said that he converted the Irish to Christianity. He merely started the process.

Patrick died in about 460, and faded into obscurity. But years later, when Christianity was more popular on the island, he was recalled as the originator of the religion. In the Irish tradition of heroes, it was expected that Patrick should have some adventures or accomplishments.

The story of chasing the snakes out of Ireland is a metaphor for overcoming paganism, since the snake was a symbol of re-birth for pagans. Followers also invented epic magic battles between Patrick and the Druids. Even the date of Patrick’s death, March 17th, was nothing more than a guess.

For centuries, St Patrick’s Day was merely a church holiday, and was not celebrated any differently than any other saint’s day. But Irish immigrants to America, missing their homeland, began to celebrate more and more extravagantly. Parades, dances and parties were not in Patrick’s style, as he was a quiet man, much more given to quiet contemplation and prayer.

In fact, Patrick would probably be horrified by all the drunkenness that now accompanies the supposed anniversary of his death.

So, if you don’t want to drink to St. Patrick, drink to the pirates who captured him. Without them Ireland wouldn’t have its patron saint, and we wouldn’t have green beer.

Piracy and slavery had been practiced in Ireland back into pre-history. Icelandic Viking raiders attacked the island, carrying off women. (Modern DNA studies show that 60% of the maternal gene line comes from captured Celts.) In return, sea-going Irish chieftains captured slaves in the Nordic countries (giving rise to a gene strain of blond Celts), the rest of the British Isles, and even France.

Patrick, or Patricius, was the son of a well-to-do Roman living in Britain, then Britannia. He had been born some time between 390 and 400. (Yes, that’s a three-digit year number.) His parents, while nominally Christian, were not devout by any means, and Patrick was an atheist.

When he was 15, Irish pirates raided near his home, and he was captured and taken back to Ireland and sold as a slave.

For the next six years, Patrick herded sheep, lived in a stone hovel, and enjoyed no rights at all. He was, understandably, miserable. To make his life more bearable, he turned to prayer, and came to believe that it was because of his previous disbelief that God had chosen for him to become a slave. His devotion to Christianity earned him the mocking name “Holy Boy” among the other slaves.

Finally Patrick was visited with a dream. He dreamed that he should leave his master and find his way home. He walked through 185 miles of wilderness, found passage on a ship, and made it back home to his parents in Britain.

Once there, he had another dream. This time, he dreamed that the people of Ireland were calling for him to bring them Christianity. Patrick used his family’s resources to get schooling to become a priest. When this was finished, he went back to Ireland.

His task was daunting, and some say, has never really been completed. He faced a network of warring Irish kings, each controlling their own territory, often financed by piracy. The religion of Ireland was a form of Celtic paganism, presided over by Druidic priests and heavily ingrained into the culture. Though Patrick made inroads, it could not be truly said that he converted the Irish to Christianity. He merely started the process.

Patrick died in about 460, and faded into obscurity. But years later, when Christianity was more popular on the island, he was recalled as the originator of the religion. In the Irish tradition of heroes, it was expected that Patrick should have some adventures or accomplishments.

The story of chasing the snakes out of Ireland is a metaphor for overcoming paganism, since the snake was a symbol of re-birth for pagans. Followers also invented epic magic battles between Patrick and the Druids. Even the date of Patrick’s death, March 17th, was nothing more than a guess.

For centuries, St Patrick’s Day was merely a church holiday, and was not celebrated any differently than any other saint’s day. But Irish immigrants to America, missing their homeland, began to celebrate more and more extravagantly. Parades, dances and parties were not in Patrick’s style, as he was a quiet man, much more given to quiet contemplation and prayer.

In fact, Patrick would probably be horrified by all the drunkenness that now accompanies the supposed anniversary of his death.

So, if you don’t want to drink to St. Patrick, drink to the pirates who captured him. Without them Ireland wouldn’t have its patron saint, and we wouldn’t have green beer.

Published on March 16, 2015 18:23

March 9, 2015

Reviewing Black Sails

As some of you may know, I’ve been reviewing the Starz TV show, Black Sails. I have not written about the show here, partially because I had a hard time making up my mind about the show.

The premise worried me from the start. It involves a “realistic” world of pirates… But one where Long John Silver and Captain Flint are two of the main players. For those who don’t recognize the names (can that be possible?) these are characters from Treasure Island. The other really big problem was the executive producer, Michael Bay, the man responsible for the loudest summer movies of all time. It just didn’t look good.

But then I received a phone call. It was Mike Cecchini from DenofGeek. They wanted a pirate expert to review the show for their site. I jumped at the chance. And since then I’ve been posting every week, letting people know what’s good and what’s bad about the show.

The first episode introduced the characters and did most of the things I expected of a competent series on a cable network – including hyper violence and lesbian sex. But they had some honest-to-god pirate scholars on the payroll, and some stuff looked good coin out of the gate. For instance, when the pirates robbed their first ship, they didn’t kill anybody. Instead, they did what real pirates did, and started recruiting.

Some weird stuff cropped up, too. Eleanor Guthrie, the one requisite blond/pretty female character was just as shrill, caustic and unstable as any woman concocted by men who are afraid of feminists. And the smart, thoughtful woman (Max) was always betting beaten up, gang-raped, etc. I had my doubts.

Probably the lowest point in the show was when the pirate Jack Rackham showed up wearing a pair of sunglasses. I was already annoyed because the Jack from the show bore so little resemblance to the tough-guy historical pirate. (That’s my personal problem by the way… the character in the show is interesting enough and serves the plot very well. We all have our little issues.)

The sunglasses issue was enough to cause me to complain – and I actually got a reply from the show! It turned out that they had actually done research on this, and it was just BARELY possible for the sunglasses to be real.

