Lorin Hochstein's Blog, page 13

December 16, 2022

Knowledge and Power: A Sociotechnical Systems Discussion on the Future of SRE

The opening keynote I gave with Laura Maguire at SRECon EMEA is now available online:

December 11, 2022

Incident categories I’d like to see

If you’re categorizing your incidents by cause, here are some options for causes that I’d love to see used. These are all taken directly from the field of cognitive systems engineering research.

Production pressureAll of us are so often working near saturation: we have more work to do than time to do it. As a consequence, we experience pressure to get that work done, and the pressure affects how we do our work and the decisions we make. Multi-tasking is a good example of a symptom of production pressure.

Ask yourself “for the people whose actions contributed to the incident, what was their personal workload like? How did it shape their actions?”

Goal conflictsOften we’re trying to achieve multiple goals while doing our work. For example, you may have a goal to get some new feature out quickly (production pressure!), but you also have a goal to keep your system up and running as you make changes. This creates a goal conflict around how much time you should put into validation: the goal of delivering features quickly pushes you towards reducing validation time, and the goal of keeping the system up and running pushes you towards increasing validation time.

If someone asks “Why did you take action X when it clearly contravenes goal G?”, you should ask yourself “was there another important goal, G1, that this action was in support of?”

WorkaroundsHow do you feel about the quality of the software tools that you use in order to get your work done? (As an example: how are the deployment tools in your org?)

Often the tools that we use are inadequate in one way or another, and so we resort to workarounds: getting our work done in a way that works but is not the “right” way to do it (e.g., not how the tool was designed to be used, against the official process of how to do things). Using workarounds is often dangerous because the system wasn’t designed with that type of work in mind. But if the dangerous way of doing work is the only way that the work can get done, then you’re going to end up with people taking dangerous actions.

If an incident involves someone doing something they weren’t “supposed to”, you should ask yourself, “did they do it this way because they are working around some deficiency in the tools that have to use?”

Automation surprisesSoftware automation often behaves in ways that people don’t expect: we have incorrect mental models of why the system is doing what it is, often because the system isn’t designed in a way to make it easy for us to form good mental models of behavior. (As someone who works on a declarative deployment system, I acutely feel the pain we can inflict on our users in this area).

If someone took the “wrong” action when interacting with a software system in some way, ask yourself “what was their understanding of the state of the world at the time, and what was their understanding of what the result of that action would be? How did they form their understanding of the system behavior?”

Do you find this topic interesting? If so, I bet you’ll enjoy attending the upcoming Learning from Incidents Conference taking place on Feb 15-16, 2023 in Denver, CO.

CasesConf experience report

I attended a CasesConf a few months ago, I wrote up a post about my experience on the Learning From Incidents site.

If this sounds like something you’d enjoy attending, the upcoming Learning from Incidents conference is going to have a CasesConf: incident stories track. Come join us!

November 25, 2022

Cache invalidation really is one of the hardest problems in computer science

My colleagues recently wrote a great post on the Netflix tech blog about a tough performance issue they wrestled with. They ultimately diagnosed the problem as false sharing, which is a performance problem that involves caching.

I’m going to take that post and write a simplified version of part of it here, as an exercise to help me understand what happened. After all, the best way to understand something is to try to explain it to someone else.

But note that the topic I’m writing about here is outside of my personal area of expertise, so caveat lector!

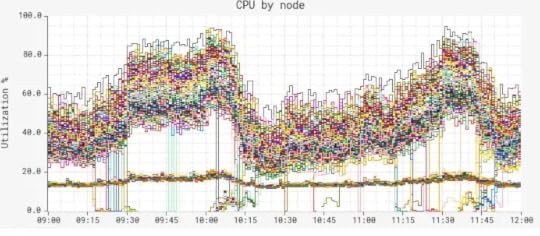

The problem: two bands of CPU performanceHere’s a graph from that post that illustrates the problem. It shows CPU utilization for different virtual machines instances (nodes) inside of a cluster. Note that all of the nodes are configured identically, including running the same application logic and taking the same traffic.

Note that there are two “bands”, a low band at around 15-20% CPU utilization, and a high band that varies a lot, from about 25%-90%.

