T.S. Rhodes's Blog, page 17

January 19, 2015

Voodoo Dolls

Like Zombies, “Voodoo dolls” are a prominent part of Caribbean myth, and tied to several works that include pirates. What were these dolls, and how did they figure into the Vodou religion?

To begin with, this sort of “magical doll” is linked to many more religions. In fact, magical dolls had been a prominent part of Christianity for some time. The principal behind the dolls was pretty universal. If you want to do magic on a person or thing – say, the Brooklyn Bridge or your History teacher – and you can’t actually have that thing around, you make a model, link the model with the real thing through magic, and then work magic on the model or doll.

If my target is the Brooklyn Bridge, I’d start out by making a model, keeping as close to the building materials of the original as possible. Of course, if I’m not skilled at model making, I may have to resort to a snap-together plastic kit. Once the model is made, the model and the original must be linked. This might involve painting it with the same type of paint used on the real thing, daubing it with dirt brought from the bridge, adding the poop of pigeons or sea gulls. I’d spend a lot of time Telling my model that it really was the Brooklyn Bridge. Then I’d stage traffic jams on it, or cut cables. Whatever I wanted to happen to the real thing.

Conveniently, if nothing happened to the real bridge, it would only mean that I hadn’t linked my model and the original well enough.

New England Poppet from the Salem Witch House

New England Poppet from the Salem Witch House

If a middle school girl has a crush on her history teacher, and wants to create a romance, she would make a doll representing him. Instruction manuals suggested forming the doll out of the loved one’s clothing, or stuffing it with clothing scraps. Identifiers such as glasses, a distinctive belt, hairstyle, etc., would be added. Then the girl would make a similar doll representing herself. The two would be tied together in a loving embrace and then hidden away in a bottom bureau drawer.

All of this may seem quite innocent, even silly, But at the time of the Golden Age of Piracy magic of this sort was a very serious business. In 1688, during the lifetime of many notable pirates, a woman names Goody Glover was executed for, among other things, tormenting those who had teased and humiliated her by means of “poppets” of puppets.

She had "several small images, or poppets, or babies, made of rags and stuffed with goat's hair and other ingredients. When these were produced the vile woman acknowledged that her way to torment the objects of her malice was by wetting of her finger with her spittle and stroking of these little images."

Cotton Mather, the same New England cleric who visited and wrote about Bellamy’s crew as they lay in prison after the sinking of the Whydah, also visited and wrote about Goody Glover. In this case, he noted that she "took a stone, a long and slender stone, and with her finger and spittle fell to tormenting it; though whom or what she meant, I had the mercy to never understand."

The Salem Witch Trials took place in 1692, and many of those accused were said to have “poppets” in their possession. And the original “witch” in the trials was a Caribbean slave woman names Tituba, who was charged with leading several Puritan girls into the forest to teach them magic and dancing – two activities held in almost equal horror by the Elders of the community.

It takes little imagination to see the slave-owners of the Caribbean, living in fear of the huge number of slaves held barely under control, projecting their own terrors and traditions onto the Africans.

While the Vodou religion remained a lower-class phenomenon in rural Haiti, it became something of a tourist attraction in more cosmopolitan New Orleans. The religion lived underground, but more theatrical priestesses made a fortune catering to rich tourists. If the “trade” wanted love magic, love magic would be produced. If something spookier was called for, a curse would be dreamed up.

Sticking pins in “Voodoo dolls” became a thing. One item that made this unique to the culture was the style of the dolls. As we’ve seen before, Vodou alters and statues were folk pieces. They were made by the very poor, and depended more on emotion than symmetry or fine materials. The asymmetrical, cobbled-together look of the dolls gives them a horrifying, alien feel.

The last question is, do these dolls work? While no one has ever proved the existence of magic, there are certainly examples of people who knew themselves to be under a curse to wither and die. Like the “placebo effect” which allows a sugar pill to cure some cases of cancer, the belief in magic was all you needed to bring a curse to life.

To begin with, this sort of “magical doll” is linked to many more religions. In fact, magical dolls had been a prominent part of Christianity for some time. The principal behind the dolls was pretty universal. If you want to do magic on a person or thing – say, the Brooklyn Bridge or your History teacher – and you can’t actually have that thing around, you make a model, link the model with the real thing through magic, and then work magic on the model or doll.

If my target is the Brooklyn Bridge, I’d start out by making a model, keeping as close to the building materials of the original as possible. Of course, if I’m not skilled at model making, I may have to resort to a snap-together plastic kit. Once the model is made, the model and the original must be linked. This might involve painting it with the same type of paint used on the real thing, daubing it with dirt brought from the bridge, adding the poop of pigeons or sea gulls. I’d spend a lot of time Telling my model that it really was the Brooklyn Bridge. Then I’d stage traffic jams on it, or cut cables. Whatever I wanted to happen to the real thing.

Conveniently, if nothing happened to the real bridge, it would only mean that I hadn’t linked my model and the original well enough.

New England Poppet from the Salem Witch House

New England Poppet from the Salem Witch HouseIf a middle school girl has a crush on her history teacher, and wants to create a romance, she would make a doll representing him. Instruction manuals suggested forming the doll out of the loved one’s clothing, or stuffing it with clothing scraps. Identifiers such as glasses, a distinctive belt, hairstyle, etc., would be added. Then the girl would make a similar doll representing herself. The two would be tied together in a loving embrace and then hidden away in a bottom bureau drawer.

All of this may seem quite innocent, even silly, But at the time of the Golden Age of Piracy magic of this sort was a very serious business. In 1688, during the lifetime of many notable pirates, a woman names Goody Glover was executed for, among other things, tormenting those who had teased and humiliated her by means of “poppets” of puppets.

She had "several small images, or poppets, or babies, made of rags and stuffed with goat's hair and other ingredients. When these were produced the vile woman acknowledged that her way to torment the objects of her malice was by wetting of her finger with her spittle and stroking of these little images."

Cotton Mather, the same New England cleric who visited and wrote about Bellamy’s crew as they lay in prison after the sinking of the Whydah, also visited and wrote about Goody Glover. In this case, he noted that she "took a stone, a long and slender stone, and with her finger and spittle fell to tormenting it; though whom or what she meant, I had the mercy to never understand."

The Salem Witch Trials took place in 1692, and many of those accused were said to have “poppets” in their possession. And the original “witch” in the trials was a Caribbean slave woman names Tituba, who was charged with leading several Puritan girls into the forest to teach them magic and dancing – two activities held in almost equal horror by the Elders of the community.

It takes little imagination to see the slave-owners of the Caribbean, living in fear of the huge number of slaves held barely under control, projecting their own terrors and traditions onto the Africans.

While the Vodou religion remained a lower-class phenomenon in rural Haiti, it became something of a tourist attraction in more cosmopolitan New Orleans. The religion lived underground, but more theatrical priestesses made a fortune catering to rich tourists. If the “trade” wanted love magic, love magic would be produced. If something spookier was called for, a curse would be dreamed up.

Sticking pins in “Voodoo dolls” became a thing. One item that made this unique to the culture was the style of the dolls. As we’ve seen before, Vodou alters and statues were folk pieces. They were made by the very poor, and depended more on emotion than symmetry or fine materials. The asymmetrical, cobbled-together look of the dolls gives them a horrifying, alien feel.

The last question is, do these dolls work? While no one has ever proved the existence of magic, there are certainly examples of people who knew themselves to be under a curse to wither and die. Like the “placebo effect” which allows a sugar pill to cure some cases of cancer, the belief in magic was all you needed to bring a curse to life.

Published on January 19, 2015 18:25

January 12, 2015

The Origin of Zombies

I promised Zombies in last week's post, since Zombies have appeared in several piratical works. What are Zombies, and where do the Zombie stories come from?

Once again, it all starts in the Caribbean. In our previous post, we discussed how Vodou is a conglomeration of African folk religions, forcibly transported to the New World and melded together by shared slavery. The Bokor or priest/priestess communed with the spirits, practiced healing arts (both spiritual and medicinal) and was a center of the slave community.

However, human nature being what it is, sometimes people want to bring bad luck to one another. When this happens, the individual could work certain charms themselves, or they could pay the Bokor to work spells on a higher level. Some Bokors did this kind of thing regularly, others did not. It wasn't seen as a big deal, either way.

One of the most powerful spells that could be worked was to create a Zombie (zonbi in the Haitian Creole language). According to legend they did this by digging up the body of a recently deceased person (sometimes poisoned or cursed to death by the Bokor), treating it with special drugs, and bring it back to life.

This Zombie would then work for the Bokor or the person who had paid for the spell. The Zombie had no mind to speak of, but it could do certain repetitive tasks, and it never suffered from hunger or became tired. A Zombie would turn the mechanism that ground sugar cane, or chop cane stalks endlessly. It never needed rest, and ate only a small amount of a special mixture prepared by the Bokor.

What made this so terrible? After all, the deceased wasn't suffering. The soul had gone on to the next world, and the mind was not re-animated by the magic. I suspect that the greatest horror was linked to the appalling conditions that the slaves worked under. Constantly undernourished, unsheltered and overworked, death must have seemed like the only release. How terrible to learn that, even after death, they must continue to work?