More problematic were the tactics used by Captain Flint it was pretty obvious that the scripts just kind of said “we need to make this take several hours” and so Flint would mysteriously forget how to use an axe, or steal stuff.

But overall, it was good. Charles Vane, the character who seemed obviously a one-dimensional bad-guy developed some real personality. John Silver had some great nods to his later self in Treasure Island. He learned to cook. He also started a relationship with the mixed race girl, Max, possibly as a foreshadowing of Silver’s mulatto wife in the book.

And it was the most accurate representation of pirates I’d ever seen.

Over the summer, I watched the NBC series, Crossbones, and learned something else. When a network isn’t really behind a series, things can fall apart fast. I watched NBC mutilate what could have been a really good pirate show, and became a lot more affectionate toward Black Sails.

This year the show has been fantastic. The pirates have never once forgotten how to pirate. The cinematography is beautiful. This was true before, but in its second season the show has a little more time to linger over a vine twining up the stairway of a ruined house, the play of light on water, or the glare of sunlight.

The characters are no longer rushed. They are no longer forced by plot points to do stupid stuff just to keep the plot moving. The plot has become organic, flowing. Even Eleanor has almost completely stopped being a bitch.

The last episode took place over a single evening. Shot entirely by firelight, each character confronts personal crisis, forced to decide how much they will give up in order to have the thing they want most in the world. And just like real pirates, what most of them want is freedom.

Black Sails has been picked up for a third season.

The premise worried me from the start. It involves a “realistic” world of pirates… But one where Long John Silver and Captain Flint are two of the main players. For those who don’t recognize the names (can that be possible?) these are characters from Treasure Island. The other really big problem was the executive producer, Michael Bay, the man responsible for the loudest summer movies of all time. It just didn’t look good.

But then I received a phone call. It was Mike Cecchini from DenofGeek. They wanted a pirate expert to review the show for their site. I jumped at the chance. And since then I’ve been posting every week, letting people know what’s good and what’s bad about the show.

The first episode introduced the characters and did most of the things I expected of a competent series on a cable network – including hyper violence and lesbian sex. But they had some honest-to-god pirate scholars on the payroll, and some stuff looked good coin out of the gate. For instance, when the pirates robbed their first ship, they didn’t kill anybody. Instead, they did what real pirates did, and started recruiting.

Some weird stuff cropped up, too. Eleanor Guthrie, the one requisite blond/pretty female character was just as shrill, caustic and unstable as any woman concocted by men who are afraid of feminists. And the smart, thoughtful woman (Max) was always betting beaten up, gang-raped, etc. I had my doubts.

Probably the lowest point in the show was when the pirate Jack Rackham showed up wearing a pair of sunglasses. I was already annoyed because the Jack from the show bore so little resemblance to the tough-guy historical pirate. (That’s my personal problem by the way… the character in the show is interesting enough and serves the plot very well. We all have our little issues.)

The sunglasses issue was enough to cause me to complain – and I actually got a reply from the show! It turned out that they had actually done research on this, and it was just BARELY possible for the sunglasses to be real.

More problematic were the tactics used by Captain Flint it was pretty obvious that the scripts just kind of said “we need to make this take several hours” and so Flint would mysteriously forget how to use an axe, or steal stuff.

But overall, it was good. Charles Vane, the character who seemed obviously a one-dimensional bad-guy developed some real personality. John Silver had some great nods to his later self in Treasure Island. He learned to cook. He also started a relationship with the mixed race girl, Max, possibly as a foreshadowing of Silver’s mulatto wife in the book.

And it was the most accurate representation of pirates I’d ever seen.

Over the summer, I watched the NBC series, Crossbones, and learned something else. When a network isn’t really behind a series, things can fall apart fast. I watched NBC mutilate what could have been a really good pirate show, and became a lot more affectionate toward Black Sails.

This year the show has been fantastic. The pirates have never once forgotten how to pirate. The cinematography is beautiful. This was true before, but in its second season the show has a little more time to linger over a vine twining up the stairway of a ruined house, the play of light on water, or the glare of sunlight.

The characters are no longer rushed. They are no longer forced by plot points to do stupid stuff just to keep the plot moving. The plot has become organic, flowing. Even Eleanor has almost completely stopped being a bitch.

The last episode took place over a single evening. Shot entirely by firelight, each character confronts personal crisis, forced to decide how much they will give up in order to have the thing they want most in the world. And just like real pirates, what most of them want is freedom.

Black Sails has been picked up for a third season.

Published on March 09, 2015 21:37

March 2, 2015

10 Terrible Misconceptions About Pirates

1. Pirates were very bad guys.

Many movies and books portray pirates as really, really bad guys. Not only do they take things that don’t belong to them (kind of a requisite for the job) but they murdered whole crews of merchant ships, burned towns, raped and tortured.

In fact: While few pirates were ever Sunday-school teachers, most of them were no worse than any other blue-collar workers of the time. They were rough, but they rarely hurt people, and the number of murders committed by Golden-Age pirates was much smaller than might be imagined.

2. Pirate captains ruled with an iron hand

We see images all the time of pirate captains stomping around giving orders, threatening beatings (the floggings will continue until moral improves) even shooting members of their own crews.

In fact: On a pirate ship, the power lay with the crew, not the captain. Captains needed the crew’s approval before attacking a ship, changing course, making an alliance or breaking one. Pirate captains were voted in and voted out regularly.

3. Pirates spent months and years at sea.

Movies give us strange ideas about life at sea. Sometimes it seems like pirates in films never come to shore – or if they do, it’s just to burn a few buildings, capture a fort, drink and whore for an evening, and then head out on their trusty pirate ship.