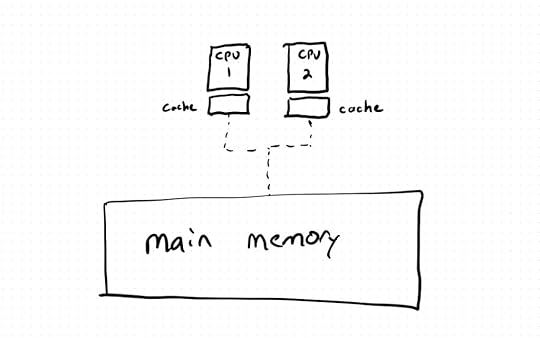

Caching and multiple coresComputer programs keep the data that they need in main memory. The problem with main memory is that accessing it is slow in computer time. According to this site, a CPU instruction cycle is about 400ps, and accessing main memory (DRAM access) is 50-100ns, which means it takes ~ 125 – 250 cycles. To improve performance, CPUs keep some of the memory in a faster, local cache.

There’s a tradeoff between the size of the cache and its speed, and so computer architects use a hierarchical cache design where they have multiple caches of different sizes and speeds. It was an interaction pattern with the fastest on-core cache (the L1 cache) that led to the problem described here, so that’s the cache we’ll focus on in this post.

If you’re a computer engineer designing a a multi-core system where each core has on-core cache, your system has to implement a solution for the problem known as cache coherency.

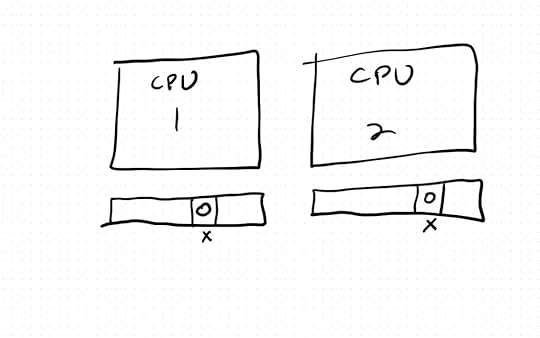

Cache coherencyImagine a multi-threaded program where each thread is running on a different core. There’s a variable, which we’ll call x.

Let’s also assume that both threads have previously read x, so the memory associated with x is loaded in the caches of both. So the caches look like this:

Now imagine thread T1 modifies x, and then T2 reads x.

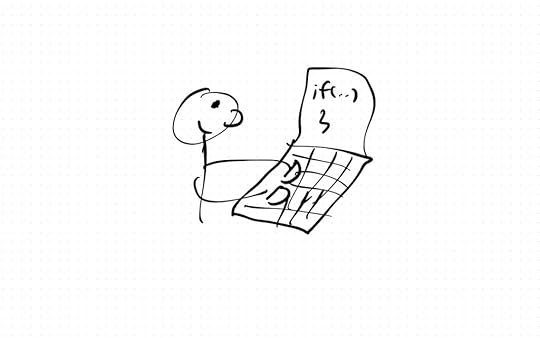

T1 T2-- --x = x + 1 if(x==0) { // shouldn't execute this! }

T1 T2-- --x = x + 1 if(x==0) { // shouldn't execute this! } The problem is that T2’s local cache has become stale, and so it reads a value that is no longer valid.

The term cache coherency refers to the problem of ensuring that local caches in a multi-core (or, more generally, distributed) system stay in sync.