There were also stories of men who, turned down by a woman, paid to have her turned into a Zombie to become that man's sexual slave. While this would be horrible for the woman, it didn't tend to work out very well for the man either. Killing a woman you care for, re-animating her corpse, and then having sex with the unresponsive husk was more likely to bring madness and regret than pleasure.

How did this sort of thing happen? To the inhabitants of the island, and even to their masters, the simple word "magic" explained it all. But the modern person wants more information.

A 1962 case sheds some light. A man named Clairvius Narcisse claimed that, 20 years before, he had been poisoned by a Bokor. He fell into a trance and was presumed dead, and buried. (Because of the heat and lack of embalming, Haitian burials take place within 24 hours of death, often in as little as 12.)

Clairvius awoke in his coffin, was dug up and given a drug which made him confused and suggestible, then taken to a sugar plantation and put to work. He worked on the plantation for two years, then came back to himself somewhat and escaped, along with other workers who had been treated similarly. Still disoriented and far from home, he wandered as a homeless beggar for 18 years, before stumbling back to his home village, where he recognized his sister.

The case was investigated by several Americans, who suggested that a neurotoxin created from a local toad was the original drug which put Clairvius into his coma. Then a plant extract called datura might have been used to keep him compliant. What did the plantation owners have to gain? Free labor. All it cost was 20 years of a human life.

At first I wondered how the African slaves, recently come to the islands, could have knowledge of these drugs. However, more careful reading reminded me that they were confined with, and learned from the last of the Native islanders. The native population had studied local animals and plants for centuries, and taught their skills to the newcomers.

Whether raised by magical or mundane means, slaves feared being made into Zombies. For this reason they buried their dead as close to the homes of the living as possible, or barring that, at a crossroads (symbol of the meeting place or life and death) or even in the middle of a street, where traffic could be assumed to prevent grave-robbing.

Europeans were fascinated, and more than a little afraid of the African magic. In places like New Orleans, where people of color became free, Vodou became a bit of a tourist attraction. But in Haiti, it remained a slave religion, heathen and dangerous.

Writers and film makers took advantage of this exotic legacy. Many Americans were first introduced to Zombie in the 1932 film The White Zombie, featuring Bela Lugosi as the evil Zombi-making magician. Quickly cobbled together after the success of Dracula, the movie featured an over-the-top plot and bad acting.

Furthermore, it suffered from the fact that classical Zombies aren't very frightening. After all, they are workers who do what they are told. Creepy? Oh, yes. Creepy as anything. But not very scary. It wasn't until 1968, and Night of the Living Dead Zombies became scary. But the frights are entirely invented. Classic Vodou Zombies don't eat people.

Next week - Voodoo Dolls

Once again, it all starts in the Caribbean. In our previous post, we discussed how Vodou is a conglomeration of African folk religions, forcibly transported to the New World and melded together by shared slavery. The Bokor or priest/priestess communed with the spirits, practiced healing arts (both spiritual and medicinal) and was a center of the slave community.

However, human nature being what it is, sometimes people want to bring bad luck to one another. When this happens, the individual could work certain charms themselves, or they could pay the Bokor to work spells on a higher level. Some Bokors did this kind of thing regularly, others did not. It wasn't seen as a big deal, either way.

One of the most powerful spells that could be worked was to create a Zombie (zonbi in the Haitian Creole language). According to legend they did this by digging up the body of a recently deceased person (sometimes poisoned or cursed to death by the Bokor), treating it with special drugs, and bring it back to life.

This Zombie would then work for the Bokor or the person who had paid for the spell. The Zombie had no mind to speak of, but it could do certain repetitive tasks, and it never suffered from hunger or became tired. A Zombie would turn the mechanism that ground sugar cane, or chop cane stalks endlessly. It never needed rest, and ate only a small amount of a special mixture prepared by the Bokor.

What made this so terrible? After all, the deceased wasn't suffering. The soul had gone on to the next world, and the mind was not re-animated by the magic. I suspect that the greatest horror was linked to the appalling conditions that the slaves worked under. Constantly undernourished, unsheltered and overworked, death must have seemed like the only release. How terrible to learn that, even after death, they must continue to work?

There were also stories of men who, turned down by a woman, paid to have her turned into a Zombie to become that man's sexual slave. While this would be horrible for the woman, it didn't tend to work out very well for the man either. Killing a woman you care for, re-animating her corpse, and then having sex with the unresponsive husk was more likely to bring madness and regret than pleasure.

How did this sort of thing happen? To the inhabitants of the island, and even to their masters, the simple word "magic" explained it all. But the modern person wants more information.

A 1962 case sheds some light. A man named Clairvius Narcisse claimed that, 20 years before, he had been poisoned by a Bokor. He fell into a trance and was presumed dead, and buried. (Because of the heat and lack of embalming, Haitian burials take place within 24 hours of death, often in as little as 12.)

Clairvius awoke in his coffin, was dug up and given a drug which made him confused and suggestible, then taken to a sugar plantation and put to work. He worked on the plantation for two years, then came back to himself somewhat and escaped, along with other workers who had been treated similarly. Still disoriented and far from home, he wandered as a homeless beggar for 18 years, before stumbling back to his home village, where he recognized his sister.

The case was investigated by several Americans, who suggested that a neurotoxin created from a local toad was the original drug which put Clairvius into his coma. Then a plant extract called datura might have been used to keep him compliant. What did the plantation owners have to gain? Free labor. All it cost was 20 years of a human life.

At first I wondered how the African slaves, recently come to the islands, could have knowledge of these drugs. However, more careful reading reminded me that they were confined with, and learned from the last of the Native islanders. The native population had studied local animals and plants for centuries, and taught their skills to the newcomers.

Whether raised by magical or mundane means, slaves feared being made into Zombies. For this reason they buried their dead as close to the homes of the living as possible, or barring that, at a crossroads (symbol of the meeting place or life and death) or even in the middle of a street, where traffic could be assumed to prevent grave-robbing.

Europeans were fascinated, and more than a little afraid of the African magic. In places like New Orleans, where people of color became free, Vodou became a bit of a tourist attraction. But in Haiti, it remained a slave religion, heathen and dangerous.

Writers and film makers took advantage of this exotic legacy. Many Americans were first introduced to Zombie in the 1932 film The White Zombie, featuring Bela Lugosi as the evil Zombi-making magician. Quickly cobbled together after the success of Dracula, the movie featured an over-the-top plot and bad acting.

Furthermore, it suffered from the fact that classical Zombies aren't very frightening. After all, they are workers who do what they are told. Creepy? Oh, yes. Creepy as anything. But not very scary. It wasn't until 1968, and Night of the Living Dead Zombies became scary. But the frights are entirely invented. Classic Vodou Zombies don't eat people.

Next week - Voodoo Dolls

Published on January 12, 2015 16:52

January 5, 2015

Voodoo in the Caribbean

One of the things the Caribbean is famous for is Voodoo – Vodou in the preferred spelling of modern practitioners. The origin of dark magic, curses and walking dead, vodou has been used to spice up a variety of pirate movies and novels, most recently in Pirates of the Caribbean 4 – On Stranger Tides.

But the truth is, perhaps even stranger. Vodou is a modern religion, and a religion of recent origin. It grew out of the slavery of Africans in the 17th and 18th century. In short this ancient religion is very modern. It’s roots are in oppression, and it has been a unifying force for the various underclasses of the islands.

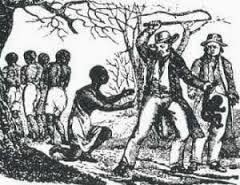

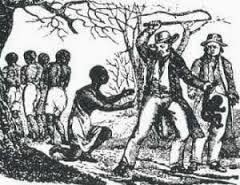

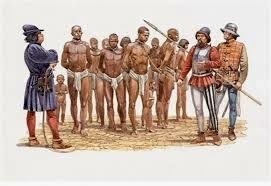

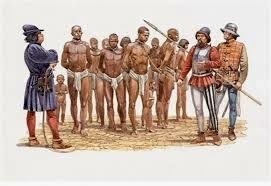

The primary “flavors” of Vodou are Haitian, Jamaican, and New Orleans. We will be discussing primarily the religion of Jamaica and Haiti, for the New Orleans religion is substantially different.When the planters of the islands bought slaves, they made an effort to buy Africans from a variety of different tribes, cultures and languages. Their reasoning was simple. If the slaves did not share a common language or culture, it would be much harder for them to rise against their oppressors. The island planters, being more isolated from Europe and from other Europeans, felt especially vulnerable.

The slaves had every reason to try escape or the overthrow the masters. Working on a sugar plantation was a death sentence. In the early days, slaves’ lives less than three years on average, and living conditions never improved much. Yet the horrible living conditions also provided an excellent reason to band together. Soon the slaves communicated in languages based off the languages of their overseers (English on Jamaica, French in Haiti) flavored with words from their own many languages.

They also began to meld their religions.