In fact: The point of piracy wasn’t to spend all their time crowded onto a boat. Ship time was work time, and time on shore was for having a good time. Obviously, the idea was to maximize the fun. On average, the ordinary pirate spent more time whooping it up in town than at sea, and tried to maximize that difference.

4. Pirates treated women terribly.

We’ve all seen this kind of stuff… Rape, pillage, kidnap, and then during downtime beat up the bar maid. Or maybe pay for a quick frolic between the sheets, but then head back out to sea as quickly as possible. Best not to be a woman when pirates are around.

In fact: Like most men who spend large amounts of time away from the fairer sex, pirates wanted more than just a quick screw when female company was available. They wanted to take a woman out to eat, take her dancing, and maybe even move in together. Some prostitutes, in fact, only catered to pirates and sailors because they received significantly better treatment from these men than from other customers.

5. Pirates had hook hands, peg legs and eye patches.

The surest way to identify a pirate in a picture is to draw in one or more of these disabilities.

In fact: These tags were popularized by writers eager to create distinctive pirate characters. In fact, pirates were no more likely than other sailors to suffer this kind of injury. And pirates who did lose body parts were compensated by their crews, and were able to buy a business and retire from the sea.

6. Pirates had a distinctive way of speaking.

We’ve heard this:” Arr! Avast there, matey! I be a pirate, and my mates be pirates as well!” You can always tell a pirate by the way he speaks.

In fact: The accent that we think of as being “pirate” is the creation of one man – Robert Newton, who played Long John Silver for Walt Disney. It’s a real accent, from a part of England that produced more than its share of pirates and smugglers. But pirates could come from anywhere and their accents might be Irish, French, English, African, and even nationalities like Greek, Spanish, Italian or Native American.

7. Pirate ships were huge and intimidating.

From Captain Hook’s Jolly Roger to the Black Pearl, pirate ships have a certain look: Tall, with a raised platform in the back, big square sails on three masts, and a huge number of guns.

In fact: Pirate ships were small and nimble, usually with only one or two masts, and most often had triangular sails. Most pirates carried fewer than 10 guns. And some of the most famous pirates started with not much more than a canoe.

8. Pirates were white guys.

Oh, maybe there were one or two people of color in a pirate crew. But, after all, most pirates were English, and any differences were just anomalies that added variety to a mostly Caucasian crew.

In fact: Pirates often freed African slaves and allowed these people to join their crews, so the percentages of Africans in pirate crews was often very high. For a while, Black Sam Bellamy had more Africans than Europeans in his crew. And there are rumors that Blackbeard himself had African ancestry.

9. Pirates buried treasure.

When a pirate captain amassed a huge amount of gold, he headed to some secluded island, buried it, killed the crew members who had helped him, and made a map, which he jealously guarded.

In fact: It’s all hogwash. Pirates didn’t live very long (most people didn’t in the 18th century) and hiding gold made no sense at all. The point was to spend it. Even if for some reason, pirates wanted to bury treasure, any captain who tried that kind of shenanigans would immediately lose his job.

10. Pirates wore striped socks.

In fact: You got me on that one. Striped socks were an expensive item of clothing for a working-class guy, and it was just the kind of hey-look-at-me-I’m-rich kind of accessory that a real pirate might wear when he dressed up to go into town.

Many movies and books portray pirates as really, really bad guys. Not only do they take things that don’t belong to them (kind of a requisite for the job) but they murdered whole crews of merchant ships, burned towns, raped and tortured.

In fact: While few pirates were ever Sunday-school teachers, most of them were no worse than any other blue-collar workers of the time. They were rough, but they rarely hurt people, and the number of murders committed by Golden-Age pirates was much smaller than might be imagined.

2. Pirate captains ruled with an iron hand

We see images all the time of pirate captains stomping around giving orders, threatening beatings (the floggings will continue until moral improves) even shooting members of their own crews.

In fact: On a pirate ship, the power lay with the crew, not the captain. Captains needed the crew’s approval before attacking a ship, changing course, making an alliance or breaking one. Pirate captains were voted in and voted out regularly.

3. Pirates spent months and years at sea.

Movies give us strange ideas about life at sea. Sometimes it seems like pirates in films never come to shore – or if they do, it’s just to burn a few buildings, capture a fort, drink and whore for an evening, and then head out on their trusty pirate ship.

In fact: The point of piracy wasn’t to spend all their time crowded onto a boat. Ship time was work time, and time on shore was for having a good time. Obviously, the idea was to maximize the fun. On average, the ordinary pirate spent more time whooping it up in town than at sea, and tried to maximize that difference.

4. Pirates treated women terribly.

We’ve all seen this kind of stuff… Rape, pillage, kidnap, and then during downtime beat up the bar maid. Or maybe pay for a quick frolic between the sheets, but then head back out to sea as quickly as possible. Best not to be a woman when pirates are around.

In fact: Like most men who spend large amounts of time away from the fairer sex, pirates wanted more than just a quick screw when female company was available. They wanted to take a woman out to eat, take her dancing, and maybe even move in together. Some prostitutes, in fact, only catered to pirates and sailors because they received significantly better treatment from these men than from other customers.

5. Pirates had hook hands, peg legs and eye patches.

The surest way to identify a pirate in a picture is to draw in one or more of these disabilities.

In fact: These tags were popularized by writers eager to create distinctive pirate characters. In fact, pirates were no more likely than other sailors to suffer this kind of injury. And pirates who did lose body parts were compensated by their crews, and were able to buy a business and retire from the sea.