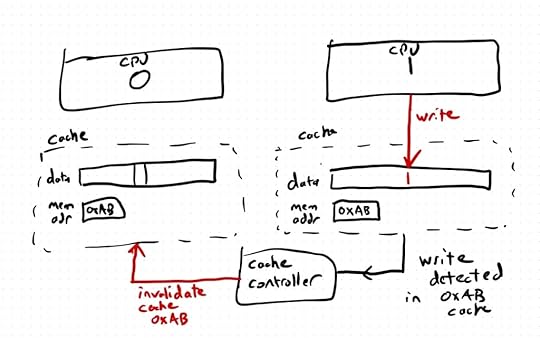

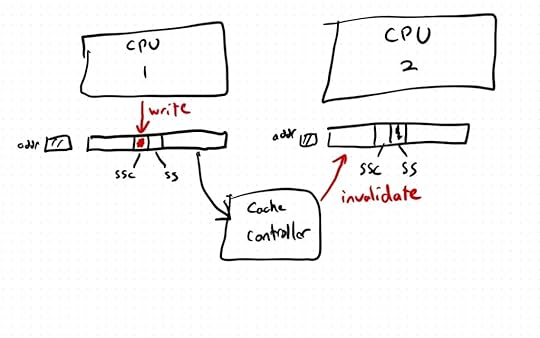

This problem is solved by a hardware device called a cache controller. The cache controller can detect when values in a cache have been modified on one core, and whether another core has cached the same data. In this case, the cache controller invalidates the stale cache. In the example above, the cache controller would invalidate the cache in T2. When T2 went to read the variable x, it would have to read the data from main memory into the core.

Cache coherency ensures that the behavior is correct, but every time a cache is invalidated and the same memory has to be retrieved from main memory again, it pays the performance penalty of reading from main memory.

The diagram above shows that the cache contains both the data as well as the addresses in main memory where the data comes from: we only need to invalidate caches that correspond to the same range of memoryData gets brought into cache in chunks

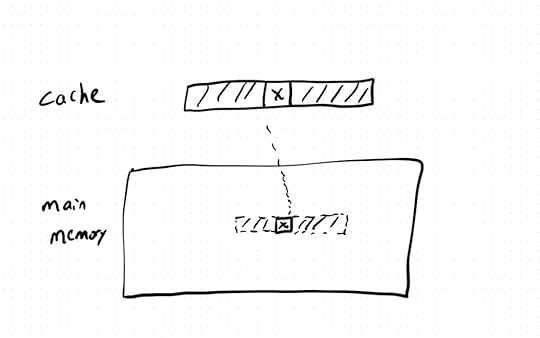

The diagram above shows that the cache contains both the data as well as the addresses in main memory where the data comes from: we only need to invalidate caches that correspond to the same range of memoryData gets brought into cache in chunksLet’s say a program needs to read data from main memory. For example, let’s say it needs to read the variable named x. Let’s assume x is implemented as a 32-bit (4 byte) integer. When the CPU reads from main memory, the memory that holds the variable x will be brought into the cache.

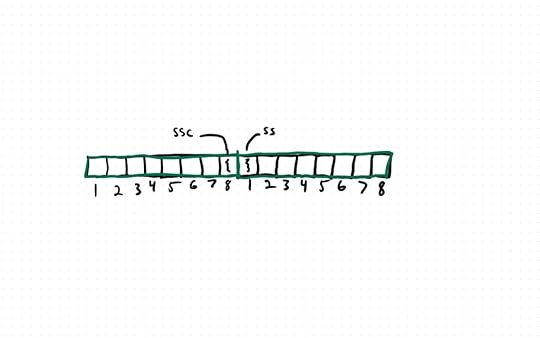

But the CPU won’t just read the variable x into cache. It will read a contiguous chunk of memory that includes the variable x into cache. On x86 systems, the size of this chunk is 64 bytes. This means that accessing the 4 bytes that encodes the variable x actually ends up bringing 64 bytes along for the ride.

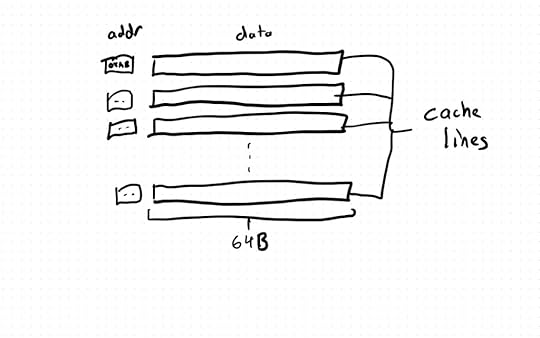

These chunks of memory stored in the cache are referred to as cache lines.