While many, many tribes were represent among the slaves, their religions often held common themes. Similar deities melded together. Folk traditions grew together.

During this time religion and medicine with interlinked. Europeans still attributed sickness to witchcraft, in addition to such things as “bad air” sin, and having too much blood. The emerging Vodou cults attributed sickness to the attentions of wandering ghosts, or such things as having a persimmon tree too close to the house.

The African healers also met and learned from the last surviving members of the Native population, discovering how to use local plants and materials to create effective medicines. When the medicines did not work, these skilled healers used “spirit powers” to defeat the attacking ghosts and encourage their patients to get well.

Was it the placebo effect? Was it magic? We may never truly know, but these healers and religious leaders won the hearts of the slaves, and began the creation of an underground civilization that made the situation almost bearable.

Although Haitian Vodou agrees that there is only one Supreme Being, it recognizes many powerful spirit “deities” as well. These are the loa (or lwa) and are roughly analogous to the Catholic saints. They each have their areas of power and protection, accept offerings and prayers, and intercede on behalf of their followers.

Of course, all of this was done in complete secrecy. Slaves were required to become Christians, at least officially. In Haiti this mean being baptized as Catholic. However, one the baptism was preformed, the overseers were only concerned that an outward appearance of Christianity be upheld.

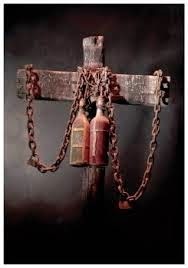

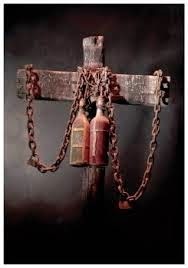

Vodou made use of the cross, but found different meaning in it. For them, it was the sign of the crossroads, the place where life and death meet. Often crosses were decorated with rum bottles, sign of joy, and chains, sign of the painful nature of a live without freedom.

The Bokor, or priest/priestess of the lwa, disguised the lwa as Catholic saints. For instance, Damballa, the spirit master who created the waters and the earth by shedding his skin like a serpent is often represented by St. Patrick, who drove the snakes out of Ireland.

Much of the work of the Bokors was spiritual healing. They called upon the lwa and made offering to them, gave patients and petitioners spiritual duties, and created alters and statues.

To the Western eye, these figures, along with their alters, appeared to be visions from hell. Several of the lwa bore snake aspects, so the representation of serpents was common. In order to show power, figures were often decorated with bull’s horns, giving them a devilish appearance. The colors of red and black appeared often. And, since Vodou incorporates aspects of ancestor worship, human skulls are sometimes used in religious art.

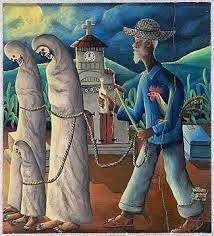

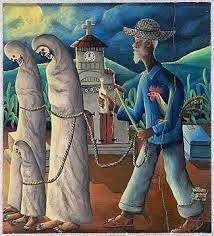

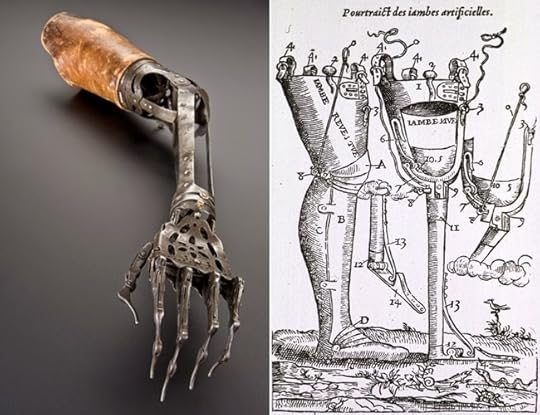

Vodou was a religion of the persecuted. The slaves rose in rebellion, were violently put down and tortured in punishment, and rebelled again. Their religion, and their religious leaders, supported them.Some of the images became horrible. They had always looked crude, being the work of poor people who could not afford fine materials. But now they showed spirits who had suffered along with their worshipers. Protective spirts who had fought hard for the people might be shown missing hands, arms, legs, feet. Eyes were missing. The statues bore the chains of servitude.

And yet the makers of these strange, powerful objects took one further step, which I find quite indicative of peaceful nature of the religion. They bound these frightful figures. The Bokor bindings were of rope. While chains showed strength to endure under oppression, ropes were a poor man’s binding. These were designed to hold back the destructive power until it was needed.

Next week... Zombies!

But the truth is, perhaps even stranger. Vodou is a modern religion, and a religion of recent origin. It grew out of the slavery of Africans in the 17th and 18th century. In short this ancient religion is very modern. It’s roots are in oppression, and it has been a unifying force for the various underclasses of the islands.

The primary “flavors” of Vodou are Haitian, Jamaican, and New Orleans. We will be discussing primarily the religion of Jamaica and Haiti, for the New Orleans religion is substantially different.When the planters of the islands bought slaves, they made an effort to buy Africans from a variety of different tribes, cultures and languages. Their reasoning was simple. If the slaves did not share a common language or culture, it would be much harder for them to rise against their oppressors. The island planters, being more isolated from Europe and from other Europeans, felt especially vulnerable.

The slaves had every reason to try escape or the overthrow the masters. Working on a sugar plantation was a death sentence. In the early days, slaves’ lives less than three years on average, and living conditions never improved much. Yet the horrible living conditions also provided an excellent reason to band together. Soon the slaves communicated in languages based off the languages of their overseers (English on Jamaica, French in Haiti) flavored with words from their own many languages.

They also began to meld their religions.

While many, many tribes were represent among the slaves, their religions often held common themes. Similar deities melded together. Folk traditions grew together.

During this time religion and medicine with interlinked. Europeans still attributed sickness to witchcraft, in addition to such things as “bad air” sin, and having too much blood. The emerging Vodou cults attributed sickness to the attentions of wandering ghosts, or such things as having a persimmon tree too close to the house.

The African healers also met and learned from the last surviving members of the Native population, discovering how to use local plants and materials to create effective medicines. When the medicines did not work, these skilled healers used “spirit powers” to defeat the attacking ghosts and encourage their patients to get well.

Was it the placebo effect? Was it magic? We may never truly know, but these healers and religious leaders won the hearts of the slaves, and began the creation of an underground civilization that made the situation almost bearable.

Although Haitian Vodou agrees that there is only one Supreme Being, it recognizes many powerful spirit “deities” as well. These are the loa (or lwa) and are roughly analogous to the Catholic saints. They each have their areas of power and protection, accept offerings and prayers, and intercede on behalf of their followers.

Of course, all of this was done in complete secrecy. Slaves were required to become Christians, at least officially. In Haiti this mean being baptized as Catholic. However, one the baptism was preformed, the overseers were only concerned that an outward appearance of Christianity be upheld.

Vodou made use of the cross, but found different meaning in it. For them, it was the sign of the crossroads, the place where life and death meet. Often crosses were decorated with rum bottles, sign of joy, and chains, sign of the painful nature of a live without freedom.

The Bokor, or priest/priestess of the lwa, disguised the lwa as Catholic saints. For instance, Damballa, the spirit master who created the waters and the earth by shedding his skin like a serpent is often represented by St. Patrick, who drove the snakes out of Ireland.

Much of the work of the Bokors was spiritual healing. They called upon the lwa and made offering to them, gave patients and petitioners spiritual duties, and created alters and statues.

To the Western eye, these figures, along with their alters, appeared to be visions from hell. Several of the lwa bore snake aspects, so the representation of serpents was common. In order to show power, figures were often decorated with bull’s horns, giving them a devilish appearance. The colors of red and black appeared often. And, since Vodou incorporates aspects of ancestor worship, human skulls are sometimes used in religious art.

Vodou was a religion of the persecuted. The slaves rose in rebellion, were violently put down and tortured in punishment, and rebelled again. Their religion, and their religious leaders, supported them.Some of the images became horrible. They had always looked crude, being the work of poor people who could not afford fine materials. But now they showed spirits who had suffered along with their worshipers. Protective spirts who had fought hard for the people might be shown missing hands, arms, legs, feet. Eyes were missing. The statues bore the chains of servitude.

And yet the makers of these strange, powerful objects took one further step, which I find quite indicative of peaceful nature of the religion. They bound these frightful figures. The Bokor bindings were of rope. While chains showed strength to endure under oppression, ropes were a poor man’s binding. These were designed to hold back the destructive power until it was needed.

Next week... Zombies!

Published on January 05, 2015 19:43

December 29, 2014

From Jean LaFoote to Captain Morgan - Pirates in Commercials

When people ask me, “Why pirates?” I almost always reply Johnny Depp. He was, after all, the star who sent me into my grown-up pirate obsession. But he wasn’t my FIRST pirate. The first pirate I remember came on a TV commercial, many, many years before.