6. Pirates had a distinctive way of speaking.

We’ve heard this:” Arr! Avast there, matey! I be a pirate, and my mates be pirates as well!” You can always tell a pirate by the way he speaks.

In fact: The accent that we think of as being “pirate” is the creation of one man – Robert Newton, who played Long John Silver for Walt Disney. It’s a real accent, from a part of England that produced more than its share of pirates and smugglers. But pirates could come from anywhere and their accents might be Irish, French, English, African, and even nationalities like Greek, Spanish, Italian or Native American.

7. Pirate ships were huge and intimidating.

From Captain Hook’s Jolly Roger to the Black Pearl, pirate ships have a certain look: Tall, with a raised platform in the back, big square sails on three masts, and a huge number of guns.

In fact: Pirate ships were small and nimble, usually with only one or two masts, and most often had triangular sails. Most pirates carried fewer than 10 guns. And some of the most famous pirates started with not much more than a canoe.

8. Pirates were white guys.

Oh, maybe there were one or two people of color in a pirate crew. But, after all, most pirates were English, and any differences were just anomalies that added variety to a mostly Caucasian crew.

In fact: Pirates often freed African slaves and allowed these people to join their crews, so the percentages of Africans in pirate crews was often very high. For a while, Black Sam Bellamy had more Africans than Europeans in his crew. And there are rumors that Blackbeard himself had African ancestry.

9. Pirates buried treasure.

When a pirate captain amassed a huge amount of gold, he headed to some secluded island, buried it, killed the crew members who had helped him, and made a map, which he jealously guarded.

In fact: It’s all hogwash. Pirates didn’t live very long (most people didn’t in the 18th century) and hiding gold made no sense at all. The point was to spend it. Even if for some reason, pirates wanted to bury treasure, any captain who tried that kind of shenanigans would immediately lose his job.

10. Pirates wore striped socks.

In fact: You got me on that one. Striped socks were an expensive item of clothing for a working-class guy, and it was just the kind of hey-look-at-me-I’m-rich kind of accessory that a real pirate might wear when he dressed up to go into town.

Published on March 02, 2015 15:35

February 23, 2015

Rum - The Favorite Drink of Pirates

Rum and pirates belong together just like peanut butter and jelly. It’s hard to imagine one without the other. Part of this is probably because rum was created and grew up along with the Golden Age of Piracy, and in the same place.

Liquor made from sugar had been known for hundreds – maybe thousands – of years, mostly in Asia. Marco Polo wrote about “sugar wine.” Brum, a drink popular in Malaysia, has existed throughout recorded time.

We don’t know where the word rum comes from. Theories include an abbreviation of one of several Latin words, a Romani word meaning “strong”, and rumbullion or rumbustion, two words that surfaced about the same time as “rum” – in the mid 1600’s. Since both words are slang terms for “uproar” or “loud chaos” it seems to me that it was the other way around.

We have sugar cane and the Irish to thank for rum. When the British government began shipping Irish to Barbados as slaves, they separated those people from home, family and friends. They also separated these Irish slaves from whiskey.

But it’s hard to keep the Irish from their liquor. These slaves found out that the molasses extracted from sugar cane could be fermented, and then that the fermented substance could be distilled into the liquor that we now call rum.

By 1654 – one year before the pirate Henry Morgan came onto the historical stage - the name rum was firmly attached to the popular, potent drink. By 1664, distilleries had begun to flourish in Boston and Rhode Island, taking advantage of the higher technologies in those areas to build larger distillation pots and a larger number of high-quality barrels. This produced a more standardized product. For a while, Rhode Island rum joined gold as a form of currency in Europe.

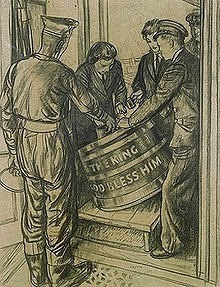

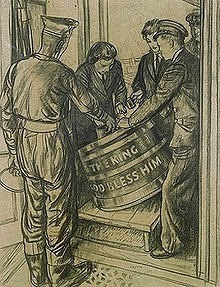

It was common at the time for navies to issue rations of liquor to sailors. Once England captured Jamaica (1655), they changed their liquor of choice from French brandy to Jamaican rum. From then on, rum became a solid part of British navy life. The ration of rum continued until July 31st, 1970, when it was discontinued because other liquor was available for recreational use. This date is still remembered in the British navy as “black tot day.”

For special occasions, however, such as a royal wedding, birth or coronation, rum is still supplied. The order for an extra tot of rum, which dates from the age of sail, is “splice the mainbrace!” This commemorates an on-ship chore which was extremely difficult and warranted an extra rum ration.

Many pirates learned to sail and fight by serving in their national navy. They learned to like rum from the same source. In Jamaica’s early days, navy support was considered too slight to keep the island secure from the Spanish. The island’s governor lured pirates to Port Royal and enlisted their support in guarding the island by offering a safe trading port for fencing stolen goods and taverns filled with bountiful rum to spend their ill-gotten gains on.

The pirate Henry Morgan, knighted, retired and appointed Jamaica’s acting Governor, drank himself to death in these taverns, reliving his glory days in the sweet trade. Rum and prostitution caused Port Royal to be known as the “wickedest city on earth.”

One of rum’s many nicknames was “kill devil.” A 1651 document from Barbados stated, "The chief fuddling they make in the island is Rumbullion, alias Kill-Divil, and this is made of sugar canes distilled, a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor." Pirates and others drank it so consistently they became dependent, and without it began to see hallucinations. Lack of rum on a pirate ship was a cause for desperate action, including robbing ships that the pirates had previously agreed were off-limits.