False sharing

False sharingWe now almost have enough context to explain the failure mode. Here’s a C++ code snippet from the OpenJDK repository (from src/hotspot/share/oops/klass.hpp)

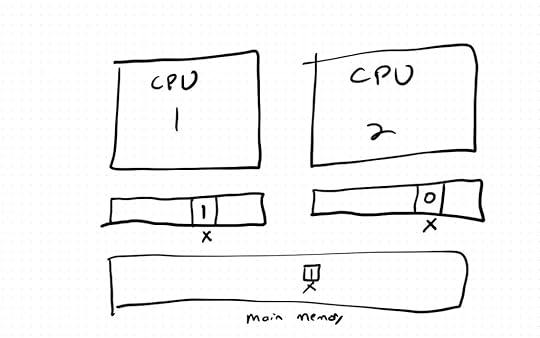

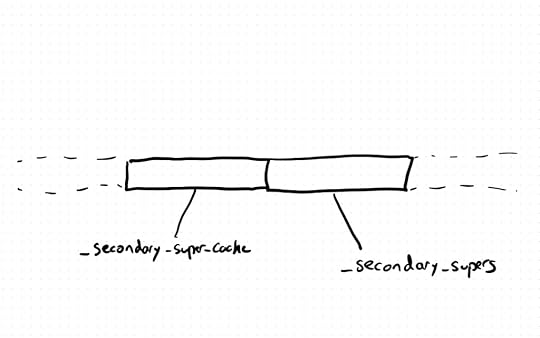

class Klass : public Metadata { ... // Cache of last observed secondary supertype Klass* _secondary_super_cache; // Array of all secondary supertypes Array* _secondary_supers;This declares two pointer variables inside of the Klass class: _secondary_super_cache, and _secondary_supers. Because these two variables are declared one after the other, they will get laid out next to each other in memory.

The two variables are adjacent in main memory.

The two variables are adjacent in main memory.The _secondary_super_cache is, itself, a cache. It’s a very small cache, one that holds a single value. It’s used in a code path for dynamically checking if a particular Java class is a subtype of another class. This code path isn’t commonly used, but it does happen for programs that dynamically create classes at runtime.

Now imagine the following scenario:

There are two threads: T1 on CPU 1, T2 on CPU 2T1 wants to write the _secondary_super_cache variable and already has the memory associated with the _secondary_super_cache variable loaded in its L1 cacheT2 wants to read from the _secondary_supers variable and already has the memory associated with the _secondary_supers variable loaded in its L1 cache.When T1 (CPU 1) writes to _secondary_super_cache, if CPU 2 has the same block of memory loaded in its cache, then the cache controller will invalidate that cache line in CPU 2.

But if that cache line contained the _secondary_supers variable, then CPU 2 will have to reload that data from cache to do its read, which is slow.

ssc refers to _secondary_super_cache, ss refers to _secondary_supers

ssc refers to _secondary_super_cache, ss refers to _secondary_supersThis phenomenon, where the cache controller invalidates cached non-stale data that a core needed to access, which just so happens to be on the same cache line as stale data, is called false sharing.

What’s the probability of false sharing in this scenario?In this case, the two variables are both pointers. On this particular CPU architecture, pointers are 64-bits, or 8 bytes. The L1 cache line size is 64 bytes. That means a cache line can store 8 pointers. Or, put another away, a pointer can occupy one of 8 positions in the cache line.

There’s only one scenario where the two variables don’t end up on the same cache line: when _secondary_super_cache occupies position 8, and _secondary_supers occupies position 1. In all of the other scenarios, the two variables will occupy the same cache line, and hence will be vulnerable to false sharing.

1 / 8 = 12.5%, and that’s roughly the number of nodes that were observed in the low band in this scenario.

And now I recommend you take another look at the original blog post, which has a lot more details, including how they solved this problem, as well as a new problem that emerged once they fixed this one.

November 24, 2022

Writing docs well: why should a software engineer care?

Recently I gave a guest lecture in a graduate level software engineering course on the value of technical writing for software engineers. This post is a sort of rough transcript of my talk.

I live-sketched my slides as I went.

I talked about three goals of doing doing technical writing.

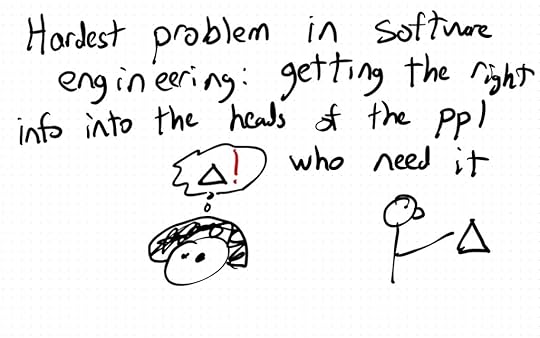

The first one is about building shared understanding among stakeholders of a document. One of the hardest problems in software engineering is getting multiple people to have a sufficient understanding of some technical aspect, like the actual problem being solved, or a proposed solution. This is ostensibly the only real goal of technical writings.