His name was Jean LaFoot, and he was the bad guy in the Cap’n Crunch TV commercials. Originally voiced by Bill Scott, LaFoot, the barefoot pirate, was constantly trying to steal Cap’n Cruch’s cereal. When not doing that, he was attacking the good captain, or the kids who followed him, or trying to sink the good ship Guppy. When not in commercials, he co-starred in a series of mini comic books that came inside the cereal boxes. His popularity was large enough that, when a spin-off cereal was invented, he was made the mascot for it. See a commercial here.

Although I was very young at the time, something about the barefoot pirate stuck with me. I remember asking my mom if he was a real person. He wasn’t of course, but many years later, I found out that his name had been based on Jean Lefitte, an early 19th century French pirate who operated out of New Orleans, and is most famous for supporting the Americans during the War of 1812.

Of course, most pirates in commercials are more stereotypes and less history. This very old ad for FedEx limits the pirate down to a parrot, a hook and an eyepatch. The messageis simple… If this guy can run the FedEx software, you can too.

Other commercials evoke the yearning for freedom and the deep longing of the imagination that makes pirates so popular. This adis for Clorox, a cleaning product that is most definitely not associated with pirates or the piratical lifestyle at all.

Pirates have the ability to be cute. Who makes a better spokesperson for eyedrops than an eyeball? And what gives an eyeball personality? Well, if it’s dressing up as a pirate (including the eyepatch) that’s pretty cute. And, more recently, the hook hand of a pirate has figured in another "eye ad".

Sometimes the pirate theme just gets out of hand. This Bud Light commercial is just confusing... If you drink our beer, your living room will be transformed into a pirate lair, and a pirate ship will appear in your backyard? One suspects that the audience is already supposed to be drunk to cheer for this ad. There is the disclaimer that the winner of this strange contest has a wife who agrees to the make-over of her house (including the cheerleaders on the boat?) It's fun during the tie the ad is running, but not much an incentive to drink this particular beer.

Another of the most distinctive pirate commercials in recent memory is the one for FreeCreditReport .com. It’s interesting that the Free Credit Report offer as itself been identified as a scam. The “free” repost they were offering came only if the user signed up for a service that cost, and truly free credit scores are available by other means. But the series of ads produced, leading off with the pirate-themed commercial offered here, were distinctive and very fun to watch.

Of course, the theme restaurant alluded to here is Long John Silver’s. I wasn’t going to list any ads that were actually advertising pirates… No pirate movies or pirate toys, etc. But some people may not realize that the fast-food seafood franchise was names after Robert Lewis Stevenson’s famous pirate character. It was okay, because Stevenson had been dead for over 100 years, and any copyright had long since expired. Older commercials – this onedates from 1978, played a lot more heavily on the pirate theme than more modern ones. But the chain is still faithful to its pirate roots. It offers free food to anyone dressed like a pirate on September 19th (talk like a pirate day).

And last, of course, are the ads for Captain Morgan rum. The rum is names after a real 17th century buccaneer, who really wore a red coat, had facial hair much like the guy pictured on the bottle, and sailed a ship called the Satisfaction.

The earliest commercial I could find references pirate comradery. A group of barflies come to the aid of a friend who is busted by his girlfriend for not attending her cousin’s wedding. There’s not a lot of pirate reference until the end.

In later commercials the brand recognized the true value of its mascot and began to develop “The Captain” as a character. A string of ads chronicled a series of adventures in a world that does in fact look a lot like the Caribbean that the real Morgan moved around in. Strung together, they make a nice few minute’s entertainment.

What the rum company probably doesn’t want you to know is that, after a lifetime of adventure, the historic Morgan died from liver failure due to his heavy drinking. But, hey, while pirates are great at advertising food, drink, adventure, staying up late and general fun, I doubt we’ll ever see a pirate advertising an old-age home.

His name was Jean LaFoot, and he was the bad guy in the Cap’n Crunch TV commercials. Originally voiced by Bill Scott, LaFoot, the barefoot pirate, was constantly trying to steal Cap’n Cruch’s cereal. When not doing that, he was attacking the good captain, or the kids who followed him, or trying to sink the good ship Guppy. When not in commercials, he co-starred in a series of mini comic books that came inside the cereal boxes. His popularity was large enough that, when a spin-off cereal was invented, he was made the mascot for it. See a commercial here.

Although I was very young at the time, something about the barefoot pirate stuck with me. I remember asking my mom if he was a real person. He wasn’t of course, but many years later, I found out that his name had been based on Jean Lefitte, an early 19th century French pirate who operated out of New Orleans, and is most famous for supporting the Americans during the War of 1812.

Of course, most pirates in commercials are more stereotypes and less history. This very old ad for FedEx limits the pirate down to a parrot, a hook and an eyepatch. The messageis simple… If this guy can run the FedEx software, you can too.

Other commercials evoke the yearning for freedom and the deep longing of the imagination that makes pirates so popular. This adis for Clorox, a cleaning product that is most definitely not associated with pirates or the piratical lifestyle at all.

Pirates have the ability to be cute. Who makes a better spokesperson for eyedrops than an eyeball? And what gives an eyeball personality? Well, if it’s dressing up as a pirate (including the eyepatch) that’s pretty cute. And, more recently, the hook hand of a pirate has figured in another "eye ad".

Sometimes the pirate theme just gets out of hand. This Bud Light commercial is just confusing... If you drink our beer, your living room will be transformed into a pirate lair, and a pirate ship will appear in your backyard? One suspects that the audience is already supposed to be drunk to cheer for this ad. There is the disclaimer that the winner of this strange contest has a wife who agrees to the make-over of her house (including the cheerleaders on the boat?) It's fun during the tie the ad is running, but not much an incentive to drink this particular beer.

Another of the most distinctive pirate commercials in recent memory is the one for FreeCreditReport .com. It’s interesting that the Free Credit Report offer as itself been identified as a scam. The “free” repost they were offering came only if the user signed up for a service that cost, and truly free credit scores are available by other means. But the series of ads produced, leading off with the pirate-themed commercial offered here, were distinctive and very fun to watch.

Of course, the theme restaurant alluded to here is Long John Silver’s. I wasn’t going to list any ads that were actually advertising pirates… No pirate movies or pirate toys, etc. But some people may not realize that the fast-food seafood franchise was names after Robert Lewis Stevenson’s famous pirate character. It was okay, because Stevenson had been dead for over 100 years, and any copyright had long since expired. Older commercials – this onedates from 1978, played a lot more heavily on the pirate theme than more modern ones. But the chain is still faithful to its pirate roots. It offers free food to anyone dressed like a pirate on September 19th (talk like a pirate day).

And last, of course, are the ads for Captain Morgan rum. The rum is names after a real 17th century buccaneer, who really wore a red coat, had facial hair much like the guy pictured on the bottle, and sailed a ship called the Satisfaction.

The earliest commercial I could find references pirate comradery. A group of barflies come to the aid of a friend who is busted by his girlfriend for not attending her cousin’s wedding. There’s not a lot of pirate reference until the end.

In later commercials the brand recognized the true value of its mascot and began to develop “The Captain” as a character. A string of ads chronicled a series of adventures in a world that does in fact look a lot like the Caribbean that the real Morgan moved around in. Strung together, they make a nice few minute’s entertainment.

What the rum company probably doesn’t want you to know is that, after a lifetime of adventure, the historic Morgan died from liver failure due to his heavy drinking. But, hey, while pirates are great at advertising food, drink, adventure, staying up late and general fun, I doubt we’ll ever see a pirate advertising an old-age home.

Published on December 29, 2014 20:11

December 22, 2014

Pirate Santa

Christmas is nearly upon us; it’s time for eggnog, presents and… Pirates?

Well, yes. As a matter of fact, Santa dressed as a pirate, or pirates dressed as Santa, is a “thing”. And it make sense, after all. Both pirate captains and St. Nick lead rag-tag bands of outcasts. (When was the last time you saw an elf in polite society?) And they both have a history of re-distributing wealth.

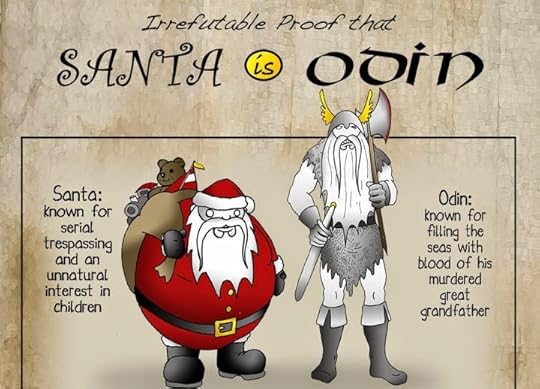

One reason it’s so easy to link the two is that Santa has a backstory that’s s lot more fierce than his current incarnations. The gift-bringer was once known to bring coal (representing the fires of hell) to kids who weren’t good enough. And before that, he was linked to Odin, the Norse father-god who wandered the world and occasionally meted out justice, in the forms of rewards or punishment.

It’s generally believed, even by folks who don’t “Believe” in Santa, that the man in the red suit is a powerful force of nature. In movies like “Rise of the Guardians” he’s a Russian-accented powerhouse, leading the other guardians of childhood to protect the world. In “The Nightmare Before Christmas” Jack Skellington nearly wrecks the holiday, but when Santa is set free at the last minute, he calmly states that he has the power to set everything right by dawn.