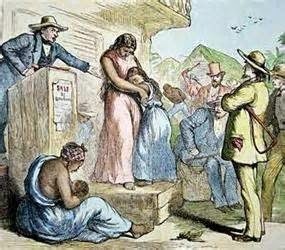

Rum encouraged the “triangle trade” that was partially responsible for the region’s wealth, which in turn drew pirates to the Caribbean. Merchant ships picked up sugar, rum and molasses on Barbados and Jamaica, transported them to New England, where more rum was distilled from the raw materials. Then this rum was taken to Europe and exchanged for trade goods such as cloth and beads, which was then transported to Africa and traded for slaves, which were taken back to the Caribbean to work the sugar plantations.

This cemented the practice of using African slaves, who were hardier than Europeans, and lived longer in the tropics. It also encouraged regular trade routes, enabling the pirates to lay in ambush in known areas.

Rum also encouraged larceny inside the navy. When Admiral Nelson, England’s national hero, was killed in action at sea, legend has it that his body was preserved by sealing it inside a full cask of rum. But when the ship arrived back in port and the cask was opened it was empty. Enterprising sailors had tapped it and drunk every last drop, leaving only the Admiral’s body. After that, rum was often referred to as “Nelson’s blood.”

Author Robert Lewis Stevenson had a profound influence on the link between pirates and rum when he included “Fifteen men on a dead man’s chest, Yo Ho Ho and a bottle of rum” in his famous novel Treasure Island. And Johnny Depp cemented it farther with Captain Jack Sparrow’s wandering walk and question, “Why is the rum gone?”

In real life, pirates drank pretty much anything that would get them drunk, but whiskey, brandy, wine and gin have their own mythologies. Rum now belongs forever to the pirates, famous in song and story.

Let’s raise a glass and say, “Yo Ho!”

Liquor made from sugar had been known for hundreds – maybe thousands – of years, mostly in Asia. Marco Polo wrote about “sugar wine.” Brum, a drink popular in Malaysia, has existed throughout recorded time.

We don’t know where the word rum comes from. Theories include an abbreviation of one of several Latin words, a Romani word meaning “strong”, and rumbullion or rumbustion, two words that surfaced about the same time as “rum” – in the mid 1600’s. Since both words are slang terms for “uproar” or “loud chaos” it seems to me that it was the other way around.

We have sugar cane and the Irish to thank for rum. When the British government began shipping Irish to Barbados as slaves, they separated those people from home, family and friends. They also separated these Irish slaves from whiskey.

But it’s hard to keep the Irish from their liquor. These slaves found out that the molasses extracted from sugar cane could be fermented, and then that the fermented substance could be distilled into the liquor that we now call rum.

By 1654 – one year before the pirate Henry Morgan came onto the historical stage - the name rum was firmly attached to the popular, potent drink. By 1664, distilleries had begun to flourish in Boston and Rhode Island, taking advantage of the higher technologies in those areas to build larger distillation pots and a larger number of high-quality barrels. This produced a more standardized product. For a while, Rhode Island rum joined gold as a form of currency in Europe.

It was common at the time for navies to issue rations of liquor to sailors. Once England captured Jamaica (1655), they changed their liquor of choice from French brandy to Jamaican rum. From then on, rum became a solid part of British navy life. The ration of rum continued until July 31st, 1970, when it was discontinued because other liquor was available for recreational use. This date is still remembered in the British navy as “black tot day.”

For special occasions, however, such as a royal wedding, birth or coronation, rum is still supplied. The order for an extra tot of rum, which dates from the age of sail, is “splice the mainbrace!” This commemorates an on-ship chore which was extremely difficult and warranted an extra rum ration.

Many pirates learned to sail and fight by serving in their national navy. They learned to like rum from the same source. In Jamaica’s early days, navy support was considered too slight to keep the island secure from the Spanish. The island’s governor lured pirates to Port Royal and enlisted their support in guarding the island by offering a safe trading port for fencing stolen goods and taverns filled with bountiful rum to spend their ill-gotten gains on.

The pirate Henry Morgan, knighted, retired and appointed Jamaica’s acting Governor, drank himself to death in these taverns, reliving his glory days in the sweet trade. Rum and prostitution caused Port Royal to be known as the “wickedest city on earth.”

One of rum’s many nicknames was “kill devil.” A 1651 document from Barbados stated, "The chief fuddling they make in the island is Rumbullion, alias Kill-Divil, and this is made of sugar canes distilled, a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor." Pirates and others drank it so consistently they became dependent, and without it began to see hallucinations. Lack of rum on a pirate ship was a cause for desperate action, including robbing ships that the pirates had previously agreed were off-limits.

Rum encouraged the “triangle trade” that was partially responsible for the region’s wealth, which in turn drew pirates to the Caribbean. Merchant ships picked up sugar, rum and molasses on Barbados and Jamaica, transported them to New England, where more rum was distilled from the raw materials. Then this rum was taken to Europe and exchanged for trade goods such as cloth and beads, which was then transported to Africa and traded for slaves, which were taken back to the Caribbean to work the sugar plantations.

This cemented the practice of using African slaves, who were hardier than Europeans, and lived longer in the tropics. It also encouraged regular trade routes, enabling the pirates to lay in ambush in known areas.

Rum also encouraged larceny inside the navy. When Admiral Nelson, England’s national hero, was killed in action at sea, legend has it that his body was preserved by sealing it inside a full cask of rum. But when the ship arrived back in port and the cask was opened it was empty. Enterprising sailors had tapped it and drunk every last drop, leaving only the Admiral’s body. After that, rum was often referred to as “Nelson’s blood.”