Shared understanding is related to the idea of common ground that you’ll sometimes hear the safety folks talk about.

If you’re a programmer who works completely alone, then this is a problem you generally don’t have to solve, because there’s only one person involved in the software project.

But as soon as you are working in a team, then you have to address the problem of shared understanding.

When we work on something technical, like software, we develop a much deeper understanding because we’re immersed in it. This can make communication hard when we’re talking to someone who hasn’t been working in the same area and so doesn’t have the same level of technical understanding of that particular bit.

If you’re working only with a small, co-located group (e.g., in a co-located startup), then having a discussion in front of a whiteboard is a very effective mechanism for building shared understanding. In this type of environment, writing effective technical docs is much less important.

The problem with the discuss-in-front-of-the-whiteboard approach is that it doesn’t scale up, and it also doesn’t work for distributed environments.

And this is where technical documents come in.

I like to say that the hardest problem in software engineering is getting the appropriate information into the heads of the people who need to have that information in order to do their work effectively.

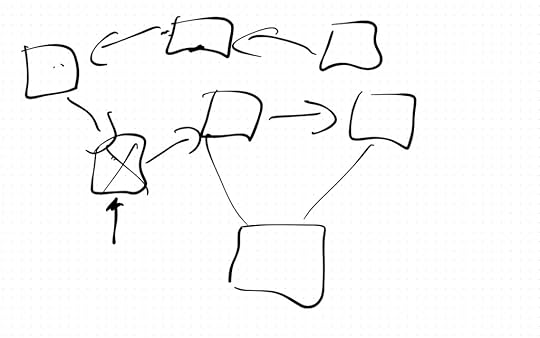

In large organizations, a lot of the work is interconnected, which means that some work that somebody else is doing can affect your work. If you’re not aware of that, you can end up working at cross-purposes.

The challenge is that there’s so much potential information that might be useful. Everyone could potentially spend all of their working hours reading docs, and still not read everything that might be relevant.

To write a doc well means to get people to gain sufficient understanding so that you can coordinate work effectively.

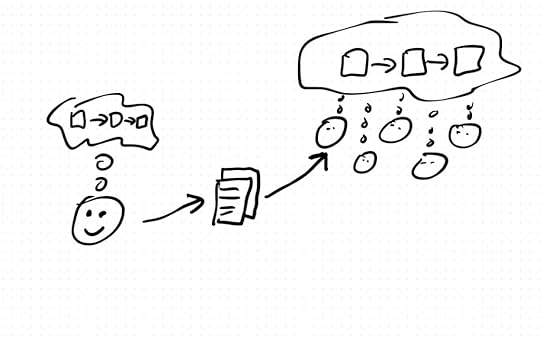

The second goal of writing I talked about was using writing to help with your own thinking.

The cartoonist Richard Guindon has a famous quote: “writing is nature’s way of letting you know how sloppy your thinking is.” You might have an impression that you understand something well, but that sense of clarity is often an illusion, and when you go to explicitly capture your understanding in a document, you discover that you didn’t understand things as well as you thought. There’s nowhere to hide in your own document.

When writing technical docs, I always try hard to work explicitly through examples to demonstrate the concepts. This is one of the biggest weaknesses I see in practice in technical docs, that the author has not described a scenario from start to finish. Conceptually, you want your doc to have something like a storyboard that’s used in the film industry, to tell the story. Writing out a complete example will force you to confront the gaps in your understanding.

The third goal is a bit subversive: it’s how to use effective technical writing to have influence in a larger organization when you’re at the bottom of the hierarchy.

If you want influence, you likely have some sort of vision of where you want the broader organization to go, and the challenge is to persuade people of influence to move things closer to your vision.

Because senior leadership, like everyone else in the organization, only has a finite amount of time and attention, their view of reality are shaped by the interactions they do have: which is largely through meetings and documents. Effective technical documents shape the view of reality that leadership has, but only if they’re written well.