So Santa, like a pirate captain, has impressive power, and the ability to travel. He might be carrying anything from gold to coal to the kind of odds and ends that might be accumulating in the hold of a pirate ship – or Santa’s bag of holding.

Both characters are often jolly. And even though Santa is gifted with glasses of milk on Christmas Eve, no one has ever claimed that he doesn’t enjoy a mixed drink after he’s finished driving the sleigh.

Santa’s long red coat with the white fur cuffs easily translated into an 18th century pirate coat, and red is a color that’s been associated with pirates ever since Captain Morgan donned his best red silk coat while recruiting a privateer navy to fight the Spanish.

Santa’s boots look quite a bit like pirate-style footwear. And various other details – his beard, reminiscent of Blackbeard, his sack full of loot, his wide-buckled black belt – all add to the likeness. Some artists have added a hook hand made from a candy cane, and it blends right in,

It’s even easy to see Santa in the tropics. After all, he needs some kind of vacation after the big night. Santa as a pirate, or a pirate as Santa, is an image that goes back decades, and has been memorialized in nutcrackers, Christmas ornaments, paintings, and photos.

Probably the ultimate link is the children's book, "Pirate Santa" featuring Cap'n Slappy, one of the gentlemen who brought us Talk Like a Pirate Day. The story is one dear to a pirate's heart, about how Slappy, Santa's cousin, sets out to bring Christmas cheer to kids who were a little too - um - nonconforming, to make Santa's "nice" list.

The book makes a grand Christmas gift for a child, and since it's available by download, it can still be purchaed in time for the holiday.

Or, for grownups, pick up a copy of my own novels, Gentlemen and Fortune and Bloody Seas, the tale of my redheaded female pirate captain and her adventures in the man's world of piracy.

So I’ll leave you all a little early tonight, as I go off to wrap my own loot. Yo Ho Ho Ho and a Merry Christmas to all!

Well, yes. As a matter of fact, Santa dressed as a pirate, or pirates dressed as Santa, is a “thing”. And it make sense, after all. Both pirate captains and St. Nick lead rag-tag bands of outcasts. (When was the last time you saw an elf in polite society?) And they both have a history of re-distributing wealth.

One reason it’s so easy to link the two is that Santa has a backstory that’s s lot more fierce than his current incarnations. The gift-bringer was once known to bring coal (representing the fires of hell) to kids who weren’t good enough. And before that, he was linked to Odin, the Norse father-god who wandered the world and occasionally meted out justice, in the forms of rewards or punishment.

It’s generally believed, even by folks who don’t “Believe” in Santa, that the man in the red suit is a powerful force of nature. In movies like “Rise of the Guardians” he’s a Russian-accented powerhouse, leading the other guardians of childhood to protect the world. In “The Nightmare Before Christmas” Jack Skellington nearly wrecks the holiday, but when Santa is set free at the last minute, he calmly states that he has the power to set everything right by dawn.

So Santa, like a pirate captain, has impressive power, and the ability to travel. He might be carrying anything from gold to coal to the kind of odds and ends that might be accumulating in the hold of a pirate ship – or Santa’s bag of holding.

Both characters are often jolly. And even though Santa is gifted with glasses of milk on Christmas Eve, no one has ever claimed that he doesn’t enjoy a mixed drink after he’s finished driving the sleigh.

Santa’s long red coat with the white fur cuffs easily translated into an 18th century pirate coat, and red is a color that’s been associated with pirates ever since Captain Morgan donned his best red silk coat while recruiting a privateer navy to fight the Spanish.

Santa’s boots look quite a bit like pirate-style footwear. And various other details – his beard, reminiscent of Blackbeard, his sack full of loot, his wide-buckled black belt – all add to the likeness. Some artists have added a hook hand made from a candy cane, and it blends right in,

It’s even easy to see Santa in the tropics. After all, he needs some kind of vacation after the big night. Santa as a pirate, or a pirate as Santa, is an image that goes back decades, and has been memorialized in nutcrackers, Christmas ornaments, paintings, and photos.

Probably the ultimate link is the children's book, "Pirate Santa" featuring Cap'n Slappy, one of the gentlemen who brought us Talk Like a Pirate Day. The story is one dear to a pirate's heart, about how Slappy, Santa's cousin, sets out to bring Christmas cheer to kids who were a little too - um - nonconforming, to make Santa's "nice" list.

The book makes a grand Christmas gift for a child, and since it's available by download, it can still be purchaed in time for the holiday.

Or, for grownups, pick up a copy of my own novels, Gentlemen and Fortune and Bloody Seas, the tale of my redheaded female pirate captain and her adventures in the man's world of piracy.

So I’ll leave you all a little early tonight, as I go off to wrap my own loot. Yo Ho Ho Ho and a Merry Christmas to all!

Published on December 22, 2014 20:00

December 15, 2014

Roaring Dan of the Wanderer

Roaring Dan’s Rum was named after the captain of the Wanderer, a rough, tough sailor, who made his fame by wrecking ships and stealing their cargo. He once sank the ship of a competitor with all hands aboard. Roaring Dan Seavey liked to sneak into ports and rob vessels that were tied up for the night. He also transported women for nefarious purposes, and was an important player in the venison poaching trade.

Venison?

Yup. Because Roaring Dan was born in 1865, and did most of his pirating in the 20th century. In the Midwest. The Great Lakes to be specific.

Like a lot of pirates, Dan went to sea young, joining the navy at age 13. He married and had 2 children, and settled in Wisconsin, where he fished, farmed and owned a saloon. But like a lot of men who had been pirates before him, he wanted more.

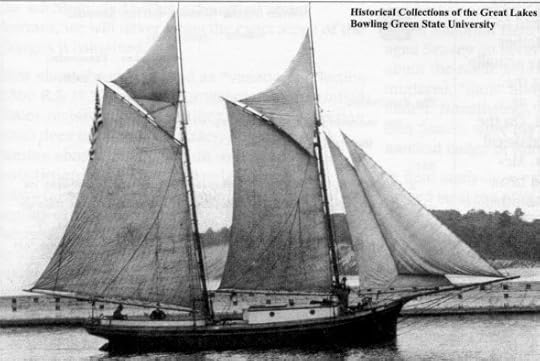

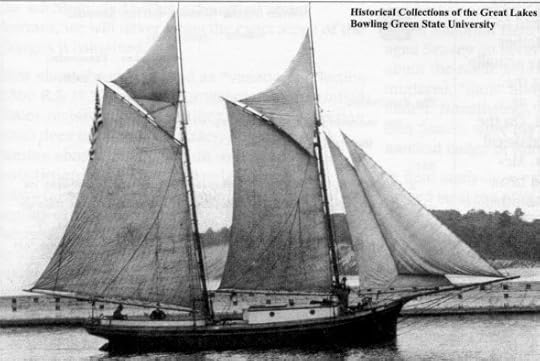

Dan left his family in 1900 to head up to the Klondike in Alaska, joining thousands of others in a gold rush. But like a lot of others, he lost everything instead. Finally he fled south to Minnesota and acquired (we don’t know how) an old schooner, which he named the Wanderer.

One of Dan’s signature moves was to alter lights that marked the shipping lanes. The practice was called “moon cussing” by the locals. Once a misguided ship had run aground, Dan would sail in and loot the wreck.

He also made so much money poaching venison on private land that the Booth Fisheries tried to beat him at his own game. Dan hunted down one of their ships, attacked it with a cannon, and sank it.

But his most famous exploit was capturing the Nellie Johnson. The adventure did not involve cannon, but rum. Dan showed up at the Grand Haven, Michigan dock where the schooner lay at anchor with friendly look and a great deal of liquor. He shared this with the Nellie Johnson’s crew. Once they were all drunk, he threw them overboard and sailed for Chicago, where he sold the cargo.

Pursued and arrested, Dan was eventually arrested for piracy and dragged back to Chicago in chains. Conveniently, the owner of the Nellie Johnson never appeared to testify. Dan got away with it, and claimed for the rest of his life that he’d won the ship in a card game.

Like a lot of pirates, he eventually retired and became a law enforcer. Since the days of the privateers were long over, this took the form of a job with the US Marshall’s Service, where he worked to curb poaching, smuggling, and piracy on the great lakes.

Though the Wanderer was destroyed by fire in 1918, Dan stayed on the water, now using the kind of motor launch favored by the very smugglers he was chasing. When Prohibition made the sale of alcohol illegal in the US, he may or may not have smuggled liquor in from Canada.

In the kinder, gentler 20th century, it was possible for a pirate to actually retire. Dan stopped his activities in the late 1920’s. He died in a Wisconsin nursing home in 1949, at the age of 84.

We don’t think of pirates in the peaceful Midwest, but piracy is a worldwide practice. In fact, the Great Lakes have seen as much piracy as any other body of water. Rum running, venison poaching, illegal clear-cutting of timer on private land, these were the work of Great Lakes pirates, and many of them were colorful characters like Roaring Dan’s Seavey.