Author Robert Lewis Stevenson had a profound influence on the link between pirates and rum when he included “Fifteen men on a dead man’s chest, Yo Ho Ho and a bottle of rum” in his famous novel Treasure Island. And Johnny Depp cemented it farther with Captain Jack Sparrow’s wandering walk and question, “Why is the rum gone?”

In real life, pirates drank pretty much anything that would get them drunk, but whiskey, brandy, wine and gin have their own mythologies. Rum now belongs forever to the pirates, famous in song and story.

Let’s raise a glass and say, “Yo Ho!”

Published on February 23, 2015 19:46

February 16, 2015

Cutlass Liz

I first became aware of Cutlass Liz in the movie The Pirates(2005). I was interested in the character, because the movie features a lot of other historical figures (ripped entirely out of time, mind) from Black Sam Bellamy to Queen Victoria. Liz, however, was a pirate I’d never heard of. But since the main characters in the movie are all (very) fictional, it didn’t bother me.

Then I did some research.

The legend of Elizabeth Shirland goes back quite a ways. It should, because Cutlass Liz began her career in the earliest days of piracy. The story goes that she was born in Devon the most sea-going of English counties, sometime between 1550 and 1560.

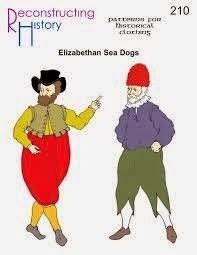

For reasons known only to herself, she decided while in her early teens that she was not going to live the life assigned to her. The story says that she disguised herself as a man (easy to do with the baggy clothes of the day) and went to sea as a sailor.

By 1577 she had enough experience to join the crew of the Golden Hinde and sail under none other than Frances Drake, the king of the Buccaneering Pirates. Drake was just embarking on the voyage that made his fortune – a round the world trip, with stop-offs to raid Spanish shipping and towns all over Central and South America.

Drake brought back so much gold that he became a legend. He had been backed in this endeavor by Queen Elizabeth I, and brought back so much gold that the queen’s share paid off the national debt. Elizabeth didn’t share in this acclaim, but she did get hooked on a life of adventure and piracy.

Elizabeth next turns up with her own ship – perhaps the result of the huge share of plunder that a sailor working for Drake would have received. She headed immediately for the Spanish Main, where she tried to live up to Drake’s legacy. She was very successful as a pirate.

However, according to legend, she also began to live openly as a woman, and to take lovers from among her crew. This led to trouble. Apparently some of these men tried to take over, and Liz earned her nickname by running them through with her trusty blade. This, in turn, led to more trouble.

Finally one of her lovers decided that he needed to get rid of her altogether. He betrayed her to the Spanish, who broke in on the two of them in the act. Elizabeth was dragged naked and screaming to the deck of her own ship, where she was summarily hanged. She did, however, murder her betrayer/lover with one last thrust of her trusty blade before she was dragged to her death.

There are reasons to believe that this story is true. Women did disguise themselves as men and go to sea. And anyone who survived Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe would have had more than enough money to buy a ship outright. It’s also believable that, owning a ship and captaining it herself may have given a woman enough confidence to think she could reveal her sex without consequences. That this wouldn’t work out for her also seems entirely believable.

However, the story has its flaws. Historians have identified an Elizabeth Shirland who married, had one child and lived her life quietly in Devon, never going to sea at all. But Elizabeth was one of the most popular names in England at the time, and Shirland was also quite common. There may have many women with similar names.

Another point against the legend is that “Liz” was not a common nickname for Elizabeth at the time. “Bess” was far more popular. (We can mitigate this by noting that the name "Liz" was used, but it seemed to have indicated a low sort of woman.) Also, the word “cutlass” was not in common use. The type of sword later called a cutlass was more commonly called a “hanger” because it hung off the belt. So “Hanger Bess” seems a more likely name.

It’s also pretty obvious that Liz’s behavior and fate seems to indicate a certain amount of male wish fulfillment.

Another piece of the story is even more far-fetched. This rumor says that Liz was a member of the lost colony of Roanoke. Captured by hostile natives, she lived with them for a while as a slave, then stabbed her owner with his own knife and escaped. She was picked up by the Spanish, then rescued by Drake just in time to go on his historic trip.

This seems far too unbelievable to be true, and is further discredited by the fact that we have a complete list of the Roanoke colonists, and she wasn’t one of them. In this version of the story, she also wins mountains of gold that far outshine those brought back by her mentor.

We’ll probably never be sure of the truth in all this. I see a person who may very well have lived, and who became a nexus for any bits of fiction that sailors cared to attach to her. Someone wanted to tell his “Cutlass Liz” story when other people were discussing Roanoke, and modified the tale accordingly. Someone else was talking about Drake’s mountains of treasure, and someone else wanted to out-do him.

I find this far the most believable version of events. But you can make up your own mind.

Then I did some research.

The legend of Elizabeth Shirland goes back quite a ways. It should, because Cutlass Liz began her career in the earliest days of piracy. The story goes that she was born in Devon the most sea-going of English counties, sometime between 1550 and 1560.

For reasons known only to herself, she decided while in her early teens that she was not going to live the life assigned to her. The story says that she disguised herself as a man (easy to do with the baggy clothes of the day) and went to sea as a sailor.

By 1577 she had enough experience to join the crew of the Golden Hinde and sail under none other than Frances Drake, the king of the Buccaneering Pirates. Drake was just embarking on the voyage that made his fortune – a round the world trip, with stop-offs to raid Spanish shipping and towns all over Central and South America.

Drake brought back so much gold that he became a legend. He had been backed in this endeavor by Queen Elizabeth I, and brought back so much gold that the queen’s share paid off the national debt. Elizabeth didn’t share in this acclaim, but she did get hooked on a life of adventure and piracy.