If you frame things right, you can make it seem as if your view is reality rather than simply your opinion. But this requires skill.

Software engineers often struggle to write effective docs. And that’s understandable, because writing effective technical docs is very difficult.

Anyone who has set down at a computer to write a doc and has stared at the blinking cursor at an empty doc knows how difficult it can be to just get started.

Even the best-written technical docs aren’t necessarily easy to read.

Poorly written docs are hard to read. However, just because a doc is hard to read, doesn’t mean it’s poorly written!

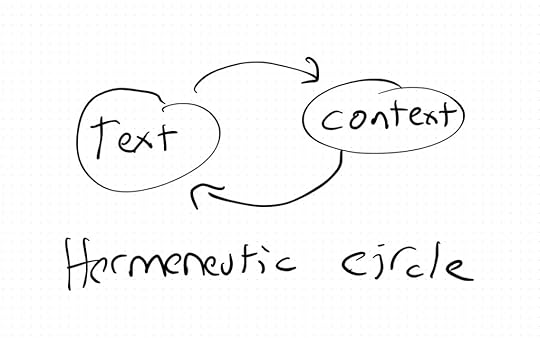

This talk is about technical writing, but technical reading is also a skill. Often, we can’t understand a paragraph in a technical document without having a good grasp of the surrounding context. But we also can’t understand the context without reading the individual paragraphs, not only of this document, but of other documents as well!

This means we often can’t understand a technical document by reading from beginning to end. We need to move back and forth between working to understand the text itself and working to understand the wider context. This pattern is known as the hermeneutic circle, and it is used in Biblical studies.

Finally, some pieces of advice on how to improve your technical writing.

Know explicitly in advance what your goal is in doing the writing. Writing to improve your own understanding is different from writing to improve someone else’s understanding, or to persuade someone else.

Make sure your technical document has concrete examples. These are the hardest to write, but they are most likely to help achieve your goals in your document.

Get feedback on your drafts from people that you trust. Even the best writers in the world benefit from having good editors.

October 9, 2022

Time keeps on slippin’: A review of “Four thousand weeks”

Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman

Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver BurkemanBurkeman isn’t interested in helping you get more done. The problem, he says, is that attempting to be more productive is a trap. Instead, what he advocates is that you change your perspective to use your time *well*, rather than trying to get as much done as possible.

This is really an anti-productivity book, and a fantastic one at that. Burkeman urges us to embrace the fact that we only have a limited amount of time (“four thousand weeks” is an allusion to the average lifespan), and that we should embrace this limit rather than try to fight against it.

Holding yourself to impossible standards is a recipe for misery, he reminds us, whether it’s trying to complete all of the items on our todo lists or trying to be the person we ought to be rather than looking at who we actually are: what our actual strengths and weaknesses are, and what we genuinely enjoy doing.

The time mangement skills that Burkeman encourages are the ones that will reduce the amount of time pressure that we experience. Learn how to say “no” to the stuff that you want to do, but that you want to do less than the other stuff. Learn to make peace with the fact that you will always feel overwhelmed.

“Let go”, Burkeman urges us. After all, in the grand scheme of things, the work that we do doesn’t matter nearly as much as we think.

(Cross-posted to goodreads)

The down side of writing things down

Starting after World War II, the idea was culture is accelerating. Like the idea of an accelerated culture was just central to everything. I feel like I wrote about this in the nineties as a journalist constantly. And the internet seemed like, this is gonna be the ultimate accelerant of this. Like, nothing is going to accelerate the acceleration of culture like this mode of communication. Then when it became ubiquitous, it sort of stopped everything, or made it so difficult to get beyond the present moment in a creative way.

Chuck Klosterman, interviewed on the Longform Podcast

We software developers are infamous for our documentation deficiencies: the eternal lament is that we never write enough stuff down. If you join a new team, you will inevitably discover that, even if some important information is written down, there’s also a lot of important information that is tacit knowledge of the team, passed down as what’s sometimes referred to as tribal lore.

But writing things down has a cost beyond the time and effort required to do the writing: written documents are durable, which means that they’re harder to change. This durability is a strength of documentation, but it’s also a weakness. Writing things down has a tendency to ossify the content, because it’s much more expensive to update than tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is much more fluid: it adapts to changing circumstances much more quickly and easily than updating documentation, as anybody who has dealt with out-of-date written procedures can attest to.