So when the cold closes in and the snowflakes begin to fly, raise a glass of rum to the pirates of the Midwest and remember that piracy is never too far away.

Venison?

Yup. Because Roaring Dan was born in 1865, and did most of his pirating in the 20th century. In the Midwest. The Great Lakes to be specific.

Like a lot of pirates, Dan went to sea young, joining the navy at age 13. He married and had 2 children, and settled in Wisconsin, where he fished, farmed and owned a saloon. But like a lot of men who had been pirates before him, he wanted more.

Dan left his family in 1900 to head up to the Klondike in Alaska, joining thousands of others in a gold rush. But like a lot of others, he lost everything instead. Finally he fled south to Minnesota and acquired (we don’t know how) an old schooner, which he named the Wanderer.

One of Dan’s signature moves was to alter lights that marked the shipping lanes. The practice was called “moon cussing” by the locals. Once a misguided ship had run aground, Dan would sail in and loot the wreck.

He also made so much money poaching venison on private land that the Booth Fisheries tried to beat him at his own game. Dan hunted down one of their ships, attacked it with a cannon, and sank it.

But his most famous exploit was capturing the Nellie Johnson. The adventure did not involve cannon, but rum. Dan showed up at the Grand Haven, Michigan dock where the schooner lay at anchor with friendly look and a great deal of liquor. He shared this with the Nellie Johnson’s crew. Once they were all drunk, he threw them overboard and sailed for Chicago, where he sold the cargo.

Pursued and arrested, Dan was eventually arrested for piracy and dragged back to Chicago in chains. Conveniently, the owner of the Nellie Johnson never appeared to testify. Dan got away with it, and claimed for the rest of his life that he’d won the ship in a card game.

Like a lot of pirates, he eventually retired and became a law enforcer. Since the days of the privateers were long over, this took the form of a job with the US Marshall’s Service, where he worked to curb poaching, smuggling, and piracy on the great lakes.

Though the Wanderer was destroyed by fire in 1918, Dan stayed on the water, now using the kind of motor launch favored by the very smugglers he was chasing. When Prohibition made the sale of alcohol illegal in the US, he may or may not have smuggled liquor in from Canada.

In the kinder, gentler 20th century, it was possible for a pirate to actually retire. Dan stopped his activities in the late 1920’s. He died in a Wisconsin nursing home in 1949, at the age of 84.

We don’t think of pirates in the peaceful Midwest, but piracy is a worldwide practice. In fact, the Great Lakes have seen as much piracy as any other body of water. Rum running, venison poaching, illegal clear-cutting of timer on private land, these were the work of Great Lakes pirates, and many of them were colorful characters like Roaring Dan’s Seavey.

So when the cold closes in and the snowflakes begin to fly, raise a glass of rum to the pirates of the Midwest and remember that piracy is never too far away.

Published on December 15, 2014 18:59

December 8, 2014

Pirate Card Games

Once in a while when I read pirate fiction, the pirates will be playing poker. This drives me absolutely mad, since the card game poker wasn’t invented until about 1850 (roughly 150 years after the Golden Age). It grew up along the Mississippi river boats, and then spread to the California gold fiends. It is a product of the American frontier.

In the early Caribbean, card games were certainly popular, but they were games that had originated in Europe.

The cards themselves were very much like the ones we use today. A deck held 52 cards, with the same four suits as our own, and the number 1-10 in each, plus the 3 face cards of Jack Queen and King in each suit.

What was not the same was the look of the cards. No one had yet thought of designing the cards so that they looked the same with either end up. The royal figures had heads and feet, and the “pip” cards likewise had only one “right” way up. The backs of the cards were blank, and the edges were not rounded in the manner of modern cards. Also, they were printed on plain cardboard, without the waterproof coating we expect now. Cards were also much harder to come by. It’s easy to imagine them being dog-eared and dirty.

A lonely pirate might pass the time by playing Patience, which was the word used at the time for the game we call Solitaire. The version at the time was the one most likely to be found today on a computer, an arrangement of cards that starts out with seven piles of face-down cards, and ends with 4 piles, face up, each containing only one suit and arranged from ace to king.

The classic English game was Cribbage, in almost exactly the same form it is played today. It was descended from an even older game called “Noddy”. Cribbage boards, the scoring mechanism for the game, have been found in the wrecks of pirate ships. Today cribbage is the “official” game of the American submarine service.

Seafaring novels set during the Napoleonic wars (1799-1815) often mention the game Whist, a game similar to modern-day Bridge. But this game is believed to have come into being at about 1728 – too late for our period.

France, a major player in the Caribbean, was also a major producer of playing cards. Produced a number of famous card games, including Piquet (pronounced P.K.).

Piquet was developed at about the year 1500, possibly from an even older Spanish game. It uses a deck of 32 cards, from 7-King in each of 4 suits, plus the Aces, which are high. It is a game for 2 players, each of whom receives 12 cards, and can discard and re-draw to improve their hand. The game then progresses something like Bridge, with combinations being made to score points by "taking tricks."

This is a scientific game. It’s possible to figure out exactly what cards your opponent holds by noting your own cards and your opponents’ discards. Possibly because this led to over-confidence, betting sometimes reached fantastical heights. French nobles sometimes wagered whole estates on a single game. Eventually the king of France banned Piquet, though play did not actually die out for another two centuries.

This may also have been one of the reasons that pirate ships banned card games except on shore.

The spiritual, if not quite factual, ancestor of all these games was the Spanish Ombre. A complicated game, it was, like the others, a trick-taking game similar to Bridge. Its name is derived from the official statement that one had won the game, similar to the exclamation “Check!” in chess. It was actually the Spanish word “hombre,” meaning “I’m the man!”

Of course, there were dozens of other card games. The number of ways that a single deck of cards can be dealt, stacked, combined, spread and recombined in almost limitless variations. Where today we have a variety of card types (Uno, Go Fish, Old Maid) , in the early 1700’s there was only one basically type of was only one type of deck. The variations were wide indeed.

While many card games required “tricks” to be acquired, the Irish game Maw (sometimes rhymed with cow) was a game of discarding. The first person to lay all his cards on the table was the winner. It was, ideally, a five person game.

Maw had one other interesting detail. It was against the rules to tell the rules to any other player. The official statement was, “I can only tell you the first rule, and that’s this one.” After that, players needed to figure it out for themselves. The appearance of certain cards reversed the order of play, caused play to skip a player, changed the cards that were “high” or made other changes. If a new player didn’t figure it out he played a penalty.

So a tavern full of pirates playing cards would have been a vibrant and loud affair. The cards would slap, the cribbage board would clack, arguments would break out over the rules of the various games, and every once in while someone would clash his tankard to the table top and shout, “I’m the man!”

In the early Caribbean, card games were certainly popular, but they were games that had originated in Europe.

The cards themselves were very much like the ones we use today. A deck held 52 cards, with the same four suits as our own, and the number 1-10 in each, plus the 3 face cards of Jack Queen and King in each suit.

What was not the same was the look of the cards. No one had yet thought of designing the cards so that they looked the same with either end up. The royal figures had heads and feet, and the “pip” cards likewise had only one “right” way up. The backs of the cards were blank, and the edges were not rounded in the manner of modern cards. Also, they were printed on plain cardboard, without the waterproof coating we expect now. Cards were also much harder to come by. It’s easy to imagine them being dog-eared and dirty.

A lonely pirate might pass the time by playing Patience, which was the word used at the time for the game we call Solitaire. The version at the time was the one most likely to be found today on a computer, an arrangement of cards that starts out with seven piles of face-down cards, and ends with 4 piles, face up, each containing only one suit and arranged from ace to king.

The classic English game was Cribbage, in almost exactly the same form it is played today. It was descended from an even older game called “Noddy”. Cribbage boards, the scoring mechanism for the game, have been found in the wrecks of pirate ships. Today cribbage is the “official” game of the American submarine service.

Seafaring novels set during the Napoleonic wars (1799-1815) often mention the game Whist, a game similar to modern-day Bridge. But this game is believed to have come into being at about 1728 – too late for our period.

France, a major player in the Caribbean, was also a major producer of playing cards. Produced a number of famous card games, including Piquet (pronounced P.K.).

Piquet was developed at about the year 1500, possibly from an even older Spanish game. It uses a deck of 32 cards, from 7-King in each of 4 suits, plus the Aces, which are high. It is a game for 2 players, each of whom receives 12 cards, and can discard and re-draw to improve their hand. The game then progresses something like Bridge, with combinations being made to score points by "taking tricks."

This is a scientific game. It’s possible to figure out exactly what cards your opponent holds by noting your own cards and your opponents’ discards. Possibly because this led to over-confidence, betting sometimes reached fantastical heights. French nobles sometimes wagered whole estates on a single game. Eventually the king of France banned Piquet, though play did not actually die out for another two centuries.

This may also have been one of the reasons that pirate ships banned card games except on shore.

The spiritual, if not quite factual, ancestor of all these games was the Spanish Ombre. A complicated game, it was, like the others, a trick-taking game similar to Bridge. Its name is derived from the official statement that one had won the game, similar to the exclamation “Check!” in chess. It was actually the Spanish word “hombre,” meaning “I’m the man!”