Elizabeth next turns up with her own ship – perhaps the result of the huge share of plunder that a sailor working for Drake would have received. She headed immediately for the Spanish Main, where she tried to live up to Drake’s legacy. She was very successful as a pirate.

However, according to legend, she also began to live openly as a woman, and to take lovers from among her crew. This led to trouble. Apparently some of these men tried to take over, and Liz earned her nickname by running them through with her trusty blade. This, in turn, led to more trouble.

Finally one of her lovers decided that he needed to get rid of her altogether. He betrayed her to the Spanish, who broke in on the two of them in the act. Elizabeth was dragged naked and screaming to the deck of her own ship, where she was summarily hanged. She did, however, murder her betrayer/lover with one last thrust of her trusty blade before she was dragged to her death.

There are reasons to believe that this story is true. Women did disguise themselves as men and go to sea. And anyone who survived Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe would have had more than enough money to buy a ship outright. It’s also believable that, owning a ship and captaining it herself may have given a woman enough confidence to think she could reveal her sex without consequences. That this wouldn’t work out for her also seems entirely believable.

However, the story has its flaws. Historians have identified an Elizabeth Shirland who married, had one child and lived her life quietly in Devon, never going to sea at all. But Elizabeth was one of the most popular names in England at the time, and Shirland was also quite common. There may have many women with similar names.

Another point against the legend is that “Liz” was not a common nickname for Elizabeth at the time. “Bess” was far more popular. (We can mitigate this by noting that the name "Liz" was used, but it seemed to have indicated a low sort of woman.) Also, the word “cutlass” was not in common use. The type of sword later called a cutlass was more commonly called a “hanger” because it hung off the belt. So “Hanger Bess” seems a more likely name.

It’s also pretty obvious that Liz’s behavior and fate seems to indicate a certain amount of male wish fulfillment.

Another piece of the story is even more far-fetched. This rumor says that Liz was a member of the lost colony of Roanoke. Captured by hostile natives, she lived with them for a while as a slave, then stabbed her owner with his own knife and escaped. She was picked up by the Spanish, then rescued by Drake just in time to go on his historic trip.

This seems far too unbelievable to be true, and is further discredited by the fact that we have a complete list of the Roanoke colonists, and she wasn’t one of them. In this version of the story, she also wins mountains of gold that far outshine those brought back by her mentor.

We’ll probably never be sure of the truth in all this. I see a person who may very well have lived, and who became a nexus for any bits of fiction that sailors cared to attach to her. Someone wanted to tell his “Cutlass Liz” story when other people were discussing Roanoke, and modified the tale accordingly. Someone else was talking about Drake’s mountains of treasure, and someone else wanted to out-do him.

I find this far the most believable version of events. But you can make up your own mind.

Published on February 16, 2015 19:23

February 9, 2015

A Pirate's True Love

“What’s a pirate’s favorite letter?”“You’d think it would be ‘R’ but it’s the ‘C’ they love…" This week, pirates and the only thing they love more than stolen gold. The sea that sustains them.

The one thing that pirates needed more than anything was salt water to sail on. In fact the very definition of ‘pirate’ is that of a sea-going robber. The sea comes first. After many famous pirates won gold and treasure enough to make them rich for life, they could not resist the lure of the open ocean. It’s the reason so few pirates successfully retired.

What makes the sea call so strongly?

You might ask that question of anyone. The sounds, smell and sight of water are ingrained in the human psyche. When show pictures of places – be they urban, rural or wilderness, humans consistently rate their beauty and desirability higher if there is water shown. The sound of waves lapping on the shore is packaged onto CD’s and sold as a sleep-aid. As a species simply love water.

Some people believe that we get this before we’re even born. The sounds of a mother’s blood, rushing through her veins, the gurgle of her stomach, these are the first sounds and unborn child hears. And the first sensation it feels is the gently floating, rocking feeling of being supported in fluid as mother walks and moves.

It may be hard to tie these gentle images to, say, Blackbeard. But it’s a fact that, after he had amassed his stolen fortune, he established himself as a gentlemen, bought a house etc. and then he risked it all… fatally… to return to sailing. His desire to spend time in a boat was his undoing, and brought him death in an increasingly civilized world.

Some scientists, however, believe that the love of the ocean is even more primal than pre-birth memories. They cite the fact that the mineral makeup of the human body is almost exactly that of the sea. And the fetus, in its very early stages, goes through a period when it has gills and a tail. They think that we’re programmed from the beginning of out earliest ancestors to want to live near water.[image error]

And, in fact, in the current age, an estimated 80% of the world’s population lives within 80 miles of a coastline.

The pirate captain Stede Bonnet may have been mad. But his particular madness showed itself in a desire to run away to sea… not to some foreign land where his upper-middle-class riches woud have done him some good, and his family name would have been useful. No, Bonnet ran away to sea, in spite of knowing nothing about sailing or navigation. The sea had called him.

There’s a story of a sailor who, tired of the hardships of his previous life, took up his small bag of possessions, slung an oar over his shoulder, and began to walk inland. The story goes that, when someone asked him, “What’s that great long piece of wood you’re carrying around?” the sailor knew that he was far enough inland that he was safe from the sea’s call.

The sea has inspired innumerable songs of love and longing. People who have never hauled on a ship’s rigging in their lives sing and enjoy sea shanties, and the sea has figures in love songs from the pirate’s day to the present. The sea is the rocking, rolling over who called the sailor from his home and family, no matter how much he way wish to be safe and dry.

“Oh a landsman’s life is all his own, he can go or he can stayBut when the sea is in your blood, when She calls you much obey.”Goes one old song.