October 8, 2022

There is no “Three Mile Island” event coming for software

In Critical Digital Services: An Under-Studied Safety-Critical Domain, John Allspaw asks:

Critical digital services has yet to experience its “Three-Mile Island” event. Is

such an accident necessary for the domain to take human performance seriously? Or can it translate what other domains have learned and make productive use of

those lessons to inform how work is done and risk is anticipated for the future?

I don’t think the software world will ever experience such an event.

The effect of TMIThe Three Mile Island accident (TMI) is notable, not because of the immediate impact on human lives, but because of the profound effect it had on the field of safety science.

Before TMI, the prevailing theories of accidents was that they were because of issues like mechanical failures (e.g., bridge collapse, boiler explosion), unsafe operator practices, and mixing up physical controls (e.g., switch that lowers the landing gear looks similar to switch that lowers the flaps).

But TMI was different. It’s not that the operators were doing the wrong things, but rather that they did the right things based on their understanding of what was happening, but their understanding of what was happening, which was based on the information that they were getting from their instruments, didn’t match reality. As a result, the actions that they took contributed to the incident, even though they did what they were supposed to do. (For more on this, I recommend watching Richard Cook’s excellent lecture: It all started at TMI, 1979).

TMI led to a kind of Cambrian explosion of research into human error and its role in accidents. This is the beginning of the era where you see work from researchers such as Charles Perrow, Jens Rasmussen, James Reason, Don Norman, David Woods, and Erik Hollnagel.

Why there won’t be a software TMITMI was significant because it was an event that could not be explained using existing theories. I don’t think any such event will happen in a software system, because I think that every complex software system failure can be “explained”, even if the resulting explanation is lousy. No matter what the software failure looks like, someone will always be able to identify a “root cause”, and propose a solution (more automation, better procedures). I don’t think a complex software failure is capable of creating TMI style cognitive dissonance in our industry: we’re, unfortunately, too good at explaining away failures without making any changes to our priors.

We’ll continue to have Therac-25s, Knight Capitals, Air France 447s, 737 Maxs, 911 outages, Rogers outages, and Tesla autopilot deaths. Some of them will cause enormous loss of human life, and will result in legislative responses. But no such accident will compel the software industry to, as Allspaw puts it, take human performance seriously.

Our only hope is that the software industry eventually learns the lessons that the safety science learned from the original TMI.

September 17, 2022

Up and down the abstraction hierarchy

As operators, when the system we operate is working properly, we use a functional description of the system to reason about its behavior.

Here’s an example, taken from my work on a delivery system. if somebody asks me, “Hey, Lorin, how do I configure my deployment so that a canary runs before it deploys to production?”, then I would tell them, “In your deliver config, add a canary constraint to the list of constraints associated with your production environment, and the delivery system will launch a canary and ensure it passes before promoting new versions to production.”

This type of description is functional; It’s the sort of verbiage you’d see in a functional spec. On the other hand, if an alert fires because the environment check rate has dropped precipitously, the first question I’m going to ask is, “did something deploy a code change?” I’m not thinking about function anymore, but I’m thinking of the lowest level of abstraction.

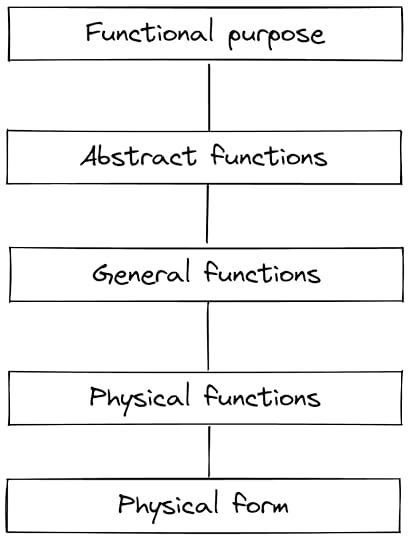

In the mid nineteen-seventies, the safety researcher Jens Rasmussen studied how technicians debugged electronic devices, and in the mid-eighties he proposed a cognitive model about how operators reason about a system when troubleshooting, in a paper titled the role of hierarchical knowledge representation in decisionmaking and system management. He called this model the abstraction hierarchy.