Of course, there were dozens of other card games. The number of ways that a single deck of cards can be dealt, stacked, combined, spread and recombined in almost limitless variations. Where today we have a variety of card types (Uno, Go Fish, Old Maid) , in the early 1700’s there was only one basically type of was only one type of deck. The variations were wide indeed.

While many card games required “tricks” to be acquired, the Irish game Maw (sometimes rhymed with cow) was a game of discarding. The first person to lay all his cards on the table was the winner. It was, ideally, a five person game.

Maw had one other interesting detail. It was against the rules to tell the rules to any other player. The official statement was, “I can only tell you the first rule, and that’s this one.” After that, players needed to figure it out for themselves. The appearance of certain cards reversed the order of play, caused play to skip a player, changed the cards that were “high” or made other changes. If a new player didn’t figure it out he played a penalty.

So a tavern full of pirates playing cards would have been a vibrant and loud affair. The cards would slap, the cribbage board would clack, arguments would break out over the rules of the various games, and every once in while someone would clash his tankard to the table top and shout, “I’m the man!”

Published on December 08, 2014 20:02

December 1, 2014

Hook Hands, Peg Legs and Eyepatches

It seems like whenever someone wants to create a pirate costume or drawing of a pirate, the fist thing they do (well, maybe after the tricorn hat and the parrot) is to add a patch, a pegleg or a hook. How come? What’s the big deal with these and pirates?

To begin with, all of these things were real in the 18th century. People really did have pegs ofr legs and hooks for hands, and wear patches over their eyes. And I’ve personally encountered people who think that this was some kind fashion statement, in the same way that people today wear tattoos, or decorative scarring, or practice extreme body modification.

They were not. In fact, these things were standard medicine at the time. They were, simply, the best way of helping disabled people to go on with life in a normal way.

Loss of limbs was much more common during this time, especially among sailors. Not only were men wounded in battle, but the everyday activity of the ship was dangerous (something we have trouble relating to in a world were OSHA regulations protect us). People tripped fell down hatches, or missed their grip and plunged from the high masts. Things dropped from the masts and landed on those below.

In an age before the invention of antibiotics any sort of wound could be dangerous. A broken bone – especially a compound fracture – often became infected. In order to save the patient’s life, the affected part would be amputated.

Any limb severely damaged would probably face the same fate. Remember, anesthetics had also not been invented yet, so any reconstructive surgery took place with the patient screaming and trying to get away. Reconstructive surgery was hardly more than a dream. Since a crushed hand, foot or leg could not be reconstructed, and was at great risk of infection, it was safest to simply remove it.

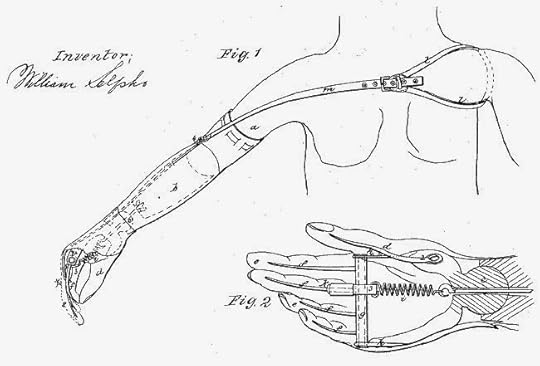

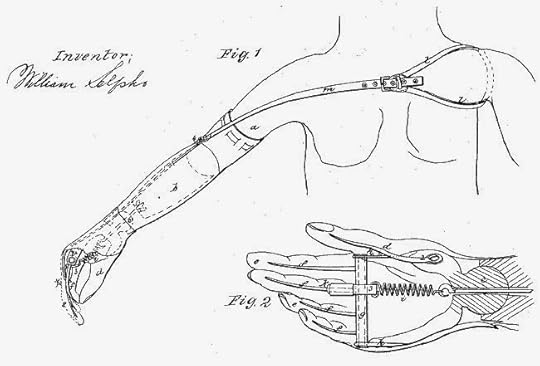

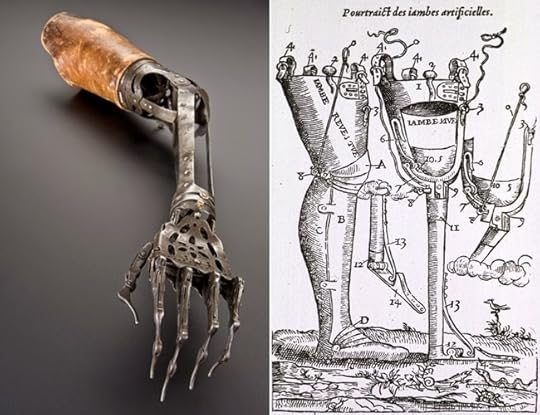

For the rich, skilled physicians and talented craftsmen teamed up to create the most workable and aesthetically pleasing results possible. During the 1600's it had been discovered that the stump of a severed limb could be sculpted during the amputation process to make it better adapted to receive a prosthesis.

In th4e case of a leg, the stump needed to be formed as much as possible into a cone, When walking on the stump, the weight would be dispersed over the surface of the leg, rather than concentrated on the end of the stump, which would be very painful.

Of course, this assumed a competent medic. Pirates most often recruited from among common sailors. Officers and skilled workers were harder to persuade to abandon everything for the sake of freedom. In the absence of a surgeon, the ship's carpenter (good at using saws) the cook (skilled at butchering animals) or even barber (practiced with knives) would be pressed into service. If worse came to worse, any brave man with an axe could try. A person badly enough injured to need an amputation was in danger of death anyway.

These results often yielded very unsatisfactory results. The most famous legless pirate - Long John Silver - didn't have a wooden leg. He used a crutch instead. One assumes that putting weight on the remnants of a botched amputation were too painful to stand.

Must have been pretty bad. Crutches of the time were simple wooden "T"s without even a hand grip. Actors who have played Silver remark on how painful these crutches are to use.

And this leads us to why amputations and pirates go together - Writers.

Robert Louis Stevenson created Long John, and gave him the missing leg to make him distinctive. Similarly, J.M. Barrie gave his pirate a hook hand and the name Hook to make him a memorable, frightening character. And when Chris Columbus wrote a screenplay about a group of kids looking for pirate treasure, and needed a pirate that could be positively identified by his remains, he created One Eyed Willy.

It's been suggested that the eye patch thing actually had a reason. Famously, the Mythbusters postulated that wearing an eye patch enabled attacking pirates to keep one eye acclimated to the dark, so they could run belowdecks on a merchant ship without being blinded by the change of dark to light. This is persuasive, except that every effort was made to keep the lower decks on a ship as brightly lit as possible. After all, people had to work down there.

Historically, there are no really famous pirates missing either legs or hands. Pirates who lost limbs in the course of their work were paid a benefit out of the ship's operating so they could retire comfortably. One pirate did have a disabled eye. French pirate Olivier Levasseur (aka The Buzzard) had an eye that had been damaged by a sword stroke, and wore a black silk patch later in life.But he wasn't famous for the patch, and pictures don't show it, choosing instead to show the dramatic scar.

So hook hands, peg legs, and eye patches are associated with pirates simply because they could be. And because some very good writers chose to make these kinds of disabilities a distinctive mark of their greatest creations. It worked. We associate disabilities with pirates.

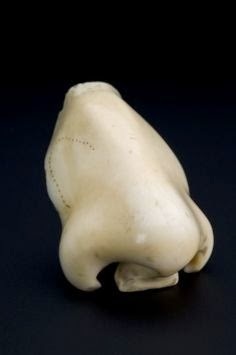

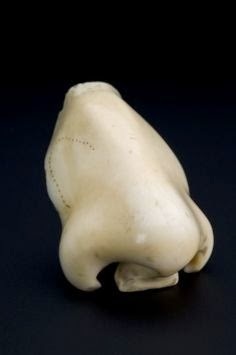

One other kind of prosthetic that was fairly common at the time was the prosthetic nose. People lost their noses - to frostbite, injury, and to disease. Syphilis, in its later stages, can cause skin lesions that ultimately cost the patient extremities like noses and ears.

My favorite is this ivory nose, although silver was also used by those who could afford it. Those who couldn't afford it wore a flap of leather to hide the disfigurement.

Anyone inspired to create a new pirate?

To begin with, all of these things were real in the 18th century. People really did have pegs ofr legs and hooks for hands, and wear patches over their eyes. And I’ve personally encountered people who think that this was some kind fashion statement, in the same way that people today wear tattoos, or decorative scarring, or practice extreme body modification.

They were not. In fact, these things were standard medicine at the time. They were, simply, the best way of helping disabled people to go on with life in a normal way.

Loss of limbs was much more common during this time, especially among sailors. Not only were men wounded in battle, but the everyday activity of the ship was dangerous (something we have trouble relating to in a world were OSHA regulations protect us). People tripped fell down hatches, or missed their grip and plunged from the high masts. Things dropped from the masts and landed on those below.