The sea is a woman. Most cultures agree on this (sorry, Poseidon). It comes from the changeable nature of the ocean, no doubt. One minute it can be fair, gentle and kind, and a moment later a squall develops out of nowhere and the sailors are fighting for their lives. Very much like a woman’s temper. The men who sail her have no idea what’s going on, just as men don’t understand their wives and sweethearts. But the love and the endless attraction is still there.

I’ll end with one of my favorite images of a retired pirate. Billy Bones, from Treasure Island, who sailed with Flint and amassed a small fortune. To retire, he chooses the Admiral Benbow Inn, an impoverished place that is still close to the water. Billy is afraid his old shipmates will hunt him down, but he still can’t be away from his true love. Every day he goes out alone, to look at the sea. It’s all he wants.

If you want to give your pirate-loving significant other a unique Valentin's gift, order a copy of "Gentlemen and Fortune" or "Bloody Seas" by TS Rhodes!

Published on February 09, 2015 18:55

February 2, 2015

Pirate Ship’s Articles

Articles… What’s that? Stories written about pirates in popular newspapers or magazines? I mean, they did have magazines back in the early 1700’s, right?

No, wait a minute. Ship’s articles were an employment contract between sailors and the ships they crewed. It was a basic system between workers and employers, naming work times and conditions, payment and pay frequency. Simple as that.

So then what’s the big deal? And why did pirates even need these things. They weren’t employees of anybody, after all.

To begin with, people rarely build things from nothing. Pirates were doing radical stuff, but they still built upon the structure that they were used to, and as sailors they were used to having a work contract. So they based their pirating Articles upon those they has used before they “went on the account.”

Merchant ships wanted to lock sailors into work contracts for as long as possible. Sailors, by definition, traveled, and that meant stopping in ports where wages may have been higher than those at the port where they signed on. Employers didn’t want them to leave the ship just because someone else was offering more money. Forcing an employee to sign a work contract was supposed to stop this kind of self-serving behavior.

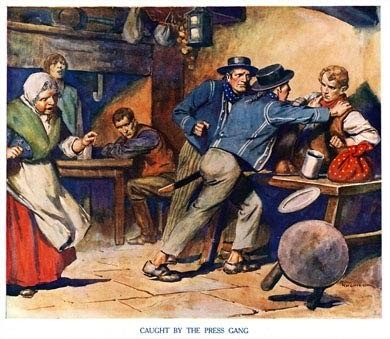

Also, locking a sailor into a months-long contract gave the merchant captain more flexibility in where the ship would sail to. There were places where sailors simply didn’t want to go. Parts of Africa were known to harbor infectious diseases, which might kill 90% of a European crew. Some European ports harbored a “hot press” – enthusiastic press gangs that kidnapped sailors and forced them to serve in the country’s navy – often for years and often without pay.

Sailors, rightly, wanted to avoid such places. Merchant captains wanted to go where the money was. At the time we’re talking about, there were hardly any shipping schedules or regular trade routes. Ships took on what cargo they could find, and traveled to places where there was a market for the goods. When sailor signed on, they received a promise not to sail to certain ports.

Interestingly, in much the same way huge companies today get away with sketchy business practices, the authorities considered it okay for merchant captains and merchant consortiums to renege on these contracts. It was “the vagaries of the business” that caused sub-standard food to be served, or the ship to change course and sail to a disease-ridden coast.

For their own, sailors often “jumped ship” and took off for better pay or better working conditions. Sometimes they were jailed for this, if they could be caught.

Still, pirates signing onto a pirate ship expected some kind of contract.

Unlike the merchant articles, the pirate version was a “bottom up” document. While merchant captains dictated terms to the crew, pirate crews dictated terms to their captains. Pirate articles listed the things the crew wanted. Everybody signed, and captain, officers and crew were all held to it equally.

Some things were universal. Pirates operated on a “no prey no pay” basis. Participants took shares of plunder, not wages. A certain percentage was set aside for purchase of supplies and maintenance of the boat. After that, plunder was broken into “shares” based on the number of individuals in the crew, though this was not quite a one-on-one ratio.

Pirates agreed that their officers, work specialists (such as gunnery master or carpenter) and captain were highly skilled individuals worthy of a higher percentage of plunder. However, while privateer and merchant captains made 20 to 80 times the amount of a single member of their crews, pirate captains usually made 1 ½ to 2 times as much. Articles specified the amount – a breakdown that often looked something like this: Captain 2 shares, commissioned officers (first mate, navigator) 1 ½ shares, non-commissioned officers (bosun, carpenter) 1 ¼ shares, all sailors (at any skill level) 1 share, and landsmen and servants (people with no sailing skills, such as the ship’s fiddler) ½ share. Notice that no one makes more than 4 times the rate of the lowest-paid, unskilled worker.

Pirate articles did not generally mention where the ship was bound for. That was decided by vote on a day-to-day basis.

Pirate articles required that each member of the crew keep weapons clean and ready to use. This was in contrast to merchant crews, who were not encouraged to use or own weapons. In pirate crews terror, not cargo, was their stock-in-trade. The ability to fight, or to at least appear ready to fight, was primary.

On merchant ships liquor was regulated and drunkenness highly discouraged. On most pirate ships it was the opposite. Liquor was one of the few ready pleasures in a world where life was often short and brutish. Pirate articles specified that liquor was freely available to anyone who wanted it. Being drunk was okay, as long as you could do your job.

Interestingly, honesty was required on a pirate ship. Stealing from a fellow pirate was a definite no-no. Spoils were divided in the open, to prevent any hanky-panky, and witnesses say that pirates didn’t guard their treasure while on board ship. Instead, money was held in common until called for.