Rasmussen calls this model a means-ends hierarchy, where the “ends” are at the top (the function: what you want the system to do), and the “means” are at the bottom (how the system is physically realized). We describe the proper function of the system top-down, and when we successfully diagnose a problem with the system, we explain the problem bottom-up.

The abstraction hierarchy, explained with an example The five levels of the abstraction hierarchy

The five levels of the abstraction hierarchyTo explain these, I’ll use the example of a car.

The functional purpose of the car is to get you from one place to another. But to make things simpler, let’s zoom in on the accelerator. The functional purpose of the accelerator is to make the car go faster.

The abstract functions include transferring power from the car’s power source to the wheels, as well as transferring information from the accelerator to that system about how much power should be delivered. You can think of abstract functions as being functions required to achieve the functional purpose.

The generalized functions are the generic functional building blocks you use to implement the abstract functions. In the case of the car, you need a power source, you need a mechanism for transforming the stored energy to mechanical energy, a mechanism for transferring the mechanical energy to the wheels.

The physical functions capture how the generalized function is physically implemented. In an electric vehicle, your mechanism for transforming stored energy to mechanical energy is an electric motor; in a traditional car, it’s an internal combustion engine.

The physical form captures the construction detail of how the physical function. For example, if it’s an electric vehicle that uses an electric motor, the physical form includes details such as where the motor is located in the car, what its dimensions are, and what materials it is made out of.

Applying the abstraction hierarchy to softwareAlthough Rasmussen had physical systems in mind when he designed the hierarchy (his focus was on process control, and he worked at a lab that focused on nuclear power plants), I think the model can map onto software systems as well.

I’ll use the deployment system that I work on, Managed Delivery, as an example.

The functional purpose is to promote software releases through deployment environments, as specified by the service owner (e.g., first deploy to test environment, then run smoke tests, then deploy to staging, wait for manual judgment, then run a canary, etc.)

Here are some examples of abstract functions in our system.

There is an “environment check” control loop that evaluates whether each pending version of code is eligible for promotion to the next environment by checking its constraints.There is a subsystem that listens for “new build” events and stores them in our database.There is a “resource check” control loop that evaluates whether the currently deployed version matches the most recent eligible version.For generalized functions, here are some larger scale building blocks we use:

a queue to consume build events generated by the CI systema relational database to track the state of known versionsa workflow management system for executing the control loopsFor the physical functions that realize the generalized functions:

SQS as our queueMySQL Aurora as our relational databaseTemporal as our workflow management systemFor physical form, I would map these to:

source code representation (files and directory structure)binary representation (e.g., container image, Debian package)deployment representation (e.g., organization into clusters, geographical regions)Consider: you don’t care about how your database is implemented, until you’re getting some sort of operational problem that involves the database, and then you really have to care about how it’s implemented to diagnose the problem.

Why is this useful?If Rasmussen’s model is correct, then we should build operator interfaces that take the abstraction hierarchy into account. Rasmussen called this approach ecological interface design (EID), where the abstraction hierarchy is explicitly represented in the user interface, to enable operators to more easily navigate the hierarchy as they do their troubleshooting work.

I have yet to see an operator interface that does this well in my domain. One of the challenges is that you can’t rely solely on off-the-shelf observability tooling, because you need to have a model of the functional purpose and the abstract functions to build those models explicitly into your interface. This means that what we really need are toolkits so that organizations can build custom interfaces that can capture those top levels well. In addition, we’re generally lousy at building interfaces that traverse different levels: at best we have links from one system to another. I think the “single pane of glass” marketing suggests that people have some basic understanding of the problem (moving between different systems is jarring), but they haven’t actually figured out how to effectively move between levels in the same system.

August 5, 2022

Production pressure

The individual contributor feels production pressure from their manager.

The manager feels production pressure from their director.

The director feels production pressure from their vice president.

The vice president feels production pressure from their C-level executive.

The C-level executive feels production pressure from the CEO.

The CEO feels production pressure from the board of directors.

The board of directors feels production pressure from investment funds, who are the major shareholders.

And what about the managers of these investment funds? They feel production pressure to provide good returns so that customers will continue to invest. Many of their customers happen to hold shares of the fund in their retirement accounts. Customers such as … the individual contributor.

And the circle of production pressure is complete.