In an age before the invention of antibiotics any sort of wound could be dangerous. A broken bone – especially a compound fracture – often became infected. In order to save the patient’s life, the affected part would be amputated.

Any limb severely damaged would probably face the same fate. Remember, anesthetics had also not been invented yet, so any reconstructive surgery took place with the patient screaming and trying to get away. Reconstructive surgery was hardly more than a dream. Since a crushed hand, foot or leg could not be reconstructed, and was at great risk of infection, it was safest to simply remove it.

For the rich, skilled physicians and talented craftsmen teamed up to create the most workable and aesthetically pleasing results possible. During the 1600's it had been discovered that the stump of a severed limb could be sculpted during the amputation process to make it better adapted to receive a prosthesis.

In th4e case of a leg, the stump needed to be formed as much as possible into a cone, When walking on the stump, the weight would be dispersed over the surface of the leg, rather than concentrated on the end of the stump, which would be very painful.

Of course, this assumed a competent medic. Pirates most often recruited from among common sailors. Officers and skilled workers were harder to persuade to abandon everything for the sake of freedom. In the absence of a surgeon, the ship's carpenter (good at using saws) the cook (skilled at butchering animals) or even barber (practiced with knives) would be pressed into service. If worse came to worse, any brave man with an axe could try. A person badly enough injured to need an amputation was in danger of death anyway.

These results often yielded very unsatisfactory results. The most famous legless pirate - Long John Silver - didn't have a wooden leg. He used a crutch instead. One assumes that putting weight on the remnants of a botched amputation were too painful to stand.

Must have been pretty bad. Crutches of the time were simple wooden "T"s without even a hand grip. Actors who have played Silver remark on how painful these crutches are to use.

And this leads us to why amputations and pirates go together - Writers.

Robert Louis Stevenson created Long John, and gave him the missing leg to make him distinctive. Similarly, J.M. Barrie gave his pirate a hook hand and the name Hook to make him a memorable, frightening character. And when Chris Columbus wrote a screenplay about a group of kids looking for pirate treasure, and needed a pirate that could be positively identified by his remains, he created One Eyed Willy.

It's been suggested that the eye patch thing actually had a reason. Famously, the Mythbusters postulated that wearing an eye patch enabled attacking pirates to keep one eye acclimated to the dark, so they could run belowdecks on a merchant ship without being blinded by the change of dark to light. This is persuasive, except that every effort was made to keep the lower decks on a ship as brightly lit as possible. After all, people had to work down there.

Historically, there are no really famous pirates missing either legs or hands. Pirates who lost limbs in the course of their work were paid a benefit out of the ship's operating so they could retire comfortably. One pirate did have a disabled eye. French pirate Olivier Levasseur (aka The Buzzard) had an eye that had been damaged by a sword stroke, and wore a black silk patch later in life.But he wasn't famous for the patch, and pictures don't show it, choosing instead to show the dramatic scar.

So hook hands, peg legs, and eye patches are associated with pirates simply because they could be. And because some very good writers chose to make these kinds of disabilities a distinctive mark of their greatest creations. It worked. We associate disabilities with pirates.

One other kind of prosthetic that was fairly common at the time was the prosthetic nose. People lost their noses - to frostbite, injury, and to disease. Syphilis, in its later stages, can cause skin lesions that ultimately cost the patient extremities like noses and ears.

My favorite is this ivory nose, although silver was also used by those who could afford it. Those who couldn't afford it wore a flap of leather to hide the disfigurement.

Anyone inspired to create a new pirate?

Published on December 01, 2014 19:25

November 24, 2014

Pirate Costumes in Pirates of the Caribbean

And now we come to the most obvious Pirate Movie Costumes. Pirates of the Caribbean is the movie that changed it all.

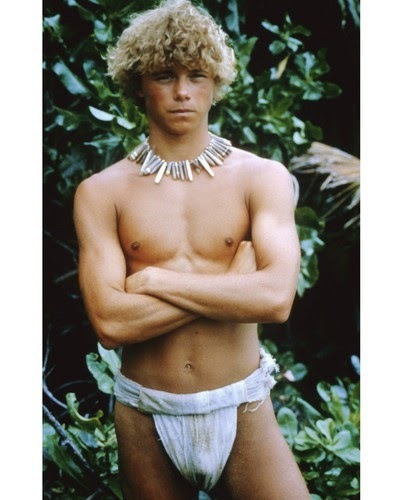

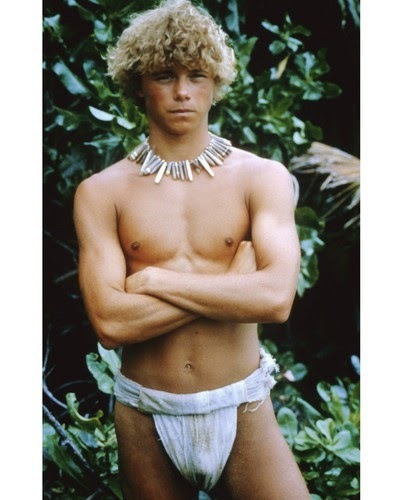

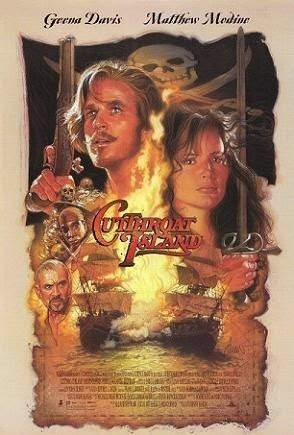

Movies like Cutthroat Island had given us a bit of a grungy look for the pirates. And the effect of star power in costuming goes all the way back to the 1920’s. But it all came together in POTC. Let’s begin with Johnny Depp.

Mr. Depp came into the project with enough star power to be allowed to “create his own character” in the wardrobe room with some pre-selected costumes. Depp chose the hat, Depp chose the coat. And, famously, Depp chose the dreadlocks, which scared the Authorities half to death.

Depp had an unusual grasp of the pirate mentality. He has famously said that pirates were the rockstars of their day. Many pirates kept an eye on what their image was. They dressed the part, either of madmen or of gentlemen, as the occasion warranted.

Jack Sparrow has the fine linen coat of a captain, a good hat, and a number of baubles about his person. Looking at him, you see a man who travels with only the clothes on his back. All of his gear is well-worn. And yet it has style. Depp had finally found the perfect image of a pirate.

Although technically it’s not part of the costume, Depp’s eyeliner is now seen on a lot of pirates that don’t claim to be be directly copying. It’s become something expected, as a mark of the job. Real pirates probably didn’t smear kohl around their eyes, but it’s now a mark of the profession. We’ll see if it lasts.

The costumes for POTC were much better researched than was usual for pirate movies. This might not seem at first like no big deal. After all, most people wouldn’t recognized out-of-time clothing.

But the clothing and decorations of a time period have a way of going together. After all, at any given period in history, there were a large number of artistically inclined people – tailors, dressmakers, furniture makers, decorative artists, taking inspiration from each other’s work and trying to create a harmonic “look”. When a costume designer picks up on this, they are getting thousands of hours of free design time to help create mood.

The mood of POTC is an excellent one for pirates. The civilized world – as shown by the crisp uniforms of Norrington and the Marines, as well as Governor Swan’s elaborate wigs and Elizabeth’s corset, is trying to impose itself on the “wild west” of the Caribbean.

Jack and his pirates – as well as the average people on the street – are dressed practically in rags (in fact, costume designer Penny Rose aged the fabrics by throwing them in a cement mixer with gravel and bricks, and letting them tumble).

The wear may seem excessive, but in fact the poor people of the time often wore clothing until it literally fell apart. The line between rich and poor was very clear during the 18th century. That’s part of what caused piracy to rise.

It’s kind of symbolic that when Jack first meets Elizabeth, he frees her from her corset, releasing her to go on the pirate adventure. She still doesn’t have the corset on when she ends up on the Black Pearl, but is dressed primly in a nightgown and wrapper. Barbosa gives her dress to wear, significantly a dress from an earlier time (the red gown he gives her looks like it dates from Captain Morgan’s time – when piracy was a more acceptable lifestyle).

Elizabeth throws the gown back at Barbosa when he makes her walk the plank. What she’s left with is underwear – a lot of underwear for a modern-day viewer, but underwear all the same. So she’s wearing underwear when she reveals her true self.

She gets Jack drunk, then burns all the rum, creating the smoke tower that brings about her rescue. And then she makes her deal with Norrington to save Will. It’s as if she is finally stripped down to her true self.

For the final battle, she’s in a marine’s uniform, appropriately enough. Her return to “proper attire” for Jack’s hanging is meant to hint that she may yet be forced into her previous role. But a close look reveals details in her clothing and carriage that are no longer the same. Elizabeth is a woman now, and she knows her heart.

Norrington, another one of my POTC favorites, also has clothing that tells a story. Originally meant to be the “bad guy” in Curse of the Black Pearl, Norrie was just too nice a guy. His perfect uniform tells the audience who he is.